Abstract

Non-invasive measurement of cerebral venous oxygenation can serve as a tool for better understanding fMRI signals and for clinical evaluation of brain oxygen homeostasis. In this study, a novel technique, T2-Relaxation-Under-Spin-Tagging (TRUST) MRI, is developed to estimate oxygenation in venous vessels. This method utilizes the spin labeling principle to automatically isolate pure blood signals, from which T2 relaxation times are determined using flow-insensitive T2-preparation pulses. The blood T2 is then converted to blood oxygenation using a calibration plot. In vivo experiments gave a baseline venous oxygenation of 64.8±6.3% in sagittal sinus in healthy volunteers (n=24). Reproducibility studies demonstrated that the standard deviation across trials was 2.0±1.1%. The effects of repetition time and inversion time selections were investigated. The TRUST technique was further tested using various physiologic challenges. Hypercapnia induced an increase in venous oxygenation by 13.8± 1.1%. On the other hand, caffeine ingestion resulted in a decrease in oxygenation by 7.0±1.8%. Contrast agent infusion (Gd-DTPA, 0.1 mmol/kg) reduced venous blood T2 by 11.2ms. TRUST MRI is a useful technique for quantitative assessment of blood oxygenation in the brain.

Introduction

Venous oxygenation (Yv) is defined as the fraction of oxygenated hemoglobin in the venous blood, often given in units of percentage. In brain, it is reasonably understood that the typical range of venous oxygenation is 50–75% (1–9). Quantification of Yv is directly relevant to the Blood-Oxygenation-Level-Dependent (BOLD) fMRI. It is now well-known that the BOLD fMRI signal is a complex function of blood oxygenation, blood flow, and oxygen consumption of the brain (10). Therefore, evaluation of Yv can improve our understanding of BOLD signa l mechanisms and can also be used to estimate other physiologic parameters such as oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2).

Many of the Yv measurements used blood sampling or catheters in jugular veins (2,3), which are widely used in intensive care units but may not be practical for routine measurements in healthy controls or non-emergency patients. Therefore, non-invasive quantification of absolute blood oxygenation using MRI has been the goal of several studies (4,6,8,11,12). Utilizing the fact that blood T2 is dependent on oxygenation level, Wright et al. measured blood T2 in vena cava and converted it to Yv using an in vitro calibration plot (11). Oja et al. and Golay et al. applied similar principles to the venous vessels in the brain and estimated Yv during resting state and during visual stimulation (6,12). Haacke et al. and Fernandez-Seara et al. used the fact that the phase of a pure-blood voxel is dependent on oxygenation to estimate Yv (4,8). Furthermore, An et al. and He et al. have used a comprehensive model describing the T2/T2* effect of venous blood on extravascular tissue and conducted model fitting to estimate Yv (7,9). However, a major challenge that lays in studying the properties of pure blood is the isolation of the blood signal (i.e. having minimal partial volume effects from tissue or CSF), which is not a trivial task, in vivo, even in large blood vessels such as the sagittal sinuses, due to susceptibility to contamination of CSF space known as arachnoid granulations. In addition, rapid movement of blood (especially in larger vessels) presents a second technical challenge for studies aiming to accurately quantify blood properties.

Here, we apply a spin-labeling technique on the venous side (instead of on the arterial side as in conventional arterial spin labeling, or ASL (13–15)) and perform paired subtractions, just like in ASL data processing. This allows the subtracted image to contain only venous blood signal. The T2 relaxation time of this signal can then be determined, and can be converted to venous oxygenation (Yv in %) with a calibration plot (16,17). The T2-weighting is achieved by using a series of non-slice-selective T2-preparation pulses, rather than using conventional spin-echo sequence. This minimizes the outflow effect in blood T2 estimation. This technique was applied in a group of healthy controls, and various technical aspects were studied, including the choices of inversion time (TI) and repetition time (TR), as well as the measurement reproducibility. The technique was further evaluated using two vasoactive challenges, hypercapnia and caffeine ingestion. The effect of Gd-DTPA injection on blood T2 was also studied. This technique is dubbed T2-Relaxation-Under-Spin-Tagging (TRUST) MRI.

Materials and Methods

TRUST Pulse sequence

The TRUST MRI sequence diagram and the geometric locations of the labeling slab and imaging slice are shown in Fig. 1. This pulse sequence is similar to the PICORE ASL sequence (18), except that the labeling slab is above the imaging slice and a series of non-slice-selective T2-preparation pulses are inserted in front of the excitation pulse to modulate the T2-weighting. T2-preparation rather than conventional T2-refocusing is used to minimize the blood outflow effect in T2 measurement (19). Two schemes were applied to minimize the imperfection in the T2-prep pulses (20): 1) Composite pulses were used, i.e. 90x180y90x for the 180 pulses and 270x[−360x] for the −90 pulse. 2) The signs of the 180 pulses were arranged in a MLEV pattern (e.g. 1 1 −1 −1 etc). A complete sequence for TRUST MRI includes labeled and control scans acquired at different T2-weightings (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

TRUST MRI technique. (a) Pulse sequence diagram for TRUST MRI. The sequence consists of interleaved acquisitions of label and control scans, and each image type is acquired with four different eTEs ranging from 0 to 160 ms. For each scan, the sequence starts with a pre-saturation RF pulse to suppress the static tissue signal, followed by a labeling (or control) RF pulse to magnetically label the incoming blood. A brief waiting period (1.2 seconds) is allowed for blood to flow into the imaging slice. Before data acquisition, a non-selective T2-preparation pulse train is applied to achieve the T2-weighting, the duration of which is denoted eTE. The T2-preparation scheme, instead of conventional T2-weighted sequence, is used in order to minimize the blood outflow effect. (b) Geometric relationship between the imaging slice (yellow) and the labeling slab (green). Labeling slab thickness 50 mm, gap 25mm.

The theoretical framework of TRUST MRI is similar to that of ASL, but the scenario is simpler because the blood and static tissue compartments are strictly segregated in TRUST MRI (venous vessel walls are not permeable to water molecules), and therefore, there is no effect of proton exchange and relaxation rate switch (e.g. from blood T1 to tissue T1 in ASL) during the inversion time (21). For convenience, let us define the duration of the T2-prep sequence as effective TE (eTE), which is the additional T2-weighting generated by the T2-prep pulses. That is, the acquired MR signal is attenuated by the nominal TE (time between the excitation and acquisition) and by the eTE, the latter of which is relatively insensitive to blood outflow effect.

The total MR signal during the labeled scan is Slabel =Stissue + Sblood,label, and that during the control scan is Scontrol =Stissue + Sblood,control, in which the static tissue signal is identical for label/control scans and is given by:

| (1) |

where TI is the inversion time. This is essentially a saturation recovery equation. The blood signal in the labeled scan is given by:

| (2) |

in which the initial magnetization is assumed to be at equilibrium because a long TR (8 seconds) is used. The blood signal in the control scan is:

| (3) |

in which the signal decays from the equilibrium magnetization.

The difference signal can then be computed, in which the static tissue signals cancel out:

| (4) |

in which and C =1/T1b−1/T2b, and both terms are independent of eTE. We can therefore measure ΔS as a function of eTE and fit for the coefficients. The blood T2 is then given by:

| (5) |

Note that since T1b (assumed to be 1624ms (22)) is about 20 times greater than T2b and is relatively insensitive to blood oxygenation, the assumption of the T1b value has relatively small effect on the T2 estimation. We have tested the range of T1b from 1524ms to 1724ms (normal variation due to hematrocrit differences) (22), and have found that the resulting effect on the estimated T2b is only 0.24ms.

Simulations of the magnetization of static tissue, labeled blood, control blood, and the difference signal as a function of time (from the completion of the labeling RF pulse to the start of the excitation pulse) are shown in Fig. 2a. An experiment with eTE=40ms is shown in this example. To obtain T2 fitting, we can perform multiple experiments with different eTEs, and the simulations for a set of experiments with four eTEs are shown in Fig. 2b (only the difference signals are shown). The parameters used in the simulations were: TI=1200ms, T1,tissue=1165.5ms (23), T2,tissue=83.5ms (23), T2,tissue*=47.3ms (24), T1,blood=1624ms (22), T2,blood=54ms (17), T2,blood*=21ms (16).

Fig. 2.

Simulations of magnetization evolvement in TRUST MRI. (a) Temporal evolvement of the different pools of spins for an experiment with an effective TE of 40ms (eTE=40 ms, τCPMG=10ms, Four 180º pulses). The brown bar indicates the start of the T2-prep, from which time the magnetization decays exponentially at the rate of T2. The curves plotted are the magnetizations that affect the MR signal during reception, showing the longitudinal magnetizations before the yellow bar and the transverse magnetizations after the yellow bar. Simulation parameters: TI=1200ms, T1,tissue=1165.5ms, T2,tissue=83.5ms, T2,tissue*=47.3ms, T1,blood=1624ms, T2,blood=54ms, T2,blood*=21ms. (b) Simulation of the difference signals for a set of experiments with different eTEs. The τCPMG is fixed at 10ms and the number of 180º pulses varies. The signals acquired are proportional to the magnetizations at the end of the curves (Time=1200ms).

MRI experiments

MR experiments (3 Tesla, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) were performed on a total of 39 healthy subjects (age 31±7 years, range 19–48 years, 23 males and 16 females). The protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board. Informed written consent was obtained for each participant. The body coil was used for RF transmission and a head coil was used for receiving. Foam paddings were used to stabilize the head to minimize motion. The subjects were instructed not to fall asleep during the experiments (verified after the session), as the cerebral blood flow and venous oxygenation may change during sleep. Four effective TEs were used: 0ms, 40ms, 80ms and 160ms, corresponding to 0, 4, 8 and 16 refocusing pulses in the T2-preparation (τCPMG=10ms). Other Imaging parameters: FOV=230mm, matrix=64×64, single-shot EPI, slice thickness=5mm, TR=8000ms, TE=19ms, TI=1200ms, repetition=4, thickness of labeling slab = 50 mm, gap between labeling slab and imaging slice = 25 mm, scan duration 4 minutes and 16 seconds.

In a sub-group of healthy subjects (n=6), the intra-session reproducibility was evaluated by performing five TRUST MRI scans at approximately 10 minute intervals. The same slice locations and imaging parameters were used for the five scans.

In a sub-group of healthy subjects (n=5), TR dependence of the measurement was investigated by performing TRUST MRI using TR values of 1.5 seconds to 8 seconds at 0.5 second intervals (14 different TR values). All other parameters were identical as specified above. The durations for the scans depended on TR and varied from 48 seconds to 4 minutes and 16 seconds. In one subject, the TI dependence was investigated (with fixed TR) and the TI values varied from 200ms to 2600ms (13 different TI values). All other parameters were identical as specified above.

In two healthy subjects, hypercapnia challenge (by breathing through a plastic tube with 600ml of volume, thereby increasing the dead-space (25)) was induced and TRUST MRI was performed before, during, and after the challenge. End-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) was monitored throughout the experiment and was compared to MRI results.

In three healthy subjects, TRUST MRI was performed before and after 200mg caffeine tablet ingestion (26). The pre-caffeine scan was first performed. Then, while still inside the head coil, the subject was instructed to open his or her mouth for the researcher to place one tablet inside, and a small amount of water was administered via a straw to assist with swallowing. The MRI table was then repositioned to the iso-center. Twenty minutes later, the post-caffeine TRUST scan was performed. During the twenty minute waiting time, other anatomical scans (e.g. T1-weigthed anatomical imaging) were performed.

In three subjects, TRUST MRI was performed before and after the intravenous administration of Gd-DTPA contrast agent (Magnevist, Berlex Laboratories, Wayne, NY) at standard dosage (0.1 mmol/kg). The post-contrast TRUST was performed approximately 6 minutes after the injection of the contrast agent so that the agent concentration remained relatively constant for the duration of the TRUST scan.

Data analysis

Data were processed using in-house MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) scripts. After motion correction, pair-wise subtraction was performed for the control and label images to obtain the difference images for each eTE (e.g. Fig. 3a). For this study, we were primarily interested in venous oxygenation in the sagittal sinus. Therefore, an ROI covering the sagittal sinus region was manually drawn and, within this ROI, four voxels containing the largest difference signals in the eTE=0 image were selected as the mask for spatial averaging. The voxel number, 4, is chosen because we found that all subjects have at least 4 sagittal sinus voxels (at the resolution of 3.6×3.6×5 mm3) as visible in the difference image. Some subjects had greater sagittal sinus, but as long as we can accurately estimate the signal decay constant with 4 voxels, the other voxels do not have to be included. The effect of subjective ROI drawing and the number of voxels used are further discussed in the Results section.

Fig. 3.

An example of the TRUST MRI data. (a) MR images in which the venous blood is either magnetically labeled (Label, middle row) or unlabeled (Control, top row). Each type of image is acquired at four different T2-weightings, denoted by the effective TE (eTE). The bottom row is the subtracted image, Control-Label. The red rectangle indicates the ROI containing sagittal sinus. (b) The signals in the sagittal sinus in the difference image are fitted to a monoexponential function. Red symbols: experimental data. Black curve: fitting results. (c) The T2 value obtained from the curve fitting is converted to venous oxygenation (in %) based on a known relationship between oxygenation and blood T2.

The ΔS was fitted to Eqn. 4 (e.g. Fig. 3b) to obtain the exponent C, from which T2b was calculated by assuming a blood T1 of 1624ms (22). The T2b was then converted to blood oxygenation using the calibration plot shown in Fig. 3c. In addition, from the fitting procedure, the 95% confidence interval for the estimated parameters was also calculated (using Matlab routine nlparci.m). This gave an assessment of the uncertainty of the reported parameter values.

Results

Fig. 3a shows the control, label, and difference images at different effective TEs. Note that only large venous vessels (e.g. venous sinus) have discernable signal intensities in the difference image because of relatively large flow velocities. A region-of-interest (ROI) was drawn in the sagittal sinus area (red box in Fig. 3a) and the signals from 4 voxels with highest amplitudes were averaged. It is important to point out that the ROI drawing does not significantly affect the fitted T2 values, because the algorithm always finds the same peak voxels as long as the peak voxels are included in the ROI. The choice of number of voxels has a relatively small effect too. We tested using 4–8 voxels and the results showed minimal differences (<2ms) because the decay constant is approximately the same even though the S0 (in Fig. 3b) differs in different voxels. Fig. 3b shows the difference signals as a function of effective TE. The experimental data (in red) were fitted to a mono-exponential function (in black). It can be seen that excellent fitting was achieved and such fitting results were routinely obtained in the subjects. The fitting results for this dataset are also listed, giving S0 and T2 values of the venous blood. The resulting CPMG-T2 values were compared to a calibration curve (Fig. 3c) obtained from in vitro bovine blood measurements at similar conditions (16) (3T, CPMG multi-echo T2 sequence, tCPMG =10ms, courtesy of P. van Zijl and C. Clingman, Johns Hopkins University) to estimate Yv in the human subjects.

Over a group of twenty-four healthy controls, the CPMG-T2 in the sagittal sinus was found to be 62.4±12.0ms (mean±SD). The corresponding Yv was 64.8±6.3%. Comparing male and female groups, the male group (T2=58.0±11.5ms, n=16) had a significantly (Two-tailed Student t test, p=0.008) shorter T2 than the female group (T2=71.1±7.7ms, n=8), which could be due to oxygenation differences or hematocrit differences or a combination of both.

In a sub-group of eight subjects (4 males and 4 females), we compared the fitted blood T2 values using the difference signal (i.e. control-label) to that using the control signal only. The T2 values using the control signal were found to be significantly higher than that using the difference signal (p<0.0001, paired t test), consistent with the expectation of a slight contribution from CSF partial volume in those voxels. The T2 difference (5.3±1.8ms) translates to 2.6±1.2% over-estimation in Yv.

To test the robustness and reproducibility of the method, in a group of subjects (n=6), we performed 5 independent measures on each subject at 10 minute intervals (completely separate data processing, including the ROI drawings). Fig. 4 shows the time-courses and it can be seen that, while the inter-subject variations are considerable, the temporal stability of the measurements is excellent (variation across trials 2.0±1.1%). This is also demonstrated by the small error bars obtained from goodness-of-fit analysis. We therefore believe that the inter-subject variations are physiologic and reflect the normal variations among subjects. Such a range of normal variations are consistent with literature reports using jugular vein catheters (2,3).

Fig. 4.

Intra-session reproducibility of TRUST measurements. TRUST MRI experiments were performed five times at ten minute intervals within a one-hour scanning session. Each dataset was processed separately, i.e. ROIs were identified independently. Error bar indicates the standard error of estimated parameter as obtained from the goodness-of-fit assessment.

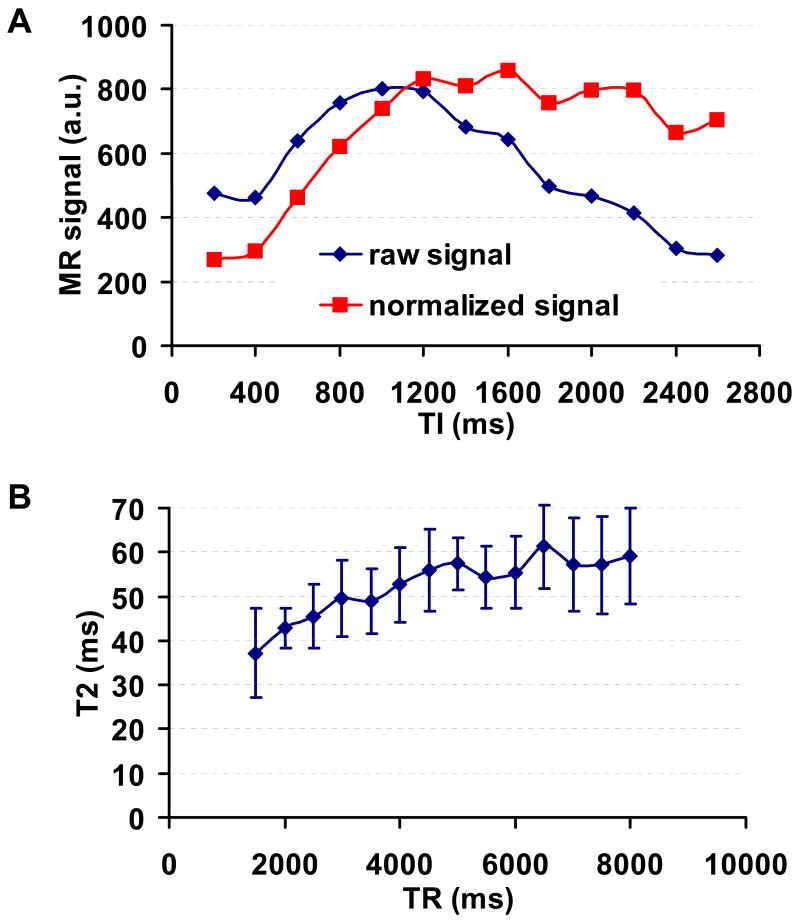

The choices of inversion time (TI) and repetition time (TR) were also investigated. Fig. 5a plots the difference MR signal as a function of TI. The “raw signal” simply indicates the difference signal (i.e. control-label). Considering that the labeling effect decays as a function of TI, a “normalized signal” was also calculated to estimate the number of inflowing spins in the imaging slice (i.e. (control – label)/2/exp(−TI/T1,b)). Note that in this case, the decaying effect is relatively easy to model, as there is no spin exchange between blood and tissue. Thus all spins relax at the T1 of blood. It was found that the arrival of labeled blood occurs as early as 200ms after the labeling RF pulse, and the signal (corrected for T1 decay of the labeling effect) continues to increase until reaching a plateau at about 1200ms (Fig. 5a). Therefore, TI was chosen to be 1200ms for all other experiments. Another advantage of choosing a TI that is greater than the blood nulling point (approximately 1088ms according to a blood T1 of 1624ms (22)) is that the blood magnetization will always be positive, avoiding the potential complication of determining the signs of the magnitude images. The TR dependence of the measured T2 was studied by performing TRUST MRI at TR values ranging from 1.5s to 8s at 500ms of interval. It can be seen that the T2 value increases as TR goes up, and plateaus at longer TR (Fig. 5b). Paired t test revealed that the T2 values at TR>6s was not significantly different from each other (threshold p=0.05, n=5). We therefore used TR of 8s for the rest of the experiments.

Fig. 5.

TI and TR dependences of TRUST MRI results. (a) TRUST MRI (eTE=0ms only) was performed using a range of TI values (from 200ms to 2600ms at 200ms of intervals). The signal intensities in the different images are plotted as a function of TI. The raw signal indicates the simple subtraction (Control-Label) without accounting for the effect of T1-related decay. The normalized signal denotes the signal after the correction (i.e. (Control-Label)/2/exp(−TI/T1,b)). Note that in this case, the decaying effect is relatively easy to model compared to ASL, as there is no spin exchange between blood and tissue. (b) TRUST MRI was performed using a range of TR values (from 1.5 to 8s at 0.5s of intervals). Each dataset is processed separately to obtain the blood T2 value, which is plotted as a function of TR. The error bars indicate the standard deviations across subjects.

Hypercapnia induced an oxygenation increase in the venous blood, as expected from a known effect of CBF increase (10). The EtCO2 before, during and after the hypercapnia challenge was 38.0±0.5 (mean±SD), 46.4±3.2 and 36.3±1.7 mmHg, respectively. The corresponding venous oxygenation was 62.9±5.8%, 76.0±1.2%, and 61.5±1.1%, respectively. On the other hand, caffeine challenge caused a drop in venous oxygenation by 7.0±1.8% (n=3), consistent with an expected vasoconstriction effect (26,27). The injection of a blood-pool contrast agent, Gd-DTPA, also reduced the venous blood T2 from 62.0±15.1ms to 50.8±8.0ms (n=3). This reduction is consistent with reported T2 relaxivity of this agent for the given dosage (28,29).

Discussion

In this study, we have developed a novel MR technique to quantitatively estimate blood oxygenation in cerebral veins. Using spin labeling principle, the signals from static tissue can be subtracted out and, therefore, the isolation of pure blood signal can be achieved. As a result, unlike previous studies (6,12), the spatial resolution of this technique is not restricted by the vessel caliber or by the requirement to fit the entire voxel into the lumen of cerebral veins. Our initial testings on healthy volunteers have demonstrated that this technique can estimate venous oxygenation robustly with an estimation error of 1–2%. On the other hand, consistent with previous reports using invasive methods (2,3), large variations (SD 6.3%) across subjects are observed. This technique is also tested with hypercapnia, a challenge known to increase venous oxygenation, and caffeine ingestion, a challenge known to decrease venous oxygenation, and the observed responses are in agreement with expected vasoactive effects.

We found that the curving fitting of the TRUST MRI data yields robust (e.g. Fig. 3b) and reproducible (e.g. Fig. 4) results. The high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) obtained in the present study is partly because the difference signal in TRUST MRI is about 80±7% of the control signal intensity, unlike in ASL where the difference signal is typically only 0.5–2% of the control signal (13). The high intrinsic signal also affords us to use a small number of averages, four in this study. A second reason for the high SNR is that the voxel size is relatively large. A low spatial resolution of 3.75×3.75×5 mm3 is used for TRUST MRI, as the effect of CSF partial volume is minimized by the control/label subtraction. TRUST MRI with higher resolution (128×128 matrix) has also been tested, and it was found that the fitted T2 values were similar to low-resolution results but the standard error as estimated from goodness-of-fit calculation was greater. In the present study, the TRUST scan contained 4 averages (i.e. 4 pairs of label and control) and used 4 different T2-weightings. A reduction of these values would be able to shorten the scan duration, at the cost of measurement accuracy.

Motion effect and its assessment is an important issue for a fitting-based technique like TRUST MRI. In our data analysis, we used 2D motion correction program (with SPM) to minimize the motion effect. Evaluation of the results with and without using motion correction showed that the results were similar (65.8±11.8ms without motion correction and 66.6±12.0ms with motion correction, n=8), both in terms of the values and the standard errors. This suggests that the (2D) motion correction (suitable for single slice images) only provides marginal improvement. On the other hand, motion would cause imperfect subtraction of the static signals, which will result in poor fitting and larger standard errors. Thus the fitting error can be used as an indicator of the motion effect and also be used as a criterion to accept/reject a dataset. Indeed, in a test in which the subject was instructed to intermittently stretch the legs and arms during the scan (simulating the situation for a not-so-cooperative patient), the standard error for Yv was found to be 3.2%, compared to a standard error of 0.9% when the subject stayed still. In general, using the protocol proposed in this study, we found the standard error was relatively small (1.0±0.3% for Yv). Only one subject in our dataset (out of 39) had an error greater than 3%. Therefore, using a threshold of 3% as the acceptable accuracy, the majority of the subjects will yield usable data.

It should be noted that, even though the TRUST results showed relatively high accuracy and reproducibility, the measurements in the present study have only focused on the sagittal sinus. The measurements in smaller veins will likely show greater estimation errors due to lower blood signals. Therefore, in order to apply TRUST MRI to study regional Yv in focal pathologic areas (e.g. in ischemia regions), further technical development is needed to assess the accuracy. In addition, a venography, using sequences such as susceptibility-weighted-imaging (SWI) (30), is needed for visualizing the small vein trajectory and for optimal positioning of the labeling/imaging slices. Under resting conditions, however, the venous oxygenation in the entire brain is relatively homogeneous, at least for healthy subjects (5,7,31). Therefore the measurement in large veins still provides a good indication of physiologic state of the individual, especially given the large variations across subjects.

In order to convert the blood T2 into venous oxygenation, a calibration curve is needed. The theory for such a relationship is well established (32–34), and experimental results are also available for various field strengths in literature (16). The calibration curve used in this study was obtained from in vitro measurement of bovine blood with a multi-echo CPMG sequence (similar to Silvennoinen et al (16)) and, to our knowledge, is the closest data available to our experiments (3T, τCPMG=10ms, 37°C). Another confounding factor is that hematocrit may influence the curve, which may partly explain the slightly different T2 values between males and females observed in this study. This can be accounted for by using a 3D plot, with both oxygenation and hematocrit as variables. The hematocrit can be determined using blood sampling or a noninvasive method.

The TR-dependence data showed that the blood T2 is under-estimated at short TR (e.g. TR<6s). We speculate the reason is that, at short TR, the spins in the labeling slab are not at equilibrium, due to the T2-preparation pulses in the previous TR-cycle which affected both the blood and the tissue spins. Thus the labeled venous spins, which came from tissue, are not fully inverted, eventually reducing the measured blood signal after the control/label subtraction. Such an attenuation effect is proportional to the number of T2-prep pulses in the previous TR. As such, the signals in the long eTE scans are more attenuated than those in the short eTE, resulting in an under-estimation of the blood T2. A possible approach to reduce such effects is to add a post-saturation pulse after the image acquisition to “reset” the magnetizations, which is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Despite of the lack of spatial localization, global cerebral venous oxygenation may also be useful in certain clinical or biological applications. In particular, in combination with a CBF measurements such as phase-contrast MRI or arterial-spin-labeling, one can estimate the whole brain cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) by the Fick principle (1): CMRO2 =CBF ·(Ya −Yv) ·Ca, in which Ya is the arterial oxygenation and can be obtained non-invasively with pulse oximetry, and Ca is the amount of oxygen molecules that a unit volume of blood can carry. The situations that will most likely benefit from whole-brain CMRO2 measurement are the ones that might have global CMRO2 changes such as aging, sleep, effect of exercise on brain metabolism as well as global alterations such as hypertension, diabetes, and systemic physiologic challenges.

Conclusion

This work shows that TRUST MRI can estimate baseline blood oxygenation in human brain non-invasively and can quantify changes in oxygenation due to physiologic challenges. For large vessel oxygenation measurement, the results show high reproducibility and accuracy, and may be a useful indicator of global metabolic state.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Peter van Zijl of Johns Hopkins University for providing the in vitro blood T2 calibration plot.

Grant sponsors: Texas Instruments Foundation, NIH R21 NS054916 and NIH R01 NS039135

References

- 1.Kety SS, Schmidt CF. The Effects of Altered Arterial Tensions of Carbon Dioxide and Oxygen on Cerebral Blood Flow and Cerebral Oxygen Consumption of Normal Young Men. J Clin Invest. 1948;27:484–492. doi: 10.1172/JCI101995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagdyman N, Fleck T, Schubert S, Ewert P, Peters B, Lange PE, Abdul-Khaliq H. Comparison between cerebral tissue oxygenation index measured by near-infrared spectroscopy and venous jugular bulb saturation in children. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:846–850. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coles JP, Minhas PS, Fryer TD, Smielewski P, Aigbirihio F, Donovan T, Downey SP, Williams G, Chatfield D, Matthews JC, Gupta AK, Carpenter TA, Clark JC, Pickard JD, Menon DK. Effect of hyperventilation on cerebral blood flow in traumatic head injury: clinical relevance and monitoring correlates. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1950–1959. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haacke EM, Lai S, Reichenbach JR, Kuppusamy K, Hoogenraad FG, Takeichi H, Lin W. In vivo measurement of blood oxygen saturation using magnetic resonance imaging: a direct validation of the blood oxygen level dependent concept in functional brain imaging. Human Brain Mapping. 1997;5:341–346. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1997)5:5<341::AID-HBM2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox PT, Raichle ME, Mintun MA, Dence C. Nonoxidative glucose consumption during focal physiologic neural activity. Science. 1988;241:462–464. doi: 10.1126/science.3260686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golay X, Silvennoinen MJ, Zhou J, Clingman CS, Kauppinen RA, Pekar JJ, van Zijl PC. Measurement of tissue oxygen extraction ratios from venous blood T(2): increased precision and validation of principle. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:282–291. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An H, Lin W. Impact of intravascular signal on quantitative measures of cerebral oxygen extraction and blood volume under normo- and hypercapnic conditions using an asymmetric spin echo approach. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:708–716. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez-Seara MA, Techawiboonwong A, Detre JA, Wehrli FW. MR susceptometry for measuring global brain oxygen extraction. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:967–973. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He X, Yablonskiy DA. Quantitative BOLD: mapping of human cerebral deoxygenated blood volume and oxygen extraction fraction: default state. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:115–126. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoge RD, Atkinson J, Gill B, Crelier GR, Marrett S, Pike GB. Linear coupling between cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in activated human cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9403–9408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright GA, Hu BS, Macovski A. 1991 I.I. Rabi Award. Estimating oxygen saturation of blood in vivo with MR imaging at 1.5 T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1991;1:275–283. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880010303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oja JM, Gillen JS, Kauppinen RA, Kraut M, van Zijl PC. Determination of oxygen extraction ratios by magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1289–1295. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199912000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Detre JA, Alsop DC. Perfusion magnetic resonance imaging with continuous arterial spin labeling: methods and clinical applications in the central nervous system. Eur J Radiol. 1999;30:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(99)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelman RR, Siewert B, Darby DG, Thangaraj V, Nobre AC, Mesulam MM, Warach S. Qualitative mapping of cerebral blood flow and functional localization with echo-planar MR imaging and signal targeting with alternating radio frequency. Radiology. 1994;192:513–520. doi: 10.1148/radiology.192.2.8029425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SG. Quantification of relative cerebral blood flow change by flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery (FAIR) technique: application to functional mapping. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:293–301. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silvennoinen MJ, Clingman CS, Golay X, Kauppinen RA, van Zijl PC. Comparison of the dependence of blood R2 and R2* on oxygen saturation at 1.5 and 4.7 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:47–60. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao JM, Clingman CS, Narvainen MJ, Kauppinen RA, van Zijl PC. Oxygenation and hematocrit dependence of transverse relaxation rates of blood at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:592–597. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong EC, Buxton RB, Frank LR. Implementation of quantitative perfusion imaging techniques for functional brain mapping using pulsed arterial spin labeling. NMR Biomed. 1997;10:237–249. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199706/08)10:4/5<237::aid-nbm475>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Botnar RM, Stuber M, Danias PG, Kissinger KV, Manning WJ. Improved coronary artery definition with T2-weighted, free-breathing, three-dimensional coronary MRA. Circulation. 1999;99:3139–3148. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brittain JH, Hu BS, Wright GA, Meyer CH, Macovski A, Nishimura DG. Coronary angiography with magnetization-prepared T2 contrast. Magn Reson Med. 1995;33:689–696. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buxton RB, Frank LR, Wong EC, Siewert B, Warach S, Edelman RR. A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40:383–396. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu H, Clingman C, Golay X, van Zijl PC. Determining the longitudinal relaxation time (T1) of blood at 3.0 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:679–682. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu H, Nagae-Poetscher LM, Golay X, Lin D, Pomper M, van Zijl PC. Routine clinical brain MRI sequences for use at 3.0 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:13–22. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu H, van Zijl PC. Experimental measurement of extravascular parenchymal BOLD effects and tissue oxygen extraction fractions using multi-echo VASO fMRI at 1.5 and 3.0 T. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:808–816. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caronia C, Greissman A, Nimkoff L, Silver P, Quinn C, Sagy M. Increased artificial deadspace ventilation is a safe and reliable method for deliberate hypercapnia. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1175–1178. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199707000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulderink TA, Gitelman DR, Mesulam MM, Parrish TB. On the use of caffeine as a contrast booster for BOLD fMRI studies. Neuroimage. 2002;15:37–44. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu TT, Behzadi Y, Restom K, Uludag K, Lu K, Buracas GT, Dubowitz DJ, Buxton RB. Caffeine alters the temporal dynamics of the visual BOLD response. Neuroimage. 2004;23:1402–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibrahim MA, Emerson JF, Cotman CW. Magnetic resonance imaging relaxation times and gadolinium-DTPA relaxivity values in human cerebrospinal fluid. Invest Radiol. 1998;33:153–162. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199803000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koenig SH, Brown RD., 3rd Relaxometry of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Magn Reson Annu. 1987:263–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haacke EM, Xu Y, Cheng YC, Reichenbach JR. Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:612–618. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox PT, Raichle ME. Focal physiological uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism during somatosensory stimulation in human subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:1140–1144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.4.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryant RG, Marill K, Blackmore C, Francis C. Magnetic relaxation in blood and blood clots. Magn Reson Med. 1990;13:133–144. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910130112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barth M, Moser E. Proton NMR relaxation times of human blood samples at 1.5 T and implications for functional. MRI Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 1997;43:783–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks RA, Di Chiro G. Magnetic resonance imaging of stationary blood: a review. Med Phys. 1987;14:903–913. doi: 10.1118/1.595994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]