Abstract

The waterpipe, known in many cultures under different shapes and names (e.g. hookah, shisha, narghile), is a centuries-old tobacco use method that is witnessing a worldwide surge in popularity. This popularity is most noticeable amongst youths, and is surpassing cigarette smoking among this group in some societies. Many factors may have contributed to the recent waterpipe spread including the introduction of sweetened/flavored waterpipe tobacco (known as Maassel), its reduced-harm perception, the thriving café culture, mass media and the internet. The passage of smoke through water on its way to the smoker underlies much of the common misperception that waterpipe use is less harmful than cigarettes. The health/addictive profile of waterpipe compared to cigarettes is largely un-researched and is likely to be influenced by the properties of smoke, duration and frequency of use, type of tobacco used, volume of smoke inhaled, and the contribution of charcoal. Still, the accumulation of evidence about the harmful and addictive potential of waterpipe use is outpacing the public health response to this health risk. A timely public health and policy action is needed in order to curb the emerging waterpipe smoking epidemic.

Keywords: waterpipe, narghile, shisha, hookah, public health, policy

Introduction

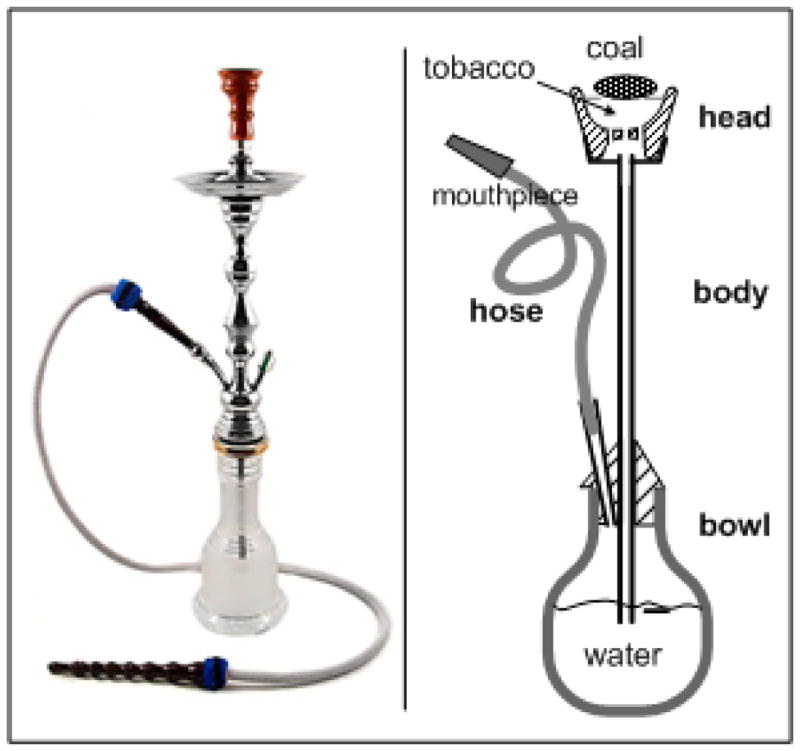

The waterpipe, known in many cultures under different shapes and names (e.g. hookah, shisha, narghile), is a centuries-old tobacco use method that is traditionally associated with Middle Eastern societies1,2. Waterpipe use is often practiced in social settings, and is looked at as a pleasurable pastime in the company of friends and family3,4. The name “waterpipe” signifies a defining feature; the passage of smoke through water prior to inhalation by the smoker (Figure). This feature underlies much of the common misperception that waterpipe use is less harmful than cigarettes1. After a gradual decline in this practice throughout the 20th century, the waterpipe witnessed a sudden surge in popularity in the nineties. This period coincided with the introduction of manufactured sweetened/flavored waterpipe tobacco (known as Maassel). Maassel’s aromatic mild smoke, wide variety and availability, and simplification of the waterpipe preparation process were perhaps critical for the renewed appeal of the waterpipe5. At the same time, the internet and other transnational media (e.g. satellite TV) took care of commercializing and glamorizing this practice, particularly among youths5,6. Combined, manufactured Maassel, the reduced-harm perception, the thriving café culture, and mass media have perhaps created conditions for a perfect storm that sparked the global waterpipe epidemic.

Figure.

Actual waterpipe (left) and schematic (right) showing main parts (courtesy of Dr. Alan Shihadeh).

Spread and patterns of waterpipe use

There is no epidemiological estimate of the size of the global waterpipe epidemic, yet its widespread use is evident from numerous news and professional responses highlighting its emergence in many societies regardless of their ethnic composition or level of development1,2. This has prompted several international health and specialty organizations to react to this emerging threat with alert reports including the World health Organization, American Cancer Society, American Lung Association, Action on Smoking or Health (ASH, UK), German Cancer Research Center, and the French National Anti-Tobacco Agency.

Studies have also begun to document the spread of this tobacco use method within and outside its natural cradle in the Middle East. Rarely seen among young people a decade ago, recent studies from the Middle East indicate that this practice may have surpassed cigarette smoking amongst youngsters. The Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) involving more than 90,000 students (13–15 years) from 20 countries in the Middle East provides the best compelling argument for such a trend. In a region dominated by cigarette and waterpipe use, the GYTS showed tha0t past month non-cigarette tobacco use (mostly waterpipe) was reported by 15.6% of boys and 9.9% of girls compared to 6.7% of boys and 3.2% of girls reporting cigarette smoking7. Specific studies of waterpipe use among schoolchildren in Middle Eastern societies confirm this trend, whereby waterpipe use is becoming the leading tobacco use method among adolescents8–10. Studies among youths in the US provide a good sense of how far this tobacco use method has spread in record time. For example, results from the US-GYTS involving 6,594 students (grades 6 thru 12) in Arizona shows that 7% of 12th graders reported past month waterpipe use8, while past month waterpipe use among college students has reached 10–20% of the surveyed11–14.

The socio-cultural acceptability of waterpipe use is threatening the long-held immunity of Middle Eastern girls/women to smoking. Studies demonstrate that waterpipe use by girls/women in the Middle East is not subject to the same social stigma surrounding cigarette smoking. For example, in a study of 2443 adolescents (average age 15 years) from private and public schools in Lebanon, waterpipe use did not show the usual male predominance seen with cigarette smoking, and more waterpipe users were open about their practice with their parents compared to cigarette smokers15. The reduced-harm misperception, moreover, can drive certain groups of women, such as pregnant women, to either use or replace cigarettes with the waterpipe during pregnancy. Thus, for pregnant women in Lebanon, waterpipe use during pregnancy can be associated with a misperception of its reduced harmful potential16. The effect of increased tobacco use by women is likely to project on their future risk of lung cancer, heart disease, and other tobacco-related illnesses, similar to the delayed epidemic of cigarette-induced morbidity/mortality documented in western societies.

Another demographic trend in waterpipe use is related to the age of initiation, whereby studies are showing that waterpipe use is beginning at an ever-younger age7, and at times being the first method of experimenting with tobacco. For example, a survey of 1,671 Arab American adolescents found that by the age of 14 years more adolescents had tried waterpipe than cigarettes (23% vs. 15%, respectively), and that many of those had their first waterpipe before the age of 10 years17. A recent study among a representative sample of 1st and 5th year medical students at the University of Damascus-Syria shows that the age of initiation of waterpipe among 1st year students commenced earlier than among 5th year students, which points at the changing age-dynamics of waterpipe initiation18.

In contrast to cigarettes, most waterpipe users are intermittent smokers, which may reinforce their perception of reduced harm and addiction19. Another important use difference between cigarettes and the waterpipe is that waterpipe use is typically practiced in a social setting, whether in cafés/restaurants or in the company of friends and family19. In the café/restaurant setting the waterpipe is served time and again to customers, usually without proper sanitation or cleaning, raising the issue of infectious disease spread20. Home users usually purchase their own waterpipe and accessories, and in western societies this is increasingly done through the internet21.

Health and addictive effects of waterpipe use

The health/addictive profile of waterpipe compared to cigarettes is largely un-researched and is likely to be influenced by - the properties of smoke, - duration and frequency of use, - type of tobacco used, - volume of smoke inhaled, and - the contribution of charcoal. While access and setting requirements for waterpipe preclude its use with high frequency like cigarettes, the amount of smoke inhaled in a single waterpipe session (lasting an hour on average) can equal that produced by 100 or more cigarettes22. Emerging evidence suggests that waterpipe use is an efficient mode of delivery of some of the major addictive and harmful tobacco-related substances to smokers, such as nicotine and CO. For example, exposure to CO - a major cardiovascular risk of smoking - among waterpipe users leads to an increase in expired air CO that is several folds what is expected from a single cigarette1,23,24. Studies of smoke constituents indicate that waterpipe smoke contains large amounts of known carcinogens such as hydrocarbons and heavy metals25,26. For example, a single waterpipe smoking session delivers approximately 50 times the quantities of carcinogenic 4- and 5-membered ring PAHs compared to a single cigarette smoked using the FTC protocol26. Awaiting quality case-control and cohort studies of the health consequences of waterpipe use, studies have already documented for example the risks associated with waterpipe use by pregnant women to their newborns in terms of low birth weight and health indicators27,28.

Exposure to waterpipe-associated toxicants is not restricted to users; nearby non-smokers may also be exposed. Recent studies show that mainstream smoke from a waterpipe contains high levels of fine particles - a known cardio-respiratory hazard - and that a considerable amount of these particles (e.g. PM2.5) are emitted by waterpipe smokers to the surrounding air, reaching levels compared to those associated with cigarette smoking29,30.

As for the dependence-inducing nicotine, a recent review shows that daily waterpipe use is associated with nicotine absorption rate equivalent to smoking 10 cigarettes/day31. Such a dosage of nicotine can arguably sustain chemical addiction among waterpipe users even with a predominantly intermittent use pattern. Dependence among waterpipe users is also evidenced by their self-perception of being hooked, repeated use despite known risks, abstinence effects that are suppressed by subsequent use, behavioral adaptations to insure access, and failed quit attempts19,24,32. Circumstantial evidence suggests that quitting waterpipe smoking can be easier than giving up cigarettes, but this needs to be considered in light of a generally lower interest in quitting among waterpipe users19,24,33–35.

Dependence among waterpipe users is likely to be influenced by use characteristics, and to involve a unique social domain that needs to be understood and addressed in order to treat it19. Preliminary evidence suggests that the transformation from social to solitary use can be an important dependence-related step among waterpipe users19,36. Waterpipe’s unique use features can influence our ability to adapt tools used for the assessment of dependence in cigarette smokers to the waterpipe. For example, because most waterpipe use is intermittent, within a social setting, and is time-consuming, the questions relating to time of first waterpipe used in the morning, or number of waterpipes smoked daily, or the waterpipe/day that would be the hardest to give up (equivalent to the items used in the Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence) may not be applicable to the majority of waterpipe users19. Tools to measure and treat dependence incorporating waterpipe’s unique use aspects are currently being researched, and will hopefully contribute to the development of effective cessation interventions for waterpipe users36,37.

Public health implications of the waterpipe epidemic

The waterpipe epidemic is likely to be just beginning, as many young people worldwide continue to be influenced by its positive social-utility experiences, as well as misperceptions about its harmful/addictive potentials13,19,35,38. This prediction is reinforced by the slow public health response to the waterpipe epidemic in terms of large-scale social marketing campaigns, prevention and cessation interventions, and other evidence-based tobacco control activities. Just as concerning, is the emerging evidence that waterpipe use can be a conduit to cigarette smoking either among tobacco naïve or cigarette quitters3,35,38,39. On the other side of the equation, media outlets with disguised ownership that promote the waterpipe by minimizing the evidence about its negative public health potential are emerging40.

Based on the experience with the cigarette epidemic, such trends embody much of the elements of a public health emergency that requires timely research and policy attention. Currently, some national tobacco control policies still do not clearly address this tobacco use method including clean indoor air policies, access to minors, visible warning labels, and the prohibition of deceptive descriptors (e.g. many Maassel packs say 0% tar and 0.5% nicotine)1,4,22,36,41,42. Recently, many waterpipe café/lounge owners are trying to exploit the scarcity of evidence about the hazardous potential of waterpipe use to non-smokers, or local laws with specific provisions for “retail tobacco establishments” to be exempted from clean indoor air policies41–43. The good news is that we have the facts needed to start policy action for the waterpipe today, while research continues to build the evidence base for a comprehensive waterpipe control plan22. Otherwise, we may be destined to reap the human cost of our inaction.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wasim Maziak is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant R01 DA024876-01.

References

- 1.Maziak W, Ward KD, Soweid RA, Eissenberg T. Tobacco smoking using a waterpipe: a re-emerging strain in a global epidemic. Tob Control. 2004;13:327–333. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knishknowy B, Amitai Y. Water-pipe (narghile) smoking: an emerging health risk behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):e113–e119. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammal F, Mock J, Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Maziak W. A pleasure among friends: how narghile (waterpipe) smoking differs from cigarette smoking in Syria. Tob Control. 2008 doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatrad R, Gatrad A, Sheikh A. Hookah smoking. BMJ. 2007;335(7609):20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39227.409641.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rastam S, Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Maziak W. Estimating the beginning of the waterpipe epidemic in Syria. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maziak W, Eissenberg T, Rastam S, Hammal F, Asfar T, Bachir ME, Fouad MF, Ward KD. Beliefs and attitudes related to narghile (waterpipe) smoking among university students in Syria. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(9):646–54. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warren CW, Jones NR, Eriksen MP, Asma S Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) collaborative group. Patterns of global tobacco use in young people and implications for future chronic disease burden in adults. Lancet. 2006;367(9512):749–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Roueiheb Z, Tamim H, Kanj M, Jabbour S, Alayan I, Musharrafieh U. Cigarette and waterpipe smoking among Lebanese adolescents, a cross-sectional study, 2003–2004. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(2):309–14. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varsano S, Ganz I, Eldor N, Garenkin M. Waterpipe tobacco smoking among school children in Israel: frequency, habit and attitudes. Harefuah. 2003;142:736–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gadalla S, Aboul-Fotouh A, El-Setouhy M, Mikhail N, Abdel-Aziz F, Mohamed MK, Kamal Ael A, Israel E. Prevalence of smoking among rural secondary school students in Qualyobia governorate. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2003;33(3 Suppl):1031–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coffman AS, Walsh M. Hookah use gaining in popularity among youth. Square One. 2007;4(3) Available at www.azteppdata.org/docs/squareone/4-3_YouthHookahUse.pdf.

- 12.Eissenberg T, Ward KD, Smith-Simone S, Maziak W. Waterpipe tobacco smoking on a U.S. College campus: prevalence and correlates. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(5):526–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith SY, Curbow B, Stillman FA. Harm perception of nicotine products in college freshmen. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(9):977–82. doi: 10.1080/14622200701540796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Primack BA, Sidani J, Agarwal A, Shadel WG, Donny E, Eissenberg T. Prevalence of and associations with waterpipe tobacco smoking among college students. Ann Behav Med. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9047-6. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Roueiheb Z, Tamim H, Kanj M, Jabbour S, Alayan I, Musharrafieh U. Cigarette and waterpipe smoking among Lebanese adolescents, a cross-sectional study, 2003–2004. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(2):309–14. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaaya M, Jabbour S, El-Roueiheb Z, Chemaitelly H. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of argileh (water pipe or hubble-bubble) and cigarette smoking among pregnant women in Lebanon. Addict Behav. 2004;29(9):1821–31. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice VH, Weglicki LS, Templin T, Hammad A, Jamil H, Kulwiki A. Predictors of Arab American Adolescent Tobacco Use. Merril Plamer Quarterly. 2006;52(2):327–342. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2006.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almerie MQ, Matar HE, Salam M, Morad A, Abdelal M, Maziak W. Cigarettes & waterpipe smoking among medical students in Syria: a cross-sectional study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008 in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maziak W, Eissenberg T, Ward KD. Patterns of waterpipe use and dependence: implications for intervention development. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2005;80(1):173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steentoft J, Wittendorf J, Andersen JR. Tuberculosis and water pipes as source of infection. Ugeskrift for Laeger. 2006;168(9):904–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(2):393–8. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization Study group on Tobacco Product Regulation (TOBREG) Waterpipe tobacco smoking: Health effects, research needs and recommended action by regulators [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Nachef WN, Hammond SK. Exhaled carbon monoxide with waterpipe use in US students. JAMA. 2008;299(1):36–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Rastam S, Asfar T, Mzayek F, Fouad MF, et al. The tobacco epidemic in Syria. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl):24–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shihadeh A. Investigation of mainstream smoke aerosol of the argileh water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol. 2003;41:143–52. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sepetdjian E, Shihadeh A, Saliba NA. Measurement of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in narghile waterpipe tobacco smoke. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(5):1582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nuwayhid IA, Yamout B, Azar G, Kambris MA. Narghile (hubble-bubble) smoking, low birth weight, and other pregnancy outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(4):375–83. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamim H, Yunis KA, Chemaitelly H, Alameh M, Nassar AH National Collaborative Perinatal Neonatal Network Beirut, Lebanon. Effect of narghile and cigarette smoking on newborn birthweight. BJOG. 2008;115(1):91–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monn Ch, Kindler P, Meile A, Brändli O. Ultrafine particle emissions from waterpipes. Tob Control. 2007;16(6):390–3. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.021097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maziak W, Rastam S, Ibrahim I, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe associated particulate matter emissions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(3):519–23. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neergaard J, Singh P, Job J, Montgomery S. Waterpipe smoking and nicotine exposure: a review of the current evidence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(10):987–94. doi: 10.1080/14622200701591591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Factors related to frequency of narghile (waterpipe) use: the first insights on tobacco dependence in narghile users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76(1):101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yunis K, Beydoun H, Nakad P, Khogali M, Shatila F, Tamim H. Patterns and predictors of tobacco smoking cessation: a hospital-based study of pregnant women in Lebanon. Int J Public Health. 2007;52(4):223–32. doi: 10.1007/s00038-007-6087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward KD, Hammal F, VanderWeg MW, Eissenberg T, Asfar T, Rastam S, et al. Are waterpipe users interested in quitting? Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(1):149–56. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Gray JN, Srinivas V, Wilson N, Maziak W. Characteristics of U.S. waterpipe users: a preliminary report. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(12):1339–46. doi: 10.1080/14622200701705019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salameh P, Waked M, Aoun Z. Waterpipe smoking: Construction and validation of the Lebanon Waterpipe Dependence Scale (LWDS-11) Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(1):149–58. doi: 10.1080/14622200701767753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Interventions for waterpipe smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(4):CD005549. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005549.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward KD, Vander Weg MW, Relyea G, Debon M, Klesges RC. Waterpipe smoking among American military recruits. Prev Med. 2006;43(2):92–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asfar T, Weg MV, Maziak W, Hammal F, Eissenberg T, Ward KD. Outcomes and adherence in Syria's first smoking cessation trial. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(2):146–56. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Sacred Narghile. www.sacrednarghile.com/en/index.php.

- 41.American Lung Association. Tobacco Policy Trend Alert AN EMERGING DEADLY TREND:WATERPIPE TOBACCO USE. [accessed 1/8/2008];2007 Available at www.slati.lungusa.org/alerts/Trend%20Alert_Waterpipes.pdf.

- 42.The BACCHUS Network. Reducing Hookah Use, A Public Health Challenge For the 21st Century. Availabale at www.tobaccofreeu.org/pdf/HookahWhitePaper.pdf.

- 43.Shisha 200 times worse than a cigarette say Middle East experts. ASH news release: Embargo: 00:01 27th March 2007. Available at www.ash.org.uk/ash_4q8eg0ft.htm