SUMMARY

β1 integrins are major cell surface receptors for fibronectin. Some integrins, including β1 integrins, are known to undergo constitutive endocytosis and recycling. Integrin endocytosis/recycling has been implicated in regulation of cell migration. However, the mechanisms by which integrin endocytosis/recycling regulates cell migration, and other biological consequences of integrin trafficking are not completely understood. We previously showed that turnover of extracellular matrix (ECM) fibronectin occurs via receptor-mediated endocytosis. In this manuscript, we investigate the biological relevance of β1 integrin endocytosis to fibronectin matrix turnover. First, we demonstrate that β1 integrins, including α5β1 play an important role in endocytosis and turnover of matrix fibronectin. Second, we show that caveolin-1 constitutively regulates endocytosis of α5β1 integrins, and that α5β1 integrin endocytosis can occur in the absence of fibronectin and fibronectin matrix. We also show that down-regulation of caveolin-1 expression by siRNA results in marked reduction of β1 integrin and fibronectin endocytosis. Hence, caveolin-1-dependent β1 integrin and fibronectin endocytosis plays a critical role in fibronectin matrix turnover, and may contribute to abnormal ECM remodeling that occurs in fibrotic disorders.

Keywords: integrin, extracellular matrix, endocytosis, caveolae, fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

Degradation and removal of ECM proteins is a cell-mediated process, which is involved in a number of physiological processes, such as development, postnatal tissue remodeling and tissue repair (Clark, 1996; Holmbeck et al., 1999; Vu et al., 1998). Impaired or abnormal degradation/removal of ECM components contributes to the onset and progression of many diseases, including fibrosis, arthritis and cancer (Hotary et al., 2003; Kurban et al., 2006; Liotta and Kohn, 2001; Mutsaers et al., 1997; Poole et al., 2003). Two principal molecular mechanisms are believed to be involved in the turnover of ECM. One of them is extracellular degradation of ECM proteins by matrix metalloproteases (MMPs), plasmin and other proteases (Marchina and Barlati, 1996; Shapiro, 1998). The other pathway occurs via internalization of ECM proteins and intracellular degradation in lysosomes (Godyna et al., 1995; Memmo and McKeown-Longo, 1998; Murphy-Ullrich and Mosher, 1987; Wienke et al., 2003). These two pathways are not mutually exclusive, and probably work collaboratively during ECM turnover. Many ECM proteins form supramolecular complexes (Kuivaniemi et al., 1991; McKeown-Longo and Mosher, 1989; Sasaki et al., 2004; Schwarzbauer and Sechler, 1999; van der Rest and Garrone, 1991). Thus, prior to internalization, extracellular degradation may partially breakdown large multimers or cross-linked molecules. Additionally, some fragments derived from ECM proteins possess functions distinct from the intact proteins (Giannelli et al., 1997; O’Reilly et al., 1997; Sasaki et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2001). Hence, cellular internalization can provide a way to regulate the availability of ECM fragments that may have potent biological effects. However, at present, mechanisms and pathways for degradation/removal of supramolecular ECM components are not completely understood.

Integrin receptors play important roles in mediating cell adhesion, contractility, motility and growth (Aplin et al., 1999; Burridge and Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, 1996; Howe et al., 1998; Hynes, 1992; Hynes, 2002). Ligation of integrins with ECM ligands can activate signaling pathways and influence cytoskeleton organization, which account for many of the biological functions of integrins (Brakebusch and Fassler, 2003; Geiger et al., 2001; Ginsberg et al., 2005). Integrins are known to be constitutively endocytosed and recycled (Bretscher, 1989; Bretscher, 1992; Pellinen and Ivaska, 2006). Disruption of integrin endocytosis and recycling can impair cell spreading and migration (Proux-Gillardeaux et al., 2005; Roberts et al., 2001). Relatively little attention has been given to the fate of the ECM proteins that are ligated to integrins during integrin endocytosis, or to how ECM proteins may modify integrin internalization. In addition, most studies on integrin trafficking do not distinguish between ECM-bound and -unbound forms of the receptors. ECM remodeling has been shown to be critical to many cellular functions, including cell migration and invasion (Engelholm et al., 2003; Hocking and Chang, 2003; Hornebeck et al., 2002; Hotary et al., 2000; Sabeh et al., 2004). Therefore, coupling of ECM remodeling with integrin endocytosis/recycling may be an important feature of integrin trafficking.

We established a fibronectin null myofibroblast (FN-null MF) cell culture model system (Sottile et al., 1998). The turnover of fibronectin matrix can be easily induced in FN-null MFs when soluble fibronectin is removed from the culture media. Using this model system, we previously demonstrated that fibronectin matrix turnover plays an important role in governing ECM turnover (Sottile and Hocking, 2002). We also showed that fibronectin matrix turnover occurs through receptor-mediated endocytosis and is followed by lysosomal degradation (Sottile and Chandler, 2005). In this manuscript, we used this experimental model system to explore the role of integrin endocytosis in fibronectin matrix turnover. We demonstrate that β1 integrins, including α5β1, are fibronectin matrix endocytic receptors. Moreover, we show that caveolin-1 (official protein symbol CAV1) constitutively regulates α5β1 integrin endocytosis, regardless of the presence or absence of fibronectin and fibronectin matrix. We previously demonstrated that down-regulation of caveolin-1 by siRNA inhibits fibronectin matrix turnover. Here we show that down-regulation of caveolin-1 also impairs β1 integrin endocytosis. These data demonstrate the importance of caveolin-1-dependent integrin endocytosis in regulating fibronectin matrix turnover.

RESULTS

β1 integrins colocalize with internalized fibronectin during long-term fibronectin matrix turnover

Fibronectin matrix turnover occurs through receptor mediated endocytosis and intracellular degradation in a process that is regulated by caveolin-1 (Sottile and Chandler, 2005). Here we investigate the receptors that are involved in endocytosis of fibronectin and turnover of matrix fibronectin. Both integrins and proteoglycans are known to bind fibronectin, and to participate in endocytosis of various ligands, including ECM proteins (Chen et al., 1996; McKeown-Longo and Panetti, 1993; Memmo and McKeown-Longo, 1998; Murphy-Ullrich and Mosher, 1987; Pijuan-Thompson and Gladson, 1997), and hence, are both candidates for mediating fibronectin turnover.

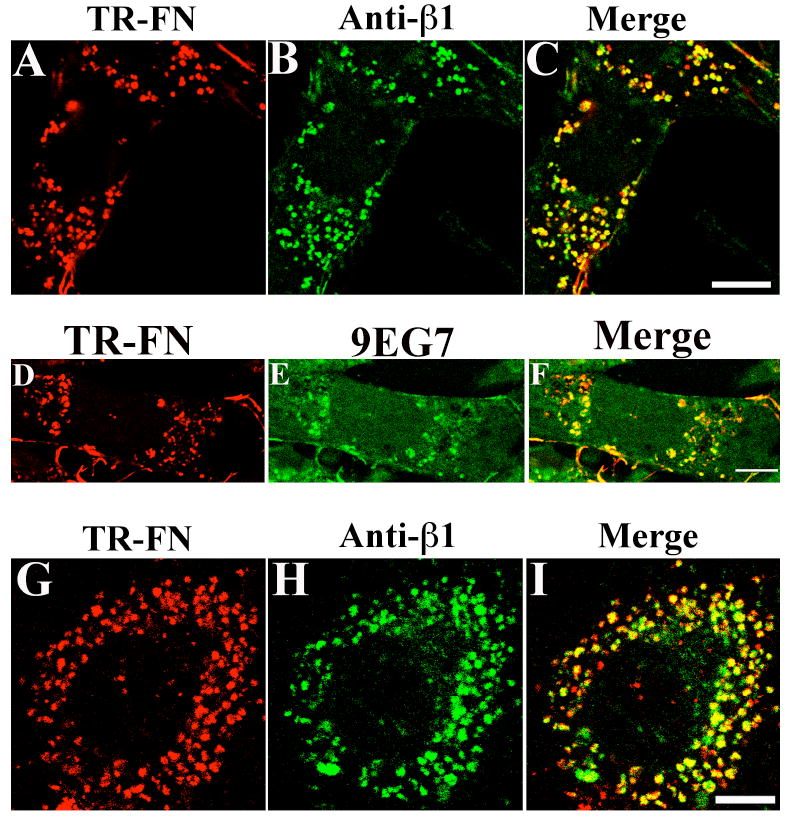

Some integrins, including β1 integrins, undergo constitutive endocytosis and recycling (Bretscher, 1989; Bretscher, 1992; Caswell and Norman, 2006; Pellinen and Ivaska, 2006; Sczekan and Juliano, 1990). α5β1 and αvβ3 are major fibronectin receptors expressed in FN-null MFs (Sottile et al., 1998). As a first step in determining whether integrins are involved in regulating fibronectin matrix turnover, we tested whether fibronectin and β1 or β3 integrins are trafficked to the same endocytic compartment. FN-null MFs were incubated overnight with Texas Red (TR)-conjugated fibronectin to allow them to establish a robust fibronectin matrix. Cells were washed, and then chased with culture media lacking fibronectin and containing chloroquine, an inhibitor of lysosomal hydrolases (de Duve et al., 1974) that also inhibits fibronectin degradation (Sottile and Chandler, 2005). Using this pulse-chase assay, we previously showed that there is a time dependent loss of fibronectin matrix fibrils and a corresponding increase in fibronectin degradation during the chase period (Sottile and Hocking, 2002). As shown in Fig. 1A, internalized fibronectin was readily detected in permeablized cells following the chase period, and showed extensive colocalization with β1 integrins, as seen by the yellow staining in the overlay image (Fig. 1C). To ensure that the β1 integrins detected in fibronectin-containing vesicles are internalized from the cell surface, cell surface β1 integrins were labeled with the 9EG7 antibody, which recognizes the ligand-bound conformation of β1 integrins (Bazzoni et al., 1995; Lenter et al., 1993). 9EG7 (Fig. 1E, F), but not the isotype control antibody (data not shown), was internalized into fibronectin-containing intracellular vesicles during fibronectin matrix turnover. Extensive colocalization of internalized fibronectin and β1 integrins was also seen in SMCs (Fig. 1G-I).

Figure 1. Colocalization of internalized fibronectin with β1 integrins.

(A-C) FN-null MFs were incubated with 10 μg/mL TR-fibronectin overnight. Cells were washed and then incubated for 12 hours in cell culture media lacking fibronectin, but containing 50 μM chloroquine. Cells were stained with an anti-β1 integrin antibody (HMβ1-1). A, TR-fibronectin; B, β1 integrin; C, overlay image. (D-F) FN-null MFs were incubated with 10 μg/ml TR-fibronectin overnight. Cells were washed, and then incubated with 10 μg/mL 9EG7 at 4°C for 30 minutes. Cells were washed, and then chased for 4 hours with cell culture media lacking fibronectin, but containing 100 μM chloroquine. Cells were stained with a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. D, TR-fibronectin; E, 9EG7 (β1 integrin); F, overlay image. (G-I) SMCs were incubated with 10 μg/mL TR-fibronectin and 50 μM chloroquine for 12 hours. Cells were stained using an anti-β1 integrin antibody. G, TR-fibronectin; H, β1 integrin (FITC); I, overlay image. All images are optical sections collected from a confocal microscope. Scale bar, 10μm.

Fibronectin and β1 integrins colocalize shortly after the initiation of endocytosis

To determine whether fibronectin and β1 integrins are similarly colocalized at early times after the initiation of endocytosis, we developed a short-term fibronectin endocytosis pulse-chase assay. In this assay, fluorescently labeled fibronectin is added to the culture medium and allowed to bind to cells for 1 hour at 4°C (pulse phase). The culture media containing unbound fibronectin is then replaced with media lacking fibronectin, and the cells incubated at 37°C (chase phase) to allow endocytosis to occur. Intracellular fibronectin was detected by confocal microscopy as soon as 30 minutes following the start of the chase (Fig. 2A). The FN-null MFs in Fig. 2 were co-incubated with FITC-conjugated 9EG7 during the pulse phase. Internalized TR-fibronectin (Fig. 2A) and FITC-9EG7 (Fig. 2B) were extensively colocalized (Fig. 2C, arrowheads point to yellow staining). Quantitative analysis of confocal z-sections showed that 75% of the internalized fibronectin colocalized with 9EG7 (β1 integrins).

Figure 2. Colocalization of internalized fibronectin and β1 integrins shortly after initiation of endocytosis.

FN-Null MFs were incubated with 10 μg/mL TR-fibronectin and 50 μg/mL FITC-conjugated 9EG7 at 4°C for 1 hour during the pulse. After 30 minutes of chase at 37°C, cells were incubated with 0.2% trypan blue for 3 minutes to quench extracellular fluorescence. A, TR-fibronectin; B, FITC-conjugated 9EG7; C, overlay images. Arrowheads in C point to colocalized TR-Fibronectin and FITC-9EG7. These images are optical sections collected from a confocal microscope. Scale bar, 10 μm.

α5 integrins also colocalize with internalized fibronectin

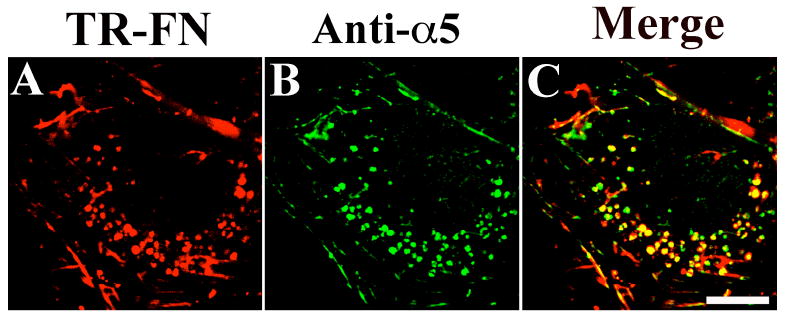

Six different α subunits form dimeric complexes with β1 integrins and function as fibronectin receptors (Johansson et al., 1997; Plow et al., 2000). Because α5 and αv integrins are expressed in FN-null MFs in relatively high amounts (Sottile et al., 1998), we first focused on determining whether these two α subunits are trafficked to the same endocytic compartment as fibronectin. We used rat SMCs for these experiments, since the available α5 antibodies did not strongly recognize intracellular α5 integrin in mouse cells. There was substantial colocalization of α5 integrin (Fig. 3B) and fibronectin (Fig. 3A) in intracellular vesicles (Fig. 3C, yellow staining). In contrast, there was no detectable αv or α3 integrins in fibronectin-containing vesicles (data not shown).

Figure 3. Colocalization of internalized fibronectin with α5 integrins.

SMCs were incubated with 10 μg/mL TR-fibronectin and 50 μM chloroquine for 8 hours. Cells were stained using an anti-α5 integrin antibody (AB1928). A, TR-fibronectin; B, α5 integrin; C, overlay image. These images are optical sections collected from a confocal microscope. Scale bar, 10μm.

Quantitation of fibronectin endocytosis

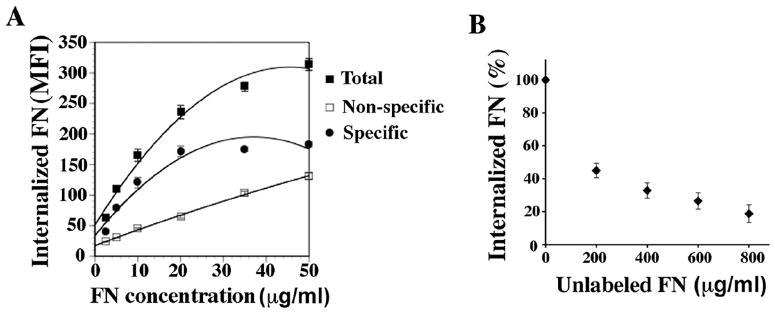

To further establish the role of integrins in regulating fibronectin endocytosis, we combined our short-term fibronectin endocytosis pulse-chase assay with flow cytometry. For these experiments, fluorescently labeled fibronectin was added to cells at 4°C during the pulse. The labeled fibronectin was removed, and the cells switched to 37°C to initiate endocytosis. At the end of the chase, the remaining extracellular fibronectin was removed by proteolytic digestion, and quenched by trypan blue as described in Methods (Hed, 1977; Van Amersfoort and Van Strijp, 1994). The fluorescence signal emitted from internalized fibronectin was measured by flow cytometry.

As shown in Fig. 4A, there was a dose-dependent increase in the level of endocytosed fibronectin with increasing concentrations of added fibronectin up to 20-30 μg/mL. To determine whether fibronectin endocytosis is competable, a given dose of Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488)-fibronectin (10 μg/mL) was incubated with cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of unlabeled fibronectin during the pulse phase. As shown in Fig. 4B, endocytosis of AF488-fibronectin was maximally (81%) inhibited by 800 μg/mL unlabeled fibronectin. The experiment in Fig. 4A was performed in the absence or presence of excess unlabelled fibronectin (800 μg/mL) during the pulse phase. Non-specific endocytosis is defined as that which occurs in the presence of excess unlabelled fibronectin. The non-specific component in this assay likely represents the non-competable fraction of fibronectin binding. The linear increase in non-specific fibronectin endocytosis parallels the linear increase in non-competable fibronectin binding that is seen when 125I fibronectin is added to adherent cells in the presence of excess unlabelled fibronectin (McKeown-Longo and Mosher, 1983). Fibronectin internalization is saturated at fibronectin concentrations above 30-50 μg/mL, as shown by the plateau in the endocytosis curve at high concentrations of added fibronectin (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Quantitation of Fibronectin endocytosis.

(A) FN-null MFs were incubated with 2.5-50 μg/mL AF488-conjugated fibronectin at 4°C during the pulse phase (total endocytosis). Some samples were co-incubated with 800 μg/mL unlabeled fibronectin to determine non-specific endocytosis. Cells were chased in the absence of fibronectin for 2 hours at 37°C, and then processed for flow cytometry to quantitate endocytosed fibronectin. Specific endocytosis was determined by subtracting non-specific endocytosis from total endocytosis. The graph in A shows the best-fit curve of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of internalized AF488-fibronectin. Data represents the mean of duplicate samples and error bars the range.

(B) FN-null MFs were incubated with 10 μg/mL AF488-fibronectin in the presence of increasing concentrations of unlabeled fibronectin (0-800 μg/mL) during the pulse phase. Cells were chased in the absence of fibronectin for 2 hours at 37°C, and then processed for flow cytometry to quantitate endocytosed AF488-fibronectin. The amount of internalized AF488-fibronectin is reported as percent control internalization (cells incubated in the absence of unlabelled fibronectin, which was set equal to 100%). Data represents the mean of duplicate samples and error bars the range.

β1 integrins function as fibronectin endocytic receptors

Endocytosed fibronectin colocalizes with β1 and α5 integrins (Figs. 1-3), suggesting that these integrins may be involved in fibronectin endocytosis. To determine whether β1 integrins are functionally required for fibronectin endocytosis in FN null MFs, we used function blocking anti-integrin antibodies and assessed their effect on fibronectin internalization. Prior to the pulse phase, FN-null MFs were pre-incubated with β1 antibodies at 4°C, followed by the addition of fluorescently labeled fibronectin. Addition of β1 integrin inhibitory antibodies substantially reduced fibronectin endocytosis (Fig. 5A-B). Flow cytometry was used to quantitate the level of internalized fibronectin. There was a 70.2±3.5% reduction in internalized fibronectin in cells treated with β1 inhibitory antibodies (Fig. 5C). We examined the cell surface levels of fibronectin both at the beginning and end of the chase period using western blot analysis. There was a relatively small reduction (25%) in cell surface fibronectin at the beginning of the chase in cells treated with β1 inhibitory antibodies in comparison with control cells (data not shown). When measured at the end of chase period, there was a 14.5% reduction in cell surface fibronectin in cells treated with β1 inhibitory antibodies. The smaller reduction in cell surface fibronectin at 2 hour of chase (14.5% vs. 25%) could reflect the higher rate of endocytosis in the control cells, which leads to a greater reduction of cell surface fibronectin over the course of 2 hours. These data show that the reduction in the levels of endocytosed fibronectin in cells treated with β1 inhibitory antibodies cannot be attributed to the reduced availability of fibronectin to cells. β3 inhibitory antibodies did not have any effect on fibronectin endocytosis (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Blocking of β1 integrin inhibits fibronectin endocytosis.

(A-C) FN-null MFs were incubated with 25 μg/mL β1 antibodies (Ha2/5) or isotype control antibodies at 4°C for 30 minutes. 10 μg/mL TR-fibronectin (A, B) or AF488-fibronectin (C) was then added to the media and cells were processed for fibronectin endocytosis pulse-chase assays. After 2 hours of chase, cells were either fixed for imaging assay (A, β1 inhibition; B, isotype control), or processed for flow cytometry to quantitate endocytosed fibronectin (C). The numbers over the peaks in C are the MFI of internalized AF 488-fibronectin. (D-F) SMCs were seeded in serum free media on vitronectin-coated dishes. Cells were allowed to adhere for 3 hours and then processed for integrin blocking assay as described above for FN-null MFs. (D) 25 μg/mL β1 inhibitory antibodies (Ha2/5); (E) isotype control; Blue: DAPI. (F) Quantitation of endocytosed fibronectin in SMCs by flow cytometry. The numbers over the peaks in F are the MFI of internalized AF 488-fibronectin. Scale bar, 10μm.

When SMCs were pretreated with β1 integrin inhibitory antibodies (Fig. 5D), there was also a striking decrease in intracellular accumulation of fibronectin in comparison with control cells (Fig. 5E). Flow cytometric analysis indicated that fibronectin endocytosis was reduced 56.5±4.2% in SMCs treated with β1 inhibitory antibodies (Fig. 5F). This decrease could not be attributed to decreased fibronectin binding to the cell surface, since fibronectin binding was only decreased 2% in cells treated by β1 inhibitory antibodies.

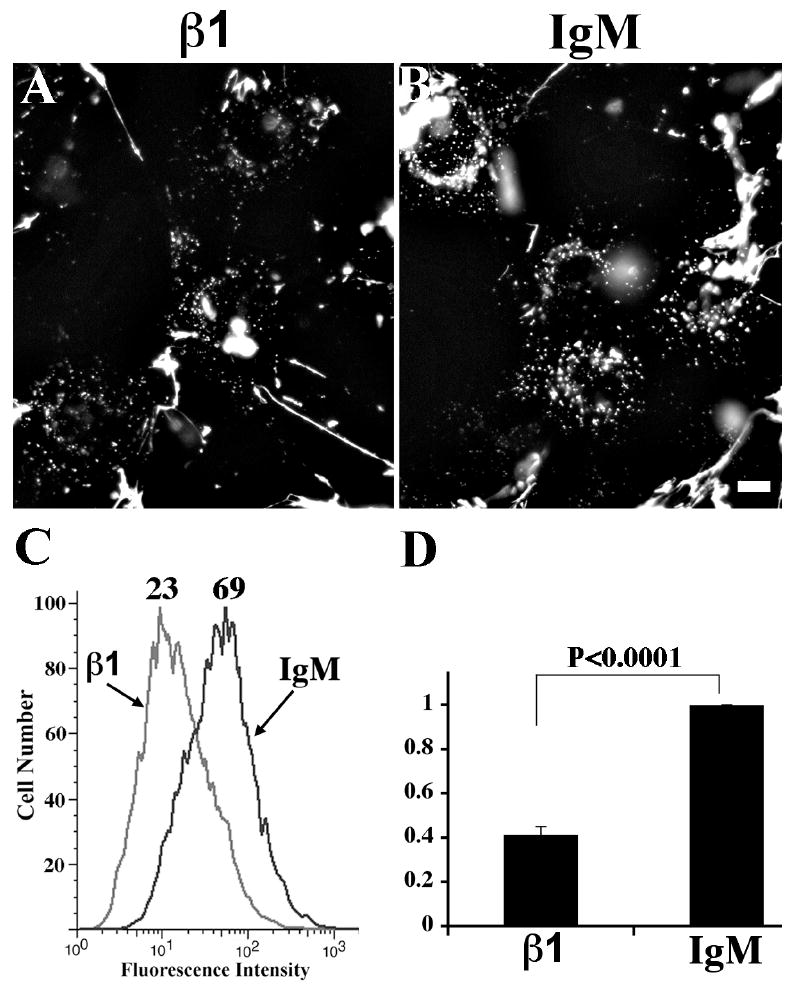

β1 integrins play an important role in endocytosis and turnover of matrix fibronectin

To further establish that the effect of β1 inhibitory antibodies on fibronectin endocytosis was not due to differences in the levels of fibronectin bound to the cell surface or present in the matrix at the beginning of the chase, we performed fibronectin endocytosis assays with FN-null MFs seeded onto fluorescently labeled pre-assembled fibronectin matrices. Some cells were incubated with β1 inhibitory antibodies for 30 minutes prior to seeding. β1 inhibitory antibodies did not affect cell attachment or spreading (data not shown), likely because of the presence of non- β1 integrins, including β3 integrins (Sottile et al., 1998), and because of the presence of other matrix protein in the pre-assembled matrix, including collagen I and heparan sulfate proteoglycans that could promote adhesion in a β1 integrin independent-way. As shown in Fig. 6A-B, fibronectin endocytosis was dramatically reduced in cells treated with β1 inhibitory antibodies. Flow cytometric analysis indicated that there was a significant reduction (58.7±4%) in fibronectin endocytosis in cells treated with β1 inhibitory antibodies (Fig. 6C,D).

Figure 6. Blocking of β1 integrins inhibits endocytosis of fibronectin from pre-assembled matrix.

FN-null MFs were incubated with either 30 μg/mL β1 inhibitory antibody (Ha2/5) or isotype control in suspension at room temperature for 30 minutes prior to seeding on pre-assembled TR-(A, B) or AF488 (C, D)-fibronectin matrix. Cells were cultured for 24 hours at 37°C, and were then either fixed for imaging assay (A, β1 inhibition; B, isotype control) or processed for flow cytometry to quantitate internalized fibronectin (C, D). The numbers over the peaks in C are the MFI of internalized AF 488-fibronectin. Graph in D shows fold change relative to the MFI of endocytosed AF488-fibronectin in cells treated with isotype control IgM, which was set equal to 1 (n=4, mean ± s.d.). Scale bar, 10μm.

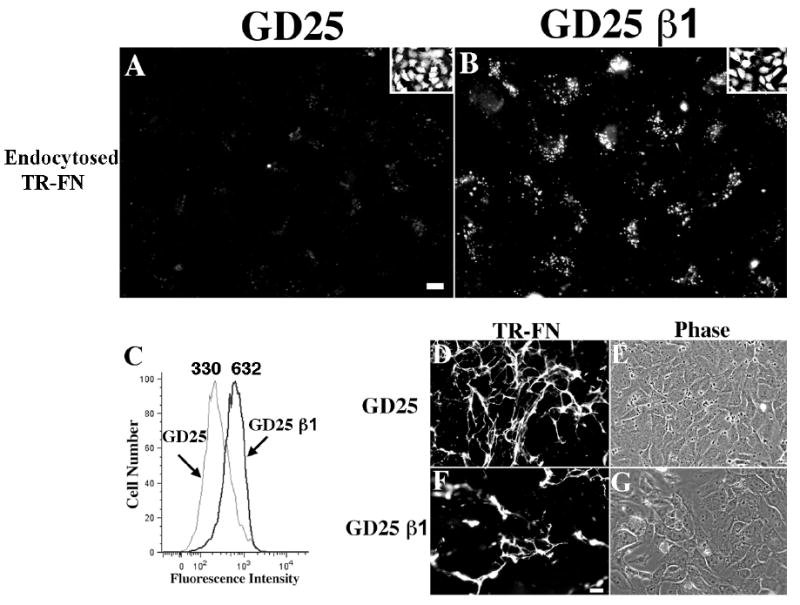

To further demonstrate the requirement for β1 integrins in fibronectin endocytosis, we asked whether fibronectin endocytosis occurs in fibroblastic cells lacking β1 integrins (GD25 cells). GD25 cells and GD25 cells re-expressing β1 integrins (GD25 β1) were seeded onto pre-assembled fibronectin matrix for 24 hours. As shown in Fig. 7A-B, there is a dramatic reduction in fibronectin endocytosis in GD25 cells in comparison to GD25 β1 cells. Flow cytometric analysis indicated that there was a 47.8% reduction in internalized fibronectin in GD25 cells (Fig. 7C). It is likely that the flow cytometry data underestimates the percent inhibition, since the cells have some intrinsic background fluorescence [mean fluorescence intensity (MFI)=77], and because of the non-competable portion of fibronectin endocytosis (Fig. 4B). Turnover of pre-assembled fibronectin matrix fibrils is also reduced in GD25 compared with that in GD25 β1 cells (Fig. 7D-G).

Figure 7. Reduced endocytosis and turnover of pre-assembled fibronectin matrix in β1-integrin-null cells.

GD25 and GD25 β1 re-expressing cells were seeded on pre-assembled TR- (A, B, D, E, F, G) or AF488 (C)-fibronectin matrix and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. (A-B) Cells were incubated with 0.2% trypan blue for 3 minutes and then fixed. Intracellular fibronectin vesicles are shown (A, GD25; B, GD25 β1). The insets show outlines of cells loaded with CellTracker Green. Scale bar, 10μM. (C) Cells were processed for flow cytometry to quantitate endocytosed fibronectin. The numbers over the peaks in C are the MFI of internalized AF 488-fibronectin. (D-G) Cells were fixed without trypan blue treatment to visualize fibronectin fibrils (D, E, GD25; F, G, GD25 β1; E and G are phase images of corresponding fields). Scale bar, 40μm.

Interestingly, in short-term pulse chase experiments, GD25 cells endocytosed soluble fibronectin at levels comparable to GD25 cells re-expressing β1 integrin (Fig. S1A). Fibronectin endocytosis was blocked by RGD peptides (Fig. S1B), but not by the control RGE peptides (Fig. S1C). These data indicate that an alternative integrin receptor can endocytose soluble fibronectin in the absence of β1 integrins, but that this alternative receptor is inefficient at promoting the internalization of matrix fibronectin.

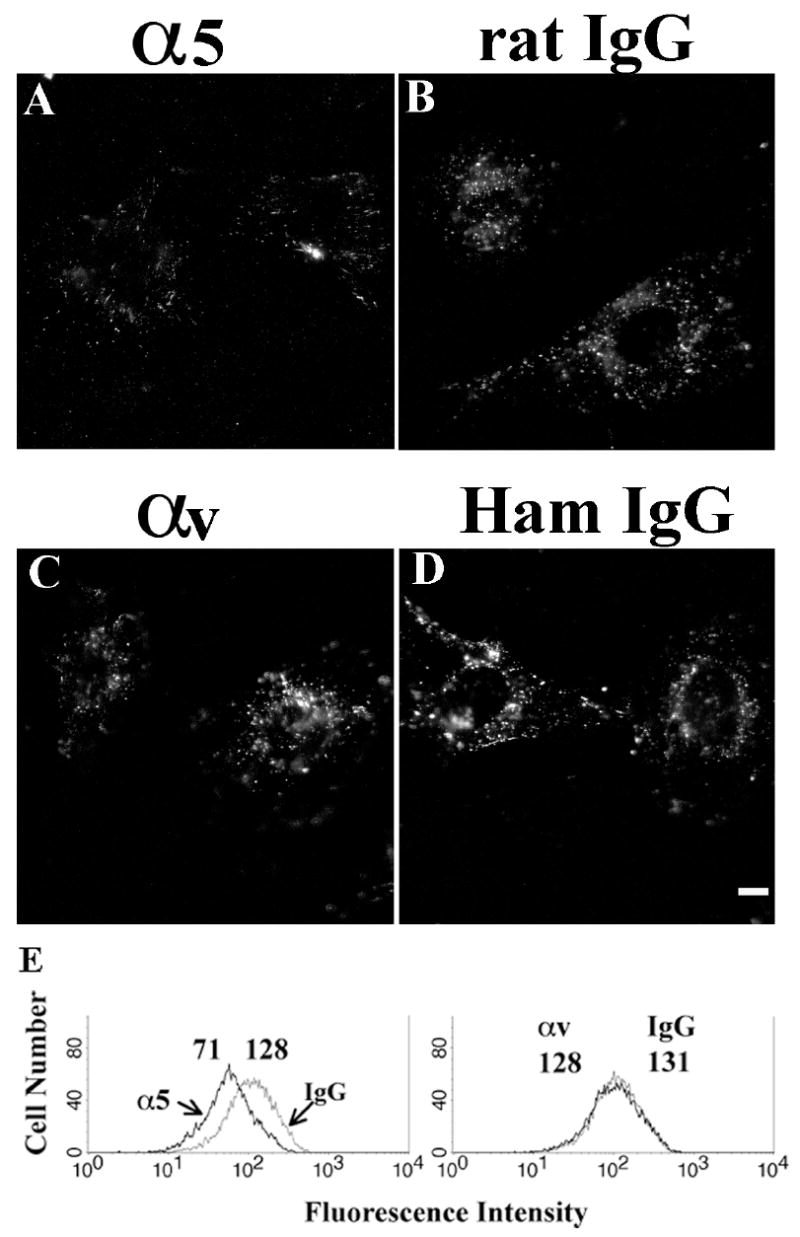

α5 integrins also function as fibronectin endocytic receptors

To determine which α subunit is involved in fibronectin endocytosis, we used the same function blocking protocol as described in Fig. 5. Because α5 and αv integrins are expressed in FN-null MFs in relatively high amounts (Sottile et al., 1998), we first focused on these two α subunits. FN-null MFs were pre-incubated with α5 or αv function inhibitory antibodies at 4°C, prior to the addition of fluorescently-labeled fibronectin during the pulse phase. After 2 hr of chase at 37°C, we found that α5 integrin inhibitory antibodies reduced the intracellular accumulation of fibronectin (Fig. 8A-B). Flow cytometric analysis indicated that there was a 45% reduction in internalized fibronectin in cells treated with 50 μg/mL α5 integrin inhibitory antibody (Fig. 8E). Increasing the concentration of α5 integrin inhibitory antibodies did not cause any further reduction in fibronectin endocytosis (data not shown). This reduction in endocytosed fibronectin could not be totally attributed to a reduction of fibronectin initially bound to the cell-surface (19% reduction). In contrast, αv integrin inhibitory antibodies had no effect on fibronectin endocytosis at 100 μg/mL (Fig. 8C, D and E).

Figure 8. Blocking of α5 integrin partially inhibits fibronectin endocytosis.

FN-null MFs were incubated with 50 μg/mL α5 inhibitory antibodies (5H10-27), or 100 μg/mL αv inhibitory antibodies (H9.2B8), or isotype control IgG at 4°C for 30 minutes. 10 μg/mL TR-fibronectin (A-D) or AF488-fibronectin (E) was added to the media. After 2 hours chase, cells were either fixed for imaging analysis (A, α5 inhibition; B, isotype control of α5; C, αv inhibition; D, isotype control for αv), or processed for flow cytometry (E) to quantitate internalized fibronectin. The numbers over the peaks in E are the MFI of internalized AF 488-fibronectin. Scale bar, 10μm.

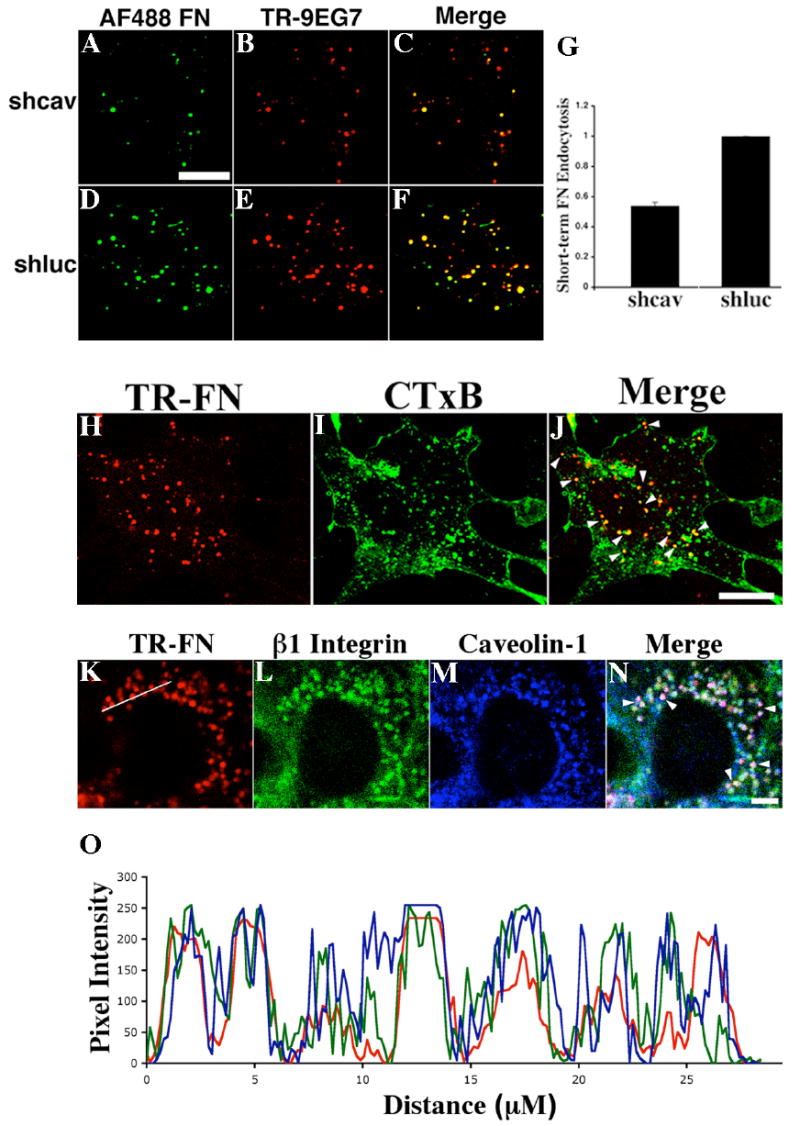

A non-clathrin mechanism mediates fibronectin endocytosis

Using long-term fibronectin matrix turnover pulse-chase assays, we previously showed that fibronectin matrix turnover is inhibited by agents that disrupt caveolae/lipid raft-mediated endocytosis and can be blocked by down-regulation of caveolin-1 (Sottile and Chandler, 2005). To determine whether caveolin-1 also regulates fibronectin endocytosis in short-term pulse chase assays, we examined the levels of internalized fibronectin in FN null MFs expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav) or control siRNA (shluc). As shown in Fig. 9, there is a dramatic reduction in fibronectin (Fig. 9A) and β1 integrin (9EG7, Fig. 9B) endocytosis in cell expressing caveolin-1 siRNA in comparison with control cells. Flow cytometric analysis showed that there was a 46±2% reduction in levels of endocytosed fibronectin in cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (Fig. 9G).

Figure 9.

(A-F) Caveolin-1 regulates short-term fibronectin endocytosis. Cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav, A-C) or control siRNA (shluc, D-F) were incubated with 10 μg/mL AF488-fibronectin and 50 μg/mL TR-conjugated 9EG7 at 4°C for 1 hour during the pulse. After 30 minutes of chase at 37°C, cells were incubated with 0.2% trypan blue for 3 minutes to quench extracellular fluorescence. AF488-fibronectin, A,D; TR-9EG7, B,E; overlay images, C,F. Scale bar, 10μm.

(G) Flow cytometric analysis of endocytosed fibronectin. Cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav) or control siRNA (shluc) were incubated with 10μg/mL AF488-fibronectin at 4°C for 1 hour in the presence or absence of 1mg/ml unlabeled fibronectin. After 30 minutes of chase, cells were processed for flow cytometry. The specific MFI was determined by subtracting the total MFI (shcav, 315; shluc, 489) from the MFI of cells incubated with unlabeled fibronectin (shcav, 147; shluc, 177). Data show the fold change relative to the MFI of endocytosed AF488-fibronectin in control cells, which was set equal to 1 (mean±range).

(H-J) Colocalization of internalized fibronectin with lipid raft marker. FN-null MFs were incubated with 10 μg/mL TR-fibronectin and 2 μg/mL AF488-CTxB at 4°C for 1 hour. After 2 hours of chase, cell were incubated with 0.2% trypan blue for 3 minutes and then processed for imaging assay (H, TR-fibronectin; I, AF488-CTxB; J, overlay image, arrowheads point to colocalized TR-fibronectin and AF488-CTxB).

(K-O) Colocalization of internalized fibronectin, β1 integrins and caveolin-1. FN-null MFs were incubated with 10 μg/mL TR-fibronectin overnight. Cells were washed and then incubated for 12 hours in cell culture media lacking fibronectin, but containing 50 μM chloroquine. Cells were stained with anti-β1 integrin and anti-caveolin-1 antibodies, followed by FITC-conjugated anti-hamster and Alexa Fluor 660-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies. (K, TR-fibronectin; L, β1 integrin; M, caveolin-1; N, overlay image, arrowheads show the white staining that indicates the colocalization of triple colors). Fluorescence intensity profiles (O) were generated using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). A line was manually drawn to cross several TR-fibronectin containing vesicles (as shown in K) and the fluorescence intensity profiles were obtained from each individual color channel. The plot in O was generated in Excel (Microsoft, Seattle) (red, TR-Fibronectin; green, β1 integrin; blue, caveolin-1). All images are optical sections collected from a confocal microscope. Scale bar, 10μm.

To further characterize the intracellular vesicles that contain fibronectin, we asked whether internalized fibronectin is found in lipid raft enriched compartments. FN-null MFs were incubated at 4°C with TR-fibronectin and AF488-conjugated cholera toxin subunit B (CTxB), a caveolae/lipid raft marker, and a short-term endocytosis pulse-chase assay was preformed. TR-fibronectin (Fig. 9H) was found in AF488-CTxB positive compartments (Fig. 9I) following 2 hours of chase (Fig. 9J, arrowheads point to yellow staining). Further, internalized fibronectin, β1 integrins and caveolin-1 all extensively colocalized, as shown by the white staining in the overlay image of Fig. 9N (arrowheads), as well as by the substantial overlap among the fluorescence intensity plots of the three color staining (Fig. 9O).

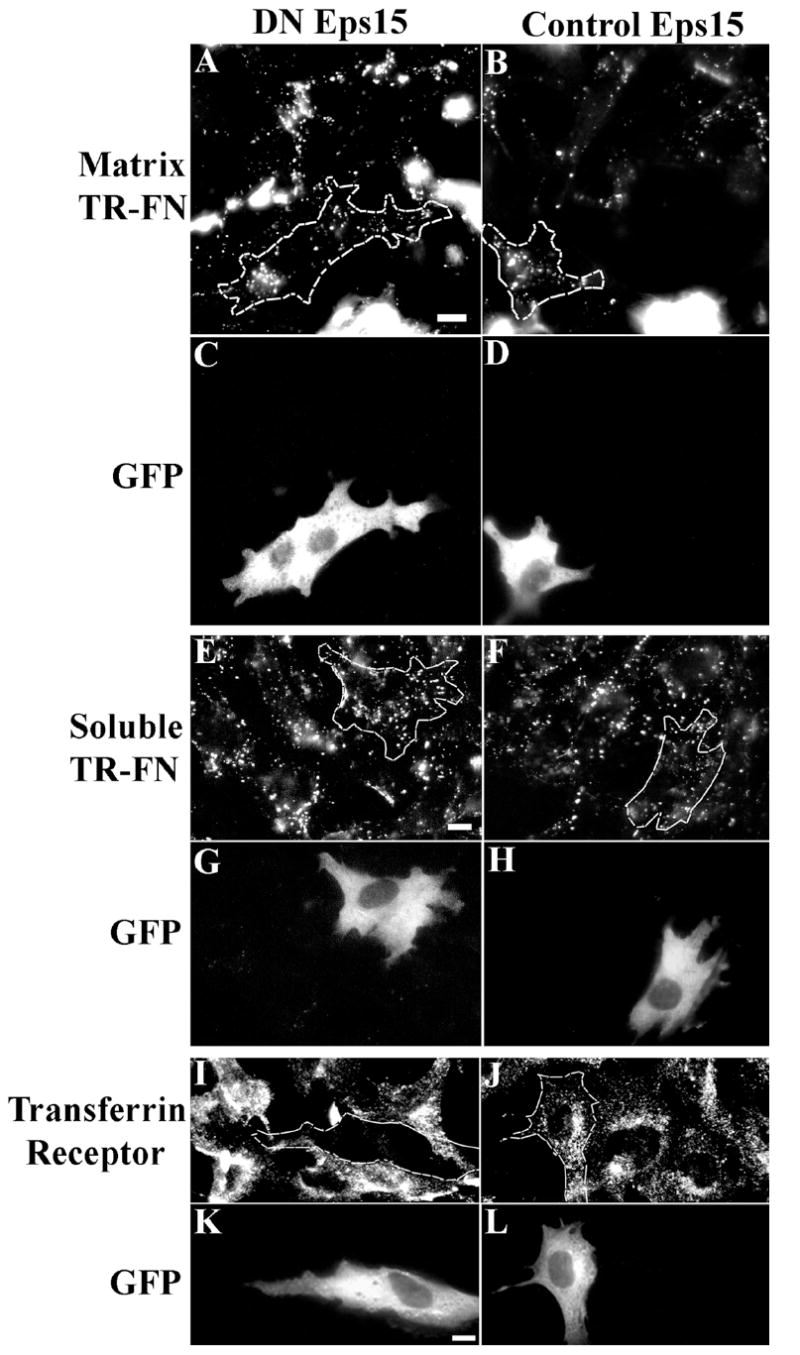

To directly address whether fibronectin endocytosis occurs via a clathrin or non-clathrin mediated pathway, a dominant negative Eps15 mutant (DN Eps15) (Benmerah et al., 1999) was transiently expressed in FN-null MFs. Cells expressing DN Eps15 (Fig. 10A) endocytosed fibronectin from pre-assembled matrix at levels similar to control cells. In contrast, DN Eps15 effectively inhibited endocytosis of the transferrin receptor (Fig. 10I), which is known to be endocytosed by a clathrin-mediated pathway (Harding et al., 1983). DN Eps15 also failed to inhibit soluble fibronectin endocytosis (Fig. 10E). These data demonstrate that fibronectin endocytosis occurs via a non-clathrin mediated pathway.

Figure 10. Dominant negative (DN) Eps15 does not inhibit fibronectin endocytosis.

DN Eps15 (A, C, E, G, I, K) or control Eps15 (B, D, F, H, J, L) were transiently expressed in FN-null MFs as described in Methods. (A-D) Transfected cells were seeded onto pre-assembled matrices and incubated for 24 h. Endocytosed fibronectin is shown in (A, B). (E-H) Short-term pulse chase experiments were performed with transfected cells. (E, F) show endocytosed fibronectin following 2 hr of chase. (I-L) The effect of DN and control Eps15 on transferrin receptor endocytosis is shown. Transfected cells were detected by GFP expression (C, D, G, H, K, L) and manually outlined. 15-20 cells were analyzed for each condition; representative images are shown. Scale bar, 10μm.

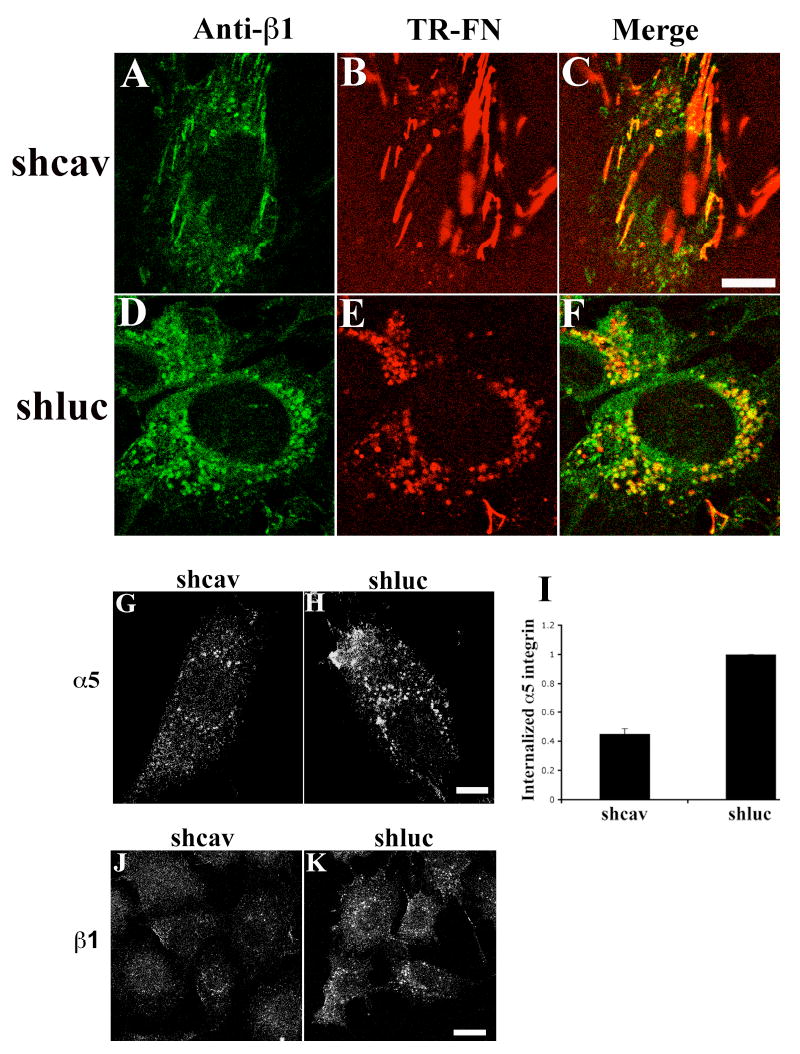

Down-regulation of caveolin-1 reduces both fibronectin and β1 integrin endocytosis

β1 integrins play a major role in mediating fibronectin endocytosis (Fig. 5, 6 and 7). Thus, we asked whether β1 integrin endocytosis is also caveolin-1 dependent. We performed a long-term fibronectin matrix turnover pulse chase assay in cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav) and control cells (shluc). The level of intracellular β1 integrins was dramatically reduced in shcav cells compared with control cells (Fig. 11A-F). To ensure that the intracellular β1 integrins detected in Fig. 11D are internalized from the cell surface, we labeled cell surface β1 integrins with 9EG7 antibody. Internalized 9EG7 was extensively colocalized with internalized fibronectin in control cells (shluc, Fig. S2F). However, there was a dramatic reduction of 9EG7 intracellular accumulation in cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (Fig. S2A) in comparison with control cells (Fig. S2D).

Figure 11. Integrin endocytosis in caveolin-1-knockdown cells.

(A-F) Cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav) or control cells (shluc) were incubated with 10 μg/mL TR-fibronectin overnight. Cells were washed, and then incubated for 8 hours in cell culture media lacking fibronectin, but containing 50 μM chloroquine. Cells were stained with anti-β1 integrin antibody (FITC). Upper panels, shcav; lower panels, shluc. A and D, β1 integrin; B and E, TR-fibronectin; C and F, overlay images. (G-K) Cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav, G,J) or control cells (shluc, H,K) were incubated with 50 μg/mL antibodies to α5 integrin (G-I) or β1 integrin (J, K) at 4°C for 45 minutes. Cells were then processed for integrin endocytosis assay as described in Methods. The fluorescence intensity of endocytosed α5 integrin (G, H) was quantitated using a MATLab based program. (I) Fold change relative to the fluorescence intensity of endocytosed α5 integrin in shluc cells, which was set equal to 1 (mean±range from 2 independent experiments). All images are optical sections collected from a confocal microscope. Scale bar, 10μm.

It is unknown whether endocytosis of β1 integrins is regulated by the same mechanisms in the presence and absence of fibronectin. Cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav) were incubated with α5 integrin antibodies at 4°C in the absence of fibronectin. After washing, cells were chased at 37°C, and the levels of internalized α5 integrin were measured. There was a dramatic decrease in endocytosed α5 integrins in cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (Fig. 11G) compared control cells (Fig. 11H). The levels of endocytosed α5 integrin were reduced 53.2±1.7% when caveolin-1 was down-regulated (Fig. 11I). The levels of endocytosed β1 integrins were also reduced in cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (Fig. 11J) compared with control cells (Fig. 11K).

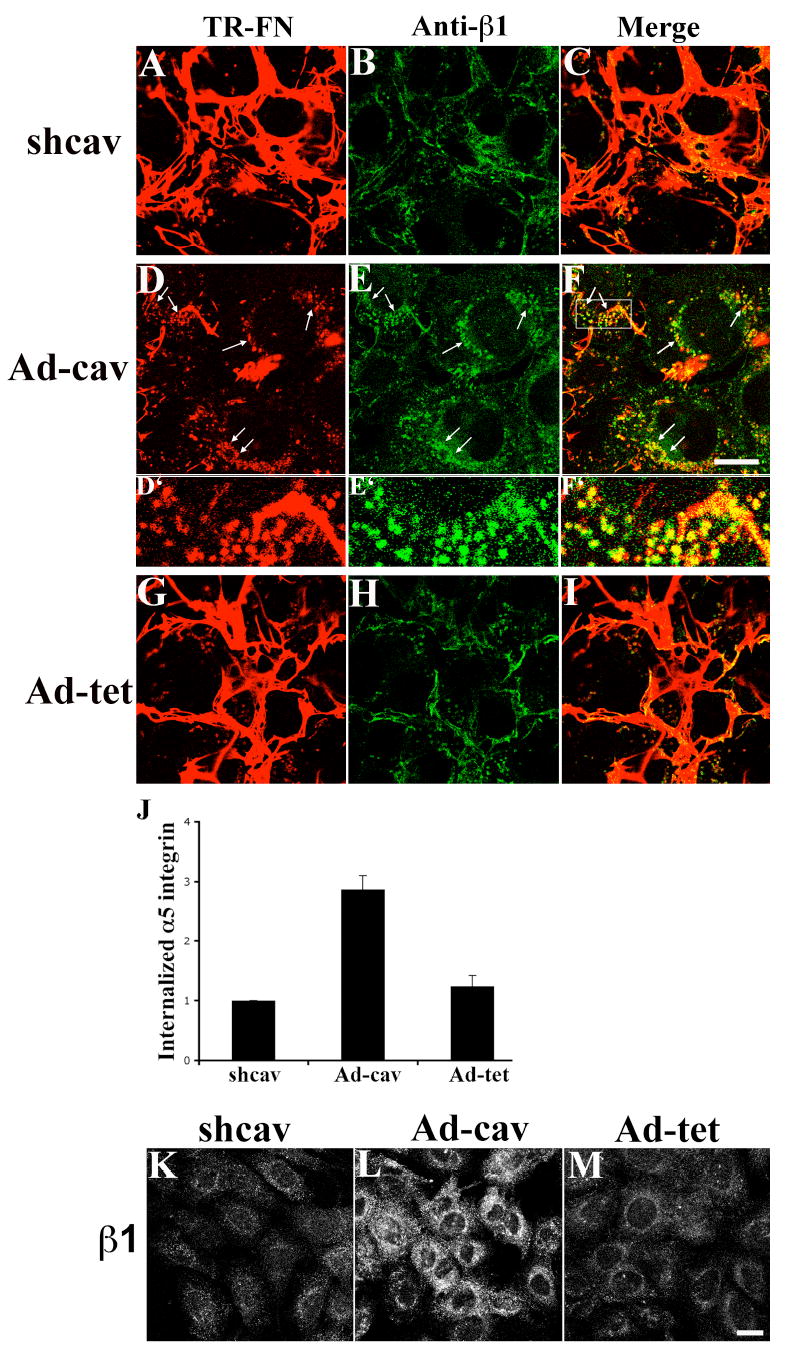

Re-expression of caveolin-1 increases endocytosis of β1 integrins in cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA

To confirm that down-regulation of caveolin-1 in the caveolin-1 siRNA-expressing cells is responsible for decreased endocytosis of β1 integrins (Fig. 11), we re-expressed caveolin-1 in these cells using an adenovirus containing human caveolin-1 (Ad-cav). We performed long-term fibronectin matrix turnover pulse-chase assays with FN-null MFs expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav). Re-expression of caveolin-1 in shcav cells resulted in increased endocytosis of β1 integrins and fibronectin (arrows, Fig. 12D-E). Internalized β1 integrins and fibronectin were colocalized in endocytic vesicles (shown by the yellow staining in the overlay image in Fig. 12F).

Figure 12. Re-expression of caveolin-1 rescues endocytosis of β1 integrin in shcav cells.

FN null MFs expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav) were transduced with Ad-cav or Ad-tet adenoviruses as described in Methods. (A-I) Cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL TR-fibronectin overnight. Cells were washed, and then incubated for 8 hours in cell culture media lacking fibronectin, but containing 50 μM chloroquine. Cells were stained with anti-β1 integrin antibody (FITC). Upper panels, shcav without virus transduction; middle panels, Ad-cav; lower panels, Ad-tet. A, D and G: TR-fibronectin; B, E and H: β1 integrin; C, F and I, overlay images. Arrows in D show the internalized fibronectin; arrows in E show intracellular β1 integrins; arrows in F show colocalized fibronectin and β1 integrins. D’, E’ and F’ are enlarged images of area shown by the rectangle in F.

(J-M) In the absence of fibronectin, cells were incubated with 50 μg/mL antibodies to α5 integrin (J) or β1 integrin (K-M) at 4°C for 45 minutes. Cells were then processed for integrin endocytosis assay as described in Methods. (J) The fluorescence intensity of endocytosed α5 integrin was quantitated using a MATLab based program. Graph in J shows the relative fluorescence intensity of endocytosed α5 integrin in shcav cells with or without virus transduction. Intracellular fluorescence intensity of shcav cells without virus transduction was set equal to 1 (mean±range from 2 independent experiments). All images are optical sections collected from confocal microscope. Scale bar, 20μm.

To determine whether re-expression of caveolin-1 rescues constitutive endocytosis of α5β1 integrin in these cells, we performed integrin endocytosis assays with cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA that were cultured in the absence of fibronectin. As shown in Fig. 12J, re-expression of caveolin-1 increased the levels of endocytosed α5 integrin by 243±15% in compared with cells transduced with control adenovirus (Ad-tet). The endocytosis of β1 integrins was also increased by re-expression of caveolin-1 in shcav cells (Fig. 12L). In contrast, the control adenovirus (Ad-tet) did not rescue constitutive endocytosis of α5β1 integrin (Fig. 12J) or endocytosis of β1 integrins (Fig. 12M). These data show that caveolin-1 regulates endocytosis of β1 integrins, including α5β1 integrin, regardless of the presence or absence of fibronectin and fibronectin matrix.

DISCUSSION

Fibronectin matrix turnover plays a critical role in governing ECM turnover (Sottile and Hocking, 2002). We previously showed that fibronectin matrix turnover occurs through receptor-mediated endocytosis and intracellular degradation (Sottile and Chandler, 2005). In this manuscript, we demonstrate that β1 integrins play an important role in regulating the endocytosis of fibronectin and the turnover of FN matrix fibrils. We also show that caveolin-1 regulates the endocytosis of fibronectin-binding β1 integrins. Furthermore, caveolin-1 constitutively regulates α5β1 integrin endocytosis (Fig. 11), regardless of the presence or absence of fibronectin and fibronectin matrix. Our study also directly shows that α5β1 integrin endocytosis can occur in the absence of its ECM ligand.

Function blocking antibodies to β1 integrin inhibit fibronectin endocytosis both in short-term pulse chase assays, and from pre-assembled fibronectin matrices (Figs. 5, 6), indicating that β1 integrins are functionally important for fibronectin endocytosis. In the short-term assay, most or all of the fibronectin that is present at the start of the chase is cell-associated, protomeric fibronectin. In the long-term pulse chase experiments, ~85% of the fibronectin is incorporated into the matrix at the start of the chase (Sottile and Hocking, 2002). ECM fibronectin is also the predominant (or sole) form present in pre-established matrices. Importantly, our data show that β1 inhibitory antibodies block the endocytosis of “soluble” and matrix fibronectin. Further, β1-null cells show impaired ability to endocytose matrix fibronectin from pre-established matrices. Interestingly, β1-null cells endocytosed soluble fibronectin at levels similar to cells re-expressing β1 integrin (Fig. S1A). These data indicate that other receptors can mediate the endocytosis of soluble fibronectin when β1 integrins are absent, but that this pathway is inefficient when matrix fibronectin is the ligand. Endocytosis of soluble and matrix fibronectin share many features: both are clathrin independent, both are inhibited by downregulation of caveolin-1 (Fig. 9G and (Sottile and Chandler, 2005)), and both colocalize with β1 integrins in intracellular vesicles. It is not known why β1 integrins play a more prominent role in endocytosis of ECM fibronectin than soluble fibronectin (Fig. 7). We speculate that a certain degree of extracellular degradation of fibronectin may occur prior to endocytosis of matrix fibronectin. It has been recently shown that clustering of β1 integrins can induce polarized exocytosis of MT1-MMP to invasive structures, which results in localized ECM degradation (Bravo-Cordero et al., 2007). Thus, it is possible that β1 integrins are involved in two aspects of fibronectin matrix turnover: one involving localized matrix fibronectin degradation, and one involving fibronectin endocytosis.

β1 inhibitory antibodies block fibronectin endocytosis, but do not significantly affect initial fibronectin binding to the cell surface in short-term pulse chases assays. It is possible that the initial cell surface binding and internalization of fibronectin do not rely on the same receptor(s), as has been shown for other matrix proteins (Panetti and McKeown-Longo, 1993). In addition, there are multiple fibronectin binding integrins in FN-null MFs, including αvβ3 (Sottile et al., 1998). Fibronectin can also bind to non-integrin receptors, including proteoglycans (Saunders and Bernfield, 1988; Tumova et al., 2000).

Internalized soluble fibronectin and β1 integrins colocalize at early stages of the endocytosis process (30 minutes, Fig. 2). However, endocytosis of fibronectin from pre-assembled matrices is a slower process, and sufficient intracellular fibronectin does not accumulate at these early times to allow similar colocalization studies to be done. Therefore, it remains uncertain whether β1 integrins can directly internalize fibronectin from the ECM.

Not all fibronectin binding integrins can promote fibronectin endocytosis. Of the integrins tested, only α5β1 integrin was shown to participate in fibronectin endocytosis. Integrin function blocking assays showed that α5 antibodies were not as effective as β1 antibodies in blocking fibronectin endocytosis (Figs. 5 and 8). We speculate that this may be due to the α5 antibodies being less potent inhibitors than β1 antibodies, or to the involvement of multiple α integrin subunits in fibronectin endocytosis. However, to date, we have been unable to identify other α subunits that may participate in fibronectin endocytosis.

Integrin endocytosis has been reported to occur by clathrin and caveolae/lipid-raft-mediated pathways (Caswell and Norman, 2006; Nishimura and Kaibuchi, 2007; Pellinen and Ivaska, 2006). The existence of different pathways and regulatory mechanisms for integrin endocytosis is likely due to the diverse nature of integrin receptors and their ligands. The clearest evidence for the involvement of caveolae/lipid rafts in integrin endocytosis comes from studies of the collagen binding integrin, α2β1, and the leukocyte integrin, αLβ2 (Fabbri et al., 2005; Ning et al., 2007; Upla et al., 2004). Some data also show that β1 integrins can be endocytosed via caveolae upon induction by glycosphingolipids (Sharma et al., 2005). However, direct evidence that fibronectin-binding integrins can be endocytosed by a caveolin-1 dependent pathway has been lacking. The α5β1 integrin is endocytosed and recycled in several cell types (Bretscher, 1992; Pierini et al., 2000). However, the endocytic pathway and regulatory mechanism of α5β1 integrin endocytosis have not been clearly established. In this manuscript, we demonstrate that endocytosis of β1 integrins, including a5β1, is caveolin-1 dependent. In the presence of fibronectin matrix, a large portion of the endocytosed β1 integrins are likely to be ligand (fibronectin)-bound, since internalized β1 integrins are extensively colocalized with endocytosed fibronectin, and because endocytosed β1 integrins are in a ligand-bound conformation, as shown by their ability to bind the 9EG7 antibody (Fig. 1, 2). We further show that disruption of clathrin mediated endocytosis does not inhibit fibronectin endocytosis (Fig. 10). In addition, internalized fibronectin is found in lipid raft compartments (Fig. 9H-J), and internalized fibronectin and β1 integrins extensively colocalize with caveolin-1 positive vesicles (Fig. 9K-O). We previously showed that fibronectin matrix turnover is dependent on protein kinases, cholesterol content, and the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton (Sottile and Chandler, 2005; Sottile and Hocking, 2002). Together these data strongly suggest that the fibronectin endocytosis occurs via a non-clathrin mediated mechanism, and likely involves both integrins and caveolae/lipid rafts.

ECM remodeling is a key regulator of cell migration (Davis and Senger, 2005; Engelholm et al., 2003; Giannelli et al., 1997; Hangai et al., 2002; Hocking and Chang, 2003; Hotary et al., 2000). Our data show that caveolin-1 plays a critical role in fibronectin matrix turnover. Interestingly, caveolin-1 has also been shown to be involved in cell migration (Beardsley et al., 2005; Ge and Pachter, 2004; Grande-Garcia et al., 2007; Navarro et al., 2004). Hence, it is possible that caveolin-1 may regulate cell migration in part, by regulating turnover of matrix fibronectin. Moreover, recent studies from caveolin-1 knockout mice and patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) highlight the importance of caveolin-1 in the development of lung fibrosis (Drab et al., 2001; Park et al., 2002; Razani et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2006). These data suggest the interesting possibility that mice lacking caveolin-1 and/or patients with IPF may also have defects in ECM endocytosis and turnover.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Immunological Reagents and Chemicals

Polyclonal anti-fibronectin antibodies were a generous gift from Dr. Deane Mosher (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI), or were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Antibodies to β1 (Ha2/5, HMβ1-1 and 9EG7), β3 (2C9.G2), α5 (5H10-27) and αv integrin (H9.2B8), caveolin-1 and ERK1/2 were from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA); antibodies to α5 (AB1928), α3 (AB1920) and αv integrin (AB1930) were from Millipore (Billerica, MA). TR and AF488 conjugation kits, AF488-conjugated CTxB, CellTracker green CMFDA, RGD and RGE peptides, and lipofectamine LTX reagent were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Proteins

Human fibronectin was purified as previously described (Miekka et al., 1982). Texas-red (TR) or Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488) conjugated fibronectin was made according to the manufacture’s protocol (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen). Recombinant vitronectin was produced as described (Sottile et al., 2007). Laminin was purchased from BD Biosciences (Bedford, MA), and type I collagen from BD Biosciences or UBI (Lake Placid, NY).

Cell Culture

Fibronectin-null myofibroblasts (FN-null MFs) were cultured as described (Sottile and Hocking, 2002; Sottile et al., 1998). FN-null MFs expressing mouse caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav) and control siRNA (shluc) were described previously (Sottile and Chandler, 2005). Flow cytometry demonstrates that cells expressing caveolin-1 siRNA (shcav) and parental FN-null MFs express very similar cell surface levels of β1, β3, αv and α5 integrins in the absence of fibronectin (data not shown). Rat aortic SMCs were from Cell Applications (San Diego, CA). GD25 cells and GD25 cells re-expressing human β1 integrin were gifts from Dr. Reinhardt Fassler (Max-Planck-Institute for Biochemistry, Martinsried, Germany) (Wennerberg et al., 1996), and Dr. Susan LaFlamme (Albany Medical College, Albany, NY) (Reverte et al., 2006).

For most experiments, cells were plated onto dishes pre-coated with 10 μg/mL vitronectin. To ensure that similar results were obtained with other matrix proteins, some experiments were performed with cells seeded onto dishes coated with 10 μg/mL laminin, 10 μg/mL fibronectin, or 50 μg/mL type I collagen.

Long-term Fibronectin Matrix Turnover Pulse-Chase Assays

FN-null MFs were incubated (“pulsed”) overnight with 10 μg/mL fibronectin. Cells were washed and then incubated (“chased”) with culture medium lacking 10 μg/mL fibronectin at 37°C for various lengths of time. For tracking the internalization of integrins during fibronectin matrix turnover, fibronectin was removed from the media, and cells were then incubated with integrin antibodies at 4°C for 30 minutes to label cell surface integrins. Unbound antibody was removed, and surface-bound antibody was allowed to internalize at 37°C for 3-4 hours in the presence of chloroquine. Internalized antibody was visualized using a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody.

Short-term Fibronectin Endocytosis Pulse-Chase Assays

FN-null MFs were incubated with 10 μg/mL fluorescently labeled fibronectin for 1h at 4°C (pulse phase). For some experiments, FITC-conjugated 9EG7 antibody or Alexa Fluor 488-CTxB was co-incubated with fibronectin during the pulse period. Cells were washed and then incubated with culture medium lacking fibronectin at 37°C (chase phase). For integrin function blocking assays, cells were pre-incubated with integrin inhibitory antibodies at 4°C for 30 minutes as described in the figure legends.

Preparation of Pre-assembled Fibronectin Matrix

The procedure for preparing pre-assembled fibronectin matrix was modified from published protocols (Chen et al., 1978; Mao and Schwarzbauer, 2005). FN-null MFs were incubated overnight with 10μg/mL fibronectin to allow assembly of a robust fibronectin matrix. Cells were washed gently with PBS followed by two washes with wash buffer I (100 mM Na2HPO4, pH 9.6, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA). Cells were incubated with lysis buffer (20mM Na2HPO4, pH 9.6, 1% NP-40) at room temperature for 15 minutes. The lysis buffer was replaced with fresh lysis buffer, and the incubation continued for 30-40 minutes at 37°C. Dishes were gently washed twice with wash buffer II (300 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.5) and 3 times with PBS. Fibronectin matrix was largely preserved after extraction (Fig. S3).

Integrin Endocytosis Assays

To study constitutive integrin endocytosis (in the absence of fibronectin and fibronectin matrix), FN-null MFs grown in defined media were incubated with integrin antibodies at 4°C for 45 minutes. Unbound antibody was removed, and surface-bound antibody was allowed to internalize at 37°C for 30 minutes. Remaining cell surface antibodies were removed by incubating cells in acidic media (pH 4.0) for 6 minutes on ice. Internalized antibody was detected using a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody. To quantitate intracellular fluorescence intensity, z-series confocal images and differential interference contrast images of cells were collected at the same time. A MATLab (Mathworks, Natick, MA) based program was used to trace cell outlines and to quantitate the fluorescence intensity within individual cells. Background fluorescence was determined for each image, and subtracted from the fluorescence intensity of each cell. The fluorescence intensity within individual cells was normalized by cell area. Sample sizes were 46-171 cells for each condition. The mean value of 2 independent experiments (± range) is reported.

Imaging Assays

Immunostaining was performed as described (Sottile and Hocking, 2002). Cells were examined using an Olympus microscope equipped with epifluorescence, or with an Olympus scanning confocal microscope. Protein colocalization was quantitated from confocal images as described previously (Sottile and Chandler, 2005).

Flow Cytometry to Quantitate Endocytosed Fibronectin

After pulse chase assays, cells were incubated with a mixture of 0.02% EDTA, 0.1% trypsin and 200μg/mL proteinase K for 3 minutes at 37°C to remove cell surface fibronectin. Cells were detached from culture dishes and washed with PBS/0.01% azide. Cell were then suspended in 0.2% trypan blue for 2 minutes to quench any residual cell surface fluorescence (Hed, 1977; Van Amersfoort and Van Strijp, 1994). Cells were washed with PBS/0.01% azide and then suspended in 3.5% paraformaldehyde. The intracellular AF488-fibronectin signal was measured immediately by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson).

Western blotting

Cells were scraped from dishes in lysis buffer at the end of the pulse or chase period. Western blotting was performed as described (Sottile and Chandler, 2005). Blots were quantitated using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-COR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE). Levels of ERK on the bots were used as a loading control. The levels of fibronectin were normalized to the levels of ERK. Control experiments were done to determine whether the full-length fibronectin present at the end of the chase is cell surface fibronectin. For these experiments, intact cells were harvested by EDTA, and then treated with trypsin and proteinase K. Western blot analysis showed that all of the full-length fibronectin was extracellular, since it was completely digested by protease treatment (data not shown).

Transient expression of GFP-Eps15 mutant constructs

Dominant negative GFP-Eps15 EH21 and control GFP-Eps15 DIIIΔ2 were generous gifts from Dr. Alexandre Benmerah (INSERM, Paris, France). The EH21 mutant disrupts clathrin-mediated endocytosis; the control construct does not affect endocytosis (Benmerah et al., 1999; Benmerah et al., 1998). Transient expression was performed using lipofectamine LTX reagent according to the manufacture’s instructions. Short-term pulse chase assays were performed on cells 24 hours post transfection. To study fibronectin endocytosis from pre-assembled matrix, cells were harvested 18 hours after transfection, re-seeded on pre-assembled matrix and then cultured for an additional 24 hours. Endocytosis of transferrin receptor was monitored by using antibodies to the transferrin receptor.

Adenoviruses

The Ad-tet adenovirus was a kind gift of Dr. Schmid (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). Preparation and transduction of adenoviruses containing the sequence of either human caveolin-1 (Ad-cav) or tetracycline regulatable transactivator (Ad-tet) were described previously (Sottile and Chandler, 2005). Increased levels of caveolin-1 persisted for >60 hours after viral transduction (data not shown).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Mosher, Dr. Fassler, Dr. Schmid, Dr. Benmerah and Dr. LaFlamme for providing reagents used in this study, Mr. Ken Foxx for developing the MATLab program for image analysis, Dr. Peter Keng and Dr. Timothy Bushnell for advice on flow cytometry, Dr. Keigi Fujiwara and Dr. Liam Casey for their help with image analysis, Dr. Jennifer Bradburn for reading the manuscript, and Andrew Serour and Jennifer Chandler for excellent technical support. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL070261 and GM069729).

Abbreviations

- AF488

Alexa Fluor 488

- CTxB

cholera toxin subunit B

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EDTA

ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid

- FN

fibronectin

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- MF

myofibroblast

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SMC

smooth muscle cell

- TR

Texas Red

References

- Aplin AE, Howe AK, Juliano RL. Cell adhesion molecules, signal transduction and cell growth. Current Opinion Cell Biol. 1999;11:737–744. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoni G, Shih DT, Buck CA, Hemler ME. Monoclonal antibody 9EG7 defines a novel beta 1 integrin epitope induced by soluble ligand and manganese, but inhibited by calcium. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25570–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley A, Fang K, Mertz H, Castranova V, Friend S, Liu J. Loss of caveolin-1 polarity impedes endothelial cell polarization and directional movement. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3541–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmerah A, Lamaze C, Begue B, Schmid SL, Dautry-Varsat A, Cerf-Bensussan N. AP-2/Eps15 interaction is required for receptor-mediated endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1055–1062. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmerah A, Bayrou M, Cerf-Bensussan N, Dautry-Varsat A. Inhibition of clathrin-coated pit assembly by an Eps15 mutant. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1303–11. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.9.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakebusch C, Fassler R. The integrin-actin connection, an eternal love affair. EMBO J. 2003;22:2324–33. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Cordero JJ, Marrero-Diaz R, Megias D, Genis L, Garcia-Grande A, Garcia MA, Arroyo AG, Montoya MC. MT1-MMP proinvasive activity is regulated by a novel Rab8-dependent exocytic pathway. EMBO J. 2007;26:1499–510. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher MS. Endocytosis and recycling of the fibronectin receptor in CHO cells. EMBO J. 1989;8:1341–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher MS. Circulating integrins: alpha 5 beta 1, alpha 6 beta 4 and Mac-1, but not alpha 3 beta 1, alpha 4 beta 1 or LFA-1. EMBO J. 1992;11:405–10. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. Focal adhesion, contractility, and signaling. Annual Review Cell and Developmental Biology. 1996;12:463–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caswell PT, Norman JC. Integrin trafficking and the control of cell migration. Traffic. 2006;7:14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Sottile J, Strickland DK, Mosher DF. Binding and degradation of thrombospondin-1 mediated through heparan sulphate proteoglycans and low-density-lipoprotein receptor-related protein: localization of the functional activity to the trimeric N- terminal heparin-binding region of thrombospondin-1. Biochem J. 1996;318:959–63. doi: 10.1042/bj3180959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LB, Murray A, Segal RA, Bushnell A, Walsh ML. Studies on intercellular LETS glycoprotein matrices. Cell. 1978;14:377–91. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RAF. Wound repair: Overview and general considerations. In: Clark RAF, editor. The molecular and cellular biology of wound repair. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Senger DR. Endothelial extracellular matrix: biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization. Circ Res. 2005;97:1093–107. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000191547.64391.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Duve C, de Barsy T, Poole B, Trouet A, Tulkens P, Van Hoof F. Commentary. Lysosomotropic agents. Biochem Pharmacol. 1974;23:2495–531. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drab M, Verkade P, Elger M, Kasper M, Lohn M, Lauterbach B, Menne J, Lindschau C, Mende F, Luft FC, et al. Loss of caveolae, vascular dysfunction, and pulmonary defects in caveolin-1 gene-disrupted mice. Science. 2001;293:2449–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1062688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelholm LH, List K, Netzel-Arnett S, Cukierman E, Mitola DJ, Aaronson H, Kjoller L, Larsen JK, Yamada KM, Strickland DK, et al. uPARAP/Endo180 is essential for cellular uptake of collagen and promotes fibroblast collagen adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:1009–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri M, Di Meglio S, Gagliani MC, Consonni E, Molteni R, Bender JR, Tacchetti C, Pardi R. Dynamic partitioning into lipid rafts controls the endo-exocytic cycle of the alphaL/beta2 integrin, LFA-1, during leukocyte chemotaxis. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5793–803. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Pachter JS. Caveolin-1 knockdown by small interfering RNA suppresses responses to the chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by human astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6688–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B, Bershadsky A, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix--cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:793–805. doi: 10.1038/35099066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannelli G, Falk-Marzillier J, Schiraldi O, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Quaranta V. Induction of cell migration by matrix metalloprotease-2 cleavage of laminin-5. Science. 1997;277:225–227. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg MH, Partridge A, Shattil SJ. Integrin regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godyna S, Liau G, Popa I, Stefansson S, Argraves WS. Identification of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) as an endocytic receptor for thrombospondin-1. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1403–10. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.5.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande-Garcia A, Echarri A, de Rooij J, Alderson NB, Waterman-Storer CM, Valdivielso JM, Del Pozo MA. Caveolin-1 regulates cell polarization and directional migration through Src kinase and Rho GTPases. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:683–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangai M, Kitaya N, Xu J, Chan CK, Kim JJ, Werb Z, Ryan SJ, Brooks PC. Matrix metalloproteinase-9-dependent exposure of a cryptic migratory control site in collagen is required before retinal angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1429–37. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64418-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding C, Heuser J, Stahl P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:329–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hed J. The extinction of fluorescence by crystal violet and its use to differentiate between attached and ingested microorganisms in phagocytosis. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 1977;1:357–361. [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Chang CH. Fibronectin matrix polymerization regulates small airway epithelial cell migration. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:L169–79. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00371.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck K, Bianco P, Caterina J, Yamada S, Kromer M, Kuznetsov SA, Mankani M, Robey PG, Poole AR, Pidoux I, et al. MT1-MMP-deficient mice develop dwarfism, osteopenia, arthritis, and connective tissue disease due to inadequate collagen turnover. Cell. 1999;99:81–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornebeck W, Emonard H, Monboisse JC, Bellon G. Matrix-directed regulation of pericellular proteolysis and tumor progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:231–41. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotary K, Allen E, Punturieri A, Yana I, Weiss SJ. Regulation of cell invasion and morphogenesis in a three-dimensional type I collagen matrix by membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases 1, 2, and 3. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1309–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.6.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotary KB, Allen ED, Brooks PC, Datta NS, Long MW, Weiss SJ. Membrane type I matrix metalloproteinase usurps tumor growth control imposed by the three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Cell. 2003;114:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe A, Aplin AE, Alahari SK, Juliano RL. Integrin signaling and cell growth control. Current Opinion Cell Biol. 1998;10:220–231. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: Versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson S, Svineng G, Wennerberg K, Armulik A, Lohikangas L. Fibronectin-integrin interactions. Front Biosci. 1997;2:d126–46. doi: 10.2741/a178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G, Prockop DJ. Mutations in collagen genes: causes of rare and some common diseases in humans. FASEB J. 1991;5:2052–60. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.7.2010058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurban G, Hudon V, Duplan E, Ohh M, Pause A. Characterization of a von Hippel Lindau pathway involved in extracellular matrix remodeling, cell invasion, and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1313–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenter M, Uhlig H, Hamann A, Jeno P, Imhof B, Vestweber D. A monoclonal antibody against an activation epitope on mouse integrin chain beta 1 blocks adhesion of lymphocytes to the endothelial integrin alpha 6 beta 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9051–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotta LA, Kohn EC. The microenvironment of the tumour-host interface. Nature. 2001;411:375–9. doi: 10.1038/35077241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Schwarzbauer JE. Stimulatory effects of a three-dimensional microenvironment on cell-mediated fibronectin fibrillogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4427–36. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchina E, Barlati S. Degradation of human plasma and extracellular matrix fibronectin by tissue type plasminogen activator and urokinase. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;28:1141–50. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(96)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown-Longo PJ, Mosher DF. Binding of plasma fibronectin to cell layers of human skin fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:466–472. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown-Longo PJ, Mosher DF. The assembly of fibronectin matrix in cultured human fibroblast cells. In: Mosher DF, editor. Fibronectin. New York: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown-Longo PJ, Panetti TS. Receptor mediated endocytosis of vitronectin by fibroblast monolayers. In: Preissner KT, Rosenblatt S, Kost C, Wegerhoff J, Mosher DF, editors. Biology of vitronectins and their receptors. B.V.: Elsvier Science Publishers; 1993. pp. 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Memmo LM, McKeown-Longo P. The alphavbeta5 integrin functions as an endocytic receptor for vitronectin. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:425–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miekka SI, Ingham KC, Menache D. Rapid methods for isolation of human plasma fibronectin. Thromb Res. 1982;27:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(82)90272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich JE, Mosher DF. Interactions of thrombospondin with endothelial cells: receptor- mediated binding and degradation. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:1603–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.4.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutsaers SE, Bishop JE, McGrouther G, Laurent GJ. Mechanisms of tissue repair: from wound healing to fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:5–17. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A, Anand-Apte B, Parat MO. A role for caveolae in cell migration. FASEB J. 2004;18:1801–11. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2516rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Y, Buranda T, Hudson LG. Activated EGF receptor induces integrin alpha 2 internalization via caveolae/raft-dependent endocytic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6380–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Kaibuchi K. Numb controls integrin endocytosis for directional cell migration with aPKC and PAR-3. Dev Cell. 2007;13:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly MS, Boehm T, Shing Y, Fukai N, Vasios G, Lane WS, Flynn E, Birkhead JR, Olsen BR, Folkman J. Endostatin: An endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell. 1997;88:277–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panetti TS, McKeown-Longo PJ. The alpha v beta 5 integrin receptor regulates receptor-mediated endocytosis of vitronectin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11492–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DS, Woodman SE, Schubert W, Cohen AW, Frank PG, Chandra M, Shirani J, Razani B, Tang B, Jelicks LA, et al. Caveolin-1/3 double-knockout mice are viable, but lack both muscle and non-muscle caveolae, and develop a severe cardiomyopathic phenotype. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:2207–17. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61168-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellinen T, Ivaska J. Integrin traffic. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3723–31. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierini LM, Lawson MA, Eddy RJ, Hendey B, Maxfield FR. Oriented endocytic recycling of alpha5beta1 in motile neutrophils. Blood. 2000;95:2471–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijuan-Thompson V, Gladson CL. Ligation of integrin alpha5beta1 is required for internalization of vitronectin by integrin alphavbeta3. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2736–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plow EF, Haas TA, Zhang L, Loftus J, Smith JW. Ligand binding to integrins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21785–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole AR, Nelson F, Dahlberg L, Tchetina E, Kobayashi M, Yasuda T, Laverty S, Squires G, Kojima T, Wu W, et al. Proteolysis of the collagen fibril in osteoarthritis. Biochem Soc Symp. 2003:115–23. doi: 10.1042/bss0700115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proux-Gillardeaux V, Gavard J, Irinopoulou T, Mege RM, Galli T. Tetanus neurotoxin-mediated cleavage of cellubrevin impairs epithelial cell migration and integrin-dependent cell adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6362–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409613102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razani B, Engelman JA, Wang XB, Schubert W, Zhang XL, Marks CB, Macaluso F, Russell RG, Li M, Pestell RG, et al. Caveolin-1 null mice are viable but show evidence of hyperproliferative and vascular abnormalities. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38121–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reverte CG, Benware A, Jones CW, LaFlamme SE. Perturbing integrin function inhibits microtubule growth from centrosomes, spindle assembly, and cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:491–7. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M, Barry S, Woods A, van der Sluijs P, Norman J. PDGF-regulated rab4-dependent recycling of alphavbeta3 integrin from early endosomes is necessary for cell adhesion and spreading. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1392–402. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeh F, Ota I, Holmbeck K, Birkedal-Hansen H, Soloway P, Balbin M, Lopez-Otin C, Shapiro S, Inada M, Krane S, et al. Tumor cell traffic through the extracellular matrix is controlled by the membrane-anchored collagenase MT1-MMP. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:769–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Fassler R, Hohenester E. Laminin: the crux of basement membrane assembly. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:959–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Larsson H, Tisi D, Claesson-Welsh L, Hohenester E, Timpl R. Endostatins derived from collagens XV and XVIII differ in structural and binding properties, tissue distribution and anti-angiogenic activity. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:1179–90. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders S, Bernfield M. Cell surface proteoglycan binds mouse mammary epithelial cells to fibronectin and behaves as a receptor for interstitial matrix. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:423–430. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.2.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbauer JE, Sechler JL. Fibronectin fibrillogenesis: a paradigm for extracellular matrix assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:622–7. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sczekan MM, Juliano RL. Internalization of the fibronectin receptor is a constitutive process. J Cell Physiol. 1990;142:574–80. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041420317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SD. Matrix metalloproteinase degradation of extracellular matrix: biological consequences. Current Opinion Cell Biol. 1998;10:602–608. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma DK, Brown JC, Cheng Z, Holicky EL, Marks DL, Pagano RE. The glycosphingolipid, lactosylceramide, regulates beta1-integrin clustering and endocytosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8233–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottile J, Chandler J. Fibronectin matrix turnover occurs through a caveolin-1-dependent process. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:757–68. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottile J, Hocking DC. Fibronectin polymerization regulates the composition and stability of extracellular matrix fibrils and cell-matrix adhesions. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3546–3559. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottile J, Hocking DC, Swiatek P. Fibronectin matrix assembly enhances adhesion-dependent cell growth. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2933–2943. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.19.2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottile J, Shi F, Rublyevska I, Chiang HY, Lust J, Chandler J. Fibronectin-dependent collagen I deposition modulates the cell response to fibronectin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1934–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00130.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumova S, Woods A, Couchman JR. Heparan sulfate chains from glypican and syndecans bind the Hep II domain of fibronectin similarly despite minor structural differences. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9410–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upla P, Marjomaki V, Kankaanpaa P, Ivaska J, Hyypia T, Van Der Goot FG, Heino J. Clustering induces a lateral redistribution of alpha 2 beta 1 integrin from membrane rafts to caveolae and subsequent protein kinase C-dependent internalization. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:625–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Amersfoort ES, Van Strijp JA. Evaluation of a flow cytometric fluorescence quenching assay of phagocytosis of sensitized sheep erythrocytes by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Cytometry. 1994;17:294–301. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990170404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Rest M, Garrone R. Collagen family of proteins. FASEB J. 1991;5:2814–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu TH, Shipley JM, Bergers G, Berger JE, Helms JA, Hanahan D, Shapiro SD, Senior RM, Werb Z. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XM, Zhang Y, Kim HP, Zhou Z, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Liu F, Ifedigbo E, Xu X, Oury TD, Kaminski N, et al. Caveolin-1: a critical regulator of lung fibrosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2895–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennerberg K, Lohikangas L, Gullberg D, Pfaff M, Johansson S, Fassler R. B1 integrin-dependent and -independent polymerization of fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:227–238. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienke D, MacFadyen JR, Isacke CM. Identification and characterization of the endocytic transmembrane glycoprotein Endo180 as a novel collagen receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3592–604. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Rodriguez D, Petitclerc E, Kim JJ, Hangai M, Yuen SM, Davis GE, Brooks PC. Proteolytic exposure of a cryptic site within collagen type IV is required for angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:1069–79. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.