Abstract

Study objective

To examine the genealogy of the social capital concept in public health, with attention to the epistemological concerns and academic practices that shaped the way in which this concept was translated into public health.

Design

A citation‐network path analysis of the public health literature on social capital was used to generate a genealogy of the social capital concept in public health. The analysis identifies the intellectual sources, influential texts, and developments in the conceptualisation of social capital in public health.

Participants

The population of 227 texts (articles, books, reports) was selected in two phases. Phase 1 texts were articles in the PubMed database with “social capital” in their title published before 2003 (n = 65). Phase 2 texts are those texts cited more than once by phase 1 articles (n = 165).

Main results

The analysis shows how the scholarship of Robert Putnam has been absorbed into public health research, how three seminal texts appearing in 1996 and 1997 helped shape the communitarian form that the social capital concept has assumed in public health, and how both were influenced by the epistemological context of social epidemiology at the time.

Conclusions

Originally viewed in public health research as an ecological level, psychosocial mechanism that might mediate the income inequality‐health pathway, the dominance of the communitarian approach to social capital has given disproportionate attention to normative and associational properties of places. Network approaches to social capital were lost in this translation. Recovering them is key to a full translation and conceptualisation of social capital in public health.

Keywords: social capital, social epidemiology, public health practice

Recent criticisms of social epidemiological research have challenged conventional approaches that frame the study of social contexts and health.1,2,3 Indeed, Porta and Alvarez‐Dardet call for a “sociology of epidemiology” through which would emerge knowledge of epidemiological practice that would help push research and practice forward.4 Not only would the sociology of epidemiology need to examine the factors shaping epidemiological practice, it would also need to reflect critically on the way in which concepts from other fields and disciplines are translated into public health research. Our notion of translation originates from studies in the sociology of knowledge and seeks to highlight the situatedness of scientific knowledge and practice. The term “translation” emphasises how ideas become reshaped as they cross disciplinary boundaries and become embedded in different institutional contexts and intellectual paradigms.

To examine the making of one of the more important concepts of recent public health research,5 we present a genealogy of social capital in the public health literature. We use a genealogical approach rooted in a citation path analysis of the public health literature to examine how public health came to discover, translate, and apply the concept of social capital to health research. In what ways did epistemological concerns in public health frame the manner in which social capital came to take shape in health science research? Through such an analysis, we emphasise the importance of the concept of social capital for understanding the mechanisms and pathways by which social structure, social networks, and access to resources influence health.

Social capital: a recent history

The concept of social capital became prominent in the public health literature in 1996 when the term appeared in two important public health texts. In that year, Kaplan et al concluded that “investments in human and social capital” parallel state level variations in income inequality,6 while Wilkinson devoted a chapter of his book Unhealthy Societies to social capital and its potential for reconciling social divisions.7 One year later, Kawachi and colleagues published the first empirical study on the effects of social capital on population health.8 Despite acknowledging network approaches to social capital, Kawachi and colleagues define social capital in a manner that parallels the work of Robert Putnam—that is, as “features of social organization, such as civic participation, norms of reciprocity, and trust in others”.8 Using measures of trust and civic engagement, Kawachi suggested that social capital acts as an intervening variable along the income inequality‐population health pathway. This way of conceptualising and measuring social capital has been referred to as the communitarian approach to social capital.9 It is an approach that dominates public health research on social capital.10

Since these foundational writings, critics have questioned social capital's explanatory effects,11,12,13 its ideological presuppositions,9,14 and its limited conceptualisation.10,15,16 More recent criticisms have asked whether the study of social capital and health might be improved by an analytical focus on social networks and ties.17 For example, Szreter and Woolcock promote a “three‐dimensional approach” to social capital that recognises the different types of social connections—bonding, bridging, and linking—that serve to integrate individuals, groups, and communities into society.17 The difference between communitarian and network approaches is significant. Whereas communitarian approaches examine the effects of civic participation and trust on health, network approaches analyse relational dimensions of solidarity, highlighting the influence of social structure, power, and disparities in access to resources on health. Although we might speak of a network approach to social capital, it is important to recognise that there is no single network approach. Indeed, the approach that sociologists such as Coleman and Bourdieu take to the study of social capital fit within their broader theoretical orientations. For example, Bourdieu emphasises the fungibility of social capital within a broader political economy, while Coleman defines social capital in terms of its function in facilitating individual or group action.18 Yet, despite their differences, they both approach the study of social capital in terms of the resources found or accessed through social networks.

Efforts to rehabilitate the concept of social capital by bringing social networks and the resources embedded in those networks back into public health research raise the question of how such network approaches were marginalised in the first place. Answering this question requires an analysis of the intellectual and academic practices surrounding social capital's translation into public health research and how the translation processes associated with academic practices give precedence to some approaches while marginalising others. While others have emphasised the broader sociopolitical context in which the concept appears in public health,9 we examine citation habits as a form of practice through which intellectual hierarchies emerge and persist. In so doing, we develop work identifying the prevalence of Putnam's conceptualisation.10 In this study, we examine the genealogical history of the ways in which Putnam's concept of social capital was instantiated in the most influential public health texts and discuss how epistemological concerns reflected in those texts influenced the manner in which the concept of social capital took shape in public health. In our conclusion, we reflect on the consequences that this translation has had on the evolution of public health research on social capital and health.

Methods

To examine the way in which social capital emerged within the public health literature, we undertook a citation network analysis of public health texts genealogically related to the concept. The citation network analysis allows us to map the structure of the literature related to social capital, thereby identifying the more prominent and influential texts that have led to the development of the concept in public health as seen through the citation practices of researchers in the field.

Our citation genealogy of public health literature was constructed in two phases. In phase 1, we specified the boundaries around both public health literature and the texts within that literature that focused on social capital. We restricted our sample to the PubMed database, which contains over 12 million citations dating back to the mid‐1960s.19

The phase 1 search was conducted in January–February 2003 and was restricted to texts with “social capital” in their titles published before 2003. We restricted the search to the title on the grounds that “social capital” is probably the most central of the topics covered in that particular text.20 The earliest published public health article uncovered using this search strategy was the article by Kawachi et al that appeared in 1997.8 After eliminating those articles unrelated to social capital and non‐English language articles, the original population of 87 articles was reduced to 65 articles. These 65 articles comprised the phase 1 “social capital” text population.

To construct a citation genealogy of that literature, we expanded the text population in phase 2 to include those articles, books, chapters in edited volumes, and working papers or reports that were cited more than once in the original 65 articles. We identified an additional 162 texts as a result of this expanded search. The titles of those texts need not have included the term social capital in their titles nor have appeared in the PubMed database. This analysis is based on 227 texts—65 from phase 1 and 162 from phase 2.

The references for each of the 227 texts were examined to determine if they cited any of the other 226 works in the population. The citation network is based on the citation ties found to exist among the 227 texts. After the collection and input of the citation network data, centrality scores were determined for each text. Centrality measures the prominence of actors in a network.21,22 In a network containing directed ties, for example, “cites” or “is cited by,” a distinction can be made between in‐degree and out‐degree centrality. In‐degree centrality measures the prominence of certain texts in terms of “being cited,” while out‐degree centrality measures the prominence of texts in terms of “citing” other texts. Our analysis focuses on in‐degree centrality—that is, those texts that are more central in terms of being cited by other texts. Freeman in‐degree centrality scores for each text were calculated using the software package ucinet (software for social network analysis, Harvard, Analytic Technologies).

Next, a main path analysis was conducted on the citation data to map the development of the “social capital” public health literature over time. The main path through a citation network is the path with the highest “traversal counts”.23,24,25 Traversal counts measure the number of times that a tie between texts also connects other texts in a citation network.26 The main path analysis determines all possible paths through the network starting from an origin text to end point texts, and then calculates the number of links in the network.26 This provides a longitudinal perspective on how a research field has evolved according to the way scholars in the field have cited each other. The main path analysis was conducted using the software package Pajek (Pajek .90, 1996, http://vlado.fmf.uni‐lj.si/pub/networks/pajek/; network analysis of texts, working paper, http://vlado.fmf.uni‐lj.si/pub/networks/pajek/).

After the derivation of the main path, we conducted a frequency count on the number of times that a main‐path text cited another main‐path text. This allowed us to look more closely at the linkages and connections that exist among the key texts, and to identify important breaks along the path and any “bridging” texts in the literature.

Results

The mean centrality score for the citation network is 5.6, which means, roughly speaking, that each text was cited on average by six other texts. The most central or prominent text in the network is Putnam's Making Democracy Work27 with a degree centrality score of 74. The second most prominent text in the network is the article by Kawachi and colleagues (Social capital, income inequality, and mortality)8 with a centrality score of 51 (table 1).

Table 1 Ten most prominent (cited) texts in the citation network.

| Rank | Title | In‐degree score |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Making Democracy Work27 | 74 |

| 2 | “Social capital, income inequality, and mortality”8 | 51 |

| 3 | Foundations of Social Theory (Coleman 1990)28 | 48 |

| 4 | “Bowling alone: America's declining social capital”29 | 44 |

| 5 | Unhealthy Societies7 | 39 |

| 6 | “Social capital in the creation of human capital”30 | 37 |

| 7 | “Inequality in income and mortality in the United States: analysis of mortality and potential pathways”6 | 27 |

| 8 | “Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine‐year follow‐up study of Alameda County residents”31 | 26 |

| 9 | “Income distribution and mortality: cross sectional ecological study of the Robin Hood index in the United States”32 | 26 |

| 10 | “Income distribution and life expectancy”33 | 24 |

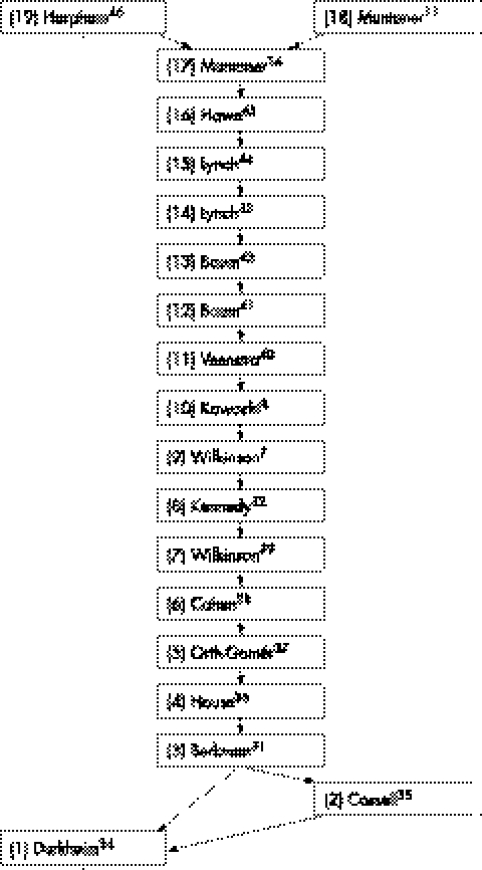

Nineteen texts appear on the main path (fig 1). At the top of the path, are the more recent texts on social capital. The text by Kawachi et al in 10th position indicates the first appearance of the term social capital in the title of a health related article. It marks an important moment in public health's application and acceptance of the concept10 and marks the first appearance of phase 1 articles in the path figure. Assessing the literature after this point (texts 11–19) allows us to examine the development of the concept of social capital after its first empirical application. By focusing on texts before this (texts 1–9), we can examine the intellectual sources for the concept's use and appearance in the public health literature. At the bottom of the path, are those texts that act as foundational sources for the concept in public health. Three texts are closely linked as intellectual sources for the concept's application in public health: Durkheim's Suicide,34 Cassel's “The contribution of the social environment to host resistance,”35 and Berkman and Syme's “Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine‐year follow‐up study of Alameda County residents.”31

Figure 1 Main path of social capital related literature.

Despite the prominence of Putnam's and Coleman's work as shown by their in‐degree centrality scores, the main path does not include a text by either author. In Putnam's case, this reflects how his work has been absorbed into mainstream thinking in public health.10 Coleman's prominence is attributable more to passing references to his work and not substantive or empirical applications of his conception of social capital.10

The frequency counts for the number of citations of one main path article by another reveal an important division in the literature between Cohen and Syme's edited volume on Social Support and Health38 and Wilkinson's article on the epidemiological transition39 (table 2). This reflects the two fields of literature from which the concept of social capital in public health has emerged and confirms Szreter and Woolcock's observation18 about the divide between the social support and health literature on the one hand and the income inequality and health literature on the other.

Table 2 Citations among main path texts.

| ID | Text | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | Harpham, 2002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 18 | Muntaner, 2002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 17 | Muntaner, 2001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| 16 | Hawe and Shiell, 2000 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| 15 | Lynch 2000b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |||||

| 14 | Lynch 2000a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ||||||

| 13 | Baum 1999b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||||

| 12 | Baum 1999a (book) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| 11 | Veenstra and Lomas 1998 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||||||

| 10 | Kawachi et al 1997 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 9 | Wilkinson 1996 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |||||||||||

| 8 | Kennedy et al 1996 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | Wilkinson 1994 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||

| 6 | Cohen and Syme 1985* | 1 | 8 | 19 | 11 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | Orth‐Gomer and Johnson 1987 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | House et al1982 | 4 | 3 | 13 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Berkman and Syme 1979 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Cassel 1976 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | Durkheim |

*Edited volume.

Texts 9 and 10 act as bridging texts between the income inequality and the social relations literatures. In Unhealthy Societies, Wilkinson, in his discussion of the psychosocial causes of illness, cites Durkheim's work on social cohesion and health. Kawachi does not cite Durkheim, but his article provides a link between the income inequality literature and the social support literature through his citation of Berkman and Syme. Citations to the social support and health literature occur infrequently and usually in passing in main path texts appearing after Wilkinson and Kawachi. Because these texts act as important bridges between social support and income inequality research, the manner in which they interpret the social support literature for studies on income inequality and health is central to the way in which the concept of social capital has taken shape in public health, and thus critical for our understanding of how network approaches have become marginalised in public health research on social capital.

Three seminal texts

Our analysis confirms the divide between the social support and income inequality literatures and captures the ways in which those literatures are linked. In contrast with Szreter and Woolcock, who describe the work of Wilkinson as leading a break from the social support literature, we highlight how Wilkinson helped bridge the two literatures. In so doing, we return to our questions of how the concept of social capital was translated into public health research and how the particular form that it took was influenced by the epistemological context of social epidemiology at that time. We suggest that the translation of social capital was driven by the need for a psychosocial mechanism that might explain the effects of income inequality at an ecological level. To support this argument, we focus on three seminal (main path) public health texts on social capital: the work by Kennedy et al,32 by Wilkinson,7 and by Kawachi et al.8

Against the background of the burgeoning research on the effects of income inequality on health, Kennedy and colleagues argue that “the mechanisms underlying the association between income distribution and mortality are poorly understood.”32 During the earlier period of what Susser and Susser refered to as “black box” epidemiology,47 it was sufficient to identify a statistical association between an exposure and an outcome. Researchers governed by the black box paradigm could establish the relation of exposure to outcome without referring to intervening factors.47 Yet, by 1996, this paradigm had been replaced by an eco‐epidemiological paradigm that focused attention on causal pathways of disease at the societal level.48 While Kennedy and colleagues did not provide an empirically based answer to the question of how income distribution affects health, they do suggest that “income distribution may be a proxy for other social indicators, such as the degree of investment in human capital,” and that “communities that tolerate large degrees of inequality in income may be the same ones that tend to underinvest in social goods….”32

In Unhealthy Societies, Wilkinson advances his argument that developed societies are characterised by an epidemiological dynamic in which population health and wellbeing no longer relate primarily to economic development but to the quality of the social environment.7 Wilkinson seeks to explain why “Healthy, egalitarian societies are more socially cohesive.”7 He argues that the causal mechanism must be psychosocial in nature, not material, because the effects of income distribution on health predominate in developed, affluent societies.7,39 To clarify how psychosocial mechanisms might operate, Wilkinson turns to Durkheim's work on social cohesion and social integration. According to Wilkinson, the link between income distribution and health might be found in the literature on social relationships and health, especially in studies of the negative health effects of lower community involvement and the lack of social contact.7 But, he continues, the literature on social relationships and health is only partially able to explain the effects of income inequality on health as such studies operate only at the individual level, and are thus unable to answer how income inequality (an ecological level variable) influences population health.

To make the link at the ecological level, Wilkinson invokes Putnam's definition of social capital but he does not argue that social capital is itself the mechanism that explains the association between income distribution and health. Instead, Wilkinson sees social cohesion playing this part. Social capital—networks, norms, and trust—influences social cohesion, but it is not the main factor on the income inequality‐mortality pathway. The concept of social capital only assumes this more direct role in the work of Kawachi and colleagues.

In “Social capital, income inequality, and mortality,” Kawachi and colleagues place social capital directly on the income inequality‐mortality pathway by testing the hypothesis that income inequality leads to a “disinvestment in social capital” that, in turn, influences state level variations in mortality. Social capital operates as the intervening social mechanism.8 Kawachi defines social capital “as the features of social organization, such as civic participation, norms of reciprocity, and trust in others, that facilitate cooperation for mutual benefit” citing Putnam and Coleman in support.8 Both Putnam and Coleman included networks in their definitions of social capital, but the term is absent from Kawachi's version. Instead, referring to the social support and health literature, Kawachi argues that social networks are the individual level counterpart to the ecological level variable social capital. Whereas studies on social support and health show the importance of social relationships for the health of individuals, studies on social capital and health would, according to Kawachi et al, parallel such work in their demonstration of the population health effects of community level trust, participation, and reciprocity.

Thus, in reviewing the epistemological context in which the concept of social capital first appears, it is apparent from these three texts that its emergence in public health was: (1) driven initially by the search for a mechanism that might help explain the association of income distribution with mortality; (2) the mechanism had to be psychosocial in character; and (3) the psychosocial mechanism had to operate at the ecological level, a level that is conventionally seen in public health in geographical or spatial terms.2

Public health's translation of social capital borrowed predominately from the communitarian approach to social capital.9,10 Best represented in the work of Putnam, this approach provided an avenue for social epidemiologists to speak of social capital as an ecological‐level mechanism. Moreover, in social capital's celebration of community,49 Putnam's formulation appeals more broadly to public health's community advocacy side. Putnam acknowledges the importance of networks, but his measurement of social capital relied primarily on aggregated individual level data on trust, reciprocity, and civic participation, which was readily available, and not on relational network data. Given this, networks were excluded from public health's subsequent operationalisation of social capital. The growing body of evidence that trust, reciprocity, and civic participation mattered for health further legitimated this conceptualisation of social capital.

What this paper adds

Few studies have responded to the call for a “sociology of epidemiology” that emphasises the way in which citation practices in public health research shape epidemiological research and practice.

This review of the social capital literature in public health uses a genealogical approach rooted in the citation patterns of relevant texts to show the particular way in which the concept emerged within the public health domain and the consequences that this has had on public health research on social capital.

Discussion

The way in which social capital was translated into public health has had important consequences for the shape and direction that social capital research has taken. We would like to discuss four. Firstly, as a broad umbrella term that might cover a variety of social phenomena including attitudes, behaviours, power, and collective action, the concept of social capital has reduced the range of phenomena that social epidemiologists need to explain. The concept of social capital was originally offered as a psychosocial mechanism that might explain the effects of income inequality on population health. Yet, until recently, social capital has been its own “black box.” The finding that social capital, measured as trust or civic participation, was associated with or predicted certain health outcomes seemed self explanatory rather than requiring greater interrogation. Only recently have public health scholars begun to examine more closely the mechanisms by which social capital might operate or the various forms that it might assume.13,16 This has also entailed calls for greater specification in definitions and measures of social capital, and more frequent discussion of the notion of bridging and bonding social capital.17

Policy implications

Greater introspection of public health practice and research helps improve the constructs, measures, and methods that researchers use to study the social factors influencing population health. Ultimately, better research practice leads to more comprehensive and better informed policy recommendations.

Secondly, the communitarian approach assumes that social capital is a property of communities or neighbourhoods. Recent research has challenged this assumption by demonstrating that neighbourhood co‐residence does not mean people within those neighbourhoods have the same “stocks” of social capital50 and that associational involvement is not implicitly embedded in neighbourhood locales.51 The communitarian approach to social capital obscures the effects of intra‐community dynamics and extra‐neighbourhood social connections on population health.

Thirdly, network approaches to the study of social capital and health have been lost in the translation of social capital in public health. Social capital became the ecological level counterpart to what was viewed as individual level network studies, in the manner of the conventional social support literature. The distinction between social capital as a community level feature and social networks as an individual level attribute that runs through the early social capital literature has helped marginalise network approaches to social capital in public health research. Whether we are referring to network approaches that focus more on the network structure itself or on the resources accessed through those networks, such as Lin's social resource theory, the way in which social capital has been translated into public health obfuscates the utility and relevance of network approaches for the study of social capital and health.

Finally, the marginalisation of network approaches and the concern to establish a psychosocial mechanism to explain the effects of income distribution reinforced the false dichotomy between psychosocial and material determinants of health. Understood in network terms as the resources to which people have access through their social relationships,52 social capital is not a psychosocial mechanism in itself but a composite of psychosocial and material elements. Resources may be material, such as money or a car, or psychosocial in nature, such as social support. To contend that social capital is merely a psychosocial mechanism is to conflate the communitarian approach that has come to dominate public health with all approaches to the study of social capital. Furthermore, the broader literature on social capital shows a concern to address the question of socially structured unequal access to resources. For example, Bourdieu's analysis of the fungibility of the different forms of capital—economic, social, cultural, and symbolic—is grounded in the “structure and dynamics of differentiated societies.”53,54 The processes by which the various forms of capital change shape is thus influenced by macrolevel or upstream social factors.

Conclusion

The concept of social capital is nearing its 10th birthday in public health. The communitarian guise that social capital first assumed in public health was one influenced by certain epistemological concerns. This guise continues to frame the debates and issues that arise in discussions of the concept in public health. Szreter's and Woolcock's effort to rehabilitate social capital research through the promotion of a “three‐dimensional” approach goes a long way in advancing a network orientation, and fostering a renewed empirical rigour to social capital research.17 Yet, they still give primacy to normative, communitarian issues such as mutual respect and trust among citizens or between citizens and the state. In advancing the normative and associational side of the concept of social capital, Szreter and Woolcock de‐emphasise the importance of measuring resource access and evaluating how such access is socially structured. A social network approach to social capital provides a toolbox of concepts, methods, and measures for assessing both the quantity and quality of social relationships and the resources to which individuals and groups have access and are able to mobilise through those ties. It is an approach that can be situated into broader macro‐level frameworks for understanding the effects of class, gender, race, and age on the composition and structure of individual and group networks, and health outcomes. Furthermore, we would suggest that a network approach to social capital would encourage the development of public health research that sees networks as social contexts that influence the behaviour and practices of individuals. Such a perspective could promote a comprehensive understanding of networks that complements current public health research that focuses primarily on ego‐networks and individual health outcomes. Developing social network approaches to social capital in public health is not an example of relabelling terminology. It is the key to a full translation and conceptualisation of social capital into public health research and practice.

Acknowledgements

We thank Almaymoon Mawji for his assistance in collecting and assembling the citation articles.

Footnotes

* The list of 227 texts included in the study is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Funding: early work was supported through funding from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research in the form of a postdoctoral fellowship (to SM) and senior scholarships (to AS and PH). The later work of SM was supported through funding from Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec and the Strategic Training Program in public and population health research of Québec (a CIHR‐Québec Population Health Research Network partnership).

Competing interests: none declared.

References

- 1.Williams S J. Theorising class, health, and lifestyles: Can Bourdieu help us? Sociol Health Illn 199517577–604. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frohlich K, Corin E, Potvin L. A theoretical proposal for the relationship between context and disease. Sociol Health Illn 200123776–797. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams G H. The determinants of health: structure, context, and agency. Sociol Health Illn 200325131–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porta M, Alvarez‐Dardet C. Epidemiology: bridges over (and across) roaring levels. J Epidemiol Community Health 199852605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce N, Davey Smith G. Is social capital the key to inequalities in health? Am J Public Health 200393122–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan G A. Inequality in income and mortality in the United States: analysis of mortality and potential pathways. BMJ 1996312999–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson R.Unhealthy societies. London: Routledge Press, 1996

- 8.Kawachi I, Kennedy B, Lochner K.et al Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am J Public Health 1997871491–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navarro V. A critique of social capital. Int J Health Serv 200232423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore S, Shiell A, Hawe P.et al The privileging of communitarian ideas: citation practices and the translation of social capital into public health research. Am J Public Health 2005951330–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muntaner C, Lynch J, Hillemeier M.et al Economic inequality, working‐class power, social capital, and cause‐specific mortality in wealthy countries. Int J Health Serv 200232629–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearce N, Davey‐Smith G. Is social capital the key to inequalities in health? Am J Public Health 200493122–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veenstra G. Location, location, location: contextual and compositional health effects of social capital in British Columbia, Canada. Soc Sci Med 2005602059–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muntaner C, Lynch J, Davey‐Smith G. Social capital, disorganized communities, and the third way: understanding the retreat from structural inequalities in epidemiology and public health. Int J Health Serv 200131213–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fassin D. Social capital, from sociology to epidemiology critical analysis of a transfer across disciplines. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 200351403–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpiano R. Toward a neighborhood resource‐based theory of social capital for health: Can Bourdieu and sociology help? Soc Sci Med 200662165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szreter S, Woolcock M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int J Epidemiol 200433650–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Portes A. Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu Rev Sociol 1998241–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.NCBI PubMed Overview. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query/static/overview.html (accessed Jan 2003)

- 20.Whittaker J, Courtial J P, Law J. Creativity and conformity in science: titles, keywords and co‐word analysis. Soc Stud Sci 198919473–496. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman L. Centrality in social networks. Soc Networks 19791215–239. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawe P, Webster C, Shiell A. A glossary of terms for navigating the field of social network analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 200458971–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hummon N, Doreian P, Freeman L. Analyzing the structure of the centrality‐productivity literature created between 1948 and 1979. Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization 199011459–480. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hummon N, Carley K. Social networks as normal science. Soc Networks 19931571–106. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hummon N, Doreian P. Connectivity in a citation network: the development of DNA theory. Soc Networks 19891139–63. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hummon N, Doreian P. Computational methods for social network analysis. Soc Networks 199012273–288. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Putnam R.Making democracy work. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993

- 28.Coleman J.Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990

- 29.Putnam R. Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of Democracy 1995665–78. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coleman J. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 198894S95–120. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berkman L, Syme S L. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine‐year follow‐up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol 1979109186–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy B P, Kawachi I, Prothrow‐Stith D. Income distribution and mortality: cross sectional ecological study of the Robin Hood index in the United States. BMJ 19963121004–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkinson R. Income distribution and life expectancy. BMJ 1992304165–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durkheim E.Suicide: a study in sociology. New York: The Free Press, 1966

- 35.Cassel J. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance. Am J Epidemiol 1976104107–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.House J S, Robbins C, Metzner H L. The association of social relationships and activites with mortality: prospective evidence from the Tecumseh community health study. Am J Epidemiol 1982116123–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orth‐Gomer K, Johnson J V. Social network interaction and mortality: a six year follow‐up study of a random sample of the Swedish population. J Chron Dis 198740949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen S, Syme S L. eds. Social support and health. New York: Academic Press, 1985

- 39.Wilkinson R. The epidemiological transition: from material scarcity to social disadvantage? Daedalus 199412361–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veenstra G, Lomas J. Home is where the governing is: social capital and regional health governance. Health Place 199951–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baum F.The new public health: an Australian perspective. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1998

- 42.Baum F. Social capital: Is it good for your health? Issues for a public health agenda. J Epidemiol Community Health 199953195–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynch J, Due P, Muntaner C.et al Social capital—Is it a good investment strategy for public health? J Epidemiol Community Health 200054404–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lynch J, Davey‐Smith G, Kaplan G.et al Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ 20003201200–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawe P, Shiell A. social capital and health promotion: a review. Soc Sci Med 200051871–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harpham T, Grant E, Thomas E. Measuring social capital within health surveys: key issues. Health Policy Plan 200217106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Susser M, Susser E. Choosing a future for epidemiology: ii. from black box to chinese boxes and eco‐epidemiology. Am J Public Health 199686674–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Susser M, Susser E. Choosing a future for epidemiology: i. eras and paradigms Am J Public Health199686668–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Portes A. The two meanings of social capital. Sociol Forum 2000151–12. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gattrell A, Popay J, Thomas C. Mapping the determinants of health inequalities in social space: Can Bourdieu help us? Health Place 200410245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Veenstra G, Luginaah I, Wakefield S.et al Who you know, where you live: social capital, neighbourhood and health. Soc Sci Med 2005602799–2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin N.Social capital: a theory of social structure and action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001

- 53.Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson JG, ed. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York: Greenwood, 1985241–328.

- 54.Bourdieu P, Wacquant L D.An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1992