Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent form of arthritis and is among the most prevalent chronic conditions in the United States. Because there is no known cure for OA, treatment is directed towards the alleviation of pain, improving function, and limiting disability. The major burden of care falls on the individual, who tailors personal systems of care to alleviate troublesome symptoms. To date, little has been known about the temporal variations in self-care that older patients with OA develop, nor has it been known to what extent self-care patterns vary with ethnicity and disease severity. This study was designed to demonstrate the self-care strategies used by older African Americans and whites to alleviate the symptoms of OA on a typical day and during specific segments of a typical day over the past 30 days. A sample of 551 older adults participated in in-depth interviews, and the authors clustered their responses into six categories. Findings showed that the frequency of particular behaviors varied by time of day, disease severity, and race. Overall, patterns of self-care behaviors were similar between African-Americans and whites, but African-Americans used them in different proportions than whites and in response to disease severity. Knowledge of what strategies persons with OA use to lessen their symptoms at various times of the day may enable practitioners and their patients to improve management of OA symptoms. Recognition that people may choose their strategies to ameliorate their symptoms by race and disease severity may further enable tailored symptom relief.

Keywords: African-Americans, osteoarthritis, self-care, chronic disease

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent form of arthritis and is among the most prevalent chronic conditions in the U.S. (Lawrence, 1998). Because there is no known cure for OA, treatment is directed primarily to alleviating pain, improving function, and limiting disability (Altman et al., 2000 & 1986). Therefore, the major burden of care falls on the individual, who tailors his or her own personal systems of care to alleviate troublesome symptoms and promote independent functioning.

Researchers have recognized the patients’ responsibility for self-care (DeFriese et al., 1994; Dill et al., 1995; Lorig 2000, and others). Over the past 30 years, they have described the types of self-care behaviors used by chronically ill older adults to manage such illnesses as stroke (Becker et al., 1995), cancer (Charmaz, 1991), heart disease (Schoenberg, 2005), diabetes (Reid, 1992, Schoenberg et al., 2001), and other musculoskeletal and related illnesses (Arcury et al., 1996; Verbrugge & Ascione, 1987). Not only do these behaviors vary by the nature of the disease, they also vary in their expression and selection by gender (Dean, 1989b), race or ethnicity (Becker et al., 2004; Boyd et al., 2000; Davis & McGadney, 1994; Ibrahim et al., 2001), severity of the illness (Verbrugge & Ascione, 1987), and, as the case of Ms. W. illustrates, by time of day.

Ms. W. is a 68-year-old African-American woman who has had arthritis in her knee for 20 years. She describes her arthritis pain as “... sort of like aching, nagging type of pain, like a toothache....it's an all day thing.” To cope with the symptoms, she has developed several self-care strategies that she uses depending on the time of day. When she first gets up in the morning, “I sit on the end (of the bed). I like stretching; I do an exercise learned at therapy...I rub, I like to massage myself.” To make herself feel better throughout the day, she reports that, “most of the time, I will come home and relax, lay down ... put some heat on it.” If it (the pain) gets too bad, “I will call my doctor, or take baths.” At night, she uses other strategies to enable to her to feel comfortable. “Sometimes, I prop my knees with pillows... [use] heat, or I will take my medicine, or use Epson salts or grain alcohol.” (All quotations from respondents taken from interviewer field notes and tape transcripts.)

As Mrs. W. illustrates, self-care behaviors do not occur in isolation from other treatments but may complement and sometimes substitute for formal medical care. People with musculoskeletal illnesses such as osteoarthritis may substitute medications and other therapies for professional medical treatment (Verbrugge & Ascione, 1987).

There is no shortage of self-care definitions and concepts (Becker et al., 2004). The definition for self-care (or self-management as it is also called) used in this study is, “the range of health and illness behavior undertaken by individuals on behalf of their own health” (Dean, 1992a, p. 34).

Keysor et al., (2001) indicate, “The long nature of chronic disease gives the individual a crucial role, if not the most crucial role, in managing their condition” (p.89). Sobel (1995) suggests that “self-care is the ‘hidden’ healthcare system and that self care, rather than primary, secondary, or tertiary care, comprises the majority of health care” (Sobel, 1995, quoted in Keysor, 2003 p. 724). Researchers also stress that management of chronic problems (in contrast to acute problems) is a process that leads individuals to craft strategies of care over months and years and then apply them when problems flare up (Verbugge & Ascione, 1987).

While studies of self-care or self-management of chronic illness among older adults are plentiful, several obstacles prevent generalizing the findings. In a critical review and a meta-analysis of studies of self-management of arthritis, (Keysor et al., 2003) indicate that one of the major problems with research on self-care is that the data are collected using a variety of different categorizations (categorical response lists versus qualitative subjective interviews, for example) or conceptual models (broad versus narrow frameworks), making comparisons of the findings problematic. For example, Albert et al., (2008 in press) question including doctor-prescribed actions with actions that the patient develops in describing self-management for OA. There is little agreement about which self-care behaviors should be labeled complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) versus other types of self-management such as massage, prayer, or dietary supplements (Arcury et al., 2007). Another unresolved issue is the optimum method for retrieving information about what people do to self-manage their chronic illnesses (Becker et al., 2004; Verbrugge & Ascione, 1987; Ruggieri, 2003; Stoller et al., 1993a & 1993b). Finally, the literature has not yet fully described how self-care behaviors vary by gender (Arcury, 1996), race (Silverman et al., 1999; Reid; 1992, Davis & Wykle, 1998), and disease severity (Verbrugge & Ascione, 1987).

We developed this paper to attempt to address some of the unanswered questions about self-care among older adults with OA. It describes the overall self-care interview responses of a population-based cohort of older adults who reported diagnoses of hip or knee OA and were experiencing some problems with these illnesses. The paper has three aims:

Using a patient-centered approach and a temporal framework, to describe and compare the self-care behaviors used to alleviate symptoms of osteoarthritis over the entire day and at three different time segments of a typical day over the past 30 days

To compare those behaviors to actions taken to relieve worsening symptoms

To examine the similarities and differences in these self-care behaviors by disease severity, race, and other relevant socio-demographic factors

This study offers several advantages over other self-care research. First, it allows the respondent (rather than the researcher) to define the relevant self-care behaviors. Second, it illustrates the variations in how individuals care for their chronic illness by time of day, by changes in symptom type and severity, and by differences in race. The information on illness management that we derive offers benefits to older adults and their practitioners, who may then be better able to tailor their treatment recommendations to specific problems and to the individuals’ daily needs.

Sample

The 551 participants in this study were enrolled in a National Institute on Aging Study (AGO18308). The eligible group were community-dwelling adults aged 65 and over who resided in Allegheny County, PA; who met the screening criteria for knee or hip osteoarthritis; and who had no obvious indication of cognitive impairment. Screening was based on a series of self-report questions derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (Dillon et al., 2006). Respondents were required to report that they had (1) pain in their hip or knee on most days for at least a month, (2) pain when walking or standing for at least half the days during the preceding month, and (3) pain of this severity for a period of at least six months.

From June 2001 to May 2002, 5094 community-dwelling older adults in Allegheny County were surveyed by telephone regarding their eligibility for the larger study. The sample for the recruitment survey was randomly drawn from individuals aged 65 and over who were included in the Medicare Enrollment File for Allegheny County in April, 2001. The Medicare Enrollment File includes 96% or more of adults aged 65 or over nationally and, thus, is broadly representative of older adults. Fifty-two percent of eligible respondents agreed to participate (n=551).

People eligible to participate in the research were more likely to be African-American (57.3% of eligible participants, compared to 48.1% white, p < .001), younger (54.6% of participants were aged 65−74 and 48.6% of participants were older than 75, p < .01), and well educated (57.8% of participants attended college, p <.001). Because we aimed to recruit equal numbers of white and African-American elders with osteoarthritis, the sample is not representative of Medicare enrollees generally. For more detailed information on recruitment and sampling of this population, refer to Albert et al., 2008 (in press).

Study Design

The data for this paper are derived from a series of questions in the baseline interview, for which the respondents were interviewed in person in their homes, or at a mutally agreed upon place, and were asked to respond to a series of questions about their symptom management for their OA (hip or knee). Respondents were interviewed four times over 36 months. All the interviews were audiotaped with the permission of the respondents. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh's Institutional Review Board .

Following systematic questioning about the respondents’ health and assessment of the severity of their illnesses, interviewers asked the respondents to address the following question:

What did you do to care for your OA (hip or knee) on a typical day over the past 30 days?

This question was followed by questions framed to address specific segments of the day:

“What do you do when you first wake up in the morning to alleviate the symptoms of your OA?”

“What do you do throughout the day to alleviate the symptoms of your OA?”

“What do you do before you go to bed at night to manage the symptoms of your OA and enable you to sleep comfortably?”

In addition, participants were asked,

“What do you do when your pain gets worse to alleviate the symptoms of your OA?”

The interviewers, who were of mixed backgrounds, were trained to ask the questions in an open-ended, qualitative format, using prompts only to encourage continued response. They reported responses verbatim and as recorded from their notes and the audiotape recordings. These responses became the data base for coding and analysis of the respondents’ self-care behaviors. (Note: Where there was an absence of audiotape because of tape failure or interviewee refusal, the interviewers’ notes were the only source of information. The audiotapes were also used for back-up to clarify responses that were not clearly written or understandable).

The study investigators deliberately chose a qualitative inquiry as the initial technique in the baseline interview for gathering data on self-care behaviors to allow the respondents to use their own words to describe their strategies for symptom relief. The value of this type of inquiry is that it pre-empts structuring and perhaps limiting the responses as may happen when interviewers use a predetermined list of behaviors (Becker et al. 2004; Crabtree & Miller, 1992; Patton, 1990; Rubenstein, 1997; Strauss & Corbin, 1990) . It provides an opportunity for the respondents, rather than the researchers, to define self-care behaviors and strategies and provide explanations for why and how they may use those strategies.

After the identification of possible categories from the literature (Keysor et al., 2003; Ory & DeFriese, 1998), researchers designed the coding scheme for qualitiative responses to questions on self-care behaviors thoughout the entire baseline interview following an approach of coding responses at the lowest level into homogeneous clusters and assigning them to specific categories. For example, behaviors such as walking and doing stretches were given a similar code (as movement/physical). The coding was iterative in that as new codes were needed, additional subcodes were added, or, as new or more approriate categories were identified, the responses were recoded. Double coding by two researchers provided assurance of accuracy and agreement. The coders met with the investigators routinely to discuss coding issues such as which code to use in a particular situation or the need for additional codes.

The research team conducted a consensus review of these categories, which went through several revisions. For purposes of analysis and comparison, the multiple categories were condensed into six “collective” categories of self-care behaviors commonly reported by the respondents:

Medication (prescription or over-the-counter)

Topicals (salves, ointments, creams, hot/cold treatments, self-massage)

Movement (exercise or movement)

Activity limitation (restrain activity, rest)

Diet (dietary change, diet supplements, use of vitamins, minerals, herbals)

Alternative practices (such as miscellaneous home remedies, meditation, prayer/religion), (Table 1)

Table 1.

Use of Self-Care by Time of Day and Severity (Percent indicating use)

| Typical day | First get out of bed | Throughout the day | At night | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||||

| Prescription/OTC Medications | 60.1 | 18.0 | 36.3 | 29.8 | 81.9 |

| Topical Treatments | 33.9 | 24.9 | 20.1 | 19.6 | 57.9 |

| Movement, Exercise | 17.1 | 41.2 | 18.3 | 4.7 | 57.2 |

| Diet Supplements, Diet Change | 8.9 | 4.9 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 15.2 |

| Alternative Practices, Home remedies, meditation, prayer, religion | 5.3 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 6.4 | 24.0 |

| Activity limitation/rest | 15.2 | 20.0 | 32.3 | 33.4 | 66.4 |

| Low Severity | |||||

| Prescription/OTC Medications | 52.6 | 15.4 | 32.1 | 22.6 | 75.6 |

| Topical Treatments | 24.8 | 21.4 | 15.8 | 15.8 | 50.4 |

| Movement, Exercise | 15.4 | 40.2 | 19.2 | 1.7 | 58.5 |

| Diet Supplements, Diet Change | 9.8 | 5.6 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 17.1 |

| Alternative Practices, home remedies, meditation, prayer, religion | 3.8 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 5.6 | 21.8 |

| Activity limitation/rest | 13.7 | 17.5 | 29.9 | 34.2 | 65.0 |

| High Severity | |||||

| Prescription/OTC Medications | 65.6** | 19.9 | 39.4+ | 35.0** | 86.4*** |

| Topical Treatments | 40.7*** | 27.4 | 23.3* | 22.4+ | 63.4** |

| Movement, Exercise | 18.3 | 42.0 | 17.7 | 6.9** | 56.2 |

| Diet Supplements, Diet Change | 8.2 | 4.4 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 13.9 |

| Alternative Practices, (home remedies, meditation, prayer/religion) | 6.3 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 6.9 | 25.6 |

| Activity limitation/rest | 16.4 | 21.8 | 34.1 | 32.8 | 67.5 |

p ≤ .001

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .10.

Chi-square test for difference between low and high severity

Additional Measures

Our primary independent variables were race and severity of the osteoarthritis. Race was based on self-report, supplemented in a few cases by the Medicare Enrollment File classification because of missing data. Participants were classified as either white or African-American. Persons who were not white or African-American were excluded from the study. To assess osteoarthritis severity, we used the 10-item Lequesne Index (LI) for hip and knee osteoarthritis, which measures pain, stiffness, performance in activities of daily living, and the need for assistive devices (Lequesne et al., 1999 & 1987). This measure has been used as a measure of disease severity. Composite LI scores were categorized into the five severity groups suggested by Lequesne (1999), which range from mild to extremely severe. In categorical analyses, we defined states of mild to moderate (composite LI, 1−3) and more severe (LI, 4−5) disease.

In addition, we controlled for a number of demographic variables and variables hypothesized to influence the use of self-care, including gender, age, education (categorized as less than high school, high school, some college/vocational school, college degree), marital status (married, unmarried), self-reported health status as measured by the physical and mental health component summary scales of the SF-36 health quality of life survey (McHorney et al .,1994), and number of health conditions (from a list of 18 health conditions).

Findings

Description of the Study Population

The study participants consisted of slightly more African-Americans (51.5%) than whites; more females (61.2%) than men, and people who were, on average, 73.4 years of age. Close to half (43.5%) had some college education or a college degree. Almost half were married (49.9%). Overall, they had greater physical impairments than mental impairments as measured by the SF-36, and a mean of 5.1 health conditions. Severity as measured by the Lequesne Index (Lequesne et al., 1999 & 1987) was highest for blacks and females (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample Chi-square test or t-test for difference between low and high severity results shown

| Characteristic |

Total (N=551) |

Low Severity (N=234) |

High Severity (N=317) |

Sig.* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race (% Black) | 51.5 | 39.3 | 60.6 | <.001 |

| Gender (% Female) | 61.2 | 52.1 | 67.8 | <.001 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 73.4 ± 5.9 | 72.9± 5.7 | 73.7 ± 5.9 | .096 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than High School Degree (%) | 20.5 | 18.4 | 22.1 | .043 |

| High School Degree (%) | 35.9 | 32.1 | 38.8 | |

| Some College (%) | 28.3 | 29.9 | 27.1 | |

| College Degree (%) | 15.2 | 19.7 | 12.0 | |

| Marital Status (% Married) | 49.9 | 53.8 | 47.0 | .112 |

| SF-36 Physical Component Score (mean ± SD | 35.2 ± 9.7 | 40.1 ± 9.3 | 31.6 ± 8.4 | <.001 |

| SF-36 Mental Component Score (mean ± SD) | 53.8 ± 11.2 | 55.1 ± 9.6 | 52.8 ± 12.1 | .016 |

| Number of Health Conditions (mean ± SD) | 5.1 ± 2.1 | 4.7 ± 2.0 | 5.4 ± 2.2 | <.001 |

Responses to research questions

1) What did you do on a typical day over the past 30 days to manage your OA symptoms?

In response to this broad question about their self-care, the respondents reported a wide range of behaviors. One said, “Take medicine.” Another said, “Take Aleve®, Excedrin®, and do no exercise.” Still another said, “I take no medication, I don't believe in masking it.” Another reported, “I go on a walking machine,” and a number of respondents reported they did nothing. We tabulated the responses for this question and found that 60.1% reported using medications. Smaller numbers reported using topical treatments (33.9%), limiting their activity or resting (15.2%), using movement or exercise (17%), applying dietary changes or using supplements (8.9%), and using home remedies, meditation, religion/spirituality, or other miscellaneous treatments (5.3%) (as reported in the first column of Table 1).

When we assessed differences in responses when respondents’ symptoms were severe (as assessed by the Lequesne index), we found that significantly more people who classifed as high symptom severity were very likely to use medications (65.6% at p±< 0) and were somewhat more likely to use topical treatments (40.7% at p ±< .001) to relieve their symptoms than those with low symptom severity. (Table 1)

2. Comparisons by time of day: Patterns of self-care behaviors

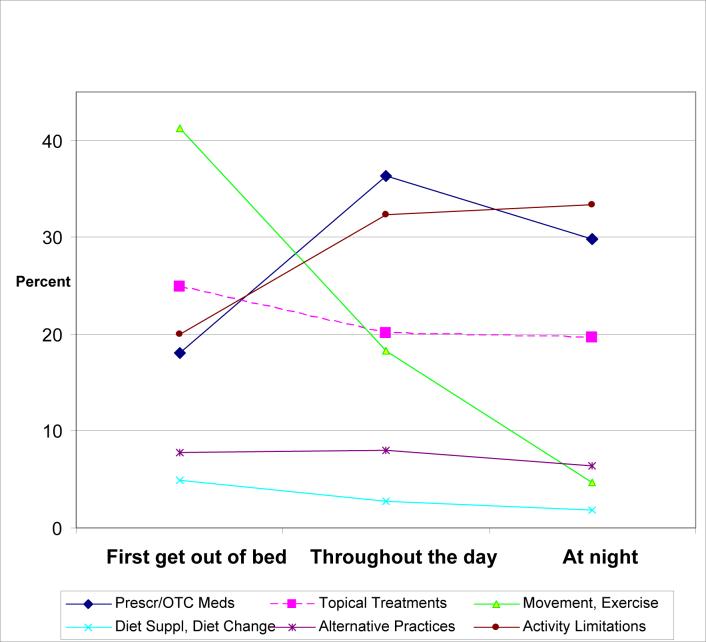

We next asked the respondents what they did to relieve the symptoms of their OA at specific segments of the day: when they first woke up, throughout the day, and at bedtime (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Use of Self Care on a Typical Day by Time of Day

The respondents then offered greater detail about their typcial daily routines. For example an African American man with OA of the hip reported that when he first wakes up, “It's usually not that bad, but I might have stiffness. Then I will move around, and the pain will start, and then I will take my medication. For the rest of the day “I do a lot of sitting,” “get off of it,” and “just relax.”

An African-American woman with OA of the knee reports a somewhat different strategy. She reports, “Sometimes in the morning, if it is sore, I will use a wet warm compress, and I will do no exercises, and I will take Celebrex®.” Later on, “If I get a pain, I will sort of exercise it. Or if I'm standing, I will bend it back or forth then sit down and put ut up. It does a good job of relieving the pain.”

Overall, the respondents reported using a variety of self-care treatments when they first got up in the morning, but the treatment they reported most frequently was movement or exercise (41.2%). Illustrations of this form of self-care behavior include:

“I lie in bed and do my exercise.”

“Sit on the side of the bed and stretch it.”

“Sit there for a few minutes if it is paining me, I walk around to get the kink out.”

“Just get up, get to walking, and exercise it back until it gets loose.”

Movement was used less frequently as the day went on, with respondents reporting using this strategy only 18.3% of the time throughout the day and much less (4.7%) by bedtime.

Despite what they reported doing for an entire day, the respondents did not report using medications as frequently as movement or exercise in the first part of the day. Only 18.0% reported use of medication when they first woke up, but this strategy increased considerably as the day wore on, peaking at 36.3% throughout the day and continuing to be useful at bedtime (29.8%). One respondent with OA of the knee reported that he takes Tylenol® when he first wakes up, if the pain gets worse during the day, and then again at night. At the same time, he uses other therapies such as rubbing his knees with Bengay® or other compounds like alchohol with wintergreen, he gets off his legs when the pain gets worse, and he takes a hot shower before he goes to bed.

A third self-care behavior widely reported for relieving the symptoms of OA was limiting activity or rest. This strategy was most commonly used througout the day (32.3%) as well as into nighttime (33.4%), but only 20% of respondents reported using it in the early morning hours. It was often used in combination with other strategies (such as lotions, self massage, medications). Examples of the specific uses of rest include:

“Just get off of it.”

“Prop legs up in my chair.”

“Rest and elevate it.”

“Stay off of it and rest until the pain goes away.”

Respondents commonly reported the use of topicals (creams, hot or cold treatments) to relieve symptoms throughout the day. Their greatest use of topicals was in the morning (24.9%), decreasing to 20.1% during the day and 19.6% at night. For example, a respondent with OA of the knee said he starts the day with a “warm bath or shower, hot water at my knees, then I use Jointritis®, or Bengay®.”

Another respondent with OA of the knee indicated that in the morning, he rubs his knees with Jointritis®. Two or three times during the day, he will stop (his activity) and rub his knees with Jointritis®. If the pain gets worse, “I get a hot compress and put it on.”

Respondents reported two additional patterns of self-care behavior, but their use was much less frequent than those illustrated previously. Diet modification, such as ingesting certain foods or drinks or taking diet supplements, was used throughout the day to relieve symptoms by fewer than 10% of the respondents. Examples of this strategy include the woman who reported that at bedtime, “I sit down, and get a glass of orange juice and two tablespoons of sherry, and the pain goes away,” or the man who reported that he takes shark cartilage pills and methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) pills throughout the day.

Fewer than 10% of respondents reported the use of miscellaneous strategies such as meditation, religion or prayer, or home remedies such as devices to support a painful knee or a combination of those behaviors. For example, a respondent might use such expressive behaviors as, “I thank God for another day,” or, “I pray,” but also use instrumental behaviors such as:

“I put a pillow under my knee... that helps.”

“If the pain gets bad, I will get in a recliner chair.”

3) What do you do when your pain worsens during the day?

Assuming there would be times when the pain worsened, we asked the respondents to tell us what they did to alleviate their symptoms when this occurred. The most frequently reported response was that they limited their activity or rested (41%). They also reported using topicals (23.4%) and medication (27.8%) almost equally, but much less than limiting activity. For example, one man with hip OA reported that when it gets worse, “I get off it.” Later in the day, before bedtime, he reported, “I just relax. I don't have that much pain if I get off of it.”

Those experiencing higher symptom severity (vs. lower severity) reported significantly greater use of limiting activity or rest (45.1% vs 35.5% at p± < .05); they also reported using medication more, 30.6% vs 23.9 % at p± < .10%. (See Table 3.)

Table 3.

Use of Self-Care When Pain Gets Worse by Severity (Percent indicating use)

| Total | Low Severity | High Severity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prescription/OTC Medications | 27.8 | 23.9 | 30.6+ |

| Topical Treatments | 23.4 | 21.8 | 24.6 |

| Movement, Exercise | 9.3 | 8.1 | 10.1 |

| Diet Supplements, Diet Change | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.6 |

| Alternative Practices, (home remedies, meditation, prayer/religion) | 6.5 | 5.1 | 7.6 |

| Activity limitation | 41.0 | 35.5 | 45.1* |

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .10.

Chi-square test for difference between low and high severity.

4 Differences in self-care behaviors by race and severity

On the whole, African-Americans and whites used similar types of self-care behaviors to manage the symptoms of their OA (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Self Care by Race

There were some differences, however. African-Americans limited their activity or rested much less than whites throughout the day (39.7% for whites and 25.5% for blacks), but they used other strategies more. African-Americans were more likely to take medications throughout the day (39.8% vs. 32.6% for whites) and use topical treatments at all times of the day, especially at bedtime (24.6% compared to 14.2% for whites). Neither group reported extensive use of home remedies, religion or spirituality, or meditation, but African-Americans used miscellaneous strategies more than whites at all times throughout a typical day. These might include both expressive methods such as prayer or instrumental methods such as a special reclining chair or pillow positioned to relieve the pressure.

For example, an African-American man with OA of the knee reported that he “rubs the knee with linament or solvent” throughout the day. He added, “Sometimes you have to take a couple more Tylenols® and ice it down 10−15 minutes, 2 times a day.” When it gets worse, “you try to sleep.” At night, “(I) rub the knee with solvent and take some Tylenol PM®.

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the effects of severity and race on [total/overall] use of each type of self-care on a typical day while controlling for covariates (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Results for Use of Self-Care (Total Usage on Typical Day)

| Prescription/OTC Medications OR (95% CI) | Topical Treatments Self-Massage OR (95% CI) | Movement, Exercise OR (95% CI) | Diet Supplements, Diet Change OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) Alternative Practices, (home remedies, meditation, prayer/religion) | OR (95% CI) Activity limitation/rest | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ||||||

| High Severity | 1.69 (1.01, 2.82)* | 1.21 (0.81, 1.81) | 0.93 (0.62, 1.37) | 0.88 (0.52, 1.49) | 1.01 (0.64, 1.61) | 1.69 (1.01, 2.82)* |

| Black | 0.85 (0.52, 1.38) | 1.83 (1.26, 2.67)** | 1.64 (1.13, 2.38)** | 0.58 (0.35, 0.98)* | 1.39 (0.90, 2.15) | 1.18 (0.80, 1.74) |

| Female | 1.54 (0.93, 2.57)+ | 1.76 (1.18, 2.61)** | 0.82 (0.56, 1.21) | 1.32 (0.77, 2.27) | 1.29 (0.81, 2.06) | 0.85 (0.58, 1.25) |

| Age | 0.93 (0.90, 0.97)*** | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) |

| Education | 0.88 (0.70, 1.12) | 0.95 (0.79, 1.15) | 1.00 (0.83, 1.20) | 1.22 (0.95, 1.58) | 0.93 (0.75, 1.16) | 0.97 (0.80, 1.17) |

| Married | 1.11 (0.67, 1.84) | 1.18 (0.79, 1.75) | 1.21 (0.82, 1.78) | 1.00 (0.59, 1.69) | 0.69 (0.44, 1.08) | 0.89 (0.60, 1.33) |

| Physical Component Score (SF-36) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) |

| Mental Component Score (SF-36) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00)+ | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) |

| Number of health conditions | 1.07 (0.95, 1.22) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 0.95 (0.83, 1.08) | 1.05 (0.94, 1.17) | 1.54 (1.33, 1.78)*** |

p ≤ .001

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .10

With regard to severity, persons with higher severity levels of OA were more likely to take prescription or OTC medications (OR 1.69) and to limit their activity and rest more (OR 1.69). However, greater severity of OA was not significantly associated with the use of topical treatments, increased movement or exercise, taking diet supplements or changing diets, and /or miscellaneous strategies. African-Americans were significantly more likely than whites to utilize topical treatments (OR 1.83) and movement or exercise (OR 1.64) to treat their OA, but were less likely to utilize diet supplements or diet change (OR 0.58) after adjusting for the covariates. Additional significant associations with self-care for OA among the covariates included:

Females were more likely to utilize topical treatments (OR 1.76),

Older adults were less likely to take prescription or OTC medications (OR 0.93), and

Those with a greater number of health conditions (co-morbidities) were more likely to limit their activity and rest more (OR 1.54).

Discussion and Conclusions

OA is among the most prevalent chronic diseases in the U.S. For the most part, treatment for its symptoms relies on self management. To address some of the gaps in the research on self-care for OA, we undertook a descriptive study of 551 older African-Americans and whites (approximately 50% of each). Study participants were asked to report how they dealt with the troublesome symptoms of OA on a typical day and on segments of a typical day over the past 30 days. Using an in-depth qualitative approach to derive information about what these people do to manage their illness, we were able to describe a set of behaviors that are used to deal with routine and worsening symptoms of OA, address differences in self-care behaviors by high and low severity, and compare the self-care behaviors of older African-Americans to those of older whites with the same illness.

For an entire typical day, use of medications was reported most frequently. Participants reported the use of topical treatments somewhat less frequently. Participants with the most severe OA reported more frequency of use of these treatments. When we questioned what the respondents did during segments of the day (when they first woke up, throughout the day, when they went to bed, and when their symptoms worsened), we found differences in types of self-care strategies by the time of day, worsening of the illness, severity of the illness and race.

African-American daily self-care behaviors

Because there is little information on what African-Americans do to manage their chronic illnesses (Verbrugge & Ascione, 1987; Silverman et al., 1999; Becker, 2004; Ang et al., 2002; Charmaz, 1991; Kart & Engler, 1994; Reid, 1992; Davis & Wykle, 1998) and particularly what their daily self-care practices are (Becker, 2004), we undertook a study that would compare the daily self-care behaviors of African-Americans and whites for the total day and within segments of the day. We found that on the whole, there were similarities in their OA self-care strategies. African-Americans, like their white counterparts, reported using the common and appropriate remedies for OA including avoiding pain, exercise, using heat, and controlling fatigue (Lorig et al. 2000, p.267). When we assessed self -care behaviors over an entire “typical” day, the use of medications (OTC and prescribed) and, to a lesser extent, topical treatments (such as creams, hot and cold , and self massage) were the predominant forms of self-care for the total group. When we questioned the respondents about what they did during specific times of the day or when the symptoms worsened, we found differences between the self-care behaviors of African-Americans and whites.

African-Americans limited their activity or rested much less than whites throughout the day, but they used other strategies more, including taking medications throughout the day and using topical treatments throughout the day and at bedtime. Although both groups used movement and exercise extensively at the start of the day, blacks did so more.

Although neither group reported using alternative treatments to any great extent, African-Americans reported using more than whites throughout the day. Other researchers have noted that African-Americans commonly make use of prayer or spirituality in the management of their chronic illness, (Harvey & Silverman, 2007; Ang, 2002). We did not find that this strategy was frequently reported in this study. Reasons for the disparities between our findings and those of others may have to do with our qualitative design that did not target specific categories but relied on the unprompted responses of the respondents.

The difference in the patterns of self-care behaviors between African-Americans and whites is intriguing and prompts us to question why particular behaviors are used more by one group than another. One explanation for the greater use of medications and other pain relieving treatments by African-Americans may be that, on the whole, they were experiencing greater severity of the illness than the whites. African-Americans were significantly more likely than whites to use topical treatments and movement or exercise to treat their OA when the disease was severe and less likely to use diet change after adjusting for covariates.

Becker et al., (2004) offer another explanation for the differences in choices of self-care options by African-Americans. They report that, “Self-care practices among African-Americans were found to be culturally based.” They add,“ Respondents described idea systems and behavioral practices that were shared by the sample with respect to general issues of self -care for protecting health, preventing illness, and promoting healing and recovery from illness. These cultural approaches to self-care formed the basis from which individuals developed strategies specific to the particular parameters of their illnesses (p. 2068)”. Although these explanations for differences between African-Americans and whites are intriguing, further research on the self-care behaviors of older African-Americans with chronic illness is needed to elaborate the motivations and influences that contribute to the choice of particular self-care strategies.

Illness severity

The assessment of self-care by severity is a critical dimension to a fuller understanding of the strategies used for the relief of symptoms of chronic illnesses (Verbrugge & Ascione, 1987). As demonstrated, African-Americans and whites responded to illness severity differently. We also noted variations in self-care among both blacks and whites when the disease was assessed as high severity versus low severity. Specific pain relieving strategies, such as medications, topicals, and rest, tended to be used more by those with high severity. Analysis to examine the effects of severity and race on total use over the full typical day of each type of self-care while controlling for covariates found that persons with high severity were more likely to take prescriptions or over-the-counter medications and to limit their activity or rest. Further study is needed to assess why particular strategies for pain relief are more useful or are chosen by persons with low severity of disease rather than high severity (and vice versa).

Methodological issues

By asking about what self-care behaviors were used at different segments of the day, we were better able to capture behaviors associated with those time periods and therefore provide a fuller and richer profile of self care strategies of African-Americans and whites in the management of their OA. The value of this approach became even clearer when we compared the responses given by the respondents about what they did on a typical day to what they did when they first woke up and at other segments of the day. The responses to the segments of the day were far more detailed and included information not provided when they were first asked about the full day. For example, we might not have learned that African-Americans use diet supplements or diet change more at night or that they used movement and exercise more in the morning than at other times of the day had we only used the global question (the entire day).

The use of an in-depth qualitative approach has some advantages over the survey or structured approaches in that it allows for the discovery of actions or behaviors not originally recognized by the researcher. The emic, or bottom up, approach also allows for interpretations of why certain actions may be taken, as described by Becker et al., (2004) and others (Patton, 1990; Rubinstein, 1997; Ruggeri, 2003).

There are, of course, limitations to data collection that is focused on the emic rather than the etic (top-down) approach and on specific temporal segments of daily life. For example, because we did not focus on meal times, we may be missing information on when and if respondents take medications that are prescribed for use at or after mealtimes or other specific times of the day (e.g., three times a day). We did not ask targeted questions about medications, or other treatments, or behaviors such as the use of alternative treatments as some surveys of self-care behaviors do. We may, therefore, be overlooking some self-care behaviors that are routinely used. However, by using this approach early on, we were able to identify specific behaviors such as rest or limiting activity that were not widely reported in later sections of the baseline interview. These behaviors provided a more comprehensive profile of self-management of OA.

Another limitation to the study may be the coding of self-care behaviors. Some researchers would combine or cluster the responses differently, perhaps clustering behaviors such as using topical treatments or self-massage into CAM (Arcury et al., 2007 & 1996 & others) rather than into independent categories as we did. A consistent system for defining and coding self-care behaviors remains one of the enigmas of this area of research.

There are multiple advantages to this descriptive study. It can serve as a guide to future research on self-care behaviors and a demonstration of the utility of obtaining detailed information on the behaviors of older adults with varying degrees of illness. The study revealed the varying practices of differing populations. In addition, it allowed us to understand the process of disease self-management in a microcosm of daily segments that is rarely reported.

Methodologists have debated the advantages and disadvantages of each approach (qualitative or quantitative) (Inui, 1996). We suggest that a combination of both approaches might build on the strengths of each while compensating for some of the weaknesses.

Clinical Relevance

Knowledge about what behaviors individuals use to relieve their symptoms and how they change during typical and atypical times and among differing populations of older adults will permit physicians to better tailor interventions such as educational programs for arthritis management. Knowing the methods and techniques used by this population may enable other patients to improve their illness management skills and quality of life, despite an illness for which there is no definitive cure and which is experienced over long time periods. Recognition of which persons sometimes substitute or complement medical treatments with non-medical ones (Verbrugge & Ascione, 1987) may further enable practitioners to understand and translate useful self-care strategies to their patients.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the upport for this research which was provided by a grant from the National Institute on Aging R01 AG 018308. We also acknowledge the support of Pam Ostreicher for providing editorial and substantive comments on earlier drafts and the staff support provided by Celeste Petruzzi in the preparation of this manuscript. We are most grateful to the receptivity and patience of our respondents who allowed us to interview them in person sometimes for several hours.

References

- Albert SM, Musa D, Kowh CK, Hanlon J, Silverman M. Self-Care and Professionally-Guided Care in Osteoarthritis. Journal of Health and Aging. 2008 doi: 10.1177/0898264307310464. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke TD, Greenwald R, Hochberg M, Howell D, Kaplan D, Koopman W, Longley S, Mankin H, McShane DJ, Medsger T, Meenan R, Mikkelsen W, Moskowitz R, Murphy W, Rothschild B, Segal M, Sokoloff L, Wolfe F. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman RD, Hochberg MC, Moskowitz RW, Schnitzer TJ. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2000;43(9):1905–1915. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1905::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-P. update. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang DC, Ibrahim SA, Burant CJ, Siminoff LA, Kwoh CK. Ethnic Differences in the Perception of Prayer and Consideration of Joint Arthroplasty. Medical Care. 2002;40(6):471–476. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200206000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG, Bell RB, Neiberg RH, Lang W, Quandt S. Herbal Remedy Use as Health Self-Management Among Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62(Suppl):142–49. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Bernard SL, Jordan JM, Cook HL. Gender and Ethnic Differences in Alternative and Conventional Arthritis Remedy Use Among Community-Dwelling Rural Adults with Arthritis. Alternative and Conventional Remedy Use. 1996;9(5):384–390. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199610)9:5<384::aid-anr1790090507>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G, Kaufman SR. Managing an uncertain illness trajectory in old age: Patients and physicians views of stroke. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1995;9(2):165–187. doi: 10.1525/maq.1995.9.2.02a00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G, Gates RJ, Newsom E. Self-Care Among Chronically Ill African Americans: Culture, Health Disparities, and Health Insurance Status. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2066–2073. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd EL, Taylor SD, Shimp LA, Semler CR. An assessment of home remedy use by African Americans. J Natl Med Association. 2000;92(7):341–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Good Days, Bad Days: The Self in Chronic Illness and Time. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, N. J.: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WI. Doing Qualitative Research: Research Methods for Primary Care. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Davis L, Wykle ML. Self-Care in minority and ethnic populations: the experience of older black Americans. Springer Publishing; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Davis LH, McGadney BF. In: Self-Care Practices of Black Elders. Ethnic Elderly and Long-Term Care. Barresi CM, Stull DE, editors. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 1993. pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dean K. Conceptual, Theoretical and Methodological Issues in Self-Care Research. Social Science and Medicine. 1989a;29(2):137–152. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean K. Self-Care Components of Lifestyles: The Importance of Gender, Attitudes, and the Social Situation. Social Science & Medicine. 1989b;29(2):137–152. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean K. In: Health-related behavior: concepts and methods. Aging, Health, and Behavior. Ory MG, Abeles RP, Lipman DP, editors. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, Calif: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- DeFriese G, Konrad T, Woomert A, Noburn J, Bernard S. In: Self-Care and Quality of Life in Old Age. Aging and Quality of Life. Abeles RP, Gift HC, Ory MG, editors. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dill A, Brown P, Ciambrone D, Rakowski W. The Meaning and Practice of Self-Care by Older Adults. Research on Aging. 1995;17(1):8–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon CJ, Rasch EK, Gu Q, Hirsch R. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991−94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey IS, Silverman M. The role of spirituality in the self-management of chronic illness among older adults. 2007;22:205–220. doi: 10.1007/s10823-007-9038-2. http://apha.confex.com/apha/133am/techprogram/paper_108971.htm. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, Published online 3/17/07, Springer Science and Business Media LLC 2007. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2007.

- Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Variations in perceptions of treatment and self-care practices in elderly with osteoarthritis: a comparison between African American and white patients. Arthritis Care & Research. 2001;45(4):340–345. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)45:4<340::AID-ART346>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui TS. The Virtue of Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1996;125:770–771. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-9-199611010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kart CS, Engler CA. Predisposition to Self-Health Care: Who Does What for Themselves and Why? Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49(6):S301–S308. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.6.s301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keysor JJ, Currey SS, Callahan LF. Behavioral Aspects of Arthritis and Rheumatic Disease Self-Management. Dis Manage Health Outcomes. 2001;9(2):89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Keysor JJ, DeVellis BM, DeFreise GH, Devellis RF, Jordan JM, Konrad TR, Mutran EJ, Callahan LF. Critical Review of Arthritis Self-Management Strategy Use. Arthritis & Rheumatism. Arthritis Care & Research. 2003;49(5):724–731. doi: 10.1002/art.11369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, Heyse SP, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, Liang MH, Pillemer SR, Steen VD, Wolfe F. Estimates of the Prevalence of Arthritis and Selected Musculoskeletal Disorders in the United States. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1998;41(5):778–799. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lequesne MG, Mery C, Samson M, Gerard P. Indexes of Severity for Osteoarthritis of the Hip and Knee: Validation-Value in Comparison with Other Assessment Tests. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 1987;65:85–89. doi: 10.3109/03009748709102182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lequesne MG. The Algofunctional Indices for Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis. Journal of Rheumatology. 1999;24(4):779–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Holman H, Sobel D, Laurent D, González V, Minor M. Living a Healthy Life with Chronic Conditions. Bull Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of Data Quality, Scaling Assumptions, and Reliability Across Diverse Patient Groups. Medical Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory MG, DeFriese GH. Self Care in Later Life: Research, Program, and Policy Perspectives. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage Publications; Newbury Park: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Reid BV. It's Like You're Down on a Bed of Affliction: Aging and Diabetes Among Black Americans. Social Science and Medicine. 1992;34(12):1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90140-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein R. In: In-depth interviewing and the structure of its insights. Reinharz S, Rowles G, editors. Qualitative Gerontology Springer; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggieri A. Good Days and Bad Days: Innovation in Capturing Data About the Functional Status of Our Patients. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2003;49(6):853–857. doi: 10.1002/art.11457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg NE, Amey CH, Stoller EP, Drew EM. The pivotal role of cardiac self-care in treatment timing. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(5):1047–60. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg NE, Drungle SC. Barriers to non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) self-care practices among older women. Journal of Health and Aging. 2001;13(4):443–466. doi: 10.1177/089826430101300401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman M, Musa D, Kirsch B, Siminoff L. Self care for chronic illness: Older African Americans and whites. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1999;14:169–189. doi: 10.1023/a:1006676416452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel DS. Rethinking medicine: improving health outcomes with cost-effective psychosocial interventions. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:234–44. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoller EP. Interpretations of Symptoms by Older People: A Health Diary Study of Illness Behavior. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993a;5:58–81. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoller EP, Forster LE, Portugal S. Self-Care Responses to Symptoms by Older People. Medical Care. 1993b;31(1):24–42. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage; Newbury Park: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM, Ascione FJ. Exploring the Iceberg: Common Symptoms and How People Care for Them. Medical Care. 1987;25(6):539–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]