Abstract

An expanded substrate scope and in depth analysis of the reaction mechanism of the copper(II) carboxylate promoted intramolecular carboamination of unactivated alkenes is described. This method provides access to N-functionalized pyrrolidines and piperidines. Both aromatic and aliphatic γ- and δ-alkenyl N-arylsulfonamides undergo the oxidative cyclization reaction efficiently. N-Benzoyl-2-allylaniline also underwent the oxidative cyclization. The terminal olefin substrates examined were more reactive than those with internal olefins, and the latter terminated in elimination rather than carbon-carbon bond formation. The efficiency of the reaction was enhanced by the use of more organic soluble copper(II) carboxylate salts, copper(II) neodecanoate in particular. The reaction times were reduced by the use of microwave heating. High levels of diastereoselectivity were observed in the synthesis of 2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidines, wherein the cis substitution pattern predominates. The mechanism of the reaction is discussed in the context of the observed reactivity and in comparison to analogous reactions promoted by other reagents and conditions. Our evidence supports a mechanism wherein the N-C bond is formed via intramolecular syn aminocupration and the C-C bond is formed via intramolecular addition of a primary carbon radical to an aromatic ring.

Introduction

Nitrogen heterocycles make up a significant proportion of biologically active small organic molecules. Recently developed methods for the synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles by transition metal facilitated intramolecular amine additions onto unactivated alkenes have expanded the repertoire of tools available to the medicinal chemist.1–25 Methods that provide for concise build-up of functionality by installing two rings in a single operation may prove especially useful in the concise synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles for natural product synthesis and drug discovery endeavors.11, 14, 15, 26–32 Herein is reported an expansion of the substrate scope of the copper(II) promoted intramolecular carboamination of unactivated alkenes,11 a transformation that installs two new rings from acyclic N-substituted amines.

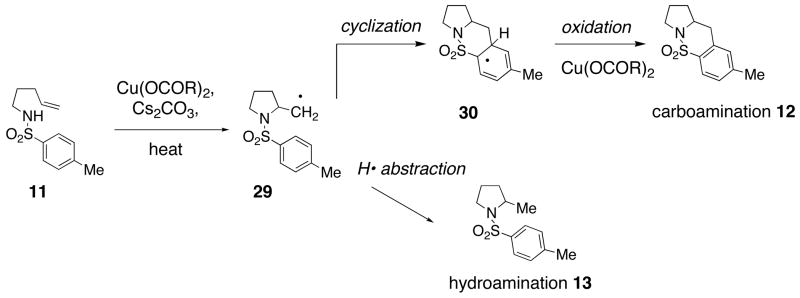

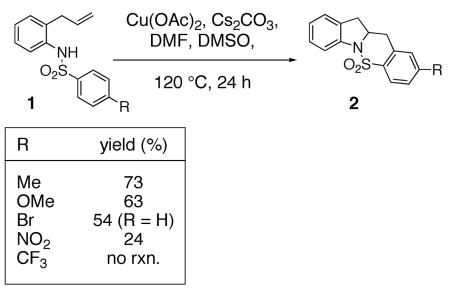

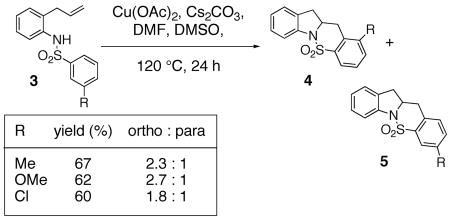

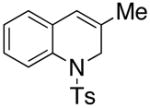

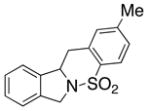

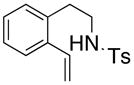

We recently reported that copper(II) acetate promotes the oxidative cyclization of N-arylsulfonyl-2-allylanilines 1 (Eqs. 1 and 2).11 In these reactions, aryl sulfonamides with electron donating groups proved most reactive: 4-methyl, methoxy, chloro and bromoaryl sulfonamides reacted efficiently albeit the bromide was removed under the reaction conditions (Eqs. 1 and 2). 4-Nitro and 4-trifluoromethyl arylsulfonamides displayed significantly lower reactivity (Eq. 1). (Similar electronic effects have been observed in Brönsted acid catalyzed intramolecular hydroamination reactions.33) Meta-Substituted aryl sulfonamides demonstrated a preference (ca. 2 : 1) for the ortho addition product over the para adduct (Eq. 2). This surprising ortho preference (the more sterically hindered site) indicated that C-C bond formation may occur via addition of a carbon radical to the aromatic ring [intermolecular additions of radicals to aromatics have shown a slight preference (ca. 2 : 1) for the ortho adduct].34, 35

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Results and Discussion

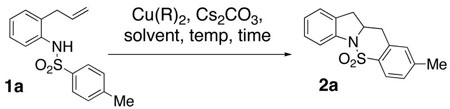

In order to further expand the utility of this method, several copper(II) carboxylate salts, solvents and reaction heating methods were examined. Our former optimized reaction conditions for the carboamination reaction of 1a (R = Me) required DMF or CH3CN solvent at 120 °C for 24 h (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). The need for polar solvents and additives (added DMSO increased the yield with some substrates) was attributed to the poor solubility of Cu(OAc)2 in organic solvents. We therefore examined the reaction further by using more polar solvents with Cu(OAc)2 and more organic soluble copper carboxylates with non-polar solvents, respectively. The reaction did proceed in both i-PrOH and t-amyl alcohol (Table 1, entries 4 and 5) although in the former case substantial amounts of another product was obtained (net aminoetherification, see supplementary material) while in the latter case a more efficient, albeit not optimal carboamination process occured. Several copper(II) carboxylates were also compared. We found that while the use of Cu(OAc)2 in toluene did promote oxidative cyclization (51% yield + remaining starting material, entry 6, Table 1), the more organic soluble copper(II) neodecanoate [Cu(ND)2] provided a more efficient reaction (71% yield, entry 11, Table 1). Copper(II) neodecanoate also provided a more efficient reaction with more entropically challenging substrates (Table 2, vide infra). Copper(II) pivalate and copper(II) 2-ethylhexanoate also provided efficient reaction in DMF (entries 8 and 9) and under these conditions are comparable to Cu(ND)2 and Cu(OAc)2. Based upon these examples, the relative steric demand of the carboxylate alkyl chain does not affect the reactivity of the carboxylate salt in these reactions.

Table 1.

Reaction Conditions: Carboxylate, Solvent, Temperature

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | solvent | temp, time | yield (%)d |

| 1 | Oac | DMF | 120 °C,b 24 h | 69 |

| 2 | Oac | CH3CN | 120 °C,b 24 h | 73 |

| 3 | Oac | i-PrOH | 120 °C,b 24 h | 16e |

| 4 | OAc | t-amyl-OH | 120 °C,b 24 h | 33 |

| 5 | OAc | EtOAc | 120 °C,b 24 h | 24e |

| 6 | OAc | toluene | 120 °C,b 24 h | 51e |

| 7 | OAc | DMA | 120 °C,b 24 h | 37 |

| 8 | OPiv | DMF | 120 °C,b 24 h | 69 |

| 9 | EH | DMF | 120 °C,b 24 h | 64 |

| 10 | ND | DMF | 120 °C,b 24 h | 69 |

| 11 | ND | toluene | 120 °C,b 24 h | 71 |

| 12 | ND | DMF | 120 °C,b 0.5 h | 29e |

| 13 | ND | DMF | 120 °C,c 0.5 h | 27e |

| 14 | ND | DMF | 160 °C,b 0.5 h | 63 |

| 15 | ND | DMF | 160 °C,c 0.5 h | 64 |

All reactions were run with 3 equiv copper(II) carboxylate, 1 equiv Cs2CO3 at 0.1 M 1a concentration.

Oil bath heating, pressure tube.

Microwave heating.

Amount isolated after flash chromatography on SiO2.

Remainder of the material is starting 1a. In entry 3 another cyclization product (net aminoetherification, incorporation of i-PrOH in the product) was also formed in 21% yield (see supplementary material). Ac = COCH3, Piv = COC(CH3)3, neodecanoate (ND) = OCO(CH2)5C(CH3)3, ethylhexanoate (EH) = OCOCH(C2H5)C4H9

Table 2.

Expanded Sulfonamide Substrate Scopea

| entry | substrate | product(s)b | temp; time | yield (%)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

120 °C; 24 h | 49 exo (9)

46 endo (10) |

| 2 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

160 °C; 72 h | 23 CA (12)d |

| 3 | 160 °C; 72 h | 59 CA (12) + 21 HA (13) | |||

| 4 |

14 |

15 |

160 °C; 72 h | 87d | |

| 5 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

210 °C, 72 h | 56 CA (17, trans : cis = 1 : 1), 16 HA (18, trans : cis = 1 : 1) |

| 6 | 210 °C; μW, 3 h | 52 CA (17, trans : cis = 1 : 1), 20 HA (18, trans : cis = 1 : 1) | |||

| 7 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

180 °C, 72 h | 65 CA (20, trans : cis = 3 : 1)

33 HA (21, trans : cis = 3 : 1) |

| 8 |

22 |

23 |

200 °C; 72 h | 48 | |

| 9 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

200 °C; 72 h | 53 CA (25 only) |

| 10 | 210 °C, μW, 3 h | 55 CA (25) + 14 HA (26) | |||

| 11 |

27 |

28 |

200 °C; 72 h | 43 | |

Reaction conditions: 3 equiv Cu(ND)2, 1 equiv Cs2CO3, DMF (0.08–0.1 M), temp, time.

Selectivity determined by analysis of the crude 1H NMR spectrum, and by amount of the isolated adducts.

Yield refers to amount of product isolated by chromatography on silica gel.

Reaction run with Cu(OAc)2 instead of Cu(ND)2. CA = carboamination product, HA = hydroamination product, ND = neodecanoate.

Increasing the reaction temperature decreased the time required for product formation. As judged by the crude 1H NMR spectra, at 160 °C the reaction was complete after 0.5 h (63% isolated yield of 2) while only a 29% yield of 2 was obtained at 120 °C for 0.5 h [using Cu(ND)2 in DMF], the remaining material being unreacted starting material (compare entries 12 and 14). At these reaction scales with substrate 1a (ca. 30 mg 1a, 1 mL solvent) we did not find notable difference in reactivity between microwave and oil bath heating (compare entry 12 to 13 and entry 14 to 15). This may be due in part to the fact that both reactions are run in sealed tubes, thus, in both cases, the reaction solutions are subject to superheating and also the transfer of heat due to surface area heating is not a significant problem with small scale reactions.36

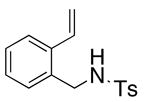

Effect of the Nitrogen Substituent

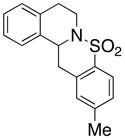

Although arylsulfonamides are superior substrates for this reaction (lower reaction temperatures required, higher yield), the N-benzoyl-2-allylaniline 6 also provides the oxidative cyclization product 7 (Eq. 3, ND = neodecanoate). Formation of fused carbon/nitrogen ring systems allows entry into a broader range of nitrogen heterocycles and further examination of the copper carboxylate promoted reactions with such substrates is warranted.

|

(3) |

Effect of Chain Length and Substitution

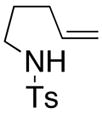

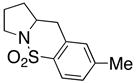

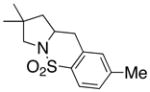

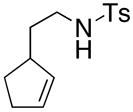

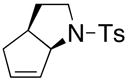

In an effort to expand the substrate scope of the copper(II) carboxylate promoted carboamination reaction of sulfonamides as well as gain more insight into the reaction mechanism, the oxidative cyclizations of a number of substrates were explored, including arylsulfonamides derived from aliphatic amines, substrates with different olefin substitution patterns and substrates containing chiral centers (Table 2). Both microwave and oil bath heating methods were used. Both five-membered ring pyrrolidines and six-membered ring piperidines can be formed through this oxidative cyclization protocol. All of the substrates examined in this reaction give exclusively the exo cylization adduct except for the 1,1-disubstituted olefin 8, which gave a ca. 1 : 1 mixture of the exo carboamination adduct 9 and the endo oxidative amination adduct 10 (Table 2, entry 1).

Sulfonamides 11, 14, 16 and 19, derived from primary aliphatic amines (entries 2–7), undergo cyclization efficiently although the gem-dimethyl substituted substrate 14 demonstrated the highest reactivity.37 The more organic soluble Cu(ND)2 had a significant effect on the reaction yields with less reactive substrates (compare entries 2 and 3, Table 2). The formation of hydroamination minor products was also observed with some substrates and the carboamination to hydroamination ratio is presumably a function of the relative rates of radical addition to the aromatic ring vs hydrogen atom abstraction from the reaction medium (vide infra). Reaction of the 2-phenyl-pent-4-enyl sulfonamide 16 produced 1 : 1 diastereomeric mixtures of carboamination and hydroamination products, 17 and 18, respectively (entries 5 and 6, ratio of 17 : 18 = 3.5 : 1 in oil bath at 210 °C). In the case of substrate 19, with a methylcyclohexyl group at the allylic position, a 3 : 1 mixture of 2,3-trans : 2,3-cis diastereomers of carboamination and also 3 : 1 2,3-trans : 2,3-cis hydroamination adducts, 20 and 21, were formed (ratio of carboamination : hydroamination = 2 : 1). Cyclization reactions of substrates with allylic substitution under several other reaction conditions also favor the formation of the anti adduct, presumably due to reaction via a chair-like transition state which favors placement of the allylic alkyl substituent in a pseudo equatorial position.13, 20 The need for high temperature in the copper(II) carboxylate promoted cyclization may account for the modest level of asymmetric induction observed.

The carboamination adducts derived from styrenyl substrates 22 and 27 were obtained in modest yield upon heating at 200–210 °C (entries 8 and 11). These substrates are challenging due to the ground state resonance stabilization that is lost in the cyclization transition state. Few intramolecular carboamination protocols have been reported with styrenyl substrates.28 Formation of six-membered rings is also possible via the copper(II) promoted carboamination protocol (cf 24 and 27, entries 9–11, Table 2).

The products formed in these oxidative cyclization reactions are consistent with a mechanism that involves formation of a radical intermediate (e.g., 29) that may either perform intramolecular addition onto the neighboring aromatic ring or abstraction of a proton from the reaction medium (Scheme 1). In the case of endo cyclization adduct 10, the secondary radical undergoes Cu(II) facilitated elimination to form an alkene.38, 39

Scheme 1.

Mechanism for Formation of the Carboamination and Hydroamination Adducts

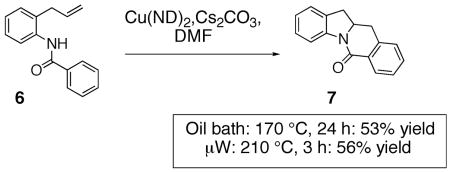

The mechanism was further probed using the carboamination reaction of deuteroalkene 14-D (Eq. 4). The partial conversion of 14-D provides a 1 : 1 mixture of diastereomers 15-D, indicating the presence of an sp2 hybridized carbon intermediate, likely a primary radical. The remaining deuteroalkene was recovered with complete retention of stereochemistry, indicating that the carbon radical intermediate does not revert back to the alkene.

|

(4) |

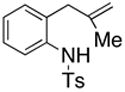

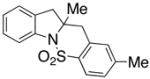

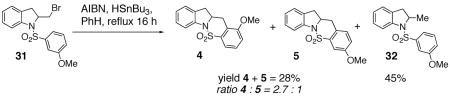

When an unambiguous primary radical was generated from the primary bromide 31 (AIBN, HSnBu3, PhH, reflux), a mixture of carboamination adducts 4 and 5 (ortho : para = 2.7 : 1) and hydroamination adduct 32 was obtained (Eq. 5). The fact that the carboamination products were obtained in the same ortho : para ratio ( 2.7 : 1) as observed in the copper(II) promoted reaction (see Eq 2) is compelling evidence that a similar intermediate, a primary carbon radical, is involved in the C-C bond formation. No ipso (1,5-addition) substitution of the radical onto the aromatic ring was observed. Mixtures of ipso (1,5) addition products and direct (1,6) addition products along with the direct reduction products have previously been observed in the intramolecular radical reactions of N-arylsulfonyl-2-halomethyl piperidines (AIBN, HSnBu3, PhH, reflux), and in many instances, the ipso product predominates.40–44 It has previously been observed, however, that the propensity for direct addition versus ipso substitution in the intramolecular addition reactions of carbon radicals to aromatic rings is highly dependent on the structure of the substrate.42, 44, 45

|

(5) |

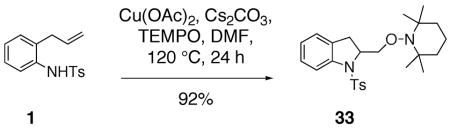

In an additional experiment, we have trapped the copper(II) carboxylate promoted carboamination reaction intermediate derived from sulfonamide 1 with TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl), a classical carbon radical trap (Eq. 6).46 No reaction occurred under the same conditions but in the absence of Cu(OAc)2.

|

(6) |

It should be noted that carbon radicals do react rapidly with copper(II) salts to form organocopper(III) intermediates.38 This process might be reversible for primary carbon radicals under our reaction conditions. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that some of the reactions discussed above might take place via such an organocopper species, we believe the carbon radical mechanism is the simplest explanation and most consistent with the observed results (vide supra, Eqs. 5 and 6). Previously, organocopper(III) species have been shown to undergo oxidative elimination or reductive elimination reactions.38

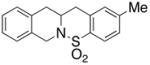

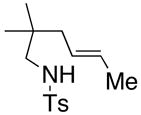

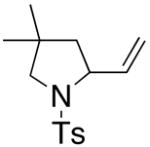

Substrates with internal disubstituted olefins require higher temperature conditions in the copper(II) carboxylate promoted oxidative cyclization than their terminal olefin counterparts (Table 3). The reactions are also less efficient and the cyclization cascade concludes in elimination rather than radical addition to the aromatic ring of the sulfonamide (e.g. compare entry 4, Table 2 to entries 2 and 3, Table 3).

Table 3.

1,2-Disubstituted (Internal) Olefin Substrates

| entry | substrate | product | temp, time, Cu(R)2 | yield (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a |

34 |

35 |

200 °C, 78 h, Cu(ND)2 | 35 |

| 2a,b |

36 |

37 |

160 °C, 72 h, Cu(OAc)2 | no rxn. |

| 3a,b | 160 °C, 72 h, Cu(ND)2 | 31 |

Remainder of the mass was recovered starting material.

A 5:1 E:Z mixture of olefin isomers of 36 was used.

Isolated yield. ND = neodecanoate.

The reactivity pattern of the internal olefin substrates indicates that 1) the rate of the initial nitrogen addition to the alkene is retarded by substitution on the terminal carbon and 2) oxidation of the resulting carbon radical to the olefin is faster than addition of the radical to the aromatic ring in cases when the carbon radical is secondary rather than primary (Scheme 2). Copper(II) promoted oxidative elimination reactions of carbon radicals have been previously invoked by Kochi; the elimination is not thought to occur via a carbocation intermediate unless a stable carbocation can be formed.47

Scheme 2.

Mechanism of Oxidative Cyclization of Substrates with Internal Olefins

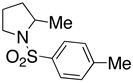

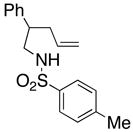

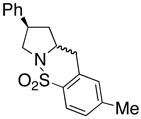

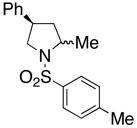

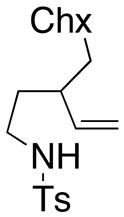

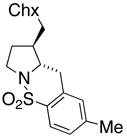

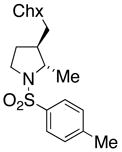

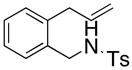

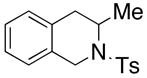

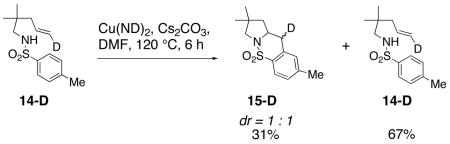

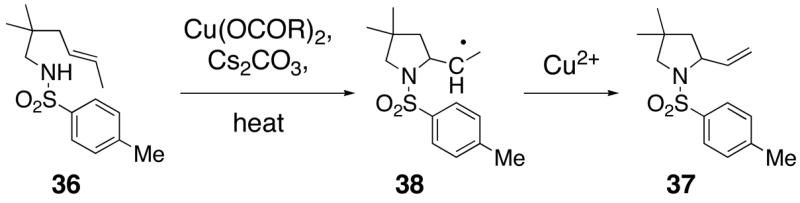

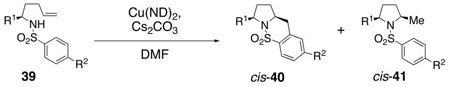

To aid in our mechanism investigation as well as further explore the scope of the carboamination reaction, we examined the oxidative cyclization of several α-substituted γ–alkenyl sulfonamides 39 for the synthesis of 2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidines (Table 4).48 Sulfonamides 39 can be efficiently synthesized in enantiomerically enriched form via ring opening addition of substituted tosylaziridines with allylmagnesium bromide.49 We found that cis 2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidines 40 can be formed with very high diastereoselectivity (>20 : 1) and in 31 – 51% yield in the copper(II) promoted oxidative cyclization of substrates 39 using either oil bath heating (sealed tube, 170 – 200 °C, 72 h) or microwave irradiation (210 °C, 3 h). Heating in an oil bath at 200 °C for 3 h gave only slightly lower conversion (entry 3). The net hydroamination adducts 41 are formed in these reactions as well (15–28%) and are formed with high 2,5-cis selectivity (>20 : 1) in all cases examined. The products emerge as ca. 2 : 1 mixtures of carboamination and hydroamination adducts, 40 and 41, respectively. A series of high boiling solvents [toluene, trifluorotoluene, tert-butyltoluene, N,N-dimethyl acetamide (DMA), 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (DMI) and 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP)] and different reaction concentrations (0.01 M and 0.5 M in DMF, reactions in Table 4 were run at 0.1 M substrate concentration) were tried with substrate 39b in an attempt to improve the carboamination product yield; unfortunately no improved conditions have yet been identified.

Table 4.

Diastereoseletive Formation of 2,5-Cis-Pyrrolidinesa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | method, temp, time | yield (%)c40 | yield (%)c41 |

| 1 | 39a, R1 = i-Pr, R2 = Me | oil bath, 190 °C, 72 h | 49 | 25 |

| 2 | 39a | 210 °C (μW), 3 h | 51 | 28 |

| 3 | 39a | oil bath, 200°C, 3 h | 40 | 19 |

| 4 | 39b, R1 = i-Pr, R2 = OMe | oil bath,190 °C, 72 h | 49 | 23 |

| 5 | 39b | 210 °C (μW), 3 h | 51 | 23 |

| 6 | 39b | oil bath, 190 °C, 72 hb | 33 | 24 |

| 7 | 39c. R1 = t-Bu, R2 = Me | oil bath, 170 °C, 72 h | 34 | 15 |

| 8 | 39c | 210 °C (μW), 3 h | 31 | 17 |

| 9 | 39d, R1 = Me, R2 = Me | oil bath, 200 °C, 72 h | 48 | 15 |

| 10 | 39d | 210 °C (μW), 3 h | 48 | 15 |

| 11 | 39e, R1 = i-PrCH2, R2 = Me | oil bath, 200 °C, 72 h | 49 | 20 |

| 12 | 39e | 210 °C (μW), 3 h | 49 | 19 |

| 13 | 39f, R1 = Bn, R2 = Me | oil bath, 200 °C, 72 h | 50 | 22 |

| 14 | 39f | 210 °C (μW), 3 h | 47 | 21 |

Sulfonamides 39 were dissolved in DMF (0.1 M) and treated with Cs2CO3 (1 equiv) and Cu(ND)2 (3 equiv) and were heated in the indicated manner at the indicated temperature and time.

Reaction run with NaH as base instead of Cs2CO3: Sulfamide 39b in DMF was treated with NaH (1.2 equiv) at 23 °C for 0.5 h, then Cu(ND)2 (1.2 equiv) in DMF was added, stirred 0.5 h, reaction was then heated at 190 °C for 72 h.

Yields refer to isolated products, diastereomeric ratios (>20 :1) were determined by analysis of the crude 1H NMR and by isolated yields. ND = neodecanoate.

When substrate 39b was treated first with NaH (1.2 equiv) and then with Cu(ND)2 (1.2 equiv) and subsequently heated, the reaction proceeded efficiently and gave similar results as when Cs2CO3 was used as base (compare entry 4 to entry 6). This indicates that a R2N-CuL intermediate can productively convert to the observed products (vide infra).

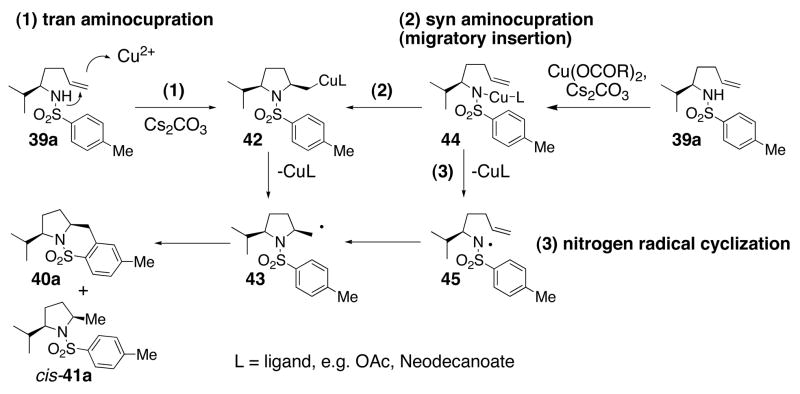

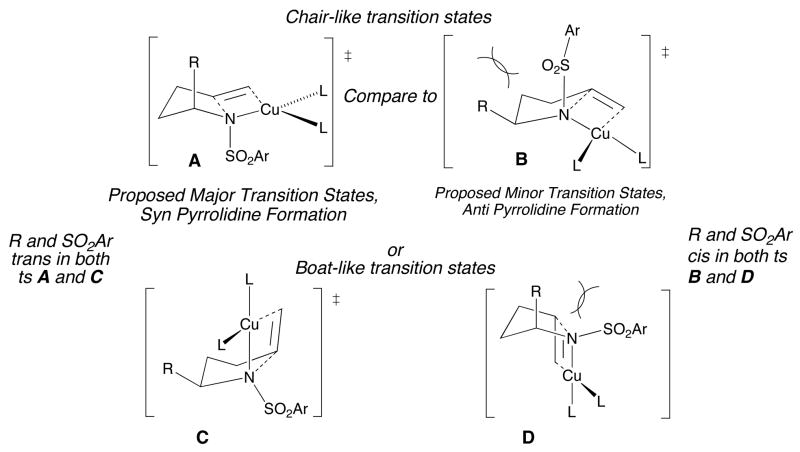

Analysis of the C-N Bond Formation Mechanism

The level and direction of diastereoselectivity in the 2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidine formation (Table 4) provides insight into the initial steps of the reaction mechanism. Three mechanistic scenarios that lead to the carbon radical intermediate 43 were considered (Scheme 3): (1) trans aminocupration, generating an unstable organocopper(II) species50, 51 that homolyzes to the carbon radical and Cu(I); (2) syn aminocupration, generating an unstable organocopper(II) species that homolyzes to the carbon radical and Cu(I); and (3) Cu(II) oxidation of the nitrogen to the nitrogen radical, followed by cyclization onto the olefin.

Scheme 3.

Possible Mechanisms for Cis-Pyrrolidine Formation

The predominance for the formation of the cis pyrrolidine diastereomer can provide insight into the reaction mechanism, especially when compared to the stereochemical trends observed when other reagents are used to promote pyrrolidine formation (vide infra).

Consideration of a Nitrogen Radical Pathway

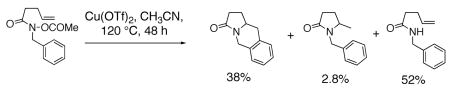

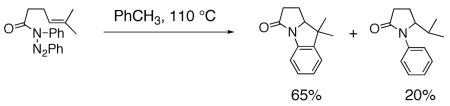

Pyrrolidines can be formed via cyclization of a nitrogen radical onto an olefin. Nitrogen radicals are usually formed via the homolytic cleavage of nitrogen-heteroatom bonds.23, 52, 53 For example, amine, amidyl and sulfamidyl radicals have been generated by treatment of: 1) xanthates (N-(O-ethyl thiocarbonylsulfanyl)amides) with lauroyl peroxide and heat,54 2) O-acyl hydroxamic acids with Bu3SnH and AIBN,55–57 or Cu(OTf)255 3) N-X (X = Cl, Br or 52, 58–65 and 4) N-acyltriazines with heat.66 Typical I) with Et3B, light or a transition metal catalyst, products of nitrogen radical cyclizations onto olefins include net carboamination, hydroamination and atom transfer (Eqs. 7 and 8).55, 66 Typically, terminal, internal and trisubstituted olefins provide amine and amidyl radical cyclization adducts.54, 63

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

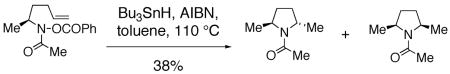

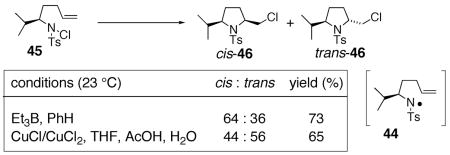

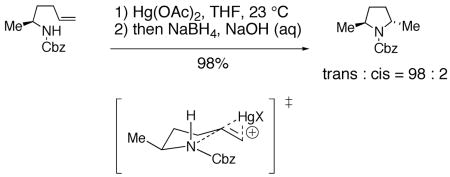

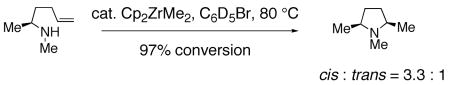

Clark has reported studies regarding the stereoselectivity of an amidyl radical cyclization where the substrate contained a stereocenter alpha to the amine.57 He found that the trans pyrrolidine product is favored (dr = 3.3 : 1) (Eq. 9, remainder of isolated material is uncyclized amide resulting from reduction of the N-O bond).57 Similar nitrogen radical reactions performed by Senboku and Tokuda involve homolysis of N-Cl substrates with AIBN and Bu3SnH and provide the 2,5-trans pyrrolidines as the major diastereomeric products.31, 32

|

(9) |

We further examined the stereoselectivity of a nitrogen radical reaction with a sulfonamide substrate. In our hands, of a number of methods attempted, the N-chlorosulfonamide 46 proved to be the most facile nitrogen radical precursor to synthesize. Hence, 46 was obtained uneventfully by treatment of the sulfonamide with NaH followed by N-chlorination with NCS.64 The N -chlorosulfonamide was subjected to two conditions reported to induce nitrogen radical cyclization reactions.59, 63, 64 Treatment of 46 with Et3B led to a 64 : 36 cis : trans mixture of chloromethylpyrrolidines 47 in 73% combined yield. When CuCl/CuCl2 was used as the radical initiator,59, 63, 67 a 44 : 56 cis : trans mixture of 47 was obtained. Both reactions are relatively unselective (dr = <2 : 1). Based upon these comparisons, it is unlikely that the highly diastereoselective copper(II) carboxylate promoted oxidative cyclization proceeds via a nitrogen radical. A mechanism involving a copper(I) or copper(II) coordinated nitrogen radical that promotes an organized addition to the alkene is also unlikely given the poor diastereoselectivity observed when CuCl/CuCl2 was used to promote the radical reaction of chlorosulfonamide 46 (Eq. 10).

|

(10) |

The oxidation of an amide or sulfonamide to the corresponding nitrogen radical by the agency of a copper salt is, in fact, unprecedented. (It should be noted, however, that the oxidation of aliphatic amines to nitriles, imines and aldehydes by copper salts have been reported, and these reactions have been postulated to occur through both radical and two electron processes.68–70) The oxidation of N-aryl amides with o-iodoxybenzoic acid (IBX) has, however, been reported, and the derived radicals undergo intramolecular cyclization onto variously substituted olefins. 71 Amides derived from aliphatic amines (non-aniline) are reported to be unreactive under these conditions.71 In our hands, subjection of N-arylsulfonyl-o-allylaniline 1a to these reaction conditions resulted in no reaction by crude 1H NMR analysis. In comparison to the IBX promoted reaction, it is also noteworthy that the arylsulfonamides derived from aliphatic amines are not significantly less reactive than arylsulfonamides derived from anilines in the copper(II) carboxylate promoted oxidative cyclization. This fact also argues against the formation of a nitrogen radical. In addition, the lower reactivity of the internal olefins [substrate 36 (Table 3) is less reactive than substrate 14 (Table 2)] indicates that steric hindrance at the terminal carbon impedes reactivity in the copper(II) carboxylate promoted reactions; by comparison, amidyl radical reactions are not impeded by substitution on the terminal alkene carbon (e.g. Eq. 8).72 Transition metal mediated additions of nitrogens to alkenes often suffer lower reactivity with internal alkenes.4, 73 We therefore conclude that the reactivity pattern observed in the copper(II) carboxylate promoted carboaminations is most consistent with a reaction mechanism that requires addition of [Cu] to the terminal alkene carbon.

Consideration of a Trans Aminocupration Mechanism

Intramolecular cyclization of amines onto olefins to form pyrrolidines can be promoted by metallic electrophiles such as mercury(II) and palladium as well as halogens and analogous electrophilic reagents.5, 74, 75 Elegant work by Harding and co-workers established that the trans-pyrrolidine is the kinetic product in the mercury(II) promoted cyclization of N-Cbz γ-unsaturated amine (Eq. 11).76 The proposed mechanism involves a chair-like tranisition state and a trans-aminomercuration of the olefin.77 As proposed by Harding, the substituents adopt psueduo equatorial positions on the chair-like transition state. No evidence has been proposed to refute this mechanism.

|

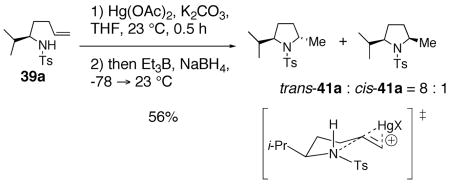

(11) |

When sulfonamide 39a was treated under modified78 mercuration-demercuration conditions, an 8 : 1 diastereomeric mixture favoring the trans hydroamination adduct trans-41a was obtained in 56% yield (Eq. 12). That the trans rather than cis adduct substantially predominates in this kinetically controlled reaction is a strong indication that the cis-selective copper(II) carboxylate oxidative cyclization reaction does not proceed by the same mechanism as the mercury(II) acetate reaction.

|

(12) |

Consideration of a Syn Aminocupration Mechanism

A mechanism for the copper(II) carboxylate promoted carboamination reaction that involves the intermediacy of a copper coordinated nitrogen (c.f. 44, Scheme 3) is supported by that fact that when such an intermediate is generated at room temperature by deprotonation of the sulfonamide 39a at 23 °C with NaH followed by treatment with 1 equiv of Cu(ND)2 at 23 °C for 0.5 h, upon heating, it forms the oxidative cyclization products cis-40b and cis-41b (Table 4, entry 6). That internal olefins (Table 3) are less reactive than terminal olefins in this reaction also supports the hypothesis that a copper-carbon bond is formed in the rate-determining step.

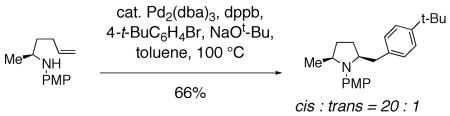

In addition, palladium catalyzed carboamination reactions that are thought to occur via syn aminopalladation favor formation of cis 2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidines.20, 21, 79 As reported by Wolfe and co-workers, N-Aryl, N-Boc and N-acyl substrates all provide the cis 2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidine as the major adduct (Eq. 13). Examination of the reaction of cyclic disubstituted olefins led Wolfe to conclude that a syn insertion of the nitrogen and palladium into the olefin is operative in these reactions.20 The nitrogen substitution pattern and cis pyrrolidine selectivity in this reaction is most analogous to the copper(II) promoted reactions described herein, suggestive of similar diastereocontrol elements in the two reactions.80

|

(13) |

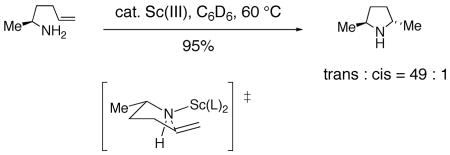

It is also noteworthy that lanthanide catalyzed hydroaminations of primary amines are routinely trans selective operations and are thought to occur via a syn addition mechanism (Eq. 14).4, 73 Conversely, cationic titanocene and zirconocene catalyzed hydroaminations of secondary amines favor formation of the 2,5-cis pyrrolidines (Eq. 15).81 Hydroamination reactions of secondary amines catalyzed by n-BuLi also afford 2,5-cis pyrrolidines.82 Clearly, the nitrogen substituent (H vs Me, Ar or Ts) significantly affects the diastereoselectivity of such reactions (vide infra).

|

(14) |

|

(15) |

Other Pyrrolidine Formation Methods

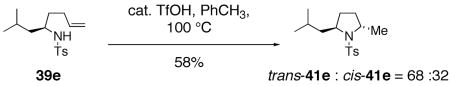

In addition to the methods described above, the Brönsted acid catalyzed cyclization of γ-alkenyl sulfonamide 39e provided a mixture of hydroamination products, pyrrolidines trans-41e and cis-41e, where the trans 2,5-pyrrolidine was slightly favored (Eq. 16).33, 83 The direction of diastereoselectivity and level of stereocontrol in this reaction indicates that the mechanism of the copper(II) carboxylate reactions are not controlled by analogous factors.

|

(16) |

Transition State Analysis for Copper(II) Carboxylate Promoted Carboaminations

Syn addition transition state models that rationalize the observed diastereoselectivity of the copper(II) carboxylate promoted carboamination reactions of substrates with stereocenters alpha to the amine are illustrated in Figure 1. The copper(II) is assumed to be tetracoordinate in these transition states. The top two transition states, A and B, are chair-like, where A leads to the 2,5-cis disubstituted pyrrolidine and B leads to the 2,5-trans disubstituted pyrrolidine. The boat-like transition state C also leads to the 2,5-cis pyrrolidine while the boat-like transition state D leads to the 2,5-trans pyrrolidine. Both the chair and boat transition states A and C that lead to the cis pyrrolidine orient the SO2Ar group trans to the alpha substituent, R. Both the chair and boat transition states B and D that lead to the trans pyrrolidine orient the SO2Ar group syn with respect to substituent R. It appears that the steric interaction between these two groups is the dominant sterecontrol element. Chair-like transition state models of other intramolecular additions of amines to unactivated olefins are typically favored over the boat-like transition states.4, 57, 77, 81

Figure 1.

Competing Syn Addition Transitions States that Lead to the Cis- and Trans-Pyrrolidines

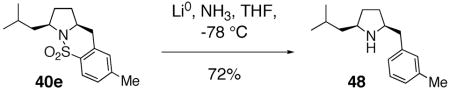

Reductive Removal of Sulfur Dioxide

The use of sulfonamides and sultams as biologically active agents for medicinal chemistry purposes as well as herbicides is well established.84 It is hoped that the methods described in this report for the direct synthesis of sultams from acyclic γ-and δ-alkenyl sulfonamides will prove useful for the synthesis of novel sultam small molecule scaffolds for medicinal chemistry endeavors. Should the free amine be desired, the SO2 unit may be directly excised under dissolving metal conditions (Li, NH3) (Eq. 17).85

|

(17) |

Additionally, methods for the use of sultams directly in Ni(acac)2 catalyzed cross-coupling reactions with Grignard reagents has been reported and provides a method for subsequent C-C bond formation.86

Conclusion

The low cost of copper and the wide range of valuable transformations enabled by this metal continue to stimulate significant research effort in the discovery, development and refinement of copper facilitated chemistry.22, 38, 87–104 The mechanism of these reactions is often complicated by the dual polar, organometallic and redox properties of copper and it is often difficult to differentiate between radical and polar reaction mechanisms. We have reported the first copper promoted addition of unfunctionalized nitrogens to unactivated alkenes forming a new sp3 stereocenter.11, 14 As described herein, we have found these reactions to be highly diastereoselective in a number of cases and useful for the synthesis of a range of five- and six-membered nitrogen heterocycles, We have provided evidence for a syn aminocupration pathway for the formation of the N-C bond. A copper-facilitated N-C bond-forming process is required in order for asymmetric induction controlled by chiral ligands on copper(II) to be envisioned. We have also provided evidence for a carbon radical intermediate that can either undergo intramolecular addition to aryl rings or hydrogen abstraction from the reaction medium. We have also observed oxidative amination with internal alkene substrates. Thus far we have demonstrated that both net intramolecular carboamination and diamination of unactivated alkenes can be efficiently facilitated by copper (II) carboxylates.11, 14 This chemistry should also be amenable to the addition of other functional groups to alkenes via either radical or copper facilitated mechanisms and studies along those lines, as well as additional mechanistic studies and exploration of asymmetric catalysis methods, will be reported in due course.

Experimental Section

Representative Synthesis of alpha-substituted N-tosyl-4-pentenyl amines (substrates in Table 4) (S)-N-Tosyl-1-isopropyl-4-pentenyl amine (39a)

Magnesium metal (254 mg, 10.5 mmol, 5 equiv) was placed in a 25 mL 2-neck flask equipped with a reflux condenser and magnetic stirring bar, and was suspended in 10 mL Et2O under Ar(g). Freshly distilled allyl bromide (1.24 g, 0.89 mL, 10.5 mmol, 5 equiv) was added dropwise at r.t. The mixture was stirred for 2 h (until the magnesium was consumed). (S)-2-Isopropyl-N-tosylaziridine105 (500 mg, 2.1 mmol, 1 equiv) was dissolved in 5 mL Et2O under Ar(g) and added dropwise. The mixture was stirred for an additional 16 h. The reaction was quenched with saturated NH4Cl(aq) (15 mL), and extracted with ethyl acetate (2×10 mL). The crude oil was purified by flash chromatography on SiO2 (20% EtOAc in hexanes) to give 428 mg (S)-N-tosyl-1-isopropyl-4-pentenyl amine (39a) in a 73% yield as a white solid. Data for 39a: mp 49–51 °C, [α]20D −8.6 (c=1.0, CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.74 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 5.64 (m, 1 H), 4.85–4.95 (m, 2 H), 4.26 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H), 3.12 (m, 1 H), 2.41 (s, 3 H), 1.85–1.95 (m, 2 H), 1.73 (m, 1 H), 1.48 (m, 1 H), 1.30 (m, 1 H), 0.78 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 3 H), 0.76 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 143.2, 138.9, 138.3, 130.0, 127.6, 115.5, 59.3, 31.6, 31.5, 30.3, 22.0, 18.7, 18.1; IR (neat, thin film) ν 2961, 1641, 1599, 1429, 1323, 1156, 1094 cm−1; HRMS (EI) Calcd for C15H23O2NS [M]+: 281.1444, found 281.1447.

Representative Procedure (Table 4) for Carboamination Reactions in Microwave: (3S, 10aS)-3-iso-propyl-8-methyl-2,3,10,10a-tetrahydro-1H-pyrrolo[1,2-b][1,2]benzothiazine 5,5-dioxide (40a) and (2S, 5S)-N-tosyl-2-iso-propyl-5-methyl-pyrrolidine (41a)

(S)-N-tosyl-1-isopropyl-4-pentenyl amine 39a (35.1 mg, 0.125 mmol) in a microwave vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar was treated with copper(II) neodecanoate (60% by wt. in toluene, 152 mg, 0.275 mmol, 3 equiv), and Cs2CO3 (40.7 mg, 0.125 mmol, 1 equiv) and dissolved in DMF (1.3 mL) under Ar(g). The vial was sealed and the reaction mixture was heated at 210 °C for 1.5 h in a microwave. After cooling to r.t., it was heated again at 210 °C for 1.5 h in a microwave. The mixture was cooled to r.t., diluted with Et2O, and washed with sat. EDTANa2(aq). The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvents removed in vacuo. The mixture was purified by flash chromatography on SiO2 (10–30% EtOAc in hexanes gradient) providing (S,S)-N-tosyl-2-iso-propyl-5-methyl-pyrrolidine 41a (9.8 mg, 0.0351 mmol) in 28% yield (Rf = 0.5 in 10% EtOAc in hexanes) and (S,S)-3-iso-propyyl-8-methyl-2,3,10,10a-tetrahydro-1H-pyrrolo[1,2-b][1,2]benzothiazine 5,5-dioxide 40a (17.8 mg, 0.0639 mmol) in 51% yield (Rf = 0.3 in 10% EtOAc in hexanes).

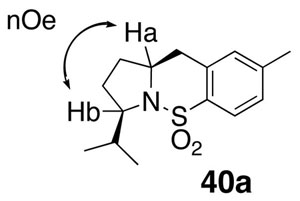

The relative stereochemistry of the carboamination product 40a was determined by a 1D nOe experiment that showed a signal between Ha and Hb.

Data for 40a: mp 85–88 °C; [α]20D +198.9 (c=1.2, CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.77 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.02 (s, 1 H), 4.11 (m, 1 H), 3.94 (m, 1 H), 2.88–3.09 (m, 2 H), 2.36 (s, 3 H), 2.24 (m, 1 H), 2.19 (m, 1 H), 1.86–1.90 (m, 2 H), 1.76 (m, 1 H), 0.93 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3 H), 0.88 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 142.8, 136.3, 135.8, 130.0, 128.7, 124.3, 62.5, 60.8, 36.7, 32.9, 32.6, 29.6, 21.9, 20.4, 16.5; IR (neat, thin film) ν 2962, 1698, 1465, 1323, 11578,1094, 909 cm−1; HRMS (EI) Calcd for C15H21O2NSNa [M+Na]+: 302.1185, found: 302.1192.

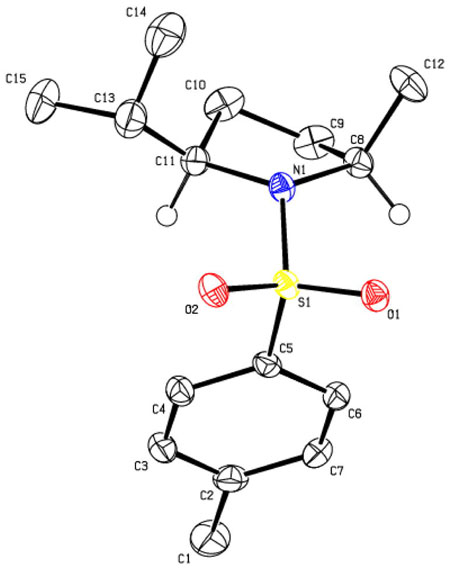

The relative stereochemistry of the hydroamination product 41a was determined by X-ray crystallography.

X-ray Structure of (2S, 5S)-N-tosyl-2-iso-propyl-5-methyl-pyrrolidine (41a)

Data for 41a: mp 83–86°C, [α]20D + 130.0 (c=0.28, CHCl3); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.72 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.30 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.65 (m, 1 H), 3.40 (m, 1 H), 2.42 (s, 3 H), 2.10 (m, 1 H), 1.30–1.65 (m, 4 H), 1.29 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3 H), 0.98 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H), 0.92 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H); 13C NMR(75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 143.0, 135.2, 129.5, 127.6, 67.4, 57.3, 31.9, 31.5, 25.3, 23.1, 21.5, 20.0, 17.3; IR (neat, thin film) ν2962, 1734, 1592, 1459, 1341, 1153, 1096, 1014 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) Calcd for C15H24O2NS [M+H]+: 282.1522, found: 282.1524.

Representative procedure for carboamination in oil bath (Table 4)

(S)-N-Tosyl-1-iso-propyl-4-pentenyl amine 39a (92.6 mg, 0.330 mmol) was treated with copper(II) neodecanoate (60% by wt. in toluene, 402 mg, 0.990 mmol, 3 equiv), and cesium carbonate (108 mg, 0.330 mmol, 1 equiv) in DMF (3.3 mL) under Ar(g) in a pressure tube equipped with a magnetic stir bar. The tube was capped and the mixture was heated at 190 °C for 72 h. Work-up and chromatography as described above provided the carboamination adduct 40a (45.2 mg, 0.162 mmol) in 49% yield, and the hydroamination adduct 41a (23.2 mg, 0.083 mmol) in 25% yield.

Supplementary Material

Procedures and characterization data and NMR spectra for all new products and X-Ray data in the form of CIF files. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Cara L. Nygren [CCDC 614781 (trans-17) and CCDC 296132 (41a)] and Dr. Marc Messerschmidt [CCDC 628996 (trans-20)] for X-ray crystallographic analysis. The authors thank Prof. Dennis Curran and Dr. Maria Manzoni for helpful discussions. The authors thank Mr. Thomas Zabawa and Mr. Thomas Hayes for their efforts in the synthesis of substrates 14-D and 22, respectively. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the NIH (NIGMS 1RO1-GM07838301) and the donors of the Petroleum Research Fund (PRF 40968-G1).

References

- 1.Müller TE, Beller M. Chem Rev. 1998;98:675–703. doi: 10.1021/cr960433d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeni G, Larock RC. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2285–2309. doi: 10.1021/cr020085h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura I, Yamamoto Y. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2127–2198. doi: 10.1021/cr020095i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong S, Marks TJ. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:673–686. doi: 10.1021/ar040051r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegedus LS. In: Chap. 3.1. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, editor. Permagon; New York: 1991. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larock RC, Yang H, Weinreb SM, Herr RJ. J Org Chem. 1994;59:4172–4178. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overman LE, Remarchuk TP. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12–13. doi: 10.1021/ja017198n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lutete LM, Kadota I, Yamamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1622–1623. doi: 10.1021/ja039774g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fix SR, Brice JL, Stahl SS. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:164–166. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020104)41:1<164::aid-anie164>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trend RM, Ramtohul YK, Ferreira EM, Stoltz BM. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:2892–2895. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman ES, Chemler SR, Tan TB, Gerlits O. Org Lett. 2004;6(10):1573–1575. doi: 10.1021/ol049702+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manzoni MR, Zabawa TP, Kasi D, Chemler SR. Organometallics. 2004;23:5618–5621. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lei A, Lu X, Liu G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:1785–1788. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zabawa TP, Kasi D, Chemler SR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11250–11251. doi: 10.1021/ja053335v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Streuff J, Hovelmann CH, Nieger M, Muniz K. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14586–14587. doi: 10.1021/ja055190y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexanian EJ, Lee C, Sorensen EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:7690–7691. doi: 10.1021/ja051406k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donohoe TJ, Chughtai MJ, Klauber DJ, Griffin D, Campbell AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2514–2515. doi: 10.1021/ja057389g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donohoe TJ, Johnson PD, Pye RJ, Keenan M. Org Lett. 2004;6:2583–2585. doi: 10.1021/ol049136i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lira R, Wolfe JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13906–13907. doi: 10.1021/ja0460920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ney JE, Wolfe JP. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:3605–3608. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertrand MB, Wolfe JP. Tetrahedron. 2005;61(26):6447–6459. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiroya K, Itoh S, Sakamoto T. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:10958–10964. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fallis AG, Brinza IM. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:17543–17594. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bender CF, Widenhoefer RA. Org Lett. 2006;8:5303–5305. doi: 10.1021/ol062107i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donohoe TJ, Churchill GH, Wheelhouse KMP, Glossop PA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:8025–8028. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakhla JS, Kampf JW, Wolfe JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2893–2901. doi: 10.1021/ja057489m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yip KT, Yang M, Law KL, Zhu NY, Yang D. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3130–3131. doi: 10.1021/ja060291x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molander GA, Pack SK. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:10581–10591. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharp LA, Zard SZ. Org Lett. 2006;8:831–834. doi: 10.1021/ol052749q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banwell MG, Lupton DW. Heterocycles. 2006;68(1):71–92. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senboku H, Kajizuka Y, Hasegawa H, Fujita H, Suginome H, Orito K, Tokuda M. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:6465–6474. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasegawa H, Senbuku H, Kajizuka Y, Orito K, Tokuda M. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:827–832. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin Y, Zhao G. Heterocycles. 2006;68(1):23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ito R, Migita T, Morikawa N, Simamura O. Tetrahedron. 1965;21:955–961. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pryor WA, Davis WH, Jr, Gleaton JH. J Org Chem. 1975;40:2099–2102. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larhed M, Moberg C, Hallberg A. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:717–727. doi: 10.1021/ar010074v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beesley RM, Ingold CK, Thorpe JF. J Chem Soc. 1915;107:1080. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kochi JK. Acc Chem Res. 1974;7:351–360. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iqbal J, Bhatia B, Nayyar NK. Chem Rev. 1994;94:519–564. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kohler JJ, Speckamp WN. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977;(7):631–634. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Speckamp WN, Kohler JJ. Chem Commun. 1978:166–167. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohler JJ, Speckamp WN. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977;(7):635–638. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loven R, Speckamp WN. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972:1567–1570. [Google Scholar]

- 44.da Mata MLEN, Motherwell WB, Ujjainwalla F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonfand E, Motherwell WB, Pennell AMK, Uddin MK, Ujjainwalla F. Heterocycles. 1997;46:523–534. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Root KS, Hill CL, Lawrence LM, Whitesides GM. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:5405–5412. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kochi JK, Bacha JD. J Org Chem. 1968;33:2746–2754. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pichon M, Figadere B. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1996;7:927–964. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aliyama T, Ishida Y, Kagoshima H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:4219–4222. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cotton FA, Wilkinson G, Murillo CA, Bochmann M. Advanced Inorganic Chemistry. 6. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chmielewski PJ, Latos-Grazynski L, Schmidt I. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:5475–5482. doi: 10.1021/ic000051x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neale RS. Synthesis. 1971;1:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stella L. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1983;22:337–422. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gagosz F, Moutrille C, Zard SZ. Org Lett. 2002;4:2707–2709. doi: 10.1021/ol026221m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clark AJ, Filik RP, Peacock JL, Thomas GH. Synlett. 1999:441–443. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boivin J, Callier-Dublanchet AC, Quiclet-Sire B, Schiana AM, Zard SZ. Tetrahedron. 1995;51(23):6517–6528. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clark AJ, Deeth RJ, Samuel CJ, Wongtap H. Synlett. 1999;4:444–446. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daoust B, Lessard J. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:3495–3514. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heuger G, Kalsow S, Gottlich R. Eur J Org Chem. 2002:1848–1854. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Togo H, Hoshina Y, Muraki T, Nakayama H, Yokoyama M. J Org Chem. 1998;63:5193–5200. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martin A, Perez-Martin I, Suarez E. Org Lett. 2005;7:2027–2030. doi: 10.1021/ol050526u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Broka CA, Gerlits JF. J Org Chem. 1988;53:2144–2150. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bougeois JL, Stella L, Surzur JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsuritani T, Shinokubo H, Oshima K. Org Lett. 2001;3:2709–2711. doi: 10.1021/ol016310j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsuritani T, Shinokubo H, Oshima K. J Org Chem. 2003;68:3246–3250. doi: 10.1021/jo034043k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu H, Li C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:5983–5985. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hemmerling M, Sjoholm A, Somfai P. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1999;10:4091–4094. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamaguchi J-i, Takeda T. Chem Lett. 1992;(10):1933–1936. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Minakata S, Ohshima Y, Takemiya A, Ryu I, Komatsu M, Ohshiro Y. Chem Lett. 1997;(4):311–312. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maeda Y, Nishimura T, Uemura S. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2003;76:2399–2403. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nicolaou KC, Baran PS, Zhong YL, Barluega S, Hunt KW, Kranich R, Vega JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2233–2244. doi: 10.1021/ja012126h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Horner JH, Musa OM, Bouvier A, Newcomb M. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7738–7748. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim JY, Livinghouse T. Org Lett. 2005;7(20):4391–4393. doi: 10.1021/ol051574h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Williams DR, Osterhout MH, McGill JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30(11):1327–1330. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takacs JM, Helle MA, Sanyal BJ, Eberspacher TA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31(47):6765–6768. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harding KE, Marman TH. J Org Chem. 1984;49:2838–2840. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harding KE, Burks SR. J Org Chem. 1981;46:3920–3922. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kang SH, Lee JH, Lee SB. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ney JEHMB, Yang Q, Wolfe JP. Adv Synth Catal. 2005;347:1614–1620. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200505172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bertrand MB, Wolfe JP. Org Lett. 2006;8(11):2353–2356. doi: 10.1021/ol0606435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gribkov DV, Hultzsch KC. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:5542–5546. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fujita H, Tokuda M, Nitta M, Suginome H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6359–6362. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schlummer B, Hartwig JF. Org Lett. 2002;4:1471–1474. doi: 10.1021/ol025659j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sammes PG. In: Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry. Chap 71 Hansch C, Sammes PG, Taylor JB, editors. Vol. 2. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Evans P, McCabe T, Morgan BS, Reau S. Org Lett. 2005;7(1):43–46. doi: 10.1021/ol0480123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Milburn RR, Snieckus V. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;42:888–891. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ley SV, Thomas AW. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:5400–5449. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hassan J, Sevignon M, Gozzi C, Schulz E, Lemaire M. Chem Rev. 2002;102:1359–1469. doi: 10.1021/cr000664r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen X, Hao XS, Goodhue CE, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6790–6791. doi: 10.1021/ja061715q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Baran PS, Richter JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7450–7451. doi: 10.1021/ja047874w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li X, Hewgley B, Mulrooney CA, Yang J, Kozlowski MC. J Org Chem. 2003;68:5500–5511. doi: 10.1021/jo0340206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Taylor JG, Whittall N, Hii KKM. Org Lett. 2006;8:3561–3564. doi: 10.1021/ol061355b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rovis T, Evans DA. Prog Inorg Chem. 2001;50:1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang Q, Chan TR, Hilgraf R, Folkin VV, Sharpless KB, Finn MG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3192–3193. doi: 10.1021/ja021381e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kanazawa C, Kamijo S, Yamamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10662–10663. doi: 10.1021/ja0617439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Laitar DS, Tsui EY, Sadighi JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11036–11037. doi: 10.1021/ja064019z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gooben LJ, Deng G, Levy LM. Science. 2006;313:662–664. doi: 10.1126/science.1128684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Barun O, Ila H, Junjappa H. J Org Chem. 2000;65:1583–1587. doi: 10.1021/jo9916129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhu J, Grigoriadis NP, Lee JP, Porco JAJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9342–9343. doi: 10.1021/ja052049g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chemler SR, Fuller PH. Chem Soc Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1039/B607819M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ezquerra J, Pedregan C, Lamas C. J Org Chem. 1996;61:5804–5812. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hiroya K, Itoh S, Sakamoto T. J Org Chem. 2004;69:1126–1136. doi: 10.1021/jo035528b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xu L, Lewis IR, Davidsen SK, Summers JB. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:5159–5162. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Martin R, Rivero MR, Buchwald SL. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:7079–7082. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Berry MB, Craig D. Synlett. 1992:41. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Procedures and characterization data and NMR spectra for all new products and X-Ray data in the form of CIF files. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.