Abstract

Introduction

Measures of arterial pulse pressure (PP) variation and left ventricular (LV) stroke volume (SV) variation induced by positive-pressure breathing vary in proportion to preload responsiveness. However, the accuracy of commercially-available devices to report dynamic LV SV variation has never been validated.

Methods

We compared the accuracy of measured arterial PP and estimated LV SV reported from two FDA-approved aortic flow monitoring devices, one using arterial pulse power (LiDCOplus™) and the other esophageal Doppler monitor (EDM) (HemoSonic™). We compared estimated LV SV and their changes during a venous occlusion and release maneuver to a calibrated aortic flow probe placed around the aortic root on a beat-to-beat basis in 7 anesthetized open-chested cardiac surgery patients.

Results

Dynamic changes in arterial PP closely tracked LV SV changes (mean r2 0.96). Both devices showed good agreement with steady state apneic LV SV values and moderate agreement with dynamic changes in LV SV (EDM -1± 22 ml, and pulse power -7± 12 ml, bias ± 2SD). In general, the pulse power signals tended to underestimate LV SV at higher LV SV values.

Conclusion

Arterial PP, as well as, LV SV estimated from EDM and pulse power reflects short-term steady state LV SV values and tract dynamic changes in LV SV moderately well in humans.

Keywords: aortic blood flow, hemodynamic monitoring, preload-responsiveness

Introduction

Recent interest has focused on continuous measures of cardiac output and its dynamic change during positive-pressure ventilation (1,2,3) or passive leg raising (4) as sensitive and specific predictors of preload-responsiveness. These dynamic changes can be monitored using devices that either estimate left ventricular (LV) stroke volume (SV) from the arterial pressure pulse (pulse contour and pulse power) (5) or descending aortic flow measured from an esophageal Doppler monitor (EDM) (6). Although these devices have been shown to accurately reflect steady state blood flow (5,7,8), their ability to accurately measure dynamic changes in LV SV during positive-pressure ventilation has never been validated. Indeed, we recently documented in a canine model that neither an arterial pulse contour device (PiCCO™ device, Pulsion Ltd.) nor an EDM device (CardiaQ™ device, Deltex Ltd.) measured LV SV in a quantitatively similar fashion when vasomotor tone and contractility were varied by pharmacologically (9). The arterial pulse contour SV data from that study was appropriately criticized because we used as our experimental model an acute canine preparation whose arterial compliance and impedance are markedly different from man (10). Present pulse contour and pulse power devices use algorithms based on human vascular characteristics that can be quite different from dogs and vary differently in response to changes in sympathetic tone.

Thus, in this study we repeated our initial validation study but in humans during cardiac surgery wherein absolute aortic blood flow was measured using a calibrated electromagnetic aortic flow probe (AFP). We chose to examine the dynamic changes in LV SV induced by venous occlusion instead of positive-pressure breathing, because in open-chest conditions heart-lung interactions are markedly diminished (11). Dynamic changes in LV SV were estimated using both a pulse contour and EDM monitors. Although we initially wished to studied two pulse contour devices (pulseCO™, LiDCO Ltd and PiCCO™, Pulsion Ltd.) and two EDM devices (HemoSonic™, Arrow International, and CardiaQ™, Deltex Ltd), the PiCCO device algorithm has been changed so that it now only reports mean LV SV averaged over 12 seconds and, due to technical reasons the CardiaQ™ EDM probe signal quality was unstable during open chest conditions making its estimates of LV SV not reproducible. Thus, we chose not to study the PiCCO device and not to report on the collected CardiaQ™ EDM device data.

Methods

The study was approved by our IRB for human experimentation and all patients gave informed consent for participation in the study. The goal of the study was to compare directly measured electromagnetic aortic flow-derived SV and arterial pulse pressure with estimates of LV SV and pulse pressure using arterial pulse pressure analysis and EDM as cardiac output was rapidly varied by obstruction of venous return by manual compression of the right atrium during open chest conditions.

Subject recruitment

Potential subjects were identified by their primary cardiac surgeon from the regular cardiac surgical schedule. All subjects >18 years of age undergoing elective coronary artery bypass surgery with a LV ejection fraction of >0.45 and who were at least 150 cm in height were eligible for inclusion into the study. Exclusion criteria included hemodynamic instability requiring pharmacologic support, obstructive valvulopathies, on-going arrhythmias or the concomitant use of an artificial LV assist device. Due to the highly invasive nature of this study and the potentially high risk nature of the surgical candidates, over 47 interviews over two and a half years before 12 subjects (male/female 10/2) were recruited into the protocol. Five of the recruited subjects were withdrawn from the study prior to starting data collection (male/female 3/2) because of hemodynamic instability after sternotomy in preparation for cardiopulmonary bypass (3 subjects) and inability to have data storage equipment available for the study (2 subjects). No subject recruited into this study had any untoward events associated with the special instrumentation required in this study or the study protocol itself. Thus, we report on the studies performed in 7 male subjects. Their demographics and related apneic measured hemodynamic variables are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Apneic Steady State Flow Measures

| Patient | Age (yr) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | Surgery | Aortic Diameter by EDM (cm) max/min | Aortic Diameter by Echocardiography (cm) max/min | Arterial Pulse Pressure (mm Hg) | Apneic SV By AFP (ml) | Apneic pulse power SV (ml) | Apneic EDM SV (ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR2 | 63 | 173 | 80 | CABG ×3 | 2.47/2.01 | 2.19/2.04 | 65.5 | 74.8 | 53.6 | 45.2 |

| OR3 | 73 | 180 | 102 | CABG ×4 | 2.96/2.96 | 2.55/2.37 | 50.0 | 37.4 | 38.9 | 83.8 |

| OR4 | 50 | 179 | 107 | CABG ×4 | 2.77/2.63 | 2.3/2.16 | 41.6 | 58.9 | 60.7 | 50.4 |

| OR6 | 77 | 170 | 65 | CABG ×2 | 2.85/2.5 | not measured | 55 | 45.4 | 39 | 52.9 |

| OR7 | 67 | 180 | 113 | CABG ×4 | 2.85/2.58 | not measured | 48.4 | 78.4 | 65.2 | 58.1 |

| OR8 | 49 | 190 | 120 | CABG ×4 | 2.93/2.61 | 2.46/2.24 | 64.4 | 94.1 | 93.7 | 76.7 |

| OR9 | 54 | 175 | 84 | CABG ×3 | 2.34/2.09 | 2.5/2.4 | 53.4 | 72.8 | 70.9 | 20.4 |

Abbreviations: EDM, esophageal Doppler monitor; AFP, aortic flow probe; SV, stroke volume; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft.

Instrumentation and Protocol

Anesthesia was induced and maintained at the discretion of the attending anesthesiologist. In practice this usually included using fentanyl (15-20 microg/kg), with isoflurane in an air/oxygen mixture during this period of the surgery. Continuous monitoring was performed with an electrocardiogram, radial arterial pressure catheter, pulmonary arterial pressure catheter, capnography, pulse oximetry, urine output, core temperature, airway pressure and bi-spectral electroencephalogram. In only three of the subjects due to technical reasons was the plethysmographic output of the pulse oximeter able to be recorded. Because of this large degree of missing data we chose not to report pulse oximetry plethysmographic signal data. A transesophageal echocardiographic probe (Sonos 1500 probe, Hewlett Packard Systems; Andover, MA) was then positioned and used to assess baseline cardiac performance during the initial part of the surgical procedure and also to measure the descending aortic diameter at the level of the EDM monitor. From a radial arterial catheter, pressure data was collected for off-line analysis of LV SV by the pulse power technique. Prior to the start of the protocol and when the patient was felt to be in stable condition the transesophageal echocardiographic probe was removed and the EDM probe inserted and calibrated, as previously described by us (6). Following sternotomy and pericardiotomy in preparation for cardiopulmonary bypass the surgeon placed a calibrated electromagnetic flow probe (Cineflo™, Carolina Medical Electronics, King, NC) around the ascending aorta, as previously described by us (11). The integrated value of this flow signal zeroed with each diastole was taken to reflect true LV SV. The device is referred to as an aortic flow probe (AFP).

Rapid alterations of LV filling were induced to produce a dynamic and adequate range of LV SV and arterial pressures to test the dynamic response of monitoring systems. The protocol consisted of a 15-second apneic interval to define a stable steady state followed by a transient obstruction of venous return by manual compression of the right atrium until systolic arterial blood pressure decreased by approximately 20 mm Hg, referred to as venous occlusion, and then release until systolic arterial blood pressure returned to steady state values. In practice the occlusion interval lasted from 10 to 15 seconds and release for about 5-10 seconds and resulted in no persistent negative cardiovascular effects or arrhythmias.

Following these maneuvers, the EDM probe was removed and the transesophageal echocardiographic probe re-inserted. At this time the echocardiographic probe was placed at the same location in the esophagus as the EDM probe and direct measures of the descending aortic cross sectional diameter were made to compare with those reported by the EDM probe. The accuracy of these measures is important because as we recently documented, if the measured aortic diameter is inaccurate then estimates of changes in aortic flow will also be inaccurate (12).

Data Collection

Arterial pressure, AFP, and EDM velocity and diameter outputs were continually recorded during each epoch of steady state apnea and venous occlusion and release using a personal computer (Dell Pentium 300 MHz, www.dell.com). This computer collected CardiaQ, HemoSonic, AFP and routine hemodynamic data via an A-to-D conversion system (WINDAQ v2.34, DataQ, King of Prussia, PA) at 150 Hz. The computer and A-to-D system was then used to replay the collected digitized arterial pressure waveform data from the arterial pressure output for off-line calculations of LV SV via the LiDCOplus™ pulse power algorithm.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed off-line to derive individual device estimates of LV stroke volume. The EDM descending aortic stroke volume values and its changes during the venous occlusion and release maneuver were assumed to reflect proportional changes in LV SV. Beat-to-beat pulse power SV was matched to AFP-derived SV measures. Paired arterial pulse pressure (diastolic to subsequent systolic pressure difference) data were also compared to SV during transient venous occlusion and release.

Statistical Analysis

Correlation between SV measures were analyzed by the Pearson moment analysis during apneic steady state, and correlation coefficient (r) and Bland-Altman analysis between AFP and measured variables during dynamic changes in LV SV, as previously described (13) using a computer-based statistical analysis program (PASS 6.0 Statistical software, NCSS, Kaysville, Utah). Statistical significance reports a p value < 0.05.

Results

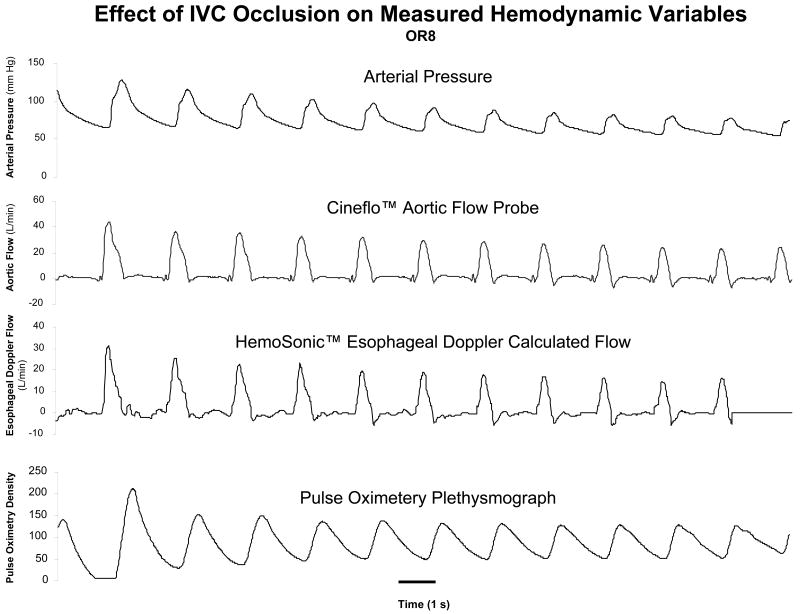

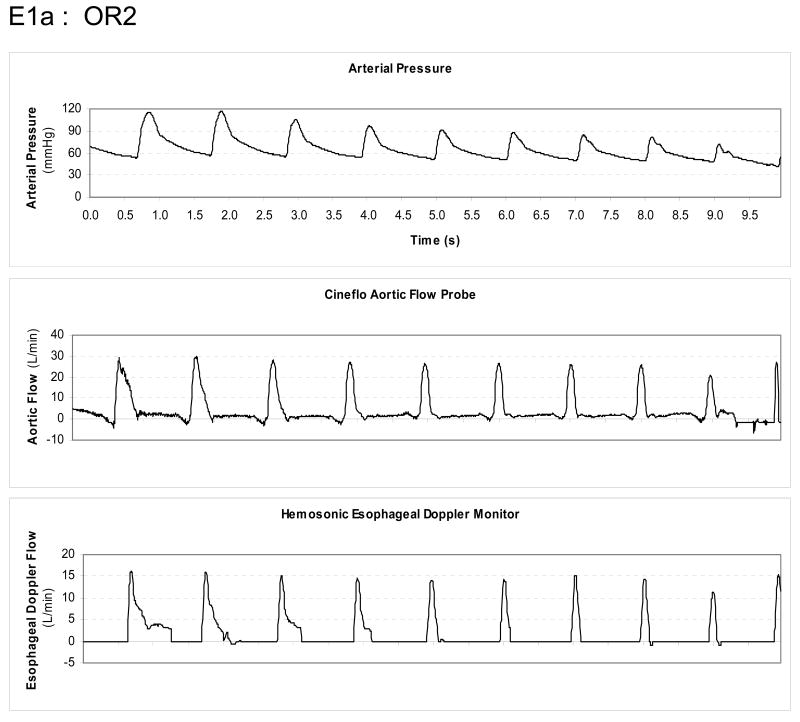

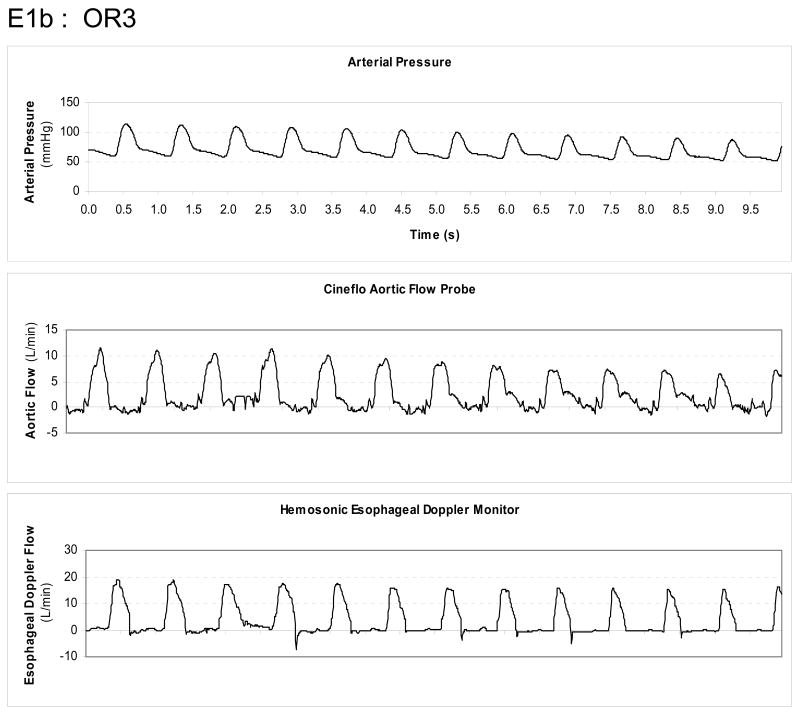

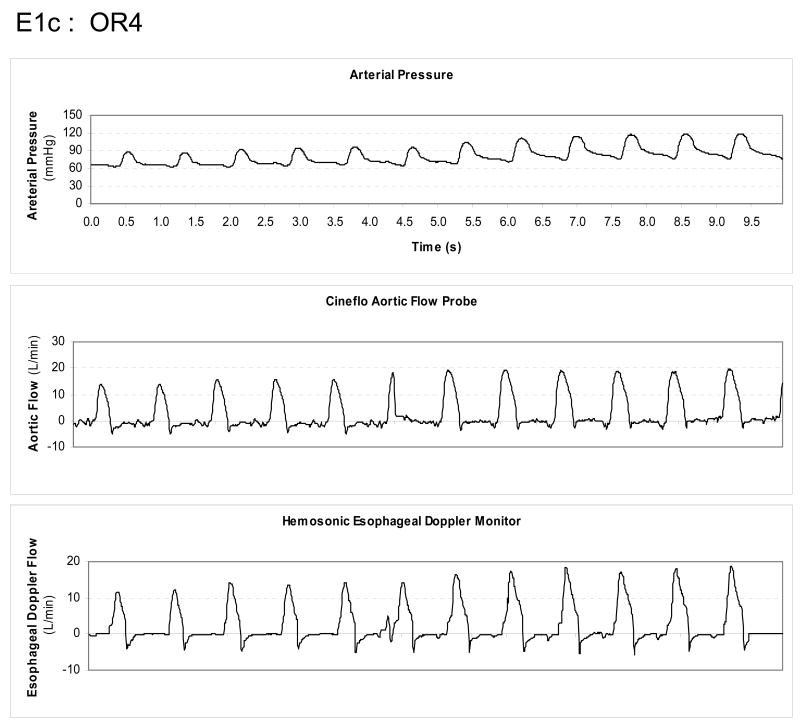

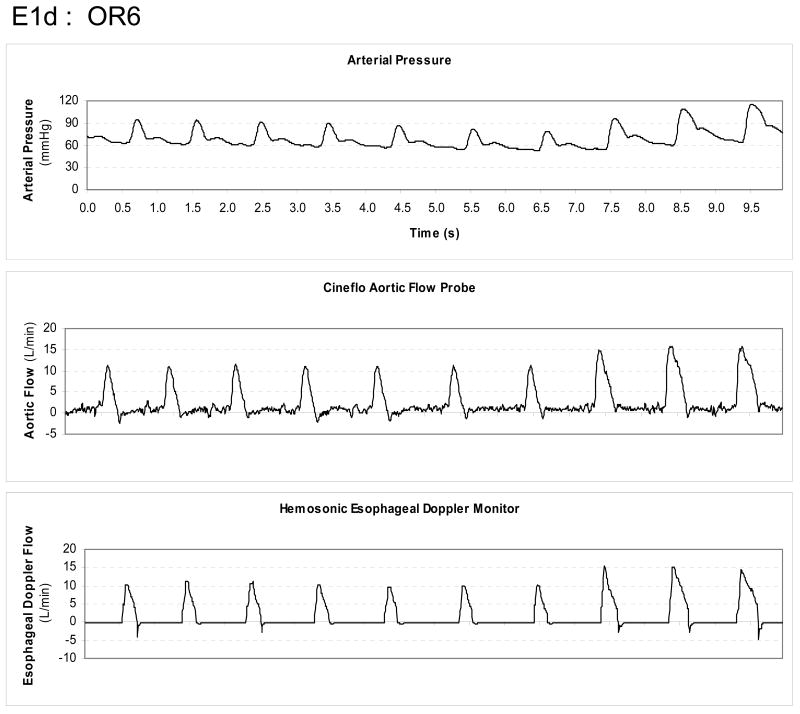

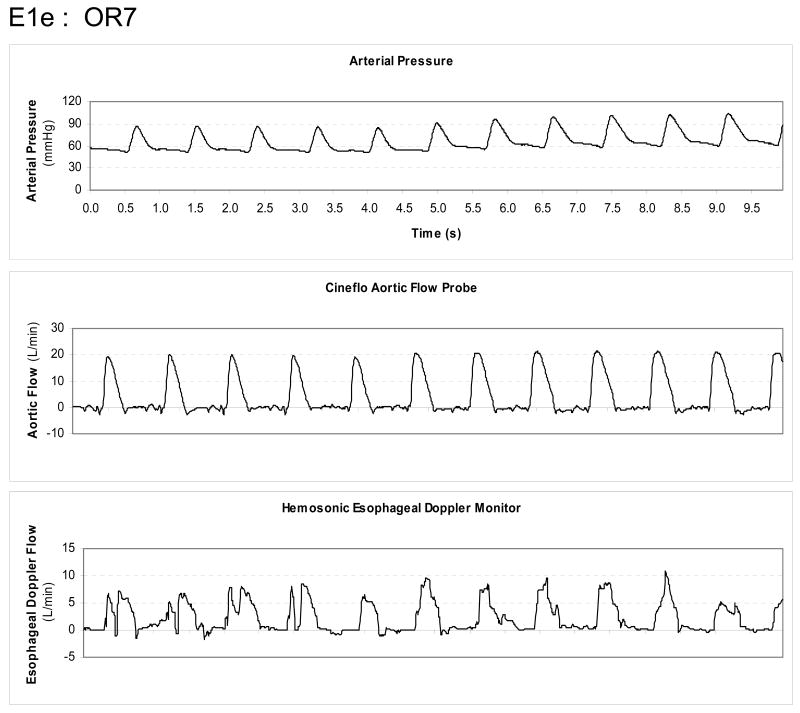

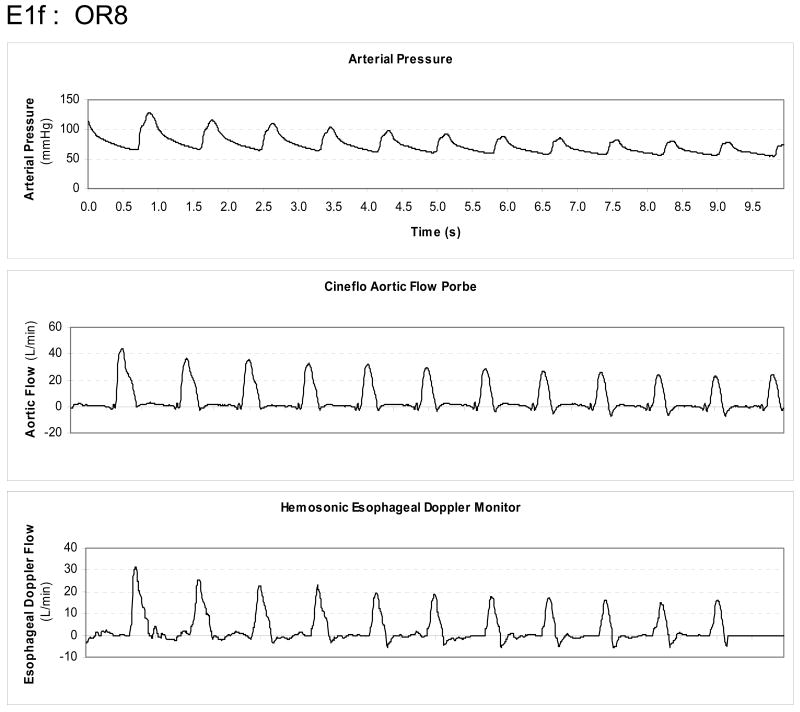

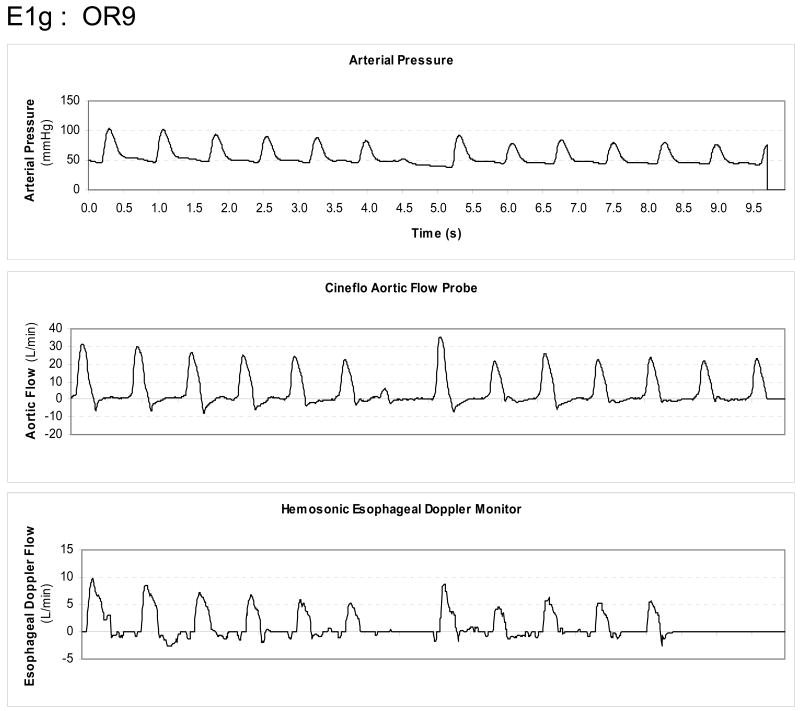

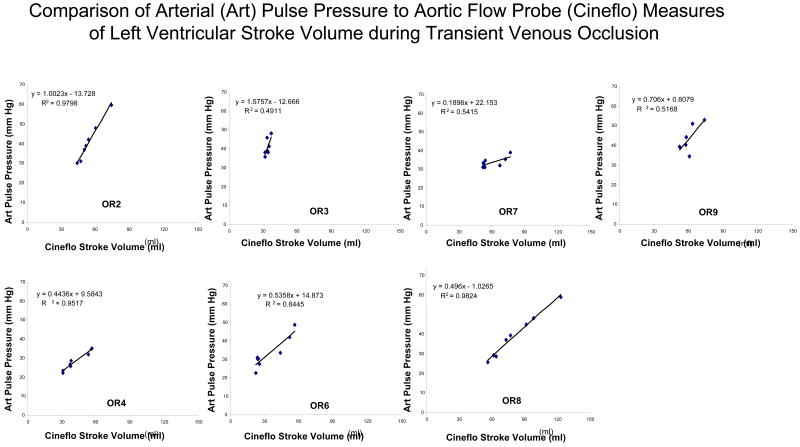

All seven subjects performed at least two venous occlusion-release maneuvers, from which the one with the least EDM flow artifact was taken for analysis. If both runs were similar, the first run was used. The mean apneic hemodynamic variables for EDM and pulse power devices, including aortic diameter estimates, are summarized in Table 1. During apneic steady state values, both EDM and pulse power estimates of LV SV varied by <4% from measured LV SV values for all subjects. As can be seen in figure 1 from one subject (OR8), venous occlusion resulted in marked changes in both aortic flow and arterial pressure. The relation between changes in arterial pulse pressure and LV SV measured by AFP during venous occlusion was linear across subjects (Fig. 2) although the degree of correlation (R2) varied from 0.98 to 0.49.

Figure 1.

Trend display from one subject of radial arterial pressure, Cineflo™ aortic flow probe and HemoSonic™ esophageal Doppler monitor changes over a 20 second interval starting from apneic baseline and during inferior vena caval obstruction.

Figure 2.

Regression analysis for arterial pulse pressure versus aortic flow probe-derived stroke volume (Cineflo™ stroke volume) for all subjects.

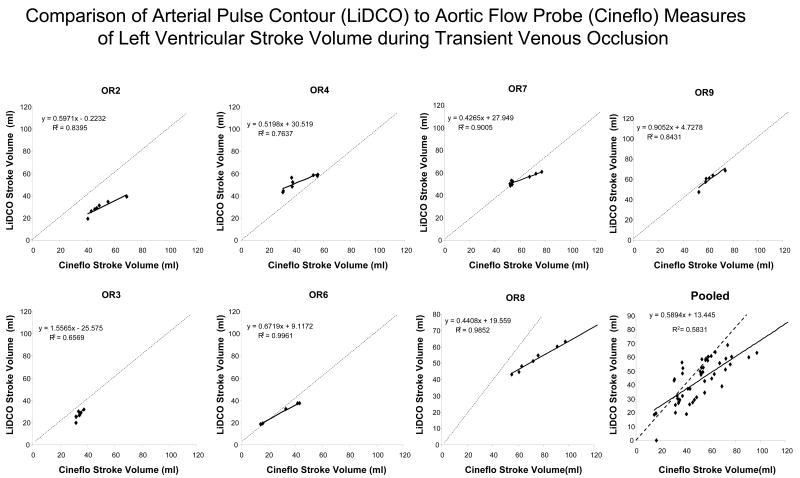

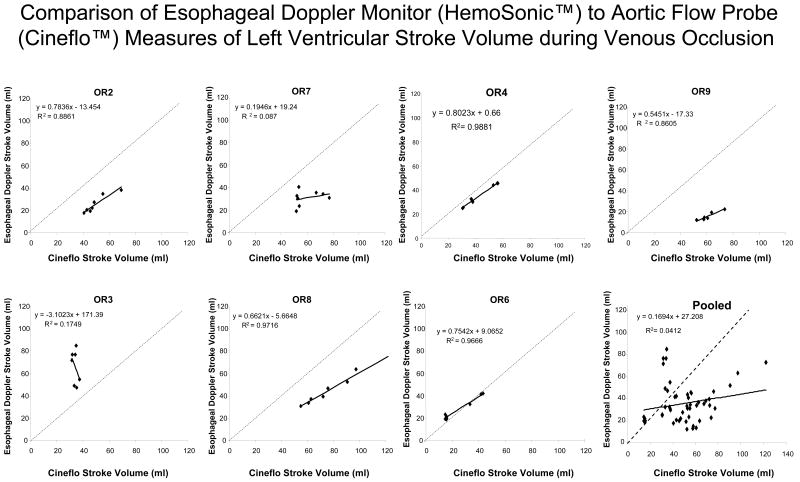

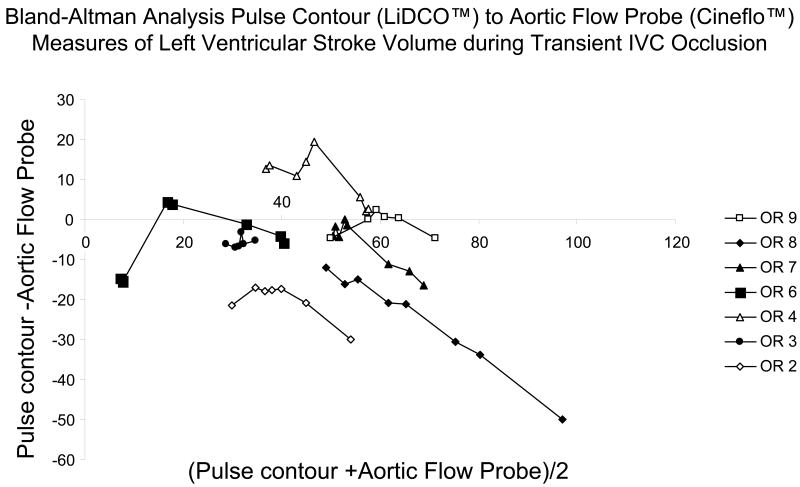

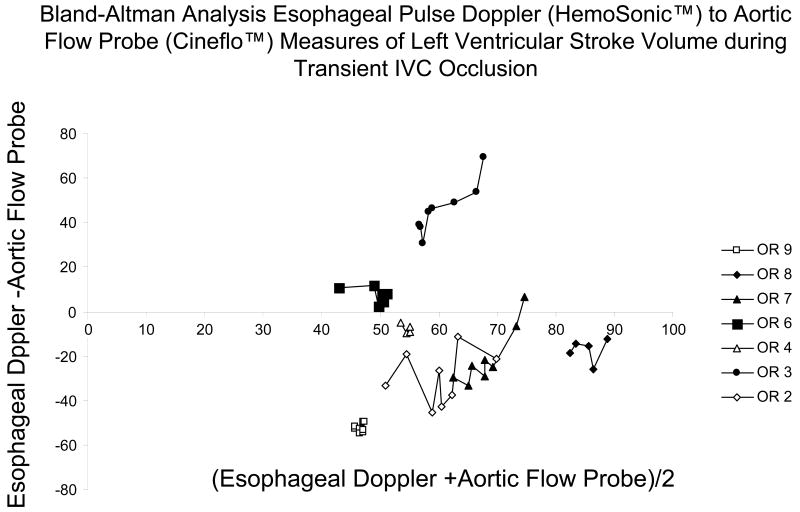

The relation between pulse power estimates of LV SV and LV SV measured by AFP during venous occlusion for all subjects is shown in figure 3 and for the EDM estimates of LV SV and LV SV measured by AFP during venous occlusion is shown in figure 4. In general, both devices closely tracked changes in AFP-derived measures of LV SV although their absolute SV values were occasionally different, especially for the EDM data (Fig. 4). In one subject (OR3), the EDM data varied more than AFP-measured LV SV, but in that study, LV SV changed only minimally during venous occlusion. On inspection of OR3 raw flow signals, unlike the other 6 subjects, we identified a shifting AFP baseline during the venous obstruction maneuver making estimates of LV SV from the device's algorithm inaccurate. Another venous occlusion maneuver without such baseline shifts was available for the pulse power analysis for that subject. The difference between transesophageal echocardiographic and EDM estimates aortic cross sectional diameter were minimal (Table 1). Although individual subjects pulse power and EDM estimates of SV tended to track dynamic changes in LV SV as measured by the AFP, pooled data for both methods was less robust, suggesting that dynamic changes in estimated LV SV need to be limited to the same subject and not to pooled data. Importantly, the dynamic changes shown in figures 3 and 4 for individual subjects did not have similar precision or bias when pooled for the Bland-Altman analyses (figs 5 and 6) for pulse contour and EDM, respectively. Both devices displayed a good degree of precision across the LV SV range, but also displayed a significant and unpredictable bias. This bias persisted when apneic steady state LV SV values were also compared (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Regression analysis for arterial pulse power-derived stroke volume (LiDCO™) versus aortic flow probe-derived stroke volume (Cineflo™ stroke volume) for all subjects.

Figure 4.

Regression analysis for esophageal Doppler monitor-derived stroke volume versus aortic flow probe-derived stroke volume (Cineflo™ stroke volume) for all subjects.

Figure 5.

Bland-Altman Analysis for all subjects comparing pulse power-derived stroke volumes (LiDCO™) with aortic flow probe-derived stroke volumes during venous occlusion.

Figure 6.

Bland-Altman Analysis for all subjects comparing esophageal Doppler monitor-derived (HemoSonic™) stroke volumes with aortic flow probe-derived stroke volumes during venous occlusion.

Discussion

This study quantifies the accuracy of both an arterial pulse power and EDM devices to assess steady state LV SV and its dynamic changes as LV SV is rapidly varied by venous occlusion and release in humans. Not surprisingly, arterial pulse pressure changes were coupled to LV SV changes. These data underscore the use of pulse pressure variation as a surrogate of LV SV variation in clinical trials. Furthermore, both the pulse power and EDM methods, when displaying good quality signals, assessed to a good degree of accuracy in estimating LV SV (Table 1). Since both pulse power and EDM steady state measures tracked steady state LV SV, both can also be used to report the dynamic changes in mean aortic flow during passive leg raising that require measures averaged over 20 seconds (4,6). However, though the ability of either device to assess dynamic change in LV SV was only good for the pulse contour method and less so for the EDM.

The individual subject analysis shown of the pulse power device (Fig 5) shows that it faithfully reports AFP derived LV SV measures at lower LV SV values but tends to underestimate LV SV at higher LV SV values. Qualitatively similar but directionally opposite changes are seen with the EDM device (Fig 6). Thus, both pulse power and EDM values can be used clinically as surrogate measures of steady state SV, but only arterial pulse pressure and pulse power closely track LV SV under conditions of rapidly changing LV SV conditions. At lower LV SV values (i.e. LV SV <65 ml) pulse power accurately estimates absolute dynamic changes in LV SV as well. Importantly, De Castro et al. (14) estimated the variance of individual subjects LV SV using transesophageal Doppler and compared it to simultaneously measured LV SV by the PiCCO device pulse contour technique in 20 patients undergoing aortic surgery. They too found that mean LV SV values agreed between the devices but that LV SV variation measures had 10% variance, making its ability to tract small changes in LV SV variation marginal. These variances are similar to those we and others reported for the same PiCCO device in animal studies (9,15). Since the LiDCO and PiCCO devices use different qualities of the arterial pressure pulse to calculate LV SV, these qualitative differences between the Bland-Altman analysis for LiDCO™ and PiCCO™ may reflect fundamental differences in their calculation algorithms. Thus, clinical validation studies need to be device-specific if they are to be used to validate the accuracy of a device to assess dynamic changes in LV SV.

Why is it important that these devices assess dynamic changes in LV SV accurately? Prior studies have shown that beat-to-beat variations in aortic pulse pressure during positive-pressure ventilation, quantified as pulse pressure variation, are very sensitive and specific measure of the ability of the heart to increase its output if subsequently challenged with a bolus intravascular fluid load (1,2,16). Furthermore, estimates of LV SV changes using arterial pulse contour analysis, quantified as LV SV variations, accurately predict volume responsiveness in surgery patients during large tidal volume ventilation (Vt 10 ml/kg) (5). Still, validation of the accuracy of these devices to reflect LV SV variation was lacking. Our study, therefore, documents a good correlation between dynamic LV SV changes and their estimates using pulse contour device but only a moderate correlation using the EDM device in humans. The quantification of the EDM device accuracy of these estimates is important because dynamic changes in aortic blood volume and the proportion of descending aortic to total aortic blood flow may also occur during positive-pressure breathing making the measures of dynamic LV SV changes from EDM estimates invalid. These EDM data agree with our experimental findings in an acute anesthetized canine model (9).

LiDCO™ pulse power analysis estimates stroke volume from the ventriculo-arterial coupling power transfer based upon work by Litton et al. (17) and validated by Belloni et al. (18). The calibration of this method requires an independent measurement of cardiac output to allow the initial calculation of the aortic input impedance. The lithium dilution method to estimate cardiac output used by LiDCO™ system has been validated against standard thermodilution cardiac output measurements (19,20,21), however up until now there have been no studies to validate the ability of LV SV variation measures to accurately reflect true dynamic changes in LV SV when LV SV has been measured directly.

The HemoSonic™ EDM is based upon the Doppler phase shift to derive a velocity signal (22). Signal processing involves converting the spectrum of the received Doppler shifts into velocity signals. The area of the velocity-time integral per beat corresponds to the distance a column of blood would move through the aorta during one cardiac cycle and has been termed the stroke distance (22,23). Stroke distance is an accurate representation of SV when compared with standard thermodilution methods (24-28). The coupling of aortic diameter with flow velocity improves the accuracy of the EDM to measure steady state changes in LV SV during resuscitation if arterial pressure varies because changes in arterial pressure proportional change aortic diameter (13). Our data suggests that the HemoSonic™ EDM measure of aortic diameter and velocity is accurate enough to calculate a LV SV.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH grants HL67181 and HL073198

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Michael R. Pinsky, MD is a member of the medical advisory board for LiDCO Ltd and was a medical advisory board for Arrow International. He has stock options with LiDCO Ltd. The remaining authors have not declared any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Michard F, Boussat S, Chemla D, et al. Relation between respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure and fluid responsiveness in septic patients with acute circulatory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:134–138. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9903035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michard F, Chemla D, Richard C, et al. Clinical use of respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure to monitor the hemodynamic effects of PEEP. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:935–939. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9805077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feissel M, Michard F, Mangin I, et al. Respiratory changes in aortic blood velocity as an indicator of fluid responsiveness in ventilated patients with septic shock. Chest. 2001;119:867–873. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.3.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monnet X, Rienzo M, Osman D, et al. Response to leg raising predicts fluid responsiveness during spontaneous breathing or with arrhythmia. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1402–1407. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215453.11735.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godje O, Thiel C, Lam MP, et al. Less invasive, continuous hemodynamic monitoring during minimally invasive coronary surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:1532–1536. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00956-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monnet X, Rienzo M, Osman D, et al. Esophageal Doppler monitoring predicts fluid responsiveness in critically ill ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1195–1201. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2731-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valtier B, Cholley BP, Belot JP, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of cardiac output in critically ill patients using transesophageal Doppler. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:77–83. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9707031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JJ, Dreyer WJ, Chang AC, et al. Arterial pulse wave analysis: An accurate means of determining cardiac output in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7:532–535. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000243723.47105.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunn S, Kim HK, Harrigan P, Pinsky MR. Ability of aortic pulse contour and esophageal pulsed Doppler measures to estimate changes in left ventricular output. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1537–1546. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansen JR. Standard pulse contour methods are not applicable in animals. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1084–1085. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0415-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorcsan J, Gasior TA, Mandarino WA, et al. Assessment of the immediate effects of cardiopulmonary bypass on left ventricular performance by on-line pressure area relations. Circulation. 1994;89:180–190. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monnet X, Chemla D, Osman D, Anguel N, Richard C, Pinsky MR, Teboul JL. Measuring aortic diameter improves accuracy of esophageal Doppler in assessing fluid responsiveness. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:477–482. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254725.35802.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solus-Biguenet H, Fleyfel M, Tavernier B, et al. Non-invasive prediction of fluid responsiveness during major hepatic surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:808–816. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeCastro V, Goarin JP, Hotel L, et al. Comparison of stroke volume and stroke volume respiratory variation measured by the axillary artery pulse=contour method and by aortic Doppler echocardiography in patients undergoing aortic surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:605–610. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubitz JC, Annecke T, Forkl S, Kemming GI, Kronas N, Goetz AE, Reuter DA. Validation of pulse contour derived stroke volume variation during modifications of cardiac afterload. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98:591–597. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Convertino VA, Cooke WH, Holcomb JB. Arterial pulse pressure and its association with reduced stroke volume during progressive central hypovolemia. J Trauma. 2006;61:629–634. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196663.34175.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linton R, Band D, O'Brien T, et al. Lithium dilution cardiac output measurement: A comparision with thermodilution. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1796–1800. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199711000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belloni L, Pisano A, Natale A, et al. Assessment of fluid-responsiveness parameters for off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: a comparison among LiDCO, transesophageal echochardiography, and pulmonary artery catheter. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;22:243–248. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bock J, Barker B, Mackersie R, et al. Cardiac Output Measurement Using Femoral Artery Dilution in Patients. J Crit Care. 1989;4:106–111. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakka SG, Reinhart K, Meier-Hellmann A. Comparison of pulmonary artery and arterial thermodilution cardiac output in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:843–846. doi: 10.1007/s001340050962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tibby SM, Hatherill M, Marsh MJ, et al. Clinical validation of cardiac output measurements using femoral artery thermodilution with direct Fick in ventilated children and infants. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:987–991. doi: 10.1007/s001340050443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singer M, Clarke J, Bennett ED. Continuous hemodynamic monitoring by esophageal Doppler. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:447–452. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198905000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singer M. Esophageal Doppler monitoring of aortic blood flow: beat-by-beat cardiac output monitoring. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1993;31:99–125. doi: 10.1097/00004311-199331030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mark JB, Steinbrook RA, Gugino LD, et al. Continuous noninvasive monitoring of cardiac output with esophageal Doppler ultrasound during cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 1986;65:1013–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freund PR. Transesophageal Doppler scanning versus thermodilution during general anesthesia. An initial comparison of cardiac output techniques. Am J Surg. 1987;153:490–494. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(87)90800-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Minagoe S, Thangathurai D, et al. Noninvasive measurement of cardiac output during surgery using a new continuous-wave Doppler esophageal probe. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:793–798. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90767-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seyde WC, Stephan H, Rieke H. Non-invasive Doppler-ultrasound determination of cardiac output. Results and experiences with the ACCUCOM. Anaesthesist. 1987;36:504–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel L, Shafer S, Martinez G. Simultaneous measurements of cardiac output by thermodilution, esophageal Doppler, and electrical impedance in anesthetized patients. J Cardiovasc Anes. 1988;2:590–595. doi: 10.1016/0888-6296(88)90049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]