Abstract

Aim

To assess the effectiveness of a sexual risk reduction intervention in the Russian narcology hospital setting.

Design, setting and participants

This was a randomized controlled trial from October 2004 to December 2005 among patients with alcohol and/or heroin dependence from two narcology hospitals in St Petersburg, Russia.

Intervention

Intervention subjects received two personalized sexual behavior counseling sessions plus three telephone booster sessions. Control subjects received usual addiction treatment, which did not include sexual behavior counseling. All received a research assessment and condoms at baseline.

Measurements

Primary outcomes were percentage of safe sex episodes (number of times condoms were used ÷ by number of sexual episodes) and no unprotected sex (100% condom use or abstinence) during the previous 3 months, assessed at 6 months.

Findings

Intervention subjects reported higher median percentage of safe sex episodes (unadjusted median difference 12.7%; P = 0.01; adjusted median difference 23%, P = 0.07); a significant difference was not detected for the outcome no unprotected sex in the past 3 months [unadjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.6, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.8-3.1; adjusted OR 1.5, 95% CI 0.7-3.3].

Conclusions

Among Russian substance-dependent individuals, sexual behavior counseling during addiction treatment should be considered as one potential component of efforts to decrease risky sexual behaviors in this HIV at-risk population.

Keywords: Alcohol, behavioral intervention, heroin, HIV prevention, narcology hospital, randomized controlled trial, Russia, sex risk behaviors, substance dependence

INTRODUCTION

Russia has one of the fastest-growing acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemics in the world, with an estimated 860 000 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected people in 2003 [1]. In St Petersburg, the prevalence of HIV increased 100-fold (0.013-1.3%) from 1998 to 2002 [2,3]. Initially the Russian HIV epidemic was almost exclusively among injection drug users (IDUs) [4]; however, concern exists that HIV is expanding into the general population via sexual transmission [1,2,5]. Among sex workers, HIV seroprevalence is estimated at 5-15% overall, but 48% in those who also inject drugs [2].

Alcohol use, highly prevalent in Russia [6,7], may increase high-risk sexual behaviors (e.g. multiple sex partners, unprotected sex) among IDUs and alcohol-dependent individuals [8-11]. Among female drug users, increased alcohol consumption has been associated with sexual HIV risk-taking behavior [12]. Furthermore, animal models suggest that alcohol consumption plays a permissive role for HIV replication, as the resultant higher viral loads may increase risk of transmission [13,14].

In addition to the association between alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior, extensive evidence demonstrates that users of other substances may also be commonly involved in high-risk sex [15-19]. Use of stimulants is associated with increased sexual risk behavior such as unprotected sex, multiple partners and selling sex in the United States and Russia [16,17,19]. Studies with Russian IDUs have found that multiple partners, having an IDU sex partner and unprotected sex, particularly with steady sex partners, is common [18,20-22]. Selling sex for drugs, money, goods or shelter is also reported commonly among IDUs in St Petersburg [16,18].

Behavioral interventions to reduce risky sex are an essential component to HIV prevention and are even more critical in the absence of a cure or vaccine. Interventions that focus on personal risk reduction have been shown to be effective in reducing sexual risk behaviors and diseases in developed as well as developing countries [23-25]. A study of meta-analyses of HIV prevention interventions showed that programs targeting drug users can be successful at reducing sexual risk [26]. Several moderators were identified as contributing to intervention efficacy, including separate gender sessions, didactic lecture, self-control/coping skills and greater number of intervention techniques used. Although sex risk behaviors can be different based on HIV serostatus [27,28], few data have been reported that describe whether response to a particular sexual risk reduction intervention depends upon HIV status. Successful prevention interventions among HIV-positive individuals share many of the following characteristics: based on behavioral theory, targeted HIV transmission behaviors, delivered by health-care providers or counselors to individuals, time-intensive, delivered in a familiar medical or service environment, provided skills building or addressed other HIV-related issues [24]. As yet, relatively few controlled trials of behavioral interventions have demonstrated efficacy in reducing sexual HIV risk among substance users in treatment settings [29-31]. Although many of the individual studies included in a meta-analysis on this topic had positive effect estimates, most failed to reach statistical significance on their own [32].

Current HIV prevention efforts in Russia address sexual risk reduction mainly in mass media promotion of condom use and encouragement of HIV counseling and testing [33-35]. A limited number of non-governmental organizations disseminate information on HIV prevention among IDUs [35]. Treatment of opioid dependence with methadone or buprenorphine, proven effective at preventing HIV among IDUs [36], is illegal in Russia [35,37]. Regional narcology hospitals play a central role in Russia's efforts to address alcohol and drug dependence but have not addressed HIV aggressively.

Reducing risky sexual behaviors among alcohol- and drug-dependent individuals is an HIV intervention strategy that has not, as yet, been pursued in Russia [16,38]. We tested such an intervention among narcology patients in St Petersburg, Russia.

METHODS

Study design

The Russian PREVENT (Partnership to Reduce the Epidemic Via Engagement in Narcology Treatment) study was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) [39] that recruited men and women with alcohol and/or drug dependence from two substance abuse treatment facilities near St Petersburg, Russia [i.e. Leningrad Regional Center for Addictions (LRCA) and the Medical Narcology Rehabilitation Center (MNRC)]. Narcology hospitals are a standard treatment setting for drug- and alcohol-dependent individuals in eastern Europe. Hospitalization is typically 3-4 weeks, in which initial addiction treatment follows detoxification.

Trained physician research associates approached patients after initial detoxification, assessed eligibility, offered participation and conducted assessments. Eligibility criteria were the following: age 18 years and older; a primary diagnosis of alcohol or drug dependence; no alcohol or other abused substances for at least 48 hours; reported unprotected anal or vaginal sex in the past 6 months; willingness to undergo HIV testing per standard narcology hospital protocols or previous diagnosis of HIV infection; and provision of reliable contact information (i.e. a home telephone number, an address within 150 km of St Petersburg and one friend or family contact). Patients not fluent in Russian or with cognitive impairment based on the research associates' judgement were excluded. Participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. The Institutional Review Boards of Boston Medical Center and St Petersburg Pavlov State Medical University approved this study.

Subject assessment

Baseline assessments occurred after randomization; however, subjects and assessors were blinded to intervention group at this point. Follow-up assessments occurred 3 months and 6 months after enrollment. All follow-up assessments were conducted with patients after discharge from the hospital. Assessment data included demographics, behavioral intentions for condom and needle use, Center for Epidemiologic studies Depression (CES-D) Scale for depressive symptoms [40], history of sexually transmitted diseases, HIV testing and disclosure, ICD-10 substance dependence diagnosis and the Short Form 36 (SF-36) General Health Survey [41]. Questions about HIV sex and drug risk behaviors came from multiple sources: the RESPECT study [42] (e.g. ‘in the past 3 months, how many times have you had vaginal sex with your primary partner; how many of those times did you use a condom?’); the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB) [43] sex and drug use subscales (e.g. ‘in the past 6 months, how often were you paid to have sex?’); the Timeline Follow-back survey (TLFB) [44,45] (e.g. total number of drinks on each day in the past 30 days, number of times condoms used with vaginal sex on each day in the past 30 days); and the Addiction Severity Index- Lite [46]. All instruments were translated from English to Russian for this study (e.g. RESPECT and TLFB), unless already available in Russian (e.g. RAB). Risk behaviors were assessed by both face-to-face interviews and to promote truth-telling through an Audio Computer-Assisted Self Interviewing (ACASI) system at baseline and 6 months. The 3-month assessment, administered via the telephone, included RESPECT and RAB questions about HIV risk behaviors. The 6-month assessment was identical to the baseline and occurred at the narcology hospitals within a 5-7-month window after enrollment. All interviews were conducted in Russian by trained personnel not involved in interventions and who were blinded to treatment group. Subjects were compensated the equivalent of US$5, $5 and $30 for the baseline and 3- and 6-month assessments, respectively, and all received 30 condoms at baseline.

Study treatments

Subjects were assigned randomly to either the Russian PREVENT program (intervention group) or standard addiction treatment (control group).

Russian PREVENT program

The Russian PREVENT intervention was based on the Brief Counseling model used in Project RESPECT, a prevention program tested in US sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics, which demonstrated reduction in risky sexual behaviors and STDs [42]. RESPECT involved a two-session HIV prevention counseling intervention used with HIV testing to increase participants' perception of personal risk, support participant-initiated changes and identify small, achievable steps towards reducing personal risk. The Russian PREVENT study was modified from Project RESPECT by the US-Russian team to meet the needs of the Russian narcology hospital setting and patients. Modifications included the following: (1) enrollment of known HIV-positive as well as negative participants (all patients were HIV tested as part of the narcology program); (2) emphasis on basic HIV prevention and transmission knowledge due to relatively low access to such information among this St Petersburg population; (3) inclusion of booster telephone sessions to sustain programmatic effects by providing longer-term support; and (4) provision of skills-building on HIV-related risk reduction for sexual and injection drug use behaviors for both HIV-infected and uninfected individuals. The modifications yielded longer PREVENT sessions than RESPECT (30-60 versus 20 minutes). Sessions occurred at the narcology hospitals and involved provision of HIV test results, discussion of personal risk and risk reduction and creation of a behavioral change plan. The first session included a personal assessment of HIV risk, discussion of HIV risk perceptions and negotiation of a personalized risk reduction plan. The second session was held within 1 week of session 1 to allow sufficient time for HIV test results to return. The interventionist provided the HIV test results and reviewed the risk reduction plan (i.e. promotion of safer sex via condom skills, sexual-negotiation skills building, developing positive attitudes regarding safer sex and emphasizing the role of alcohol). Additional content was covered as appropriate for HIV-infected subjects (e.g. HIV disclosure) and injection drug users (e.g. clean needle use). The same inter-ventionist delivered both intervention sessions to an individual. Booster sessions after hospital discharge occurred via telephone monthly for 3 months, when interventionists checked in and updated participants' personal long-term risk reduction goals and plans. Typically, the same interventionist delivered the in-hospital and booster call sessions, but for a minority (approximately 5%) another interventionist conducted the booster calls.

Control group program

Subjects randomized to the control condition received usual addiction treatment at the narcology hospital, including HIV testing, but no sexual behavior counseling. Those known to be HIV-infected or who tested positive received one 20-minute HIV post-test counseling session with the study interventionists, even though this was not standard care in the narcology hospitals. This counseling for these control individuals with HIV infection included creation of risk reduction goals and referral to an HIV care program. All control subjects were contacted for study checks, but not counseled, at the booster time-points. Both control and intervention subjects received 30 condoms.

Training of interventionists

Interventionists (two psychiatrists and a psychologist trained in HIV and addiction) were trained by US collaborators with HIV and substance use intervention experience (A. R., J. H. S.); they were trained about both general risk reduction interview techniques and the Russia-adapted RESPECT intervention. The lead inter-ventionist (V. E.) underwent an initial training in English in the United States. A subsequent 3-day training in St Petersburg with all interventionists using simultaneous translation allowed multiple role-playing sessions to be observed and critiqued by the behavioral psychologist (A. R.).

Quality assurance procedures

The following efforts were conducted to ensure fidelity of the Russian PREVENT intervention: (1) 20% of each interventionist's subjects were selected randomly to have their sessions observed by another interventionist. The observer documented whether the curriculum content and activities were covered and how well the interventionists achieved session objectives. All observed sessions demonstrated 100% coverage of the curriculum material and activities. In 90% of observed cases, interventionists were described as implementing the program at an ‘excellent’ level in a variety of domains (e.g. providing HIV risk assessment and counseling, establishing rapport). (2) Interventionists participated in monthly research team meetings to discuss programmatic difficulties; no major problems with fidelity were noted, although there were difficulties in completing the booster session observations. (3) Participants completed a brief survey to assess perceptions of the utility of the program in helping to reduce their HIV/STD risk, the competence of the inter-ventionist and whether they would recommend the program to others at the hospital. All responded that they found the program somewhat or very informative and helpful for reducing their HIV risk and in answering questions about HIV and that they would recommend the program to other patients at the hospital. The research team members discussed the results of these quality assurance assessments regularly.

Primary outcomes

The two primary outcomes of interest were (i) percentage of safe sex episodes and (ii) no unprotected sex (yes/no) during the past 3 months. These outcomes were assessed at the 6-month follow-up visit by ACASI. Percentage of safe sex episodes, a continuous variable, was defined as the percentage of times condoms were used out of the total number of sexual episodes (anal and vaginal intercourse) in the past 3 months. No unprotected sex was defined as either 100% condom use during anal and vaginal intercourse or sexual abstinence.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included (i) number of unsafe sex episodes (i.e. no condom use during anal or vaginal sex; people who did not have sex were coded as having no unsafe sex episodes); and (ii) any condom use during the past 3 months by ACASI at the 6-month follow-up. Sex risk behaviors at the 3-month telephone follow-up were also examined: percentage of safe sex episodes, no unprotected sex and any condom use.

Randomization and blinding

Random allocation of subjects was accomplished using a computer-generated list of random numbers using permuted blocks stratified according to gender and dependence diagnosis. Research associates assigned subjects to the intervention or control condition immediately after completion of informed consent. Three strata of dependence diagnosis were used: alcohol, drug or dual (alcohol and drug). The research associate who assessed outcomes and contacted subjects to arrange follow-up appointments remained blinded to treatment assignments throughout follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using logistic regression and median regression models to adjust for possible group differences at baseline. All outcome analyses used the intention-to-treat principle, two-sided tests and a significance level of 0.05, with SAS/STAT software version 9.1. The observed sample sizes at 6 months allowed us 80% power to detect a minimum 25% difference (assuming the observed proportion of 29% for control group) in no unprotected sex using a two-sided χ2test with continuity correction.

Subject enrollment and baseline characteristics

Of the 329 patients screened, 181 met inclusion criteria and provided consent to participate. Eighty-seven subjects were randomized to the control and 94 to the intervention treatment group. Participants were 75% male, median age 30 years and 15% HIV-infected. Dependence diagnoses were 60% alcohol, 32% heroin and 8% dual. Among alcohol-dependent and dual-diagnosis subjects (n = 123), the median number of drinks per day reported at baseline was 5.4 [interquartile range (IQR): 2.6-10.0]. Among heroin-dependent and dual-diagnosis subjects (n = 73), 97% reported injection drug use in the past 6 months. At baseline, the two groups were similar in all examined characteristics except ‘reported buying or selling sex’ [31 (36%) control subjects versus 18 (19%) intervention subjects, P = 0.02]. HIV seroprevalence among the IDU subjects was 35%.

Follow-up and receipt of intervention

Follow-up was 90% (162/181) at 3 months and 80% (144/181) at 6 months, with no differential follow-up between randomization groups. Subjects lost to follow-up at the 6-month assessment were generally similar to those who were followed, except that those lost were more likely to be married (54% versus 28%, P = 0.003) and have a primary sex partner (95% versus 71%, P = 0.003). Due to loss to follow-up or subject death, 77 intervention and 67 control group subjects were included in the 6-month analyses. Of the 94 intervention subjects, 50 received the entire intervention (two in-hospital sessions and three monthly booster calls), while 44 received a partial intervention. Fifty-one, 21, 12 and 10 subjects received three, two, one and no booster sessions, respectively.

RESULTS

Primary outcomes

Percentage of safe sex

Russian PREVENT intervention subjects had a higher median percentage of safe sex episodes than control subjects at the 6-month follow-up visit (unadjusted median difference in percentage of safe sex episodes 12.7, P = 0.01) in unadjusted analyses (Table 1). A significant intervention effect remained even after adjusting for baseline differences in report of sex trade (adjusted median difference in percentage of safe sex episodes 29%, P = 0.01). Although the percentage of safe sex episodes reported at baseline did not differ significantly between groups, secondary analyses controlling for this potential confounding factor were conducted. Using this model, the treatment effect diminished and became marginally significant (median difference 22.8%, P = 0.07).

Table 1.

Sex behaviors of narcology hospital patients in the Russian Partnership to Reduce the Epidemic Via Engagement in Narcology Treatment (PREVENT) randomized controlled trial at 6 months post-randomization (n = 144)

| Sex behavior measures during the past 3 months | Unadjusted median group differences (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted median group differences*(95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of safe sex episodes†‡ | 12.7 (0.0,36.6) | 0.01 | 22.8 (−1.5,47.0) | 0.07 |

| Number of unsafe sex episodes† | −2.5 (−7.0,0.0) | 0.04 | −3.5 (−7.2,0.1) | 0.06 |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) proportions | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | |||

| Period of no unprotected sex†§ | 1.6 (0.8,3.1) | 0.18 | 1.5 (0.7,3.3) | 0.26 |

| Any condom use¶ | 2.5 (1.1,5.5) | 0.03 | 3.7 (1.5,8.9) | 0.004 |

Adjusted for baseline report of sex trade involvement and baseline value of outcome.

n = 66 control; n = 73 intervention.

Safe sex episode defined as condom use during anal or vaginal intercourse (yes/no).

No unprotected sex defined as condom use for 100% of sexual episodes (anal and vaginal) with all partners or abstinence for past 3 months (yes/no).

n = 67 control; n = 77 intervention. Median number of total sex episodes; control = 28; intervention = 20. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

No unprotected sex

The intervention group had a higher odds of reporting no unprotected sex compared to controls, although the difference was not statistically significant [unadjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.6 for intervention versus controls, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.8-3.1; P = 0.18]. The results were similar after adjusting for sex trade and reporting no unprotected sex (past 3 months) at baseline (adjusted OR = 1.5 for intervention versus controls, 95% CI 0.7- 3.3, P = 0.26). Among the 48 subjects who reported no unprotected sex, nine of these (19%) were sexually abstinent (five controls, four intervention group).

Secondary outcomes

Unsafe sex episodes

At the 6-month follow-up, control subjects reported a higher median number of unsafe sex episodes in the past 3 months compared to the intervention subjects (unadjusted median difference - 2.5, P = 0.04). However, the treatment effect became borderline significant after adjusting for baseline number of unsafe sex episodes and sex trade (adjusted median difference - 3.5, P = 0.06).

Any condom use

The intervention subjects had a higher odds of reporting any condom use during the past 3 months (unadjusted OR 2.5 for intervention versus controls, 95% CI 1.1-5.5, P = 0.03). The treatment effect on any condom use persisted after adjusting for sex trade and any condom use at baseline [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 3.7, 95% CI: 1.5-8.9, P < 0.01].

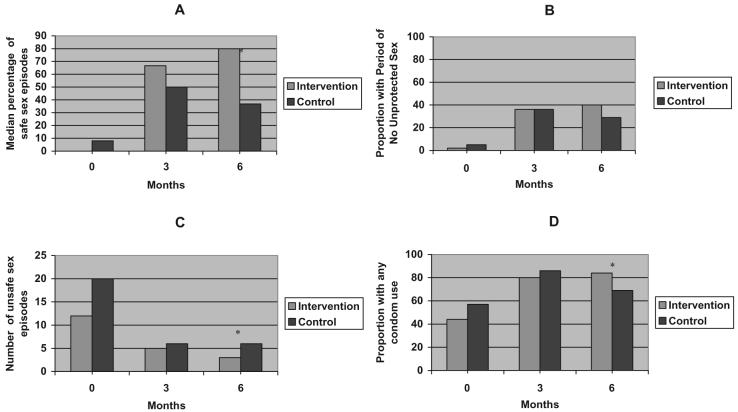

No treatment differences were detected at the 3-month follow-up. However, both the intervention and control groups had marked improvements in the percentage of safe sex episodes, no unprotected sex and any condom use between baseline and the 3-month follow-up. While the intervention group appeared to maintain or improve their safe sex behaviors at the 6-month follow-up, the control group appeared to worsen (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The effect of the Partnership to Reduce the EpidemicVia Engagement in NarcologyTreatment (PREVENT) intervention on median percentage of safe sex episodes (A), percentage with periods of no unprotected sex (B), number of unsafe sex episodes (C) and percentage with any condom use (D). * P < 0.05, unadjusted analysis

In exploratory subgroup analyses stratified by dependence diagnosis (alcohol versus heroin), the intervention effect appeared stronger among alcohol-dependent subjects compared to heroin-dependent subjects [median percentage of safe sex: (alcohol: 90% versus 30%, P < 0.01, heroin: 74% versus 59%, P = 0.49; proportion no unprotected sex: alcohol: 48% versus 22%, P = 0.01, heroin: 29% versus 32%, P = 0.85)]. Additional exploratory analyses stratified by depressive symptoms suggest that the effect of the intervention on percentage of safe sex and no unprotected sex was stronger among those with less depressive symptoms (data not shown). PREVENT was designed to focus upon sex risk behaviors rather than substance use; alcohol and heroin dependence were already being addressed by the narcology hospital clinicians. However, in recognition of the importance of substance use in the transmission of HIV we performed post-hoc exploratory analyses, which showed no significant differences between groups in injection drug use [OR = 1.2 (0.6, 2.5), P = 0.64] or risky alcohol consumption [0.6 (0.2, 2.1), P = 0.38] at the 6-month follow-up.

DISCUSSION

The results of the Russian PREVENT trial demonstrate that an HIV prevention intervention targeting sexual behaviors of alcohol and drug users is feasible in inpatient substance abuse treatment settings and suggest that it is effective in increasing any condom use. A clinically important intervention effect was observed in the hypothesized direction for the other primary outcome, a 3-month period of no unprotected sex; however, the effect was not statistically significant.

Identification of an effective sexual risk reduction program in Russia is particularly valuable, as heterosexual transmission is the next anticipated phase of the HIV epidemic driven heretofore by injection drug use [47]. A limited number of HIV behavioral interventions are documented to be effective in this region of the world; few address sexual risk, and none address sex risk in individuals with addictions [16,48]. The Russian narcology hospital yielded a cohort with risky sexual behavior, confirming the need and providing a setting for an effective sexual risk reduction intervention addressing this high-risk population.

The Russian PREVENT intervention was developed based upon an existing model demonstrated to be efficacious in US STD clinic patients [42] and recommended for dissemination by HIV prevention experts [49,50]. Few effectiveness studies have investigated whether an adapted STD prevention model can produce desired outcomes in new settings [50]. Factors such as inadequate adherence to the originally evaluated programs or inadequate tailoring to the target population make these studies difficult to conduct [50]. Contributing to the success of our adaptation was the likelihood that the adapted model was able to remain faithful to the core elements of the original efficacious model while still being culturally and contextually appropriate.

The intervention appeared to be more effective in alcohol-dependent patients than in drug-dependent patients. This finding is surprising, given the approximate 35% HIV prevalence among IDUs in the narcology hospitals and previous research suggesting that knowledge of positive HIV serostatus reduces unsafe sex [27]. Of the 15 control participants who received brief post-test counseling due to their positive HIV infection status, 13 were IDUs; this exposure may have attenuated the difference in this relatively small subgroup analysis.

Russia's mass media campaign to encourage condom use may be valuable. However, agencies such as the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that national HIV prevention efforts include both mass efforts (e.g. media) and intensive interventions targeted towards those at greatest risk for infection and transmission [51,52]. Targeted strategies that tailor interventions to personal HIV risk using a ‘teachable moment’ (i.e. a time of heightened personal risk perception, such as during an HIV or STD test) are believed to be particularly effective [51,53]. Such ‘intensive’ prevention interventions combined with HIV testing, such as the Russian PREVENT, may be particularly advantageous in populations who have very high HIV risk (e.g. substance-dependent people) [54,55].

Interestingly, exploratory analyses suggested that the intervention may be more effective at increasing the percentage of safe sex and no unprotected sex among those with less depressive symptoms. Future interventions should address the relationship of psychiatric comorbidities on HIV risk reduction.

When comparing the results of the current study with the RESPECT study, we observed similar magnitudes of effect for the outcome no unprotected sex; however, our study did not find a statistically significant effect on this outcome while the original study of 5758 subjects did. In RESPECT, subjects in the intervention arms were more likely to report no unprotected sex compared to the control arm at the 6-month visit [39% enhanced counseling versus 34% didactic messages; relative risk (RR) 1.14; 95% CI, 1.01-1.28; and 39% brief counseling versus 34% didactic messages; RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00- 1.25]. The lack of statistical significance in the current study may be an issue of statistical power.

This study's findings are consistent with US research indicating that patients in detoxification centers are at high risk for STDs, including HIV, and that sexual risk reduction programs in these settings can be efficacious [31,32,56]. A recent meta-analysis of US research demonstrated that more effective HIV prevention programs were comprised of comprehensive and fairly intensive program ‘packages’, including community-based out-reach, substance abuse treatment, sterile syringe access and enhanced HIV/STD counseling and testing [32]. It is important to explore the utility of additional HIV prevention approaches for substance users that take into account the limited resources and existing systems available—as is the case for this study in Russia. This study provides insights not only on potential interventions for the Russian narcology hospital context; it also contributes to the growing work on the utility of brief risk reduction interventions for any patient in addiction treatment. Research up to this point has suggested some success, but has been inconclusive due to the small number of efficacy and effectiveness studies [57,58]. Notably, no previous comparable work has been conducted in eastern Europe.

At 3 months, there appeared to be an increase in safe sex in the control as well as the intervention group. Assessments conducted by telephone rather than ACASI showed improvements in sex risk behaviors in both the control and intervention groups (Fig. 1). This may have been due to factors such as exposure of the control participants to the extensive initial assessment, including an ACASI, availability of condoms (distributed to all subjects) or regression to the mean. Despite early changes, the control subjects' behavior returned toward baseline in the second 3 months, while the intervention group continued to improve. The findings of delayed sexual risk reduction effects observed in this study are consistent with previous HIV intervention research [59-62], and may perhaps be attributed to greater opportunity for intervention participants to change behavior over time [61].

The study had some major strengths: demonstration that the PREVENT intervention could be implemented in two Russian narcology hospitals supports the strong likelihood for translation of this research into practice, and ability to engage this high-risk population at a ‘reachable moment’ (e.g. addiction treatment) in addition to a ‘teachable moment’. In St Petersburg, talented and well-trained personnel were available to provide the intervention, and similar personnel may exist elsewhere in these clinical settings. Another study strength was the heterogeneity of the research subjects in terms of gender, HIV status and substance use, supporting the notion that these results may be generalizable to the narcology patient population elsewhere.

The trial also had some limitations. Although impressive changes were reported using state-of-the-art methodology for assessing behavior change, behaviors were self-reported and participants could not be blinded to intervention status, allowing the possibility of social desirability bias. Although we were not able to obtain objective biological outcomes, we attempted to limit this bias by using ACASI technology and by using research associates who were not involved in delivering the intervention to assess outcomes. We were unable to address the number of safe sex acts with partners with discordant HIV serostatus, as we did not ask the subjects to identify the HIV serostatus of their sex partners. Also, the narcology hospital setting has a disproportionate number of men and a minority of HIV-infected patients, thus we were unable to address gender or HIV status in stratified analyses. Additionally, the international setting of this behavioral intervention study presented certain challenges to assessing the fidelity of the intervention as adapted to the Russian setting. Finally, our study was not designed to detect small-to-moderate treatment differences with high power. Moreover, adjustment for additional covariates resulted in further reduction of power. Nevertheless, all primary and secondary outcomes show clinically important differences in the hypothesized direction and the adjusted results are marginally significant for percentage of safe sex events and periods of unsafe sex, and statistically significant for any condom use.

In summary, this randomized controlled trial suggests that adaptation of a pragmatic, HIV prevention intervention may reduce risky sexual behaviors in substance-dependent patients attending Russian narcology hospitals. Dissemination of this effective intervention should be considered as a component of a broad strategy aimed at reducing HIV infections in eastern Europe and other settings.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the interventionists and research associates at the Russian narcology hospitals for their contributions to the study and Erika Edwards MPH, of the Data Coordinating Center at Boston University School of Public Health, for her critical reviews of the manuscript. We would also like to express our gratitude to Marina Tsoy for her work translating all study documents. These individuals received compensation from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant for their contributions. Grant support for this study came from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), NIH: R21-AA014821 (HIV Prevention Partnership in Russian Alcohol Treatment—NCT00183118; NIH AA014821) and K24-AA015674 (Impact of Alcohol Use on HIV Infection—in United States and Russia). This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov through the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Russian Federation. 2006 Available at: http://www. unaids.org/en/Regions_Countries/Countries/ russian_federation.asp (accessed 8 March 2006)

- 2.World Health Organization . Russian Federation: Summary Country Profile for HIV/AIDS Treatment Scale up. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. Available at: http:// www.who.int/3by5/support/june2005_rus.pdf (accessed 27 March 2006) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krupitsky E, Zvartau E, Karandashova G, Horton NJ, Schoolwerth KR, Bryant K, et al. The onset of HIV infection in the Leningrad region of Russia: a focus on drug and alcohol dependence. HIV Med. 2004;5:30–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dehne KL, Pokrovskiy V, Kobyshcha Y, Schwartlander B. Update on the epidemics of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union. AIDS. 2000;14:S75–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamers FF, Downs AM. HIV in central and eastern Europe. Lancet. 2003;361:1035–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12831-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/ 9241562722_(425KB).pdf (accessed 16 May 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zohoori N, Blanchette D, Popkin B. Monitoring Health Conditions in the Russian Federation: The Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey 1992-2004. University of North Carolina; North Carolina: 2005. Available at: http://www.cpc. unc.edu/rlms/papers/health_04.pdf# (accessed 16 May 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avins AL, Woods WJ, Lindan CP, Hudes ES, Clark W, Hulley SB. HIV infection and risk behaviors among heterosexuals in alcohol treatment programs. JAMA. 1994;271:515–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahler J, Yi D, Sacks M, Dermatis H, Stebinger A, Card C, et al. Undetected HIV infection among patients admitted to an alcohol rehabilitation unit. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:439–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagnall G, Plant M, Warwick W. Alcohol, drugs and AIDS-related risks: results from a prospective study. AIDS Care. 1990;2:309–17. doi: 10.1080/09540129008257746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leigh B, Temple M, Trocki K. The relationship of alcohol use to sexual activity in a U.S. national sample. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:1527–35. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rees V, Saitz R, Horton NJ, Samet JH. Association of alcohol consumption with HIV sex- and drug-risk behaviors among drug users. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21:129–34. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoltz DA, Nelson S, Kolls JK, Zhang P, Bohm RP, Murphey-Corb M, et al. Effects of in vitro ethanol on tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by blood obtained from simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagby GJ, Zhang P, Purcell JE, Didier PJ, Nelson S. Chronic binge ethanol consumption accelerates progression of simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1781–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benotsch EG, Somlai AM, Pinkerton SD, Kelly JA, Ostrovski D, Gore-Felton C, et al. Drug use and sexual risk behaviours among female Russian IDUs who exchange sex for money or drugs. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15:343–7. doi: 10.1177/095646240401500514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozlov AP, Shaboltas AV, Toussova OV, Verevochkin SV, Masse BR, Perdue T, et al. HIV incidence and factors associated with HIV acquisition among injection drug users in St Petersburg, Russia. AIDS. 2006;20:901–6. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000218555.36661.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raj A, Saitz R, Cheng DM, Winter M, Samet JH. Associations between alcohol, heroin, and cocaine use and high risk sexual behaviors among detoxification patients. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:169–78. doi: 10.1080/00952990601091176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaboltas AV, Toussova OV, Hoffman IF, Heimer R, Verevochkin SV, Ryder RW, et al. HIV prevalence, socio-demographic, and behavioral correlates and recruitment methods among injection drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:657–63. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000220166.56866.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mansergh G, Purcell DW, Stall R, McFarlane M, Semaan S, Valentine J, et al. CDC consultation on methamphetamine use and sexual risk behavior for HIV/STD infection: summary and suggestions. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:127–32. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhodes T, Judd A, Mikhailova L, Sarang A, Khutorskoy M, Platt L, et al. Injecting equipment sharing among injecting drug users in Togliatti City, Russian Federation: maximizing the protective effects of syringe distribution. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35:293–300. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200403010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Somlai AM, Kelly JA, Benotsch E, Gore-Felton C, Ostrovski D, McAuliffe T, et al. Characteristics and predictors of HIV risk behaviors among injection-drug-using men and women in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:295–305. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.5.295.23873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takacs J, Amirkhanian YA, Kelly JA, Kirsanova AV, Khoursine RA, Mocsonaki L. ‘Condoms are reliable but I am not’: a qualitative analysis of AIDS-related beliefs and attitudes of young heterosexual adults in Budapest, Hungary, and St. Petersburg Russia. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2006;14:59–66. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merson MH, Dayton JM, O'Reilly K. Effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions in developing countries. AIDS. 2000;14:68–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, Passin WF, Rama SM, Herbst JH, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. 2006;20:143–57. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Card JJ, Benner T, Shields JP, Feinstein N. The HIV/AIDS Prevention Program Archive (HAPPA): a collection of promising prevention programs in a box. AIDS Educ Prev. 2001;13:1–28. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.1.1.18926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noar SM. Behavioral interventions to reduce HIV-related sexual risk behavior: review and synthesis of meta-analytic evidence. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:335–53. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–53. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985- 1997. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1397–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D'Aunno T, Vaughn TE, McElroy P. An institutional analysis of HIV prevention efforts by the nation's outpatient drug abuse treatment units. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40:175–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibson DR, McCusker J, Chesney M. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in preventing HIV risk behaviour in injecting drug users. AIDS. 1998;12:919–29. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199808000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semaan S, Des Jarlais DC, Sogolow E, Johnson WD, Hedges LV, Ramirez G, et al. A meta-analysis of the effect of HIV prevention interventions on the sex behaviors of drug users in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:S73–S93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prendergast ML, Urada D, Podus D. Meta-analysis of HIV risk-reduction interventions within drug abuse treatment programs. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:389–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burrows D, Sarankov I. [A decrease in harm: a new concept for Russian public health] Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1999;1:107–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burrows D. Strategies for dealing with HIV/AIDS in the former Soviet Union. Dev Bull. 2000;52:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Open Society Institute Drugs, AIDS, and Harm Reduction: How to Slow the HIV Epidemic in Eastern Europe and Former Soviet Union. 2001 Available at: http://www.soros.org/ initiatives/health/focus/ihrd/articles_publications/ publications/drugsaidshr_20010101 (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 36.Metzger D, Woody GE, McLellan A, O'Brien C, Druley C, Navaline H, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus serocon-version among intravenous drug users in and out of treatment: an 18-month prospective follow-up. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:1049–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan LE, Metzger DS, Fudala PJ, Fiellin DA. Decreasing international HIV transmission: the role of expanding access to opioid agonist therapies for injection drug users. Addiction. 2005;100:150–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ksobiech K, Somlai AM, Kelly JA, Gore-Felton C, Benotsch E, McAuliffe T, et al. Demographic characteristics, treatment history, drug risk behaviors, and condom use attitudes for U.S. and Russian injection drug users: the need for targeted sexual risk behavior interventions. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:111–20. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1686-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:401. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ware J, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Jr, Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. JAMA. 1998;280:1161–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Navaline HA, Snider EC, Petro CJ, Tobin D, Metzger D, Alterman AI, et al. Preparations for AIDS vaccine trials. An automated version of the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB): enhancing the assessment of risk behaviors. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:281–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Carey KB, Cohen MM, Wickramasinghe SM. Reliability of the timeline follow-back sexual behavior interview. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20:25–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02893805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sobell L, Sobell M. Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB) Users' Manual. Addiction Research Foundation; Toronto, Canada: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLellan A, Luborsky L, Woody G, O'Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karon JM, Fleming PL, Steketee RW, De Cock KM. HIV in the United States at the turn of the century: an epidemic in transition. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1060–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo RF, Cofrancesco J., Jr Injection drug use and HIV transmission in Russia. AIDS. 2006;20:935–6. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000218561.74779.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Institutes of Health National Institutes of Health Fiscal Year 2006 Plan for HIV-related Research. 2004 Available at: http://www.oar.nih.gov/public/pubs/fy2006/ 00_Overview_FY2006.pdf (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 50.Solomon J, Card JJ, Malow RM. Adapting efficacious interventions: advancing translational research in HIV prevention. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29:162–94. doi: 10.1177/0163278706287344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sumartojo E, Carey JW, Doll LS, Gayle H. Targeted and general population interventions for HIV prevention: towards a comprehensive approach. AIDS. 1997;11:1201–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.World Health Organization . Policy and Programming Guide for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care among Drug Users. WHO Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2005. Available at: http:// wwwint/hiv/pub/idu/iduguide/en/ (accessed 24 October 2006) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Myers T, Worthington C, Haubrich DJ, Ryder K, Calzavara L. HIV testing and counseling: test providers' experiences of best practices. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:309–19. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.5.309.23821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) World Health Organization (WHO) UNAIDS/WHO Policy Statement on HIV Testing. 2004 Available at: http:// wwwint/hiv/pub/vct/statement/en/ (accessed 24 October 2006)

- 55.World Health Organization. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Advocacy Guide: HIV/AIDS Prevention among Injection Drug Users. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2004. Available at: http:// www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/iduadvocacyguide/en/ index.html (accessed 24 October 2006) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Avins AL, Lindan CP, Woods WJ, Hudes ES, Boscarino JA, Kay J, et al. Changes in HIV-related behaviors among heterosexual alcoholics following addiction treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stein MD, Anderson B, Charuvastra A, Maksad J, Fried-mann PD. A brief intervention for hazardous drinkers in a needle exchange program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96:1725–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Braverman PK, Fong GT. HIV/STD risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:440–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, DiFonzo K, Simpson D, Austin J, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. AmJPrevMed. 2001;21:84–92. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raj A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Martin B, Cabral H, Navarro A, et al. Is a general women's health promotion program as effective as an HIV-intensive prevention program in reducing HIV risk among Hispanic women? Public Health Rep. 2001;116:599–607. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.6.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Villarruel AM, Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS. A randomized controlled trial testing an HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:772–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]