Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to describe community consultation and communication efforts for the Personalized Medicine Research Project (PMRP), a population-based biobank. A series of focus group discussions was held in the year preceding initial recruitment efforts with potentially eligible community residents and slightly less than a year after initial recruitment with eligible residents who had declined participation in PMRP. A Community Advisory Group, with 19 members reflecting the demographics of the eligible community, was formed and meets twice yearly to provide advice and feedback to the PMRP Principal Investigator and the local IRB. Ongoing communication with study subjects, who consent on the condition that personal genetic results will not be disclosed, takes place through a newsletter that is distributed twice yearly, community talks and media coverage. Most focus group participants were concerned about the confidentiality of both their medical and genetic data. Focus group discussions with eligible residents who elected not to participate in PMRP revealed that many knew very little about the project, but thought that too much information had been provided, leading them to believe that it would take too long for them to understand and enroll in the study. In conclusion, an engaged community advisory group can provide a sounding board to study investigators for many study issues and can provide guidance for broader communication activities. Researchers need to balance the provision of information for potential subjects to make informed decisions about study participation, with respect for individuals’ time to read and interpret study materials.

Keywords: Genetics, consumer participation, ethics consultation

INTRODUCTION

With the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003, Dr. Francis Collins, Director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, and colleagues presented a vision for the future of genomics research [Collins et al., 2003]. One of the grand challenges highlighted was to “assess how to define the ethical boundaries for uses of genomics”, including having “conversations between diverse parties” to “promote the formulation and implementation of effective policies”. A review of the medical literature related to ethical, legal and social issues (ELSI) in developing population genetic databases described the need for public engagement in the recruitment and education of participants [Austin et al., 2003]. A report from the First Community Consultation on the Responsible Collection and Use of Samples for Genetics Research, held in 2000, included 10 recommendations, including the need to obtain broad community input for all phases of research and ensuring dissemination of accurate information to the media and public (http://www.nigms.nih.gov/news/reports/community_consultation.html). A community engagement process about genetic research in Canada revealed that concern about confidentiality of the data would influence individuals’ decisions to participate and that targeted communication is necessary [Godard et al., 2007]. Community engagement for the International HapMap Project in four different populations also revealed concerns about privacy and confidentiality [Rotimi et al., 2007]. These researchers reported that it was challenging to incorporate community input into their research plans.

After more than a year of planning and community consultation, the Marshfield Clinic Personalized Medicine Research Project (PMRP) began recruitment in 2002. The ultimate goal of the PMRP is to translate genetic data into specific knowledge about disease that is clinically relevant and will enhance patient care [McCarty et al., 2005]. The short-term goal is to establish a database to allow research in genetic epidemiology, pharmacogenetics and population genetics. Designed in three phases, the first phase included the community engagement and consultation efforts prior to, and throughout, recruitment and enrollment. The purpose of this paper is to describe those efforts.

METHODS

Focus Group Discussions

IRB staff members at the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation were consulted about the focus group discussions. Because no identifiers were maintained, it was determined that that the data did not meet the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation definition for human subjects research and therefore no further review or approvals were conducted. Four series of focus groups were held. Names and addresses of potential adult (aged 18 years and older) focus group participants for the first three series of focus groups were provided to an external marketing firm who then called potential participants until all groups were filled. For the final series of focus groups, postcards were mailed to potential participants and interested residents were asked to return the postcards to the external marketing firm who then set up the discussions. Names of participants were not recorded or supplied to the Marshfield Clinic. All discussions were taped and summaries were prepared. The groups met at a neutral site, outside the Marshfield Clinic, and subjects were offered $75 for their participation.

The topics discussed in the four series of focus groups are summarized in Table I. Held 16 months before recruitment commenced, the first series of focus groups included four groups. Their overall purpose was to begin the process of consulting with the population, gain information and reactions to the PMRP, and test informational materials to be used in recruitment. Held 11 months before initial recruitment, the second set of focus groups again included four groups, with the same purpose as the first set, but with Marshfield Clinic employees. The third set of focus groups was held three months before the launch of the project and included two groups with the purpose of gathering feedback on written documents developed to explain the project to potential subjects. The final set of four focus groups was held 11 and 12 months after the launch of recruitment to gather information from eligible residents who elected not to participate by reason that they were “not interested” in order to learn how the enrollment process might be improved to increase the participation rate.

Table I.

Focus Group topics

| Focus Group Series | Topics Addressed |

|---|---|

| 1: Non-Marshfield Clinic employees | How people in the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area (MESA) view medical and genetic research |

| How likely people in MESA would be to participate in the Personalized Medicine Research Program | |

| How people feel about researchers studying their genes and their personal medical record | |

| Whether residents of MESA trust the Marshfield Clinic | |

| How well they understand the “personalized medicine” concept | |

| What would motivate their family, friends and neighbors to volunteer | |

|

| |

| 2: Marshfield Clinic employees | What Marshfield Clinic staff think about the Marshfield Medical Research Foundation |

| Awareness of the PMRP | |

| Interpretations of the name “Personalized Medicine Research project” and the term “personalized medicine” | |

| Opinions about genetic research and studying human genes to discover new information about health | |

| How staff feel about researchers using information from patients’ medical records to discover new medical information about health | |

| Whether/why staff would/would not participate in PMRP | |

| Reactions to proposed Privacy and Security in Genetic Research policy | |

| Communication about PMRP to Clinic staff | |

| How participation in PMRP can be convenient and easy for Clinic staff | |

| Factors that will influence employee participation the most | |

|

| |

| 3: Potential PMRP subjects | Whether people would open mailing #1 when they received it |

| Whether people would read the contents of mailing #1 | |

| Whether the contents of mailed #1 were clear and understandable an how it could be improved | |

| Whether the brochure in mailing #1 is clear and understandable and how it could be improved | |

| Whether mailing #2 was effective | |

| Whether the letter in mailing #2 was clear and understandable and how it could be improved | |

| Whether the consent form was clear and understandable and how it could be improved | |

| Whether the FAQs answered readers’ questions | |

| Whether the questionnaire was clear and understandable and how it could be improved | |

|

| |

| 4. Residents who refused PMRP participation by reason of “not interested” | Attitudes towards the Marshfield Clinic |

| Perceptions of the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation | |

| Awareness and knowledge of the Personalized Medicine Research Project | |

| Reasons why some patients/staff chose not to participate in PMRP | |

| What could have been done differently to interest more people in PMRP | |

| Response to one-page flyer for PMRP | |

| Outlook on the benefits of genetic research in the future | |

Community Advisory Group

A Community Advisory Group was formed to provide guidance, from the community perspective, on the development, implementation and on-going operations of PMRP. The plan was to invite 15 community members from various demographic groups within the recruitment area and representation from sub-groups such as economic (business, industry, agriculture, employers, workers), education, health, clergy, media, public officials, previous study participants and civic organizations. The initial length of membership was planned to be 18 months, with monthly meetings in the first six months, decreasing to meetings every two months. Members were compensated for their travel, and provided with a meal and a stipend of $100.

Community Communication

The overall goal of this component of the consultation and communication plan was to educate residents of the 19 Zip code region about the PMRP through talks to community groups and media prior to enrollment, and then through regular newsletters after study participation. Local service organizations were provided with the name of a speaker(s) from the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation to talk about PMRP at their meetings. Local and national media releases were prepared at the launch of enrollment. Local media releases were prepared at the time that the 1000th, 5000th, 10,000th and 15,000th subjects were enrolled. Media releases were also developed to announce the start of Alzheimer disease and glaucoma pharmacogenetics studies. A 14-minute video was professionally produced to be played on television monitors throughout the Marshfield Clinic and to be used in talks to community groups.

A full-color, letter-sized information sheet highlighting the main points of PMRP was developed with input from the Community Advisory Group. This sheet was included as an insert in the Marshfield News Herald three times during the active recruitment phase and displayed throughout the Marshfield Clinic. It was also included in the initial recruitment letters to eligible residents. A full-color, 10-page brochure and a 4-page, 81/2×11-sized frequently asked questions was developed to be included with the initial letter of invitation to eligible residents and as handouts at community talks and for distribution throughout the Marshfield Clinic.

PMRP subjects provide written informed consent to participate in PMRP on the condition of non-disclosure of personal genetic results. Instead, they were offered the opportunity in the written informed consent document to indicate if they did not want to receive a PMRP newsletter that would contain information about current studies using the database.

All print materials and summaries of current research projects using the database are posted on the PMRP website (www.mfldclin.edu/pmrp).

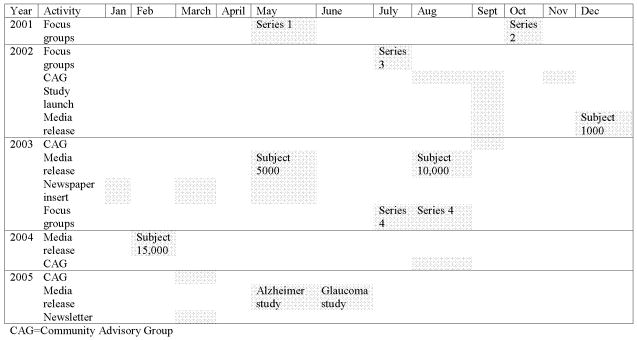

Timing of all communication activities is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of community consultation and communication activities in relation to Phase I PMRP recruitment.

RESULTS

As of January 20, 2008, 19,723 adults had enrolled in PMRP; this represents a 45% response rate. The most common reason cited for refusal to participate was “not interested” (71%), followed by “inconvenience” (18%), fear of blood draw (3%), “privacy” (2%), and “oppose genetic testing” (1%). As of December 31, 2007, 577 subjects had died.

Three people have asked to withdraw from the study and their DNA, plasma and serum samples have been removed from the biobank. One was a 92-year-old woman who asked to be removed from the study one week after her initial enrollment. One man age 36 with a history of mental health issues asked to be removed from PMRP and all other Clinic studies 14 months after enrollment into PMRP. A man age 27 enrolled, but was unable to provide a blood sample because he fainted. One month later, he declined a further attempt at a blood draw and asked to be removed from the study.

Focus Group Discussions

In the four series of 14 focus groups during the planning, consultation and active recruitment Phase I of PMRP, investigators found several overarching issues. First, focus group participants trust the Marshfield Clinic, their health care provider, and that is why they might choose to participate in a genetics study. Second, the issue of human cloning was brought up by participants when they were asked about their opinions of genetic research. They wanted to ensure that no human cloning research would be done and that if DNA samples were to be transferred to investigators at another institution that those researchers would follow the same strict procedures to ensure confidentiality that were set up by the Marshfield Clinic. Third, many people expressed concern about the potential for insurance discrimination, hence the expressed concern about the confidentiality and security of their data. All of these concerns were taken into account in the design of written materials and in the conduct of the study. Specific results from each of the four series of focus groups follow.

Series 1: Non-Marshfield Clinic employees

Four focus groups were held with a total of 33 participants, 17 males and 16 females. When queried about their perceptions of genetic research, a majority of the subjects felt that genetic research has tremendous potential to improve health care for their families, with heart disease and cancer mentioned most often. However, some participants also associate genetic research with cloning and genetic engineering which arouses fear and uncertainty. Their primary sources of information about genetic research are the mass media, especially television. Twenty-seven of the 33 focus group members said that they would be interested in participating in PMRP, but that their participation was conditional upon assurance that the confidentiality of their medical record and genetic data would be satisfactorily protected and that the research would not involve cloning. The major difference between people who indicted that they would participate and those who would not was their trust in the Marshfield Clinic and Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation. Suggested media components to attract participants to PMRP included local TV, radio, newspapers, direct contact through the mail and telephone, information at Marshfield Clinic sites, brochure, video and web site. Three of the four groups suggested a monetary incentive to attract higher participation rates. In addition to monetary compensation, other suggested incentives included free testing (such as cholesterol testing), dinner for four at McDonalds, or a prescription rebate. All groups suggested that the enrollment process be made very easy by coordinating the blood draw with existing Clinic appointments, making the entire enrollment process 30 minutes or less, offering evening appointments and appointments at other Marshfield Clinic sites, and keeping the paperwork to a minimum.

As a result of the responses to these focus group discussions, a number of suggestions were incorporated into the communications plan. In the video and Frequently Asked Questions brochure, we highlighted the fact that human cloning was not part of the research. Researchers decided to limit the length of questionnaires at the time of enrolment so that the entire process would last no longer than 30 minutes. A $20 gift voucher that could be used at any business in Marshfield or exchanged for cash at local banks was provided to cover any costs related to participation and at least one weekly evening appointment time was offered. Appointment times at the regional centers were organized once per month, usually on a weekend. Another response to this focus group series was the decision to apply for a Certificate of Confidentiality through the National Human Genome Research Institute. A Certificate of Confidentiality was granted on August 1, 2002 and renewed for 10 years in August 2007.

Series 2: Marshfield Clinic employees

Four focus groups with Marshfield Clinic employees were held, one in the central region and one in the north. They comprised 46 subjects in total, 10 males and 36 females. Thirty-three of the 46 staff said that they would be interested in participating in PMRP. Eight of the subjects said ‘maybe’ to participation and five said ‘no’. The primary reasons for their reluctance to participate were concerns about privacy of personal health information and not understanding PMRP. Suggestions to improve participation by employees centered around trust in security and Clinic privacy policies about appropriate use of personal medical information, communication and convenience. Specific suggestions for ease in enrollment included sessions during scheduled work hours so that employees did not have to take time off work to enroll, making the enrollment process take no longer than 30 minutes, and allowing enrollment at the sites where employees work. The employees suggested communication about the project to Clinic staff prior to the communication to the general population so that they could answer questions from the public.

A draft policy on privacy and security in genetic research was presented to the Clinic employees for their feedback. Two items generated some questions and concern. In considering the issue of disclosure of “serious or life threatening” problems, most people agreed that they would want to have a choice about disclosure, although some did not expect any information to be disclosed. The item about the Clinic not selling, giving or permanently transferring DNA samples to outside researchers raised discussion about how the policy would be enforced and what would happen if the Marshfield Clinic was ever to be sold.

As a result of the feedback from the employee focus groups, presentations about PMRP were held for Clinic and hospital staff prior to open enrollment and the wider community communication campaign, and articles about the project published in the weekly employee newsletter. Enrolment during paid work time was not allowed for ethical and legal reasons and the appearance of coercion. In fact, all letters and phone calls to discuss recruitment into PMRP were conducted with individuals based on their residence in one of the 19 Zip codes, NOT as Clinic employees. A Privacy and Security in Genetic Research policy was published effective July 30, 2002 and all Material Transfer Agreements to use PMRP DNA refer to this policy.

Series 3: Potential PMRP participants

This series of two focus groups with potentially eligible PMRP subjects included 9 males and 12 females. After reviewing draft materials for two mailings, the majority of focus group participants said that they would open mailing #1 consisting of a letter and brochure and most agreed that was enough information for them to make a decision about participation. After reading the draft materials for mailing #2, which consisted of a cover letter, consent form, Frequently Asked Questions and study questionnaire, both groups agreed that there was “way too much to read” and that the consent form and questionnaire should only be sent to people after they indicated interest in the study. After reading all of the draft materials, participants were still unclear about three issues: the magnitude of the confidentiality risks, why they can’t get personal health information as a result of their participation, and what is involved in participation. Suggestions to improve the mailings included noting the $20 in the first letter, making the information concise and consistent, adding specific information on the what, where and how of participation, adding photos to the brochures, and contacting people within 1–2 weeks after the mailing. In reviewing the draft questionnaire, several people asked about the relevance to medical research of the question on highest level of formal education attained. In terms of the consent form, the use of the word “tissue” confused people and they wondered if something other than blood was being taken. They were also unclear about how many times they would be asked to give blood since the consent form indicated that the study would go on for as long as 20 years. The risk section about the potential for breach of confidentiality also raised concerns with many focus group participants.

In response to the knowledge gained in these focus group discussions, a number of changes were made. Only one initial recruitment letter was sent to potential subjects. This letter included mention of the $20 and the brochure and Frequently Asked Questions, but not the consent form and questionnaire; the latter were mailed to people with an appointment reminder after they had agreed to participate. The question related to highest education level attained was removed from the questionnaire. The consent form was revised to consistently use the word “blood” instead of “tissue”. The sentence about the length of the study was clarified to state that length of time was necessary to follow the health of the population over time.

Series 4: “Not interested” residents who refused PMRP participation

These four focus groups represented two small communities within 20 miles of Marshfield, two groups from Marshfield, one from the general community and one comprising Marshfield Clinic employees. The four groups were similar in age distribution, although there were no Clinic employees over the age of 69. There were 21 males and 23 females in the groups.

Most people who declined to participate in PMRP found the study hard to understand and the majority of people had little awareness of PMRP. About half of the patient participants said that they might have considered participation if it took less time to learn about the project and/or enroll and about half said that they were just not interested in taking the time to learn about the project or to participate. One of the reasons that some participants in the Marshfield Clinic employee group cited as the reasons that they declined participation was a fear of loss of confidentiality of their personal health and subsequent employment and/or health insurance discrimination. All groups felt that the written information about PMRP could be made more concise and clear. Patient groups in the two outer communities suggested setting up enrollment locations in their local communities. Many suggested offering more than $20 as an incentive to participate. Many also indicated that they now wanted to participate in PMRP after hearing more about the project through the focus group discussions. Because no names were retained, they could not be contacted by PMRP staff to enroll and would have had to contact PMRP staff directly to participate after their initial refusal.

In response to these focus group comments, a full-color, one-page information flyer was created with bullet points to highlight the key study points. This flyer replaced the previous 10-page brochure and Frequently Asked Questions used in the initial mailing to eligible residents. In addition, the most current newsletter is included at the time of initial contact with eligible residents. A local enrollment site was set up on a weekend in the community furthest from Marshfield, with support from one of the Community Advisory Group members to identify a location and advertise the study through the local weekly newspaper. The $20 offered to study participants was not changed, in part because the Marshfield Clinic IRB provides guidance to investigators that subjects should be offered about $20 per hour of time to participate in a study, so the $20 for PMRP participation would be inline with this guidance and other Marshfield Clinic studies.

Community Advisory Group (CAG)

Community Advisory Group (CAG) members reside in six of the 19 eligible PMRP Zip codes. They have met twice yearly since 2001, the initial year of PMRP recruitment. Agendas are set by the Principal Investigator, with requests and feedback from board members about agenda items for subsequent meetings. One person resigned from the board after three years because of regular conflicts with meeting times. The initial 18 month letters of agreement and confidentiality agreements have been extended on an annual basis, though we are now in the process of considering term limits. The CAG is advisory in nature. The Chair of the Marshfield IRB is invited to attend the meetings to facilitate communication between the two boards.

At the initial meeting of the CAG, genetic terms were defined, progress on the project to date was reviewed, the project timeline was reviewed, and the role of the advisory group was discussed. At the second meeting, the CAG reviewed the video to be used within the community and they provided feedback. They also provided suggestions for community groups to speak with. At the third and fourth meetings, they reviewed the information obtained from the focus group discussions and provided further feedback on the recruitment materials and ideas for the one-page full-color information sheet to be developed for use in recruitment. Subsequent meetings about recruitment and community consultation efforts included discussions about recruitment of nursing home residents, topics for the PMRP newsletters, and additional community groups to contact. When queried about how often it would be reasonable to approach subjects who consented to recontact, the group felt that as long as a monetary incentive was offered for each subsequent study, several contacts per year would be fine. In a discussion about current projects using the PMRP database, the group was very pleased that Marshfield scientists were conducting research on Fibromyalgia syndrome, a disease that they perceive is not taken seriously by many physicians.

In October 2006, the CAG discussed the Request for Information regarding the Proposed Policy for Sharing of Data obtained in NIH supported or conducted Genome-Wide Association Studies (NOT-OD-06-094). Subsequently, a response on behalf of the group was submitted. In general, the CAG supported the idea of sharing data to further science, but wanted to ensure that the Certificate of Confidentiality would continue to be honored. They raised some concerns about the government’s ability to adequately secure the data. Another concern of the CAG was that a defined set of phenotypic data be shared centrally, not a person’s entire medical record. A discussion about the sharing of data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that was started at the August 2007 meeting will be revisited in future meetings. The Marshfield Clinic IRB is developing a policy related to disclosure of unanticipated findings in research. This has implications for the non-disclosure of genetic results as defined in the current PMRP written informed consent document.

An initial discussion about possible collaborations between Marshfield Clinic researchers and industry generated strong opinions, ranging from “we just want to see good science being done with PMRP” and “as long as they don’t tell you what to do” to “how could you possibly work with drug companies?”

Community Communication

In the 18 months of Phase I of PMRP, media coverage of PMRP included live radio interviews on three different local radio stations, coverage of the official launch of the project on Eau Claire television, and 12 print interviews, including the Marshfield News Herald, Wausau Daily Herald, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Chicago Tribune, Science, Business Week magazine, New York Times, Forbes magazine and others. Talks to community organizations, timed for the recruitment periods in each of the 19 Zip codes, resulted in an estimated 1000 potentially eligible subjects hearing about PMRP in person. Individual meetings with local clergy were also held. The video developed for PMRP was rarely used at community talks due to difficulty in organizing rooms with the correct lighting, seating and electrical outlets to support the display of the video.

The first PMRP newsletter was developed and mailed to study participants and other interested parties approximately 16 months after the end of Phase I. Along with the newsletter, study subjects received a letter to remind them of their study participation, why they had received the PMRP newsletter, and a reminder to contact study personnel if they wished to not receive future newsletters. This newsletter highlighted recruitment and an Alzheimer disease research study underway. The second newsletter, which was printed and distributed 12 months after the first newsletter, highlighted a pharmacogenetics study of cholesterol-lowering medications and a genetic epidemiology study of osteoporosis. The third newsletter, which started the 6-month mailing frequency, featured a fibromyalgia study and highlighted a publication reporting key study points in the informed consent document that were not recalled correctly by a large percent of people [McCarty et al., 2007]. In another newsletter, a breast cancer pharmacogenetics study was described and news of the NHGRI-funded genome-wide association study was announced. All newsletters have been full-color, four-sided, 81/2×11 size and are folded with a mailing label on the outside of the newsletter. Labels are addressed to the household to protect the confidentiality of study subjects and to prevent multiple copies being sent to the same household. Once per year, forwarding addresses are requested through the U.S. Postal Service to update the mailing records. Because the newsletter highlights ongoing recruitment, the text is always reviewed and approved by the IRB prior to distribution.

DISCUSSION

The communication and consultation plans of the PMRP investigators meet the recommendation of the report from the First Community Consultation on the Responsible Collection and Use of Samples for Genetics Research to obtain broad community input for all phases of research and ensuring dissemination of accurate information to the media and public (http://www.nigms.nih.gov/news/reports/community_consultation.html). The comprehensive plan requires commitment and ongoing attention. Because there have been few population-based biobanks, data for comparison are limited.

A review of the literature about public willingness to participate in genetic variation research found that Caucasians are more willing to participate in this type of research [Sterling et al., 2006]. Reflective of the demographics of central Wisconsin, the PMRP study cohort is 98% Caucasian. Common themes across the studies in the review included genetic discrimination, confidentiality or misuse of information, and a lack of interest and no perceived benefit from participation. The same concerns were expressed by PMRP focus group participants and were taken into account when considering issues about data storage and access.

Another issue raised in focus group discussions was the possibility of offering a higher level of monetary incentive to increase the participation rate. In a 10% sample survey of the first 16,000 PMRP subjects, we discovered that more than one-third of the subjects felt that the $20 offered to cover their expenses greatly influenced their decision to participate [McCarty et al., 2007]. There is a large body of literature on the ethics of providing a monetary payment for research participation. Models of payment to research subjects include market principles, wage payment, reimbursement of direct expenses and honoraria as tokens of appreciation [Dickert et al., 1999; Grady, 2005; Emanuel, 2005; Fost, 2005]. PMRP investigators elected to keep the payment at $20 to cover costs such as gasoline or time lost to work, so that study participation would be cost neutral and in line with Marshfield Clinic IRB recommendations of $20 per hour of study participation. Therefore, the payment amount was not increased as a result of focus group suggestions. Anecdotally, fewer people over time (from an original high of 10%) are electing to return the $20 for future research, perhaps because the cost to participate in terms of gasoline has increased over that same time frame.

In summary, community engagement is an ongoing process for a population-based biobank, from the planning stages, through to the dissemination of research results. An engaged community advisory group can provide a sounding board to study investigators for many study issues and an entrée into their communities for broader communication activities. Researchers need to balance the provision of information for potential subjects to make informed decisions about study participation with respect for individuals’ time to read and interpret study materials.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded in part by grant number 1 D1A RH00025-01 from the Office of Rural Health Policy, Health Resources and Services Administration and grant number U01HG004608-01 from the National Human Genome Research Institute.

The authors recognize Dr. David Schowalter, in memoriam, and Kathy Farnsworth, former Director of Government Relations at the Marshfield Clinic, for their roles in the development of the communication plans for PMRP.

The focus group discussions were led and interpreted by ©Market Square Communications Incorporated, Stevens Point, Wisconsin.

Members of the Community Advisory Group include: Tom Berger (in memorium), Phil Boehning, Sharon Bredl, Margaret Brubaker, Margy Frey, Jodie Gardner, Phil Hein, Nancy Kaster, Colleen Kelly, Mike Kobs, Norm Kommer, Darlene Krake, Mark Krueger, Julie Levelius, Jerry Minor, Mike Paul, Representative Marlin Schneider, Scott Schultz, and Jean Schwanebeck.

References

- Austin MA, Harding SE, McElroy CE. Monitoring ethical, legal, and social issues in developing population genetic databases. Genet Med. 2003;5:451–457. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000093976.08649.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins FS, Green ED, Guttmacher AE, Guyer MS US National Human Genome Research Institute. A vision for the future of genomics research. Nature. 2003;422:835–847. doi: 10.1038/nature01626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickert N, Grady C. What’s the price of a research subject? Approaches to payment for research participation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:198–203. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ. Undue inducement: nonsense on stilts? Am J Bioeth. 2005;5:9–13. doi: 10.1080/15265160500244959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fost N. Gather ye shibboleths while ye may. Am J Bioeth. 2005;5:14–15. doi: 10.1080/15265160500244983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godard B, Marshall J, Laberge C. Community engagement in genetic research: results of the first public consultation for the Quebec CARTaGENE project. Community Genet. 2007;10:147–158. doi: 10.1159/000101756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady C. Payment of clinical research subjects. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1681–1687. doi: 10.1172/JCI25694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Nair A, Austin DM, Giampietro PF. Informed consent and subject motivation to participate in a large, population-based genomics study: the Marshfield Clinic Personalized Medicine Research Project. Community Genet. 2007;10:2–9. doi: 10.1159/000096274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Wilke RA, Giampietro PF, Wesbrook SD, Caldwell MD. Marshfield Clinic Personalized Medicine Research Project (PMRP): design, methods and recruitment for a large population-based biobank. Personalized Med. 2005;2:49–79. doi: 10.1517/17410541.2.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotimi C, Leppert M, Matsuda I, Zeng C, Zhang H, Adebamowo C, Ajayi I, Aniagwu T, Dixon M, Fukushima Y, Macer D, Marshall P, Nkwodimmah C, Peiffer A, Royal C, Suda E, Zhao H, Wang VO, McEwen J International HapMap Consortium. Community engagement and informed consent in the International HapMap project. Community Genet. 2007;10:186–198. doi: 10.1159/000101761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling R, Henderson GE, Corbie-Smith G. Public willingness to participate in and public opinions about genetic variation research: a review of the literature. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1971–1978. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]