Abstract

Recently, we reported that silibinin inhibits primary lung tumor growth and progression in mice and down-regulates iNOS expression in tumors; however, the mechanisms of silibinin action are largely not understood. Also, the activation of signaling pathways inducing various transcription factors are associated with lung carcinogenesis and their inhibition could be an effective strategy to prevent and/or treat lung cancer. Herein, we used human lung epithelial carcinoma A549 cells to explore the potential mechanisms, and observed strong iNOS expression by cytokine mixture (CM, containing 100 U/ml IFN-γ + 0.5 ng/ml IL-1β + 10 ng/ml TNF-α). We also examined the CM-activated signaling cascades which could potentially up-regulate iNOS expression, and then examined the effect of silibinin (50-200 μM) on these signaling cascades. Silibinin treatment inhibited, albeit to different extent, the CM-induced activation of STAT1(Tyr-701), STAT3(Tyr-705), AP-1 family of transcription factors and NF-κB. The results for AP-1 were correlated with the decreased nuclear levels of phospho-c-Jun, c-Jun, Jun B, Jun D, phospho-c-Fos and c-Fos. Further, silibinin also strongly decreased CM-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, but only marginally affected JNK1/2 phosphorylation. Silibinin treatment also decreased constitutive p38 phosphorylation in the presence or absence of CM. Downstream of these pathways; silibinin strongly decreased CM-induced expression of HIF-1α, without any considerable effect on Akt activation. CM-induced iNOS expression was completely inhibited by silibinin. Overall, these results suggest that silibinin could target multiple cytokines-induced signaling pathways to down-regulate iNOS expression in lung cancer cells, and that could contribute to its overall cancer preventive efficacy against lung tumorigenesis.

Keywords: Lung cancer, cancer chemoprevention, silibinin, cytokines, inducible nitric oxide synthase

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer burden worldwide with over 3 million incidences and 1 million deaths annually. In United States, it is the 2nd leading cause of cancer-related incidences and is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths (1). It is estimated that among men, lung cancer alone will kill (31% of total cancer deaths) more than the next three cancers combined i.e. prostate (9%), colon and rectum (9%) and pancreas (6%) (1). Despite extensive research, the overall 5- year survival rate in lung cancer patients is only 8–14% and has improved only marginally during the past 25 years (1, 2). These alarming statistics suggest the need for effective preventive measures to lower the burden of this malignancy. Chemoprevention is a potentially important approach to reduce the large number of lung cancer-related deaths. Numerous studies have found that chemoprevention using phytochemicals, especially flavonoids, can prevent variety of cancers including lung cancer (3-5). In this regard, a large clinical study has suggested the presence of inverse association between flavonoid intake and subsequent lung cancer incidences (6).

Silibinin, a flavonoid, is the major bioactive constituent present in silymarin which is isolated from milk thistle (Silybum marianum), and widely used as a hepatoprotective agent and has been marketed as a dietary supplement. In vitro and in vivo studies have revealed pleiotropic capabilities of silibinin against various epithelial cancers including lung cancer (3, 7-12). Silibinin treatment induces a significant growth inhibition, a moderate cell cycle arrest and a strong apoptotic death in SHP-77 cells (small cell lung carcinoma cells) and A-549 cells (non-small cell lung carcinoma cells) (13). Dietary silibinin (up to 1% w/w) strongly retards the urethane-induced lung tumor growth and progression via inhibition of proliferation and angiogenesis (3). Further, we observed that silibinin suppresses the expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), cyclin D1, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and with profound magnitude, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and microvessel density in lung tumors (3). Silibinin has been shown to inhibit the invasive capability of human lung cancer cells via decreasing the production of urokinase plasminogen activator, metalloproteinase-2, and by enhancing the expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (14). The anti-invasive effect of silibinin in lung cancer cells was related with inhibition of PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways (15). In another study, silibinin suppressed the growth of human non-small cell lung carcinoma A549 xenograft and also enhanced the therapeutic potential of doxorubicin (16). In all in vivo studies, silibinin was reported to be non-toxic and biologically available, therefore could be useful for chemopreventive approach against lung cancer.

During lung carcinogenesis various cytokines, secreted by tumor cells itself or cells in its vicinity, are known to maintain a chronic pro-inflammatory and immunosuppressive condition in the tumor microenvironment (17), and promotes cell proliferation, apoptosis resistance, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis (18). Therefore, understanding of cytokine-induced signaling is vital to comprehend the process of lung carcinogenesis. Herein, we first examined the effect of a defined cytokine mixture (CM), consisting of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), on key cellular signaling molecules namely- signal transducers and activators of the transcription (STAT), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), activator protein-1(AP-1), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), Akt and hypoxia inducing factor-1α (HIF-1α), which regulate the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in human non-small lung cancer A549 cells; followed by use of this model to assess the effect of silibinin on these activated signaling molecules. The mixture of IFN-γ, IL-1β and TNF-α has been used in various studies and has been shown to increase iNOS expression (19-22). Results clearly suggest the efficacy of silibinin in inhibiting the CM-induced signaling pathways as well as expression of iNOS. These mechanistic observations for iNOS expression could be highly relevant, as iNOS is known to promote inflammation and tumor angiogenesis, and associated with growth and progression of lung tumors.

Materials and Methods

Cell Line and Reagents

Human epithelial lung carcinoma A549 cells were from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). RPMI 1640 medium and other cell culture materials were from Invitrogen Corporation (Gaithersberg, MD). Silibinin was from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in DMSO as stock solution. TNF-α, IL-1β and INF-γ were purchased from Biosource (Camarillo, CA). Consensus NF-κB and AP-1 specific oligonucleotides and the gel shift assay system were from Promega (Madison, WI). The primary antibodies for iNOS, phospho-c-Jun, c-Jun, Jun B, Jun D, Fra-1, Fra-2, phospho-c-Fos, p65 and p50 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibodies for phospho- and total ERK1/2, STAT1, STAT3, JNK1/2, p38 and IκBα; and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). The rabbit anti-mouse antibody and ECL detection system was from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ, USA). HIF-1α antibody was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Antibody for β-actin was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Cell Culture and Treatments

A549 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. At about 70% confluency, cultures were switched to serum-free medium for 24h, and then treated with different doses of silibinin (50, 100 and 200 μM) in DMSO for 2h and then stimulated with cytokine mixture (CM = 100U/ml IFN-γ + 0.5 ng/ml IL-1β + 10 ng/ml TNF-α) in serum-free medium from 15 min to 24h. The concentrations of IFN-γ, IL-1β and TNF-α used in the present study were based upon earlier published work (19, 22). An equal amount of DMSO (vehicle) was present in each treatment, including control; DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.1% (v/v) in any treatment. After desired treatments, medium was aspirated, cells were washed two times with cold PBS and total cell lysates or cytosolic and nuclear extracts were prepared as described earlier (23, 24).

Immunoblotting

For immunoblotting, cytosolic extracts or nuclear extracts or total cell lysates (40–80 μg protein per sample) were denatured with 2x sample buffer and samples were subjected to SDS–PAGE on 8 or 12% Tris–glycine gel. The separated proteins were transferred on to nitrocellulose membrane followed by blocking with 5% non-fat milk powder (w/v) in Tris-buffered saline (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 1h at room temperature. Membranes were probed for the protein levels of desired molecules using specific primary antibodies followed by the appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and visualized by ECL detection system. In each case, blots were subjected to multiple exposures on the film to make sure that the band density is in the linear range. The blots were scanned with Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA), and the mean density of each band was analyzed by the Scion Image program (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Each membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody to normalize for differences in protein loading in the densitometric values given below each band.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

For EMSA, NF-κB or AP-1 specific oligonucleotides (3.5 pmol) were end-labeled with γ-32P-ATP (3000 Ci/mmol at 10 mCi/ml) using T4 polynucleotide kinase in 10x kinase buffer as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega, Madison, WI). Labeled double-stranded oligo probe was separated from free γ-32P ATP using a G-25 Sephadex column. The consensus sequences of the oligonucleotides used were: 5’-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3’ and 3’-TCA ACT CCC CTG AAA GGG TCC G-5’ for NF-κB; 5’-CGC TTG ATG AGT CAG CCG GAA-3’ and 3’-GCG AAC TAC TCA GTC GGC CTT-5’ for AP-1. For EMSA, 4 or 8 μg protein (for AP-1 and NF-κB, respectively) from nuclear extracts was first incubated with 5x gel shift binding buffer [20% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl and 0.25 mg/ml poly (dI-dC) poly (dI-dC)] and then with 32P-end-labeled consensus oligonucleotide for 20 min at 37°C. DNA–protein complexes thus formed were resolved on 6% DNA retardation gels (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD). In supershift assay, samples were incubated with anti-p65, anti-p50, anti-c-Jun, anti-c-Fos, anti-Jun B, anti-Jun D, anti-Fra-1, anti-Fra-2 or anti-Fos B antibody before the addition of 32P end-labeled NF-κB or AP-1 oligo. DNA-protein or DNA-protein-antibody complexes thus formed were resolved on 6% DNA retardation gels. To check the specificity of DNA binding only labeled probe sample was also run together with other samples. In each case, the gel was dried and bands were visualized by autoradiography.

Results

CM Treatment Activates Various Signaling Pathways in A549 Cells

Various studies have shown the role of transcription factors (STAT, AP-1, NF-κB and HIF-1α), mitogen-activated protein kinases (ERK1/2, JNK1/2 and p38) and iNOS expression in lung tumorigenesis (25-27). In the present study, we first analyzed the effect of a defined cytokine mixture (CM, containing 100 U/ml IFN-γ + 0.5 ng/ml IL-1β + 10 ng/ml TNF-α) on these key signaling molecules at various time points (30 min to 24h). CM exposure resulted in increased phosphorylation of STAT1 (Tyr-701) and STAT3 (Tyr-705) as early as 30 min, after which there was a gradual decrease in the phosphorylation, without having any considerable effect on STAT3 (Ser-727) phosphorylation which was constitutively activated in A549 cells (Fig. 1A). The total level of STAT1 showed an increase starting from 6h, however, no considerable effect was observed on total STAT3 level (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Time course effect of CM on the activation of STAT, AP-1 and NF-κB in human lung epithelial A549 cells. A, Time course (30 min to 24h) expression of pSTAT1 (Tyr-701), STAT1, pSTAT3 (Tyr-705), pSTAT3 (Ser-727) and STAT3 with CM treatment in total cell lysate as described in the ‘Materials and Methods’. First lane is control i.e. without CM. In all cases, membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody for protein loading correction. The densitometry data presented below the bands are ‘fold change’ as compared with control after normalization with respective loading control value. B, DNA binding of AP-1 at various time points with CM treatment as measured by EMSA. C, Gel-super shift assay was performed to examine the specific constituents of AP-1 after CM treatment for 24h. D, DNA binding of NF-κB at various time points with CM treatment as measured by EMSA. Gel super-shift assay was performed to examine the constituents of NF-κB after 30 min treatment with CM. The data shown are representative of at least two independent experiments.

We next examined the effect of CM on transcription factors AP-1 and NF-κB. EMSA results showed that there was a gradual increase in AP-1 DNA binding ability and it reaches to a maximum level at 24h of treatment (Fig. 1B). AP-1 is a dimeric complex of various combination of Jun family (c-Jun, Jun B and Jun D) and Fos family members (c-Fos, Fos B, Fra-1 and Fra-2). Gel-super shift assay revealed the various constituents of AP-1 complex namely- c-Jun, c-Fos, Jun B, Jun D, Fra-1, Fra-2 and Fos B (Fig. 1C); among these constituents, c-Jun, Jun D and Fra-2 were identified as key constituents in CM-induced active AP-1 complex (Fig. 1C). CM also increased the NF-κB activation maximally after 30 min of treatment and then gradually decreased nearly to the basal level after 24h of treatment (Fig. 1D). We also observed increased nuclear localization of p65, and IκB phosphorylation (Ser-32) and degradation as early as 15 min of CM treatment (data not shown). Gel-super shift assay identified the p65 and p50 as the constituents of NF-κB (Fig. 1D).

CM treatment also increased the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 maximally by 30 min (Fig. 2A). ERK1/2 phosphorylation declined in a biphasic manner, while JNK1/2 phosphorylation declined steadily to the basal level by 24h (Fig. 2A). P38 was constitutively activated in A549 cells and CM exposure decreased its phosphorylation and by 12h it was undetectable, while there was no change in the total p38 levels (Fig. 2A). CM also increased the Akt phosphorylation after 30 min which remained phosphorylated even after 24h of treatment, but there was a decline in the total Akt levels (Fig. 2A). Under similar treatment conditions, CM treatment increased the expression of transcriptional factor HIF-1α, with maximal expression after 24h of treatment (Fig. 2B). Further, CM strongly increased the iNOS expression as early as 30 min, with the maximum level after 24h of treatment (Fig. 2C). These results suggested that most of the transcription factors and signaling molecules are activated after 30 min of CM treatment which was, next, used to examine the effect of silibinin pre-treatment (2h before CM exposure) on the CM-induced signaling cascades in A549 cells.

Figure 2.

Time course effect of CM on the activation of MAPKs and Akt, and expression of HIF-1α and iNOS in A549 cells. A-C, Time course (30 min to 24h) expression of pERK1/2, ERK1/2, pJNK1/2, JNK1/2, p-p38, p38, pAkt, Akt, HIF-1α and iNOS with CM treatment in total cell lysate as described in the ‘Materials and Methods’. In all cases, membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody for protein loading correction. The densitometry data presented below the bands are ‘fold change’ as compared with control after normalization with respective loading control value. The data shown are representative of at least two independent experiments. ND: Not detectable.

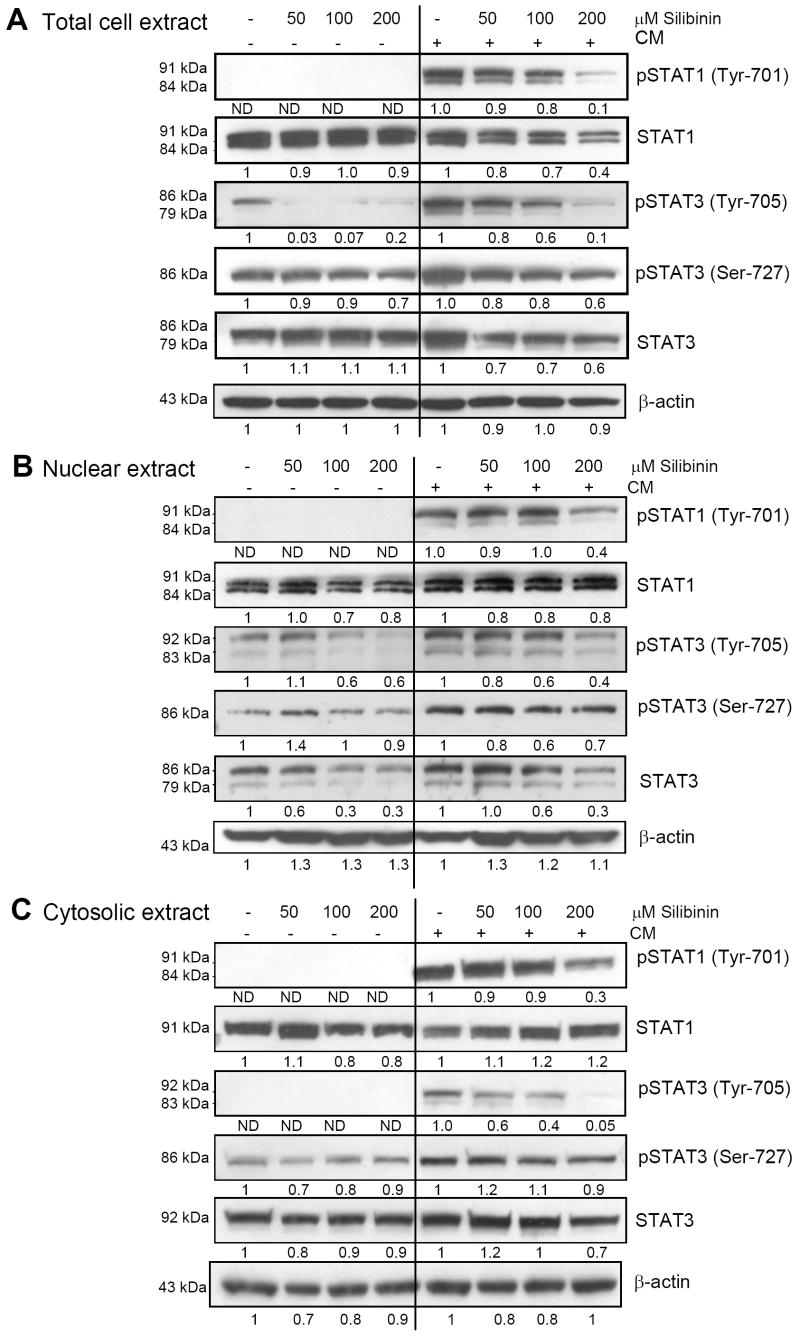

Effect of Silibinin on CM-induced Activation of STAT1 and STAT3 in A549 Cells

STAT is broadly known as oncogene which regulates broadly diverse biological processes, including cell proliferation, transformation, apoptosis, differentiation, angiogenesis, inflammation and immune response (26, 28, 29). Herein, we analyzed the effect of silibinin pre-treatment (2h) on the increased STAT phosphorylation caused by 30 min exposure to CM in A549 cells. Silibinin pre-treatment (50-200 μM) strongly reduced the CM-induced phosphorylation of STAT1 (Tyr-701) in the total cell lysates. Silibinin treatment also decreased the total STAT1 level compare to CM treatment alone (Fig. 3A). Further, silibinin pre-treatment strongly inhibited the phosphorylation of un-induced as well as CM-induced STAT3 at Tyr-705 site, while moderately inhibited the phosphorylation at Ser-727 site. Silibinin treatment moderately decreased the CM-induced level of total STAT 3 (Fig. 3A). Since nuclear localization of STAT is necessary for its transcriptional function, we next analyzed the effect of silibinin on STAT phosphorylation and total STAT levels in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. Similar as in total cell extract, the inhibitory effect of silibinin on STAT activation was also evidenced in nuclear (Fig. 3B) and cytosolic extracts (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Effect of silibinin on CM-induced STAT activation in human lung epithelial A549 cells. A-C, The effect of silibinin pre-treatment for 2h on the expression of pSTAT 1 (Tyr-701), STAT1, pSTAT 3 (Tyr-705), pSTAT 3 (Tyr-727) and STAT3 in the presence (for 30 min) or absence of CM in total-, nuclear- and cytoplasmic lysates. In all cases, membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody for protein loading correction. The densitometry data presented below the bands are ‘fold change’ as compared with control after normalization with respective loading control value. The data shown are representative of at least two independent experiments. The line in the middle of the blots is to separate the effect of silibinin on constitutive (left) or CM modulated (right) expression of the molecules shown. ND: Not detectable.

Effect of Silibinin on CM-induced Activation of AP-1 in A549 Cells

AP-1 transcription factor is crucial for regulating the cell proliferation, death, transformation, inflammation and innate immunity response (30-32). In the present study silibinin pre-treatment (2h) at 100 and 200 μM doses inhibited the DNA binding activity of AP-1, which was induced by 30 min exposure to CM in A549 cells (Fig. 4A). Constitutively active AP-1 was also decreased by silibinin treatment (maximum inhibition at 100 μM dose) (Fig. 4A). Since AP-1 is composed of either homo- or heterodimers between members of Jun and Fos families, and the expression of AP-1 subunits is differentially regulated in response to various stimuli, we next analyzed the effects of silibinin on the AP-1 subunits. The levels of Jun and Fos family members were measured by western blot analysis in the nuclear lysates. As shown in Fig. 4B, silibinin pre-treatment (2h), 30 min before exposure to CM, resulted in a marginal to strong decrease in the CM-induced expression of phosphorylated c-Jun and c-Fos as well as total levels of c-Jun, Jun B, Jun D and c-Fos. But under similar treatment conditions silibinin did not affect the Fra-1 and Fra-2 levels in the nuclear lysates (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of silibinin on CM-induced AP-1 activation and expression of AP-1 constituents in human lung epithelial A549 cells. A, EMSA was performed in the nuclear extract to analyze the effect of silibinin pre-treatment for 2h on AP-1 activation in the presence (for 30 min) or absence of CM as described in the ‘Materials and Methods’. B, Nuclear extract was also analyzed for the expression of p-c-Jun, c-Jun, Jun B, Jun D, p-c-Fos and c-Fos. The densitometry data presented below the bands are ‘fold change’ as compared with control after normalization with respective loading control value. Blots shown are representative of at least two independent experiments. The line in the middle of the blots is to separate the effect of silibinin on constitutive (left) or CM modulated (right) expression of the molecules shown. ND: Not detectable.

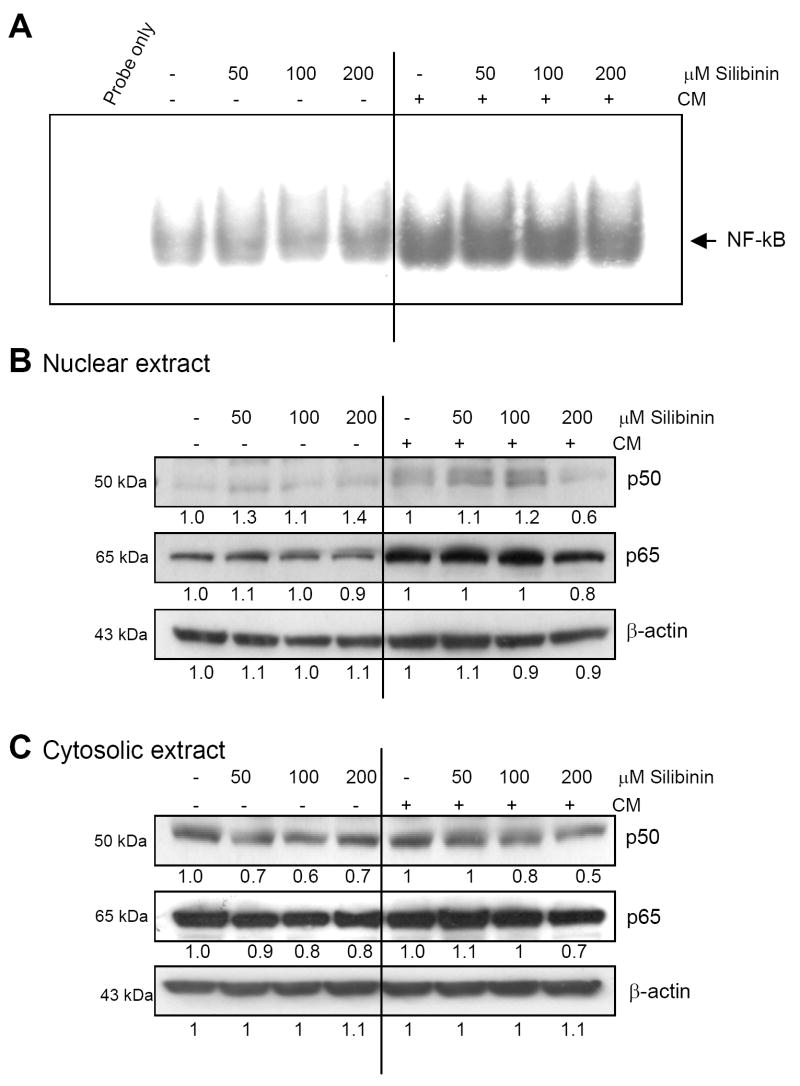

Effect of Silibinin on CM-induced NF-κB Activation in A549 Cells

NF-κB has been shown to regulate the expression of a number of genes whose products are involved in tumorigenesis (33). In the present study, CM treatment for 30 min caused a strong activation of constitutively active NF-κB as evidenced by EMSA results which was moderately inhibited by pre-treatment with the highest dose of silibinin (Fig. 5A). Western blot analysis of nuclear extracts revealed that silibinin at 200 μM dose moderately inhibited the CM-activated p50 nuclear level, but only marginally affected the p65 level (Fig. 5B). Silibinin treatment also resulted in a moderate to marginal decrease in the expression of p50 and p65 in the presence or absence of CM in the cytosol (Fig. 5C). Thus, the moderate inhibitory effect of silibinin on CM-induced NF-κB activation was mediated via an overall decrease in the levels of its constituents (mainly the levels of p50).

Figure 5.

Effect of silibinin on CM-induced NF-κB activation and expression of NF-κB constituents in human lung epithelial A549 cells. A, EMSA was performed in the nuclear extracts to analyze the effect of silibinin pre-treatment for 2h on NF-κB activation in the presence (for 30 min) or absence of CM as described in the ‘Materials and Methods’. B &C, Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were also analyzed for the expression of p50 and p65. The densitometry data presented below the bands are ‘fold change’ as compared with control after normalization with respective loading control value. Blots shown are representative of at least two independent experiments. The line in the middle of the blots is to separate the effect of silibinin on constitutive (left) or CM modulated (right) expression of the molecules shown.

Effect of Silibinin on CM-modulated Levels of MAPKs in A549 Cells

MAPK cascade, consisting of ERK1/2, JNK1/2 and p38 kinases, plays a critical role in lung tumorigenesis (30, 34). Several studies have elucidated the functional role of MAPK in the regulation of cytokine production and activation of inflammatory cells (35, 36). In the present study, CM treatment for 30 min increased the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and silibinin pretreatment for 2h, even at the lowest dose i.e. 50 μM, inhibited this activation without any change in the total ERK1/2 levels (Fig. 6A). We next assessed the effect of silibinin on the JNK1/2 and p38 under serum-starved condition as well as in the presence of CM. Silibinin pre-treatment only marginally decreased the CM-induced JNK1/2 phosphorylation, and there was no change in the total JNK1/2 levels under similar treatment conditions (data not shown). As mentioned earlier, CM treatment decreased the constitutive phosphorylation of p38 which was strongly decreased by silibinin pre-treatment for 2h, at the highest used dose i.e. 200 μM, without any noticeable changes in total p38 levels (Fig. 6A). Silibinin treatment did not cause any noticeable change in the CM-induced phosphorylation of Akt (Ser-473) (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Inhibitory effect of silibinin on CM-modulated ERK1/2, p38, HIF-1α and iNOS expression in A549 cells. A-C, Effect of silibinin pre-treatment for 2h on the expression of pERK1/2, ERK1/2, p-p38, p38, HIF-1α and iNOS in the presence (for 30 min) or absence of CM. The densitometry data presented below the bands are ‘fold change’ as compared with control after normalization with respective loading control value. The data shown are representative of at least two independent experiments. The line in the middle of the blots is to separate the effect of silibinin on constitutive (left) or CM modulated (right) expression of the molecules shown. D, The proposed mechanism for the inhibitory effects of silibinin on cytokine-induced signaling cascades regulating iNOS expression in A459 cells. Abbreviations: IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; JAK, janus activated kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; IKK, inhibitor of kappa B kinase; IκB, inhibitor of kappa B; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducing factor-1α; AP-1, activator protein-1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase. ND: Not detectable.

Effect of Silibinin on CM-induced HIF-1α Levels in A549 Cells

HIF-1α is known to get activated in response to hypoxia and helps to restore oxygen homeostasis in cells by inducing glycolysis, erythropoiesis and angiogenesis; promoting cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis (37). In the present study, we observed that the level of HIF-1α was increased with CM stimulation for 30 min and this could be probably linked with activation of MAPKs and Akt, which are known to regulate the HIF-1α expression at transcriptional level (37). Silibinin pre-treatment (50-200 μM) dose-dependent decreased the CM-induced HIF-1α expression in A549 cells (Fig. 6B).

Effect of Silibinin on CM-induced iNOS Levels in A549 Cells

Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is an enzyme involved in production of nitric oxide (NO) via catalyzing the conversion L-arginine to citrulline in the presence of NADPH and oxygen. NO plays a key role in many physiological as well as pathological processes, including inflammation, angiogenesis and neoplasia (25). As mentioned earlier CM treatment for 30 min resulted in a strong activation of iNOS, next we examined the effect of silibinin pre-treatment on the CM-induced iNOS expression. As shown in Fig. 6C, silibinin pre-treatment (50-200 μM) completely inhibited the CM-induced expression of iNOS in A549 cells.

Discussion

Lung cancer has the highest mortality worldwide, which is in part due to its high potential of progression, local invasion and metastasis to distant organs. Lung cancer is also highly resistant to conventional cancer therapies and, although survival rates have been improved slightly in recent years, more than 90% of patients diagnosed with lung cancer die from their disease (1, 2). Therefore, identification of the mechanisms preventing or controlling the development and progression of this deadly disease is urgently required to devise more effective lung cancer management strategies. In this study we showed that cytokine mixture consisting of TNF-α, IL-1β and IFN-γ activates various cellular signaling cascades known to be involved in the lung cancer growth and progression; and silibinin pre-treatment differentially inhibited (marginal to strong) these signaling cascades. Even though, the cytokine mixture has been used earlier for various studies, the present work is perhaps the first approach to examine the effect of a define mixture of cytokines on such a repertoire of cellular signaling molecules. Importantly, this model could be used to study the efficacy of other cancer chemopreventive drugs.

A large volume of evidence has established that STAT activation occurs frequently in malignant tumors including lung cancer (28), and blocking constitutively activated STAT signaling leads to apoptosis of tumor cells, but not in normal cells (26). Moreover, STAT signaling inhibition might increase the effectiveness of conventional treatment modalities (chemotherapy, radiotherapy), as their failure/resistance might be ascribed to the presence of constitutively activated STAT proteins (26). In the present study, silibinin treatment strongly inhibited the CM-induced STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation and also decreased their expression levels in lung cancer A549 cells, and thus it could, in part, account for the antitumor activity of silibinin against lung cancer (3, 16).

MAPK signaling involving ERK, JNK and p38 is known to play central role in tumor progression via promoting cell proliferation and anti-apoptotic action (30). These MAPKs respond differently depending upon the nature and extent of stimulus, but generally converge and stimulate the activation of transcriptional factor AP-1. AP-1 plays a key role in various processes related to carcinogenesis. In human lung carcinoma cell line, a transient transfection assay has shown that AP-1 activation is important for the induction of iNOS transcription (38). In the present study we observed a strong increase in AP-1 activation with CM treatment. The CM treatment also resulted in increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and JNK1/2 (maximally after 30 min) but with a consistent decrease in p38 phosphorylation level suggesting the differential effect of CM on MAPKs. However, further studies are needed to understand the significance of these differential effects of CM on MAPKs. Nevertheless, silibinin treatment significantly decreased the CM-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 as well as AP-1, but only marginally decreased the constitutively active and CM-induced levels of JNK1/2 (data not shown). Silibinin was also shown to inhibit the phosphorylation of p38 in the presence (at 200 μM dose) or absence (at 50, 100 and 200 μM doses) of CM. These results suggest the differential inhibitory effect of silibinin on the activation of MAPK members in lung cancer A549 cells, and that may, in part, account for its antiproliferative and antitumor effects against lung tumorigenesis (3, 16).

NF-κB is an important link between inflammation and cancer development and has role in the malignant conversion and progression of cancer (39). NF-κB signaling pathway gets activated by various pro-inflammatory cytokines and regulate the expression of many genes whose products can suppress tumor cell death; stimulate tumor cell cycle progression; and provide newly emerging tumors with an inflammatory microenvironment that supports their progression, invasion of surrounding tissues, angiogenesis, and metastasis (33, 39, 40). In earlier studies we observed that doxorubicin treatment resulted in activation of NF-κB in A549 cells and silibinin treatment increased the therapeutic potential of doxorubicin by inhibiting the NF-κB activation (16). In the present work cytokine mixture activated the NF-κB and silibinin treatment moderately inhibited it at 200 μM dose, which might result in reduced expression of various pro-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic or survival factors. Further studies are warranted to understand these aspects of silibinin action.

HIF-1α is known to be activated in response to hypoxic conditions in the tumors and in initiating the process of angiogenesis by inducing the expression of several angiogenesis-related genes, including iNOS, VEGF etc (37). In addition to hypoxia, HIF-1α expression is regulated by many growth factors, such as EGF, IGF, insulin and PDGF involving EGFR, MAPK and PI3K pathways (37). In the present study we observed that CM exposure resulted in increased levels of HIF-1α in A549 cells. To our knowledge this is the first study suggesting that cytokines treatment could increase the expression of HIF-1α levels in lung cancer cells. Further studies are needed to understand the mechanism of HIF-1α increase by CM, but results clearly suggest that silibinin treatment significantly inhibits the CM-induced HIF-1α levels.

The levels of NOS protein and/or NOS activity has been positively correlated with the degree of malignancy in number of human cancers, including lung cancer (38, 41). iNOS mediated production of NO facilitates neo-vascularization, and therefore could be a potential target to control tumor angiogenesis (25). It has been observed that iNOS expression/activity in tumors is higher than the surrounding normal tissues, and that it shows a positive correlation with angiogenic state and metastatic potential of the tumor (25). Furthermore, nitric oxide promotes tumor invasiveness by altering the balance between expression of MMP-2 and its inhibitors TIMP2 and TIMP3 (41). A recent study showed that carcinogen-induced lung tumorigenesis is inhibited in iNOS null mice, which also showed decreased levels of VEGF (42). Therefore, the inhibition of iNOS has been shown to have significant anti-tumor and anti-metastatic effects. In this regard we have reported that iNOS is the important target for silibinin’s angiopreventive efficacy in urethane-induced lung tumor progression in mice (3). In the present work silibinin treatment completely inhibited the cytokines-induced iNOS expression further suggesting iNOS as potential target of silibinin in angioprevention of lung cancer (Fig. 6D). More importantly, iNOS gene promoter has binding sites for STAT, AP-1, NF-κB and HIF-1α transcription factors, which may cooperate for its maximum expression (Fig. 6D). Since the activation of all these four transcription factors by cytokines was inhibited by silibinin, it may account for the most likely mechanism of the down-regulation of iNOS expression observed in lung cancer cells (Fig. 6D).

The significance of the present study lies in the context that cytokines secreted by tumor cells and its microenvironment, are the important determinants of cancer progression. The present work highlights that an anticancer agent such as silibinin can inhibit cytokines-induced survival, mitogenic, inflammatory and angiogenic signaling, which could account for its chemopreventive action against lung cancer.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Cancer Institute grant RO1 CA113876.

Abbreviations

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducing factor-1α

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- NO

nitric oxide

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- CM

cytokine mixture

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JR, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenase as a target in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4266s–69s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-040014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh RP, Deep G, Chittezhath M, et al. Effect of silibinin on the growth and progression of primary lung tumors in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:846–55. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh RP, Agarwal R. Natural flavonoids targeting deregulated cell cycle progression in cancer cells. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:345–54. doi: 10.2174/138945006776055004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deep G, Agarwal R. Chemopreventive efficacy of silymarin in skin and prostate cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:130–45. doi: 10.1177/1534735407301441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knekt P, Jarvinen R, Seppanen R, et al. Dietary flavonoids and the risk of lung cancer and other malignant neoplasms. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:223–30. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deep G, Singh RP, Agarwal C, Kroll DJ, Agarwal R. Silymarin and silibinin cause G1 and G2-M cell cycle arrest via distinct circuitries in human prostate cancer PC3 cells: a comparison of flavanone silibinin with flavanolignan mixture silymarin. Oncogene. 2006;25:1053–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu M, Singh RP, Dhanalakshmi S, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits inflammatory and angiogenic attributes in photocarcinogenesis in SKH-1 hairless mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3483–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyagi AK, Agarwal C, Singh RP, Shroyer KR, Glode LM, Agarwal R. Silibinin down-regulates survivin protein and mRNA expression and causes caspases activation and apoptosis in human bladder transitional-cell papilloma RT4 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:1178–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raina K, Blouin MJ, Singh RP, et al. Dietary feeding of silibinin inhibits prostate tumor growth and progression in transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11083–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh RP, Deep G, Blouin MJ, Pollak MN, Agarwal R. Silibinin suppresses in vivo growth of human prostate carcinoma PC-3 tumor xenograft. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2567–74. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyagi A, Raina K, Singh RP, et al. Chemopreventive effects of silymarin and silibinin on N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine induced urinary bladder carcinogenesis in male ICR mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3248–55. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma G, Singh RP, Chan DC, Agarwal R. Silibinin induces growth inhibition and apoptotic cell death in human lung carcinoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu SC, Chiou HL, Chen PN, Yang SF, Hsieh YS. Silibinin inhibits the invasion of human lung cancer cells via decreased productions of urokinase-plasminogen activator and matrix metalloproteinase-2. Mol Carcinog. 2004;40:143–9. doi: 10.1002/mc.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen PN, Hsieh YS, Chiou HL, Chu SC. Silibinin inhibits cell invasion through inactivation of both PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;156:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh RP, Mallikarjuna GU, Sharma G, et al. Oral silibinin inhibits lung tumor growth in athymic nude mice and forms a novel chemocombination with doxorubicin targeting nuclear factor kappaB-mediated inducible chemoresistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8641–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin WW, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1175–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peebles KA, Lee JM, Mao JT, et al. Inflammation and lung carcinogenesis: applying findings in prevention and treatment. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:1405–21. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.10.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu SC, Marks-Konczalik J, Wu HP, Banks TC, Moss J. Analysis of the cytokine-stimulated human inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) gene: characterization of differences between human and mouse iNOS promoters. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:871–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon S, George SC. Synergistic cytokine-induced nitric oxide production in human alveolar epithelial cells. Nitric Oxide. 1999;3:348–57. doi: 10.1006/niox.1999.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dwyer-Nield LD, Srebernak MC, Barrett BS, et al. Cytokines differentially regulate the synthesis of prostanoid and nitric oxide mediators in tumorigenic versus non-tumorigenic mouse lung epithelial cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1196–206. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marks-Konczalik J, Chu SC, Moss J. Cytokine-mediated transcriptional induction of the human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene requires both activator protein 1 and nuclear factor kappaB-binding sites. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22201–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zi X, Feyes DK, Agarwal R. Anticarcinogenic effect of a flavonoid antioxidant, silymarin, in human breast cancer cells MDA-MB 468: induction of G1 arrest through an increase in Cip1/p21 concomitant with a decrease in kinase activity of cyclin-dependent kinases and associated cyclins. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1055–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller MM, Schreiber E, Schaffner W, Matthias P. Rapid test for in vivo stability and DNA binding of mutated octamer binding proteins with ’mini-extracts’ prepared from transfected cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6420. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh RP, Agarwal R. Inducible nitric oxide synthase-vascular endothelial growth factor axis: a potential target to inhibit tumor angiogenesis by dietary agents. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:475–83. doi: 10.2174/156800907781386632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karamouzis MV, Konstantinopoulos PA, Papavassiliou AG. The role of STATs in lung carcinogenesis: an emerging target for novel therapeutics. J Mol Med. 2007;85:427–36. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shishodia S, Koul D, Aggarwal BB. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor celecoxib abrogates TNF-induced NF-kappa B activation through inhibition of activation of I kappa B alpha kinase and Akt in human non-small cell lung carcinoma: correlation with suppression of COX-2 synthesis. J Immunol. 2004;173:2011–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Du H, Qin Y, Roberts J, Cummings OW, Yan C. Activation of the signal transducers and activators of the transcription 3 pathway in alveolar epithelial cells induces inflammation and adenocarcinomas in mouse lung. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8494–503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer T, Vinkemeier U. STAT nuclear translocation: potential for pharmacological intervention. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:1355–65. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.10.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mossman BT, Lounsbury KM, Reddy SP. Oxidants and signaling by mitogen-activated protein kinases in lung epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:666–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0047SF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujii H. Anti-inflammatory action of PPARs. Nippon Rinsho. 2005;63:609–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imler JL, Wasylyk B. AP1, a composite transcription factor implicated in abnormal growth control. Prog Growth Factor Res. 1989;1:69–77. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(89)90001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shishodia S, Aggarwal BB. Nuclear factor-kappaB activation: a question of life or death. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;35:28–40. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2002.35.1.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adjei AA. The role of mitogen-activated ERK-kinase inhibitors in lung cancer therapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 2005;7:221–3. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2005.n.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung KF. Cytokines as targets in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:675–81. doi: 10.2174/138945006777435263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duan W, Chan JH, Wong CH, Leung BP, Wong WS. Anti-inflammatory effects of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor U0126 in an asthma mouse model. J Immunol. 2004;172:7053–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–32. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JK, Choi SS, Won JS, Suh HW. The regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression induced by lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in C6 cells: involvement of AP-1 and NFkappaB. Life Sci. 2003;73:595–609. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00317-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright JG, Christman JW. The role of nuclear factor kappa B in the pathogenesis of pulmonary diseases: implications for therapy. Am J Respir Med. 2003;2:211–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03256650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orucevic A, Bechberger J, Green AM, Shapiro RA, Billiar TR, Lala PK. Nitric-oxide production by murine mammary adenocarcinoma cells promotes tumor-cell invasiveness. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:889–96. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990611)81:6<889::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kisley LR, Barrett BS, Bauer AK, et al. Genetic ablation of inducible nitric oxide synthase decreases mouse lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6850–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]