Abstract

Sequence-specific recognition of DNA is a critical step in gene targeting. Here we describe unique oligonucleotide (ON) hybrids that can stably pair to both strands of a linear DNA target in a RecA-dependent reaction with ATP or ATPγS. One strand of the hybrids is a 30-mer DNA ON that contains a 15-nt-long A/T-rich central core. The core sequence, which is substituted with 2-aminoadenine and 2-thiothymine, is weakly hybridized to complementary locked nucleic acid or 2′-OMe RNA ONs that are also substituted with the same base analogs. Robust targeting reactions took place in the presence of ATPγS and generated metastable double D-loop joints. Since the hybrids had pseudocomplementary character, the component ONs hybridized less strongly to each other than to complementary target DNA sequences composed of regular bases. This difference in pairing strength promoted the formation of joints capable of accommodating a single mismatch. If similar joints can form in vivo, virtually any A/T-rich site in genomic DNA could be selectively targeted. By designing the constructs so that the DNA ON is mismatched to its complementary sequence in DNA, joint formation might allow the ON to function as a template for targeted point mutation and gene correction.

INTRODUCTION

A robust method for recognizing and tagging arbitrary sequences in double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) has not yet been developed despite the efforts of many investigators. With base pairing sequestering the Watson–Crick determinants of dsDNA, sequence recognition is usually limited to base determinants present in the major and minor grooves. Triplex-forming oligonucleotides (TFOs) can form stable, sequence-specific triple-stranded complexes with homopurine runs in dsDNA according to three different recognition motifs (1–3). Unfortunately, interruptions in a homopurine run can significantly destabilize such complexes. Development of base analogs that can bridge such interruptions has met with limited success. TFOs with a separate Watson–Crick domain can extend targeting to a mixed-sequence DNA that is adjacent to a homopurine run (4,5). Superhelicity in the target DNA facilitates strand invasion of such sequences and leads to the formation of a D-loop joint. Approaches also exist for recognizing determinants in the minor groove of dsDNA. Polyamides (6,7) and zinc finger domains (8,9) are promising strategies that are currently being developed.

Strand invasion of the double helix by peptide nucleic acid (PNA) provides an alternative route to sequence recognition that is based upon Watson–Crick pairing. PNA is a synthetic variant of DNA and RNA in which the bases are attached to a neutral peptide backbone (10). It has a high affinity for complementary sequences due to the absence of electrostatic repulsion. Bis-PNA consists of two domains, one which Hoogsteen pairs to a homopurine run in dsDNA and the other that strand invades the target duplex and Watson–Crick pairs to the same homopurine run (11,12). Bis-PNAs with a mixed-base extension can also strand invade dsDNA adjacent to the homopurine run (13,14). Recently, direct strand invasion of a mixed-sequence DNA has been reported for γ-PNA, a variant of PNA that is conformationally preorganized to form exceptionally stable hybrids (15).

Pseudocomplementary PNAs (pcPNAs) are short A/T-rich oligomers that contain 2-aminoadenine (nA) in place of adenine (A) and 2-thiothymine (sT) in place of thymine (T) (16,17). Whereas nA-sT is a mismatch due to steric clash between the 2-amino group of nA and the 2-thioketo group of sT, nA-T and A-sT are stable base pairs (Figure 1A) (18). This is particularly true for the nA-T base pair, which contains three hydrogen bonds instead of two. Complementary pcPNAs have reduced affinity for one another but high affinity for unmodified DNA or RNA complements. These paired oligonucleotides (ONs) can hybridize to the complementary strands of a homologous dsDNA. Like all other PNA constructs that invade dsDNA, complex formation by pcPNAs is enhanced by introducing positive charge to the backbone (19) and by conducting the reaction in low-ionic-strength buffer without magnesium (16). A similar reaction can take place in cells (20), but its initiation is probably dependent upon transient opening of the dsDNA target during normal enzymatic processing of the genetic material.

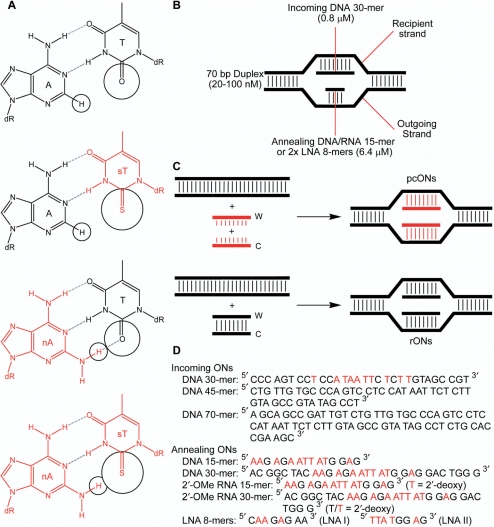

Figure 1.

(A) Pseudocomplementary pairing of nA and sT. (B) A double D-loop joint, with each strand identified according to its role in RecA-mediated joint formation. (C) Formation of a double D-loop joint with pseudocomplementary ONs (pcONs; in red) creates additional base pairs. Formation of the same joint with regular ONs (rONs; in black) does not alter the number of base pairs. (D) Incoming and annealing oligonucleotides used in this study for strand exchange and double D-loop joint formation. A and T bases in red are replaced by nA and sT analogs in pseudocomplementary versions of the respective ONs. The T/sT bases in annealing ONs with a 2′-OMe RNA backbone were attached to 2′-deoxyribose sugars. DNA duplexes were formed by hybridizing an incoming DNA 30-mer, 45-mer or 70-mer to a complement of the same length. Specificity of joint molecule formation was determined using 70-bp DNA targets that were mismatched to the incoming/annealing ONs.

Design of longer pseudocomplementary ONs (pcONs) that can be actively inserted into dsDNA by genetic recombination should improve the efficiency and specificity of gene targeting, as well as the stability of the resulting double D-loop joints (Figure 1B). Recombinases, exemplified by the RecA protein from Escherichia coli, catalyze strand exchange (21,22). In the presence of ATP, RecA protein associates with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) to form a stable helical filament. This filament can rapidly scan dsDNA for homology by transiently extending and unwinding the duplex so that the resident ssDNA can repetitively sample the antiparallel strand of the donor duplex for complementarity by Watson–Crick base pairing. Upon homologous alignment, strand exchange produces a new heteroduplex (23–25). Utilizing this pathway, RecA protein can form a D-loop joint at any arbitrary site in a superhelical DNA when provided with an incoming DNA ON that is complementary to the site and has sufficient length (26,27). This reaction is very efficient in the presence of ATPγS and less so in the presence of ATP. Although RecA protein catalyzes D-loop formation in linear dsDNA, deproteinization leads to rapid branch migration and release of the ON. We have previously shown that the displaced strand in a RecA-stabilized D-loop can hybridize to a complementary ON provided that it has an RNA-like backbone and is shorter than the incoming DNA oligomer (28). This reaction leads to a four-stranded double D-loop joint that can survive deproteinization even when present in a linear dsDNA. In theory, such joints could be formed at any arbitrary site in dsDNA.

RecA-mediated formation of a double D-loop joint requires that the two ONs be added sequentially; otherwise they form a hybrid with each other that inhibits the initial strand exchange reaction. While sequential addition of paired ONs is acceptable for in vitro applications, it cannot be carried out in vivo. In this study we show that RecA protein can catalyze double D-loop formation by paired A/T-rich pcONs in a concerted one-step reaction. Even though such ONs, which are substituted with nA and sT, may weakly hybridize to each other, RecA protein can utilize the complex for initiating strand exchange. Joint formation with pcONs is accompanied by a net increase in base pairing, and this partly offsets the electrostatic and entropic penalties associated with forming a four-stranded complex (Figure 1C). The resulting double D-loop joints are metastable structures long enough to ensure good specificity across the genome, although we show that the joints can tolerate a single mismatch between the incoming DNA ON and the complementary strand of the target dsDNA. If eukaryotic recombinases can catalyze the same reaction in vivo, such joints might function as templates for the correction of deleterious point mutations in living cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nucleic acid substrates

Standard ONs with DNA or 2′-OMe RNA backbones were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Standard locked nucleic acids (LNAs) were provided by Sigma-Proligo (Paris, France). Modified ONs containing nA and sT bases with DNA or 2′-OMe RNA backbones were synthesized and purified by TriLink Biotechnologies (San Diego, CA). LNAs substituted with nA and sT bases were prepared for Sigma-Proligo by Exiqon A/S (Vedbæk, Denmark). 32P-labeled ONs were prepared according to standard protocols using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA) and γ-[32P]-ATP (Perkin Elmer, Walthman, MA). Target duplex was formed by annealing complementary strands (2:1 molar ratio of cold to hot) in hybridization buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA). After electrophoresis in a nondenaturing 12% polyacrylamide gel run at 8°C in 90 mM Tris–borate buffer with 1 mM MgCl2, the double-stranded product was recovered from a gel slice by shaking overnight at 4°C in Tris–EDTA and then further purified through a Sep-Pak light C18 cartridge (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). After drying in a Speed-Vac (ThermoSavant, Holbrook, NY) at room temperature, the dsDNA was dissolved in water or 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, and stored at −20°C. Prior to use, a fresh aliquot of the dsDNA stock was diluted to 20 nM in hybridization buffer and analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) to confirm its double-stranded character. Typically, the dsDNA target was contaminated with less than 10% labeled single strand.

Melting point determinations

Equimolar concentrations of 15-mer Watson and Crick strands (1 μM each) in physiological buffer (PB; 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7.2, 0.1 mM MgCl2, 140 mM KCl) were heated to 90°C for 2 min and cooled gradually to 15°C. The temperature was increased linearly to 90°C at 1°C/min as the absorbance at 260 nm was recorded every 0.5 min in a Varian Cary 3 UV/Visible spectrophotometer (Palo Alto, CA) interfaced with a Peltier temperature controller. Melting temperature (Tm) was then assigned as the peak of the first derivative plot using the CaryWin software. Thermal denaturation of 30-bp hybrids was determined as described above; however, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and 25 mM NaCl were substituted for the PB.

Analysis of pairing between complementary ONs

In order to determine the hybridization status of incoming and annealing ONs under strand exchange conditions, radiolabeled 30-mer DNA (0.8 pmol) was incubated with cold annealing ON (6.4 pmol) for 10 min at 37°C in 10 μl of strand exchange buffer (SEB; 1 mM Mg(OAc)2, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 25 mM Tris–OAc buffer, pH 7.2). The reactions were quenched with 64 pmol cold competitor ON that was identical to the incoming ON, placed in an ice bath and electrophoresed at 8°C in a 12% polyacrylamide gel containing 1 mM MgCl2. A second set of reactions were directly analyzed without added competitor in a 12% polyacrylamide gel preequilibrated to 37°C and run at room temperature in the presence of 1 mM MgCl2. Radioactive bands were detected by autoradiography. Gel images were acquired on a Storm phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA), and bands were quantified using ImageQuant software.

Strand exchange

Incoming DNA ONs (0.8 pmol; 30, 45 or 70 bases in length) were incubated with RecA protein (USB Corp., Cleveland, OH; 1:1 ratio of monomer to nucleotide) for 10 min at 37°C in 8 μl SEB with 1 mM ATPγS, 2 mM ATP or an ATP-regenerating system (2 mM ATP, 20 mM phosphocreatine and 0.1 unit creatine kinase). Strand exchange was initiated by adding radiolabeled dsDNA (180 fmol; 30, 45 or 70 bp in length) and adjusting the Mg(OAc)2 concentration to 10 mM. After 10 min at 37°C, the reaction mixture (10 μl) was placed in an ice bath, mixed with 0.1 volume of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and analyzed by 12% PAGE in the presence of 1 mM MgCl2 at 8°C.

Double D-loop formation

Unless otherwise noted, the three-step protocol described in Gamper et al. (28) was followed. Briefly, a single-stranded incoming DNA 30-mer (0.8 pmol) was incubated for 10 min at 37°C with 24 pmol of RecA protein in 8 μl of SEB supplemented with 1 mM ATPγS unless otherwise specified. The incoming ON was homologous to the middle of the dsDNA target so that strand exchange formed a RecA-stabilized D-loop. Exchange was initiated by adding radiolabeled dsDNA (70 bp in length, 40 fmol) and increasing the Mg(OAc)2 concentration to 10 mM. After 10 min at 37°C, annealing ON (6.4 pmol) was added with 10-min additional incubation. This ON hybridized to the outgoing strand of the synaptic complex to form a RecA-associated double D-loop joint. The reaction mixture (12 μl) was cooled in an ice bath, mixed with 0.1 volume of 1% SDS and analyzed electrophoretically as described above. Modification of this procedure resulted in simplified protocols. In the two-step protocol, the incoming and annealing ONs were premixed before adding the RecA protein, and in the one-step protocol all nucleic acids were present before adding the RecA protein. The yield of joint molecule was unaffected by conducting the entire reaction in 10 mM Mg(OAc)2 versus raising the concentration from 1 to 10 mM after 10-min incubation.

Specificity of double D-loop formation

Specificity was evaluated using the three-step protocol. We attempted to form double D-loop joints that contained one, two or three mismatched base pairs in both arms of the joint by using altered 70-bp DNA targets. These duplexes contained one [(T:A→A:T)35], two [(G:C→ T : A)32 and (T : A→A : T)35] or three [(G : C→T : A)32, (T:A→A:T)35 and (T:A→A:T)38] base pair substitutions relative to the standard target. A fourth altered target contained a mismatched base pair [(T:T)35] such that only one arm of the joint contained a mismatch.

Half-life of protein-free double D-loop joints

Joints prepared with RecA protein according to the three-step protocol were treated with 0.1 volume of 1% SDS and exchanged into PB by centrifugation through a gel filtration column (CentriSpin-20; Princeton Separations, Adelphia, NJ). Double D-loop joints possessing identical length incoming and annealing ONs were prepared by sequential hybridization in the same buffer. Briefly, Watson–Crick (recipient–incoming and outgoing–annealing) strands were separately hybridized to each other in PB by heating to 90°C and slowly cooling to room temperature. The two solutions were then combined and cooled to 4°C in an ice bath. The radiolabeled protein-free joints were incubated at 37°C for the indicated time (up to 5 days) and quenched on ice. Samples were stored at −20°C until electrophoretic analysis. The ratio of double D-loop joint to target duplex was plotted as a function of time and fit to an exponential curve using KaleidaGraph version 3.6 (Synergy Software, Reading, PA). Half-lives were calculated from the following equation: t1/2 (h) = ln2/decay constant (h−1).

RESULTS

Model system

The ONs used to characterize RecA-mediated joint formation by paired pcONs are listed in Figure 1D. Two A/T-rich dsDNA targets were primarily used: one 30 bp long for carrying out strand exchange studies and the other 70 bp long for forming double D-loop joints. The shorter target replicated the central sequence of the longer target and was prepared by annealing two complementary 30-mers followed by gel purification of the hybrid. The 70-bp target was similarly prepared using 70-mers. Unless otherwise indicated, the double-stranded targets were composed of regular bases. The design of paired pcONs suitable for use with RecA protein was guided by our earlier study of recombinase-mediated double D-loop formation using unmodified ONs (28). Incoming ONs, which were homologous to the double-stranded targets, had a DNA backbone that was at least 30 nt long. The incoming 30-mer was used in most of our studies and was synthesized with either A and T or nA and sT bases in the central A/T-rich core. Annealing ONs were complementary to the core sequence of the incoming ON and contained either A and T or nA and sT bases. Annealing ONs with a DNA or 2′-OMe RNA backbone were 15 nt long, while those with a LNA backbone were 8 nt long. LNA is an RNA mimic in which the ribose moiety has an extra bridge between the 2′ and 4′ carbons (29). The bicyclic sugar of LNA is locked into the 3′-endo conformation, and this confers high affinity for complementary DNA or RNA sequences. Use of relatively short annealing ONs met the requirement for these ONs being shorter than the incoming ON and helped to conserve the use of expensive nA and sT phosphoramidites. Use of annealing ONs with an RNA-like backbone provided two benefits. First, the backbone prevented filament formation with recombinase (30), thereby ensuring unhindered access of the annealing ON to the synaptic complex. Second, it prevented dissociation of the double D-loop joint by blocking recombinase-mediated inverse strand exchange (28,31). Incoming and annealing ONs were designated as regular (rONs) or pseudo-complementary (pcONs) based on the absence or presence of nA and sT bases. Formation of double D-loop joints by sequential hybridization permitted the use of annealing ONs that were equal in length to the incoming ON. Where indicated, a limited number of experiments utilized incoming and annealing ONs that were completely substituted with nA and sT.

Analysis of pairing between complementary ONs

Hybridization properties of selected incoming and annealing ONs were determined by measuring the melting temperatures of Watson–Crick hybrids in PB (Table 1). The 15-bp DNA hybrids behaved as expected. Substitution of one strand with nA and sT increased the Tm from 36 to 48°C, while substitution of both strands reduced the Tm by at least 25°C. Hybrids that contained a 15-mer 2′-OMe RNA or two 8-mer LNAs hybridized to a complementary 15-mer or 30-mer DNA responded differently. When the RNA-like strand was substituted with nA and sT, the increase in Tm was 24°C for the 2′-OMe pseudocomplementary RNA (pcRNA) containing hybrid and 35°C for the pseudocomplementary LNA (pcLNA) containing hybrid. Stabilization of this magnitude underscores the preference of both nA and sT for an A-form duplex (32–34). Indeed, in RNA the 2-thiouracil pair with adenine is one of the most stable base pairs known. Because of this preference, substitution of both strands of the mixed hybrids with nA and sT was less destabilizing than for the all-DNA hybrid. In the hybrid with 2′-OMe pcRNA, the Tm decreased by 10°C, while in the hybrid with two 8-mer pcLNA strands, the Tm actually increased by 1°C. In these hybrids, steric clash between nA and sT was not as destabilizing as in the DNA hybrid. Since the conditions used for double D-loop formation could not be replicated in the melting analysis, the Tm's do not predict the pairing state of the pcONs during strand exchange. However, the results do predict that pcONs should form more stable double D-loop joints than rONs. The results also show that complementary nA/sT-substituted ONs are more likely to hybridize to one another if one of the ONs has an RNA-like backbone.

Table 1.

Optical melting of complementary ONs with regular and pseudocomplementary A/T bases

| Duplexesa (incoming:annealing) | Tm (°C) | ΔTm (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| rDNA15 : rDNA15 | 36.4 | – |

| rDNA15 : pcDNA15 | 48.0 | 11.6 |

| rDNA15 : rRNA15 | 39.0 | 2.6 |

| rDNA15 : pcRNA15 | 63.3 | 26.9 |

| pcDNA15 : pcDNA15 | No melt | – |

| pcDNA15 : pcRNA15 | 29.0 | −7.4 |

| rDNA30 : rLNA16 | 41.5 | 5.1 |

| rDNA30 : pcLNA16 | 76.8 | 40.4 |

| pcDNA30 : pcLNA16 | 42.5 | 6.1 |

| rDNA30 : rDNA30b | 63.5 | – |

| rDNA30 : pcDNA30b | 67.5 | 4.0 |

aAll hybrids replicate the sequence of the model double D-loop joint.

bThese hybrids were melted in the presence of 20 mM KC1 instead of 140 mM KC1.

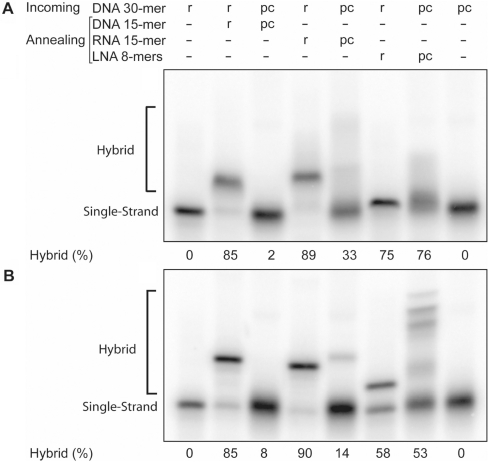

To ascertain whether the incoming and annealing pcONs could hybridize to each other under strand exchange conditions, mock reactions that contained 0.8 μM incoming ON (with a 32P tag) and 6.4 μM annealing ON were equilibrated at 37°C. The pairing state of the incoming ON was estimated by electrophoresis of reaction aliquots in nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels. In the first panel of Figure 2, aliquots were loaded onto a 12% gel previously adjusted to 37°C and then run at room temperature. In the second panel, the reactions were quenched by adding competitor ON (64 μM; identical to the incoming ON) and quickly placing the reactions in an ice bath. Aliquots were then loaded onto a 12% gel run in the cold room. Both analyses confirmed that the incoming pseudocomplementary DNA (pcDNA) was single stranded when the annealing pcON had a DNA backbone, but that an appreciable fraction was hybridized when the annealing pcON had a 2′-OMeRNA or LNA backbone. Due to dissociation and exchange reactions that took place during analysis, the amount of hybrid detected in these gels probably underestimates what was present in the original solutions. The unusual banding pattern observed for the pcDNA–pcLNA complex in the second panel of Figure 2 is probably attributable to triple-strand formation with an imperfect homopurine run present in the target.

Figure 2.

Gel mobility shift analysis of hybridization between incoming and annealing ONs. Complementary ONs (80 nM radiolabeled incoming ON and 640 nM annealing ON) were incubated 10 min at 37°C in SEB. In panel A, aliquots were directly analyzed by PAGE in a gel preequilibrated at 37°C. In panel B, reactions were quenched by adding 6.4 μM competitor ON and then placed in an ice bath until analyzed by PAGE at 8°C. The base composition of each ON (r = regular bases; pc = substitution with nA and sT bases) is indicated above each lane.

Strand exchange

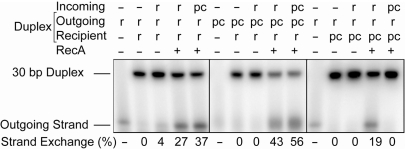

Although RecA protein can carry out strand exchange with DNAs that contain different base analogs (35–37), the effect of nA and sT on this reaction has not been investigated. We, therefore, investigated RecA-mediated strand exchange between 30-mer DNA substrates in which one or more strands contained a central pseudocomplementary domain as shown in Figure 1D. Presynaptic filament formation and strand exchange were carried out in the presence of ATPγS. Release of radiolabeled outgoing strand from the target duplex was monitored by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis of deproteinized reaction aliquots (Figure 3). While substitution of any one strand with nA and sT did not inhibit strand exchange, it did alter the yield by changing the relative stabilities of the starting and ending duplexes. Keeping in mind that pc–r hybrids are more stable than r–r hybrids, an incoming pcON gave enhanced strand exchange with an r–r duplex, while an incoming rON gave reduced strand exchange when the duplex had an outgoing pcON. For unknown reasons, when both the incoming and outgoing strands were pseudocomplementary, the extent of strand exchange was unexpectedly high. Conversely, no strand exchange was observed when both the incoming and recipient strands were pseudocomplementary. This, of course, was expected since these strands would not be expected to form a very stable duplex.

Figure 3.

RecA-mediated strand exchange of DNA substituted with nA and sT in the presence of ATPγS. Exchange was monitored using an incoming 30-mer DNA and a homologous 30-bp DNA duplex that was radiolabeled in the outgoing strand. The base composition of each strand (r = regular bases; pc = substitution with nA and sT bases) is indicated above each lane.

Double D-loop formation using a three-step protocol

A radiolabeled 70-bp DNA with regular bases was used as a substrate for studying double D-loop formation by rONs and pcONs. This duplex supported joint formation without itself dissociating into component strands. Based on our earlier study (28), we first used a three-step protocol for forming joints. In the first step, RecA protein was incubated with an incoming DNA 30-mer in the presence of ATPγS to form a presynaptic filament. In the second step, the 70-bp DNA target was added along with additional magnesium acetate to form a synaptic complex with an underlying D-loop joint. In the third step, annealing ON (with a DNA- or an RNA-like backbone) was hybridized to the displaced strand of the synaptic complex. Following treatment with SDS, an aliquot of each reaction was analyzed by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis to detect double D-loop joint (Figure 4). Unlike the G/C-rich target used previously by us, the A/T-rich target employed here did not support efficient joint formation by rONs regardless of the type of backbone in the annealing rON. Hybrid stability of the component arms of the double D-loop joint may have been too weak to survive removal of RecA protein. In contrast, all three pairs of pcONs formed double D-loop joints. Annealing pcONs with a 2′-OMe RNA or LNA backbone were nearly twice as effective in trapping the displaced strand of the D-loop as a pcON with a DNA backbone. Enhanced stability of the hybrid between outgoing and annealing strands and resistance of the double D-loop joint to RecA-mediated inverse strand exchange probably account for the superior performance of annealing pcONs with an RNA-like backbone. It is worthwhile noting that joint formation with the RNA-like annealing ONs proceeded to a greater extent than strand exchange (Figure 3). One possible explanation is that strand exchange is enhanced by the presence of an annealing pcON since under these conditions, the RecA-stabilized D-loop is immediately converted to a double D-loop joint, thus driving the strand exchange reaction.

Figure 4.

RecA-mediated double D-loop formation in the presence of ATPγS. Different combinations of incoming and annealing ONs with regular (r) or pseudocomplementary (pc) bases were tested for joint formation with radiolabeled 70-bp DNA target using a three-step reaction protocol. A sequential hybridization reaction is analyzed in the last lane on the right.

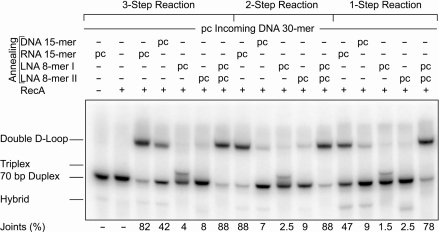

Double D-loop formation using two- and one-step protocols

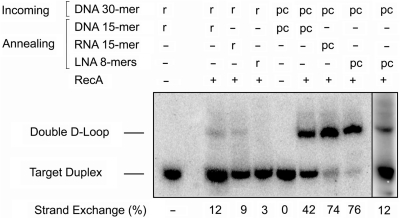

We next simplified the reaction protocol by starting out with both incoming and annealing ONs present. In the two-step protocol, RecA protein was added to form presynaptic filament and then dsDNA target was added to initiate double D-loop formation. In the one-step protocol, dsDNA was also present when RecA protein was added. Figure 5 compares the yields of double D-loop joint for the one-, two- and three-step protocols when annealing pcONs with DNA, 2′-OMe RNA and LNA backbones were used in combination with an incoming pcDNA 30-mer. All protocols were conducted in the presence of ATPγS, and in all three the concentration of magnesium acetate was adjusted from 1 to 10 mM after formation of presynaptic filament. Regardless of the protocol, annealing ONs with a 2′-OMe pcRNA or pcLNA backbone gave 80–90% yields of double D-loop joint. In contrast, when the annealing ON had a pcDNA backbone, the yield of joint was 40% in the three-step protocol and less than 10% in the one- and two-step protocols. These results suggest that RecA protein is able to initiate strand exchange with the incoming pcDNA 30-mer even though it is partly hybridized to annealing pcONs with an RNA-like backbone. Loss of joint molecules by inverse strand exchange may account for the low yield obtained with the pcDNA annealing ON. The poor reaction observed when using only one of the annealing pcLNA 8-mers suggests that the pcLNA–rDNA arm of the double D-loop joint was too weak to survive deproteinization. The aberrant band observed with pcLNA I is the result of triple-strand formation with an imperfect homopurine run in the dsDNA target. In summary, the one-step protocol serves as a harbinger for whether complementary pcONs might be used in vivo to form a double D-loop joint. In this reaction, only the 2′-OMe pcRNA 15-mer and the two pcLNA 8-mers supported a good yield of joint. Although not shown, use of regular incoming and annealing ONs in the one-step protocol did not generate double D-loop joint.

Figure 5.

Comparison of RecA-mediated double D-loop formation using one-, two- and three-step reaction protocols with ATPγS. Pseudocomplementary incoming and annealing ONs were used to target radiolabeled 70-bp DNA duplex. The fast moving band in some of the lanes is a hybrid between the outgoing DNA 70-mer and the indicated annealing ON.

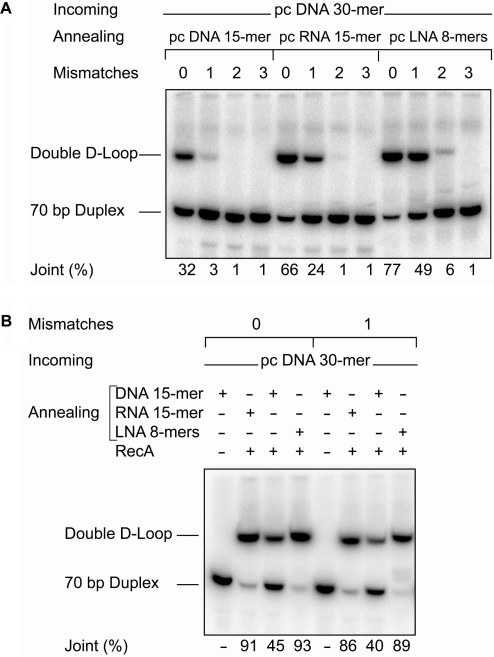

Specificity of double D-loop formation

Synaptic complexes readily accommodate mismatches between the incoming and recipient strands of a newly formed duplex (38,39). In such complexes, the free energy penalty associated with a mismatch is only 0.8–1.9 kcal/mol, a value much reduced relative to naked dsDNA. Since the incoming ON of a double D-loop joint is incorporated into DNA by strand exchange, it should be straightforward to prepare joints in which the incoming ON is also mismatched to its complement. Introduction of a mismatch between the annealing ON and the outgoing strand of the duplex should also be possible, but the reduced length of these ONs should limit the number of mismatches allowed. The ability of paired pcONs to form double D-loop joints with one, two or three mismatches in each arm of the joint was determined by gel mobility shift analysis of reactions conducted according to the three-step protocol (Figure 6A). Only joints with a single mismatch in each arm were obtained in good yield, and this required the use of annealing pcONs with a high-affinity RNA-like backbone. When the mismatch was restricted to the hybrid between incoming and recipient strands, double D-loop formation was supported by all three annealing pcONs (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Specificity of RecA-mediated double D-loop formation. Joints were formed using the three-step reaction protocol with pseudocomplementary incoming and annealing ONs and ATPγS. In panel A, the altered 70-bp DNA targets were mismatched to both the ONs at one, two or three positions. In panel B, the altered 70-bp DNA target contained a mismatched base pair such that the annealing–outgoing arm of the double D-loop joint was perfectly matched, while the incoming–recipient arm contained a single mismatch.

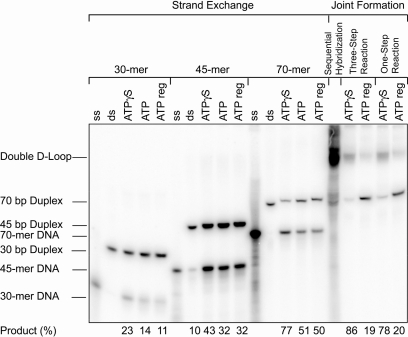

Strand exchange and double D-loop formation in the presence of ATP

RecA-catalyzed strand exchange reactions with incoming ONs are usually carried out in the presence of ATPγS. This slowly hydrolyzable analog of ATP stabilizes short presynaptic filaments and enhances strand exchange. Given the potential use of pcONs as gene repair agents, we evaluated both strand exchange and double D-loop joint formation when ATPγS was replaced by ATP (Figure 7). From a series of strand exchange reactions using 30-mer, 45-mer and 70-mer incoming rDNA ONs with dsDNA targets of the same length, three conclusions can be drawn. First, strand exchange was reduced by 25–50% when ATP was substituted for ATPγS. Second, an ATP regeneration system did not improve upon ATP alone. Third, strand exchange was more efficient with longer substrates. Double D-loop formation using the pcDNA incoming 30-mer and the two pcLNA annealing 8-mers was reduced to an even greater extent. In both the three-step and one-step protocols, joint formation was reduced by approximately 75% when ATPγS was replaced by an ATP regeneration system. Others have observed a similar decrease in synaptic complex formation when switching from ATPγS to ATP (27).

Figure 7.

RecA-mediated pairing in the presence of ATP. Strand exchange and double D-loop formation were conducted in the presence of ATPγS, ATP or an ATP regenerating system. Strand exchange was conducted with regular incoming ONs whereas joint molecules were formed with pseudocomplementary incoming and annealing ONs.

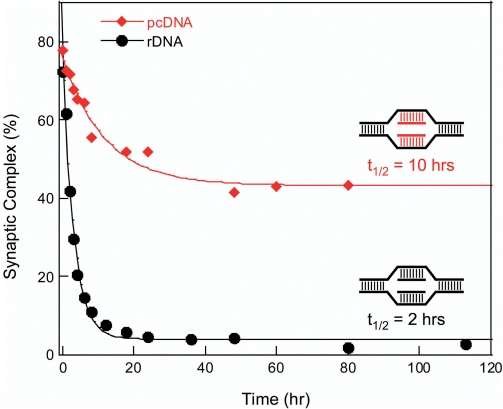

Stability of protein-free double D-loop joints

Multiarm structures in DNA are susceptible to resolution by branch migration, and double D-loop joints are no exception. Since the rate of branch migration is highly dependent on temperature, we were able to monitor dissociation of joints as a function of time at 37°C by removing aliquots into an ice bath prior to electrophoretic analysis in a cold room. Joints in which the incoming ON was longer than the annealing ON were prepared using RecA protein, while joints in which both ONs had the same length were prepared by sequential hybridization. In this method, each ON was separately hybridized to its complementary DNA target strand followed by mixing the two solutions to form the desired joint. Decay of two representative double D-loop joints in a PB is presented in Figure 8. One joint contained pcDNA 30-mers (in this case, completely substituted with nA and sT) and the other contained rDNA 30-mers. Whereas the unmodified joint completely dissociated with a half-life of 2 h, the joint substituted with nA and sT consisted of two components, one with a half-life of 10.5 h and the other stable to dissociation. Joints formed with other pcONs showed a similar behavior regardless of how they were prepared. During gel electrophoresis the two types of joint comigrated suggesting that they differed from one another in subtle ways. We presume that the stable component is an authentic double D-loop joint. The structure of the less stable component has not been determined but we assume that it contained both pcONs.

Figure 8.

Stability of double D-loop joints at 37°C in PB buffer. The joints were prepared by sequential hybridization between regular or pseudocomplementary incoming and annealing DNA 30-mers and complementary 70-mer DNA strands.

Results for the different joints are summarized in Table 2. Two parameters are listed for each pair of incoming and annealing ONs: the percentage of total joint that is stable and the half-life of the unstable complex. In general, longer half-lives were usually associated with greater yields of stable double D-loop joint. The most stable joints contained 30-mer incoming and annealing ONs that were completely substituted with nA and sT. Limiting substitution of nA and sT to the central core of these ONs reduced both the half-life of the unstable joint and the yield of the stable joint. Use of shorter annealing pcONs reduced these parameters still more. Joints that contained a single mismatch in each arm were relatively unstable and had half-lives of approximately 30 min. The one exception was a mismatched joint that contained an annealing ON with a 2′-OMe pcRNA backbone; this joint had a half-life of 5.3 h.

Table 2.

Dissociation of double D-loop joints under physiological conditions

| Incoming ON | Annealing ON | Stable joint (%) | t½ (h) of unstable joint |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30-mer rDNA | 30-mer rDNAb | 6 | 2.2 |

| 30-mer rRNAb | 6 | 1.8 | |

| 30-mer pcDNAb | 48 | 4.6 | |

| 30-mer pcDNA | 30-mer pcRNAb | 40 | 3.3 |

| 15-mer pcDNAc | 21 | 3.5 | |

| 15-mer pcRNAc | 24 | 6.5 | |

| 2 × (8-mer pcLNA)c | 24 | 5.8 | |

| 30-mer pcDNA with one mismatch | 15-mer pcDNAc | 15 | 0.5 |

| 15-mer pcRNAc | 5 | 5.3 | |

| 2 × (8-mer pcLNA)c | 5 | 0.6 | |

| 30-mer pcDNA with two mismatches | 2 × (8-mer pcLNA)c | 5 | 0.5 |

| 30-mer pcDNAa | 30-mer pcDNAa,b | 56 | 10.5 |

| 30-mer pcRNAa,b | 55 | 4.1 |

aEvery A/T base in these ONs was replaced by nA and sT.

bJoints formed by sequential hybridization.

cJoint formation mediated by RecA protein.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that ONs with pseudocomplementary properties can be utilized by RecA protein to target dsDNA in a single reaction with all substrates present. The resulting complement-stabilized double D-loop joints are unusually stable and can accommodate a single base pair mismatch in the all-DNA arm of the joint. Key to success was using an incoming ON with a DNA backbone and a shorter annealing ON with an RNA-like backbone. In the presence of RecA protein, these pcON pairs readily invaded homologous dsDNA even when weakly complexed to each other. It is conceivable that the incoming pcON exists in both single-stranded and hybridized states, in which case the single-strand would be an obvious substrate for presynaptic filament formation with RecA protein. Otherwise, we postulate that RecA protein could displace the annealing ON from the incoming ON in the course of forming a presynaptic filament or that it could use the hybrid itself to initiate strand exchange. In the latter case, strand invasion and double D-loop formation would occur simultaneously. The exceptional stability of the hybrid between rDNA and pcLNA (and to a lesser extent 2′-OMe pcRNA) is noteworthy and thermodynamically favors double D-loop formation. If paired pcONs can function with eukaryotic recombinase to target specific sequences in the chromosomal DNA of living cells, then joints with a mismatch might function as templates for correcting deleterious mutations. In this context, only mismatched ONs with a DNA backbone can support targeted point mutation of the host DNA (40).

Many studies have reported that nuclease-resistant ssDNA ONs can be used to address the Watson–Crick determinants of dsDNA in cultured cells (41). Two mechanisms for recognition have been proposed, one involving recombinase-mediated strand exchange (42) and the other relying on transient opening of the DNA during replication or transcription (43,44). In either case, the ON is postulated to form a labile D-loop-like structure that could be stabilized by nucleolytic digestion of the displaced strand (45). If the ON is mismatched to its complement, repair of the joint can be accompanied by a targeted base pair change. Targeted mutagenesis, which usually occurs at very low frequency, can be enhanced in the presence of a nearby triple-stranded complex (3,5,46). Paired pcONs may provide an alternative and possibly more effective way for introducing point mutations into dsDNA in vivo.

For a time DNA–2′-OMe RNA dumbbells with an internal nick were promoted as nuclease-resistant gene repair agents (41). Numerous studies have since shown that these agents are inferior to capped ssDNA ONs. Although a chimeric DNA–RNA dumbbell can be used by RecA protein to form double D-loop joint in DNA (40), the pairing reaction is very inefficient because RecA protein does not readily catalyze four-strand exchange reactions (47). The short hybrids used here have ssDNA overhangs extending from a core DNA–LNA or DNA–2′-OMe RNA duplex that is in turn destabilized by nA–sT couples. These differences lead to improved utilization of the hybrids by RecA protein.

Use of pcONs that contain regular G and C bases necessarily limits targeting to A/T-rich sequences. In a previous study of double D-loop joint formation using paired pcPNAs in the absence of protein, it was concluded that sequences with 40% or greater A/T content could be invaded by nA/sT-substituted PNAs in low-ionic-strength buffer lacking divalent cation (16). A similar A/T content will probably be required for recombinase-mediated delivery of nA/sT-substituted pcONs to dsDNA. We recently described a set of G-C analogs that exhibit pseudocomplementary properties and function with nA and sT to generate structure-free DNA (48). Synthetic ONs in which all four bases are pseudocomplementary could potentially extend RecA-mediated gene targeting to G/C-rich sequences.

The results described here represent a first step in evaluating pcONs as potential DNA targeting and gene repair agents. In all likelihood, eukaryotic recombinases will require the use of longer incoming pcDNAs and annealing pcRNAs that could be prepared, respectively, by asymmetric PCR or transcription (48,49). With increased size, double D-loop joints should form more readily and exhibit greater stability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS Grant 74564 to H.G.) and Thomas Jefferson University (REA Award 080-02000-A87401 to H.G.). Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health GM74564.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Helene C. The anti-gene strategy: control of gene expression by triplex-forming-oligonucleotides. Anticancer Drug Des. 1991;6:569–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seidman MM, Puri N, Majumdar A, Cuenoud B, Miller PS, Alam R. The development of bioactive triple helix-forming oligonucleotides. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2005;1058:119–127. doi: 10.1196/annals.1359.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalish JM, Glazer PM. Targeted genome modification via triple helix formation. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2005;1058:151–161. doi: 10.1196/annals.1359.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gamper HB, Hou YM, Stamm MR, Podyminogin MA, Meyer RB. Strand invasion of supercoiled DNA by oligonucleotides with a triplex guide sequence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:2182–2183. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan PP, Lin M, Faruqi AF, Powell J, Seidman MM, Glazer PM. Targeted correction of an episomal gene in mammalian cells by a short DNA fragment tethered to a triplex-forming oligonucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11541–11548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu CF, Phillips JW, Trauger JW, Farkas ME, Belitsky JM, Heckel A, Olenyuk BZ, Puckett JW, Wang CC, Dervan PB. Completion of a programmable DNA-binding small molecule library. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:6146–6151. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dervan PB, Doss RM, Marques MA. Programmable DNA binding oligomers for control of transcription. Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:373–387. doi: 10.2174/1568011054222346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandell JG, Barbas C.F., III Zinc Finger Tools: custom DNA-binding domains for transcription factors and nucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W516–W523. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urnov FD, Miller JC, Lee YL, Beausejour CM, Rock JM, Augustus S, Jamieson AC, Porteus MH, Gregory PD, Holmes MC. Highly efficient endogenous human gene correction using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nature. 2005;435:646–651. doi: 10.1038/nature03556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen PE, Egholm M, Berg RH, Buchardt O. Sequence-selective recognition of DNA by strand displacement with a thymine-substituted polyamide. Science. 1991;254:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1962210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherny DY, Belotserkovskii BP, Frank-Kamenetskii MD, Egholm M, Buchardt O, Berg RH, Nielsen PE. DNA unwinding upon strand-displacement binding of a thymine-substituted polyamide to double-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:1667–1670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen PE, Egholm M, Buchardt O. Evidence for (PNA)2/DNA triplex structure upon binding of PNA to dsDNA by strand displacement. J. Mol. Recognit. 1994;7:165–170. doi: 10.1002/jmr.300070303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaihatsu K, Shah RH, Zhao X, Corey DR. Extending recognition by peptide nucleic acids (PNAs): binding to duplex DNA and inhibition of transcription by tail-clamp PNA-peptide conjugates. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13996–14003. doi: 10.1021/bi035194k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bentin T, Larsen HJ, Nielsen PE. Combined triplex/duplex invasion of double-stranded DNA by "tail-clamp" peptide nucleic acid. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13987–13995. doi: 10.1021/bi0351918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapireddy S, He G, Roy S, Armitage BA, Ly DH. Strand invasion of mixed-sequence B-DNA by acridine-linked, gamma-peptide nucleic acid (gamma-PNA) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15596–15600. doi: 10.1021/ja074886j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lohse J, Dahl O, Nielsen PE. Double duplex invasion by peptide nucleic acid: a general principle for sequence-specific targeting of double-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11804–11808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demidov VV, Protozanova E, Izvolsky KI, Price C, Nielsen PE, Frank-Kamenetskii MD. Kinetics and mechanism of the DNA double helix invasion by pseudocomplementary peptide nucleic acids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5953–5958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092127999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kutyavin IV, Rhinehart RL, Lukhtanov EA, Gorn VV, Meyer R.B., Jr, Gamper H.B., Jr. Oligonucleotides containing 2-aminoadenine and 2-thiothymine act as selectively binding complementary agents. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11170–11176. doi: 10.1021/bi960626v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishizuka T, Yoshida J, Yamamoto Y, Sumaoka J, Tedeschi T, Corradini R, Sforza S, Komiyama M. Chiral introduction of positive charges to PNA for double-duplex invasion to versatile sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1464–1471. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim KH, Nielsen PE, Glazer PM. Site-directed gene mutation at mixed sequence targets by psoralen-conjugated pseudo-complementary peptide nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7604–7613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roca AI, Cox MM. RecA protein: structure, function, and role in recombinational DNA repair. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1997;56:129–223. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bianco PR, Tracy RB, Kowalczykowski SC. DNA strand exchange proteins: a biochemical and physical comparison. Front. Biosci. 1998;3:D570–D603. doi: 10.2741/a304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishinaka T, Shinohara A, Ito Y, Yokoyama S, Shibata T. Base pair switching by interconversion of sugar puckers in DNA extended by proteins of RecA-family: a model for homology search in homologous genetic recombination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:11071–11076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard-Flanders P, West SC, Stasiak A. Role of RecA protein spiral filaments in genetic recombination. Nature. 1984;309:215–219. doi: 10.1038/309215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z, Yang H, Pavletich NP. Mechanism of homologous recombination from the RecA-ssDNA/dsDNA structures. Nature. 2008;453:489–484. doi: 10.1038/nature06971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radding CM, Beattie KL, Holloman WK, Wiegand RC. Uptake of homologous single-stranded fragments by superhelical DNA. IV. Branch migration. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;116:825–839. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsieh P, Camerini-Otero CS, Camerini-Otero RD. The synapsis event in the homologous pairing of DNAs: RecA recognizes and pairs less than one helical repeat of DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:6492–6496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gamper HB, Nulf CJ, Corey DR, Kmiec EB. The synaptic complex of RecA protein participates in hybridization and inverse strand exchange reactions. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2643–2655. doi: 10.1021/bi0205202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vester B, Wengel J. LNA (locked nucleic acid): high-affinity targeting of complementary RNA and DNA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13233–13241. doi: 10.1021/bi0485732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirkpatrick DP, Rao BJ, Radding CM. RNA-DNA hybridization promoted by E. coli RecA protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4339–4346. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.16.4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaitsev EN, Kowalczykowski SC. A novel pairing process promoted by Escherichia coli RecA protein: inverse DNA and RNA strand exchange. Genes Dev. 2000;14:740–749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar RK, Davis DR. Synthesis and studies on the effect of 2-thiouridine and 4-thiouridine on sugar conformation and RNA duplex stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1272–1280. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Testa SM, Disney MD, Turner DH, Kierzek R. Thermodynamics of RNA-RNA duplexes with 2- or 4-thiouridines: implications for antisense design and targeting a group I intron. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16655–16662. doi: 10.1021/bi991187d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard FB, Miles HT. 2NH2A X T helices in the ribo- and deoxypolynucleotide series. Structural and energetic consequences of 2NH2A substitution. Biochemistry. 1984;23:6723–6732. doi: 10.1021/bi00321a068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rice KP, Chaput JC, Cox MM, Switzer C. RecA protein promotes strand exchange with DNA substrates containing isoguanine and 5-methyl isocytosine. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10177–10188. doi: 10.1021/bi0003339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain SK, Inman RB, Cox MM. Putative three-stranded DNA pairing intermediate in recA protein- mediated DNA strand exchange: no role for guanine N-7. J Biol. Chem. 1992;267:4215–4222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta RC, Folta-Stogniew E, O'Malley S, Takahashi M, Radding CM. Rapid exchange of A:T base pairs is essential for recognition of DNA homology by human Rad51 recombination protein. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:705–714. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malkov VA, Sastry L, Camerini-Otero RD. RecA protein assisted selection reveals a low fidelity of recognition of homology in a duplex DNA by an oligonucleotide. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;271:168–177. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malkov VA, Camerini-Otero RD. Dissociation kinetics of RecA protein-three-stranded DNA complexes reveals a low fidelity of RecA-assisted recognition of homology. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;278:317–330. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gamper HB, Parekh H, Rice MC, Bruner M, Youkey H, Kmiec EB. The DNA strand of chimeric RNA/DNA oligonucleotides can direct gene repair/conversion activity in mammalian and plant cell-free extracts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4332–4339. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Igoucheva O, Alexeev V, Yoon K. Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis and targeted gene correction: a mechanistic point of view. Curr. Mol. Med. 2004;4:445–463. doi: 10.2174/1566524043360465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drury MD, Kmiec EB. DNA pairing is an important step in the process of targeted nucleotide exchange. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:899–910. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Igoucheva O, Alexeev V, Yoon K. Mechanism of gene repair open for discussion. Oligonucleotides. 2004;14:311–321. doi: 10.1089/oli.2004.14.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janowski BA, Kaihatsu K, Huffman KE, Schwartz JC, Ram R, Hardy D, Mendelson CR, Corey DR. Inhibiting transcription of chromosomal DNA with antigene peptide nucleic acids. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:210–215. doi: 10.1038/nchembio724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DasGupta C, Cunningham RP, Shibata T, Radding CM. Enzymatic cleavage of D loops. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1979;43(Pt 2):987–990. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1979.043.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Majumdar A, Muniandy PA, Liu J, Liu JL, Liu ST, Cuenoud B, Seidman MM. Targeted gene knock in and sequence modulation mediated by a psoralen-linked triplex-forming oligonucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:11244–11252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800607200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gamper HB, Hou YM, Kmiec EB. Evidence for a four-strand exchange catalyzed by the RecA protein. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15272–15281. doi: 10.1021/bi001704o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lahoud G, Timoshchuk V, Lebedev A, de Vega M, Salas M, Arar K, Hou YM, Gamper H. Enzymatic synthesis of structure-free DNA with pseudo-complementary properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3409–3419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gamper HB, Jr, Arar K, Gewirtz A, Hou YM. Unrestricted accessibility of short oligonucleotides to RNA. RNA. 2005;11:1441–1447. doi: 10.1261/rna.2670705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]