Abstract

Ultraviolet (u.v.) inactivated Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) induces rapid calcium flux in naïve BALB/c CD4+ T cells. CD4+ cells lacking decay accelerating factor (DAF-/-) show little calcium flux indicating that virus cross-linking of this virus receptor protein is necessary for calcium signaling in CVB3 infection. Interaction of CVB3 with CD4+ cells also activates NFAT DNA binding. To show that NFAT activation is crucial to CVB3 induced disease, wild type mice and transgenic mice expressing dominant-negative NFAT (dnNFAT) mutant in T cells were infected and evaluated for myocarditis and pancreatitis 7 days later. Inhibition of NFAT in T cells prevented myocarditis but had no effect on pancreatitis. Virus titers in pancreas were equivalent in wild-type and dnNFAT animals but cardiac virus titers were increased in dnNFAT mice. Interferon-gamma (IFNγ) expression was reduced in both CD4+ and Vγ4+ T cells from dnNFAT mice compared to controls. FasL expression by Vγ4+ cells was also suppressed. Inhibition of FasL expression by Vγ4+ cells is consistent with myocarditis protection in dnNFAT mice.

Keywords: Coxsackievirus, NFAT, Transcription Factor, Myocarditis

Introduction

Enteroviruses, including coxsackie B viruses, are often etiological agents causing myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy (Bowles et al., 1986; Bowles et al., 2003). Infection Coxsackieviruses are members of the picornavirus family of small non-enveloped RNA viruses which replicate in the cell cytoplasm and are usually considered to be released from infected cells through cell lysis (Rueckert, 1996). As with nearly all microbial infections, the host response is both diverse and complex (Fairweather et al., 2001; Gauntt et al., 2000). Furthermore, host response to the virus, in one form or another, may be essential to the virus for replication. Studies have found that coxsackieviruses can only successfully replicate in cells during the G1/S phase of the cycle due to requirements for virus RNA translation (Feuer et al., 2003). For only cells already in cycle to be able to support virus replication would substantially increase the virus innocula necessary to establish an infection. It is far more likely that the virus can itself cause cells it binds to enter the cell cycle and/or become activated. There are several different mechanisms by which such activation can occur. These include virus cross-linking of cellular molecules used as the virus receptor and signal transduction through this cross-linking (D'Addario et al., 2000; D'Addario et al., 1999; D'Addario et al., 2001); and signaling through toll-like receptor (TLR) recognition of viral molecules, most notably single stranded (ssRNA) and double stranded (dsRNA) viral RNA (Abreu and Arditi, 2004; Hasan et al., 2005; Lauw, Caffrey, and Golenbock, 2005; Netea, Van der Meer, and Kullberg, 2004; O'Neill, 2004). Virus-induced cellular activation is also the first step in the host response to the infection since TLR signaling is a potent inducer of immune cell proliferation and cytokine/chemokine expression (Rose, 2008; Triantafilou and Triantafilou, 2004). Two transcription factors are well known to be activated during coxsackievirus infections. These are AP-1 and NFkB (Esfandiarei et al., 2007; Kwon et al., 2004). Activation of these transcription factors is mediated through either through interleukin receptor-associated kinases (IRAKs) which activate TRAF6 and IKK, or through interferon response factor 3 and 7 (IRF3 and IRF7). This report is the first to demonstrate a role for NFAT in T cells during coxsackievirus B3 infections.

Results

Coxsackievirus B3 induces calcium flux in lymphocytes through DAF

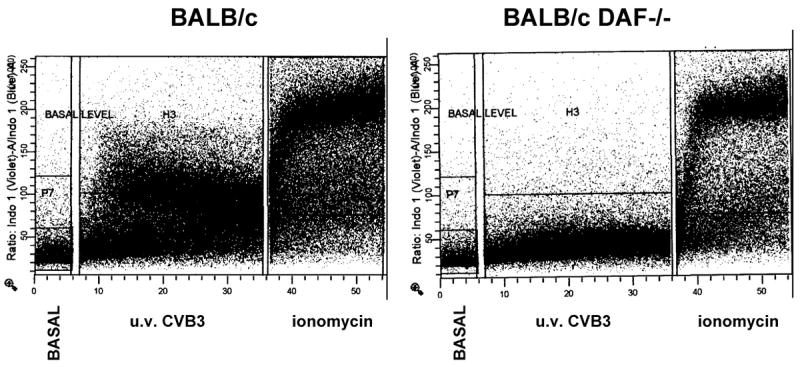

Enriched CD4+ cells from uninfected BALB/c and DAF-/- mice were loaded with Indo-1. Calcium flux was initially determined in unstimulated cells (Figure 1, basal level), then 4 × 108 PFU equivalent of u.v. inactivated H3 virus was added resulting in significant increased calcium flux in the cells in BALB/c cells. Calcium flux was substantially reduced in DAF-/- cells As a positive control, ionomycin was added to the cells after measuring calcium flux induced by the virus.

Figure 1.

Calcium flux on mesenteric lymph node cells. Enriched CD4+ lymphocytes were isolated from naïve BALB/c and BALB/c DAF-/- mice and loaded with Indo-1. Basal levels of calcium flux were determined on unstimulated cells, then 4 × 108 PFU equivalent of u.v. inactivated H3 virus was added and calcium flux determination was continued for the time indicated. As a positive control, ionomycin at a concentration of 250 ng/ml was added to the cells to demonstrate maximum flux.

CVB3 activates NFAT

Calcium flux is critical for the activation of the transcription factor NFAT. Increased intracellular calcium leads to activation of the calcium-dependent phosphatase calcineurin which dephosphorylates NFAT and promotes its translocation to the nucleus (Im and Rao, 2004). To determine if the calcium flux induced by the virus activates NFAT, enriched CD4+ cells from uninfected mice were cultured for 6 or 12 hrs in medium, medium containing 4 × 108 PFU equivalent of u.v. inactivated H3 virus or with 5 ng/ml PMA and 250 ng/ml ionomycin. Nuclear extracts were obtained and evaluated by EMSA using an oligo containing a consensus NFAT binding site (Figure 2A). Incubation of CD4+ cells with CVB3 was sufficient to induce NFAT DNA binding in these cells. Confirmation that bands represent NFAT was obtained by supershift using anti-NFATc1 and anti-NFATc2 antibodies (Figure 2B). Since sucrose purified virus still contains some HeLa cell proteins, approximately 107 HeLa cells were washed with PBS, then alternately frozen and thawed three times. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (300 × g for 10 min) and the supernatant added to BALB/c T cells for 12 hrs (Figure 2C). Additionally, u.v. inactivated virus was added to BALB/c DAF-/- T cells. Neither virus added to DAF-/- T cells nor HeLa cell extract added BALB/c T cells activated NFAT.

Figure 2.

H3 virus induces NFAT activation. (A) CD4+ T cells were treated with medium (M), inactivated H3 (H3) or PMA (5 ng/ml) and ionomycin (250 ng/ml) (PI) for 6 or 12 h. Nuclear extracts were generated and examined by EMSA using an oligo containing consensus NFAT site. (B) CD4+ T cells were activated for 6 and 12 h with H3 virus. Nuclear extracts were generated and examined by EMSA for NFAT DNA binding. Binding reactions were performed in the absence (-) or presence or an anti-NFATc1 (c1) or anti-NFATc2 (c2) antibodies. (C) CD4+ T cells from BALB/c and BALB/c DAF-/- mice were activated for 12 h with u.v. inactivated H3 virus, 250 ng/ml ionomycin (Ion) or 0.1 ml Hela cell extract then nuclear extracts were examined by EMSA for NFAT binding.

NFAT activation promotes induction of myocarditis but not pacreatitis

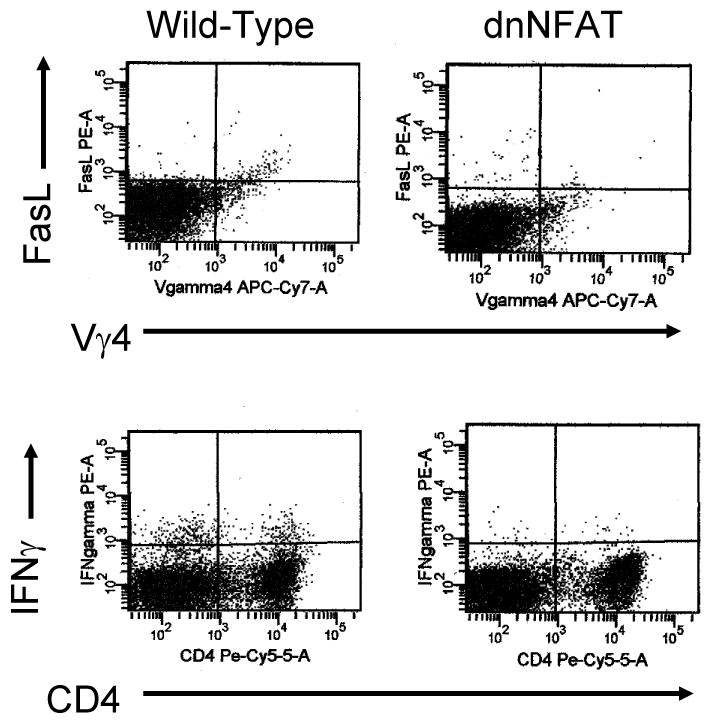

B10.BR and dnNFAT mice were infected with 105 PFU H3 virus and killed 7 days later (Figures 3 and 4). Heart and pancreas were removed and evaluated for inflammation. B10.BR mice develop significant inflammation in both heart (Figure 3, arrow, representative animal) and pancreas. In contrast, dnNFAT mice develop severe pancreatitis but little cardiac inflammation. Figure 4 shows cardiac and pancreatic virus titers (PFU/mg tissue) and shows that dnNFAT mice have significantly more virus in the heart compared to wild-type B10.BR mice, but pancreatic virus titers are equivalent in both animals. Mean myocarditis and pancreatitis scores are given for 5-8 mice/group and demonstrate a consistent reduction of myocarditis but no change in pancreatitis in dnNFAT animals. Differences in cardiovascular disease was also reflected in mean heart:body weight which was 0.057 for dnNFAT and 0.070 for wild-type mice (p<0.05). Previous studies have shown that FasL and IFNγ expression in γδ+ cells are required for induction of myocarditis (Huber et al., 2001; Huber, Shi, and Budd, 2002). Since NFAT regulates FasL expression (Jayanthi et al., 2005; Ranger et al., 1998), spleen lymphocytes from infected B10.BR and dnNFAT mice were labeled with antibodies to Vγ4 and FasL, and intracellularly for IFNγ (Figure 5). Total numbers of Vγ4+ cells were slightly, but not significantly elevated in B10.BR mice compared to dnNFAT animals. However, FasL and IFNγ expression was substantially reduced in the absence of NFAT expression. Figure 6 shows representative flow diagrams of Vγ4+ and CD4+ cells labeled for FasL and IFNγ, respectively. This shows that not only Vγ4+ but also CD4+ cells express less IFNγ in dnNFAT mice.

Figure 3.

Hearts and pancreases from B10.BR and dnNFAT B10.BR male mice infected 7 days earlier with 105 PFU H3 virus were formalin fixed, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Arrow indicates inflammation.

Figure 4.

B10.BR and dnB10.BR mice were infected 7 days earlier with 105 PFU H3 virus. (A) and (B) Heart and pancreas were titered for virus. Data is presented as log10 PFU/mg tissue. (C) and (D) Histology score for inflammation.

Figure 5.

Splenocytes were isolated and labeled with antibodies to Vγ4, FasL and intracellularly for IFNγ. Cells were evaluated by flow cytometry for percent of splenic lymphocytes positive for these markers. Data represents the mean ± SEM for 5-8 individual mice/group. * dnNFAT mice significantly differ from B10.BR animals at p≤0.05.

Figure 6.

Flow cytometry on splenic lymphocytes from infected mice. Cells were labeled with antibodies to Vγ4, FasL and CD4. Some cells were intracellularly labled with antibody to IFNγ. Numbers in upper right indicate percent of cells in each quadrant.

Discussion

This report demonstrates that inactivated CVB3 is capable of inducing rapid calcium flux in naïve T cells and that the calcium flux is largely dependent upon the presence of DAF since little flux is observed in DAF-/- cells. As expected with the amount of calcium flux observed, NFAT is activated in CD4+ cells by the virus exposure. NFAT activation is crucial to myocarditis susceptibility since mice with impaired activation of NFAT (dnNFAT mice) in T cells fail to develop meocarditis despite high concentrations of virus in the heart. Although myocarditis is reduced in infected dnNFAT mice, the amount of pancreatitis and ascinar cell degranulation is unaffected. This observation strongly indicates that the pathogenic mechanisms for myocarditis and pancreatitis subsequent to CVB3 infection differ. The high protease concentrations in the ascinar tissue could lead to auto-digestion of the tissue with even modest levels of virus induced injury while most of the myocardial damage is immune mediated (Woodruff and Woodruff, 1974). This is the first report that NFAT is activated during CVB3 infection.

Two cellular receptors are best known for coxsackieviruses. These are: decay accelerating factor (DAF, CD55) and coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor (CAR). DAF is expressed in non-attached cells such as leukocytes and may be responsible for the infection and replication of CVB3 in B cells, dendritic cells and activated T cells (Anderson et al., 1996; Liu et al., 2000). Chimeric fusion proteins (DAF-Fc and CAR-Fc) are highly effective in inhibiting coxsackievirus infection in the heart but CAR-Fc alone prevents virus infection of the pancreas (Goodfellow et al., 2005; Yanagawa et al., 2003; Yanagawa et al., 2004). Coxsackievirus interactions with both CAR and DAF leads to optimal infection (Selinka et al., 2004), however, CAR appears to be the dominant receptor and can lead to infection with little or no DAF involvement (Pasch et al., 1999). Since DAF is not involved in CVB3 infection of the pancreas or induction of pancreatitis, it is reasonable that virus binding to DAF and activation of NFAT through this pathway would not affect pancreatitis although inhibition of DAF signal transduction and NFAT activation in the heart would be pathogenically important. DAF is a GPI anchored membrane protein, is localized to the lipid raft fraction and can initiate signal transduction through protein tyrosine kinases p56lck and p59fyn, early factors in CD3-TCR pathway (Shenoy-Scaria et al., 1992; Tosello et al., 1998). Antibody cross-linking of GPI anchored proteins can lead to increased free cytosolic calcium concentrations (Kroczek et al., 1986) which would be expected to activate NFAT (Rao, Luo, and Hogan, 1997), which is known to be dependent on calcium signaling. Thus, it is not surprising that coxsackieviruses which cross-link DAF could lead to calcium flux and NFAT activation. NFAT activation regulates expression of multiple genes involved in cell differentiation and proliferation (Hogan et al., 2003). Many of these genes could impact CVB3 induced myocarditis. One prime candidate gene controlled by NFAT is FasL (Jayanthi et al., 2005). Although this communication reports on virus signaling through DAF in T lymphocytes, other cell types can also be involved. We have data showing that u.v. inactivated CVB3 effectively binds to endothelial cells (CD31+) derived from the mouse heart and induces calcium flux similar to that seen in T cells (data not shown). Thus it is reasonable that this signal transduction pathway could alter protein expression in both cardiocytes and cells of the immune system.

Coxsackievirus B3 infection dramatically enhances FasL expression on T cells expressing the γδ T cell receptor (Huber, Shi, and Budd, 2002). Furthermore, previous studies showed that mice lacking either Fas or FasL fail to develop myocarditis despite normal virus infection in the heart (Huber, Shi, and Budd, 2002). FasL expression on γδ+ cells determines susceptibility since adoptive transfer of wild-type (FasL+) γδ+ T cells into mice lacking FasL (gld/gld) but expressing Fas restores complete myocarditis susceptibility. In contrast, γδ+ cells lacking FasL were incapable of inducing myocarditis. Thus, it is highly probable that a key factor involved in NFAT control of disease susceptibility is FasL expression on these innate effectors. As shown in this report, mice dnNFAT transgenic mice express substantially less FasL than wild-type animals. Similarly, dnNFAT mice express little IFNγ. While NFAT does not promote IFNγ expression directly, FasL+ γδ+ cells do promote a Th1 response characterized by CD4+IFNγ+ cells (Huber, Shi, and Budd, 2002). The mechanism by which γδ+ cells promote the Th1 response is not completely understood, but these effectors are capable of selectively killing CD4+IL-4 (Th2) cell clones through FasL dependent pathways (Huber, Sartini, and Exley, 2003). Selective elimination of Th2 cells could result in enrichment of the remaining Th1 cells.

Although inactivated virus is capable of activating NFAT, it is not directly able to induce myocarditis, at least at the equivalent PFU concentrations (105 PFU) of live virus used to infect mice (personal observation). Most likely, rapid virus replication of live virus in vivo substantially increases antigen load resulting in adequate virus epitope concentration to activate adaptive immunity. These epitope concentrations would not be achieved using inactivated virus unless considerably more antigen (microgram) concentrations are used. Also, live virus signals through Toll-like receptors to activate NFkB as well as signaling through the virus recptor, DAF, to activate NFAT (Michelsen et al., 2004). Most likely, lack of any individual mechanism (adequate antigen processing/presentation, TLR signaling or virus receptor signaling) would be sufficient to prevent myocarditis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Male BALB/cJ mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor ME. Male B10.BR and dominant-negative NFAT transgenic mice on the B10.BR background (Chow, Rincon, and Davis, 1999), were obtained from Dr. Mercedes Rincon at the University of Vermont. Decay accelerating factor knockout mice on the BALB/c background (DAF-/-) were kindly provided by Dr. Wenchao Song, (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia PA) as described previously (Huber, Song, and Sartini, 2006), and were bred at the University of Vermont. All mice were 5-7 weeks of age when infected.

Virus

The H3 variant of CVB3 was made from an infectious cDNA clone as described previously (Knowlton et al., 1996) and was purified by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion (Frolov, Duque, and Palmenberg, 1999). Virus was grown in HeLa cells until at least 70% of the cell were detached. The cells and supernatant were frozen and thawed three times then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was layered over a cushion of 30% sucrose in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4) and 1M NaCl for 20 hrs at 13,000 rpm using a GSA rotor in a Sorvall RC-5B centrifuge (Wilmington, DE).

Infection of mice

Mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 105 plaque forming units (PFU) virus in 0.5 ml PBS. Animals were killed when mortibund or 7 days after infection.

Organ virus titers

Tissue was asceptically removed from the animals, weighed, homogenized in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, streptomycin and penicillin. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 min. Supernatants were diluted serially using 10-fold dilutions and tittered on Hela cell monolayers by the plaque forming assay (Van Houten et al., 1991).

Histology

Tissue was fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 48 hrs, paraffin embedded, sectioned and stained by hematoxylin and eosin.

Calcium flux

Mesenteric lymph node cells were isolated from naïve mice and pressed through fine mesh screens. CD4+ cells were purified using the BD Biosciences CD4+ enrichment kit according to manufacturer's directions. Purity of the cell population exceeded 90% CD4+ cells. Cells were washed with RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% FBS and resuspended to 3 × 106 cells/ ml in medium containing 3 μM Indo-1 (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR) for 45 min at 37°C. The cells were washed once, resuspended in medium at 1 × 106 cells/ml, and maintained at room temperature. Cells are warmed to 37°C 5 min before use. A baseline calcium flux is determined on unstimulated cells using a BD LSR II (BD Immunocytometry, San Jose CA) equipped with a 355 UV solid state laser (Lightwave XciteTM), 20mW. Changes in the concentration of intracellular free Ca2+ ions were measured by monitoring the change in its emission spectrum from blue to violet upon binding to Ca2+. The blue emission was measured through a 530/30 BP filter and the violet through a 405/20 BP and 405 LP filter. A shift in the violet/blue ratio over time is a reflection of the increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration.

H3 virus was exposed to ultraviolet irradiation for 15 min and assayed by plaque forming assay to prove the virus was no longer infectious. Cells were stimulated by adding 4 × 108 PFU equivalent of the u.v. inactivated virus. As a positive control, 500 ng/ml ionomycin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis MO) was added to the same cells after calcium flux determination with virus.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared from stimulated and unstimulated enriched CD4+ T cells isolated from uninfected BALB/c mice as previously described (Schreiber et al., 1989; Tugores et al., 1992). Stimulation was provided by addition of 4 × 108 PFU equivalent u.v. inactivated H3 virus or 5 ng/ml PMA and 250 ng/ml ionomycin to the cells for 6 or 12 hrs at 37°C. Binding reactions were performed using 2 μg of nuclear proteins and [32P]dCTP end-labeled double stranded oligonucleotide probes containing an consensus NFAT binding site from the proximal IL-4 promoter (Rooney et al., 1994). Samples were then electrophoresed under nondenaturing conditions and exposed to film for autoradiography. Anti-NFATc1 and anti-NFATc2 antibodies (Affinity Biocortex) were used (1 μl per reaction) for supershift experiment.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Details for intracellular cytokine staining have been published previously (Huber et al., 2001). Spleens were removed and pressed through fine mesh screens. Lymphoid cells were isolated by centrifugation of cell suspensions on Histopaque (Sigma). 105 cells were cultured for 4 hrs in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 μg/ of Brefeldin A (BFA; Sigma), 50 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma), and 500 ng/ml ionomycin (Sigma). After culture, the cells were washed in PBS-1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) containing BFA, incubated on ice for 30 min in PBS-BSA-BFA containing a 1:100 dilution of Fc Block, Cy-chrome conjugated anti- hamster anti-Vγ4 (clone UC3), PE anti-FasL (clone Kay-10), PE-rat-IgG2 (isotype control; clone R35-95) or Cy-chrome- hamster IgG (isotype control; clone G235-2356). All antibodies were from Pharmingen. The cells were washed once with PBS-BSA-BFA, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, then resuspended in PBS-BSA containing 0.5% saponin, Fc Block and 1:100 dilutions of FITC anti-IFNγ or FITC- and PE-rat IgG1 (clone R3-34) and incubated for 30 min on ice. The cells were washed once in PBS-BSA-saponin and once in PBS-BSA, the resuspended in 2% paraformaldehyde and analyzed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer with a single excitation wavelength (488 nm) and band filters for Cy-chrome (670 nm), FITC (525 nm), and PE (575 nm). The cell population was classified for cell size (forward scatter) and complexity (side scatter). At least 10,000 cells were evaluated. Positive staining was determined relative to isotype controls.

Statistics

Differences between groups were determined by Wilcoxon Ranked Score.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL80594, HL86549 and AI45666. The authors also wish to thank Colette Charland for help with flow cytometry and Kevin Kolinich for help in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abreu MT, Arditi M. Innate immunity and toll-like receptors: clinical implications of basic science research. J Pediatr. 2004;144(4):421–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D, Wilson J, Carthy C, Yang D, Kandolf R, McManus B. Direct interactions of coxsackievirus B3 with immune cells in the splenic compartment of mice susceptible or resistant to myocarditis. J Virol. 1996;70(7):4632–4645. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4632-4645.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles N, Richardson P, Olsen E, Archard L. Detection of coxsackie B virus-specific RNA sequences in myocardial biopsy samples from patients with myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 1986;I:1120–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91837-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles NE, Ni J, Kearney DL, Pauschinger M, Schultheiss HP, McCarthy R, Hare J, Bricker JT, Bowles KR, Towbin JA. Detection of viruses in myocardial tissues by polymerase chain reaction. evidence of adenovirus as a common cause of myocarditis in children and adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(3):466–72. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00648-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow CW, Rincon M, Davis RJ. Requirement for transcription factor NFAT in interleukin-2 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(3):2300–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Addario M, Ahmad A, Morgan A, Menezes J. Binding of the Epstein-Barr virus major envelope glycoprotein gp350 results in the upregulation of the TNF-alpha gene expression in monocytic cells via NF-kappaB involving PKC, PI3-K and tyrosine kinases. J Mol Biol. 2000;298(5):765–78. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Addario M, Ahmad A, Xu JW, Menezes J. Epstein-Barr virus envelope glycoprotein gp350 induces NF-kappaB activation and IL-1beta synthesis in human monocytes-macrophages involving PKC and PI3-K. Faseb J. 1999;13(15):2203–13. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.15.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Addario M, Libermann TA, Xu J, Ahmad A, Menezes J. Epstein-Barr Virus and its glycoprotein-350 upregulate IL-6 in human B-lymphocytes via CD21, involving activation of NF-kappaB and different signaling pathways. J Mol Biol. 2001;308(3):501–14. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esfandiarei M, Boroomand S, Suarez A, Si X, Rahmani M, McManus B. Coxsackievirus B3 activates nuclear factor kappa B transcription factor via a phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/protein kinase B-dependent pathway to improve host cell viability. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9(10):2358–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairweather D, Kaya Z, Shellam GR, Lawson CM, Rose NR. From infection to autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2001;16(3):175–86. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2000.0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuer R, Mena I, Pagarigan RR, Hassett DE, Whitton JL. Coxsackievirus replication and the cell cycle: a potential regulatory mechanism for viral persistence/latency. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl) 2003 doi: 10.1007/s00430-003-0192-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolov VG, Duque H, Palmenberg AC. Quantification of endogenous viral polymerase, 3D(pol), in preparations of Mengo and encephalomyocarditis viruses. Virology. 1999;260(1):148–55. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauntt C, Sakkinen P, Rose N, Huber S. Picornaviruses: Immunopathology and autoimmunity. In: Cunningham M, Fujinami R, editors. Effects of Microbes on the Immune System. Lippincott-Raven Publishers; Philadelphia: 2000. pp. 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow IG, Evans DJ, Blom AM, Kerrigan D, Miners JS, Morgan BP, Spiller OB. Inhibition of coxsackie B virus infection by soluble forms of its receptors: binding affinities, altered particle formation, and competition with cellular receptors. J Virol. 2005;79(18):12016–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.12016-12024.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan U, Chaffois C, Gaillard C, Saulnier V, Merck E, Tancredi S, Guiet C, Briere F, Vlach J, Lebecque S, Trinchieri G, Bates EE. Human TLR10 is a functional receptor, expressed by B cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells, which activates gene transcription through MyD88. J Immunol. 2005;174(5):2942–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan PG, Chen L, Nardone J, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 2003;17(18):2205–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.1102703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S, Graveline D, Born W, O'Brien R. Cytokine Production by Vgamma+ T Cell Subsets is an Important Factor Determining CD4+ Th Cell Phenotype and Susceptibility of BALB/c mice to Coxsackievirus B3-Induced Myocarditis. J Virol. 2001;75(13):5860–5868. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.5860-5869.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S, Sartini D, Exley M. Role of CD1d in coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. J Immunol. 2003;170(6):3147–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S, Shi C, Budd RC. Gammadelta T cells promote a Th1 response during coxsackievirus B3 infection in vivo: role of Fas and Fas ligand. J Virol. 2002;76(13):6487–94. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6487-6494.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S, Song WC, Sartini D. Decay-accelerating factor (CD55) promotes CD1d expression and Vgamma4+ T-cell activation in coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. Viral Immunol. 2006;19(2):156–66. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im SH, Rao A. Activation and deactivation of gene expression by Ca2+/calcineurin-NFAT-mediated signaling. Mol Cells. 2004;18(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi S, Deng X, Ladenheim B, McCoy MT, Cluster A, Cai NS, Cadet JL. Calcineurin/NFAT-induced up-regulation of the Fas ligand/Fas death pathway is involved in methamphetamine-induced neuronal apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(3):868–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404990102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton KU, Jeon ES, Berkley N, Wessely R, Huber S. A mutation in the puff region of VP2 attenuates the myocarditic phenotype of an infectious cDNA of the Woodruff variant of coxsackievirus B3. J Virol. 1996;70(11):7811–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7811-7818.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroczek RA, Gunter KC, Germain RN, Shevach EM. Thy-1 functions as a signal transduction molecule in T lymphocytes and transfected B lymphocytes. Nature. 1986;322(6075):181–4. doi: 10.1038/322181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon D, Fuller AC, Palma JP, Choi IH, Kim BS. Induction of chemokines in human astrocytes by picornavirus infection requires activation of both AP-1 and NF-kappa B. Glia. 2004;45(3):287–96. doi: 10.1002/glia.10331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauw FN, Caffrey DR, Golenbock DT. Of mice and man: TLR11 (finally) finds profilin. Trends Immunol. 2005;26(10):509–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Aitken K, Kong YY, Opavsky MA, Martino T, Dawood F, Wen WH, Kozieradzki I, Bachmaier K, Straus D, Mak TW, Penninger JM. The tyrosine kinase p56lck is essential in coxsackievirus B3-mediated heart disease. Nat Med. 2000;6(4):429–34. doi: 10.1038/74689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen KS, Doherty TM, Shah PK, Arditi M. TLR signaling: an emerging bridge from innate immunity to atherogenesis. J Immunol. 2004;173(10):5901–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Van der Meer JW, Kullberg BJ. Toll-like receptors as an escape mechanism from the host defense. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12(11):484–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill LA. TLRs: Professor Mechnikov, sit on your hat. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):687–93. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch A, Kupper JH, Wolde A, Kandolf R, Selinka HC. Comparative analysis of virus-host cell interactions of haemagglutinating and non-haemagglutinating strains of coxsackievirus B3. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Pt 12):3153–8. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-12-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranger AM, Oukka M, Rengarajan J, Glimcher LH. Inhibitory function of two NFAT family members in lymphoid homeostasis and Th2 development. Immunity. 1998;9(5):627–35. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80660-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao A, Luo C, Hogan PG. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:707–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney JW, Hodge MR, McCaffrey PG, Rao A, Glimcher LH. A common factor regulates both Th1- and Th2-specific cytokine gene expression. Embo J. 1994;13(3):625–33. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose NR. The Adjuvant Effect in Infection and Autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueckert R. Picronaviruses. In: Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fundamental Virology. 3rd. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia, PA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber E, Matthias P, Muller M, Shaffner W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with “mini-extracts”, prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6419. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selinka HC, Wolde A, Sauter M, Kandolf R, Klingel K. Virus-receptor interactions of coxsackie B viruses and their putative influence on cardiotropism. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2004;193(23):127–31. doi: 10.1007/s00430-003-0193-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy-Scaria AM, Kwong J, Fujita T, Olszowy MW, Shaw AS, Lublin DM. Signal transduction through decay-accelerating factor. Interaction of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchor and protein tyrosine kinases p56lck and p59fyn 1. J Immunol. 1992;149(11):3535–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosello AC, Mary F, Amiot M, Bernard A, Mary D. Activation of T cells via CD55: recruitment of early components of the CD3-TCR pathway is required for IL-2 secretion. J Inflamm. 1998;48(1):13–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantafilou K, Triantafilou M. Coxsackievirus B4-induced cytokine production in pancreatic cells is mediated through toll-like receptor 4. J Virol. 2004;78(20):11313–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11313-11320.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugores A, Alonso MA, Sanchez-Madrid F, de Landazuri MO. Human T cell activation through the activation-inducer molecule/CD69 enhances the activity of transcription factor AP-1. J Immunol. 1992;148(7):2300–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houten N, Bouchard P, Moraska A, Huber S. Selection of an attenuated coxsackievirus B3 variant using a monoclonal antibody reactive to myocyte antigen. J Virol. 1991;65:1286–1290. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1286-1290.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff J, Woodruff J. Involvement of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of coxsackievirus B3 heart disease. J Immunol. 1974;113:1726–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa B, Spiller OB, Choy J, Luo H, Cheung P, Zhang HM, Goodfellow IG, Evans DJ, Suarez A, Yang D, McManus BM. Coxsackievirus B3-associated myocardial pathology and viral load reduced by recombinant soluble human decay-accelerating factor in mice. Lab Invest. 2003;83(1):75–85. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000049349.56211.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa B, Spiller OB, Proctor DG, Choy J, Luo H, Zhang HM, Suarez A, Yang D, McManus BM. Soluble recombinant coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor abrogates coxsackievirus b3-mediated pancreatitis and myocarditis in mice. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(8):1431–9. doi: 10.1086/382598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]