Abstract

Nicotine self-administration causes adaptation in the mesocorticolimbic glutamatergic system, including the up-regulation of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits. We therefore determined the effects of nicotine self-administration and extinction on NMDA-induced glutamate neurotransmission between the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and ventral tegmental area (VTA). On day 19 of nicotine SA, both regions were microdialyzed for glutamate while mPFC was sequentially perfused with Kreb’s Ringer buffer (KRB), 200 μM NMDA, KRB, 500 μM NMDA, KRB, and 100 mM KCl. Basal glutamate levels were unaffected, but nicotine self-administration significantly potentiated mPFC glutamate release to 200 μM NMDA, which was ineffective in controls. Furthermore, in VTA, nicotine self-administration significantly amplified glutamate responses to both mPFC infusions of NMDA. This hyper-responsive glutamate neurotransmission and enhanced glutamate subunit expression were reversed by extinction. Behavioral studies also showed that a microinjection of 2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (NMDA-R antagonist) into mPFC did not affect nicotine or sucrose self-administration. However, in VTA, NBQX (AMPA-R antagonist) attenuated both nicotine and sucrose self-administration. Collectively, these studies indicate that mesocortical glutamate neurotransmission adapts to chronic nicotine self-administration and VTA AMPA-R may be involved in the maintenance of nicotine self-administration.

Keywords: GABA, glutamate, in vivo microdialysis, medial prefrontal cortex, ventral tegmental area

Drug abuse is associated with molecular and cellular neuroadaptation within the mesocorticolimbic system (Koob 1992; Nestler 1992; Hyman et al. 2006). This system includes the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which provides the primary glutamatergic excitatory input to subcortical areas, such as the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and ventral tegmental area (VTA), and the VTA whose dopaminergic efferents regulate NAcc medium spiny neurons and mPFC pyramidal neurons (Sesack and Pickel 1992; Taber et al. 1995; Omelchenko and Sesack 2007). mPFC is instrumental to many dimensions of drug abuse including the expression of behavioral sensitization to psychostimulants (Wolf et al. 1995; Li et al. 1999a; Li and Wolf 1997; Li et al. 1999b) and drug-primed reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior (McFarland et al. 2003). Within the mPFC and VTA, the glutamatergic neurotransmission adapts to nicotine, reflecting changes in the expression and function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) (Mansvelder and McGehee 2000, 2002; Saal et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2007).

Nicotine activates VTA nAChRs that stimulate dopamine (DA) release in the NAcc, which is essential for nicotine self-administration (SA) (Corrigall et al. 1992). Glutamatergic efferents from mPFC have an important role in the regulation of NAcc DA levels (Sesack and Pickel 1992; Taber et al. 1995). For example, blockade of ionotropic glutamate receptors in the VTA decreased basal NAcc DA level by 30% and blocked DA release evoked by mPFC stimulation (Taber et al. 1995). Recent studies indicate that these neurochemical changes may be mediated by a polysynaptic glutamatergic pathway from mPFC that probably innervates the lateral dorsal tegmental nucleus (LDTg) and pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPTg), which in turn projects glutamatergic fibers to VTA mesoaccumbens DA neurons (Taber et al. 1995; Carr and Sesack 2000; Omelchenko and Sesack 2005). In addition, mPFC pyramidal neurons selectively innervate VTA mesocortical DA neurons (Carr and Sesack 2000), which in turn affect pyramidal neuron activity (Harte and O’Connor 2004). Thus, the activation of both polysynaptic and monosynaptic glutamatergic pathways, which originate in mPFC, appears to regulate VTA glutamate levels. The polysynaptic pathway that includes the PPTg appears to be involved in nicotine SA (Corrigall et al. 2001).

We have reported that chronic nicotine SA selectively up-regulated ionotropic glutamate receptors in the mPFC and VTA (Wang et al. 2007). However, the functional significance of this finding is not known. Herein, we hypothesize that during chronic nicotine SA glutamate neurotransmission is enhanced between mPFC and VTA, where the most significant receptor changes were found. To test this, we first determined the effects of mPFC NMDA on glutamate neurotransmission by using dual probe microdialysis to measure extracellular glutamate levels in both mPFC and VTA. We then determined the effects of extinction from nicotine SA. The effects of mPFC NMDA on glutamate neurotransmission and the expression of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits were determined after 10 days of extinction from chronic nicotine SA. Lastly, behavioral studies were conducted to assess the potential roles of the up-regulated mPFC and VTA ionotropic glutamate receptors in the maintenance of nicotine SA. The NMDA or AMPA receptor antagonists, 2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP-5) or 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-nitro-2,3-dioxo-benzo[f]qui-noxaline-7-sulfonamide (NBQX), were microdialyzed into these respective regions and lever press behavior was measured in rats that chronically self-administered nicotine compared to sucrose pellets.

Materials and methods

Materials

(−)-Nicotine hydrogen tartarate (doses expressed as free base), AP-5 and NBQX were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Sodium dihydrogen phosphate monohydrate, EDTA, methanol, and phosphoric acid were obtained from Fisher Scientific Co. (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Cellulose fiber tubing was purchased from Spectrum (Laguna Hills, CA, USA), and silica tubing (outer diameter, 148 μm; inner diameter, 73 μm; TSP 075150) was obtained from Polymicron Technologies Inc. (Phoenix, AZ, USA). Operant chambers, circuit boards, interface modules and SA software for chronic nicotine SA and sucrose SA were purchased from Coulbourn Instruments (Allentown, PA, USA) and Med Associates Inc. (Georgia, VT, USA), respectively.

Animals and surgeries

Adult male Lewis rats (250–270 g, Harlan, Madison, WI, USA) were given access ad libitum to standard rat chow and water. Rats were individually housed on a 12-h reversed light cycle (off at 9 AM, on at 9 PM). After 7 days of housing under these conditions, rats were anesthetized with xylazine-ketamine (13 and 87 mg/kg b.wt., i.m.; Sigma–Aldrich), and chronic guide cannulae (20-gauge) were stereotaxically implanted into the ipsilateral mPFC and VTA for the in vivo microdialysis experiment. For microinjection experiments, 26-gauge cannulae were stereotaxically implanted bilaterally into mPFC or VTA. Coordinates from bregma with flat skull were as follows: mPFC, AP +3.0 mm, DV −3.0 mm, ML +0.6 mm; VTA, AP −5.95 mm, DV −7.3 mm, ML +0.9 mm according to Paxinos and Watson (1986). Three to five days thereafter, the jugular vein was cannulated under xylazine-ketamine. Animals recovered for 3 days before nicotine SA began, while animals used in the sucrose SA experiment recovered for 7 days after stereotaxic surgery before the onset of sucrose SA training. All procedures were conducted in accordance with NIH Guidelines concerning the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Procedures for chronic nicotine SA and extinction followed by microdialysis

Nicotine SA was performed according to our protocols published previously (Valentine et al. 1997; Wang et al. 2007). Briefly, immediately following jugular vein surgery, awaken animals were placed into operant chambers where they resided for the duration of the study. After a 3 days recovery interval, rats were randomly assigned to treatment groups and jugular lines were filled with either 1 mM nicotine in 200 U/mL heparinized saline or heparin saline alone. The operant chamber contained two levers positioned 5 cm above the floor; a green cue light 1 cm above each lever signaled the availability of nicotine. One lever was randomly assigned as the active lever, which triggered the pump to deliver one 50 μL bolus injection of nicotine over 0.81 s per 300 g body weight (0.03 mg/kg) or saline; pressing the inactive lever had no consequence. Without prior training, shaping or food deprivation, rats were allowed to acquire and maintain SA behavior throughout consecutive 23 h sessions for 18 days, and a microdialysis experiment began on day 19. Specifically, the animals were removed from their operant chamber at 9 AM and transferred to the microdialysis apparatus approximately 3 h before the first baseline sample was collected.

A second microdialysis experiment was conducted after 10 days of extinction from nicotine SA. In this study, after 18 days of nicotine SA, the 10 days extinction phase was initiated; pressing the active lever had no programmed consequence and the cue lights were not illuminated. On day 11 of extinction, a microdialysis experiment was performed on a group of rats that were naïve to microdialysis.

To assess the efficacy of administering AP-5 into the mPFC, a third microdialysis study was performed. Animals were randomly assigned to two groups in which either NMDA alone or AP-5 and NMDA (volumes and rates of delivery as previously defined) was microinjected into mPFC. Beginning 10 min thereafter, VTA microdialysates were collected at 20 min intervals for the measurements of glutamate.

In vivo microdialysis procedure

Concentric microdialysis probes (1.5 mm for VTA, 2.0 mm for mPFC; MW cutoff 13 000 Da, outer diameter 235 μm) were constructed in our laboratory, as reported previously (Fu et al. 2000). The recovery efficiencies for glutamate by 1.5 mm and 2.0 mm probes were 4.7 ± 0.5% (n = 4) and 7.5 ± 0.6% (n = 5), respectively, and for GABA by 1.5 mm and 2.0 mm probes were 6.6 ± 0.6% (n = 3) and 8.7 ± 0.4% (n = 3), respectively. Microdialysis was performed as described previously (Fu et al. 2000). Briefly, on day 19 at 9:00 AM during their active (dark) phase, rats were moved into the alert-rat microdialysis chambers (CMA, Chelmsford, MA, USA) located within a dark isolation room, lit by a red safe-light; microdialysis probes were inserted into both mPFC and VTA guide cannulae. Following insertion, probes were perfused (2 μL/min) with KRB (147 mM NaCl, 4.0 mM KCl, and 3.4 mM CaCl2 in polished water; 0.2 μm filter sterilized and degassed) for 2 h. Thereafter, 20-min microdialysate samples were collected into plastic vials; three consecutive samples were collected to measure basal glutamate and GABA levels prior to drug administration. mPFC was sequentially perfused with the following solutions, each for 1 h: KRB, 200 μM NMDA, KRB, 500 μM NMDA, KRB, 100 mM KCl.

At the end of each experiment, probe positions were verified by histological examination. Only data obtained from animals with probes in the correct position were used for analysis.

HPLC-electrochemical analysis

Mobile phase (100 mM sodium dihydrogen phosphate monohydrate in 15% methanol v/v in polished water, pH 4.4 with phosphoric acid) was perfused through a reverse-phase column (4.6 × 80 mm, 3 μm; model HR-80; ESA, Inc., Chelmsford, USA) at 1.5 mL/min, using an ESA Model 582 solvent delivery module. O-phthalaldehyde (OPA)/sulfite stock solution was made by dissolving 22 mg of OPA in 0.5 mL of ethanol, and then adding 0.5 mL of 1 M sodium sulfite and 9 mL of 0.1 M sodium tetraborate, pH 10.0. The working OPA/sulfite solution was prepared daily by diluting the stock OPA/sulfite solution with polished water. Glutamate and GABA were automatically derivatized. Samples were maintained at 12°C, and 27 μL was injected on column by an ESA 542 autosampler. Electrochemical detection was performed at −400 mV (reduction electrode 1) and +200 mV (reduction electrode 2) with gain set at 200 nA. Similar to a previous report from our laboratory, the limits of detection for glutamate and GABA were 25 pg/injection and 0.78 pg/injection, respectively (Fu et al. 2000). Serially diluted standards containing known quantities of glutamate and GABA were included in each assay (R2 > 0.98).

Brain punches and tissue preparation

On day 11 of extinction from chronic nicotine SA, animals were killed to obtain brain tissues for western immunoblotting of ionotropic glutamate receptors. The brain punching procedure and tissue preparation were performed according to an established protocol (Wang et al. 2007). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, decapitated, and brains were removed and stored at −80°C. Frozen brain sections, 0.7 mm in thickness, were obtained using arrays of 20 double-edge razor blades, designed and assembled in our laboratory. The mPFC and VTA were punched out according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1986) using a 20 gauge syringe adapter. Dissected tissues were immediately transferred to tubes embedded in dry ice and stored at −80°C until further processing. Dissected tissues were sonicated in 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution for 30 s in an ice-water bath. Sonicated tissues were centrifuged at 800 g, 5 min. Protein concentrations were measured using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Western immunoblotting

To determine whether the up-regulated expression of ionotropic glutamate receptors observed during chronic nicotine SA (Wang et al. 2007) persisted after 10 days of extinction, western immunoblotting was performed following the protocol published previously (Wang et al. 2007). Briefly, prepared tissue samples were run on 10% polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 4°C overnight. Membranes were blocked by 5% non-fat dried milk for 2 h. Based on the molecular weight differences between NMDA receptor subunits, AMPA receptor subunits, and β-actin, blots were carefully cut into three separate sections by visualizing the molecular weight markers: upper blots were used to detect NMDA receptor subunits, middle blots to detect AMPA receptor subunits, and lower blots to detect β-actin in order to evaluate protein loading. Blots then were incubated with the following antibodies: mouse anti-beta actin (1 : 1000; Sigma), rabbit anti-glutamate receptor subtype 1 (GluR1; 1 : 1000; Upstate, Lake Placid, NY, USA), rabbit anti-GluR 2/3 (1 : 1000; Upstate), goat anti-NMDA receptor subtype 1 (NR1; 1 : 400; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or goat anti-NR 2A (1 : 200; Santa Cruz) or rabbit anti-NR 2B (1 : 500; Upstate). Blots were then washed in TBST and incubated in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1 : 3000 for beta actin, 1 : 1500 for all others). All antibodies were diluted in the same blocking solution and incubated for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Target proteins were visualized by Supersignal (Pierce) followed by imaging using a Biorad ChemiDoc with quantitation by Quantity One (Bio-Rad).

Sucrose SA

In two separate experiments, we examined the effects of blocking mPFC NMDA receptors or VTA AMPA receptors on sucrose SA. Beginning 7 days after stereotaxic implantation of microinjection guide cannulae into mPFC or VTA, rats were food-deprived to 18 g of standard food pellets per day for the duration of the experiment and the first training session, using sucrose pellet reinforcement, was initiated 2 days, thereafter. In each training session, rats were placed in an operant chamber for no longer than 60 min or until 100 sucrose pellets were obtained on an FR1 schedule. Since all animals obtained 100 sucrose pellets within 60 min after stable sucrose SA had been established, we used the time required to obtain 100 sucrose pellets to measure the effects of treatment on sucrose SA.

The operant chamber consisted of two levers positioned 7 cm above the floor; a yellow cue light 1 cm above each lever signaled the availability of sucrose pellets (45 mg, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA). One lever, randomly assigned as active, triggered the delivery of a sucrose pellet; pressing the inactive lever had no programmed consequence. The delivery of each sucrose pellet was followed by a 10 s time-out during which the yellow light above the active bar was not illuminated and sucrose pellets were not available. The animals acquired the behavior by day 10 ± 0.97. The sucrose-training phase continued for a total of 18 days, in parallel to the number of days that animals self-administered nicotine in other experiments. On day 19, two separate experiments were conducted to determine the effects of the NMDA or AMPA receptor antagonists, AP-5 or NBQX, on sucrose reinforced operant behavior.

Intraparenchymal microinjections after chronic nicotine SA or sucrose SA

We examined the effects of blocking either mPFC NMDA receptors or VTA AMPA receptors in separate groups of rats that self-administered either nicotine or sucrose. Rats were acclimated to the stress of brain microinjection by handling for 3 min prior to the start of each sucrose SA training or nicotine SA session. After 18 days of sucrose or nicotine SA, rats received microinjections in the mPFC or VTA on days 19, 21 and 23, 10 min prior to the test session; they self-administered nicotine or sucrose on the intervening days. On the three test days, each rat which self-administered either nicotine or sucrose received a microinjection (500 nL/120 s) of KRB or AP-5 (1.5 or 5 μg, bilaterally) into the mPFC in a counterbalanced order. Similarly, separate groups of rats received microinjections of KRB or NBQX (0.067 or 0.25 μg, bilaterally) into the VTA.

Locomotion

To determine whether an intra-VTA microinjection of NBQX impaired movement, we evaluated the effects of intra-VTA NBQX on locomotion. Locomotor activity was measured by a Digiscan Micro Monitoring system (Omni-tech Electronics, Columbus, Ohio, USA). This system consists of an activity box (45 cm × 24 cm × 19 cm) placed on a sensor-equipped aluminum frame within a sound-attenuating chamber. The frames contain 16 light beams and detectors, linked to a computer via a micro analyzer (Accuscan Instruments Inc., Columbus, OH, USA). Movement is detected by a photocell when the animal interrupts an individual light beam. A day before the first day of an experiment, each animal was adapted to the behavioral chamber and injection procedure for 120 min. On experimental day 1, 3, and 5, when locomotor activity data were collected, each animal was placed in a test chamber 1 h before receiving a microinjection. Following an injections, locomotor activity was recorded in 15 min bins for 2 h.

Data analysis

To determine the specificity of nicotine SA, the number of active and inactive lever presses per day were compared within each treatment group (i.e., nicotine and saline) and between group by two-way ANOVA (SPSS 13.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

For microdialysis experiments, the peak heights of each analyte were analyzed by PowerChrom (ADInstruments, Castle Hill, Australia) and concentrations were determined by interpolation of sample peak heights relative to standard curves. In each animal, the basal glutamate or GABA value was defined as the average of the three samples collected immediately prior to the administration of NMDA. Group data (mean ± SEM) were expressed as a multiple of the basal glutamate or GABA level that was determined for each animal. All statistical analyses of glutamate and GABA levels were performed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures (SPSS 13.0; SPSS Inc.,) with the exception of analysis of peak incremental responses, which used one-way ANOVA.

For western immunoblotting, each sample from a rat was run once on each of two gels. Optical density values for each lane were normalized to β-actin in order to control for variation in loading and transfer. For each sample, normalized values that had been averaged between the two blots were used to conduct statistical comparisons (unpaired student t-test) to identify treatment effects within a region for each subunit. The mean values of nicotine treatment groups were expressed as a percentage of saline ± SEM. Treatment differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Lastly, the effects of AP-5 or NBQX on chronic nicotine or sucrose SA were examined by one-way ANOVA, followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc tests to detect differences between vehicle and drug effects. The effects of NBQX on locomotion were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures.

Results

Chronic nicotine SA and extinction from nicotine SA

Figure 1a shows the acquisition and maintenance of chronic nicotine SA by rats that were microdialyzed on day 19. From day 4 onward, active lever presses (FR1) in the nicotine SA group were approximately 3–4-fold higher than inactive presses (two-way ANOVA with repeated measures: F1,10 = 38.89, p < 0.001). In addition, the number of active lever presses was greater in the nicotine than saline SA group (F1,10 = 7.21, p < 0.05). There was no difference in active versus inactive lever presses in the saline group (F1,10 = 0.31, p > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Lever press activity during chronic nicotine self-administration (SA) and extinction. (panel a) Adult male Lewis rats acquired nicotine SA (0.03mg/kg b.wt./injection, iv) without prior training, priming or food deprivation when the drug was available 23 h/day from days 1–18. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures revealed that active lever presses were greater than inactive presses in the nicotine (Nic) group (F1,10 = 38.89, p < 0.001; n = 7), but not in the saline (Sal) group (F1,10 = 0.31, p > 0.05; n = 5). Comparing treatment groups, active lever presses were greater in the Nic than Sal group (F1,10 = 6.79, p < 0.05). (panel b) A separate cohort of rats self-administered Nic or Sal for 18 days, followed by 10 days of extinction. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures showed that, after extinction, active lever presses in the Nic group (n = 4) were no longer different from the Sal (n = 4) group (F1,6 = 3.71, p > 0.05). In addition, the mean number of active lever presses during the last 3 days of the late maintenance phase (d 16–18) were greater than during the final 3 days of the extinction period (e.g., days 26–28) (F1,6 = 12.11, p > 0.05). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

The SA profiles of rats that were microdialyzed after extinction from chronic nicotine SA are shown in Fig. 1b. Similar to Fig. 1a, during the first 18 days, active lever presses were greater than inactive in the nicotine SA group (F1,6 = 13.78, p < 0.05), whereas no difference was observed in the saline group (F1,6 = 0.22, p > 0.05). During the 10 day extinction period, active lever presses were no greater in the nicotine group compared to saline (F1,6 = 3.71, p > 0.05). Furthermore, comparing the final 3 days of the extinction phase to that during nicotine SA, the mean number of active lever presses were less (extinction versus nicotine SA: 23.9 ± 5.2 vs. 53.8±6.8 active lever presses; F1,6 = 12.11, p < 0.05).

mPFC and VTA glutamate responsiveness to intra-mPFC NMDA during chronic nicotine SA

Histological evaluation was performed to determine whether the membrane region of microdialysis probes and the tip of microinjection cannulae were within mPFC and VTA. Figure 2 shows the neuroanatomical location of these probes and cannulae from rats which were included in the data analyses.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the positions of all microdialysis probes and microinjection cannulae in the rat mPFC and VTA. Coronal brain sections were analyzed to verify the position of the membrane segment of each microdialysis probe and microinjection cannulae (the membrane regions of probes are indicated by line segments and the tips of microinjection cannulae by dots). All animals used in these investigations are represented. mPFC and VTA diagrams are 3.0 mm anterior and 5.95 mm posterior to bregma, respectively (adapted from Paxinos and Watson 1986).

On day 19 of nicotine and saline SA, two sequential doses of NMDA were administered via the mPFC microdialysis probe during dual probe (mPFC and VTA) microdialysis of freely moving rats. Chronic nicotine SA did not affect basal glutamate levels in the mPFC (108.4 ± 16.1 vs. 93.1 ± 17.9 pg/μL for nicotine and saline SA, respectively; p > 0.05) or VTA (21.7 ± 4.1 vs. 20.9 ± 3.7 pg/μL for nicotine and saline SA, respectively; p > 0.05). Fig. 3a shows that nicotine SA enhanced the mPFC glutamate release induced by 200 μM NMDA (F1,10 = 6.76, p < 0.05), but not by 500 μM NMDA (F1,10 = 0.91, p > 0.05). Further analysis of the same data, expressed as peak incremental glutamate responses (Fig. 3b), showed that both nicotine SA and the dose of NMDA affected glutamate release (two-way ANOVA: F1,10 = 15.77, p < 0.01 and F1,10 = 31.13, p < 0.001, respectively). Additionally, nicotine SA amplified the effects of both 200 μM and 500 μM NMDA (one-way ANOVA: F1,10 = 9.71, p < 0.05 and F1,10 = 8.74, p < 0.05, respectively). In contrast, the mPFC glutamate response to 100 mM KCl was not affected by nicotine SA (F1,10 = 0.99, p > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Chronic nicotine SA enhanced glutamate release in the mPFC and VTA induced by intra-mPFC NMDA (administered by reverse microdialysis). Glutamate was measured in microdialysates obtained concurrently from both brain regions. Basal levels of glutamate in mPFC and VTA were unaffected by nicotine SA. (panel a) In mPFC, glutamate responses to NMDA (200 μM and 500 μM) and 100 mM KCl were determined on day 19 of SA. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures revealed that nicotine SA (Nic; n = 7) amplified the glutamate response to 200 μM NMDA in comparison to saline SA (Sal; n = 5) (F1,10 = 6.76, p < 0.05). (panel b) In mPFC, the glutamate peak incremental responses were calculated from the data in panel a. One way ANOVA indicated that these responses were enhanced by nicotine SA (200 μM NMDA, F1,10 = 9.71, p < 0.05; 500 μM NMDA, F1,10 = 8.74, p < 0.05). (panel c) In VTA, the glutamate responses to NMDA and KCl were determined on day 19 of SA. Nicotine SA (n = 7) amplified the glutamate responses to 200 μM and 500 μM NMDA in comparison to saline (n = 5) (F1,10 = 6.36, p < 0.05 for 200 μM NMDA; F1,10 = 5.96, p < 0.05 for 500 μM NMDA). (panel d) In VTA, the glutamate peak incremental responses were calculated from the data in panel c. NMDA dose-dependently stimulated glutamate release (F1,9 = 18.73, p < 0.01). The glutamate responses to both doses of NMDA were enhanced by nicotine SA (one-way ANOVA: 200 μM NMDA, F1,9 = 16.99, p < 0.01; 500 μM NMDA F1,9 = 16.67, p < 0.01). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 comparing Nic vs. Sal SA at the same dose of NMDA.

Figure 3c, shows the time course of glutamate release in the VTA in response to different concentrations of intra-mPFC NMDA or 100 mM KCl on day 19 of chronic nicotine SA. Nicotine SA amplified the release of VTA glutamate stimulated by 200 and 500 μM NMDA (two-way ANOVA: F1,10 = 6.36, p < 0.05 and F1,10 = 5.96, p < 0.05, respectively). The peak incremental glutamate responses (Fig. 3d) were affected by nicotine SA and the dose of NMDA (F1,9 = 32.21, p < 0.001 and F1,9 = 18.73, p < 0.01, respectively), but there was no interaction between these variables (F1,9 = 2.33, p > 0.05). Additionally, the peak glutamate responses to 200 and 500 μM NMDA were both increased by nicotine SA (one-way ANOVA: 200 μM NMDA: F1,9 = 16.99, p < 0.01; 500 μM NMDA: F1,8 = 16.67, p < 0.01). Lastly, nicotine SA did not affect the peak incremental glutamate response to 100 mM KCl (F1,9 = 0.17, p > 0.05). Therefore, chronic nicotine SA augmented glutamate responsiveness to NMDA in mPFC and VTA without affecting basal levels of glutamate in these regions.

mPFC and VTA glutamate responsiveness to intra-mPFC NMDA after extinction from chronic nicotine SA

On day 11 following the extinction of nicotine SA, animals were microdialyzed to assess the persistence of glutamate hyper-responsiveness to intra-mPFC NMDA. In both mPFC and VTA, basal glutamate levels were unaffected by prior nicotine SA (nicotine vs. saline SA: 102.0 ± 18.8 vs. 93.8 ± 15.9 pg/μL in mPFC and 27.8 ± 6.0 vs. 34.0 ± 10.0 pg/μL in VTA; p > 0.05 for both comparisons). On day 11, Fig. 4a shows that NMDA-induced glutamate release in mPFC was no longer enhanced by the prior SA of nicotine (F1,6 = 0.50, p > 0.05). Additionally, the glutamate response was greater to 500 μM than 200 μM NMDA (F1,6 = 16.91, p < 0.01). Similarly, in the VTA, Fig. 4b shows the persistence of dose-dependent NMDA-induced glutamate release (F1,6 = 18.86, p < 0.01) and the absence of enhancement by prior nicotine SA (F1,6 = 0.02, p > 0.05). Hence, glutamate hyper-responsiveness was no longer detected in mPFC or VTA by day 11 after extinction of chronic nicotine SA.

Fig. 4.

After extinction from chronic nicotine SA, glutamate release in the mPFC (panel a) and VTA (panel b), induced by intra-mPFC NMDA, was not enhanced by prior nicotine SA. Glutamate was measured in concurrent microdialysates obtained from both brain regions. Basal levels of glutamate in mPFC and VTA were unaffected by prior nicotine SA. After 10 days of extinction, two-way ANOVA with repeated measures indicated that both the mPFC and VTA glutamate responses induced by intra-mPFC NMDA (200 or 500 μM; administered by reverse microdialysis) or KCl were not affected by prior nicotine SA [mPFC (panel a):F1,6 = 0.50, p > 0.05; VTA (panel b): F1,6 = 0.02, p > 0.05; n = 4 for Nic and Sal].

mPFC and VTA GABA responsiveness to intra-mPFC NMDA during chronic nicotine SA

GABA levels were measured to evaluate whether nicotine SA altered GABA levels in association with the foregoing changes in glutamate release. Chronic nicotine SA did not affect basal GABA levels in the mPFC or VTA (nicotine vs. saline SA: 1.1 ± 0.3 vs. 1.5 ± 0.3 pg/μL in mPFC, p > 0.05; 1.2 ± 0.3 vs. 1.7 ± 0.2 pg/μL in VTA, p > 0.05). Figure 5a shows that mPFC GABA levels were stimulated by 200 and 500 μM NMDA (200 μM NMDA: F1,14 = 17.41, p < 0.01; 500 μM NMDA: F1,14 = 6.18, p < 0.05), but were not affected by nicotine SA (F1,6 = 0.45, p > 0.05) (data were combined from both treatment groups for analysis of NMDA effects in Fig. 5a and b). In contrast, VTA GABA (Fig. 5b) was not increased by intra-mPFC NMDA (200 μM NMDA: F1,10 = 2.18, p > 0.05; 500 μM NMDA: F1,10 = 3.09, p > 0.05). Intra-mPFC KCl stimulated GABA release in both regions (F1,14 = 32.87, p < 0.001 for mPFC, data not shown; F1,10 = 19.56, p < 0.01 for VTA). In summary, nicotine SA had no effect on basal or NMDA induced GABA release in the mPFC or VTA.

Fig. 5.

GABA responses in the mPFC (panel a) and VTA (panel b), induced by intra-mPFC NMDA, were not enhanced by prior nicotine SA. GABA levels were measured on the microdialysates obtained in the experiments shown in Fig. 3. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures showed that the mPFC and VTA GABA responses to 200 or 500 μM NMDA were not affected by nicotine SA [mPFC (panel a): F1,6 = 0.45, p > 0.05; VTA (panel b): F1,4 = 0.51, p > 0.05; n = 3–5).

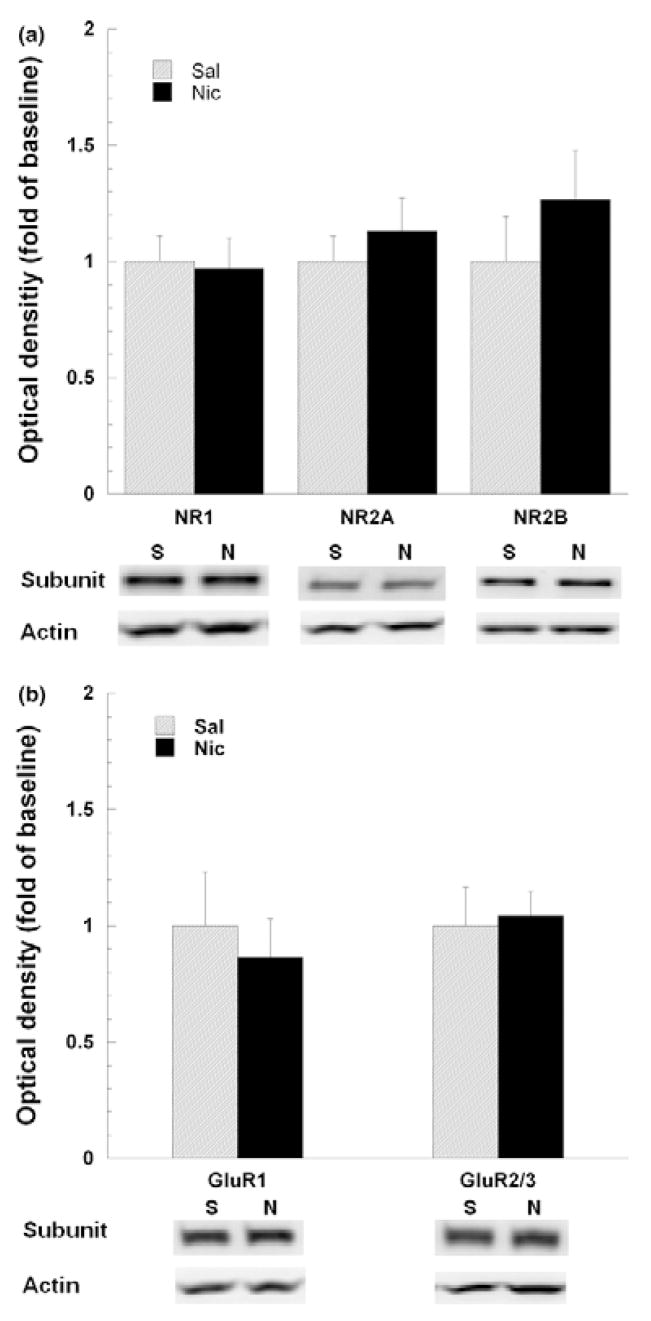

Expression of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits in the mPFC and VTA after extinction from nicotine SA

We have previously reported that specific ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits, in mPFC and VTA, are up-regulated by chronic nicotine SA (Wang et al. 2007). To further evaluate the association between glutamate hyper-responsiveness and receptor subunit expression, these specific subunits were quantified by western immunoblotting of mPFC and VTA extracts obtained from animals after 10 days of extinction from nicotine SA. Representative gels from each treatment group are shown in Fig. 6. NMDA receptor NR2A and NR2B subunits were both visualized as single bands at approximately 180 kDa. In contrast to the up-regulation of NR2A and NR2B subunits in mPFC during nicotine SA (Wang et al. 2007), after 10 day of extinction this was not longer evident (Fig. 6a). The GluR1 and GluR2/3 subunits in VTA were each single bands visualized at 106 and 110 kDa, respectively (Fig. 6b). The up-regulated expression of GluR2/3, previously reported during nicotine SA (Wang et al. 2007), did not persist after 10 days of extinction. Therefore, after extinction from chronic nicotine SA, there was no longer evidence of enhanced glutamate receptor subunit expression in mPFC or VTA, nor glutamate hyper-responsiveness to the intra-mPFC administration of NMDA.

Fig. 6.

After extinction of nicotine SA, the mPFC and VTA levels of the ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits, NR1, NR2A, NR2B, GluR1 and GluR2/3 were unaffected by prior nicotine SA. Following regional brain microdissection and punching, tissue extracts were prepared in SDS, separated by electrophoresis, and then subjected to western immunoblotting and quantitation, as described in the Methods. For all subunits, data were normalized to β-actin levels and then converted to mean percentage of saline (± SEM) for each subunit. Representative blots comparing saline (S) vs. nicotine (N)-treated animals are shown for each subunit. (panel a) In mPFC, the previously reported enhancement of NMDA receptor subunit expression (e.g., NR2A and NR2B) by nicotine SA was no longer detectable (unpaired student t-test, p > 0.05 for each subunit; n = 4 per group) (Wang et al. 2007). (panel b) Similarly, in the VTA, the reported elevation of the AMPA receptor subunit, GluR2/3, during nicotine SA, was not detected after extinction (unpaired student t-test, p > 0.05 for each subunit; n = 4 per group).

The effects of blockade of mPFC NMDA receptors on the maintenance of chronic nicotine SA and sucrose SA

To evaluate the potential role of mPFC NMDA receptors in the maintenance of chronic nicotine SA in comparison to sucrose SA, in two separate groups of animals, the NMDA receptor antagonist, AP-5 (1.5 or 5 μg/side), was microinjected into mPFC bilaterally 10 min before the initiation of an SA session. On days 19, 21, and 23, during both nicotine SA and sucrose SA, AP-5 or KRB was administered in a counterbalanced order. The intra-mPFC microinjection of AP-5 had no effect on active lever presses or the time required to obtain 100 sucrose pellets during chronic nicotine SA (p > 0.05; Fig. 7a) and sucrose SA (p > 0.05; Fig. 7b), respectively. In a separate experiment, the pharmacological efficacy of the foregoing microinjection of AP-5 was validated by microdialyzing the VTA following bilateral intra-mPFC NMDA ± AP-5 microinjection. AP-5 (5 μg/side) abolished the release of glutamate in the VTA (F1,3 = 31.84, p < 0.05; data not shown). Therefore, NMDA receptors located in the mPFC are not required to maintain chronic nicotine or sucrose SA.

Fig. 7.

The NMDA receptor antagonist, AP-5, did not affect the maintenance of chronic nicotine or sucrose SA. Using a counterbalanced design in two separate cohorts of animals (nicotine SA, panel a; sucrose SA, panel b), each animal received AP-5 (1.5 and 5 μg/side) and KRB microinjected into mPFC 10 min before the initiation of daily test sessions on days 19, 21, and 23, after 18 days of nicotine or sucrose SA. Animals self-administered nicotine or sucrose on days 20 and 22 without receiving mPFC injections. (panel a) Active lever presses, expressed as the ratio of presses on the treatment day/presses on the preceding day without treatment, were not altered by AP-5 in the nicotine SA group (one way ANOVA: F2,15 = 0.25, p > 0.05, n = 6). (panel b) The time required to obtain 100 sucrose pellets in response to lever pressing (FR1) was expressed as the ratio of time required on the treatment day/time required on the preceding day without treatment. This ratio was not affected by intra-mPFC AP-5 (one way ANOVA, F2,25 = 0.44, p > 0.05, n = 8–10 per group).

The effects of blockade of VTA AMPA receptors on the maintenance of chronic nicotine SA and sucrose SA

We have reported that glutamate receptor subunits (e.g., GluR2/3) up-regulate in the VTA during chronic nicotine SA (Wang et al. 2007). Therefore, experiments were designed to evaluate whether the AMPA receptor antagonist, NBQX, reduced chronic nicotine SA in comparison to sucrose SA. In two separate groups of animals, NBQX (0.067 or 0.25 μg/side) or KRB was microinjected into VTA prior to SA sessions on days 19, 21, and 23 in each paradigm. NBQX (0.25 μg/side) reduced the number of active lever presses during nicotine SA (Fig. 8a) and increased the time required to obtain 100 sucrose pellets during sucrose SA (Fig. 8b) (F2,27 = 8.89, p < 0.01 for chronic nicotine SA; F2,15 = 35.59, p < 0.001 for sucrose SA). To determine whether the reduction in operant responding reflected an impairment of locomotion, we tested the effect of the intra-VTA administration NBQX (0.25 μg/side) on locomotion (Fig. 8c). Pre-treatment with NBQX had no effect on locomotion (F2,15 = 0.04, p > 0.05). Therefore, AMPA receptors in the VTA are required for nicotine reinforced and sucrose reinforced operant behaviors.

Fig. 8.

The AMPA receptor antagonist, NBQX, reduced active lever pressing and increased the time required to obtain 100 sucrose pellets during the maintenance phase of chronic nicotine SA and sucrose SA, respectively, when administered into the VTA. Using a counterbalanced design in two separate cohorts of animals (nicotine SA, panel a; sucrose SA, panel b), each animal received NBQX (0.067 and 0.25 μg/side) and KRB microinjected into VTA 10 min before the initiation of daily test sessions on days 19, 21, and 23, after 18 days of nicotine or sucrose SA. Animals self-administered nicotine or sucrose on days 20 and 22 without receiving VTA injections. (panel a) Active lever presses, expressed as the ratio of presses on the treatment day/presses on the preceding day without treatment, were reduced by intra-VTA NBQX at 0.25 μg/side (one way ANOVA, F2,27 = 8.90, p < 0.01, n = 10). (panel b) The time required to obtain 100 sucrose pellets in response to lever pressing (FR1) was expressed as the ratio of time required on the treatment day/time required on the preceding day without treatment. This ratio was increased by intra-VTA NBQX at 0.25 μg/side (one way ANOVA, F2,15 = 35.60, p < 0.001, n = 6). (panel c) Intra-VTA NBQX did not affect locomotion (two-way ANOVA with repeated measures, F2,15 = 0.04, p > 0.05). *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, compared to intra-mPFC or -VTA microinjection of KRB; #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.001, compared to intra-mPFC or -VTA microinjection of NBQX 0.067 μg/side.

Discussion

Though many of the neurochemical and molecular effects of nicotine have been well studied, the drug’s long-term neuroadaptive effects, specifically within the mesocorticolimbic glutamatergic pathway, are largely undefined. Based on recent evidence showing that NMDA and AMPA receptors are up-regulated in the mPFC and VTA, respectively, during chronic nicotine SA (Wang et al. 2007), we hypothesized that there may exist a hyper-glutamatergic state of neurotransmission between the mPFC and VTA during chronic nicotine SA. The current study revealed enhanced glutamate responsiveness to stimulation with NMDA, not only at the site of perfusion within the mPFC but also from mPFC afferents to the VTA during the late maintenance phase of chronic nicotine SA (day 18). Enhanced glutamate responsiveness was only demonstrable during nicotine SA, and was undetectable after extinction. Furthermore, the previously reported up-regulation of ionotropic glutamate receptors did not persist after extinction. Behavioral studies indicated that the NMDA receptors in the mPFC were not required to maintain chronic nicotine SA, while VTA AMPA receptors were required. Blockade of AMPA receptors in the VTA decreased nicotine reinforced and sucrose reinforced operant behaviors without affecting the locomotion. Thus, neuroadaptive changes involving ionotropic glutamate receptors and NMDA receptor-dependent glutamate neurotransmission between mPFC and VTA are induced by nicotine SA. VTA AMPA receptors are necessary for the maintenance of nicotine SA.

The glutamatergic regulation of VTA DA neurons undergoes adaptive changes that are involved in the reinforcing effects of nicotine (Fagen et al. 2003). Nicotine stimulates DA secretion in the NAcc, an effect common to all drugs of abuse, in part by increasing glutamate release in the VTA, which in turn induces burst firing of DA neurons in the VTA (Grenhoff et al. 1986; Svensson et al. 1990; Mansvelder and McGehee 2002). Nicotine induces long-term potentiation of these DA neurons that depends on pre- and post-synaptic changes (Mansvelder and McGehee 2000). The present study showed that 200 μM NMDA, perfused into mPFC by microdialysis, significantly stimulated glutamate release in the mPFC and VTA of nicotine self-administering rats, but not controls. Although a concentration of 500 μM NMDA induced glutamate release in the mPFC and VTA of both treatment groups, glutamate levels were significantly greater in the nicotine SA group. Thus, depending on the dose of NMDA, concurrent nicotine SA either potentiated or amplified glutamate release. In the VTA, these were not local effects of NMDA, indicating that nicotine SA had effected a state of enhanced glutamate neurotransmission.

Enhanced glutamate neurotransmission has been observed after cocaine and amphetamine were withdrawn. Ten days after five daily cocaine treatments, an injection of cocaine stimulated significantly more NAcc glutamate release in animals pre-treated with the drug compared to saline (Reid and Berger 1996). Similarly, intra-VTA AMPA stimulated more glutamate release in the VTA and NAcc of rats withdrawn from repeated daily injections of amphetamine than saline (Giorgetti et al. 2001). Thus, relatively few exposures to a psychostimulant are sufficient to induce a lasting state of enhanced glutamate responsiveness to the drug or to AMPA. Apparently, the amplification of glutamate responses to intra-VTA AMPA is indirect, mediated by the enduring effects of amphetamine on AMPA-stimulated DA and/or GABA neurotransmission in NAcc and VTA (Giorgetti et al. 2001).

The mechanism(s) whereby nicotine SA potentiates or amplifies NMDA-stimulated glutamate secretion in mPFC and VTA are unknown, although the increased expression of NR2A and NR2B subunits and possibly NMDA receptors, expressed on pyramidal neurons in mPFC (Huntley et al. 1994), is likely to be involved. If the increase in mPFC NMDA receptor expression occurs on pyramidal neurons and is proportional to that reported previously for the subunits (Wang et al. 2007), the sensitivity to intra-mPFC NMDA would increase significantly; this would be likely to account for the amplification and possibly the potentiation of glutamate release, at 500 and 200 μM, respectively, during nicotine SA. Notwithstanding this, the potential role of GABA is worthy of consideration. GABA interneurons in mPFC inhibit pyramidal neurons (Tzschentke and Schmidt 2000), and several reports have shown that GABA neurotransmission is affected by nicotine. Chronic injections of nicotine abolished the inhibitory effect of GABAB receptors on electrically evoked DA release in the VTA (Amantea and Bowery 2004). In the PFC, GABAB receptor mRNA was reduced by chronic exposure to nicotine, suggesting that nicotine SA might diminish the inhibitory regulation of pyramidal neurons (Li et al. 2004). If this occurs, one might expect this defect to spare GABA interneurons, since basal and NMDA-stimulated GABA release in mPFC was unaffected by nicotine SA in the present study. In contrast, a reduction in the expression of GABAB receptors on PFC GABA interneurons would probably be accompanied by increased basal GABA levels and enhanced NMDA-induced GABA release. Inhibitory regulation of mPFC pyramidal neurons by GABAB receptors has been demonstrated in experiments showing that stimulation of VTA glutamate release by intra-mPFC KCl was enhanced by blockade of mPFC GABAB receptors (Harte and O’Connor 2005). Thus, it is conceivable that both enhanced expression of NMDA receptors and reduced expression (or function) of GABAB receptors on mPFC pyramidal neurons are responsible for the enhanced release of glutamate by NMDA.

After extinction from chronic nicotine SA, we no longer detected the augmentation of NMDA-induced glutamate release in mPFC or VTA. Furthermore, the increased expression of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits in these regions had reverted to control levels. The reversal of adaptive changes in neurotransmission and receptor expression is consistent with findings from several psychostimulant studies showing that cellular and neurochemical adaptations are often transient. For example, decreased levels of VTA Giαand Goα proteins, detectable at 1 h or 6 h after repeated injections of cocaine, were not present by 24 h (Nestler et al. 1990; Striplin and Kalivas 1992). In a neurochemical study, AMPA-stimulated glutamate release in the VTA and NAcc was only augmented at 3 days, but not 14 days, after a regimen of repeated amphetamine treatments (Giorgetti et al. 2001). Finally, an electrophysiological study showed that the AMPA-induced firing of VTA DA neurons in vitro was enhanced at 3 but not 14 days following repeated exposure to cocaine or amphetamine (Zhang et al. 1997). The latter two studies indicate that the enhanced VTA glutamate neurotransmission following exposure to psychostimulants is transient and involves AMPA receptors, which were up-regulated in our previous study (Wang et al. 2007). Taken together, these studies all demonstrate that repeated exposure to psychostimulant drugs commonly induce molecular and neurochemical adaptations involving glutamate and DA neurotransmission in the mesolimbic system.

Since we found that glutamate receptor expression and glutamate neurotransmission were enhanced on day 19 of nicotine SA, studies were designed to determine whether NMDA and AMPA receptor antagonists impaired nicotine SA at this time. AP-5, an NMDA receptor antagonist, was microinjected bilaterally into the mPFC, where NMDA receptor subunit expression was increased (Wang et al. 2007); neither nicotine SA nor sucrose-reinforced operant behavior was affected. These observations are consistent with reports showing that blockade of NMDA receptors within the mPFC impaired the acquisition but not the expression of appetitive instrumental learning (Baldwin et al. 2000, 2002). Subsequently, NBQX, an AMPA receptor antagonist, was microinjected into the VTA, where GluR2/3 receptor subunit expression was increased (Wang et al. 2007); at the higher dose of NBQX, both nicotine SA and sucrose reinforced operant behavior was significantly inhibited. These observations suggest that VTA AMPA receptors are required for the maintenance of both operant behaviors. Hence, drug-induced neuroplasticity, involving the up-regulation of VTA GluR2/3-containing AMPA receptors, may not underlie the efficacy of NBQX; VTA AMPA receptors may generally be required to maintain these appetitive operant behaviors.

AMPA receptors in the VTA are involved in behavioral, neurochemical and electrophysiological changes induced by chronic exposure to abused drugs. These receptors in the VTA are required for the initiation of behavioral sensitization to cocaine (Licata et al. 2004), and although the blockade of AMPA receptors by systemically administered antagonists failed to inhibit the expression of behavioral sensitization to these psychostimulants (Li et al. 1997), such blockade was effective against ethanol sensitization (Broadbent et al. 2003). VTA AMPA receptors are also necessary for the initiation of morphine conditioned place preference (Harris et al. 2004). Neurochemically, repeated exposure to amphetamine has been shown to augment the release of mesolimbic DA and glutamate by intra-VTA AMPA (Giorgetti et al. 2001). Electrophysiologically, AMPA receptors have been shown to stimulate and enhance the burst firing of VTA DA neurons (Meltzer et al. 1997). Burst firing of DA neurons has been shown to be more efficient than single spike firing in the enhancement of phasic DA release and the transduction of salient stimuli (Chergui et al. 1993; Overton and Clark 1997; Schultz et al. 1997).

Nicotine increased the burst firing of VTA DA neurons (Grenhoff et al. 1986; Svensson et al. 1990) by stimulating glutamate release through pre-synaptic α7 receptors in VTA (Schilstrom et al. 2003). Additionally, a single injection of nicotine or other drugs of abuse (e.g. cocaine, d-amphetamine, ethanol) induced an increase in the strength of synapses on VTA DA neurons (i.e., increased AMPAR/NMDAR excitatory postsynaptic currents) (Saal et al. 2003). This is consistent with our report showing up-regulation of VTA GluR2/3, but not NMDA receptors, in the VTA during chronic nicotine SA (Wang et al. 2007). Taken together, these studies indicate that VTA AMPA receptors appear to manifest enhanced responsiveness and/or expression induced by various classes of abused drugs. These changes in function and expression of VTA AMPA receptors have been associated with enhanced DA and glutamate neurotransmission, and may be involved in behavioral sensitization and conditioned place preference to specific drugs of abuse. The current study indicates that VTA AMPA receptors are also involved in the maintenance of nicotine and food reinforced operant behavior.

These studies demonstrate the enhancement of glutamate neurotransmission in mPFC and VTA due to mPFC stimulation by NMDA during chronic nicotine SA. Based on recent neuroanatomical studies, the VTA glutamate measured herein may reflect two sources: direct glutamatergic projections from mPFC to VTA and glutamatergic fibers from LDTg and PPTg to VTA, activated by mPFC glutamatergic efferents to LDTg and PPTg (Tzschentke and Schmidt 2000; Omelchenko and Sesack 2005, 2007). This enhancement of glutamate neurotransmission is a transient adaptive change that correlates with the up-regulation of ionotropic glutamate receptors, requires coincident nicotine SA, and may specifically depend on the enhanced mPFC expression of NMDA receptors containing NR2A and NR2B subunits. Blockade of NMDA receptors in the mPFC did not affect the maintenance of chronic nicotine SA, while inhibition of VTA AMPA receptors decreased both nicotine and sucrose SA, indicating that VTA AMPA receptors may generally be required to maintain appetitive operant behavior.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIDA grant DA-03977 to BMS. No commercial sponsorship was involved. We are grateful to Professor Shannon Matta, Ph.D. and Jeff Steketee, Ph.D. for the technical guidance provided to Fan Wang.

Abbreviations used

- AMPA

alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-iso-xazolepropionic acid

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- DA

2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid, AP-5 Dopamine

- iGluR

ionotropic glutamate receptor

- KRB

Kreb’s Ringer Buffer

- LDTg

lateral dorsal tegmental nucleus

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- NAcc

nucleus accumbens

- nAchR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- NBQX

1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-nitro-2,3-dioxo-benzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide

- OPA

O-phthalaldehyde

- PPTg

pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus

- SA

self-administration

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

References

- Amantea D, Bowery NG. Reduced inhibitory action of a GABAB receptor agonist on [3H]-dopamine release from rat ventral tegmental area in vitro after chronic nicotine administration. BMC Pharmacol. 2004;4:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AE, Holahan MR, Sadeghian K, Kelley AE. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent plasticity within a distributed corticostriatal network mediates appetitive instrumental learning. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114:84–98. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AE, Sadeghian K, Kelley AE. Appetitive instrumental learning requires coincident activation of NMDA and dopamine D1 receptors within the medial prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1063–1071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01063.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent J, Kampmueller KM, Koonse SA. Expression of behavioral sensitization to ethanol by DBA/2J mice: the role of NMDA and non-NMDA glutamate receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;167:225–234. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, Sesack SR. Projections from the rat prefrontal cortex to the ventral tegmental area: target specificity in the synaptic associations with mesoaccumbens and mesocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3864–3873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03864.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chergui K, Charlety PJ, Akaoka H, Saunier CF, Brunet JL, Buda M, Svensson TH, Chouvet G. Tonic activation of NMDA receptors causes spontaneous burst discharge of rat midbrain dopamine neurons in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Franklin KB, Coen KM, Clarke PB. The mesolimbic dopaminergic system is implicated in the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:285–289. doi: 10.1007/BF02245149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Zhang J, Adamson KL. GABA mechanisms in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus influence particular aspects of nicotine selectively in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:190–197. doi: 10.1007/s002130100869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagen ZM, Mansvelder HD, Keath JR, McGehee DS. Short- and long-term modulation of synaptic inputs to brain reward areas by nicotine. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;1003:185–195. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Matta SG, Gao W, Brower VG, Sharp BM. Systemic nicotine stimulates dopamine release in nucleus accumbens: re-evaluation of the role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in the ventral tegmental area. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:458–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgetti M, Hotsenpiller G, Ward P, Teppen T, Wolf ME. Amphetamine-induced plasticity of AMPA receptors in the ventral tegmental area: effects on extracellular levels of dopamine and glutamate in freely moving rats. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6362–6369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06362.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenhoff J, Aston-Jones G, Svensson TH. Nicotinic effects on the firing pattern of midbrain dopamine neurons. Acta Physiol Scand. 1986;128:351–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1986.tb07988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Wimmer M, Byrne R, Aston-Jones G. Glutamate-associated plasticity in the ventral tegmental area is necessary for conditioning environmental stimuli with morphine. Neuroscience. 2004;129:841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte M, O’Connor WT. Evidence for a differential medial prefrontal dopamine D1 and D2 receptor regulation of local and ventral tegmental glutamate and GABA release: a dual probe microdialysis study in the awake rat. Brain Res. 2004;1017:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte M, O’Connor WT. Evidence for a selective prefrontal cortical GABA(B) receptor-mediated inhibition of glutamate release in the ventral tegmental area: a dual probe microdialysis study in the awake rat. Neuroscience. 2005;130:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley GW, Vickers JC, Morrison JH. Cellular and synaptic localization of NMDA and non-NMDA receptor subunits in neocortex: organizational features related to cortical circuitry, function and disease. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:536–543. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:565–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Drugs of abuse: anatomy, pharmacology and function of reward pathways. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90060-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wolf ME. Ibotenic acid lesions of prefrontal cortex do not prevent expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Behav Brain Res. 1997;84:285–289. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Vartanian AJ, White FJ, Xue CJ, Wolf ME. Effects of the AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX on the development and expression of behavioral sensitization to cocaine and amphetamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;134:266–276. doi: 10.1007/s002130050449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Hu XT, Berney TG, Vartanian AJ, Stine CD, Wolf ME, White FJ. Both glutamate receptor antagonists and prefrontal cortex lesions prevent induction of cocaine sensitization and associated neuroadaptations. Synapse. 1999a;34:169–180. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19991201)34:3<169::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wolf ME, White FJ. The expression of cocaine sensitization is not prevented by MK-801 or ibotenic acid lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex. Behav Brain Res. 1999b;104:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SP, Park MS, Kim JH, Kim MO. Chronic nicotine and smoke treatment modulate dopaminergic activities in ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens and the gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptor expression of the rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:868–879. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata SC, Schmidt HD, Pierce RC. Suppressing calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity in the ventral tegmental area enhances the acute behavioural response to cocaine but attenuates the initiation of cocaine-induced behavioural sensitization in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:405–414. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2003.03110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelder HD, McGehee DS. Long-term potentiation of excitatory inputs to brain reward areas by nicotine. Neuron. 2000;27:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelder HD, McGehee DS. Cellular and synaptic mechanisms of nicotine addiction. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:606–617. doi: 10.1002/neu.10148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Lapish CC, Kalivas PW. Prefrontal glutamate release into the core of the nucleus accumbens mediates cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3531–3537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03531.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer LT, Christoffersen CL, Serpa KA. Modulation of dopamine neuronal activity by glutamate receptor subtypes. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:511–518. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Molecular mechanisms of drug addiction. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2439–2450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02439.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Terwilliger RZ, Walker JR, Sevarino KA, Duman RS. Chronic cocaine treatment decreases levels of the G protein subunits Gi alpha and Go alpha in discrete regions of rat brain. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1079–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omelchenko N, Sesack SR. Laterodorsal tegmental projections to identified cell populations in the rat ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:217–235. doi: 10.1002/cne.20417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omelchenko N, Sesack SR. Glutamate synaptic inputs to ventral tegmental area neurons in the rat derive primarily from subcortical sources. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1259–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton PG, Clark D. Burst firing in midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;25:312–334. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; Sydney, Orlando: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Reid MS, Berger SP. Evidence for sensitization of cocaine-induced nucleus accumbens glutamate release. Neuroreport. 1996;7:1325–1329. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199605170-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saal D, Dong Y, Bonci A, Malenka RC. Drugs of abuse and stress trigger a common synaptic adaptation in dopamine neurons. Neuron. 2003;37:577–582. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilstrom B, Rawal N, Mameli-Engvall M, Nomikos GG, Svensson TH. Dual effects of nicotine on dopamine neurons mediated by different nicotinic receptor subtypes. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702003188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275:1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Pickel VM. Prefrontal cortical efferents in the rat synapse on unlabeled neuronal targets of catecholamine terminals in the nucleus accumbens septi and on dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol. 1992;320:145–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.903200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striplin CD, Kalivas PW. Correlation between behavioral sensitization to cocaine and G protein ADP-ribosylation in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res. 1992;579:181–186. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90049-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson TH, Grenhoff J, Engberg G. Effect of nicotine on dynamic function of brain catecholamine neurons. Ciba Found Symp. 1990;152:169–180. doi: 10.1002/9780470513965.ch10. discussion 180-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber MT, Das S, Fibiger HC. Cortical regulation of subcortical dopamine release: mediation via the ventral tegmental area. J Neurochem. 1995;65:1407–1410. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM, Schmidt WJ. Functional relationship among medial prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and ventral tegmental area in locomotion and reward. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2000;14:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JD, Hokanson JS, Matta SG, Sharp BM. Self-administration in rats allowed unlimited access to nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;133:300–304. doi: 10.1007/s002130050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Chen H, Steketee JD, Sharp BM. Upregulation of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits within specific mesocorticolimbic regions during chronic nicotine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:103–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME, Dahlin SL, Hu XT, Xue CJ, White K. Effects of lesions of prefrontal cortex, amygdala, or fornix on behavioral sensitization to amphetamine: comparison with N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists. Neuroscience. 1995;69:417–439. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00248-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XF, Hu XT, White FJ, Wolf ME. Increased responsiveness of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons to glutamate after repeated administration of cocaine or amphetamine is transient and selectively involves AMPA receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]