Abstract

Aim

The goals of this paper are to evaluate whether drinking practices among peers mediates the relationship between a low level of response (LR) to alcohol and a person’s heavier drinking and alcohol-related problems in 12-to-14-year-olds.

Design

Correlations and structural equation models (SEMs) were used to test a hypothesized model of the relationships among key variables in adolescents from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), a longitudinal birth cohort study in Bristol, England.

Participants

These included 688 boys (40.4%) and girls who were offspring of the pregnant women who had been selected as ALSPAC participants in 1991 and 1992. The offspring were interviewed at about age 13, and those who had ever consumed a full drink filled out the Self-Report of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) questionnaire indicating the number of drinks required for up to four effects early in their drinking histories. A higher number of drinks required for effects indicated a low level of response (LR) per drink consumed.

Findings

The SEM explained 58% of the variance of the alcohol pattern, and had good fit characteristics. A low LR was related to heavier drinking and more alcohol problems both directly and as partially mediated by drinking in peers. The model performed well across the narrow age range, and applied equally well in boys and girls.

Conclusions

The perceived drinking practices of peers is a potentially important mediator of how a low LR to alcohol relates to drinking practices during early adolescence. The findings may be useful in developing approaches to prevent heavier drinking in this young group.

Keywords: Alcohol, Genetics, Environment, Structural Equation Models

Introduction

Genes contribute to between 40% and 60% of the risk for alcohol use disorders (AUDs), operating in large part through several different intermediate characteristics, or phenotypes, including a low level of response (LR) to alcohol [1, 2]. Regarding LR, it is hypothesized that a low response per drink produces a need for more drinks to get desired effects, which then contributes to higher levels of consumption. This, in turn, may enhance the risk for alcohol-related problems, including alcohol abuse and dependence [2, 3]. A low LR to alcohol has been documented to relate to heavier drinking in animal models and humans as early as age 12 [4–6]. LR is genetically-influenced with estimated heritabilities of 40%-to-60% [7, 8], and a low LR predicts later heavy drinking and alcohol problems in adults and adolescents [7, 9–11].

However, by itself, a low LR cannot fully explain how heavy drinking and associated problems develop. Therefore, efforts have been made to understand more about the pathways through which a low LR contributes to such an enhanced risk [10, 12–14]. Tests of the overall hypothesized LR-based model have shown that a low LR relates to what a person expects to occur during drinking periods, with these expectations contributing to heavier drinking, perhaps through the belief that heavier drinking and alcohol problems are acceptable behaviors [12, 13, 15–17]. In these models the impact of LR on alcohol-related outcomes was also mediated through sub-optimal coping approaches, especially the use of alcohol to alleviate stress, with problematic coping practices contributing to the risk for higher levels of alcohol intake and related problems [10, 13, 18–20]. The models also supported a relationship between alcohol expectancies and the use of alcohol to cope with stress [12, 21].

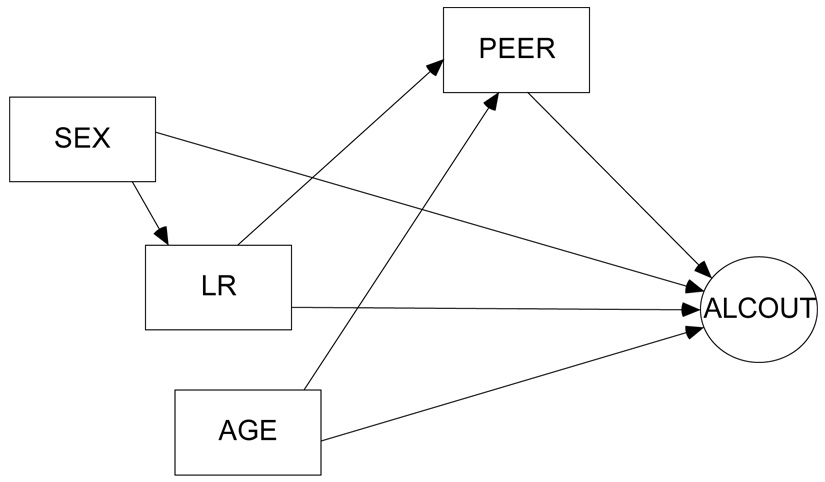

The initial LR-related evaluations based on the Social Information Processing Model predicted that in a heavy-drinking society people with a low LR to alcohol and higher alcohol intake are likely to develop a bias in their social information processing that encourages them to accept heavy drinking as an expected behavior, which then enhances the probability they choose friends with a similar bias [22, 23]. Similar to elements that may contribute to other models (e.g., Deviance Prone Models), the selection of the peer group is also consistent with Peer Cluster Theory [24], and the subsequent reinforcement of heavy drinking behaviors relates to social developmental and social learning models [17, 24–28]. In our models, sex has been used as a covariate, with girls expected to have less severe alcohol problems, and, reflecting their size and alcohol metabolism, a lower number of drinks for effects [1, 29]. Age was also covaried reflecting higher risks for heavier drinking and problems with increasing age [30]. These elements of the hypothesized model are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized LR-based model with a low level of response (LR) to alcohol hypothesized as relating directly to alcohol-related outcomes (ALCOUT) as well as indirectly through heavier drinking in peers (PEER). SEX is hypothesized to be directly related to both LR and ALCOUT. AGE is hypothesized to be related directly to ALCOUT as well as indirectly through PEER.

To date, however, evaluations of peer drinking practices as a potential mediator of the relationship between LR and alcohol-related outcomes has not been supported by model testing in older teenagers and adults [10, 12, 13]. These included results from 297 middle-age men where peer drinking practices contributed to the prediction of alcohol-related problems, but were not related to the LR to alcohol [12]. An evaluation of 113 13-to-24-year-olds (mean age 19 years) also revealed a relationship between peer drinking and a person’s alcohol practices, but, contrary to the hypothesis, no strong link between LR and peer drinking practices [13]. The performance of peer drinking variables in these models could reflect the older age of the samples tested, as the influences of peers on drinking patterns have been hypothesized to be most prominent among relatively young adolescents [31, 32]. In addition, the evaluations of the possible role of peer drinking as a partial mediator between a low LR to alcohol and drinking practices have been carried out in higher socioeconomic stratum, U.S.-based families.

The current analyses use data on LR, peer drinking practices, and alcohol-related outcomes in 12-to-14-year-old boys and girls from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) in Bristol, England. The goal is to test the hypothesis that in a young population, a person’s perception of drinking in peers will mediate the relationship between a low LR to alcohol and heavier drinking and alcohol problems.

Methods

Subjects

ALSPAC is a longitudinal, population-based birth cohort study that began with 14,501 pregnant women resident in Avon, England in 1991 and 1992 [33]. Data were regularly collected via self-completion questionnaires sent to the mothers since their enrollment during pregnancy and through the child’s early years. In addition, a subset of approximately 8,000 children from the original offspring have been followed since the age of seven using hands-on assessments. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Law and Ethics Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committees as described on the ALSPAC website: http://www.alspac.bris.ac.uk. The current analyses are based on the subgroup of 688 13-to-14-year-old offspring who were drinkers and who were studied in person in the ongoing age 13/14-year evaluation (also known as a “clinic”).

The 688 drinking adolescents had an average age (with standard deviation) of 13.2 (0.43) years, with a range of 12-to-14. Males comprised 40.4% of the sample, and 98.3% were Anglo-European, with the remainder fairly equally divided between Black-Caribbean, Indian-Pakistani, and Chinese.

Regarding drinking-related variables, the age of first drink was 12.0 (1.01), the average SRE First Five score was 2.1 (1.37), and subjects endorsed 1.6 (0.84) items on the SRE. The average maximum number of drinks consumed was 3.8 (3.04), the usual frequency in the prior six months was 1.7 (2.62) drinking days per month, the average quantity per drinking day was 2.2 (1.78) drinks, and a usual quantity per week was 2.0 (2.76). In this population, 23.1% reported ever having experienced an alcohol-related life problem, including: 10% who ever felt the need to set limits on drinking; 8% each who ever needed more alcohol to get an effect (i.e., tolerance), had blackouts, or had parental complaints about drinking; and 3% to 4% each who ever wanted to stop or cut down on drinking, used alcohol in a circumstance that was hazardous, went to school intoxicated or hung over, had a legal problem related to drinking, or who reported an alcohol-related fight or were injured while drinking. For this group, 77% had no problems, 9% reported one, 5% each two and three problems, with 4% reporting four or more such difficulties. The average number of problems per person in the prior 12 months (including zeros) was 0.5 (1.24). Finally regarding variables used in the model, the average number of drinks per drinking day across up to six peers (PEER) was 2.2 (1.78).

Measures

Level of Response to alcohol (LR)

Offspring were included in the current analyses if they had ever consumed a full drink (~ 12 gm of ethanol), in which case they were asked at the “clinic” to fill out a questionnaire regarding the number of drinks needed for effects from the first, up to the approximate first five times alcohol was consumed. The LR score was generated as a manifest variable through summing the number of standard (~12 gm of ethanol) drinks required across four potential effects, and dividing that figure by the number of effects endorsed. These included the number of drinks required early in the drinking career to produce: feelings of any effect, dizziness or slurred speech, a stumbling gait, and falling asleep unintentionally [6, 34, 35]. On the Self Report of the Effects of Ethanol (SRE) questionnaire, a higher number of drinks required across effects represents a lower response per drink; the equivalent of a low LR on alcohol challenges [8, 9, 34–36]. The SRE has a Cronbach alpha >.90; retest reliabilities >.80; SRE-based LR scores correlate well with alcohol challenges evaluating alcohol-related changes after consuming alcohol; relationships of the LR scores among first-degree relatives are higher than among unrelated individuals; and a low LR predicts heavier drinking and alcohol problems five years later [8, 9, 34, 35].

Alcohol Outcomes, Age and Sex

For these analyses, the alcohol outcome (ALCOUT) was determined as a latent variable from the age13/14 questions extracted from the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA) instrument developed by the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism investigation [37, 38]. The alcohol questions have both retest reliabilities and validities compared to another standardized instrument >.80 [38]. The three indicators used here included the maximum number of drinks consumed in the prior six months, the usual number of drinks per week over the prior six months, and the number of 12 possible alcohol problems in the last 12 months. The quantity-based outcomes were chosen as the most direct measure of the hypothesized higher levels of alcohol intake related to the low effect per drink [2, 6], while alcohol problems have been projected as an expected consequence of heavier drinking at even a young age. The problems queried here included the need for more and more alcohol to get effects (tolerance), exceeding set alcohol limits, feeling the need to stop or cut down on drinking, skipping school to drink, going to school drunk or hung over, drinking in hazardous situations (e.g., skateboarding), police problems, parents or friends complaining about drinking (two items), drinking-related injuries, drunken fights, and blackouts. The SSAGA was also the source for the manifest variable age and sex.

Peer Drinking

Drinking among peers (PEER) was incorporated as a manifest variable at age 13/14 using the subject’s estimation of the usual quantity of drinking among up to six important persons in their lives as generated from the Important People and Activities Scale (IPA) [39, 40]. This measure has retest reliabilities of 0.80 and higher, with comparable results to those obtained from other measures of drinking among peers [39, 41].

Data Analyses

Correlations used the Pearson Product Moment approach for continuous variables and Point-Biserial analyses for nominal data. SEM was selected as the major analysis because this approach evaluates values for the key outcomes through generating factor scores that reflect the characteristics of each population and minimizes error variance [42]. The SEM was carried out with the maximum likelihood estimation for analysis of the variance/covariance matrix of AMOS [43]. The final SEM was also run using Mplus as a cross-check and to use the attributes of both programs [44]. The stability of parameter estimation and of the structural equation model results were evaluated via AMOS bootstrapping procedures. This was repeated 1000 times. Goodness of fit for the measurement model and SEM included a determination of the chi square (Π2); the Π2 to degrees of freedom ratio (good fit = a 2-to-3 ratio) [45]; the CFI, or Comparative Fit Index (good fit is indicated by scores > .90) [46, 47]; the NNFI or Non-Normal Fit Index with good fit indicated by values approaching 1.0 [48]; RMSEA or the Root Mean Square Error Approximation (values < .05 indicate good fit) [47]; along with the SRMR or Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual where good fit is indicated by a score of < .08 [47]. Mediation was evaluated using the cross-product approach computed by the INDIRECT command in Mplus [49].

Results

Table 1 lists the correlations among domains used in the SEM. Here, a low LR to alcohol (i.e., a higher number of drinks required for effects on the SRE) was related to heavier drinking and more alcohol problems and to heavier-drinking peers (PEER), but not to age or sex. Higher PEER drinking also correlated with heavier drinking and alcohol problems (ALCOUT) in the person and with older age, but not with sex. In this sample, sex correlated with age because girls were older than boys.

Table 1.

Pearson Product Moment and Point-Biserial Correlations for Variables Used in the Figures for 688 13-Year Olds

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Here LR = the level of response to alcohol; ALCOUT is the latent variable used in the SEM as generated from maximum drinks/day and the usual number of drinks/week in the prior 6 months, and the number of alcohol problems in the prior 12 months; PEER was the number of drinks per drinking day reported for up to 6 peers; while AGE and SEX were as determined on the interview.

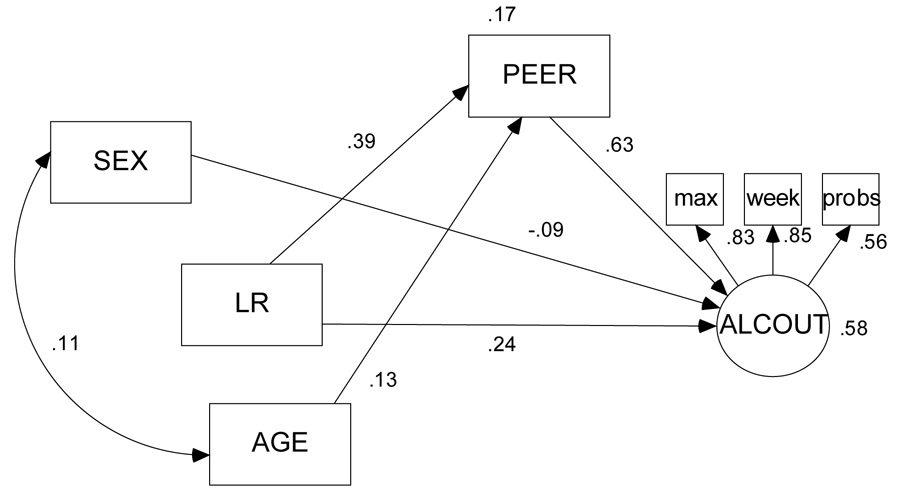

Figure 2 demonstrates the results of the SEM, only reporting significant relationships (p<.05). While not shown here, the Mplus analyses were similar to those from the AMOS approach shown in the figure. The fit indices for Figure 2 were good, including: Π2 (12) = 35.18, p< .001; Π2 /df = 2.93; CFI = .98; NNFI = .97; RMSEA = .053 (90% confidence interval = .033 – .074); and SRMR = .029. The key elements of the hypothesized model were supported in the SEM in which a higher number of drinks to get effects (a low LR per drink) related significantly and positively to heavier drinking in both peers (PEER) and for the subject herself or himself (ALCOUT). In the model, mediation occurred in the path from LR to PEER to ALCOUT (b = .46, se = 0.48, z = 9.54, p<.001), and the path for AGE to PEER to ALCOUT (b = .48, se = .132, z = 3.67, p<.001). SEX only related to AGE and ALCOUT, while an older AGE related to heavier drinking peers.

Figure 2.

SEM for the 688 drinking 13-year olds using the abbreviations presented in Table 1 and Figure 1. In addition, the indicators for the latent variable ALCOUT were maximum drinks/day (max) and the usual number of drinks/week in the prior 6 months (week), and the number of alcohol problems in the prior 12 months (probs). Here, only the significant paths (p < .05) are presented, path values are beta weights, and the final R2 is listed next to ALCOUT.

Two additional analyses were carried out to further evaluate the SEM results. First, reflecting a concern that the dependence items of tolerance and setting limits on drinking might affect the outcomes and relationships with SRE scores reported here, the model in Figure 2 was repeated after excluding these two items. The problem score based on 10 items correlated with the original 12-item-based score at .96 (p<.0001), and the subsequent model was virtually identical to Figure 2 regarding significant paths, specific path coefficients, and the proportion of the variance explained.

The second modification of Figure 2 was a consequence of the fact that the distributions of alcohol-related variables are often skewed, which could affect the SEM results. Therefore, the analysis was repeated after using transformations selected based on the topography of the specific item. Thus, inverse transformations were used for the SRE score, weekly drinking quantity and alcohol problems; log transformations were applied for maximum drinks; and square root transformations for the PEER variable. Once again, all significant paths in Figure 2 remained, no new paths were added, and only minor changes in path coefficients were obtained.

The potential effects of SEX in the model in Figure 2 were further evaluated through a visual comparison of model structures for boys and girls and via invariance procedures. The non-constrained modeling of boys and girls yielded good fit characteristics with CFI = .97, NNFI = .95, RMSEA = .057 (90% confidence interval .40 = .074), and SRMR = .033. For both sexes the paths in Figure 2 for LR to PEER, AGE to PEER, and PEER to ALCOUT were essentially the same, and the path from LR to ALCOUT was similar but ranged from .19 in boys to .29 in girls. As a part of the testing of invariance, constraining relationships as equal for boys and girls revealed that the models for boys and girls were quite similar for path estimates (Π2 (4) = 2.28, p = .69) and variance of the exogenous variable (Π2 (1) = 4.69, p = .10). However, regarding formal invariance testing across sex, there were significant differences for factor loadings on the latent variable (Π2 (2) = 11.71, p<.01). The model fit indices were good, varying only slightly across levels of invariance testing [CFI = .97 for all, NNFI from .94 to .96, RMSEA from .054 (.040 = .069) to .061 (.046 – .077), SRMR from .033 to .041].

Finally, to further evaluate the stability of model parameters, bootstrapping procedures were employed within AMOS. The procedure generated no unused samples and 1000 useable samples. The results strongly supported the original parameter values generated via maximum likelihood, and reflected robust SE estimates. Bias, the differences between bootstrap generated means and the original estimates, ranged from .000 to .004 for standardized parameters, from .000 to .065 for variances, and from .000 to .006 for squared multiple correlations. The bias was .000 for the relationship between SEX and AGE.

Discussion

These analyses represent the first evaluation of an LR-based model in a large number of 13-year-old drinkers studied outside the United States. The results from the ALSPAC protocol regarding the key domains of LR, ALCOUT, AGE, and SEX are similar to those generated from the adult and adolescent samples to date [10, 12, 14]. Thus, while data were generated in only one large sample from a limited geographic area and limited demography, the results support potential generalizability of elements of the model developed and tested in the U.S. regarding how a low LR to alcohol relates to drinking practices in additional samples studied very early in the drinking career. The average age of 13 years, along with the low frequency of drinking (two days a month) and low intake (an average of two drinks per occasion) support the contention that the low LR as measured here was not likely to be a consequence of tolerance acquired in the context of regular heavy drinking, but may reflect innate sensitivity to alcohol.

An important new finding reported here relates to the performance of the domain of peer drinking. The perceived quantity of alcohol intake among significant individuals in the 13-year-old’s life mediated the relationship between a low LR and ALCOUT, in a manner not found in evaluations of young adults or older teenagers or in older adults [10, 12, 14]. The PEER variable functioned as predicted within the present young population, even after considering the impact of age and sex. The performance of PEER in mediating the relationship between LR and ALCOUT in the ALSPAC sample may reflect the young age of this group, with the possibility that the PEER domain becomes less central to the way that LR relates to ALCOUT as subjects reach their mid-to-late teens or adulthood [6, 10, 14].

The performance of SEX in the model is worth noting. Boys demonstrated higher scores for ALCOUT, and girls were a bit older, but the model performed similarly in the two sexes. It is also of interest to note that the impact of older age on heavier drinking and alcohol problems was mediated in the model by heavier peer drinking.

While the ALSPAC dataset included several variables important to the evaluation of an LR-based model of drinking behaviors, some key influences were not measured. The first involves the expectations of the effects of alcohol (EXPECT), a domain shown in prior studies to be an additional mediator of the relationship of LR to ALCOUT in older teens [10]. Unfortunately, most standardized measures of the EXPECT are more time consuming than could be accommodated during the ALSPAC evaluations. The second absent domain of potential interest is the family history of AUDs. While these data are available for the biological mothers of the ALSPAC offspring, family history had not been systematically evaluated in the fathers, making it difficult to establish a reliable family domain to incorporate into the model. Finally, the ALSPAC protocol did not include a measure of using alcohol to cope with stress (COPE), a domain that performed well in the model in older populations [12].

The ALSPAC dataset offers many important attributes, and this is a valuable population in which to measure aspects of the hypothesized LR-based model. However, as is true of all studies, it is important to recognize potential caveats in interpreting the results. First, the population, while large, was selected from only one section in the UK, and was mostly Anglo-European in background. As a non-clinical sample it is likely that the impact of extreme psychopathology or extensive substance use in the offspring and their parents could not be adequately evaluated, and these factors were not considered in the analyses. Second, the questionnaires used to measure the domains were relatively limited in scope, and it is possible that different findings might have resulted if alternative measures had been used. For example, the score for drinking in peers represents the offsprings’ perceptions of what they believed their peers drank and did not include a potentially more accurate assessment of the peers themselves. In addition, the SRE only broadly defines the time period of interest up to the First 5 times of drinking, with subsequent variance in the number of times considered. Third, all the information recorded here came from self-reports by the adolescents themselves, without corroborating information.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses. The UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. This publication is the work of the authors who also serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper.

This work was supported by the Veterans Affairs Research Service; by funds provided by the State of California for medical research on alcohol and substance abuse through the University of California, San Francisco; and by NIAAA Grant 2R01 AA05526.

References

- 1.Prescott CA, Aggen SH, Kendler KS. Sex differences in the sources of genetic liability to alcohol abuse and dependence in a population-based sample of U.S. twins. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1136–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuckit MA. Vulnerability Factors for Alcoholism. In: Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff CB, editors. Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. pp. 1399–1341. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuckit MA, Smith TL. The relationships of a family history of alcohol dependence, a low level of response to alcohol and six domains of life functioning to the development of alcohol use disorders. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:827–835. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin HA, Wall TL, Schuckit MA, Koob GF. Differential effects of ethanol on punished responding in the P and NP rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:700–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barr CS, Newman TK, Lindell S, Shannon C, Champoux M, Lesch KP, et al. Interaction between serotonin transporter gene variation and rearing condition in alcohol preference and consumption in female primates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1146–1152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Waylen A, Horwood J, Danko GP, Hibbeln JP, et al. An evaluation of the performance of the Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol Questionnaire in 12- and 35-year-old subjects. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2006;67:841–850. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heath AC, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Dinwiddie SH, Slutske WS, Bierut LJ, et al. Genetic differences in alcohol sensitivity and the inheritance of alcoholism risk. Psychol Med. 1999;29:1069–1081. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuckit MA, Edenberg HJ, Kalmijn J, Flury L, Smith TL, Reich T, et al. A genome-wide search for genes that relate to a low level of response to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Pierson J, Hesselbrock V, Bucholz KK, et al. The ability of the Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) Scale to predict alcohol-related outcomes five years later. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:371–378. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Trim R, Kreikebaum S, Hinga B, Allen R. Testing the level of response to alcohol-based model of heavy drinking and alcohol problems in the offspring from the San Diego Prospective Study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.571. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volavka J, Czobor P, Goodwin DW, Gabrieli WF, Jr, Penick EC, Mednick SA, et al. The electroencephalogram after alcohol administration in high-risk men and the development of alcohol use disorders 10 years later: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:258–263. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Anderson KG, Brown SA. Testing the level of response to alcohol: Social Information Processing Model of Alcoholism Risk-a 20-year prospective study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1881–1889. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000148111.43332.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Anderson KG, Brown SA, Kuperman S, et al. Evaluation of a level of response to alcohol-based structural equation model in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:174–184. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trim R, Schuckit MA, Smith TL. Level of response to alcohol within the context of alcohol-related domains: An examination of longitudinal approaches assessing changes over time. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00645.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armeli S, Carney MA, Tennen H, Affleck G, O’Neil TP. Stress and alcohol use: A daily process examination of the stressor-vulnerability model. J Pers Social Psychol. 2000;78:979–994. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.5.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neighbors C, Walker DD, Larimer ME. Expectancies and evaluations of alcohol effects among college students: Self-determination as a moderator. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:292–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wild TC. Personal drinking and sociocultural drinking norms: A representative population study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:469–475. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carpenter KM, Hasin DS. Reasons for drinking alcohol: Relationships with DSM-IV alcohol diagnoses and alcohol consumption in a community sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 1998;12:168–184. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simons J, Correia CJ, Carey KB. A comparison of motives for marijuana and alcohol use among experienced users. Addict Behav. 2000;25:153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Todd M, Armeli S, Tennen H, Carney MA, Ball SA, Kranzler HR, et al. Drinking to cope: A comparison of questionnaire and electronic diary reports. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:121–129. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussong AM, Galloway CA, Feagans LA. Coping motives as a moderator of daily mood-drinking covariation. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:344–353. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dodge KA, Laird R, Lochman JE, Zellli A. A multidimensional latent-construct analysis of children’s social information processing patterns: Correlations with aggressive behavior problems. Psychol Assess. 2002;14:60–73. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Burks VS, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Fontaine R, et al. Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Dev. 2003;74:374–393. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry KL, Slater MD, Oetting ER. Alcohol use in early adolescence: the effect of changes in risk taking, perceived harm and friends’ alcohol use. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:275–283. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baer JS. Student factors: Understanding individual variation in college drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2002 Suppl No. 14:40–53. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poelen EA, Scholte RHJ, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI, Engels RCME. Drinking by parents, siblings, and friends as predictors of regular alcohol use in adolescents and young adults: A longitudinal twin-family study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:362–369. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lonczak HS, Huang B, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Hill KG, Abbott RD, et al. The social predictors of adolescent alcohol misuse: A test of the social development model. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:179–189. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiesbeck G. Gender-specific issues in alcoholism, Introduction. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2003;6:223–224. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faden V, Fay M. Trends in drinking among Americans age 18 and younger: 1975–2002. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1388–1395. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000139820.04539.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGue M, Sharma A, Benson P. Parent and sibling influences on adolescent alcohol use and misuse: evidence from a U.S. adoption cohort. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:8–18. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newcomb MD. Psychosocial predictors and consequences of drug use: a developmental perspective within a prospective study. J Addict Dis. 1997;16:52–89. doi: 10.1300/J069v16n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golding J, Pembrey M, Jones R ALSPAC Study Team. ALSPAC-the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children: I. Study methodology. Paed Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:74–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Tipp JE. The Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) form as a retrospective measure of the risk for alcoholism. Addiction. 1997;92:979–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Smith TL, Wiesbeck GA, Kalmijn J. The relationship between self-rating of the effects of alcohol and alcohol challenge results in ninety-eight young men. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:397–404. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daeppen J-B, Landry U, Pêcoud A, Decrey H, Yersin B. A measure of the intensity of response to alcohol to screen for alcohol use disorders in primary care. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35:625–627. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.6.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Jr, et al. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: A report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hesselbrock M, Easton C, Bucholz KK, Schuckit M, Hesselbrock V. A validity study of the SSAGA: A comparison with the SCAN. Addiction. 1999;94:1361–1370. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groh DR, Olson BD, Jason LA, Davis MI, Ferrari JR. A factor analysis of the Important People Inventory. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:347–353. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Rice C. In: Social Functioning in Project MATCH Hypotheses: Results and Causal Chain Analyses (NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series, NIH Publication No. 01-4238) Longabaught R, Wirtz PW, editors. Vol. 8. Rockville, MD: NIAAA; 2001. p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longabaugh R, Beattie M, Noel N, Stout R, Malloy P. The effect of social investment on treatment outcome. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54:465–478. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuckit MA, Windle M, Smith TL, Hesselbrock V, Ohannessian C, Averna S, et al. Searching for the full picture: structural equation modeling in alcohol research. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:194–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 User’s Guide. Chicago, Il: Small Waters Corp; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Fourth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wheaton B, Muthen B, Allwin DF, Summers GF. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. In: Heise DR, editor. Sociology Methodology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 84–136. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structural analysis: sensitivity to underparametersized model misspecification. Psychol Methods. 1998;4:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bentler PM, Chou C. Estimates and tests in structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995. pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]