Abstract

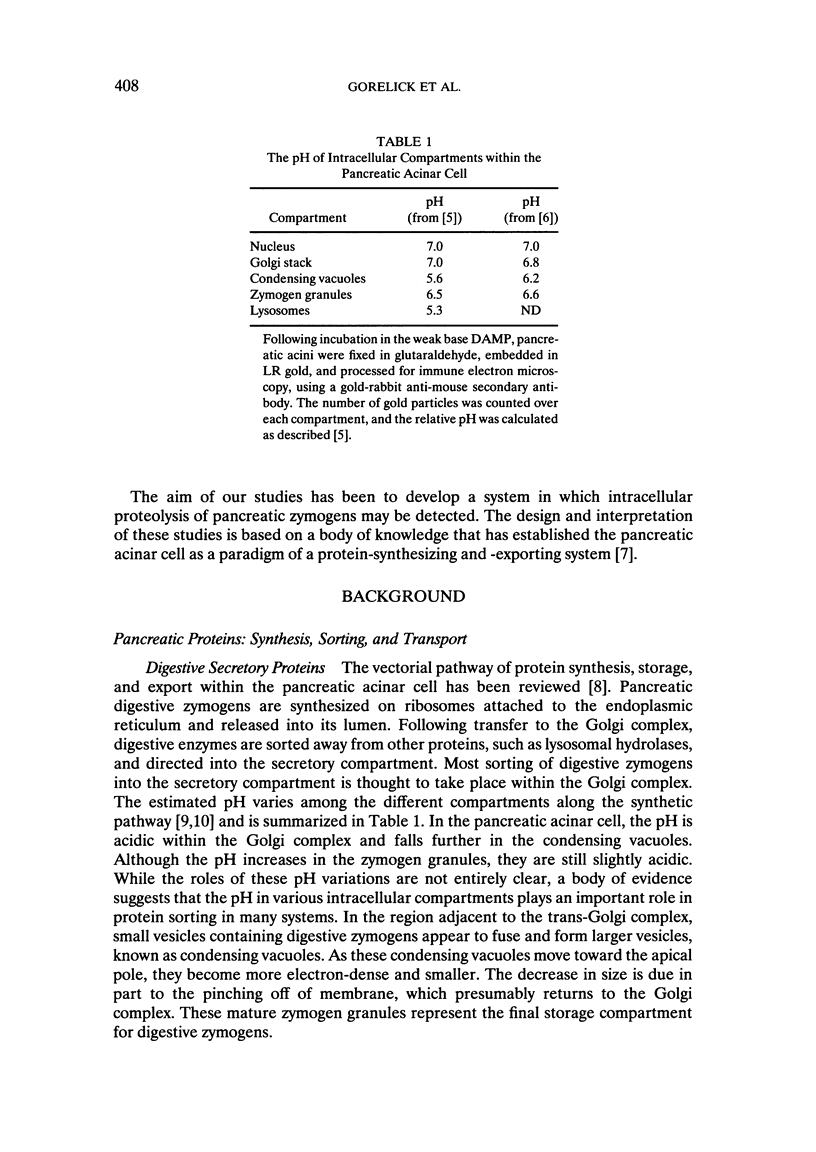

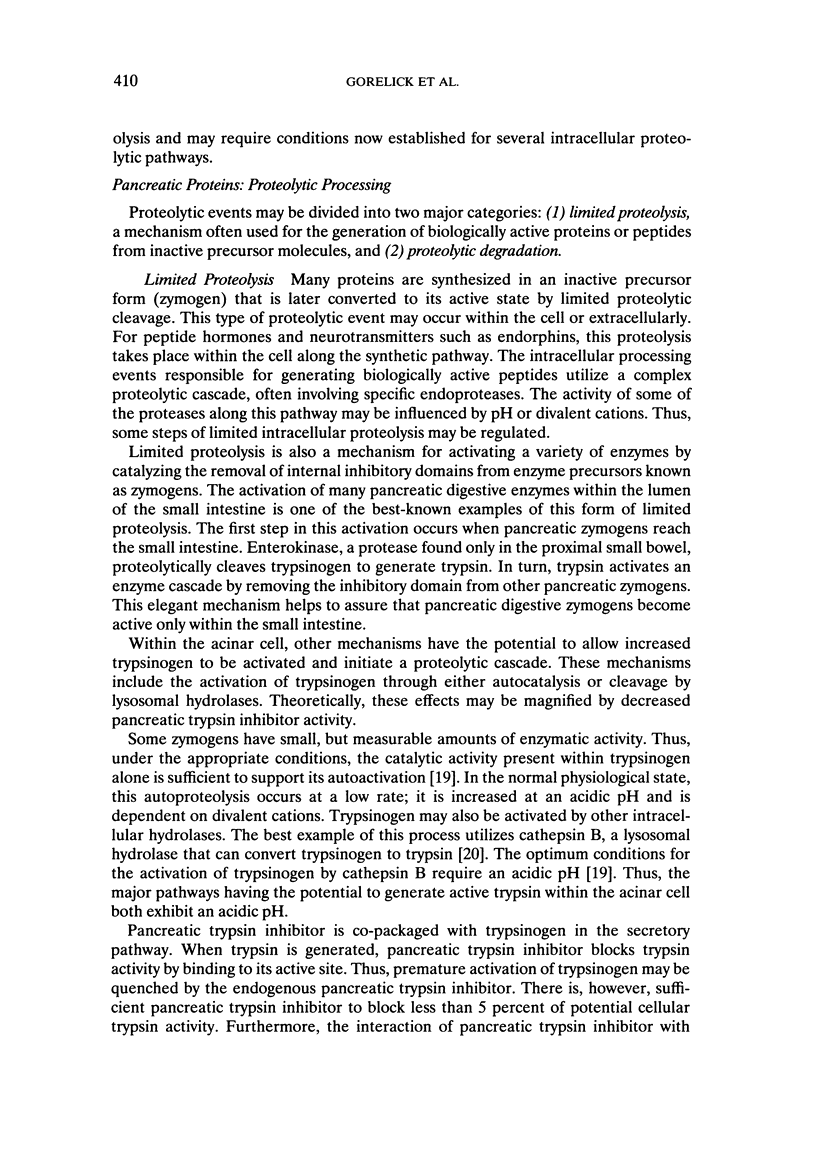

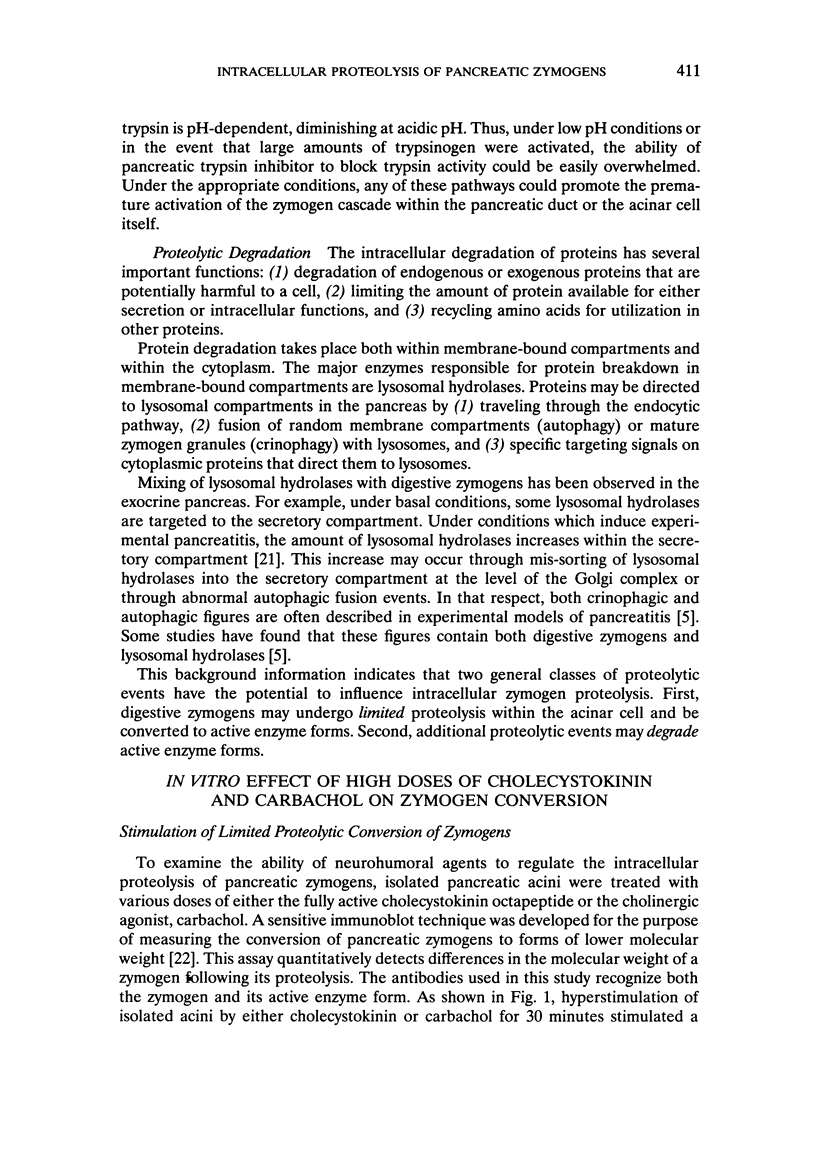

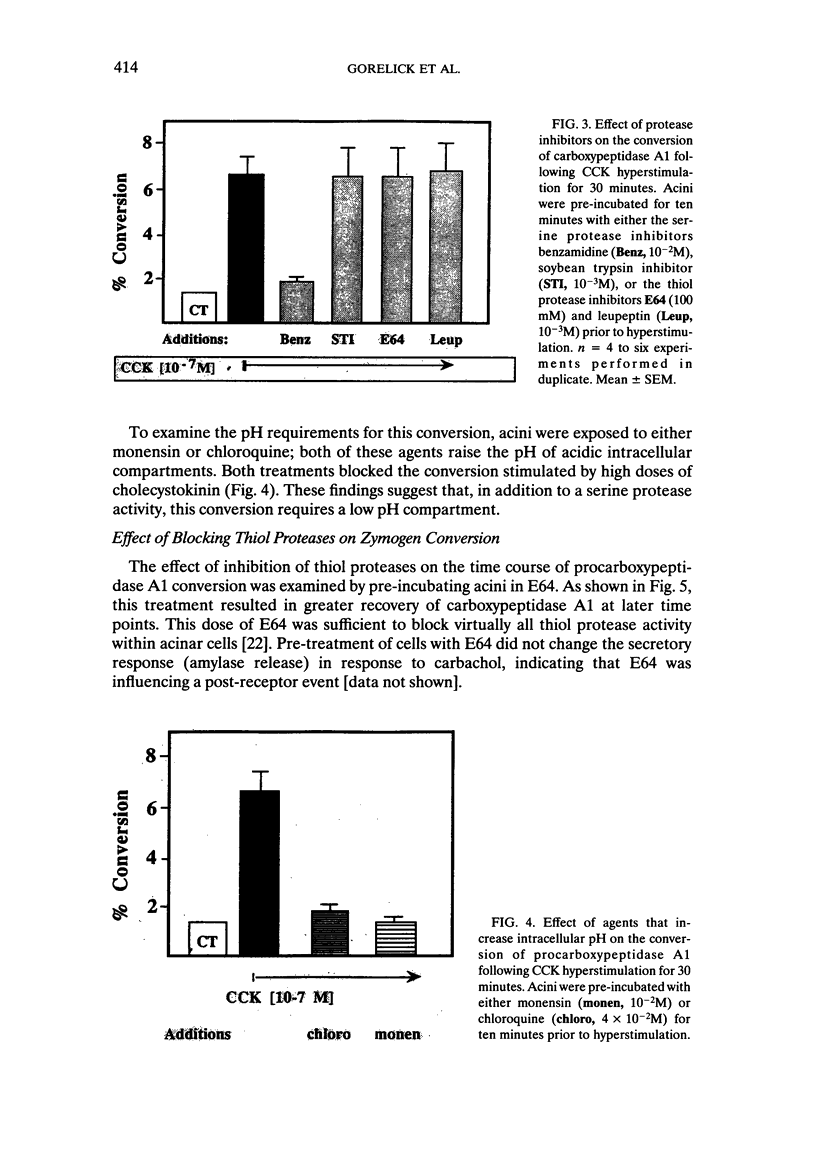

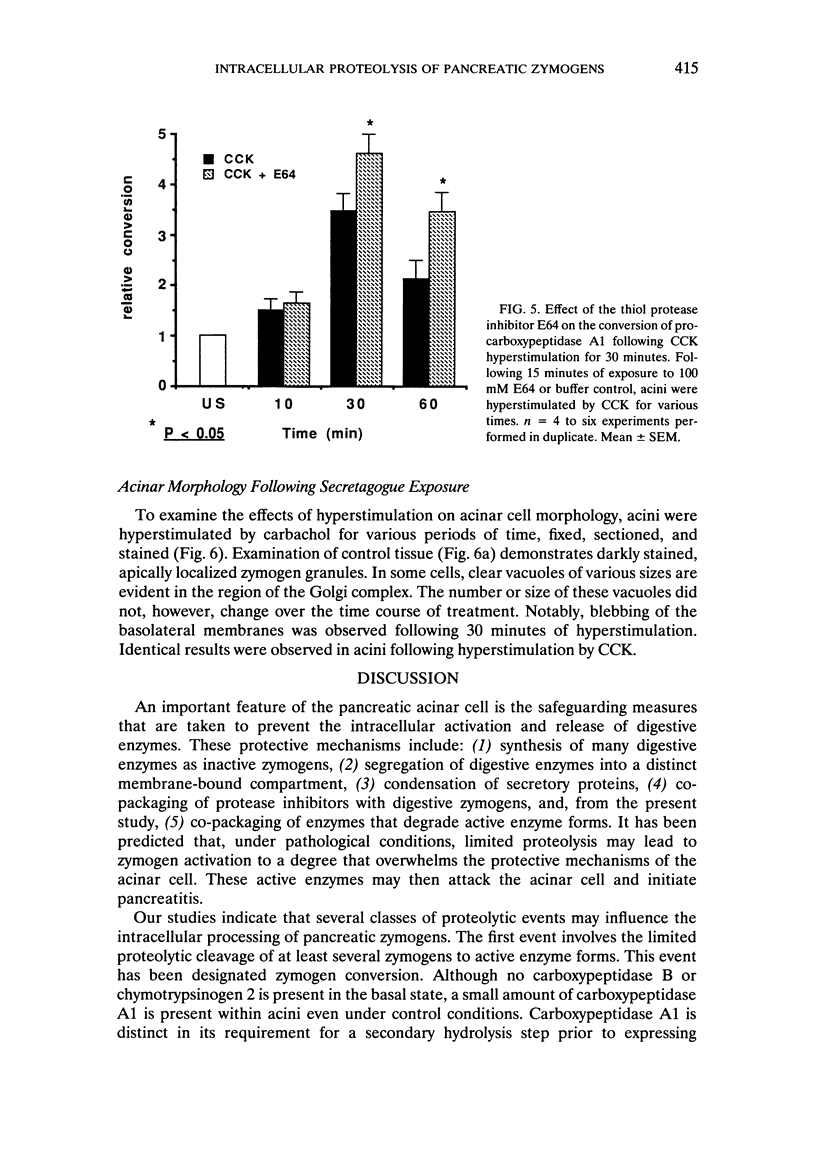

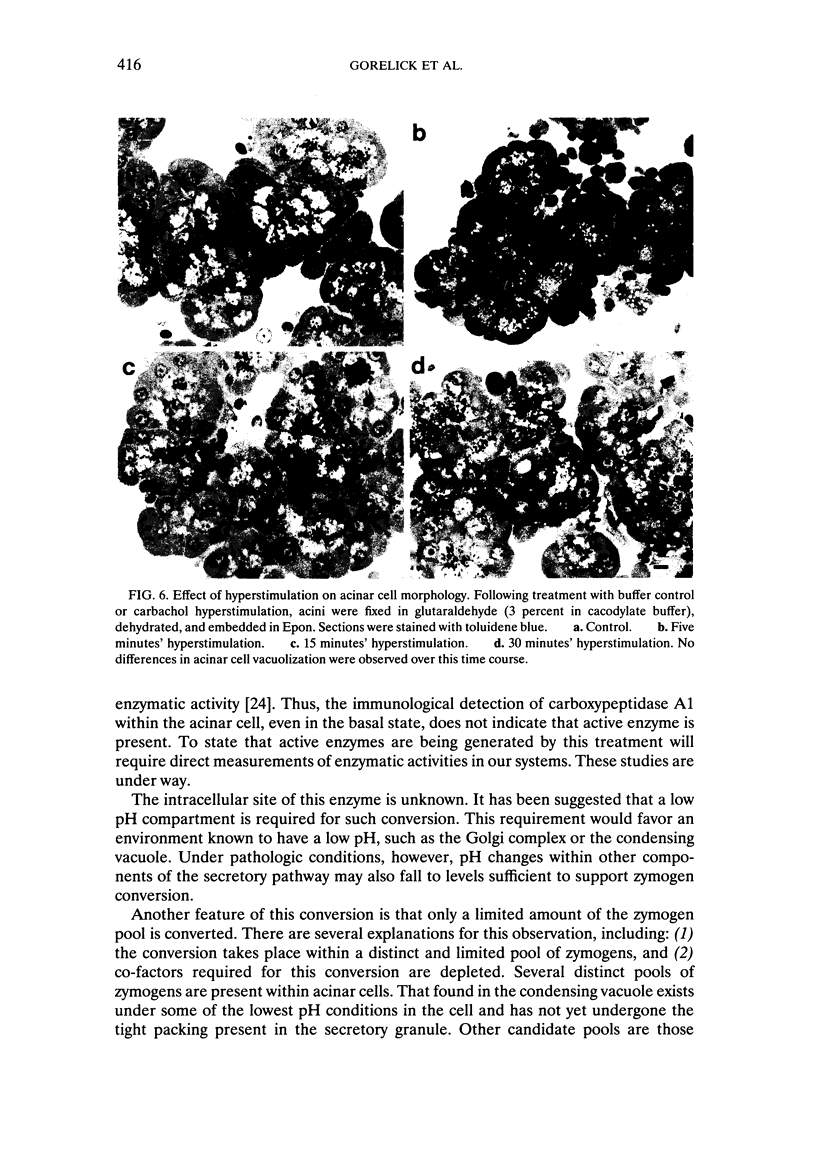

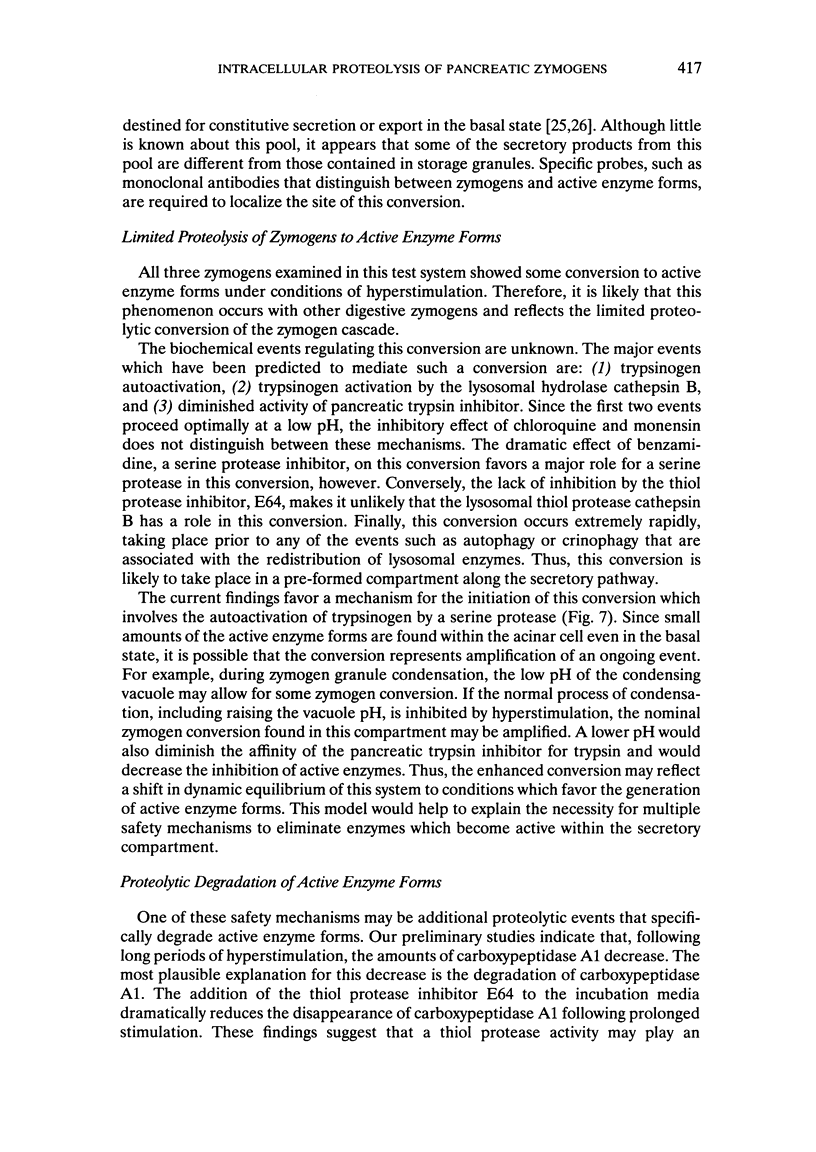

Activation of pancreatic digestive zymogens within the pancreatic acinar cell may be an early event in the development of pancreatitis. To detect such activation, an immunoblot assay has been developed that measures the relative amounts of inactive zymogens and their respective active enzyme forms. Using this assay, high doses of cholecystokinin or carbachol were found to stimulate the intracellular conversion of at least three zymogens (procarboxypeptidase A1, procarboxypeptidase B, and chymotrypsinogen 2) to their active forms. Thus, this conversion may be a generalized phenomenon of pancreatic zymogens. The conversion is detected within ten minutes of treatment and is not associated with changes in acinar cell morphology; it has been predicted that the lysosomal thiol protease, cathepsin B, may initiate this conversion. Small amounts of cathepsin B are found in the secretory pathway, and cathepsin B can activate trypsinogen in vitro; however, exposure of acini to a thiol protease inhibitor (E64) did not block this conversion. Conversion was inhibited by the serine protease inhibitor, benzamidine, and by raising the intracellular pH, using chloroquine or monensin. This limited proteolytic conversion appears to require a low pH compartment and a serine protease activity. After long periods of treatment (60 minutes), the amounts of the active enzyme forms began to decrease; this observation suggested that the active enzyme forms were being degraded. Treatment of acini with E64 reduced this late decrease in active enzyme forms, suggesting that thiol proteases, including lysosomal hydrolases, may be involved in the degradation of the active enzyme forms. These findings indicate that pathways for zymogen activation as well as degradation of active enzyme forms are present within the pancreatic acinar cell.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adler G., Gerhards G., Schick J., Rohr G., Kern H. F. Effects of in vivo cholinergic stimulation of rat exocrine pancreas. Am J Physiol. 1983 Jun;244(6):G623–G629. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1983.244.6.G623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvan P., Castle J. D. Phasic release of newly synthesized secretory proteins in the unstimulated rat exocrine pancreas. J Cell Biol. 1987 Feb;104(2):243–252. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvan P., Chang A. Constitutive protein secretion from the exocrine pancreas of fetal rats. J Biol Chem. 1987 Mar 15;262(8):3886–3890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A. J., Kembhavi A. A., Brown M. A., Kirschke H., Knight C. G., Tamai M., Hanada K. L-trans-Epoxysuccinyl-leucylamido(4-guanidino)butane (E-64) and its analogues as inhibitors of cysteine proteinases including cathepsins B, H and L. Biochem J. 1982 Jan 1;201(1):189–198. doi: 10.1042/bj2010189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialek R., Willemer S., Arnold R., Adler G. Evidence of intracellular activation of serine proteases in acute cerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991 Feb;26(2):190–196. doi: 10.3109/00365529109025030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figarella C., Miszczuk-Jamska B., Barrett A. J. Possible lysosomal activation of pancreatic zymogens. Activation of both human trypsinogens by cathepsin B and spontaneous acid. Activation of human trypsinogen 1. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1988 May;369 (Suppl):293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaisano H. Y., Klueppelberg U. G., Pinon D. I., Pfenning M. A., Powers S. P., Miller L. J. Novel tool for the study of cholecystokinin-stimulated pancreatic enzyme secretion. J Clin Invest. 1989 Jan;83(1):321–325. doi: 10.1172/JCI113877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geokas M. C., Rinderknecht H. Free proteolytic enzymes in pancreatic juice of patients with acute pancreatitis. Am J Dig Dis. 1974 Jul;19(7):591–598. doi: 10.1007/BF01073012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T., Saluja A., Ramarao P., Lerch M. M., Saluja M., Steer M. L. Apical secretion of lysosomal enzymes in rabbit pancreas occurs via a secretagogue regulated pathway and is increased after pancreatic duct obstruction. J Clin Invest. 1991 Mar;87(3):865–869. doi: 10.1172/JCI115091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach S. D., Modlin I. M., Scheele G. A., Gorelick F. S. Intracellular activation of digestive zymogens in rat pancreatic acini. Stimulation by high doses of cholecystokinin. J Clin Invest. 1991 Jan;87(1):362–366. doi: 10.1172/JCI114995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshio G., Saluja A., Steer M. L. Effects of short-term pancreatic duct obstruction in rats. Gastroenterology. 1991 Jan;100(1):196–202. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90601-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L., Ravazzola M., Anderson R. G. The condensing vacuole of exocrine cells is more acidic than the mature secretory vesicle. Nature. 1987 Mar 5;326(6108):77–79. doi: 10.1038/326077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade G. Intracellular aspects of the process of protein synthesis. Science. 1975 Aug 1;189(4200):347–358. doi: 10.1126/science.1096303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S. R. Mannose 6-phosphate receptors and their role in targeting proteins to lysosomes. J Membr Biol. 1988 Jul;103(1):7–16. doi: 10.1007/BF01871928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saluja A. K., Saluja M., Printz H., Zavertnik A., Sengupta A., Steer M. L. Experimental pancreatitis is mediated by low-affinity cholecystokinin receptors that inhibit digestive enzyme secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Nov;86(22):8968–8971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheele G., Adler G., Kern H. Exocytosis occurs at the lateral plasma membrane of the pancreatic acinar cell during supramaximal secretagogue stimulation. Gastroenterology. 1987 Feb;92(2):345–353. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer M. L., Meldolesi J., Figarella C. Pancreatitis. The role of lysosomes. Dig Dis Sci. 1984 Oct;29(10):934–938. doi: 10.1007/BF01312483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer M. L., Meldolesi J. Pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Annu Rev Med. 1988;39:95–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.39.020188.000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer M. L., Meldolesi J. The cell biology of experimental pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1987 Jan 15;316(3):144–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198701153160306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendrell J., Cuchillo C. M., Avilés F. X. The tryptic activation pathway of monomeric procarboxypeptidase A. J Biol Chem. 1990 Apr 25;265(12):6949–6953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemer S., Bialek R., Adler G. Localization of lysosomal and digestive enzymes in cytoplasmic vacuoles in caerulein-pancreatitis. Histochemistry. 1990;94(2):161–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02440183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemer S., Elsässer H. P., Adler G. Hormone-induced pancreatitis. Eur Surg Res. 1992;24 (Suppl 1):29–39. doi: 10.1159/000129237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H., Kimura T., Mimura K., Nawata H. Activation of proteases in cerulein-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1989;4(5):565–571. doi: 10.1097/00006676-198910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]