Abstract

Aim of this prospective randomized trial was to analyze the effectiveness of MESNA in chemical dissection of peridural fibrosis in patients who underwent revision lumbar spine surgery. Between January 2003 and October 2006, 30 patients who underwent revision lumbar spine surgery were enrolled in the study. Patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups: a study group (A) and a control group (B). Once peridural fibrosis was exposed, MESNA (Uromixetan MESNA, 50 mg/ml) was intraoperatively applied on the fibrous tissue (Group A) to ease tissue dissection and enter the canal. In patients of Group B, saline solution was used. Surgical time, preoperative and 1 week postoperative hemoglobin (Hb), length of hospitalization (days), and incidence of perioperative complications were evaluated. The blinded surgeon assigned the surgeries to one of four categories as none, minimal, moderate, and severe basing on intraoperative difficulty in dissecting the fibrous tissue and intraoperative bleeding. Statistical analysis used chi-square analysis to evaluate the difference in surgery difficulty and the incidence of intraoperative complications between the two groups. The analysis of surgical time and hemoglobin levels was performed using a one-sample Wilcoxon test and Mann–Whitney U test. Patients in whom MESNA was used intraoperatively (Group A) presented better intraoperative and perioperative parameters with respect to the control group. Average surgical time and decrease in Hb postoperatively were more in the saline group (B) respect to MESNA (A) (P = 0.004 and P = 0.001, respectively), while no difference in average hospital stay was reported between the two groups. Surgeon-blinded intraoperative report on surgical difficulty showed a significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.05). Postoperatively, no complications directly attributable to the use of MESNA were experienced. The incidence of dural tears and intraoperative bleeding from epidural veins were significantly less in Group A with respect to the control group. MESNA contributed significantly to reduce the operative complications, with a diminution of the surgical time and the grade of difficult for the surgeon, confirming its ability as chemical dissector also for epidural fibrosis in revision lumbar spine surgery.

Keywords: Epidural fibrosis, Revision surgery, Lumbar spine, MESNA, Chemical dissection

Introduction

Revision lumbar spine surgery is challenging, with high incidence of intraoperative complications and elevated economical costs, due to the complexity of surgery and its duration [12, 16, 26]. One of the most challenging problems during revision lumbar spine surgery is the presence of epidural fibrosis that occurs as regeneration process after a previous surgery [14, 26].

Postoperative epidural fibrosis is a dense scar tissue that originates from the residual lamines and from the deep surface of the paravertebral muscles, and it may extend into the neural canal and adhere to the dura mater and nerve roots [1, 18]. The presence of epidural fibrosis during lumbar revision surgery makes difficult surgical dissection into the spinal canal [1], with increased intraoperative complications (increased occurrence of dural tears, lesions to spinal nerves, and local bleeding) [1, 17, 22]. Fibrosis has been also suggested to be one of the main factors responsible for poor clinical outcome in patients undergoing lumbar surgery [1, 26], thus contributing to the so-called “failed back syndrome,” due to mechanical adherences of the fibrosis to the dura mater and nerve roots with following ischemia [1, 6, 10, 13, 18, 22].

MESNA (Uromixetan) (sodium 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate) is a clear liquid mucolythic agent whose ability in fast dissolve connections between tissues has been already proved [5, 7]. MESNA has been validated as a local adjuvant in chemical-assisted dissection in surgery for endometrial cysts [4], abdominal myomectomies [5], and in surgical excision of cholesteatoma matrix, in which neural and bony structures are in contact [24].

Aim of this prospective randomized trial was to analyze the effectiveness of MESNA in chemical dissection of peridural fibrosis in patients who underwent revision lumbar spine surgery. We hypothesize that instillation of MESNA would facilitate highlighting of the cleavage planes and dissect surgical planes.

Materials and methods

Between January 2003 and October 2006, 30 patients who underwent revision lumbar spine surgery were enrolled in the study. All the surgeries comprehended a surgical step in the spinal canal (i.e., recurrent disc herniation removal, etc). Patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups: a study group (A) and a control group (B). Each group consisted of 15 patients.

Preoperative diagnosis was disc degeneration at the level above or below a previous fusion (A = 7; B = 8), recurrent disc herniation (A = 3; B = 3), symptomatic periradicular fibrosis, as confirmed by preoperative contrast enhanced spinal MRI (A = 5; B = 4). In all patients, surgery consisted of a revision at the previously operated level by performing a complete unilateral dissection of fibrosis from the dural tissue and nerve roots. Instrumented fusion via a posterior approach was performed in all patients.

The study was performed accordingly to ethical standard of Helsinki declaration (1975; revised in 1983). All the patients were aware that they were participating in the study and signed an informed consent.

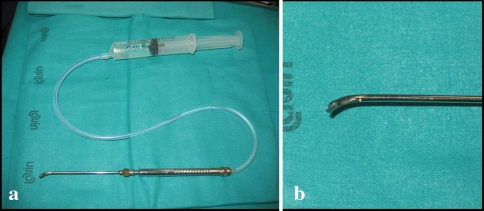

All surgeries were performed by the same surgeon (VD). Once peridural fibrosis was exposed, MESNA (Uromitexan MESNA, 50 mg/ml) was intraoperatively applied on the fibrous tissue (Group A) to ease tissue dissection and enter the canal. A modified dissector was used to release the drug locally (Fig. 1) when needed. No scissors were used, but only blunt dissectors to divide the surgical planes. In patients of Group B, the same instrument was used, but with saline solution. Surgeon was unaware of the content of the solution used, provided that MESNA is a transparent odorless liquid, impossible to differentiate intraoperatively from saline solution. Duration of local application was about 20–30 s; repeated applications could occur during surgery. Average volume of agent used per each surgery was 10 cc maximum.

Fig. 1.

a A modified dissector was used to release the drug locally. b High magnitude particular of the tip of the dissector showing the hole for drug release

In both groups, the following variables were studied: surgical time, preoperative and 1 week postoperative hemoglobin (Hb), length of hospitalization (days), and incidence of perioperative complications; moreover, the surgeon assigned the surgeries to one of four categories as none, minimal, moderate, and severe basing on intraoperative difficulty in dissecting the fibrous tissue and intraoperative bleeding [5].

Statistical analysis used chi-square analysis to evaluate the difference in surgery difficulty and the incidence of intraoperative complications between the two groups. The analysis of surgical time and hemoglobin levels was performed using a one-sample Wilcoxon test and Mann–Whitney U test. Differences were considered significant for P < 0.05.

Results

The two groups of patients presented similar characteristics as regards age (42 years for Group A vs. 40 for Group B), male to female distribution (Group A: M = 9; F = 6; Group B: M = 10; F = 5), and number of operative levels (19 for Group A and 18 for Group B). Average time from first surgery to revision was 35 months (range 28–43 months) in Group A and 37 months (range 25–45 months) in Group B.

The analysis of efficacy and utility of MESNA was performed using objective as well as surgeon-related parameters found in the two groups (A and B): patients in which MESNA was used intraoperatively (Group A) presented better intraoperative and perioperative parameters with respect to the control group.

Average surgical time and decrease in Hb postoperatively were more in the saline group (B) with respect to MESNA (A) (P = 0.004 and P = 0.001, respectively), while no difference in average hospital stay was reported between the two groups (Table 1). Surgeon-blinded intraoperative report on surgical difficulty (Table 2) showed a significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.05). Postoperatively, no complications directly attributable to the use of MESNA were experienced. The incidence of dural tears and intraoperative bleeding from epidural veins were significantly less in Group A with respect to the control group (Table 3).

Table 1.

Study variables of the study group (A) and the control group (B)

| Study variables | A (n = 15) | B (n = 15) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical time (min) | 125 ± 23 | 156 ± 18 | S |

| Hb (preoperative–postoperative at 1 week) | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | S |

| Average hospital stay | 6.8 ± 0.3 | 7.1 ± 0.4 | NS |

S significant, NS nonsignificant

Table 2.

Surgical difficulty of the study group (A) and the control group (B)

| Surgical difficulty | A (n = 15) | B (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|

| Severe | 2 | 5 |

| Moderate | 5 | 6 |

| Minimal | 6 | 3 |

| None | 2 | 2 |

Table 3.

Complications of the study group (A) and the control group (B)

| Complications | A (n = 15) | B (n = 15) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dural tears | 1 | 4 | S |

| Bleeding from epidural veins | 2 | 6 | S |

| DVT | 1 | 1 | NS |

| Epifascial infection | 1 | 1 | NS |

| Unusual postoperative pain | 2 | 2 | NS |

S significant, NS nonsignificant

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial to analyze the effectiveness of MESNA in chemical dissection of peridural fibrosis in patients who underwent revision lumbar spine surgery. We compared the instillation of MESNA and saline solution in facilitating highlighting of the cleavage planes and dissect surgical planes. In our hands, the use of MESNA in revision lumbar spine surgery is related with a reduced occurrence of intraoperative and postoperative complications, and with a diminution of surgical time. Moreover, the grade of difficulty for the surgeon (in blind) was less when MESNA was used during surgery, confirming its ability in chemical dissection of tissues, even at epidural level (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Axial (a) and sagittal (b) MRI images in a patient with disc herniation with extrusion and segmental instability 38 months after primary surgery. There is epidural fibrosis (black arrow). Axial (c) and sagittal (d) preoperative CT images. The primary surgery consisted of L4–L5 discectomy with a partial laminectomy of L4 (white arrow). e Intraoperative picture showing a modified dissector used to release the drug locally (black arrow). f Intraoperative picture. h Postoperative radiographs

Major strengths of the present study are its prospective nature, and that a single fully trained surgeon performed all the operation using a well established technique. We are fully aware of the limitations of this study. The small size of our population precludes definitive conclusions. However, the two groups of patients are homogenous and the analyzed parameters are coherent with the surgical results. We acknowledge that we did not perform a formal power analysis: we planned the choice of the number of patients to enrol in the study according to what we knew our unit could deliver within the time, which we chose to allocate to the study. However, despite this partial weakness of the present investigation, our selection and recruitment process and our assessment criteria were extremely rigorous, and performed in strict scientific fashion. Also, with the number of patients enrolled, the results of our study are univocal.

It is difficult to compare the findings of the present study with those of previous reports, as we know of no other prospective studies performed to evaluate the ability of MESNA in facilitating highlighting of the cleavage planes and dissect surgical planes in revision lumbar spine surgery.

Lumbar revision surgery represents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for the surgeon [6, 23], with less predictable results than primary surgery and increased risk of intraoperative complications [19]. The percentage of patients undergoing a revision lumbar surgery ranges from 5 to 33% [2, 8, 9, 12, 16, 19–21, 26] and varies widely across geographic regions [2, 3] and kind of surgery [2, 3].

In a report on 6,376 patients, reoperation rates over the 5-year period were significantly greater for patients who underwent fusion than for patients who underwent nonfusion surgery (18.2 vs. 14.6%, respectively) [16]. In another study on 272 patients, reoperation rates over a 2-year period were of 4.1% in patients subjected to laminectomy alone, of 10.8% in patients who underwent noninstrumented fusion, and 9.8% in laminectomy and instrumented fusion patients [12].

Complications during revision lumbar surgery are more frequent with spinal fusion than with laminectomy or discectomy alone, because of wider surgical exposure, more extensive dissection, and longer operative time [16]. Three conditions can be found intraoperatively: (1) nerves and dura mater compression, (2) fibrosis and adhesive arachnoiditis, and (3) segmental instability [21]. Between these, fibrosis is more commonly associated to intraoperative complications, above all dural tears following the attempt to dissect the fibrotic scar [21].

The presence of epidural fibrosis makes more difficult to highlight and separate cleavage planes during revision lumbar surgery [1]. It is evident after the first intervention with a rate of 44%, and is not a problem only for revision surgery, but also for patients who need second intervention [8].

The formation of epidural fibrosis is the result of the invasion of the postoperative hematoma by dense fibrotic tissue originating from the fibrous layer of the periosteum and within the deep surface of the paravertebral musculature and may extend into the neural canal [1, 18].

It has been proposed that the mechanical tethering of nerve roots or the dura by the epidural adhesions may be a contributing factor for an increased tension on the neural structures during the movement, with subsequent neural injury [1, 9, 22]. The intraoperative complications during revision surgery are bleeding from the epidural veins, dural and nerve root tears [8].

Dural tears are the most commonly reported complications in lumbar spine surgery, ranging from 1 to 17% [8, 11, 15, 25], mostly during revision surgery [25]. In our casuistic a higher incidence of dural tears with respect to literature reports was observed in patients enrolled in Group B. Nonetheless, differently from literature reports, patients were included in our study only if a surgical time in the canal at the index level was required to perform complete dissection of fibrosis from the dural tissue and nerve roots, maybe explaining this atypical result.

MESNA is a mucolythic agent that leads to the breaking of disulfide bonds of the mucus polypeptide chains [5]. Many experimental and clinical studies have been performed to evaluate tolerability and toxicity of the drug, and to establish that MESNA administration intravenously is rarely related to side effects (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, allergic reactions, hypertension) [5].

To date, MESNA has been mainly used in the treatment of respiratory diseases, to ease expectoration and avoid complications associated to bronchial occlusion after surgical interventions [18]. In oncology, MESNA is commonly used as an uroprotective agent to prevent urinary tract toxicity due to oxazaphosphorine derivative administration (e.g., ifosfamide, cyclophosphamide) [5].

In an experimental study on Achilles tendons, it has been demonstrated that MESNA acts by separating the collagen fibers, probably breaking the disulfide bonds of the mucus polypeptide chains [7]. Moreover, the drug has been used as a chemical dissector to highlight the cleavage planes during excision of endometrial cysts [4], abdominal myomectomies [5], and surgical treatment of cholesteatoma [24].

MESNA appears to be helpful in detaching the cholesteatoma matrix from the surrounding tissues, especially in the following conditions: infiltrating cholesteatoma, treatment of labyrinthine fistula, matrix on a mobile stapes superstructure, and matrix on exposed facial nerve or dura mater, without local side effects [24]. Based on these findings and on the low toxicity when in contact with neural structures, we proposed to use MESNA in revision lumbar surgery to highlight the cleavage planes. In our hands, MESNA contributed significantly to reduce the operative complications, with a diminution of the surgical time and the grade of difficult for the surgeon, confirming its ability as chemical dissector also for epidural fibrosis in revision lumbar spine surgery.

References

- 1.Alkalay RN, Kim DH, Urry DW, Xu J, Parker TM, Glazer PA. Prevention of postlaminectomy epidural fibrosis using bioelastic materials. Spine. 2003;1(28):1659–1665. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200308010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Wu YA, Deyo RA, Singer DE. Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of sciatica secondary to a lumbar disc herniation: 10 year results from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine. 2005;30(8):927–935. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158954.68522.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Wu YA, Deyo RA, Singer DE. Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis: 8 to 10 year results from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine. 2005;30(8):936–943. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158953.57966.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benassi L, Benassi G, Kaihura CT, Marconi L, Ricci L, Vadora E. Chemically assisted dissection of tissues in laparoscopic excision of endometriotic cysts. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(2):205–209. doi: 10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benassi L, Lopopolo G, Pazzoni F, Ricci L, Kaihura C, Piazza F, et al. Chemically assisted dissection of tissues: an interesting support in abdominal myomectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191(1):65–69. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(00)00296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabukoglu C, Guven O, Yildirim Y, Kara H, Ramadan SS. Effect of sagittal plane deformity of the lumbar spine on epidural fibrosis formation after laminectomy: an experimental study in the rat. Spine. 2004;29(20):2242–2247. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000142432.80390.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denaro V, Forriol F, Di Martino A, Denaro L, Papalia R, Caione G. Effect of a mucolytic agent on collagen fibres: an optical and polarized light histological study. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2001;11:209–212. doi: 10.1007/BF01686890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritsch EW, Heisel J, Rupp S. The failed back surgery syndrome: reasons, intraoperative findings, and long-term results: a report of 182 operative treatments. Spine. 1996;21(5):626–633. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199603010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geisler FH. Prevention of peridural fibrosis: current methodologies. Neurol Res. 1999;21(Suppl 1):S9–S22. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1999.11741021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson R, Weir B, Davis L, Mielke B, Grace M. Attempted experimental modification of the postlaminectomy membrane by local instillation of recombinant tissue-plasminogen activator gel. Spine. 1993;18(10):1268–1272. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hieb LD, Stevens DL. Spontaneous postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leaks following application of anti-adhesion barrier gel: case report and review of the literature. Spine. 2001;26(7):748–751. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200104010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Larson MG, McInnes JM, Fossel AH, Liang MH. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(6):809–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemaloglu S, Ozkan U, Yilmaz F, Nas K, Gur A, Acemoglu H, et al. Prevention of spinal epidural fibrosis by recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in rats. Spinal Cord. 2003;41(8):427–431. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitano T, Zerwekh JE, Edwards ML, Usui Y, Allen M. Viscous carboxymethylcellulose in the prevention of epidural scar formation. Spine. 1991;16(7):820–823. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199107000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le AX, Rogers DE, Dawson EG, Kropf MA, Grange DA, Delamarter RB. Unrecognized durotomy after lumbar discectomy: a report of four cases associated with the use of ADCON-L. Spine. 2001;26(1):115–117. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malter AD, McNeney B, Loeser JD, Deyo RA. 5-year reoperation rates after different types of lumbar spine surgery. Spine. 1998;23(7):814–820. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199804010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massie JB, Huang B, Malkmus S, Yaksh TL, Kim CW, Garfin SR, et al. A preclinical post laminectomy rat model mimics the human post laminectomy syndrome. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;137(2):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikawa Y, Hamagami H, Shikata J, Higashi S, Yamamuro T, Hyon SH, et al. An experimental study on prevention of postlaminectomy scar formation by the use of new materials. Spine. 1986;11(8):843–846. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198610000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan-Hough CV, Jones PW, Eisenstein SM. Primary and revision lumbar discectomy. A 16-year review from one centre. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(6):871–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osterman H, Sund R, Seitsalo S, Keskimaki I. Risk of multiple reoperations after lumbar discectomy: a population-based study. Spine. 2003;28(6):621–627. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200303150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozgen S, Naderi S, Ozek MM, Pamir MN. Findings and outcome of revision lumbar disc surgery. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12(4):287–292. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodgers KE, Robertson JT, Espinoza T, Oppelt W, Cortese S, diZerega GS, et al. Reduction of epidural fibrosis in lumbar surgery with Oxiplex adhesion barriers of carboxymethylcellulose and polyethylene oxide. Spine J. 2003;3(4):277–283. doi: 10.1016/S1529-9430(03)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart G, Sachs BL. Patient outcomes after reoperation on the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(5):706–711. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199605000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vincenti V, Mondain M, Pasanisi E, Piazza F, Puel JL, Bacciu S, et al. Cochlear effects of mesna application into the middle ear. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;28(884):425–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JC, Bohlman HH, Riew KD. Dural tears secondary to operations on the lumbar spine. Management and results after a two-year-min imum follow-up of eighty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;12:1728–1732. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199812000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng F, Cammisa FP, Jr, Sandhu HS, Girardi FP, Khan SN. Factors predicting hospital stay, operative time, blood loss, and transfusion in patients undergoing revision posterior lumbar spine decompression, fusion, and segmental instrumentation. Spine. 2002;27(8):818–824. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200204150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]