Abstract

Gibberellin 2-oxidases (GA2oxs) regulate plant growth by inactivating endogenous bioactive gibberellins (GAs). Two classes of GA2oxs inactivate GAs through 2β-hydroxylation: a larger class of C19 GA2oxs and a smaller class of C20 GA2oxs. In this study, we show that members of the rice (Oryza sativa) GA2ox family are differentially regulated and act in concert or individually to control GA levels during flowering, tillering, and seed germination. Using mutant and transgenic analysis, C20 GA2oxs were shown to play pleiotropic roles regulating rice growth and architecture. In particular, rice overexpressing these GA2oxs exhibited early and increased tillering and adventitious root growth. GA negatively regulated expression of two transcription factors, O. sativa homeobox 1 and TEOSINTE BRANCHED1, which control meristem initiation and axillary bud outgrowth, respectively, and that in turn inhibited tillering. One of three conserved motifs unique to the C20 GA2oxs (motif III) was found to be important for activity of these GA2oxs. Moreover, C20 GA2oxs were found to cause less severe GA-defective phenotypes than C19 GA2oxs. Our studies demonstrate that improvements in plant architecture, such as semidwarfism, increased root systems and higher tiller numbers, could be induced by overexpression of wild-type or modified C20 GA2oxs.

INTRODUCTION

Gibberellins (GAs) are a class of essential hormones controlling a variety of growth and developmental processes during the entire life cycle of plants. Plants defective in GA biosynthesis show typical GA-deficient phenotypes, such as dwarfism, small dark green leaves, prolonged germination dormancy, inhibited root growth, defective flowering, reduced seed production, and male sterility (King and Evans, 2003; Sakamoto et al., 2004; Fleet and Sun, 2005; Tanimoto, 2005; Wang and Li, 2005). Therefore, it is important for plants to produce and maintain optimal levels of bioactive GAs to ensure normal growth and development. The bioactive GAs synthesized by higher plants are GA1, GA3, GA4, and GA7 (Hedden and Phillips, 2000). Most genes encoding enzymes catalyzing GA biosynthesis and catabolism have been identified (Graebe, 1987; Hedden and Phillips, 2000; Olszewski et al., 2002; Sakamoto et al., 2004; Yamaguchi, 2008).

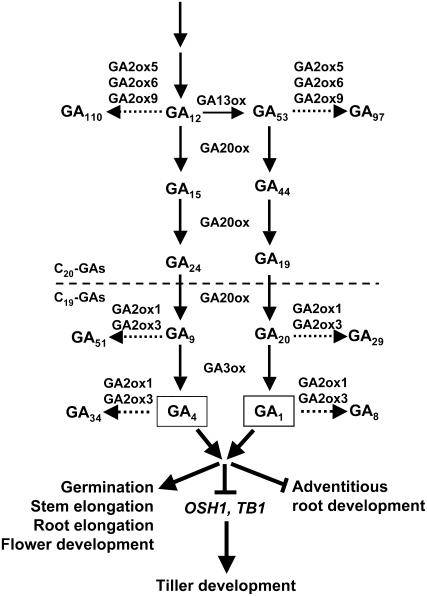

A major catabolic pathway for GAs is initiated by a 2β-hydroxylation reaction catalyzed by GA2ox (Figure 1). C19 GA2oxs identified in various plant species can hydroxylate the C-2 of active C19-GAs (GA1 and GA4) or C19-GA precursors (GA20 and GA9) to produce biologically inactive GAs (GA8, GA34, GA29, and GA51, respectively) (Sakamoto et al., 2004). Recently, three novel C20 GA2oxs, including Arabidopsis thaliana GA2ox7 and GA2ox8 and spinach (Spinacia oleracea) GA2ox3, were found to hydroxylate C20-GA precursors (converting GA12 and GA53 to GA110 and GA97, respectively) but not C19-GAs (Schomburg et al., 2003; Lee and Zeevaart, 2005). The 2β-hydroxylation of C20-GA precursors to GA110 and GA97 renders them unable to be converted to active GAs and thus decreases active GA levels. The class C20 GA2oxs contain three unique and conserved amino acid motifs that are absent in the class C19 GA2oxs (Lee and Zeevaart, 2005).

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of GA Metabolism and Response Pathways.

Conversion of GA12 and GA53 to GA110 and GA97, respectively, by 2β-hydroxylation was demonstrated experimentally only for GA2ox6 in this study. GA2ox5, GA2ox6, and GA2ox9 are proposed to have similar functions due to the presence of three conserved motifs unique to C20 GA2oxs. Inactivation of C19-GA precursors, GA1 and GA4 by the C19 GA2oxs, GA2ox1 and GA2ox3, in rice was demonstrated experimentally (Sakamoto et al., 2001; Sakai et al., 2003). Bioactive GA positively regulates germination, stem and root elongation, and flower development but negatively regulates OSH1 and TB1 that control tillering. GA also negatively regulates adventitious root development.

The physiological functions of GA2oxs have been studied in a variety of plant species. Arabidopsis GA2ox1 and GA2ox2 are expressed in inflorescences and developing siliques, consistent with a role of GA2ox in reducing GA levels and promoting seed dormancy (Thomas et al., 1999). Study of the pea (Pisum sativum) slender mutant, where the SLENDER gene encoding a GA2ox had been knocked out, showed that GA levels increased during germination, and resultant seedlings were hyperelongated (Martin et al., 1999). More recently, a dwarf phenotype was also found to correlate with reduced GA levels in two Arabidopsis mutants in which GA2ox7 and GA2ox8 were activation tagged, and ectopic overexpression of these two genes in transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) led to a dwarf phenotype (Schomburg et al., 2003). These studies demonstrated that GA2oxs are responsible for reducing the level of active GAs in plants. C20 GA2oxs have also been shown to be under photoperiodic control in dicots. In long-day rosette plants, such as spinach, plants grow vegetatively and do not produce a stem under short photoperiod due to deactivation of GA53 to GA97. However, upon transfer to long days, stem elongation and flowering are initiated due to upregulation of GA 20-oxidase (GA20ox), which converts GA53 to GA20 and further to bioactive GA1 by GA 3-oxidase (GA3ox) (Lee and Zeevaart, 2005).

Among the several rice (Oryza sativa) mutant phenotypes caused by GA deficiency, increased tiller growth has been extensively studied. We found that rice mutants overexpressing GA2oxs exhibit early and increased tiller and adventitious root growth. Rice tillering is an important agronomic trait for grain yield, but the mechanism underlying this process remains mostly unclear. The rice tiller is a specialized grain-bearing branch that normally arises from the axil of each leaf and grows independently of the mother stem (culm) with its own adventitious roots. The MONOCULM1 (MOC1) gene, which encodes a GRAS family nuclear protein and is expressed mainly in the axillary buds, is an essential regulator of rice tiller bud formation and development (Li et al., 2003). Two transcription factors, O. sativa homeobox 1(OSH1) and TEOSINTE BRANCHED1 (TB1), have been proposed to act downstream of MOC1 in promoting rice tillering (Li et al., 2003). OSH1 is a rice homeobox gene that is expressed during early embryogenesis and is considered a key regulator of meristem initiation (Sato et al., 1996). Rice TB1 is an ortholog of the maize (Zea mays) tb1 gene that is expressed in axillary meristems and regulates outgrowth of this tissue (Hubbard et al., 2002). In wild-type rice, OSH1 and TB1 mRNAs are detected in both the axillary and apical meristems of tiller bud; expression of both OSH1 and TB1 fell significantly and neither could be detected in meristems in the moc1 mutant, in which only a main culm without any tiller developed due to defects in the formation of tiller buds (Li et al., 2003). However, the rice TB1 has also been shown to function as a negative regulator for lateral branching in rice (Takeda et al., 2003), a function similar to the maize TB1 (Hubbard et al., 2002).

In this study, functions of the rice GA2ox family were characterized through genetic, transgenic, and biochemical approaches, with emphasis on three genes encoding C20 GA2oxs that have three unique and conserved motifs. We showed that C20 GA2oxs play pleotropic roles regulating rice growth and architecture, particularly tillering and root systems that may favor grain yield.

RESULTS

The Rice GA2ox Family

A total of 10 putative GA2oxs (see Supplemental Table 1 online) were identified by BLAST search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR), and Rice Genome Automated Annotation System (RiceGAAS) databases with conserved domains in 2-oxoglutarate–dependent oxygenases, a family of GA-modifying enzymes, and nucleotide sequences of four partially characterized rice GA2oxs (GA2ox1 to GA2ox4) (Sakamoto et al., 2001, 2004; Sakai et al., 2003), and two uncharacterized GA2oxs (GA2ox5 and GA2ox6) (Lee and Zeevaart, 2005). Four other GA2oxs, designated here as GA2ox7 to GA2ox10, were identified in this study.

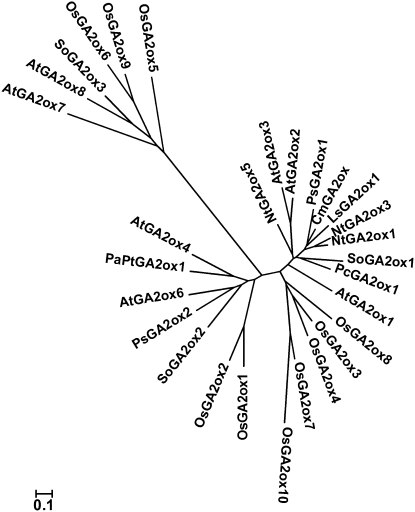

Mapping of GA2oxs in the rice genome sequence revealed that seven GA2oxs clustered on chromosomes 1 and 5 and others located on chromosomes 2, 4, and 7 (see Supplemental Figure 1A online). Amino acid sequence comparison (see Supplemental Table 2 online) generated a phylogenetic tree among the rice GA2ox family (see Supplemental Figure 1B online) and 19 GA2oxs from eight dicot plant species (see Supplemental Table 3 online), which revealed that rice GA2ox5, GA2ox6, and GA2ox9 are more closely related to the Arabidopsis GA2ox7 and GA2ox8 and spinach GA2ox3 (Figure 2). Only these six GA2oxs contain the three unique and conserved motifs (Lee and Zeevaart, 2005) (see Supplemental Figure 2 online).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic Tree Based on the Comparison of Plant GA2oxs.

Amino acid sequences of 29 GA2oxs from nine plant species (see Supplemental Table 3 online). Plant species: At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Cm, Cucurbita maxima; Ls, Lactuca sativa; Nt, Nicotiana sylvestris; Pc, Phaseolus coccineus; PaPt, Populus alba × P. tremuloides; Ps, Pisum sativum; So, Spinacia oleracea. The scale value of 0.1 indicates 0.1 amino acid substitutions per site.

Differential Expression of GA2ox Is Associated with Flower and Tiller Development and Seed Germination

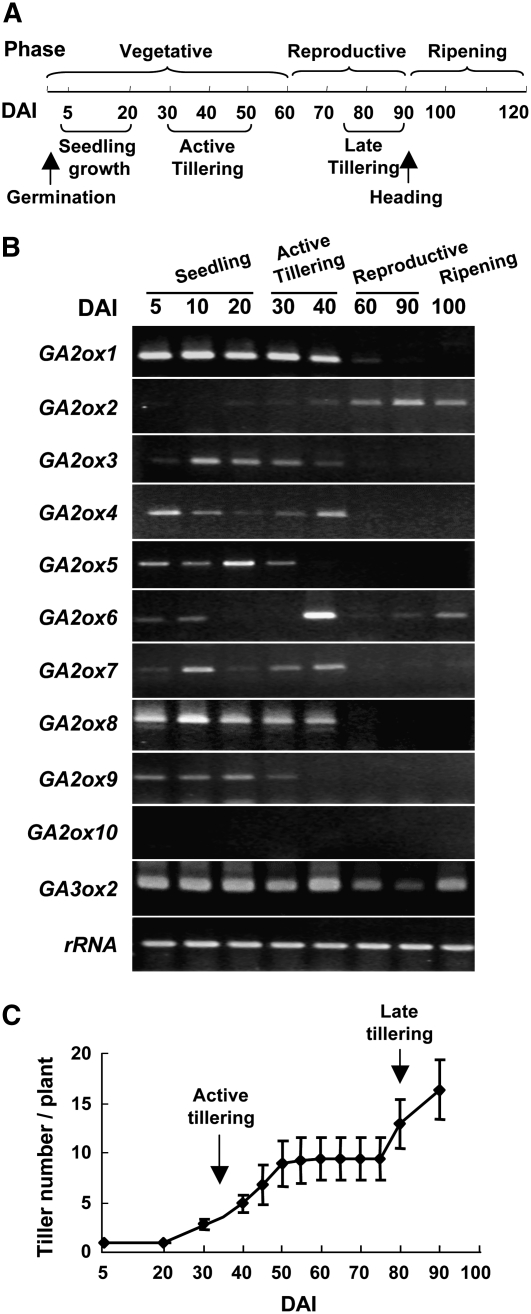

Growth of the rice cultivar Tainung 67 used in this study can be divided into vegetative, reproductive, and ripening phases (Figure 3A). To understand the role that individual GA2oxs may play in rice growth, their temporal expression profiles during the rice life cycle were examined. As leaves have been shown to be a major site of GA biosynthesis (Choi et al., 1995), mRNAs were purified from leaves at different growth stages ranging from 5 to 100 d after imbibition (DAI) and analyzed by RT-PCR. Genes GA2ox1 to GA2ox9 were differentially expressed in leaves, and their expression was also temporally regulated (Figure 3B). However, mRNAs of GA2ox10 were not detected in any tissue at any growth stage, indicating that GA2ox10 could be a pseudogene or its mRNA level was too low to be detected.

Figure 3.

Differential Expression of Two Groups of GA2oxs Regulates Flower and Tiller Development.

(A) Developmental phases during the life cycle of rice. The timeline is measured in days after imbibition (DAI).

(B) Temporal expression patterns of GA2oxs in rice. The last fully expanded leaves were collected from rice plants at different developmental stages. Total RNA was isolated and analyzed by RT-PCR using GA2ox and GA3ox2 gene-specific primers (see Supplemental Table 4 online). The 18S rRNA gene (rRNA) was used as a control.

(C) Tiller development during the life cycle of rice. A total of eight plants were used for counting tiller number, and error bars indicate the se of the mean at each time point.

Based on temporal mRNA accumulation patterns, GA2oxs could be classified into two groups. As can be seen in Figure 3B, for one group excluding GA2ox2 and GA2ox6, accumulation of their mRNAs in leaves was detected prior to the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth phases. By contrast, for another group including GA2ox2 and GA2ox6, their mRNAs accumulated in leaves after the phase transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. GA2ox6 mRNA could also be detected in leaves at early seedling stage and transiently at high level during the active tillering stage. Since expression of most GA2oxs terminated after the active tillering stage, the pattern of tiller growth throughout the rice life cycle was examined. Tiller number increased from 30 to 50 DAI (active tillering), remained constant until 75 DAI, and then increased again until 90 DAI (late tillering) when the experiment was terminated (Figure 3C). Expression of each group of GA2oxs paralleled the active and late tillering stages (cf. Figures 3B with 3C). Except for a slight reduction in the reproductive phase, the expression of GA3ox2, which encodes a GA3ox involved in GA biosynthesis, was not significantly altered in leaves throughout the rice life cycle.

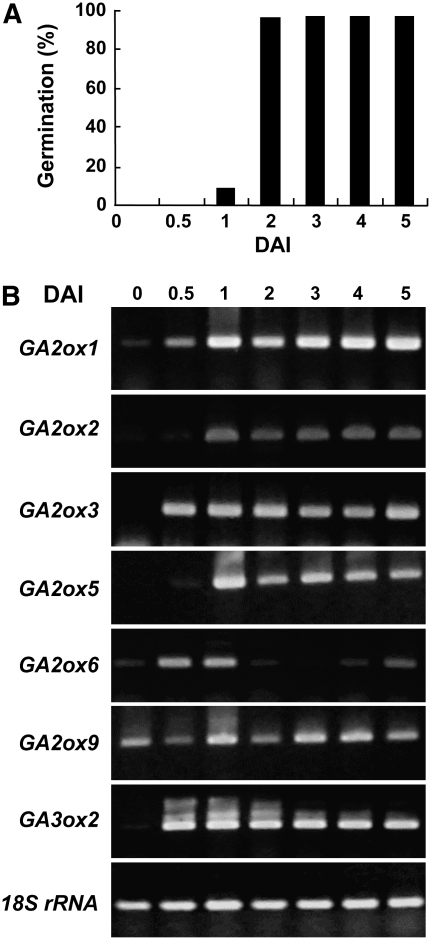

Bioactive GAs are well known for promoting germination, so the role of GA2oxs during germination was studied. Seeds were imbibed for various lengths of time. Germination was observed from 1 DAI and reached almost 100% at 2 DAI (Figure 4A). Total RNA was isolated from embryos after imbibition of seeds, and temporal expression profiles of six GA2oxs were analyzed by RT-PCR. The accumulation of most GA2ox mRNAs was detectable starting from 0 to 1 DAI and maintained at similar levels afterward, except that of GA2ox5 and GA2ox9 was moderately reduced at 2 DAI (Figure 4B). GA2ox6 had a distinct expression pattern, as its mRNA quickly accumulated from 0.5 to 1 DAI and then decreased significantly from 2 to 4 DAI. Low-level accumulation of GA3ox2 mRNA was detected at 0 DAI and then at similarly high levels after 0.5 DAI. This study demonstrated that reduced expression of three C20 GA2oxs seems to correlate with the rapid seed germination at 2 DAI.

Figure 4.

C20 GA2oxs Could Be Responsible for Regulating Seed Germination.

(A) Germination rate of rice seeds reached 100% at 2 DAI.

(B) Expression patterns of GA2oxs in rice seedlings between 0 and ∼5 DAI. Total RNA was isolated from embryos at each time point and analyzed by RT-PCR. The 18S rRNA gene (rRNA) was used as a control.

Functional Analysis of GA2oxs with T-DNA Activation–Tagged Rice Mutants

To study the functions of GA2oxs in rice, we screened for mutants in a T-DNA–tagged rice mutant library, the Taiwan Rice Insertional Mutant (TRIM) library (Hsing et al., 2007). The T-DNA tag used for generating the TRIM library contained multiple cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (CaMV35S) enhancers adjacent to the left border, which activate promoters located near T-DNA insertion sites (Hsing et al., 2007). Two GA2ox-activated dwarf mutants, M77777 and M47191, were identified by a forward genetics screen, and another two mutants, M27337 and M58817, were identified by a reverse genetics screen of the library (Figure 5).

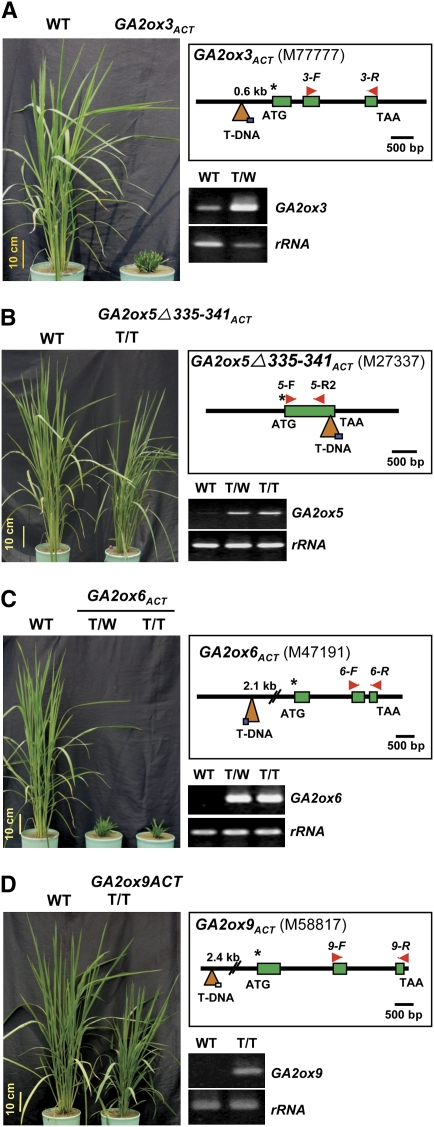

Figure 5.

Severely Dwarfed and Semidwarfed Rice Mutants Obtained by T-DNA Activation Tagging.

(A) The severe dwarf mutant GA2ox3ACT (M77777).

(B) The semidwarf mutant GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT (M27337).

(C) The severe dwarf mutant GA2ox6ACT (M47191).

(D) The semidwarf mutant GA2ox9ACT (M58817).

Accumulation of mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR, with the 18S rRNA gene (rRNA) as a control. T/T and T/W, homozygous and heterozygous mutant, respectively. In the diagram, an asterisk indicates translation start codon, filled box indicates exon, triangle indicates T-DNA, arrowheads indicate position of primers used for RT-PCR analysis, and scale bar represents DNA length for each gene. The box in the triangle indicates the position of the CaMV35S enhancers (next to the left border of T-DNA).

The severe dwarf mutant M77777, designated as GA2ox3ACT, carries a T-DNA insertion at a position 587 bp upstream of the translation start codon of GA2ox3 (Figure 5A). Accumulation of GA2ox3 mRNA was significantly enhanced in the heterozygous mutant. The GA2ox3ACT mutant did not produce seeds and was therefore maintained and propagated vegetatively.

The semidwarf mutant M27337, designated as GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT, carries a T-DNA insertion in the coding region, at a position 23 bp upstream of the translation stop codon of GA2ox5 (Figure 5B). Truncation of GA2ox5 by T-DNA resulted in a loss of seven amino acids at the C terminus of the putative GA2ox5 polypeptide. Accumulation of the truncated GA2ox5 mRNA was significantly enhanced by T-DNA activation tagging in both homozygous and heterozygous mutants, but the semidwarf phenotype was observed only in the homozygous mutant. The GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT homozygous mutant had an average plant height of 90% and produced seeds with an average fertility of 88% of the wild type (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characterization of Rice Mutants and Transgenic Rice Overexpressing GA2oxs

| Traits | Wild Type | GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT (T3)a | GA2ox9ACT (T3) | GA2ox6ACT (T2) | Ubi:GA2ox5 (T1) | Ubi:GA2ox6 (T1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiller number of seedling (18 DAI) | 1.0 ± 0.0b (100)c | 1.8 ± 0.8 (180) | 1.0 ± 0.0 (100) | 2.6 ± 0.5 (260) | 2.7 ± 0.6 (270) | 2.5 ± 0.7 (250) |

| Root length (cm) at 18 DAI | 6.3 ± 0.9 (100) | 15.7 ± 3.2 (249) | 11.0 ± 1.9 (175) | 5.8 ± 1.8 (92) | 6.3 ± 2.1 (100) | 6.6 ± 0.4 (105) |

| Plant height (cm) at 120 DAI | 109.5 ± 2.5 (100) | 98.0 ± 7.1 (90) | 83.2 ± 4.1 (76) | 16.6 ± 1.7 (15) | 16.7 ± 2.8 (15) | 12.1 ± 2.7 (11) |

| Length of leaf bellow flag leaf (cm) at 120 DAI | 49.9 ± 6.0 (100) | 49.6 ± 5.1 (100) | 49.3 ± 3.3 (99) | 12.2 ± 0.9 (24) | 10.6 ± 1.2 (21) | 8.1 ± 0.8 (16) |

| Width of leaf bellow flag leaf (cm) at 120 DAI | 1.64 ± 0.1 (100) | 1.66 ± 0.1 (101) | 1.75 ± 0.2 (107) | 1.51 ± 0.1 (92) | 1.2 ± 0.1 (73) | 1.04 ± 0.1 (63) |

| Heading day (DAI) | 108.7 ± 1.5 | 107.6 ± 1.3 | 107.9 ± 1.0 | > 150 | >150 | >150 |

| Panicle length (cm) | 21.6 ± 2.0 (100) | 20.3 ± 1.5 (94) | 19.7 ± 1.8 (91) | 7.7 ± 1.6 (36) | 5.9 ± 0.8 (27) | 7.5 ± 0.9 (35) |

| Total Tiller number | 11.0 ± 1.8 (100) | 20.3 ± 4.1 (185) | 13.4 ± 2.9 (122) | 17.6 ± 3.7 (160) | NA | 18.8 ± 4.5 (171) |

| Grain weight (g/100 grains) | 2.44 ± 0.1 (100) | 2.04 ± 0.1 (84) | 2.34 ± 0.2 (96) | 1.54 (63) | 1.43 (59) | 1.98 (81) |

| Fertility (%) | 92.6 ± 4.2 (100) | 81.1 ± 5.4 (88) | 85.4 ± 8.9 (92) | 39.5 ± 18 (43) | 27.7 ± 12.0 (30) | 59.4 ± 4.4 (64) |

T1, T2, and T3 in parenthesis indicate generation of mutants.

se; n = 20 for GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT, GA2ox9ACT, and GA2ox6ACT; n = 10 for Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6.

Values in parentheses indicate % of the wild type. NA: not available. DAI: days after imbibition.

The severe dwarf mutant M47191, designated as GA2ox6ACT, carries a T-DNA insertion at a position 2.1 kb upstream of the translation start codon of GA2ox6 (Figure 5C). Accumulation of GA2ox6 mRNA was significantly enhanced by T-DNA activation tagging, and a severe dwarf phenotype was observed in both heterozygous and homozygous mutants. The GA2ox6ACT heterozygous mutant produced seeds with an average fertility of only 43% of the wild type after >5 months of cultivation (Table 1).

The semidwarf mutant M58817, designated as GA2ox9ACT, carries a T-DNA insertion at a position 2.4 kb upstream of the translation start codon of GA2ox9 (Figure 5D). Accumulation of GA2ox9 mRNA was significantly enhanced by T-DNA activation tagging, and the semidwarf phenotype was observed in both the homozygous and heterozygous mutants. The GA2ox9ACT homozygous mutant had an average plant height of 76% and produced seeds with an average fertility of 92% of the wild type (Table 1).

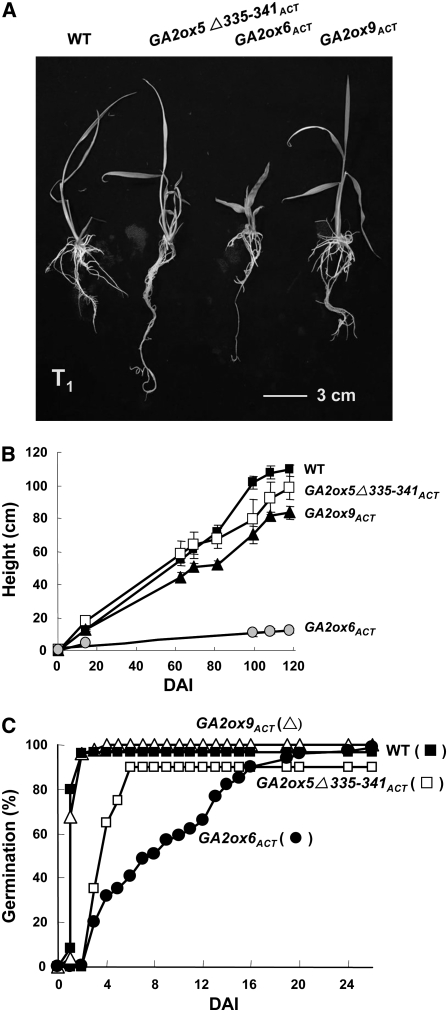

The three activation-tagged mutants, GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT, GA2ox6ACT, and GA2ox9ACT, were further characterized. Progenies displayed the same phenotypes as their parents, with GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT and GA2ox9ACT growing slightly shorter than the wild type, while GA2ox6ACT remained severely dwarfed throughout all growth stages (Figures 6A and 6B). GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT and GA2ox9ACT displayed a normal height but had longer roots and higher tiller numbers than the wild type (Table 1). Other traits significantly altered in the severe dwarf GA2ox6ACT mutant included shorter leaves, later heading date, reduced panicle length, higher tiller numbers, lower grain weight, and lower seed fertility compared with the wild type (Table 1). Germination of GA2ox6ACT seeds was also significantly delayed, as it took 20 d to reach 90% germination rate, while the wild-type and GA2ox9ACT mutant seeds took only 2 d to reach a germination rate of 97 and 98%, respectively (Figure 6C). Germination of GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT seeds was delayed for 4 d to reach a final 88% germination rate (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Overexpression of GA2oxs Has Different Effects on Rice Seed Germination and Seedling Growth.

(A) Morphology of T1 seedlings at 18 DAI.

(B) Seedling heights of GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT and GA2ox9ACT mutants were slightly shorter, while seedlings of GA2ox6ACT were much shorter than the wild type. Heights of eight plants in each line were measured, and error bars indicate the se of the mean at each time point.

(C) Germination rate was normal for the GA2ox9ACT mutant, slightly delayed for the GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT mutant, and significantly delayed for the GA2ox6ACT mutant compared with the wild type. Numbers of seeds for determining germination rates were 154, 50, 156, and 49 for the wild type, GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT, GA2ox6ACT, and GA2ox9ACT, respectively.

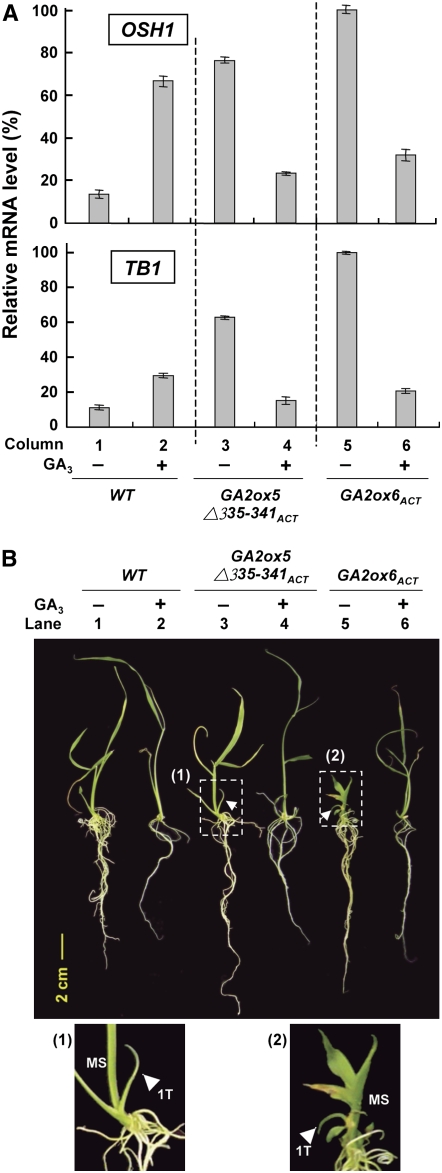

Differential Activity of C20 GA2oxs in Inactivation of GA in Transgenic Rice and Tobacco

To verify the function of GA2ox5 and GA2ox6 in dwarfism of rice plants, full-length cDNAs of GA2ox5 and GA2ox6 were isolated from rice and fused downstream of the maize ubiquitin (Ubi) (Sun and Gubler, 2004) promoter, generating Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6 constructs for rice transformation. More than 30 independent transgenic rice lines were obtained for each construct and all showed dwarf phenotypes with slight variations in final height. The overall phenotypes of Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6 T1 plants were similar to the GA2ox6ACT mutant, except that the seed fertility of Ubi:GA2ox6 transgenic rice (average 64%) was higher than that of Ubi:GA2ox5 transgenic rice (average 30%) (Figures 7A and 7B, Table 1). These results demonstrated that ectopic overexpression of GA2ox5 and GA2ox6 was able to recapitulate the dwarf phenotype in transgenic rice.

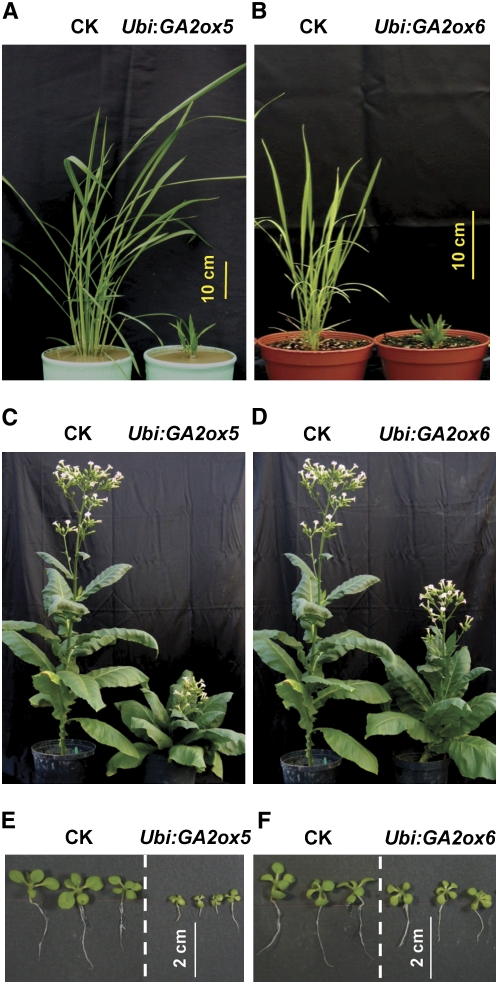

Figure 7.

Overexpression of GA2ox5 in Transgenic Rice and Tobacco Causes More Severe Dwarfism Than Overexpression of GA2ox6.

(A) and (B) Rice transformed with Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6.

(C) to (F) Tobacco transformed with Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6. Transgenic plants showed different degrees of dwarfism compared with the control rice or tobacco transformed with vector only (MS). Photographs of transgenic tobacco were taken at the heading stage ([C] and [D]) and 18 d ([E] and [F]) after sowing of seeds.

To examine whether rice GA2oxs are functional in dicots, Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6 constructs were used for tobacco transformation. Transgenic tobacco showed the same retardation of plant growth but to different extents. While Ubi:GA2ox5 reduced plant height to 32% and seed production to 62% and Ubi:GA2ox6 reduced plant height to 67% of the wild-type tobacco, Ubi:GA2ox6 had no effect on seed production (Figures 7C and 7D, Table 2). The flowering time was delayed ∼2 to 4 weeks for all transgenic tobacco. Growth of hypocotyls and roots of 18-d-old T1 transgenic tobacco seedlings was slightly retarded by overexpression of GA2ox6 but significantly retarded by overexpression of GA2ox5, compared with the wild type (Figures 7E and 7F, Table 2). These studies demonstrated that the two rice GA2oxs have similar functions in monocots and dicots, with GA2ox5 being more potent in inactivation of GA than GA2ox6 in both transgenic rice and tobacco.

Table 2.

Characterization of Transgenic Tobacco Overexpressing Rice GA2ox5 and GA2ox6

| Traits | Wild Type | Ubi:GA2ox5 | Ubi:GA2ox6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root length (mm) at 18 DAI | 20.8 ± 2.7a (100)b | 9.6 ± 4.6 (46) | 17.7 ± 3.6 (85) |

| Hypocotyl length (mm) at 18 DAI | 6.5 ± 0.8 (100) | 3.2 ± 0.6 (49) | 4.6 ± 1.0 (71) |

| Final plant height (cm) | 127.7 ± 4.7 (100) | 41.2 ± 18.9 (32) | 85.3 ± 9.4 (67) |

| Number of leaves to inflorescence | 18.3 ± 0.6 (100) | 20.8 ± 3.3 (114) | 19.0 ± 0.8 (104) |

| Seeds yield (g)/plant | 31.1 ± 0.0 (100) | 19.3 ± 3.4 (62) | 31.3 ± 4.1 (100) |

se with n = 40.

Values in parentheses indicate percentage of the wild type.

Only Shoot, but Not Root, Elongation Is Inhibited by GA Deficiency

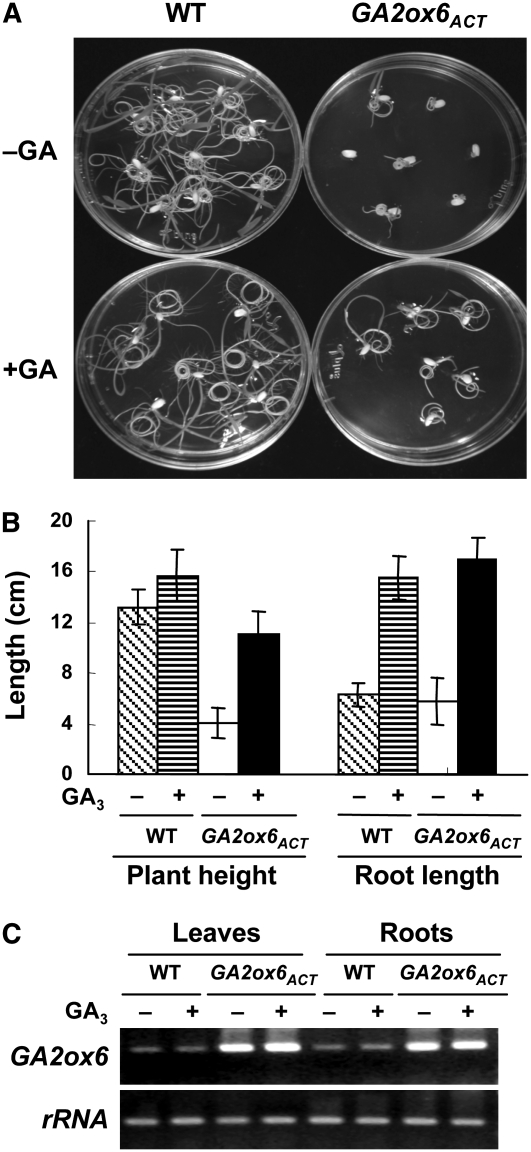

To determine whether the dwarfism of rice mutants overexpressing GA2ox was a result of a reduction of bioactive GAs, GA2ox6ACT mutant seeds were germinated on Murashige and Skoog medium with or without a supplement of 5 μM GA3. Addition of GA3 promoted germination of GA2ox6ACT seeds (Figure 8A), indicating that GA deficiency inhibited GA2ox6ACT mutant seed germination. Plant height of 18-d-old wild-type seedlings was only slightly enhanced by GA3 treatment; by contrast, height of the dwarf GA2ox6ACT mutant seedlings was significantly enhanced by GA3 treatment, with recovery of up to 84% of the wild-type height (Figure 8B). Root lengths of the wild-type and GA2ox6ACT mutant seedlings were similar, and both were effectively enhanced by GA3 treatment (Figure 8B). We noticed that root elongation of GA2ox6ACT was slower initially after germination (Figure 8A, top panel), but it sped up after 6 DAI and became similar to the wild type at 18 DAI (Figure 8B). A similar phenomenon was also observed for root elongation of Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6 transgenic rice. GA2ox6 mRNA in leaves and roots accumulated to a higher level in the GA2ox6ACT mutant than in the wild type, but both were unaffected by GA3 treatment (Figure 8C), indicating that shoot and root elongation was promoted by exogenous GA3 despite high level of GA2ox6 expression. These results show that GA deficiency only inhibited stem, but not root, elongation.

Figure 8.

Only Shoot, but Not Root, Growth Is Inhibited by GA Deficiency.

(A) Treatment with GA3 (5 μM) promoted germination and seedling growth of the GA2ox6ACT mutant (photo taken at 6 DAI).

(B) Overexpression of GA2ox6 in rice mutants reduces shoot, but not root, growth. Treatment with GA3 (5 μM) recovered plant height of the GA2ox6ACT mutant and root growth of both the wild type and mutant. A total of eight plants at 18 DAI were used for measuring plant height and root length, and error bars indicate the se of the mean.

(C) Accumulation of GA2ox6 mRNA in leaves and roots of wild-type and mutant seedlings (at 18 DAI) was not altered by GA3 treatment. The 18S rRNA gene (rRNA) was used as a control. + and −, presence and absence, respectively.

GA Deficiency Promotes Early Tillering and Adventitious Root Growth

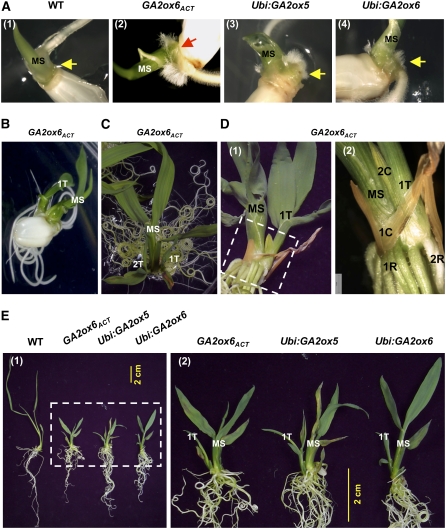

We found that rice mutants with activated GA2oxs or transgenic rice overexpressing GA2oxs formed tillers earlier and in higher number than the wild type. In the GA2ox6ACT mutant and Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6 transgenic seedlings, after growth of the main stem from the embryo at 2 DAI, a subsequent swelling on the embryo surface adjacent to the base of the main stem was observed at 3 DAI (Figure 9A, panels 2 to 4). Then a first and even a second tiller grew out from the swollen embryo surface from 9 to 15 DAI (Figures 9B and 9C). Each tiller grew out from its own coleoptile (Figure 9D), suggesting that these tillers developed independently in the embryo. Both mutant and transgenic seedlings showed early tillering (Figure 9E). The swollen embryo surface, where a tiller was about to emerge, was not observed in the wild type (Figure 9A, panel 1). All new tillers in the mutant and transgenic rice had their own adventitious roots (Figure 9D), a feature similar to tillers from the wild-type plant around 30 DAI. Despite retardation of shoot elongation, total root length of mutant and transgenic seedlings was similar to the wild type at 15 DAI. Quantification of the data also revealed that stem elongation was inhibited, while tiller and root numbers of mutant and transgenic rice at 18 DAI were enhanced, compared with the wild type (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

GA Deficiency Promotes Early Tillering and Adventitious Root Growth.

(A) Swelling on the embryo surface adjacent to the base of the main stem (MS) (positions indicated by arrows) was observed in the GA2ox6ACT mutant and Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6 transgenic rice (panels 2 to 4) but not in the wild type (panel 1) (photos taken at 3 DAI).

(B) First tiller (1T) grew out from the swollen embryo surface of mutant (photo taken at 9 DAI).

(C) First and second tillers (1T and 2T) formed in some seedlings of mutant (photo taken at 15 DAI).

(D) Each tiller grew out of its own coleoptile, and all new tillers in the mutant had their own adventitious roots (photo taken at 21 DAI). Panel 2 is a higher magnification of the boxed area in panel 1 that reveals coleoptiles (1C and 2C, respectively) and adventitious roots (1R and 2R, respectively) of the main stem and first tiller.

(E) Dwarfism and early tillering of seedlings of mutant and transgenic rice compared with the wild type (photo taken at 12 DAI). Panel 2 is a higher magnification of the boxed area in panel 1 that reveals main stem and first tiller.

Figure 10.

GA Deficiency Increases Rice Tiller and Root Numbers.

Mutant (GA2ox6ACT) or transgenic (Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi: GA2ox6) seeds germinated on Murashige and Skoog agar medium for 18 DAI. Plant height and tiller and root numbers of 10 plants in each line were determined, and error bars indicate the se.

C20 GA2oxs Specifically Inactivate C20-GA Precursors

To examine if GA metabolism in the rice GA2ox6ACT mutant was altered, GAs were purified from leaves of 18-d-old seedlings and mature plants and subjected to gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS)–selected ion monitoring for quantification (Lee and Zeevaart, 2002). In seedlings and mature leaves, the level of active GA1 was much lower in mutants (0.1 and 0 ng/g, respectively) than in the wild type (0.6 and 0.7 ng/g, respectively); by contrast, the level of GA97 was much higher in mutants (28.7 and 10.8 ng/g, respectively) than in the wild type (3.6 and 0.5 ng/g, respectively) (Table 3). Due to small amounts of material, few GAs could be quantified for comparison in both the mutant and wild-type leaves. In a second experiment, large decreases in GA53 and GA19 and an increase in GA110 were also observed in the mutant.

Table 3.

GA Content in the GA2ox6ACT Mutant and the Wild Type

| Contenta

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Sample | GA1 | GA97 |

| Leaves from seedlings at 18 DAI | ||

| GA2ox6ACT | 0.1 | 28.7 |

| Wild type | 0.6 | 3.6 |

| Leaves from mature plants | ||

| GA2ox6ACT | 0.0 | 10.8 |

| Wild type | 0.7 | 0.5 |

GA content in ng g−1 dry weight.

GA12 and GA53 were converted to GA110 and GA97, respectively, in vitro by the Arabidopsis C20 GA2ox7 through 2β-hydroxylation (Schomburg et al., 2003). In this study, the in vitro activity of the rice GA2ox5 and GA2ox6 was also investigated by overexpression as fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase in Escherichia coli. Although these fusion proteins formed protein bodies, they were partially purified (see Supplemental Figure 5 online) and enzyme activities analyzed. In assays with 14C-labeled GAs and analysis by reverse-phase HPLC with online radioactivity monitoring (Lee and Zeevaart, 2005), no metabolism of GA44, GA19, GA20, and GA1 was observed, but GA12 and GA53 were converted to radioactive products with retention times similar to those of GA110 and GA97, respectively. 17,17-[2H2]GAs were used to identify the products by GC-MS. Results showed that GA2ox6 could convert GA12 to GA110 and GA53 to GA97 (Table 4). GA2ox5 had the same catalytic activity as GA2ox6 but activity was weaker, perhaps due to less successful expression in E. coli or lower inherent activity. Nevertheless, these studies provide evidence that overexpression of GA2ox5 and GA2ox6 reduced in vivo synthesis of bioactive GA4 and GA1 from GA12 and GA53, respectively.

Table 4.

Identification of Products Formed after Incubation of Recombinant GA2ox6 from Rice with GA12 or GA53

| Substrate | Product | Mass Spectra of Productsa m/z (% Relative Abundance) |

|---|---|---|

| 17, 17-[2H2]GA12 | 17, 17[2H2]GA110 | M+ 450 (5), 435 (7), 418 (39), 390 (60), 375 (6), 328 (6), 318 (13), 300 (97), 285 (81), 274 (53), 260 (34), 259 (46), 241 (100), 225 (34), 201 (23), 197 (12), 145 (37) |

| 17, 17-[2H2]GA53 | 17, 17[2H2]GA97 | M+ 538 (35), 523 (9), 506 (8), 479 (13), 448 (2), 389 (9), 373 (7), 329 (14), 299 (3), 239 (38), 210 (61), 209 (100), 195 (17), 179 (16), 147 (14), 119 (14) |

As the methyl ester trimethylsilyl ethers.

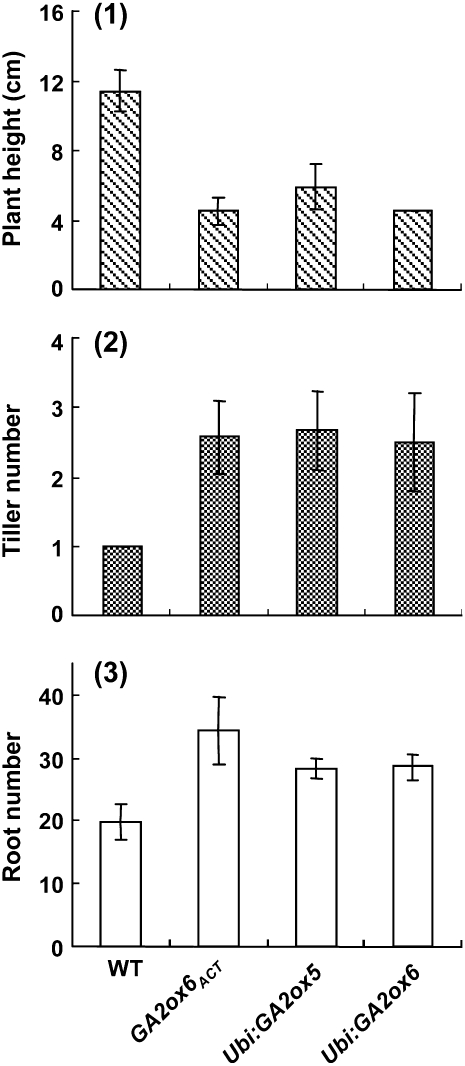

Motif III Is Necessary for Activity of C20 GA2oxs

C20 GA2oxs, including Arabidopsis GA2ox7 and GA2ox8 and spinach GA2ox3, contain three unique conserved motifs that are absent in other GA2oxs (Lee and Zeevaart, 2005). These conserved motifs are also present in rice GA2ox5, GA2ox6, and GA2ox9 (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). No function of these conserved motifs has yet been determined in plants. The rice GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT mutant, which overexpressed GA2ox5 with four amino acids in motif III deleted, exhibited a less severe mutant phenotype. This observation prompted us to investigate the function of motif III in C20 GA2oxs. Truncated cDNAs of GA2ox5 and GA2ox6, with deletion of nucleotides encoding motif III (amino acid residues 325 to 341 and 338 to 358, respectively), were fused downstream of the Ubi promoter to generate constructs Ubi:GA2ox5-IIIΔ and Ubi:GA2ox6-IIIΔ (Figure 11A) for rice transformation. More than 30 independent transgenic plants were obtained for each construct. As shown in Figure 11B, these transgenic plants exhibited the same normal phenotype as the control transformed with the empty vector (cf. panels 2 and 5 with panel 3), which was in contrast with the dwarf phenotype of rice plants transformed with Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6 (panels 1 and 4). Plant height, panicle number, and seed germination were normal in all transgenic plants overexpressing GA2oxs without motif III. These results indicate that deletion of motif III reduces or eliminates the activity of GA2ox5 and GA2ox6.

Figure 11.

Motif III Is Necessary for Activity of GA2ox5 and GA2ox6.

(A) Design of constructs encoding the full-length and motif III–truncated GA2ox5 and GA2ox6. Boxes indicate positions of three highly conserved amino acid motifs. The last amino acid residue was shown at the C terminus of deduced polypeptides.

(B) Comparison of morphology among transgenic rice overexpressing full-length and motif III–truncated GA2ox5 and GA2ox6 and vector pCAMBIA1301 only (CK).

In vitro activity of GA2ox6-IIIΔ protein was examined by overexpression in E. coli as a fusion protein (see Supplemental Figure 6 online). Both the GA2ox6 and GA2ox6-IIIΔ recombinant proteins partially converted GA12 to a product that cochromatographed with the standard GA110 (see Supplemental Figure 7 online). Deletion of motif III appeared to reduce the catalytic activity of the recombinant protein, as the relative amount of GA110 to GA12 was significantly decreased in GA2ox6-IIIΔ. This reduced activity could be the result of an inherent change in catalytic activity, but it could also be the result of unequal enzyme concentrations in the assays.

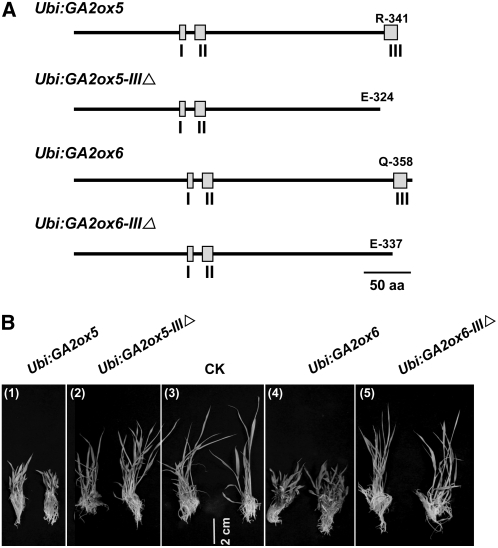

GA Deficiency Promotes Expression of OSH1 and TB1

Our preliminary studies demonstrated that tiller and adventitious root growth was promoted by GA deficiency and inhibited by GA3 (see Supplemental Figure 3A online). Additionally, the inhibition of tillering by GA3 was independent of rice growth stage (see Supplemental Figure 3B online). To determine whether GA deficiency induced expression of OSH1 and TB1 that in turn promotes tillering and root development, GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT, GA2ox6ACT, and wild-type seedlings were grown in media with or without 5 μM GA3 after germination. Rice embryos containing tiller buds were collected at 12 DAI. RT-PCR and real-time quantitative RT-PCR analyses revealed that levels of both OSH1 and TB1 mRNAs were significantly higher in mutants than in the wild type, whereas GA3 significantly reduced levels of both mRNAs in mutants (Figure 12A; RT-PCR data are shown in Supplemental Figure 4 online). The increase in OSH1 and TB1 mRNA levels correlated well with early tillering and adventitious root development in both mutants, whereas GA3 coordinately suppressed OSH1 and TB1 mRNA accumulation and tillering and adventitious root development in both mutants (cf. Figures 12A with 12B). It is not clear why the accumulation of OSH1 and TB1 mRNAs in the wild type was enhanced by GA3 (Figure 12A; see Supplemental Figure 4 online); nevertheless, its stem became more slender and adventitious root growth was inhibited in the mutants (Figure 12B).

Figure 12.

GA3 Suppresses OSH1 and TB1 Expression and Inhibits Tiller and Root Development.

(A) Wild-type and GA2ox6ACT and GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT mutant seeds were germinated in Murashige and Skoog agar medium with (+) or without (−) 5 μM GA3. Total RNA was isolated from embryos containing tiller buds at 12 DAI and analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis using primers that specifically amplified rice OSH1 and TB1 cDNAs. RNA levels were quantified and normalized to the level of rRNA. The highest mRNA level was assigned a value of 100, and mRNA levels of other samples were calculated relative to this value. Error bars indicate the se for three replicate experiments.

(B) Seedlings used in (A) were photographed prior to RNA isolation. Panels 1 and 2 are higher magnifications of boxed areas for GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT and GA2ox6ACT mutants without GA3 treatment to reveal the main stem (MS) and first tiller (1T).

DISCUSSION

The GA2ox Family Is Differentially Regulated and Acts in Concert or Individually to Control GA Levels

Studies of the effects of GAs on plant growth and development have been hindered by their low abundance and variation in time and place. Examination of expression of genes encoding enzymes involved in GA biosynthesis and catabolism provides an alternative approach for such studies. In this study, we showed that GA2oxs are differentially regulated during the rice life cycle, indicating that they act in concert or individually to control GA levels during rice development. For example, seven GA2oxs, excluding GA2ox2 and GA2ox6, were downregulated in correlation with the phase transition from vegetative to reproductive growth (Figure 3B). This result is consistent with the role of GA in promoting flowering in maize and Arabidopsis (Evans and Poethig, 1995; Blazquez et al., 1998). In another example, GA2ox6 was significantly downregulated and GA2ox5 and GA2ox9 were moderately downregulated at 2 DAI, which correlated with rapid seed germination (Figure 4). It indicates that at least the class C20 GA2oxs might act coordinately in regulating GA levels necessary for germination. It is unclear how GA2oxs are differentially regulated. Due to the complicated feedback regulatory network and temporal and spatial expression of GA2oxs and other enzymes involved in GA biosynthesis and catabolism, and the interaction between GA metabolism and response pathways (Olszewski et al., 2002; Yamauchi et al., 2007), deciphering the regulatory mechanism of GA2ox expression by more extensive biochemical and genetic studies is required to better understand their exact functions during rice growth and development.

C20 GA2oxs Cause Less Severe GA-Defective Phenotypes Than C19 GA2oxs

In this study, we observed that overexpression of C20 GA2oxs caused less severe GA-defective phenotypes in rice than C19 GA2oxs. For example, rice overexpressing C19 GA2oxs, including GA2ox3ACT mutant and Act1:GA2ox1 and Act1:GA2ox3 transgenic rice, exhibited severe dwarfism and bore no seeds despite long cultivation periods (Figure 5A; Sakamoto et al., 2001; Sakai et al., 2003). However, rice overexpressing C20 GA2oxs, including GA2ox6ACT mutant and Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6 transgenic rice, although they also exhibited severe dwarfism, did produce seeds after prolonged cultivation. The GA2ox9ACT mutant, which also overexpressed a C20 GA2ox, exhibited a semidwarf phenotype and produced a close to normal amount of seeds with normal germination rate. Similarly, heterologous overexpression of C20 GA2ox, including the spinach GA2ox3 and rice GA2ox5 and GA2ox6, in transgenic tobacco resulted in typically GA deficient dwarfism and late flowering, but normal flowers and seed production were obtained (Figures 7C and 7D; Lee and Zeevaart, 2005).

In transgenic tobacco overexpressing spinach GA2ox3, although GA precursors were deactivated, GA 20-oxidase could still convert a small amount of the precursor to GA1 (Lee and Zeevaart, 2005). This observation could be explained by two possibilities. First, the total amount of C20-GA precursors is too high to be completely deactivated by C20 GA2oxs, compared with the total amount of C19-GA precursors and active C19-GAs that are deactivated by C19 GA2oxs. This notion is supported by studies in rice, Arabidopsis, and tobacco showing that the total amount of C20-GA precursors in these plants is significantly higher than the total amount of C19-GA precursors and active C19-GAs (Sakamoto et al., 2001; Schomburg et al., 2003; Lee and Zeevaart, 2005). Alternatively, C20-GA precursors are so diverse that it allows some of them to escape from inactivation by C20 GA2oxs, so that they can be converted by GA 20-oxidase and GA 3-oxidase to active C19-GAs. These studies may also explain why C20 GA2oxs cause less severe GA-defective phenotype than C19 GA2oxs.

Activity of C20 GA2oxs seems to be conserved in monocots and dicots. For example, ectopic overexpression of GA2ox5 caused more severe effects than GA2ox6 on plant growth and seed development in both transgenic rice and tobacco. However, differences in effects of GA deficiency on plant growth were observed between monocots and dicots. For example, GA deficiency inhibits root elongation only in transgenic tobacco (Figures 7E and 7F; Lee and Zeevaart, 2005) but not in transgenic rice (Figure 8B, Table 1). Furthermore, tillering was promoted in transgenic rice (Figure 10), but branching in transgenic tobacco was not (Lee and Zeevaart, 2005).

C20 GA2oxs contain three unique and conserved motifs, and among them, the recombinant GA2ox6 was shown to be capable of catalyzing 2β-hydroxylation of C20-GAs, instead of C19-GAs catalysis by C19 GA2oxs; this is similar to C20 GA2oxs from other plant species (e.g., the Arabidopsis GA2ox7 and GA2ox8) (Schomburg et al., 2003) and spinach GA2ox3 (Lee and Zeevaart, 2005). These findings suggest that C20 GA2oxs have a substrate specificity distinct from that of C19 GA2oxs (Figure 1). In this study, motif III was found to play a role in activity of C20 GA2oxs. Overexpression of GA2ox5 missing four amino acids in motif III in the GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT mutant reduced GA concentration to a level that promoted tillering, but only slightly inhibited stem elongation and had no significant effect on seed production (Table 1), indicating that the truncated enzyme is at least partially functional. This notion is further supported by the likely reduced in vitro activity of recombinant GA2ox6-IIIΔ (see Supplemental Figure 7 online). It also suggests that tillering, stem elongation, and seed production are regulated by different GA concentrations.

T-DNA Activation–Tagged Rice Mutants Facilitate Study of Physiological Functions of Genes Involved in GA Metabolism and Regulation

More than 18 GA-deficient mutants have been identified by screening rice mutant populations that were generated by chemical mutation, retrotransposon (Tos17) insertion, and γ-irradiation (Sakamoto et al., 2004). Despite extensive efforts, loss-of-function mutations in GA2ox that caused an elongated slender phenotype were not found in these mutant populations, probably due to functional redundancy of the GA2ox multigene family; however, gain-of-function mutations in a GA2ox that caused a dwarf phenotype were also not found in these mutant populations (Sakamoto et al., 2004). In this study, severe dwarf and semidwarf rice mutants were identified by forward and reverse genetics screens, respectively, of the TRIM mutant library (Hsing et al., 2007). All these mutants displayed specific phenotypes due to activation of individual GA2oxs.

An additional advantage of the T-DNA activation approach is that it allows the overexpression of GA2oxs under the control of their native promoters. The T-DNA activation approach has been shown to mainly elevate the expression level of nearby genes without altering the original expression pattern in general (Jeong et al., 2002). The controlled expression of GA2oxs in the right time and right place may give rise to phenotypes that facilitate not only identification of mutants with altered GA2ox functions but also study of functions of other genes involved in growth and development through control of GA metabolism and signaling pathways in rice.

GA Signaling Represses OSH1 and TB1 Expression That in Turn Inhibits Tillering

Despite the important contribution of tillering and root system to grain yield, the mechanisms that control these two developmental processes in rice are mostly unclear. It is interesting to note that high tillering often accompanies dwarfism in rice (Ishikawa et al., 2005). A recent study showed that overexpression of the YABBY1 gene, a feedback regulator of GA biosynthesis, in transgenic rice leads to reduced GA level, increased tiller number, and a semidwarf phenotype (Dai et al., 2007), which provides a clue that GA might coordinately control the two opposite developmental processes.

In this study, using GA-deficient mutants, we demonstrated that stem elongation was inhibited but tillering was promoted by GA deficiency; by contrast, stem elongation was promoted but tillering was inhibited by GA3 (Figure 12). Consequently, we conclude that GA concomitantly promotes shoot elongation and inhibits tillering (Figure 1). However, an increase in tillering indicates a loss of apical dominance. Studies mostly with dicots indicate that this process is mediated by a network of hormonal signals: apically produced auxin inhibits axillary meristems, while cytokinin promotes meristem growth (Busov et al., 2008). A HIGH-TILLERING DWARF1 (HTD1) gene, encoding a carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase, negatively regulates tiller bud outgrowth in rice (Zou et al., 2006). As HTD1 expression is induced by auxin (1-naphthalene acetic acid), it has been suggested that auxin may suppress rice tillering partly through upregulation of HTD1 transcription (Zou et al., 2006). Further studies are required to understand whether auxin, cytokinin, and GA signaling interact and control tillering in rice.

In this study, we also showed that growth of adventitious roots was induced by GA deficiency and suppressed by GA3 (Figure 12). This observation is supported by a recent study that shows that GA3 inhibits adventitious root formation in Populus (Busov et al., 2006). Additionally, overexpression of DELLA-less versions of GA insensitive (GAI) and repressor of GAI-like 1, which conferred GA insensitivity in transgenic Populus trees, led to dwarfism and an increase in adventitious root growth (Busov et al., 2006). Crown rootless (Crl1) promotes crown and lateral root formation, and Crl1 itself is upregulated by auxin in rice (Inukai et al., 2005). However, aboveground organs are normal in the crl1 mutant (Inukai et al., 2005), indicating that adventitious/crown root growth might be regulated by a root-specific auxin signaling pathway. Again, further studies are required to determine whether auxin and GA signaling interact to regulate root growth in rice.

MOC1 is an essential regulator of rice tiller bud formation and development (Li et al., 2003). Overexpression of MOC1 also promotes tiller growth and inhibits stem elongation in transgenic rice, and OSH1 and TB1 are downstream positive regulators themselves positively regulated by MOC1 in tiller development (Li et al., 2003; Wang and Li, 2005). In addition to tillering, seed germination and fertilization are also impaired in the moc1 mutant, which indicates that MOC1 might be involved in GA signaling pathways by serving as both a positive and negative regulator (Wang and Li, 2005). However, it is unclear how MOC1 interacts with the GA signaling pathway for regulation of OSH1 and TB1 expression and, thus, tiller development.

We were unable to detect MOC1 mRNA in GA2ox6ACT mutant and wild-type seedlings by the RT-PCR method in a quantitative manner, probably due to its low abundance in the axillary buds (Li et al., 2003). Nevertheless, we showed that expression of OSH1 and TB1 in tiller buds was induced by GA deficiency and suppressed by GA3 (Figure 12A). Meanwhile, development of tiller and adventitious roots was promoted by GA deficiency and inhibited by GA3 (Figure 12B). Consequently, our study provides evidence that GA negatively regulates OSH1 and TB1 expression that in turn inhibits tiller development (Figure 1). However, whether GA inhibition of adventitious root development is also mediated through OSH1 and TB1 cannot be decided from our results.

It is unclear why exogenous GA confers opposite effects, by repressing OSH1 and TB1 mRNA accumulations in the mutants, but inducing their expression in the wild type (Figure 12A). Nevertheless, the role of OSH1 in positive regulation of tiller development is also supported by some earlier studies showing that overexpression of the rice OSH1 led to formation of multiple shoot and floral apices in transgenic Arabidopsis (Matsuoka et al., 1993) and multiple shoots in transgenic tobacco and rice (Kano-Murakami et al., 1993; Sentoku et al., 2000). The role of TB1 in tiller development is more intriguing, as overexpression of the rice TB1 alone inhibits lateral branching but not the propagation of axillary buds in transgenic rice (Takeda et al., 2003). Whether co-overexpression of OSH1 and TB1 promotes tillering remains for further studies.

Use of C20 GA2ox in Plant Breeding

Semidwarfism is one of the most valuable traits in crop breeding because it results in plants that are more resistant to damage by wind and rain (lodging resistant) and that have stable yield increases. It is a major factor in the increasing yield of the green revolution varieties (Peng et al., 1999; Spielmeyer et al., 2002). However, the creation of such varieties has relied on limited natural genetic variation within crop species. Overexpression of GA2oxs is an easy way to reduce GA levels in transgenic plants. However, constitutive ectopic overexpression of most GA2oxs caused severe dwarfism and low seed production in various plant species because active GAs were probably deactivated as soon as they were produced (Sakamoto et al., 2001; Singh et al., 2002; Schomburg et al., 2003; Biemelt et al., 2004; Lee and Zeevaart, 2005; Dijkstra et al., 2008). Expression of rice GA2ox1 under the control of the rice GA3ox2 promoter, at the site (shoot apex) of active GA biosynthesis, led to a semidwarf phenotype with normal flowering and grain development (Sakamoto et al., 2003).

In this study, our discoveries offer three different approaches for breeding plants with reduced height, increased root biomass, and normal flowering and seed production by overexpression of C20 GA2oxs. First, overexpression of GA2ox9 generated a semidwarf rice variety. The average grain weight and fertility of the GA2ox9ACT mutant were only slightly reduced (by 8 and 4%, respectively), but tiller number increased 22% compared with the wild type (Table 1), which suggests a potential yield increase. Second, overexpression of C20 GA2oxs with defective motif III could also generate a semidwarf rice variety. The average grain weight and fertility of the GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT mutant was reduced by 16 and 12%, respectively, but tiller number increased almost twofold (Table 1), which also suggests a potential for overall yield increase. Third, overexpression of a selected C20 GA2ox gene, such as GA2ox6, which has less effect on plant growth under the control of a weak promoter or its native promoter, could be beneficial for breeding a semidwarf plant without sacrificing seed production. It is interesting to note that both number and length of adventitious roots of both GA2ox5Δ335-341ACT and GA2ox9ACT increased (Table 1), a trait that could be beneficial for increased nutrient and water uptake from soil and carbon sequestration from aerial tissues and for bioremediation. Our studies have provided important information for the future application of C20 GA2oxs to improve yields in a wide range of plant species.

METHODS

Plant Materials

The rice cultivar Oryza sativa cv Tainung 67 was used in this study. Mutant and wild-type seeds were surface sterilized in 2.5% NaClO, placed on Murashige and Skoog agar medium (Murashige and Skoog Basal Medium; Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated at 28°C with 16 h light and 8 h dark for ∼15 to 20 d. Plants were transplanted to pot soil and grown in a net house. Transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) seeds were surface-sterilized in 2.0% NaClO, placed on half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar medium, incubated at 22°C with 16 h light and 8 h dark for 15 to 20 d, and then transferred to pot soil and grown in a net house.

Database Searching and Phylogenetic Analysis of Rice GA2oxs

GA2oxs were identified by BLAST search of the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), TIGR database (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/e2k1/osa1/irgsp.shtml), and Rice Genome Annotation (RiceGAAS) database (http://ricegaas.dna.affrc.go.jp) with the conserved domain in the 2-oxoglutarate–dependent oxygenase family and nucleotide sequences of four previously identified rice GA2oxs (GA2ox1 to GA2ox4) (Sakamoto et al., 2001, 2004; Sakai et al., 2003) and two uncharacterized GA2oxs (GA2ox5 and GA2ox6) (Lee and Zeevaart, 2005). Deduced amino acid sequences of GA2oxs were aligned with the ClustalW2 (version 2.0.8) and AlignX (Vector NTI, version 9.0.0; Informax) programs, and conserved residue shading was performed using the BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor (version 7.0.7.0) for generation of the PHYLIP file (see Supplemental Data Sets 1 and 2 online). Evolutionary relationships were deduced using the neighbor-joining algorithm (Saitou and Nei, 1987). Bootstrapping was performed using the PHYLIP program (version 3.6.7) with 1000 replicates. The unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed using the MEGA 4 phylogenetic analysis program (Tamura et al., 2007). The Knowledge-based Oryza Molecular Biological Encyclopedia database (http://cdna01.dna.affrc.go.jp/cDNA) was used for cDNA searching.

T-DNA Flanking Sequence Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted with a CTAB extraction buffer as described (Doyle and Doyle, 1987). T-DNA flanking sequences were rescued using a built-in plasmid rescue system (Upadhyaya et al., 2002) and analyzed with an ABI Prism 3100 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) using DNA sequences 100 bp upstream of the T-DNA right border (Hsing et al., 2007) as primer. T-DNA flanking sequences were searched using BLASTN against the NCBI database for assignment in the rice BAC/PAC site, and gene dispersions were annotated by the RiceGAAS database.

RT-PCR and Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR Analyses

Total RNA was purified from rice tissues using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with RNase-free DNase I (Promega). The DNase-digested RNA sample was used for reverse transcription by Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Samples, which served as cDNA stocks for PCR analysis, were stored at −70°C.

RT-PCR analysis was performed in a 15-μL solution containing 0.9 μL cDNA stock using GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega). For GA2ox2, GA2ox7, and GA2ox8 that had very low mRNA abundance, RT-PCR analysis was performed using KOD Hot Start DNA Polymerase (Novagen). All PCR reactions were performed in a 15-μL reaction solution containing 0.9 μL cDNA, using a programmable thermal cycler (PTC-200; MJ Research). Concentrations of all GA2ox mRNAs were very low; therefore, higher PCR cycles in the linear quantitative range were performed. The numbers of PCR cycles were 33 for GA2ox1 and GA2ox3, 34 for the rest of GA2oxs, and 24 for rRNA. RT-PCR products were fractionated in a 1.5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. All RT-PCR analyses were performed more than three times from at least two batches of RNA samples with similar results.

The same RNA samples were further used to analyze OSH1 and TB1 expression profiles using quantitative RT-PCR analysis by the ABI 7300 system as described (Dai et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2007). SYBR green was used to monitor the kinetics of PCR product in real-time RT-PCR. 18S rRNA was used as an internal control to quantify the relative transcript level of OSH1 and TB1 in 15-DAI shoots.

Rice and Tobacco Transformation

Full-length GA2ox5 and GA2ox6 cDNAs were PCR amplified from rice mRNA based on their putative open reading frames annotated with the RiceGAAS database. A BamHI restriction site was designed at the 5′ end of DNA primers used for PCR amplification (see Supplemental Table 4 online). The PCR products of 1043 and 1094 bp were ligated into the pGEM-T Easy cloning vector (Promega), and their sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Plasmid pAHC18 (Bruce et al., 1989) was derived from plasmid pUC18 that contains the Ubi promoter and nopaline synthase (Nos) terminator. GA2ox5 and GA2ox6 cDNAs were then excised with BamHI from the pGEM-T Easy vector and ligated into the same site between the Ubi promoter and Nos terminator in plasmid pAHC18. Plasmids containing Ubi:GA2ox5 and Ubi:GA2ox6 were linearized with HindIII and inserted into the same site in pCAMBIA1301 (Hajdukiewicz et al., 1994). The resulting binary vectors were transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 and used for rice and tobacco transformation as described (Krugel et al., 2002).

DNA fragments of GA2ox5-IIIΔ325-341 and GA2ox6-IIIΔ338-358 were PCR amplified. PCR products of 992 and 1031 bp were cloned into the pCAMBIA1301 binary vector, following procedures described above, for generation of binary vectors containing Ubi:GA2ox5-IIIΔ325-341 and Ubi:GA2ox6-IIIΔ338-358 for rice transformation.

Expression and Activity Assay of Recombinant GA2ox5 and GA2ox6

Full-length cDNAs of GA2ox5 and GA2ox6 in the pGEM-T Easy cloning vector were digested with BamHI and subcloned into the same site in pGEX-5X expression vector (Amersham Biosciences). The resulting expression vectors were used to transform Escherichia coli strain BL21-CodonPlus (DE3) RIPL (Stratagene). A volume 500 mL culture in Luria-Bertani broth (Difco) with 100 mg L−1 ampicillin was incubated at 37°C until cell density reached an OD600 around 0.6 to ∼0.8. The recombinant protein induction was performed by adding 0.3 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and incubated at 28°C for another 3 h. Bacteria were collected from the culture medium by centrifugation, resuspended in a BugBuster Protein Extraction Reagent (a buffer containing DTT, rBenzonase Nuclease, and rLysozyme, as indicated in the manufacturer's instruction manual; Novagen), and centrifuged again. The supernatant protein extracts were partially purified by elution through a GST-Bind resin (Novagen) with 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0, containing 10 mM reduced glutathione and stored at −80°C. The frozen extracts were lyophilized, shipped to J.A.D.Z.'s lab at Michigan State University, and reconstituted with cold distilled water for enzyme activity assays as described (Lee and Zeevaart, 2002, 2005).

Analysis of Endogenous GA Levels

The procedures for extraction, purification, and quantification of endogenous GAs have been described elsewhere (Talon et al., 1990; Zeevaart et al., 1993; Schomburg et al., 2003).

Primers

Nucleotides for all primers used PCR and RT-PCR analyses are provided in Supplemental Table 4 online.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the NCBI or TIGR database under the following accession numbers: AtGA2ox1, AJ132435; AtGA2ox2, AJ132436; AtGA2ox3, AJ132437; AtGA2ox4, AY859740; AtGA2ox6, AY859741; AtGA2ox7, NM109746; AtGA2ox8, NM118239; CmGA2ox, AJ302041; LsGA2ox1, AB031206; NtGA2ox1, AB125232; NtGA2ox3, EF471117; NtGA2ox5, EF471118; PcGA2ox1, AJ132438; poplar GA2ox1, AY392094; PsGA2ox1, AF056935; PsGA2ox2, AF100954; SoGA2ox1, AF506281; SoGA2ox2, AF206282; SoGA2ox3, AY935713; 18S rRNA, AH001794; OSH1, D16507; and TB1, AY286002.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. The Rice GA2ox Family.

Supplemental Figure 2. Amino Acid Sequence Alignment of Rice GA2oxs (OsGA2ox1, OsGA2ox3, OsGA2ox5, OsGA2ox6, and OsGA2ox9), Arabidopsis GA2oxs (AtGA2ox7 and AtGA2ox8), and spinach GA2ox (SoGA2ox3).

Supplemental Figure 3. GA3 Represses Tiller Growth Independent of Growth Stages.

Supplemental Figure 4. GA3 Suppresses OSH1 and TB1 Expression.

Supplemental Figure 5. Production, Purification, and SDS-PAGE Analyses of GST-Fused Recombinant GA2ox5 and GA2ox6.

Supplemental Figure 6. Conversion of [14C]GA12 to [14C]GA110 by Recombinant GA2ox6 and GA2ox6-IIIΔ Proteins.

Supplemental Table 1. Putative GA2ox Gene Family in Rice (Oryza sativa).

Supplemental Table 2. Comparison of Deduced Amino Acids among Rice GA2oxs.

Supplemental Table 3. Gene Names and Accession Numbers of 19 GA2oxs from Different Plant Species.

Supplemental Table 4. Primers Used for T-DNA Flanking Sequence, PCR, and RT-PCR Analyses and Plasmid Construction.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Text File Corresponding to the Phylogenetic Tree in Figure 2.

Supplemental Data Set 2. Text File Corresponding to the Phylogenetic Tree in Supplemental Figure 1B.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tuan-hua David Ho and Harry Wilson for their critical review of this manuscript and, Mei-Chu Chung, Chyr-Guan Chern, Chang-Sheng Wang, Ming-Jen Fan, Lin-Chih Yu, Lin-yun Kuang, Tung-Hi Tseng, Ming-Jier Jiang, and Wen-Bin Tseng for their technical assistance. We also thank Bev Chamberlin of the Michigan State University Mass Spectrometry Facility for assistance with GC-MS. This work was supported by grants from Academia Sinica (AS92-AB-IMB-03 and AS93-AB-IMB-02 to S.-M.Y.), the Council of Agriculture (94-AS-5.2.1-S-a1-8 to L.-J.C.), and the National Science Council (NSC92-2317-B-001-036 to S.-M.Y. and NSC96-2317-B-005-007 to L.-J.C.) of the Republic of China.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) are: Liang-Jwu Chen (ljchen@nchu.edu.tw) and Su-May Yu (sumay@imb.sinica.edu.tw).

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Biemelt, S., Tschiersch, H., and Sonnewald, U. (2004). Impact of altered gibberellin metabolism on biomass accumulation, lignin biosynthesis, and photosynthesis in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Physiol. 135 254–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazquez, M.A., Green, R., Nilsson, O., Sussman, M.R., and Weigel, D. (1998). Gibberellins promote flowering of Arabidopsis by activating the LEAFY promoter. Plant Cell 10 791–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, W.B., Christensen, A.H., Klein, T., Fromm, M., and Quail, P.H. (1989). Photoregulation of a phytochrome gene promoter from oat transferred into rice by particle bombardment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86 9692–9696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busov, V., Meilan, R., Pearce, D., Rood, S., Ma, C., Tschaplinski, T., and Strauss, S. (2006). Transgenic modification of gai or rgl1 causes dwarfing and alters gibberellins, root growth, and metabolite profiles in Populus. Planta 224 288–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busov, V.B., Brunner, A.M., and Strauss, S.H. (2008). Genes for control of plant stature and form. New Phytol. 177 589–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.-H., Kobayashi, M., Fujioka, S., Matsuno, T., Hirosawa, T., and Sakurai, A. (1995). Fluctuation of endogenous gibberellin levels in the early development of rice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 59 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, M., Zhao, Y., Ma, Q., Hu, Y., Hedden, P., Zhang, Q., and Zhou, D.X. (2007). The rice YABBY1 gene is involved in the feedback regulation of gibberellin metabolism. Plant Physiol. 144 121–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, C., Adams, E., Bhattacharya, A., Page, A., Anthony, P., Kourmpetli, S., Power, J., Lowe, K., Thomas, S., Hedden, P., Phillips, A., and Davey, M. (2008). Over-expression of a gibberellin 2-oxidase gene from Phaseolus coccineus L. enhances gibberellin inactivation and induces dwarfism in Solanum species. Plant Cell Rep. 27 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J.J., and Doyle, J.L. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.M., and Poethig, R.S. (1995). Gibberellins promote vegetative phase change and reproductive maturity in maize. Plant Physiol. 108 475–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleet, C.M., and Sun, T.P. (2005). A DELLAcate balance: the role of gibberellin in plant morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graebe, J.E. (1987). Gibberellin biosynthesis and control. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 38 419–465. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukiewicz, P., Svab, Z., and Maliga, P. (1994). The small, versatile pPZP family of Agrobacterium binary vectors for plant transformation. Plant Mol. Biol. 25 989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden, P., and Phillips, A.L. (2000). Gibberellin metabolism: New insights revealed by the genes. Trends Plant Sci. 5 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing, Y.-I., et al. (2007). A rice gene activation/knockout mutant resource for high throughput functional genomics. Plant Mol. Biol. 63 351–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, L., McSteen, P., Doebley, J., and Hake, S. (2002). Expression patterns and mutant phenotype of teosinte branched1 correlate with growth suppression in maize and teosinte. Genetics 162 1927–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inukai, Y., Sakamoto, T., Ueguchi-Tanaka, M., Shibata, Y., Gomi, K., Umemura, I., Hasegawa, Y., Ashikari, M., Kitano, H., and Matsuoka, M. (2005). Crown rootless1, which is essential for crown root formation in rice, is a target of an AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR in auxin signaling. Plant Cell 17 1387–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, S., Maekawa, M., Arite, T., Onishi, K., Takamure, I., and Kyozuka, J. (2005). Suppression of tiller bud activity in tillering dwarf mutants of rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 46 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, D.H., An, S., Kang, H.G., Moon, S., Han, J.J., Park, S., Lee, H.S., An, K., and An, G. (2002). T-DNA insertional mutagenesis for activation tagging in rice. Plant Physiol. 130 1636–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano-Murakami, Y., Yanai, T., Tagiri, A., and Matsuoka, M. (1993). A rice homeotic gene, OSH1, causes unusual phenotypes in transgenic tobacco. FEBS Lett. 334 365–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, R.W., and Evans, L.T. (2003). Gibberellins and flowering of grasses and cereals. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54 307–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugel, T., Lim, M., Gase, K., Halitschke, R., and Baldwin, I.T. (2002). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Nicotiana attenuata, a model ecological expression system. Chemoecology 12 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.J., and Zeevaart, J.A.D. (2002). Differential regulation of RNA levels of gibberellin dioxygenases by photoperiod in spinach. Plant Physiol. 130 2085–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.J., and Zeevaart, J.A.D. (2005). Molecular cloning of GA 2-oxidase3 from spinach and its ectopic expression in Nicotiana sylvestris. Plant Physiol. 138 243–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., et al. (2003). Control of tillering in rice. Nature 422 618–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.-A., Lin, C.-C., Lee, K.-W., Chen, J.-L., Huang, L.-F., Ho, S.-L., Liu, H.-J., Hsing, Y.-I., and Yu, S.-M. (2007). The SnRK1A protein kinase plays a key role in sugar signaling during germination and seedling growth of rice. Plant Cell 19 2484–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.N., Proebsting, W.M., and Hedden, P. (1999). The SLENDER gene of pea encodes a gibberellin 2-oxidase. Plant Physiol. 121 775–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, M., Ichikawa, H., Saito, A., Tada, Y., Fujimura, T., and Kano-Murakami, Y. (1993). Expression of a rice homeobox gene causes altered morphology of transgenic plants. Plant Cell 5 1039–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski, N., Sun, T.-p., and Gubler, F. (2002). Gibberellin signaling: Biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. Plant Cell 14 S61–S80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J., et al. (1999). ‘Green revolution’ genes encode mutant gibberellin response modulators. Nature 400 256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou, N., and Nei, M. (1987). The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, M., Sakamoto, T., Saito, T., Matsuoka, M., Tanaka, H., and Kobayashi, M. (2003). Expression of novel rice gibberellin 2-oxidase gene is under homeostatic regulation by biologically active gibberellins. J. Plant Res. 116 161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, T., Kobayashi, M., Itoh, H., Tagiri, A., Kayano, T., Tanaka, H., Iwahori, S., and Matsuoka, M. (2001). Expression of a gibberellin 2-oxidase gene around the shoot apex is related to phase transition in rice. Plant Physiol. 125 1508–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, T., Morinaka, Y., Ishiyama, K., Kobayashi, M., Itoh, H., Kayano, T., Iwahori, S., Matsuoka, M., and Tanaka, H. (2003). Genetic manipulation of gibberellin metabolism in transgenic rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 21 909–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, T., et al. (2004). An overview of gibberellin metabolism enzyme genes and their related mutants in rice. Plant Physiol. 134 1642–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Y., Hong, S.-K., Tagiri, A., Kitano, H., Yamamoto, N., Nagato, Y., and Matsuoka, M. (1996). A rice homeobox gene, OSH1, is expressed before organ differentiation in a specific region during early embryogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 8117–8122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomburg, F.M., Bizzell, C.M., Lee, D.J., Zeevaart, J.A.D., and Amasino, R.M. (2003). Overexpression of a novel class of gibberellin 2-oxidases decreases gibberellin levels and creates dwarf plants. Plant Cell 15 151–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentoku, N., Sato, Y., and Matsuoka, M. (2000). Overexpression of rice OSH genes induces ectopic shoots on leaf sheaths of transgenic rice plants. Dev. Biol. 220 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.P., Jermakow, A.M., and Swain, S.M. (2002). Gibberellins are required for seed development and pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14 3133–3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielmeyer, W., Ellis, M.H., and Chandler, P.M. (2002). Semidwarf (sd-1), “green revolution” rice, contains a defective gibberellin 20-oxidase gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 9043–9048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.P., and Gubler, F. (2004). Molecular mechanism of gibberellin signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55 197–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, T., Suwa, Y., Suzuki, M., Kitano, H., Ueguchi-Tanaka, M., Ashikari, M., Matsuoka, M., and Ueguchi, C. (2003). The OsTB1 gene negatively regulates lateral branching in rice. Plant J. 33 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talon, M., Koornneef, M., and Zeevaart, J.A.D. (1990). Endogenous gibberellins in Arabidopsis thaliana and possible steps blocked in the biosynthetic pathways of the semidwarf ga4 and ga5 mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87 7983–7987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M., and Kumar, S. (2007). MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) Software Version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 1596–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto, E. (2005). Regulation of root growth by plant hormones: Roles for auxin and gibberellin. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 24 249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.G., Phillips, A.L., and Hedden, P. (1999). Molecular cloning and functional expression of gibberellin 2- oxidases, multifunctional enzymes involved in gibberellin deactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 4698–4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya, N.M., et al. (2002). An iAc/Ds gene and enhancer trapping system for insertional mutagenesis in rice. Funct. Plant Biol. 29 547–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., and Li, J. (2005). The plant architecture of rice (Oryza sativa). Plant Mol. Biol. 59 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, S. (2008). Gibberellin metabolism and its regulation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59 225–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, Y., Takeda-Kamiya, N., Hanada, A., Ogawa, M., Kuwahara, A., Seo, M., Kamiya, Y., and Yamaguchi, S. (2007). Contribution of gibberellin deactivation by AtGA2ox2 to the suppression of germination of dark-imbibed Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Plant Cell Physiol. 48 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeevaart, J.A.D., Gage, D.A., and Talon, M. (1993). Gibberellin A1 is required for stem elongation in spinach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90 7401–7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J., Zhang, S., Zhang, W., Li, G., Chen, Z., Zhai, W., Zhao, X., Pan, X., Xie, Q., and Zhu, L. (2006). The rice HIGH-TILLERING DWARF1 encoding an ortholog of Arabidopsis MAX3 is required for negative regulation of the outgrowth of axillary buds. Plant J. 48 687–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.