Abstract

A highly practical and readily available proline surrogate has been developed with improved solubility properties in common, nonpolar organic solvents. This sulfonamide-based catalyst has proven highly effective at facilitating enantioselective and diastereoselective aldol reactions with a range of substrates in nonpolar organic solvents in the presence of a single equivalent of water. Additionally, catalyst loading as low as 2 mol % can be employed in the absence of any organic solvent with continued high levels of selectivity.

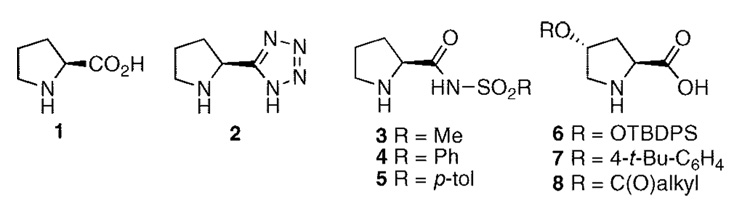

Since the early days of enantioselective Robinson annulations facilitated by proline,1 organocatalysis has garnered the attention of the synthetic community. The explosion of research in this area in recent years has been fueled by the general mildness of the conditions, the relative ease of execution, and the wide variety of chemical transformations that are possible.2 Proline 1 has attracted significant attention in this area—particularly in the role of facilitating aldol reactions (Figure 1).3–5 Despite proline’s utility in facilitating an organocatalyzed process, it is not without its short-comings.6 Consequently, a range of proline mimetics has been created to provide an improved reactivity profile. Two commonly employed classes are the tetrazole 27 and sulfonamides3–5.8 Derivatives of 4-trans-hydroxyproline (e.g.,6–8) have been utilized in organocatalysis;9 however, these substrates suffer from the fact that only one enantiomer of trans-hydroxyproline is readily available. More substantially different structures have also been introduced by Mauroka,6b,10 Jørgensen,11 and others.12 It is important to note that the vast majority of organocatalyzed processes involving proline or proline surrogates employ polar solvents such as DMF and DMSO.7a,8c While these solvents are commonly used in research laboratories, their polarity creates added hurdles for product isolation. Nonpolar solvents have industrial advantages by providing good phase splits with water and are more easily recycled on scale.13 We were also cognizant of the need for any proline mimetic to be readily accessible for inexpensive starting materials in both enantiomeric forms. In this Letter, we disclose the development of a practical solution for these challenges.

Figure 1.

Proline and select proline mimetics.

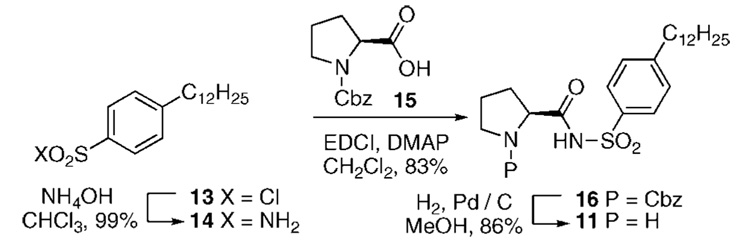

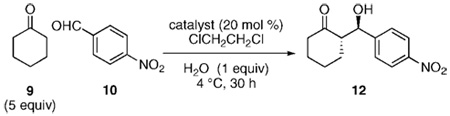

To explore the effects of solvent polarity, the solubility of catalysts 1–5 in methylene chloride was screened. Surprisingly, the solubility properties for each of these compounds were quite poor (<5 mg/mL). The absence of a significant nonpolar region to molecules 1–5 is one possible hypothesis to explain the origin of this poor solubility. Consequently, we developed a new sulfonamide catalyst 11 that possessed a sizable hydrocarbon chain in the para position of the aromatic ring. This sulfonamide 11 is readily accessible from the commercially available p-dodecylsulfonyl chloride (13)14,15 and Cbz-protected proline 15 in 3 steps (Scheme 1; Table 1). Sulfonamides are ideal choices for proline mimetics as their pKa has been documented to nicely match that of proline.8c,16 In contrast to catalysts 1–5, sulfonamide 11 displays impressive solubility in methylene chloride (300 mg/mL). The aldol reaction between cyclohexanone (9) and p-nitrobenzaldehyde (10) in methylene chloride with sulfonamide 11 provided the desired product 12 in reasonable ee and dr (entry 1); however, the yield of this transformation was somewhat disappointing (51%). Use of dichloroethylene (DCE) led to an appreciable rate increase(entry 2).17 Further improvement was found by using a DCE/EtOH mixed solvent system (99:1) (entry 3). Alternatively, a single equivalent of water had a similar rate accelerating effect9a,b and with the added benefit of increased diastereoselectivity (entry 4). The optimum reaction conditions included cooling of the reaction to 4 °C with a 30 h reaction time (entry 5).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Sulfonamide 11

Table 1.

Optimization of Reaction Conditions with Sulfonamide 11

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | conditionsa | additive | % yield(drb) | %eec |

| 1 | CH2Cl2, rt, 36 h | 51 (15:1) | 97 | |

| 2 | ClCH2CH2Cl, rt, 46 h | 92 (12:1) | 95 | |

| 3 | ClCH2CH2Cl, rt, 36 h | EtOH (1%) | 96 (14:1) | 97 |

| 4 | ClCH2CH2Cl, rt, 36 h | H2O (1 equiv) | 96 (36:1) | 97 |

| 5 | ClCH2CH2Cl,4 °C, 30 h | H2O (1 equiv) | 95 (>99:1) | 99 |

All reactions were performed at 1 M.

dr was determined by 1H NMR.

ee was determined by chiral HPLC, using a Daicel AD column.

A direct comparison between sulfonamide 11 and a series of commonly used organocatalysts is provided in Table 2. Each of the known catalysts 1–5 facilitated the transformation with good enantioselectivity (98–99% ee); however, only the tetrazole 2 is able to provide a reasonable yield (91%) for this transformation (entry 2). Unfortunately, the diastereoselectivity with the tetrazole catalyst 2 (7:1 dr) is significantly below that of the sulfonamides (entries 3–6). In contrast, our p-dodecylphenylsulfonamide catalyst 11 provided excellent diastereoselectivity, enantioselectivity, and chemical yield for this transformation (entry 6). It is important to note that the standard proline-based conditions for this transformation (DMSO, rt) have been shown to perform less effectively [65%, 1.7:1 dr, 67% ee (syn), 89% ee (anti)].4

Table 2.

Comparison of Select Proline Mimetics

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst | % yield | % eea | drb |

| 1 | 1 | 22 | 98 | 13:1 |

| 2 | 2 | 91 | 98 | 7:1 |

| 3 | 3 | 42 | 99 | 65:1 |

| 4 | 4 | 49 | 98 | 83:1 |

| 5 | 5 | 52 | 99 | 92:1 |

| 6 | 11 | 95 | 99 | >99:1 |

ee was determined by chiral HPLC, using Daicel AD column.

dr was determined by 1H NMR.

Next, focus was shifted to screening the utility of our sulfonamide catalyst 11 for facilitating aldol reactions across a range of substrates (Scheme 2). We were able to access aldol adducts 17–27 derived from their corresponding aldehydes and cyclohexanone. Additionally, 4-methylcyclohexanone (28) proved to be a competent substrate for these conditions.18 Dihydroxyacetone equivalent 30 and pyran-4-one (32) also were effective in this transformation to provide aldol adducts 31 and 33–35. Finally, we were pleased to find that this transformation is effective with acetone (36) to provide adducts 37–38 in reasonable enantioselectivities.

Scheme 2.

Exploration of Substrate Scope with Sulfonamide Catalyst 11a

aThe ratio of ketone to aldehyde was 5:1. bThis reaction was conducted at room temperature. cThis reaction was performed without the addition of H2O.

Extension to cyclopentanone (39) revealed some interesting results (Scheme 3). The optimized 1 equiv of water conditions gave poor diasteroselectivity in the transformation [94%, 1.35:1 (40:41), 87–95% ee]. In contrast, the DCE/ EtOH (99:1) solvent system gave improved levels of diastereoselectivity favoring the syn product 40. Limited prior examples of syn selective aldol reactions with cyclopentanone have been reported.8c,19 Interestingly, slightly improved levels of syn selectivity are observed at room temperature (syn-40: 71%, 77% ee; anti-41: 26%, 80% ee), but with reduced enantioselectivity.

Scheme 3.

Select Examples with Cyclopentanone

Finally, we have found that we can perform aldol reactions with catalyst loading as low as 2 mol % if the reaction is performed neat (Scheme 4). Under these conditions, a single equivalent of water was still added to the reaction to improve reaction rate and selectivity.9a,b As seen in the previous examples, these transformations generally proceeded in good to excellent diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity. We have demonstrated the practicality of this process by preparing 1 mol of the aldol adduct 12 (Scheme 5) using a 500 mL round-bottomed flask in excellent diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity (88% yield, 97% ee, 98:1 dr). We were also able to recover over 60% of the catalyst 11 via a single crystallization.

Scheme 4.

Select Aldol Reactions Using Low Catalyst Loadinga

aThe ratio of ketone to aldehyde was 2:1.

Scheme 5.

Large Scale Example of Enantioselective Aldol Reaction

In conclusion, a highly practical and readily available proline mimetic 11 has been developed. The sulfonamide 11 can be prepared from commercially available and inexpensive d-or l-proline. This important attribute is not shared by 4-trans-hydroxyproline derivatives where only one of the two enantiomers is commercially available at a reasonable price. This catalyst 11 has been shown to be effective at facilitating a range of aldol reactions with some of the highest levels of diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity reported for many of these transformations.3,4,7–12 Further applications of this catalyst 11 will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgment

Financial support was provided in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (GM63723) and the Oregon State University (OSU) Venture Fund. The authors would like to thank Professor Max Deinzer and Dr. Jeff Morré (OSU) for mass spectra data and Synthetech, Inc. for the generous gift of compound 15. Finally, the authors are grateful to Dr. Roger Hanselmann (Rib-X Pharmaceuticals) for his helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Complete experimental procedures are provided, including 1H and 13C spectra, of all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Hajos ZG, Parrish DR. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:1615–1621. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hajos ZG, Parrish DR. Org. Synth. 1990;7:363–367. [Google Scholar]; (c) Buchschacher P, Fürst A, Gutzwiller J. Org. Synth. 1990;7:368–372. [Google Scholar]; (d) Barbas CF., III Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:42–47. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. For recent reviews, see: Dondoni A, Massi A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:4338–4360. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704684. Longbottom DA, Franckevicius V, Kumarn S, Oelke AJ, Wascholowski V, Ley SV. Aldrichim. Acta. 2008;41:3–11. Enders D, Grondal C, Hüttl MRM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:1570–1581. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603129. Lelias G, MacMillian DWC. Aldrichim. Acta. 2006;39:79–87. Houk KN, List B, editors. Acc. Chem. Res. Vol. 37. 2004. Issue 8: Asymmetric Organocatalysis; pp. 487–631.

- 3. For recent reviews, see: Kotsuki H, Ikishima H, Okuyama A. Heterocycles. 2008;75:493–529. Guillena G, Najera C, Ramon DJ. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2007;18:2249–2293.

- 4.(a) List B, Lerner RA, Barbas CF., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2395–2396. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sakthivel K, Notz W, Bui T, Barbas CF., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5260–5267. doi: 10.1021/ja010037z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Northrup AB, MacMillan DWC. Science. 2004;305:1752–1755. doi: 10.1126/science.1101710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Northrup AB, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6798–6799. doi: 10.1021/ja0262378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Orsini F, Pelizzoni F, Forte M, Destro R, Gariboldi P. Tetrahedron. 1998;44:519–541. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kano T, Takai J, Tokuda O, Maruoka K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:3055–3057. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Cobb AJA, Shaw DM, Ley SV. SYNLETT. 2004:558–560. [Google Scholar]; (b) Knudsen KR, Mitchell CET, Ley SV. Chem. Commun. 2006:66–68. doi: 10.1039/b514636d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hartikka A, Arvidsson PI. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:1831–1834. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berkessel A, Koch B, Lex J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1141–1146. Dahlin N, Bøegevig A, Adolfsson H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1101–1105. Cobb AJA, Shaw DM, Longbottom DA, Gold JB, Ley SV. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:84–96. doi: 10.1039/b414742a. Sundén H, Dahlin N, Ibrahem I, Adolfsson H, Córdova A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:3385–3389. Bellis E, Vasiatou K, Kokotos G. Synthesis. 2005:2407–2413. Wu Y, Zhang Y, Yu M, Zhao G, Wang S. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4417–4420. doi: 10.1021/ol061418q. Silva F, Sawicki M, Gouverneur V. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5417–5419. doi: 10.1021/ol0624225. For related series, see: Wang X-J, Zhao Y, Liu J-T. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1343–1345. doi: 10.1021/ol070217z. Zu L, Xie H, Wang J, Wang W. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1211–1214. doi: 10.1021/ol800074z.

- 9.(a) Hayashi Y, Sumiya T, Takahashi J, Gotoh H, Urushima T, Shoji M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:958–961. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Aratake S, Itoh T, Okano T, Nagae N, Sumiya T, Shoji M, Hayashi Y. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:10246–10256. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Huang J, Zhang X, Armstrong DW. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:9073–9077. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kano T, Tokuda O, Takai J, Maruoka K. Chem. Asian J. 2006;1:210–215. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halland N, Hazell RG, Jorgensen KA. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:8331–8338. doi: 10.1021/jo0261449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. For selected examples, see: Tang Z, Jiang F, Cui X, Gong L-Z, Mi A-Q, Jiang Y-Z, Wu Y-D. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:5755–5760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307176101. Bellis E, Kokotos G. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:8669–8676. Liu Y-X, Sun Y-N, Tan H-H, Liu W, Tao J-C. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2007;18:2649–2656. Hayashi Y, Urushima T, Aratake S, Okano T, Obi K. Org. Lett. 2008;10:21–24. doi: 10.1021/ol702489k. Font D, Sayalero S, Bastero A, Jimeno C, Pericas MA. Org. Lett. 2008;10:337–340. doi: 10.1021/ol702901z.

- 13.(a) Aycock DF. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2007;11:156–159. [Google Scholar]; (b) Butters M, Catterick D, Craig A, Curzons A, Dale D, Gillmore A, Green SP, Marziano I, Sherlock J-P, White W. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3002–3027. doi: 10.1021/cr050982w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Constable DJC, Jimenez-Gonzalez C, Henderson RK. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2007;11:133–137. [Google Scholar]; (d) Delhaye L, Ceccato A, Jacobs P, Kottgen C, Merschaert A. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2007;11:160–164. [Google Scholar]; (e) Fuenfschilling PC, Hoehn P, Mutz J-P. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2007;11:13–18. [Google Scholar]; (f) Anderson NG. Practical Process Research & Development. New York: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wako Chemicals Catalog Number 040-19872.

- 15.Compound 13 is sold as a mixture of isomers on the C12H25 alkyl chain. No attempt was made to separate the isomers in this sequence and the isomeric mixture does not appear to adversely affect the reactivity.

- 16.It is important to note that Hayashi and co-workers recently published the synthesis of two long alkyl chain (nonaromatic) sulfonamides; however, these sulfonamides did not provide optimum results in their analysis. We attribute the divergent reactivity to a likely difference in the pKa of a alkyl sulfonamide versus an aryl sulfonamide. Aratake S, Itoh T, Okano T, Nagae N, Sumiya T, Shoji M, Hayashi Y. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:10246–10256. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700363.

- 17.(a) Li H, Wang J, E-Nunu T, Zu L, Jiang W, Wei S, Wang W. Chem. Commun. 2007;50:7–509. doi: 10.1039/b611502k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Carlson EK, Rathbone LK, Yang H, Collett ND, Carter RG. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:5155–5158. doi: 10.1021/jo800749t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo S, Xu H, Li J, Zhang L, Mi X, Zheng X, Cheng J-P. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:11307–11314. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Gryko D, Zimnicka M, Lipinski R. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:964–970. doi: 10.1021/jo062149k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zheng J-F, Li Y-X, Zhang S-Q, Yang S-T, Wang X-M, Wang Y-Z, Bai J, Liu F-A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:7793–7796. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tang X, Liégault B, Renaud J-C, Bruneau C. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2006;17:2187–2190. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cheng C, Sun J, Wang C, Zhang Y, Wei S, Jiang F, Wu Y. Chem. Commun. 2006:215–217. doi: 10.1039/b511992h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kucherenko AS, Struchkova MI, Zlotin SG. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:2000–2004. [Google Scholar]