Abstract

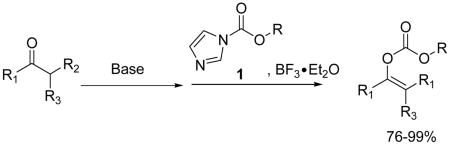

A convenient access to substituted allyl enol carbonates was established through the reaction of ketone enolates with the complex of allyl 1H-imidazole-1-carboxylates and boron trifluoride etherate.

Allyl enol carbonates and allyl β-keto esters have received more and more attention as useful precursors in the palladium catalyzed synthesis of enantiomeric enriched α-allyl ketones, which are important building blocks in asymmetric organic synthesis.1 The preparation of allyl enol carbonates and allyl β-keto esters can be performed by the treatment of the corresponding enolates with an acylating agent, usually allyl chloroformate.2 However, very few substituted allyl chloroformates are commercially available and the preparation3 of such compounds is limited not only by their poor thermal stability and the use of excess highly toxic phosgene but also by the hydrogen chloride generated from the reaction, which may not be compatible with acid-sensitive function groups on the molecule. Furthermore, the higher reactivity of the allyl enol carbonates and the frequently low yields in their synthesis with more highly substituted allyl chloroformates focused our attention on developing a convenient high yielding process. In addition, although substituted allyl β-keto esters can be more readily synthesized by ester exchange reactions of simple β-keto esters with the corresponding allyl alcohol,4 there is still an absence of a convenient procedure for the preparation of substituted allyl enol carbonates from simple ketones. Notably the role of allyl β-keto esters and that of allyl enol carbonates are not completely exchangeable in the Pd catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation reactions.5 Therefore, the development of a convenient approach to access substituted allyl enol carbonates will significantly broaden the scope of the asymmetric synthesis of α-allyl ketones.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

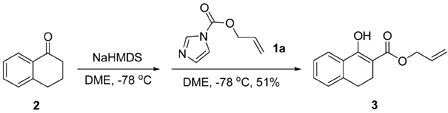

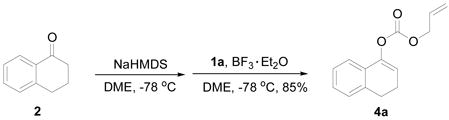

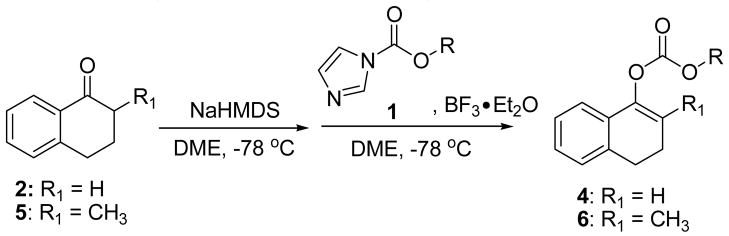

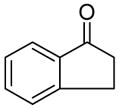

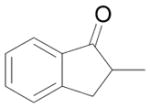

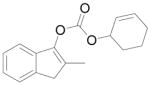

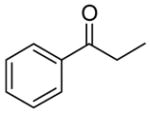

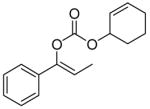

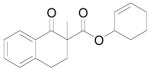

The regioselectivity in the acylation of metal enolates in general is dependent on the acylating reagent (acetic anhydride favors O-acylation better than acetyl chloride), the metal (K favors O- acylation while Mg favors C-acylation), the solvent (chelating solvent such as 1,2-dimethoxyethane favors O-acylation while non-polar solvent such as toluene favors C-acylation), and the reaction temperature (higher temperature favors O-acylation while lower temperature favors C-acylation).6 Imidazolides have been widely used in the acylation7a of alcohols7b, amines7c, acids7d and carbanions.7e The reaction of ketone enolates with imidazolides favors C-acylation and it is a better alternative to the Claisen condensation to synthesize β-keto esters and 1,3-diketones.8 As we expected, treatment of the sodium enolate of 1-tetralone in DME at −78 °C with allyl 1H-imidazole-1-carboxylate 1a gave only C-acylation product 3 (eq. 1). It is a general notion that reaction of ketone enolates with “hard” electrophiles favor O-acylation while “soft” electrophiles favor C-acylation.6 We postulated that the complex of the imidazolide with an azaphilic Lewis acid, such as boron trifluoride, is a “harder” electrophile than the imidazolide itself and it should favor O-acylation better. 9 To our delight, the experimental result supported our proposal and in contrast to eq. 1, the reaction mediated with BF3·Et2O cleanly generated only allyl enol carbonate 4a in 85% yield (eq. 2).

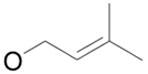

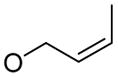

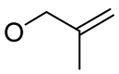

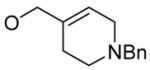

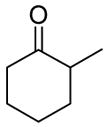

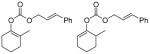

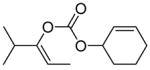

To investigate the generality of the reaction, we prepared several substituted allyl 1H-imidazole-1-carboxylates 1 by simply mixing 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole with the corresponding allylic alcohols in a co-solvent of THF and CH2Cl2 at 0 °C for several hours and then isolated the product by silica gel column chromatography. The yields are normally very good (Table 1). As a demonstration, the sodium enolate of 1-tetralone or 2-methyl-1-tetralone was treated with a variety of the BF3 complexes of differently substituted allyl derivatives 1 respectively, and consistently good yields were obtained in every case. It is remarkable that, through this procedure, enol carbonates containing amino groups could be produced in the same manner (Table 1, entry 10).

TABLE 1.

Formation of Allyl Enol Carbonates from Various Substituted Allyl 1H-imidazole-1-carboxylates

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | OR | Yield of 1a | Ketone | Product | Yield |

| 1 |

|

1b

80% |

2 | 4b | 88% |

| 2 | 5 | 6b | 99% | ||

| 3 |

|

1c

91% |

2 | 4c | 76% |

| 4 | 5 | 6c | 76% | ||

| 5 |

|

1d

97% |

2 | 4d | 80% |

| 6 | 5 | 6d | 94% | ||

| 7 |

|

1e

85% |

5 | 6e | 89% |

| 8 |

|

1f

95% |

5 | 6f | 96% |

| 9 |

|

1g

97% |

5 | 6g | 92% |

| 10 |

|

1h

100% |

5 | 6h | 76% |

Isolated yields of 1 from the reaction of 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole and the corresponding allyl alcohol.

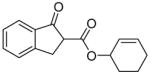

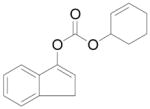

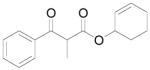

The reaction of various sodium enolates with the BF3 complex of 1 exclusively gave enol carbonates in high yields (Table 2, entry 7, 9 and 11), while the ones without BF3 gave exclusively β-keto esters in Table 2, entry 1 and 6, or a mixture of both in entry 8, possibly because the steric effect of the methyl group disfavored the C-acylation. There are also some cases in which the nature of the enolate is such that the regioselectivity towards the O-acylation is not perfect even with the BF3 activated electrophile. For instance, the reaction of the sodium enolate of 1-indanone with the 1d-BF3 complex in DME at −78 °C yielded a mixture of enol carbonate 8 and β-keto ester 7 in a 3:1 ratio (Table 2, entry 2). By switching to the less coordinated potassium enolate, generated by use of potassium tert-butoxide as base, the ratio improved to 17:1 (Table 2, entry 3). In the presence of 18-C-6, the enolate has even weaker coordination with the potassium counter-cation, and in this case no 7 was observed (Table 2, entry 4). Since the reactions between enolates and 1-BF3 complex are fast even at −78 °C, either the thermodynamic (such as 13 in entry 9) or the kinetic product (such as 15 in entry 10) can be obtained with excellent selectivity by quenching the corresponding enolates generated using different conditions. Substrates 16 and 17 have been used in the formal synthesis of (S)-oxybutynin and they can be alternatively prepared by this method (Table 2, entry 11).1d

TABLE 2.

The Reaction of Various Ketone Enolates with 1 or Its BF3 Complex

| Entry | Ketone | Procedurea | Product | Yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

A |

7 |

63% |

| 2 | B |

8 + 7 (8:7 = 3:1) |

95% | |

| 3 | C | 8 + 7 (17:1) | 92% | |

| 4 | D | 8 only | 92% | |

| 5 |

|

C |

9 |

88% |

| 6 |

|

A |

10 |

61% |

| 7 | B |

11 |

99% | |

| 8 |

|

A |

12 + 4d (12:4d = 1.3:1) |

51% |

| 9 |

|

Bc |

|

99% |

| 10 |

|

C |

|

93% |

| 11 |

|

B |

|

78% |

A: 1.0 equiv. NaHMDS, DME, −78 °C, then 0.8 equiv. 1; B: 1.0 equiv. NaHMDS, DME, −78 °C, then mixture of 0.8 equiv. 1 and BF3·Et2O or, if the product can not be separated from the starting ketone by silica gel chromatography, 1.2 equiv. NaHMDS, DME, −78 °C, then mixture of 1.2 equiv. 1 and BF3·Et2O; C: 1.2 equiv. KOtBu, THF, −78 °C, then mixture of 1.2 equiv. 1 and BF3·Et2O; D: 1.2 equiv. KOtBu, 1.2 equiv. 18-crown-6, THF, −78 °C, then mixture of 1.2 equiv. 1 and BF3·Et2O.

Combined isolated yield for the reactions with more than one product.

The enolate was formed by the addition of a solution of 1 equiv. of NaHMDS into a solution of the substrate at 0 °C then cooled to −78 °C.

In summary, allyl 1H-imidazole-1-carboxylates are readily accessible from 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole and allylic alcohols. They are normally stable and easy to handle. By tuning their reactivity with BF3 in the reaction with ketone enolates, we have developed a convenient procedure for the synthesis of a broad scope of allyl enol carbonates in high yields and regioselectivity. The study of Pd catalyzed asymmetric decarboxylative allylic alkylation reactions of substituted allyl enol carbonates and their application in organic synthesis is ongoing.

Experimental Section

General Procedures

Procedure A

A clean oven-dried 50 mL flask was charged 460 mg sodium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (2.4 mmol) under nitrogen. The flask was cooled to −78 °C in a dry-ice-acetone bath and 5 mL 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME) was added through a syringe. The flask was taken out from the bath to allow it to warm up until the solid completely dissolved. Then it was cooled to −78 °C. To the solution 317 mg 1-indanone (2.4 mmol) was added in 2 mL DME. The solution was stirred for 30 min before it was transferred into the solution of 384.4 mg 1d (2 mmol). After 10 min the cooling bath was removed and the reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred at room temperature for 1 h. One portion of 10 mL saturated aqueous ammonium chloride was poured into the reaction mixture followed by 10 mL diethyl ether. The aqueous layer was extracted with 10 mL diethyl ether. The combined organic solution was washed with 10 mL saturated brine and dried over MgSO4. After concentration the crude product was isolated with silica gel column chromatography eluted with 15% diethyl ether in petroleum ether to afford 323 mg white solid as a 5:1 mixture of 7 and its enol tautomer (63%). M.p. = 77–79 °C; Rf = 0.24 (Diethyl ether/petroleum ether 1:9); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 10.45 (bs, 1H, enol), 7.77 (m, 1H, ketone), 7.62 (m, 1H, enol), 7.62 (m, 1H, ketone), 7.50 (m, 1H, ketone), 7.45 (m, 1H, enol), 7.39 (m, 2H, enol), 7.39 (m, 1H, ketone), 5.98 (m, 1H, enol), 5.98 (m, 1H, ketone), 5.81 (m, 1H, enol), 5.74 (m, 1H, ketone), 5.47 (m, 1H, enol), 5.35 (m, 1H, ketone), 3.71 (m, 1H, ketone), 3.55 (m, 1H, ketone), 3.55 (m, 2H, enol), 3.38 (m, 1H, ketone), 3.38 (m, 1H, enol), 2.20-1.60 (m, 6H, ketone), 2.20-1.60 (m, 6H, enol);

Procedure B

To the solution of 460 mg NaHMDS in 5 mL DME at −78 °C, 292 mg 1-tetralone (2 mmol) was added in 2 mL DME. The solution was stirred at −78 °C for 30 min. Meanwhile, another clean oven-dried 50 mL flask was charged with 365 mg 1a (2.0 mmol) and 5 mL DME. The solution was cooled to −78 °C, and was added 0.30 mL boron trifluoride etherate (2.4 mmol) dropwise and stirred for 15 min. The above solution was transferred into the solution of enolate through a cannula under nitrogen and stirred for 30 min. One portion of 10 mL saturated aqueous ammonium chloride was poured into the reaction mixture followed by 10 mL diethyl ether. The mixture was taken out from the bath and allowed to warm to ambient temperature. The organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer was extracted once with 10 mL diethyl ether. The organic layer was combined and dried over magnesium sulfate. After filtration and concentration in vacuo the crude material was purified by silica gel column chromatography eluted with 10% diethyl ether in petroleum ether to give 392 mg 4a as colorless liquid (85%). Rf = 0.39 (Diethyl ether/petroleum ether 1:9); IR (film): 3068, 3024, 2941, 2890, 2836, 1760, 1659, 1489, 1452, 1428, 1360, 1293, 1244, 1225, 1186, 1013, 993, 944, 772, 744 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.2 (m, 4H), 5.99 (m, 1H), 5.81 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 5.42 (dq, J = 17.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 5.32 (dq, J = 10.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 4.71 (dt, J = 5.6, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 2.86 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 2.45 (m, 2H).

Procedure C

Follow the details in Procedure B but potassium tert-butoxide was used as base and THF as solvent.

Cyclohex-2-en-1-yl 2-methyl-1H-inden-3-yl carbonate (9)

Starting from 350 mg 2-methyl-1-indanone (2.4 mmol) and 384.4 mg 1d (2 mmol) by procedure C, 474 mg white solids were obtained after purification by silica gel chromatography (88%). M.p. = 66–67 °C; Rf = 0.30 (Diethyl ether/petroleum ether 1:9); IR (film): 3034, 2944, 1756, 1656, 1397, 1336, 1242, 1165, 1140, 1033, 911, 732 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.34 (m, 1H), 7.25 (m, 1H), 7.15 (m, 2H), 6.05 (m, 1H), 5.87 (m, 1H), 5.23 (m, 1H), 3.32 (s, 2H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 2.20-1.60 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 152.4, 144.6, 140.1, 139.6, 134.0, 128.3, 126.3, 124.6, 123.8, 117.3, 112.6, 73.1, 39.1, 28.2, 24.9, 18.6, 12.2.

Procedure D

Follow Procedure C but 18-C-6 was added to the enolate solution.

Cyclohex-2-en-1-yl 1H-inden-3-yl carbonate (8)

Starting from 317 mg 1-indanone (2.4 mmol) and 384.4 mg 1d (2 mmol) by procedure D, 470 mg colorless oil was obtained after purification by silica gel chromatography (92%). Rf = 0.47 (Diethyl ether/petroleum ether 1:9); IR (film): 3034, 2943, 2835, 1756, 1618, 1603, 1578, 1456, 1398, 1336, 1292, 1227, 1172, 1127, 1050, 1012, 918,782, 760, 717 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.41 (m, 2H), 7.30 (m, 1H), 7.24 (m, 1H), 6.34 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.04 (m, 1H), 5.86 (m, 1H), 5.25 (m, 1H), 3.40 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 2.20-1.60 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 152.3, 149.4, 141.8, 138.7, 134.0, 126.3, 125.7, 124.5, 124.1, 118.2, 114.3, 72.9, 34.9, 28.2, 24.9, 18.6. Anal. Calcd. for C16H16O3: C, 74.98; H, 6.29; Found: C, 75.12; H, 6.11.

Supplementary Material

Full experimental details, spectral data, and characterization for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, General Medical Sciences Grant GM13598, for their generous support of our programs. J. Xu has been supported by Abbott Laboratories Fellowships in the Stanford Graduate Fellowships Program.

References

- 1.For reviews concerning Pd catalyzed decarboxylative asymmetric allylic alkylation of ketone enol carbonates and β-keto esters, see: You SL, Dai LX. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:5346. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601889.Braun M, Meier T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:6952. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602169.Braun M, Meier T. Syn Lett. 2006;5:661. For recent publications, see: Trost BM, Xu J, Markus R. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:282. doi: 10.1021/ja067342a.Schulz SR, Blechert S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:3966. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604553.Behenna DC, Stockdill JL, Stoltz BM. Ang Chem In Ed. 2007;46:4077. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700430.

- 2.(a) Olofson RA, Cuomo J, Bauman BA. J Org Chem. 1978;43:2073. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsuji J, Minami I, Shimizu I. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:1793. [Google Scholar]; (c) Crabtree SR, Chu WLA, Mander LN. Synlett. 1990;3:169. [Google Scholar]; (d) Harwood LM, Houminer Y, Manage A, Seeman JI. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:8027. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Nystrom RF, Brown WG. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;69:1197. [Google Scholar]; (b) Young WG, Clement RA, Shih CH. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:3061. [Google Scholar]; (c) Oliver KL, Young WG. J Am Chem Soc. 1959;81:5811. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert JC, Kelly TA. J Org Chem. 1988;53:449. [Google Scholar]

-

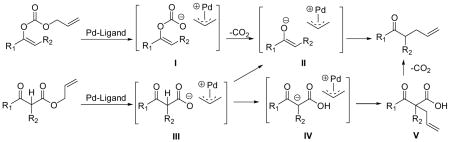

5.In the reaction of Pd catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation of ketones to generate tertiary centers, the reaction mechanisms of allyl enol carbonates and that of allyl β-keto esters may be different: Intermediate I from enol carbonates can only undergo decarboxylation to afford Pd enolate II which recombines to the product. Intermediate III from β-keto esters, however, may undergo a facile H-shift to generate IV depending on the acidity of the α-proton. IV recombines to a β-keto acid V, which decarboxylates to the product. Therefore, allyl β-keto esters can not completely replace enol allyl carbonates in this reaction. See: Tsuji J, Minami I. Acc Chem Res. 1987;20:140.Tsuji J, Yamada Y, Minami I, Yuhara M, Nisar M, Shimizu I. J Org Chem. 1987;52:2988.

- 6.(a) House HO, Auerbach RA, Gall M, Peet NP. J Org Chem. 1973;38:514. [Google Scholar]; (b) Olofson RA, Cuomo J, Bauman BA. J Org Chem. 1978;43:2073. [Google Scholar]; (c) Taylor RJK. Synthesis. 1985;4:364. [Google Scholar]; (d) Bairgrie LM, Leung-Toung R, Tidwell TT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:1673. [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhong M, Brauman JI. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:636. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For review concerning the application of imidazolides as acylating agents, see: Staab HA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1962;7:350.Bertolini G, Pavich G, Vergani B. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6031. doi: 10.1021/jo980286e.Vatele JM. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:4251.Kitagawa T, Kuroda H, Sasaki H. Chem & Pharm Bull. 1987;35:1262.Werner T, Barrett AGM. J Org Chem. 2006;71:4302. doi: 10.1021/jo060562m.

- 8.(a) Moyer MP, Feldman PL, Rapoport H. J Org Chem. 1985;50:5223. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shone RL, Deason JR, Miyano M. J Org Chem. 1986;51:268. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tanaka T, Okamura N, Bannai K, Hazato A. Sugi [Google Scholar]

- 9.For reference concerning the much better reactivity of acylimidazolium salts than the corresponding imidazolides, see: Anders E, Will W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;41:3911.Oakenfull DG, Salvesen K, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:188.Grzyb JA, Shen M, Yoshina-Ishii C, Chi W, Brown RS, Batey RA. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:7153.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full experimental details, spectral data, and characterization for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.