Abstract

A20 is a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-inducible zinc finger protein that contains both ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating activities. A20 negatively regulates NFκB (nuclear factor κB) signaling induced by TNF receptor family and Toll-like receptors, but the mechanism of A20 action is poorly defined. Here we show that a fraction of endogenous and ectopically expressed A20 is localized to an endocytic membrane compartment that is in association with the lysosome. The lysosomal association of A20 requires its carboxy terminal zinc finger domains, but is independent of its ubiquitin-modifying activities. Interestingly, A20 mutants defective in membrane association also contain reduced NFκB inhibitory activity. These findings suggest the involvement of a lysosome-associated mechanism in A20-dependent termination of NFκB signaling.

Keywords: A20, lysosomal degradation, ubiquitin, NFκB, deubiquitinating enzyme

Introduction

Members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family mediate cellular responses to various environmental stimuli such as inflammation, septic shock, viral infection, and apoptotic signals [1–3]. The binding of TNF and its related cytokines to their corresponding receptor induces oligomerization of the receptor and subsequent activation of various signaling pathways that include nuclear factor κB (NFκB), Jun N-terminal kinase, p38, extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) [4]. One of the best studied pathways is the activation of NFκB by TNF receptor 1 (TNFR-I). Activation of TNFR-I induces the assembly of a receptor-associated complex. This complex comprises the adaptor protein TRADD (TNF receptor associated death domain), the Ser/Thr protein kinase RIP1 (receptor interacting protein), and a TRAF (TNF receptor-associated factor) domain-containing protein termed TRAF2 [5–10]. The formation of this complex triggers a series of intracellular events that lead to the activation of the transcription factor NFκB. TNFR-I also activates JNK kinase through TRAF2, resulting in the activation of another transcription factor c-Jun [11–14].

TNFR-I mediated NFκB activation is tightly controlled by both positive and negative regulatory circuits. The zinc finger protein A20 is a potent inhibitor of TNFR-I-mediated NFκB signaling [15]. Intriguingly, the expression of A20 is upregulated upon NFκB activation [16], which then promotes the termination of NFκB signaling [17–23]. Thus, A20 is part of a negative regulatory feedback loop that restrains NFκB activation. As expected, lack of A20-dependent regulatory circuit leads to prolonged NFκB activation, which causes sustained inflammatory responses and cachexia as revealed in mice deficient for A20 [23]. The expression of A20 is also upregulated by IL-1, lipopolysaccharide, and by the activation of the B cell surface receptor CD40 [15, 24]. Thus, the NFκB inhibitory function of A20 may not be limited to the TNF pathway. Indeed, recent studies showed that A20 can also downregulate NFκB signal induced by Toll-like receptors [24, 25]. The mechanism by which A20 operates in these signaling events is not well understood. It was recently shown that A20 can inhibit TNFR-I dependent NFκB signaling by regulating the stability of RIP1. During this process, A20 functions as a dual ubiquitin-modifying enzyme; it first acts as a deubiquitinating enzyme [26–29]. The deubiquitinating activity harbored in A20’s amino-terminal OTU (ovarian tumor) domain removes Lys63-linked ubiquitin chains from RIP1. Subsequently, A20 functions as a ubiquitin ligase to assemble Lys48-linked ubiquitin chains on RIP1 using its carboxy terminal zinc finger domains, which triggers the proteasome dependent degradation of RIP1 [27]. Likewise, it was shown that A20 can also deubiquitinate TRAF6, a key signaling molecule required for Toll-like receptor induced NFκB signaling [25].

Although the downregulation of RIP1 by A20 can to some extent explain the inhibitory effect of A20 on TNFR-I induced NFκB signaling [30], A20 mutants lacking ubiquitin-modifying activities due to lesions in either the OTU or the zinc finger domains can still inhibit NFκB signaling under some circumstances [21, 26, 31, 32]. This suggests the existence of a ubiquitin independent mechanism for A20 function in certain cellular context. To explore the potential additional mechanism employed by A20 to downregulate NFκB signaling, we characterize the subcellular localization of A20 using both confocal microscopy and biochemical fraction approaches. Strikingly, our data reveal that a fraction of A20 protein is localized to a lysosome-associated membrane compartment. The association of A20 with the lysosome raises the possibility that A20 may downregulate certain signaling molecules required for sustained NFκB activation by targeting them for degradation in the lysosome.

Materials and Methods

Constructs, antibodies, chemicals and cell lines

The pRK-Flag-A20 wt and pRK-HA-A20 wt plasmids were described previously [21, 24, 33]. The pEYFP-A20 plasmid was constructed by ligating the PCR amplified A20 coding sequence into the BglII and SalI sites of the pEYFP-C1 vector (Clontech). The insert was shuttled to other pEXFP-C1 vectors to create plasmids expressing A20 tagged with other fluorescence proteins. Constructs expressing A20 variants were generated by site directed mutagenesis following the conventional protocol. Flag, Myc, and A20 (59A426) monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Sigma, Roche, and Imagenex, respectively. LAMP1 antibody (H5G11) was purchased from Santa Cruz. Myc-ubiquitin, E1, and GST-Ubc7 were purchased from Boston Biochem Inc. Lysotraker and FM4-64 were purchased from Invitrogen. 293T, COS7, and HeLa cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained according to standard protocols.

Transfection, immunoblotting, and luciferase experiments

Transfection was done with Polyfect (Qiagen) for COS7 cells, the TransIT293 reagent (Mirus) for 293T cells, Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) for MEF cells, and HeLa Monster (Mirus) for HeLa cells. Immunoblotting was performed according to standard protocols. All experiments were repeated at least once, and representative images of gels are shown. NFκB luciferase reporter experiments were performed as previously described [33].

Subcellular fractionation and membrane floatation experiments

Cells were lysed in a hypotonic buffer (50mM Hepes, 7.3, 10mM potassium chloride, 2mM magnesium chloride, 1mM dithiothreitol , plus a protease inhibitor cocktail) by passing through 25G needles and by subsequent homogenization in a Dounce homogenizer. Cell extracts were cleared by centrifugation at 1,000g to remove the nuclei and intact cells. The supernatant fractions were subjected to further centrifugation at 100,000g to separate the membrane pellets from the cytosol. To float the lysosome-associated membranes, microsomes were resuspended in a buffer M (50mM Hepes, 7.3, 150mM potassium acetate, 2mM magnesium chloride) that also contains 67% sucrose. Membranes (50µl) were placed at the bottom of an ultracentrifugation tube under a layer of 130µl buffer M containing 40% sucrose and a layer of 20µl buffer M containing 20% sucrose. Membranes were subjected to centrifugation in a Beckman TLA100.1 rotor at 200kg for 1h. Fractions (20µl) were taken and analyzed by immunoblotting.

In vitro ubiquitination experiment

293T cells transfected with plasmids expressing either A20 or A20 Znf4C2 were lysed in NP40 lysis buffer (50mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150mM sodium chloride, 0.5% NP40, 5mM magnesium chloride and a protease inhibitor cocktail). A20 was immunopurified using Flag antibody bound to the protein G beads. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to in vitro ubiquitination reaction according to previously described protocol [34]. Briefly, Myc-ubiquitin (25µM), E1 (60nM), GST-Ubc7 (200nM) were added to A20 immunoprecipitates, and the reaction was incubated at 37 °C in a buffer containing 25mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2mM magnesium/ATP, and 0.1mM DTT for 1 hour. The ubiquitination reaction was stopped by addition of SDS sample buffer. Samples were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Immunostaining and live cell imaging

Immunofluorescence experiments were performed as described previously [35]. Briefly, cells fixed in a phosphor saline solution (PBS) containing 4% paraformaldehyde were permeabilized in a solution containing 0.1% NP40 and 4% normal donkey serum. Cells were then stained with primary and secondary antibodies in the same buffer. Unless specified in the figure legends, the following antibody dilutions were used. A20, 1:250; Flag, 1:1000. To stain the lysosome, Lysotracker was used at 500nM. To label the endocytic compartment, cells were incubated in a buffer containing 95mM sodium chloride, 50mM potassium chloride, 10mM glucose, 10mM Hepes 7.4, 1.2mM calcium chloride, 1.2mM magnesium chloride, 5µg/ml FM4-64 at room temperature for 4min. Cells were imaged using either a Zeiss Axiovert fluorescence microscope or a Zeiss LSM 510 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with a 63X oil immersion Plan-Apochromat objective (N/A 1.4). For 3-D deconvolution, we used the fast reiterative algorithm provided in the Axiovision 4.5 software. For live cell imaging, cells grown in LabTek chambers were transfected with plasmids expressing the indicated proteins, and imaged using an inverted Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope equipped with a 63X oil immersion Plan-Apochromat objective (N/A 1.4). For high speed multi-channel imaging, the interlace mode was used to simultaneously capture signals from multiple fluophores.

Results

Membrane association of A20

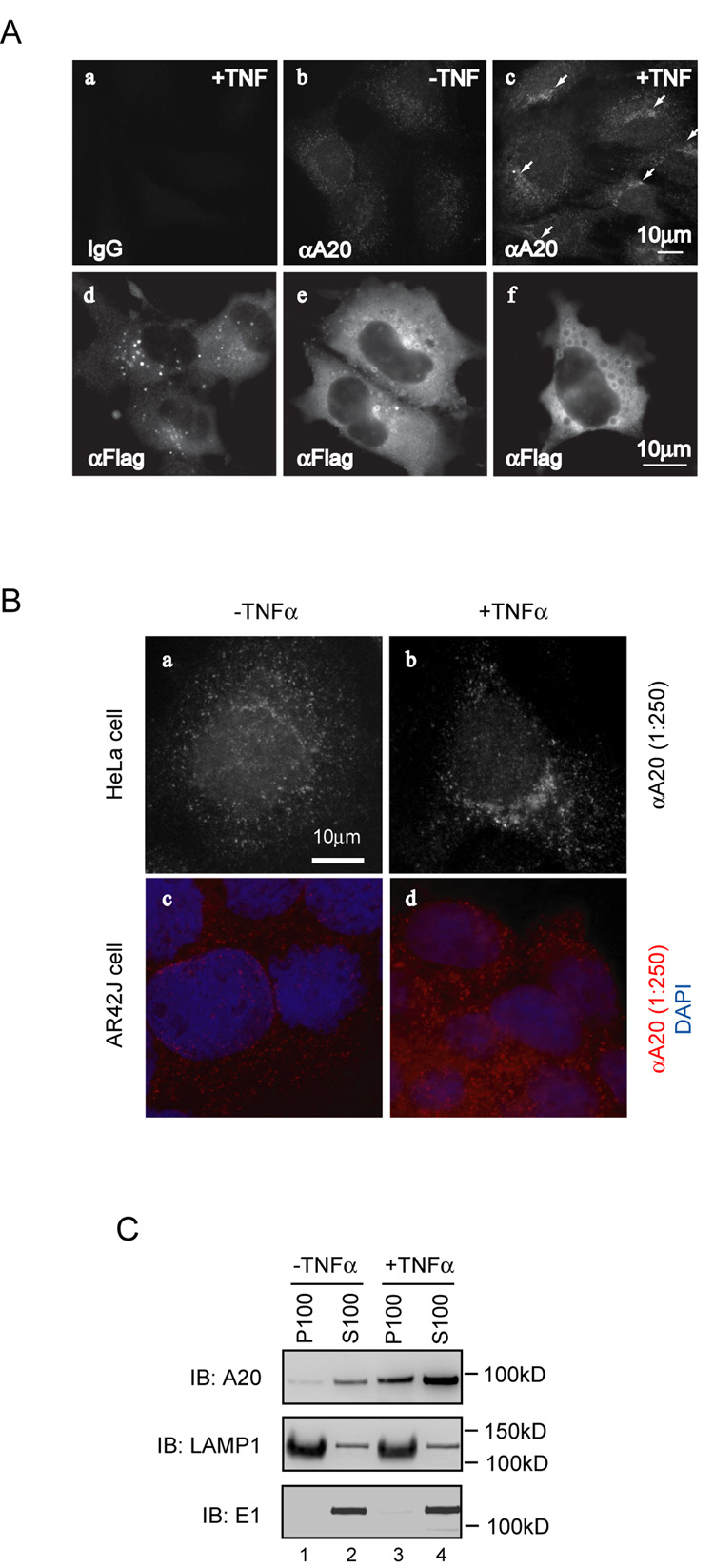

To dissect the mechanism by which A20 inhibits NFκB signaling, we first examined the subcellular localization of endogenous A20 by immunostaining with an A20 specific monoclonal antibody. To our surprise, A20 did not display diffuse cytoplasmic staining as might be expected from its being a soluble protein. Instead, a fraction of A20 appeared to associate with certain membrane vesicles that were localized near the nuclei in HeLa cells (Fig. 1A, panel b; Fig. 1B, panel a). The punctate perinuclear staining of A20 was also seen in a pancreatic tumor cell line (AR42J) (Fig. 1B, panel c), and was more apparent in cells treated with TNFα (Fig. 1A, panel c; Fig. 1B, panels b, d). This staining pattern was not observed in cells stained with a control antibody (Fig. 1A, panel a).

Figure 1. A20 is localized to an intracellular membrane compartment.

(A) (a–c) Subcellular localization of endogenous A20 in HeLa cells. HeLa cells treated with TNFα (80ng/ml, 6h) or non-treated were stained with either an A20 specific monoclonal antibody (αA20) or control IgG. Arrows indicate the perinuclear enrichment of A20-containing vesicles. Same exposure time was used for these images. (d–f) COS7 cells expressing Flag-tagged wild type A20 were stained with an anti-Flag antibody (αFlag). Images represent cells with A20-containing vesicles of different size. (B) Membrane association of endogenous A20. HeLa cells (a, b) or AR42J cells (c, d) treated with TNFα or non-treated were stained with an anti-A20 monoclonal antibody at the indicated concentration. The bottom panels also show the nuclei stained by DAPI in blue. Images were obtained with a Zeiss Axiovert fluorescence microscope equipped with a 63X oil immersion Plan-Apochromat objective (N/A 1.4). (C) Biochemical fractionation experiment. HeLa cells untreated (−TNFα) or treated with TNFα (+TNFα) were lysed, fractionated, and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to either A20, the lysosomal membrane protein LAMP1, or the cytosolic protein E1. Note that the loading of the supernatant fraction is equivalent to ~30% of the pellet fraction. The small amount of LAMP1 in S100 fractions was likely due to incomplete fractionation.

The membrane association of A20 was further confirmed by biochemical fractionation experiments. To this end, HeLa cells were lysed in a hypotonic buffer that lacked detergent. Post-nuclear fractions of the cell extract were subjected to further centrifugation at 100,000g. The resulting pellet fraction (P100) contained the total membranes, and supernatant fraction (S100) contained the cytosol. Immunoblotting showed that a small fraction of endogenous A20 was present in the membrane fraction, and as expected, when HeLa cells were exposed to TNFα, the expression of A20 was upregulated, and the level of membrane associated A20 was also increased (Fig. 1C).

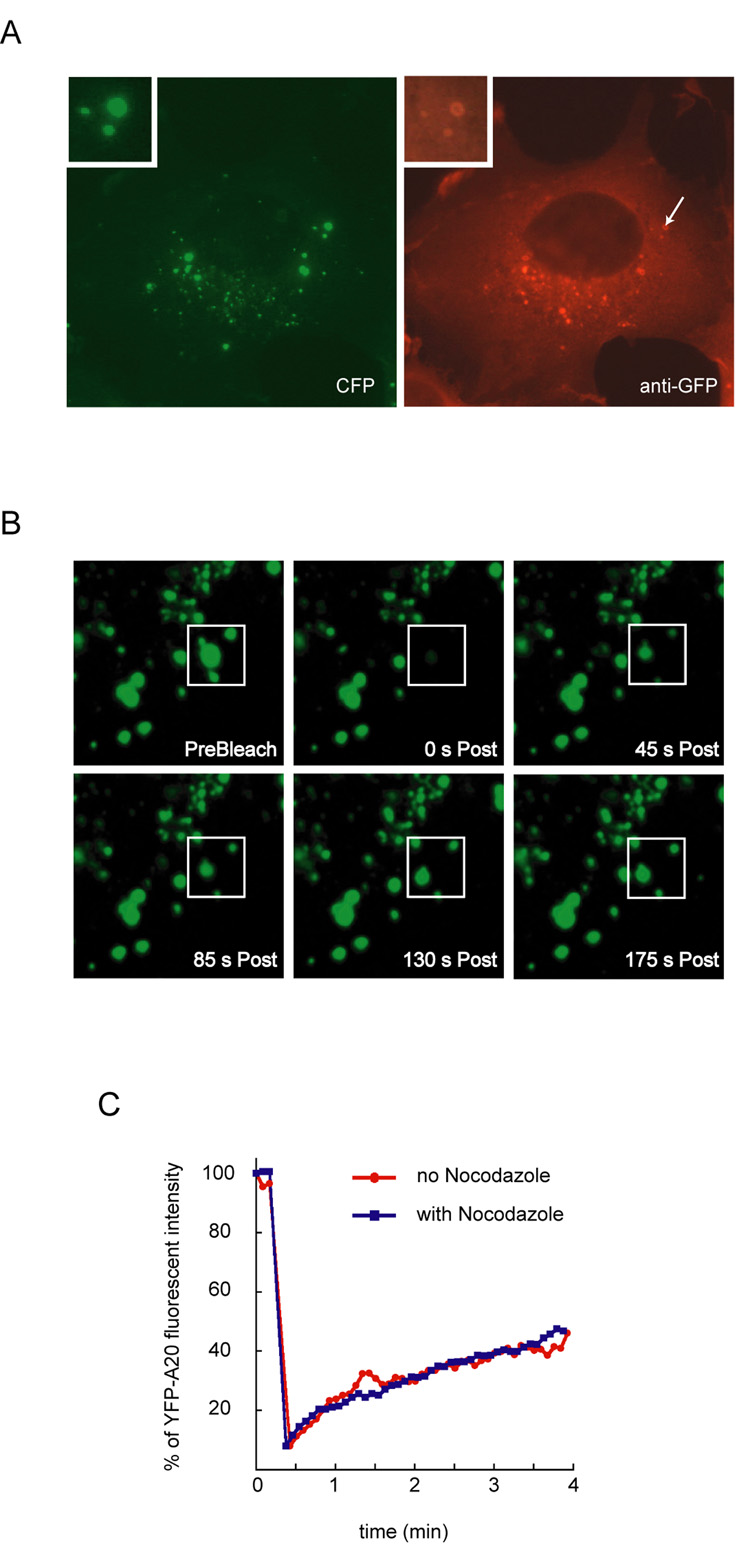

We next expressed epitope-tagged A20 in COS7 cells. Similar to endogenous A20, Flag-A20 was localized to the cytosol and to small vesicles that were enriched in a juxtanuclear region in most A20 expressing cells (Fig. 1A, panel d). In a fraction of cells, larger A20-containing vesicles were formed (Fig. 1A, panels e, f), which was likely due to higher levels of A20 expression. CFP- or YFP-tagged A20 (CFP-A20/YFP-A20) was similarly localized in many bright speckles near the nuclei (Fig. 2). These vesicles appeared to contain CFP-A20 both in the membranes and in the lumen, although the luminal CFP-A20 could not be stained by a GFP antibody, presumably because the lumen of these compartments was inaccessible to antibodies when cells were permeabilized by a mild detergent NP40 during immunostaining (Fig. 2A). Consistent with this interpretation, previous work demonstrated that a significant fraction of A20 can not be extracted by NP40 lysis buffer [36].

Figure 2. Dynamic association of A20 with membrane.

(A) Membrane association of CFP-tagged A20. COS7 cells transfected with a CFP-A20 expressing constructs were stained with an anti-GFP antibody (in red), which also recognized the CFP tag. The cells were also imaged using a band pass filter specific for CFP (in green). The insets show an enlarged view of a vesicle indicated by the arrow. (B) FRAP experiment demonstrates the dynamic association of A20 with membranes. A small area (indicated by the boxes) in a COS7 cell expressing YFP-tagged A20 was repeatedly targeted with a high intensity laser light to photobleach the YFP-A20 signal. The recovery of the fluorescent signal was monitored by time-lapse confocal microscopy. (C) Quantification of the FRAP experiments as in B. Where indicated, cells were first treated with nocodazole (10µg/ml) for 10min before photobleaching.

We next performed FRAP (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching) experiments using YFP-A20 to determine the dynamics of A20-membrane association. Because of the highly mobile nature of the vesicles, we performed photobleaching on larger more stationary YFP-A20-containing structures. Shortly after the removal of the YFP-A20 signal by photobleaching, a rapid recovery of the signal was observed (Fig. 2B). Since the recovery of YFP-A20 signal was similarly observed in cells treated with nocodazole, a microtubule disrupting drug (Fig. 2C), which inhibited the movement and thus the fusion of A20-containing vesicles, the recovery of YFP-A20 signal after photobleaching most likely occurs by recruitment of YFP-A20 from a nearby cytosolic pool rather than by fusion of other A20-containing vesicles with the photobleached membranes. Together, these data demonstrate that a fraction of both endogenously and ectopically expressed A20 is dynamically associated with an intracellular membrane compartment localized near the nuclei.

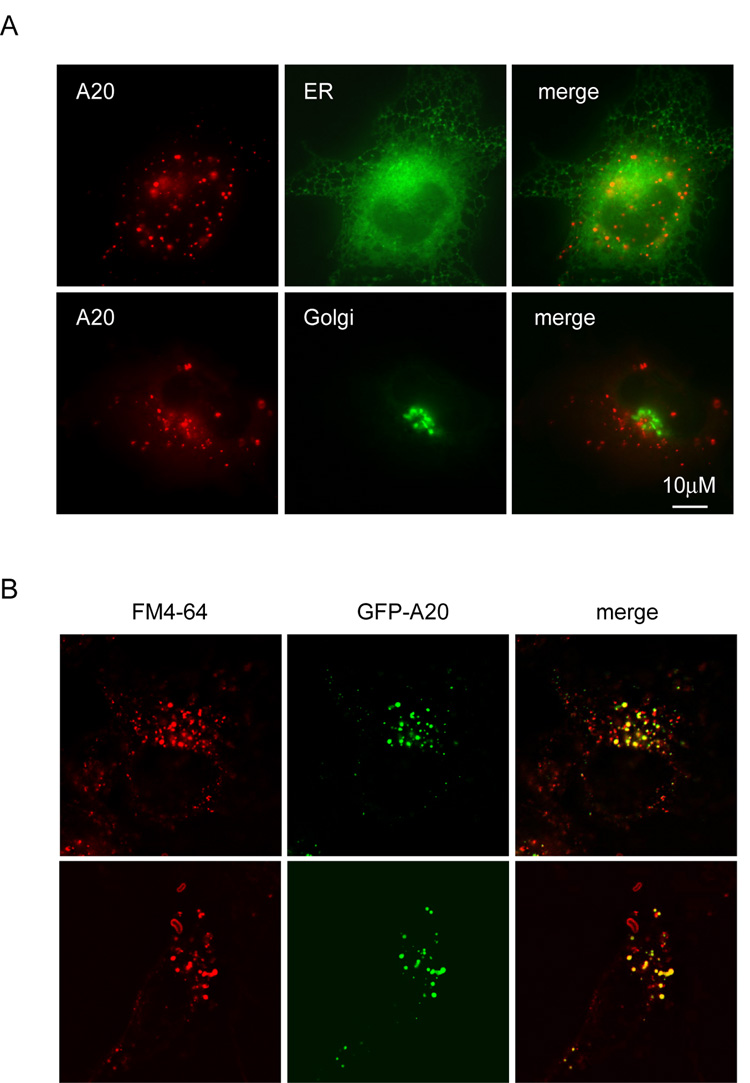

Localization of A20 to a lysosome-associated endocytic compartment

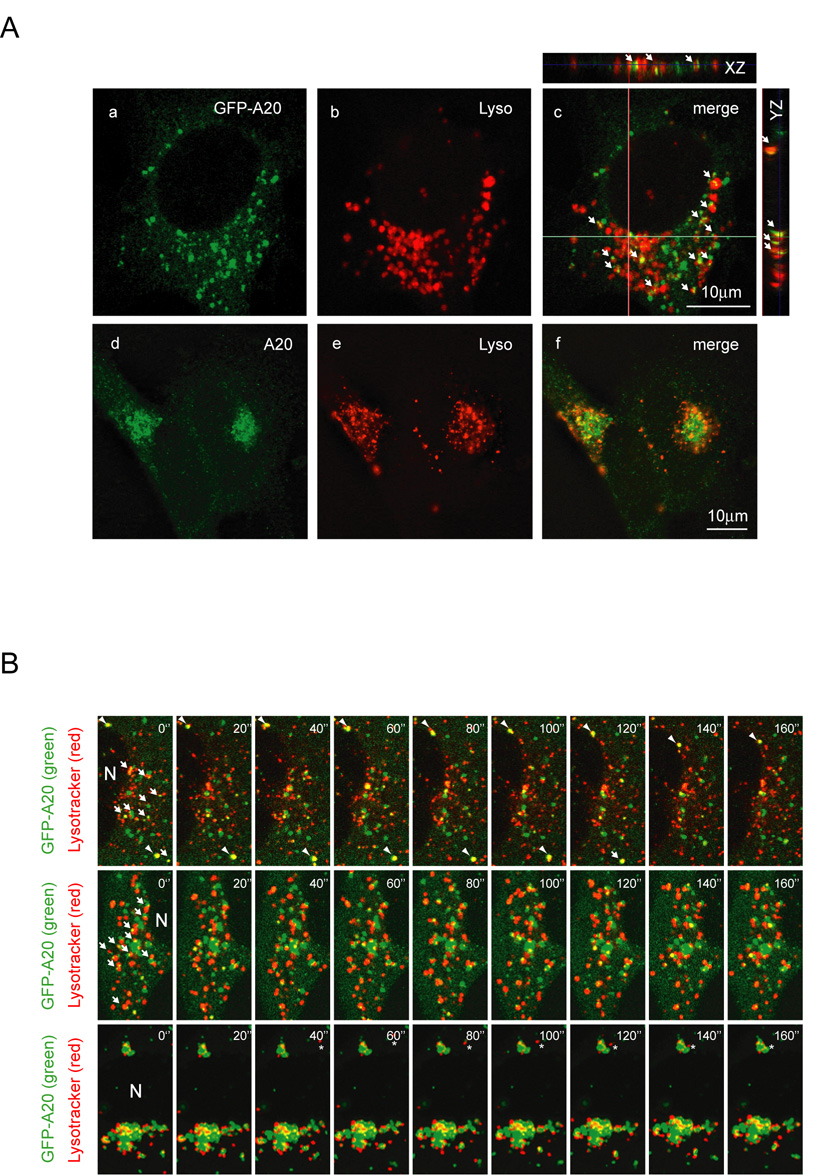

To determine the precise localization of A20, we performed co-immunofluorescence experiments using markers for various subcellular organelles. These experiments suggested that A20 was not localized in the ER or Golgi (Fig. 3A). In contrast, when COS7 cells expressing GFP-A20 were stained with FM4-64, a dye that labeled all endocytic compartments, A20-containing vesicles were co-localized precisely with a fraction of the FM4-64 positive vesicles (Fig. 3B). Since A20-containing vesicles did now show significant colocalization with early endosomes that were positive for EEA1 staining (Li, L. and Ye, Y., unpublished data), A20 was likely localized to an endocytic compartment that represented late endosomes. Consistent with this view, many A20-containing vesicles appeared to be tethered to vesicles that could be stained with Lysotracker, a lysosome specific dye (Fig. 4A, panels a–c), resulting in partial overlapping of the two compartments. This was detected in all horizontal sections of cells by laser scanning confocal microscopy. The interaction between the lysosome and A20-containing vesicles was also observed for endogenous A20, as A20-positive vesicles and the lysosome were co-enriched in a perinuclear region in HeLa cells (Fig. 4A, d–f).

Figure 3. Localization of A20 to an endocytic compartment.

(A) A20 is not localized to either the ER or Golgi. COS7 cells expressing CFP-tagged A20 together with YFP-tagged markers for either the ER or Golgi were imaged. (B) Localization of A20 to an endocytic compartment. COS7 cells expressing GFP-A20 were stained with FM4-64 and imaged. Shown are horizontal sections of two A20 expressing cells stained with FM4-64.

Figure 4. Interaction of A20-containing vesicles with the lysosome.

(A) (a–c) Colocalization of GFP-A20 with the lysosome. COS7 cells expressing GFP-tagged A20 (green) were stained with Lysotracker (red). Images were obtained with a laser scanning confocal microscope. The smaller panels show vertical sections along the XZ and YZ axes indicated by the lines. Arrows highlight some examples of A20-containing vesicles that are either colocalized or tethered with the lysosome. (d–f) Partial colocalization of endogenous A20 with the lysosome. HeLa cells treated with TNFα for 6 hours were stained with an anti-A20 antibody (green) and Lysotracker (Lyso, red). Shown is a deconvoluted horizontal section obtained with an Axiovert fluorescence microscope. (B) Co-migration of A20-containing vesicles with the lysosomal vesicles. COS7 cells expressing GFP-tagged A20 were stained with Lysotracker, and imaged in real time by a laser scanning confocal microscope in the interlace mode (see online supplemental material for the movies). Shown are three examples representing A20 vesicles of different size. Arrows highlight some examples of A20-containing structures (green) that interact with the lysosome (red). Arrowheads in the top panels indicate one example of an A20 vesicle that co-migrates with a lysosome. Asterisks in the bottom panels indicate a lysosomal vesicle that is being targeted to an A20-containing membrane compartment. N, nuclei.

To further assess the interaction between A20-containing vesicles and the lysosome, we used time-lapse confocal microscopy to monitor the movement of these two compartments in cells in real time. The experiments showed that the two compartments apparently communicated in some fashion as many A20-containing vesicles co-migrated with lysosomes over long distances (Fig. 4B). Close examination of these movies revealed that some A20-containing vesicles appeared to fuse with the associated lysosomal vesicles after interacting with them for prolonged periods of time, resulting in transient overlap of the two signals.

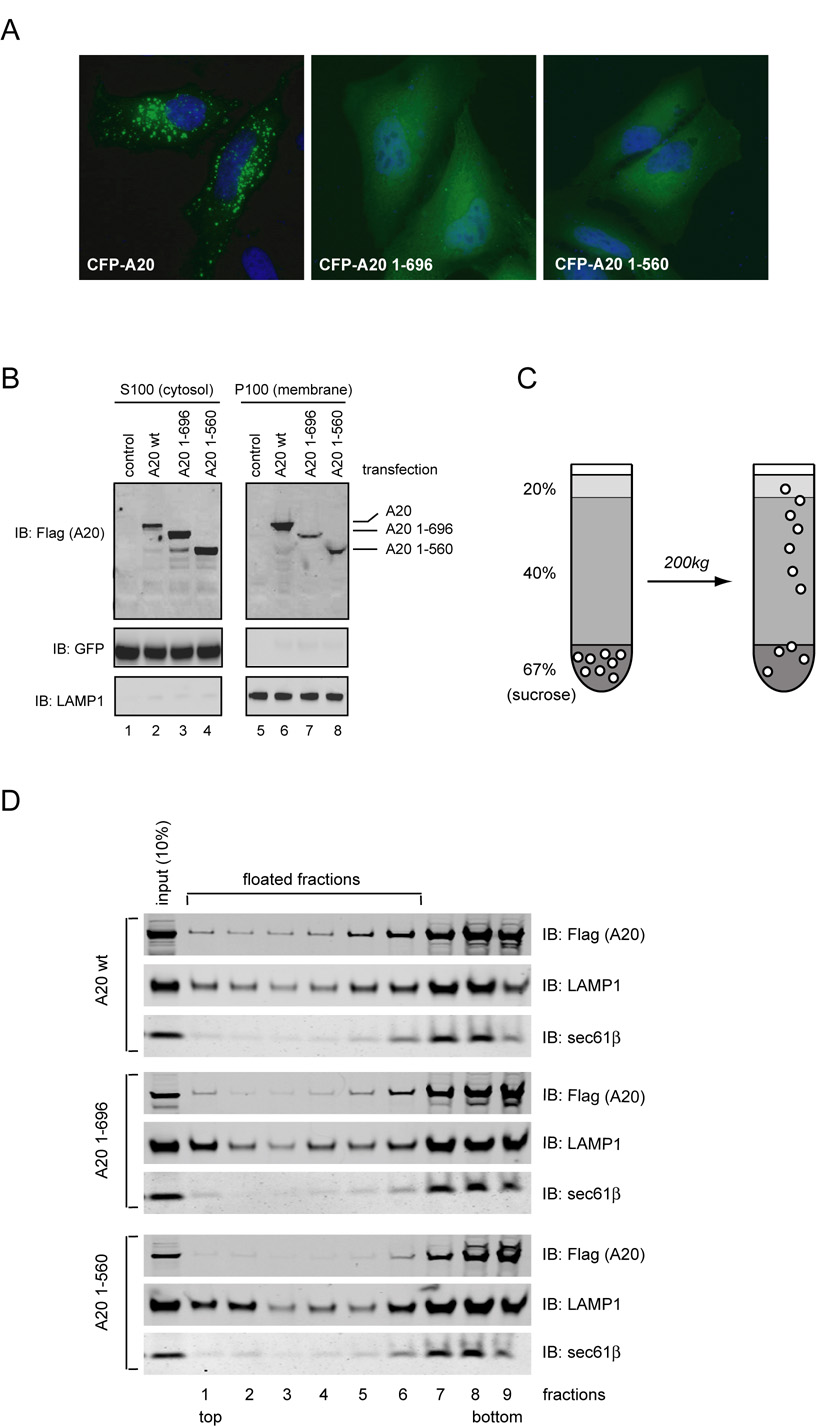

Lysosome-associated localization of A20 requires its carboxy terminal zinc fingers

To understand how A20 interacts with membranes, we studied the localization of several A20 mutants used both imaging and biochemical fractionation approaches. We first generated A20 mutants that lacked either the last two (A20 1–696) or the last four zinc finger domains (A20 1–560) and expressed them in HeLa cells as CFP fusion proteins. Unlike wild type A20, these mutants were mostly localized to the cytosol (Fig. 5A). Fractionation experiments revealed an increase in the level of these zinc finger-deleted A20 mutants in the cytosolic fraction with a compensatory decrease in the membrane fraction when compared with wild type A20 (Fig. 5B, lanes 7, 8 vs. lane 6). We next used a membrane floatation assay to further assess the membrane association of A20. To this end, microsomes isolated from 293T cells expressing A20 variants were resuspended in a buffer containing a high concentration of sucrose. The membranes were placed underneath two layers of solutions that each contains a different concentration of sucrose (Fig. 5C). When the sample was subjected to centrifugation, a sucrose gradient was formed and membrane vesicles would migrate within the gradient to reach a position according to their density [37]. Indeed, many LAMP1 containing lysosomal vesicles were able to float to various levels, which might reflect their heterogeneity in density. A fraction of wild type A20 also floated in a similar fashion. In contrast, the bulk of the rough ER membranes remained at the bottom of the gradient due to the binding of ribosomes (Fig. 5D, top panels). These results suggest that the co-sedimentation of A20 with microsomes is indeed a result of its association with membranes. Because not all lysosomal vesicles were able to float, it was difficult to accurately measure the relative amount of lysosome-associated A20 for different A20 variants in this experiment. Nonetheless, the defect in membrane association for A20 1–560 was obvious as little A20 1–560 was detected in the floated fractions (Fig. 5D). A fraction of A20 1–696 was found in association with membranes (Fig. 5D). However, because cells expressing A20 1–696 contained fewer A20 speckles as judged by immunofluorescence experiment, we concluded that the ability of A20 1–696 to associate with the lysosome was dramatically inhibited.

Figure 5. Membrane association of A20 involves its carboxy terminal zinc finger domains.

(A) The membrane localization of A20 requires its carboxy terminal zinc finger domains. Shown are HeLa cells expressing the indicated CFP-tagged A20 variants (green). Nuclei were counter-stained with DAPI (blue). (B) 293T cells transfected with a GFP expressing plasmid together with constructs expressing the indicated A20 variants were lysed in a hypotonic buffer and fractionated as described in the materials and methods. The proteins in the membrane pellet fraction (P100) and the cytosol (S100) were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. Note that the loading of the supernatant fraction is equivalent to ~10% of the pellet fraction. (C) Scheme of the membrane floatation experiment shown in (D). (D) Membrane association of A20 variants examined by a membrane floatation assay. Fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with antibodies to the indicated proteins.

Since a previous study showed that the action of A20 in NFκB signaling involved its OTU domain-dependent deubiquitinating function as well as its ubiquitin ligase activity, we determined whether the membrane association of A20 required these ubiquitin-modifying activities. We mutated the two conserved cysteine residues in the fourth zinc finger motif of A20. The resulting mutant (A20 Znf4C2) was defective in assembly of ubiquitin chains (Fig. S1A). We also generated a deubiquitinating defective A20 mutant (A20 C103A) according to the published results [26, 27]. When these mutants were analyzed for their ability to associate with membranes, a significant portion of these proteins was detected in the membrane pellet similar to wild type A20 (Fig. S1B). Immunofluorescence experiments also revealed that these mutants were able to associate with the peri-nuclear vesicles (data not shown). Collectively, these results indicate that the lysosome association of A20 is independent of its ubiquitin-modifying activities.

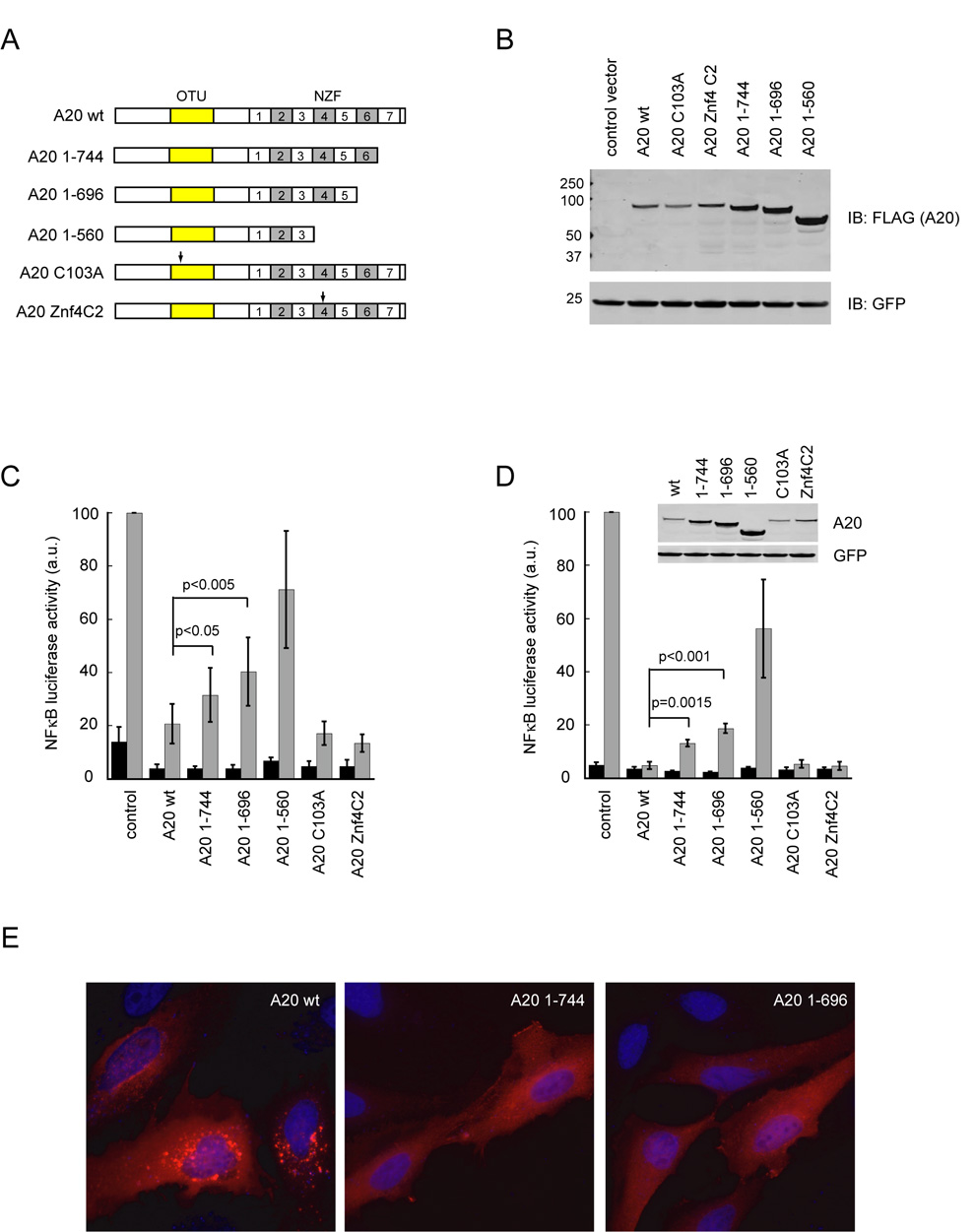

NFκB inhibiting activity of A20 mutants

We next analyzed the NFκB inhibitory activity of various A20 mutants. Interestingly, A20 mutants lacking either ubiquitin ligase (Znf4C2) or deubiquitinating activities (C103A) were as effective as wild type A20 in terminating TNFα induced NFκB signaling as indicated by a NFκB luciferase reporter assay. On the other hand, A20 mutants defective in membrane association (A20 1–696 and A20 1–560) exhibited reduced activity in downregulating NFκB signaling in both 293T and primary mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEF) (Fig. 6). These findings indicate that the membrane association of A20 but not the ubiquitin modifying activity may be critical for the NFκB inhibitory function of A20 at least under the condition of A20 overexpression. This conclusion is in full agreement with previous findings that A20 mutants lacking domains (either the OTU or the fourth zinc finger domain) essential for its ubiquitin modifying activities are as active as wild type A20 in a similar NFκB reporter assay [21, 26, 31, 32], and that the deletion of the last zinc finger domain is associated with significant loss in A20 activity [31].

Figure 6. Inhibition of TNFα-mediated NFκB activation by A20 variants.

(A) Schematic representation of the A20 constructs. Arrows indicate the position of point mutations. (OTU, ovarian tumor; NZF, Npl4 zinc finger) (B) Expression of A20 variants in 293T cells. A GFP expressing construct was co-transfected as a control. (C) NFκB inhibiting activity of A20 variants in 293T cells. Luciferase activity in extracts of TNFα- stimulated 293T cells expressing a NFκB luciferase reporter together with the indicated A20 variants were measured and normalized by the level of co-expressed GFP. Error bars show s.d. (n=6). (D) NFκB inhibiting activity of the A20 variants in primary embryonic fibroblast cells. The inset shows the expression of the A20 variants. Error bars show s.d. (n=3). (E) Membrane localization of A20 requires the last zinc finger domain. HeLa cells expressing the indicated Flag-tagged A20 variants were stained with anti-Flag antibody (red). Nuclei were counter-stained with DAPI (blue).

To further reconcile our findings with the published data, we generated an additional A20 mutant that lacked solely the last zinc finger (A20 1–744). Immunofluorescence experiment demonstrated that A20 1–744 was indeed defective in membrane association because few A20 containing vesicles were observed in cells expressing this mutant (Fig. 6E). Functionally, the A20 1–744 mutant exhibited a small but statistically significant decrease in NFκB inhibitory activity when compared to wild type A20 (Fig. 6C, D). Moreover, further deletion of additional A20 zinc finger domains was associated with a progressive loss in A20 activity, consistent with a previous report [31]. It should be noted that since zinc finger-deleted A20 mutants were consistently expressed at higher levels than wild type A20 (Fig. 6B, D), their inhibitory activity may be overestimated in these luciferase reporter experiments. Consistent with this notion, a similar set of A20 mutants generated by Natoli and colleagues was reported to be more severely impeded in their function in HeLa cells. It is conceivable that experimental designs including the cell line and method used to achieve A20 overexpression may affect the level of membrane association for a given A20 mutant, which may lead to different degree of loss-of-function under various experimental conditions. In support of this view, membrane floatation experiment showed that a fraction of the A20 1–744 mutant was indeed bound to membranes similar to A20 1–696 in 293T cells (data not shown). Together, the data show that deletion of the last zinc finger of A20 concurrently reduces its membrane association and its NFκB inhibitory activity. We therefore conclude that the A20- mediated NFκB inhibitory function may involve a membrane-associated process under certain conditions.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that a fraction of A20 is associated with an endocytic compartment that communicates with the lysosome. First, immunofluorescence experiments reveal that a fraction of endogenous and ectopically expressed A20 is colocalized with FM4-64 positive vesicles near the nuclei. These vesicles exhibit partial co-localization with the lysosome. Second, biochemical fractionation experiment further confirms the localization of a fraction of A20 in a membrane compartment. Finally, dynamic interaction between A20-containing vesicles and lysosomes was observed by time-lapse confocal microscopy.

We further show that the membrane association of A20 requires its carboxy terminal zinc finger domains, but is independent of its ubiquitin modifying activities. Intriguingly, we found that A20 mutants defective in membrane association also contain reduced NFκB inhibiting activities in both 293T and primary mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. These observations indicate that lysosome-associated A20 may participate in regulation of NFκB signaling under certain conditions.

A previous report showed that A20 can target RIP1 for degradation by the proteasome to inhibit NFκB activity in a mouse MEF cell line. This process requires both the ubiquitin ligase and deubiquitinating activities of A20 [27]. However, we find that these ubiquitin modifying activities of A20 is dispensable for its NFκB inhibitory function in several cell lines tested under the condition of A20 overexpression. Our findings fully agree with several other reports, which demonstrated that A20 mutants lacking the ubiquitin modifying functions still possess significant NFκB inhibitory activity in many types of cells [21, 26, 31, 32]. The luciferase reporter assays used in these studies are similar, but the cell line and method chosen to achieve A20 expression are different, which may account for the abovementioned discrepancy. These distinct observations made under various experimental conditions seem to suggest that A20 may be able to operate by at least two independent mechanisms, and a ubiquitin independent process can contribute to A20 regulated NFκB signaling, which likely involves the lysosomes at least under certain experimental conditions.

How lysosome-associated A20 regulates NFκB signaling is currently unknown. One attractive idea is that A20 may target certain signaling molecules to the lysosome for degradation, which may lead to termination of NFκB signaling. In support of this view, a recent study demonstrated that the termination of Toll-like receptor-induced NFκB signaling involves Rab7b, a GTPase that is also localized to a lysosome-associated compartment similar to A20 [38]. We have investigated a few candidates including RIP1 and TRAF2 since previous studies suggested that these proteins interact with A20 [21, 27]. However, our data suggest that the endogenous level of both RIP1 and TRAF2 is not significantly downregulated in cells under condition of either TNFα stimulation or A20 overexpression (data not shown), which is consistent with previous reports [27, 39]. Thus, a complete survey of signaling molecules of NFκB pathway is required to identify potential A20 substrates that may undergo lysosome dependent degradation upon TNFR activation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Geras-Raaka Elizabeth for initial assistance with the confocal microscopy, Jeannette Hüebener and Olaf Rieβ (University of Tübingen) for primary mouse MEF cells, William Tsoi for making the pEYFP-A20 plasmid, Michael Krause, Zheng-Gang Liu, Jonathan Ashwell, and Harris Bernstein for critical reading of the manuscript. The research is supported by an intramural research program at NIDDK in the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chen G, Goeddel DV. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science. 2002;296:1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karin M, Greten FR. NF-kappaB: linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:749–759. doi: 10.1038/nri1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karin M, Lin A. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:221–227. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dempsey PW, Doyle SE, He JQ, Cheng G. The signaling adaptors and pathways activated by TNF superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:193–209. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu H, Huang J, Shu HB, Baichwal V, Goeddel DV. TNF-dependent recruitment of the protein kinase RIP to the TNF receptor-1 signaling complex. Immunity. 1996;4:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu H, Shu HB, Pan MG, Goeddel DV. TRADD-TRAF2 and TRADD-FADD interactions define two distinct TNF receptor 1 signal transduction pathways. Cell. 1996;84:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80984-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu H, Xiong J, Goeddel DV. The TNF receptor 1-associated protein TRADD signals cell death and NF-kappa B activation. Cell. 1995;81:495–504. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothe M, Wong SC, Henzel WJ, Goeddel DV. A novel family of putative signal transducers associated with the cytoplasmic domain of the 75 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell. 1994;78:681–692. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanger BZ, Leder P, Lee TH, Kim E, Seed B. RIP: a novel protein containing a death domain that interacts with Fas/APO-1 (CD95) in yeast and causes cell death. Cell. 1995;81:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh WC, Shahinian A, Speiser D, Kraunus J, Billia F, Wakeham A, de la Pompa JL, Ferrick D, Hum B, Iscove N, Ohashi P, Rothe M, Goeddel DV, Mak TW. Early lethality, functional NF-kappaB activation, and increased sensitivity to TNF-induced cell death in TRAF2-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;7:715–725. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SY, Reichlin A, Santana A, Sokol KA, Nussenzweig MC, Choi Y. TRAF2 is essential for JNK but not NF-kappaB activation and regulates lymphocyte proliferation and survival. Immunity. 1997;7:703–713. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Minemoto Y, Lin A. c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase 1 (JNK1), but not JNK2, is essential for tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced c-Jun kinase activation and apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10844–10856. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10844-10856.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Natoli G, Costanzo A, Ianni A, Templeton DJ, Woodgett JR, Balsano C, Levrero M. Activation of SAPK/JNK by TNF receptor 1 through a noncytotoxic TRAF2-dependent pathway. Science. 1997;275:200–203. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papa S, Zazzeroni F, Pham CG, Bubici C, Franzoso G. Linking JNK signaling to NF-kappaB: a key to survival. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5197–5208. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beyaert R, Heyninck K, Van Huffel S. A20 and A20-binding proteins as cellular inhibitors of nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent gene expression and apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1143–1151. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Opipari AW, Jr, Boguski MS, Dixit VM. The A20 cDNA induced by tumor necrosis factor alpha encodes a novel type of zinc finger protein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14705–14708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Opipari AW, Jr, Hu HM, Yabkowitz R, Dixit VM. The A20 zinc finger protein protects cells from tumor necrosis factor cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12424–12427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eliopoulos AG, Blake SM, Floettmann JE, Rowe M, Young LS. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 activates the JNK pathway through its extreme C terminus via a mechanism involving TRADD and TRAF2. J Virol. 1999;73:1023–1035. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1023-1035.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heyninck K, Beyaert R. The cytokine-inducible zinc finger protein A20 inhibits IL-1-induced NF-kappaB activation at the level of TRAF6. FEBS Lett. 1999;442:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaattela M, Mouritzen H, Elling F, Bastholm L. A20 zinc finger protein inhibits TNF and IL-1 signaling. J Immunol. 1996;156:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song HY, Rothe M, Goeddel DV. The tumor necrosis factor-inducible zinc finger protein A20 interacts with TRAF1/TRAF2 and inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6721–6725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper JT, Stroka DM, Brostjan C, Palmetshofer A, Bach FH, Ferran C. A20 blocks endothelial cell activation through a NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18068–18073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee EG, Boone DL, Chai S, Libby SL, Chien M, Lodolce JP, Ma A. Failure to regulate TNF-induced NF-kappaB and cell death responses in A20-deficient mice. Science. 2000;289:2350–2354. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang YY, Li L, Han KJ, Zhai Z, Shu HB. A20 is a potent inhibitor of TLR3- and Sendai virus-induced activation of NF-kappaB and ISRE and IFN-beta promoter. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boone DL, Turer EE, Lee EG, Ahmad RC, Wheeler MT, Tsui C, Hurley P, Chien M, Chai S, Hitotsumatsu O, McNally E, Pickart C, Ma A. The ubiquitin-modifying enzyme A20 is required for termination of Toll-like receptor responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1052–1060. doi: 10.1038/ni1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans PC, Ovaa H, Hamon M, Kilshaw PJ, Hamm S, Bauer S, Ploegh HL, Smith TS. Zinc-finger protein A20, a regulator of inflammation and cell survival, has de-ubiquitinating activity. Biochem J. 2004;378:727–734. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wertz IE, O'Rourke KM, Zhou H, Eby M, Aravind L, Seshagiri S, Wu P, Wiesmann C, Baker R, Boone DL, Ma A, Koonin EV, Dixit VM. De-ubiquitination and ubiquitin ligase domains of A20 downregulate NF-kappaB signalling. Nature. 2004;430:694–699. doi: 10.1038/nature02794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin SC, Chung JY, Lamothe B, Rajashankar K, Lu M, Lo YC, Lam AY, Darnay BG, Wu H. Molecular Basis for the Unique Deubiquitinating Activity of the NF-kappaB Inhibitor A20. J Mol Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komander D, Barford D. Structure of the A20 OTU domain and mechanistic insights into deubiquitination. Biochem J. 2008;409:77–85. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heyninck K, Beyaert R. A20 inhibits NF-kappaB activation by dual ubiquitin-editing functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Natoli G, Costanzo A, Guido F, Moretti F, Bernardo A, Burgio VL, Agresti C, Levrero M. Nuclear factor kB-independent cytoprotective pathways originating at tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31262–31272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klinkenberg M, Van Huffel S, Heyninck K, Beyaert R. Functional redundancy of the zinc fingers of A20 for inhibition of NF-kappaB activation and protein-protein interactions. FEBS Lett. 2001;498:93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang J, Teng L, Li L, Liu T, Li L, Chen D, Xu LG, Zhai Z, Shu HB. ZNF216 Is an A20-like and IkappaB kinase gamma-interacting inhibitor of NFkappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16847–16853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Tu D, Brunger AT, Ye Y. A ubiquitin ligase transfers preformed polyubiquitin chains from a conjugating enzyme to a substrate. Nature. 2007;446:333–337. doi: 10.1038/nature05542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye Y, Shibata Y, Yun C, Ron D, Rapoport TA. A membrane protein complex mediates retro-translocation from the ER lumen into the cytosol. Nature. 2004;429:841–847. doi: 10.1038/nature02656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vincenz C, Dixit VM. 14-3-3 proteins associate with A20 in an isoform-specific manner and function both as chaperone and adapter molecules. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20029–20034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker WC, Weber T, Chapman ER. Reconstitution of Ca2+-regulated membrane fusion by synaptotagmin and SNAREs. Science. 2008 doi: 10.1126/science.1097196. Epub. ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Chen T, Han C, He D, Liu H, An H, Cai Z, Cao X. Lysosome-associated small Rab GTPase Rab7b negatively regulates TLR4 signaling in macrophages by promoting lysosomal degradation of TLR4. Blood. 2007;110:962–971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-066027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Legler DF, Micheau O, Doucey MA, Tschopp J, Bron C. Recruitment of TNF receptor 1 to lipid rafts is essential for TNFalpha-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Immunity. 2003;18:655–664. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.