Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) plays a role in neuropathic pain. During neuropathic pain development in the chronic constriction injury model, elevated TNF levels in the brain occur in association with enhanced α2-adrenoceptor inhibition of norepinephrine release. α2-Adrenoceptors are also located on peripheral macrophage where they normally function as pro-inflammatory, since they increase the production of the cytokine TNF, a proximal mediator of inflammation. How the central increase in TNF affects peripheral α2-adrenoceptor function was investigated. Male, Sprague-Dawley rats had four loose ligatures placed around the right sciatic nerve. Thermal hyperalgesia was determined by comparing hind paw withdrawal latencies between chronic constriction injury and sham-operated rats. Chronic constriction injury increased TNF-immunoreactivity at the lesion and the hippocampus. Amitriptyline, an antidepressant that is used as an analgesic, was intraperitoneally administered (10 mg/kg) starting simultaneous with ligature placement (day-0) or at days-4 or -6 post-surgery. Amitriptyline treatment initiated at day-0 or day-4 post-ligature placement alleviated hyperalgesia. When initiated at day-0, amitriptyline prevented increased TNF immunoreactivity in the hippocampus and at the lesion. A peripheral inflammatory response, macrophage production of TNF, was also assessed in the current study. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated production of TNF by whole blood cells and peritoneal macrophages was determined following activation of the α2-adrenoceptor in vitro. α2-Adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production from peripheral immune-effector cells reversed from potentiation in controls to inhibition in chronic constriction injured rats. This effect is accelerated with amitriptyline treatment initiated at day-0 or day-4 post-ligature placement. Amitriptyline treatment initiated day-6 post-ligature placement did not alleviate hyperalgesia and prevented the switch from potentiation to inhibition in α2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production. Recombinant rat TNF i.c.v. microinfusion reproduces the response of peripheral macrophages from rats with chronic constriction injury. A reversal in peripheral α2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production from proto anti-inflammatory is associated with effective alleviation of thermal hyperalgesia. Thus, α2-adrenoceptor regulation of peripheral TNF production may serve as a potential biomarker to evaluate therapeutic regimens.

Keywords: Tumor necrosis factor, α2-adrenoceptor, neuropathic pain, hyperalgesia, rat, macrophage

1. Introduction

By developing a central component, neuropathic pain characterizes a type of chronic pain that can persist long after nerve injury resolution. This central sensitization involves neuroplastic changes at multiple levels of the nervous system (Attal and Bouhassira, 1999; Campbell and Meyer, 2006; Iannetti et al, 2005; Romanelli and Esposito, 2004; Salter, 2004; Suzuki and Dickenson, 2005; Vera-Portocarrero et al, 2006), including decreased release of norepinephrine in the brain (Covey et al, 2000). Stimulation of presynaptic α2-adrenoceptors is a major mechanism of inhibition of norepinephrine release (Dixon et al, 1979). During neuropathic pain, α2-adrenoceptor inhibition of norepinephrine release is enhanced in the brain (Covey et al, 2000), a plausible mechanism contributing to dysregulation of descending noradrenergic modulation of pain (Millan, 2002; Romanelli and Esposito, 2004; Yaksh, 1985). Thus, this neuroplastic change in the brain (decreased norepinephrine release) (Covey et al, 2000; Ignatowski et al, 2005) may lead to compensatory changes in the periphery (increased α2-adrenoceptor expression) (Ma et al., 2004; Perl, 1999) that are observed during neuropathic pain. Similar instances whereby the brain modulates a peripheral inflammatory condition have been noted (Brazzini et al, 2003; Gyires et al, 2007).

Enhanced production of the cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) in the brain (locus coeruleus and hippocampus) occurs during the development of neuropathic pain (Covey et al, 2000; Ignatowski et al, 1999; Spengler et al, 2007). As illustrated in Fig. 1, TNF regulates norepinephrine release in the brain, interdependent upon α2-adrenoceptor activation (Ignatowski and Spengler, 1994). In fact, an interactive relationship exists between the production of TNF and activation of the α2-adrenergic autoreceptor. This interactive relationship is due to α2-adrenergic autoreceptor coupling to specific G-proteins ultimately directing neurotransmitter release. We hypothesize that changes in the production of TNF affect G-proteins that, in turn, directs G-protein coupling of presynaptic receptors that direct norepinephrine release. We predict that high levels of TNF remodel the interactive relationship between neuron sensitivity to TNF and α2-adrenoceptor agonists (including norepinephrine), culminating in a dysregulation of norepinephrine release, directing neuropathic pain (Covey et al, 2000; Ignatowski et al, 1999). Inhibition of the initial injury-induced increase in brain-derived TNF may, therefore, represent an effective treatment for neuropathic pain or prevention of its development following injury to a peripheral nerve.

Fig. 1.

A proposed interactive relationship between levels of TNF and α2-adrenergic autoreceptor (α2-AR) coupling to specific G-proteins directs neurotransmitter release. Changes in the production of TNF affect G-protein expression that, in turn, directs G-protein coupling of presynaptic receptors that direct norepinephrine release. For example, an increase in TNF increases Gαi-proteins, while decreasing TNF has the opposite effect. Thus, an increase in Gαi-proteins favors α2-AR-Gαi-protein coupling when TNF levels are high, while a decrease in Gαi-proteins favors α2-AR-Gαs-protein coupling when TNF levels are low. The α2-AR normally favors coupling to the Gαi subunit, and activation of these inhibitory autoreceptors decreases norepinephrine release from noradrenergic neurons. Activation of the α2-AR coupled to Gαi also inhibits TNF production in the brain. Because TNF normally inhibits norepinephrine release, this reduction in levels of TNF increases norepinephrine release, thus maintaining homeostasis of the levels of bioactive norepinephrine. However, decreases in the levels of TNF switch the functioning of the α2-AR. The α2-AR now exists predominantly as a stimulatory autoreceptor (designated as α2-AR coupled to Gαs), and its activation both facilitates norepinephrine release and increases TNF production. This system remains in check since increased levels of TNF support coupling of the α2-AR to the Gαi subunit. These events continually occur within an equilibrium by which physiologic levels of TNF and normal functioning of the α2-AR are preserved. A pathologic increase in TNF production during chronic pain disrupts the system’s natural balance, such that increased TNF levels are sustained and norepinephrine release remains low, while the α2-AR undergoes a dysfunctional adaptation, disproportionately favoring one functional form (couples to Gαi) over the other (coupling to Gαs) (favoring the ‘left’ or shaded side of model). Conversely, decreasing TNF levels perturbs the system in the opposite fashion; increasing norepinephrine release and returning the α2-AR to a state of functional balance. This is a proposed mechanism by which TNF levels and the α2-AR participate in a reciprocal fashion in the pathogenesis of chronic pain (also chronic stress or depression) and in the therapeutic efficacy of antidepressant drugs. While a switch in α2-AR-G-protein coupling supports the interactive relationship between levels of TNF and α2-AR regulation of norepinephrine release, a switch in α-AR phenotype (α2 to α1) may also occur. α2-AR = α2-adrenoceptor; NE = norepinephrine, TNF = tumor necrosis factor-α.

The hippocampus is classically known for long-term potentiation, underlying learning and memory formation (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Scoville and Milner, 1957). This region is also involved in tonic pain perception and processing painful stimuli (Delgado, 1955; Dutar et al, 1985; Khanna and Sinclair, 1989; McEwen, 2001; McKenna and Melzack, 1992). Additionally, the hippocampus is replete with presynaptic α2-adrenoceptors (Kiss et al, 1995; Scheinin et al, 1994). Concomitant with the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain, α2-adrenoceptor inhibition of norepinephrine release in this limbic region is enhanced (Covey et al, 2000). In this regard, it is not surprising that tricyclic antidepressant drugs that alleviate pain also alter the regulation of norepinephrine release in the hippocampus following i.p. administration. Interestingly too, time frames for these alterations correspond with the therapeutic effectiveness of these drugs (Ignatowski and Spengler, 1994; Ignatowski et al, 1996, 2005; Nickola et al, 2001). Therefore, injury-evoked changes in norepinephrine release and TNF production are studied in this region associated with pain perception. Moreover, observations obtained from the hippocampus reflect activity at the locus coeruleus, the region containing the neuron cell bodies for noradrenergic terminals (Ungerstedt, 1971). Taken together, the hippocampus is a likely region on which attention should be focused for understanding fundamental mechanisms associated with the development, dissipation, and treatment of pain.

Tricyclic antidepressants are commonly used as analgesics for chronic pain therapy (Magni, 1991; Richeimer et al, 1997). Our previous findings (Ignatowski and Spengler, 1994; Ignatowski et al, 1997) have provided evidence that antidepressant-induced decreases in available TNF in the brain modify the interactive relationship between neuron responses to TNF and α2-adrenoceptor activation. α2-Adrenoceptors, in particular α2A-adrenoceptors, play a significant role in mediating the acute analgesic effect of amitriptyline (Ozdogen et al, 2004). Whether continual amitriptyline administration directs brain-derived TNF production during neuropathic pain, when the activity of the central noradrenergic system is low, is not known. Therefore, in the present study, the effect of chronic treatment with amitriptyline on brain-derived TNF was examined along with TNF immunoreactive staining at a peripheral lesion, where this cytokine orchestrates inflammation.

A major source of TNF during inflammation is the macrophage. These immune effector cells, when removed from complete Freund’s adjuvant-primed animals, possess α2-adrenoceptors that enhance TNF production (Spengler et al, 1990). Whether regulation of TNF production following activation of α2-adrenoceptors on macrophages also changes during neuropathic pain and its treatment, as occurs for α2-adrenoceptors in the hippocampus, was investigated. Specifically, we determined whether increases in TNF levels in the brain with subsequent decreases in norepinephrine release (Covey et al, 2000; Reynolds et al, 2004b) alter the α2-adrenoceptor on macrophages in the periphery to decrease TNF production. An increase in TNF in the brain was endogenously induced by chronic constriction injury and reproduced by extrinsic intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) microinfusion of rat recombinant TNFα (rrTNF) in naïve rats. Results from an investigation of brain-body interactions into the nature of α2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production in the periphery during neuropathic pain would expand our knowledge of how the brain directs peripheral inflammation, and reveal a potential biomarker of pain/analgesia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Experiments were carried out as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University at Buffalo and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health supported Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NRC, 1996). Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–300 g, Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) were used for all experiments. The rats were housed in groups of three to five animals at 23 ± 1°C in Laboratory Animal Facilities-accredited pathogen-free quarters with access to food and water ad libitum. The animals were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle, with the lights on from 0600 – 1800 h. Rats were given at least four days to acclimatize to the animal quarters before testing.

2.2. Chronic constriction injury model of nerve injury

Loose ligatures were applied around the common sciatic nerve of the right hind paw (chronic constriction injury) according to previously described methods (Bennett and Xie, 1988). Briefly, the sciatic nerve was exposed unilaterally, and four ligatures (4.0 chromic gut, Roboz Surgical, Rockville, MD) were placed around the nerve, ~1 mm apart, proximal to the trifurcation. Ligatures were tied such that constriction to the diameter of the nerve was barely discernable, allowing for uninterrupted circulation though the epineural vasculature. In sham procedures, the nerve was similarly exposed, but no ligatures were placed. The incision was closed with surgical clips. All surgeries were performed between 0800–1200 h.

2.3. Thermal hyperalgesia measurements

After specified times post-ligature placement, the thermal nociceptive threshold was measured in each hind paw. Hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to noxious stimuli) was measured by determining changes in paw withdrawal latency using a plantar algesia apparatus (model #33, Analgesia Meter, IITC Life Science Instruments, Woodland Hills, CA) (Hargreaves et al, 1988). Rats were placed in Plexiglas chambers, on top of a temperature maintained (32 ± 0.1°C) glass surface. The animals were acclimatized to the testing apparatus for 7–10 min (or until exploratory behavior ceased). The paw withdrawal latencies were measured using an intense radiant heat source (58 ± 0.1°C) to stimulate thermal receptors in the hind paws. A cut-off latency of 15 s was used to prevent tissue damage. Only rapid hind paw movements away from the thermal stimulus (with or without licking of hind paw) were considered to be a withdrawal response. Paw movements associated with weight shifting or locomotion were not counted. Each hind paw was measured three consecutive times with 4 min intervals between recordings, and the averaged values for each day were used to compute a difference score. Contralateral hypersensitivity was routinely absent following chronic constriction injury (see Table 1), and therefore, a “difference score” was generated by subtracting the contralateral (control) paw withdrawal latency from the ipsilateral (experimental or ligatured) paw withdrawal latency. Thus, a negative difference score is indicative of hyperalgesia. Baseline latencies were determined before experimental treatment for all animals as the mean of three separate trials. The treatments were initiated after measurement of the third trial (indicated as day-0 throughout).

Table 1.

Withdrawal latencies (in seconds) for the ipsilateral and contralateral hind paws of sham-operated and chronic constriction injury rats, with and without amitriptyline treatment, expressed as the average (mean ± S.E.M.) of the number of animals in brackets.

| Days post surgery |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | |

| Sham-ipsilateral | 11.8 ± 1.1 [5] | 14.3 ± 0.7 [5]a | 12.5 ± 1.0 [5]a | 12.9 ± 1.3 [5]a | 14.7 ± 0.3 [5]a | 14.6 ± 0.3 [4]a | 12.6 ± 1.3 [4]a | 12.8 ± 1.3 [4]a | 13.4 ± 0.8 [3]a | 14.5 ± 0.5 [2] | 15.0 ± 0.0 [2] |

| Sham-contralateral | 12.5 ± 0.9 [5] | 14.1 ± 0.8 [5] | 12.0 ± 1.6 [5] | 11.8 ± 1.2 [5] | 13.2 ± 1.2 [5] | 13.9 ± 0.5 [4] | 10.5 ± 1.8 [4] | 12.5 ± 1.5 [4] | 13.7 ± 0.8 [3] | 12.2 ± 0.8 [2] | 14.8 ± 0.2 [2] |

| Sham-Amt(0)-ipsilateral | 10.8 ± 0.8 [10] | 11.6 ± 1.0 [10] | 12.0 ± 1.0 [10] | 13.2 ± 0.7 [8] | 12.2 ± 0.6 [8] | 11.9 ± 1.5 [4] | 8.8 ± 1.0 [4] | 11.0 ± 1.5 [4] | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Sham-Amt(0)-contralateral | 11.1 ± 0.7 [10] | 11.8 ± 0.8 [10] | 13.1 ± 0.9 [10] | 13.5 ± 0.7 [8] | 12.5 ± 0.6 [8] | 11.1 ± 0.9 [4] | 11.0 ± 1.5 [4] | 12.3 ± 1.9 [4] | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| CCI-ipsilateral | 11.6 ± 0.6 [16]c | 5.5 ± 0.4 [16] | 6.8 ± 0.6 [16] | 6.4 ± 0.7 [14] | 5.6 ± 0.4 [14] | 6.6 ± 1.3 [6] | 5.2 ± 0.5 [5] | 6.4 ± 0.9 [5] | 7.6 ± 1.4 [5] | 6.4 ± 0.9 [5] | 7.6 ± 1.8 [5] |

| CCI-contralateral | 11.5 ± 0.5 [16] | 11.5 ± 0.7 [16]b | 11.7 ± 0.6 [16]b | 11.6 ± 0.7 [14]b | 12.3 ± 0.6 [14]b | 10.9 ± 1.7 [6] | 9.6 ± 1.2 [5] | 9.2 ± 1.3 [5] | 11.0 ± 1.6 [5] | 8.5 ± 1.4 [5] | 9.9 ± 1.6 [5] |

| CCI-Amt(0)-ipsilateral | 13.1 ± 0.4 [20] | 12.7 ± 0.5 [20]b | 11.8 ± 0.7 [19]b | 12.4 ± 0.6 [16]b | 11.5 ± 0.8 [15]b | 13.2 ± 0.7 [9]b | 9.8 ± 1.3 [8]b | 10.8 ± 0.7 [8]b | 11.3 ± 1.2 [7] | 13.4 ± 0.7 [4]b | 11.4 ± 1.5 [4] |

| CCI-Amt(0)-contralateral | 12.8 ± 0.4 [20] | 13.9 ± 0.4 [20]b | 13.6 ± 0.4 [19]b | 13.5 ± 0.4 [16]b | 13.0 ± 0.5 [15]b | 13.1 ± 0.7 [9]b | 11.2 ± 0.9 [8]b | 12.9 ± 0.8 [8]b | 13.3 ± 0.7 [7]b | 13.8 ± 0.7 [4]b | 12.0 ± 1.9 [4] |

| CCI-Amt(4)-ipsilateral | 13.2 ± 0.4 [6] | 6.5 ± 0.8 [6] | 7.0 ± 1.1 [5] | 12.4 ± 1.2 [5]b | 13.8 ± 1.0 [5]b | 9.7 ± 2.3 [4] | 12.8 ± 0.9 [4]b | 13.0 ± 0.8 [4]b | 13.1 ± 0.9 [4]b | 13.1 ± 0.6 [3]b | 10.9 ± 1.2 [3] |

| CCI-Amt(4)-contralateral | 13.5 ± 0.6 [6] | 14.6 ± 0.3 [6]b | 14.2 ± 0.4 [5]b | 14.2 ± 0.5 [5]b | 14.3 ± 0.7 [5]b | 13.1 ± 0.7 [4]b | 12.3 ± 0.9 [4]b | 13.6 ± 0.4 [4]b | 14.2 ± 0.8 [4]b | 14.5 ± 0.3 [3]b | 12.1 ± 1.8 [3] |

| CCI-Amt(6)-ipsilateral | 12.7 ± 0.7 [8] | 8.0 ± 1.6 [8] | 8.7 ± 1.6 [8] | 7.3 ± 1.4 [8] | 8.0 ± 1.3 [6] | 6.3 ± 0.7 [5] | 6.7 ± 0.7 [5] | 7.8 ± 0.5 [5] | 6.7 ± 0.4 [5] | 8.1 ± 0.9 [5] | 7.5 ± 0.9 [5] |

| CCI-Amt(6)-contralateral | 12.5 ± 0.6 [8] | 12.5 ± 0.8 [8]b | 13.9 ± 0.8 [8]b | 13.8 ± 0.5 [8]b | 13.0 ± 1.1 [6]b | 12.6 ± 1.3 [5]b | 12.3 ± 1.4 [5]b | 13.3 ± 0.9 [5]b | 12.8 ± 1.0 [5]b | 13.3 ± 0.7 [5]b | 14.0 ± 0.5 [5]b |

Baseline [n=65] withdrawal latencies averaged 12.2 ± 0.3 s for both the ipsilateral and contralateral hind paws.

Statistical significance among the Sham, Sham with amitriptyline initiated at day 0 post surgery, and chronic constriction injury alone groups determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Method for multiple comparisons versus the Sham-ipsilateral control:

Significantly (P < 0.05) different from CCI-ipsilateral at days 2–16 post surgery. The Sham with amitriptyline group consists of both sham-operated rats treated with amitriptyline initiated at day 0 [2] and amitriptyline treated non-operated rats [8].

Statistical significance among the chronic constriction injury alone and chronic constriction injury with amitriptyline treatment initiated on day 0, day 4, and day 6 groups determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Method for multiple comparisons versus the CCI-ipsilateral control:

Significantly (P < 0.05) different from CCI-ipsilateral.

Statistical significance for all days post surgery for CCI-ipsilateral determined using Repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Method for multiple comparisons versus the CCI-ipsilateral day 0:

Significantly (P < 0.05) different from all days (2–20) post chronic constriction injury.

No significant differences were observed for CCI-contralateral hind paw values (days 0–20). CCI, chronic constriction injury; Amt(0), amitriptyline treatment initiated on day 0; Amt(4), amitriptyline treatment initiated on day 4 post surgery; Amt(6), amitriptyline treatment initiated on day 6 post surgery; N.D., not determined.

2.4. Drug administration schedule

Experimental rats were administered either amitriptyline (hydrochloride; 10 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in sterile saline, or vehicle (saline), i.p., every 12 h, for 3–20 days. This dose was selected based on the analgesic dose of this drug to be in the range of 1–30 mg/kg (Esser and Sawynok, 1999; Korzeniewska-Rybicka and Plaznik, 1998). Experimental rats were terminated by rapid decapitation, 12 h after the last injection. All drugs and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless specified otherwise.

2.5. Experimental paradigms

The initial experiments were designed to investigate the effect of preemptive amitriptyline treatment on TNF immunoreactivity in the central nervous system (CNS) as well as in the lesioned nerve. To this end, amitriptyline was administered to rats undergoing chronic constriction injury; the treatment was initiated 1 h prior to the surgery and continued every 12 h for pre-determined times. Rats were terminated at days-4, -8, -16, or -21 post-ligature placement, corresponding to the development, peak and dissipation of thermal hyperalgesia (Ignatowski et al, 2005; Spengler et al, 2007). Respective controls included rats undergoing sham surgery, either alone, or with simultaneous administration (i.p.) of amitriptyline or saline; rats receiving i.p. injections (amitriptyline or saline) alone; and naïve, unoperated rats (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of control and experimental groups included in the study.

| GROUP | SURGERY | i.p. ADMINISTRATION | TIME OF i.p. INITIATION (day post-CCI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCI-AMT(0) | CCI | AMT | DAY-0 |

| CCI-SAL(0) | CCI | SAL | DAY-0 |

| CCI | CCI | - | - |

| Sham-AMT(0) | Sham | AMT | DAY-0 |

| Sham-SAL(0) | Sham | SAL | DAY-0 |

| Sham | Sham | - | - |

| AMT only | - | AMT | DAY-0 |

| SAL only | - | SAL | DAY-0 |

| Control (Naïve) | - | - | - |

| CCI-AMT(4) | CCI | AMT | DAY-4 |

| CCI-AMT(6) | CCI | AMT | DAY-6 |

AMT = amitriptyline (10 mg/kg); SAL = sterile saline; CCI = chronic constriction injury

To further define its antinociceptive effect, in separate groups of rats, amitriptyline treatment was initiated at day-4 or day-6 post-ligature placement, and continued every 12 h. Rats from these groups were terminated at days-8, -16 or -21 post-ligature placement. All paradigms are summarized in Table 2.

2.6. Caliper measurements of sciatic nerve diameter

To determine the effect of experimental paradigms on sciatic nerve diameter, following decapitation, both nerves were placed on an ice-block upon harvest, and multiple measurements of the diameter were made along the length of the nerves using a digital caliper (VWR International, West Chester, PA). The ipsilateral sciatic nerves were harvested by cutting the nerves shortly above the location of the ligatures and ~1.0 cm distally. Sciatic nerves from the contralateral side, as well as from sham-operated and control rats were removed in the same manner. Three measurements each were recorded for proximal, ligatured and distal sections of ipsilateral nerves, and averaged to give one value for nerve diameter. Similar measurements were recorded and averaged for contralateral nerves. Results are expressed as a “difference value” generated by subtracting the average diameter of the contralateral nerve (mm) from the average diameter of the ipsilateral nerve (mm).

2.7. Immunohistochemistry for TNF

Upon decapitation, the hippocampi were harvested. The hippocampi and sciatic nerves (following caliper measurements) were embedded in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. compound (Finetech, Torreance, CA), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and processed for immunohistochemistry.

Cryostat sections (10 µm) of harvested tissues were serially cut and collected on StarFrost™ glass slides (Mercedes Medical, Sarasota, FL). Sections were fixed with acetone (10 min), fan-dried (10 min) and stained for TNF according to previously published protocols (Ignatowski et al, 1997; Ignatowski and Spengler, 2002) with the following modifications: Sections were incubated with 10% goat serum in PBS supplemented with 0.1% BSA (MP Biomedicals Inc., Irvine, CA) for 15 min to eliminate non-specific binding. Goat serum was blotted off the slides, and sections incubated with the primary antibody, polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse TNF (Calbiochem-Novabiochem, La Jolla, CA) that cross-reacts with rat TNF, at 1:100 dilution (in PBS supplemented with 0.1% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100) for 1 h. Following two PBS rinses, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vectastain kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), preabsorbed (1:100 dilution) in normal rat serum at 37°C for 45 min prior to use, was added to sections and incubated for 45 min. Slides were rinsed in 1X PBS, incubated with biotinylated enzyme conjugate (Vector) for 30 min, and the reaction localized using 3,3’-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate for 10 min. SIGMA FAST™ DAB tablets were dissolved in 0.05 M Tris supplemented with 0.01 M imidazole. Rinsing with distilled water (two rinses, 5 min each) terminated the development of color. Unless stated otherwise, all incubations were carried out at room temperature. As a negative control, primary antibody was substituted by normal rabbit serum at the same protein concentration, which did not result in any specific labeling.

Images from stained tissue sections were captured under bright-field conditions using a digital camera (Pixera 600ES-CU) attached to a Zeiss Axiovert 35 microscope and using imaging device Viewfinder (version 3.0.1; Pixera Corp.) and Studio (version 3.0.1; Pixera Corp.) software. All images were obtained on the same day using the same light intensity and magnification (200x) settings by one observer who was not aware of the treatment groups. Images were saved as tiff files and analyzed using ImageJ 1.32j software (NIH, USA, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) with the Color Deconvolution plug-in to perform stain separation. Following background subtraction, color deconvolution of the RGB tiff files was performed using the built-in hematoxylin and DAB (H DAB) vector, as the third (complementary) 8-bit image generated was completely white (Ruifrok and Johnston, 2001). The second 8-bit tiff file corresponding to the DAB (TNF) contribution was then further analyzed. This 8-bit tiff file was converted to grey-scale and thresholded in ImageJ using the auto threshold tool. Resultant mean density values for TNF staining were compared.

2.8. Peritoneal lavage

Peritoneal cavities of rats were flushed with 10 ml incomplete media (RPMI-1640 (Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA) containing 1% glutamine (GIBCO Cell Culture, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA)), supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (1:400 dilution). The lavage collected was centrifuged at 300 × g, 4°C, for 7 min. The supernatant was stored at −20°C until analysis of bioactive TNF present in the peritoneal cavity at the time of decapitation. The cell pellet was resuspended in incomplete media (without the cocktail) at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml. Peritoneal macrophages were plated in 8-chamber lab-tek wells (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) in 400 µl incomplete media per well. After 2 h incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2 to allow adherence, lab-teks were washed extensively with PBS (1X, GIBCO), overlaid with incomplete media, and adherent cells were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (30 ng/ml) (Escherichia coli 0111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich) to produce TNF, either alone, or with the selective α2-adrenoceptor agonist clonidine (10−7 M) in the presence or absence of the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist yohimbine (10−6 M). This concentration of clonidine was chosen based on previous functional studies demonstrating that this corresponds to the EC90 value for α2-adrenoceptor regulation of LPS-stimulated TNF production (Spengler et al, 1990). Likewise, previous studies have established that 30 ng/ml LPS corresponds to the EC80 value for stimulation of TNF production from peritoneal macrophage (Spengler et al, 1989, 1990). In control wells adherent cells were overlaid with media alone. Macrophages were incubated for 4 h, corresponding to the peak in stimulated TNF production (Spengler et al, 1989), and the supernatants were aspirated and stored at −20°C until the analysis of bioactive TNF, as detailed below.

2.9. Whole blood

Whole blood cultures are an ex vivo model to study the effects of experimental conditions/agents on cytokine production, while preserving the natural cell-to-cell interactions present in vivo (DeForge and Remick, 1991; De Groote et al, 1992). Upon decapitation, trunk blood was collected in a 50-ml conical tube containing tripotassium EDTA as an anticoagulant at a final concentration of 1.8 mg/ml; this was diluted (1:10) with incomplete media (supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail at 1:400 dilution). A two-ml aliquot of the diluted whole blood was centrifuged at 300 × g, 4°C, for 7 min to isolate plasma, which was stored at −20°C and analyzed for biologically active TNF as described below. In addition, 200 µl of the diluted whole blood was added to each well of a sterile 24-well plate (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) containing 1.8 ml incomplete media, with or without adrenergic agents (Maes et al, 2000). Two of the wells contained only media, and served as ‘control’ wells. The remaining wells contained the following drugs: LPS (30 ng/ml) either alone, or in combination with clonidine (10−7 M). The drug(s) were added to the wells immediately prior to addition of diluted whole blood. Following addition of trunk blood, the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, corresponding to the peak in stimulated TNF production (Spengler et al, 1989). At the end of incubation period, cell-free supernatants were harvested and stored at −20°C until analysis of bioactive TNF.

2.10. Analysis of biologically active TNF in culture supernatants

TNF bioactivity was analyzed in supernatants using the WEHI-13VAR fibroblast cell line (Khabar et al, 1995), which is sensitive to the lytic effects of TNF. This cytotoxicity assay measures cell lysis as a surrogate of TNF activity. WEHI-13VAR cells (5 × 105 cells/ml) suspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 1% glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 0.5 µg/ml Actinomycin D (Calbiochem-Novabiochem) were cultured in 0.1 ml in 96-well microtiter plates (Falcon, BD Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with serially-diluted test samples (starting dilution, 1:4). After 20 h incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2, 20 µl of methylthiazoletetrazolium (MTT) solution (5 mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C. After 4 h incubation, formazon crystals formed within cells by the metabolism of MTT were dissolved by removing 150 µl of supernatant from each well and adding 100 µl of 0.04 N HCl/isopropanol. The plates were wrapped in aluminum foil and incubated overnight in a dark, moist chamber. The absorbance measured at 540 nm using ELX808 plate reader (BIO-TEK Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT) was used to calculate the amount of TNF in each sample, from regression of recombinant human TNFα (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) (10,000 pg/ml to 0.1 pg/ml) standard absorbances. The lower limit of sensitivity of the assay is 3 pg/ml.

2.11. Intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) microinfusion of rat recombinant TNF (rrTNF)

As previously published (Ignatowski et al, 1999; Reynolds et al, 2004b), mini osmotic pumps (0.5 µl/h, 14 days; Alzet, DURECT Corp., Cupertino, CA) and brain infusion cannulae (Alzet) were assembled according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The vehicle used for delivery of the infused compounds was artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) of the following composition (mM): NaCl, 216.5; KCl, 3; CaCl2·2H2O, 1.4; MgCl2·6H2O, 0.8; Na2HPO4·7H2O, 0.8; and NaH2PO4, 0.2. Gentamycin 0.1 mg/ml solution was added to the aCSF to prevent bacterial growth. Rat albumin fraction V, 1 mg/ml was added to stabilize the infused compound and to prevent proteins and charged molecules from binding non-specifically. Male, Sprague–Dawley rats, 250–350 g, anesthetized with ketamine 60 mg/kg and xylazine 3 mg/kg, i.p., were secured on a stereotaxic platform. With bregma used as the zero point, the following stereotaxic coordinates (Paxinos and Watson, 1997): A–P, −0.92 mm; lateral, 1.6 mm; vertical, 3.5 mm, were used for trephining the skull prior to cannulation of the right lateral cerebral ventricle. Rat recombinant TNFα (rrTNF, R&D Systems) was microinfused for 14 days. The concentration of rrTNF infused (1000 ng/24 hr at 0.5 µl/hr for 14 days) was chosen based on our previous studies that established a role for TNF in the CNS, and does not result in adverse side effects (Ignatowski et al., 1999). The dosage used was based on the EC50 value for inhibition of 3–10 pg/ml TNF in the WEHI-13VAR bioassay. Controls consisted of rats microinfused with heat-inactivated TNF in aCSF or aCSF alone.

2.12. Statistics

All results are expressed as mean values ± S.E.M. Analysis of data was performed using SigmaStat statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data were analyzed using Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA, or two-way ANOVA. When significant differences were observed, appropriate post hoc tests were performed as indicated in the figure legends. A difference was accepted as significant when P < 0.05. Measurements from thermal hyperalgesia were analyzed at each time point to detect overall differences among various treatment groups. Mean density values for TNF staining as determined from ImageJ analysis were compared among treatment groups.

3. Results

3.1. Temporal course of thermal hyperalgesia in the chronic constriction injury model and the effect of systemic amitriptyline treatment

Peripheral mononeuropathy from constriction of the right sciatic nerve resulted in rapid development of thermal hyperalgesia, evident at day-2 post-ligature placement in experimental animals (Fig. 2A). This is demonstrated by the negative difference score, which is indicative of increased sensitivity to a noxious thermal stimulus. As shown in Fig. 2A, thermal hyperalgesia peaks between days-2–8 post-ligature placement and gradually abates thereafter, reaching non-significant differences from sham-operated animals at day-20 post-ligature placement. Paw withdrawal latencies of sham-operated animals did not differ from naïve, unoperated animals tested at the same times, with differences being close to the zero score (data not shown). Additionally, there were no differences noted among the contralateral paw recordings throughout the duration of chronic constriction injury or chronic amitriptyline administration to rats (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

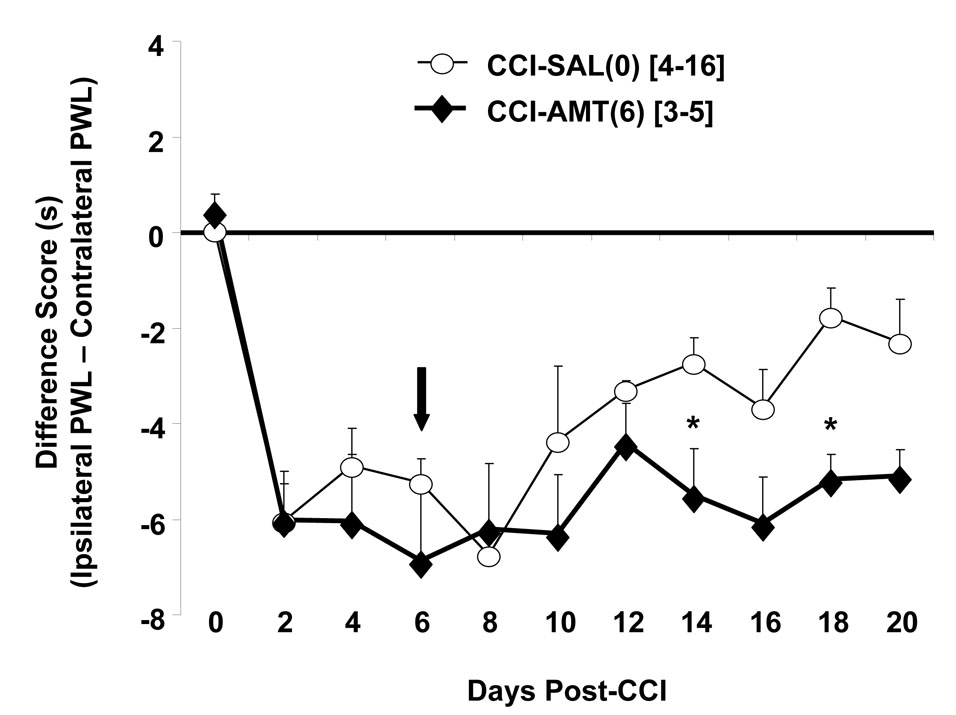

Assessment of thermal hyperalgesia in rats undergoing chronic constriction injury alone, or with concomitant treatment with amitriptyline. Rats receive ligature placement unilaterally around the sciatic nerve, alone, or with concomitant treatment with amitriptyline (10 mg/kg, i.p., twice daily). Data are presented as the difference score of ipsilateral (experimental) – contralateral (control) hind paw withdrawal latency in seconds. Each point is expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (number of rats in brackets). (A) Amitriptyline treatment is initiated 1 h prior to ligature placement (indicated by the arrow), and continued every 12 h until pre-determined times post-ligature placement. Note: Amitriptyline treatment concomitant with ligature placement delays and attenuates thermal hyperalgesia. Statistical significance analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.001 compared to sham-operated; # P < 0.001, compared to chronic constriction injury rats. (B) Amitriptyline treatment is initiated at day-4 post-ligature placement, indicated by the position of the arrow, in rats receiving unilateral ligature placement around the sciatic nerve. Statistically significant as analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s analysis with CCI-SAL(0) rats serving as the control for comparisons, * P < 0.05. Note: Amitriptyline treatment initiated on day-4 post-ligature placement rapidly attenuates thermal hyperalgesia. (C) Amitriptyline treatment is initiated in rats receiving unilateral ligature placement around the sciatic nerve at day-6 post-ligature placement, indicated by the position of the arrow. Statistically significant as analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s analysis with CCI-SAL(0) rats serving as the control for comparisons, * P < 0.05. Note: When initiated at day-6 post-ligature placement, amitriptyline is no longer efficacious in treating thermal hyperalgesia in the chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain (compare to panel 2A). SHAM-SAL(0) = sham surgery of the sciatic nerve with simultaneous saline administration; SHAM-AMT(0) = sham surgery of the sciatic nerve with simultaneous amitriptyline administration; CCI-AMT(0) = amitriptyline treatment concomitant with chronic constriction injury; CCI-SAL(0) = chronic constriction injury with simultaneous saline administration; CCI-AMT(4) = amitriptyline treatment initiated at day-4 post-ligature placement; CCI-AMT(6) = amitriptyline treatment initiated at day-6 post-ligature placement.

Treatment with amitriptyline initiated 1 h prior to ligature placement and continued every 12 h, resulted in significant attenuation of thermal hyperalgesia in rats undergoing chronic constriction injury (Fig. 2A). When initiated at day-4 post-ligature placement and continued every 12 h, amitriptyline treatment rapidly attenuated thermal hyperalgesia in chronic constriction injury animals (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, when initiated at day-6 post-ligature placement and continued every 12 h, not only was amitriptyline inefficacious in alleviating thermal hyperalgesia, but also the spontaneous dissipation of this symptom, evident in rats receiving ligatures either alone or with simultaneous administration of saline (vehicle), was prevented (Fig. 2C).

3.2. Effect of ligature placement and amitriptyline treatment on sciatic nerve diameter

Sham surgery alone did not result in any significant change in nerve diameter when compared with naïve, unoperated animals (data not shown). As the “difference values” generated by subtracting the averaged contralateral nerve diameter (mm) from the averaged ipsilateral nerve diameter (mm) for the proximal, ligatured, and distal regions did not differ either within or between chronic constriction injury rat paradigms statistically, the measurements from these three regions were averaged to give one value for nerve diameter. In comparison to the ‘sham’ group, the “difference values”, and hence the diameters of the ipsilateral nerves are significantly increased in rats undergoing ligature placement (P < 0.05, ANOVA on Ranks followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test) (Fig. 3). Treatment with amitriptyline in the chronic constriction injury groups did not reduce chronic constriction injury-induced increases in the difference values. Administration of amitriptyline or saline alone to rats also did not produce any significant change in the difference values of nerves as compared to nerves harvested from naïve rats (data not shown). Similarly, administration of amitriptyline or saline simultaneous with sham surgery did not alter the diameter of the sciatic nerves in comparison to sham-operated rats (Fig. 3, inset).

Fig. 3.

Caliper measurements of sciatic nerve diameter in rats undergoing chronic constriction injury, alone or with concomitant amitriptyline treatment: Data are presented as the difference of ipsilateral (experimental) – contralateral (control) nerve diameter (mm). Each point is expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (number of rats in brackets). Inset shows the difference values in appropriate control rats. CCI-SAL(0) = chronic constriction injury with simultaneous saline administration; CCI-AMT(0) = amitriptyline treatment concomitant with ligature placement; CCI-AMT(4) = amitriptyline treatment initiated at day-4 post-ligature placement; CCI-AMT(6) = amitriptyline treatment initiated at day-6 post-ligature placement. Note: Compared to controls (inset), chronic constriction injury causes increases in the diameter of the ipsilateral sciatic nerves at all times post-ligature placement examined (P < 0.05, ANOVA on Ranks followed by Dunn’s post-hoc analysis). Amitriptyline treatment, regardless of time of treatment initiation, has no effect on chronic constriction injury -induced increases in ipsilateral nerve diameters, and therefore, on the difference values.

3.3. Immunoreactive staining for TNF in the peripheral and central nervous systems during amitriptyline treatment of neuropathic pain

Sciatic nerves harvested from sham-operated (day-8 post-surgery) animals demonstrate expression of TNF (Fig. 4A, panel a), similar to that observed for naïve animals (data not shown). Initial qualitative analysis of images of sciatic nerves suggested that nerves from rats at day-8 post-ligature placement (Fig. 4A, panel b) exhibited higher levels of immunoreactivity than sciatic nerves from sham-operated animals. Subsequent quantitative image analysis further confirmed that TNF expression in these nerves is enhanced, compared to sham-operated animals (Fig. 4B; P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s analysis of mean density values 80.4 ± 4.6 vs. 50.4 ± 7.3, respectively). Observation of TNF immunoreactivity in animals receiving amitriptyline (10 mg/kg, i.p.) treatment (initiated at either day-0 or day-4 post-ligature placement) reveals an apparent decrease in TNF at the lesion (Fig. 4A, panels c and d), with significance noted in the day-0 paradigm (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s analysis of mean density values 55.2 ± 8.9 for day-0 vs. day-8 post-ligature placement) (Fig. 4B). TNF immunoreactivity in animals receiving amitriptyline treatment at day-6 post-ligature placement (Fig. 4A, panel e) displayed similar intensity of TNF staining as chronic constriction injury alone (mean density values of 69.8 ± 4.1 vs. 80.4 ± 4.6, respectively, NS, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s Method) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Immunoreactive staining for TNF in ipsilateral sciatic nerves from day-8 rats. (A) Shown in each panel is a representative longitudinal section of sciatic nerve of three independent animals: (a) Sham-8 rats; (b) rats at day-8 post-ligature placement (CCI-8); (c) rats at day-8 post-ligature placement with amitriptyline (10 mg/kg, i.p., twice daily) treatment initiated at day-0 post-ligature placement (CCI-8-AMT(0)); (d) rats at day-8 post-ligature placement with amitriptyline treatment initiated at day-4 post-ligature placement (CCI-8-AMT(4)); and (e) rats at day-8 post-ligature placement with amitriptyline treatment initiated at day-6 post-ligature placement (CCI-8-AMT(6)). Scale bar = 50 µM (B) Quantitative analysis of TNF immunoreactive staining. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s analysis of mean density values with CCI-8 serving as the control for all comparisons: Sham-8 vs. CCI-8 (P < 0.05); CCI-8-AMT(0) vs. CCI-8 (P < 0.05). For each group, n=3.

Coronal sections of right and left hippocampi harvested from sham-operated (day-8 post-surgery) rats show constitutive immunoreactivity for TNF (Fig. 5A, panel a), similar to naïve rats (data not shown) (Ignatowski et al, 1997). At day-8 post-ligature placement, simultaneous with maximal hypersensitivity to noxious thermal stimulus, immunoreactivity for TNF is increased in the left hippocampus (P < 0.01, ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc analysis of mean density values 85.3 ± 2.5 vs. 118.1 ± 6.8, respectively) (Figs. 5A, panel b and 5B), the side contralateral to nerve injury. Concomitant treatment with amitriptyline prevented the increase in TNF in the left hippocampus (mean density value 66.4 ± 5.4, NS, as compared to TNF staining in hippocampal slices from Sham-operated rats) (Figs. 5A, panel c and 5B).

Fig. 5.

Immunoreactivity for TNF in contralateral hippocampal sections. (A) Shown in each panel is a representative coronal section of hippocampus of four independent animals from: (a) Sham-operated (day-8 post-surgery), (b) Day-8 post-ligature placement (CCI-8), and (c) Day-8 post-ligature placement with concomitant (initiated at day-0) amitriptyline treatment (10 mg/kg, i.p., twice daily) (CCI-8-AMT(0)). Scale bar = 50 µM (B) Quantitative analysis of TNF immunoreactive staining. Statistical analysis of mean density values (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test) demonstrates that TNF immunoreactivity is significantly enhanced in the contralateral hippocampus at day- 8 post-ligature placement as compared to the contralateral hippocampus from sham-operated rats (P < 0.01). Concomitant treatment with amitriptyline prevents the increase in TNF immunoreactivity in the hippocampus (NS, as compared to sham-operated). For each group, n=4.

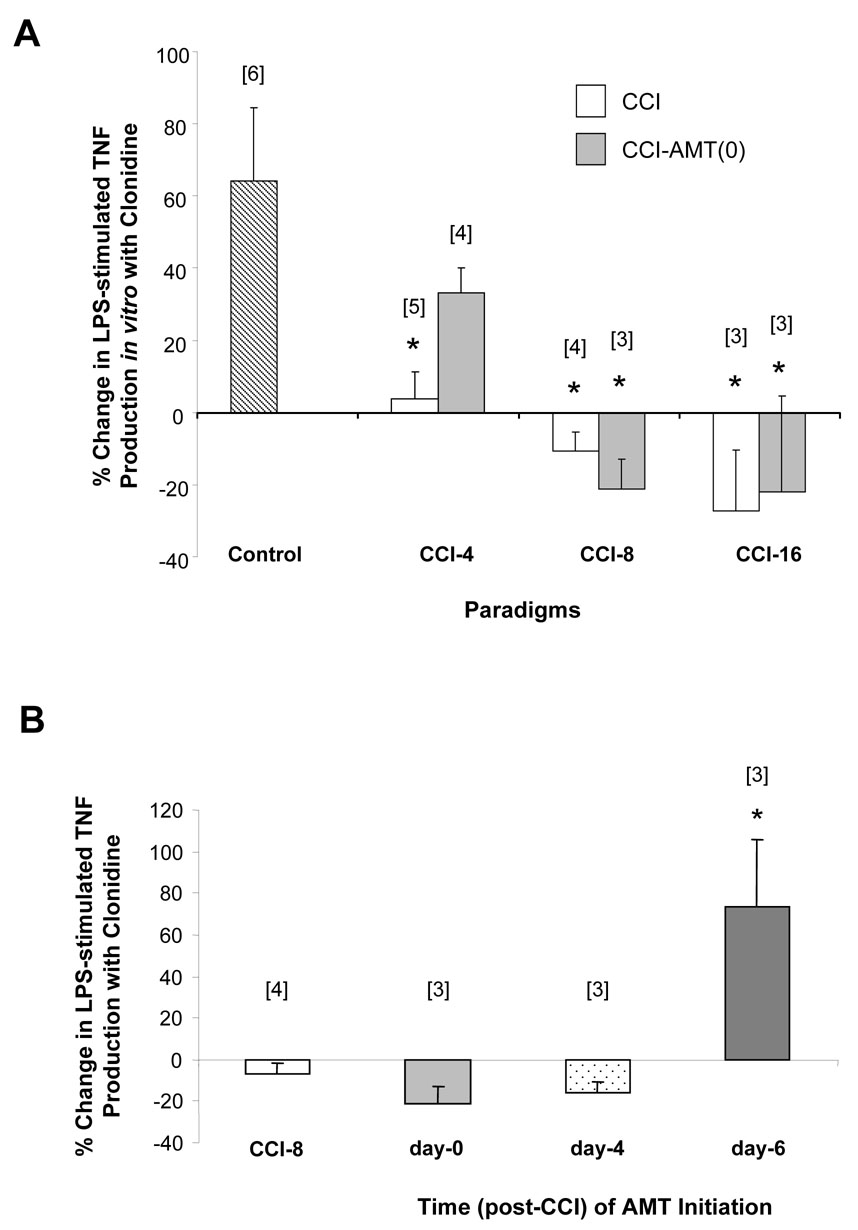

3.4. Alpha2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production from peritoneal macrophages

Peritoneal macrophages were chosen for the present studies since they represent a sizable pool of peripheral, fully differentiated macrophage, thus allowing enough cells for various in vitro paradigms and comparison of results with our previously published findings. α2-Adrenoceptor potentiation of LPS-stimulated TNF production from peritoneal macrophages harvested from control animals has been well documented by our laboratory, including that the effect of a clonidine derivative on macrophage release of TNF is a receptor-mediated event (Ignatowski et al, 2000; Spengler et al, 1990, 1994). Clonidine-induced potentiation of LPS-stimulated TNF production is an α2-adrenoceptor mediated event as demonstrated by blockade of clonidine-induced potentiation with the selective antagonist yohimbine (10−6 M) (% change in TNF production from LPS-stimulation alone: 37.8 ± 9.4% with 10−7 M clonidine vs. 6.3 ± 10% with clonidine and yohimbine, n = 6, P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). In animals undergoing chronic constriction injury, during the development and maintenance of thermal hyperalgesia, α2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production is reversed, from potentiation to inhibition (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, inhibition of LPS-stimulated TNF production by the α2-adrenoceptor is maximal at day-8 post-ligature placement (Fig. 6A), corresponding to the time period of maximum thermal hyperalgesia (days-2–8 post-ligature placement) displayed by these animals (Fig. 2A). Inclusion of yohimbine with clonidine in LPS-stimulated macrophage cultures no longer prevents the clonidine response during chronic constriction injury (day-4 post-ligature placement, −7.7 ± 8.6% with clonidine vs. −16.3 ± 9.6% with clonidine and yohimbine, n = 4; day-8 post-ligature placement, −36.9 ± 9.9% with clonidine vs. −37.7 ± 10.9% with clonidine and yohimbine, n = 8; day-16 post-ligature placement, 22.2 ± 19.6% with clonidine vs. 0.58 ± 34.9% with clonidine and yohimbine, n = 3; NS, Student’s t-test).

Fig. 6.

α2-Adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production from peritoneal macrophages harvested from rats undergoing paradigms indicated under the abscissa. Data are expressed as % change in LPS (30 ng/ml)-stimulated TNF production with clonidine (10−7 M) in vitro calculated with respect to macrophages stimulated with LPS alone. Culture supernatants were harvested after 4 h, and analyzed for biologically active TNF as explained in Materials and Methods. The n values for each group are indicated in brackets on top of the respective bars. (A) α2-Adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production from macrophages harvested from rats undergoing chronic constriction injury, in comparison to control group. The control group (n = 8) consists of data pooled from naïve (4) and Sham-8 (4) animals, since no significant differences were observed among the two groups (TNF (pg/ml) in supernatants from non-stimulated macrophages: naïve, 14.7 ± 5.5 pg/ml versus Sham-8, 15.6 ± 1.4 pg/ml, NS; or stimulated with 30 ng/ml LPS alone: naïve, 49.4 ± 23.8 pg/ml versus Sham-8, 116.5 ± 78.3 pg/ml, NS, Student’s t-test). Statistically significant * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.001, as compared to the control group, Student’s t-test. (B) Effect of simultaneous treatment of chronic constriction injury-rats with amitriptyline (10 mg/kg, i.p., twice daily) on subsequent in vitro α2-adrenergic regulation of LPS (30 ng/ml)-stimulated TNF production. Statistically significant # P = 0.01, as compared to day-4 post-ligature placement group, Student’s t-test. (C) Comparison of amitriptyline administration (10 mg/kg, i.p., twice daily) alone or simultaneous with chronic constriction injury on α2-adrenoceptor regulation of macrophage-derived TNF in vitro. Statistically significant # P < 0.01, as compared to control, one-way ANOVA run at each time frame followed by Tukey test. (D) α2-Adrenoceptor regulation of LPS-stimulated, macrophage-derived TNF production from rats terminated at day-8 post-ligature placement. Statistically significant † P < 0.02, as compared to day-8 post-ligature placement (CCI-8) group, Student’s t-test. (E) α2-Adrenoceptor regulation of LPS-stimulated, macrophage-derived TNF production from rats terminated at day-16 post-ligature placement. Statistically significant † P < 0.02, * P < 0.05, as compared to day-16 post-ligature placement (CCI-16) group, Student’s t-test. CONT = control; AMT = amitriptyline; CCI = chronic constriction injury; CCI-AMT(0) = amitriptyline treatment initiated concomitant with ligature placement.

Regulation of LPS-stimulated TNF production from peritoneal macrophages harvested from rats at day 4 post-ligature placement that were treated with amitriptyline (10 mg/kg, i.p.) simultaneous with undergoing chronic constriction injury demonstrate that α2-adrenoceptor activation inhibits TNF production to a greater extent in this paradigm, compared to chronic constriction injury alone (Fig. 6B). This finding demonstrates that the switch/reversal that occurs prior to the natural dissipation of pain happens sooner and with greater efficacy for an α2-adrenoceptor agonist during treatment with amitriptyline. Interestingly too, treatment with amitriptyline now favors an α2-adrenoceptor phenotype that is sensitive to yohimbine, an effect not evident in rats undergoing chronic constriction injury alone. The percent change in LPS-stimulated TNF production from macrophages taken from chronic constriction injury rats treated concomitantly with amitriptyline (10 mg/kg, i.p.) is as follows: at day-4 post-ligature placement, −73.2 ± 15.1% with clonidine vs. −11.6 ± 3.5% with clonidine and yohimbine, n = 3, P = 0.017; at day-8 post-ligature placement, −16.7 ± 7.4% with clonidine vs. −4.8 ± 15.5%, n = 4, NS; at day-16 post-ligature placement, −12.5 ± 2.3% with clonidine vs. 15 ± 8.1% with clonidine and yohimbine, n = 3, P = 0.031; Student’s t-test.

Amitriptyline administration (10 mg/kg, i.p.) either alone, or in combination with sham surgery, did not affect paw withdrawal latencies (Fig. 2A, closed squares). However, in vitro activation of α2-adrenoceptors on peritoneal macrophages harvested from these animals exhibit an apparent reduction in potentiation of TNF production, after either 4 or 8 days of administration. A complete reversal (P < 0.01) in α2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production occurs after 16 days of amitriptyline administration alone (Fig. 6C).

In rats undergoing chronic constriction injury either alone, or simultaneous with saline administration, and terminated at day-8 post-ligature placement, activation of the α2-adrenoceptor inhibits LPS-stimulated production of TNF (Fig. 6A & 6D). Similarly in macrophages harvested from amitriptyline-treated chronic constriction injured rats (shaded bars, Fig. 6D), activation of the α2-adrenoceptor inhibits LPS-stimulated production of TNF. It is noteworthy that the level of inhibition of TNF production upon activation of the α2-adrenoceptor is comparable in macrophages harvested from rats receiving amitriptyline treatment starting at day-0 (19.0 ± 6.2% inhibition), or at day-4 post-ligature placement (15.8 ± 8.6% inhibition). Of particular interest, α2-adrenoceptor activation in macrophages harvested at day-8 post-ligature placement from rats treated with amitriptyline, with treatment beginning at day-6 post-ligature placement when amitriptyline treatment is ineffective, demonstrates a potentiation of LPS-stimulated TNF production (Fig. 6D).

Chronic constriction injured rats terminated at day-16 post-ligature placement (during the dissipation of thermal hyperalgesia; Fig. 2A) demonstrate a ‘neutral’ state of the α2-adrenoceptor in its regulation of macrophage-derived TNF, whereby in vitro activation of the receptor does not elicit either a prominent inhibitory or an enhancing effect on LPS-stimulated TNF production (Fig. 6E). However, a distinct inhibitory response for α2-adrenoceptor activation on LPS-stimulated TNF production is evident in macrophages harvested from rats receiving amitriptyline treatment in paradigms where it effectively alleviates thermal hyperalgesia. And interestingly too, macrophages harvested from rats receiving amitriptyline treatment initiated at day-6 post-ligature placement, where it is ineffective in alleviating thermal hyperalgesia, demonstrate a facilitation of TNF production by α2-adrenoceptor activation.

3.5. Alpha2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production in whole blood cultures

Analyses of whole blood cultures that contain monocytes, macrophage precursors, are compared to macrophages as they respond in vitro to α2-adrenoceptor activation during stimulation by LPS. TNF production in whole blood cultures prepared from rats undergoing similar paradigms as those investigated for macrophages was analyzed. Similar to macrophages harvested from the peritoneum, whole blood cultures stimulated by LPS (30 ng/ml) alone without pharmacological activation of the α2-adrenoceptor, showed no difference in the production of TNF as assessed in the supernatants among the various paradigms (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 7A, activation of the α2-adrenoceptor (clonidine, 10−7 M) in whole blood cultures prepared from control rats potentiates LPS-stimulated TNF production. At day-4 post-ligature placement, a significant decrease is observed in this effect, which is completely reversed to inhibition at day-8 post-ligature placement. This inhibitory effect on TNF production is persistent in cultures prepared from rats at day-16 post-ligature placement (Fig. 7A). Similar to peritoneal macrophages harvested from rats undergoing chronic constriction injury (Fig. 6B), α2-adrenoceptor regulation of LPS-stimulated TNF production from whole blood cultures prepared from rats undergoing chronic constriction injury and simultaneous treatment with amitriptyline (10 mg/kg, i.p.) also demonstrates a continued reversal at days-8 and -16 post-ligature placement (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

(A) Effect of in vitro α2-adrenoceptor activation (clonidine, 10−7 M) on LPS (30 ng/ml)-stimulated TNF production in whole blood cultures harvested from rats undergoing chronic constriction injury alone or with simultaneous amitriptyline (10 mg/kg, i.p., twice daily) treatment. Statistically significant * P < 0.05 as compared to ‘control’, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test run at each time frame post-ligature placement. The control group (n = 6) consists of data pooled from naïve (4) and Sham-8 (2) animals, based on no observable differences among the whole blood ‘control’ groups (TNF (pg/ml) in supernatants from non-stimulated whole blood cultures: naïve, 4.0 ± 0.9 pg/ml versus Sham-8, 9.7 ± 7.6 pg/ml; or whole blood cultures stimulated with 30 ng/ml LPS alone: naïve, 15.6 ± 4.3 pg/ml versus Sham-8, 23.5 ± 6.3 pg/ml). (B) Effect of α2-adrenoceptor activation on LPS-stimulated TNF production in vitro in whole blood cultures harvested from rats at day-8 post-ligature placement. Statistically significant * P < 0.05 as compared to amitriptyline administration initiated at day-0, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test with CCI-8 alone serving as the control for all comparisons. CCI = chronic constriction injury; CCI-AMT(0) = CCI-rats receiving concomitant treatment with amitriptyline (10 mg/kg, i.p., twice daily). The number of determinations for each paradigm is indicated in brackets above the bars.

In rats undergoing chronic constriction injury alone, or simultaneous with saline administration, and terminated at day-8 post-ligature placement, activation of the α2-adrenoceptor inhibits the production of TNF (Figs. 7A and 7B). Similarly in whole blood cultures harvested from amitriptyline-treated (starting at day-0 or day-4 post-ligature placement) chronic constriction injury-rats (shaded bars, Fig. 7B), activation of the α2-adrenoceptor inhibits LPS-stimulated production of TNF at day-8 post-ligature placement. This α2-adrenoceptor inhibition of LPS-stimulated TNF production is comparable to that observed in peritoneal macrophages harvested from rats receiving amitriptyline treatment starting at day-0 or at day-4 post-ligature placement (Fig. 6D). Remarkably, α2-adrenoceptor activation in whole blood cultures harvested at day-8 post-ligature placement from rats treated with amitriptyline, with treatment beginning at day-6 post-ligature placement, demonstrates a potentiation of LPS-stimulated TNF production (Fig. 7B). Therefore, amitriptyline administered at day-6 post-ligature placement, when it is not analgesic (Fig. 2C), not only prevents the natural reversal that occurs 8 days post-ligature placement, but also induces an enhanced pro-inflammatory response by the α2-adrenoceptor.

3.6. Intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) microinfusion of rrTNF reverses α2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production by peritoneal macrophages

The increase in levels of TNF in the brain as occurs during the development of neuropathic pain was mimicked to determine whether it could mediate the reversal in α2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production by peripheral macrophages. The increase in brain TNF levels induced by chronic constriction injury was reproduced by continuously microinfusing rrTNF into the right lateral cerebral ventricle using 14-day mini-osmotic pumps. Peritoneal macrophages harvested from rats continuously receiving vehicle, aCSF, by i.c.v. microinfusion demonstrate a potentiation in LPS-stimulated TNF production following activation of the α2-adrenoceptor with clonidine (10−7 M) in vitro (Fig. 8), similar to control macrophages (Fig. 6A). In support of our hypothesis, activation of the α2-adrenoceptor (clonidine, 10−7 M) on LPS-stimulated macrophages harvested from rats that received continual i.c.v. microinfusion of rrTNF alone demonstrated inhibition of TNF production (Fig. 8). This finding is similar to that noted during chronic constriction injury (Fig. 6A). Continuous i.c.v. microinfusion of rrTNF for 14 days did not affect LPS-induced TNF release from macrophages (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

Effect of in vitro α2-adrenoceptor activation (clonidine, 10−7 M) on LPS (30 ng/ml)-stimulated TNF production in peritoneal macrophages harvested from rats infused with rrTNF into the right lateral cerebral ventricle for 14 days. Data are expressed as the % change in TNF levels released into supernatants as compared to LPS stimulation alone. Statistical significance of % change in TNF levels compared to aCSF-infused rats * P < 0.05 was determined using Student’s t-test. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E.M. with the number of rats indicated in brackets.

4. Discussion

Cytokines and neurotransmitters are principal signals mediating bidirectional communication between the nervous and immune systems. Such crosstalk is important in maintaining homeostasis. Thus, aberrant production of either of these two classes of mediators could profoundly affect signaling by the other, consequently impacting health. Indeed, enhanced production of TNF in the nervous system (Covey et al, 2000; Xie et al, 2006), culminating in decreased noradrenergic activity (Covey et al, 2000), contributes to the development of neuropathic pain. It is, thus, no surprise that TNF has recently been implicated in the mechanism of both the antidepressant and the analgesic actions of amitriptyline (Ignatowski et al, 2005; Reynolds et al, 2004a) specifically in a brain region (hippocampus) where the perception of pain is modulated (Delgado, 1955; Dutar et al, 1985; Khanna and Sinclair, 1989; McEwen, 2001; McKenna and Melzack, 1992). In the present study, we provide both indirect and direct evidence supporting brain-derived TNF as a modulator of brain-body interactions during neuropathic pain.

Our present findings demonstrate that the efficacy of chronic amitriptyline treatment in alleviating thermal hyperalgesia in chronic constriction injury-rats is strictly dependent on the time of treatment initiation (Fig. 2). These data show a therapeutic window (corresponding to days 0–4 in the chronic constriction injury model) whereby chronic amitriptyline is efficacious in treating a symptom of neuropathic pain. When initiated at day-6, amitriptyline not only is inefficacious in treating this symptom, it also prolongs the time to the natural dissipation of thermal hyperalgesia evident in this model (Fig. 2C) (Ignatowski et al, 1999, 2005). In a clinical trial examining the effectiveness of amitriptyline in the treatment of chronic pain due to spinal cord injury, amitriptyline was inefficacious in alleviating pain in most patients examined (Cardenas et al, 2002). The authors did acknowledge however, that a small proportion of subjects did benefit from the treatment. Given the narrow therapeutic window in the chronic constriction injury model, our data may help explain that such conflicting responses could arise from subtle differences in the times between injury and treatment initiation. This points to the need to uncover the cellular factors targeted by amitriptyline that produce these observed effects during chronic pain treatment.

A temporal profile similar to that demonstrated here with chronic amitriptyline treatment is also apparent in chronic constriction injured rats receiving either delayed (day-6 post-ligature placement) administration of thalidomide, an inhibitor of TNF synthesis, (Sommer et al, 1998) or continuous i.c.v. microinfusion of TNF-antibodies (Ignatowski et al, 1999). Microinfusion of TNF-antibodies starting at day-4 post-ligature placement abolishes hyperalgesia, whereas if started at day-6 post-ligature placement, TNF-antibodies do not affect chronic constriction injury-induced reductions in paw withdrawal latencies (Ignatowski et al, 1999). Similarly, when initiated at day-6 post-ligature placement, thalidomide is ineffective in alleviating thermal hyperalgesia (Sommer et al, 1998). In comparison, the present data strongly implicate amitriptyline-induced decreases in brain-derived TNF levels as a mechanism of its antinociceptive action during hyperalgesia development, a hypothesis investigated in the current study. In fact, our previous reported findings led us to investigate the effect of treatment with amitriptyline on brain-derived TNF when initiated at the same times as microinfusion of TNF-antibodies as mentioned above (day-4 and day-6 post-ligature placement). Indeed, effective alleviation of thermal hyperalgesia with concomitant amitriptyline treatment is associated with inhibition of pain-induced increases in TNF in the hippocampus (Fig. 5), supporting our hypothesis.

Whereas TNF induces the development of thermal hyperalgesia (Oka et al, 1996), it is also required for the dissipation of thermal hypersensitivity (Ignatowski et al, 2005). Dissimilar to that observed after chronic amitriptyline administration initiated on day-6 post-ligature placement, acute (60 min) amitriptyline treatment of rats at day-8 post-ligature placement abolishes hyperalgesia and enhances total TNF levels in the brain (Ignatowski et al, 2005). This rapid increase in TNF levels in the brain occurs at the time when TNF serves to stimulate norepinephrine release (Ignatowski et al, 2005). Thus, it appears that increased norepinephrine release is required in the brain for alleviation of hyperalgesia. In this regard, amitriptyline-mediated increases in norepinephrine release (direct, through reuptake inhibition and indirect, through regulating TNF production) in the brain may contribute to antinociception by increasing the activity of the descending inhibitory bulbospinal pathway that is inactivated during chronic, neuropathic pain (Ardid et al, 1995). This may explain why inhibition of brain-derived TNF initiated at day-6 post-ligature placement by i.c.v. microinfusion of TNF-antibodies fails to alleviate thermal hyperalgesia (Ignatowski et al, 1999). The similarities between amitriptyline treatment and i.c.v. microinfusion of TNF-antibodies further support our hypothesis that amitriptyline-mediated inhibition of brain-derived TNF during the early development of neuropathic pain constitutes a mechanism of its antinociceptive effect.

The present study confirms an increase in the diameter in ipsilateral sciatic nerves of chronic constriction injured rats. Intriguingly, as thermal hyperalgesia dissipates (Fig. 2, day 20 in the chronic constriction injury model), the diameters of the ipsilateral nerves remain increased, resulting in the positive ‘difference values’ (Fig. 3), supporting previous findings (Sommer et al, 1995). These data show that a decrease in nerve edema is not required for the dissipation of hyperalgesia. Additionally, elimination of the descending noradrenergic inhibitory pathway worsens thermal hyperalgesia (Tsuruoka and Willis, 1996), supporting its supraspinal modulation (Urban and Gebhart, 1999); whereas the development of edema is not affected. Therefore, the local milieu appears to dictate the development and maintenance of edema. While amitriptyline treatment alleviates thermal hyperalgesia, nerve-injury induced edema is not decreased (Fig. 3) supporting previously reported findings (Esser and Sawynok, 1999; Oatway et al, 2003; Sawynok and Reid, 2003; Sawynok et al, 1999). These data demonstrate that amitriptyline affects an aspect of neuroinflammation other than edema. We are aware that a reduction in edema with chronic amitriptyline treatment has been documented in arthritic animals (Butler et al, 1985). This could be due to differences in the mechanisms of inflammatory versus neuropathic pain (Scholz and Woolf, 2002).

Immunoreactivity for TNF in the ligatured nerves is associated with the development and continuation of thermal hyperalgesia (Fig. 4), with enhanced TNF immunoreactive staining observed at day-8 post-ligature placement simultaneous with peak thermal hypersensitivity (Covey et al, 2002). This finding is supported by reports of increased local production of TNF with chronic constriction injury (Shubayev and Myers, 2001, 2002a). At day-8 post-ligature placement, immunoreactive staining for TNF was increased both in the ligatured nerves (Fig. 4A, panel b) and in the hippocampus (Fig. 5A, panel b), and amitriptyline treatment reduced the immunoreactive TNF expression (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5, panel c). Since the tricyclic antidepressant drug, desipramine, decreases immunoreactive staining for TNF in the brains of control rats (Ignatowski and Spengler, 1994; Ignatowski et al, 1997), we hypothesized a similar effect would be observed by amitriptyline on TNF expression. It is noteworthy that in paradigms where chronic amitriptyline treatment effectively alleviates hyperalgesia, it also considerably decreases TNF immunoreactivity in the ipsilateral nerves. While double-labeling for TNF and its cellular source was not undertaken in the present study, considerable evidence supports macrophage, Schwann cells, and neurons as potential sources of TNF. For example, thermal hyperalgesia during chronic constriction injury is temporally related to macrophage influx and sciatic nerve endoneurial TNF expression (Sommer and Schafers, 1998), suggesting that macrophage and Schwann cells may be a prime source of TNF following peripheral nerve injury. In fact, nerve injury-induced early production of TNF by Schwann cells induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 production that along with TNF mediates macrophage recruitment to the injury (Wagner and Myers, 1996b; Shubayev et al, 2006). TNF is also produced within nerves and undergoes axonal transport during peripheral nerve injury (Shubayev and Myers, 2001). Whereas our present and past findings support an induction of TNF synthesis in the brain following peripheral chronic constriction injury (Covey et al, 2000; Spengler et al, 2007), it cannot be excluded that peripheral TNF may be transported into the CNS (Banks et al, 2001; Pan et al, 2007). Therefore, the present findings and the literature strongly support a role for TNF in the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain following peripheral nerve injury.

We report here that an increase in immunoreactive staining for TNF occurs only in the contralateral hippocampus as evaluated at day-8 post-ligature placement (Fig. 5B). Upon staining coronal sections of the ipsilateral hippocampus, we did not observe an increase in staining for TNF (data not shown). A similar lateralization in brain cytokine expression (IL-1β) induced by the spared nerve injury and chronic constriction injury model, as well as in the L5 spinal nerve transection model (TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6), of neuropathic pain have been reported (Apkarian et al, 2006; Liu et al, 2007). We have also reported a switch in α2-adrenoceptor regulation of cyclic AMP production in the contralateral hippocampus at day-8 post-ligature placement in the chronic constriction injury model (Sud et al, 2007). The fact that α2-adrenoceptor activation regulates TNF production (Ignatowski et al, 1996; Nickola et al, 2000; Spengler et al, 1990) through regulation of cyclic AMP (Spengler et al, 1990) provides support for the present effect on the contralateral side. The finding that TNF expression during chronic constriction injury increases in the hippocampus, a region involved in memory formation and pain processing (Delgado, 1955; Dutar et al, 1985; Khanna and Sinclair, 1989; McEwen, 2001; McKenna and Melzack, 1992), reinforces the importance of this region in modulation of pain perception.

Given that chronic amitriptyline administration reverses peripheral α2-adrenoceptor regulation of cyclic AMP (Sud et al, 2007), we hypothesized that a similar role would be revealed for α2-adrenoceptors regulating TNF production. We discovered that as thermal hyperalgesia develops, the nature of α2-adrenoceptor regulation of peripheral TNF production from mononuclear cells reverses, from a pro-inflammatory response in control rats, to an anti-inflammatory response with inhibition of LPS-stimulated TNF production observed ex vivo from rats undergoing chronic constriction injury (Fig. 6A, Fig. 7A). Additionally, the specific α2-adrenoceptor antagonist yohimbine blocks the clonidine-selective response in control macrophage. However, yohimbine no longer blocks the response to clonidine in macrophages from chronic constriction injured rats, that is, when the reversal from potentiation to inhibition of LPS-stimulated TNF production occurs. Whether this indicates a switch in the phenotype of the α-adrenoceptor or a switch in second messenger coupling of the α2-adrenoceptor remains to be elucidated. Induction of α1-adrenoceptors in macrophages is observed in some diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (Heijnen et al, 1996, 2002). Whereas the cytokines TNF and IL-6 are responsible for the up-regulation of α1a-adrenoceptor mRNA in monocytes during arthritis (Heijnen et al, 2002), activation of this receptor enhances the production of TNF and IL-6. The present finding that clonidine stimulation of the α-adrenoceptor on macrophage during chronic constriction injury inhibits TNF production may reflect either binding of clonidine to a non-yohimbine sensitive configuration of the α2-adrenoceptor or induction of a different α-adrenoceptor subtype (α1b- or α1c-adrenoceptor). The contrast in regulation of LPS-stimulated TNF production by α2-adrenoceptor activation at day-4 post-ligature placement between whole blood cultures and peritoneal macrophages may reflect the contribution of accessory cells in whole blood cultures as compared to enriched peritoneal macrophage cultures (Fig. 6A and Fig. 7A). Whether TNF in the brain, which contributes to the development of thermal hyperalgesia (Ignatowski et al, 1999; Oka et al, 1996), also serves as a causative factor in the changes in peripheral α2-adrenoceptor function was tested. Macrophages harvested from rats that were only i.c.v. microinfused with rrTNF, without induction of sciatic nerve injury, revealed a similar reversal in α2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production (Fig. 8). Given that levels of TNF in the peritoneal cavity are not altered during chronic constriction injury (Table 3), or during rrTNF microinfusion (Ignatowski et al, 1999), the abovementioned reversal demonstrates a profound effect of brain-derived TNF on the functioning of immune effector cells in the periphery. A similar transformation in α2-adrenoceptor regulation of peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokine production occurs in a model of acute inflammatory neuritis (Romero-Sandoval et al, 2005). In contrast, in a chronic inflammatory, polyarthritis pain model, adrenergic regulation of TNF production from peripheral macrophages, unlike that observed in this neuropathic pain model, is not transformed to anti-inflammatory, but displays an enhanced pro-inflammatory response (Chou et al, 1996, 1998). This may explain how inflammatory pain is sustained differently than neuropathic pain (Scholz and Woolf, 2002).

Table 3.

Amount of TNF (pg/ml) in the peritoneal cavity as measured using the WEHI-13VAR bioassay.

| PARADIGM | [TNF] (pg/ml) |

|---|---|

| Control | 23.12 ± 15.85 [8] |

| CCI-4 | ND |

| CCI-8 | 3.31 ± 0.62 [5] |

| CCI-16 | 14.47 ± 4.3 [3] |

| AMT(4 days) | ND |

| AMT(8 days) | 10.86 ± 5.6 [5] |

| AMT(16 days) | 15.43 ± 2.99 [5] |

| CCI-4-AMT(0) | 5.49 ± 3.54 [3] |

| CCI-8-AMT(0) | 4.14 ± 0.38 [4] |

| CCI-16-AMT(0) | 22.68 ± 8.17 [3] |

| CCI-8-AMT(4) | 3.56 ± 1.3 [3] |

| CCI-16-AMT(4) | 44.68 ± 7.26 [3] |

| CCI-16-AMT(6) | 41.27 ± 4.98 [3] |

• ND = undetectable, below detection limit of the assay (3 pg/ml).

• Statistical analysis performed using One-Way ANOVA or One-Way ANOVA on Ranks; no significant differences noted amongst the paradigms.

• AMT = amitriptyline (10 mg/kg, i.p.); CCI = chronic constriction injury.

• AMT(4 days), -(8 days), -(16 days) = amitriptyline administration for 4, 8, or 16 days in the absence of CCI.

• CCI-4-AMT(0), CCI-8-AMT(0), CCI-16-AMT(0) = amitriptyline administration initiated at day-0 post-CCI.

• CCI-8-AMT(4), CCI-16-AMT(4) and (6) = amitriptyline administration initiated at either day-4 or day-6 post-CCI, respectively.

• Number of animals indicated in brackets.

The switch in α2-adrenoceptor regulation of TNF production from pro- to an anti-inflammatory response observed in the present study is also evident in macrophages harvested from rats that were only administered amitriptyline i.p. for 16 days (Fig. 6C). Antidepressant drugs, in general, inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production and elicit anti-inflammatory effects (Maes et al, 1999; Xia et al, 1996). It could be argued that since amitriptyline is administered i.p., the ‘anti-inflammatory’ response observed in this study is a local effect. However, i.p. administration of amitriptyline simultaneous with chronic constriction injury accelerates this reversal (Fig. 6C), such that it is evident with only 4 days of amitriptyline administration. Given that this response is not due to changes in TNF levels in the local milieu (Table 3), we hypothesize that this reversal is directed by changes in TNF levels in the brain. Thus, we propose that TNF in the brain regulates sympathetic outflow and therefore influences peripheral α2-adrenoceptors.