Abstract

The binding of integrins to extracellular matrix triggers signals that promote cell spreading. We previously demonstrated that expression of the integrin β1 cytoplasmic domain in the context of a chimeric transmembrane receptor with the Tac subunit of the interleukin-2 receptor (Tac-β1) inhibits cell spreading. To study the mechanism whereby Tac-β1-inhibits cell spreading, we examined the effect of Tac-β1 on early signaling events following integrin engagement namely FAK and Src signaling. We infected primary fibroblasts with adenoviruses expressing Tac or Tac-β1 and found that Tac-β1 prevented FAK activation by inhibiting the phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr-397. In contrast, Src activation was maintained, as phosphorylation of Src at Tyr-419 and Tyr-530 were not responsive to expression of Tac-β1. Importantly, adhesion-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the Src substrates p130Cas and paxillin was inhibited, indicating that Src signaling was blocked by Tac-β1. These Src-dependent signaling events were found to require FAK signaling. Our results suggest that Tac-β1 inhibits cell spreading, at least in part, by preventing the phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr-397 and the assembly of signaling complexes necessary for phosphorylation of p130Cas and other downstream effectors.

Keywords: integrin, FAK, Src, cell spreading, integrin beta cytoplasmic domain

Introduction

Integrin receptors are α/β heterodimeric transmembrane proteins that cluster within sites of cell-matrix contact and transmit signals across the cell membrane in response to matrix adhesion [1]. These signals promote protrusion of the cell membrane during cell spreading to allow formation of new actin-associated adhesion sites [1]. The integrin β subunit cytoplasmic domain (β tail) contributes to these processes by linking integrins to the actin cytoskeleton and to intracellular signaling cascades [2–6].

To study the role of the integrin β tail in regulating cell adhesion and signaling, we expressed the integrin β1 cytoplasmic domain (β1 tail) in the context of a Tac-β1 chimeric receptor containing the transmembrane and extracellular domain of the Tac (α) subunit of the human interleukin-2 receptor [7]. We previously demonstrated that clustering Tac-β1 on the surface of suspended cells triggers the tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK, p130Cas and paxillin and the GTP-loading of Rac1, indicating that clustering protein(s) associated with the integrin β tail is sufficient to activate these signaling pathways [3,4]. Importantly, Tac-β1 expressing cells are inhibited in cell spreading when they are re-adhered to an integrin ligand, suggesting that Tac-β1 titrates proteins from endogenous integrin β tails that normally activate signals to promote cell spreading [3,7]. Consistent with this hypothesis, we demonstrated that constitutively active PI 3-kinase or Rac1 restored spreading in cells expressing Tac-β1 [8].

The activation of signaling by the cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases FAK and Src are early events following integrin engagement [9,10]. The autophosphorylation of FAK at Tyr-397 results in the recruitment of signaling proteins, such as Src, and the activation of multiple signaling pathways. The Src-dependent phosphorylation of either p130Cas or paxillin promotes the formation of signaling complexes containing the adaptors CrkII and DOCK180, which can lead to Rac1 activation and cell spreading [9,10]. Our current study examined whether Tac-β1 inhibits adhesion-induced FAK and/or Src signaling. Using adenoviral expression of Tac (control) and Tac-β1 in primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs), we demonstrate that Tac-β1 inhibits the tyrosine phosphorylation of both p130Cas and paxillin. We further show that FAK activation but not Src activation is inhibited by Tac-β1. Our data support a model in which FAK activation is proximal to the β1 tail and initiates signaling events requiring Src kinases to promote cell spreading.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and adenovirus infection

Primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) were purchased from VEC technologies and cultured as previously described [8]. Adenoviral vectors directing the expression of Tac, Tac-β1, GFP and GFP-FRNK were gifts from Drs. Eva Hammer and Allen Samaral [11] respectively. High titer viruses were prepared and purified as previously described [12]. The volume of the purified virus needed for 80–98% infection was determined empirically. For adenoviral infections, 7.5 × 105 HFFs were seeded in serum-containing DMEM overnight. The cells were washed with PBS and virus was added in serum-free DMEM and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 and then with 10% FBS overnight. GFP-FRNK and GFP adenoviruses were preincubated with 0.1 mM antennepedia peptide (kindly provided by Dr. H Singer) as previously reported [13]. The infection efficiency was determined by flow cytometry [14]. Tac and Tac-β1 surface expression was detected with a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody (Becton Dickinson).

For spreading and signaling experiments, cells were resuspended at a density of 2 × 105 cells/ml in serum-free DMEM and allowed to recover for 30 min [3,8]. PP2 (Calbiochem), PP3 and DMSO were added at the start of the recovery period. Adenovirus-infected cells were used 16–18 h post infection. After recovery, cells were replated onto Col I (Vitrogen, 20ug/ml) -coated dishes and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. For spreading assays, attached cells were fixed [8] and analyzed by phase contrast microscopy. For signaling assays, replated cells were washed with PBS and lysates were generated and analyzed as previously described [3].

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to FAK pTyr-397, Src pTyr-418 (human Tyr-419), Src pTyr-529 (human Tyr-530), and pan Src were from Biosource, and to the C-terminus of FAK and the human interleukin-2 receptor α subunit from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse monoclonal antibodies to nonphosphorylated Src-Tyr-530 (clone 28) were kindly provided by Dr. Hisaaki Kawakatsu [15] and monoclonal antibodies to p130Cas and paxillin were from BD Transduction Laboratories, to vinculin from Sigma, and to phosphotyrosine (clone 4G10) from Upstate Biotechnology.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Lysates were prepared and analyzed by western blotting as previously described [3]. p130Cas and paxillin were immunoprecipitated from 200 µg of lysate by incubation with 2 µg of antibody to p130Cas or paxillin, recovered with anti-mouse IgG agarose beads (Sigma) and then analyzed for phosphotyrosine by western blotting.

Results

Tac-β1 inhibits the adhesion-induced phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr-397

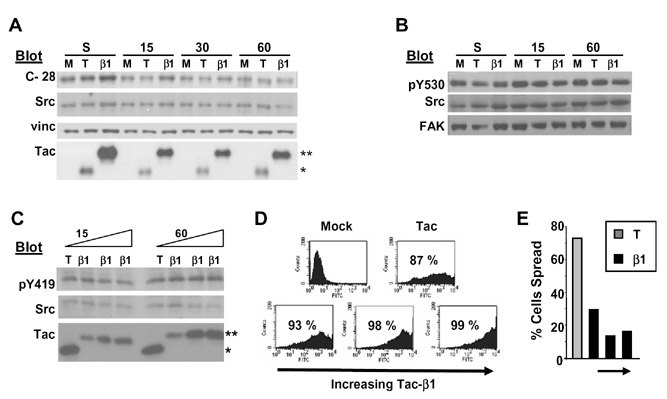

The levels of protein tyrosine phosphorylation increase in response to cell attachment to the ECM. These changes have been attributed to the regulation of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases, FAK and Src, by integrins [9,10]. Both FAK and Src can bind directly to the integrin β tail [6,16]. Thus, Tac-β1 may titrate FAK and/or Src from endogenous β tails and prevent their activation by integrin engagement. To determine whether Tac-β1 inhibits adhesion-induced tyrosine phosphorylation, we first tested whether Tac-β1 inhibits FAK activation in response to cell adhesion. Primary human dermal foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) were infected with adenoviruses that express either Tac or Tac-β1. Infected cells were replated onto collagen I (Col I) for 15, 30 and 60 min and the levels of phosphorylation at FAK’s autophosphorylation site (Tyr-397) were assayed by western blotting. Expression of Tac-β1, but not Tac, significantly decreased the levels of phosphorylation at Tyr-397 (pTyr-397) at all time points assayed (Fig. 1A–B). Consistent with our previous studies, cells expressing Tac-β1 were inhibited in spreading on Col I (Fig. 1C). Thus, the mechanism by which integrins activate FAK is disrupted by expression of Tac-β1.

Fig. 1.

Tac-β1 inhibits adhesion-induced FAK pTyr-397. (A) HFFs were mockinfected (M) or infected with adenoviruses expressing Tac (T) or Tac-β1 (β1). Infected cells were either kept in suspension or replated for 15, 30 and 60 min onto a Col I-coated substratum and the levels of FAK pTyr-397 in 20 µg of lysate were examined by western blotting. Blots were stripped and reprobed for FAK, vinculin (vinc), and then IL2-Rα to detect Tac (*) and Tac-β1 (**) expression. The levels of Tac-β1 are higher in suspension compared to the attached samples since cells expressing high levels of Tac-β1 do not attach [7,14]. (B) The levels of FAK pTyr-397 under different experimental conditions were normalized to levels in Tac expressing cells adhered for 15 min. Plotted are the results from 3 independent experiments ± SD. (C) Tac (left) and Tac-β1 (right) adenovirus-infected cells were replated onto Col I for 60 min and representative phase contrast images of their morphologies are shown.

Tac β1 does not alter Src phosphorylation at Tyr-419 or Tyr-530

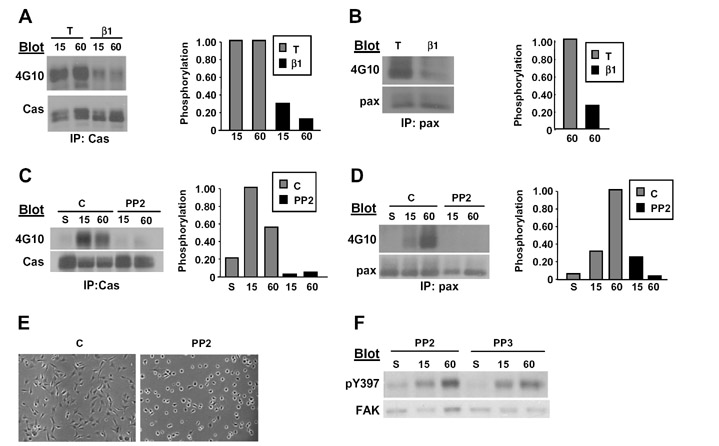

Since Src activation is usually accompanied by the dephosphorylation of Tyr-530 and phosphorylation of Tyr-419 in Src’s activation loop [17], we compared levels of phosphorylation at these residues. Tac and Tac-β1 infected cells were replated onto Col I. The status of phosphorylation at Tyr-530 was assayed using antibodies specific for non-phosphorylated Tyr-530 (Fig. 2A) and phosphorylated Tyr-530 (Fig. 2B). Expression of Tac-β1 did not alter the levels of phosphorylation at this Tyr residue. In addition, Tac-β1 did not inhibit the phosphorylation of Tyr-419 in the activation loop of Src, even at higher doses of Tac-β1 (Fig. 2C). Thus, Tac-β1 inhibited FAK, but not Src activation when HFFs were replated onto Col I.

Fig. 2.

Tac-β1 does not inhibit Src activation. (A–B). Tac-β1 does not alter the levels of phosphorylation at Tyr-530 (Src-pY530). HFFs were mock-infected (M) or infected with adenoviruses expressing Tac (T) or Tac-β1 (β1). Cells were harvested and either incubated in suspension or replated onto Col I for 15, 30 or 60 min as indicated. Twenty micrograms of lysate were analyzed by western blotting with monoclonal antibody clone 28 that recognizes non-phosphorylated Tyr-530 (A) or with antibodies specific for Src-pY530 (B) [15]. Blots were stripped and reprobed for Src, vinculin and IL2-Rα (Tac) (A) or for Src and FAK (B). The data shown is representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Tac-β1 does not inhibit phosphorylation of Src at Tyr-419. HFFs infected with the Tac (T) or increasing doses of the Tac-β1 (β1) adenovirus (1, 4, and 7 μL of purified viral stock) were harvested and replated on Col I. The levels of Src-pY419 were analyzed in 20 µg of lysate. The blot was stripped and reprobed for Src and then Tac. Even the highest level of Tac-β1 expression did not inhibit the phosphorylation of Src at Tyr-419. The data shown is representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Infection efficiencies of the Tac virus and increasing doses of Tac-β1 (4, 7 and 9 µL of virus) were analyzed by flow cytometry. Thirty-seven percent of the cells infected with 1 µl of virus expressed Tac-β1 (not shown). (E) Inhibition of cell spreading by increasing doses (4,7, and 9 µl) of Tac-β1.

Tac-β1 inhibits the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin

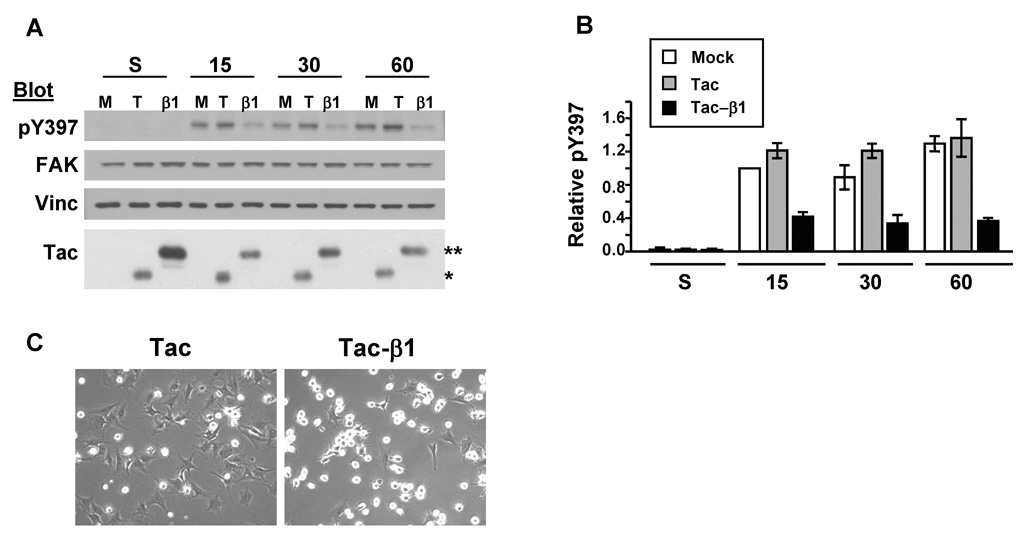

Src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas provides a pathway linking the regulation of tyrosine kinase activity to the activation of downstream effectors such as Rac1 during cell spreading. Previous studies from our laboratory indicated that clustering Tac-β1 is sufficient to induce the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas, indicating that protein interactions with the β tail are sufficient to trigger this signaling event. Thus, we determined whether Tac-β1 could inhibit the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas in response to cell adhesion, even when Src activation is not altered. For these studies, HFFs were infected with adenoviruses for Tac and Tac-β1 and the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas was assayed after 15 and 60 min of adhesion on Col I. Phosphorylation of p130Cas was observed at 15 min after replating in Tac expressing cells, which correlates with the onset of cell spreading (Fig. 3A). Expression of Tac-β1 inhibited p130Cas phosphorylation at both 15 min and 60 min after replating (Fig. 3A). Tac-β1 also significantly inhibited adhesion-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Tac-β1 and PP2 each inhibit the adhesion-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin. (A–B) HFFs were infected with adenoviruses expressing Tac or Tac-β1. Infected cells were incubated in suspension or replated onto Col I for 15 and 60 min. p130Cas (A) and paxillin (B) were immunoprecipitated from 250 µg of lysate and then analyzed for phosphotyrosine. Blots were stripped and reprobed for p130Cas or paxillin (pax). Plotted is the comparison of levels of phosphorylated p130Cas in cells expressing Tac or Tac-β1 under the various conditions normalized to the levels of phosphorylated p130Cas in Tac expressing cells adhered for 15 min (A), and the level of phosphorylated paxillin in cells expressing Tac-β1 normalized to Tac expressing cells adhered for 60 min (B). (C–E) HFFs were placed in suspension and treated with 10 µM PP2, PP3 or DMSO, and then either kept in suspension or replated onto Col I for 15 and 60 min. p130Cas (C) and paxillin (D) were immunoprecipitated as above and analyzed for phosphotyrosine. Blots were stripped and reprobed for p130Cas or paxillin (pax). Plotted are the levels of phosphorylated p130Cas or paxillin under the various experimental conditions normalized to the levels of phosphorylated p130Cas or paxillin in Tac expressing cells after 15 min of adhesion (E) Cells were treated with PP2 and replated onto Col I for 60 min. Shown are representative fields of control and PP2 treated cells. (F) Cells were treated with PP2 or PP3 and replated onto Col I. The level of FAK phosphorylation at Tyr-397 was analyzed in 20 µg of lysate. The blot was stripped and reprobed for FAK. (A–F) Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments.

Inhibition of Src-family kinases with PP2 inhibits cell spreading and the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin, but not the phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr-397

Since expression of Tac-β1 inhibited the phosphorylation of Src substrates, yet had no detectable effects on Src activation, we tested whether PP2 a pharmacological inhibitor of Src kinase activity would similarly disrupt cell spreading and the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin. HFFs were treated in suspension with 10 µM PP2, PP3 or DMSO and then plated on Col I for the indicated times. PP2 inhibited the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin (Fig 3C and D) and cell spreading (Fig. 3E), but did not prevent the adhesion-induced phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr-397 (Fig. 3F). These data indicate that Src signaling plays a central role in regulating cell spreading and suggest that Src-dependent phosphorylation of p130Cas and/or paxillin are important downstream of integrins in this process.

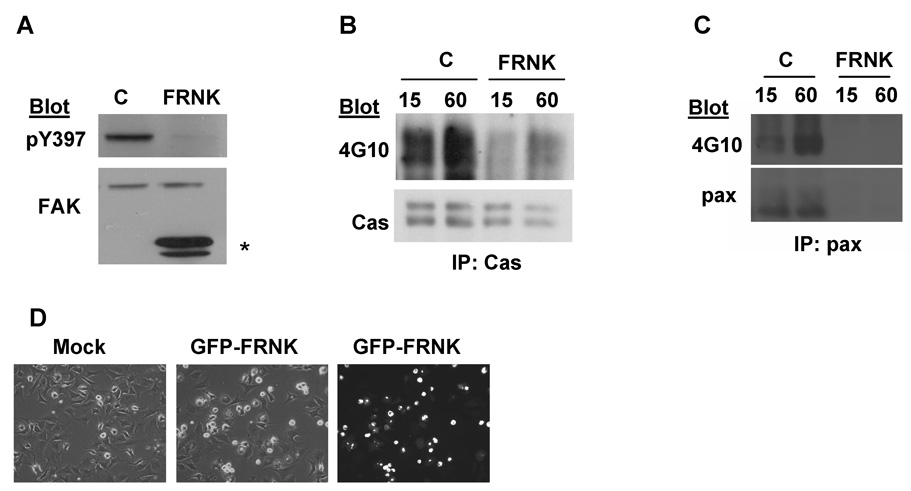

Disruption of FAK signaling inhibits cell spreading and the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin

Our data suggest that β tail function and Src activity are necessary for the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin. However, the contribution of FAK signaling to these tyrosine phosphorylation events was unclear. Current evidence suggests that the requirement for FAK in the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas depends on the integrin heterodimer mediating adhesion [18]. In particular, the role of FAK in regulating the phosphorylation of p130Cas in HFFs adhered to Col I was not known. To examine the contribution of FAK in our system, we expressed the recombinant form of the naturally occurring FAK inhibitor, FAK related non-kinase (FRNK), previously reported to inhibit endogenous FAK signaling [19]. HFFs were infected with adenoviruses that directed the expression of GFP or a GFP-FRNK fusion protein and effects on cell spreading and adhesion signaling were assayed. GFP-FRNK inhibited the activation of endogenous FAK (Fig. 4A), the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas (Figs 4B) and cell spreading (Fig. 4D). Additionally, FRNK inhibited the expression of paxillin (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that FAK signaling is required for integrins to promote the tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin, and HFF spreading on Col I.

Fig. 4.

FAK signaling is required for the adhesion-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin. (A) FRNK inhibits adhesion-induced FAK activation. HFFs were infected with adenoviruses directing the expression of GFP (C) or FRNK. Levels of FAK pTyr-397 were assayed after 60 min of adhesion to Col I. Blots were stripped and reprobed for total FAK. The position of FRNK is indicated by an asterisk. (B and C) FRNK inhibits the adhesion-induced phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin. Infected HFFs were replated onto Col I for 15 and 60 min. p130Cas and paxillin were immunoprecipitated and levels of phosphotyrosine were assayed. (D) Control or FRNK infected cells were replated onto Col I for 60 min and cell morphology was assayed by phase contrast and immunofluorescence microscopy. Shown are representative fields of control and FRNK expressing cells. (A–D) Similar results were obtained in 2 independent experiments.

Discussion

The major findings of the current study are the following: (1) Tac-β1 inhibits adhesion-induced FAK activation, but does not alter Src activation; (2) Tac-β1 prevents the Src-dependent phosphorylation of p130Cas and paxillin; and (3) FAK signaling is required for these phosphorylation events. These findings support a model in which the integrin β-tail coordinates the activation of FAK and Src downstream signaling to p130Cas and paxillin when HFFs are adhered to Col I.

Current models for FAK activation involve unleashing inhibitory intramolecular interactions through conformational changes and protein unfolding reminiscent of mechanisms for Src activation. FAK contains an amino terminal FERM domain, a central catalytic domain, and a carboxyl terminal focal adhesion-targeting or FAT domain [9,10]. The FERM domain interacts with the catalytic domain to repress FAK activation and autophosphorylation at Tyr-397 [5,20]. Thus, adhesion-induced protein interactions with the FERM domain may activate FAK by preventing these autoinhibitory interactions [5,10,20]. Interestingly, FAK binds to peptides modeled from the membrane-proximal region of integrin β tails [16], suggesting that the binding of the β-tail may activate FAK. In fact, more recent studies demonstrated that the binding of FAK to β tails in vitro is sufficient to trigger FAK activation [5]. Thus, Tac-β1 may titrate FAK from β tails of endogenous integrins and prevent FAK activation in response to cell adhesion. However, if FAK is titrated by the direct binding of its FERM domain to Tac-β1, then our data suggest that this interaction is not sufficient to activate FAK in a cellular context.

Integrins regulate the activation and signaling downstream of Src-family kinases by multiple mechanisms [9]. Src-family kinases can bind directly and specifically to individual integrin β tails [6]. For example, c-Src binds directly to the β3 tail and clustering β3 integrins increases Src activation [6]. Cell adhesion can also activate Src kinases independent of β tail function [21]. Furthermore, the mechanism by which β1 integrins increase Src activity is integrin-heterodimer specific, occurring by FAK-dependent and -independent pathways [18]. Our data indicate that the expression of Tac-β1 in HFFs does not inhibit Src phosphorylation at either Tyr-419 or Tyr-530 and that the level of phosphorylation of Src is not significantly altered in response to cell adhesion to Col I. Thus, HFFs may have basal Src activity, which is regulated independent of β1 integrins and which is sufficient to trigger tyrosine phosphorylation events required for cell spreading.

The Src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas can occur by FAK dependent and independent mechanisms [18]. Our results indicate that adhesion of HFFs to Col I triggers the phosphorylation of p130Cas by a mechanism that requires both FAK and Src activity. Src is recruited to active FAK via the interaction of its SH2 domains with pTyr-397 of FAK, while paxillin and p130Cas can bind to the C-terminus of FAK resulting in the formation of signaling complexes containing FAK, Src and p130Cas and/or paxillin [10]. Since FRNK contains binding sites for both p130Cas and paxillin, it is likely that FRNK disrupts the formation of these complexes. Thus, Tac-β1 and FRNK may both titrate proteins required for the assembly of signaling complexes containing endogenous FAK, Src, and p130Cas. Furthermore, the ability of FRNK to inhibit FAK phosphorylation at Tyr-397 suggests that the activation of FAK in response to cell adhesion requires protein interactions mediated by the C-terminus of FAK. Thus, the β tail may regulate FAK activation by coordinating protein interactions at both the FERM and C-terminal domains of FAK.

We observed that FRNK inhibits the expression of paxillin protein in HFFs, similar to what has also already been observed in normal rat ventricular myocytes [11]. The mechanism by which FRNK inhibits the expression of paxillin is not yet understood; however, it is a cell-type specific phenomenon, as FRNK does not inhibit paxillin expression in bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells [22].

Mechanisms that regulate FAK/Src signaling are important since their downstream effectors are critical regulators of cell migration, proliferation, survival, wound healing and tumor invasion [9,10]. Our studies focused on identifying the mechanisms by which the integrin β tail regulates FAK/Src signaling in primary fibroblasts on a 2-dimensional matrix. The highly contractile phenotype of fibroblasts on 2-dimensional substrates resemble the contractile property of fibroblasts within rigid 3-dimensional matrices of tumor stroma and wound tissue associated with scar formation [23]. Thus, the identification of pathways that regulate FAK/ Src signaling on 2-dimensional matrices are likely to provide insight into the molecular pathways involved in disease states associated with contractile fibroblasts in vivo and may lead to the identification of new molecular targets for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Eva Hammer, Alan Samaral, Harold Singer and Hisaaki Kawakatsu for critical reagents utilized in this studies. This work was supported by NIH grant GM51540 to SEL and by AHA postdoctoral fellowship 0020180T to ALB. During the preparation of this manuscript, ALB was supported in part by the Katrina Visiting Faculty Program, NCMHD and NIDCR/NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brakebusch C, Fassler R. The integrin-actin connection, an eternal love affair. EMBO J. 2003;22:2324–2333. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodeau AL, Berrier AL, Mastrangelo AM, Martinez R, LaFlamme SE. A functional comparison of mutations in integrin β cytoplasmic domains: effects on the regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation, cell spreading, cell attachment and β1 integrin conformation. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:2795–2807. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.15.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berrier AL, Martinez R, Bokoch GM, LaFlamme SE. The integrin β tail is required and sufficient to regulate adhesion signaling to Rac1. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4285–4291. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper LA, Shen TL, Guan JL. Regulation of focal adhesion kinase by its amino-terminal domain through an autoinhibitory interaction. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:8030–8041. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8030-8041.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arias-Salgado EG, Lizano S, Sarkar S, Brugge JS, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ. Src kinase activation by direct interaction with the integrin β cytoplasmic domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:13298–13302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336149100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaFlamme SE, Thomas LA, Yamada SS, Yamada KM. Single subunit chimeric integrins as mimics and inhibitors of endogenous integrin functions in receptor localization, cell spreading and migration, and matrix assembly. J. Cell Biol. 1994;126:1287–1298. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.5.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berrier AL, Mastrangelo AM, Downward J, Ginsberg M, LaFlamme SE. Activated R-ras, Rac1, PI 3-kinase and PKCε can each restore cell spreading inhibited by isolated integrin β1 cytoplasmic domains. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:1549–1560. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;6:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo Y, Guan JL. Integrin signaling through focal adhesion kinase. In: LaFlamme SE, Kowalczyk A, editors. Cell Junctions: Adhesion, Development and Disease. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.; 2008. pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heidkamp MC, Bayer AL, Kalina JA, Eble DM, Samarel AM. GFP-FRNK disrupts focal adhesions and induces anoikis in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 2002;90:1282–1289. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000023201.41774.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He TC, Zhou S, da Costa LT, Yu J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2509–2514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gratton JP, Yu J, Griffith JW, Babbitt RW, Scotland RS, Hickey R, Giordano FJ, Sessa WC. Cell-permeable peptides improve cellular uptake and therapeutic gene delivery of replication-deficient viruses in cells and in vivo. Nat. Med. 2003;9:357–362. doi: 10.1038/nm835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mastrangelo AM, Homan SM, Humphries MJ, LaFlamme SE. Amino acid motifs required for isolated β cytoplasmic domains to regulate 'in trans' β1 integrin conformation and function in cell attachment. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:217–229. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawakatsu H, Sakai T, Takagaki Y, Shinoda Y, Saito M, Owada MK, Yano J. A new monoclonal antibody which selectively recognizes the active form of Src tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:5680–5685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaller MD, Otey CA, Hildebrand JD, Parsons JT. Focal adhesion kinase and paxillin bind to peptides mimicking β integrin cytoplasmic domains. J. Cell Biol. 1995;130:1181–1187. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pellicena P, Miller WT. Coupling kinase activation to substrate recognition in SRC-family tyrosine kinases. Front. Biosci. 2002;7:d256–d267. doi: 10.2741/A725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu L, Bernard-Trifilo JA, Lim Y, Lim ST, Mitra SK, Uryu S, Chen M, Pallen CJ, Cheung NK, Mikolon D, Mielgo A, Stupack DG, Schlaepfer DD. Distinct FAK-Src activation events promote α5β1 and α4β1 integrin-stimulated neuroblastoma cell motility. Oncogene. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210770. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlaepfer DD, Mitra SK, Ilic D. Control of motile and invasive cell phenotypes by focal adhesion kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1692:77–102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lietha D, Cai X, Ceccarelli DF, Li Y, Schaller MD, Eck MJ. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of focal adhesion kinase. Cell. 2007;129:1177–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wary KK, Mariotti A, Zurzolo C, Giancotti FG. A requirement for caveolin- 1 and associated kinase Fyn in integrin signaling and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Cell. 1998;94:625–634. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Usatyuk PV, Natarajan V. Regulation of reactive oxygen species-induced endothelial cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts by focal adhesion kinase and adherens junction proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005;289:L999–L1010. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00211.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berrier AL, Yamada KM. Cell-matrix adhesion. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007;213:565–573. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]