Summary

CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells (Tregs) play a central role in the suppression of immune responses thus serving to induce tolerance and to control persistent immune responses that can lead to autoimmunity. Here we explore if Tregs also play a role in controlling the immediate hypersensitivity response of mast cells (MCs). Tregs directly inhibit the FcεRI-dependent degranulation of MCs through cell-cell contact involving OX40-OX40L interactions between Tregs and MCs, respectively. MCs show increased cAMP levels and reduced Ca2+ influx, independent of PLC-γ2 or Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Antagonism of cAMP in MCs reverses the inhibitory effects of Tregs restoring normal Ca2+ responses and degranulation. Importantly, the in vivo depletion or inactivation of Tregs causes enhancement of the anaphylactic response. The demonstrated cross-talk between Tregs and MCs defines a previously unrecognized mechanism controlling MCs degranulation. Loss of this interaction may contribute to the severity of allergic responses.

Keywords: allergy, cAMP, calcium, IgE, mast cells, regulatory T cells

Introduction

Allergies are increasing in prevalence in the population of western countries (Ring et al., 2001). Allergic hypersensitivity is associated with both immunoglobulin (Ig) E and T helper 2 (Th2) responses to environmental allergens. In allergic individuals, priming of allergen-specific CD4+ Th2 cells by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) results in the production of Th2 cytokines, which are responsible for initiating B cell production of allergen-specific IgE. IgE binds to the high-affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E (FcεRI) on mast cells (MCs) and basophils. Allergen cross-linking of cell surface bound allergen-specific IgE leads to the release of preformed and granule stored allergic mediators like histamine, as well as the secretion of de novo synthesized prostaglandins, cysteinyl leukotrienes, cytokines and chemokines. Granule stored mediators are key to the immediate (acute) allergic reactions such as the wheal and flare response in the skin (Williams and Galli, 2000) whereas de novo synthesized mediators are more important in the late (chronic) phase of the allergic response.

The homeostatic mechanisms regulating MCs number and function in peripheral tissues are largely dependent on Th2-cytokines, such as IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13 (Shelburne and Ryan, 2001). Some of these cytokines are key in enhancing MCs survival (IL-3) or recruitment (IL-9) to effector sites, but in general Th2-cytokines establish a positive feedback that maintains the Th2 response (Lorentz et al., 2005). Environmental factors, such as exposure to allergens, infections and air pollution, interact with genetic factors to influence the progression of the immune response towards a Th2 phenotype, resulting in allergen-specific IgE production and subsequent allergen-mediated activation of MCs promoting allergic disease (Umetsu et al., 2002). However, the immunological mechanisms that controls in vivo Th2-driven inflammation, or that dampen MC-mediated allergic response, are not fully understood.

Regulatory T cells are crucial in preventing the development of autoimmune diseases, in maintaining self-tolerance and in regulating the development and the intensity of the immune response to foreign-antigens, including allergens (Lohr et al., 2006). In recent years, the naturally occurring CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) and an inducible population of allergen-specific IL-10-secreting type 1 Tregs (TR1) have been implicated in promoting or suppressing allergic diseases (Akdis, 2006; Wing and Sakaguchi, 2006). Allergen-specific Tregs and TR1 cells are though to control allergy by secreting IL-10 and TGF-β, suppressing IgE production by B cells and decreasing Th2 cytokines thus indirectly inhibiting the effector functions of MCs and basophils.

In this study, we investigated the possibility that Tregs might directly modulate the acute phase of allergic reactions by affecting the FcεRI-initiated MCs degranulation. This was based on previous findings demonstrating that MCs can physically interact with T cells (Bhattacharyya et al., 1998) and are essential intermediaries in Treg tolerance (Lu et al., 2006). Our findings show that CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs are able to dampen the release of pre-stored allergic mediators from MCs through an OX40-OX40L-dependent mechanism. The interaction of Tregs with MCs impaired the influx of extracellular Ca2+ following FcεRI triggering. This was not a consequence of impaired phospholipase C-γ (PLC-γ2) activation or defective Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. The Treg-mediated suppression was accompanied by increased cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in the suppressed MCs and antagonism of cAMP reversed the inhibitory effect of Tregs on MCs, demonstrating that cAMP increase in MCs is the likely mechanism for suppression of Ca2+ influx. Finally, in vivo depletion or inactivation of Tregs enhanced the extent of histamine release in a mouse model of systemic anaphylaxis, a common IgE-mediated type I hypersensitivity reaction involving MCs degranulation. These findings underscore the broad immunosuppressive efficacy of Tregs by demonstrating their control on immediate allergic responses.

Results

Tregs impair FcεRI-mediated MCs degranulation through cell-cell contact requiring OX40-OX40L interaction

MCs are activated in various T cell-mediated inflammatory processes, reside in physical proximity to T cells and contribute to T cell recruitment, activation and proliferation (Kashiwakura et al., 2004; Nakae et al., 2006). On the other hand, T cell-derived cytokines and adhesion molecule-dependent contact between effector T cells and MCs result in the release of both preformed granule contents and de novo synthesized cytokines from the latter (Inamura et al., 1998). However, it is not known whether Tregs can be found in contact with MCs in vivo and if they can directly affect the immediate hypersensitivity response of MCs.

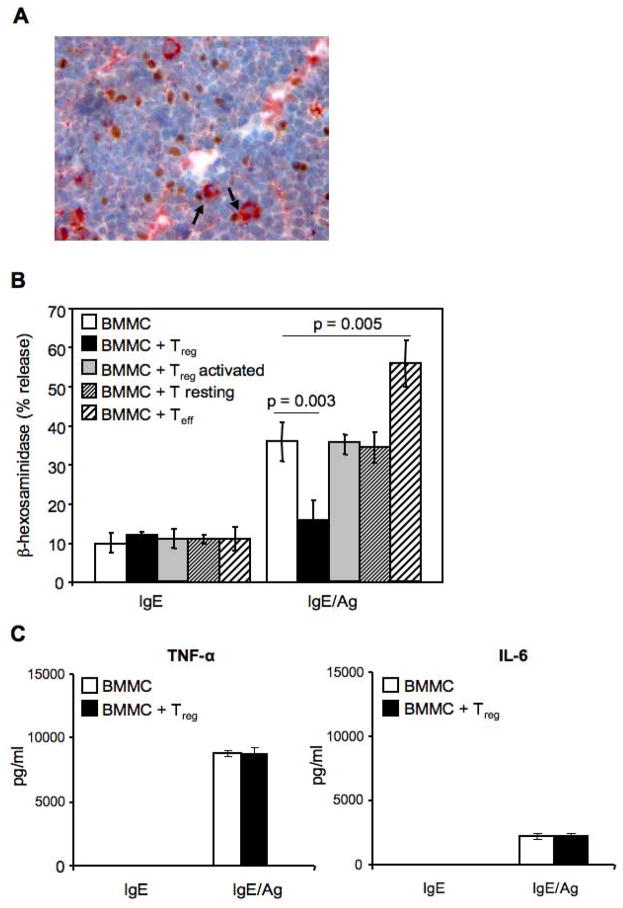

Immunohistochemical analysis of inguinal lymph node of C57BL/6 mice revealed FcεRI+ MCs in close proximity to Foxp3+ Tregs suggesting the possible cross talk between these two cell types (Figure 1A). Our initial experiments explored the consequences of different T cell subsets on FcεRI-initiated degranulation of bone marrow derived-cultured MCs (BMMCs) from C57BL/6 mice (Figure 1B). MCs were activated in the presence of equal number of syngenic Tregs, resting or activated CD4+ T cells. Degranulation was measured by the release of the MCs granule-associated enzyme β-hexosaminidase. As shown in Figure 1B, Tregs significantly inhibited BMMCs degranulation, with IgE/Ag-stimulated MCs alone releasing 36 ± 5% of their granule contents compared with 16 ± 5 % for MCs co-incubated with Tregs (p = 0.003). In contrast, anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 activated CD4+ T cells (Teff) significantly enhanced MCs IgE/Ag-dependent degranulation (56 ± 6 % degranulation; p = 0.005), in agreement with previous findings (Inamura et al., 1998). Tregs from BALB/c mice co-cultured with syngenic BMMCs showed similar ability to inhibit MCs degranulation (Supplemental, Figure S1). The Ag-induced release of neither TNF-α nor IL-6 was affected by the presence of Tregs when compared with BMMCs cultured alone (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. In vivo co-localization of Foxp3+ Tregs and mast cells and in vitro impairment of IgE-mediated degranulation of BMMCs by Tregs.

(A) Inguinal lymph node sections were stained with mouse anti-rat-FcεRIβ (red) and rat anti-mouse-Foxp3 Ab (brown). Arrows indicate cell-cell contact. Original magnification 400X. (B) BMMCs sensitized with IgE anti-DNP (IgE) and challenged with Ag (IgE/Ag) in the absence or presence of equal amount of CD4+CD25+ Tregs (Treg), or CD4+CD25− T cells (T resting) or a-CD3- plus a-CD28-stimulated CD4+CD25− effector T cells (Teff), were examined for release of β-hexosaminidase expressed as percentage of the cells’ total mediator content. Shown are the means ± SD of four independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. (C) TNF-α and IL-6 levels were evaluated in the supernatants of BMMCs-Tregs co-cultures. Shown are the means ± SD of three independent experiments.

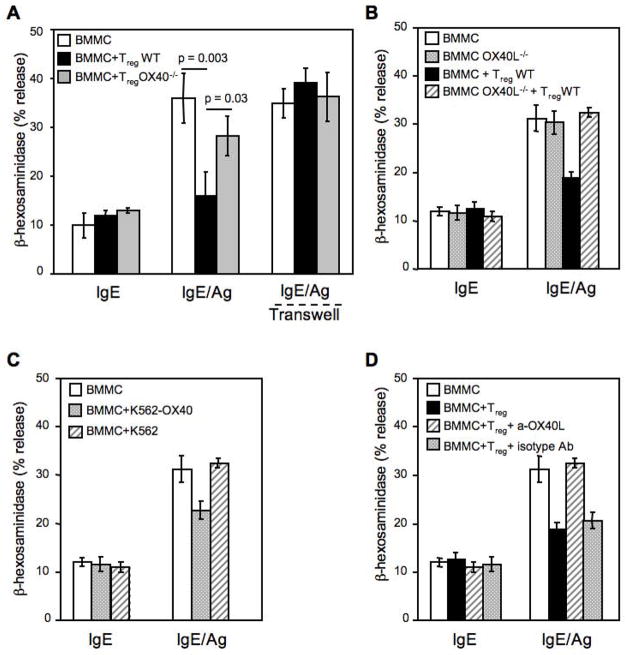

Increasing the Tregs:MCs ratio or pre-incubating the two cell types for up to 30 minutes before Ag challenge did not cause a further decrease in MCs degranulation (data not shown), indicating that a rapid mechanism for MCs inhibition by Tregs underlies the observed effect. This also suggested that cell-cell contact might be important since de novo production of cytokines normally requires few hours post-stimulation. To explore this possibility, degranulation was assayed using a transwell to separate Tregs and MCs. Figure 2A shows that the inhibition of FcεRI-dependent MCs degranulation by Tregs is abolished when MCs and Treg cells are separated by the transwell membranes, thus revealing the requirement for cell-cell contact.

Figure 2. The contact-dependent inhibitory role of Tregs on MCs degranulation depends on Tregs OX40 expression and requires OX40L on BMMCs.

(A) BMMCs sensitized with mouse IgE anti-DNP (IgE) and challenged with Ag (IgE/Ag) in the absence or presence of equal amount of WT or OX40−/− CD4+CD25+ Tregs or separated by a transwell membrane (Transwell) were then examined for release of β-hexosaminidase. (B) Same as (A), but BMMCs were obtained from WT or OX40L−/−mice and co-cultured with WT CD4+CD25+ Tregs. Shown are the means ± SD of three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. (C) IgE-sensitized BMMCs were challenged with Ag in the absence or presence of membranes from K562 cells expressing OX40 (K562-OX40) or empty vector (K562). (D) IgE-sensitized BMMCs were challenged with Ag in presence of Tregs, plus blocking anti-OX40L (clone MGP34) or isotype control (rat IgG2c) antibodies.

MCs constitutively express OX40L, which mediates MC-induced T cell proliferation in vitro (Kashiwakura et al., 2004; Nakae et al., 2006). OX40 is constitutively expressed on naïve and activated Tregs and its signal can modulate Treg suppression of effector T cells (Takeda et al., 2004; Valzasina et al., 2005) Thus, we investigated whether OX40L expressed on MCs and the constitutive expression of OX40 on Tregs might function to mediate the inhibitory effect of Tregs on MCs activation. As shown in Figure 2A, Tregs isolated from OX40−/− mice poorly inhibited MCs degranulation (with responses of IgE/Ag-activated MCs at 36 ± 5 compared with 28 ± 4 % degranulation in the presence of OX40−/− Tregs, however, this difference was not significant). This suggested a dominant mechanism of inhibition mediated by OX40 on Tregs, although other interactions or factors might contribute a minor component of the inhibitory effect on MCs.

The reverse experiment showed the importance of OX40L in MCs for Treg-mediated inhibition, as BMMCs differentiated from OX40L-deficient mice (OX40L−/−) were completely resistant to the Tregs inhibitory effect (Figure 2B). The presence of OX40 on wild type (WT) and its absence on OX40−/− Tregs, as well as the presence of OX40L on unstimulated or IgE/Ag-stimulated BMMCs, or its absence in OX40L−/− BMMCs was demonstrated by flow cytometry (Supplemental, Figure S2 and S3A, respectively). To explore whether the triggering through OX40/OX40L is required for inhibitory effect on MCs, BMMCs were stimulated in the presence of OX40-expressing membranes derived from the chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cell line or were incubated with Treg in presence of an OX40L blocking antibody. Figure 2C shows that OX40-expressing K562 membranes also elicited an inhibitory effect on MC degranulation, although weaker than in presence of Tregs. Additionally, when BMMCs were incubated with a blocking anti-OX40L antibody the inhibitory effect of Tregs on MC degranulation was reversed (Figure 2D). FcεRI expression was not altered by OX40L-deficiency nor modulated in BMMCs in the presence of WT or OX40−/− Tregs (Supplemental, Figure S3B and S3C). No major differences were observed between OX40−/− and WT Tregs in expression of other costimulatory molecules (Supplemental Figure S3D). These experiments demonstrated that OX40-OX40L interactions between Tregs and MCs, respectively, appear to be the unique requirement for the dampening of MCs degranulation.

MC-Treg OX40-mediated interaction inhibits Ca2+ influx independent of PLC-γ activation or intracellular Ca2+ mobilization

To explore the underlying mechanism for the inhibitory effect of Tregs on MCs degranulation, we investigated signaling events known to be essential for MCs degranulation. Very little is known about the signals generated subsequent to OX40L stimulation, but it has been published that OX40L engagement results in the rapid translocation of the Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C (PKC) β to the membrane of human airway smooth muscle cells (Burgess et al., 2004). Ca2+ mobilization and PKCβ activation are known to be absolutely essential for MCs degranulation (Blank and Rivera, 2004). Ca2+ mobilization is initiated by the phosphorylation of PLC-γ following FcεRI engagement, which leads to the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate to inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 causes mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) from endoplasmic reticular stores, whereas DAG and Ca2+ act in concert to promote activation of Ca2+-dependent PKCs, like PKC-β. The emptying of internal stores triggers Ca2+ influx from external sources, a step required for MCs degranulation (Gilfillan and Tkaczyk, 2006).

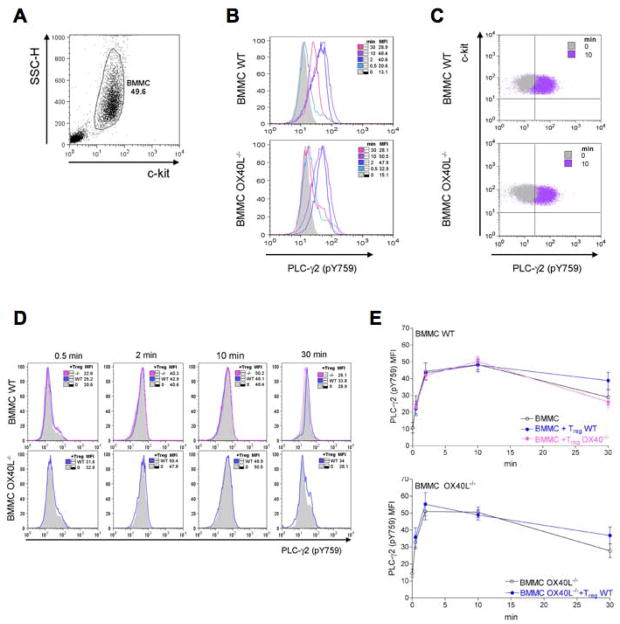

We first explored whether a defect in the activation of PLC-γ2 (as measured by phosphorylation at Y759 site, known to be required for lipase activity) was defective. The −γ2 isoform was chosen for its essential role in MCs degranulation (Wen et al., 2002). Rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of the PLC-γ2 isoform was detected upon FcεRI engagement in both WT and OX40L−/− BMMCs (Figure 3A, B and C). While a trend towards a slightly more transient phosphorylation was observed in OX40L−/− BMMCs, this was not significant. Moreover, the presence of WT or OX40−/− Tregs did not significantly alter the phosphorylation of PLC-γ2 in either WT or OX40L−/− BMMCs (Figure 3D and E).

Figure 3. Tregs do not affect FcεRI-dependent PLC-γ phosphorylation.

WT or OX40L−/− sensitized BMMCs were stimulated with Ag in the presence of WT or OX40−/− Tregs for the indicated times. Cells were immediately fixed and stained for c-kit and phosphorylated PLC-γ2. From c-kit+-gated BMMCs (A), histogram overlays of phosphorylated PLC-γ2 at different time points were obtained from WT (upper panels) or OX40L−/− (lower panels) BMMCs challenged in absence of Tregs (B). Dot plot overlay of basal phosphorylated PLC-γ2 (left, gray) and after 10 min (right, violet) is shown in panel C. Histogram overlays of phosphorylated PLC-γ2 from WT (upper panels) or OX40L−/− (lower panels) BMMCs challenged in the presence of Tregs (D). Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. Kinetics of PLC-γ2 phosphorylation at different conditions are shown in panel E and are the mean + SD of three independent experiments.

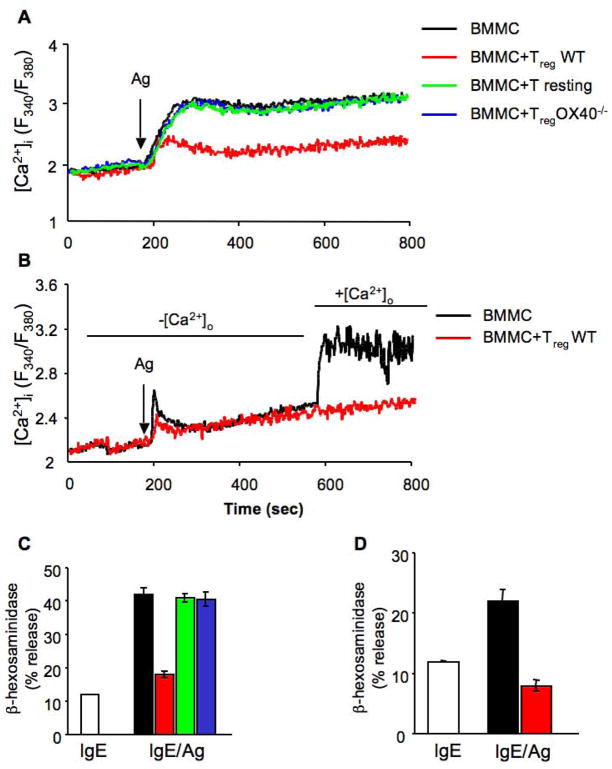

Recent studies demonstrated that in MCs extracellular Ca2+ influx can be regulated independently of PLC-γ, for example through the activity of sphingosine kinase 2 (Olivera et al., 2007). Thus, investigating the effects of WT and OX40−/− Tregs on the Ca2+ response of MCs was warranted. Interestingly, we observed that FcεRI-dependent Ca2+ mobilization in MCs is impaired in the presence of WT but not OX40−/− Tregs (Figure 4A). As PLC-γ2 activation was largely unaffected, this suggested that the effect on Ca2+ mobilization was likely independent from the emptying of intracellular stores. Indeed, the depletion of extracellular Ca2+ showed that MCs had a relatively normal mobilization of Ca2+ from intracellular stores in the presence of Tregs. However, restoration of Ca2+ in the extracellular medium revealed a considerable defect in Ca2+ influx (Figure 4B). The ability or inability of these MCs to flux Ca2+ across the plasma membrane in the absence or presence of Tregs was consistent with their normal or decreased MCs degranulation, respectively (Figure 4C and D).

Figure 4. Reduced FcεRI-dependent Ca2+ influx following BMMC-Treg engagement, but not intracellular Ca2+ mobilization.

(A) BMMCs loaded with FURA-2AM were stimulated via FcεRI in the absence (BMMC, black line) or presence of CD4+CD25− T cells (T resting, green line), WT CD4+CD25+ Tregs (red line) or OX40−/− CD4+CD25+ Tregs (blue line) and fluorescence emission was monitored. (B) FURA-2AM-loaded BMMCs were stimulated via FcεRI and co-cultured with WT CD4+CD25+ Tregs (red line) in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. 400 sec after Ag stimulation, 2μM Ca2+ was added to the medium and fluorescence emission was monitored. (C and D) At the end of each experiment, 14 minutes after Ag addition, percentage of β-hexosaminidase release from individual sample, was measured. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

cAMP is involved in Tregs-mediated suppression of BMMCs activation

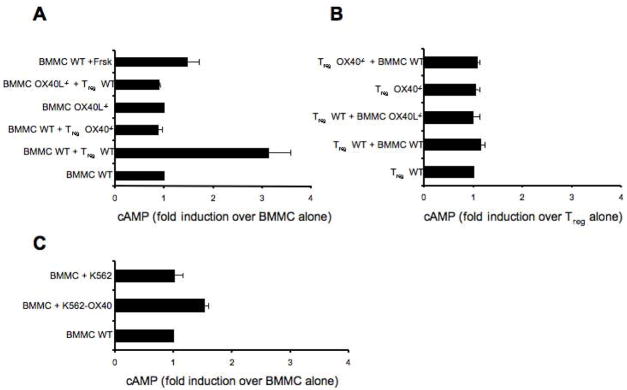

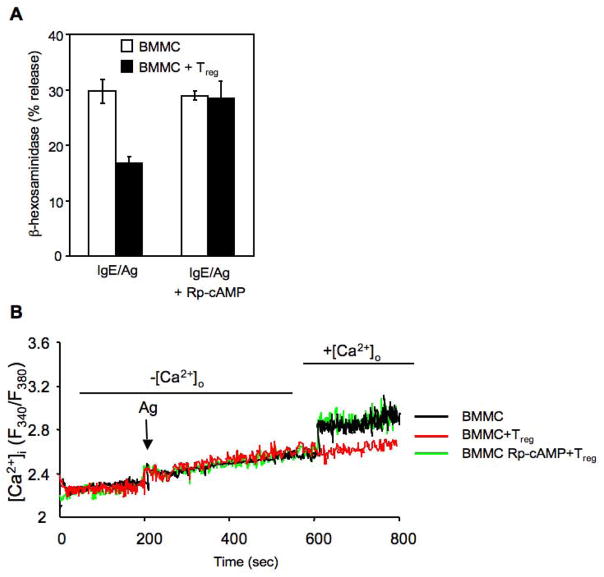

Our data indicated that Tregs directly inhibited MC degranulation by cell-cell contact, through the interaction of OX40 on Tregs with OX40L on MCs, resulting in the suppression of Ca2+ influx in MCs upon FcεRI stimulation. However, how these events are linked remained to be explored. Tregs have been reported to block effector T cell functions by producing cAMP. Thus, one possibility was that Treg-mediated suppression of MCs might occur through Treg production of cAMP, which could lead to decreased Ca2+ influx and suppression of degranulation in BMMCs, as recently shown (Hua et al., 2007). We first confirmed this effect by treating MCs with forskolin, which raises the intracellular cAMP concentration, and found that this treatment caused inhibition of MCs degranulation (Supplemental, Figure S4) and induced a 1.5 fold increase in cAMP levels in BMMCs (Figure 5A). When IgE/Ag-activated BMMCs were incubated in the presence of Tregs, cAMP levels in sorted BMMCs increased by approximately 3 fold (Figure 5A). No increase in cAMP was observed when BMMCs were co-cultured with OX40−/− Tregs or when OX40L−/− BMMC were co-cultured with Tregs (Figure 5A). No significant differences were found in the intracellular levels of cAMP in WT and OX40−/− Tregs alone or co-incubated with BMMCs (Figure 5B). Therefore, these findings showed that constitutive OX40-OX40L interaction between Tregs and MCs resulted in significant increase of cAMP only in the MCs. To address the possibility that OX40-OX40L interactions might enhance gap junction formation, resulting in cAMP transfer from Tregs to MCs as previously described for Treg-Teffector interactions (Bopp et al., 2007), we first incubated BMMCs with OX40-expressing membranes from the K562 cell line and found cAMP increase MCs, albeit at lower levels than with intact cells (Figure 5C). This was consistent with the more modest inhibitory effect of such OX40-expressing membranes on MC degranulation (Figure 2C), which likely reflects a less extensive engagement of OX40L by K562 OX40-expressing membranes relative to intact Tregs. To fully exclude the passage of cAMP from Tregs to MCs, we measured the transfer of calcein, a dye that diffuses only via gap junction (Fonseca et al., 2006), and found no transfer (Supplemental, Figure S5). These data suggest that the rise of cAMP in MCs is likely to result from intracellular signals induced by Tregs to MCs through OX40L engagement. To determine if the reversal of cAMP increase would cause reversal of the inhibitory effects, we pretreated MCs with the antagonist Rp-cAMP (shown to block cAMP-dependent PKA activity) and then tested MCs degranulation and Ca2+ mobilization in presence of Tregs. Treatment with Rp-cAMP did not alter either cell viability or the threshold of MCs activation (data not shown). Rp-cAMP treated BMMCs were resistant to the inhibitory effects of Tregs upon FcεRI stimulation, showing a degranulation response identical to FcεRI-stimulated MCs in the absence of Tregs (Figure 6A). Moreover, in presence of the Rp-cAMP the uptake of extracellular Ca2+ was unaffected by the presence of Tregs (Figure 6B).

Figure 5. Intracellular levels of cAMP are increased in BMMCs after co-culture with WT but not with OX40-deficient Tregs.

Sensitized WT and OX40L−/− BMMCs were CFSE-labeled and Ag-stimulated alone or with WT or OX40−/− Tregs. BMMCs and Tregs were separated using FACS-based cell sorting and cytosolic cAMP concentrations were measured using a cAMP-specific ELISA. As positive control sensitized BMMCs were incubated with forskolin and challenged with Ag. (A) BMMCs baseline [cAMP] was 10 pmoles/1×105. Results are expressed as fold induction over BMMCs alone. (B) Tregs baseline [cAMP] was 50 pmoles/1×105. Results are expressed as fold induction over Tregs alone. (C) Sensitized BMMCs were activated with Ag plus K562 or K562-OX40 membranes. The mean ± SD of three independent experiments are shown.

Figure 6. Antagonism of cAMP effects in BMMCs reverses Treg-mediated suppression of degranulation and restores extracellular Ca2+ uptake.

(A) Anti-DNP IgE preloaded BMMCs were preincubated for 30 min with 1mM of the specific cAMP antagonist Rp-cAMPs. Cells were washed and activated with Ag separately (BMMC) or in co-culture with CD4+CD25+ Tregs (BMMC + Treg). After 30 min samples were examined for release of β-hexosaminidase as described. Shown are the means ± SD of three independent experiments each performed in duplicate. (B) IgE-sensitized BMMCs were preincubated for 30 min with 1mM of the specific cAMP antagonist Rp-cAMPs and Ca2+ mobilization was assessed.

Tregs control MCs’ ability to release histamine in vivo through constitutive OX40 expression

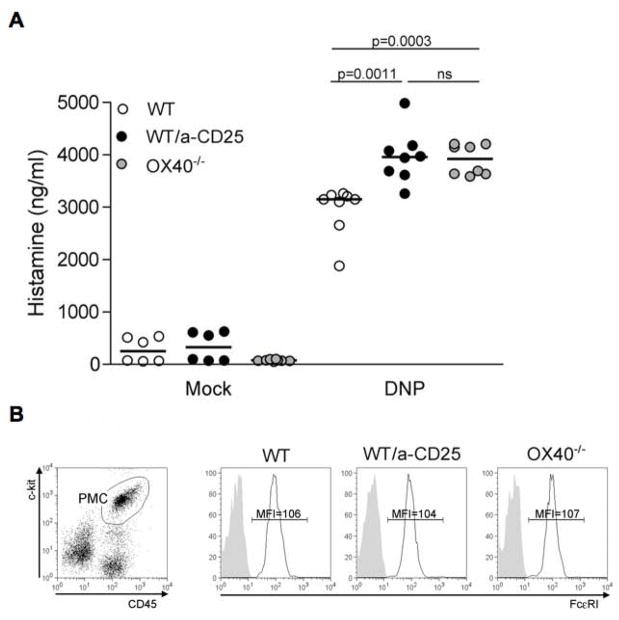

To evaluate the role of Tregs on the in vivo function of MCs we employed an FcεRI-mediated acute systemic anaphylaxis model. This model depends on MCs, as the observed increase in circulating histamine upon IgE/Ag stimulation is minimal in MC-deficient c-kit KO mice (W/Wv) and absent in MC-deficient stem-cell factor KO mice (Sl/Sld). We first explored the effect of OX40-deficiency on the anaphylactic response by use of C57BL/6 OX40−/− mice and the appropriate WT controls. As shown in Figure 7, OX40−/− mice had significantly (p=.001) higher levels of circulating histamine following challenge than WT mice. The increase in circulating histamine concentrations ranged from 20–35% of that seen in WT mice with a mean increase of approximately 25%. To directly assess the importance of Tregs, we used the approach of selectively depleting or inactivating these cells. C57BL/6 WT mice were treated with an anti-CD25 antibody (PC61 Ab) 7 and 8 days prior to IgE sensitization to deplete Treg. PC61 Ab was demonstrated to diminish Tregs numbers but also decrease CD25 expression levels (Kohm et al., 2006; Simon et al., 2007). Thus, we measured both CD25 and Foxp3 expression in PC61-treated mice. We observed that greater than 50% of Foxp3+ T cells were decreased in both circulating blood cells and lymph nodes, as well as a more marked decrease (greater than 80% in the lymph nodes) in CD25 expression by Foxp3+ T cells (Supplemental, Figure S6). Upon systemic anaphylactic challenge of Treg-depleted mice, circulating histamine levels mirrored those of OX40−/− mice showing a significant (p<.005) increase relative to WT controls (Figure 7A). No significant difference in FcεRI expression was detected in peritoneal MCs (CD45+/c-kit+) from non-IgE sensitized mice, thus excluding the possibility that anti-CD25 antibody treatment or OX40-deficiency might cause increased FcεRI expression and contribute to the observed in vivo effects, (Figure 7B). As differences in circulating IgE levels could affect the in vivo response of MCs by saturating FcεRI and increasing its expression (Yamashita et al., 2007), we measured serum IgE levels among OX40−/−, PC61-treated mice, and WT controls and found them to be similar among all mice used in these experiments (data not shown). To definitely prove the role of OX40 expressed by Tregs in controlling MCs degranulation, anaphylactic response was measured in Tregs-depleted thymectomized mice that have been left unreconstituted or reconstituted with WT or OX40-deficient Tregs (Figure 7C). Strikingly, exogenous WT but not OX40−/− Tregs were able to revert the increased in vivo MC degranulation occurring in Treg-depleted hosts, thus proving the essential role of OX40 in mediating MC suppression by Tregs.

Figure 7. Tregs via OX40 reduce in vivo systemic release of histamine by MCs.

(A) Plasma histamine levels were measured 1.5 minutes after challenge with PBS (mock) or DNP-HSA (Ag) in PC61-treated mice, OX40−/− mice and control WT littermates that were pre-sensitized with IgE anti-DNP (n = 8, each group). Results shown are pooled from two independent experiments. (B) CD45+ c-kit+ peritoneal mast cells (PMC, left panel) from unsensitized mice in each experimental group were stained for FcεRI (black lines) or isotype control (shaded areas). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) is indicated. (C) Thymectomized and anti-CD25 treated mice were left unreconstituted or received i.v. 3 weeks after 1 ×106 Tregs obtained from WT or OX40−/− donors. After 3 days passive systemic anaphylaxis was induced and plasma histamine measured as in (A).

Collectively, the findings demonstrate the importance of Tregs in suppressing FcεRI-induced MCs degranulation in vivo in an OX40-dependent manner.

Discussion

In recent years MCs have been recognized to influence or be influenced by dendritic cells, T and B cells, thus functioning as regulatory and/or effector cells (Sayed and Brown, 2007). However, little is known about this communication and the involvement of direct cell-cell contact. Since we found Tregs and MCs in close proximity in vivo, we investigated the consequence of their interaction on MC effector responses. Here, we report that Tregs (but not other T cell populations) can inhibit MC degranulation through cell-cell contact. Specifically, we found that the interaction of OX40-expressing Tregs with OX40L-expressing MCs inhibited the extent of MCs degranulation in vitro and of the immediate hypersensitivity response in vivo. These findings establish a previously unrecognized Treg-dependent regulation of MCs, whose alteration might result in pathology. The functional presence of OX40L on both human and mouse MCs (Kashiwakura et al., 2004; Nakae et al., 2006), suggests that this regulatory mechanism is conserved across species.

OX40−/− mice do not have a higher incidence of spontaneous allergic disease, but rather show impaired development of allergic inflammation due to the requirement for OX40 in the development of Th2 cells (Jember et al., 2001; Salek-Ardakani et al., 2003). Bypassing this requirement for Th2 polarization and directly challenging the effector arm (MCs) of an allergic response, we revealed a role for Treg-expressed OX40 as a negative regulator dampening the immediate hypersensitivity caused by MCs. Whether this control of MCs function extends beyond allergic responses is at the moment unclear. However, given the increasing evidence of a role for MCs in autoimmune diseases (Christy and Brown, 2007) and the demonstration that some organ specific autoimmune disease can be mediated through MC-derived histamine and serotonin (Binstadt et al., 2006), the Treg-MC interplay herein described is potentially relevant to the development of autoimmunity. Notably, mutations in the X-chromosome-encoded Foxp3 gene (leading to Tregs loss) were identified as the cause of the early-onset fatal autoimmune disorder observed in IPEX patients (immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome) and in scurfy mutant mice. Interestingly, in both humans and mice this immune dysregulation is associated with increased asthma and allergy (Patel, 2001) thus arguing for the need of Tregs in controlling allergic responses. While mouse models that are deficient in Tregs (such as scurfy mice), or even in T cells (such as Rag-deficient mice), may appear to be ideal for testing the role of the OX40-bearing Tregs in controlling allergic responses, mast cells are mislocalized in these mice and correct tissue redistribution does not occur upon reconstitution of the T cell compartment. In the scurfy mouse, the lymph nodes were devoid of mast cells (Alon Hershko and JR, unpublished observation), a site where close proximity of Tregs with mast cells was observed (Figure 1A). Thus, this apparent, and unexplained, abnormality prevented the use of such models. Nonetheless, use of Treg-depleted thymectomized mice reconstituted with WT or OX40−/− Tregs provided proof of an in vivo role for OX40-bearing Tregs in dampening mast cell-mediated allergic responses (Figure 7C).

OX40L−/− mice also display a significant reduction of Th2 responses (Arestides et al., 2002; Hoshino et al., 2003). However, like in OX40−/− mice, these effects can all be associated with the presence of OX40L on activated APC triggering Th2 polarization (Linton et al., 2003). Thus, while OX40-OX40L interaction is essential for Th2 cells activation, our study uncovers that it also controls the allergic response. Consistent with this view is the finding that induction of allergen-specific tolerant T cells caused a decrease in circulating histamine after allergen challenge in a mouse model of bronchial asthma (Treter and Luqman, 2000). This suppressive effect could not be entirely explained by reduced levels of allergen specific IgE, suggesting that tolerant T cells might act in another manner to modulate the FcεRI-dependent histamine release.

Treg-mediated control of degranulation transcends the MC, as granule exocytosis from cytotoxic T lymphocytes is inhibited in the presence of Tregs through their physical interaction (Mempel et al., 2006). Notably, the inhibitory effect of Treg on MC degranulation, although considerable, was not complete and did not affect cytokines production. This selective inhibition of MC responses may underlie the complex relationship between Tregs and MCs.

Considerable emphasis has recently been placed on the role of MCs as effectors in Treg tolerance. Unlike what described here, soluble factors like Treg-derived IL-9 play a key role in mediating MCs recruitment, and MC-secreted IL-10 and/or TGF-β are possible candidates in mediating the suppressive effects (Hawrylowicz and O’Garra, 2005; Lu et al., 2006). However, it remains to be determined if MC degranulation is impaired when these cells act as effectors in Treg-mediated tolerance. While it is well known that MCs can produce cytokines in the absence of degranulation (Theoharides et al., 2007), less is known about the impairment of MC degranulation when cytokines production is unaffected, but this type of effect is likely to require the selective dampening of signals.

The mechanism by which OX40-OX40L interaction drives inhibition of MCs degranulation involves increased cAMP content within MC. MCs degranulation requires Ca2+ influx through store-operated Ca2+ channels (SOCCs) that are sensitive to membrane potentials, which can be influenced by the ion balance across the plasma membrane. cAMP is known to alter the membrane potential, as observed in rat peritoneal MCs (Bradding, 2005; Penner et al., 1988). High cAMP concentrations within MCs were shown to cause decreased Ca2+ influx and inhibit degranulation (Hua et al., 2007). This inhibition is likely to result from the absolute requirement of the MC secretory granule fusion machinery for Ca2+ influx, as the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores alone is not sufficient to properly activate secretory fusion proteins (Blank and Rivera, 2004). Importantly, we found that drug-mediated antagonism of cAMP in OX40L-stimulated MCs reversed the decrease in Ca2+ influx and the inhibition of degranulation.

The inhibitory effect of cAMP also transcends the MCs, as Tregs suppression on Teff is wielded through cAMP transfer via gap junctions (Bopp et al., 2007). MCs express connexins and can form hexameric hemichannels, which do align in neighboring cells forming gap junctions during cell contact (Vliagoftis et al., 1999). Thus, cAMP transfer was plausible between Tregs and MCs. However, following the Treg-MC co-incubation, cAMP increase was detected ìn MCs without requiring an intact OX40+ cell, as OX40-expressing K562 cell membranes could also elicit cAMP production in MCs. Moreover, no decrease in intracellular cAMP concentration was apparent in Tregs after co-incubation, excluding the translocation of cAMP from Tregs to MCs. Finally, we failed to observe the transfer of calcein from Tregs to MCs suggesting that the increased cAMP elicited by OX40-OX40L interactions must be a result of OX40L signal in MCs triggering cAMP production. This argument is well supported by use of the antagonist Rp-cAMP, which reversed the effects of increased cAMP, namely inhibition of Ca2+ influx and of MC degranulation.

Direct antibody triggering of OX40L on MCs was not possible in this study, as the available antibodies are cross-reactive with the FcγR on MCs. Thus, signaling and function of OX40L on MCs remain to be elucidated. More is known about the effects of OX40 triggering on Tregs. Virtually all Tregs constitutively express OX40 at the naïve stage and OX40 engagement abolishes Tregs suppression in vitro and in vivo (Takeda et al., 2004; Valzasina et al., 2005). This would suggest that OX40 engagement by OX40L-expressing MCs might reverse Tregs suppressive function, even though the complex consequences of this effect require further investigation. There is mounting evidence that deficiency in Tregs number or function contributes to common allergic diseases and asthma. Here we find that the decrease in Tregs and/or loss of function increases the responsiveness of MCs in vivo. Glucocorticoids, the most effective treatment for allergy, as well as the agonist of histamine receptor 4, induce the activation of Tregs (Karagiannidis et al., 2004; Morgan et al., 2007). These findings suggest that the contribution of Tregs towards the reduction of allergy could be mediated not only by inhibition of T cell-driven inflammation, but also by direct regulation of the release of preformed pro-inflammatory mediators by MCs. Therefore, induction and expansion of Tregs could be a useful strategy in controlling allergen-mediated hypersensitivity.

Experimental Procedures

Mice, treatments and reagents

C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan (Harlan Italy), C57BL/6 OX40-deficient mice (OX40−/−) (Pippig et al., 1999) were from University of California at San Francisco (UCSF). Bone marrow from C57BL/6 OX40L-deficient mice (OX40L−/−) was kindly provided by A.H. Sharpe, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA. Mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility of Fondazione IRCCS “Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori” Milano. Animal experiments were authorized by the Institute Ethical Committee and performed in accordance to institutional guidelines and national law (DL116/92). For in vivo experiments mice received i.p. 0.5 mg/0.2 ml of anti-CD25 mAb (clone PC61, rat IgG1, ATCC, LGC Promochem, Milan, Italy) 7 days and 8 days prior to the systemic anaphylaxis induction. Anesthetized mice were thymectomized by suction method 4 days before PC61 injection and 3 weeks before i.v. transfer of 1.5 × 106 Treg. After 3 days systemic anaphylaxis was induced. Murine DNP-specific IgE was produced as described (Liu et al., 1980). DNP-human serum albumin (DNP36-HSA, Ag) and forskolin were from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy). Adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate, Rp-isomer, triethylammonium salt (Rp-cAMPs) was from Calbiochem (Merck Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany).

Lymph node immunolabeling

For double immunohistochemical staining, 4μm-thick sections were cut from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded inguinal lymph node samples from 8 weeks old C57BL/6. Slides were pre-incubated with protein block (Novocastra, UK), incubated with mouse anti-rat-FcεR (clone IRK) (Rivera et al., 1988) followed by biotinilated swine anti-mouse Ab, streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (LSAB+ kit, Dako, Denmark) and labeled using the Fast Red chromogenic substrate (Dako). Sections were incubated with the primary rat anti-mouse-Foxp3 Ab (clone FJK-16s, eBiosciences, San Diego, California), secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rat-Ig and labeled with hydrogen peroxide/diaminobenzidine (DAB+) (Dako). Imunohistochemical evaluation was performed using a Leica DM2000 optical microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany) and microphotographs were collected using Leica DFC320 digital camera (Leica Microsystems).

Purification of CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− subsets

CD4+CD25+ cells were purified using the CD25+ T-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry showed that the separated fractions were more than 90% Foxp3+(Supplemental, Figure S2). For some experiments CD4+CD25− T cells were stimulated 72 h with 1 μg/mL of plate-coated anti-CD3 plus 2.5 μg/mL of soluble anti-CD28 (both from eBioscience).

Bone marrow-derived mast cell differentiation, activation and FcεRI expression

BMMCs were obtained by in vitro differentiation of bone marrow cells taken from mouse femur as described (Frossi et al., 2007). After 5 weeks, BMMCs were monitored for FcεRI expression by flow cytometry. Purity was usually more than 97%. BMMCs were obtained from three to four mice and all experiments are performed using at least three individual BMMC cultures. Before experiments, 1 × 106/ml BMMCs were sensitized in medium without IL-3 for 4 hr with 1μg/ml of DNP-specific IgE and challenged with DNP-HSA in Tyrode’s buffer (10 mM HEPES buffer [pH 7.4], 130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 1mM MgCl2, 5.6 mM glucose, and 0.1% BSA). To measure FcεRI expression ex vivo, MCs were enriched from peritoneal lavage by 70% Percoll Gradient (GE Healthcare, UK) and stained with APC anti-CD45 Ab (clone 104), FITC anti-c-kit Ab (clone 2B8) and PE anti- FcεRI Ab (clone MAR-1), all from eBioscience.

β-hexosaminidase and cytokine release assay and PLC-γ2 phosphorilation

IgE pre-sensitized BMMCs were challenged in Tyrode’s buffer with Ag (100ng/ml) for 30 min in the presence or absence of equal amount of the indicated cell types. In some experiments BMMCs and T cells were separated by a 3.0 μm Transwell membrane (Corning Life Sciences, Acton, MA). In some experiments pre-sensitized BMMCs were incubated for 30 min with 10μg/ml blocking anti-OX40L (clone MGP34) (Murata et al., 2000) or isotype control (rat IgG2c) Ab before Ag challenge in presence of CD4+CD25+ Tregs. Samples were placed on ice and immediately centrifuged to pellet cells. The enzymatic activities of β-hexosaminidase in supernatants and in the cell pellets, after solubilizing with 0.5% Triton X-100 in Tyrode’s buffer, were measured with p-nitrophenyl N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide in 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 4.5) for 60 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of 0.2 M glycine (pH 10.7). The release of the product 4-p-nitrophenol was detected by absorbance at 405 nm. The extent of degranulation was calculated as the percentage of 4-p-nitrophenol absorbance in the supernatants over the sum of absorbance in the supernatants and in cell pellets solubilized in detergent. For cytokine analysis, IgE-sensitized BMMCs and Tregs were cultured alone or together for 16 h in presence of 100ng/ml Ag. Concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 were determined in supernatants using Mouse Inflammation Kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). To assess PLC-γ2 phosphorilation, BMMCs were Ag-stimulated in presence of Treg and fixed after the indicated time, immediately stained with a PE-conjugated anti-PLC-γ2 (pY759) Ab (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA) and FITC anti-c-kit Ab (clone 2B8, eBioscience). Flow cytometry data were acquired on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed with FlowJo software (version 8.5.2; Treestar Inc., Ashland, OR).

Expression of mouse OX40 by K562 cells and preparation of membranes

Human chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cells were stably transfected with empty pCDNA3 plasmid or pCDNA3 expressing murine OX40 molecule (OX40Dir 5′GCGAATTCAGAAAGCAGACAAGG3′; OX40Rev 5′CACTCGAGTACTAATGCTCAGAT 3′). OX40 positive K562 cell clones were identify by flow cytometry with anti-mouse OX40 antibody (OX86, BD Biosciences). Membranes from K562 and K562-OX40 cell clones were prepared as previously described (Merluzzi et al., 2008) and resuspended at a final concentration of 5 × 107 cell equivalents per ml based on the starting cell numbers. Membranes were added to IgE-sensitized BMMCs at dilution of 1:125v/v together with the Ag.

Intracellular Ca2+ determination

For Ca2+ measurements, 1 × 106 IgE-sensitized BMMCs were loaded with 3μM FURA-2AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in RPMI 2% FBS for 45 min at 37°C. Cells were washed in Tyrodes-BSA buffer (Saitoh et al., 2000), incubated in the presence of equal amounts of the indicated cell types and challenged with Ag (20 ng/ml). All fluorescence measurements (excitation and emission wavelengths, 340/380 and 505 nm, respectively) were performed in a Perkin-Elmer LS-50B spectrofluorimeter (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT) equipped with a thermostatically controlled cuvette holder and magnetic stirring. During the experiment, temperature was kept at 37°C. The changes in [Ca2+]i are expressed as a ratio of the light emitted at 505 nm upon excitation at the two wavelengths, 340 and 380 nm (F340/F380).

FACS-based cell sort and cAMP ELISA

To evaluate the intracellular levels of cAMP, pre-sensitized BMMCs were labeled for 15 min with 5μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFDA-SE; CFSE) (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, UK) and Ag-challenged in presence of Tregs. After co-culture, CFSE-labeled BMMCs and CD25PE-labeled Tregs were isolated using a MoFlo cell sorter (Dako). The purity of the sorted populations was >99%. As positive control, sensitized BMMCs were incubated with 25 μM forskolin for 1h before Ag stimulation. Cells were washed twice in PBS and lysed in 0,1M HCl/0,1% Triton X-100 (107/ml). cAMP levels were measured using Correlate EIA Direct cAMP assay (Assay Design, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Systemic Anaphylaxis

Mice were sensitized with 3 μg of mouse DNP-specific IgE by tail vein injection. 24 h later, mice were challenged i.v. with 0.5 mg of Ag or vehicle (PBS). After 1.5 min, mice were euthanized with CO2 and blood was withdrawn by cardiac puncture. Plasma histamine concentration was determined by ELISA according to the producer instruction (DRG Instruments GmbH, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the means ± SD. Data were analyzed using a nonpaired Student’s t test (Prism software, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministero dell’Istruzione Università e Ricerca (PRIN 2005), Agenzia Spaziale Italiana. (Progetto OSMA), AIRC (Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro) and LR.11 del Friuli Venezia Giulia. SP is supported by a fellowship from FIRC (Fondazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro). The work of JR and SO was supported by the National Insitute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Arlene H. Sharpe (Harvard) for providing OX40L−/− bone marrow and Ivano Arioli for technical assistance. We also thank Daniela Cesselli and Elisa Puppato for cell sorting. The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- Akdis M. Healthy immune response to allergens: T regulatory cells and more. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arestides RS, He H, Westlake RM, Chen AI, Sharpe AH, Perkins DL, Finn PW. Costimulatory molecule OX40L is critical for both Th1 and Th2 responses in allergic inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2874–2880. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2002010)32:10<2874::AID-IMMU2874>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya SP, Drucker I, Reshef T, Kirshenbaum AS, Metcalfe DD, Mekori YA. Activated T lymphocytes induce degranulation and cytokine production by human mast cells following cell-to-cell contact. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:337–341. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binstadt BA, Patel PR, Alencar H, Nigrovic PA, Lee DM, Mahmood U, Weissleder R, Mathis D, Benoist C. Particularities of the vasculature can promote the organ specificity of autoimmune attack. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:284–292. doi: 10.1038/ni1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank U, Rivera J. The ins and outs of IgE-dependent mast-cell exocytosis. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp T, Becker C, Klein M, Klein-Hessling S, Palmetshofer A, Serfling E, Heib V, Becker M, Kubach J, Schmitt S, et al. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate is a key component of regulatory T cell-mediated suppression. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1303–1310. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradding P. Mast cell ion channels. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;87:163–178. doi: 10.1159/000087643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess JK, Carlin S, Pack RA, Arndt GM, Au WW, Johnson PR, Black JL, Hunt NH. Detection and characterization of OX40 ligand expression in human airway smooth muscle cells: a possible role in asthma? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:683–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christy AL, Brown MA. The multitasking mast cell: positive and negative roles in the progression of autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2007;179:2673–2679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca PC, Nihei OK, Savino W, Spray DC, Alves LA. Flow cytometry analysis of gap junction-mediated cell-cell communication: advantages and pitfalls. Cytometry A. 2006;69:487–493. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frossi B, Rivera J, Hirsch E, Pucillo C. Selective activation of Fyn/PI3K and p38 MAPK regulates IL-4 production in BMMC under nontoxic stress condition. J Immunol. 2007;178:2549–2555. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilfillan AM, Tkaczyk C. Integrated signalling pathways for mast-cell activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:218–230. doi: 10.1038/nri1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawrylowicz CM, O’Garra A. Potential role of interleukin-10-secreting regulatory T cells in allergy and asthma. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:271–283. doi: 10.1038/nri1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino A, Tanaka Y, Akiba H, Asakura Y, Mita Y, Sakurai T, Takaoka A, Nakaike S, Ishii N, Sugamura K, et al. Critical role for OX40 ligand in the development of pathogenic Th2 cells in a murine model of asthma. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:861–869. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Kovarova M, Chason KD, Nguyen M, Koller BH, Tilley SL. Enhanced mast cell activation in mice deficient in the A2b adenosine receptor. J Exp Med. 2007;204:117–128. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamura N, Mekori YA, Bhattacharyya SP, Bianchine PJ, Metcalfe DD. Induction and enhancement of Fc(epsilon)RI-dependent mast cell degranulation following coculture with activated T cells: dependency on ICAM-1- and leukocyte function-associated antigen (LFA)-1-mediated heterotypic aggregation. J Immunol. 1998;160:4026–4033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jember AG, Zuberi R, Liu FT, Croft M. Development of allergic inflammation in a murine model of asthma is dependent on the costimulatory receptor OX40. J Exp Med. 2001;193:387–392. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannidis C, Akdis M, Holopainen P, Woolley NJ, Hense G, Ruckert B, Mantel PY, Menz G, Akdis CA, Blaser K, Schmidt-Weber CB. Glucocorticoids upregulate FOXP3 expression and regulatory T cells in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1425–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwakura J, Yokoi H, Saito H, Okayama Y. T cell proliferation by direct crosstalk between OX40 ligand on human mast cells and OX40 on human T cells: comparison of gene expression profiles between human tonsillar and lung-cultured mast cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:5247–5257. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohm AP, McMahon JS, Podojil JR, Begolka WS, DeGutes M, Kasprowicz DJ, Ziegler SF, Miller SD. Cutting Edge: Anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody injection results in the functional inactivation, not depletion, of CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:3301–3305. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton PJ, Bautista B, Biederman E, Bradley ES, Harbertson J, Kondrack RM, Padrick RC, Bradley LM. Costimulation via OX40L expressed by B cells is sufficient to determine the extent of primary CD4 cell expansion and Th2 cytokine secretion in vivo. J Exp Med. 2003;197:875–883. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu FT, Bohn JW, Ferry EL, Yamamoto H, Molinaro CA, Sherman LA, Klinman NR, Katz DH. Monoclonal dinitrophenyl-specific murine IgE antibody: preparation, isolation, and characterization. J Immunol. 1980;124:2728–2737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr J, Knoechel B, Abbas AK. Regulatory T cells in the periphery. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:149–162. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorentz A, Wilke M, Sellge G, Worthmann H, Klempnauer J, Manns MP, Bischoff SC. IL-4-induced priming of human intestinal mast cells for enhanced survival and Th2 cytokine generation is reversible and associated with increased activity of ERK1/2 and c-Fos. J Immunol. 2005;174:6751–6756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu LF, Lind EF, Gondek DC, Bennett KA, Gleeson MW, Pino-Lagos K, Scott ZA, Coyle AJ, Reed JL, Van Snick J, et al. Mast cells are essential intermediaries in regulatory T-cell tolerance. Nature. 2006;442:997–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature05010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mempel TR, Pittet MJ, Khazaie K, Weninger W, Weissleder R, von Boehmer H, von Andrian UH. Regulatory T cells reversibly suppress cytotoxic T cell function independent of effector differentiation. Immunity. 2006;25:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merluzzi S, D’Orlando O, Leonardi A, Vitale G, Pucillo C. TRAF2 and p38 are involved in B cells CD40-mediated APE/Ref-1 nuclear translocation: a novel pathway in B cell activation. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RK, McAllister B, Cross L, Green DS, Kornfeld H, Center DM, Cruikshank WW. Histamine 4 receptor activation induces recruitment of FoxP3+ T cells and inhibits allergic asthma in a murine model. J Immunol. 2007;178:8081–8089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K, Ishii N, Takano H, Miura S, Ndhlovu LC, Nose M, Noda T, Sugamura K. Impairment of antigen-presenting cell function in mice lacking expression of OX40 ligand. J Exp Med. 2000;191:365–374. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakae S, Suto H, Iikura M, Kakurai M, Sedgwick JD, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cells enhance T cell activation: importance of mast cell costimulatory molecules and secreted TNF. J Immunol. 2006;176:2238–2248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera A, Mizugishi K, Tikhonova A, Ciaccia L, Odom S, Proia RL, Rivera J. The sphingosine kinase-sphingosine-1-phosphate axis is a determinant of mast cell function and anaphylaxis. Immunity. 2007;26:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel DD. Escape from tolerance in the human X-linked autoimmunity-allergic disregulation syndrome and the Scurfy mouse. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:155–157. doi: 10.1172/JCI11966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner R, Matthews G, Neher E. Regulation of calcium influx by second messengers in rat mast cells. Nature. 1988;334:499–504. doi: 10.1038/334499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pippig SD, Pena-Rossi C, Long J, Godfrey WR, Fowell DJ, Reiner SL, Birkeland ML, Locksley RM, Barclay AN, Killeen N. Robust B cell immunity but impaired T cell proliferation in the absence of CD134 (OX40) J Immunol. 1999;163:6520–6529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring J, Kramer U, Schafer T, Behrendt H. Why are allergies increasing? Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:701–708. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(01)00282-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera J, Kinet JP, Kim J, Pucillo C, Metzger H. Studies with a monoclonal antibody to the beta subunit of the receptor with high affinity for immunoglobulin E. Mol Immunol. 1988;25:647–661. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(88)90100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh S, Arudchandran R, Manetz TS, Zhang W, Sommers CL, Love PE, Rivera J, Samelson LE. LAT is essential for Fc(epsilon)RI-mediated mast cell activation. Immunity. 2000;12:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salek-Ardakani S, Song J, Halteman BS, Jember AG, Akiba H, Yagita H, Croft M. OX40 (CD134) controls memory T helper 2 cells that drive lung inflammation. J Exp Med. 2003;198:315–324. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed BA, Brown MA. Mast cells as modulators of T-cell responses. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:53–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelburne CP, Ryan JJ. The role of Th2 cytokines in mast cell homeostasis. Immunol Rev. 2001;179:82–93. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.790109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon AK, Jones E, Richards H, Wright K, Betts G, Godkin A, Screaton G, Gallimore A. Regulatory T cells inhibit Fas ligand-induced innate and adaptive tumour immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:758–767. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda I, Ine S, Killeen N, Ndhlovu LC, Murata K, Satomi S, Sugamura K, Ishii N. Distinct roles for the OX40-OX40 ligand interaction in regulatory and nonregulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:3580–3589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides TC, Kempuraj D, Tagen M, Conti P, Kalogeromitros D. Differential release of mast cell mediators and the pathogenesis of inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:65–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treter S, Luqman M. Antigen-specific T cell tolerance down-regulates mast cell responses in vivo. Cell Immunol. 2000;206:116–124. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umetsu DT, McIntire JJ, Akbari O, Macaubas C, DeKruyff RH. Asthma: an epidemic of dysregulated immunity. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ni0802-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valzasina B, Guiducci C, Dislich H, Killeen N, Weinberg AD, Colombo MP. Triggering of OX40 (CD134) on CD4(+)CD25+ T cells blocks their inhibitory activity: a novel regulatory role for OX40 and its comparison with GITR. Blood. 2005;105:2845–2851. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vliagoftis H, Hutson AM, Mahmudi-Azer S, Kim H, Rumsaeng V, Oh CK, Moqbel R, Metcalfe DD. Mast cells express connexins on their cytoplasmic membrane. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:656–662. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen R, Jou ST, Chen Y, Hoffmeyer A, Wang D. Phospholipase C gamma 2 is essential for specific functions of Fc epsilon R and Fc gamma R. J Immunol. 2002;169:6743–6752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CM, Galli SJ. The diverse potential effector and immunoregulatory roles of mast cells in allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:847–859. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.106485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing K, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells as potential immunotherapy in allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6:482–488. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000246625.79988.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita Y, Charles N, Furumoto Y, Odom S, Yamashita T, Gilfillan AM, Constant S, Bower MA, Ryan JJ, Rivera J. Cutting edge: genetic variation influences Fc epsilonRI-induced mast cell activation and allergic responses. J Immunol. 2007;179:740–743. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.