Abstract

A growing body of literature finds gender differences in ADHD. However, little is known about the causes of these differences. One possibility is that ADHD risk genes have sexually dimorphic effects. We have investigated four ADHD candidate genes (COMT, SLC6A2, MAOA, SLC6A4) for which there is evidence of sexually dimorphic effects. Past neurobiological and genetic studies suggest that COMT, and SLC6A4 variants may have a greater influence on males and that SLC6A2, and MAOA variants may have a greater influence on females. Our results indicate that genetic associations are stronger when stratified by sex and in the same direction as the previous neurobiological studies indicate: associations were stronger in males for COMT, SLC6A4 and stronger in females for SLC6A2, MAOA. Moreover, we found a statistically signficant gender effect in the case of COMT (P=0.007) when we pooled our work with a prior study. In conclusion, we have found some evidence suggesting that the genetic association for these genes with ADHD may be influenced by the sex of the affected individual. Although our results are not fully validated yet, they should motivate further investigation of gender effects in ADHD genetic association studies.

It has become widely recognized that ADHD occurs in both boys and girls (Arnold 1996), extends into adulthood (Faraone 2000; Faraone and others 2000b), and is marked by significant morbidity and dysfunction. Like males, females with ADHD are at significantly increased risk for academic and interpersonal deficits as well as psychiatric comorbidity (Biederman and others 1999; Biederman and others 2004; Hinshaw 2002) and executive dysfunction (Seidman and others 2005a; Seidman 2006; Seidman and others 2006).

At the same time, a growing literature documents gender differences in ADHD. Most notably, the population prevalence of the disorder is higher in boys compared with girls (Szatmari 1982). Because of the paucity of research on female ADHD, until recently the extant literature has provided equivocal findings (Berry and others 1985; Breen and Altepeter 1990; Faraone and others 1991; Horn and others 1989; James and Taylor 1990; Kashani and others 1979). Compared with boys, girls with ADHD are more likely to be inattentive, less likely to manifest disruptive behavior disorders, and less likely to have major depression (Abikoff and others 2002; Biederman and others 2002). Although some groups have found no association between gender and DSM-IV ADHD subtypes (Eiraldi and others 1997; Faraone and others 1998; Gaub and Carlson 1997a), others report that ADHD girls are more likely to have the inattentive type than boys (Biederman and others 2002).

It is not clear whether these gender differences are reflected in gender differences in brain structure or function. As documented by Valera et al. (2007) and Seidman (2005b), data on structural brain abnormalities in ADHD has been based on studies comprising largely males. In one notable exception, Castellanos at el (2001) showed reductions in ADHD girls in the posterior inferior vermis and the left caudate with trends toward reductions in the right caudate and left frontal regions but did not show the same reductions found in boys for other regions of the cerebellum and the right globus pallidus.

Little is known about the causes of gender differences in ADHD. Given that ADHD is known to have a robust genetic component (Faraone and others 2005), it is possible that different genetic pathways mediate genetic susceptibility to ADHD and that these different pathways create a differential expression of ADHD symptoms and associated features by gender. Several studies have tested a “genetic dose” model, which assumes girls, in comparison with boys, need more risk alleles to develop ADHD. This model predicts that relatives of girls should be at greater risk for ADHD compared with relatives of ADHD boys. This pattern has not been seen in most family studies (Bhatia and others 1991; Faraone and others 1991; Faraone and others 2000a; James and Taylor 1990; Kashani and others 1979; Pauls and others 1983) and twin studies find the heritability of ADHD does not differ by gender (Gjone and others 1996; Goodman and Stevenson 1989; Rhee and others 1999; Silberg and others 1996). Taken together, this work suggests that the differing prevalence of ADHD between males and females cannot be attributed to a “genetic dose” model.

Another possibility is that ADHD risk genes have sexually dimorphic effects. We have previously investigated the genes regulating catecholo-methyltransferase (COMT), the norepinephine transporter (SLC6A2), monamine oxidase-A (MAOA), and the serotonin transporter (SLC6A4) and found some evidence of association with ADHD. For each of these genes, genetic and neurobiological studies have found sexually dimorphic effects.

COMT deficient mice exhibit sexually dimorphic and region specific changes in dopamine activity (Gogos and others 1998) and the Met allele of the Val158Met functional polymorphism has been consistently associated with aggressive and impulsive behavior in humans, especially in males (Gogos and others 1998; Lachman and others 1996). There are also reports of sexual dimorphism of COMT with alcoholism, anxiety, aggression (Bilder and others 2004). A study of SLC6A2 knockout mice found that females were more vulnerable to anxiogenic challenges than male mice (Keller and others 2006). A study of sex differences in the stress responsiveness of the brain noradrenergic system indicated that females were more vulnerable to stress-induced psychiatric disorders (Curtis and others 2006). One animal study found evidence of a sexually dimorphic effect in mice with deficient MAOA (Cases and others 1995). Other genetic association studies of psychiatric disorders have also reported sexually dimorphic effect of this gene (Deckert and others 1999; Herman and others 2005). Moreover, genes such as MAO-A, which is located on X-chromosome, can directly affect sexual dimorphism independent of the influence of sex hormones (Skuse 2006). In SLC6A4 knockout mice study, females had greater increases (79%) in brain serotonin synthesis than males (25%) which suggests that males are more vulnerable to decreased serotonin levels (Kim and others 2005a; Kim and others 2005b). A brain imaging study of SLC6A4 availability in depressed patients also displayed a sex-specific pattern (Staley and others 2006). Previously, a QTL mapping study for blood serotonin levels identified one SLC6A4 SNP (rs2066713) that was significantly associated with decreased blood serotonin levels in men (p=0.0003) but not in women (p>0.1) (Weiss and others 2005). The above biological studies support the existence of sexually dimorphic effects for COMT, SLC6A2, MAOA, and SLC6A4. These genes are also implicated in the etiology of ADHD, since they are involved in the regulation of catecholaminergic neurotransmission. If it turns out that they really are involved in the pathophysiology of ADHD, it is plausible that these genes may play a stronger role in one sex than in the other sex in light of their previous gender specific effects.

Two prior ADHD genetic studies detected sexual dimorphic effects (Guimaraes and others 2007; Qian and others 2003). Qian et al (2003) investigated the Val158Met polymorphism of COMT in Han Chinese ADHD patients (202 nuclear families; 340 cases and 226 controls). No evidence of association was observed in the full sample, but stratification by gender revealed nominally significant overtransmission (p=0.05) of the Met (A) allele to males but not to females in the family sample. In addition, they found significant overrepresentation (p=0.04) of the Val allele in female ADHD patients but not in male patients. In another recent study, Guimaraes et al (2007) investigated the His452Tyr polymorphism of HTR2A in 243 Brazilian ADHD trios. No evidence of biased transmission was found in the full sample but the investigators did observe preferential transmission when the analyses were confined to males only (p=0.04).

Given the importance of gender differences in ADHD along with prior evidence of differential associations by gender, in this study we sought to determine if there were gender differences in evidence for the association of COMT, SLC6A2, MAOA and SLC6A4 with ADHD.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The current analyses are derived from family studies of ADHD and bipolar disorder being conducted at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Subjects from our case-control family studies of boys and girls with ADHD (Biederman and others 1992; Biederman and others 1999) were referred from psychiatric and pediatric sources. Psychiatric probands were selected from consecutive referrals to a pediatric psychopharmacology program. This site is not a tertiary care clinic, since approximately 50% of new patients have never been diagnosed or treated before. Pediatrically-referred probands with ADHD came from a large Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) in the Boston area.

For these studies, screening and recruitment occurred prior to the publication of DSM-IV; thus, initial affection status for individuals and their relatives was based on DSM-IIIR criteria; however lifetime DSM-IV criteria was asked at follow up interviews. During the screening phase, mothers were administered a telephone questionnaire containing criteria for DSM-IIIR ADHD and exclusionary criteria for their referred child. Potential probands were excluded if they were adopted, if their nuclear family was not available for study or if they had major sensori-motor handicaps, psychosis, autism or a Full Scale IQ less than 70. Individuals who screened positive for DSM-IIIR ADHD were invited to enroll in the study along with their first-degree relatives. Referrals with subthreshold ADHD diagnoses were excluded. Study procedures were reviewed with all subjects, and participants were informed that they could withdraw at any time. Individuals 18 years of age or older provided written informed consent for themselves. Mothers provided written informed consent for minor children, and children provided written assent. Those classified as having ADHD at both the screen and the interview (described below) were included as index cases.

Additional sibling pairs with ADHD were ascertained from a family study of adults with ADHD (Faraone and others 2006a; Faraone and others 2006b), an affected sibling pair linkage study of ADHD and family studies of bipolar disorder. The screening methods for these studies were similar to the methods for the family studies of ADHD boys and girls with the following exceptions: 1) ADHD cases were only obtained from the psychiatry clinics at MGH (and for the linkage study, the child psychiatry clinic at Children’s Hospital in Boston) as well as advertisements and referrals from individual child psychiatrists in the community; 2) ascertainment was based on DSM-IV diagnoses; 3) the pediatric bipolar studies screened cases for bipolar disorder and did not use psychosis as a rule-out. For subjects coming from these studies, affection status was based on DSM-IV criteria for ADHD.

The final data set used in this study consisted of 474 ADHD affected offspring. Of those, 266 were probands and the remaining 208 were siblings who had ADHD. DNA was available for both parents in all families (100%). The age for the ADHD patients at the time of assessment ranged from 2 to 39 years. 361 patients were children and 83 patients were adults at the time of assessment. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Number of patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 308 (65) |

| Female | 166 (35) |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 458 (97) |

| Others | 16 (3) |

|

| |

| ADHD subtype* | |

| Combined | 288 (61) |

| Inattentive | 137 (30) |

| Hyperactive/Impulsive | 28 (6) |

|

| |

| Lifetime co-morbidity | |

| Oppositional Defiant | 254 (54) |

| Disorder | 114 (24) |

| Conduct Disorder | 109 (23) |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 131 (28) |

| Bipolar Disorder | 81 (17) |

| Substance Abuse Disorder | |

|

| |

| Total | 474 (100) |

|

| |

subtype classification missing for 21 affected offspring

Psychiatric Interviews

Diagnoses of probands and siblings 12 years of age and older were obtained from independent interviews with them and their mothers using the Schedule for Affective Disorders – Epidemiologic Version for children (Kiddie SADS-E); (Orvaschel and Puig-Antich 1987) which, for all studies except the family studies of girls and boys with ADHD, was adapted to include DSM-IV criteria. For children younger than 12, diagnostic information on these subjects came from parent interviews only. Interviewers were unaware of the proband’s diagnosis. Diagnostic assessments of parents and siblings older than 18 years were based on direct interviews using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM III-R (SCID; (Spitzer and others 1990) also adapted to include DSM-IV criteria in the relevant studies. Interviewers had undergraduate degrees in psychology and were trained to high levels of inter-rater reliability.

Diagnoses were scored as positive if all DSM criteria were unequivocally met, with a subthreshold diagnosis assigned to individuals meeting over two thirds of the symptoms of the condition (i.e. ≥ 6 DSM-IIIR symptoms or ≥4 DSM-IV symptoms of either inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity and cross-situationality) and at least a moderate level of impairment. For children older than 12, diagnoses were based on combined data from child and parent interviews, by considering a diagnosis positive if criteria were met in either interview. Diagnostic uncertainties were resolved by a committee of board-certified child psychiatrists and psychologists who were unaware of the subject’s ascertainment group and all data collected from family members.

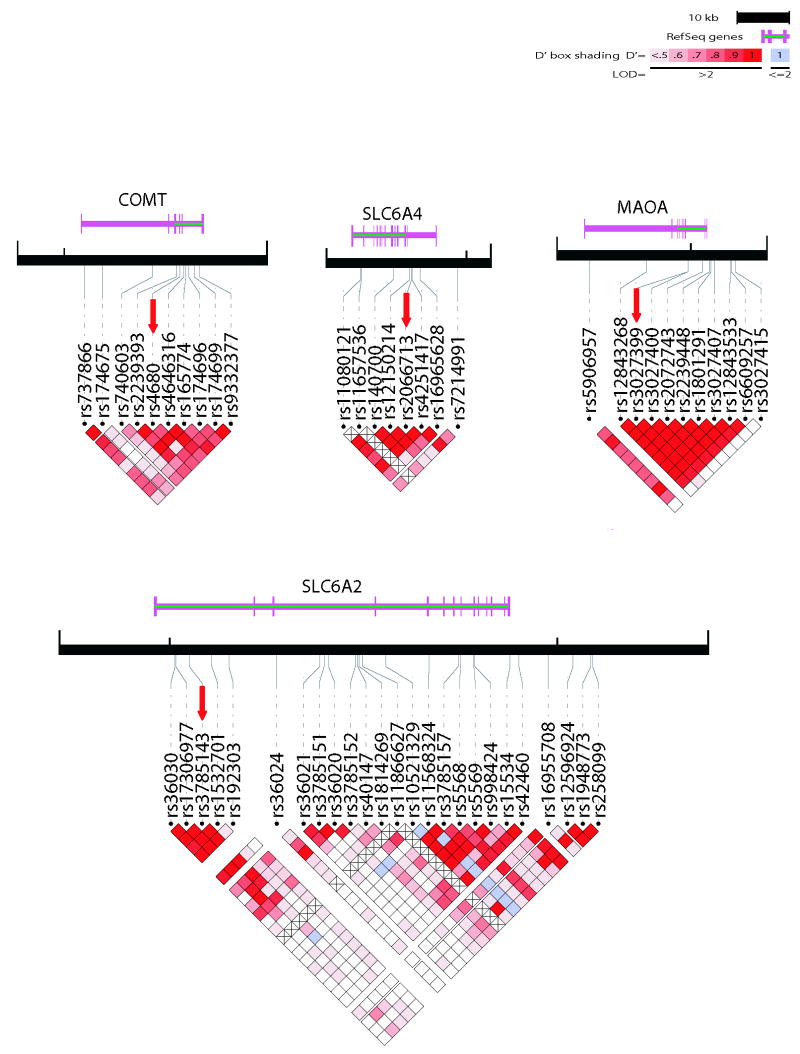

Selection of Genetic Markers

We genotyped tag SNPs which covers most of the common SNPs (minimum r2 >0.8) across COMT (10 SNPs), SLC6A2 (24 SNPs), MAOA (11 SNPs) and SLC6A4 (7 SNPs) genes as described previously (Kim and others 2007). However, for our analysis, we chose only one SNP per gene in order to avoid the burden of multiple testing. We chose the SNP with the lowest p-value for each gene (Figure 1) and tested them for gender effects in the full sample. After this analysis, we performed a post-hoc exploratory analysis for all of the tag SNPs in each gene to see if other loci produced stronger association signals.

Figure 1.

Genotyping

The genotyping for SNPs was performed using a multiple base extension reaction with allele discrimination by MassArray mass spectrometry system (Bruker-Sequenom) as previously described (Sklar and others 2002). A number of quality control measures were implemented to ensure the accuracy of the data collected. Genotypes from intra- and inter-plate controls were compared for accuracy, and negative test controls were confirmed to have no genotypes called. In addition, assays that failed in over 10% of the samples were excluded and samples that failed in over 10% of the assays were excluded. SNPs with a Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium p-value less than 0.001 were excluded from analysis. Families with Mendel error rates greater than 5% and SNPs with Mendel error rates greater than 1% were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

The pedigree data were screened for genotype inconsistencies by using PLINK (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/) (Purcell and others In press). PLINK was also used to assess genotype distributions for departures from Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium. The TDTPHASE program of the UNPHASED set (Dudbridge 2003) was used for TDT analysis of transmission to each sex. We also tested whether there was a statistically significant difference between the transmissions to males vs. transmissions to females (gender effect) for each gene using a standard chi-square test with 1 degree of freedom.

To examine the overall effect of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism in two independent samples including our families and another case-control study (Qian and others 2003), we converted each chi-square value to z scores, using the formula (χ2-n)/√ 2n, where n is the degrees of freedom for the chi square value. The combined z score was obtained using the inverse normal method by adding the two z scores and then dividing the sum by √2 (Hedges and Olkin 1985).

Results

The most significant SNPs for each gene as a result of the TDT analysis in the full sample are shown in Table 2. SNPs rs4680 (val158met) from COMT and rs3785143 from SLC6A2 showed nominally significant (p<0.05) association, while the other two SNPs (rs3027399 from MAOA and rs2066713 from SLC6A4) were not significant. As we have reported previously (Kim and others 2007), the association of rs3785143 with ADHD is a direct replication of a previous finding (Brookes and others 2006). In gender-stratified analyses of COMT, we observed over-transmission of the Met (A) allele to male offspring (OR=1.42, 95% CI= 1.12-1.81; p=0.003) but not to female offspring (p=0.936) (Table 2). This replicates a previous finding which reported significant association of the Met (A) allele of Val158Met in males with ADHD (Qian and others 2003).

Table2.

Sex specific association of four ADHD genes

| Gene | Marker | ALL | Transmission to male offspring | Transmission to female offspring | * Males vs.Females | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | P value | Allele | T/NT | P | Allele | T/NT | P | χ2 | P | ||

| COMT | rs4680 | A | 0.023 | A | 162/114 | 0.003 | A | 77/78 | 0.936 | 3.27 | 0.071 |

| SLC6A2 | rs3785143 | T | 0.020 | T | 55/46 | 0.370 | T | 38/18 | 0.006 | 2.68 | 0.101 |

| MAOA | rs3027399 | C | 0.093 | C | 22/20 | 0.757 | C | 20/8 | 0.021 | 2.54 | 0.111 |

| SLC6A4 | rs2066713 | T | 0.254 | T | 152/128 | 0.151 | T | 74/74 | 1.000 | 0.71 | 0.398 |

test of male vs. female transmissions

For SLC6A2, we found that the T allele of rs3785143 displayed a stronger effect in females (OR=2.11, 95% CI= 1.20 -3.69; p=0.006) than in males (p=0.370) (Table 2). For MAOA, the SNP associating to ADHD in the full sample (rs3027399; p=0.093) showed a nominally significant effect for females (OR=2.5, 95% CI=1.10-5.67; p=0.02) but not for males (p=0.757) (Table 2). Finally, we observed no evidence of association between the SLC6A4 SNP rs2066713 with ADHD, either in the full sample or when stratified by gender.

Despite the apparent gender differences from the stratified analyses, our formal test of gender differences did not detect a significant gender effect across the four genes (P>0.05 for each polymorphism) (Table 2.). However, when we combined our COMT (Val158Met) data with data from another study which investigated the sex effect of Val158Met (Qian et al 2003), the pooled result showed a statistically significant gender effect for Val158Met in ADHD (z=2.69, p=0.007) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pooled analysis of Met allele of Val158Met (COMT) from two independent studies

| TDT (our data)† | Case-control (Qian et al 2003) | Combined result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male ADHD | T/NT = 162/114 | Met/Val = 170/376 | -- |

| Female ADHD | T/NT =77/78 | Met/Val = 18/70 | -- |

| Males vs. Females | χ2=3.27, P=0.071 | X2=4.145, P=0.042 | Z= 2.69, P=0.007 |

T/NT = transmission/nontransmission of Met allele

Both studies report significant association of Met allele with male ADHD.

We also performed an exploratory analysis by looking at every SNP marker of each gene to see whether we missed any SNP that may have shown a gender specific effect. As a consequence, we have discovered a nominally significant effect (p<0.05) for COMT (rs2239393; p=0.054) and SLC6A2 (rs36020; p=0.014) (Table 4). However, these results did not survive correction for multiple testing by Bonferroni’s method.

Table 4.

Exploratory analysis of gender effect across each gene

| Gene | Allele | Male | Female | χ2 | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMT | T | NT | T | NT | |||

| rs737866 | C | 114 | 133 | 65 | 50 | 3.37 | 0.066 |

| rs174675 | C | 111 | 116 | 70 | 59 | 0.94 | 0.330 |

| rs740603 | A | 156 | 135 | 71 | 80 | 1.72 | 0.188 |

| rs2239393 | A | 160 | 114 | 58 | 63 | 3.71 | 0.054 |

| rs4680 | A | 162 | 114 | 77 | 78 | 3.26 | 0.071 |

| rs4646316 | C | 155 | 112 | 51 | 50 | 1.69 | 0.192 |

| rs165774 | A | 124 | 97 | 76 | 72 | 0.81 | 0.368 |

| rs174696 | C | 107 | 98 | 43 | 56 | 2.05 | 0.152 |

| rs174699 | C | 31 | 28 | 11 | 17 | 1.33 | 0.247 |

| rs9332377 | C | 85 | 83 | 46 | 42 | 0.06 | 0.798 |

|

| |||||||

| MAOA | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| rs5906957 | A | 49 | 56 | 26 | 30 | 0.001 | 0.977 |

| rs12843268 | A | 60 | 61 | 27 | 34 | 0.46 | 0.497 |

| rs3027399 | C | 22 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 2.54 | 0.111 |

| rs3027400 | G | 60 | 58 | 36 | 27 | 0.65 | 0.418 |

| rs2072743 | C | 65 | 65 | 40 | 28 | 1.39 | 0.237 |

| rs2239448 | C | 60 | 58 | 35 | 27 | 0.51 | 0.474 |

| rs1801291 | C | 57 | 58 | 35 | 27 | 0.76 | 0.381 |

| rs3027407 | A | 58 | 60 | 27 | 36 | 0.65 | 0.418 |

| rs12843533 | C | 19 | 21 | 10 | 9 | 0.13 | 0.712 |

| rs6609257 | A | 74 | 74 | 40 | 34 | 0.32 | 0.568 |

| rs3027415 | C | 50 | 51 | 28 | 25 | 0.15 | 0.695 |

|

| |||||||

| NET | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| rs36030 | C | 69 | 70 | 35 | 45 | 0.71 | 0.401 |

| rs17306977 | A | 59 | 77 | 37 | 32 | 1.92 | 0.165 |

| rs3785143 | T | 55 | 46 | 38 | 18 | 2.68 | 0.101 |

| rs1532701 | A | 165 | 153 | 69 | 83 | 1.73 | 0.187 |

| rs192303 | C | 133 | 130 | 78 | 62 | 0.96 | 0.324 |

| rs36024 | A | 141 | 139 | 69 | 62 | 0.19 | 0.661 |

| rs36021 | A | 136 | 131 | 60 | 67 | 0.46 | 0.493 |

| rs3785151 | C | 73 | 84 | 32 | 32 | 0.22 | 0.636 |

| rs36020 | C | 55 | 75 | 45 | 30 | 5.95 | 0.014 |

| rs3785152 | C | 60 | 39 | 28 | 25 | 0.85 | 0.354 |

| rs40147 | A | 113 | 138 | 60 | 57 | 1.25 | 0.262 |

| rs1814269 | A | 136 | 152 | 81 | 65 | 2.64 | 0.104 |

| rs10521329 | A | 99 | 98 | 48 | 55 | 0.36 | 0.548 |

| rs11568324 | C | 9 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.824 |

| rs3785157 | C | 135 | 155 | 64 | 69 | 0.09 | 0.764 |

| rs5568 | A | 132 | 120 | 64 | 80 | 2.31 | 0.128 |

| rs5569 | A | 121 | 104 | 49 | 59 | 2.06 | 0.151 |

| rs998424 | A | 154 | 135 | 68 | 67 | 0.31 | 0.575 |

| rs15534 | C | 91 | 95 | 51 | 36 | 2.23 | 0.135 |

| rs42460 | A | 46 | 40 | 28 | 23 | 0.02 | 0.872 |

| rs16955708 | C | 88 | 87 | 44 | 38 | 0.25 | 0.614 |

| rs12596924 | G | 93 | 92 | 52 | 55 | 0.07 | 0.783 |

| rs1948773 | A | 54 | 54 | 31 | 25 | 0.42 | 0.515 |

| rs258099 | C | 118 | 120 | 66 | 74 | 0.21 | 0.647 |

|

| |||||||

| SERT | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| rs11080121 | A | 155 | 147 | 73 | 71 | 0.02 | 0.901 |

| rs140700 | A | 52 | 55 | 20 | 19 | 0.08 | 0.774 |

| rs12150214 | C | 94 | 84 | 42 | 42 | 0.18 | 0.671 |

| rs2066713 | T | 152 | 128 | 74 | 74 | 0.71 | 0.398 |

| rs4251417 | A | 56 | 54 | 32 | 32 | 0.01 | 0.907 |

| rs16965628 | C | 39 | 36 | 22 | 17 | 0.2 | 0.654 |

| rs7214991 | C | 157 | 133 | 69 | 82 | 2.83 | 0.092 |

Discussion

By stratifying by sex, we observed modest evidence of association between ADHD and variants in three genes that was not evident in our full family-based sample. The effect sizes are modest (OR=1.2~2.5) as expected for a complex genetic disorder, and a formal test of gender differences was not significant. Nevertheless, when we pooled our COMT data with a prior report we did find a significant gender differences for the Val158Met allele.

Although our exploratory analysis (Table 4) found gender specific effect for two SNPs, there are some limitations. First, although two SNPs (rs2239393, rs36020) showed nominally significant (p<0.05) gender effects, it did not remain significant after correction for multiple testing . Second, rs2239393 (COMT) is in high LD (D’=0.99; r2=0.73) with rs4680 and thus highly correlated to the rs4680 association. It is also an intronic SNP with no known functional effects and it may be unlikely that it will have any causative effect. Third, while rs36020 (SLC6A2) showed a gender specific effect in the chi-square test, stratified results for each sex were not significant (Table 4). This happened since the involved allele merely ran in opposite directions in each group. Since there is no effect for either males or females, this is a false-positive finding.

We observed association of the Met (A) allele of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism in males (OR=1.42, 95% CI= 1.12-1.81; p=0.003) but not females (p=0.936) with ADHD, replicating the findings of Qian et al. (2003), however, because this latter study was a case-control study, its results could have been an artifact of population stratification. Evidence from previous genetic and biological studies also indicates that the Met allele plays a deleterious role specifically in males. It has been consistently reported to be associated with aggressive and impulsive behavior in males (Gogos 1998; Strous 1997; Lachman 1998; Kotler 1999; Strous 2003). Similarly, COMT deficient mice show elevated aggressive behavior in males only (Gogos and others 1998). This is in concert with a report that ADHD boys display more hyperactive/impulsive behaviors and other externalizing behaviors such as conduct problems than do girls with ADHD (Abikoff and others 2002; Biederman and others 2002; Gaub and Carlson 1997b). One recent meta-analytic study (Pooley and others 2007) found that the Met allele of COMT was significantly associated with obsessive compulsive disorder for males only. The effects of the Val158Met polymorphism on brain dopaminergic (DA) transmission are complex (Bilder and others 2004). The Met allele is associated with decreased synaptic DA transmission subcortically and increased DA concentrations cortically. The Val allele is associated with increased synaptic DA transmissions subcortically and decreased DA concentrations cortically. Despite this prior evidence for a stronger association of COMT for males, if COMT is associated with ADHD, meta-analyses of prior work (which used primarily male samples) should have found a significant effect but did not (Cheuk and Wong 2006).

We also observed gender-based differences in association with a SNP in SLC6A2. Specifically, the T allele of rs3785143 displayed association with ADHD for females (OR=2.11, 95% CI= 1.20 -3.69; p=0.006) but not for males (p=0.370). SNP rs3785143 is located in intron 1, a region reported to be responsible for high-level transcription of SLC6A2. Previous findings from animal studies suggest that dysfunction of the SLC6A2 gene may be more harmful to females that males (Curtis and others 2006; Keller and others 2006). A recent study compared the activation of the locus coeruleus (LC)-norepinephrine (NE) system in response to stress between female and male rats (Curtis and others 2006). The mean basal LC discharge rate was similar between groups. However, the magnitude of LC activation elicited by hypotensive stress was substantially greater in females, regardless of hormonal status. The difference in stress sensitivity could be attributed to the differential postsynaptic sensitivity of LC neurons to corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), which mediates LC activation by hypotension. CRF was 10-30 times more potent in activating LC neurons in female vs male rats. In mice lacking the norepinephrine transporter (SLC6A2) gene, females appear to be significantly more vulnerable to anxiogenic challenges than male mice in several measures of fear and anxiety (Keller and others 2006).

With respect to MAOA, we also observed nominal evidence of association of rs3027399 in females only (OR=2.5, 95% CI=1.10-5.67; p=0.02). This SNP is an intronic SNP which has no evidence of any functional effect currently but it is possible that this SNP may be in LD with a nearby functional variant. Our study is not the first to report a stronger association for female ADHD with MAOA. Manor et al (2002) previously reported an association for MAOA in females with ADHD (Manor and others 2002). They investigated a 30 bp VNTR located 1.2kb upstream in the promoter region of the MAOA gene which is reported to be associated with transcriptional efficiency (Sabol and others 1998). Data from the International HapMap Project (CEU; release 22) indicate that the entire MAOA gene region (including the 10kb upstream promoter region) is actually one large haplotype block using the most conservative block defining method (Gabriel and others 2002). Thus, while we did not genotype the promoter VNTR, it is likely to be that rs3027399 is in LD with it. Results from these two ADHD genetic studies show that MAOA association may be female specific for ADHD.

Our results should be evaluated in the context of several limitations. Our significant gender effect for COMT obtained by combining two disparate samples could be a false positive result and the finding from the case-control study could be due to population stratification. All of our results are vulnerable to the possibility of Type 1 errors because no correction for multiple testing was made. If the effects we observed are real, they are very small, which highlights the difficulty of finding a suitable replication sample and questions the value of the result in explaining much of the genetic diathesis of ADHD.

Despite these limitations, by stratifying by offspring sex, we observed modest evidence of gender effects of COMT, SLC6A2 and MAOA with ADHD. The findings of our study need to be replicated in other independent samples for corroboration. Our results suggest that future studies of genes with biological evidence of sexually dimorphic effects should examine gender-specific effects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01HD37694, R01HD37999 and R01MH66877 to S. Faraone and NARSAD Young Investigator Award to JWK. JWK is a NARSAD Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation Investigator. The authors thank Dr. Pamela Sklar and her laboratory for completing the genotyping for this project.

References

- Abikoff H, Jensen P, Arnold LE, Hoza B, Hechtman L, Pollack S, Martin D, Alvir J, March JS, Hinshaw SP, et al. Observed classroom behavior of children with ADHD: Relationship to gender and comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30(4):349–359. doi: 10.1023/a:1015713807297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold L. Sex differences in ADHD: Conference summary. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24(5):555–569. doi: 10.1007/BF01670100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry CA, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. Girls with attention deficit disorder: A silent minority? A report on behavioral and cognitive characteristics. Pediatrics. 1985;76(5):801–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia M, Nigam V, Bohra N, Malik S. Attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity among pediatric outpatients. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1991;32(2):297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, Benjamin J, Krifcher B, Moore C, Sprich-Buckminster S, Ugaglia K, Jellinek MS, Steingard R, et al. Further evidence for family-genetic risk factors in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Patterns of comorbidity in probands and relatives in psychiatrically and pediatrically referred samples. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49(9):728–38. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090056010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Mick E, Williamson S, Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Weber W, Jetton J, Kraus I, Pert J, et al. Clinical correlates of ADHD in females: findings from a large group of girls ascertained from pediatric and psychiatric referral sources. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(8):966–975. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Monuteaux MC, Spencer T, Wilens T, Bober M, Cadogan E. Gender effects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults, revisited. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55(7):692–700. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, Braaten E, Doyle AE, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Frazier E, Johnson MA. Influence of gender on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children referred to a psychiatric clinic. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(1):36–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder RM, Volavka J, Lachman HM, Grace AA. The catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism: relations to the tonic-phasic dopamine hypothesis and neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(11):1943–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen MJ, Altepeter TS. Situational variability in boys and girls identified as ADHD. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1990;46(4):486–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes K, Xu X, Chen W, Zhou K, Neale B, Lowe N, Aneey R, Franke B, Gill M, Ebstein R, et al. The analysis of 51 genes in DSM-IV combined type attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: association signals in DRD4, DAT1 and 16 other genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cases O, Seif I, Grimsby J, Gaspar P, Chen K, Pournin S, Muller U, Aguet M, Babinet C, Shih JC, et al. Aggressive behavior and altered amounts of brain serotonin and norepinephrine in mice lacking MAOA. Science. 1995;268(5218):1763–6. doi: 10.1126/science.7792602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Giedd JN, Berquin PC, Walter JM, Sharp W, Tran T, Vaituzis AC, Blumenthal JD, Nelson J, Bastain TM, et al. Quantitative brain magnetic resonance imaging in girls with attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(3):289–95. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheuk DK, Wong V. Meta-analysis of Association Between a Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Gene Polymorphism and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Behav Genet. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Bethea T, Valentino RJ. Sexually dimorphic responses of the brain norepinephrine system to stress and corticotropin-releasing factor. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(3):544–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckert J, Catalano M, Syagailo YV, Bosi M, Okladnova O, Di Bella D, Nothen MM, Maffei P, Franke P, Fritze J, et al. Excess of high activity monoamine oxidase A gene promoter alleles in female patients with panic disorder. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(4):621–4. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudbridge F. Pedigree disequilibrium tests for multilocus haplotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;25(2):115–21. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiraldi R, Power T, Nezu C. Patterns of comorbidity associated with subtypes of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among 6 to 12 year old children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(3):503–514. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone S, Biederman J, Webber W, Russell R. Psychiatric, neuropsychological, and psychosocial features of DSM-IV subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Results from a clinically referred sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):185–193. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199802000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: Implications for theories of diagnosis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9(1):33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Doyle AE, Murray K, Petty C, Adamson J, Seidman L. Neuropsychological Studies of Late Onset and Subthreshold Diagnoses of Adult ADHD. Biological Psychiatry. 2006a;60(10):1081–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Keenan K, Tsuang MT. A family-genetic study of girls with DSM-III attention deficit disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148(1):112–117. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E, Williamson S, Wilens T, Spencer T, Weber W, Jetton J, Kraus I, Pert J, et al. Family study of girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000a;157(7):1077–83. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer T, Wilens T, Seidman LJ, Mick E, Doyle AE. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: an overview. Biological Psychiatry. 2000b;48(1):9–20. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00889-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Mick E, Murray K, Petty C, Adamson JJ, Monuteaux MC. Diagnosing Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Are Late Onset and Subthreshold Diagnoses Valid? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006b;163(10):1720–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Goralnick J, Holmgren MA, Sklar P. Molecular genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, Higgins J, DeFelice M, Lochner A, Faggart M, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296(5576):2225–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaub M, Carlson C. Behavioral characteristics of DSM-IV ADHD subtypes in a school-based population. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997a;25(2):103–111. doi: 10.1023/a:1025775311259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaub M, Carlson CL. Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997b;36(8):1036–1045. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199708000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjone H, Stevenson J, Sundet J. Genetic influence on attention problems in a general population twin sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;45:588–596. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199605000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogos JA, Morgan M, Luine V, Santha M, Ogawa S, Pfaff D, Karayiorgou M. Catechol-O-methyltransferase-deficient mice exhibit sexually dimorphic changes in catecholamine levels and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(17):9991–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Stevenson J. A twin study of hyperactivity: I. An examination of hyperactivity scores and categories derived from Rutter teacher and parent questionnaires. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1989;30(5):671–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes AP, Zeni C, Polanczyk GV, Genro JP, Roman T, Rohde LA, Hutz MH. Serotonin genes and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a Brazilian sample: Preferential transmission of the HTR2A 452His allele to affected boys. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144(1):69–73. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic Press; 1985. p. 369. ill. ; 24 cm. p. [Google Scholar]

- Herman AI, Kaiss KM, Ma R, Philbeck JW, Hasan A, Dasti H, DePetrillo PB. Serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism and monoamine oxidase type A VNTR allelic variants together influence alcohol binge drinking risk in young women. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;133(1):74–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. Preadolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Background characteristics, comorbidity, cognitive, and social functioning, and parenting practices. J Consult Clin Psych. 2002;70(5):1086–1098. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn W, Wagner A, Ialongo N. Sex differences in school-aged children with pervasive attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1989;17(1):109–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00910773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James A, Taylor E. Sex differences in the hyperkinetic syndrome of childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1990;31(3):437–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashani J, Chapel J, Ellis J, Shekim W. Hyperactive girls. Journal of Operational Psychiatry. 1979;10(2):145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Keller NR, Diedrich A, Appalsamy M, Miller LC, Caron MG, McDonald MP, Shelton RC, Blakely RD, Robertson D. Norepinephrine transporter-deficient mice respond to anxiety producing and fearful environments with bradycardia and hypotension. Neuroscience. 2006;139(3):931–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DK, Tolliver TJ, Huang SJ, Martin BJ, Andrews AM, Wichems C, Holmes A, Lesch KP, Murphy DL. Altered serotonin synthesis, turnover and dynamic regulation in multiple brain regions of mice lacking the serotonin transporter. Neuropharmacology. 2005a;49(6):798–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Waldman ID, Faraone SV, Biederman J, Doyle AE, Purcell S, Arbeitman L, Fagerness J, Sklar P, Smoller JW. Investigation of parent-of-origin effects in ADHD candidate genes. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Badner J, Cheon KA, Kim BN, Yoo HJ, Cook E, Jr, Leventhal BL, Kim YS. Family-based association study of the serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms in Korean ADHD trios. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005b;139(1):14–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman HM, Morrow B, Shprintzen R, Veit S, Parsia SS, Faedda G, Goldberg R, Kucherlapati R, Papolos DF. Association of codon 108/158 catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism with the psychiatric manifestations of velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1996;67(5):468–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960920)67:5<468::AID-AJMG5>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manor I, Tyano S, Mel E, Eisenberg J, Bachner-Melman R, Kotler M, Ebstein RP. Family-based and association studies of monoamine oxidase A and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): preferential transmission of the long promoter-region repeat and its association with impaired performance on a continuous performance test (TOVA) Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7(6):626–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children: Epidemiologic Version. Fort Lauderdale, FL: Nova University; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Pauls DL, Shaywitz SE, Kramer PL, Shaywitz BA, Cohen DJ. Demonstration of vertical transmission of attention deficit disorder. Annals of Neurology. 1983;14:363. [Google Scholar]

- Pooley EC, Fineberg N, Harrison PJ. The met(158) allele of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder in men: case-control study and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(6):556–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira M, Bender D, Maller J, de Bakker P, Daly M, Sham P. PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. American Journal of Human Genetics. doi: 10.1086/519795. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Q, Wang Y, Zhou R, Li G, Wang B, Glatt S, Faraone SV. Family-based and case-control association studies of catechol-O-methyltransferase in attention deficit hyeractivity disorder suggest genetic sexual dimorphism. Am J Med Genet. 2003;118B(1):103–109. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Waldman ID, Hay DA, Levy F. Sex differences in genetic and environmental influences on DSM-III-R attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108(1):24–41. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabol SZ, Hu S, Hamer D. A functional polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase A gene promoter. Hum Genet. 1998;103(3):273–9. doi: 10.1007/s004390050816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman L, Biederman J, Monuteaux M, Valera E, Doyle AE, Faraone S. Impact of Gender and age on Executive Functioning: Do Girls and Boys with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder differ neuropsychologically in pre-teen and teenage years? Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005a;27(1):79–105. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2701_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ. Neuropsychological functioning in people with ADHD across the lifespan. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(4):466–485. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ, Biederman J, Valera EM, Monuteaux MC, Doyle AE, Faraone SV. Neuropsychological functioning in girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with and without learning disabilities. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(2):166–77. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Makris N. Structural Brain Imaging of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005b;57(11):1263–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg J, Rutter M, Meyer J, Maes H, Hewitt J, Simonoff E, Pickles A, Loeber R. Genetic and environmental influences on the covariation between hyperactivity and conduct disturbance in juvenile twins. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1996;37(7):803–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar P, Gabriel SB, McInnis MG, Bennett P, Lim YM, Tsan G, Schaffner S, Kirov G, Jones I, Owen M, et al. Family-based association study of 76 candidate genes in bipolar disorder: BDNF is a potential risk locus. Brain-derived neutrophic factor. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7(6):579–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuse DH. Sexual dimorphism in cognition and behaviour: the role of X-linked genes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155(Suppl 1):S99–S106. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R: Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP, Version 1.0) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Staley JK, Sanacora G, Tamagnan G, Maciejewski PK, Malison RT, Berman RM, Vythilingam M, Kugaya A, Baldwin RM, Seibyl JP, et al. Sex differences in diencephalon serotonin transporter availability in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(1):40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari P. The epidemiology of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1982;1(2):361–371. [Google Scholar]

- Valera EM, Faraone SV, Murray KE, Seidman LJ. Meta-analysis of structural imaging findings in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(12):1361–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss LA, Abney M, Cook EH, Jr, Ober C. Sex-specific genetic architecture of whole blood serotonin levels. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76(1):33–41. doi: 10.1086/426697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]