Abstract

Background

Chronic abuse of methamphetamine produces deficits in hippocampal function, perhaps by altering hippocampal neurogenesis and plasticity. We examined how intravenous methamphetamine self-administration modulates active division, proliferation of late progenitors, differentiation, maturation, survival, and mature phenotype of hippocampal subgranular zone (SGZ) progenitors.

Methods

Adult male Wistar rats were given access to methamphetamine 1 h twice weekly (intermittent short), 1 h daily (short), or 6 h daily (long). Rats received one intraperitoneal injection of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) to label progenitors in the synthesis (S) phase, and 28-day-old surviving BrdU-immunoreactive (IR) cells were quantified. Ki-67, doublecortin (DCX), and activated caspase-3 (AC-3) were used to visualize and quantify proliferating, differentiating, maturing, and apoptotic cells. Terminal corticosterone was measured to determine changes in adrenal steroids.

Results

Intermittent access to methamphetamine increased Ki-67 and DCX-IR cells, but opposing effects on late progenitors and postmitotic neurons resulted in no overall change in neurogenesis. Daily access to methamphetamine decreased all studied aspects of neurogenesis and reduced hippocampal granule neurons and volume, changes that likely are mediated by decreased proliferative and neurogenic capacity of the SGZ. Furthermore, methamphetamine self-administration relative to the amount of methamphetamine intake produced a biphasic effect on hippocampal apoptosis and reduced corticosterone levels.

Conclusions

Intermittent (occasional access) and daily (limited and extended access) self-administration of methamphetamine impact different aspects of neurogenesis, the former producing initial pro-proliferative effects and the latter producing downregulating effects. These findings suggest that altered hippocampal integrity by even modest doses of methamphetamine could account for pronounced pathology linked to methamphetamine abuse.

Keywords: subgranular zone, psychostimulant, extended access, Ki-67, doublecortin, bromodeoxyuridine

Introduction

Abuse of the psychostimulant methamphetamine has reached epidemic proportions and poses significant medical and social problems in the United States [1]. Methamphetamine abuse in humans severely damages the hippocampus, reducing hippocampal volume and producing hippocampal-dependent memory deficits [2], but the mechanism for these deleterious effects is unknown. Adult neurogenesis—the birth and survival of neural progenitors—and the persistence of the entire process of neuronal development in adulthood have been demonstrated in the hippocampal subgranular zone (SGZ) [3]. Hippocampal progenitors mature into neurons or glia and are implicated in maintaining adult brain structure and function [4–6]. A large proportion of SGZ progenitors become functional dentate gyrus granule cell neurons [6–12]. Recent advances in immunohistochemical methods have demonstrated that a number of external factors, including drugs of abuse, regulate the birth, survival, and fate of newly born SGZ progenitors [13]. Thus, while the devastating effects of methamphetamine on the structure and function of the hippocampus are clear, little information exists on the impact of intravenously self-administered methamphetamine on adult hippocampal neurogenesis.

The hippocampus is involved in the important relapse stage of psychostimulant abuse. For example, the hippocampus is implicated in forming context-specific memories associated with reinstatement of drug-seeking [14–16]. Such context-specific memories may be hypothesized to involve neurogenic mechanisms [17]. Thus, it is critical to determine if and how new SGZ neurons are affected by methamphetamine. Such research may provide novel clinical approaches to treatment of psychostimulant dependence and relapse to drug-seeking.

Drugs of abuse, in general, have been shown to decrease adult hippocampal neurogenesis [18–22]. Such modest volume of descriptive research demonstrates that most drugs of abuse negatively impact the self-renewal capacity of the adult hippocampus, therefore suggesting a potential role of adult neurogenesis in addiction. However, little work has been done with a validated model of intravenous drug self-administration relevant to the transition to addiction. In addition, the fundamental mechanisms contributing to drug-induced decreases in neurogenesis in the adult mammalian hippocampus are unclear [23–25]. Furthermore, the use of different markers of differentiation and maturation to determine drug-induced alterations in the transition and different stages of morphological and functional development of adult generated hippocampal neurons is lacking. Importantly, use of a forced (experimenter-delivered) drug administration paradigm to uncover chronic drug-induced alterations in hippocampal plasticity has limited relevance to clinical situations. Therefore, the use of a clinically relevant model of drug self-administration to study drug-induced alterations in hippocampal neurogenesis has significant merit.

To this end, we allowed rats to self-administer methamphetamine daily or twice weekly to determine the chronic effects of this psychostimulant on adult hippocampal neurogenesis, hippocampal apoptosis, hippocampal volume, and terminal corticosterone levels. We hypothesized that higher levels of methamphetamine self-administration would alter all stages of hippocampal neural progenitors to produce changes in neurogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we quantified proliferating, differentiating, maturing, and surviving hippocampal progenitors in adult rats that were allowed intermittent or daily access to methamphetamine.

Methods

Animals, BrdU injections, and tissue preparation

Adult, male Wistar rats (Charles River), weighing 250–300 g at the start of the experiment, were housed two per cage in a temperature-controlled vivarium under a reversed light/dark cycle (lights off 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m.). Food and water were available ad libitum, except during the food training period. Rats were subjected to methamphetamine self-administration [6 h long access (LgA group; n = 6), 1 h short access (ShA group; n = 9), or 1 h intermittent short access (I-ShA; n = 6, exposed to methamphetamine on Mondays and Thursdays of each week)] and were 24–26 weeks old when perfused (a complete description of methamphetamine self-administration is provided in supplementary material). All procedures were performed during the dark phase. During the study, all rats received one injection of 150 mg/kg BrdU, i.p. (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemica), dissolved in 0.9% saline and 0.007N NaOH at 20 mg/ml and survived for 28 days after which they were anesthetized with chloral hydrate and perfused transcardially as described previously [23]. Serial coronal 40 μm sections were obtained on a freezing microtome, and sections from the medial prefrontal cortex (bregma 3.7 to 2.2) and hippocampus (bregma −1.4 to −6.7) [26] were stored in 0.1% NaN3 in 1× PBS at 4°C. Data on the medial prefrontal cortex from the same rats have been published elsewhere [27]. Tissue from the hippocampus was stored and analyzed separately for the present study. Surgical and experimental procedures were carried out in strict adherence to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication number 85–23, revised 1996) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Scripps Research Institute.

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used for immunohistochemistry. Rabbit monoclonal anti-Ki-67 (1:1000), mouse anti-BrdU (1:100), rat monoclonal anti-BrdU (1:100), goat polyclonal anti-doublecortin (DCX) (1:700), rabbit polyclonal anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (1:500), mouse monoclonal anti-neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN) (1:50), and rabbit polyclonal anti-activated caspase 3 (AC-3) (1:500).

Immunohistochemistry, microscopic analysis and quantification

The left and right hemispheres of every ninth section through the rat brain hippocampus were slide-mounted, coded, and dried overnight prior to immunohistochemistry. Sections were pretreated [23], blocked, and incubated with the primary antibodies followed by biotin-tagged or fluorescent secondary antibodies (a complete description of immunohistochemical methods is provided in supplementary material).

Microscopic analysis and quantification

SGZ cells (cells touching and within three cell widths inside and outside the hippocampal granule cell-hilus border) were quantified with a Zeiss Axiophot photomicroscope (400× magnification) using the optical fractionator method in which every ninth section through the SGZ (bregma −1.4 to −6.7) was examined [26]. Cells in the SGZ from each bregma were summed and multiplied by nine to give the total number of cells [18] (For details on preliminary DCX analysis, detailed DCX analysis, DCX and BrdU phenotype analysis see immunohistochemistry, microscopic analysis and quantification sections in supplementary material).

Stereology

Stereological assessment of hippocampal, dentate gyrus, and granule cell volume

Bilateral volume measurements were determined in the sections previously used to measure apoptosis. Volumes were estimated based on surface area measurements made from coronal brain sections [28, 29]. All measurements were obtained using a Zeiss Axiophot Microscope equipped with MicroBrightField Stereo Investigator software (MicroBrightField), a three-axis Mac 5000 motorized stage (Ludl Electronics Products), a Zeiss digital charge-coupled device ZVS video camera, PCI color frame grabber, and computer workstation.

Measurement of granule cell number

The average density of granule cells was found by examining eight sections (1/18 section analysis) from each rat from all portions of the granule cell layer. Live video images were used to draw contours delineating the granule cell layer. All contours were drawn at low magnification (Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 100×, numerical aperture 0.32), and the contours were realigned at high magnification (630× oil objective, numerical aperture 1.4). Following determination of mounted section thickness (cut section thickness 40 μm; measured mounted section thickness 11–15 μm), z plane values and selection of contours, an optical fractionator analysis was used to determine bilateral estimates of granule cell neuron number per granule cell layer of each dentate. The total number of granule cells was calculated by an unbiased stereological estimation, where the average density of the granule cells (cells/μm3) was multiplied by total volume of the granule cell layer of the hippocampal dentate gyrus [30, 31] (For details on volume analysis and measurement of granule cell neurons see stereology section in supplementary material).

Plasma corticosterone

Analysis was performed by sampling blood from cardiac punctures taken immediately after anesthesia (chloral hydrate) and just prior to intracardial perfusions. Corticosterone levels were determined using a commercially available radioimmunoassay kit (MP Biomedicals, Inc.).

Data analysis

Ki-67 and DCX data were analyzed using non-matching two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with methamphetamine access and technical aspects of cell markers as variables using GraphPad Prism 5.0. Analysis of phenotypes also was done using non-matching two-way ANOVA, with methamphetamine access and DCX or BrdU cell phenotype as variables. All analyses were followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests with three comparisons. Methamphetamine access, BrdU, AC-3, granule cell layer and volume analysis, and corticosterone data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s (control vs. methamphetamine groups) or Tukey’s (between methamphetamine groups) post hoc tests. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Images presented here were collected on a Zeiss Axiophot photomicroscope with a Zeiss ZVS video camera and imported into Photoshop (version CS2). Only the gamma adjustment in the Levels function was used.

Results

Methamphetamine self-administration alters proliferation, maturation, and survival of hippocampal precursors

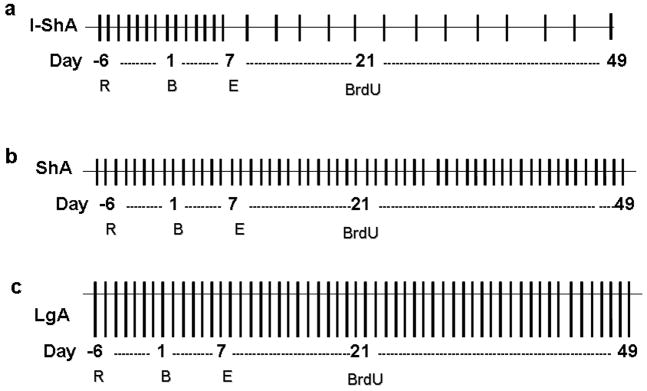

Intermittent and daily access models of intravenous methamphetamine self-administration were used to investigate methamphetamine-induced alterations in adult hippocampal neurogenesis (Fig 1a–c). Total methamphetamine intake was significantly different in each access group (intake over 49 days: I-ShA, 7.8±0.01 mg/kg; ShA, 20.6±0.03 mg/kg; LgA, 128.7±0.44 mg/kg; F(2,20)=84960, p<0.0001), and methamphetamine self-administration during the first hour was considerably higher in LgA vs. ShA and I-ShA rats (first hour intake during the last session on day 49: I-ShA, 0.37±0.07 mg/kg/infusion; ShA, 1.3±0.16 mg/kg/infusion; LgA, 2.1±0.22 mg/kg/infusion; F(2,20)=22.4, p<0.0001; reported in [27].

Figure 1. Time-line of methamphetamine self-administration.

(a–c) schematic of the time-line of methamphetamine self-administration: intermittent short access (I-ShA) (a), short access (ShA) (b), and long access (LgA) (c). Each vertical line in a–c represents one day, with length corresponding to duration of access. R, recovery from surgery followed by food training; B, baseline; E, escalation; BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine injection.

Hippocampal sections from the drug-naive control, I-ShA, ShA, and LgA groups were processed and examined for changes in proliferation (Ki-67-IR), differentiation and maturation (DCX-IR), and survival (BrdU-IR).

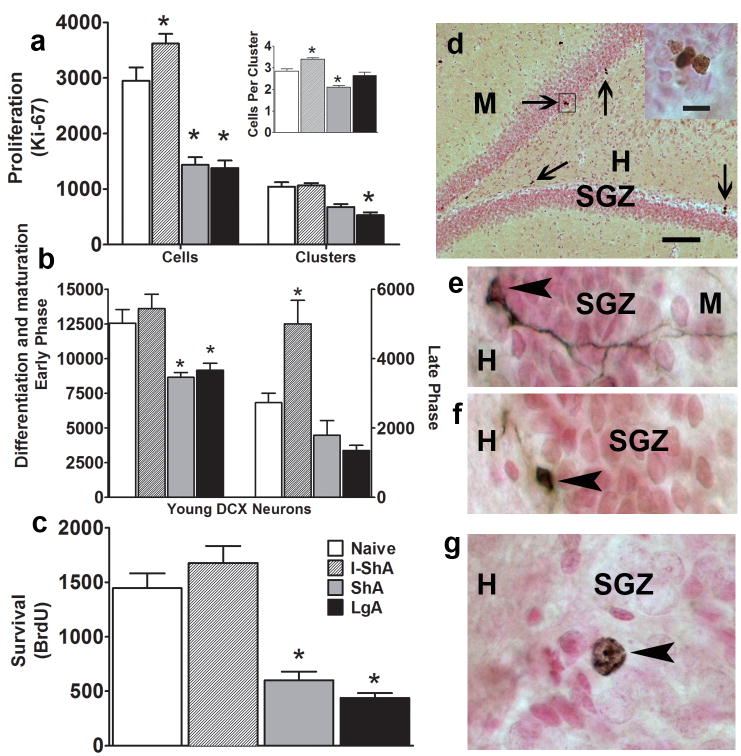

Proliferation

The SGZ gives birth to a heterogeneous population of putative progenitors, and Ki-67 (an endogenous marker specific for actively dividing progenitors; [32]) labels a large subset of SGZ proliferative progenitors (types 2a/2b/3; nomenclature from [33]). Because proliferation of cells occurs in clusters in the SGZ [34, 35], key technical details such as number of cells, clusters, and cells per cluster also were quantified. Methamphetamine self-administration significantly altered SGZ proliferation (effect of methamphetamine: F(3,78)=32.49, p<0.0001) (Fig. 2a), with a significant interaction between methamphetamine intake and kinetics of proliferation [Ki-67 cells, clusters, cells per cluster: F(6,78)=17.36, p<0.0001]. The I-ShA rats had substantially increased Ki-67-IR cells [F(3,78)=295.9, p<0.01)] (Fig. 2a) and cells per cluster [F(3,78)=295.9, p<0.05] (Fig. 2a inset) compared with control and daily access rats but did not alter the number of clusters in the SGZ. ShA and LgA rats had decreased Ki-67-IR cells [ShA, LgA: F(3,78)=295.9, p<0.001] (Fig 2a), clusters (LgA: F(3,78)=295.9, p<0.01] (Fig 2a), and cells per cluster [ShA: F(3,78)=295.9, p<0.05] (Fig 2a inset) in the SGZ compared with controls.

Figure 2. Methamphetamine self-administration alters proliferation, differentiation/maturation, and survival.

(a–c) Quantitative analysis of cell counts of (a) active proliferation [Ki-67-IR cells, clusters, and cells per cluster (inset)], (b) differentiation/maturation (DCX-IR cells, early and late phase), and (c) survival (BrdU-IR cells). (d–g) Brightfield images of (d) Ki-67 [main panel shows low magnification hippocampal dentate gyrus with arrows pointing to Ki-67-IR clusters; one cluster (enclosed by open square) is magnified to indicate multiple cells in each cluster; SGZ-subgranular zone, H-hilus, M-molecular layer], (e) late phase DCX-IR cell (arrowhead points to cell body; processes extend perpendicular, deep into the molecular layer), (f) early phase DCX-IR cell (arrowhead points to cell body; processes extend parallel to SGZ), and (g) 28-day-old BrdU-IR cell. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 6–11 in each group, (*) p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA in a and b, one-way ANOVA in c. Scale bar in d = 100 μm. Scale bar in d inset = 10 μm and applies to e–g.

Differentiation and Maturation

DCX-IR cells (Fig. 2e, f) were quantified to assess changes in late progenitors (early phase) and postmitotic neurons (late phase). Unlike that seen with proliferation, there was no interaction between methamphetamine intake and DCX-IR cells. The I-ShA rats did not have altered early-phase DCX-IR cell counts but had increased late-phase DCX-IR cell count compared with controls [F(3,26)=17.86, p<0.05] (Fig. 2b). The ShA and LgA rats significantly decreased early-phase DCX-IR cell counts compared with control and I-ShA rats [early phase: F(3,26)=17.86, p<0.001] (Fig. 2b).

Survival

BrdU immunohistochemistry was performed to quantify 28-day-old BrdU-IR cells (Fig. 2c, g), a measure of precursor cell survival [36]. Unlike the changes observed with proliferation and maturation, the I-ShA rats did not alter the number of mature BrdU cells compared with controls (Fig. 2c). As expected and parallel to the observed changes in cell proliferation and maturation, the ShA and LgA rats had significantly decreased BrdU cell counts compared with controls [F(3,17)=15.8, p<0.001] (Fig. 2c).

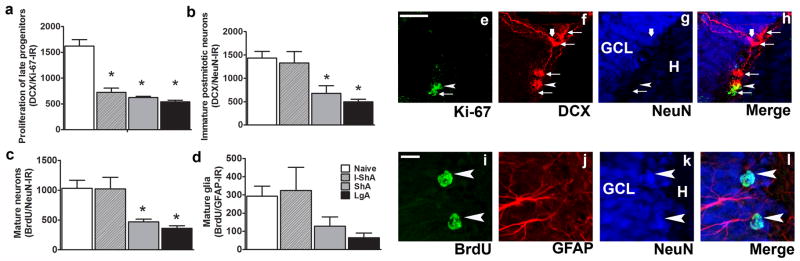

Methamphetamine self-administration alters proliferation of late progenitors, immature postmitotic and mature neurons, and mature glia

Hippocampal sections from the drug-naive control, I-ShA, ShA, and LgA groups were processed and examined for changes in proliferation of late progenitors (Ki-67/DCX), immature postmitotic neurons (DCX/NeuN), mature neurons (BrdU/NeuN), and mature glia (BrdU/GFAP).

Proliferation of late progenitors

The proportion of early phase DCX-IR cells double-labeled with Ki-67 (alternate nomenclatures – ‘immature DCX-IR transiently amplifying neuroblasts type I proliferating’ [37] and ‘type 2b/3’ [33]) was evaluated and expressed as proliferation of late progenitors. In naive controls, 1619±126 (12±2.4%) early-phase DCX-IR cells double-labeled with Ki-67, indicating that a very small population of early-phase DCX-IR cells were actively dividing. The data support the hypothesis that DCX expression represents a mixed stage of differentiation and maturation of young neurons [37–39]. Analysis of early-phase DCX-IR cells from the I-ShA, ShA, and LgA rats revealed significant changes in the phenotypic ratio, where methamphetamine self-administration in all groups decreased proliferation of late progenitors [total number of DCX/Ki-67-IR cells: I-ShA, 724±79; ShA, 623±24; LgA, 540±29; F(3,27)=29.08, p=0.0001] (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Methamphetamine self-administration alters proliferation of late progenitors and generation of immature postmitotic neurons, mature neurons, and mature glia.

(a–d) Quantitative data of (a) proliferation of late progenitors DCX/Ki-67-IR (alternate nomenclatures – ‘immature DCX-IR transiently amplifying neuroblasts type I proliferating’ [37] and ‘type 2b/3’ [33], (b) immature postmitotic neurons DCX/NeuN-IR, (c) mature neurons BrdU/NeuN-IR, and (d) mature glia BrdU/GFAP-IR. Single z plane images of DCX- or BrdU-labeled cells in the SGZ from one control rat. (e–h) Single z scan (0.5 μm) of a confocal z stack of DCX-IR cells in red (CY3), Ki-67-IR in green (FITC), and NeuN-IR in blue (CY5). Arrowhead in e–h points to a double-labeled Ki-67-positive/early phase DCX-positive cell. Arrows in e–h point to single-labeled cells: Ki-67-positive/DCX-ve cell or DCX-positive/Ki-67/NeuN-ve cells. Thick arrow in f–h points to a double-labeled DCX-positive/NeuN-positive cell. (i–l) Single z scan (0.5 μm) of a confocal z stack of BrdU-IR cells in green (FITC), GFAP-IR cells in red (CY3), and NeuN-IR cells in blue (CY5). Arrowhead in i–l points to a double-labeled BrdU-positive/NeuN-positive cell. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 4–6 in each group, (*) p < 0.05 compared with control. Scale bar in e = 25 μm and applies to e–h. Scale bar in i = 10μm and applies to i–l.

Immature postmitotic neurons

The proportion of late-phase DCX-IR cells double-labeled with NeuN was evaluated and expressed as immature postmitotic neurons. In naive controls, 1432±143 (65±6%) late-phase DCX-IR cells double-labeled with NeuN, indicating that most late-phase DCX-IR cells attained a neuronal phenotype. Phenotypic analysis of late-phase DCX-IR cells from the I-ShA, ShA, and LgA rats demonstrated that methamphetamine self-administration only in ShA and LgA rats showed decreased maturation of immature postmitotic neurons [DCX/NeuN-IR cells: I-ShA, 1330±240; ShA, 678±160; LgA, 498±55; F(3,25)=6.03, p=0.007] (Fig. 3b).

Mature neurons and glia

Four weeks after BrdU injection, BrdU-IR cells from all groups were triple-labeled with NeuN (neurons) and GFAP (astrocytes). The percentage of BrdU-IR cells double-labeled with neurons vs. astrocytes was determined. Overall, 1031±135 (69.5±5.1%) BrdU-IR cells colocalized with NeuN, and 292±55 (21.8±5.1%) colocalized with GFAP. These data support previous work demonstrating that most hippocampal progenitors in the adult SGZ become granule cell neurons [40]. Daily access to methamphetamine decreased neurogenesis [BrdU/NeuN-IR cells: I-ShA, 1020±196; ShA, 467±46; LgA, 360±42; F(3,17)=5.4, p=0.01] (Fig. 3c). The LgA group showed a strong trend toward reduced gliogenesis, but no statistical significance was achieved due to high variability between groups (BrdU/GFAP-IR cells: I-ShA, 324±126; ShA, 128±51; LgA, 65±24; p=0.16) (Fig. 3d).

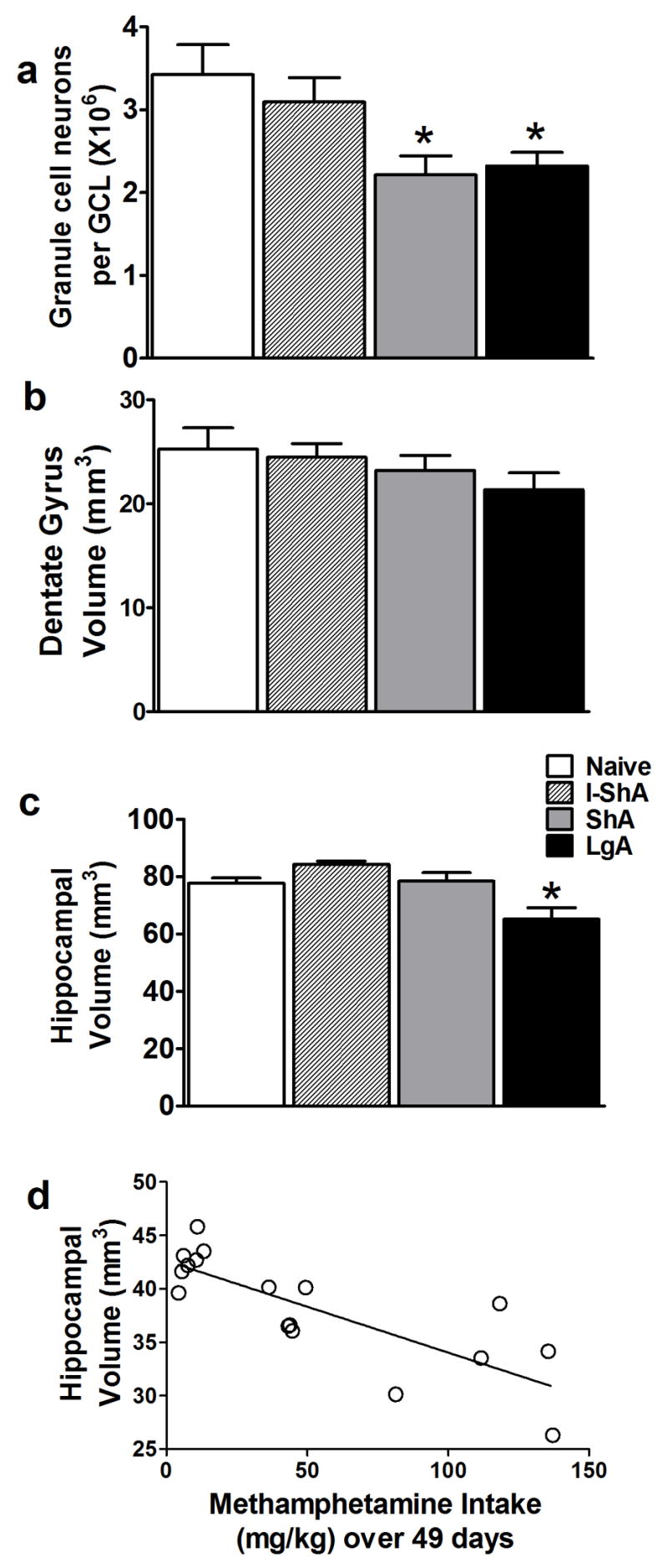

Methamphetamine self-administration decreases hippocampal volume and granule cell number

Previous reports have implied that chronic stress decreases hippocampal volume by decreasing hippocampal proliferation [41]. Therefore, the changes in hippocampal granule cell neurons and volume as a result of decreases in proliferation, maturation, and survival after methamphetamine self-administration in I-ShA, ShA, and LgA rats were explored. I-ShA rats did not demonstrate altered granule cell neuron numbers or hippocampal and dentate volume. ShA and LgA rats had reduced number of hippocampal granule cell neurons [F(3,21)=4.9, p=0.01] (Fig. 4a). The ShA and LgA rats did not show altered dentate volume despite decreases in proliferation and survival of SGZ precursors, and decreases in granule cell neurons. Only LgA rats showed a significant decrease in hippocampal volume [F(3,22)=8.6, p=0.0008] (Fig. 4c). Simple regression analysis demonstrated a negative correlation between total methamphetamine intake and hippocampal volume (Pearson correlation: hippocampal volume, r=-0.80, r2=0.64, p=0.001) (Fig. 4d). No other factors, including volume of dentate gyrus or total number of granule cell neurons, showed a significant correlation with total methamphetamine intake (data not shown).

Figure 4. Daily but not intermittent methamphetamine self-administration decreased number of hippocampal granule cells and hippocampal volume.

(a–c) (*) p < 0.05 compared with control. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 6–9 per treatment group. (d) Simple regression analysis of total methamphetamine intake, x axis, and hippocampal volume, y axis.

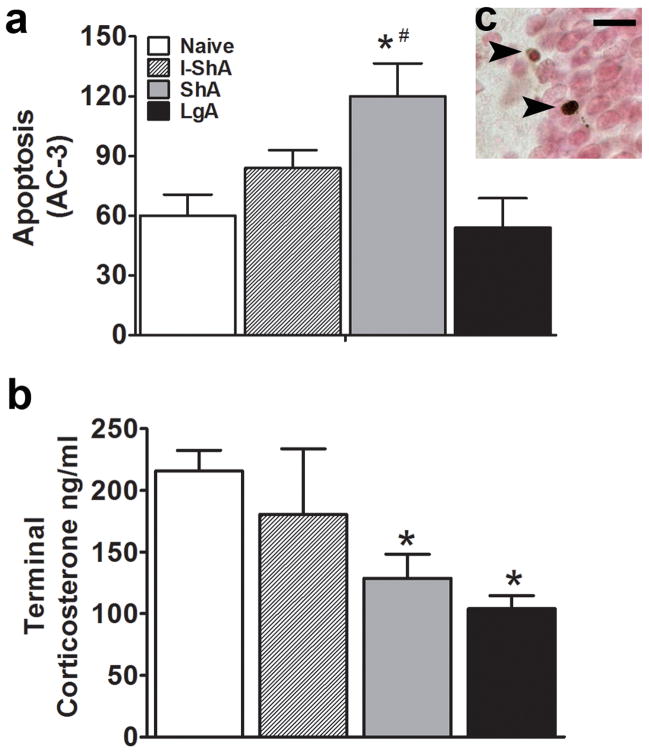

Methamphetamine self-administration alters cell death and terminal corticosterone levels

The ShA, but not I-ShA or LgA, rats showed increased apoptosis in the hippocampal SGZ [F(3,29)=5.2, p=0.005] (Fig 5a), suggesting that daily limited exposure to methamphetamine was neurotoxic in the hippocampus. Terminal corticosterone was determined in the samples from naive, I-ShA, ShA, and LgA rats. ShA and LgA, but not I-ShA rats had decreased corticosterone levels [F(3,23)=6.1, p=0.003] (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5. Methamphetamine self-administration altered hippocampal apoptosis and terminal corticosterone levels.

(a) Quantitative analysis of total number of dying cells (AC-3-IR apoptotic cells), (b) terminal plasma levels of corticosterone (ng/ml) in control and daily access methamphetamine groups. (c) Brightfield image of two apoptotic cells indicated by arrowheads. Scale bar = 10 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 4–6 in each group, (*) p < 0.05 compared with control, (#) p < 0.05 compared with LgA group.

Discussion

The self-administration data from the I-ShA, ShA, and LgA rats provide evidence that distinct patterns of methamphetamine intake may be related to human patterns of methamphetamine abuse: recreational, chronic, and dependent. Given that experimenter-administered methamphetamine in rodents decreases hippocampal-dependent memory [42], methamphetamine-dependent individuals show hippocampal dysfunction [2], and hippocampal behavior is partly maintained by the generation of new functional neurons [6–12], methamphetamine self-administration presents a useful model to explore methamphetamine dependence-induced alterations in adult hippocampal neurogenesis.

The present findings demonstrate the dynamic regulation of hippocampal neurogenesis by methamphetamine and underscore how different durations of methamphetamine access alter distinct aspects of hippocampal neurogenesis. For example, methamphetamine self-administration with intermittent access increased active division (seen in Ki-67-IR cell and cells per cluster analysis), differentiation, and maturation of hippocampal progenitors. These immediate pro-proliferative effects did not alter survival and neurogenesis of hippocampal progenitors, perhaps because of opposing effects on proliferation of late progenitors and differentiation of postmitotic neurons. In contrast to intermittent access, daily limited, extended access to methamphetamine self-administration decreased all aspects of hippocampal neurogenesis, namely, proliferation, differentiation, maturation, and survival. Such profound changes in hippocampal neurogenesis resulted in reduced hippocampal granule cell neurons and volume. The data suggest, therefore, that decreased hippocampal neurogenesis may be a contributor to the reinstatement of drug-seeking and hippocampal behavioral deficits associated with psychostimulants observed in animal models.

Proliferating progenitor cells in the SGZ are heterogeneous, and Ki-67 labels cell types of varied proliferative activity, namely, types 2a/2b/3 [33]; therefore, it is critical to consider how different durations of methamphetamine self-administration alter distinct subtypes of SGZ progenitors. We used a combination of Ki-67 and DCX labeling to differentiate proliferating progenitors in the SGZ. For example, a cell in the SGZ that is Ki-67+/DCX− is type 2a [33], and Ki-67+/DCX+ is type 2b/3 [33] or type I [43]. Such distinctions of SGZ cell types are believed to demonstrate the progression of neural progenitors during early neuronal development. Intermittent access increased Ki-67-IR cells (presumably type 2a cells) and decreased type 2b/3 cells, whereas daily limited, extended access decreased all cell types. The increase in Ki-67-IR cells by intermittent access did not produce more neurogenesis. Therefore, an explanation for the opposing effects of intermittent methamphetamine on hippocampal proliferation and neurogenesis could be that the cell cycle of proliferating progenitors is lengthened. For example, a cell that is actively dividing and trapped in the gap1 (G1) phase of the cell cycle would still express Ki-67 [44]. If the initial increase in Ki-67-IR cells by intermittent methamphetamine represents a large number of progenitors trapped in G1, ‘proliferation’ of progenitors as such would be reduced, albeit with a higher number of Ki-67-IR cells being observed. Although additional markers would be needed to test this hypothesis, it appears that exposure to even modest amounts of methamphetamine may cause long-term changes in the hippocampal proliferative environment, resulting in reduced neurogenic capacity in the hippocampus.

Doublecortin labeling was used to determine changes in differentiating and maturing young neurons. Preliminary morphological analysis of DCX-IR cells revealed that the increase in Ki-67-IR cells in the intermittent group did not extend to an increase in early-phase DCX-IR cells (early-phase, Fig. 6). Therefore, an alternative explanation for the effects of intermittent access on active division and neurogenesis is that intermittent access may have produced an environment in the SGZ that caused proliferating progenitors to divide abnormally (seen as an increase in Ki-67-IR cells per cluster), thus preventing them from differentiating into late progenitors, perhaps by prematurely moving dividing cells into the quiescent (G0) phase of the cell cycle. To support this hypothesis, Ki-67 expression is robust in actively dividing cells, and its activation begins to decay in cells that have exited the cell cycle [34, 45]. Such evidence suggests that Ki-67 could be detected in postmitotic (G0) cells [46], depending on the time lag from exiting mitosis [47]. Therefore, the increase in Ki-67-IR cells, with no detectable change in early-phase DCX-IR cells and decreased Ki-67/DCX-IR cells in the I-ShA rats (Fig. 6), suggests that intermittent access may have delayed the ‘switching off’ of Ki-67 expression in quiescent or postmitotic immature neurons. Interestingly and parallel to the effects on Ki-67-IR cells, intermittent access increased late-phase DCX-IR cells but did not produce parallel increases in postmitotic immature neurons or mature neurons (Fig. 6). Thus, it appears that occasional exposure to methamphetamine initiates allostatic mechanisms that may include a decrease in neurogenesis with daily limited or extended exposure to the drug, and thus contribute to the ‘spiraling distress’ of addiction. Therefore, even intermittent access to methamphetamine initiates hippocampal neurodegeneration that in turn may contribute to escalated use [48, 49]. Taken together, we provide initial evidence for subchronic vs. chronic psychostimulant use targeting distinct populations of developing adult hippocampal progenitors.

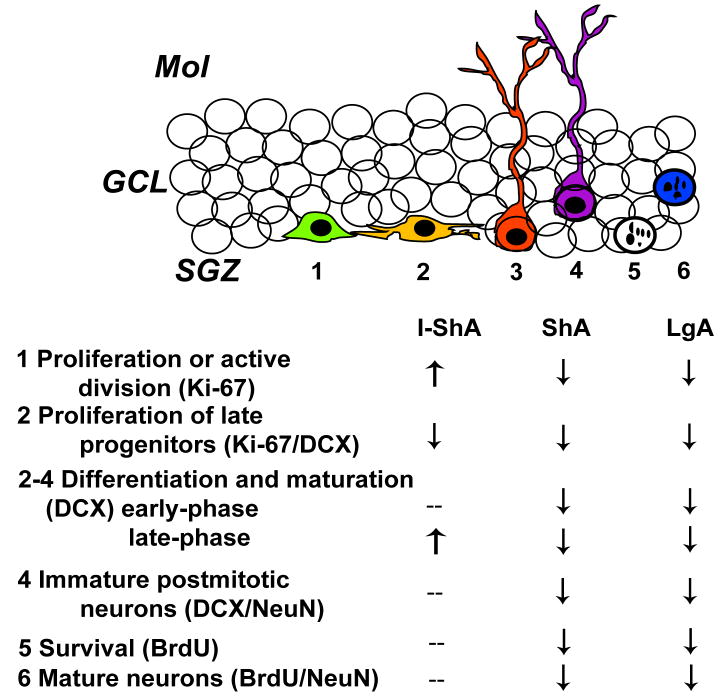

Figure 6. Hippocampal neurogenesis is altered by methamphetamine self-administration.

Intermittent short access to methamphetamine increased active division but did not enhance differentiation and adult neurogenesis, likely produced by decreased neurogenic environment in the hippocampus. Short and long access to methamphetamine decreased proliferation, differentiation, maturation, and neurogenesis, likely produced by decreased proliferative and neurogenic capacity of the adult hippocampus. SGZ, subgranular zone; GCL, granule cell layer; MOL, molecular layer;--, no change; ↑, increase; ↓, decrease.

In addition to the potential impact of methamphetamine on how a precursor moves through the cell cycle (e.g., cell cycle arrest), it is possible that methamphetamine acts to decrease cell birth by mediating cell death. Probing for cell death markers is a powerful way of assessing different forms of cell death. Incorporating a marker for apoptosis, we demonstrated that daily (ShA), but not intermittent (I-ShA) access increased apoptosis in the hippocampal SGZ. Although the increase in apoptosis was not as substantial as the decrease in proliferation and survival, methamphetamine may be producing cell death through a pathway independent of apoptosis [50, 51]. Changes in apoptosis seen after 49 days of methamphetamine self-administration (in all three groups) may not mark changes regulated by methamphetamine in the earlier exposure period that may have contributed to the decrease in neurogenesis. In addition to considering cell death as a mechanism for methamphetamine-induced altered hippocampal integrity, other mechanisms, such as increases in corticosterone levels via altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity could be involved. However, we show that ShA and LgA rats had decreased terminal corticosterone levels. While corticosterone may have contributed in part to some of the observed findings at some point (perhaps earlier) during the course of methamphetamine self-administration, there is no clear relationship between terminal levels of corticosterone and hippocampal neurogenesis. Given that the involvement of corticosterone in methamphetamine-induced altered hippocampal integrity is correlative, many more experiments beyond the scope of this manuscript (such as inactivation of the HPA axis) will be necessary to test this hypothesis.

Related morphological changes that may have occurred due to reduced hippocampal neurogenesis by methamphetamine also were explored. Methamphetamine abuse in humans reduces hippocampal size [2]; therefore, changes in granule cell neuron numbers, dentate gyrus and hippocampal volumes were determined in the present study. The ShA and LgA rats had reduced granule cell neurons and, LgA rats had reduced hippocampal volume, suggesting that the decrease in hippocampal neurogenesis resulted in a cascade of events that initially decreased granule cell neurons followed by structural changes in the hippocampus. The present findings demonstrate that our model of methamphetamine intake has clinical implications, and escalation in self-administration mimics the structural changes seen in methamphetamine-dependent individuals, especially in the adult hippocampus. Such profound alterations in hippocampal granule cells and volume by methamphetamine self-administration elucidates one potential mechanism underlying methamphetamine-induced alterations in spatial memory and function dependent on the hippocampus.

In addition to the changes in hippocampal integrity (proliferation and maturation of progenitors, cell death, granule cell neuron number and volume), methamphetamine may be altering the hippocampal neurogenic niche [52, 53], perhaps via alterations in endogenous neurotransmitters and growth factors, to produce its neurodegenerative effects. Potential factors include dopamine (activation of distinct dopamine receptors is pro-proliferative; [54]), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (which is pro-proliferative and methamphetamine alters its levels in regions implicated in addiction; [55, 56]), and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (which rescues methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity; [57]). Although we have listed these potential candidates that could be altered by methamphetamine to disturb the neurogenic niche, future studies focusing on the regulation of such factors will draw attention to hippocampal neurogenesis as a potential target for therapeutic approaches to treat methamphetamine dependence. The results described herein should stimulate further exploration of the interplay between microenvironment, cell cycle kinetics, and neurogenesis in the hippocampus by methamphetamine self-administration. Investigation of the vulnerability of actively dividing cells in the adult brain to psychostimulant exposure and psychostimulant-induced alterations in neuroplasticity and neurotoxicity—cellular events that maintain adult hippocampal integrity—can greatly enhance our understanding of neural plasticity and behavior dampened by psychostimulant abuse.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA010072 to GFK, DA022473 to CDM) supported the study. We acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Ron Smith for volumetric analysis, Mike Pham, Hanan Jammal, and Krisha Begalla from the independent study program at University of California, San Diego, and Simon Huynh and Guadalupe Coronado from the Harvey Mudd College Upward Bound Program for assistance with animal behavior and immunohistochemistry. We thank Drs. Xiaoying Lu and Donna Gruol for assistance with confocal microscopy, and Caroline Lanigan for assistance with statistical analysis. We appreciate the technical support of Robert Lintz, Yanabel Grant, and Dr. Thomas Greenwell, the editorial assistance of Mike Arends, and Dr. Olivier George for critical reading of the manuscript. This is publication number 19005 from The Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roehr B. Half a million Americans use methamphetamine every week. Bmj. 2005;331:476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7515.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, Simon SL, Geaga JA, Hong MS, Sui Y, et al. Structural abnormalities in the brains of human subjects who use methamphetamine. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6028–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0713-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J Comp Neurol. 1965;124:319–35. doi: 10.1002/cne.901240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Praag H, Christie BR, Sejnowski TJ, Gage FH. Running enhances neurogenesis, learning, and long-term potentiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13427–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Praag H, Schinder AF, Christie BR, Toni N, Palmer TD, Gage FH. Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature. 2002;415:1030–4. doi: 10.1038/4151030a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gould E, Beylin A, Tanapat P, Reeves A, Shors TJ. Learning enhances adult neurogenesis in the hippocampal formation. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:260–5. doi: 10.1038/6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shors TJ, Townsend DA, Zhao M, Kozorovitskiy Y, Gould E. Neurogenesis may relate to some but not all types of hippocampal-dependent learning. Hippocampus. 2002;12:578–84. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Earnheart JC, Schweizer C, Crestani F, Iwasato T, Itohara S, Mohler H, et al. GABAergic control of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in relation to behavior indicative of trait anxiety and depression states. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3845–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3609-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tashiro A, Makino H, Gage FH. Experience-specific functional modification of the dentate gyrus through adult neurogenesis a critical period during an immature stage. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3252–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4941-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge S, Yang CH, Hsu KS, Ming GL, Song H. A critical period for enhanced synaptic plasticity in newly generated neurons of the adult brain. Neuron. 2007;54:559–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastings NB, Tanapat P, Gould E. Neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain. Clin Neurosci Res. 2001;1:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan MS, Hinds JW. Neurogenesis in the adult rat electron microscopic analysis of light radioautographs. Science. 1977;197:1092–4. doi: 10.1126/science.887941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamashima T, Tonchev AB, Yukie M. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in rodents and primates: endogenous, enhanced, and engrafted. Rev Neurosci. 2007;18:67–82. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2007.18.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Ledford CC, Parker MP, Case JM, Mehta RH, et al. The role of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala, and dorsal hippocampus in contextual reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:296–309. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt HD, Anderson SM, Famous KR, Kumaresan V, Pierce RC. Anatomy and pharmacology of cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vorel SR, Liu X, Hayes RJ, Spector JA, Gardner EL. Relapse to cocaine-seeking after hippocampal theta burst stimulation. Science. 2001;292:1175–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1058043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canales JJ. Adult neurogenesis and the memories of drug addiction. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257:261–70. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0730-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisch AJ, Barrot M, Schad CA, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Opiates inhibit neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:7579–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120552597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abrous DN, Adriani W, Montaron MF, Aurousseau C, Rougon G, Le Moal M, et al. Nicotine self-administration impairs hippocampal plasticity. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3656–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03656.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi M, Suzuki T, Seki T, Namba T, Juan R, Arai H, et al. Repetitive cocaine administration decreases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1025:351–62. doi: 10.1196/annals.1316.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rueda D, Navarro B, Martinez-Serrano A, Guzman M, Galve-Roperh I. The endocannabinoid anandamide inhibits neuronal progenitor cell differentiation through attenuation of the Rap1/B-Raf/ERK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46645–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nixon K, Crews FT. Binge ethanol exposure decreases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1087–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandyam CD, Norris RD, Eisch AJ. Chronic morphine induces premature mitosis of proliferating cells in the adult mouse subgranular zone. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2004;76:783–94. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harburg GC, Hall FS, Harrist AV, Sora I, Uhl GR, Eisch AJ. Knockout of the mu opioid receptor enhances the survival of adult-generated hippocampal granule cell neurons. Neuroscience. 2007;144:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tateno M, Ukai W, Hashimoto E, Ikeda H, Saito T. Implication of increased NRSF/REST binding activity in the mechanism of ethanol inhibition of neuronal differentiation. J Neural Transm. 2006;113:283–93. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 3°. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandyam CD, Wee S, Eisch AJ, Richardson HN, Koob GF. Methamphetamine self-administration and voluntary exercise have opposing effects on medial prefrontal cortex gliogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11442–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2505-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West MJ, Andersen AH. An allometric study of the area dentata in the rat and mouse. Brain Res. 1980;2:317–48. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(80)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes TE, Valtz NL, McKay RD. Downregulation of CDC2 upon terminal differentiation of neurons. New Biol. 1991;3:259–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donovan MH, Yazdani U, Norris RD, Games D, German DC, Eisch AJ. Decreased adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the PDAPP mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol. 2006;495:70–83. doi: 10.1002/cne.20840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West MJ, Slomianka L, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of neurons in thesubdivisions of the rat hippocampus using the optical fractionator. Anat Rec. 1991;231:482–97. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092310411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bacchi CE, Gown AM. Detection of cell proliferation in tissue sections. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1993;26:677–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kronenberg G, Reuter K, Steiner B, Brandt MD, Jessberger S, Yamaguchi M, et al. Subpopulations of proliferating cells of the adult hippocampus respond differently to physiologic neurogenic stimuli. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:455–63. doi: 10.1002/cne.10945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandyam CD, Harburg GC, Eisch AJ. Determination of key aspects of precursor cell proliferation, cell cycle length and kinetics in the adult mouse subgranular zone. Neuroscience. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cameron HA, McKay RD. Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;435:406–17. doi: 10.1002/cne.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corotto FS, Henegar JA, Maruniak JA. Neurogenesis persists in the subependymal layer of the adult mouse brain. Neurosci Lett. 1993;149:111–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90748-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandyam CD, Crawford EF, Eisch AJ, Rivier CL, Richardson HN. Stress experienced in utero reduces sexual dichotomies in neurogenesis, microenvironment, and cell death in the adult rat hippocampus. Dev Neurobiol. 2008 doi: 10.1002/dneu.20600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plumpe T, Ehninger D, Steiner B, Klempin F, Jessberger S, Brandt M, et al. Variability of doublecortin-associated dendrite maturation in adult hippocampal neurogenesis is independent of the regulation of precursor cell proliferation. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jessberger S, Nakashima K, Clemenson GD, Jr, Mejia E, Mathews E, Ure K, et al. Epigenetic modulation of seizure-induced neurogenesis and cognitive decline. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5967–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0110-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cameron HA, Woolley CS, McEwen BS, Gould E. Differentiation of newly born neurons and glia in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 1993;56:337–44. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90335-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Czeh B, Michaelis T, Watanabe T, Frahm J, de Biurrun G, van Kampen M, et al. Stress-induced changes in cerebral metabolites, hippocampal volume, and cell proliferation are prevented by antidepressant treatment with tianeptine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12796–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211427898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vorhees CV, Inman-Wood SL, Morford LL, Broening HW, Fukumura M, Moran MS. Adult learning deficits after neonatal exposure to D-methamphetamine: selective effects on spatial navigation and memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4732–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04732.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mandyam CD, Crawford EF, Eisch AJ, Rivier CL, Richardson HN. Stress experienced in utero reduces sexual dichotomies in neurogenesis, microenvironment, and cell death in the adult rat hippocampus. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:575–89. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:311–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dayer AG, Ford AA, Cleaver KM, Yassaee M, Cameron HA. Short-term and long-term survival of new neurons in the rat dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:563–72. doi: 10.1002/cne.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bullwinkel J, Baron-Luhr B, Ludemann A, Wohlenberg C, Gerdes J, Scholzen T. Ki-67 protein is associated with ribosomal RNA transcription in quiescent and proliferating cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:624–35. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerdes J, Lemke H, Baisch H, Wacker HH, Schwab U, Stein H. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. Journal of Immunology. 1984;133:1710–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug abuse: hedonic homeostatic dysregulation. Science. 1997;278:52–8. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koob GF. Neuroadaptive mechanisms of addiction: studies on the extended amygdala. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13:442–52. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng X, Wang Y, Chou J, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine causes widespread apoptosis in the mouse brain: evidence from using an improved TUNEL histochemical method. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;93:64–9. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cadet JL, Jayanthi S, Deng X. Speed kills: cellular and molecular bases of methamphetamine-induced nerve terminal degeneration and neuronal apoptosis. Faseb J. 2003;17:1775–88. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0073rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abrous DN, Koehl M, Le Moal M. Adult neurogenesis: from precursors to network and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:523–69. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00055.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:223–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.051804.101459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Kampen JM, Hagg T, Robertson HA. Induction of neurogenesis in the adult rat subventricular zone and neostriatum following dopamine D receptor stimulation. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2377–87. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Narita M, Aoki K, Takagi M, Yajima Y, Suzuki T. Implication of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the release of dopamine and dopamine-related behaviors induced by methamphetamine. Neuroscience. 2003;119:767–75. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pencea V, Bingaman KD, Wiegand SJ, Luskin MB. Infusion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor into the lateral ventricle of the adult rat leads to new neurons in the parenchyma of the striatum, septum, thalamus, and hypothalamus. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:6706–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06706.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cass WA. GDNF selectively protects dopamine neurons over serotonin neurons against the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine. J Neurosci. 1996;16:8132–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-08132.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.