Abstract

Development of a subunit vaccine for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) depends on the identification of antigens that induce appropriate T cell responses. Using bioinformatics, we selected a panel of 94 Mtb genes based on criteria which included growth in macrophages, up- or down-regulation under hypoxic conditions, secretion, membrane association, or because they were members of the PE/PPE or EsX families. Recombinant proteins encoded by these genes were evaluated for IFN-γ recall responses using PBMC from healthy subjects previously exposed to Mtb. From this screen, dominant human T-cell antigens were identified and 49 of these proteins, formulated in CpG, were evaluated as vaccine candidates in a mouse model of tuberculosis (TB). Eighteen of the individual antigens conferred partial protection against challenge with virulent Mtb. A combination of three of these antigens further increased protection against Mtb to levels comparable to those achieved with BCG vaccination. Vaccine candidates that led to reduction in lung bacterial burden following challenge induced pluripotent CD4 and CD8 T cells, including TH1 cell responses characterized by elevated levels of antigen-specific IgG2c, IFN-γ and TNF. Priority vaccine antigens elicited pluripotent CD4 and CD8 T responses in PPD+ donor PBMC. This study identified numerous novel human T cell antigens suitable to be included in subunit vaccines against TB.

Keywords: Human T cell antigens, mycobacteria, vaccination

Introduction

Tuberculosis is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and is one of the leading causes of mortality due to infectious disease worldwide (1). Nearly one-third of the world’s population is infected with Mtb, with approximately 25 million people actively infected and 8.8 million new cases arising each year (2). Upon infection with Mtb, active disease develops in about 10% of subjects within 1 - 2 years of the initial exposure. The remainder of those infected with Mtb enters a state of latent infection, which can reactivate at a later stage, particularly in the elderly or in immuno-compromised individuals.

The high mortality associated with Mtb infection occurs despite the widespread use of a live, attenuated TB vaccine Mycobacterium bovis, bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG). BCG appears to be effective at preventing disease in newborns and toddlers, but not pulmonary tuberculosis in adults (3, 4). The variable efficacy afforded by BCG vaccination and the absence of a TB vaccine protective in adults have been the primary rationale for our approach to identify immunodominant Mtb antigens that could be used in a subunit vaccine to boost immune responses leading to improved protection. There is a new urgency for a TB vaccine as the WHO recently reported alarming rates of “multi-drug resistant” and “extensively drug-resistant” TB (5), mostly because of improper observance of a lengthy and costly drug regimen treatment.

Protective immunity to TB is conferred by TH1 CD4 and effector CD8 T cells (6), and it is recognized that an effective TB vaccine requires the generation of a T cell-mediated immune response. Thus far, many of the dominant Mtb T-cell antigens have been associated with proteins expressed by Mtb growing in macrophages, up- or down-regulated under hypoxic conditions, required for reactivation, membrane-associated, secreted, or represented by virulence factors such as PE/PPE or EsX (7, 8). Several promising subunit vaccine candidates have been developed using antigens among these protein classes [reviewed in (9, 10)].

Choosing the right adjuvant or delivery platform is critical to the success of a subunit vaccine. In this study, we used the oligodeoxynucleotide CpG, a Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR-9) ligand, as an adjuvant based on its reported ability to potentiate TH1 CD4 and CD8 T cell responses [reviewed in (11)].

Our approach to vaccine antigen discovery has been to identify relevant human T cell antigens that elicit dominant TH1 responses and to evaluate these antigens in appropriate adjuvant formulations in animal models. Taking advantage of the published genome sequence of Mtb (12), we used bioinformatic selection criteria to identify genes of interest including protein secretion, induction during growth in macrophages, up- or down-regulation in response to low oxygen or carbon source, and/or selection of members in the EsX or PE/PPE families. Recombinant proteins were made for 94 Mtb genes and evaluated with human PBMC from healthy purified protein derivative (PPD)- and PPD+ individuals for IFN-γ responses. A subset of 49 antigens adjuvanted with CpG oligonucleotides was tested prophylactically in mice using the Mtb aerosol challenge model. Antibody and cytokine responses to the vaccine antigens were characterized.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and purification of target antigens

DNA encoding selected Mtb genes were PCR amplified from HRv37 genomic DNA using Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR primers were designed to incorporate specific restriction enzyme sites 5′ and 3′ of the gene of interest for directional cloning into the expression vector pET28a (Novagen, Madison, WI). Purified PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes, ligated into pET28a using T4 DNA ligase (NEB), and transformed into XL10G cells (Stratagene). Recombinant pET28a plasmid DNA was recovered from individual colonies and sequenced to confirm the correctly cloned coding sequence. The recombinant clones contained an N-terminal six-histidine tag followed by a thrombin cleavage site and the Mtb gene of interest.

Recombinant plasmids were transformed into the E. coli BL21 derivative Rosetta2(DE3)(pLysS) (Novagen). Recombinant strains were cultured overnight at 37°C in 2X yeast tryptone containing appropriate antibiotics, diluted 1/25 into fresh culture medium, grown to mid-log phase (OD at 600 nm of 0.5 to 0.7), and induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG. Cultures were grown for an additional 3 to 4 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation, and bacterial pellets were stored at -20°C. Bacterial pellets were thawed and disrupted by sonication in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, followed by centrifugation to fractionate the soluble and insoluble material. Recombinant His-tagged protein products were isolated under native (soluble recombinant proteins) or denaturing (8M urea) conditions using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid metal ion affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer’s instructions (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Protein fractions were eluted with an increasing imidazole gradient and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Affinity-purified protein fractions were combined and dialyzed against 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, concentrated using Amicon Ultra 10-kDa-molecular-mass cutoff centrifugal filters (Millipore), and quantified using the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). LPS contamination was evaluated by the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay (Cambrex Corp., East Rutherford, N.J.). All the recombinant proteins used in this study showed residual endotoxin levels below 100 EU/mg of protein.

Human PBMC Assay

PBMCs were purified from heparinized blood obtained from 7 PPD- and 18 PPD+ healthy subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects and the study was approved by Western IRB, Seattle, WA. PBMCs were plated in triplicate at 2 - 2.5 × 105 cells/well and cultured with medium, PHA 10 μg/ml, Mtb lysate 10 μg/ml, or each recombinant protein 10 μg/ml for 72 h. Supernatants were harvested and analyzed for IFN-γ by a double-sandwich ELISA using specific mAb (eBioscience Inc., San Diego, CA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Values above mean background (medium) + 3 SD were considered positive.

Immunization, Challenge, & CFU

Female C57BL/6 mice, 5 - 7 week old, were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). All mice were maintained in IDRI animal care facility under specific pathogen-free conditions and were treated in accordance with the regulations and guidelines of IDRI Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were immunized (s.c.) three times, three wks apart with 6 or 8 μg protein in PBS and 25 μg of CpG1826 (Coley Pharmaceutical Group, Wellesley, MS) in a volume of 100 μl, except for the BCG group, which received a single dose of 5 × 104 CFU via the i.d. route (Pasteur strain, Sanofi Pasteur, Canada). Four wks after the last immunization, groups of seven mice were challenged by low dose aerosol exposure with Mtb H37Rv strain (ATCC #35718; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) using a UW-Madison aerosol exposure chamber (Madison, WI) calibrated to deliver 50 - 100 bacteria into the lungs. Vaccine efficacy was determined four wks post-challenge by harvesting lungs and spleen from the infected mice, homogenizing the tissues in PBS Tween-80 0.05%, plating five-fold serial dilutions on 7H10 agar plates (Molecular Toxicology Inc., Boone, NC) for bacterial growth, and counting CFU 2 wks later. Values ranging between 10 and 100 colonies were used to calculate the bacterial burden per organ and expressed as Log10 values. Vaccine induced protection is expressed as (Mean Log10 CFUsaline - Mean Log10 CFUvaccine).

Ab ELISA

Animals were bled 1 wk after the last immunization and serum IgG1 and IgG2c antibody titers were determined. Nunc-Immuno Polysorb plates were coated for 4 h at room temperature with 2 μg/ml of recombinant protein in 0.1 M bicarbonate buffer, blocked overnight at 4°C with PBS Tween-20 0.05% BSA 1%, washed with PBS Tween-20 0.05%, incubated for 2 h at room temperature with sera at a 1:50 dilution and subsequent 5-fold serial dilutions, washed, and incubated for 1 h with anti-IgG1-HRP or anti-IgG2c-HRP 1:2000 in PBS Tween-20 0.05% BSA 0.1%. Plates were washed and developed using SureBlue TMB substrate (KPL Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). The enzymatic reaction was stopped with 1N H2SO4, and plates were read within 30 min at 450 nm with a reference filter set at 650 nm using a microplate ELISA reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and SoftMax Pro5. Endpoint titers were determined with GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) with a cutoff of 0.1.

ELISPOT

MultiScreen 96-well filtration plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA) were coated with 10 μg/ml rat anti-mouse IFN-γ or TNF capture Ab (eBioscience) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed with PBS, blocked with RPMI 1640 and 10% FBS for at least 1 h at room temperature, and washed again. Splenocytes were plated in duplicate at 2 × 105 cells/well, and stimulated with medium, Con A 3 μg/ml, PPD 10 μg/ml, or each recombinant protein 10 μg/ml for 48 h at 37°C. The plates were subsequently washed with PBS and 0.1% Tween-20 and incubated for 2 h with a biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse IFN-γ or TNF secondary Ab (eBioscience) at 5 μg/ml in PBS, 0.5% BSA, and 0.1% Tween-20. The filters were developed using the Vectastain ABC avidin peroxidase conjugate and Vectastain AEC substrate kits (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The reaction was stopped by washing the plates with deionized water, plates were dried in the dark, and spots were counted on a automated ELISPOT reader (C.T.L. Serie3A Analyzer, Cellular Technology Ltd, Cleveland, OH), and analyzed with Immunospot® (CTL Analyzer LLC).

Flow cytometry

Splenocytes from immunized animals, or PBMC from healthy PPD+ subjects were plated at 1 - 2 × 106 cells/well in 96-well V bottom plates and stimulated with anti-CD28/CD49d (1 μg/ml each, eBioscience) and recombinant proteins (20 μg/ml) for 6 - 12 h at 37°C in the presence of GolgiStop (eBioscience). The cells were then fixed for 10 min with cytofix/cytoperm (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), washed in PBS BSA 0.1%, incubated with Fc block (anti-CD16/CD32, eBioscience) for 15 min at 4°C, stained with fluorochrome-conjugated mAb anti-CD3, CD8, CD44, IFN-γ, TNF, IL-2, Granzyme B (GrB, eBioscience) and CD4 (Caltag) in Perm/Wash buffer 1X (BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C, washed twice in Perm/Wash buffer, suspended in PBS and analyzed on a modified 3 laser LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Viable lymphocytes were gated by forward and side scatter, and 20,000 CD3/CD8 events were acquired for each sample and analyzed with BD FACSDiva software v5.0.1 (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test and standard 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test were used for statistical analysis; P values of 0.05 or less were considered significant.

Results

Antigen selection, expression, and purification

Mtb genes selected for testing human immune responses and as possible vaccine candidates, included (i) those genes that were required for growth in macrophages as defined by Sassetti and Rubin (13) (ii) those that were up- or down-regulated in response to oxygen and carbon limitation (14), (iii) mycobacterial specific genes within known immunogenic classes EsX and PE/PPE as based in Tuberculist (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/TubercuList/index.html) (iv) those identified as secreted by 2D PAGE and mass spectrometry analysis (http://www.mpiib-berlin.mpg.de/2D-PAGE/) and / or containing putative secretion signals. All targets were subjected to N-terminal signal sequence analysis and membrane spanning region using the SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) and TMPred (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html) programs. Predicted proteins were chosen containing less than three transmembrane regions and a MW between 6 - 70 kD, and low (< 30%) sequence homology within the human genome. DNA encoding selected Mtb genes was PCR amplified from H37Rv strain genomic DNA, cloned into the expression vector pET28a, and transformed into E. coli for recombinant protein expression. His-tagged protein products were isolated, affinity purified, identified on SDS-PAGE gel (data not shown), and tested for residual endotoxin. Mtb genes that failed to PCR, had low or no detectable expression, failed to purify to greater than 90% homogeneity, or contained more than 100 endotoxin units per milligram, were discarded. A total of 94 recombinant proteins were used in this analysis (Table I).

Table I. Categories of selected Mtb antigens.

| Secreted/Membrane | PE/PPE | EsX | Database | Growth in mϕ | Hypoxia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rv0054 | Rv1860 | Rv0915 | Rv0287 | Rv0952 | Rv0523c | Rv0363c |

| Rv0068 | Rv1886c | Rv1196 | Rv1793 | Rv1009 | Rv0655 | Rv0570 |

| Rv0125 | Rv1926c | Rv1789 | Rv3020 | Rv1174 | Rv0716 | Rv1240 |

| Rv0129c | Rv1932 | Rv1818c | Rv3619 | Rv1211 | Rv1099 | Rv1246c |

| Rv0153c | Rv1980c | Rv2608 | Rv3620c | Rv1253 | Rv1397c | Rv1738 |

| Rv0164 | Rv1984c | Rv3478 | Rv3874 | Rv1270c | Rv1410c | Rv1813c |

| Rv0390 | Rv2031 | Rv3875 | Rv1288 | Rv1569 | Rv2032 | |

| Rv0410 | Rv2220 | Rv1884c | Rv1589 | Rv2558 | ||

| Rv0455c | Rv2873 | Rv2389c | Rv1590 | Rv2623 | ||

| Rv0496 | Rv2875 | Rv2450 | Rv1908 | Rv2624c | ||

| Rv0577 | Rv3029c | Rv2520c | Rv3541c | Rv2626c | ||

| Rv0733 | Rv3246 | Rv3204 | Rv3587 | Rv2801c | ||

| Rv0831c | Rv3310 | Rv3211 | Rv3611 | Rv2866 | ||

| Rv0909 | Rv3628 | Rv3407 | Rv3614 | Rv3044 | ||

| Rv0934 | Rv3804c | Rv3876 | Rv3129c | |||

| Rv1411 | Rv3841 | Rv3133 | ||||

| Rv1511 | Rv3881 | Rv3810 | ||||

| Rv1626 | ||||||

Human PBMC cytokine responses to Mtb antigens

Candidate antigens were initially prioritized based on their abilities to stimulate PBMCs from PPD+ (but not PPD-) donors to secrete IFN-γ. The donors used for the screening were tuberculin skin test (TST)-positive, disease-free, and healthy. Antigens from the RD1 region that are deleted in M. bovis BCG, such as ESAT-6 (Rv3875), were able to elicit responses from these PBMCs. Out of 94 proteins tested, 72 %, or 68 proteins elicited positive IFN-γ responses by PBMCs from PPD+, but not PPD- donors (Fig. 1A). Responses to the proteins were compared to those elicited by Mtb lysate in PPD+ (2.79 ± 0.25) and PPD- (0.05 ± 0.12), and PHA (4.40 ± 0.27 and 2.59 ± 0.47 respectively). Hundred percent of the PPD+ donors recognized Mtb lysate (data not shown) and a set of 28 proteins (Fig. 1B). Another set of 49 antigens was recognized by 67 - 90 % of the subjects, and overall, all the antigens tested were recognized by at least 44 % of the PPD+ donors. Of the 28 antigens recognized by all donors, 7 were PE/PPE or EsX proteins, 6 were hypoxia-associated, 6 were identified by database searches, 5 were secreted/membrane proteins, and 4 were associated with Mtb survival in macrophages.

Figure 1.

Levels of IFN-γ released by antigen-stimulated human PBMC were measured in vitro. PPD+ and PPD- PBMC were incubated for 72 h in medium, PHA (10 μg/ml), Mtb lysate (10 μg/ml), or Mtb recombinant proteins (50 μg/ml). Antigens are grouped according to the selection criteria: m, membrane-associated; S, secreted proteins; P, PE/PPE; E, EsX; M, macrophage growth required; H, hypoxic response; D, database searches. (A) IFN-γ in supernatants was measured by sandwich ELISA. Mean (MeanAg - MeanMedium) ± SEM are shown for PPD+ (n=18) and PPD- (n=7) PBMC. (B) Percent of PPD+ positive responders.

Protection afforded by Mtb antigens adjuvanted with CpG

Recombinant Mtb proteins inducing the highest levels of IFN-γ in the PBMC assays and % of positive responders were then tested for protective efficacy in a mouse model of TB. The number of viable bacilli (CFU) in the lungs of C57BL/6 mice immunized with Mtb proteins adjuvanted with CpG was determined 4 wks post aerosol challenge with a low dose of virulent Mtb H37Rv or Erdman strains. 20 Mtb antigens were tested at IDRI in 7 independent experiments using H37Rv for challenge, 22 Mtb antigens were tested at CSU under NIH TB Vaccine Testing and Research Material Contract in 4 independent experiments using the Erdman strain for challenge, and 6 Mtb antigens were tested by both laboratories. No differences in protection outcome were observed when using Mtb H37Rv or Erdman (data not shown), therefore indicating that both strains can be used interchangeably in this study. Each experiment included unvaccinated (saline) and BCG control groups, along with 8 - 10 groups of different antigens with CpG (7 mice per group). Mean lung Log10 CFU in the various experiments ranged for the unvaccinated groups from 5.76 - 6.71 and from 4.30 - 5.82 for BCG vaccinated mice (data not shown). Variations are often important in the aerosol model of TB, rendering direct comparison of CFU difficult due to differences in infection levels between experiments. Therefore, an accepted way of comparing the relative efficacy of a vaccine is to calculate the mean difference of CFU observed between unvaccinated and vaccinated groups.

Out of 48 proteins formulated with CpG, 30 produced no reduction in lung CFU, and 12 induced a small decrease in bacterial counts (0.1 - 0.3 Log10). Six antigens; three secreted (Rv0577, Rv1626, and Rv2875), two PE/PPE (Rv2608, and Rv3478), and one hypoxic protein (Rv3044) elicited > 0.3 Log10 reduction in lung CFU (Table II). Interestingly, the two PE/PPE proteins, Rv3478 and Rv2608 in combination with CpG, resulted in the greatest decrease in viable Mtb bacilli (0.66 and 0.58 Log10, respectively). Rv0577, Rv1626, Rv2875, and Rv3044 reduced lung CFU by 0.36, 0.32, 0.44, and 0.43 Log10, respectively. As a comparison, three injections of Rv1886 (Ag85B, part of TB vaccines currently in clinical trials) + CpG or one injection of 104 viable BCG reduced lung CFU by 0.20 and 0.78 Log10, respectively. CpG adjuvant alone did not reduce lung CFU (< 0.1 Log10). Reduction in CFU > 0.2 Log10 were reproducible and generally statistically significant (P < 0.05) by 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test (data not shown). Protection observed with weaker antigens was more variable from experiment to experiment and, due to the high number of animals that would have been required, experiments were not powered to detect statistical significance for CFU reduction < 0.2 Log10.

Table II. Vaccine-induced protection against Mtb.

| CFU Reduction (Log10) ± SEMa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 0.1 | 0.1 - 0.3 | > 0.3 | |||||

| Rv0164b | Rv2450 | Rv0496 | 0.11±0.08 | Sc | Rv0577 | 0.36±0.07 | Sc |

| Rv0410 | Rv2623 | Rv0733 | 0.23±0.10 | S | Rv1626 | 0.32±0.07 | S |

| Rv0455 | Rv2626 | Rv0831 | 0.13±0.06 | S | Rv2608 | 0.58±0.16 | P |

| Rv0655 | Rv2801 | Rv1411 | 0.11±0.11 | S | Rv2875 | 0.44±0.18 | S |

| Rv0952 | Rv2866 | Rv1569 | 0.12±0.05 | M | Rv3044 | 0.43±0.06 | H |

| Rv1211 | Rv2945 | Rv1789 | 0.15±0.16 | P | Rv3478 | 0.66±0.15 | P |

| Rv1270 | Rv3029 | Rv1813 | 0.14±0.14 | H | BCG | 0.78±0.07 | |

| Rv1410 | Rv3133 | Rv1860 | 0.19±0.07 | S | |||

| Rv1590 | Rv3204 | Rv1886 | 0.20±0.04 | S | |||

| Rv1738 | Rv3407 | Rv2220 | 0.25±0.11 | S | |||

| Rv1818 | Rv3541 | Rv3020 | 0.17±0.07 | E | |||

| Rv1884 | Rv3620 | Rv3619 | 0.24±0.05 | E | |||

| Rv1926 | Rv3628 | ||||||

| Rv1984 | Rv3810 | ||||||

| Rv2032 | CpG | ||||||

| Rv2389 | (-0.09±0.05) | ||||||

Reduction of viable bacteria (CFU) in the lungs of immunized animals compared to saline controls 4 wks after a low dose aerosol challenge with M. tuberculosis H37Rv and/or Erdman strains. Data represent the mean of 2 - 3 independent experiments ± SEM for antigens inducing > 0.1 log reduction. Antigens inducing < 0.1 log reduction in lung CFU in the first screening were considered not protective and not repeated for ethical concerns to reduce the number of animals used in these studies.

Mice were immunized s.c. three times, three wks apart with 8 μg Mtb antigens (Rv#) + 25 μg CpG, or i.d. one time with 5×104 BCG.

Antigen category: S, secreted; P, PE/PPE; E, EsX; M, growth in macrophages; H, regulated under hypoxic growth

These results are very promising as the levels of protection against Mtb infection achieved with two of the antigens (adjuvanted with CpG) were close to those obtained with the more complex BCG vaccine.

Immunogenicity of vaccine candidate antigens

Experiments were conducted to investigate the T and B cell responses induced against the vaccine candidates. C57BL/6 mice were immunized three times 3 weeks apart with antigen and CpG. Antigen-specific antibody titers and cytokine responses were determined one week and three weeks, respectively, after the last boost.

At the antibody level, higher IgG2c responses were measured in response to 17 antigens, 18 antigens showed mixed IgG2c/IgG1 antibodies, and one antigen induced higher IgG1 (Table III). Rv0577, Rv1886, Rv2608, Rv2875, Rv3044, Rv3478, and Rv3619 induced Log10 IgG2c antibody titers ranging from 4.2 to 5.9, and Log10 IgG1 titers ranging from 3.8 to 5.7 (Fig. 2A), while no IgG2c or IgG1 to Rv1626 could be detected (data not shown). The antigen-specific IgG2c responses were predominant for all the proteins but two (Rv0577, Rv1886), as indicated by an IgG2c:IgG1 ratio >1 (Fig. 2B). Differences in antigen-specific IgG2c versus IgG1 antibody titers were found statistically significant (P < 0.05) for Rv2875, Rv3044, and Rv3619 using Student’s t test.

Table III. Immunogenicity of Mtb antigens.

| Reduction in CFU > 0.3 Log10a | Reduction in CFU 0.1 - 0.3 Log10 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen | IFN-γb | TNFb | IgGc | Antigen | IFN-γ | TNF | IgG |

| Rv0577 | 523±8 | 388±297 | 0.98 | Rv0496 | 68±52 | 24±5 | *1.21 |

| Rv1626 | 20±21 | 268±117 | *1.19 | Rv0733 | NDd | ND | ND |

| Rv2608 | 798±11 | 175±105 | 1.09 | Rv0831 | 24±12 | 24±8 | *1.19 |

| Rv2875 | 428±172 | 137±60 | *1.05 | Rv1411 | 187±36 | ND | 1.00 |

| Rv3044 | 331±161 | 57±1 | *1.05 | Rv1569 | ND | ND | ND |

| Rv3478 | 453±4 | 149±73 | 1.03 | Rv1789 | ND | ND | ND |

| Rv1813 | 388±103 | 32±13 | *1.18 | ||||

| Rv1860 | ND | ND | ND | ||||

| Rv1886 | 590±106 | 102±37 | 1.00 | ||||

| Rv2220 | ND | ND | ND | ||||

| Rv3020 | 48±27 | 20±16 | *1.18 | ||||

| Rv3619 | 604±184 | 1261±319 | *1.13 | ||||

| Reduction in CFU < 0.1 Log10 | |||||||

| Antigen | IFN-γ | TNF | IgG | Antigen | IFN-γ | TNF | IgG |

| Rv0164 | 163±87 | 94±58 | *1.17 | Rv2389 | 39±49 | 92±31 | 1.02 |

| Rv0410 | ND | ND | ND | Rv2450 | 148±104 | 4±4 | 0.97 |

| Rv0455 | 24±12 | 44±24 | 1.06 | Rv2623 | 21±12 | 2±1 | *1.14 |

| Rv0655 | ND | ND | ND | Rv2626 | 95±30 | 7±4 | 0.95 |

| Rv0952 | 100±83 | 14±5 | 1.03 | Rv2801 | ND | ND | ND |

| Rv1211 | 12±4 | 0±0 | 1.00 | Rv2866 | 104± 56 | 32±12 | *1.31 |

| Rv1270 | 8±4 | ND | 1.01 | Rv2945 | ND | ND | ND |

| Rv1410 | ND | ND | ND | Rv3029 | 116±29 | 6±2 | *1.25 |

| Rv1590 | 28±24 | 4±8 | *2.12 | Rv3133 | 24±8 | 12±8 | *1.94 |

| Rv1738 | 24±16 | 32±16 | 1.23 | Rv3204 | 8±13 | 5±7 | *2.10 |

| Rv1818 | 155±72 | 10±2 | *0.90 | Rv3407 | ND | ND | ND |

| Rv1884 | 1600±372 | ND | 1.01 | Rv3541 | ND | ND | ND |

| Rv1926 | 41±64 | 12±21 | 1.08 | Rv3620 | 184± 44 | 72±33 | *1.13 |

| Rv1984 | 344±210 | 70±49 | 1.09 | Rv3628 | 16±8 | ND | 1.09 |

| Rv2032 | 28±16 | ND | *1.14 | Rv3810 | 44±56 | 7±10 | 1.08 |

Antigens are displayed based on efficacy at reducing lung bacterial burden.

SFU per million cells (SD). Mice were immunized s.c. three times, three wks apart with Mtb antigens (Rv#) + CpG. Cytokine responses to the antigens were determined by ELISPOT 3 wks after the last injection.

IgG2c:IgG1 ratio

P < 0.05, Student’s t Test

ND, not done.

Figure 2.

Antibody responses to Mtb recombinant antigens were measured in sera isolated from mice vaccinated with Rv0577, Rv2875, Rv1886, Rv2608, Rv3478, Rv3619, Rv3620, Rv1813, and Rv3044 + CpG. Sera were tested for antigen-specific IgG1 and IgG2c antibody. (A) Mean of reciprocal dilution + SEM, and (B) IgG2c:IgG1 ratios are shown. *P < 0.05, Student’s t-Test. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

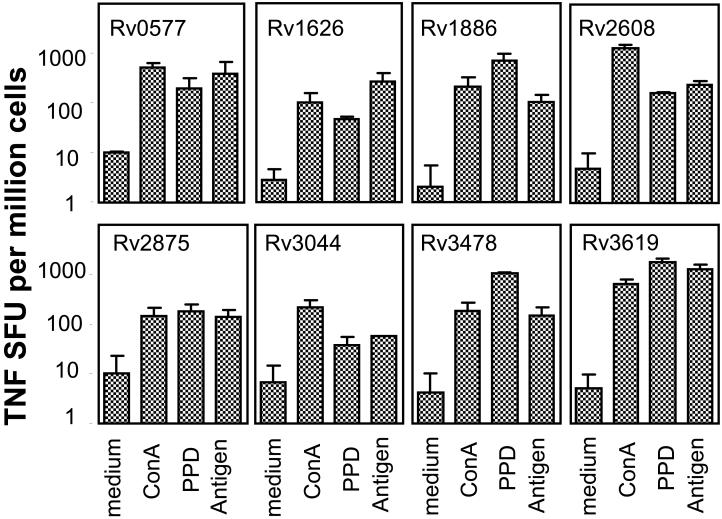

At the cytokine level, all the Mtb antigens associated with > 0.3 Log10 reduction in lung bacterial burden induced high levels of IFN-γ- (Table III and Fig. 3) and/or TNF-producing cells (Table III and Fig. 4). Mtb antigens associated with 0.1 - 0.3 Log10 reduction in CFU induced mixed levels of IFN-γ- and/or TNF-producing cells, with half of the antigens tested showing high levels of one or both cytokines. Finally, Mtb antigens associated with < 0.1 Log10 reduction in CFU induced lower frequencies of IFN-γ- and/or TNF production, with notable exceptions, including Rv1884, Rv1984, and Rv3620. Splenocytes from immunized mice responded to in vitro stimulation with Con A, and to various levels with PPD (Fig. 3 - 4), and Mtb lysate (data not shown). Splenocytes from saline and CpG control groups showed positive cytokine responses upon in vitro stimulation with Con A, and background levels only in response to antigenic stimulation (data not shown).

Figure 3.

IFN-γ responses to Mtb recombinant antigens were determined in vaccinated mice. Splenocytes were prepared from animals immunized with Rv0577, Rv1626, Rv1813, Rv1886 (85B), Rv2875, Rv2608, Rv3619, Rv3620, Rv3044, and Rv3478 + CpG or saline, 3 wks after the last injection, and tested for IFN-γ in vitro recall responses. Cells were plated in duplicate at 2 × 105 cells/well and cultured with medium, Con A (3 μg/ml), PPD (10 μg/ml), or each recombinant antigen (10 μg/ml) for 48 h. Frequencies of IFN-γ-secreting cells (spot-forming unit, SFU) were determined by ELISPOT. Mean + SD (n = 5 mice) shown are representative of two independent experiments.

Figure 4.

TNF responses to Mtb recombinant antigens were determined in vaccinated mice. Splenocytes were prepared from animals immunized with Rv0577, Rv1626, Rv1813, Rv1886 (85B), Rv2875, Rv2608, Rv3619, Rv3620, Rv3044, and Rv3478 + CpG or saline, 3 wks after the last injection, and tested for TNF in vitro recall responses. Cells were plated in duplicate at 2 × 105 cells/well and cultured with medium, Con A (3 μg/ml), PPD (10 μg/ml), or each recombinant antigen (10 μg/ml) for 48 h. Frequencies of TNF-secreting cells (SFU) were determined by ELISPOT. Mean + SD (n = 5 mice) shown are representative of two independent experiments.

CD4 and CD8 T cell expression of multiple cytokines and effector molecules in response to antigenic stimulation were further determined at the single cell level by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) and flow cytometry using a modified 3-laser LSRII FACS analyzer. Cytokine profiles were analyzed on a limited subset of Mtb antigens, identified as partially protective at the time of the study, and compared to the ones obtained with Rv1886. Expression of IFN-γ, TNF, and/or IL-2 by CD3/CD4/CD44high T cells (antigen experienced, Fig. 5A) and CD3/CD4/CD44low T cells (naïve, data not shown) was determined. CD44high, but not CD44low CD4 T cells from immunized mice produced two or more cytokines in response to in vitro antigenic stimulation. Rv1886 showed the greatest CD4 T cell response with cells staining positive predominantly for IFN-γ/TNF and TNF/IL-2. Rv3619 was the next best, followed by Rv3620, Rv2608, Rv3478, and Rv1813. Cells staining positive for the three cytokines were seen in response to Rv3478, Rv3619, and Rv3620, that is, three of the six vaccines tested. CD4/CD44high and CD4/CD44low T cells from saline control mice showed only background levels of cells positive for multiple cytokines.

Figure 5.

Antigen-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell cytokine responses were analyzed in vaccinated mice. Splenocytes, isolated from animals immunized with Rv1813, Rv3620, Rv2608, Rv3619, Rv3478, or Rv1886 + CpG, or saline, were plated at 2 × 106 cells/well and cultured with medium, or each recombinant antigen (20 μg/ml) for 12 h in the presence of GolgiStop. (A) CD4 T cells were identified by ICS based on CD3 and CD4 expression, and further gated as CD44high (antigen experienced) or CD44low (naïve). The percent of cells expressing two cytokines or more of IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2 were determined. Means (n = 3) are shown. (B) CD8 antigen specific T cells were identified by ICS as CD3/CD44high/CD8 cells also positive for IFN-γ and/or TNF, and further analyzed for their content in GrB. Numbers of cytokine+ (IFN/TNF) and cytokine+GrB+ per million splenocytes were determined. Mean ± SD (n = 3 mice) shown are representative of two independent experiments.

Effector memory CD8 T cells were identified by ICS as CD3/CD44highCD8 cells staining positive for IFN-γ and/or TNF upon antigen stimulation in vitro, and were further analyzed for their content in GrB (Fig. 5B). Rv1813 showed the greatest number of CD8 T cells positive for either or both cytokines, followed by Rv3620, Rv3619, and Rv2608. Cell responses to Rv3478 were the lowest. More than 50 % of the cells positive for IFN-γ and/or TNF also contained GrB, a protein of the lytic machinery of cytotoxic T cells.

Taken together, these results show that these novel Mtb antigens adjuvanted with CpG induced potent TH1-type CD4 and CD8 effector T cell immune responses in C57BL/6 mice.

Combination of multiple antigens increased protection against challenge with Mtb

We hypothesized that combining multiple antigens would lead to increased reduction in bacterial burden following Mtb infection. We used Rv2608, Rv1813, and Rv3620 which were the first antigens we identified as inducing partial protection against Mtb. Mice were injected 3 times 3 wks apart with single antigens + CpG, a mixture of the 3 antigens + CpG, CpG alone, or BCG. The number of viable bacilli (CFU) in the lung of mice from the different immunized groups was compared (Fig. 6A). In this experiment, Rv1813 and Rv2608 adjuvanted with CpG reduced the number of lung bacteria by 0.30 Log10 (P < 0.01) and 0.25 Log10 (P < 0.05), respectively, while immunization with Rv3620 + CpG was ineffective (0.05 Log10, P > 0.05). The weak protection we observed with Rv3620 in our initial experiment that led to its inclusion in the combination was not confirmed in this or subsequent experiments. Nevertheless, with 0.67 Log10 reduction (P < 0.01), the effect of the three antigens combined was greater than that seen with any single antigen and comparable to vaccination with BCG (0.71 Log10, P < 0.01).

Figure 6.

The efficacy of a combination of three antigens adjuvanted with CpG was addressed. Mice were immunized s.c. three times, three wks apart with 25 μg CpG, 8 μg single antigen + CpG, 6 μg of each antigen + CpG (“3 Ags+CpG”), or once i.d. with 5×104 BCG. Four weeks after the last boost, mice were challenged with Mtb H37Rv. (A) The number of viable bacteria (CFU Log10) in the lungs was determined 4 wks post-challenge. One way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test was used for statistical analysis;* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. (B) Mice were bled one week after the last boost and sera were tested for antigen-specific IgG2c antibody. Mean of reciprocal dilution + SD (n = 3 mice) are shown. (C - D) Splenocytes were isolated from the vaccinated animals three wks after the last boost, plated in duplicate at 2 × 105 cells/well, and cultured with medium, Con A (3 μg/ml), PPD (10 μg/ml), or each recombinant antigen (10 μg/ml) for 48 - 72 h. (C) IFN-γ levels measured by ELISA in 72 h supernatants. (D) Frequencies of TNF-secreting cells (SFU) determined by ELISPOT. Mean + SD (n = 3 mice) shown are representative of two independent experiments.

Immunization with the selected antigen combination resulted in significant production of antigen-specific IgG2c antibodies (Fig. 6B). IgG2c titers to Rv3620 were increased by 1.3 Log10 (P < 0.05) in mice receiving the three antigens compared to animals injected with Rv3620 only. Additional T-dependent help provided by the other two antigens might explain this difference as Rv3620 is a small 10 kD protein. Antigen-specific IgG1 was also detected (data not shown). IgG2c:IgG1 ratios were > 1 for all groups showing antigen-specific antibodies, consistent with a predominant TH1 response. Mice immunized with CpG alone did not show IgG2c or IgG1 specific responses to either antigen. In contrast, IFN-γ and TNF responses were essentially restricted to Rv2608, and diminished in the group receiving the antigen combination compared to the single antigen (Fig. 6C - D). The reduced cytokine responses in the group receiving the 3 antigens + CpG can at least partially be attributed to the fact that these animals were immunized with less protein (6 μg versus 8 μg for the single antigen groups) in order to use a dose of < 20 μg antigen total per injection. We observed in other infection models that immunizing mice with more than 20 μg of antigen was detrimental (R. Coler, unpublished observations).

Human T cell responses to vaccine candidate antigens

Human PBMCs from a 6 healthy PPD+ subjects with documented prior exposure to Mtb were HLA typed (Pudget Sound Blood Center, Seattle, WA): D160 (HLA-A2/3, B14/44, DR4/13, DQ1/7), D204 (HLA-A3/68, B27/35, DR7/15, DR51/53, DQ6/9), D336 (HLA-A2/3, B7/44, DR4/13, DQ1/7), D365 (HLA-A1/2, B7/8, DR2/3, DQ1/2), D366 (HLA-A2/24, B60, DR4, DQ3), and D368 (HLA-A2/29, B44, DR15/4, DQ0602/0301). CD4 and CD8 T cell cytokine responses to PPD and the 9 most protective antigens were analyzed by ICS at the single cell level. We also looked at responses to Rv1813 and Rv3620 because of their possible additive effect when used in combination with Rv2608. Memory T cells were gated on expression of CD3/CD4/CD45RO or CD3/CD8/CD45RO molecules, and the data reflects the percentage of cells staining positive for IFN-γ, TNF, or the two cytokines after background (media control) removal. PPD and PI stimulation induced CD4 T cells staining positive for IFN-γ, TNF, and/or the two cytokines in all subjects (Fig. 7). CD4 T cell responses to the different Mtb antigens were more variable among donors, with mixed profiles consisting most of the time of cells positive for a single cytokine (IFN-γ or TNF), and cells expressing both cytokines. For CD8 T cells, PI stimulation induced positive responses for IFN-γ, TNF, and the two cytokines in all subjects, while PPD induced IFN-γ, and IFN-γ + TNF, but not TNF alone (Fig. 8). Most of the CD8 T cell responses to Mtb antigens were IFN-γ, or/and IFN-γ + TNF. Overall, each antigen was recognized by subjects with a diversity of HLA by either CD4 or/and CD8 T cells.

Figure 7.

Human PPD+ CD4 T cells respond to recombinant Mtb antigen stimulation. PBMC from 6 healthy PPD+ subjects with diverse HLA types were incubated for 12 h in medium, PPD (10 μg/ml), or recombinant antigens (20 μg/ml) in the presence of anti CD28/CD49d and GolgiStop. T cells were identified by ICS based on CD3 expression, and further gated as CD4/CD45RO memory T cells. Percent of CD4 T cells expressing IFN-γ, TNF, or the two cytokines in response to a panel of Mtb antigens are shown.

Figure 8.

Human PPD+ CD8 T cells respond to recombinant Mtb antigen stimulation. PBMC from 6 healthy PPD+ subjects with diverse HLA types were incubated for 12 h in medium, PPD (10 μg/ml), or recombinant antigens (20 μg/ml) in the presence of anti CD28/CD49d and GolgiStop. T cells were identified by ICS based on CD3 expression, and further gated as CD8/CD45RO memory T cells. Percent of CD8 T cells expressing IFN-γ, TNF, or the two cytokines in response to a panel of Mtb antigens are shown.

Discussion

With the goal of identifying antigens for use in a human TB vaccine, we performed the most comprehensive analysis to date of human T cell antigens of Mtb. From selected genome mining, we chose approximately 100 potential candidates to be expressed as recombinant proteins and evaluated for IFN-γ recall responses using PBMCsfrom healthy PPD+ subjects. Based on PBMC results, a subset of 48 antigens was selected to be administered to mice in a CpG formulation, with 18 of them conferring partial protection against challenge with virulent Mtb H37Rv and/or Erdman strains. A combination of three of these antigens further increased protection against TB to levels comparable to those achieved with BCG vaccination. Induction of predominant TH1 CD4 responses by vaccine antigens were observed in mice with reduced lung bacterial burden.

Recall secretion of IFN-γ by pathogen-exposed cells is a relevant marker for cellular immune responses in Mtb infections, and has been used as a rationale for antigen selection for potential vaccines [reviewed in (8, 15)]. With 94 Mtb proteins evaluated for antigenicity on PPD+ donor PBMCs, our study considerably expands the number of Mtb proteins tested so far. Most of the proteins (79) were widely recognized as indicated by positive IFN-γ production by PBMC from > 70 % of the subjects. Of the 79 proteins, 28 were recognized by all PPD+ donors tested. HLA typing of a subset of donors indicated a wide heterogeneity in MHC class I and II alleles suggesting that these antigens contain epitopes recognized by a wide range of different HLA molecules. The promiscuous recognition of antigens by individuals with a wide variety of ethnic origin is of major importance in the context of human vaccines.

We and others have demonstrated the feasibility of using protein subunit vaccines against leishmaniasis (16) and TB (17, 18) with vaccines currently in clinical trials. Unlike DNA vaccines, protein-based vaccines are immunogenic in small animal models, non-human primates and humans. Properly adjuvanting Mtb proteins, however, is the key to the induction of strong in vivo immune responses. In this study, we used CpG as an adjuvant based on its reported ability to potentiate TH1 CD4 and CD8 T cell responses (11, 19). To favor the selection of potent antigens, we chose a relatively low dose of CpG as an adjuvant. Under these conditions, we observed only a modest reduction in lung bacterial counts (0.20 Log10) following immunization with Rv1886 (Ag85B), previously reported to have protective capacity (18), lower than some of the novel antigens reported herein.

We identified 17 previously uncharacterized antigens that were able to induce partial protection against Mtb in mice. Most of the antigens were either secreted or membrane-associated. Rv2608 and Rv3478 belong to the family of PE/PPE proteins which members have been shown to induce TH1 responses (20, 21) and confer protection against Mtb (22-24). The PE/PPE proteins have also been shown to have higher levels of polymorphism among Mtb clinical isolates variants (25). However no genetic variation was observed for Rv2608 or Rv3478 within recently published MDR and XDR genomes (http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/mycobacterium_tuberculosis_spp.9/ToolsIndex.html). Rv3020 and Rv3619 are members of the EsX family of virulence factors, among which several potential vaccine candidates have been described (26-30). Finally, Rv1813 and Rv3044 are proteins expressed by Mtb in conditions of low oxygen and are associated with latent growth of the bacteria (14). Identifying novel vaccine antigens within families of proteins known to induce potent immune responses further validates the bioinformatic approach. In this study, adjuvanting recombinant proteins with CpG proved effective at reducing bacterial burden, further extending results obtained with CpG-adjuvanted culture filtrate proteins (31) or BCG (32). Combining multiple Mtb antigens led to increased vaccine efficacy, extending observations from us and others using combination of antigens (33) or fusion proteins like Mtb72f, Ag85B-ESAT6, and Ag85B-TB10 (17, 18, 27, 34). Fusion proteins comprised of our newly-identified priority candidates are currently in development.

Strong TH1 CD4 responses and cytokines like IFN-γ and TNF are critical for protection against tuberculosis (35-39), while antibody responses are not considered to be involved in anti-mycobacterial adaptive immunity. In this study, we used the antigen specific IgG2c:IgG1 ratio as an indication of a predominant TH1 (> 1), mixed TH1/TH2 (= 1), or TH2 (< 1) response induced by vaccination. We show that vaccine-induced protection against challenge with Mtb in mice was associated with a TH1 response characterized by predominant serum IgG2c and high levels of IFN-γ and TNF. High frequencies of IFN-γ or TNF-producing cells, however, did not always correlate with lower lung bacterial counts, as exemplified by Rv1884 or Rv1984, suggesting that other factors are important to control the infection in mice, and extending observations by others (40-42). The ability of a vaccine to induce pluripotent T cell responses has been associated with increased protection in a mouse model of Leishmania; such a mechanism has also been proposed for M. bovis BCG vaccine (43). All the vaccine candidates induced effector memory CD4 T cells expressing at least two, if not all three of the cytokines among IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF, with Rv3478 and Rv3619 stimulating individual T cells to produce all three cytokines. Most importantly, when tested on PBMC isolated from 6 healthy subjects with confirmed exposure to Mtb, and who received chemotherapy, all the vaccine candidate antigens induced CD4 and/or CD8 T cell responses by PMBC from subjects with a diversity of HLA. Cytokine profiles were a mix of single and double IFN-γ + TNF expressing CD4 T cells, and predominantly IFN-γ and IFN-γ + TNF expressing CD8 T cells. This suggests that immune responses to these novel antigens naturally occur in individuals with diverse HLA types exposed to and cured of Mtb infection. This is of particular interest in the context of a vaccine that could be used to boost an existing immune response induced by infection. Because most of these antigens are also found in the BCG vaccine, they might be used in a BCG prime/protein boost regimen to improve upon BCG vaccination alone. We are currently expanding our approach by testing multiple antigen combinations in different adjuvant formulations for protection in different animal models of TB.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Irina Zharkikh, Elena Kristalinskaia, Valerie Reese, Tara Evers, Kevin urgan, Laura Appleby, and Jackie Whittle for their technical expertise, and Ajay Bhatia and Randall Howard for valuable discussions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI-044373, and AI-067251 to S. Reed, IDRI and by the NIH TB Vaccine Testing and Research Materials Contract N01-AI-40091 to A. Izzo, Colorado State University.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- BCG

bacillus Calmette-Guerin

- TB

tuberculosis

- PPD

purified protein derivative

References

- 1.WHO . Global Tuberculosis Control: Surveilance, Planning, Financing. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maartens G, Wilkinson RJ. Tuberculosis. Lancet. 2007;370:2030–2043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen P, Doherty TM. The success and failure of BCG - implications for a novel tuberculosis vaccine. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:656–662. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doherty TM, Andersen P. Vaccines for tuberculosis: novel concepts and recent progress. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:687–702. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.687-702.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . The WHO/IUTLD Global Project on Anti-Tuberculosis Resistance Surveillance. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world. Fourth global report. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flynn JL, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:93–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen P, Doherty TM. TB subunit vaccines--putting the pieces together. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sable SB, Kalra M, Verma I, Khuller GK. Tuberculosis subunit vaccine design: the conflict of antigenicity and immunogenicity. Clin Immunol. 2007;122:239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen P. Tuberculosis vaccines - an update. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:484–487. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufmann SH, Baumann S, Nasser Eddine A. Exploiting immunology and molecular genetics for rational vaccine design against tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:1068–1079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klinman DM. Adjuvant activity of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Int Rev Immunol. 2006;25:135–154. doi: 10.1080/08830180600743057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, 3rd, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12989–12994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherman DR, Voskuil M, Schnappinger D, Liao R, Harrell MI, Schoolnik GK. Regulation of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis hypoxic response gene encoding alpha -crystallin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7534–7539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121172498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skeiky YA, Sadoff JC. Advances in tuberculosis vaccine strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:469–476. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coler RN, Reed SG. Second-generation vaccines against leishmaniasis. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reed S, Lobet Y. Tuberculosis vaccine development; from mouse to man. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:922–931. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinrich Olsen A, van Pinxteren LA, Meng Okkels L, Birk Rasmussen P, Andersen P. Protection of mice with a tuberculosis subunit vaccine based on a fusion protein of antigen 85b and esat-6. Infection and immunity. 2001;69:2773–2778. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.2773-2778.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speiser DE, Baumgaertner P, Voelter V, Devevre E, Barbey C, Rufer N, Romero P. Unmodified self antigen triggers human CD8 T cells with stronger tumor reactivity than altered antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800080105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaitra MG, Nayak R, Shaila MS. Modulation of immune responses in mice to recombinant antigens from PE and PPE families of proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by the Ribi adjuvant. Vaccine. 2007;25:7168–7176. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakhaiyar P, Nagalakshmi Y, Aruna B, Murthy KJ, Katoch VM, Hasnain SE. Regions of high antigenicity within the hypothetical PPE major polymorphic tandem repeat open-reading frame, Rv2608, show a differential humoral response and a low T cell response in various categories of patients with tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1237–1244. doi: 10.1086/423938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dillon DC, Alderson MR, Day CH, Lewinsohn DM, Coler R, Bement T, Campos-Neto A, Skeiky YA, Orme IM, Roberts A, Steen S, Dalemans W, Badaro R, Reed SG. Molecular characterization and human T-cell responses to a member of a novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis mtb39 gene family. Infection and immunity. 1999;67:2941–2950. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2941-2950.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skeiky YA, Ovendale PJ, Jen S, Alderson MR, Dillon DC, Smith S, Wilson CB, Orme IM, Reed SG, Campos-Neto A. T cell expression cloning of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene encoding a protective antigen associated with the early control of infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:7140–7149. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vipond J, Vipond R, Allen-Vercoe E, Clark SO, Hatch GJ, Gooch KE, Bacon J, Hampshire T, Shuttleworth H, Minton NP, Blake K, Williams A, Marsh PD. Selection of novel TB vaccine candidates and their evaluation as DNA vaccines against aerosol challenge. Vaccine. 2006;24:6340–6350. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleischmann RD, Alland D, Eisen JA, Carpenter L, White O, Peterson J, DeBoy R, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Haft D, Hickey E, Kolonay JF, Nelson WC, Umayam LA, Ermolaeva M, Salzberg SL, Delcher A, Utterback T, Weidman J, Khouri H, Gill J, Mikula A, Bishai W, Jacobs WR, Jr, Venter JC, Fraser CM. Whole-genome comparison of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical and laboratory strains. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184:5479–5490. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.19.5479-5490.2002. Jr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandt L, Elhay M, Rosenkrands I, Lindblad EB, Andersen P. ESAT-6 subunit vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infection and immunity. 2000;68:791–795. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.791-795.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dietrich J, Aagaard C, Leah R, Olsen AW, Stryhn A, Doherty TM, Andersen P. Exchanging ESAT6 with TB10.4 in an Ag85B fusion molecule-based tuberculosis subunit vaccine: efficient protection and ESAT6-based sensitive monitoring of vaccine efficacy. J Immunol. 2005;174:6332–6339. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Attiyah R, Mustafa AS, Abal AT, El-Shamy AS, Dalemans W, Skeiky YA. In vitro cellular immune responses to complex and newly defined recombinant antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;138:139–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogarth PJ, Logan KE, Vordermeier HM, Singh M, Hewinson RG, Chambers MA. Protective immunity against Mycobacterium bovis induced by vaccination with Rv3109c--a member of the esat-6 gene family. Vaccine. 2005;23:2557–2564. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsen AW, Hansen PR, Holm A, Andersen P. Efficient protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis by vaccination with a single subdominant epitope from the ESAT-6 antigen. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1724–1732. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200006)30:6<1724::AID-IMMU1724>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wedlock DN, Skinner MA, de Lisle GW, Vordermeier HM, Hewinson RG, Hecker R, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S, Babiuk LA, Buddle BM. Vaccination of cattle with Mycobacterium bovis culture filtrate proteins and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides induces protection against bovine tuberculosis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;106:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freidag BL, Melton GB, Collins F, Klinman DM, Cheever A, Stobie L, Suen W, Seder RA. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and interleukin-12 improve the efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination in mice challenged with M. tuberculosis. Infection and immunity. 2000;68:2948–2953. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2948-2953.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalra M, Grover A, Mehta N, Singh J, Kaur J, Sable SB, Behera D, Sharma P, Verma I, Khuller GK. Supplementation with RD antigens enhances the protective efficacy of BCG in tuberculous mice. Clin Immunol. 2007;125:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skeiky YA, Alderson MR, Ovendale PJ, Guderian JA, Brandt L, Dillon DC, Campos-Neto A, Lobet Y, Dalemans W, Orme IM, Reed SG. Differential immune responses and protective efficacy induced by components of a tuberculosis polyprotein vaccine, Mtb72F, delivered as naked DNA or recombinant protein. J Immunol. 2004;172:7618–7628. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–2247. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Bloom BR. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2249–2254. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bean AG, Roach DR, Briscoe H, France MP, Korner H, Sedgwick JD, Britton WJ. Structural deficiencies in granuloma formation in TNF gene-targeted mice underlie the heightened susceptibility to aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, which is not compensated for by lymphotoxin. J Immunol. 1999;162:3504–3511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Botha T, Ryffel B. Reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection in TNF-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:3110–3118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denis B, Lefort A, Flipo RM, Tubach F, Lemann M, Ravaud P, Salmon D, Mariette X, Lortholary O. Long-term follow-up of patients with tuberculosis as a complication of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha antagonist therapy: safe re-initiation of TNF-alpha blockers after appropriate anti-tuberculous treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:183–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cowley SC, Elkins KL. CD4+ T cells mediate IFN-gamma-independent control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection both in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2003;171:4689–4699. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elias D, Akuffo H, Britton S. PPD induced in vitro interferon gamma production is not a reliable correlate of protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2005;99:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Majlessi L, Simsova M, Jarvis Z, Brodin P, Rojas MJ, Bauche C, Nouze C, Ladant D, Cole ST, Sebo P, Leclerc C. An increase in antimycobacterial Th1-cell responses by prime-boost protocols of immunization does not enhance protection against tuberculosis. Infection and immunity. 2006;74:2128–2137. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2128-2137.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darrah PA, Patel DT, De Luca PM, Lindsay RW, Davey DF, Flynn BJ, Hoff ST, Andersen P, Reed SG, Morris SL, Roederer M, Seder RA. Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major. Nat Med. 2007;13:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nm1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]