Abstract

Although nitrite ( ) and nitrate

(

) and nitrate

( ) have been considered

traditionally inert byproducts of nitric oxide (NO) metabolism, recent studies

indicate that

) have been considered

traditionally inert byproducts of nitric oxide (NO) metabolism, recent studies

indicate that  represents an

important source of NO for processes ranging from angiogenesis through hypoxic

vasodilation to ischemic organ protection. Despite intense investigation, the

mechanisms through which

represents an

important source of NO for processes ranging from angiogenesis through hypoxic

vasodilation to ischemic organ protection. Despite intense investigation, the

mechanisms through which  exerts its

physiological/pharmacological effects remain incompletely understood. We

sought to systematically investigate the fate of

exerts its

physiological/pharmacological effects remain incompletely understood. We

sought to systematically investigate the fate of

in hypoxia from cellular uptake

in vitro to tissue utilization in vivo using the Wistar rat

as a mammalian model. We find that most tissues (except erythrocytes) produce

free NO at rates that are maximal under hypoxia and that correlate robustly

with each tissue's capacity for mitochondrial oxygen consumption. By comparing

the kinetics of NO release before and after ferricyanide addition in tissue

homogenates to mathematical models of

in hypoxia from cellular uptake

in vitro to tissue utilization in vivo using the Wistar rat

as a mammalian model. We find that most tissues (except erythrocytes) produce

free NO at rates that are maximal under hypoxia and that correlate robustly

with each tissue's capacity for mitochondrial oxygen consumption. By comparing

the kinetics of NO release before and after ferricyanide addition in tissue

homogenates to mathematical models of

reduction/NO scavenging, we show

that the amount of nitrosylated products formed greatly exceeds what can be

accounted for by NO trapping. This difference suggests that such products are

formed directly from

reduction/NO scavenging, we show

that the amount of nitrosylated products formed greatly exceeds what can be

accounted for by NO trapping. This difference suggests that such products are

formed directly from  , without

passing through the intermediacy of free NO. Inhibitor and subcellular

fractionation studies indicate that

, without

passing through the intermediacy of free NO. Inhibitor and subcellular

fractionation studies indicate that  reductase activity involves multiple redundant enzymatic systems

(i.e. heme, iron-sulfur cluster, and molybdenum-based reductases)

distributed throughout different cellular compartments and acting in concert

to elicit NO signaling. These observations hint at conserved roles for the

reductase activity involves multiple redundant enzymatic systems

(i.e. heme, iron-sulfur cluster, and molybdenum-based reductases)

distributed throughout different cellular compartments and acting in concert

to elicit NO signaling. These observations hint at conserved roles for the

-NO pool in cellular processes such

as oxygen-sensing and oxygen-dependent modulation of intermediary

metabolism.

-NO pool in cellular processes such

as oxygen-sensing and oxygen-dependent modulation of intermediary

metabolism.

Nitric oxide (NO)3

is the archetypal effector of redox-regulated signal transduction throughout

phylogeny, from microorganisms to plants and animals

(1). The conserved influences

of NO extend from the regulation of basic cellular processes such as

intermediary metabolism (2),

cellular proliferation (3), and

apoptosis (4) to systemic

processes such as hypoxic vasoregulation

(5). Mammalian NO production

has been attributed to the enzymatic activity of NO synthases, nitrate

( )/nitrite

(

)/nitrite

( ) reductases and non-enzymatic

) reductases and non-enzymatic

reduction

(6). The NO produced is

believed to act directly as a signaling molecule by binding to the heme of

soluble guanylyl cyclase or nitrosating peptide/protein cysteine residues

(7). More recently, it has

become apparent that

reduction

(6). The NO produced is

believed to act directly as a signaling molecule by binding to the heme of

soluble guanylyl cyclase or nitrosating peptide/protein cysteine residues

(7). More recently, it has

become apparent that  , previously

considered an inert byproduct of NO metabolism present in plasma (50–500

nm) and tissues (0.5–25 μm), is, under some

conditions, also a source of NO/nitrosothiol signaling

(6,

8). Although the importance of

, previously

considered an inert byproduct of NO metabolism present in plasma (50–500

nm) and tissues (0.5–25 μm), is, under some

conditions, also a source of NO/nitrosothiol signaling

(6,

8). Although the importance of

has received increasing

appreciation (9) as being

central to processes including exercise

(10), hypoxic vasodilation

(11), myocardial

preconditioning (12,

13), and angiogenesis

(14), controversy surrounds

the chemistry, kinetics, and tissue specificity of

has received increasing

appreciation (9) as being

central to processes including exercise

(10), hypoxic vasodilation

(11), myocardial

preconditioning (12,

13), and angiogenesis

(14), controversy surrounds

the chemistry, kinetics, and tissue specificity of

bioactivity

(15,

16). Perhaps the greatest

uncertainty pertains to the role of heme moieties in

bioactivity

(15,

16). Perhaps the greatest

uncertainty pertains to the role of heme moieties in

metabolism

(6,

10,

12,

13,

15–22).

We therefore sought to address systematically the path of

metabolism

(6,

10,

12,

13,

15–22).

We therefore sought to address systematically the path of

biotransformation in hypoxic

tissues and its processing into NO and NO-related species across levels of

biological organization by employing an experimental paradigm that ranges from

cellular

biotransformation in hypoxic

tissues and its processing into NO and NO-related species across levels of

biological organization by employing an experimental paradigm that ranges from

cellular  uptake in vitro

to tissue

uptake in vitro

to tissue  utilization in

vivo. Our findings reveal that multiple heme, iron-sulfur cluster, and

molybdenum-based reductases, distributed among distinct subcellular

compartments, act in a cooperative manner to convert

utilization in

vivo. Our findings reveal that multiple heme, iron-sulfur cluster, and

molybdenum-based reductases, distributed among distinct subcellular

compartments, act in a cooperative manner to convert

to NO and related signaling

products. The correlation between

to NO and related signaling

products. The correlation between  reductase activity and oxidative phosphorylation capacity across organs

suggests that

reductase activity and oxidative phosphorylation capacity across organs

suggests that  serves a cell

regulatory role (e.g. the modulation of intermediary metabolism)

beyond its capacity to elicit hypoxic vasodilatation.

serves a cell

regulatory role (e.g. the modulation of intermediary metabolism)

beyond its capacity to elicit hypoxic vasodilatation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals and Reagents

Male Wistar rats (250–350 g) from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) were allowed food (2018 rodent diet, Harlan) and water ad libitum and were maintained on a regular 12 h light/12 h dark cycle with at least 10 days of local vivarium acclimatization prior to experimental use. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Boston University School of Medicine. All gasses and chemicals were of the highest available grade (see supplemental information for details).

Biological Sample Harvest and Preparation

Heparinized (0.07 units/g body weight, intraperitoneal) rats were

anesthetized with diethylether and euthanized by cervical dislocation. Whole

blood (3–5 ml) was collected from the inferior vena cava into

EDTA-containing tubes (1.8 mg/mL) and processed as detailed

(23,

24) to obtain RBC and plasma.

Isolated, packed RBC (1 blood vol-equivalent) were immediately lysed

hypotonically with 3 vol of water. After thoracotomy, a catheter was inserted

into the infrarenal portion of the abdominal aorta, and organs were flushed

free of blood by retrograde in situ perfusion at a rate of 10 ml/min

with air-equilibrated PBS before extirpation.

reductase activity was assessed by

measuring the NO generated immediately after addition of 100 μl of a 20

mm NaNO2 stock solution to tissue samples (200

μm final [

reductase activity was assessed by

measuring the NO generated immediately after addition of 100 μl of a 20

mm NaNO2 stock solution to tissue samples (200

μm final [ ]) using

gas-phase chemiluminescence.

]) using

gas-phase chemiluminescence.

Liver Homogenate Preparation

Hepatic tissue was acquired by standard techniques (see supplemental information). Liver homogenate was diluted 180-fold in LHM and preincubated at 37 °C for 4 min with either PBS (vehicle control) or a variety of inhibitors (supplemental Table S1) in a light-protected reaction vessel continuously purged with nitrogen. For analysis of inhibitor effects, the amount of NO generated within the first 4 min of incubation in the presence of test compound was compared with a parallel sample treated only with the respective inhibitor vehicle.

Nitrite Reductase Activity in Subcellular Fractions

Hepatic subcellular fractions were obtained by differential centrifugation

(25). Low-speed centrifugation

(1,000 × g, 10 min) of whole-liver homogenate (S0) was used to

remove undisrupted tissue, nuclei, and particulate debris into the resulting

pellet (P1), which was discarded. The supernatant (S1) was recovered and

re-centrifuged (10,000 × g, 10 min) to obtain a mitochondrial

fraction (P2). The corresponding supernatant (S2) was subjected to a final

centrifugation (105,000 × g, 60 min) to obtain microsomal (P3)

and cytosolic (S3) fractions. For analysis of

reductase activity across

fractions, each mitochondrial (P2) and microsomal (P3) pellet was re-suspended

in LHM to the same dilution as that of the supernatant fractions from which

they were derived and analyzed as described above. The contribution of each

subcellular fraction with respect to total hepatic

reductase activity across

fractions, each mitochondrial (P2) and microsomal (P3) pellet was re-suspended

in LHM to the same dilution as that of the supernatant fractions from which

they were derived and analyzed as described above. The contribution of each

subcellular fraction with respect to total hepatic

reductase activity was calculated

by accounting for the individual fractional product yield (6.2% for P2; 1.3%

for P3; 77.8% for S3, with 14.7% discarded as P1 debris). The influence of

NAD(P)H (100 μm) on the conversion of

reductase activity was calculated

by accounting for the individual fractional product yield (6.2% for P2; 1.3%

for P3; 77.8% for S3, with 14.7% discarded as P1 debris). The influence of

NAD(P)H (100 μm) on the conversion of

to NO by the subcellular fractions

was determined as the relative

to NO by the subcellular fractions

was determined as the relative  reductase activity in the absence or presence of pyridine nucleotide and

expressed as percent of control (with no exogenous pyridine nucleotide added).

reductase activity in the absence or presence of pyridine nucleotide and

expressed as percent of control (with no exogenous pyridine nucleotide added).

interaction with microsomal

cytochrome P450 was assessed by difference spectrophotometry and

chemiluminescence (see supplemental information).

interaction with microsomal

cytochrome P450 was assessed by difference spectrophotometry and

chemiluminescence (see supplemental information).

In Vitro Studies

Uptake by RBCs and

Tissues—Rats were anesthetized with diethylether, and 5 ml of

arterial blood was collected via cardiac puncture. Blood was immediately

centrifuged at 1,400 × g (8 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was

discarded, and the RBC pellet was placed on ice. Blood-free heart and liver

tissue was obtained as described above and also kept on ice until use. Tissue

(0.5 g) was minced into 2-mm pieces and placed into 2 ml of air-saturated or

“hypoxic” (15 min bubbling with air or argon, respectively) PBS

and incubated at 37 °C. Following addition of 10 μm

NaNO2, aliquots of 50 μl were removed after 1, 3, 5, and 10 min

and centrifuged briefly (60 s at 16,100 × g) to clarify samples

prior to

Uptake by RBCs and

Tissues—Rats were anesthetized with diethylether, and 5 ml of

arterial blood was collected via cardiac puncture. Blood was immediately

centrifuged at 1,400 × g (8 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was

discarded, and the RBC pellet was placed on ice. Blood-free heart and liver

tissue was obtained as described above and also kept on ice until use. Tissue

(0.5 g) was minced into 2-mm pieces and placed into 2 ml of air-saturated or

“hypoxic” (15 min bubbling with air or argon, respectively) PBS

and incubated at 37 °C. Following addition of 10 μm

NaNO2, aliquots of 50 μl were removed after 1, 3, 5, and 10 min

and centrifuged briefly (60 s at 16,100 × g) to clarify samples

prior to

analysis. For uptake measurements by RBC, 4 ml of PBS were added to 1 ml of

packed RBC pellet and processed as above. No changes in the concentrations of

analysis. For uptake measurements by RBC, 4 ml of PBS were added to 1 ml of

packed RBC pellet and processed as above. No changes in the concentrations of

were observed in the absence of cells/tissue.

were observed in the absence of cells/tissue.

Tissue Homogenization and Incubation—Blood-free tissue

samples were homogenized in chilled PBS (1:5 w/v) using a Polytron

(PT10–35) homogenizer. Just prior to use, samples were brought with PBS

to a 6-fold final dilution (v/v) for tissues and a 4-fold final dilution (v/v,

equivalent to 2.5% hematocrit) for lysed RBC. For incubation, an equivalent

tissue/RBC sample volume was placed into the light-protected reaction vessel

of an ozone-chemiluminescence NO analyzer (CLD 77sp, EcoPhysics). The vessel

was maintained at 37 °C, and samples were purged sequentially with either

medical-grade air (normoxia) or nitrogen (hypoxia/near-anoxia). NO generation

was continuously monitored for 5 min following addition of 200

μm NaNO2 (final conc.). This

concentration has been established

as sufficient to support vasorelaxation in vitro, regional

vasodilation in vivo, and nitrosylation and S-nitrosation of

Hb in vitro and in vivo

(10). Aliquots of samples were

collected for protein determination, and all values were normalized to total

protein.

concentration has been established

as sufficient to support vasorelaxation in vitro, regional

vasodilation in vivo, and nitrosylation and S-nitrosation of

Hb in vitro and in vivo

(10). Aliquots of samples were

collected for protein determination, and all values were normalized to total

protein.

In Vivo Studies

Rats were administered 1.0 mg/kg NaNO2, intraperitoneal This

dosing regimen ensures that  equilibrates rapidly across all major organ systems, RBC, and plasma to reach

a global steady-state prior to tissue sampling

(8). Three min after

equilibrates rapidly across all major organ systems, RBC, and plasma to reach

a global steady-state prior to tissue sampling

(8). Three min after

injection acute systemic hypoxia

was induced by cervical dislocation and maintained for 2 min. Normoxic

controls were examined in parallel without subjecting animals to global

hypoxia. In both cases, animals were sacrificed 5 min after

injection acute systemic hypoxia

was induced by cervical dislocation and maintained for 2 min. Normoxic

controls were examined in parallel without subjecting animals to global

hypoxia. In both cases, animals were sacrificed 5 min after

administration. The same in

situ retrograde perfusion technique was performed as for the in

vitro studies above except that the perfusate was air-equilibrated PBS

supplemented with NEM/EDTA (10 mm/2.5 mm) to eliminate

interference by exogenous

administration. The same in

situ retrograde perfusion technique was performed as for the in

vitro studies above except that the perfusate was air-equilibrated PBS

supplemented with NEM/EDTA (10 mm/2.5 mm) to eliminate

interference by exogenous  .

NO-related metabolites following

.

NO-related metabolites following  administration were profiled using previously validated methods

(23,

24). NO metabolites include

S-nitrosothiols (RSNO), N-nitrosamines (RNNO), and

iron-nitrosyls (NO-heme). Quantification of these species employed

group-specific derivatization, denitrosation, and gas-phase chemiluminescence.

administration were profiled using previously validated methods

(23,

24). NO metabolites include

S-nitrosothiols (RSNO), N-nitrosamines (RNNO), and

iron-nitrosyls (NO-heme). Quantification of these species employed

group-specific derivatization, denitrosation, and gas-phase chemiluminescence.

and

and

were quantified by ion

chromatography (ENO-20, Eicom).

were quantified by ion

chromatography (ENO-20, Eicom).

Data Analysis, Presentation, and Modeling

Unless otherwise noted, data are averages ± range from n = 3 individual experiments or means ± S.E. from n ≥ 3, as specified. Where appropriate, statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni post-hoc test. Least-squares regression analysis was used to characterize the slope and goodness-of-fit of model linear associations between data sets. Spearman rank correlation was applied to evaluate data co-variation. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Origin 7.0 and Graph Pad Prism 4.0 were used for the statistical analyses. Modeling data were obtained through numeric integration using Mathematica, with a working precision of 20 digits.

RESULTS

Tissues Readily Take Up  in an

Oxygen-independent

Manner—

in an

Oxygen-independent

Manner— uptake by RBCs,

heart, and liver tissue was assessed under normoxic and hypoxic conditions by

measuring its disappearance from an external medium containing 10

μm

uptake by RBCs,

heart, and liver tissue was assessed under normoxic and hypoxic conditions by

measuring its disappearance from an external medium containing 10

μm  . Because

. Because

concentrations in these tissues are

≪10 μm (8,

23,

24), the initial disappearance

of

concentrations in these tissues are

≪10 μm (8,

23,

24), the initial disappearance

of  from PBS should reflect the flux

of this anion into the cells/tissues. Indeed,

from PBS should reflect the flux

of this anion into the cells/tissues. Indeed,

is taken up at similar rates by RBC

and heart tissue (0.31 μm/min and 0.24 μm/min,

respectively), and rates are roughly comparable under hypoxic conditions

(heart: 0.16 μm/min; RBC: 0.28 μm/min; see

supplemental Fig. S1). Similar data were obtained with liver (not shown). No

is taken up at similar rates by RBC

and heart tissue (0.31 μm/min and 0.24 μm/min,

respectively), and rates are roughly comparable under hypoxic conditions

(heart: 0.16 μm/min; RBC: 0.28 μm/min; see

supplemental Fig. S1). Similar data were obtained with liver (not shown). No

accumulation was seen in the

extracellular medium.

accumulation was seen in the

extracellular medium.

Hypoxia Markedly Potentiates Tissue NO Production from

in Vitro—Under aerobic

conditions, NO production by RBC and blood-free tissues was minimal even in

the presence of 200 μM

in Vitro—Under aerobic

conditions, NO production by RBC and blood-free tissues was minimal even in

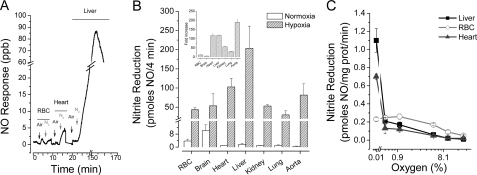

the presence of 200 μM  (Fig. 1A).

Hypoxia/near-anoxia (achieved by N2 purging) dramatically enhanced

NO formation from

(Fig. 1A).

Hypoxia/near-anoxia (achieved by N2 purging) dramatically enhanced

NO formation from  , particularly by

heart, liver, and vascular tissue. NO production by RBC lysate peaked after

∼3 min, whereas NO production by liver homogenate increased to reach

maximal levels after 50–60 min of hypoxia following a brief lag.

Near-anoxic,

, particularly by

heart, liver, and vascular tissue. NO production by RBC lysate peaked after

∼3 min, whereas NO production by liver homogenate increased to reach

maximal levels after 50–60 min of hypoxia following a brief lag.

Near-anoxic,  -dependent NO

production (standardized as mg protein/min) in all tissues surpassed that of

RBC (Fig. 1B). The

2-fold increase in RBC

-dependent NO

production (standardized as mg protein/min) in all tissues surpassed that of

RBC (Fig. 1B). The

2-fold increase in RBC  reduction

from normoxic to near-anoxic conditions is consistent with data previously

reported (10). No NO formation

was observed when 200 μm

reduction

from normoxic to near-anoxic conditions is consistent with data previously

reported (10). No NO formation

was observed when 200 μm

was substituted for

was substituted for

(not shown).

(not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Oxygen dependence of  reduction to NO by different tissues in vitro. A,

original tracing from blood and tissues under normoxic (Air; 21%

O2) and near-anoxic (N2 containing ∼0.01%

O2) conditions. B, quantification of NO production (over 4

min) by RBC and different tissues from

reduction to NO by different tissues in vitro. A,

original tracing from blood and tissues under normoxic (Air; 21%

O2) and near-anoxic (N2 containing ∼0.01%

O2) conditions. B, quantification of NO production (over 4

min) by RBC and different tissues from

(200μm) under

normoxic and near-anoxic conditions. C, oxygen-dependence of

(200μm) under

normoxic and near-anoxic conditions. C, oxygen-dependence of

reduction to NO (n =

3–4 per cell/tissue compartment).

reduction to NO (n =

3–4 per cell/tissue compartment).

NO Generation from  Is Profoundly

Oxygen-dependent—The oxygen-dependence of tissue

Is Profoundly

Oxygen-dependent—The oxygen-dependence of tissue

reductase activity was investigated

by adding 200 μm NaNO2 to liver and heart homogenates

and RBC lysate incubated at various oxygen concentrations (21, 10, 5, 1, 0.5,

and 0%) and monitoring of the resulting NO formation

(Fig. 1C). NO

production from

reductase activity was investigated

by adding 200 μm NaNO2 to liver and heart homogenates

and RBC lysate incubated at various oxygen concentrations (21, 10, 5, 1, 0.5,

and 0%) and monitoring of the resulting NO formation

(Fig. 1C). NO

production from  was maximal under

anoxia. Oxygen proved to be a potent inhibitor of

was maximal under

anoxia. Oxygen proved to be a potent inhibitor of

reduction in liver and heart with

>80% inhibition at 0.5% oxygen. Less pronounced changes in oxygen

dependence were observed with RBC lysate, with maximal rates of NO formation

occurring at ∼1% oxygen.

reduction in liver and heart with

>80% inhibition at 0.5% oxygen. Less pronounced changes in oxygen

dependence were observed with RBC lysate, with maximal rates of NO formation

occurring at ∼1% oxygen.

Acute Hypoxia Potentiates  -dependent

NO Metabolite Formation in Vivo—To extend the above observations to

a more physiological context and to expand on existing observations that

hypoxia reduces endogenous brain

-dependent

NO Metabolite Formation in Vivo—To extend the above observations to

a more physiological context and to expand on existing observations that

hypoxia reduces endogenous brain  stores coincident with RSNO formation

(23), the in vivo

impact of

stores coincident with RSNO formation

(23), the in vivo

impact of  on NO-related metabolite

formation was assessed. To ensure initial

on NO-related metabolite

formation was assessed. To ensure initial

equilibration across all

compartments studied, we followed our previous protocol

(8) and administered to rats a

single intraperitoneal bolus of 1.0 mg/kg NaNO2 3 min prior to

inducing 2 min of global hypoxia. Acute global hypoxia attenuated

equilibration across all

compartments studied, we followed our previous protocol

(8) and administered to rats a

single intraperitoneal bolus of 1.0 mg/kg NaNO2 3 min prior to

inducing 2 min of global hypoxia. Acute global hypoxia attenuated

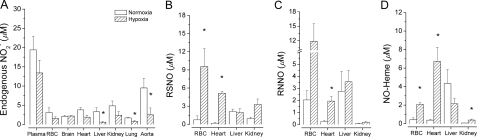

concentrations in heart, liver,

kidney, lung, and aorta (Fig.

2A) and enhanced NO metabolite formation in a tissue- and

product-selective manner (Fig. 2,

B–D). Tissue nitroso/nitrosyl products originated

from

concentrations in heart, liver,

kidney, lung, and aorta (Fig.

2A) and enhanced NO metabolite formation in a tissue- and

product-selective manner (Fig. 2,

B–D). Tissue nitroso/nitrosyl products originated

from  , since their levels under

identical hypoxic conditions were far less (<0.1%) without the supplied

, since their levels under

identical hypoxic conditions were far less (<0.1%) without the supplied

(23). Although each tissue

examined was capable of hypoxia-induced,

(23). Although each tissue

examined was capable of hypoxia-induced,

-dependent NO metabolite formation,

it was most pronounced in liver, heart, and the RBC. The tissue-specificity of

these responses to systemic hypoxia accords with previous demonstrations that

endogenous substrates and the turnover of NO-related oxidative and nitrosative

metabolites vary greatly among tissues

(23,

26). Although there is limited

NO production from

-dependent NO metabolite formation,

it was most pronounced in liver, heart, and the RBC. The tissue-specificity of

these responses to systemic hypoxia accords with previous demonstrations that

endogenous substrates and the turnover of NO-related oxidative and nitrosative

metabolites vary greatly among tissues

(23,

26). Although there is limited

NO production from  by hypoxic RBC

in vitro (Fig. 1), RBC

exhibited the greatest relative RSNO formation during acute hypoxia in

vivo. This finding is consistent with the S-nitrosation and

nitrosylation of hemoglobin (Hb) by

by hypoxic RBC

in vitro (Fig. 1), RBC

exhibited the greatest relative RSNO formation during acute hypoxia in

vivo. This finding is consistent with the S-nitrosation and

nitrosylation of hemoglobin (Hb) by  to form both, SNO-Hb and Hb-NO in vitro and in vivo

(10); indeed, SNO-Hb is

probably generated from circulating

to form both, SNO-Hb and Hb-NO in vitro and in vivo

(10); indeed, SNO-Hb is

probably generated from circulating  without the intermediate liberation of NO within the RBC

(27).

without the intermediate liberation of NO within the RBC

(27).

FIGURE 2.

Increased formation of tissue NO metabolites from

during acute global hypoxia in

vivo. Blood and tissues utilize

during acute global hypoxia in

vivo. Blood and tissues utilize

during global hypoxia in

vivo (A) to generate NO-related products including

S-nitrosothiols (RSNO) (B), N-nitrosamines (RNNO)

(C), and iron nitrosyls (NO-heme) (D). (n = 3); *,

p < 0.05 versus normoxia.

during global hypoxia in

vivo (A) to generate NO-related products including

S-nitrosothiols (RSNO) (B), N-nitrosamines (RNNO)

(C), and iron nitrosyls (NO-heme) (D). (n = 3); *,

p < 0.05 versus normoxia.

Kinetics and Concentration-dependence of

Reduction to NO—Liver effectively

generates NO from

Reduction to NO—Liver effectively

generates NO from  (Fig. 1), has a multiplicity of

potential reductases that can be pharmacologically investigated, and is

readily available and easily perfused free of blood. Accordingly, liver was

used to characterize more comprehensively the kinetics and chemistry of NO

production from

(Fig. 1), has a multiplicity of

potential reductases that can be pharmacologically investigated, and is

readily available and easily perfused free of blood. Accordingly, liver was

used to characterize more comprehensively the kinetics and chemistry of NO

production from  in tissue. The

in tissue. The

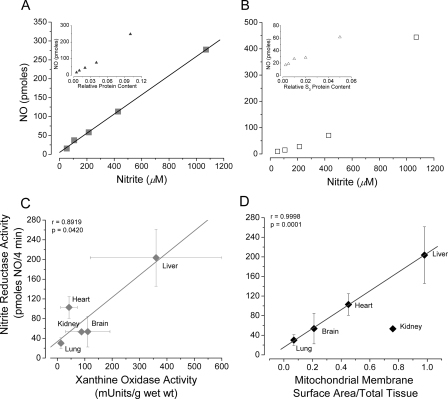

reductase activity of anoxic whole

liver homogenate was linearly dependent upon the concentration of supplied

reductase activity of anoxic whole

liver homogenate was linearly dependent upon the concentration of supplied

(25–1000 μm)

and, to a lesser extent, the amount of tissue protein employed

(Fig. 3A). Because the

generation of NO was measured over 4 min in each case and therefore represents

the initial rate of NO formation, this observation suggests that whole liver

homogenate grossly conforms to first order kinetics with respect to

(25–1000 μm)

and, to a lesser extent, the amount of tissue protein employed

(Fig. 3A). Because the

generation of NO was measured over 4 min in each case and therefore represents

the initial rate of NO formation, this observation suggests that whole liver

homogenate grossly conforms to first order kinetics with respect to

and, to a lesser extent, tissue

protein concentration. In contrast to the results obtained with whole liver

homogenate, no strict linearity was evident in the cytosolic fraction (S3)

between NO formation and

and, to a lesser extent, tissue

protein concentration. In contrast to the results obtained with whole liver

homogenate, no strict linearity was evident in the cytosolic fraction (S3)

between NO formation and  concentration, although the dependence upon protein concentration was similar

to that in whole liver homogenate (Fig.

3B).

concentration, although the dependence upon protein concentration was similar

to that in whole liver homogenate (Fig.

3B).

FIGURE 3.

Correlation between NO formation from

in different tissues and putative

in different tissues and putative

reductase activity. A,

apparent linear dependence of

reductase activity. A,

apparent linear dependence of  to NO

conversion by hypoxic whole liver homogenate (25–1000 μm

to NO

conversion by hypoxic whole liver homogenate (25–1000 μm

). Inset, hypoxic NO

production from 200 μm

). Inset, hypoxic NO

production from 200 μm

is not as linearly dependent upon

hepatic protein. B,

is not as linearly dependent upon

hepatic protein. B, and

protein dependence deviate from linearity with the cytosolic fraction.

C, significant correlation exists between hypoxic

and

protein dependence deviate from linearity with the cytosolic fraction.

C, significant correlation exists between hypoxic

reductase activity and tissue XOR

activity (r = 0.892, p = 0.042). The correlation between

hypoxic

reductase activity and tissue XOR

activity (r = 0.892, p = 0.042). The correlation between

hypoxic  reductase activity and

mitochondrial inner surface area (D) is more striking, except for

kidney (r = 0.9998, p = 0.0001).

reductase activity and

mitochondrial inner surface area (D) is more striking, except for

kidney (r = 0.9998, p = 0.0001).

Reduction to NO Requires Enzymatic

Activity—To probe the involvement of enzymatic processes in hypoxic

NO formation, aliquots of liver homogenate were subjected to heat

pretreatment. Exposure of liver homogenate for 60 min to 56 or 80 °C

inhibited

Reduction to NO Requires Enzymatic

Activity—To probe the involvement of enzymatic processes in hypoxic

NO formation, aliquots of liver homogenate were subjected to heat

pretreatment. Exposure of liver homogenate for 60 min to 56 or 80 °C

inhibited  reductase activity by 72

and >90%, respectively, relative to control, unheated tissue samples. These

results are consistent with the conclusion that thermolabile enzymes mediate

the majority of hypoxic

reductase activity by 72

and >90%, respectively, relative to control, unheated tissue samples. These

results are consistent with the conclusion that thermolabile enzymes mediate

the majority of hypoxic  reduction

to NO, either directly or indirectly (e.g. by modulating reducing

equivalent supply).

reduction

to NO, either directly or indirectly (e.g. by modulating reducing

equivalent supply).

Putative Cellular  Reductases—To gain insight into potential mechanisms of tissue

Reductases—To gain insight into potential mechanisms of tissue

reduction,

reduction,

-dependent NO production was

quantified as a function of reported literature values for tissue XOR activity

(28)

(Fig. 3C) and/or

maximal oxidative phosphorylative capacity, indexed by Hulbert and Else

(29) as inner mitochondrial

membrane surface area (Fig.

3D). All tissues except kidney evidenced a strong linear

relationship between tissue

-dependent NO production was

quantified as a function of reported literature values for tissue XOR activity

(28)

(Fig. 3C) and/or

maximal oxidative phosphorylative capacity, indexed by Hulbert and Else

(29) as inner mitochondrial

membrane surface area (Fig.

3D). All tissues except kidney evidenced a strong linear

relationship between tissue  reductase activity as a function of mitochondrial membrane surface area

(Fig. 3D). Because

cytochrome oxidase activity directly correlates with inner mitochondrial

membrane surface area (29), a

linear relationship also exists between hypoxic tissue

reductase activity as a function of mitochondrial membrane surface area

(Fig. 3D). Because

cytochrome oxidase activity directly correlates with inner mitochondrial

membrane surface area (29), a

linear relationship also exists between hypoxic tissue

reduction to NO and cytochrome

oxidase activity. Rat kidney (especially, renal medulla) deviates

substantially from other organs in its greater dependence upon glycolysis

versus oxidative phosphorylation for ATP production

(30). Kidney

reduction to NO and cytochrome

oxidase activity. Rat kidney (especially, renal medulla) deviates

substantially from other organs in its greater dependence upon glycolysis

versus oxidative phosphorylation for ATP production

(30). Kidney

reductive capacity may be limited

to prevent NO-mediated mitochondrial inhibition due to the relatively high

local

reductive capacity may be limited

to prevent NO-mediated mitochondrial inhibition due to the relatively high

local  concentrations that arise

during renal anion filtration/secretion. The relatively weak relationship in

the kidney between

concentrations that arise

during renal anion filtration/secretion. The relatively weak relationship in

the kidney between  reductase

activity and maximal oxidative metabolic capacity

(Fig. 3D) supports the

overall concept of a robust interrelationship between oxidative intermediary

metabolism and

reductase

activity and maximal oxidative metabolic capacity

(Fig. 3D) supports the

overall concept of a robust interrelationship between oxidative intermediary

metabolism and  -dependent NO

formation. Mitochondrial inner surface area, cytochrome oxidase, and/or oxygen

utilization capacity reflect quantifiable, correlative parameters of this

interrelationship.

-dependent NO

formation. Mitochondrial inner surface area, cytochrome oxidase, and/or oxygen

utilization capacity reflect quantifiable, correlative parameters of this

interrelationship.

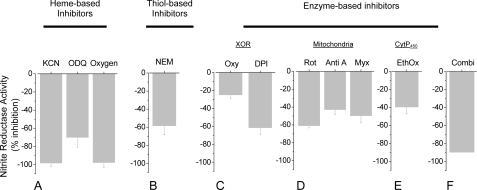

Chemical Sensitivity of  -dependent NO

Formation in Vitro—To evaluate further the enzyme systems that may

contribute to the formation of NO from

-dependent NO

Formation in Vitro—To evaluate further the enzyme systems that may

contribute to the formation of NO from

in hypoxic liver, tissue samples

were probed with an extensive array of inhibitors to target discrete enzymatic

activities (supplemental Table S1). Cyanide and oxygen were among the most

effective inhibitors, eliciting a concentration-dependent reduction of maximal

NO formation from

in hypoxic liver, tissue samples

were probed with an extensive array of inhibitors to target discrete enzymatic

activities (supplemental Table S1). Cyanide and oxygen were among the most

effective inhibitors, eliciting a concentration-dependent reduction of maximal

NO formation from  that reached

>95% (Fig. 4A),

suggesting the crucial involvement of metalloproteins and an oxygen-sensitive

component. The heme-oxidant oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ) is also a

potent inhibitor (70% at 10 mm)

(Fig. 4A), suggesting

the involvement of reduced hemes. Similar inhibition by the thiol alkylator

N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) (∼60% at 10 mm)

(Fig. 4B) implies a role for

free thiols in liver

that reached

>95% (Fig. 4A),

suggesting the crucial involvement of metalloproteins and an oxygen-sensitive

component. The heme-oxidant oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ) is also a

potent inhibitor (70% at 10 mm)

(Fig. 4A), suggesting

the involvement of reduced hemes. Similar inhibition by the thiol alkylator

N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) (∼60% at 10 mm)

(Fig. 4B) implies a role for

free thiols in liver  reductase

activity under hypoxia. The xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) inhibitor,

oxypurinol (Oxy), partially (by 25%) inhibited hypoxic

reductase

activity under hypoxia. The xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) inhibitor,

oxypurinol (Oxy), partially (by 25%) inhibited hypoxic

reduction, whereas preincubation of

liver homogenate with the flavin inhibitor, diphenyleneiodonium (DPI),

inhibited by as much as 62% (Fig.

4C), in further support of a role for XOR and/or

mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2). The inhibitory effects of

cyanide and DPI are also consistent with an involvement of mitochondrial

respiratory complexes in

reduction, whereas preincubation of

liver homogenate with the flavin inhibitor, diphenyleneiodonium (DPI),

inhibited by as much as 62% (Fig.

4C), in further support of a role for XOR and/or

mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2). The inhibitory effects of

cyanide and DPI are also consistent with an involvement of mitochondrial

respiratory complexes in  reduction.

Other inhibitors of mitochondrial respiration (i.e. rotenone (Rot),

antimycin A (Anti A), and myxothiazole (Myx)) also attenuated hypoxic NO

formation from

reduction.

Other inhibitors of mitochondrial respiration (i.e. rotenone (Rot),

antimycin A (Anti A), and myxothiazole (Myx)) also attenuated hypoxic NO

formation from  (Fig. 4D). Suppression

of NO formation by ethoxyresorufin (EthOx)

(Fig. 4E) implicates

yet another mitochondrial and/or microsomal route of hypoxic

(Fig. 4D). Suppression

of NO formation by ethoxyresorufin (EthOx)

(Fig. 4E) implicates

yet another mitochondrial and/or microsomal route of hypoxic

reduction: EthOx selectively

inhibits the cytochrome P450 CYP1A1, which is found in mitochondria

and endoplasmic reticulum. The nonselective cytochrome P450

monooxygenase inhibitor proadifen was without effect. The aggregate inhibitor

data allow conclusion that

reduction: EthOx selectively

inhibits the cytochrome P450 CYP1A1, which is found in mitochondria

and endoplasmic reticulum. The nonselective cytochrome P450

monooxygenase inhibitor proadifen was without effect. The aggregate inhibitor

data allow conclusion that  conversion to NO by hypoxic liver tissue is a multifactorial, metalloprotein-

and thiol-dependent process, which is highly susceptible to inhibition by

oxygen and involves XOR, several mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes,

and cytochrome P450. In further support of the cooperative nature

of this process, the combination of the three inhibitors rotenone, EthOx, and

DPI (Combi) inhibited hypoxic

conversion to NO by hypoxic liver tissue is a multifactorial, metalloprotein-

and thiol-dependent process, which is highly susceptible to inhibition by

oxygen and involves XOR, several mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes,

and cytochrome P450. In further support of the cooperative nature

of this process, the combination of the three inhibitors rotenone, EthOx, and

DPI (Combi) inhibited hypoxic  reduction to NO to an extent greater than the inhibition elicited by each

agent alone (Fig.

4F).

reduction to NO to an extent greater than the inhibition elicited by each

agent alone (Fig.

4F).

FIGURE 4.

Chemical sensitivity of hypoxic

reduction to NO. Exposure of

whole liver homogenate to a variety of inhibitors targeting various cellular

components (see supplementary Table S1 for details) shows that hypoxic

reduction to NO. Exposure of

whole liver homogenate to a variety of inhibitors targeting various cellular

components (see supplementary Table S1 for details) shows that hypoxic

reduction to NO is carried out by

multiple enzymatic routes. Inhibitors for XOR, mitochondrial respiration,

hemes, and thiols all attenuate hypoxic

reduction to NO is carried out by

multiple enzymatic routes. Inhibitors for XOR, mitochondrial respiration,

hemes, and thiols all attenuate hypoxic

to NO conversion to varying

degrees, with virtually complete inhibition by KCN and oxygen implicating

metalloproteins as being most critical to the process (n = 3).

(Oxygen: 21%, medical-grade air; Oxy: oxypurinol;

EthOxy: ethoxyresorufin; Rot: rotenone; Anti A:

antimycin A; Myx: myxathiozole; Combi: inhibitor mixture

containing DPI, ethoxyresorufin, and rotenone).

to NO conversion to varying

degrees, with virtually complete inhibition by KCN and oxygen implicating

metalloproteins as being most critical to the process (n = 3).

(Oxygen: 21%, medical-grade air; Oxy: oxypurinol;

EthOxy: ethoxyresorufin; Rot: rotenone; Anti A:

antimycin A; Myx: myxathiozole; Combi: inhibitor mixture

containing DPI, ethoxyresorufin, and rotenone).

To investigate whether tissue  reductase activity is sensitive to tissue oxidation state, ferricyanide (5

mm) was introduced prior to or after

reductase activity is sensitive to tissue oxidation state, ferricyanide (5

mm) was introduced prior to or after

addition. Ferricyanide treatment

pre-oxidizes potential reductases (e.g. ferrous hemeproteins) to

diminish their reductase activity; ferricyanide exposure following

addition. Ferricyanide treatment

pre-oxidizes potential reductases (e.g. ferrous hemeproteins) to

diminish their reductase activity; ferricyanide exposure following

addition promotes the release of NO

equivalents bound to ferrous hemeproteins. As reported by Shiva et

al. (20) for heart

homogenate, ferricyanide treatment significantly alters hepatic

addition promotes the release of NO

equivalents bound to ferrous hemeproteins. As reported by Shiva et

al. (20) for heart

homogenate, ferricyanide treatment significantly alters hepatic

reductase activity (see

supplemental information), implicating the involvement of redox-sensitive heme

complexes. However, the enhanced reductase activity in the oxidized state

seems to contradict any simple conception of a ferrous heme-based

reductase activity (see

supplemental information), implicating the involvement of redox-sensitive heme

complexes. However, the enhanced reductase activity in the oxidized state

seems to contradict any simple conception of a ferrous heme-based

reductase. Addition of ferricyanide

after incubation with

reductase. Addition of ferricyanide

after incubation with  under hypoxic

(but not aerobic) conditions leads to large bursts of NO formation by liver

homogenates. The sudden rise and exponential decay of the chemiluminescence

signal is consistent with a reaction of ferricyanide with ferrous heme

nitrosyl complexes (31). A

comparison of the experimental data with mathematical models (see supplemental

information) simulating NO generation from

under hypoxic

(but not aerobic) conditions leads to large bursts of NO formation by liver

homogenates. The sudden rise and exponential decay of the chemiluminescence

signal is consistent with a reaction of ferricyanide with ferrous heme

nitrosyl complexes (31). A

comparison of the experimental data with mathematical models (see supplemental

information) simulating NO generation from

reduction and trapping by hemes

predicts that the majority of nitrosyl products formed from

reduction and trapping by hemes

predicts that the majority of nitrosyl products formed from

must be derived without the

intermediacy of free NO.

must be derived without the

intermediacy of free NO.

Multiple Intracellular Compartments Contribute to Hypoxic NO Production

from  —To complement the inhibitor

studies performed in whole liver homogenate and gain insight into the

subcellular sites of hypoxic

—To complement the inhibitor

studies performed in whole liver homogenate and gain insight into the

subcellular sites of hypoxic  reductase activity in this organ, blood-free hepatic tissue was fractionated

into mitochondrial, cytosolic, and microsomal fractions by standard

differential centrifugation. The ability of each individual subfraction to

form NO when supplied with 200 μm NaNO2 was examined

during a 4-min incubation at 37 °C with nitrogen. Hepatic

reductase activity in this organ, blood-free hepatic tissue was fractionated

into mitochondrial, cytosolic, and microsomal fractions by standard

differential centrifugation. The ability of each individual subfraction to

form NO when supplied with 200 μm NaNO2 was examined

during a 4-min incubation at 37 °C with nitrogen. Hepatic

reductase activity under hypoxia

was distributed selectively among the three major liver subfractions studied,

with microsomes accounting for over half (∼63%) of the total activity

(Fig. 5A) when

adjusted for compartmental fractional yield. Cytosolic NO formation from

reductase activity under hypoxia

was distributed selectively among the three major liver subfractions studied,

with microsomes accounting for over half (∼63%) of the total activity

(Fig. 5A) when

adjusted for compartmental fractional yield. Cytosolic NO formation from

during hypoxia was sensitive to 100

μm oxypurinol (52% inhibition), suggesting the involvement of

XOR (and possibly other soluble proteins). Interestingly, subcellular

fractions produced more NO than whole liver homogenate

(Fig. 5B), implying

that, when liver subfractions are combined, some consume NO and/or inhibit NO

production by others. Consistent with the inhibitor studies, hypoxic

conversion of

during hypoxia was sensitive to 100

μm oxypurinol (52% inhibition), suggesting the involvement of

XOR (and possibly other soluble proteins). Interestingly, subcellular

fractions produced more NO than whole liver homogenate

(Fig. 5B), implying

that, when liver subfractions are combined, some consume NO and/or inhibit NO

production by others. Consistent with the inhibitor studies, hypoxic

conversion of  to NO by liver

mitochondria was stimulated (110 ± 31%) by 100 μm NADH

(and >70% by 100 μm NADPH)

(Fig. 5C), the

electron source for the mitochondrial respiratory chain, which can increase

the reduction potential of the system. The reason for the inhibition of

to NO by liver

mitochondria was stimulated (110 ± 31%) by 100 μm NADH

(and >70% by 100 μm NADPH)

(Fig. 5C), the

electron source for the mitochondrial respiratory chain, which can increase

the reduction potential of the system. The reason for the inhibition of

reduction in cytosol and microsomes

by NADPH is not obvious, but may reflect heightened consumption of NADPH by

non-mitochondrial anabolic pathways (e.g. cytosolic fatty acid

synthesis) stimulated by the added pyridine nucleotide. As a corollary to our

observation that hepatic microsomes significantly contribute to nitrite

reductase activity, spectral, and chemiluminescence studies confirm the

sequence of microsomal nitrite binding, formation of a Cyt P450

iron-nitrosyl complex and NO release (supplemental information and

Fig. 5D).

reduction in cytosol and microsomes

by NADPH is not obvious, but may reflect heightened consumption of NADPH by

non-mitochondrial anabolic pathways (e.g. cytosolic fatty acid

synthesis) stimulated by the added pyridine nucleotide. As a corollary to our

observation that hepatic microsomes significantly contribute to nitrite

reductase activity, spectral, and chemiluminescence studies confirm the

sequence of microsomal nitrite binding, formation of a Cyt P450

iron-nitrosyl complex and NO release (supplemental information and

Fig. 5D).

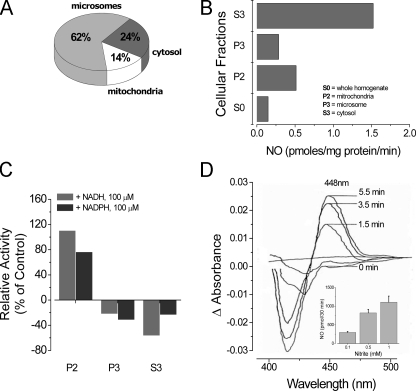

FIGURE 5.

Relative subcellular distribution and activity of hypoxic

reduction to NO within liver

tissue. A, subcellular fractionation of hepatic tissue reveals

that

reduction to NO within liver

tissue. A, subcellular fractionation of hepatic tissue reveals

that  -dependent NO formation is

nonuniformly distributed among cell compartments. B, specific

activity of

-dependent NO formation is

nonuniformly distributed among cell compartments. B, specific

activity of  reduction to NO within

subcellular fractions reveals that both cytosolic (S3) and mitochondrial (P2)

compartments exhibit the highest specific

reduction to NO within

subcellular fractions reveals that both cytosolic (S3) and mitochondrial (P2)

compartments exhibit the highest specific

reductase activities. C,

pyridine nucleotide (NAD(P)H, 100 μm) enhances hypoxia-induced

reductase activities. C,

pyridine nucleotide (NAD(P)H, 100 μm) enhances hypoxia-induced

reduction to NO (70–110%

increase from control) within the mitochondrial fraction (n = 2).

D, upon supplying

reduction to NO (70–110%

increase from control) within the mitochondrial fraction (n = 2).

D, upon supplying  to

microsomal fractions (containing cyt P450), rapid formation of an

iron-nitrite complex precedes formation of an ironnitrosyl

(λmax = 448 nm) prior to release of NO. Inset,

microsomal NO generation from

to

microsomal fractions (containing cyt P450), rapid formation of an

iron-nitrite complex precedes formation of an ironnitrosyl

(λmax = 448 nm) prior to release of NO. Inset,

microsomal NO generation from  is

concentration-dependent. Increasing

is

concentration-dependent. Increasing  (0.1–1.0 mm) in hepatic microsomes potentiates NO formation

(n = 3).

(0.1–1.0 mm) in hepatic microsomes potentiates NO formation

(n = 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study provides intriguing new insights into the

oxygen-dependent processing of nitrite by mammalian tissues. The major

findings are as follows: (a)

is transported into cells rapidly

irrespective of ambient oxygen tension. (b) While

is transported into cells rapidly

irrespective of ambient oxygen tension. (b) While

bioconversion to NO in

vitro is limited under aerobic conditions, all tissues (especially the

vasculature) readily convert

bioconversion to NO in

vitro is limited under aerobic conditions, all tissues (especially the

vasculature) readily convert  to NO

during hypoxia, and this is accompanied by nitrosation and nitrosylation of

cell constituents. (c) This pattern of

to NO

during hypoxia, and this is accompanied by nitrosation and nitrosylation of

cell constituents. (c) This pattern of

bioconversion to NO-related

signaling products is recapitulated in vivo.(d) Although

tissue

bioconversion to NO-related

signaling products is recapitulated in vivo.(d) Although

tissue  reduction may be facilitated

by non-enzymatic (e.g. disproportionation) and enzymatic mechanisms,

tissue

reduction may be facilitated

by non-enzymatic (e.g. disproportionation) and enzymatic mechanisms,

tissue  reductase activity is

largely (>80%) heat labile, suggesting that enzymatic mechanisms

predominate. (e) The kinetics of NO generation from

reductase activity is

largely (>80%) heat labile, suggesting that enzymatic mechanisms

predominate. (e) The kinetics of NO generation from

appears to be first-order with

respect to

appears to be first-order with

respect to  concentration, but do

not obey simple first-order kinetics with respect to protein concentration.

Hepatic and cardiac

concentration, but do

not obey simple first-order kinetics with respect to protein concentration.

Hepatic and cardiac  -dependent NO

production under hypoxia commences after a delay and is sustained for a

prolonged period of time. (f) Tissue

-dependent NO

production under hypoxia commences after a delay and is sustained for a

prolonged period of time. (f) Tissue

reductase activity is associated

with mitochondrial indices of oxidative phosphorylative capacity. (g)

Inhibitor and subfractionation studies suggest that tissue

reductase activity is associated

with mitochondrial indices of oxidative phosphorylative capacity. (g)

Inhibitor and subfractionation studies suggest that tissue

conversion to NO is multifactorial,

and

conversion to NO is multifactorial,

and  reductase activity is

distributed throughout different cell compartments. In liver, microsomal Cyt

P450 moieties appear to be the dominant reductases, with

significant contributions from mitochondria and cytosol (i.e. XOR).

(h) Ferricyanide and modeling studies demonstrate that

reductase activity is

distributed throughout different cell compartments. In liver, microsomal Cyt

P450 moieties appear to be the dominant reductases, with

significant contributions from mitochondria and cytosol (i.e. XOR).

(h) Ferricyanide and modeling studies demonstrate that

bioconversion under hypoxic

conditions leads to the formation of nitrosyl products largely without the

intermediacy of free NO.

bioconversion under hypoxic

conditions leads to the formation of nitrosyl products largely without the

intermediacy of free NO.

The proposal that hypoxic vasodilation is a result of RBC-dependent

conversion to NO

(6,

10,

18,

19,

21,

22) proved to be a stimulus

for investigating

conversion to NO

(6,

10,

18,

19,

21,

22) proved to be a stimulus

for investigating  bioconversion. We

(23) and others

(15) have offered some initial

characterization of

bioconversion. We

(23) and others

(15) have offered some initial

characterization of  metabolism in

tissues. Increasing recognition of the biological significance of

metabolism in

tissues. Increasing recognition of the biological significance of

and its ubiquitous presence in

mammalian systems (8) mandates

further detailing of the elusive mechanisms through which

and its ubiquitous presence in

mammalian systems (8) mandates

further detailing of the elusive mechanisms through which

is converted to NO and, perhaps,

bioactive NO metabolites. Our present results and those of others

(15) suggest that, at

physiological

is converted to NO and, perhaps,

bioactive NO metabolites. Our present results and those of others

(15) suggest that, at

physiological  levels, hypoxic RBC

do not liberate significant amounts of NO. Instead, vascular tissue appears to

have the greatest capacity to generate NO from

levels, hypoxic RBC

do not liberate significant amounts of NO. Instead, vascular tissue appears to

have the greatest capacity to generate NO from

. We now show that hypoxic

. We now show that hypoxic

reductase activity in tissues is

accompanied by the nitrosation and nitrosylation of cellular targets,

suggesting that some of the resulting NO metabolites may represent

reductase activity in tissues is

accompanied by the nitrosation and nitrosylation of cellular targets,

suggesting that some of the resulting NO metabolites may represent

-related tissue effectors of (or

markers for) hypoxic signaling.

-related tissue effectors of (or

markers for) hypoxic signaling.

Formation of NO from  is an

inefficient process on the order of 0.05 nmol/h/g wet tissue/μm

is an

inefficient process on the order of 0.05 nmol/h/g wet tissue/μm

in liver and heart, with most of

the reductase activity being thermolabile (i.e. enzymatic)

(15). Accordingly, in tissues

such as liver and heart with

in liver and heart, with most of

the reductase activity being thermolabile (i.e. enzymatic)

(15). Accordingly, in tissues

such as liver and heart with  at a

steady-state concentration of ∼500 nm

(8,

23,

24), the expected NO

production rate would be 0.025 μmol/kg/h. The average rate of whole body NO

production in rats and humans is significantly greater, ∼1 μmol/kg/h

(32). Tissues with higher

at a

steady-state concentration of ∼500 nm

(8,

23,

24), the expected NO

production rate would be 0.025 μmol/kg/h. The average rate of whole body NO

production in rats and humans is significantly greater, ∼1 μmol/kg/h

(32). Tissues with higher

concentrations such as aorta

(∼20 μm

concentrations such as aorta

(∼20 μm  ) and with

rates of

) and with

rates of  conversion to NO at least

twice that of the heart or liver, the NO production under hypoxic conditions

could reach ∼2 μmol/kg/h. It is thus conceivable that intrinsic NO

generation from

conversion to NO at least

twice that of the heart or liver, the NO production under hypoxic conditions

could reach ∼2 μmol/kg/h. It is thus conceivable that intrinsic NO

generation from  may have

significant physiological importance in vascular tissue as an autonomous

mediator of hypoxic vasodilation

(11,

16). Conversely, one might

question how the modest rates of

may have

significant physiological importance in vascular tissue as an autonomous

mediator of hypoxic vasodilation

(11,

16). Conversely, one might

question how the modest rates of

-dependent NO production in heart

and liver could account for the protective effects of

-dependent NO production in heart

and liver could account for the protective effects of

against ischemia-reperfusion injury

in these organs. Relevant insight may be obtained from our ferricyanide

experiment, where the amount of free NO trapped by hemes accounts for only a

small percentage of

against ischemia-reperfusion injury

in these organs. Relevant insight may be obtained from our ferricyanide

experiment, where the amount of free NO trapped by hemes accounts for only a

small percentage of  -derived NO.

This result suggests that the production of free NO from

-derived NO.

This result suggests that the production of free NO from

under hypoxia may represent a

relatively minor component of a potent chemical pathway that generates

bioactive (i.e. tissue-protective) NO metabolites directly from

under hypoxia may represent a

relatively minor component of a potent chemical pathway that generates

bioactive (i.e. tissue-protective) NO metabolites directly from

.

.

Given the well-recognized interplay among oxygen, NO, and the mitochondrial

electron transport chain (ETC) at the interface between tissue oxygen

consumption and oxygen-dependent energy conservation, the mitochondrion is

well-positioned to act as a “metabolic coordinator”

(2,

33). Our observation that

rates of  conversion to NO correlate

robustly with maximal mitochondrial respiratory capacity accords with the

hypothesis that tissue oxygen demand and ambient oxygen concentration are

operationally related through

conversion to NO correlate

robustly with maximal mitochondrial respiratory capacity accords with the

hypothesis that tissue oxygen demand and ambient oxygen concentration are

operationally related through

-dependent NO formation by, or more

provocatively for, the ETC

(12,

34,

35). This link between

-dependent NO formation by, or more

provocatively for, the ETC

(12,

34,

35). This link between

-dependent NO formation and

oxidative intermediary metabolism is further underlined by the notable

exception of renal tissue, the renal medulla relying largely on anaerobic

metabolism (30). While these

observations underscore the significance of mitochondria in

-dependent NO formation and

oxidative intermediary metabolism is further underlined by the notable

exception of renal tissue, the renal medulla relying largely on anaerobic

metabolism (30). While these

observations underscore the significance of mitochondria in

bioconversion, the profile of

bioconversion, the profile of

reductases differs among tissues,

and the mitochondrial compartment does not account for the majority of

reductases differs among tissues,

and the mitochondrial compartment does not account for the majority of

bioconversion. Far greater

subcellular complexity is observed. At least in the liver, our combined

inhibitor and cell-fractionation studies suggest that hepatic

bioconversion. Far greater

subcellular complexity is observed. At least in the liver, our combined

inhibitor and cell-fractionation studies suggest that hepatic

reductase activity occurs in the

cytosol, the mitochondrion (along the ETC), and, predominantly, the microsomes

(Cyt P450), with thiols and metalloproteins playing a crucial

cooperative role. Microsomal heme-containing cytochromes are effective

reductase activity occurs in the

cytosol, the mitochondrion (along the ETC), and, predominantly, the microsomes

(Cyt P450), with thiols and metalloproteins playing a crucial

cooperative role. Microsomal heme-containing cytochromes are effective

reductases

(36,

37), as confirmed by the

spectral studies herein.

reductases

(36,

37), as confirmed by the

spectral studies herein.

Except for oxygen and cyanide, no one agent tested completely inhibited

hypoxic  reduction. However, a

combination of three enzyme inhibitors (rotenone, EthOx, and DPI) virtually

blocked all

reduction. However, a

combination of three enzyme inhibitors (rotenone, EthOx, and DPI) virtually

blocked all  -dependent NO formation

by liver homogenates. These observations are not easily reconciled with those

of Li et al. (15),

who failed to demonstrate any effect of rotenone on

-dependent NO formation

by liver homogenates. These observations are not easily reconciled with those

of Li et al. (15),

who failed to demonstrate any effect of rotenone on

reductase activity and identified

XOR and ALDH2 as important components of the cardiac and hepatic

reductase activity and identified

XOR and ALDH2 as important components of the cardiac and hepatic

reductase system. Inhibitor

nonspecificity undoubtedly accounts for some of these differences: although

raloxifene has been used as an ALDH2 inhibitor

(37), it also has potent

effects on some microsomal Cyt P450 species (e.g. 3A4)

(38). Similarly, DPI is

promiscuous and inhibits a variety of enzymes exhibiting flavin-dependent

electron transfer including XOR, ALDH2, and other oxidoreductases. This

demonstrates the weakness of isolated inhibitor studies and in part explains

why our own inhibitor studies do not entirely accord with cell fractionation

studies. For example, although rotenone inhibited 60% of the

reductase system. Inhibitor

nonspecificity undoubtedly accounts for some of these differences: although

raloxifene has been used as an ALDH2 inhibitor

(37), it also has potent

effects on some microsomal Cyt P450 species (e.g. 3A4)

(38). Similarly, DPI is

promiscuous and inhibits a variety of enzymes exhibiting flavin-dependent

electron transfer including XOR, ALDH2, and other oxidoreductases. This

demonstrates the weakness of isolated inhibitor studies and in part explains

why our own inhibitor studies do not entirely accord with cell fractionation

studies. For example, although rotenone inhibited 60% of the

bioconversion in total liver

homogenate, cell fractionation studies suggest that mitochondria contribute

relatively modestly (14%) to overall hepatic

bioconversion in total liver

homogenate, cell fractionation studies suggest that mitochondria contribute

relatively modestly (14%) to overall hepatic

reductase activity. We reconcile

these observations by recognizing the limitations of inhibitor pharmacology,

the nature of cell fractionation as a methodology that artificially divides a

physiologically integrated, heuristic

reductase activity. We reconcile

these observations by recognizing the limitations of inhibitor pharmacology,

the nature of cell fractionation as a methodology that artificially divides a

physiologically integrated, heuristic

reductase, thereby preventing

cooperative effects, and the potential for the inhibitor itself to enter into

subfraction-selective reactions. Nonetheless, the inhibitor data do indicate

that hepatic “

reductase, thereby preventing

cooperative effects, and the potential for the inhibitor itself to enter into

subfraction-selective reactions. Nonetheless, the inhibitor data do indicate

that hepatic “ reductase” represents a biochemically and spatially complex activity

that involves heme, iron-sulfur cluster, and molybdenum enzymes distributed

among a number of organelles that cooperate to reduce

reductase” represents a biochemically and spatially complex activity

that involves heme, iron-sulfur cluster, and molybdenum enzymes distributed

among a number of organelles that cooperate to reduce

to NO.

to NO.

While there is compelling evidence herein and elsewhere that Hb is unlikely

to contribute significantly to

-dependent NO formation in hypoxia

due to the voracious capacity of deoxy/oxyHb to scavenge free NO, the

significance of heme proteins as intracellular

-dependent NO formation in hypoxia

due to the voracious capacity of deoxy/oxyHb to scavenge free NO, the

significance of heme proteins as intracellular

reductases remains unknown. To

address this issue, we combined the use of ferricyanide (which putatively

oxidizes iron from ferrous to ferric hemes) with modeling to dissect the role

of hemes in hepatic and cardiac

reductases remains unknown. To

address this issue, we combined the use of ferricyanide (which putatively

oxidizes iron from ferrous to ferric hemes) with modeling to dissect the role

of hemes in hepatic and cardiac  reductase activity. Our data suggest that: (a) Ferrous heme moieties

within cells contribute substantially to NO scavenging. (b) Much of

the NO liberated by ferricyanide is likely to have originated from nitrosyl

groups generated directly from

reductase activity. Our data suggest that: (a) Ferrous heme moieties

within cells contribute substantially to NO scavenging. (b) Much of

the NO liberated by ferricyanide is likely to have originated from nitrosyl

groups generated directly from

-dependent nitrosylation.

(c) The enhanced effect on NO formation by ferricyanide pretreatment

reflects either the limited participation of ferrous heme in

-dependent nitrosylation.

(c) The enhanced effect on NO formation by ferricyanide pretreatment

reflects either the limited participation of ferrous heme in

bioconversion or, more likely, a

mixed scavenging and liberating role for ferrous heme. Both the concentrations

and reactivities of the different heme and other reductase moieties

(microsomal, mitochondrial and cytosolic) will determine the net response to

exogenous ferricyanide. NO liberation from microsomal ferrous

cyt-P450 nitrosyls is well-known

(36) and may be

counterbalanced by scavenging from other ferrous heme nitrosyl complexes

slower in releasing NO and the influence of other reductases (e.g.

XOR/ALDH2) (15). Pretreatment

with ferricyanide may alter this balance (possibly across compartments) and

favor early NO liberation. In other tissues (e.g. vasculature) where

the heme profile and ratio of

bioconversion or, more likely, a

mixed scavenging and liberating role for ferrous heme. Both the concentrations

and reactivities of the different heme and other reductase moieties

(microsomal, mitochondrial and cytosolic) will determine the net response to

exogenous ferricyanide. NO liberation from microsomal ferrous

cyt-P450 nitrosyls is well-known

(36) and may be

counterbalanced by scavenging from other ferrous heme nitrosyl complexes

slower in releasing NO and the influence of other reductases (e.g.

XOR/ALDH2) (15). Pretreatment

with ferricyanide may alter this balance (possibly across compartments) and

favor early NO liberation. In other tissues (e.g. vasculature) where

the heme profile and ratio of  to

heme proteins (and the activity of ferri-heme reductases) differ, the impact

of scavenging may be attenuated, and NO release from heme moieties more

profound. Indeed, recent experimental evidence points to a role for heme

moieties in vascular

to

heme proteins (and the activity of ferri-heme reductases) differ, the impact

of scavenging may be attenuated, and NO release from heme moieties more

profound. Indeed, recent experimental evidence points to a role for heme

moieties in vascular  bioconversion

(16).

bioconversion

(16).

Hypoxic  bioconversion to NO is

effected with tissue-selectivity by an involved interplay of heme, iron-sulfur

cluster, and molybdenum-containing enzymes, the nature and ratio of

heme-dependent proteins (and other enzymes),

bioconversion to NO is

effected with tissue-selectivity by an involved interplay of heme, iron-sulfur

cluster, and molybdenum-containing enzymes, the nature and ratio of

heme-dependent proteins (and other enzymes),

and oxygen concentration, and redox

state varying with tissue, time, and ambient conditions. The intricacy of

these interactions and the redundancy exhibited by different

and oxygen concentration, and redox

state varying with tissue, time, and ambient conditions. The intricacy of

these interactions and the redundancy exhibited by different

reducing enzymes in different cell

compartments within tissues raise important questions regarding the biological

role of reductive

reducing enzymes in different cell

compartments within tissues raise important questions regarding the biological

role of reductive  metabolism to NO.

Oxygen-dependent conversion of

metabolism to NO.

Oxygen-dependent conversion of  to

NO renders it more suitable for hypoxic vasodilation

(11) than

l-arginine-driven, NO synthase-mediated hypoxic vasodilation, since

the latter requires oxygen as a co-substrate to produce NO. However, the

identification of redundant

to

NO renders it more suitable for hypoxic vasodilation

(11) than

l-arginine-driven, NO synthase-mediated hypoxic vasodilation, since

the latter requires oxygen as a co-substrate to produce NO. However, the

identification of redundant  reductase activities in diverse tissues with varying functions and the

association of this

reductase activities in diverse tissues with varying functions and the

association of this  bioconversion

with tissue oxidative phosphorylation capacity suggest that the biology of

bioconversion

with tissue oxidative phosphorylation capacity suggest that the biology of

extends well beyond vasodilation

and tissue protection. Based on the evidence presented herein, it is tempting

to speculate that conversion of

extends well beyond vasodilation

and tissue protection. Based on the evidence presented herein, it is tempting

to speculate that conversion of  to

NO is part of a conserved regulatory mechanism that acutely matches oxygen

homeostasis to intermediary metabolism

(37). As well acting directly

on mitochondria (12,

35), the resulting nitrosation

of master transcription factors such as HIF-1α may have a profound

impact on the cellular metabolic milieu

(39). Different tissue

compartments might affect their oxygen-sensing through the common path of

to

NO is part of a conserved regulatory mechanism that acutely matches oxygen

homeostasis to intermediary metabolism

(37). As well acting directly

on mitochondria (12,

35), the resulting nitrosation

of master transcription factors such as HIF-1α may have a profound

impact on the cellular metabolic milieu

(39). Different tissue

compartments might affect their oxygen-sensing through the common path of

conversion to NO. The resulting NO

then acts to modify mitochondrial function and the cellular metabolic and

transcriptional milieu. This hypothetical paradigm represents a tuning

mechanism through which eukaryotic cells might optimize their use of oxygen

and carbon units for maximally efficient energy provision

(2,

33,

35). Whether

conversion to NO. The resulting NO

then acts to modify mitochondrial function and the cellular metabolic and

transcriptional milieu. This hypothetical paradigm represents a tuning

mechanism through which eukaryotic cells might optimize their use of oxygen

and carbon units for maximally efficient energy provision

(2,

33,

35). Whether

is indeed involved in such