Abstract

Background

Binge drinking is associated with risky sexual behaviors and STDs. Few studies have investigated this by gender or in an STD clinic. This cross-sectional study examined the association between binge drinking and risky sexual behaviors/STDs among patients attending an urban STD clinic.

Method

671 STD clinic patients were tested for STDs, and queried about recent alcohol/drug use and risky sexual behaviors using audio computer-assisted-self-interview. The association between binge drinking and sexual behaviors/STDs was analyzed using logistic regression adjusting for age, employment, and drug use.

Results

Binge drinking was reported by 30% of women and 42% of men. Gender differences were found in rates of receptive anal sex which increased linearly with increased alcohol use among women but did not differ among men. Within gender analyses showed that women binge drinkers engaged in anal sex at more than twice the rate of women who drank alcohol without binges(33.3% vs. 15.9%;p<.05) and three times the rate of women who abstained from alcohol(11.1%;p<.05). Having multiple sex partners was more than twice as common among women binge drinkers than women abstainers(40.5% vs. 16.8%;p<.05). Gonorrhea was nearly 5 times higher among women binge drinkers compared to women abstainers(10.6% vs.2.2%;p<.05). The association between binge drinking and sexual behaviors/gonorrhea remained after controlling for drug use. Among men, rates of risky sexual behaviors/STDs were high, but did not differ by alcohol use.

Conclusion

Rates of binge drinking among STD clinic patients were high. Among women, binge drinking was uniquely associated with risky sexual behaviors and an STD diagnosis. Our findings support the need to routinely screen for binge drinking as part of clinical care in STD clinics. Women binge drinkers, in particular, may benefit from interventions that jointly address binge drinking and risky sexual behaviors. Developing gender-specific interventions could improve overall health outcomes in this population.

Keywords: hazardous alcohol use, binge drinking, risky sexual behavior, STDs, gender differences

Introduction

Alcohol consumption is associated with risky sexual behaviors, including unprotected sexual intercourse and multiple sex partners (Cooper, 2002; Graves and Leigh, 1995; Santelli et al., 1998). Alcohol consumption is also related to an increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), although few studies have utilized standardized indicators of alcohol abuse, performed laboratory assays for STDs, or had adequate sample sizes (Cook and Clark, 2005; Cook et al, 2006). One recognized measure of hazardous alcohol use is binge drinking (5 or more alcoholic beverages on one occasion; Naimi et al., 2003) which is more prevalent than alcohol abuse/dependence and is associated with adverse health outcomes, including risky sexual behaviors (Bouhnik et al., 2007; Ogletree et al., 2001; Semaan et al., 2003).

STD clinics are one of the primary sites for diagnosing and treating STDs and HIV in persons engaging in risky sexual behaviors. Until recently, however, alcohol use and its association with risky sexual behaviors and STDs among STD clinic patients have received little investigation (Cook and Clark, 2005). This is surprising given the intersection of these two significant health problems as well as the success of some initial efforts to combine risk reduction strategies (Avins et al., 1997; Kalichman et al., 2007). A recent study of adolescents and young adults (aged 15-24) attending an STD clinic underscores the high rates of alcohol consumption in this setting (Cook et al 2006). Rates of binge drinking were 39.6% among women and 48.0% among men; rates of alcohol abuse/dependence were 23.6% among women and 33.2% among men. Women and men who were abusing or dependent upon alcohol engaged in more risky sexual behaviors, and men who were abusing or dependent upon alcohol were more likely to have a diagnosed STD. Other studies of adult STD clinic patients report rates of up to 21% of alcohol misuse as well as the association between alcohol use and having multiple sex partners, unprotected sex, and STDs (Cook and Clark, 2005; Kalichman et al., 2003; Zenilman et al., 1994). STD clinics offer a unique opportunity to provide needed intervention to reduce both hazardous drinking and risky sexual behaviors.

The role of gender in the association between hazardous alcohol use and risky sexual behaviors has not been adequately studied in either STD clinics or the general population (Amaro, 1995; Bryant, 2006; Exner et al., 2003). Compared to men, women are at greater risk for adverse health outcomes (e.g., alcohol-related physical illnesses, cognitive motor impairment, and breast cancer) caused by hazardous alcohol abuse (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). Women also suffer severe health consequences from engaging in risky sexual behaviors (e.g., complications from untreated STDs, such as infertility or chronic pelvic pain). Furthermore, rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia are higher in women and are increasing (CDC, 2007). Thus, studying gender differences in hazardous drinking and risky sexual behaviors can aid development of targeted prevention strategies to reduce adverse health outcomes in this high-risk population.

The objective of this cross-sectional study was to examine the relationship between alcohol consumption, risky sexual behaviors and STDs among women and men attending an urban STD clinic. Specifically, we hypothesized that women and men who engaged in binge drinking would have higher rates of risky sexual behaviors, and higher rates of STDs compared to women and men who drank but did not binge, or who abstained from alcohol.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Between July 2000 and August 2001, a clinic research assistant approached 795 men and women aged > 18 years who presented consecutively for evaluation and/or treatment to an urban STD clinic. After describing the study, 671 (84%) agreed to participate and written informed consent was obtained. The institutional review boards of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Baltimore City Health Department approved the study.

Procedures

Study participants were interviewed using the Risk Behavior Assessment (RBA), a structured interview developed by the Community Research Branch of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, 1991), that obtains information on demographics, alcohol/drug-risk behaviors (type of drug used, route of administration), hetero- and homosexual sexual behaviors (oral/vaginal/anal sex, number of sex partners, condom use, trading sex for drugs or money, being “high” on alcohol/drugs during sex) as well as drug/psychiatric treatment and arrest history. Most RBA questions used either a 30 day or ever/never lifetime recall period. The interview was administered using audio computer-assisted self interview (ACASI) which allows the participant to simultaneously read on a computer monitor and hear through headphones the study questions that had been previously recorded by the research assistant. The Questionnaire Development System software for this program was created by Nova Research Company (1999). The ACASI was administered in a private room with the research assistant seated nearby to provide assistance but not in sight of the study participants’ keyboard/monitor.

Participants were administered a pre-test to ensure they understood how to answer RBA questions, which takes approximately 30-45 minutes to complete. Reliability checks were programmed into the ACASI software to detect discrepant entries, allowing the participants to make corrections as needed.

Following completion of the RBA, all study participants received a routine STD clinical evaluation, which included a physical examination by a nurse practitioner as well as laboratory analyses (gonorrhea culture, chlamydia testing by polymerase chain reaction on urine (male) or endocervical secretions (female), and syphilis serologic testing).

Data analysis

Participants were classified into one of three mutually exclusive Alcohol Use Groups based on their response to the two alcohol questions on the RBA: “In the past 30 days, on how many days have you had one or more drinks of alcohol?” and “In the past 30 days, on how many days have you had 5 or more drinks of alcohol?” If study participants reported any day in which 5 or more drinks were consumed, they were classified in the “binge drinking” group. If there were no reported episodes of binge drinking, but alcohol was consumed in the past 30 days, participants were classified in the “alcohol use without binges” group. If alcohol was not consumed in the past 30 days, participants were classified in the “no alcohol use” group.

Demographic and substance use variables were compared by gender. Categorical variables were examined using chi square tests and continuous variables were examined using t-tests for independent samples.

Eight dichotomous sexual behaviors/STDs status variables occurring in the preceding 30 days were derived from the RBA: 1) engaged /did not engage in vaginal sex; 2) engaged/did not engage in anal sex; 3) had 2 or more sex partners/had one sex partner; 4) had unprotected sex/had protected sex (i.e. condom use); and 5) traded sex for money or drugs/did not trade sex for money or drugs; 6) tested positive or negative for chlamydia; 7) tested positive or negative for gonorrhea; and 8) tested positive or negative for syphilis. Multivariate logistic regression modeling was used to examine the main effects of Alcohol Use Group and gender on the outcome measures of sexual behaviors/STDs status, separately, in the last 30 days. Covariates entered into all models were: subjects’ age, employment status, marijuana use, and heroin/cocaine use.

Women and men study participants were combined in a multivariate logistic regression to evaluate the interaction of the alcohol use group with gender. Interaction effects were considered significant at the alpha 0.10 level and effects that were not considered significant were removed from the modeling to produce a reduced main effects only model. Multivariate logistic regression also tested the significant main effects of alcohol use group, adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were produced controlling for all other covariates simultaneously entered into the models. Next, similar modeling was used to examine the main effects of Alcohol Use Group for the subgroups of women and men. In the case of small cell sizes, exact logistical regression was used.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (2006).

Results

Subject characteristics

Men STD clinic patients (81/401) were more likely to refuse study participation than women (43/394; p<.01). Women and men patients who declined participation did not differ in age or race from those men and women who consented (all p’s>.10). Study participants were women (52%), and across gender were 95% African American, 73% never married, 83% heterosexual, and 77% had a partial/high school education/GED. Sixty-four percent of men and 32% of women reported having been arrested.

Women who drank alcohol without binges were younger than women who either binged or abstained from alcohol (F=3.4, df=2; p<.05; Table 1). Women binge drinkers were less likely to be employed than women who drank alcohol without binges or abstained from alcohol (ϰ2=6.4; p<.05)). Men who binged or drank alcohol without binges were younger than men who abstained (F=6.3, df=2; p<.01) and men binge drinkers tended to be unemployed (ϰ2= 5.4; p<.07).

Table 1.

Demographic and substance use characteristics of women and men STD clinic patients as a function of recent alcohol use

| No Alcohol Use | Alcohol Use without Binges |

Binge Drinking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| N=134 | N=109 | N=113 | N=78 | N=104 | N=133 | |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Characteristic: | ||||||

| Age X (SD) | 29.6 (9.1) | 33.2(7.1) | 27.1(7.1)* | 30.6(7.1) | 29.6(8.6) | 29.2(8.7)* |

| African- American |

95.5 | 95.4 | 89.4 | 97.4 | 95.2 | 97.7 |

| Never married | 73.1 | 71.6 | 76.1 | 71.8 | 72.1 | 73.7 |

| High School/GED |

76.9 | 78.9 | 68.1 | 70.5 | 80.8 | 82.6 |

| Employed | 60.4 | 68.8 | 55.8 | 64.1 | 44.2* | 54.5 |

| Heterosexual | 78.4 | 86.2 | 83.0 | 89.7 | 77.9 | 85.0 |

| Ever arrested | 32.1 | 63.2 | 31.0 | 53.8 | 34.0 | 70.5 |

| In last 30 days: | ||||||

| Income < $500 | 66.9 | 48.6 | 55.8 | 50.6 | 72.1 | 56.4 |

| Days Drank Alcohol X (SD) |

N/A | N/A | 3.3(4.0) | 4.7(5.7) | 7.5(8.3) | 10.2 (8.5) |

| Days Binged X (SD) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.7(4.1) | 5.5 (6.3) |

| Smoked marijuana |

11.2 | 11.0 | 29.2 | 39.7 | 49.0 | 53.4 |

| Used heroin/cocaine |

3.7 | 6.4 | 9.7 | 15.4 | 22.1 | 13.5 |

p <.05

Substance use in the last 30 days

Alcohol Use Group

Overall, 35.3% (N=237) of participants reported at least one episode of binge drinking in the last 30 days. Among women, 30% (N=104) reported at least one episode of binge drinking and they consumed alcohol on more than twice the number of days as women who drank alcohol without binges (F= 23.1, df=2; p<.01; Table 1). Alcohol Use Group was associated with marijuana use (AOR=2.7; 95%CI, 2.0-3.8, p<.01) and heroin/cocaine use in the last 30 days (AOR=2.6; 95%CI, 1.6-4.2, p<.01).

Among men, 42% reported at least one episode of binge drinking and they consumed alcohol on more than twice the number of days compared to men who drank alcohol without binges (F=26.1; df=2, p<.01; table 2). Overall, Alcohol Use Group was associated with marijuana use (AOR =2.8; 95%CI, 2.0-4.0, p<.01) and heroin/cocaine use in the last 30 days (AOR=1.9; 95%CI, 1.2-3.3, p<.01). .

Table 2.

Sexual behaviors in the preceding 30 days associated with Alcohol Use in the Past 30 Days

| Sexual behaviors in the preceding 30 days | All Participants - N=523 | Men - N=259 | Women - N=264 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | AOR | 95% CIs | p-value | n (%) | AOR | 95% CIs | p-value | n (%) | AOR | 95% CIs | p-value | ||

| Unprotected Sex | |||||||||||||

| Alcohol Use | No alcohol use | 173 (90.1) | - | - | 0.317 | 78 (89.5) | - | - | 0.317 | 95 (90.5) | - | - | 0.496 |

| Alcohol use without binges | 157 (88.5) | 0.92 | 0.44,1.9 | 67 (80.6) | 0.59 | 0.21, 1.6 | 90 (94.4) | 1.8 | 0.56, 5.89 | ||||

| Binge drinking | 193 (87.6) | 0.82 | 0.92, 1.8 | 114 (86.0) | 1.5 | 0.65, 3.4 | 79 (89.9) | 0.43 | 0.43, 1.45 | ||||

| Gender | Males | 259 (85.6) | - | - | 0.044 | ||||||||

| Females | 264 (91.7) | 1.8 | 1.0, 3.2 | ||||||||||

| Vaginal Sex | |||||||||||||

| Alcohol Use | No alcohol use | 173 (91.9) | - | - | 0.3518 | 78 (91.0) | - | - | 0.9284 | 95 (92.6) | - | - | 0.0918 |

| Alcohol use without binges | 157 (93.0) | 1.35 | 0.57, 3.23 | 67 (89.6) | 0.86 | 0.28, 2.72 | 90 (95.6) | 2.85 | 0.70, 11.53 | ||||

| Binge drinking | 193 (93.3) | 1.94 | 0.79, 4.74 | 114 (90.4) | 1.06 | 0.35, 3.20 | 79 (97.5) | 6.46 | 1.09, 38.28 | ||||

| Gender | Males | 259 (90.3) | - | - | 0.0563 | ||||||||

| Females | 264 (95.1) | 2.01 | 0.98, 4.13 | ||||||||||

| Anal Sex | |||||||||||||

| Alcohol Use | No alcohol use | 164 (15.2) | - | - | 0.0131 | 74 (20.3) | - | - | 0.3561 | 90 (11.1) | - | - | 0.0053 |

| Alcohol use without binges | 153 (14.4) | 0.94 | 0.49, 1.79 | 65 (12.3) | 0.57 | 0.22, 1.49 | 88 (15.9) | 1.48 | 0.60, 3.68 | ||||

| Binge drinking | 186 (25.8) | 2.02 | 1.12, 3.64 | 108 (20.4) | 1.08 | 0.48, 2.42 | 78 (33.3) | 3.8 | 1.58, 9.10 | ||||

| Gender | Males | 247 (18.2) | - | - | 0.5223 | ||||||||

| Females | 256 (19.5) | 1.16 | 0.73, 1.86 | ||||||||||

| Multiple Sex Partners | |||||||||||||

| Alcohol Use | No alcohol use | 173 (33.5) | - | - | 0.1038 | 78 (53.8) | - | - | 0.8399 | 95 (16.8) | - | - | 0.0233 |

| Alcohol use without binges | 157 (42.7) | 1.38 | 0.85, 2.24 | 67 (56.7) | 0.99 | 0.50, 1.95 | 90 (32.2) | 2.00 | 0.97, 4.15 | ||||

| Binge drinking | 193 (53.4) | 1.68 | 1.04, 2.71 | 114 (62.3) | 1.17 | 0.62, 2.21 | 79 (40.5) | 2.84 | 1.34, 6.04 | ||||

| Gender | Males | 259 (58.3) | - | - | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Females | 264 (29.2) | 0.3 | 0.21, 0.44 | ||||||||||

| Sex for money or drugs | |||||||||||||

| Alcohol Use | No alcohol use | 173 (2.3) | - | - | 0.8253 | 78 (1.3) | - | - | N/A | 95 (3.2) | - | - | 0.9185* |

| Alcohol use without binges | 157 (3.2) | 0.92 | 0.20, 4.13 | 67 (1.5) | 90 (4.4) | 0.86 | 0.14, 5.25 | ||||||

| Binge drinking | 193 (5.7) | 1.32 | 0.34, 5.19 | 114 (1.8) | 79 (11.4) | 1.28 | 0.25, 6.59 | ||||||

| Gender | Males | 259 (1.5) | - | - | 0.0186 | ||||||||

| Females | 264 (6.1) | 4.24 | 1.27, 14.09 | ||||||||||

Logistic regression analyses adjusted for covariates of participant’s age, employment status, marijuana use, and heroin/cocaine use. Shown are adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Due to small cell sizes main effects (p-values) were tested using exact logistic regression analyses.

Sexual behaviors as a function of Alcohol Use Group in the last 30 days

Seventy-five percent of women (N=264/351) and 81% of men (N=259/320) reported being sexually active with a partner in the last 30 days. There were no differences in demographic or substance use variables between women who reported or did not report recent sexual activity. On average, sexually active men consumed alcohol on more days (6.4; SD=8.0) and smoked marijuana on more days (6.1; CD=10.5) than men who were not sexually active in the last 30 days (alcohol: 2.6; SD=5.2) (F=10.7; p<.01) (marijuana: 2.9; SD=3.57.6; F=5.2, p<.05).

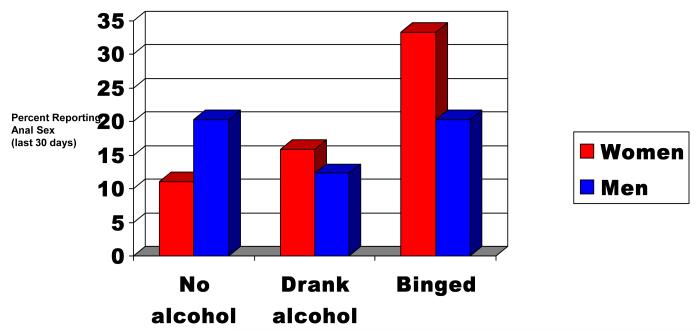

Among participants who were sexually active, receptive anal sex showed a significant interaction between Alcohol Use Group and gender (ϰ2 (2) = 5.44; p=0.0658; Table 2). Evaluation of this effect showed that anal sex among women increased linearly with increased alcohol usage (No alcohol use: 11.1%, Alcohol use without binges: 15.6%, and Binge drinking: 33.3) whereas men reported similar rates of receptive anal sex across all three drinking groups (No alcohol use: 20.3%, Alcohol use without binges: 12.3%, and Binge drinking: 20.4); Figure 1). No other Alcohol Use Group by gender interactions were shown to be statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Gender differences in receptive anal sex as a function of recent alcohol use

Gender was associated with having unprotected sex, multiple sex partners, trading sex for money or drugs (Table 2) and gonorrhea (Table 3). Compared to men, women were more likely to have unprotected sex (91.7% vs. 85.7%) and had four times the rate of trading sex for money/drugs (6.1% vs. 1.5%). Men had twice the rate of multiple sex partners (58.3% vs. 29.2%) and nearly three times the rate of gonorrhea (17% vs. 6%; Table 3).

Table 3.

STDs status in the preceding 30 days associated with Alcohol Use in the Past 30 Days (Full Sample)

| STDs diagnosis | All Participants - N=671 | Men - N=320 | Women - N-351 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | AOR | 95% CIs | p-value | n (%) | AOR | 95% CIs | p-value | n (%) | AOR | 95% CIs | p-value | ||

| Gonorrhea | |||||||||||||

| Alcohol Use | No alcohol use | 243 (5.3) | - | - | 0.0228 | 109 (9.2) | - | - | 0.1199 | 134 (2.2) | - | - | 0.0262* |

| Alcohol use without binges | 191 (12.0) | 2.31 | 1.10, 4.84 | 78 (21.8) | 2.44 | 1.01, 5.86 | 113 (5.3) | 2.23 | 0.53, 9.38 | ||||

| Binge drinking | 237 (16.0) | 2.67 | 1.31, 5.45 | 133 (20.3) | 2.10 | 0.91, 4.88 | 104 (10.6) | 5.33 | 1.35, 21.01 | ||||

| Gender | Males | 320 (16.9) | - | - | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Females | 351 (5.7) | 0.29 | 0.17, 0.51 | ||||||||||

| Chlamydia | |||||||||||||

| Alcohol Use | No alcohol use | 238 (5.9) | - | - | 0.7149 | 105 (6.7) | - | - | 0.9894 | 133 (5.3) | - | - | 0.4211* |

| Alcohol use without binges | 182 (5.5) | 0.7 | 0.29, 1.70 | 73 (8.2) | 1.07 | 0.32, 3.55 | 109 (3.7) | 0.47 | 0.12, 1.79 | ||||

| Binge drinking | 229(8.3) | 0.92 | 0.41, 2.07 | 128 (8.6) | 0.99 | 0.33, 3.01 | 101 (7.9) | 1.06 | 0.32, 3.48 | ||||

| Gender | Males | 306 (7.8) | - | - | 0.2369 | ||||||||

| Females | 343 (5.5) | 0.68 | 0.35, 1.29 | ||||||||||

| Syphilis | |||||||||||||

| Alcohol Use | No alcohol use | 243 (3.1) | - | - | 0.7167 | 103 (1.9) | - | - | 0.6011* | 126 (4.0) | - | - | 0.3040* |

| Alcohol use without binges | 184 (2.7) | 0.94 | 0.28, 3.14 | 74 (5.4) | 2.75 | 0.45, 16.77 | 110 (0.9) | 0.24 | 0.03, 2.19 | ||||

| Binge drinking | 231 (4.8) | 1.41 | 0.48, 4.17 | 130 (4.6) | 2.27 | 0.38, 13.60 | 101 (5.0) | 1.21 | 0.29, 5.06 | ||||

| Gender | Males | 307 (3.9) | - | - | 0.9058 | ||||||||

| Females | 337 (3.3) | 0.95 | 0.40, 2.23 | ||||||||||

Logistic regression analyses adjusted for covariates of participant’s age, employment status, marijuana use, and heroin/cocaine use. Shown are adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Due to small cell sizes main effects (p-values) were tested using exact logistic regression analyses.

In gender subgroup analyses, women’s sexual behaviors in the last 30 days as a function of Alcohol Use Group are shown in Table 2. Significant differences were found in likelihood of having anal sex and multiple sex partners. Women binge drinkers (33.3%) were more than twice as likely to have receptive anal sex compared to women who drank alcohol without binges (15.9%; AOR=2.6; 95%CI, 1.2.-5.6) and nearly four times more likely to have anal sex compared to women who abstained from alcohol (11.1%; AOR=3.8; 95%CI, 1.6-9.1; Figure 1). Having had multiple sex partners was more than twice as common among women who binged (40.5%) compared to women who abstained from alcohol (16.8%; AOR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.3-6.0). Rates of vaginal sex were high for all women but this behavior did not differ as a function of alcohol use. Trading sex for money or drugs was more prevalent among women who binged on alcohol (11.4%) compared to women who drank (4.4%) or abstained (3.2%) but was not significant.

Men’s rates of most sexual behaviors in the last 30 days were high and did not differ as a function of alcohol use (See Table 2). Seventy-eight percent (78.4%) of men had vaginal sex (78.4%), 15.7% had receptive anal sex, 58.3% had multiple sex partners, 85.6% had unprotected sex, and 1.6% traded sex for money or drugs.

STD diagnosis as a function of Alcohol Use Group

Among all participants no statistically significant interactions were observed for Alcohol Use Group and gender for STDs status. Alcohol Use Group was associated with a diagnosis of gonorrhea (Table 3). Binge drinkers (16.0%) were more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with gonorrhea compared to participants who abstained from alcohol (5.3%; AOR=2.7; 95%CI, 1.3-5.4). Gender was associated with having a diagnosis of gonorrhea. In gender subgroup analyses, a significant difference was found in likelihood of a diagnosis of gonorrhea among women as a function of Alcohol Use Group. Women binge drinkers (10.6%) had more than five times the rate of gonorrhea compared to women who abstained from alcohol (2.2%; AOR= 5.3; 95% CI, 1.4-21.0). Men’s rates of diagnosed STDs did not differ as a function of alcohol use (See Table 3).

Discussion

Gender differences in alcohol use, risky sexual behaviors and STDs were examined among women and men attending an urban STD clinic. Rates of binge drinking were high among women and men. Receptive anal sex showed a significant interaction with alcohol use and gender. Among women, anal sex increased linearly with increased alcohol usage; whereas among men rates of receptive anal sex were similar regardless of alcohol usage. Within gender, women binge drinkers were significantly more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors and had nearly 5 times the rate of gonorrhea compared to women who abstained from alcohol. By contrast, no association was found between alcohol use and sexual behaviors or STDs in men. Men’s high base rates of sexual behaviors and STDs may have attenuated the ability to detect an association with alcohol use.

Rates of binge drinking in the study sample were high with 30% of women and 42% of men reporting at least one episode of binge drinking during the previous 30 days. Our findings are consistent with high rates of binge drinking found among adolescent and young adult STD clinic patients (Cook et al, 2006). Together, these studies show that binge drinking is prevalent among STD clinics patients. Binge drinking constitutes a serious health risk, especially for women whose metabolism of alcohol and body composition place them at higher risk than men for adverse physical, medical, social, and psychological consequences (NIAAA, 1999). Such adverse effects of alcohol for women emphasize the need for alcohol screening and referral/intervention in STD clinics.

Binge drinking in women was associated with engaging in risky sexual behaviors in the last 30 days. Importantly, the association between binge drinking and risky sexual behaviors and gonorrhea remained after controlling for marijuana, cocaine, and heroin use. Women binge drinkers (33.3%) had anal sex at more than twice the rate of women who drank alcohol but did not binge (15.9%) and at three times the rate of women who abstained from alcohol (11.1%). Our study showed high rates of anal sex among binge drinkers compared to 6% of women reporting anal sex in the last 30 days from a household probability sample in California (Erikson et al, 1995). Our 30 day prevalence rates were also high compared to two studies of women from the same geographic region as ours (Baltimore, MD) where 32% of sero-negative women injecting drug users reported anal sex--using a 6 month assessment window (Gross et al., 2000) and 14% of young women (aged 18-24) reported lifetime oral, anal, and vaginal sex (Ompad et al., 2006). Among women from 3 heterosexual STD clinic populations (New Jersey, Colorado, California), 18% reported anal sex within the last 90 days. This rate has more than doubled from rates reported by these same clinics 5 years earlier (Satterwhite et al., 2007).

Unprotected anal sex is the riskiest of sexual behaviors for women. The probability of HIV transmission per contact is estimated to be 10 times higher than for penile-vaginal sex (Erikson et al, 1995) and women report that they are less likely to use condoms during anal sex than vaginal sex (Misegades and Page-Shafer, 2001; Solorio et al., 2006). Anal sex is also associated with anorectal STDs, human papilloma virus-related cancer, and hepatitis B transmission (Friedman et al., 2001; Halperin, 1999). The connection between binge drinking and anal sex has been reported among homosexual men, but has received little attention in women. One exception is the research by Cook and colleagues (2006) where young women, but not young men, STD clinic patients diagnosed with substance abuse/dependence were more likely to engage in anal sex. Clearly, anal sex is a risky sexual behavior for HIV/STDs and a risk that is associated with binge drinking or other alcohol abuse, especially among women.

Women binge drinkers were also more likely to have multiple sex partners in the last 30 days. They were twice as likely to have had multiple sex partners compared to women who did not drink alcohol. This finding is consistent with other STD clinic (Cook et al., 2006, Evans et al., 1997) and general population studies (Graves & Leigh, 1995, Santelli, 1998; Ericksen and Trocki, 1994). Alcohol use is associated with having multiple sex partners, a risky sexual behavior because of the increased likelihood of contracting an STD. Our finding that women binge drinkers had high rates of multiple sex partners, in addition to having a diagnosis of gonorrhea, underscores this association.

Women binge drinkers (10.6%) had nearly five times the rate of gonorrhea compared to women who abstained from alcohol (2.2%). While this association does not prove a causal link between hazardous alcohol use and increased risk of STDs, gonorrhea is an irrefutable biomarker of high risk sex or connection to a high risk sexual network among women binge drinkers. Gonorrhea, typically represents more recently acquired infection (exposures occurring in <60-90 days, given natural clearance) and, compared to other STDs, is more likely to reflect risk behavior in the past 30-90 days. Rates of gonorrhea are higher in women (CDC.GOV, 2007) and the risk of infection during unprotected sexual intercourse is 2- to 4-fold higher than in men (Padian et al., 1997). The health complications from STDs for women are a significant cause of reproductive system morbidity, including pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility (Eng and Butler, 1997).

By contrast, no association was found between binge drinking and other STDs. Syphilis may have been acquired in the past year and chlamydia, which has lower rates in exposed older women, suggests a partial protective immunity in older women who are chlamydia exposed (CDC.GOV, 2007). The difference in the host immune response to each agent (partial protection with CT, no durable immunity with GC) underscores the importance of examining these two infections separately.

Our findings document an intersection of two significant and increasingly prevalent health problems: binge drinking and risky sexual behaviors/STDs (CDC, 2007; Naimi et al., 2003; Satterwhite et al; 2007). Combined alcohol and sexual risk reduction efforts are needed especially among young people where the highest rate of binge drinking coincides with the highest rate of sexual activity/ STDs. This is not to infer, however, a causal relationship between hazardous alcohol use and risky sexual behaviors. While global associations between the two are consistently reported, event level studies which approximate temporal causality have not found a correlation between alcohol and condom use (Bailey et al, 2007; Weinhardt and Carey, 2000). Nonetheless, several studies have reported that alcohol treatment as well as combined HIV and alcohol risk reduction can reduce risky sexual behaviors (Avins et al., 1997; Kalichman et al., 2007, Scheidt and Windle, 1995; Stein et al., 2002). The STD clinic is an ideal setting to test a brief alcohol intervention which has reduced hazardous alcohol use in other settings (Ballesteros et al., 2004; Kaner et al., 2007; Whitlock et al., 2004), as well as to test its effectiveness in reducing risky sexual behaviors and STDs.

Prevention, however, must specifically address the role of gender in alcohol use and risky sexual behavior (Exner et al., 2003; Bryant, 2006). Male-oriented alcohol and STD prevention models are not appropriate for women where issues such as sexual safety or condom negotiation have a different connotation for women than for men (Norris et al., 2004). Our finding that anal sex is more prevalent among women binge drinkers than men binge drinkers suggests the importance of developing targeted prevention strategies for this high risk group of women.

Our study has several strengths. We used a standard definition of hazardous drinking in a large representative sample of STD clinic patients. We used ACASI survey methods for data collection, a method shown to minimize social desirability bias in reporting of socially undesirable behaviors (Ghanem et al., 2005). In addition, the sample had a full clinical evaluation, so that STD diagnosis (an irrefutable maker of risky sexual behavior) supplemented self-reported behavioral data to increase its validity. Our study also has limitations. The design was cross-sectional and therefore we cannot infer causality between binge drinking and adverse outcomes. Second, although study participants were recruited sequentially from clinic admissions, this was essentially a convenience sample. Therefore, it is unknown how representative our sample was of the STD clinic population; however, our large sample size as well as use of ACASI presumably mitigated sampling bias. Third, we used the RBA definition of binge drinking (5 or more drinks per occasion for men or women), which is used by several household surveys and allows for comparison of rates (e.g. Naimi et al., 2003). The binge drinking definition, however, has recently been lowered to 4 or more drinks for women based upon the harmful biologic and behavioral effects observed in women at lower levels of alcohol consumption (NIAAA, 2004). While we believe that we reliably identified women binge drinkers, the use of this lower cutoff would have likely increased the prevalence of binge drinking in the sample. We think that it is unlikely that the hazardous outcomes associated with binge drinking would be found only among those women consuming alcohol at a 5 drink level, but we cannot prove this. Finally, our study described predominantly urban, African-American STD clinic patients and findings may not be generalizable to populations of hazardous drinkers with different characteristics.

Our study has demonstrated that rates of binge drinking among STD clinic patients are high. Among women, binge drinking is uniquely associated with risky sexual behaviors and an STD diagnosis. Our findings support the need to routinely screen for binge drinking as part of standard clinical care in STD clinics, particularly among women. Brief alcohol interventions that would be feasible in the STD clinic setting, however, have received limited evaluation of their effectiveness in reducing both alcohol use and risky sexual behaviors. Developing gender-specific interventions that focus on binge drinking and certain risky sexual behaviors may improve overall health outcomes in this population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH 1 RO1 MH60066-01A1 (Dr. Erbelding) and the Blades Center for Clinical Practice and Research in Alcohol/Drug Dependence. It was presented as a poster session at the 28th Annual Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, Santa Barbara, CA, June 29, 2005. The authors thank Charleen Wylie, BA for recruitment efforts, Lorraine Colleta, CRNP for clinical services provided, and the staff of the Eastern Health District STD Clinic (Baltimore City Health Department) for their support.

References

- 1.Avins AL, Lindan CP, Woods WJ, Hudes ES, Boscarino JA, Kay J, Clark W, Hulley SB. Changes in HIV-related behaviors among heterosexual alcoholics following addiction treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey SL, Gao W, Clark DB. Diary study of substance use and unsafe sex among adolescents with substance use disorders. J Adolesc Health. 2007;38(297):e13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballesteros J, Duffy JC, Querejeta I, Arino J, Gonzalez-Pinto A. Efficacy of brief interventions for hazardous drinkers in primary care: systematic review and meta-analyses. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:608–618. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000122106.84718.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouhnik AD, Preau M, Schiltz MA, Lert F, Obadia Y, Spire B. Unprotected sex in regular partnerships among homosexual men living with HIV: a comparison between sero-nonconcordant and seroconcordant couples (ANRS-EN12-VESPA Study) AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S43–48. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000255084.69846.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant KJ. Expanding research on the role of alcohol consumption and related risk in the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. Subst Use and Misuse. 2006;41:465–507. doi: 10.1080/10826080600846250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sexually transmitted disease Surveillance, 2006. 2007 http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/

- 7.Cook RL, Clark DB. Is There an Association between Alcohol Consumption and Sexually Transmitted Diseases? A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:156–164. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook RL, Comer DM, Wiesenfeld HC, Chang CC, Tarter R, Lave JR, Clark DB. Alcohol and drug use and related disorders: An underrecognized health issue among adolescents and young adults attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:565–570. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000206422.40319.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002:1010–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eng TR, Butler WT, editors. The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Disease. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ericksen KP, Trocki KF. Sex, alcohol, and sexually transmitted diseases: a national survey. Fam Plann Perspect. 1994;26:257–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erikson P, Bastani R, Maxwell AE, Marcus A, Capell F, Yan K. Prevalence of anal sex among heterosexuals in California and its relastinship to oether ADIS risk behavior. AIDS Educ Preven. 1995;7:477–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans BA, Bond RA, MacRae KD. Sexual relationships, risk behaviour, and condom use in the spread of sexually transmitted infections to heterosexual men. Genitourin Med. 1997;73:368–372. doi: 10.1136/sti.73.5.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Exner TM, Dworkin SL, Hoffman S, Ehrhardt AA. Beyond the male condom: the evolution of gender-specific HIV interventions for women. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2003;14:114–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman SR, Flom PL, Kottiri BJ, Neaigus A, Sandoval M, Curtis R, Zenilman JH, Des Jarlais DC. Prevalence and correlates of anal sex with men among young adult women in an inner city minority neighborhood. AIDS. 2001;15:2057–2060. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200110190-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghanem K, Hutton HE, Zenilman JM, Shaw R, Erbelding EJ. Audio computer assisted self-interview and face to face interview modes in assessing response bias among STD clinic patients. Sex Trans Infec. 2005;81:421–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graves KL, Leigh BC. The Relationship of Substance Use to Sexual Activity Among Young Adults in the United States. Fam Plann Perspect. 1995;27:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross M, Holte SE, Marmor M, Mwatha A, Koblin BA, Mayer KH. Anal sex among HIV-seronegative women at high risk of HIV exposure. J AIDS. 2000;24:393–398. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200008010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halperin DT. Heterosexual anal intercourse: prevalence, cultural factors, and HIV infection and other health risks, part I. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 1999;13:717–730. doi: 10.1089/apc.1999.13.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalichman SC, Cain D, Zweben A, Swain G. Sensation seeking, alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among men receiving services at a clinic for sexually transmitted infections. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:564–569. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Cain D, Jooste S, Peltzer K. HIV/AIDS risk reduction counseling for alcohol using sexually tranmitted infections clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;15:594–600. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180415e07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienarr E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, Heather N, Saunders J, Burnand B. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;18:CD004148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Misegades L, Page-Shafer K. Anal intercourse among young low-income women in California: an overlooked risk factor for HIV? AIDS. 2001;15:534–535. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103090-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Denny C, Serdula MK, Marks JS. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA. 2003;289:70–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NIDA . Risk Behavior Assessment. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, Maryland: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.NIAAA Are Women More Vulnerable to Alcohol’s Effects 1999. Alcohol Alert No. 46 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa46.htm

- 27.NIAAA NIAAA Council Approves Definition of Binge Drinking. 2004 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Newsletter/winter2004/ Newsletter_Number3.pdf

- 28.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factor and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clin Psychology Rev. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norris J, Masters NT, Zawacki T. Cognitive mediation of women's sexual decision making: the influence of alcohol, contextual factors, and background variables. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2004;15:258–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nova Research Company . Bethesda, Maryland: http://www.novaresearch.com [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogletree RJ, Dinger MK, Vesely S. Associations between number of lifetime partners and other health behaviors. Am J Health Behav. 2001;225:537–544. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.6.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ompad DC, Strathdee SA, Celenton DD, Latkin C, Poduska JM, Kellam SG, Ialongo NS. Predictors of early initiation of vaginal and oral sex among urban young adults in Baltimore, MD. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:53–65. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-8994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Padian NS, Shiboski SC, Glass SO, Vittinghoff E. Heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in northern California: results from a ten-year study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:350–357. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santelli JS, Brener ND, Lowry R, Bhatt A, Zabin LS. Multiple sexual partners among U.S. adolescents and young adults. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Satterwhite CL, Kamb ML, Metcalf C, Douglas JM, Jr, Malotte CK, Paul S, Peterman TA. Changes in Sexual Behavior and STD Prevalence Among Heterosexual STD Clinic Attendees: 1993–1995 Versus 1999–2000. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:815–819. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31805c751d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheidt DM, Windle M. The alcoholics in treatment HIV risk (ATRISK) study: gender, ethnic and geographic group comparison. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:300–308. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semaan S, Lauby J, O’Connell AA, Cohen A. Factors associated with perceptions of, and decisional balance for, condom use with main partner among women at risk for HIV infection. Women Health. 2003;37:53–69. doi: 10.1300/J013v37n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solorio MR, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MH, Gelberg L. Predictors of sexually transmitted infection testing among sexually active homeless youth. AIDS and Behav. 2006;10:179–184. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9044-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.SPSS . Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. Version 15.0.1. Chicago, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein MD, Anderson B, Charuvastra A, Maksad J, Friedmann PD. A brief intervention for hazardous drinkers in a needle exchange program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP. Does alcohol lead to sexual risk behavior? Findings from event level research. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:125–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:557–568. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zenilman JM, Hook EW, 3rd, Shepherd M, Smith P, Rompalo AM, Celentano DD. Alcohol and other substance use in STD clinic patients: relationships with STDs and prevalent HIV infection. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21:220–225. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]