Abstract

Echinocandins target fungal β-1,3 glucan synthesis and are used clinically to treat invasive aspergillosis. Although echinocandins do not completely inhibit in vitro growth of Aspergillus fumigatus, they do induce morphological changes in fungal hyphae. Because β-1,3 glucans activate host antifungal pathways via the Dectin-1 receptor, we investigated the effect of echinocandins on inflammatory responses to A. fumigatus. Caspofungin- or micafungin-treated conidia and germlings induced less secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and CXCL2 by macrophages than did their untreated counterparts. Diminished secretion of TNF and CXCL2 correlated with diminished β-glucan exposure on echinocandin-treated germ tubes. In contrast to treated conidia and germlings, echinocandin-treated hyphae stimulated increased release of TNF and CXCL2 by macrophages and demonstrated intense staining with a β-glucan-specific antibody, particularly at hyphal tips. Our experiments demonstrate that echinocandin-induced morphological changes in A. fumigatus hyphae are accompanied by increased β-glucan exposure, with consequent increases in Dectin-1-mediated inflammatory responses by macrophages.

In 2001, the echinocandin caspofungin was licensed in the United States as a second-line agent for the treatment of invasive aspergillosis (IA), which is a common cause of infection-associated morbidity and mortality among immunocompromised patients [1-3]. IA begins with the inhalation of airborne spores (i.e., conidia) that escape weakened pulmonary host defenses and germinate into tissue-invasive hyphae [4, 5]. Caspofungin is a noncompetitive inhibitor of β-1,3 glucan synthase, an essential enzyme located on the growing filaments (i.e., hyphae) of Aspergillus fumigatus [6], the most common etiologic agent of IA.

Although caspofungin has been found to be effective in animal models of IA [7-10], it does not fully inhibit growth of A. fumigatus, even at high concentrations [11, 12]. Echinocandins reduce bulk β-1,3 glucan levels [13] and induce profound morphological changes that include the formation of swollen germ tubes; short, broad-based hyphae with aberrant branching; and distended, balloon-type cells [11]. The minimum drug concentration associated with these changes is referred to as the “minimum effective concentration” (MEC).

In contrast, caspofungin induces complete growth inhibition and cell lysis of the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans [12]. At sub-MIC concentrations, caspofungin increases β-glucan exposure on C. albicans, and drug-treated yeast cells trigger enhanced macrophage inflammatory responses [14]. In the case of A. fumigatus, caspofungin appears to induce membrane depolarization in a subset of cells located at the tips and branch points of the growing mycelium [15], a process that is sufficient to stunt but not arrest filamentous growth.

Not only is β-1,3 glucan an obligate fungal cell wall constituent, it represents a target of the innate immune system. The mammalian receptor Dectin-1 [16, 17] binds to β-1,3-glucan from Pneumocystis carinii [18], C. albicans [19], A. fumigatus [20-22], and Coccidioides posadasii [23]. It also triggers fungicidal responses that include phagocytosis, release of inflammatory mediators, and generation of reactive oxygen intermediates [17].

Although echinocandins increase β-glucan exposure on the surface of C. albicans, whether this change occurs in such clinically important molds as A. fumigatus is not known. Therefore, we treated A. fumigatus spores with echinocandins in vitro and measured surface β-glucan exposure and macrophage inflammatory responses. TNF and CXCL2, a neutrophil chemoattractant, were chosen as a readout for inflammatory responses, because both have established roles in host defense against A. fumigatus [24-27]. During the early stages of conidial swelling and germ tube formation, drug-treated cells elicited weaker inflammatory responses than did control cells. In contrast, drug-treated hyphae induced stronger inflammatory responses than did control cells. In all cases, the magnitude of the inflammatory response reflected changes in surface β-glucan exposure. Our findings suggest that echinocandins, by increasing β-glucan exposure on the surface of invading A. fumigatus hyphae, may enhance antifungal inflammatory responses to hyphae, independent of direct growth inhibition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

Chemical and cell culture reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Gibco, respectively. Caspofungin (Merck) and micafungin (Astellas) in powder form were obtained from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center pharmacy, dissolved in sterile PBS at 5 mg/mL, and stored at -80°C. The anti-Dectin-1 antibody 2A11 and an IgG isotype control antibody were purchased from AbD Serotec. Monoclonal antibody (MAb) 744 has been described elsewhere [20], and an Alexa Fluor 594-linked anti-mouse IgM antibody was obtained from Invitrogen.

Fungal growth and culture

C. albicans strain SC5314 was grown in yeast extract peptone dextrose overnight at 25°C. Yeast cells were diluted 1:1000 in fresh medium ± 5 ng/mL caspofungin, shaken overnight at 25°C, washed 3 times in PBS, killed by UV irradiation from a Stratalinker UV Crosslinker 1800 (dose, 4 × 105 mJ/cm2), and added to bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMϕs) at a ratio of 10:1. The MIC of caspofungin for these conditions was 10 ng/mL.

A. fumigatus strains Af293 and ATCC 90906 were cultured as described elsewhere [20]. For germination reactions, 5 × 104 conidia were seeded in 96-well culture dishes (Invitrogen) in 0.2 mL of RP-10+ (i.e., RPMI 1640, 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum [FCS], 5 mmol/L HEPES [pH 7.4], 1.1 mmol/L l-glutamine, 0.5 U/mL penicillin, 0.5 μg/mL gentamicin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, and 50 μmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol) containing caspofungin (0-1000 ng/mL) or micafungin (0-1000 ng/mL) and incubated at 37°C for the times indicated. Culture supernatants were aspirated, and fungal cells were inactivated by UV irradiation, as described above.

Cell culture and ELISA

BMMϕs obtained from 8- to 12-week-old C57BL/6 female mice were prepared as described elsewhere [20], harvested after 5 days in culture, adjusted to 7.5 × 105 cells/mL in RP-10+, and added (in a final volume of 0.2 mL) to empty wells or wells containing UV-inactivated fungal cells in 96-well plates.

For experiments with live A. fumigatus conidia, BMMϕs were cultured with 1.5 × 106 conidia in 0.2 mL of RP-10+ with 0-1000 ng/mL caspofungin or micafungin for 18 h at 37°C. For specific experiments, 10 μg/mL anti-Dectin-1 or isotype control antibody was added to BMMϕs 10 min before coculture with fungal cells. For experiments with UV-inactivated fungal cells, the BMMϕ coincubation period was 6 h. Culture supernatants were analyzed using commercially available ELISA kits for the detection of CXCL2 (R & D Systems) and TNF (BD Biosciences) by use of a VersaMax Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices).

Confocal microscopy

A total of 5 × 104 conidia per well was grown on 4-well Lab-Tek glass chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International) in RP-10+ with the indicated drug concentration for 8-24 h at 37°C. Pilot experiments determined that UV inactivation did not alter β-glucan immunoreactivity. Fungal cells were processed for confocal microscopy by use of MAb 744 and Alexa Fluor 594-linked anti-mouse IgM, as described elsewhere [20]. No immunoreactivity was observed in samples stained with a control isotype antibody. The samples were scanned in 0.5- to 1.0-μm intervals (in the z-plane), with the use of an upright Leica TCS SP2 AOBS confocal microscopy system equipped with a 63× Leica HPX PL APO water-immersion objective (numeric aperture 1,2) using the 488-nm and 594-nm laser lines and transmitted light. Composite fluorescence images were assembled from individually scanned optical sections obtained from a 30- to 40-μm interval in the z-plane. For all images displayed, the sensitivity of the recording photomultiplier tube was set in the linear range and was identical for drug-treated and untreated cells.

For image analysis of drug-treated and untreated hyphae, cellular autofluorescence was recorded using the 488-nm laser line to visualize the hyphal area (in cross-section) in optical sections measuring 237.5 μm × 237.5 μm × 1 μm. Autofluorescence and immunofluorescence recordings underwent image analysis in MetaMorph software (version 7.1.1.0; Molecular Devices). Threshold settings were applied uniformly for all paired data sets. A low-pass filter (2 × 2 pixels) was applied to autofluorescence stacks to suppress single-pixel noise, and the area above a set threshold was measured in each optical slice and then summed across all slices within a field of view, to obtain a measure of the total hyphal volume within an image stack.

For image processing of immunofluorescence recordings, no filters were applied, and the integrated fluorescence intensity in the red channel above a set threshold was measured for each optical slice and summed across all slices within the same field of view. To associate β-glucan immunoreactivity with fungal biomass for drug-treated and untreated hyphae (after 24 h of incubation), the total integrated fluorescence intensity in the red channel was divided by the summed threshold area delineated by the autofluorescent signal, resulting in a measurement of β-glucan immunoreactivity per hyphal volume. In a single experiment, 4-5 optical sections, each consisting of ∼30-40 optical slices, were evaluated for each condition.

RESULTS

No direct elicitation by caspofungin of macrophage TNF production

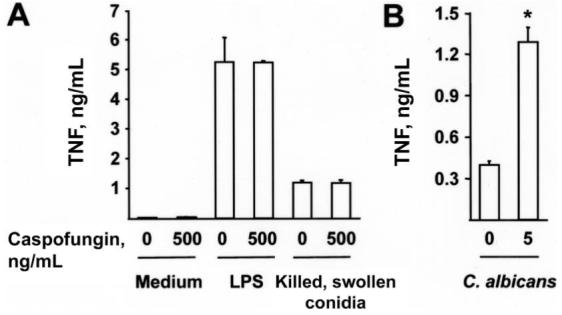

To determine whether caspofungin directly elicits inflammatory responses, the drug was added to BMMϕ cultures. No difference in the secretion of TNF or CXCL2 by BMMϕ was observed in drug-treated or control samples (figure 1A) (not shown), even with concurrent addition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or killed, swollen A. fumigatus conidia. Thus, caspofungin does not trigger secretion of TNF or CXCL2 by BMMϕ at rest or in conjunction with inflammatory stimuli. In contrast, C. albicans yeast cells grown in sub-MIC levels of caspofungin elicited TNF secretion that was ∼4-fold higher than that of control cells (figure 1B), in accordance with results achieved using a different strain [14].

Figure 1.

Caspofungin and a lack of direct inducement of inflammatory responses. A, Secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) by 105 bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMϕs) cultured in RP-10+ (see Materials and Methods for details) with 0 or 500 ng/mL caspofungin. Samples contained 100 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or 5 × 105 heat-killed, swollen Aspergillus fumigatus conidia, as indicated. B, Secretion of TNF by 105 BMMϕs incubated with 106 UV-inactivated Candida albicans yeast cells grown in yeast extract peptone dextrose containing 0 or 5 ng/mL caspofungin. A and B, Bar graphs denote the average TNF concentration (+SD) in 3 wells per condition. One of 3 representative experiments is shown. *P < .05, by 2-tailed t test, compared with control condition (i.e., no drug treatment).

Caspofungin and the diminishment of inflammatory responses to live A. fumigatus conidia

At rest, A. fumigatus conidia trigger minimal inflammatory responses [20]. Conidial swelling represents the first step of germination and is required for macrophages to initiate inflammatory and fungicidal responses [28, 29].

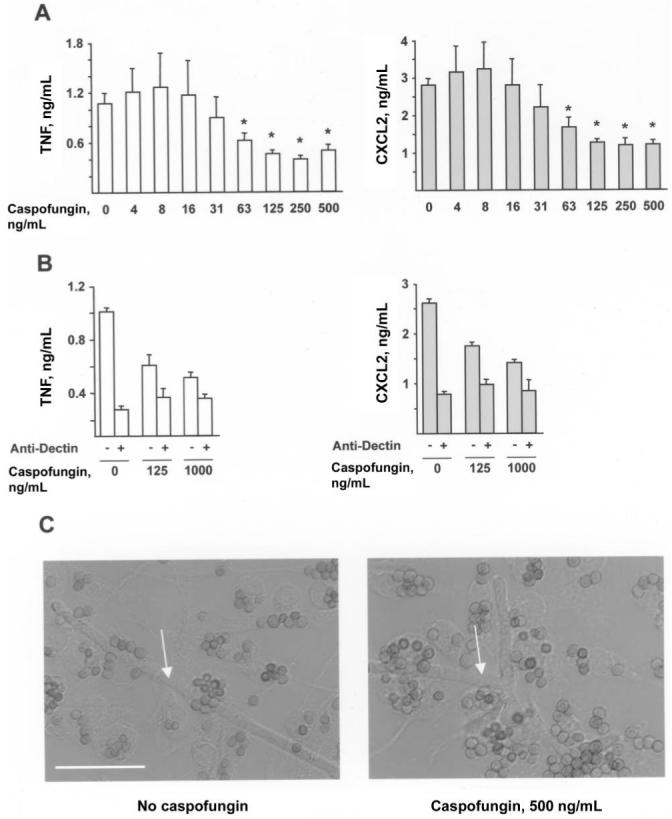

To examine the effect of caspofungin on inflammatory responses to conidia, BMMϕs and conidia (derived from A. fumigatus strain Af293) were incubated for 18 h in the presence of 0-500 ng/mL caspofungin. Caspofungin diminished inflammatory responses in a dose-dependent manner, with a reduction evident at drug concentrations at or above the MEC, which was determined to be 63 ng/mL for the experimental conditions (figure 2A). At a drug concentration of 500 ng/mL, the average percentage (±SD) of TNF and CXCL2 released into the supernatants by BMMϕs was 49% ± 4% (range, 46%-54%; n = 4 experiments) and 55% ± 10% (range, 43%-62%; n = 4 experiments), respectively, compared with the amount released for untreated samples. Similar results were obtained with conidia derived from A. fumigatus strain ATCC 90906 (not shown).

Figure 2.

Caspofungin and reductions in inflammatory responses to conidia. A and B, Secretion of tumor necrosis factor (white bars) or CXCL2 (gray bars) by 1.5 × 105 bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMϕs) incubated for 18 h with 7.5 × 105 Aspergillus fumigatus conidia (A) in RP-10+ (see Materials and Methods for details) with 0 or 500 ng/mL caspofungin or (B) under the same conditions, with the addition of 10 μg/mL anti-Dectin (+) or isotype control antibody (-). Bar graphs denote the average TNF or CXCL2 concentration (+SD) in 3-4 wells per condition. One of 4 (A) or 3 (B) representative experiments is shown. *P < .05, by 2-tailed t test, compared with control condition (i.e., no drug treatment). C, Differential interference contrast image of BMMϕs and conidia after 18 h in RP-10+ with 0 ng/mL (left) or 500 ng/mL (right) caspofungin. Arrows denote hyphae. Scale bar, 20 μm.

To determine whether exposure of conidia to caspofungin diminishes Dectin-1 signaling by macrophages, the effect of antibody-mediated receptor blockade on inflammatory responses to drug-treated and untreated conidia was examined. MAb 2A11 binds to the extracellular portion of Dectin-1 and blocks signal transduction through its intracellular immunoregulatory tyrosine-based activation motif-like motif [30]. Macrophages isolated from Dectin-1-/- mice do not bind MAb 2A11 [31], indicating that the antibody is specific for Dectin-1 and does not bind to other C-type lectins (e.g., dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin or Dectin-2, receptors with different carbohydrate-binding properties implicated in the recognition of fungal cells) [32-34].

In agreement with previous studies [20-22, 31], antibody-blocking experiments demonstrated that Dectin-1 is largely responsible for macrophage production of TNF and CXCL2 in response to conidia (figure 2B). The reduced macrophage inflammatory response observed in association with drug-treated conidia reflects the diminished Dectin-1-associated signaling triggered by these cells.

The conidia-macrophage coincubation assay described above measures inflammatory responses to the earliest stage of conidial germination. In caspofungin-treated and drug-free samples, >99% of conidia associated with macrophages at the conclusion of the incubation period did not form germ tubes (figure 2C). Rare hyphae that escaped macrophage control were observed in all samples (<1% of cells), consistent with the inability of caspofungin to prevent germination (figure 2C, white arrows). In sum, these results suggest that caspofungin reduces the inflammatory responses of BMMϕs to live conidia.

Caspofungin and diminishment of inflammatory responses to A. fumigatus germlings

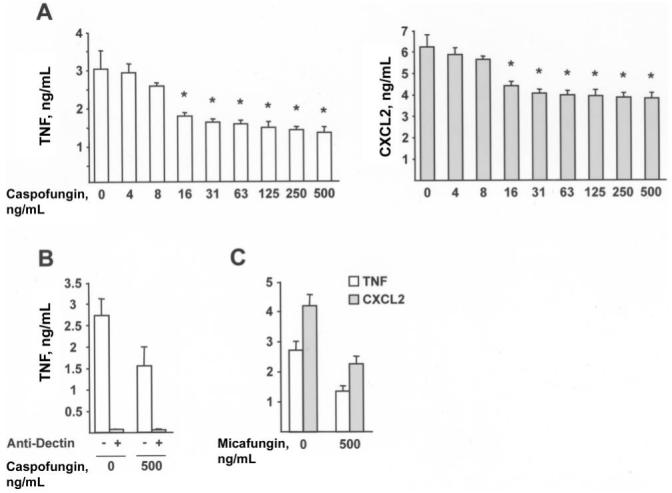

To examine the effect of caspofungin on inflammatory responses triggered at later stages of germination, 5 × 104 conidia per well were incubated in the presence or absence of drug for 8 h, to complete the swelling reaction and form short germ tubes. BMMϕs were then added to UV-inactivated fungal cells for 6 h. Similar results were observed with A. fumigatus strain Af293 (figure 3) and ATCC 90906 (not shown).

Figure 3.

Caspofungin and decreases in inflammatory responses to germlings. A-C, Secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or CXCL2 by 1.5 × 105 bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMϕs) incubated with Aspergillus fumigatus germlings for 6 h. A total of 5 × 104 conidia were grown in RP-10+ (see Materials and Methods for details) for 8 h at 37°C with 0-500 ng/mL caspofungin (A, B) or micafungin (C) before UV inactivation and the addition of BMMϕs. B, Cocultures contained 10 μg/mL anti-Dectin (+) or 10 μg/mL isotype control antibody (-). Bar graphs denote the average TNF or CXCL2 concentration (+SD) in 3-4 wells per condition. One of 7 (A) or 3 (B, C) representative experiments is shown. *P < .05, by 2-tailed t test, compared with control condition (i.e., no drug treatment).

The amounts of TNF and CXCL2 released in BMMϕ culture supernatants decreased in a dose-dependent manner if the caspofungin concentration exceeded the MEC (figure 3A). At a drug concentration of 500 ng/mL, the average percentage (±SD) of TNF and CXCL2 released by BMMϕs was 51% ± 7% (range, 43%-64%; n = 7 experiments) and 61% ± 8% (range, 53%-74%; n = 7 experiments) respectively, compared with the amount released from untreated samples. Inflammatory responses of BMMϕs were 90%-95% attributable to Dectin-1 signaling, and drug treatment reduced Dectin-1-associated production of TNF and CXCL2 (figure 3B). Germlings grown in micafungin elicited a similar decrease in TNF and CXCL2 secretion by BMMϕs (figure 3C), indicating a general effect of echinocandin drugs.

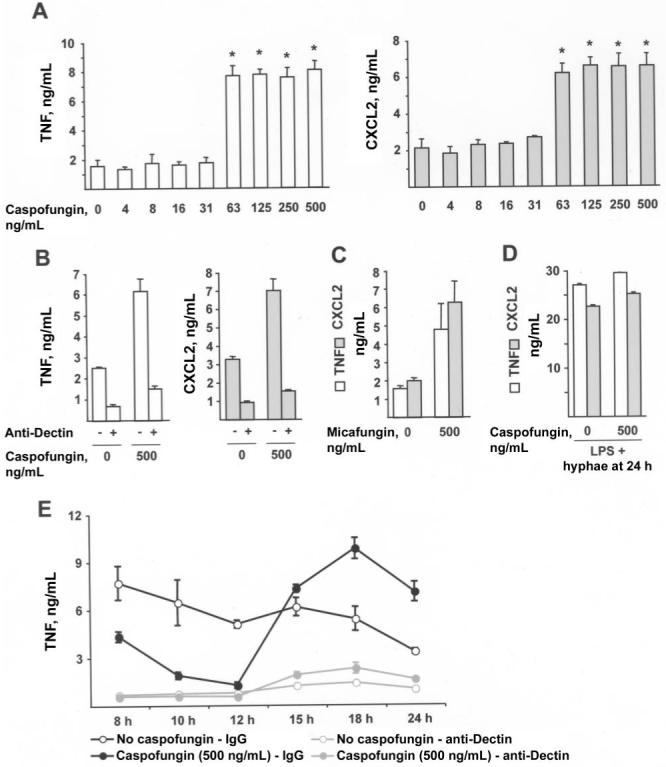

Caspofungin and enhancement of inflammatory responses to A. fumigatus hyphae

To examine inflammatory responses to hyphae, 5 × 104 conidia were grown for 24 h in medium containing 0-500 ng/mL caspofungin, and they were then inactivated by UV exposure. Despite a marked reduction in fungal growth in drug-treated wells (see below), BMMϕ inflammatory responses were enhanced in a dose-dependent manner (figure 4A). Fungal hyphae grown in 500 ng/mL caspofungin induced an average (±SD) of 4.11-fold (±2.39-fold) more TNF (range, 1.90- to 7.84-fold; n = 8 experiments) and 2.90-fold (±1.40-fold) more CXCL2 (range, 1.53- to 5.41-fold; n = 8 experiments) than did hyphae grown in drug-free medium. Enhanced inflammatory responses to drug-treated hyphae were observed with A. fumigatus strain ATCC 90906 as well (not shown).

Figure 4.

Caspofungin and enhancement of inflammatory responses to hyphae. A-D, Secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or CXCL2 by 1.5 × 105 bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMϕs) incubated for 6 h with Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae. A total of 5 × 104 conidia were grown in RP-10+ (see Materials and Methods for details) for 24 h at 37°C with 0-500 ng/mL caspofungin (A, B, D) or micafungin (C) before UV inactivation and the addition of BMMϕs. B and D, Cocultures contained 10 μg/mL anti-Dectin (+), 10 μg/mL isotype control antibody (-), or 100 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide, as indicated. E, TNF secretion by BMMϕs stimulated with UV-inactivated fungal cells grown for the indicated period in RP-10+ (empty circles) or in RP-10+ with 500 ng/mL caspofungin (filled circles). Coincubations were performed in the presence of anti-Dectin (red lines) or control isotype antibody (black lines), as described for panel B. A-E, Bar graphs denote the average TNF or CXCL2 concentration (+SD) in 3-6 wells per condition. One of either 8 (A) or 3 (B-E) representative experiments is shown. *P < .05, by 2-tailed t test, compared with control condition (i.e., no drug treatment).

The increase in secretion of TNF and CXCL2 by BMMϕsin caspofungin-treated samples was attributable to increased Dectin-1-associated signaling (figure 4B). Enhanced BMMϕ inflammatory responses were observed with micafungin-treated hyphae as well (figure 4C). This effect was seen in association with different fungal growth media, both containing serum (RP-10+) and lacking serum (RPMI 1640, 0.165 mol/L 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid [pH 7.0]), and with conidial inocula that ranged from 5 × 103 to 5 × 104 cells (data not shown).

Hyphae may elaborate factors that reduce the inflammatory responses of BMMϕs in proportion to mycelial growth. Because growth is markedly reduced in echinocandin-treated samples (see below), excluding this explanation for the observed difference in inflammatory response is important. To examine whether macrophage responsiveness diminished when cells were stimulated with control hyphae, rather than with drug-treated hyphae, LPS was added to both experimental conditions. Macrophage inflammatory responses were nearly identical in both cases (figure 4D). This finding supports the notion that low-level inflammatory responses to non-drug-treated hyphae and enhanced inflammatory responses to drug-treated hyphae are not associated with changes in macrophage responsiveness to other inflammatory stimuli.

To examine inflammatory responses to A. fumigatus during the transition from germlings to hyphae, fungal cells were grown in drug-free medium or in medium containing caspofungin, and, at defined time points between 8 h and 24 h, they were inactivated by UV exposure. Inflammatory responses decreased as fungal cells completed the transition from germlings to hyphae in drug-free medium, despite the increase in fungal mass that occurred during hyphal growth (figure 4E). In contrast, fungal cells exposed to caspofungin induced a large increase in the secretion of TNF and CXCL2 by macrophages after 12-18 h of growth in medium containing drugs (figure 4E). Drug-treated hyphae were more inflammatory than drug-treated germlings. In all cases examined, inflammatory responses to drug-treated and control cells were highly associated with Dectin-1 signaling.

Caspofungin and alteration of β-glucan immunoreactivity on germ tubes and hyphae

Fungal cells were examined by confocal microscopy to examine drug-dependent changes in surface β-glucan exposure during germ tube formation and hyphal growth. A monoclonal antibody that recognizes β-1,3-glucan was used for experiments involving immunofluorescence [20]. Untreated germlings demonstrated strong β-glucan immunoreactivity on the remnant of the swollen conidium and diffuse staining along the protruding germ tube (figure 5A). In contrast, their drug-treated counterparts lacked β-glucan immunoreactivity on the protruding germ tube.

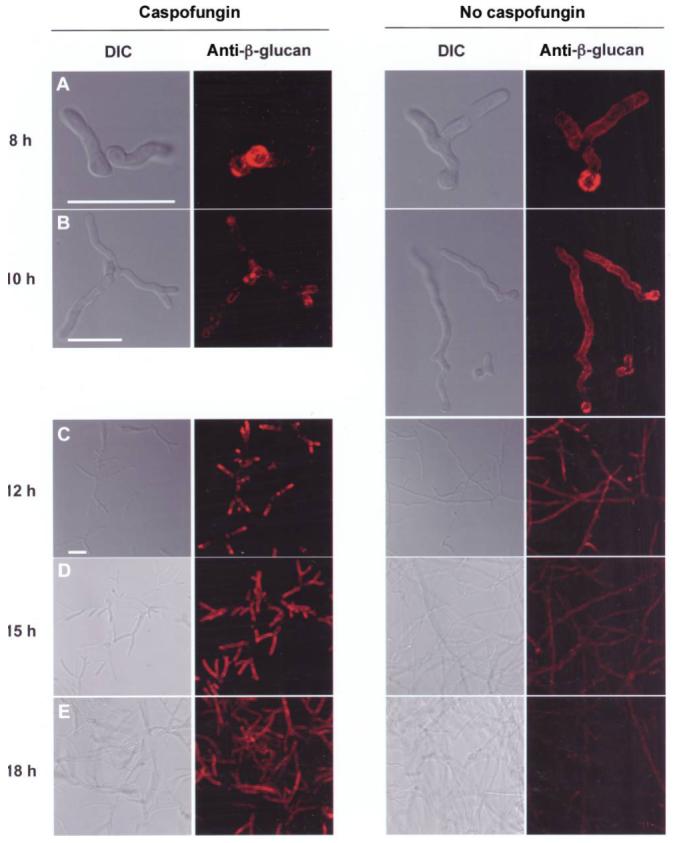

Figure 5.

Caspofungin and modulation of β-glucan immunoreactivity in a stage-specific manner. A-E, A total of 5 × 104 conidia were grown in RP-10+ (see Materials and Methods for details) without drug (left) or with 500 ng/mL caspofungin (right) for 8-18 h, as indicated; stained with an anti-β-glucan antibody (monoclonal antibody 744); and examined by confocal microscopy. Representative epifluorescence and differential interference contrast (DIC) images are shown. Fluorescence images are a composite of scanned images obtained at 0.5-μm (A-B) or 1.0-μm (C-E) intervals. Scale bar, 20 μm.

As filaments increased in length (during 10-12 h of incubation in RP-10+), they remained immunoreactive along the entire structure (figure 5B and C). In drug-treated samples, β-glucan immunoreactivity became apparent on the tips of germ tubes after 10 h of growth (figure 5B), with marked enhancement at distal segments noted after 2 additional hours of growth (figure 5C). At this later point in time, the growth inhibitory effects of caspofungin were apparent.

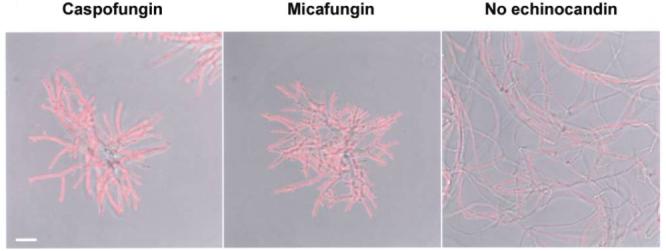

At 15 h of growth, drug-free samples contained weakly immunoreactive and nonreactive hyphae (figure 5D). The morphologically distinct hyphae observed in drug-treated samples displayed intense β-glucan immunoreactivity concentrated at peripheral segments (figure 5D). Drug-treated hyphae displayed persistent β-glucan immunoreactivity after 18 h of growth in caspofungin, predominantly at distal segments but extending to more central areas as well (figure 5E). In contrast, control samples were markedly less immunoreactive than drug-treated cells (at the same time point) and less mature hyphae (figure 5D). At the final time point examined (at 24 h), drug-treated hyphae displayed far greater β-glucan immunoreactivity than did untreated hyphae (figure 6). This finding was noted with different conidial inocula (5 × 103-5 × 104 conidia), fungal growth media, and echinocandin drugs (caspofungin and micafungin) (figure 6) (not shown).

Figure 6.

Echinocandins and increases in β-glucan immunoreactivity on hyphae. A total of 5 × 103 conidia were grown in RP-10+ (see Materials and Methods for details) for 24 h with 500 ng/mL caspofungin (left) or 500 ng/mL micafungin (middle) or without drug (right). Representative fields are shown with composite fluorescence images overlaid on differential interference contrast images. Scale bar, 20 μm.

To examine differences in β-glucan immunoreactivity between drug-treated and untreated hyphae, the integrated fluorescence intensity of β-glucan immunoreactivity was determined for all hyphal filaments within a field of view consisting of ∼30 - 40 optical slices (see Materials and Methods for detail). To relate the β-glucan fluorescence intensity to the hyphal mass within each field of view, fungal cell autofluorescence was recorded to visualize the hyphal cross-sectional area in each optical slice (and field of view). In 2 experiments, drug-treated hyphae displayed >10-fold greater β-glucan immunoreactivity than did untreated hyphae, normalized for hyphal mass (table 1).

Table 1.

Quantitative analysis of β-glucan immunoreactivity for caspofungin-treated and untreated Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae

| Integrated fluorescence intensity/fungal mass,a by hyphae group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Caspofungin treated | Untreated |

| 1 | 21.41b ± 8.34 | 1.83 ± 0.73 |

| 2 | 43.73b ± 6.96 | 2.96 ± 4.67 |

NOTE. Data are the average ratio (±SD) of β-glucan immunofluorescence intensity normalized to hyphal mass, as calculated from 4-5 fields of view per condition.

Arbitrary units.

P < .02, by 2-tailed t test, compared with control condition (untreated hyphae).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found that echinocandins shape inflammatory responses to A. fumigatus through modulation of surface β-glucan content. Surprisingly, this process occurs in a stage-specific manner: drug-treated germlings display diminished surface β-glucan immunoreactivity and elicit reduced inflammatory responses, whereas drug-treated hyphae exhibit a dramatic increase in surface β-glucan immunoreactivity and trigger enhanced inflammatory responses. The latter result is consistent with the finding that macrophages cooperate with caspofungin to inhibit hyphal growth in an additive manner [35]. The results of the present study support echinocandins increasing hyphal susceptibility to Dectin-1-mediated responses by direct effects on the fungal cell wall. Drug-dependent changes in β-glucan exposure and macrophage inflammatory responses occur at drug levels that are relevant for therapy [36].

A second finding is that A. fumigatus, under drug-free conditions, limits β-glucan exposure during hyphal growth, given the low-level Dectin-1-dependent inflammatory response to hyphae, compared with the response to germlings. C. albicans conceals β-glucan during yeast cell and pseudohyphal growth beneath a mannoprotein layer [19]. Shielding β-glucan or limiting surface exposure may provide a growth or survival advantage within the diverse ecological niches inhabited by these organisms [14, 37]. Caspofungin disrupts the normal cell wall architecture of both organisms and exerts similar proinflammatory effects on C. albicans yeast cells [14] and A. fumigatus hyphae. However, in contrast to their effect on responses to C. albicans, echinocandin drugs can decrease inflammatory responses to specific growth stages of A. fumigatus.

The A. fumigatus ΔpksP mutant defective in pigment biosynthesis forms conidia with high levels of surface β-glucan [38]. ΔpksP conidia display heightened in vitro susceptibility to phagocyte defense mechanisms [39] and reduced virulence in animal models of IA [40]. Although this mutant strain likely harbors other changes that influence disease outcome, it is striking that enhanced β-glucan exposure correlates with decreased virulence.

A. fumigatus spores contain minimal amounts of β-glucan on their surface [20], and β-glucans become exposed during swelling and germ tube formation. When caspofungin exposure occurs, a reduction in de novo synthesis may account for the reduced β-glucan surface display on the initial germ tube segment. Alternatively, the initial step of germ tube formation could depend, in part, on preformed stores. Either way, caspofungin appears to prevent the immunoreactive polymer from reaching the fungal surface at the earliest stage of filamentous growth, given the near absence of immunoreactive β-glucan on short drug-treated filaments. Compensatory changes in cell wall constituents or assembly may be associated with the reduced inflammatory responses observed with swollen conidia and germ tubes, at the eventual cost of dysmorphic and stunted growth.

Continued inhibition of glucan synthase leads to a paradoxical increase in surface β-glucan at the ends of growing filaments. Increased surface accumulation of β-glucan may result from secondary changes in the activities of enzymes involved in polymer biosynthesis and turnover (e.g., β-1,3-glucanosyltransferases [41] and β-1,3-glucanases [42-44]). Because Dectin-1 binds exclusively to β-1,3-linked glucose oligomers [45], echinocandin-induced changes in other polysaccharide constituents of the cell wall are unlikely to contribute directly to the Dectin-1-dependent inflammatory responses measured in these studies.

The antifungal properties of echinocandin drugs may not be adequately described by their effects on growth [37, 46]. Compounds with direct immune stimulatory properties or those that enhance the immune recognition of target microbes have an increasing role in the treatment of infectious diseases. For example, the Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonist imiquimod is effective against lesions associated with human papillomavirus [47]. A variety of compounds or constituents of antifungal agents have immune modulatory properties that may enhance fungal clearance. Amphotericin B directly stimulates TLR-dependent inflammatory cytokine release in a fungus-independent manner [48]. Recently, empty liposomes were found to have beneficial immune stimulatory effects in a murine model of IA [49]. In contrast, echinocandin drugs are unlikely to cause general activation of inflammatory responses. Their immunomodulatory properties depend on the presence of fungal cells, providing a mechanism by which cell-mediated and humoral responses [50] are focused to sites of hyphal growth. Recognition that caspofungin modulates inflammatory responses to specific growth forms of A. fumigatus has potential implications for prophylactic and therapeutic strategies. Because host inflammatory responses make a critical contribution to the clearance of invasive aspergillosis, echinocandin drugs may be most effective for hyphal lesions and at the time of host myeloid cell recovery.

Acknowledgments

Candida albicans strain SC5314 was a gift from Brad Spellberg (Harbor-University of California Los Angeles Medical Center). We thank Ewa Menet for outstanding technical assistance and Yevgeniy Romin and Katia Manova-Todorova for assistance with confocal microscopy and image analysis.

Financial support: T.M.H. is a Biomedical Fellow of the Charles H. Revson Foundation; National Institutes of Health (training grant T32 [to T.M.H.], grants R01 AI059663 and R21 AI065745 [to M.F.], and grant R01 AI67359 [to E.G.P.]).

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: none reported.

References

- 1.Deresinski SC, Stevens DA. Caspofungin. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1445–57. doi: 10.1086/375080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hope WW, Shoham S, Walsh TJ. The pharmacology and clinical use of caspofungin. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2007;3:263–74. doi: 10.1517/17425255.3.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin SJ, Schranz J, Teutsch SM. Aspergillosis case-fatality rate: systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:358–66. doi: 10.1086/318483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latgé JP. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:310–50. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes PD, Marr KA. Aspergillosis: spectrum of disease, diagnosis, and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006;20:545–61. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beauvais A, Drake R, Ng K, Diaquin M, Latgé JP. Characterization of the 1,3-β-glucan synthase of Aspergillus fumigatus. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:3071–8. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-12-3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abruzzo GK, Flattery AM, Gill CJ, et al. Evaluation of the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872): efficacies in mouse models of disseminated aspergillosis, candidiasis, and cryptococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2333–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abruzzo GK, Gill CJ, Flattery AM, et al. Efficacy of the echinocandin caspofungin against disseminated aspergillosis and candidiasis in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2310–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2310-2318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petraitiene R, Petraitis V, Groll AH, et al. Antifungal efficacy of caspofungin (MK-0991) in experimental pulmonary aspergillosis in persistently neutropenic rabbits: pharmacokinetics, drug disposition, and relationship to galactomannan antigenemia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:12–23. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.1.12-23.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiederhold NP, Kontoyiannis DP, Chi J, Prince RA, Tam VH, Lewis RE. Pharmacodynamics of caspofungin in a murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: evidence of concentration-dependent activity. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1464–71. doi: 10.1086/424465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurtz MB, Heath IB, Marrinan J, Dreikorn S, Onishi J, Douglas C. Morphological effects of lipopeptides against Aspergillus fumigatus correlate with activities against (1,3)-β-d-glucan synthase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1480–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.7.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartizal K, Gill CJ, Abruzzo GK, et al. In vitro preclinical evaluation studies with the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2326–32. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahn JN, Hsu MJ, Racine F, Giacobbe R, Motyl M. Caspofungin susceptibility in Aspergillus and non-Aspergillus molds: inhibition of glucan synthase and reduction of β-d-1,3 glucan levels in culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2214–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01610-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wheeler RT, Fink GR. A drug-sensitive genetic network masks fungi from the immune system. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e35. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowman JC, Hicks PS, Kurtz MB, et al. The antifungal echinocandin caspofungin acetate kills growing cells of Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3001–12. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.3001-3012.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown GD, Gordon S. Immune recognition: a new receptor for β-glucans. Nature. 2001;413:36–7. doi: 10.1038/35092620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown GD. Dectin-1: a signalling non-TLR pattern-recognition receptor. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:33–43. doi: 10.1038/nri1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steele C, Marrero L, Swain S, et al. Alveolar macrophage-mediated killing of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. muris involves molecular recognition by the Dectin-1 β-glucan receptor. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1677–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gantner BN, Simmons RM, Underhill DM. Dectin-1 mediates macrophage recognition of Candida albicans yeast but not filaments. EMBO J. 2005;24:1277–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hohl TM, Van Epps HL, Rivera A, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus triggers inflammatory responses by stage-specific β-glucan display. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e30. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steele C, Rapaka RR, Metz A, et al. The β-glucan receptor dectin-1 recognizes specific morphologies of Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e42. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gersuk GM, Underhill DM, Zhu L, Marr KA. Dectin-1 and TLRs permit macrophages to distinguish between different Aspergillus fumigatus cellular states. J Immunol. 2006;176:3717–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viriyakosol S, Fierer J, Brown GD, Kirkland TN. Innate immunity to the pathogenic fungus Coccidioides posadasii is dependent on Toll-like receptor 2 and Dectin-1. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1553–60. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1553-1560.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehrad B, Strieter RM, Standiford TJ. Role of TNF-α in pulmonary host defense in murine invasive aspergillosis. J Immunol. 1999;162:1633–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warris A, Bjorneklett A, Gaustad P. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis associated with infliximab therapy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1099–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehrad B, Strieter RM, Moore TA, Tsai WC, Lira SA, Standiford TJ. CXC chemokine receptor-2 ligands are necessary components of neutrophil-mediated host defense in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Immunol. 1999;163:6086–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuh JM, Blease K, Hogaboam CM. CXCR2 is necessary for the development and persistence of chronic fungal asthma in mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:1447–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibrahim-Granet O, Philippe B, Boleti H, et al. Phagocytosis and intracellular fate of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia in alveolar macrophages. Infect Immun. 2003;71:891–903. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.891-903.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philippe B, Ibrahim-Granet O, Prévost MC, et al. Killing of Aspergillus fumigatus by alveolar macrophages is mediated by reactive oxidant intermediates. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3034–42. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3034-3042.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown GD, Taylor PR, Reid DM, et al. Dectin-1 is a major β-glucan receptor on macrophages. J Exp Med. 2002;196:407–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor PR, Tsoni SV, Willment JA, et al. Dectin-1 is required for β-glucan recognition and control of fungal infection. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:31–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serrano-Gómez D, Domínguez-Soto A, Ancochea J, Jimenez-Heffernan JA, Leal JA, Corbi AL. Dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin mediates binding and internalization of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by dendritic cells and macrophages. J Immunol. 2004;173:5635–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGreal EP, Rosas M, Brown GD, et al. The carbohydrate-recognition domain of Dectin-2 is a C-type lectin with specificity for high mannose. Glycobiology. 2006;16:422–30. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato K, Yang XL, Yudate T, et al. Dectin-2 is a pattern recognition receptor for fungi that couples with the Fc receptor γ chain to induce innate immune responses. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38854–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiller T, Farrokhshad K, Brummer E, Stevens DA. The interaction of human monocytes, monocyte-derived macrophages, and polymorphonuclear neutrophils with caspofungin (MK-0991), an echinocandin, for antifungal activity against Aspergillus fumigatus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;39:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(00)00236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stone JA, Holland SD, Wickersham PJ, et al. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of caspofungin in healthy men. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:739–45. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.739-745.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hohl TM, Pamer EG. Cracking the fungal armor. Nat Med. 2006;12:730–2. doi: 10.1038/nm0706-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luther K, Torosantucci A, Brakhage AA, Heesemann J, Ebel F. Phagocytosis of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by murine macrophages involves recognition by the dectin-1 β-glucan receptor and Toll-like receptor 2. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:368–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jahn B, Langfelder K, Schneider U, Schindel C, Brakhage AA. PKSP-dependent reduction of phagolysosome fusion and intracellular kill of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by human monocyte-derived macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4:793–803. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langfelder K, Jahn B, Gehringer H, Schmidt A, Wanner G, Brakhage AA. Identification of a polyketide synthase gene (pksP) of Aspergillus fumigatus involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis and virulence. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1998;187:79–89. doi: 10.1007/s004300050077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mouyna I, Morelle W, Vai M, et al. Deletion of GEL2 encoding for a β(1-3)glucanosyltransferase affects morphogenesis and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:1675–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fontaine T, Hartland RP, Beauvais A, Diaquin M, Latge JP. Purification and characterization of an endo-1,3-β-glucanase from Aspergillus fumigatus. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:315–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0315a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fontaine T, Hartland RP, Diaquin M, Simenel C, Latgé JP. Differential patterns of activity displayed by two exo-β-1,3-glucanases associated with the Aspergillus fumigatus cell wall. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3154–63. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3154-3163.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mouyna I, Sarfati J, Recco P, Fontaine T, Henrissatz B, Latge JP. Molecular characterization of a cell wall-associated β(1-3)endoglucanase of Aspergillus fumigatus. Med Mycol. 2002;40:455–64. doi: 10.1080/mmy.40.5.455.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palma AS, Feizi T, Zhang Y, et al. Ligands for the β-glucan receptor, Dectin-1, assigned using “designer” microarrays of oligosaccharide probes (neoglycolipids) generated from glucan polysaccharides. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5771–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Douglas CM. Understanding the microbiology of the Aspergillus cell wall and the efficacy of caspofungin. Med Mycol. 2006;44:S95–9. doi: 10.1080/13693780600981684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garland SM. Imiquimod. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:85–9. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sau K, Mambula SS, Latz E, Henneke P, Golenbock DT, Levitz SM. The antifungal drug amphotericin B promotes inflammatory cytokine release by a Toll-like receptor- and CD14-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37561–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lewis RE, Chamilos G, Prince RA, Kontoyiannis DP. Pretreatment with empty liposomes attenuates the immunopathology of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in corticosteroid-immunosuppressed mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1078–81. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01268-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Torosantucci A, Bromuro C, Chiani P, et al. A novel glyco-conjugate vaccine against fungal pathogens. J Exp Med. 2005;202:597–606. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]