Summary

Background

The co-existence of allergic conditions, food allergy, eczema, allergic rhinitis, asthma and anaphylaxis is thought to be increasing. Analysis of primary healthcare data-sets offers the possibility to advance understanding about the changing epidemiology of multiple allergic disorders.

Aim

To investigate recent trends in the recorded incidence, lifetime prevalence and consulting behaviour of patients with multiple allergic disorders in England.

Methods

QRESEARCH is one of the world's largest national aggregated health databases containing the records of over nine million patients (including those who have left or died). Data were extracted on all patients with a recorded diagnosis of multiple allergic disorders, and annual age–sex standardized incidence and lifetime period prevalence rates were calculated for each year from 2001 to 2005. We also analysed the consulting behaviour of these patients when compared with the rest of the QRESEARCH database population.

Results

The age–sex standardized incidence of multiple allergic disorders was 4.72 per 1000 person-years in 2001 and increased by 32.9% to 6.28 per 1000 patients in 2005 (p<0.001). Lifetime age–sex standardized prevalence of a recorded diagnosis of multiple allergic disorders increased by 48.9% from 31.00 per 1000 in 2001 to 46.16 in 2005 (p<0.001). Over this period, the mean consultation rate to general practitioners for these patients increased from 4.68 to 4.90 consultations per person per year.

Conclusions

Recorded incidence and lifetime prevalence of multiple allergic disorders in England have increased substantially in recent years.

Introduction

A recent review of UK epidemiological data has revealed that there has been an inexorable rise in the prevalence of allergic disorders.1 Allergic pathophyisiology can cause a spectrum of diseases in individuals, which may vary in severity. Atopy – a tendency to produce the IgE antibody in response to low doses of aeroallergens – is known to increase risk of developing allergic disorders such as food allergy, atopic eczema/dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and asthma.2 Data from blood measurements taken as part of the Health Survey for England in 2001 revealed that 42% of boys and 24% of girls aged 11–15 years were sensitive to the house dust mite (HDM) allergen (≥0.4kU/l HDM specific IgE)3 indicating the very high proportion of young people who are at high risk of manifesting allergic problems.

The presence of one allergic disorder significantly increases the risk of developing other allergic disorders affecting different organ systems.4,5 This has been attributed to the shared predisposition and mechanism for development of these diseases, whereby an immunological response to environmental allergens is driven by type 2 T cell cytokines.6 Both patients and healthcare providers find managing multiple allergies to be particularly problematic, with patients often requiring referrals to a number of different specialists.7

The Health Survey for England (HSE 1995 to 1997) found that 11% of children (2–15 years), 10% of young adults (16–44 years) and 5% of older adults (45+years) experienced multiple allergic disorders.1 While such survey data provide useful information on variations in period and lifetime prevalence of self-reported diagnoses of allergic disorders, particularly in children and adolescents, there are relatively little reliable national data describing clinician-diagnosed disease prevalence; furthermore very few data exist on the overall population trends over time for all ages.

Exploitation of large national healthcare data-sets, with their key strengths of large numbers and representative data, offers an important opportunity to develop insights into the epidemiology of multiple allergic disorders.8 Studying primary care databases provides a window onto overall national trends – something that is not possible with large scale surveys such as the International Study of Allergies and Asthma in Childhood (ISAAC), which has studied only children,9 and the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS), which has surveyed only adults.10 Large primary care data-sets, recording information at the point at which the majority of patients with multiple allergic disorders are likely to be managed does, however, offer an important opportunity to study changing patterns of disease. Building on previous work,11–13 we sought to describe recent trends in the primary care diagnosis of patients with multiple allergic disorders in England.

Methods

Version 10 of the QRESEARCH database was used for these analyses. This database contains representative anonymized aggregated health data derived from 525 general practices throughout the UK.9 Data were available for the period 1 January 1999–31 December 2005, these comprising of over nine million individual patients who collectively contributed over 30 million patient-years of observation. The method used to collect primary care data for the QRESEARCH database has been previously described.11

Patients were included in an analysis year if they were registered for the entire year of study. Patients with incomplete data (i.e. temporary residents, newly registered patients and those who joined, left or died during the study year) were excluded. Patients were considered to have an allergic disorder if they had a relevant computer-recorded diagnostic Read code (see below) in their electronic health record during the time period of interest.

Incidence was defined as the number of patients with a new case of having multiple allergic conditions diagnosed in a specific year, with the denominator being the number of patient-years of observation (calculated from the number of patients registered with practices and their length of registration). Lifetime prevalence was defined as the number of people having multiple allergic conditions ever recorded on at least one occasion in the GP records; the denominator used to calculate the lifetime prevalence rate was the number of patients registered with the study practices.

Definitions

An allergic condition was defined as patients who have the following: peanut allergy (SN582), eczema (M11.., M111., M113–4, M11z, M12z and below), allergic rhinitis (H17 and below, H18., Hyu21 and Hyu22), asthma (Read code H33 and below) or anaphylaxis (SN50 and below, SP34).

Statistical methods

Because of known age and sex variations, rates of disease and prescribing were standardized by sex and five-year age bands. The mid-year population estimates for England in each year of study were used as the reference population. These results were then used to estimate the numbers of people with multiple allergies in England. The Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test were used to investigate trends over time, this analysis being undertaken using EpiInfo2000 (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland).

Results

Number of patients with single and multiple allergic disorders

Between 2001 and 2005, the proportion of registered patients in QRESEARCH (2,958,366 patients) recorded as having at least one allergic condition increased from 18.9% to 24.2%, this representing a 28.0% (95% confidence intervals [CI] 28.0–28.1) relative increase. During the same period, the proportion of patients with recorded diagnoses of multiple (i.e. two or more) allergic conditions increased from 3.1% to 4.6% (a 50.0% [95% CI 49.9–50.1] relative increase).

Age–sex standardization of lifetime prevalence of patients with multiple allergic disorders and changes over time

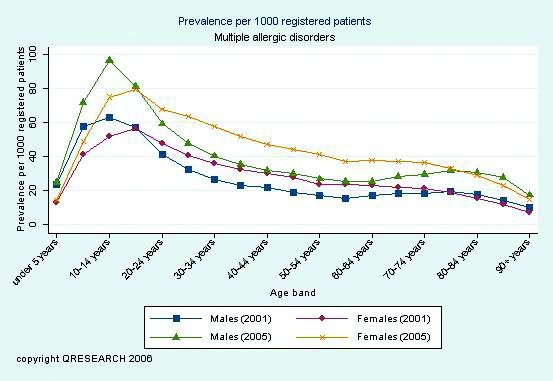

The lifetime prevalence of multiple allergic problems for 0–14-year-olds was 6.0% (95% CI 5.9–6.1), 5.4% in 15–44-year-olds (95% CI 5.3–5.5) and 3.3% (95% CI 3.2–3.4) for those aged over 45 years. Figure 1 shows the lifetime prevalence by age and sex per 1000 registered patients in QRESEARCH. Multiple allergic disorders were more common among women in people aged under 20 years or over 75 years. In 2005, the lifetime prevalence rate of multiple allergies was highest in boys aged 10–14 years.

Figure 1.

Lifetime prevalence of multiple allergic disorders per 1000 patients

During the five-year study period, the age–sex standardized lifetime prevalence of multiple allergic disorders increased by 48.9% (p<0.001) ( Table 1). At the end of 2005, approximately 1 in 22 people had a clinician-recorded diagnosis of having more than one allergic disorder. Scaling up these rates nationally, an estimated 2,312,100 (95%CI 2,299,800–2,324,500) people in England suffered from multiple allergic disorders in 2005.

Table 1.

Lifetime prevalence of multiple allergic disorders

| Year | Age–sex standardized lifetime prevalence rate per 1000 patients | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 31.00 | 30.80–31.21 |

| 2002 | 34.64 | 34.42–34.85 |

| 2003 | 38.54 | 38.31–38.76 |

| 2004 | 42.55 | 42.31–42.78 |

| 2005 | 46.16 | 45.91–46.40 |

Incidence rate of multiple allergic disorders and changes over time

During the five-year study period the number of incident cases per 1000 population increased by 32.9% (p<0.001) ( Table 2). In 2005, approximately 1 in every 159 people in England was newly diagnosed as having multiple allergic disorders.

Table 2.

Incidence of multiple allergic disorders

| Year | Age–sex standardized lifetime incidence rate per 1000 patient-years | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 4.72 | 4.64–4.81 |

| 2002 | 5.21 | 5.13–5.30 |

| 2003 | 5.59 | 5.50–5.67 |

| 2004 | 6.21 | 6.12–6.31 |

| 2005 | 6.28 | 6.19–6.37 |

Consultation rates for any reason for patients with multiple allergic disorders

In 2005, patients with multiple allergic diseases consulting a GP (regardless of the reason for consultation) did so an average of 4.9 times ( Table 3). Additionally, these patients consulted a nurse an average of 2.1 times a year.

Table 3.

Consultation rates for multiple allergic disorders per person per year by clinician

| Year | Clinician | Age–sex standardized rate per person per year | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | GP | 4.68 | 4.66–4.62 |

| Nurse | 1.57 | 1.56–1.57 | |

| 2002 | GP | 4.73 | 4.71–4.75 |

| Nurse | 1.71 | 1.70–1.72 | |

| 2003 | GP | 4.86 | 4.84–4.87 |

| Nurse | 1.87 | 1.86–1.87 | |

| 2004 | GP | 4.92 | 4.91–4.93 |

| Nurse | 2.00 | 1.99–2.01 | |

| 2005 | GP | 4.90 | 4.89–4.92 |

| Nurse | 2.11 | 2.10–2.12 |

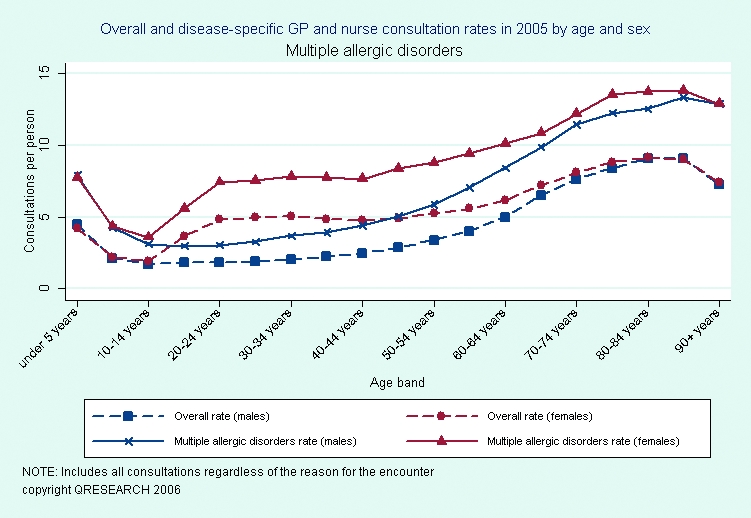

Figure 2 compares overall consultation rates for the whole QRESEARCH population with those for patients with multiple allergic diseases broken down by age and sex. This includes all GP and nurse consultations in 2005 regardless of the reason for the encounter. Consultation rates for women tended to be higher than for men and consultation rates for patients with multiple allergic disorders were higher than overall consultation rates. For example, for men aged 85–89 years, the GP and nurse consultation rate for patients with a diagnosis of multiple allergic disorders was 13.4 (95% CI 13.0–13.7) compared with the overall rate of 9.1 (95% CI 9.1–9.2) per person.

Figure 2.

Overall consultation rates compared with those for multiple allergic disorders, for all GP and nurse consultations in 2005

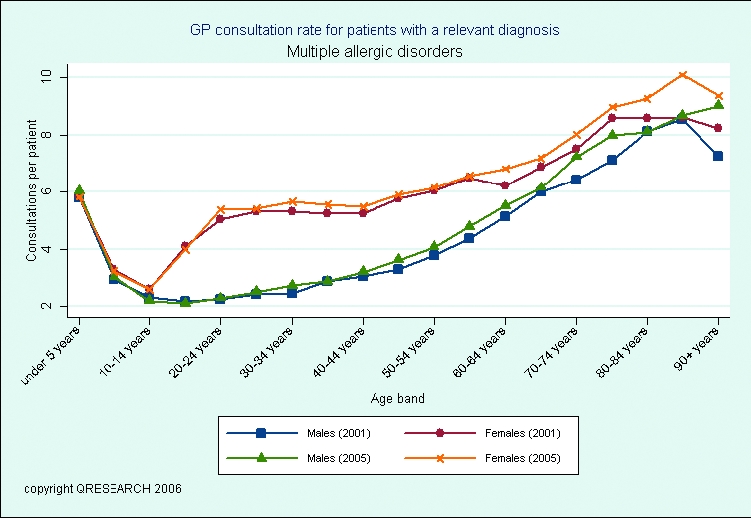

Figure 3 shows consultations rates per patient (regardless of the reason for the consultation) for multiple allergic diseases broken down by age and sex. The highest consultation rate was 10.1 consultations per person (95% CI 9.9–10.4), which occurred in women aged 85–89 years.

Figure 3.

GP consultation rates per patient for multiple allergic disorders

Number of allergic conditions experienced

Table 4 shows the number and percentage of patients in QRESEARCH broken down by the number of cumulative allergic conditions suffered. For example, in 2005 there were a total of 2,958,366 registered patients of whom 2,243,128 (75.8%) patients did not suffer from any allergic conditions and five patients (0.0002%) suffered from all five allergic conditions. In 2005, 715,238 patients had at least one allergic disorder, with 135,497 (18.9%) of these patients presenting with an additional allergy.

Table 4.

Patients in QRESEARCH broken down by number of allergic disorders (n, %)

| Year | Number of allergic conditions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total | |

| 2001 | 2,322,895 (81.08) | 454,184 (15.85) | 77,699(2.71) | 10,067(0.35) | 91(0.0032) | 2(0.000070) | 2,864,938 |

| 2002 | 2,306,006 (79.79) | 485,117 (16.79) | 87,127(3.02) | 11,821(0.40) | 117(0.0040) | 2(0.000069) | 2,890,190 |

| 2003 | 2,291,287 (78.44) | 518,304 (17.74) | 97,823(3.35) | 13,594(0.47) | 167(0.0057) | 3(0. 000103) | 2,921,178 |

| 2004 | 2,249,191 (76.97) | 549,378 (18.80) | 107,666 (3.69) | 15,576(0.53) | 209(0.0072) | 4(0. 000137) | 2,922,024 |

| 2005 | 2,243,128 (75.82) | 579,741 (19.60) | 117,582 (3.98) | 17,669(0.60) | 241(0.0081) | 5(0.000169) | 2,958,366 |

Discussion

This study, using routine data from one of the world's largest national data-sets, has revealed that multiple allergic conditions now commonly occur in children and adults and that a large increase has occurred in the recorded incidence and lifetime prevalence of these problems in primary care in England during the period 2001–2005.

Main strengths and limitations of this work

The main strengths of this study include our interrogation of an extremely large nationally representative data-set, the fact that all contributing practices used the same computing systems for electronically recording clinical data and the approach used to ensure that all contributing practices were accustomed to electronically recording routine data. The study design employed ensured that there was no risk of selection bias due to non-responders or recall bias. Another strength of this study was the use of contemporaneous clinician recording of a diagnosis of allergic disorders as opposed to patient self-reporting of historical diagnoses or symptoms.9,10

There are a number of limitations related to the use of large routinely collected data from primary care, including: the dependence on clinician-recorded diagnosis of allergic disorders and the possible improvement in recording of allergic disorders over this time period. The relatively short time window over which trends were studied is another limitation, but this does also have the advantage of confining analysis to a period during which there were no changes in disease definition or classification. Data regarding childhood prevalence may be underestimated, as the ascertainment of disease present in the community will be dependent on parents bringing their children for consultation.14 There may have been an underestimate inthe rates of multiple allergic disorders reported. Firstly, egg and egg-protein allergy (SN580, SN581)was not included in the final analysis. Secondly, it has been previously reported that Read codes for allergy, in particular for food allergies, are missing, and therefore some practices may have had difficulties in recording some allergic disease.15

Comparison of findings with other published work

We found a lower lifetime prevalence of multiple allergic disorders when compared to the prevalence rates found using the HSE (QRESEARCH database: 0–14 years: 6.0%; 15–45 years: 5.4%; 45+ years 3.3% when compared to HSE: 2–14 years: 9%; 15–44 years: 8%; 45+ years 4%), this most probably reflecting differences between diagnosed disease prevalence (electronically recorded in general practice) and prevalence based on patient recall of doctor diagnosis, as is the case with the HSE.1

Meaning of the study results: possible mechanisms and implications for clinicians and policy-makers

There may be several possible reasons for this increase in multiple allergic disorders this including an increase in sensitization, which would then in turn predispose the development of any of a number of allergic disorders. Supporting evidence for such a possibility comes from an important study by Law et al. which found significant increases in atopic sensitization in the UK over a 25-year window.16 Increased predisposition to atopy,17 possibly reflecting changing exposure to known and unknown risk factors,18 may also be important. Increases in the rate of these conditions could however result from increased clinician awareness of allergic problems, which may then have led to improved identification and recording of allergic disorders. Similarly, increased patient awareness, or parental awareness of the potential of accessing effective treatments may have resulted in increased case presentation in primary care.

The House of Lords Allergy Inquiry published in 2007 has identified several issues highlighted by this work and other previous research that require further attention.19 In particular, given the large and possibly increasing numbers of people with multiple allergic problems, there is a need to invest in improved co-ordinated diagnosis, management and support for patients in order to reduce avoidable morbidity and inconvenience that many patients currently experience in moving between organ-based specialist care providers.

Conclusions and future research

This large national study reveals that the recorded incidence and lifetime prevalence of patients with multiple allergic disorders increased in England during the first half of this decade, which may reflect a genuine increase in the incidence of multiple allergic disorders, improved awareness, diagnosis and recording in primary care, or, perhaps most plausibly, a combination of genuine increases and improved identification and recording. Future work needs to try and distinguish between these different possible explanations. A key related important unanswered question concerns the quality of care and symptom control of these patients.20 Given the relatively higher prevalence of multiple allergic problems in children when compared with adults, the overall numbers of people in England with multiple allergic problems is, for the present at least, likely to continue to increase.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS —

Competing interests JHC is Director of QRESEARCH (a not-for-profit organization owned by the University of Nottingham and EMIS, commercial supplier of computer systems for 60% of GP practices in the UK). CS, JN and AS have no competing interests

Funding NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre

Ethical approval Ethics approval was not required as this analysis was conducted using only anonymized data

Guarantor JHC

Contributorship AS, JHC and JN were involved in designing the studyand CS contributed to literature searches and led the drafting of the paper with all co-authors commenting on drafts of the manuscript

Acknowledgements

We would like to record our thanks to the contributing EMIS practices and patients and to EMIS for providing technical expertise in creating and maintaining QRESEARCH. We thank QRESEARCH staff (Govind Jumbu, Alex Porter, Justin Fenty, Mike Heaps and Richard Holland) for their contribution to data extraction, analysis and presentation. These findings have been reported in Primary care epidemiology of allergic disorders: analysis using QRESEARCH database 2001–2006, which is published by the NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre

References

- 1.Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan DP, Anderson HR. Burden of allergic disease in the UK: secondary analyses of national databases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:520–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Academy of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. See http://www.eaaci.org/allergydefinitions/english.htm (last checked 10 April 2008)

- 3.Bajekal M, Primatesta P, Prior G, editors. Health Survey for England 2001. London: The Stationery Office; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuksel H, Dinc G, Sakar A, et al. Prevalence and comorbidity of allergic eczema, rhinitis, and asthma in a city in western Turkey. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2008;18:31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viinanen A, Munhbayarlah S, Zevgee T, et al. Prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and allergic sensitization in Mongolia. Allergy. 2005;60:1370–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holgate ST. The epidemic of allergy and asthma. Nature. 1999;402:B2–B4. doi: 10.1038/35037000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy ML, Price D, Zheng X, Simpson C, Hannaford P, Sheikh A. Inadequacies in UK primary care allergy services: National survey of current provisions and perceptions of need. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:518–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anandan C, Simpson CR, Fischbacher C, Sheikh A. Exploiting the potential of routine data to better understand the disease burden posed by allergic disorders. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:866–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Variations in the prevalence of respiratory symptoms, self-reported asthma attacks, and use of asthma medication in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) Eur Respir J. 1996;9:687–95. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09040687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheikh A, Hippisley-Cox J, Newton J, Fenty J. Trends in national incidence, lifetime prevalence and adrenaline prescribing for anaphylaxis in England. J Roy Soc Med. 2008;101:139–43. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.070306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghouri N, Hippisley-Cox J, Newton J, Sheikh A. Trends in the epidemiology and prescribing of medication for allergic rhinitis in England. J Roy Soc Med. 2008;101:466–72. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.080096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.QRESEARCH and the Information Centre for health and social care. Primary care epidemiology of allergic disorders: analysis using QRESEARCH database 2001–2006. 2007 See http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/allergdisorder/HSCICallergiesreportfromQRESEARCHJune2007[1].pdf (last checked 10 May 2008)

- 14.McKeever TM, Lewis SA, Smith C, Collins J, Heatlie H, Frischer M. Early exposure to infections and antibiotics and the incidence of allergic disease: A birth cohort study with the West Midlands General Practice Research Database. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:43–50. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson CR, Anandan C, Fischbacher C, Lefevre K, Sheikh A. Will SNOMED-CT improve our understanding of the disease burden posed by allergic disorders? Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1586–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Law M, Morris JK, Wald N, Luczynska C, Burney P. Changes in atopy over a quarter of a century, based on cross sectional data at three time periods. BMJ. 2005;330:1187–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38435.582975.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tariq SM, Matthews SM, Hakim EA, Stevens M, Arshad SH, Hide DW. The prevalence of and risk factors for atopy in early childhood: a whole population birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:587–93. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosges R, Klimek L. Today's allergic rhinitis patients are different: new factors that may play a role. Allergy. 2007;62:969–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.House of Lords Science and Technology Committee. 6th Order of Session. Allergy – Volume I: Report. London: The Stationery Office; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheikh A, Khan-Wasti S, Price D, Smeeth L, Fletcher M, Walker S. Standardized training for healthcare professionals and its impact on patients with perennial rhinitis: a multi-centre randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:90–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]