Abstract

The human peripheral B cell compartment displays a large population of IgM+IgD+CD27+ “memory” B cell carrying a mutated Ig receptor. We show here, by phenotypic analysis, CDR3 spectratyping during a T-independent response and gene expression profiling of the different blood and splenic B cell subsets, that blood IgM+IgD+CD27+ cells correspond to circulating splenic marginal zone B cells. Furthermore, analysis of this peripheral subset in normal children below 2 years shows that these B cells develop and mutate their Ig receptor during ontogeny, prior to their differentiation into T-independent antigen-responsive cells. It is therefore proposed that these IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells provide the splenic marginal zone with a diversified and protective pre-immune repertoire in charge of the responses against encapsulated bacteria.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Aged; Antigens, CD27; Autoimmune Diseases; etiology; immunology; B-Lymphocytes; immunology; Blood Circulation; Child; Child, Preschool; Complementarity Determining Regions; analysis; Gene Expression Profiling; Gene Rearrangement, B-Lymphocyte; Humans; Immunoglobulin D; Immunoglobulin M; Immunologic Memory; genetics; Immunophenotyping; Infant; Middle Aged; Somatic Hypermutation, Immunoglobulin; Spleen; cytology

INTRODUCTION

The human peripheral B cell compartment displays, in contrast to the mouse, a large population of CD27+ memory B cells which carry a mutated Ig receptor and represent up to 40% of circulating B cells. These memory B cells include the classical isotype-switched B cells and a population of IgM+ B cells, which have been originally divided into an IgM-only, an IgM+IgD+ subset, and a minor IgD-only subpopulation [1]–[4].

The splenic marginal zone (SMZ) is a unique B cell compartment that contains B cells with a high surface density of IgM and complement receptor 2 (Cr2 or CD21), and which exhibits a rapid activation and Ig secretion in response to blood-borne T-independent (TI) antigens[5]–[7]. Human SMZ B cells have been shown to carry somatic mutations, and mutated antibodies can be raised after immunization with T-independent polysaccharidic vaccines [8]–[11].

We hypothesized previously that blood IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells might form a B cell subset distinct from the classical germinal center-derived memory B cells. This proposition was based on the fact that hyper-IgM (HIGM) patients who carry an invalidating mutation of the CD40L gene and do not possess normally developed germinal centers and switched memory B cells [12] still presented a subpopulation of circulating IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells [13],[14]. These B cells carried moreover a mutated Ig receptor, which led us to suggest that they could represent a different pathway of diversification that did not require a cognate T-B interaction and could thus be involved in T-independent immune responses [14]. We show here by phenotypic analysis, CDR3 spectratyping during a T-independent vaccination and gene expression profiling of the different blood and splenic B cell subset that the blood IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells correspond indeed to circulating splenic marginal zone B cells in charge of T independent responses, thus in accordance with a recent report [15] and our previous proposition.

METHODS

Biological samples

Fresh spleen samples were obtained from patients undergoing splenectomy due to spherocytosis. Blood and spleen samples were obtained after parental or patient’s informed consent. The complete diagnosis of asplenic patients is detailed in the results section.

Antibodies

The following antibodies coupled with biotin, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FTTC), R-phycoerythrin (PE), allophycocyanin (APC), Cy-Chrome™ (Cy) or with the tandem dye PE-Cyanin 5.1 (PC5) were used for flow cytometry or cell sorting: PC5-anti-CD19 (clone J4.119) and PE-anti-CD27 (clone 1A4-CD27) from Beckman Coulter (Fullerton, CA); APC-anti-CD19 (clone HIB19), Cy-anti-CD21 (clone B-Ly4), FTTC-anti-CD27 (clone M-T271), PE-anti-CD23 (clone M-L233) and biotin anti-IgD (clone IA6-2) from BD-Pharmingen (San Jose, CA); goat anti-human IgD-FITC and biotinylated goat F(ab′)2 anti-human IgM from Caltag (Burlingame, CA). Purified anti-CD1c (clone F10/21A3) was provided by Dr. B. Moody. Biotinylated and purified antibodies were revealed respectively with Streptavidin PE-Cy7 (PC7) and PE-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (Caltag). The following antibodies were used for the histological studies: anti-CD1c (clone F10/21A3), anti-CD20 (clone L26) and polyclonal rabitt anti-IgD (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), anti-CD27 mAb (137B4) from Novocastra Laboratories (Newcastle, UK).

Immunohistology

All the antibodies were detected using the Vectastain ABC elite kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The procedure has been decribed in detail elsewhere [16]. Briefly, serial cryosections of spleen tissue were fixed in cold isopropanol for 10 minutes. After blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity by a glucose oxidase method, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies. Bound antibodies were detected by biotinylated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (Dako) incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. The avidin-biotinylated peroxidase complex was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were incubated with the avidin-biotinylated peroxidase complex for 30 minutes at room temperature. After washing, peroxidase activity was revealed using diaminobenzidine (DAB). The monoclonal anti-CD27 (137B4) was visualized by a tyramide-enhanced ABC method.

Separation and Flow Cytometric Analysis of IgD+CD27+ B Cells

Human B cells from peripheral blood were enriched by negative selection with the RosetteSep™ B cell enrichment cocktail (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Splenic B cells were obtained after Ficoll density centrifugation and enrichment to >98% using the B cell negative isolation Kit (Dynal Biotech, Oslo, Norway). Three and four-color immunofluorescence analyses were performed on a FACScalibur® with the CellQuest™ software (Becton Dickinson). For isolation of splenic or peripheric IgD+CD27+, IgD− CD27+ and naive IgD+CD27− cells, purified B cells were stained with anti-IgD-FITC, anti-human CD27-PE and anti-CD 19-PC5 and sorted on a FACSvantage® (Becton Dickinson). For microarray analysis, the IgD+CD27+and IgD−CD27+ fractions were submitted to two successive sortings. For isolation of peripheral and splenic naive CD27− B cells, CD27+ B cells were first removed using CD27-magnetic beads and LD depletion columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany). Then, enriched naive B cells were stained and sorted as described above. Purity of all samples used for microarray analysis was □99%.

RNA Amplification and cDNA Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from sorted splenic and peripheral IgD+CD27+, IgD−CD27+ and naive cells using the RNeasy isolation Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA samples were amplified in duplicate using a standard two-round linear amplification protocol (Ambion) to obtain between 25 and 50 μg of cRNA. Gene expression profiling analysis was performed using Lymphochip microarrays [17]. Briefly, amplified cRNA was reverse transcribed, labeled with Cy5 and hybridized to the microarrays together with Cy3-labeled probes generated from a standard pool of RNA derived from 9 lymphoid cell lines.

Amplification and analysis of rearranged V3-23 genes

Genomic DNA was extracted from sorted cells by proteinase K digestion. Rearranged V3-23 gene segments were amplified with Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), using a semi-nested PCR strategy as previously described [14]. PCR products were gel-purified, cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning® kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and sequences of V3-23 positive colonies were obtained by automated sequencing (ABI310 genetic analyzer, Applera Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The sequences obtained were compared to the germline V3-23 gene over 288 bp (from Glu1 to Cys92).

H-CDR3 spectratyping

Total RNA from 5×104–105 sorted IgD+CD27+ and naive cells was reverse transcribed by random priming, using the ProSTAR™ First Strand RT-PCR Kit (Stratagene). Amplification of V3-15-Cμ transcripts was performed on 2 μl cDNA aliquots with AmpliTaq® DNA polymerase (Applera) using a V3-15-specific primer (V3-15 Leader: CTGAGCTGGATTTTCCTTGC) and an primer specific of the CH1 region of the μ heavy chain (μCH1: AAAAGGGTTGGGGCGGATGCAC) (45 s at 95°C, 60 s at 62°C, 90 s at 72°C for 25 cycles). V3-15-Cμ products were subjected to a second round of PCR amplification (45 s at 95°C, 60 s at 58°C, 90 s at 72°C for 25 cycles) using the same Cμ primer with an internal V3-15-specific FR3 primer (V3-15-FR3: CACAGCCGTGTATTACTGTAC). For H-CDR3 spectratyping, 1/5 to 1/10 of the purified PCR products were size fractionated on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by silver staining (Silver Sequence™ DNA Staining reagents, Promega, Madison, WI). Individual bands of interest (corresponding to a given CDR3 length) were excised from the gel and crushed in 10-μl water. Re-amplification was performed using 1μl of the excised PCR product for 20 cycles using the primers and PCR conditions described above. Several PCR amplifications were performed from two independent cDNAs for each cell sample.

RESULTS

The circulating IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cell subset displays a splenic marginal zone B cell phenotype

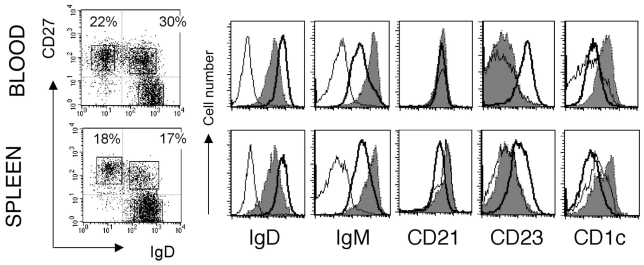

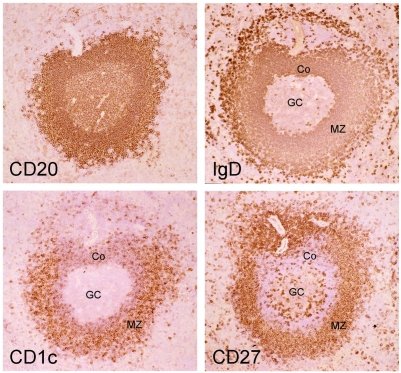

Mouse and human splenic marginal zone B cells can be distinguished from naive and switched B cells as being IgMhiIgDloCD21hiCD23− 6[18]. Mouse MZ B cells are CD1d+ 6, and it has been proposed that CD1c could be a MZ B cell marker in humans [19]. When human spleen B cells were analyzed with IgD and CD27 surface markers, they displayed a staining profile similar to the blood with a large compartment of CD27+ B cells (about 40%) divided into isotype-switched and IgD+ B cells (Fig. 1). The CD27+IgD+ B cells are IgMhiIgDloCD21hiCD23− and CD1chi as compared to naive B cells, thus displaying the phenotype of splenic marginal zone B cells. Staining of serial sections of a human spleen with CD20, CD27, IgD and CD1c revealed indeed a stronger expression of CD1c in B cells located in the marginal zone, and confirmed the marginal zone localization of IgDlowCD27+ B cells, as previously described [10] (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Blood and spleen IgM+IgD+CD27+ subsets share markers specific of marginal zone B cells.

Purified B cells from blood and spleen are analyzed separately for IgM, CD21, CD23 and CDlc surface expression after gating of the three different CD19-positive lymphocyte subsets distinguished by IgD and CD27 labelling. These data correspond to one representative case out of 4 different individuals. Naive B cells (IgD+CD27−), bold line; IgD+CD27+ B cells, grey shadow; IgD−CD27+, thin line. Percentages of cells in the two CD27+ quadrants are indicated. The absence of IgM-positive cells among the IgD−CD27+ subset is noticeable.

Figure 2. CDlc marks strongly splenic marginal zone B cells in humans.

Serial cryosections of an adult human spleen are stained with anti-CD20, anti-IgD, anti-CD 1c and anti-CD27 antibodies (ABC technique; Original magnification: 25X) Marginal zone B cells are IgDlow CD27+CDlchigh. Note the more intense staining for IgD of the corona (Co) compared to the marginal zone B cells (MZ) while the reverse is true for CDlc. The intense IgD staining of outer marginal zone B cells has been described previousl(16). GC, germinal center.

Similarly to the spleen, blood CD27+ B cells are divided into isotype-switched and IgD+ B cells. Here again, CD27+IgD+ B cells are IgMhigDloCD21+CD23− and CD1chi, although the CD21 marker stains similarly the different B cell subpopulations in this compartment (Fig. 1). In most cases, few cells were characterized as IgM-only within the IgD−CD27+ subset (Fig. 1). IgM-only CD27+ B cells represented 1.1% of blood B cells (a mean value estimated from 11 individuals), with the exception of a 2-year old child who displayed 7% of IgM-only B cells. Slightly higher values were observed for IgM-only CD27+ B cells in the spleen of children below 5 years (a mean value of 2.7% including a 22 month-old child with 7.5% IgM-only cells).

Ig gene mutation frequencies also correlate between splenic and blood compartments, being significantly lower in the IgM+IgD+CD27+ subset compared to switched B cells, as previously shown for the blood [1] (Table 1). Remarkably enough, in all IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cell samples analyzed from one year on, whether from spleen or blood, more than 90% of V sequences carried somatic mutations, thus indicating that the marginal zone compartment as a whole harbor mutated Ig genes.

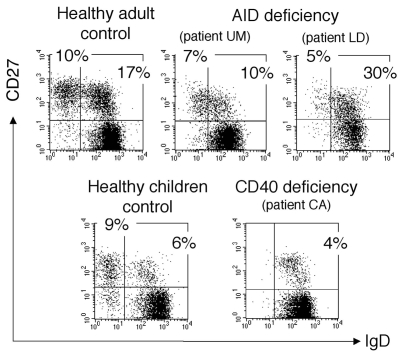

Different types of CD27+ B cell subsets in CD40- and AID-deficient children

We analyzed two other groups of HIGM patients, carrying an invalidating mutation either of the CD40 or of the AICDA gene encoding the activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID). The CD40-deficient patient (CA) is a 11-year old child with an homozygous mutation of the CD40 gene described by Ferrari et al.[20]. This patient shows a peripheral B cell staining profile similar to CD40L-deficient patients with a large naive compartment and an IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cell subpopulation (5 % of CD19+ cells) as the only “memory” subset (Fig. 3). Moreover, these IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells carry a mutated Ig receptor with a mutation frequency of 3.8 % measured on rearranged V3-23 genes, i.e. an average of 11 mutations per VH sequence (Table 2). We analyzed also 2 patients who bear invalidating mutations of the AICDA gene [21],[22]. One patient (LD) presents a homozygous R112C missense mutation[23]. Patient UM presents heterozygous mutations of the AICDA gene (a one bp deletion at nucleotide 490 on one allele and a A111T amino acid missense mutation on the other one). In contrast to CD40- and CD40L-deficient patients, AID-deficient patients do have germinal centers but are deficient in the hypermutation and isotype switch mechanisms [22]. Two different CD27+ B cell subsets are observed in these 2 patients: an IgM+IgD+ and an IgM-only subset, representing respectively 10–30% and 5–7% of the peripheral B cell pool (Fig. 3). The existence of a clear IgM-only CD27+ subset in AID-deficient patients thus appears to be correlated with the presence of germinal centers. It may represent a stage prior to switching during normal B cell development, accumulating in AID-deficient patients as a consequence of their defect in the molecular mechanism of isotype switch. The absence of somatic mutations was confirmed for both CD27+ B cell subsets in these patients (Table 2 and data not shown).

Figure 3. Presence of an IgM+IgD+CD27+ subset in hyper-IgM patients.

Patients L.D. and C.A. (patient one) have been reported previously (20,21). Control is a eleven-year-old child, age-matched with patient C.A. Since IgD+CD27+cells co-express IgM, the IgM+IgD+CD27+ subset is analyzed after IgD, CD27 and CD19 labeling of purified B cells. IgD and CD27 expression is shown after gating on CD19-positive cells. Percentages of cells in the naive and the two CD27+ quadrants are indicated.

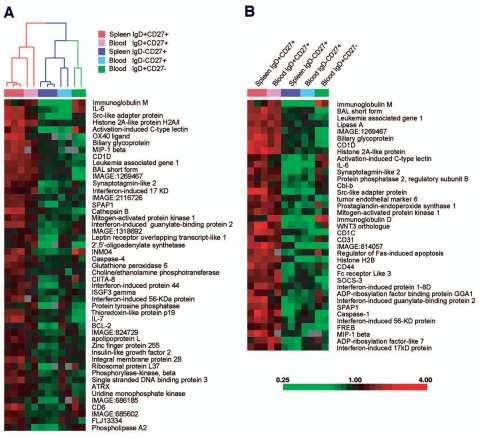

Blood and splenic IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells share a common gene expression profile

In order to compare more extensively splenic and blood IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells with splenic and peripheral naive and switched subsets, we used Lymphochip DNA microarrays [17] to profile gene expression of these different subsets after purification by cell sorting. We first searched for genes that were expressed at least two-fold more highly in splenic IgD+CD27+ populations than in splenic IgD− CD27+ populations with high statistical significance (p<0.005; t-test). Forty-nine genes satisfied these criteria (Fig. 4A). We used the hierarchical clustering algorithm to organize the various B cell populations based on expression of these genes, and found that the blood IgD+CD27+ cells clustered with the splenic IgD+CD27+ in one arm of the dendrogram (Fig. 4A). In the other arm of the dendrogram were the splenic and blood IgD−CD27+ memory B cells and the blood naive B cells. It is important to emphasize that this set of genes was not deliberately selected as being expressed similarly between blood and splenic IgM+IgD+CD27+ cells. Therefore, the fact that the hierarchical clustering algorithm grouped these two B cell populations together demonstrates that blood IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells are more related to splenic marginal zone B cells than they are to naive or switched memory B cells. We then searched for genes that were expressed at least two-fold more highly in the splenic and peripheral IgD+CD27+ populations than in the IgD−CD27+ populations with high statistical significance (p < 0.005). Figure 4B shows the expression levels in the various B cell populations of 37 genes that satisfied these selection criteria. This set includes genes that encode the surface markers previously described and associated with marginal zone B cells (IgM, IgD, CD1) as well as a number of genes, like IL-6, not previously associated with this B cell subpopulation.

Figure 4. A common gene expression signature for IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells from blood and spleen.

Each column represents microarray data from a sample of the indicated cell subtype and each row represents the expression of a single gene. The spleen IgD+CD27+ and IgD−CD27+ populations are obtained from two separate donors, with one of the two samples prepared in duplicate. Red squares indicate increased expression and green squares indicate decreased expression relative to the median expression of the gene according to the color bar shown. Gray squares indicate missing or excluded data, a) The array dendrogram obtained by clustering the 49 genes that differentiated (p<0.005, two-fold higher expression) the splenic IgD+CD27+ samples from the splenic IgD−CD27+ samples. The red branches indicate the co-clustering of the blood IgD+CD27+ samples with the splenic IgD+CD27+ samples and the blue branches indicate the co-clustering of the blood IgD−CD27+ samples with their respective splenic IgD−CD27+ samples, b) The 37 genes that achieved statistical significance with a two-fold higher mean expression when comparing the IgD+CD27+ cell populations with the memory IgD−CD27+ cell populations.

Identical clones are shared by blood and splenic IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cell subsets

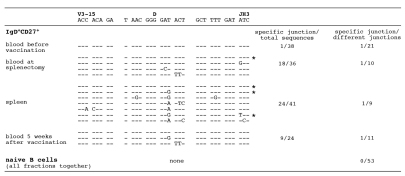

To establish a functional link between the splenic and circulating IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells, we studied the evolution of specific VDJ rearrangements by CDR3 spectratyping[24] during the course of a T-independent immunization. A 9-year old child with a diagnosis of hereditary microspherocytosis, a non-immunological disease, was vaccinated against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis one week before undergoing a splenectomy. Blood was collected one week before vaccination, 8 days after vaccination at the time of surgery together with the splenic sample, and 5 weeks after vaccination. Rearranged V3-15 genes have been shown to be mobilized in response to such an immunization [11] and were therefore followed at these different stages. A particular CDR3 length, whose representation was increased in the IgM+IgD+CD27+ blood sample was chosen for further study (Supplementary figure 1). A specific V3-15 sequence displaying a unique VDJ join emerged 8 days after vaccination in the splenic and circulating IgM+IgD+CD27+ population, where it was found recurrently in different amplifications and contributed as much as half of the sequences amplified (Fig. 5). This clone was found once among 38 sequences in the IgM+IgD+CD27+ subset before vaccination and already harbored 8 mutations in the complete V3-15 sequence at that stage (Fig. 5 and data not shown). In contrast, this particular VDJ join could not be found in the naive B cell compartment, whether from blood or spleen, at any stage of the experiment (no case among 53 different junctions). This clone still represented one-third of the amplified sequences in the IgM+IgD+CD27+ cells of the blood 5 weeks after vaccination. This specific CDR3 is present in 9 variant mutated forms after vaccination, with one recurrent amino acid change contributed by two different mutations (GAT to GAA or GAG, leading to the same Asp to Glu replacement) and occurring in the context of various other base substitutions. Some of these mutations are shared by several samples (e.g. a GAT to GAG change shared by the spleen and the blood one-month after splenectomy, or an ACT to TTT double change found in the spleen and the blood at the same time)(Fig. 5). From this analysis, we can conclude that a B cell clone detectable in the blood IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cell subset and harboring an already mutated V3-15 gene was mobilized and expanded in the splenic marginal zone and in the blood one week after immunization with a T independent vaccination. The same clone was still present, but at a lower degree, five weeks later in the same blood subset.

Figure 5. IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells from blood and spleen share B cell clones with an identical V3-15 CDR3 during a T-independent response.

Amplification of V3-15-Cμ mRNA sequences was performed from naive and IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells of a 9-year old child undergoing splenectomy and immunized against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis (plain polysaccharidic vaccines). The following samples were analyzed: blood before immunization, blood at the time of splenectomy (i.e. 8 days after immunization), spleen, blood 5 weeks after immunization. The first V3-15-specific PCR products were further amplified with V3-15-specific FR3 and C7μ primers, and the resulting products fractionated by denaturing gel electrophoresis. A specific CDR3 size was excised from the gel after silver staining and reamplified with the same FR3 and Cμ primers, and sequences determined after cloning. Several PCR amplifications were performed from two independent cDNAs for each cell sample. The recurrent CDR3s encompassing the V3-15 and JH3 junctions observed in the various IgM+IgD+CD27+ fractions are shown, with the most frequently occurring sequence taken as reference (CDR3 is defined as amino acids included between the conserved Cys residue of FR3 and Trp residue of JH segments). The asterisk (*) marks clones found repeatedly in independent PCR amplifications.

Normal and asplenic children below 2 years possess a diversified IgM+IgD+CD27+ blood B cell subset

To ask whether hypermutation occurs in the absence of antigenic stimulation is not a feasible task in humans. Children below 2 years do not mount proper antibody responses against T-independent antigens such as bacteria carrying polysaccharidic capsids like Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae. This may be due to the immaturity of the SMZ that is not yet functional because it lacks the appropriate macrophages and/or the retention of the MZ B cells [25]. We therefore focused our study on young healthy children below two years of age and also on young and older patients with congenital asplenia.

We have previously shown that the IgM+IgD+CD27+ subset appears gradually with age in the circulation of the normal population, starting at around 1% at birth (cord blood samples) to reach 7 to 19 % at two years and a mean of 20% in adults, with large individual variations (7 to 55%) [26]. A parallel increase with age was observed for Ig mutation frequencies with values close to background in cord blood, values that reach already 2% at one year and 3–4% in adults [26]. For two children around 2 years of age, the proportion of IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells in the spleen (20%) and the mutation frequency (about 2%) were similar to values found in older individuals (Table 1 and data not shown).

For asplenia syndromes, we restricted our study to patients diagnosed by several criteria, including the presence of Howell-Jolly bodies, the absence of spleen by echography and in some cases by scintigraphy. Some of these patients suffered from frequent pneumococcal infections and in two cases, death of a brother or sister by bacterial sepsis was reported (a detailed description is given in Table 3). Peripheral B cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for ten patients ranging from 4 months to 71 years of age and Ig gene mutation frequency for four of them (Fig. 6C–E). All children with congenital asplenia displayed a normal peripheral CD27+ B cell compartment with a normal IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cell subset. Moreover, in the four cases analyzed (14,18, 23 and 50 months), these IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells were heavily mutated with a frequency of 2.2 to 3.7 % (Fig. 6D). For adult asplenic patients, both IgM+IgD+ and isotype-switched CD27+ subsets were on average reduced as compared to age-matched controls (Fig. 6C and Table 3). Similarly, a reduction of IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells has been described recently for an adult aplenic patient [15]. In the latter study however, a more drastic reduction in both CD27+ memory subsets was reported for young children.

Figure 6. Development and diversification of IgM+IgD+CD27+ peripheral B cells from normal and asplenic children.

A, C. Percentage of IgM+IgD+CD27+ peripheral B cells from normal (A) and asplenic children (C) below five years.

B, D. Mutation frequency of rearranged V3-23 genes from IgM+IgD+CD27+ peripheral B cells of normal (B) and asplenic children (D). Each bar represents the mutation frequency of one individual and the values marked above represent the mutation range over the 288 bp V3-23 sequence analyzed. Normal adult values are pooled from five individuals.

E. IgD/CD27 staining profiles of peripheral CD19+ lymphocytes of asplenic individuals from 14 months to 71 years. Percentages of cells in each CD27+ quadrants are indicated. A complete description of asplenic patients is given in Supplementary Table.

DISCUSSION

We have observed previously that the circulating and splenic CD27+ B cells, which represent approximately 40% of the peripheral and splenic B cell pool in normal individuals, are divided into isotype-switched and IgM+IgD+ B cells[26]. A similar observation was made for peripheral B cells in a recent report by Kruetzman et al. [15]. IgM-only CD27+ B cells appear to represent a minor subset (around 1% on average), which is only observed as a distinct subpopulation in some young children and in some pathological cases (AID-deficiency and specific auto-immune syndromes, unpublished data). Both of these studies performed on a large cohort of normal individuals appear to contrast with the original description of memory B cells by Klein et al. [1], who described a subpopulation of 10% IgM-only CD27+ B cells in the blood of three normal subjects. Further analysis should help to clarify this issue.

The IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells, either in blood or in spleen, display the phenotype of splenic marginal zone B cells, being for both organs IgMhiIgDloCD27+CD21+CD23−CD1chi. Histological staining of human spleen with CD20, CD27, IgD and CD1c confirmed that the IgD and CD27 markers indeed identify marginal zone B cells in humans [10].

When the different splenic and blood B cell subpopulations are analyzed by gene expression profiling, the blood and splenic IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells appear closer to each other than to any other subset. Some genes seem specifically expressed by these cells such as IL6, which is also induced after activation of naive B cells, the CD31 receptor that is involved in trans-endothelial cell migration and the CD1 surface receptor known to be involved in presentation of lipid antigens. Altogether, these two approaches, using cell surface markers and gene expression profiles, identified the blood IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cell subset as the circulating counterpart of the splenic marginal zone B cell compartment. In contrast to rodents [27], human SMZ B cells thus appear to recirculate, accounting for 10–30% of the B cell pool in blood and in spleen and harboring mutated Ig genes.

Analysis of a CD40-deficient child showed, as for CD40L-deficient patients, an IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cell subpopulation as the only “memory” subset. These cells carried a mutated Ig receptor with an average of 11 mutations per sequence. Such a high mutation frequency with more than 95% of sequences carrying somatic mutations was previously observed in CD40L-deficient children. It is clear however that this CD27+ subset is frequently reduced in HIGM children compared to age-matched controls, as the absence of CD40-CD40L interaction may disturb the cytokine network and alter the development of these cells as previously discussed [14]. This study therefore argues in favor of our previous proposition that circulating IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells belong to a separate B cell subpopulation which develops and mutates its Ig receptor outside a germinal center-dependent cognate T-B interaction.

Immunization with a T-independent vaccine followed by splenectomy showed that a specific clone using the V3-15 gene, as followed by its VDJ signature, was strongly and specifically expanded in the splenic and blood marginal zone subsets one week after immunization. The same clone could be found 4 weeks after immunization in the blood IgM+IgD+CD27+ cells, although at a lower frequency. These results are consistent with previous reports showing that antibody responses to these bacterial capsular polysaccharides are oligoclonal and mobilize the V3-15 gene [28]. Moreover the potent amplification of the V3-15 clone in the splenic IgM+IgD+CD27+ population suggests strongly that this clone has been stimulated to expand in the splenic marginal zone by the T-independent vaccine. As previously shown for a similar immunization, responding clones remains for a few weeks in the general circulation[28]. This V3-15 clone carried 8 mutations on its VH gene prior to vaccination. The results showing selection of some additional mutations on this gene suggest that this process could be reactivated in the spleen during the week following immunization [29]. They moreover unambiguously establish that IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells do recirculate between blood and splenic marginal zone in humans.

We have previously reported that the circulating IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cell population was, surprisingly, already well developed and mutated at one year of age in normal children [26], a stage at which the splenic marginal zone is not yet functional. In young children before 2 years, the response to TI antigens has been reported to be defective with a high incidence of infections caused by encapsulated bacteria [25]. Our results on young children are thus intriguing since they indicate that circulating IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells can develop and diversify their Ig receptors during ontogeny before a functional splenic marginal zone is matured. It is then tempting to propose that these cells could at this early stage have diversified their Ig receptors by hypermutation as a developmental program rather than following an immune response. Such a possibility has been mentioned in the original work describing these cells [1]. A program of diversification involving the hypermutation process to generate a pre-immune repertoire has already been reported for species such as sheep and rabbits [30], and humans could have conserved this strategy for one arm of their B cell system. Hypermutation as a mean to enlarge the pre-immune repertoire has been recently proposed for the mouse as well, but such a process seems to occur only in specific models harboring a highly restricted V gene usage [31]. It s clear that in all these models, a window of tolerance is likely to accompagny this pre-diversification step.

When looking at adult asplenic patients, we could detect a clear diminution of CD27+ B cells, including both the isotype-switched and the IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells, in accordance with Kruetzman et al.[15], and suggesting, as proposed by these authors, that the spleen could be the main source of these cells. However and surprisingly, the younger asplenic patients we analyzed did not show, as opposed to their results, any significant alteration in the number and mutational status of their IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells, implying that there may be large variations among these younger patients. The presence of these cells in several asplenic children would nevertheless suggest that other sites, like for example marginal zone-like regions of Peyer’s patches and tonsils [7] might substitute for the developmental function of the spleen, without being able to sustain a similar B cell production in adulthood neither to replace the role that the splenic environment plays in supporting T-independent responses.

Immune responses to TI antigens are known to generate neither a memory response nor a maturation of affinity and to give protection for six months approximately [32]. Effectively SMZ B cells can switch after activation and differentiate rapidly into plasma cells [33] that can probably remain in the organism for a few months. In such sense, in spite of their previous characterization on the basis of their mutated Ig genes, IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells would represent an immediate line of defense with none of the functional characteristics of memory. It has in fact been proposed that natural antibodies, which are essential for the immediate protection they provide against an infection, are constantly secreted by bystander stimulation of memory IgM and switched B cells [34]. Most of the natural mutated IgM antibodies present in human serum are thus likely produced, as previously proposed [15], by circulating and splenic IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells.

In conclusion in this work and the previous ones by our group [14] and by Kruetzman et al. [15], a new scheme of human B cell development seems to emerge in which the IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells in charge of T-independent responses follow a separate pathway of differentiation as compared to the classical B cells involved in T-dependent responses. We would also like to suggest that Ig gene hypermutation may play a double task in the human B cell repertoire, by allowing the improvement of low-affinity antibodies during classical T-dependent immune responses, but also by generating a protective and diversified marginal zone B cell repertoire that can be mobilized in rapid T-independent anti-bacterial responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (Equipe Labellisée), the A.C.I. “Microbiologie, maladies infectieuses et parasitaires” of the Ministère de la Recherche, the 4th PCRD of European Community (contract QLGI-CT-2001 “IMPAD” to J.-C. W. and A. P.) and the Fondation Princesse Grace. S.W. has been supported during part of this work by the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer and the Société de Secours des Amis des Sciences and M.C. B. by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinshaft.

We thank Ninon Lesage and Kun Yang for their contribution. We thank also Jérome Mégret and Frédéric Delbos for cell sorting. We thank Dr B. Moody for the gift of the anti-CD 1c antibody, Dr V. Minard for the clinical follow-up of asplenic patients and Pr C. Rose for providing blood sample. We thank Dr. A. Alcais for the statistical analysis. Many thanks to Capucine Picard and Claire Fieschi for their unvaluable support. The authors are grateful to Benedita Rocha for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Klein U, Rajewsky K, Kuppers R. Human immunoglobulin (Ig)M+IgD+ peripheral blood B cells expressing the CD27 cell surface antigen carry somatically mutated variable region genes: CD27 as a general marker for somatically mutated (memory) B cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1679–1689. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein U, Kuppers R, Rajewsky K. Evidence for a large compartment of IgM-expressing memory B cells in humans. Blood. 1997;89:1288–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Es JH, Meyling FH, Logtenberg T. High frequency of somatically mutated IgM molecules in the human adult blood B cell repertoire. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2761–2764. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paramithiotis E, Cooper MD. Memory B lymphocytes migrate to bone marrow in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:208–212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumararatne DS, Bazin H, MacLennan IC. Marginal zones: the major B cell compartment of rat spleens. Eur J Immunol. 1981;11:858–864. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830111103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin F, Kearney JF. Marginal-zone B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nri799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spencer J, Perry ME, Dunn-Walters DK. Human marginal-zone B cells. Immunol Today. 1998;19:421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunn-Walters DK, Isaacson PG, Spencer J. Analysis of mutations in immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region genes of microdissected marginal zone (MGZ) B cells suggests that the MGZ of human spleen is a reservoir of memory B cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:559–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tierens A, Delabie J, Michiels L, Vandenberghe P, De Wolf-Peeters C. Marginal-zone B cells in the human lymph node and spleen show somatic hypermutations and display clonal expansion. Blood. 1999;93:226–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tangye SG, Liu YJ, Aversa G, Phillips JH, de Vries JE. Identification of functional human splenic memory B cells by expression of CD148 and CD27. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1691–1703. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas AH, Moulton KD, Tang VR, Reason DC. Combinatorial library cloning of human antibodies to Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides: variable region primary structures and evidence for somatic mutation of Fab fragments specific for capsular serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F. Infect Immun. 2001;69:853–864. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.853-864.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notarangelo LD, Duse M, Ugazio AG. Immunodeficiency with hyper-IgM (HIM) Immunodefic Rev. 1992;3:101–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agematsu K, Nagumo H, Shinozaki K, et al. Absence of IgD-CD27(+) memory B cell population in X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:853–860. doi: 10.1172/JCI3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weller S, Faili A, Garcia C, et al. CD40-CD40L independent Ig gene hypermutation suggests a second B cell diversification pathway in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1166–1170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruetzmann S, Rosado MM, Weber H, et al. Human immunoglobulin M memory B cells controlling Streptococcus pneumoniae infections are generated in the spleen. J Exp Med. 2003;197:939–945. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steiniger B, Barth P, Hellinger A. The perifollicular and marginal zones of the human splenic white pulp: do fibroblasts guide lymphocyte immigration? Am J Pathol. 2001;159:501–512. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61722-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–11. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timens W, Boes A, Poppema S. Human marginal zone B cells are not an activated B cell subset: strong expression of CD21 as a putative mediator for rapid B cell activation. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:2163–2166. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830191129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fairhurst RM, Wang CX, Sieling PA, Modlin RL, Braun J. CDI-restricted T cells and resistance to polysaccharide-encapsulated bacteria. Immunol Today. 1998;19:257–259. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrari S, Giliani S, Insalaco A, et al. Mutations of CD40 gene cause an autosomal recessive form of immunodeficiency with hyper IgM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12614–12619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221456898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, et al. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–63. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Revy P, Muto T, Levy Y, et al. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the Hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2) Cell. 2000;102:565–575. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minegishi Y, Lavoie A, Cunningham-Rundles C, et al. Mutations in activation-induced cytidine deaminase in patients with hyper IgM syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2000;97:203–210. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holtmeier W, Hennemann A, Caspary WF. IgA and IgM V(H) repertoires in human colon: evidence for clonally expanded B cells that are widely disseminated. Gastroenterology. 2000;19:1253–1266. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zandvoort A, Timens W. The dual function of the splenic marginal zone: essential for initiation of anti-TI-2 responses but also vital in the general first-line defense against blood-borne antigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:4–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weller S, Faili A, Aoufouchi S, Gueranger Q, Braun M, Reynaud CA, Weill JC. Hypermutation in human B cells in vivo and in vitro. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;987:158–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLennan IC, Chan E. The dynamic relationship between B-cell populations in adults. Immunol Today. 1993;14:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90321-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas AH, Reason DC. Polysaccharide vaccines as probes of antibody repertoires in man. Immunol Rev. 1999;171:89–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou J, Lottenbach KR, Barenkamp SJ, Lucas AH, Reason D-C. Recurrent variable region gene usage and somatic mutation in the human antibody response to the capsular polysaccharide of steptococcus pneumoniae type 23F. Inf and Immunity. 2002;7:4083–4091. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4083-4091.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynaud C-A, Weill J-C. Postrearrangement diversification processes in gut-associated lymphoid tissues. In: Vainio O, Imhof BA, editors. Current topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 212. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 1996. pp. 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao C, Jiang L, Melo-Jorge M, Puthenveetil M, Zhang X, Carroll MC, Imanishi-Kari T. T cell-independent somatic hypermutation in murine B cells with an immature phenotype. Immunity. 2004;20:133–144. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldblatt D, Borrow R, Miller E. Natural and vaccine-induced immunity and immunologic memory to Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C in young adults. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:397–400. doi: 10.1086/338474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliver AM, Martin F, Kearney JF. IgMhighCD21 high lymphocytes enriched in the splenic marginal zone generate effector cells more rapidly than the bulk of follicular B cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:7198–7207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199–2202. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy Y, Gupta N, Le Deist F, et al. Defect in IgV gene somatic hypermutation in common variable immuno-deficiency syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13135–13140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]