Abstract

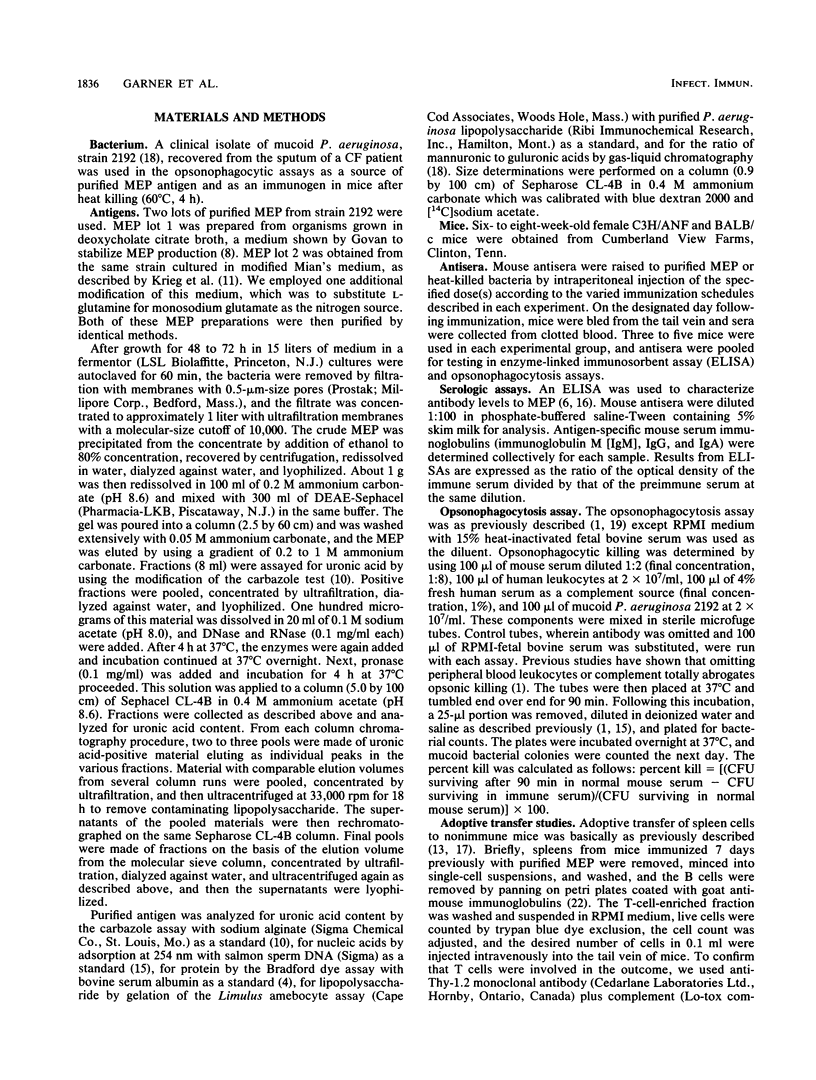

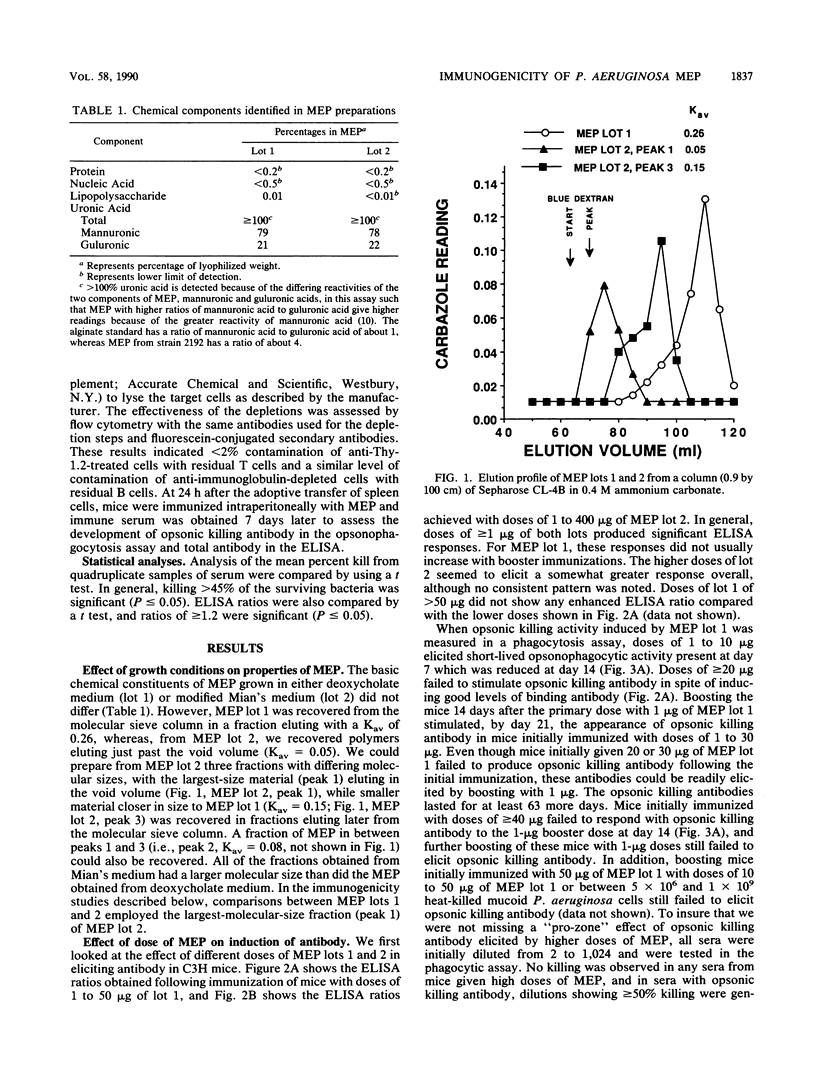

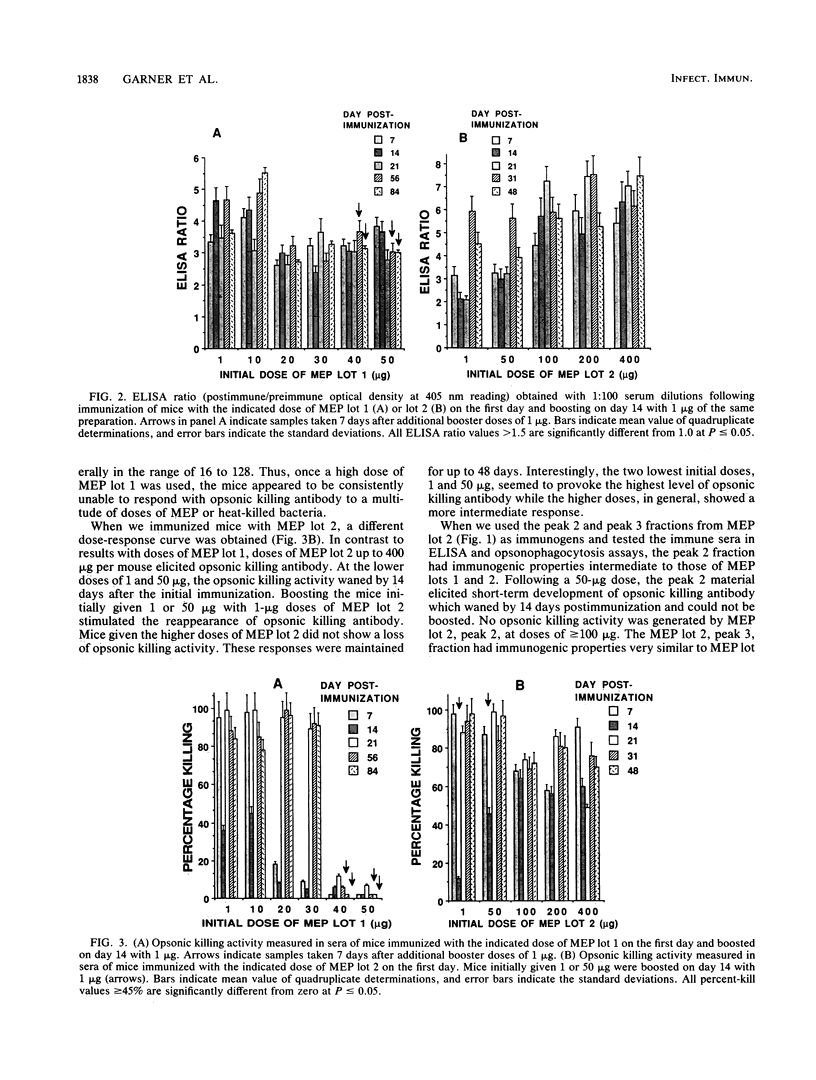

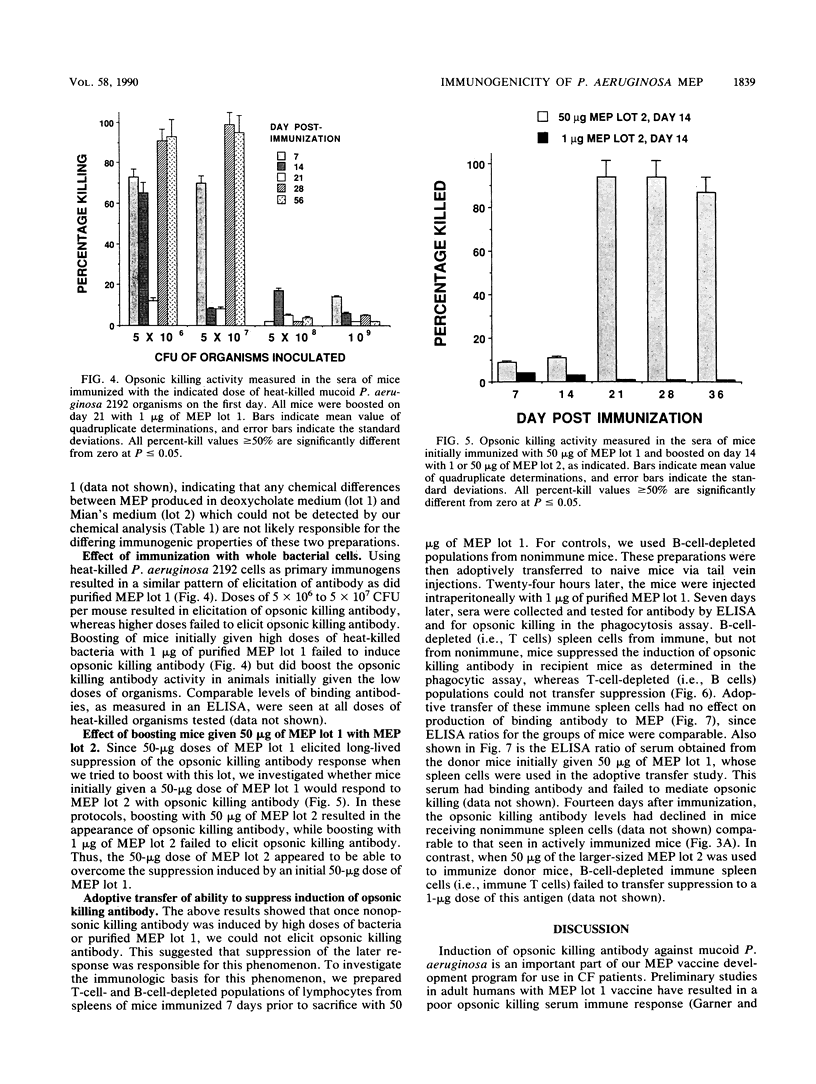

Previous studies have shown that antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide (MEP) can be divided into two types on the basis of their functional activity. One type is able to mediate opsonic killing in conjunction with leukocytes and complement, and the other type is not. We investigated, in mice, the properties of this antigen associated with elicitation of opsonic killing antibody. We found that smaller-sized material (Kav = 0.26), which has been tested as a human vaccine, elicited opsonic killing antibody in mice at low doses (1 to 10 micrograms) and at doses of greater than or equal to 40 micrograms, only nonopsonic killing antibody was produced. A similar dose effect was seen with heat-killed mucoid P. aeruginosa cells. After immunization with high doses of this MEP or the heat-killed cells, the mice were refractory to induction of opsonic killing antibody no matter what dose of MEP was used as a booster. In contrast, a larger-molecular-weight preparation (Kav = 0.05) elicited opsonic killing antibody over a wide dose range (1 to 400 micrograms). Additionally, 50 micrograms of the larger-sized preparation could overcome the suppression induced by 50 micrograms of the smaller material. Suppression elicited by 50 micrograms of the smaller material could be adoptively transferred to nonimmune mice with the T-cell fraction of spleen cells. These results indicate that both molecular size and dose are critical determinants for eliciting opsonic killing antibody to mucoid P. aeruginosa after immunizing with MEP.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ames P., DesJardins D., Pier G. B. Opsonophagocytic killing activity of rabbit antibody to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1985 Aug;49(2):281–285. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.281-285.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P. J., Stashak P. W., Amsbaugh D. F., Prescott B. Regulation of the antibody response to type 3 pneumococcal polysaccharide. IV. Role of suppressor T cells in the development of low-dose paralysis. J Immunol. 1974 Jun;112(6):2020–2027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braley-Mullen H. Direct demonstration of specific suppressor T cells in the mice tolerant to type III pneumococcal polysaccharide: two-step requirement for development of detectable suppressor cells. J Immunol. 1980 Oct;125(4):1849–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner M. B., Strominger J. L., Krangel M. S. The gamma delta T cell receptor. Adv Immunol. 1988;43:133–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan L. E., Kureishi A., Rabin H. R. Detection of antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate extracellular polysaccharide in animals and cystic fibrosis patients by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1983 Aug;18(2):276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.2.276-282.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis P. B., di Sant'Agnese P. A. Diagnosis and treatment of cystic fibrosis. An update. Chest. 1984 Jun;85(6):802–809. doi: 10.1016/s0012-3692(16)62421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govan J. R. Mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the influence of culture medium on the stability of mucus production. J Med Microbiol. 1975 Nov;8(4):513–522. doi: 10.1099/00222615-8-4-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson C. A., Jeanes A. A new modification of the carbazole analysis: application to heteropolysaccharides. Anal Biochem. 1968 Sep;24(3):470–481. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg D. P., Bass J. A., Mattingly S. J. Aeration selects for mucoid phenotype of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Dec;24(6):986–990. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.6.986-990.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukac M., Pier G. B., Collier R. J. Toxoid of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A generated by deletion of an active-site residue. Infect Immun. 1988 Dec;56(12):3095–3098. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.12.3095-3098.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham R. B., Pier G. B., Powderly W. G. Suppressor T cells regulating the cell-mediated immune response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa can be generated by immunization with anti-bacterial T cells. J Immunol. 1988 Dec 1;141(11):3975–3979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pier G. B., Desjardins D., Aguilar T., Barnard M., Speert D. P. Polysaccharide surface antigens expressed by nonmucoid isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Aug;24(2):189–196. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.2.189-196.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pier G. B., Markham R. B. Induction in mice of cell-mediated immunity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa by high molecular weight polysaccharide and vinblastine. J Immunol. 1982 May;128(5):2121–2125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pier G. B., Matthews W. J., Jr, Eardley D. D. Immunochemical characterization of the mucoid exopolysaccharide of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 1983 Mar;147(3):494–503. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pier G. B. Safety and immunogenicity of high molecular weight polysaccharide vaccine from immunotype 1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Invest. 1982 Feb;69(2):303–308. doi: 10.1172/JCI110453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pier G. B., Saunders J. M., Ames P., Edwards M. S., Auerbach H., Goldfarb J., Speert D. P., Hurwitch S. Opsonophagocytic killing antibody to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide in older noncolonized patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1987 Sep 24;317(13):793–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709243171303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powderly W. G., Schreiber J. R., Pier G. B., Markham R. B. T cells recognizing polysaccharide-specific B cells function as contrasuppressor cells in the generation of T cell immunity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Immunol. 1988 Apr 15;140(8):2746–2752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood R. E., Boat T. F., Doershuk C. F. Cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976 Jun;113(6):833–878. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.113.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki L. J., Sato V. L. "Panning" for lymphocytes: a method for cell selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Jun;75(6):2844–2848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]