Abstract

A new strategy for the synthesis of the Strychnos alkaloid (±)-strychnine has been developed and is based on an intramolecular [4+2]-cycloaddition/rearrangement cascade of an indolyl substituted amidofuran. The critical D-ring was assembled by an intramolecular palladium catalyzed enolate-driven cross-coupling of an N-tethered vinyl iodide.

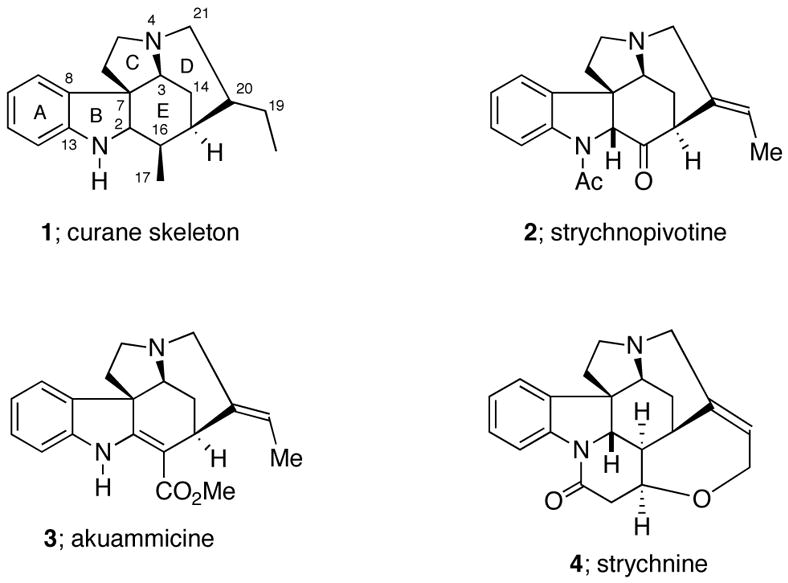

Strychnos alkaloids belonging to the curane type constitute an important group of architecturally complex and widely distributed monoterpenoid indole alkaloids.1,2 The curane family is characterized by the presence of a pentacyclic 3,5-ethanopyrrolo[2,3-d]carbazole framework (i.e., 1) bearing a two-carbon appendage at C-20 and an oxidized one-carbon substituent (C-17) at the C-16 position (Figure 1).3 The synthesis of various members of the Strychnos family has been an area of interest ever since the structural elucidation of strychnine (4), the most famous of this group of alkaloids, by Robinson in 1946.4 Strychnine was first isolated in 1818 from the Indian poison nut5 (Strychnos nux vomica) and possesses highly toxic properties as a result of its interaction with the glycine receptor site thereby blocking the flux of chloride ions and disruption of nerve-cell signaling.6 Its complex heptacyclic structure, containing 24 skeletal atoms and six contiguous stereogenic centers, has fascinated organic chemists for the past sixty years. Nearly 40 years after Woodward’s pioneering achievement of strychnine7, a number of other research groups have reported on its synthesis.8

Figure 1.

Some representative Strychnos alkaloids

Efficient approaches toward the Strychnos pentacyclic framework would allow not only the synthesis of other members of this family of natural products (i.e., strychnopivotine (2) and akuammicine (3)), but also related non-natural products possessing biological activity. Along these lines, we have recently become involved in the development and optimization of a new approach for the construction of the pentacyclic framework of the Strychnos system. In this communication, we report a concise stereocontrolled total synthesis of (±)-strychnine (4) wherein an efficient [4+2]-cycloaddition/rearrangement method previously developed in our laboratories plays a crucial role.9

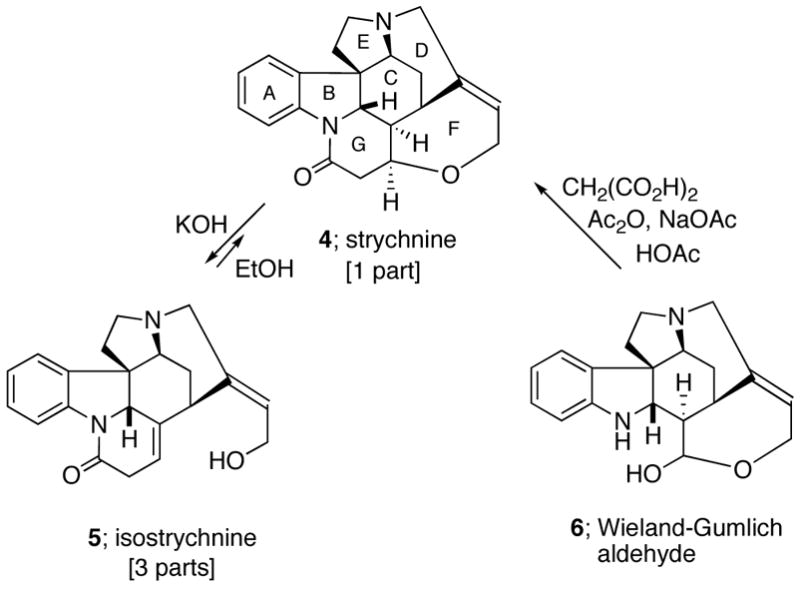

In Rawal and Iwasa’s elegant synthesis of (±)-strychnine,8e an ingenious palladium-catalyzed intramolecular Heck reaction was used as the key step for the creation of the D-ring. As in Woodward’s original approach,7 isostrychnine (5) was the final critical intermediate used in this synthesis. Its Prelog-Taylor cyclization to strychnine10 (Scheme 1), however, suffers from an unfavorable 3:1-equilibration ratio of these two compounds. From this perspective, the alternative biomimetic route to strychnine involving condensation of the Wieland-Gumlich aldehyde (6) with an acetate equivalent for the formation of the G ring seemed to us to be the more attractive approach,11 as it avoids the unfavorable equilibration ratio. As illustrated in Scheme 2, our retrosynthetic analysis of strychnine (4) relies upon the efficient construction of the tetracyclic sub-structure 8, containing the ABCE rings of 4, by an intramolecular [4+2]-cycloaddition/rearrangement cascade of 2-amido-furan 7. The synthetic plan also involves closure of the D-ring by a palladium-catalyzed intramolecular coupling of an amido tethered vinyl iodide with a keto enolate (i.e. 9 → 10).12,13

Scheme 1.

Scheme 2.

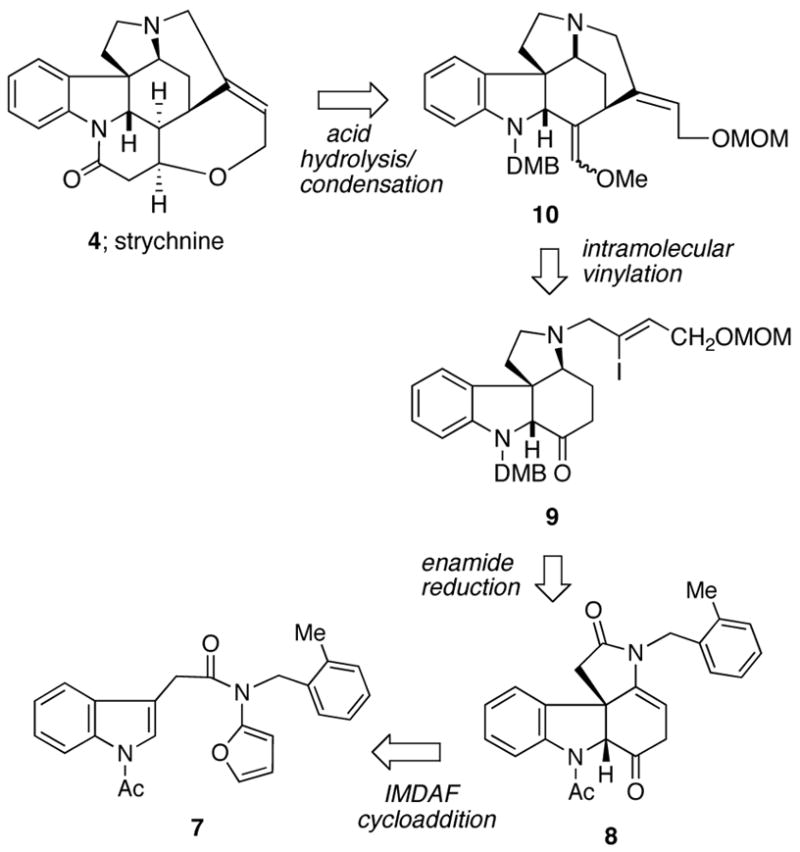

Some years ago, we commenced a program of research based on the intramolecular [4+2]-cycloaddition/rearrangement cascade of 2-amidofurans as a strategy for the synthesis of different classes of alkaloids.14 Intramolecular cycloaddition reactions often benefit from higher reactivity and greater control of stereoselectivity relative to their intermolecular counterparts. Specifically, connecting the two π-fragments via a “tether” generally facilitates the rate of the [4+2]-cycloaddition reaction. Our earlier experience with this domino sequence prompted us to apply the cascade approach toward (±)-strychnine. With this in mind, we prepared furanyl indole 7 by acylation of the mixed anhydride of 2-(1-acetyl-1H-indol-3-yl)acetic acid15 with the N-lithiate anion of tert-butyl furan-2-ylcarbamate followed by Boc deprotection16 with Mg(ClO4)2 and subsequent N-alkylation using 1-(bromomethyl)-2-methylbenzene in 55% overall yield for the 3-step procedure. We suspect that the presence of the large o-methylbenzyl group on the amido nitrogen atom causes the reactive s-trans rotamer to be more highly populated and probably helps promote the [4+2]-intramolecular cycloaddition. Indeed, the cycloaddition/rearrangement cascade of 7 was remarkably efficient given that two heteroaromatic systems are compromised in the reaction. Thus, heating a sample of 7 at 150 °C (toluene) in a microwave reactor for 30 min in the presence of catalytic MgI2 afforded the desired aza-tetracycle 8 in 95% yield (Scheme 3). This reaction cascade can be rationalized by a nitrogen-assisted ring opening of the initially formed cycloadduct 11 to produce N-acyliminium ion 12. A subsequent deprotonation followed by ketonization of the resulting enol accounts for the formation of 8.

Scheme 3.

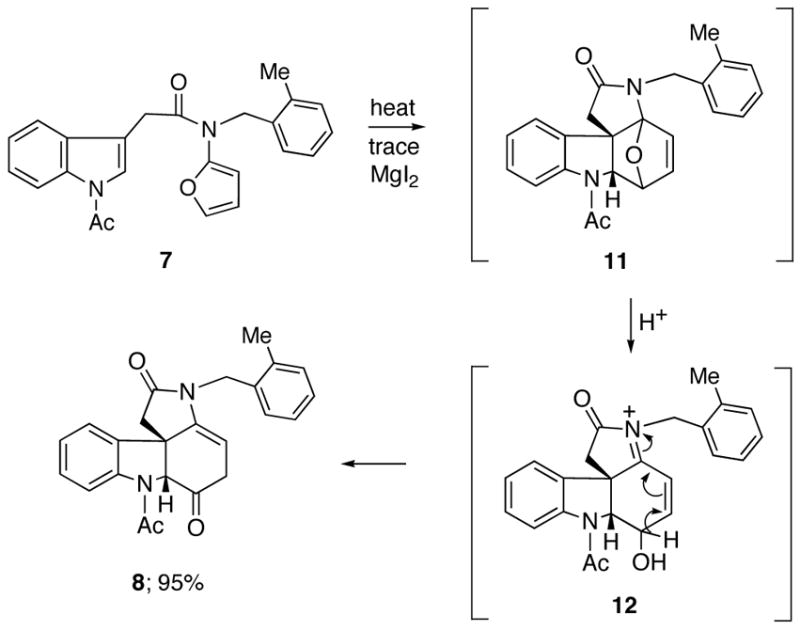

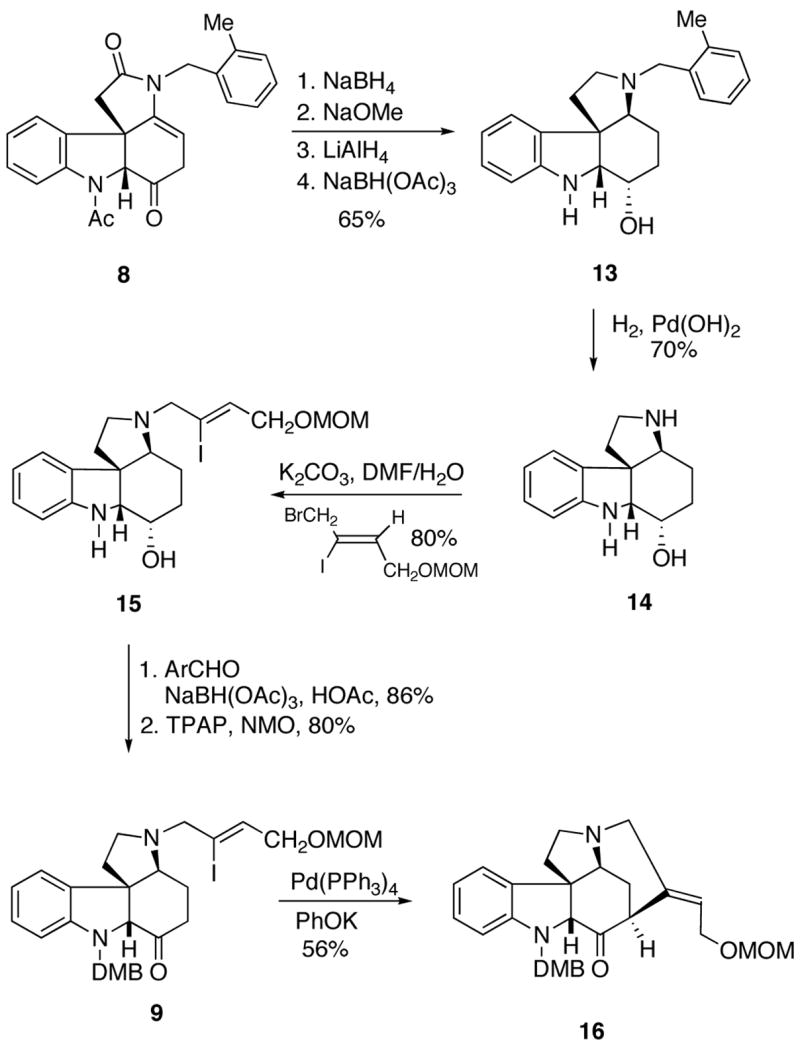

Our synthesis of the more advanced tetracycle 9 required for eventual D-ring cyclization of strychnine began by stereoselective reduction of the keto group of 8 with NaBH4 followed by N-deacetylation using NaOMe (Scheme 4). The γ-lactam carbonyl group was then reduced with LiAlH4 and the resulting enamine was further reduced using NaBH(OAc)3 to give alcohol 13 as the major diastereomer in 65% yield over the four-step sequence.17 Removal of the o-methylbenzyl group by catalytic hydrogenation furnished 14 in 70% isolated yield. This was followed by N-alkylation with Z-1-bromo-2-iodo-4-(methoxymethoxy)-but-2-ene18 to give alcohol 15 in 80% yield. Condensation of the indoline nitrogen present in 15 with 2,4-dimethoxybenzaldehyde in the presence of NaBH(OAc)319 afforded the N-protected 2,4-dimethoxy-benzylamine (DMB) in 86% yield.20 Oxidation of the resulting secondary alcohol to the corresponding ketone 9 occurred smoothly in 80% yield using tetrapropyl-ammonium perruthenate (TPAP).21 The stage was now set for the completion of the synthesis. The critical D-ring of strychnine was constructed by a palladium-catalyzed intramolecular coupling of the amino-tethered vinyl iodide with the keto enolate derived from 9. The key palladium-catalyzed cyclization was carried out on a sample of 9 using Pd(PPh3)4 and PhOK. Gratifyingly, the reaction proceeded smoothly to furnish aza-pentacycle 16 in 56% unoptimized yield.22

Scheme 4.

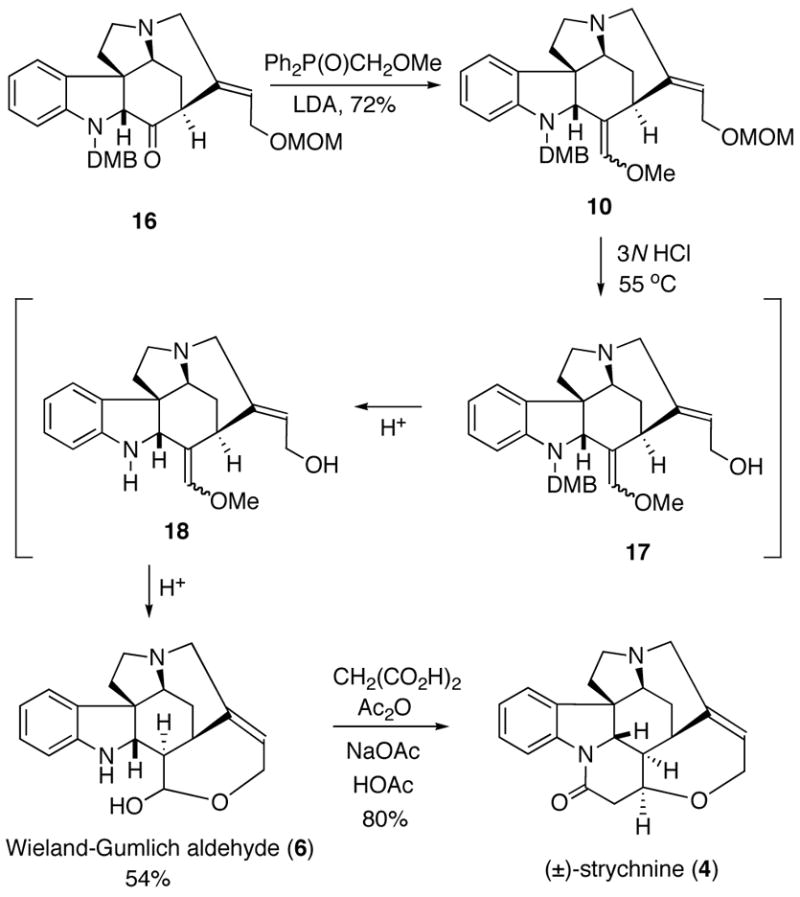

Our initial attempts to convert the keto group of 16 into the corresponding enol ether 10 using methoxymethylene-triphenylphosphorane (MeOCH=PPh3) were unsuccessful, probably as a consequence of steric congestion about the ketone. Consequently, we turned our attention to the phosphine oxide reagent MeOCH2P(O)Ph2 whose anion is sterically less demanding and more nucleophilic compared to the phosphorane MeOCH=PPh3.23,24 Thus, treatment of MeOCH2P(O)Ph2 with LDA in THF gave the lithio anion which reacted smoothly with ketone 16 at 0 °C to provide 10 as a single diastereomer in 72% isolated yield (Scheme 5). The last major hurdle involved an acid promoted deprotection/hydrolysis of 10 into the Wieland-Gumlich aldehyde (6). The hydrolysis was satisfactorily accomplished by the treatment of 10 with 3N HCl in THF at 55 °C for 10 h which gave 6 in 54% yield. By using shorter reaction times and following the reaction by NMR spectroscopy, we found that the initially formed primary alcohol 17 undergoes a subsequent deprotection of the DMB group to furnish enol ether 18. Further stirring of 18 under the acidic conditions eventually furnished the Wieland-Gumlich aldehyde (6). Although the conversion of 6 into strychnine had been reported by Robinson in 1953,11 we decided to reproduce the described protocol for the sake of a complete total synthesis. Thus, the final biomimetic condensation of 6 with malonic acid, acetic anhydride, sodium acetate, and acetic acid provided (±)-strychnine (4) in 80% yield and with a 4.4% overall yield for the 13-step reaction sequence starting from furanyl indole 7.

Scheme 5.

In summary, a concise synthesis of the Strychnos alkaloid (±)-strychnine is reported. A central step in the synthesis consists of an intramolecular [4+2]-cycloaddition/rearrangement cascade of an indolyl substituted amidofuran which delivers an aza-tetracyclic sub-structure containing the ABCE-rings of the natural product. Closure of the remaining D-ring was carried out from the aza-tetracyclic intermediate by an intramolecular palladium catalyzed enolate-driven cross-coupling between the N-tethered vinyl iodide and the keto group. The short sequence used to synthesize (±)-strychnine should also provide rapid entry into other Strychnos alkaloid natural products and is currently under active investigation in our laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information Available: Spectroscopic data and experimental details for the preparation of all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

Acknowledgments

Dedicated to my colleague and friend David Goldsmith on the occasion of his 75th birthday. We appreciate the financial support provided by the National Institutes of Health (GM 059384) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-0450779). We wish to thank Professor Larry Overman (UC Irvine) for providing a proton NMR spectrum of the Wieland-Gumlich aldehyde (6) for comparison purposes.

References

- 1.For leading reviews of Strychnos alkaloids, see: Bosch J, Bonjoch J, Amat M. The Alkaloids. 1996;48:75. and references cited therein.Bonjoch J, Solé D. Chem Rev. 2000;100:3455. doi: 10.1021/cr9902547.

- 2.Creasey WA. In: The Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids. Saxton JE, editor. Mterscience; New York: 1983. p. 800. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The biogenetic numbering is used for pentacyclic structures such as 1, see: Le Men J, Taylor WI. Experientia. 1965;21:508. doi: 10.1007/BF02138961.

- 4.(a) Robinson R. Experientia. 1946;2:28. doi: 10.1007/BF02154708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Holmes HL, Openshaw HT, Robinson R. J Chem Soc. 1946:908. doi: 10.1039/jr9460000908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Openshaw HT, Robinson R. Nature. 1946;157:438. doi: 10.1038/157438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelletier PJ, Caventou JB. Ann Chim Phys. 1818;8:323. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Aprison MH. In: Glycine Neurotransmission. Otterson OP, Strom-Mathisen J, editors. Wiley; New York: 1990. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]; (b) Grenningloh G, Rienitz A, Schmitt B, Methfessel C, Zensen M, Beyreuther K, Gundelfinger ED, Betz H. Nature. 1987;328:215. doi: 10.1038/328215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kleckner NW, Dingledine R. Science. 1988;241:835. doi: 10.1126/science.2841759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodward RB, Cava MP, Ollis WD, Hunger A, Daeniker HU, Schenker K. J Am Chem Soc. 1954;76:4749. [Google Scholar]; Woodward RB, Cava MP, Ollis WD, Hunger A, Daeniker HU, Schenker K. Tetrahedron. 1963;19:247. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Magnus P, Giles M, Bonnert R, Kim CS, McQuire L, Merritt A, Vicker N. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:4403. [Google Scholar]; Magnus P, Giles M, Bonnert R, Johnson G, McQuire L, Deluca M, Merritt A, Kim CS, Vicker N. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:8116. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stork G. Presented at the Ischia Advanced School of Organic Chemistry; Ischia Porto, Italy. September 21, 1992. [Google Scholar]; (c) Knight SD, Overman LE, Pairaudeau G. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:9293. [Google Scholar]; Knight SD, Overman LE, Pairaudeau G. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:5776. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kuehne ME, Xu F. J Org Chem. 1993;58:7490. [Google Scholar]; Kuehne ME, Xu F. J Org Chem. 1998;63:9427. [Google Scholar]; (e) Rawal VH, Iwasa S. J Org Chem. 1994;59:2685. [Google Scholar]; (f) Solé D, Bonjoch J, García-Rubio S, Peidró E, Bosch J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1999;38:395. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990201)38:3<395::AID-ANIE395>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Solé D, Bonjoch J, García-Rubio S, Peidró E, Bosch J. Chem-Eur J. 2000;6:655. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(20000218)6:4<655::aid-chem655>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Eichberg MJ, Dorta RL, Lamottke K, Vollhardt KPC. Org Lett. 2000;2:2479. doi: 10.1021/ol006131m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Eichberg MJ, Dorta RL, Grotjahn DB, Lamottke K, Schmidt M, Vollhardt KPC. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9324. doi: 10.1021/ja016333t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Ito M, Clark CW, Mortimore M, Goh JB, Martin SF. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8003. doi: 10.1021/ja010935v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Nakanishi M, Mori M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:1934. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020603)41:11<1934::aid-anie1934>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mori M, Nakanishi M, Kajishima D, Sato Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9801. doi: 10.1021/ja029382u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Bodwell GJ, Li J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:3261. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3261::AID-ANIE3261>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Ohshima T, Xu Y, Takita R, Shimizu S, Zhong D, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14546. doi: 10.1021/ja028457r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ohshima T, Xu Y, Takita R, Shibasaki M. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:9569. [Google Scholar]; (l) Kaburagi Y, Tokuyama H, Fukuyama T. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10246. doi: 10.1021/ja046407b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Wang Q, Padwa A. Org Lett. 2004;6:2189. doi: 10.1021/ol049348f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Padwa A, Ginn JD. J Org Chem. 2005;70:5197. doi: 10.1021/jo050515e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Padwa A, Bur SK, Zhang H. J Org Chem. 2005;70:6833. doi: 10.1021/jo0508797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhang H, Padwa A. Org Lett. 2006;8:247. doi: 10.1021/ol052524f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prelog V, Battegay J, Taylor WI. Helv Chim Acta. 1948;31:2244. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19480310750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anet FAL, Robinson R. Chem Ind. 1953:245. See also references 8a and 8c. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Solé D, Peidró E, Bonjoch J. Org Lett. 2000;2:2225. doi: 10.1021/ol005973i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Solé D, Diaba J, Bonjoch J. J Org Chem. 2003;68:5746. doi: 10.1021/jo034299q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bonjoch J, Diaba F, Puigbó G, Peidró E, Solé D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:8387. [Google Scholar]; (d) Solé D, Urbaneja X, Bonjoch J. Adv Synth Catal. 2004;346:1646. [Google Scholar]; (e) Solé D, Urbaneja X, Bonjoch J. Org Lett. 2005;7:5461. doi: 10.1021/ol052230u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.For some other examples of intramolecular Pd-catalyzed vinylations, see: Piers E, Oballa RM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5857.Yu J, Wang T, Liu X, Deschamps J, Flippen-Anderson J, Liao X, Cook JM. J Org Chem. 2003;68:7565. doi: 10.1021/jo030006h.

- 14.(a) Padwa A, Brodney MA, Dimitroff M. J Org Chem. 1998;63:5304. doi: 10.1021/jo010020z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bur SK, Lynch SM, Padwa A. Org Lett. 2002;4:473. doi: 10.1021/ol016804g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ginn JD, Padwa A. Org Lett. 2002;4:1515. doi: 10.1021/ol025746b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padwa A, Brodney MA, Lynch SM, Rashatasakhon P, Wang Q, Zhang H. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3735. doi: 10.1021/jo049808i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Young FG, Frostick FC, Sanderson JJ, Hauser CR. J Am Chem Soc. 1950;72:3635. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mao C-L, Frostick FC, Man EH, Manyik RM, Wells RL, Hauser CR. J Org Chem. 1969;34:1425. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Attempts to introduce the vinyl iodide moiety earlier in the synthesis were unsuccessful due to the competitive loss of the iodo group during the reduction step.

- 18.The synthesis of the required allylic bromide is described in the supplemental section.

- 19.Abdel-Magid AF, Carson KG, Harris BD, Maryanoff CA, Shah RD. J Org Chem. 1996;61:3849. doi: 10.1021/jo960057x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The DMP group was selected as it was readily removed under the acidic conditions employed in the hydrolysis of 10 to the Wieland-Gumlich aldehyde (6) (see Scheme 5).

- 21.Ley SV, Norman J, Griffith WP, Marsden SP. Synthesis. 1994:639. [Google Scholar]

- 22.A similar approach was successfully employed in a synthesis of strychnopivotine (2) and this will be described at a later date.

- 23.Earnshaw C, Wallis CJ, Warren S. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1979:3099. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel DV, Schmidt RJ, Gordon EM. J Org Chem. 1992;57:7143. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Available: Spectroscopic data and experimental details for the preparation of all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org