Abstract

High cervical spinal cord hemisection results in paralysis of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm; however, functional recovery of the paralyzed hemidiaphragm can occur spontaneously. The mechanisms mediating this recovery are unknown. In chronic, experimental contusive spinal cord injury, an upregulation of the NMDA receptor 2A subunit and a down regulation of the AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit has been correlated with improved hind limb motor recovery. Therefore, we hypothesized that NR2A is upregulated, whereas GluR2 is down-regulated following chronic C2 hemisection to initiate synaptic strengthening in respiratory motor pathways. Since NMDA receptor activation can lead to the delivery of AMPA receptor subunits to the post-synaptic membrane, we also hypothesized that there would be an upregulation of the GluR1 AMPA receptor subunit and that activity-regulated cytoskeletal associated protein may mediate the post-synaptic membrane delivery. Female rats were hemisected at C2 and allowed to recover for different time points following hemisection. At these time points, protein levels of NR2A, GluR1, and GluR2 subunits were assessed via Western blot analysis. Western blot analysis revealed that there were increases in NR2A subunit at six and twelve weeks post C2 hemisection. At six, twelve, and sixteen weeks post hemisection, the GluR1 subunit was increased over controls, whereas the GluR2 subunit decreased sixteen weeks post hemisection. Immunocytochemical data qualitatively supported these findings. Results also indicated that activity-regulated cytoskeletal associated protein may be associated with the above changes. These findings suggest a role of NR2A, GluR1, and GluR2 in mediating chronic spontaneous functional recovery of the paralyzed hemidiaphragm following cervical spinal cord hemisection.

Keywords: C2 hemisection, phrenic nucleus, plasticity, glutamate, long term potentiation, motor recovery

INTRODUCTION

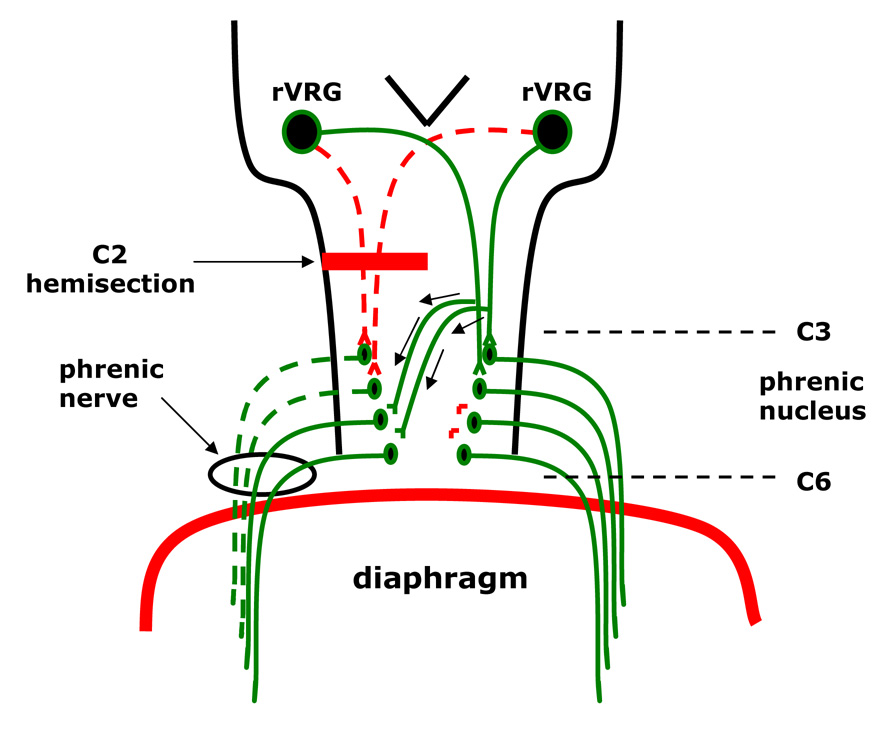

C2 spinal cord hemisection (C2H) results in paralysis of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm. This paralysis results from disruption of the pathways from medullary respiratory centers to the phrenic motor (PM) nucleus of the spinal cord (Goshgarian and Guth, 1977). Activation of a spared, latent respiratory pathway (i.e., the crossed phrenic pathway) (Moreno et al. 1992), restores activity to the once paralyzed hemidiaphragm (Fig. 1) (for review see Goshgarian, 2003). Chronically, expression of the crossed phrenic pathway occurs spontaneously without any intervention (Pitts, 1940; Nantwi, et al., 1999).

Figure 1. Diagram of the crossed phrenic pathway.

High cervical hemisection of the mammalian spinal cord rostral to the level of the phrenic nucleus interrupts (dotted lines) the descending bulbospinal respiratory drive to the ipsilateral phrenic nucleus, resulting in paralysis of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm. Spontaneous activation of the latent pathway occurs as early as six weeks in 33% of hemisected animals of the present study. By 16 weeks, 67% of all C2 hemisected rats display recovery of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm. The latent pathway descends contralateral to the hemisection and then crosses the spinal cord midline to innervate phrenic motor neurons ipsilateral to the lesion. The activation of these neurons induces recovery to the previously paralyzed hemidiaphragm.

The pathway driving PM neurons during inspiration is glutamatergic (McCrimmon, et al., 1989; Liu et al., 1990; Chitravanshi and Sapru, 1996). Distinct glutamate receptor types and subunits are present on phrenic motor neurons (Robinson and Ellenberger, 1997). Among those observed are the subunits of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA) receptors.

Distinguishing it from the AMPA and kainite glutamate receptors, the NMDA receptor has the capacity for calcium influx and a magnesium block, which is relieved through cell membrane depolarization (Moriyoshi, et al., 1991). These features have led to the hypothesis that the NMDA receptor is a “coincidence detector” of simultaneous pre- and post-synaptic activity since NMDA receptor activation requires pre-synaptic glutamate release and post-synaptic membrane depolarization. This makes the NMDA receptor an ideal candidate for mediating long term potentiation (LTP) (Seeburg, et al., 1995; Tang, et al., 1999).

The NMDA receptor complex is formed by distinct subunits: the NR1, NR2A,B,C,D, and NR3 subunits. These subunits confer distinctive properties to the NMDA receptor (Monyer, et al., 1992; Ishii, et al., 1993; Monyer, et al., 1994; Krupp, et al., 1998). Following contusive spinal cord injury at T8, the mRNA levels of the NR2A subunit are upregulated caudal to the site of injury, and the upregulation has been correlated with improved hindlimb function, suggesting that the upregulation strengthens excitatory synaptic connections on hindlimb motor neurons (Grossman, et al., 2000). Later studies have demonstrated that the NR2A subunit is a possible mediator of synaptic strengthening during LTP (Liu, et al., 2004; Massey, et al., 2004).

AMPA receptor complexes are composed of four genetically distinct subunits, GluR1,2,3,4, which confer distinct properties to the AMPA receptor. Specifically, the GluR2/GluR3 heteromer receptor complex is continuously delivered to the synapse, regardless of synaptic activity. However, the GluR1/GluR2 heteromer complex is delivered to the synapse on the basis of synaptic activity, particularly through NMDA receptor activation (Esteban, 2003). Furthermore, the GluR1 subunit is delivered to the post-synaptic membrane during LTP induction (Hayashi, et al., 2000). The GluR2 subunit is down regulated following traumatic CNS injury, including T8 spinal cord injury (Grossman, et al., 1999; Gorter, et al., 1997; Alsbo, et al., 2001).

Based on the above, we hypothesized that following C2H there may be an increase of the NR2A subunit and a down regulation of GluR2 at the level of the phrenic nucleus to initiate synaptic strengthening. Subsequently, an upregulation of GluR1 could result in enhanced glutamatergic drive to PM neurons bringing about spontaneous recovery of the hemidiaphragm in chronically injured animals. These hypotheses were tested in the present investigation.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Surgical procedures and C2 hemisection

Adult female Sprague Dawley rats (250–350 g) were anesthetized with a ketamine (70mg/kg) and xylazine (7mg/kg) solution administered i.p. Following administration of anesthesia, the animals were prepared for surgery by shaving and cleansing the dorsal neck area with betadine and 70% rubbing alcohol. Following the surgical prep, a dorsal midline incision approximately 4 cm on the neck was made. The paravertebral muscles were retracted and a laminectomy of the second cervical vertebra was performed. The dura and arachnoid mater were cut with microscissors and the spinal cord exposed. A left C2 hemisection was made just caudal to the C2 dorsal root with a sharp micro-blade. The incision was made from the midline to the most lateral extent of the cord. Sham hemisected animals were treated identically, but did not receive the hemisection. The muscle layers were drawn back together with 3-0 suture and the skin stapled with wound clips. Following this procedure, the animals received the analgesic buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg, s.c.) and placed on a circulating water blanket until they regained consciousness, upon which they were returned to their cages.

Animals were housed individually in a normal day/night schedule and given food and water ad libitum. 5–10 ml of subcutaneous saline was administered if animals appeared dehydrated. All animal care and handling were carried out under strict compliance with the Division of Laboratory Animal Research at Wayne State University.

Electromyographic Recordings

One week following the hemisection animals were anesthetized with the ketamine and xylazine solution described above. Following cleansing as described above, an eight cm incision was made at the base of the rib cage to expose the abdominal surface of the diaphragm in spontaneously breathing animals. Bi-polar electrodes were inserted in the left and right side of the diaphragm to record respiratory diaphragmatic activity. The electrodes were connected to a data acquisition system and recorded, using the 1401 and Spike2 system and software package (CED, Cambridge, UK). Animals that displayed no activity ipsilateral to the lesion were included in the study. If residual activity was observed in the hemidiaphragm ipsilateral to the lesion, the animal was not included. We waited one week after the hemisection to reduce the likelihood that spinal shock following an incomplete hemisection could have contributed to ipsilateral hemidiaphragm paralysis acutely.

Animal groups

The animals were divided into six groups 1) non-hemisected, 2) sham hemisected, and 4 groups of hemisected animals surviving for 4, 6, 12, and 16 weeks post hemisection. At these time points, the animals were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg i.p.) and bilateral diaphragmatic EMGs were taken to determine if spontaneous diaphragmatic recovery occurred.

Gel electrophoresis and Western blotting

Following EMG recordings at the indicated time points the spinal cords (n = 6 per time point) were harvested at the level of the phrenic nucleus (C3–C6) ipsilateral and caudal to the lesion. The left, injured side of the spinal cord was further dissected by removing and discarding the dorsal half.

The ventral half of the spinal cord containing the phrenic nucleus was stored at – 80° C until processed for electrophoresis. Processing involved sonication of the tissues in a modified Glasgow protein extraction buffer which included 150 mM NaCl, 1.0 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris, 1% NP40, 0.1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors. Following sonication, the solutions were centrifuged for thirty minutes at 15,000 rcf. The supernatant was collected and the protein concentration was determined through the Bradford assay (Sigma, St. Louis, MI). Fifty µg of the protein homogenate concentrated in a 40 µl solution, including Laemmli sample buffer, was then loaded onto a 7.5% Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and separated. Following separation, the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories) (Towbin, et al., 1979).

The PVDF membranes were washed 3x with a Tris/Tween/saline buffer (TBST), followed by blocking with 8% milk, 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 2% normal goat serum (NGS). Following the block, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4° C in the primary antibody diluted in a 1% BSA and 1% NGS TBST solution. The primary antibodies used were mouse monoclonal anti-NR2A (1:200), and rabbit polyclonal anti-GluR1 (1:400) and anti-GluR2 (1:500) antibodies (all antibodies were from Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Membranes were washed extensively and then incubated in a peroxidase conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:2500) or goat anti-rabbit (1:5000) secondary antibody in a 1% BSA and 1% NGS TBST solution for 2 hrs at room temperature. The membranes were again washed extensively with TBST and then incubated in an enhanced chemiluminescent peroxidase substrate (Chemicon) for five minutes and then apposed to film and developed.

The films were scanned with the Image Scanner II and bands corresponding to the subunit proteins were quantified with the ImageQuant TL program (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), which measures the area and density to derive the band intensity. All bands were quantified relative to standard rat cortical tissue that was run along the same time with the samples.

Statistical analysis

SigmaStat (Point Richmond, CA) was used to determine statistical significance for the Western blot results. A One Way Analysis of Variance test was used along with Bonferonni’s method to compare experimental groups with control animals. Values are expressed as means +/− the standard error. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Light Microscopy Immunocytochemistry

12 weeks following hemisection left C2 hemisected and sham hemisected animals (n = 4 per group) were anesthetized and bilateral diaphragmatic activity was recorded as described above to assess for spontaneous recovery. Following recording, a 2% solution of the trans-synaptic retrograde tracer, wheat germ agglutin-horseradish peroxidase (WGA-HRP) (Sigma), dissolved in saline, was injected into the left hemidiaphragm. Briefly, 5 injections of the WGA-HRP solution (10 ul per injection) were administered to the abdominal surface of the left hemidiaphragm of the rats with a Hamilton syringe outfitted with a 30-gauge needle. The injections were made throughout the hemidiaphragm around the phrenic nerve. Following the injections, the abdominal muscles were sutured together with 3-0 silk and the skin stapled together with wound clips (Moreno, et al. 1992).

Two days following the EMG recording and injection of WGA-HRP, the animals were anesthetized with chloral hydrate and then perfused with saline (50 ml) followed by a 2.5% glutaraldehyde/1% paraformaldehyde solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) (250 ml). The spinal cords were harvested and post-fixed for two hours before cryoprotection in 30% sucrose in 0.1 M PB. Following cryoptrotection, the C3–C6 levels of the spinal cord, which contain the phrenic nucleus, were dissected and a pinhole was made on the right side to distinguish between the left and right spinal cord. The spinal cord tissues were embedded in OCT compound (Tissue Tek, Torrance, CA) sectioned transversely on a cryostat at a 50 um thickness and stored in PBS at 4° C.

For the immunocytochemistry studies tissue sections from all different groups were processed at the same time and under identical parameters. Tissue sections were washed first with a 1% sodium borohydrate solution and then followed by PBS washing for three times. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide, and sections were blocked and permeabilized with a 10% NGS/0.3% Triton X-100 0.1 M PBS solution for 30 minutes. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4° C in rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against NR2A (1:1000), GluR1 (1:200–1:700), GluR2 (1:500) as well as a mouse anti-Arc antibody (1:250) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) diluted in 1%NGS/0.3% Triton X-100 0.1 M PBS solution. Following incubation and extensive washing with PBS, the sections were incubated in a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:200) or biotinylated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:200) diluted in 0.3% Triton X-100 in 1% NGS for 2 hrs at room temperature and then processed according to the Vector Laboratory ABC method (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Immunoreactive areas of the sections were developed and visualized with a DAB substrate/hydrogen peroxide solution.

Sections adjacent to those used for immunocytochemistry were processed for WGA-HRP reactivity via the Mesulam tetramethyl benzindene (TMB) peroxidase substrate technique (Mesulam, 1978). Motor neurons comprising the phrenic nucleus were then identified and were used to localize the area of the phrenic nucleus in immunocytochemically labeled sections.

Sections were viewed using a Nikon bright-field microscopy set-up. Digital photographs were taken with a SPOT digital camera and imaging software (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI).

Immunofluorescence

To identify PMNs fluorescently, PMNs were retrogradely labeled with dextran Texas red. In short, the animals were anesthetized as described above and an incision was made at the base of the abdomen to expose the abdominal surface of the diaphragm. Following exposure of the diaphragm, five 10 ul injections of 0.4% Dextran Texas Red (Invitrogen) were made into the side ipsilateral to the lesion for retrograde labeling of the phrenic motor nucleus. Seven days later, the animals were again anesthetized and perfused first with 50 mls of 1X PBS followed by 250 mls of ice cold 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Following perfusion, the C3–C6 spinal cord was dissected out and post-fixed in the perfusate. Prior to sectioning, a pinhole was made on the right side of the spinal cord to denote laterality and the spinal cord was sectioned at a 50 um thickness on a vibratome and placed free-floating in PBS.

Sections were washed 3x with PBS followed by blocking in 5% normal goat serum and 0.1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for two hours at RT. Following blocking, the sections were incubated in the same 1° antibodies used in the light microscopy experiment, diluted the same in blocking buffer, overnight at 4° C. Following overnight incubation, the sections were washed 3x with PBS, thirty minutes each. After washing, the sections were incubated in secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 2° antibody (Invitrogen) solution diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer for 2 hrs at RT. The sections were again washed extensively with PBS and mounted. In the triple label experiments with Arc, following washing, sections were incubated in a solution containing mouse antibody directed against Arc, diluted 1:250 in blocking buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100, overnight at 4° C. The next day after extensive washing with PBS, the sections were incubated in a goat anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 633 2° Ab (Invitrogen) solution diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer with Triton X-100. The sections were viewed under a standard fluorescence microscopy set-up and confocal microscopy set-up.

RESULTS

Functionally complete hemisection and recovery of diaphragmatic activity

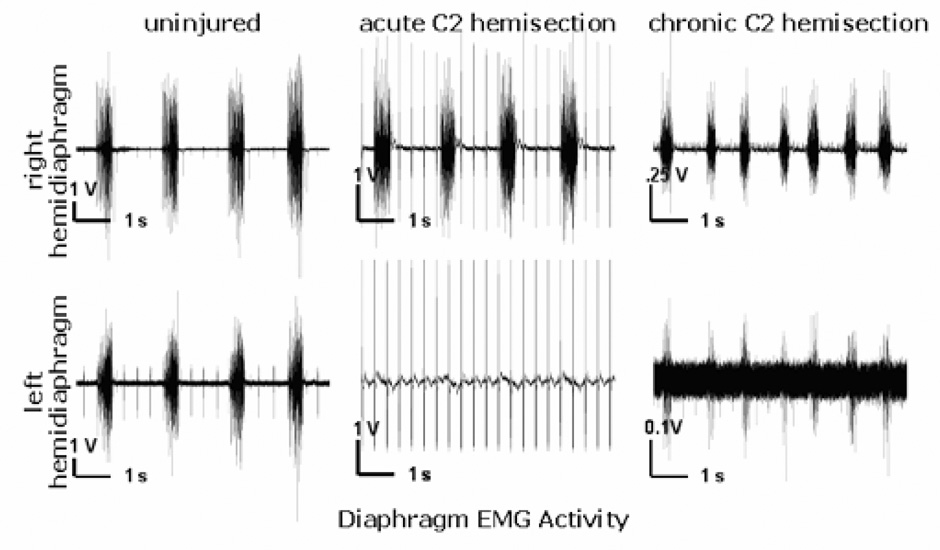

One week following C2 hemisection, all hemisected animals included in this study displayed no hemidiaphragmatic activity on the injured side, revealed through bilateral EMG recordings, indicating a functionally complete hemisection (Fig. 2). The correlation between no EMG activity of the hemidiaphragm ipsilateral to an anatomically complete hemisection of the spinal cord has been observed previously in our lab (Moreno, et al., 1992). Furthermore, as explained previously, waiting one full week after hemisection before assessing diaphragmatic activity virtually eliminates the possibility of spinal shock contributing to hemidiaphragm paralysis following an incomplete lesion acutely.

Figure 2. Electromyograms from both the left and right sides of the diaphragm of an uninjured control rat and the same hemisected rat one week (acute) and 16 weeks (chronic) post injury.

In the non-injured animal (traces on the left), the EMG recording from the left and right hemidiaphragm shows a rhythmic, synchronized activity. Acutely following left C2 hemisection (middle traces), the left hemidiaphragm displayed no EMG activity. Sixteen weeks following left C2 hemisection (traces on the right); however, the previously paralyzed left hemidiaphragm displayed spontaneously recovered EMG activity. Each recording is seven seconds long.

Four weeks after hemisection no animals displayed recovery. However, starting at a time point six weeks after hemisection two out of the six animals began to display spontaneous respiratory activity in the once paralyzed hemidiaphragm. By twelve and sixteen weeks 4 out of six animals had spontaneous activity of the initially paralyzed hemidiaphragm. Activity on the injured side matched the respiratory related rhythm of the uninjured side. Fig. 2 shows an example of the EMG recordings of the left and right hemidiaphragm from a non-hemisected animal, and the EMG recordings from an animal one week following C2 hemisection and from the same animal at sixteen weeks showing spontaneous recovery of the left hemidiaphragm.

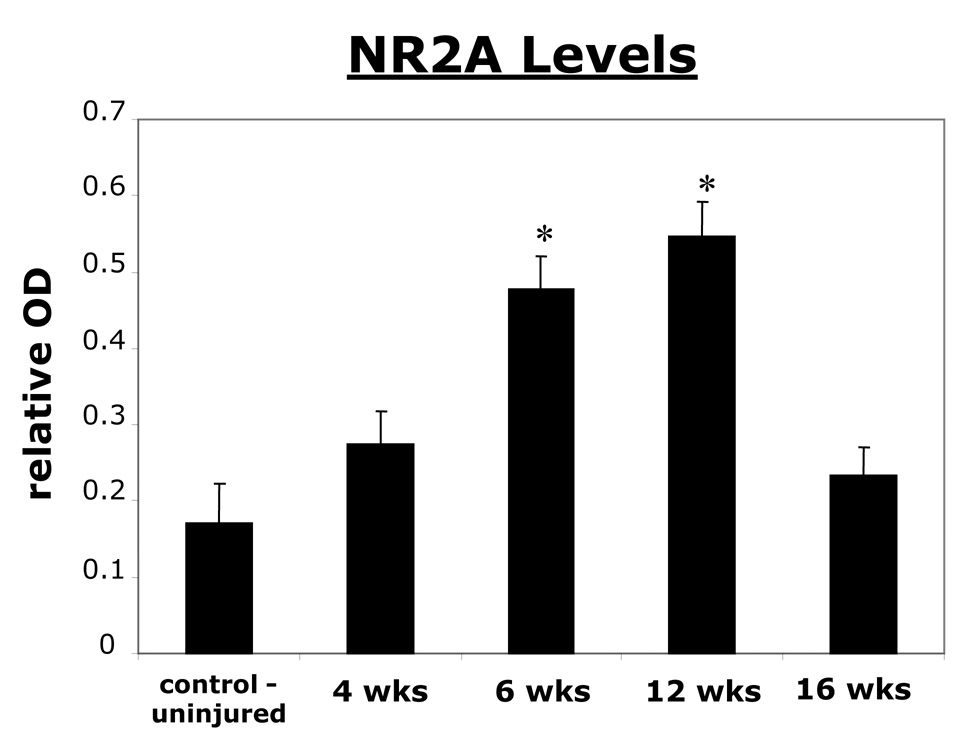

NR2A subunit increases at different time points following C2 hemisection

NR2A subunit levels at various time points post hemisection showed a trend in increasing NR2A subunit protein from control, non-injured animals. Western blot results indicated that at four weeks the level of NR2A was not significantly higher than controls (Fig. 3). However, at six and twelve weeks statistically significant increases were observed compared to control levels, with twelve weeks having the greatest increase (Fig. 3). Interestingly, at 16 weeks post hemisection a drop off in the level of NR2A subunit was observed and the level was once again not significantly higher than controls (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. A graph showing an increase in NR2A subunit at 6 and 12 weeks post hemisection as revealed by Western blot analysis.

All values are relative to a standard cortical tissue run along side the samples. Six and twelve weeks after left C2 hemisection, the left spinal cord (C3–C6) had a significantly higher relative optical density (OD) value corresponding to NR2A protein levels compared to control animals. At sixteen weeks, NR2A protein levels returned to values not significantly higher than controls. * indicates significance with a p < 0.05.

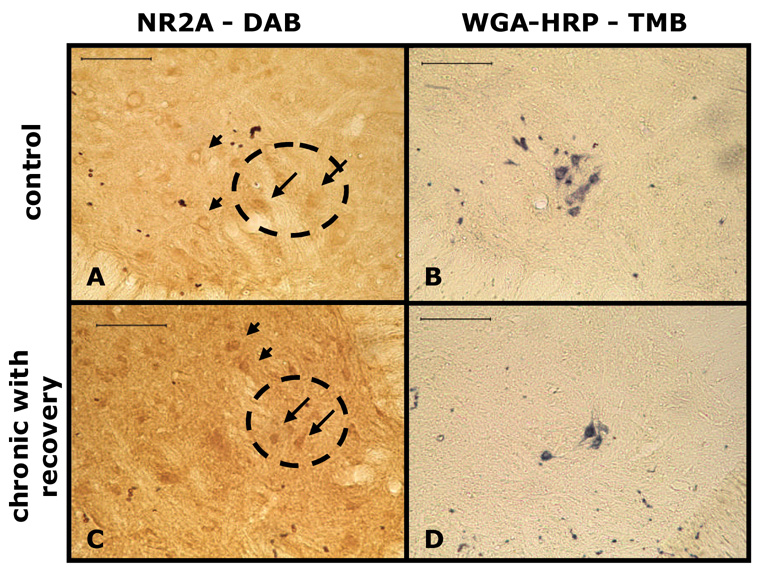

NR2A subunit expression increases in ventral horn motor neurons and phrenic motor neurons

Localization of the NR2A subunit to ventral horn motor neurons (VMN) on the hemisected side of the C3–C6 spinal cord was accomplished through NR2A immunocytochemistry at the twelve week time point and compared to control animals. We used this time point since Western Blot analysis showed the greatest increase in NR2A subunit levels compared to control.

NR2A-DAB immunoreactive neurons were localized to motor neurons in uninjured controls and ipsilateral to injury (Fig. 4A, 4C). NR2A immunoreactive motor neurons of uninjured and sham hemisected animals were similar in intensity (data not shown). Compared qualitatively to the homolateral side of control spinal cord sections, there was a more intense NR2A-DAB staining of ventral horn motor neurons on the injured side of the 12 week hemisected rats (Fig. 4A, 4C).

Figure 4. Light micrographs of ventral horn motor neurons and phrenic motor neurons (identified through retrograde labeling with WGA-HRP) showing increased NR2A immunoreactivity (IR) following chronic C2 hemisection in rats.

Immunocytochemistry revealed that there was an increase in the density of NR2A IR in ventral horn motor neurons and phrenic motor neurons in C2 hemisected rats compared to control. A and B are from a control, non-hemisected rat. C and D are from a chronic (12 weeks) C2 hemisected animal with recovery. B and D show retrogradely labeled PMNs visualized with TMB (arrows). A and C are adjacent sections to B and D, respectively, and show NR2A immunoreactive motor neurons (arrowheads) as well as phrenic motor neurons (arrows). The circle is the relative location of the phrenic motor nucleus derived from the adjacent sections. Scale bars = 100 µm.

WGA-HRP labeled phrenic motor neurons reacting with the TMB substrate produced a blue colored product labeling the entire cell body and proximal dendrites (Fig. 4B, 4D). The area of the phrenic motor nucleus was delineated from positively labeled WGA-HRP motor neurons and superimposed on adjacent NR2A-DAB immunoreacted sections. Similar to other ventral horn motor neurons, phrenic motor neurons had a more intense NR2A-DAB reaction compared to the homolateral side of control animals (Fig. 4A, 4C, arrows).

Differential changes in AMPA receptor subunit expression in chronically C2 hemisected animals

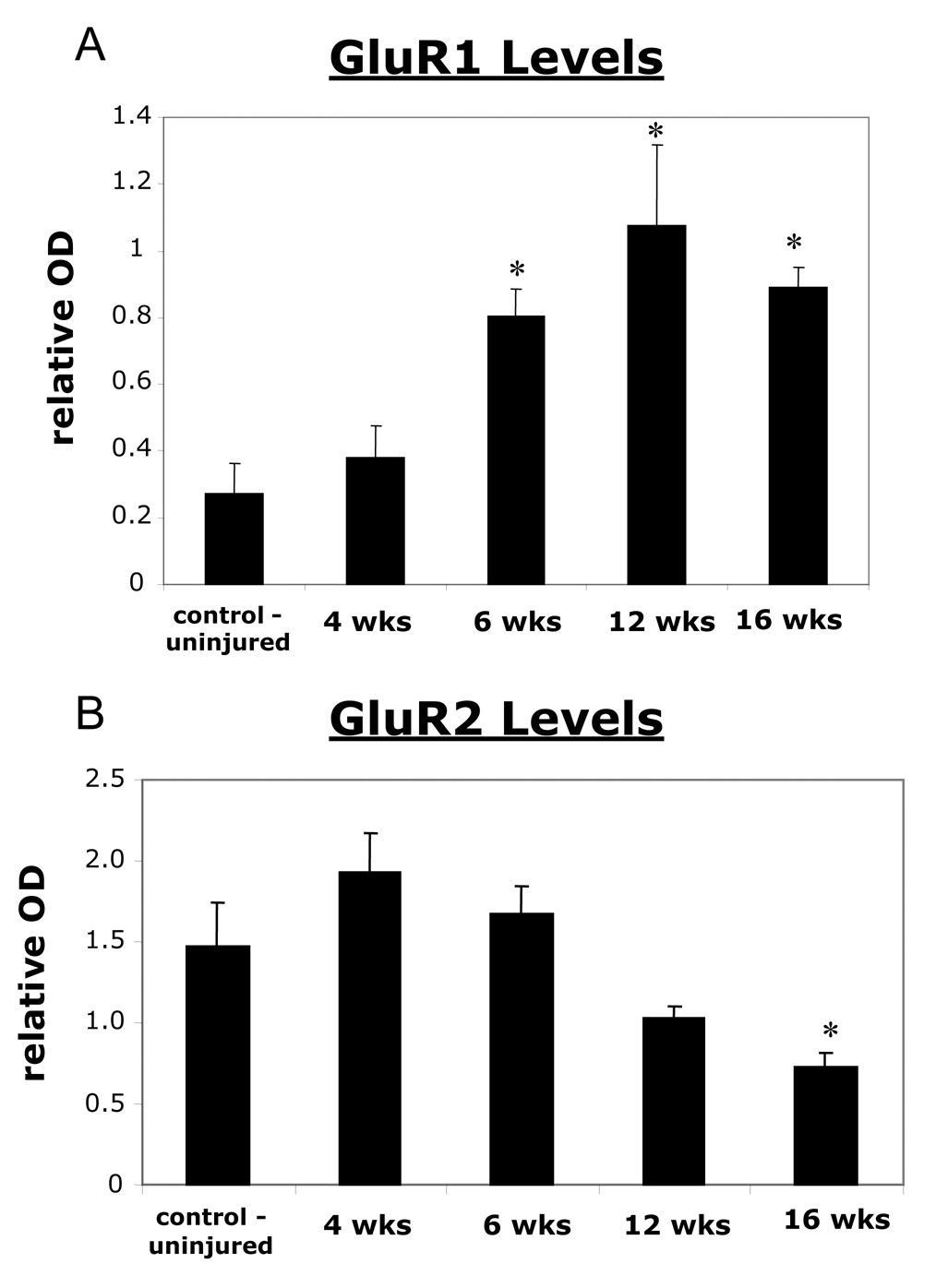

In order to determine if the GluR1 and GluR2 AMPA receptor subunits were increased or decreased along with NR2A upregulation, Western blot analysis for these subunits was performed at the same time points. At the four week time point, there was no significant increase. However, at the six week time point there was a significant increase in the GluR1 AMPA receptor subunit at the C3–C6 spinal cord on the side ipsilateral to the hemisection compared to controls (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, this increase was persistent up to the sixteen week point. For the GluR2 subunit, there were no significant changes four, six, and twelve weeks post injury (Fig. 5B). However, by the sixteen week time point there was a significant decrease over control levels (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. 5A) A graph showing that there is a significant increase of the AMPA GluR1 subunit receptor at 6, 12, and 16 weeks post C2 hemisection following Western blot analysis.

All values are relative to a standard cortical tissue run along side the samples. 5B) A graph showing that there is a down regulation of the AMPA GluR2 subunit which is significantly lower than control at 16 weeks post C2 hemisection. The graph represents GluR2 values quantified through Western blot analysis of control uninjured animals compared to hemisected animals at various time points following injury. All values are relative to a standard cortical tissue run along side the samples. Significant values are reached at sixteen weeks post hemisection. * indicates significance with a p < 0.05.

Differential AMPA receptor subunit regulation in ventral horn motor neurons and phrenic motor neurons after chronic injury

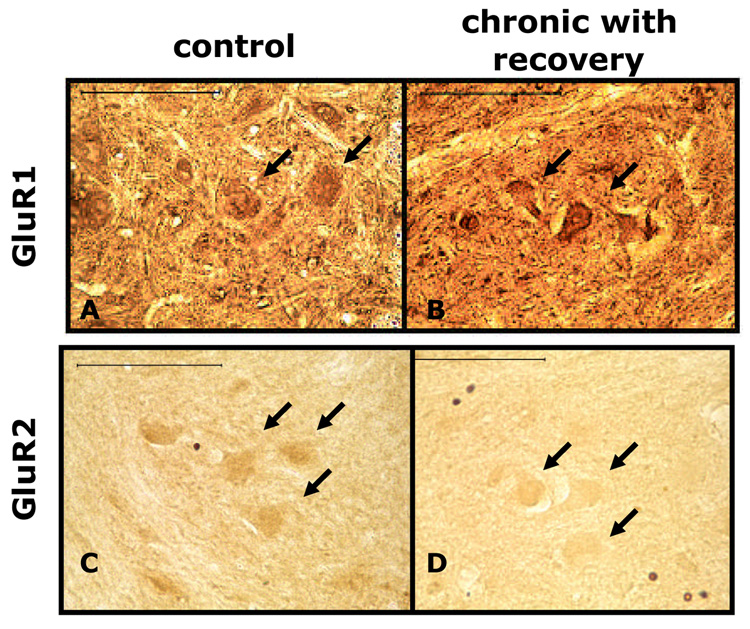

Immunocytochemistry was used to localize the changes of AMPA receptor subunits on ventral horn motor neurons (VMNs) at the C3–C6 spinal cord on the side ipsilateral to the injury. There appeared to be a trend of upregulation of GluR1-DAB immunoreactivity on VMNs of 12 week hemisected animals compared to controls. For the GluR2 subunit, immunocytochemistry suggested that there was a decrease of the protein on the VMNs of chronically injured animals compared to VMNs of control animals.

The area of the phrenic motor nucleus of these sections was delineated exactly as described in the NR2A immunocytochemistry experiments. Results were similar to the results seen on non-specific ventral motor neurons. There appeared to be an increase of GluR1, and a decrease of GluR2-DAB immunoreactivity on the phrenic motor neurons of chronically hemisected animals compared to control (Fig. 6A, 6C).

Figure 6. Light micrographs showing that phrenic motor neurons had increased GluR1 and decreased GluR2 immunoreactivity following chronic C2 hemisection.

A and C are sections from control, non-hemisected rats. B and D are sections from chronic C2 hemisected rats that displayed recovery. A and B are sections processed for GluR1 immunocytochemistry. C and D are sections that have been processed for GluR2 immunocytochemistry. Arrows are pointing to immunoreactive phrenic motor neurons. Note that GluR1 is increased in chronically (12 weeks) injured rats, while GluR2 is decreased in these animals. Scale bars = 100 µm.

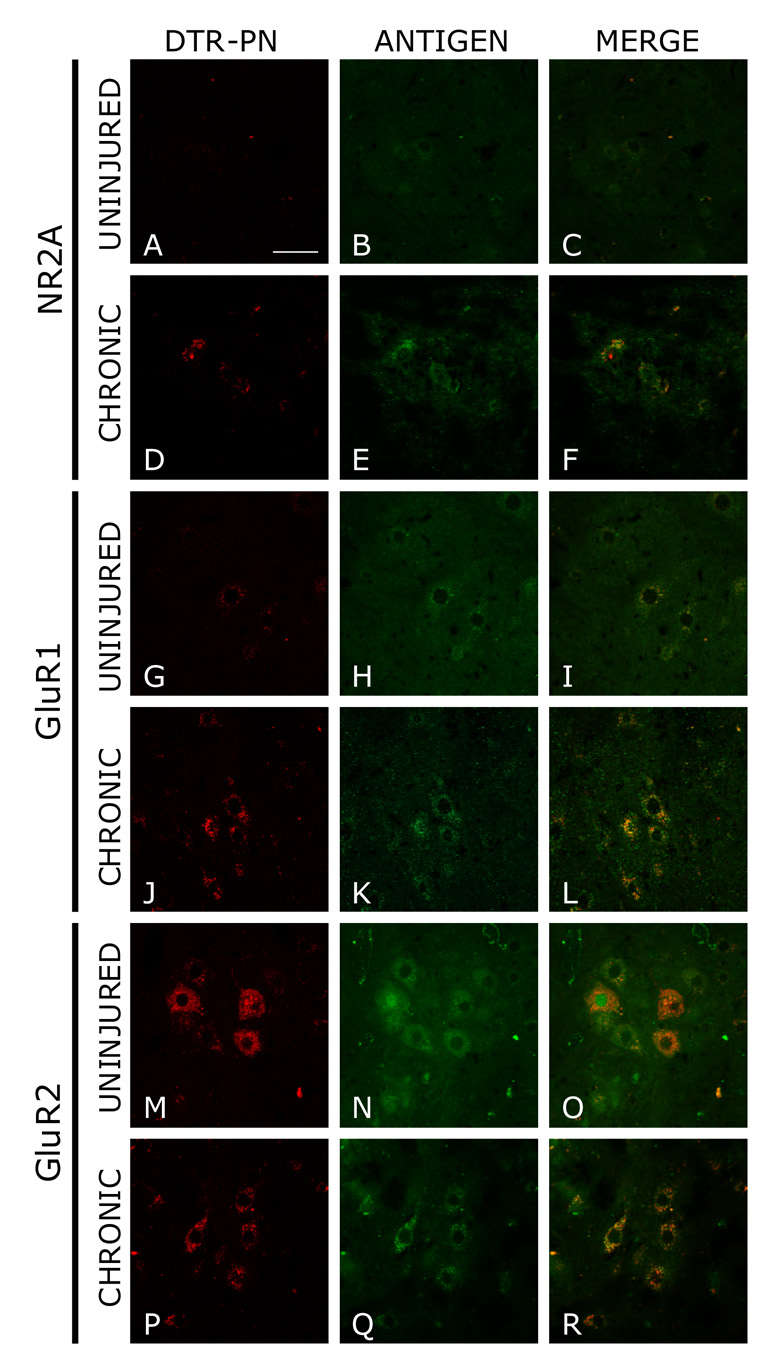

Expression of membrane bound NR2A, GluR1, and GluR2 following chronic injury

With the omission of Triton X-100 in these experiments, phrenic motor neurons ipsilateral to the lesion retrogradely labeled with dextran Texas Red (DTR-PN) (Figs. 7A, 7D, 7G, 7J, 7M, and 7P) exhibited the same characteristics observed in the light microscopy experiments. There appeared to be an upregulation of NR2A and GluR1 in chronic hemisected animals compared to unlesioned control animals (Figs. 7C, 7F, 7I, and 7L). However, there was an apparent down regulation of GluR2 following chronic hemisection (Figs. 7O and 7R).

Figure 7. Immunofluorescent images depicting membrane bound NR2A, GluR1, and GluR2 on phrenic motor neurons retrogradely labeled with dextran Texas red.

A, D, G, J, M, P show phrenic motor neurons labeled with dextran Texas red. The first two rows depict the levels of NR2A on these labeled PMNs. In C and F there appears to be an upregulation of membrane bound NR2A in chronic lesioned animals compared to uninjured animals. The middle two rows show the levels of GluR1 on both chronic lesioned and unlesioned animals. In I and L, membrane bound GluR1 appears to be increased on PMNs. Magnification of all figures is the same and scale bar equals 50 um.

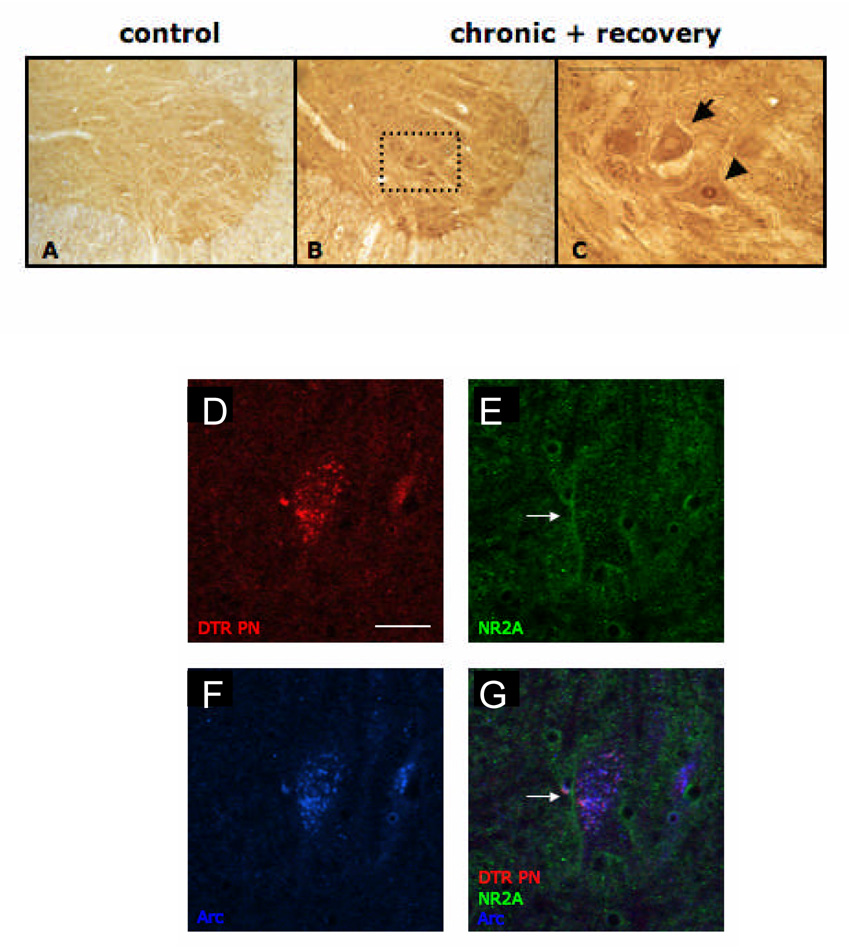

Arc expression and co-localization with NR2A in PMNS of chronically hemisected animals

Qualitatively, immunocytochemistry revealed that activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein (Arc) was highly expressed in PMNs of chronically hemisected animals compared to control animals (Fig. 8A, 8B). Interestingly, Arc protein was expressed either in the cell body, nucleus, or both (Fig. 8C). Triple label immunofluorescence showed that NR2A (green) and Arc (blue) were co-expressed in PMNs retrogradely labeled with Dextran Texas Red after chronic hemisection (Fig. 8D). Furthermore, because Triton X-100 was omitted in the incubation step with the NR2A antibody, it is presumed that NR2A immunoreactivity is extracellular and can be seen in the green outline of the cell body (arrow, Figs. 8E and 8F), whereas Arc immunoreactivity is intracellular, since Triton X-100 is added to the incubation solution in these later steps.

Figure 8. Arc was observed on ventral horn motor neurons following chronic C2 hemisection and was localized on both the cell body and nucleus.

A and B are sections processed for Arc immunoreactivity. A is from a control, non-hemisected rat. B is from a chronic (12 weeks) C2 hemisected rat with spontaneous recovery. In a higher magnification photomicrograph of B (C), it is notable that Arc was localized to both the cell body (arrow) as well as the motor neuron nucleus (arrowhead). Scale bars = 100 µm. D–G) Triple label fluorescent micrographs showing that Arc and NR2A are both expressed in phrenic motor neurons. D is a picture of retrogradely labeled phrenic motor neurons (red). E and F are pictures of NR2A (green) and Arc (blue), respectively. G is an overlay of all three images. Magnification of all immunofluorescent figures is the same and scale bar equals 50 um.

DISCUSSION

The present data have demonstrated that following a C2 hemisection there are significant increases of the NR2A subunit at six and twelve weeks post injury at the ipsilateral C3–C6 level of the spinal cord compared to control animals. The NR2A subunit level decreases to amounts similar to control at sixteen weeks post C2 lesion. Through immunocytochemistry and retrograde WGA-HRP labeling, it was observed qualitatively that the upregulation of NR2A also occurred on PMNs. These changes were also reflected in membrane bound NR2A observed through immunofluorescent techniques.

In addition to these findings there were changes in the subunits of the AMPA receptor. Western Blot analysis showed that there was a significant increase of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR1 at the ipsilateral C3–C6 level of 6, 12, and 16 week hemisected animals compared to control. For the AMPA GluR2 subunit there was no significant difference at four, six, and twelve weeks following injury. However, at 16 weeks post injury, GluR2 levels were significantly less than controls. Following the data obtained from the Western Blot analysis, there was an increase of GluR1 on PM neurons, and a decrease of GluR2 on phrenic motor neurons. These differences in membrane bound GluR1 and GluR2 were also observed.

Glutamate receptor mediated plasticity

These changes in the NR2A and AMPA receptor subunits in the PM nucleus begin to suggest the mechanisms that may mediate the onset of spontaneous functional recovery of the diaphragm in chronic C2 hemisected rats. This study shows that there is an increasing amount of NR2A subunit following chronic C2 spinal cord hemisection. The increase in NR2A is noteworthy because it has been demonstrated by others that NR2A is an essential component of synaptic strengthening in long term potentiation (LTP) (Liu, et al., 2004; Massey, et al., 2004). One result of LTP is the insertion of AMPA receptors to the post-synaptic membrane; one subunit in particular that has been implicated is the GluR1 subunit (Hayashi, et al., 2000).

In our experiments, at and following time points where NR2A was significantly increased, there were changes in the AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2. This is important because it has been demonstrated that the AMPA glutamate receptor is a mediator of the descending respiratory drive to the phrenic nucleus (McCrimmon, et al., 1989 and Liu, et al., 1990). Consistent with our hypothesis, the GluR1 subunit increased following the changes in NR2A. It is possible that the increase in GluR1 could result in an enhanced efficacy of the glutamatergic drive to the phrenic motor nucleus. An increased expression of the GluR1 AMPA receptor subunit mRNA and protein in the spinal cord has been reported previously. In studies investigating pain mechanisms in the spinal cord, it has been reported in the models of diabetic neuropathy and nerve ligation that GluR1 expression is increased (Harris, et al., 1996; Tomiyama, et al., 2005).

Consistent with our hypothesis, the GluR2 subunit decreased similar to other studies investigating trauma and AMPA receptor subunit regulation (Grossman, et al., 1999; Gorter, et al., 1997; Alsbo, et al., 2001). This is noteworthy because the GluR2 subunit is the calcium gate of the AMPA receptor (Hollmann, et al., 1991 and Hume, et al., 1991). AMPA receptor complexes deficient in GluR2 subunits following traumatic insult could potentially result in increased calcium entry, excitoxic insult via the increased intracellular calcium concentration, and cell death – this sequence of events has been termed the “GluR2 hypothesis” (Bennett, et al., 1996). However contrary to this, others have demonstrated that the increased calcium mediated by a decreased presence of GluR2 in the AMPA receptor complex may provide the secondary messenger system needed for plasticity (Gu, et al., 1996; Jia, et al., 1996; Mainen et al., 1998; Meng et al., 2003). The decrease in GluR2 in our model may play the same role and allow for more plasticity to occur at the phrenic motor nucleus.

In another study by our laboratory, it has been observed that treatment with the NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801 to upregulate NR2A protein can lead to hemidiaphragmatic recovery following C2 hemisection (Alilain and Goshgarian, 2007). It is noteworthy to include that MK-801 can enhance long term potentiation in adult rats and the upregulation of NMDA receptors has been suggested as one possible mechanism behind this (Buck et al., 2006).

These changes we observe on the phrenic motor neurons may reflect widespread changes and plasticity that ventral horn motor neurons rostral to the hemisection undergo. As was observed in the studies by Grossman, et al., the changes in NR2A and GluR2 were in whole tissue homogenates and in non-specified ventral horn motor neurons. In our own Western blot analyses, we attempted to limit our experiments to the ventral portion but again there are limitations to the specificity. In the future with the advent of laser micro-disection, more specific analyses of particular neuron groups will be possible. Furthermore, as was observed by Grossman, et al., the changes in the NR2A and Glur2 subunits they saw and which we saw ourselves, were on a timescale different from our own. The differences between our results and theirs may result from the differences in the injury model (contusion vs. hemisection), the level of the spinal cord (thoracic vs. cervical), as well as the fact that we isolated the ventral portion of the spinal cord.

Arc: The link between NR2A and AMPA subunit changes?

One protein that has been implicated as a mediator of synaptic plasticity and possibly the changes we have observed is activity-regulated cytoskeletal associated protein (Arc) (Steward and Worley, 2002). Arc has been identified as an immediate early gene that is immediately transcribed following the onset of synaptic stimulation and LTP induction protocols, and is localized to newly activated excitatory post-synaptic membranes through NMDA receptor activation (Steward, et al., 1998; Steward and Worley, 2001). One role of Arc is to allow for the changes and protein synthesis that is required for modifications at the synapse which is required in long lasting LTP (Guzowski, et al., 2000). Interestingly, another Arc mediated process that has just recently been shown is the delivery of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR4 to the post-synaptic membrane (Mokin, et al., 2006). In addition, other recent findings have indicated that the exact role of Arc in synaptic plasticity is still relatively unknown and more work needs to be done (Chowdhury, et al., 2006, Shepherd, et al., 2006, Verde, et al., 2006). Here we show for the first time that Arc is also co-expressed along with NR2A in ventral horn motor neurons following experimental spinal cord injury.

A working hypothesis: Silent synapses in the phrenic nucleus

There is a striking similarity in what we are proposing as a mechanism of spontaneous motor recovery following chronic spinal cord injury with the mechanism associated with the unmasking of silent synapses during LTP. Described as synapses that display only NMDA receptor activity, the conversion from silent synapses to active ones has been proposed as one possible mechanism of LTP (Isaac, et al., 1995; Petralia, et al., 1999). Two theories have been presented that would show the underlying mechanism of the silent synapse (Rumpel, et al., 1998). One model suggests that there is a pre-synaptic silence where there is little or no glutamate being released (Kimura, et al., 1997). Another model suggests that there is a post-synaptic silence, where there are a few, none, or non-functional AMPA receptors (Isaac, et al., 1995; Liao, et al., 1995; Durand, et al., 1996). Therefore, these silent synapses can be converted to active ones by: 1) increased glutamate release or glutamate spillover from adjacent synapses (Kullmann, et al., 1996; Asztely 1997; Barbour and Hausser 1997); or 2) insertion of more AMPA receptors in the post-synaptic membrane (Rumpel, et al., 1998). It is possible that both models exist in the respiratory pathways.

Chronically following high cervical hemisection, we have shown that changes occur at the level of the phrenic nucleus involving an upregulation of the NR2A subunit of the NMDA receptor which, in other models, initiate synaptic plasticity and LTP-like mechanisms (Liu, et al., 2004; Massey, et al., 2004). Another consequence of hemisection in this study is the synthesis of Arc protein which may result in modifications at the post-synaptic PM neuron site. The induction of Arc could result in the regulation of AMPA receptor subunit synthesis and its delivery to the synapse. This would strengthen synaptic connections in the crossed phrenic pathway and allow for depolarization of phrenic motor neurons during inspiration. Thus the above changes could result in spontaneous recovery of the paretic hemidiaphragm following chronic C2 hemisection in the rat. Another possible mediator in the transformation of silent synapses into functional synapses is serotonin (Li and Zhuo, 1998) as suggested below.

Serotonin modulation of chronic spontaneous recovery

The present report and the hypothetical model proposed above examines the plasticity of the glutamatergic pathway descending to the phrenic motor nucleus. It has been observed by our laboratory and by others that other forms of plasticity are present which may play important roles in the return of hemidiaphragm function following chronic C2 hemisection in rats.

Serotonin (5-HT) levels and 5-HT receptors undergo changes following C2 hemisection and it is important to consider that the plasticity observed in the 5-HT system following chronic C2 hemisection may serve to enable or augment the changes of the glutamate receptors which we observed in this report. In our laboratory we have shown that 30 days following C2 hemisection there is an increase of 5-HT immunoreactive terminals in the phrenic nucleus compared to control animals (Tai Q., et al., 1997). In other laboratories, it has been reported that 5-HT and its receptors are regulated following C2 hemisection. It was shown that after C2 hemisection, 5-HT levels are decreased initially, but there is a recovery of 5-HT levels which is increased over time and reported up to eight weeks (Golder and Mitchell, 2005). In addition to this, there is an upregulation of the 5-HT2A receptor following chronic C2 hemisection, which may contribute to the increased efficacy or activation of the crossed phrenic pathway (Fuller, et al., 2005) since 5-HT2A receptor activation can lead to the induction of the crossed phrenic pathway (Zhou, et al., 2001).

Conclusion

In summary, this report only begins to uncover the underlying mechanisms which may mediate spontaneous functional recovery following C2 hemisection. A potential role for the NR2A, GluR1 and GluR2 subunits, as well as the immediate early gene Arc protein, in mediating synaptic plasticity in the PM nucleus has been suggested. Understanding the roles of these receptors and their regulation following injury may prove to be beneficial in exploring new avenues of therapy following traumatic spinal cord injury.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH Grant HD 31550 (HGG).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Warren J. Alilain, Cellular and Clinical Neurobiology Program, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Wayne State University School of Medicine, 540 E. Canfield, Detroit, MI 48201.

Harry G. Goshgarian, Cellular and Clinical Neurobiology Program, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences and Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, 540 E. Canfield, Detroit, MI 48201.

REFERENCES

- Alilain WJ, Goshgarian HG. MK-801 upregulates NR2A protein levels and induces functional recovery of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm following acute C2 hemisection in adult rats. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:346–354. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2007.11753950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsbo CW, Wrang ML, Moller F, Diemer NH. Is the AMPA receptor subunit GluR2 mRNA an early indicator of cell fate after ischemia? A quantitative single cell RT-PCR study. Brain Res. 2001;894:101–108. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)01985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asztely F, Erdemli G, Kullmann DM. Extrasynaptic glutamate spillover in the hippocampus: dependence on temperature and the role of active glutamate uptake. Neuron. 1997;18:281–293. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour B, Hausser M. Intersynaptic diffusion of neurotransmitter. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:377–384. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)20050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MV, Pellegrini-Giampietro DE, Gorter JA, Aronica E, Connor JA, Zukin RS. The GluR2 hypothesis: Ca(++)-permeable AMPA receptors in delayed neurodegeneration. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1996;61:373–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank T, Zwart R, Nijholt I, Spiess J. Serotonin 5-HT2 receptor activation potentiates N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated ion currents by a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci Res. 1996;45:153–160. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960715)45:2<153::AID-JNR7>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck N, Cali S, Behr J. Enhancement of long-term potentiation at CA1-subiculum synapses in MK-801-treated rats. Neurosci Lett. 2006;392:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitravanshi VC, Sapru HN. NMDA as well as non-NMDA receptors mediate the neurotransmission of inspiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons in the adult rat. Brain Res. 1996;715:104–112. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01565-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand GM, Kovalchuk Y, Konnerth A. Long-term potentiation and functional synapse induction in developing hippocampus. Nature. 1996;381:71–75. doi: 10.1038/381071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban JA. AMPA receptor trafficking: A roadmap for synaptic plasticity. Molecular Interventions. 2003;3:375–385. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.7.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Baker-Herman TL, Golder FJ, Doperalski NJ, Watters JJ, Mitchell GS. Cervical spinal cord injury upregulates ventral spinal 5-HT2A receptors. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:203–213. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ, Mitchell GS. Spinal synaptic enhancement with acute intermittent hypoxia improves respiratory function after chronic cervical spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2925–2932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0148-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter JA, Petrozzino JJ, Aronica EM, Rosenbaum DM, Opitz T, Bennett MV, Connor JA, Zukin RS. Global ischemia induces downregulation of Glur2 mRNA and increases AMPA receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx in hippocampal CA1 neurons of gerbil. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1779–1788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06179.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian HG, Guth L. Demonstration of functionally ineffective synapses in the guinea pig spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 1977;57:613–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(77)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian HG. The crossed phrenic phenomenon: a model for plasticity in the respiratory pathways following spinal cord injury. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:795–810. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00847.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SD, Wolfe BB, Yasuda RP, Wrathall JR. Alterations in AMPA receptor subunit expression after experimental spinal cord contusion injury. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5711–5720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05711.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SD, Wolfe BB, Yasuda RP, Wrathall JR. Changes in NMDA receptor subunit expression in response to contusive spinal cord injury. J Neurochem. 2000;75:174–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu JG, Albuquerque C, Lee CJ, MacDermott AB. Synaptic strengthening through activation of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors. Nature. 1996;381:793–796. doi: 10.1038/381793a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, Lyford GL, Stevenson GD, Houston FP, McGaugh JL, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Inhibition of activity-dependent arc protein expression in the rat hippocampus impairs the maintenance of long-term potentiation and the consolidation of long-term memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3993–4001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-03993.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Corsi M, Quartaroli M, Arban R, Bentivoglio M. Upregulation of spinal glutamate receptors in chronic pain. Neuroscience. 1996;74:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Shi SH, Esteban JA, Piccini A, Poncer JC, Malinow R. Driving AMPA receptors into synapses by LTP and CaMKII: requirement for GluR1 and PDZ domain interaction. Science. 2000;287:2262–2267. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hestrin S. Activation and desensitization of glutamate-activated channels mediating fast excitatory synaptic currents in the visual cortex. Neuron. 1992;9:991–999. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90250-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann M, Hartley M, Heinemann S. Ca2+ permeability of KA-AMPA--gated glutamate receptor channels depends on subunit composition. Science. 1991;252:851–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1709304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume RI, Dingledine R, Heinemann SF. Identification of a site in glutamate receptor subunits that controls calcium permeability. Science. 1991;253:1028–1031. doi: 10.1126/science.1653450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JT, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Evidence for silent synapses: implications for the expression of LTP. Neuron. 1995;15:427–434. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Moriyoshi K, Sugihara H, Sakurada K, Kadotani H, Yokoi M, Akazawa C, Shigemoto R, Mizuno N, Masu M, Nakanishi S. Molecular characterization of the family of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2836–2843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z, Agopyan N, Miu P, Xiong Z, Henderson J, Gerlai R, Taverna FA, Velumian A, MacDonald J, Carlen P, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder J. Enhanced LTP in mice deficient in the AMPA receptor GluR2. Neuron. 1996;17:945–956. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura F, Otsu Y, Tsumoto T. Presynaptically silent synapses: spontaneously active terminals without stimulus-evoked release demonstrated in cortical autapses. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2805–2815. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.5.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp JJ, Vissel B, Heinemann SF, Westbrook GL. N-terminal domains in the NR2 subunit control desensitization of NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1998;20:317–327. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM, Erdemli G, Asztely F. LTP of AMPA and NMDA receptor-mediated signals: evidence for presynaptic expression and extrasynaptic glutamate spill-over. Neuron. 1996;17:461–474. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Zhou M. Silent glutamatergic synapses and nociception in mammalian spinal cord. Nature. 1998;393:695–698. doi: 10.1038/31496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Hessler NA, Malinow R. Activation of postsynaptically silent synapses during pairing-induced LTP in CA1 region of hippocampal slice. Nature. 1995;375:400–404. doi: 10.1038/375400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Feldman JL, Smith JC. Excitatory amino acid-mediated transmission of inspiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:423–436. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wong TP, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Wang Y, Sheng M, Auberson YP, Wang YT. Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 2004;304:1021–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.1096615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainen ZF, Jia Z, Roder J, Malinow R. Use-dependent AMPA receptor block in mice lacking GluR2 suggests postsynaptic site for LTP expression. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:579–586. doi: 10.1038/2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey PV, Johnson BE, Moult PR, Auberson YP, Brown MW, Molnar E, Collingridge GL, Bashir ZI. Differential roles of NR2A and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in cortical long-term potentiation and long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7821–7828. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1697-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrimmon DR, Speck DF, Feldman JL. Involvement of excitatory amino acids in neurotransmission of inspiratory drive to spinal respiratory motoneurons. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1910–1921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-06-01910.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Zhang Y, Jia Z. Synaptic transmission and plasticity in the absence of AMPA glutamate receptor GluR2 and GluR3. Neuron. 2003;39:163–176. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM. Tetramethyl benzidine for horseradish peroxidase neurohistochemistry: a non-carcinogenic blue reaction product with superior sensitivity for visualizing neural afferents and efferents. J Histochem Cytochem. 1978;26:106–117. doi: 10.1177/26.2.24068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokin M, Lindahl JS, Keifer J. Immediate-early gene-encoded protein Arc is associated with synaptic delivery of GluR4-containing AMPA receptors during in vitro classical conditioning. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:215–224. doi: 10.1152/jn.00737.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H, Sprengel R, Schoepfer R, Herb A, Higuchi M, Lomeli H, Burnashev N, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. Heteromeric NMDA receptors: molecular and functional distinction of subtypes. Science. 1992;256:1217–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H, Burnashev N, Laurie DJ, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1994;12:529–540. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno DE, Yu XJ, Goshgarian HG. Identification of the axon pathways which mediate functional recovery of a paralyzed hemidiaphragm following spinal cord hemisection in the adult rat. Exp Neurol. 1992;116:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(92)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyoshi K, Masu M, Ishii T, Shigemoto R, Mizuno N, Nakanishi S. Molecular cloning and characterization of the rat NMDA receptor. Nature. 1991;354:31–37. doi: 10.1038/354031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantwi KD, El Bohy A, Schrimsher GW, Reier PJ, Goshgarian HG. Spontaneous Functional Recovery in Paralyzed Hemidiaphragm Following Upper Cervical Spinal Cord Injury in Adult Rats. Neurorehabilitation and Repair. 1999;13:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Patneau DK, Mayer ML. Structure-activity relationships for amino acid transmitter candidates acting at N-methyl-D-aspartate and quisqualate receptors. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2385–2399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-07-02385.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petralia RS, Esteban JA, Wang YX, Partridge JG, Zhao HM, Wenthold RJ, Malinow R. Selective acquisition of AMPA receptors over postnatal development suggests a molecular basis for silent synapses. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:31–36. doi: 10.1038/4532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts RF. The respiratory center and its descending pathways. J Comp Neurol. 1940;72:605–625. [Google Scholar]

- Porter WT. The path of the respiratory impulse from the bulb to the phrenic nuclei. J Physiol. 1895;17:455–485. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1895.sp000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S, Neuman RS. Activation of 5-HT2 receptors facilitates depolarization of neocortical neurons by N-methyl-D-aspartate. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;231:347–354. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90109-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Wong TP. Distribution of N-methyl-D-aspartate and non-N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptor subunits on respiratory motor and premotor neurons in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;389:94–116. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971208)389:1<94::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpel S, Hatt H, Gottmann K. Silent synapses in the developing rat visual cortex: evidence for postsynaptic expression of synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8863–8874. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08863.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeburg PH, Burnashev N, Kohr G, Kuner T, Sprengel R, Monyer H. The NMDA receptor channel: molecular design of a coincidence detector. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1995;50:19–34. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571150-0.50006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Wallace CS, Lyford GL, Worley PF. Synaptic activation causes the mRNA for the IEG Arc to localize selectively near activated postsynaptic sites on dendrites. Neuron. 1998;21:741–751. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Worley PF. Selective targeting of newly synthesized Arc mRNA to active synapses requires NMDA receptor activation. Neuron. 2001;30:227–240. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Worley P. Local synthesis of proteins at synaptic sites on dendrites: role in synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation? Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;78:508–527. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai Q, Palazzolo KL, Goshgarian HG. Synaptic plasticity of 5-hydroxytryptamine-immunoreactive terminals in the phrenic nucleus following spinal cord injury: a quantitative electron microscopic analysis. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:613–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YP, Shimizu E, Dube GR, Rampon C, Kerchner GA, Zhuo M, Liu G, Tsien JZ. Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature. 1999;401:63–69. doi: 10.1038/43432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama M, Furusawa K, Kamijo M, Kimura T, Matsunaga M, Baba M. Upregulation of mRNAs coding for AMPA and NMDA receptor subunits and metabotropic glutamate receptors in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord in a rat model of diabetes mellitus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;136:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SY, Basura GJ, Goshgarian HG. Serotonin(2) receptors mediate respiratory recovery after cervical spinal cord hemisection in adult rats. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:2665–2673. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]