Abstract

In severe forms of osteogenesis imperfecta, multiple compression fractures of the spine, as well as vertebral height shortening could be responsible for an increased thoracic kyphosis or a diminished lumbar lordosis. Theses progressive changes in sagittal shapes of the trunk could be responsible for a global sagittal trunk imbalance. We compare the parameters of sagittal spinopelvic balance in young patients with OI to those parameters in a control group of healthy volunteers. Eighteen patients with osteogenesis imperfecta were compared to a cohort of 300 healthy volunteers. A standing lateral radiograph of the spine was obtained in a standardized fashion. The sacral slope, pelvic tilt, pelvic incidence, lumbar lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, T1 and T9 sagittal offset were measured using a computer-assisted method. The variations and reciprocal correlations of all parameters in both groups according to each other were studied. Comparison of angular parameters between OI patients and control group showed an increased T1T12 kyphosis in OI patients. T1 and T9 sagittal offset was positive in OI patients and negative in control group. This statistically significant difference among sagittal offsets in both groups indicated that OI patients had a global sagittal balance of the trunk displaced anteriorly when compared to the normal population. Reciprocal correlations between angular parameters in OI patients showed a strong correlation between lumbar lordosis (L1L5 and L1S1) and sacral slope. The T9 sagittal offset was also strongly correlated with pelvic tilt. Pelvic incidence was correlated with L1S1 lordosis, T1 sagittal offset and pelvic tilt. In OI patients, the T1T12 thoracic kyphosis was statistically higher than in control group and was not correlated with other shape (LL) or pelvic (SS, PT or PI) parameters. Because isolated T1T12 kyphosis increase without T4T12 significant modification, we suggest that vertebral deformations worsen in OI patients at the upper part of thoracic spine. Further studies are needed to precise the exact location of most frequent vertebral deformities.

Keywords: Osteogenesis imperfecta, Sagittal spinal balance, Thoracic kyphosis, Vertebral fracture, Osteoporosis

Introduction

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a congenital disease of collagen responsible for multiple skeletal abnormalities. In milder forms, the fracture rate is only slightly increased and the stature is normal or slightly decreased. In severe forms, bone softness and multiple fractures lead to progressive bone deformities with extreme shortness, frequent skeletal pain, and confinement to a wheelchair. In most cases, there are mutations in the COLIA1 or COLIA2 genes localized to chromosomes 17 and 7, respectively. This leads either to a reduced production of normal collagen type I, or to the synthesis of abnormal collagen type I. The current classification into four major subgroups (types I–IV), based on clinical findings, was proposed by Sillence et al. in 1979 [22–24].

Some relation between genotype and phenotype has been reported [25], but in general, the genotype is an unreliable predictor of phenotype and severity.

In OI patients, multiple compression fractures of the spine, as well as vertebral height shortening could be responsible for an increased thoracic kyphosis or a diminished lumbar lordosis [1, 2, 9, 20]. These progressive changes in sagittal shapes of the trunk could be responsible for a global sagittal trunk imbalance [19]. Differences in the anatomic development of the spine and the pelvis might cause individual variation in vertebropelvic alignment. Studies have confirmed that some structural features of the pelvis modulate and largely determine the amount of standing lumbar lordosis, as well as the sagittal pelvic alignment and spinopelvic balance [3, 5, 15, 27]. These relationships have been documented in adult volunteers [3–8, 27] and in patients with spinal disorders. The most important roentgenographic parameters of the sagittal balance of the spine in upright posture are well defined, and their normal physiological values have been reported [15, 27]. These stable relationships are disturbed in pathological conditions such as spondylolisthesis of neuromuscular disorders [26]. Few studies have addressed spinal disorders in OI patients [1, 2, 9, 19, 20]. The purpose of this work was to study the sagittal balance of the spine in OI patients. We compare the parameters of sagittal spinopelvic balance in young patients with OI to those parameters in a control group of healthy volunteers.

Materials and methods

Following Institutional Review Board approval, 18 OI patients who had been referred to our institution were enrolled in the study. Healthy volunteers were enrolled in a previously published study [27] on sagittal balance of the spine. Three hundred subjects volunteered and were accepted into the study. Inclusion criteria included: age between 20 and 70 years, no previous history of spinal disorders or spinal surgery, no radiographic abnormality detected prior or during the study (i.e. isthmic lysis, spondylolisthesis or spinal abnormality), no significant lower extremity joint pathology (i.e. hip, knee, ankle). Volunteers were informed of the risks and benefits of participating to the study and gave informed consent.

Radiographic protocol

For each patient, one standing lateral radiograph of the spine was obtained in a standardized fashion. The same protocol was used for radiographs of the control group subjects. A constant distance between the subject and the X-ray source was used, the subject assumed a comfortable standing position with the knees fully extended and upper limbs raised horizontally forward at 45° of flexion at the shoulder resting on two arm supports). The central ray was centered on the twelfth thoracic vertebra and the film was exposed during inspiration. The complete axial skeleton between the external auditory ducts and superior third of the femurs was visualized in these films.

All measurements were performed by means of the Spineview® software package (Surgiview, 64, rue Tiquetonne, 75002 Paris, France) which was validated in a previous study [21].

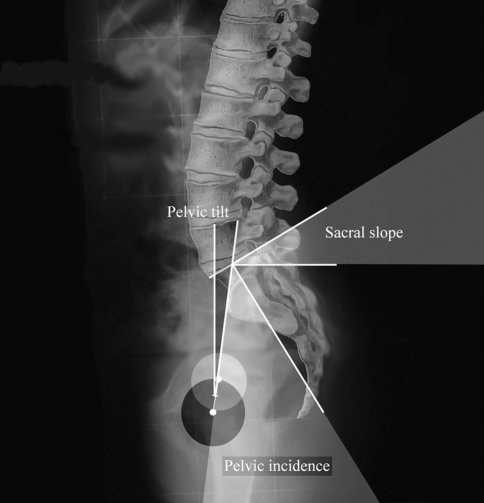

On each lateral radiograph, three pelvic parameters were measured (Fig. 1). The sacral slope (SS) is the angle between the horizontal line and the cranial sacral endplate tangent. The pelvic tilt (PT) is the angle between the vertical line and the line joining the middle of the sacral plate to the center of the bicoxo-femoral axis. The pelvic incidence (PI) is the angle between the line perpendicular to the middle of the cranial sacral endplate and the line joining the middle of the cranial sacral endplate to the center of the bicoxo-femoral axis.

Fig. 1.

Three spinopelvic paramters were measured: the Pelvic incidence (PI), the Sacral slope (SS) and the Pelvic tilt (PT)

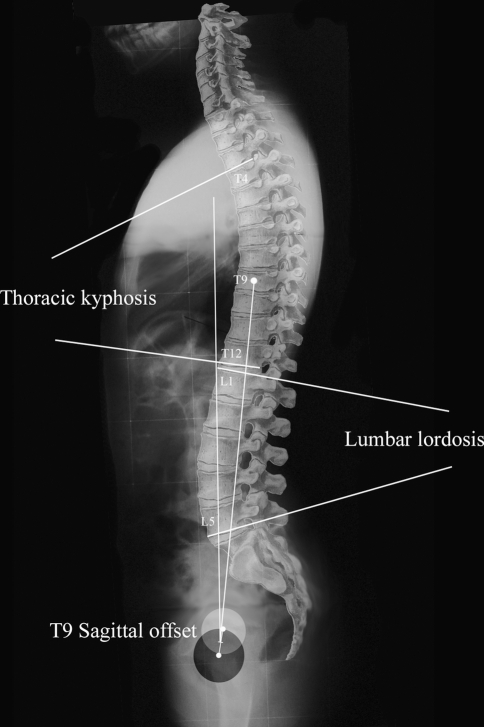

On each lateral radiograph, six spinal parameters were also measured (Fig. 2). The L1L5 lumbar lordosis is the angle between the cranial endplate of L1 and the caudal endplate of L5. The L1S1 lumbar lordosis is the angle between the cranial endplate of L1 and the cranial endplate of S1. The T4T12 thoracic kyphosis is the angle between the cranial endplate of T4 and the caudal endplate of T12. The T1T12 thoracic kyphosis is the angle between the cranial endplate of T1 and the caudal endplate of T12. The T9 sagittal offset is the angle between the vertical plumb line and the line between the center of the vertebral body of T9 and the center of the bicoxo-femoral axis. The T1 sagittal offset is the angle between the vertical plumb line and the line between the center of the vertebral body of T1 and the center of the bicoxo-femoral axis.

Fig. 2.

The Lumbar lordosis (LL) between L1 and L5, the Thoracic kyphosis (TK) between T4 and T12 and the T9 sagittal offset (T9SO) were measured

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by the use of the SPSS® software (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA).Our analysis was conducted in three steps. We first performed a descriptive analysis of the demographic and morphological parameters of the cohort. Second, we calculated the mean value, standard deviation, standard error and range of the angular parameters previously defined. Third, we studied variations and reciprocal correlations of all parameters in both groups according to each other using unpaired t test using correction to account for multiple testing.

Results

The main characteristics of the population (OI patients and control group) and the values of the angular parameters are reported in Tables 1 and 2. The distribution of each angular parameter was normal.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics in OI patients

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18.00 | 2.68 | 18.59 | 9.01 | 4.90 |

| T4T12 Kyphosis (degrees) | 18.00 | 21.14 | 54.72 | 36.96 | 9.08 |

| T1T12 Thoracic kyphosis (degrees) | 18.00 | 30.93 | 58.69 | 46.22 | 7.21 |

| L1L5 Lordosis (degrees) | 18.00 | −75.63 | −18.35 | −44.67 | 15.34 |

| L1S1 Lordosis (degrees) | 18.00 | −92.08 | −28.90 | −54.69 | 18.26 |

| T1 sagittal offset (degrees) | 15.00 | −7.77 | 8.91 | 2.20 | 4.91 |

| T9 sagittal offset (degrees) | 18.00 | −3.54 | 14.40 | 6.78 | 5.11 |

| Sacral slope (degrees) | 18.00 | 25.46 | 66.80 | 41.75 | 12.61 |

| Pelvic tilt (degrees) | 18.00 | 2.64 | 29.62 | 15.31 | 8.56 |

| Pelvic incidence (degrees) | 18.00 | 33.88 | 82.34 | 57.07 | 13.89 |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics in control group

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 300 | 18.70 | 70.00 | 35.37 | 12.13 |

| T4T12 Kyphosis (degrees) | 300 | 0.00 | 69.00 | 40.66 | 10.27 |

| T1T12 Kyphosis (degrees) | 300 | −3.70 | 65.99 | 41.24 | 10.08 |

| L1L5 Lordosis (degrees) | 300 | −69.20 | −13.56 | −43.14 | 11.21 |

| L1S1 Lordosis (degrees) | 300 | −89.23 | −30.00 | −60.25 | 10.31 |

| T1 sagittal offset (degrees) | 300 | −9.16 | 7.12 | −1.35 | 2.65 |

| T9 sagittal offset (degrees) | 300 | −19.80 | −1.72 | −10.35 | 3.06 |

| Sacral slope (degrees) | 300 | 16.90 | 63.55 | 41.86 | 8.38 |

| Pelvic tilt (degrees) | 300 | −4.47 | 27.17 | 13.21 | 6.10 |

| Pelvic incidence (degrees) | 300 | 33.23 | 81.80 | 54.68 | 10.66 |

Statistical study showed that OI patients were statistically younger than control patients (R = 9.16 with P < 0.0001). Comparison of angular parameters between OI patients and control group showed an increased T1T12 kyphosis in OI patients. T1 and T9 sagittal offset was positive in OI patients and negative in control group. This statistically significant difference among sagittal offsets in both groups indicated that OI patients had a global sagittal balance of the trunk displaced anteriorly compared to the normal population. The details of the statistical comparison between both group angular values are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Statistical comparison of angular parameters between both groups

| Group | N | Mean | SD | SE mean | t value | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Control | 300 | 35.37 | 12.13 | 0.70 | 9.16 | <0.0001 |

| OI | 18 | 9.01 | 4.90 | 1.16 | |||

| T4T12 Kyphosis (degrees) | Control | 300 | 40.66 | 10.27 | 0.59 | 1.67 | 0.11 |

| OI | 18 | 36.96 | 9.08 | 2.14 | |||

| Maximal thoracic kyphosis (degrees) | Control | 300 | 41.24 | 10.08 | 0.58 | −2.77 | 0.01 |

| OI | 18 | 46.22 | 7.21 | 1.70 | |||

| L1L5 Lordosis (degrees) | Control | 300 | −43.14 | 11.21 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.68 |

| OI | 18 | −44.67 | 15.34 | 3.61 | |||

| L1S1 Lordosis (degrees) | Control | 300 | −60.25 | 10.31 | 0.60 | −1.28 | 0.22 |

| OI | 18 | −54.69 | 18.26 | 4.30 | |||

| T1 sagittal offset (degrees) | Control | 300 | −1.35 | 2.65 | 0.15 | −4.82 | <0.0001 |

| OI | 15 | 2.20 | 4.91 | 1.27 | |||

| T9 sagittal offset (degrees) | Control | 300 | −10.35 | 3.06 | 0.18 | −22.06 | <0.0001 |

| OI | 18 | 6.78 | 5.11 | 1.20 | |||

| Sacral slope (degrees) | Control | 300 | 41.86 | 8.38 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.96 |

| OI | 18 | 41.75 | 12.61 | 2.97 | |||

| Pelvic tilt (degrees) | Control | 300 | 13.21 | 6.10 | 0.35 | −1.38 | 0.17 |

| OI | 18 | 15.31 | 8.56 | 2.02 | |||

| Pelvic incidence (degrees) | Control | 300 | 54.68 | 10.66 | 0.62 | −0.72 | 0.48 |

| OI | 18 | 57.07 | 13.89 | 3.27 |

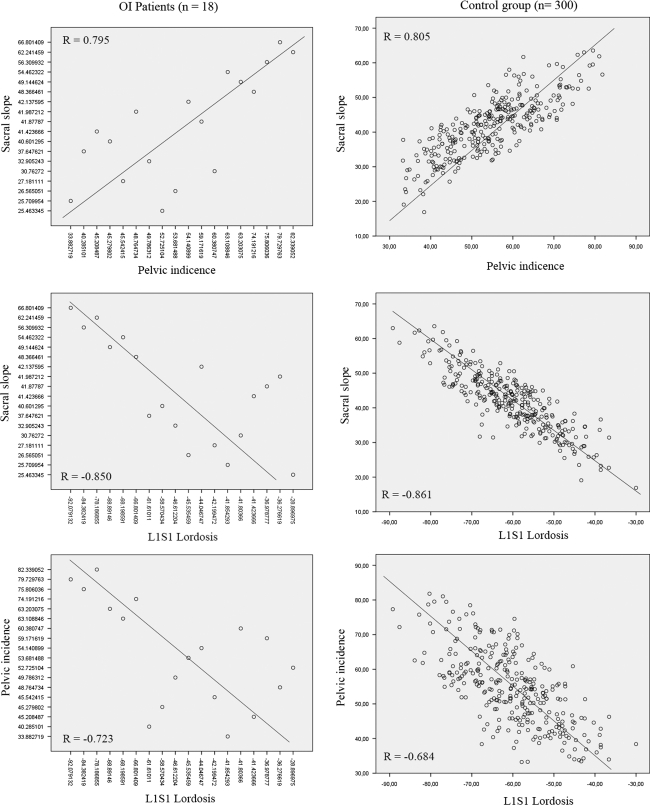

Reciprocal correlations between angular parameters in OI patients showed a strong correlation between lumbar lordosis (L1L5 and L1S1) and sacral slope. The T9 sagittal offset was also strong correlated with pelvic tilt. Pelvic incidence was correlated with L1S1 lordosis, T1 sagittal offset and pelvic tilt. The correlation matrix among all of the angular parameters in OI patients is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Reciprocal correlations between angular values in OI patients

| T4T12 Kyphosis (degrees) | Maximal thoracic kyphosis (degrees) | L1L5 Lordosis (degrees) | L1S1 Lordosis (degrees) | T1 sagittal offset (degrees) | T9 sagittal offset (degrees) | Sacral slope (degrees) | Pelvic version (degrees) | Pelvic incidence (degrees) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T4T12 Kyphosis (degrees) | Coefficient | 0.700 | −0.121 | −0.138 | −0.434 | 0.084 | 0.106 | 0.105 | 0.161 | |

| Significance | 0.001 | 0.633 | 0.584 | 0.106 | 0.739 | 0.675 | 0.678 | 0.523 | ||

| Maximal thoracic kyphosis (degrees) | Coefficient | −0.343 | −0.302 | −0.382 | 0.256 | 0.153 | −0.028 | 0.122 | ||

| Significance | 0.164 | 0.224 | 0.160 | 0.306 | 0.543 | 0.912 | 0.630 | |||

| L1L5 Lordosis (degrees) | Coefficient | 0.910 | −0.146 | −0.158 | −0.798 | 0.119 | −0.651 | |||

| Significance | <0.0001 | 0.603 | 0.531 | <0.0001 | 0.637 | 0.003 | ||||

| L1S1 Lordosis (degrees) | Coefficient | −0.222 | −0.179 | −0.850 | 0.080 | −0.723 | ||||

| Significance | 0.426 | 0.478 | 0.000 | 0.754 | 0.001 | |||||

| T1 sagittal offset (degrees) | Coefficient | 0.748 | −0.090 | −0.110 | −0.148 | |||||

| Significance | 0.001 | 0.748 | 0.697 | 0.597 | ||||||

| T9 sagittal offset (degrees) | Coefficient | −0.285 | 0.526 | 0.066 | ||||||

| Significance | 0.253 | 0.025 | 0.794 | |||||||

| Sacral slope (degrees) | Coefficient | −0.183 | 0.795 | |||||||

| Significance | 0.468 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Pelvic tilt (degrees) | Coefficient | 0.451 | ||||||||

| Significance | 0.060 | |||||||||

| Pelvic incidence (degrees) | Coefficient | |||||||||

| Significance | ||||||||||

Significant correlations are noted in bold font

In control group, we noted a very strong correlation between the thoracic kyphosis and the lumbar lordosis, the lumbar lordosis and T1 and T9 sagittal offsets and between the thoracic kyphosis and the sacral slope. The T9 sagittal offset was also strong correlated with pelvic tilt and sacral slope. Pelvic incidence was correlated with Thoracic kyphosis, sacral slope L1S1 lordosis and pelvic tilt but not with T1 sagittal offset. The correlation matrix among all of the angular parameters in control group is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Reciprocal correlations between angular values in control group

| T4T12 Kyphosis (degrees) | Maximal thoracic kyphosis (degrees) | L1L5 Lordosis (degrees) | L1S1 Lordosis (degrees) | T1 sagittal offset (degrees) | T9 sagittal offset (degrees) | Sacral slope (degrees) | Pelvic version (degrees) | Pelvic incidence (degrees) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T4T12 Kyphosis (degrees) | Coefficient | 0.810 | −0.228 | −0.156 | 0.063 | 0.021 | −0.747 | −0.219 | −0.670 | |

| Significance | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.007 | 0.280 | 0.720 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Maximal thoracic kyphosis (degrees) | Coefficient | −0.324 | −0.287 | 0.207 | 0.157 | 0.003 | −0.066 | −0.054 | ||

| Significance | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.007 | 0.959 | 0.256 | 0.351 | |||

| L1L5 Lordosis (degrees) | Coefficient | 0.955 | −0.062 | −0.410 | 0.060 | −0.062 | −0.005 | |||

| Significance | <0.0001 | 0.284 | <0.0001 | 0.302 | 0.282 | 0.928 | ||||

| L1S1 Lordosis (degrees) | Coefficient | −0.056 | −0.427 | −0.861 | −0.068 | −0.684 | ||||

| Significance | 0.333 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.244 | <0.0001 | |||||

| T1 sagittal offset (degrees) | Coefficient | 0.654 | 0.098 | 0.015 | 0.100 | |||||

| Significance | <0.0001 | 0.089 | 0.800 | 0.084 | ||||||

| T9 sagittal offset (degrees) | Coefficient | 0.214 | −0.369 | −0.045 | ||||||

| Significance | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.441 | |||||||

| Sacral slope (degrees) | Coefficient | 0.104 | 0.805 | |||||||

| Significance | 0.072 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Pelvic tilt (degrees) | Coefficient | 0.650 | ||||||||

| Significance | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Pelvic incidence (degrees) | Coefficient | |||||||||

| Significance | ||||||||||

Significant correlations are noted in bold font

Discussion

In a previous study, we proposed a physiological standard for several angular pelvic and spinal parameters that describe spinal balance based on measurements from a cohort of 300 volunteers [27]. Those measurements were facilitated by the use of data processing software, the Spineview® software package that enabled a rapid and precise measurement of all angular parameters on digitalized radiographs.

After studying sagital balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects, we found that it is necessary to explore the sagittal balance of the spine in patients with pathological conditions. Because, osteogenesis imperfecta could affect sagittal shapes of the spine due to multiple compression fractures or dystrophic changes of vertebral bodies, we postulate that such sagittal deformities could be responsible for regional modifications in spinopelvic balance.

The sagittal spinopelvic balance is poorly documented in normal pediatric subjects. The most recent studies showed that spinopelvic parameters were different from those reported in normal adults [17, 18]. However, the correlations between the parameters were similar. As in our control population, PI was significantly related to SS and PT and significant correlations were found between the parameters of adjacent anatomical regions. Because PI could be considered as an anatomical parameter, pelvic incidence regulates sagittal sacro-pelvic orientation (SS and PT). As demonstrated in recent studies in children and adults, sacral orientation (SS) is correlated with the shape (LL) and orientation (PT) of the lumbar spine. Adjacent anatomical regions of the spine and pelvis are interdependent, and their relationships result in a stable and compensated posture, presumably to minimize energy expenditure.

Relatively, little is known about the importance of spinopelvic parameters in human musculoskeletal disorders. An association between PI, SS and spondylolisthesis has been reported in recent publications [10–12, 18]. We demonstrated such interdependences in neuromuscular patients [26].

As Labelle et al. [11, 12], we fully recognize that there was a difference in age between our OI cohort and our asymptomatic volunteers used for comparison. Numerous authors showed that the PI gradually increases with age from the onset of walking to late childhood [11, 12, 16, 17]. Because of this progressive and “balanced” increase of the global sagittal spine, we believe that our findings and conclusion were little affected by this difference between pathological and control groups.

In OI patients, the T1T12 thoracic kyphosis was statistically higher than in control group and was not correlated with other shape (LL) or pelvic (SS, PT or PI) parameters. Because isolated T1T12 kyphosis increase without T4T12 significant modification, we suggest that vertebral deformations worsen in OI patients at the upper part of thoracic spine. Because in OI patients, LL was not able to balance this pathological condition, we noted a modification of the T1and T9 sagittal offsets, which were displaced anteriorly. At the lumbar and lombo-pelvic segments, reciprocal correlations remained close to normal conditions. Well-known correlations between PI, SS and LL were found in OI patients as in normal adults, adolescents and children (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Graphic representation of the relevant correlations between angular parameters in both (control and OI) groups

Fracture rate is difficult to assess without frequent X rays, which is not recommended for patients with OI, as the increased fracture rate can lead to high-accumulated doses of radiation over time. Land et al. [13, 14] proposed Pamidronate in moderate to severe forms of OI to treat or to prevent vertebral deformations. In these patients, bisphosphonate therapy should be started as early as possible to treat or to prevent vertebral deformations. Further studies are needed to precise the exact location of most frequent vertebral deformities. Segmental measurements of each vertebra, especially at the upper part of the thoracic spine, in a greater number of patients, are actually conducted in our institution to precise sagittal spine imbalance patterns in OI patients and define the most exposed parts of the spine to vertebral deformities. In a second time, long-term modifications of spinopelvic balance need to be assessed in patients undergoing bisphosphonate therapy. These patients need to be followed-up and investigated after the end of the growth period to precise the effects of bisphosphonate therapy on the final shape of the spine and spinopelvic compensation phenomenon.

Acknowledgments

This study profited from the financial support of the “Association de l’Ostéogenèse Imparfaite (AOI)”.

References

- 1.Benson DR, Donaldson DH, Millar EA. The spine in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:925–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson DR, Newman DC. The spine and surgical treatment in osteogenesis imperfecta. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;159:147–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.During J, Goudfrooij H, Keessen W, et al. Toward standards for posture. Postural characteristics of the lower back system in normal and pathologic conditions. Spine. 1985;10:83–87. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198501000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duval-Beaupere G, Robain G. Visualization on full spine radiographs of the anatomical connections of the centres of the segmental body mass supported by each vertebra and measured in vivo. Int Orthop. 1987;11:261–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00271459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duval-Beaupere G, Schmidt C, Cosson P. A Barycentremetric study of the sagittal shape of spine and pelvis: the conditions required for an economic standing position. Ann Biomed Eng. 1992;20:451–462. doi: 10.1007/BF02368136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelb DE, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, et al. An analysis of sagittal spinal alignment in 100 asymptomatic middle and older aged volunteers. Spine. 1995;20:1351–1358. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199506000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guigui P, Levassor N, Rillardon L, et al. Physiological value of pelvic and spinal parameters of sagital balance: analysis of 250 healthy volunteers. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2003;89:496–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammerberg EM, Wood KB. Sagittal profile of the elderly. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:44–50. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanscom DA, Bloom BA. The spine in osteogenesis imperfecta. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:449–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson RP, Phipps T, Hales C, et al. Pelvic lordosis and alignment in spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2003;28:151–160. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labelle H, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud E, et al. The importance of spino-pelvic balance in L5–s1 developmental spondylolisthesis: a review of pertinent radiologic measurements. Spine. 2005;30:S27–S34. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000155560.92580.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labelle H, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud E, et al. Spondylolisthesis, pelvic incidence, and spinopelvic balance: a correlation study. Spine. 2004;29:2049–2054. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000138279.53439.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Land C, Rauch F, Munns CF, et al. Vertebral morphometry in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta: effect of intravenous pamidronate treatment. Bone. 2006;39:901–906. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Land C, Rauch F, Travers R, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta type VI in childhood and adolescence: effects of cyclical intravenous pamidronate treatment. Bone. 2007;40:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legaye J, Duval-Beaupere G, Hecquet J, et al. Pelvic incidence: a fundamental pelvic parameter for three-dimensional regulation of spinal sagittal curves. Eur Spine J. 1998;7:99–103. doi: 10.1007/s005860050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mac-Thiong JM, Labelle H, Berthonnaud E, et al. Sagittal spinopelvic balance in normal children and adolescents. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:227–234. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0013-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangione P, Gomez D, Senegas J. Study of the course of the incidence angle during growth. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:163–167. doi: 10.1007/BF01301430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marty C, Boisaubert B, Descamps H, et al. The sagittal anatomy of the sacrum among young adults, infants, and spondylolisthesis patients. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:119–125. doi: 10.1007/s00586-001-0349-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oppenheim WL. The spine in osteogenesis imperfecta: a review of treatment. Connect Tissue Res. 1995;31:S59–S63. doi: 10.3109/03008209509116836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao S, Patel A, Schildhauer T. Osteogenesis imperfecta as a differential diagnosis of pathologic burst fractures of the spine. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;289:113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rillardon L, Levassor N, Guigui P, et al. Validation of a tool to measure pelvic and spinal parameters of sagittal balance. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2003;89:218–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sillence DO, Rimoin DL. Classification of osteogenesis imperfect. Lancet. 1978;1:1041–1042. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90763-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sillence DO, Rimoin DL, Danks DM. Clinical variability in osteogenesis imperfecta-variable expressivity or genetic heterogeneity. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1979;15:113–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sillence DO, Senn A, Danks DM. Genetic heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet. 1979;16:101–116. doi: 10.1136/jmg.16.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith R. Osteogenesis imperfecta: from phenotype to genotype and back again. Int J Exp Pathol. 1994;75:233–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vialle R, Khouri N, Glorion C, et al. Lumbar hyperlordosis of neuromuscular origin: pathophysiology and surgical strategy for correction. Int Orthop. 2007;31:513–523. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, et al. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:260–267. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]