Abstract

In natural and engineered systems, cis-RNA regulatory elements such as riboswitches are typically found within untranslated regions rather than within the protein coding sequences of genes. However, RNA sequences with important regulatory roles can exist within translated regions. Here, we present a synthetic riboswitch that is encoded within the translated region of a gene and represses Escherichia coli gene expression greater than 25-fold in the presence of a small-molecule ligand. The ability to encode riboswitches within translated regions as well as untranslated regions provides additional opportunities for creating new genetic control elements. Furthermore, evidence that a riboswitch can function in the translated region of a gene suggests that future efforts to identify natural riboswitches should consider this possibility.

Keywords: riboswitch, synthetic biology

INTRODUCTION

For nearly a decade, riboswitches have been described as genetic control elements located in an untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA that modulate transcription or translation upon binding a specific ligand or metabolite (Nudler and Mironov 2004). This perspective has frequently guided bioinformatics efforts to identify natural riboswitches (Barrick and Breaker 2007), as well as experimental efforts to develop synthetic riboswitches (Werstuck and Green 1998; Bauer and Suess 2006). Previous work has revealed that bacterial riboswitches that act on a translational level often regulate gene expression through ligand-dependent structural changes in the 5′-UTR that provide or limit access to the ribosome binding site (RBS) of an RNA transcript (Nudler and Mironov 2004). This insight has inspired efforts to convert synthetic aptamers into riboswitches through rational engineering (Werstuck and Green 1998; Desai and Gallivan 2004; Suess 2005) or genetic screens and selections (Lynch et al. 2007; Topp and Gallivan 2008; Weigand et al. 2008). Here, we report that synthetic riboswitches that modulate translation in bacteria can be located within the coding region of a gene and that opportunities for developing new riboswitches may be enhanced by placing fewer restrictions on the expected mechanisms of RNA-based genetic regulation.

We have previously reported several high-throughput screening methods that can identify synthetic riboswitches that modulate gene expression in Escherichia coli cells (Lynch et al. 2007; Topp and Gallivan 2008), and we have used the resulting switches to control cell behavior in a ligand-dependent fashion (Topp and Gallivan 2007). Additionally, the screens revealed that our switches activated gene expression by providing access to the RBS in the presence of ligand and suggested that the ligand is more likely to activate, rather than to repress, gene expression for the average library member (S. Topp, S.A. Lynch, and J.P. Gallivan, unpubl.). However, a given aptamer should theoretically be useful for developing riboswitches that either activate or repress gene expression. For example, the Bacillus subtilis xpt and ydhl riboswitches (Serganov et al. 2004), as well as the Vibrio vulnificus add riboswitch (Mandal and Breaker 2004), employ aptamers that bind their purine ligands in nearly identical binding pockets, yet they modulate gene expression by transcriptional termination, transcriptional antitermination, and translational activation, respectively. Because it should be possible to construct riboswitches that enhance or repress gene expression from a single aptamer yet our previous work failed to identify synthetic riboswitches that repress gene expression in the presence of the ligand, we sought to develop libraries that would allow us to identify such switches. Achieving this goal would provide further insight into the mechanisms by which synthetic riboswitches can be used to regulate gene expression and would enhance our knowledge of riboswitch construction. Moreover, there will be increased flexibility in efforts to reprogram cell behavior with RNA (Gallivan 2007) if a single aptamer can be used to develop switches that either activate or repress gene expression.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We have shown in several recent studies that theophylline-sensitive riboswitches can be isolated from genetic libraries in which a fully randomized region of 8–12 bases is positioned between the mTCT8-4 theophylline aptamer (Jenison et al. 1994) and the start codon of a reporter gene (Lynch et al. 2007; Topp and Gallivan 2008). These switches activated gene expression by changing the RNA from a conformation in which the RBS was paired in the absence of ligand to one in which the RBS was unpaired in the presence of theophylline (Lynch et al. 2007). Because many sequences in these libraries showed theophylline-dependent gene activation but none exhibited significant (>5-fold) gene repression in the presence of theophylline (S. Topp, S.A. Lynch, and J.P. Gallivan, unpubl.), we hypothesized that the combinatorial library might be rationally redesigned to increase the frequency of sequences that repress gene expression in the presence of ligand.

Positioning the RBS in the aptamer stem reveals theophylline-dependent repression

To bias our combinatorial library toward riboswitches that could repress gene expression in the theophylline-bound state, we introduced two major changes that distinguish our new strategy from our previously reported library design (Fig. 1A). First, the RBS was incorporated within the aptamer structure in a region that is expected to be paired when theophylline is bound. Specifically, we observed that swapping two pairs of bases within the stem of the mTCT8-4 aptamer would position a potential RBS within the 3′ stem of the aptamer (Fig. 1B). Because the structure and function of the aptamer has been well studied, it was apparent that the base pair swap in the aptamer stem would not perturb ligand binding significantly (Zimmermann et al. 1998).

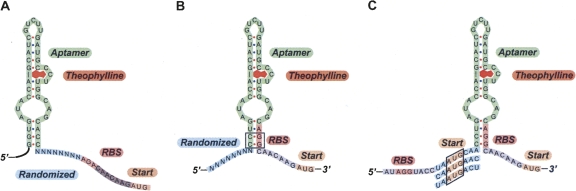

FIGURE 1.

Sequences of RNA transcripts for each library or switch. (A) A previously reported genetic library to screen for “on” switches features a fully randomized region of 8 bases (blue) positioned between the mTCT8-4 theophylline aptamer (green) and the start codon (orange) of a reporter gene (Lynch et al. 2007; Topp and Gallivan 2008). A constant region (gray) was positioned between the RBS and the start codon to provide appropriate spacing for efficient translation. (B) A modified library to screen for “off” switches contains a randomized library of 8 bases (blue) positioned 5′ to the aptamer (green). Two pairs of bases were swapped in the aptamer stem (boxed) to move the RBS (pink) to the stem. (C) Three fivefold repressors were identified in the screen. The unintentional RBS (pink) is positioned 5′ to the selected sequences (blue). The old and new (boxed) start codons are shown in orange.

The second modification to our previous libraries involved positioning the 8-nucleotide randomized region immediately 5′ to the aptamer, rather than after the aptamer (Lynch et al. 2007; Topp and Gallivan 2008). We anticipated that in the absence of theophylline, some of the library members would have sequences in which the nucleotides in the randomized region could pair with the 5′ portion of the aptamer, causing the aptamer stem to become unpaired, and therefore making the RBS more accessible for translation (Fig. 1B). We hypothesized that these same sequences could exhibit repressed gene expression in the presence of ligand, since the RBS would become less accessible in the theophylline-bound conformation. To evaluate this hypothesis, we used a simple screen to determine if the redesigned library contained riboswitches that repress gene expression in the presence of theophylline.

To select for sequences with high gene expression in the absence of ligand, we cloned the library into the 5′-UTR of the cat reporter gene, which confers resistance to the antibiotic chloramphenicol, and selected clones that grew without theophylline on media containing the antibiotic. Plasmid DNA was extracted from the pool of cells that survived the chloramphenicol selection, and the region containing the randomized bases and aptamer was subcloned upstream of the lacZ reporter gene. To screen for clones with low gene expression in the presence of ligand, E. coli were transformed with this pool and plated on selective media containing X-gal and 1 mM theophylline. Ninety-four light-blue colonies were picked and grown in liquid culture to compare gene expression in the presence and absence of theophylline. These clones no longer exhibited a bias toward theophylline-dependent gene activation, and several repressed gene expression approximately fivefold when grown in 1 mM theophylline.

Plasmid DNA was extracted from these clones for sequencing analysis, which revealed that each of the riboswitches had a different N8 sequence. To our surprise, all three had an in-frame ATG sequence at the same position within the N8 region. It appeared that the coincidental presence of an AGG sequence several bases 5′ to the N8 library may act as an RBS to provide an unintended opportunity for start codons to be selected in the randomized region. Thus, each of the theophylline-dependent repressors has two potential translational start sites, with one positioned 5′ to the aptamer and the other positioned 3′ to the aptamer (Fig. 1C).

Removal of the ATG codon 3′ to the aptamer improves gene repression

Because three unique clones contained an in-frame ATG sequence 5′ to the aptamer, we hypothesized that the initiation codon 3′ to the aptamer may not play a role in repression and that removing it may improve the performance of the synthetic riboswitches by decreasing gene expression in the ligand-bound state. To test this idea using the three switches, we replaced the start codon following the aptamer with a 32-member NNY library, where Y (pyrimidine) was used to exclude purines from the third position to eliminate the possibility of start and stop codons in the sequence (Fig. 2). We assayed 23 random clones from the pool and found that the switches could be improved by mutating the ATG codon located 3′ to the aptamer. Generally, the level of gene expression in the presence of theophylline was reduced significantly, while the gene expression in the absence of theophylline remained relatively unchanged, indicating that the in-frame ATG preceding the aptamer is likely the site of translation initiation for these synthetic riboswitches. The most significant improvement arising from one of the parent fivefold repressors was for a specific NNY sequence (TAT) that now enabled 27-fold repression of gene expression in E. coli (Fig. 3). Half-maximal repression is observed at an extracellular theophylline concentration of ∼300 μM. Previous work suggests that the corresponding intracellular concentration of theophylline can be estimated to be ∼200 nM (Koch 1956), which falls within the margin of error for the reported KD of the aptamer (310 ± 130nM) as determined by in vitro studies (Jenison et al. 1994).

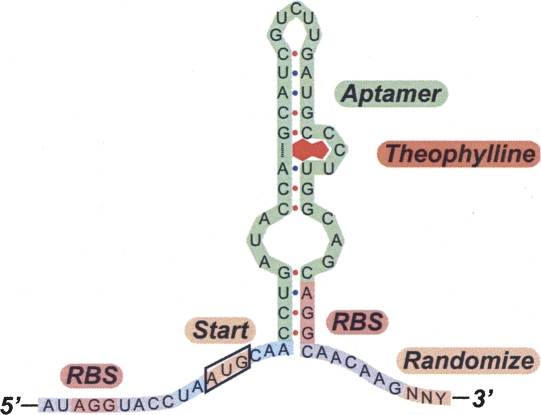

FIGURE 2.

The original start codon located 3′ to the aptamer was randomized to NNY (orange) to exclude purines from the third position to eliminate the possibility of start and stop codons in the sequence.

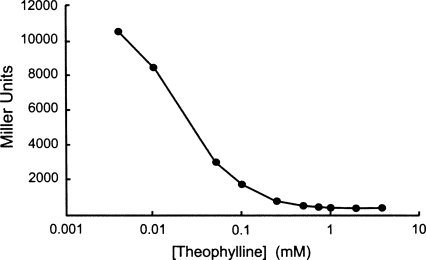

FIGURE 3.

To assess the repression profile of the 27-fold repressor over a range of concentrations, we grew cells harboring the riboswitch in media containing increasing concentrations of theophylline and plotted these data on a semi-log scale. Cells grown in the absence of theophylline (0 mM) express very high levels of β-galactosidase and grow slowly. The errors (±SEM) are less than the size of the symbols.

To verify the theophylline dependence of the new repressor, we assayed its performance in E. coli cells that were grown at various concentration of caffeine, which is structurally similar to theophylline but binds the aptamer 10,000-fold less tightly (Jenison et al. 1994). As expected, gene expression remained unrepressed for all caffeine concentrations tested (0–2 mM). To further demonstrate the ligand dependence of the riboswitch, we introduced a previously verified point mutation (C27A) to the aptamer that significantly reduces its affinity for theophylline but permits binding of 3-methylxanthine (Soukup et al. 2000; Desai and Gallivan 2004). The mutated repressor exhibited high levels of gene expression when cells were grown in the absence of ligand or in the presence of 1 mM theophylline, while gene expression was reduced to one tenth of the unrepressed levels when cells were grown in the presence of 1 mM 3-methylxanthine (11,000, 11,000, and 910 Miller Units, respectively). These results demonstrate that our repressor modulates gene expression through specific RNA-ligand interactions.

The ATG 5′ to the aptamer is critical for riboswitch function

To determine whether the ATG codon 5′ to the aptamer acts as the initiation codon, we mutated the codon to NTG for our best “off” switch and assayed each of the four possible clones for gene expression when cells were grown in 0 mM and 1 mM theophylline. The data show that the switch is nonfunctional for all codons other than ATG, as gene expression in the absence of ligand is abolished to below the level of the repressed parent switch (Fig. 4). This result provides support toward the conclusion that the ATG 5′ to the aptamer is the source of translation initiation and suggested that our initial design was superseded by the plasticity of biological systems presented with genetic variation and exposed to selective pressures.

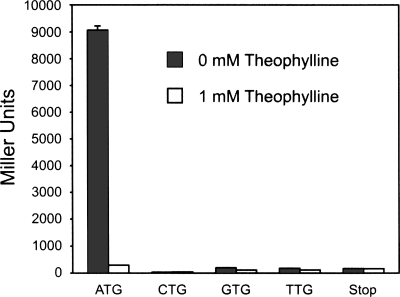

FIGURE 4.

A single point mutation to remove the start codon 5′ to the aptamer abolishes gene expression to below the level of the repressed parent switch. Additionally, a different point mutant in which the triplet immediately following the ATG was converted to a stop codon exhibits low expression levels regardless of whether theophylline is present in the growth media.

To further verify that the start codon 5′ to the aptamer is responsible for riboswitch function, we introduced a different point mutation to our best “off” switch to convert the triplet immediately following the ATG to a stop codon. We suspected that gene expression levels for this construct with and without ligand would be similar to the expression levels of the mutants lacking a start codon 5′ to the aptamer. Indeed, this point mutant exhibited low expression levels regardless of whether theophylline was present in the growth media, providing additional support for our hypothesis. (Fig. 4)

Mass spectrometry shows that the riboswitch is translated

Despite strong genetic support that translation begins before the aptamer based on data showing loss of function for various mutants, we sought to obtain direct evidence that our best “off” riboswitch was located within the translated region using mass spectrometry. We cloned the 27-fold repressor upstream of a gene encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP) with a C-terminal polyhistidine tag. To facilitate modular cloning of our riboswitches, each reporter gene is preceded by and translationally fused to a short (∼70 amino acids), nonfunctional portion of the IS10 transposase gene (Kwon et al. 1995). As this portion of the IS10 transposase protein contains a known post-translational cleavage site (Kwon et al. 1995), we removed the cleavage site to obtain the full-length protein for mass spectrometry analysis (see Materials and Methods).

As expected, when cells expressing this construct were grown with and without theophylline, only the cells grown in the absence of ligand were fluorescent. To determine whether the identity of the expressed protein corresponded to the amino acid sequence that would be anticipated if translation were initiated at the ATG before the aptamer, we used Ni2+-affinity chromatography to purify the histidine-tagged fluorescent protein and performed an in-gel trypsin digest (Shevchenko et al. 1996), followed by tandem mass spectrometry of the resulting peptides (liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry) (Peng and Gygi 2001). The expected N-terminal peptide was identified through this analysis (see Supplemental Data), confirming that the riboswitch is translated in the unrepressed state of the switch as a fusion to the reporter gene. This result verified the previous conclusions that the riboswitch is part of the coding region rather than within the 5′-UTR.

While the presence of a post-translational cleavage site between the aptamer and the reporter gene for our repressors was an artifact of previous work, we note that it may be useful to engineer such a site immediately before the gene of interest in future efforts to create new riboswitches. Taking such a step might expand the potential number of genes that could be modulated by this mechanism to beyond those that tolerate translational fusions. Moreover, the amino acid sequence encoded by a given aptamer may not always produce a stable, folded protein. Therefore, encoding for post-translational removal of the leading peptide by introducing a protease cleavage site may provide enhanced stability to the protein of interest.

Concluding remarks

We began this study to investigate how combinatorial libraries that were biased toward activating gene expression could be redesigned in order to identify riboswitches that repress gene expression in a ligand-dependent fashion. Through this effort, genetic selection revealed an unexpected, yet simple mechanism by which small-molecule ligands can repress gene expression in the context of synthetic riboswitches. This result serves as a reminder that biological systems often resort to unanticipated mechanisms when selective pressures are applied. Moreover, efforts to identify new RNA motifs that are modulated by ligands in natural systems may fail to detect entire classes of sequences if we remain limited to the conventional perspective that riboswitches are found within noncoding regions of RNA.

As it becomes increasingly straightforward to develop synthetic aptamers that bind new ligands using in vitro selection methods, it would be highly desirable to convert these aptamers into riboswitches with a simple procedure such as cloning the aptamer immediately downstream of a start codon. If this mechanism of gene repression could be extended to a variety of synthetic aptamers, opportunities to engineer metabolism, create new genetic circuits, and control a variety of cell behaviors would be enhanced significantly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthetic oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. Culture media was obtained from EMD Bioscience. Theophylline, o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG), ampicillin, and chloramphenicol were purchased from Sigma. X-gal was purchased from US Biological. DNA polymerase, restriction enzymes, and the pUC18 cloning vector were purchased from New England BioLabs. Plasmid manipulations were performed using E. coli TOP10F′ cells (Invitrogen) that were transformed by electroporation. Purifications of plasmid DNA, PCR products, and enzymatic digestions were performed by using kits from Qiagen. All new plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing performed by MWG Biotech.

Construction and screening of genetic libraries

To construct the library shown in Figure 1B, a forward primer that includes the 5′ KpnI site and extends to within the IS10 coding region was used with a reverse primer that anneals to the IS10 fusion region and contains a HindIII restriction site. The PCR product was digested with KpnI and HindIII, and the insert was cloned between the same restriction sites within a pUC18-based vector containing the cat gene, which confers resistance to the antibiotic chloramphenicol. Electrocompetent TOP10F′ cells were transformed with the library and plated at high density on media containing ampicillin to select for the pUC-based plasmid. To determine the approximate library size, a small aliquot of the original transformation was diluted and plated separately to reveal that the high-density plate contained ∼220,000 clones. Cells from the high-density plate were scraped into liquid culture and were replated on media without theophylline but containing ampicillin (50 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (100 or 150 μg/mL).

Cells from each plate were scraped into separate tubes and grown in liquid culture with ampicillin (50 μg/mL). Plasmid DNA was extracted from each culture and digested with KpnI and HindIII. Each library of inserts was cloned in front of a lacZ reporter gene in a previously reported pUC18-based vector (Desai and Gallivan 2004) that was digested with the same enzymes. TOP10F′ cells were transformed with these libraries, and cells were plated on media containing ampicillin, X-gal, and 1 mM theophylline. To identify clones that were repressed in the presence of ligand, 47 light blue clones were picked from each plate (after preselection with 100 or 150 μg/mL chloramphenicol) and were assayed by hand in 96-well plate format, as previously described. The three clones with fivefold repression were subcultured, and plasmid was extracted for sequencing analysis.

Mutation of the ATG codon 3′ to the aptamer

To construct the library shown in Figure 2, cassette-based PCR mutagenesis was performed with each of the three plasmids using inner primers that anneal to the region of interest to introduce the NNY library and outer primers that anneal to the regions just beyond the KpnI and HindIII sites. The three fully assembled PCR products were pooled and digested with KpnI and HindIII, and the library of inserts was cloned in front of the lacZ reporter gene in a pUC18-based vector that was digested with the same enzymes. TOP10F′ cells were transformed with this pooled library, and cells were plated on selective media. Twenty-three clones were picked at random and assayed by hand in plate-based format, as previously described (Lynch et al. 2007). Clones with greater than fivefold repression were subcultured and verified by assaying a larger culture volume, as previously described. Plasmids were extracted for sequencing analysis.

Mutation of the ATG codon 5′ to the aptamer

To construct the “NTG” clones, a forward primer that includes the 5′ KpnI site, introduces the NTG mutation, and extends into the aptamer sequence was used with a reverse primer that anneals to the IS10 fusion region and contains a HindIII restriction site. The PCR product was digested with KpnI and HindIII, and the insert was cloned in front of the lacZ reporter gene in a pUC18-based vector that was digested with the same enzymes. TOP10F′ cells were transformed with the four-member library, and cells were plated on selective media. Ten clones were picked and grown in liquid media. DNA was extracted from these cultures, revealing that each of the four clones was isolated at least once. The clones were subcultured and assayed by hand.

To convert the triplet immediately following the 5′ ATG to a stop codon, a forward primer that includes the 5′ KpnI site, introduces the point mutation, and extends into the aptamer sequence was used with a reverse primer that anneals to the IS10 fusion region and contains a HindIII restriction site. The PCR product was digested with KpnI and HindIII and cloned in front of the lacZ reporter gene as above. Single clones were picked and grown in liquid media. After confirmation by sequencing analysis, the construct was assayed by hand, as previously described (Lynch et al. 2007).

Preparations for mass spectrometry analysis

To determine whether the riboswitch is located within the coding region using mass spectrometry, a translational fusion was first constructed between the ∼70-amino acid portion of the IS10 gene and GFPuv. To clone GFPuv into the vector containing the 27-fold repressor, pGFPuv was used as a template for a forward primer containing a HindIII site and a reverse primer that makes a silent mutation to remove a SacI site within the GFPuv coding region, adds a C-terminal hexahistidine tag and a stop codon at the end of the gene, and adds a 3′ SacI site for cloning purposes. The SDS-PAGE results and mass spectrometry data suggested, and the literature confirmed (Kwon et al. 1995), that the IS10 fusion protein contains a protease-sensitive post-translational cleavage site. Because the purified protein lacked its N terminus because of post-translational cleavage, we used this vector to make a modified version of the construct with a shortened IS10 fusion.

To remove the protease-sensitive site, the 27-fold repressor was amplified with a forward primer that includes the 5′ KpnI site and a reverse primer that contains a HindIII restriction site and anneals to a short sequence at the beginning of the IS10 gene. The PCR product and the GFP construct described above were digested with KpnI and HindIII, and the insert containing the repressor and shortened IS10 fusion was cloned into the vector containing the histidine-tagged GFPuv gene. TOP10F′ cells were transformed with this ligation, and cells were plated on selective media. Single clones were picked and grown in liquid media. DNA was extracted and confirmed by sequencing analysis.

To obtain protein for characterization by mass spectrometry, cells were grown in 100-mL cultures with 0 mM or 1 mM theophylline for 7 h. Cultures were chilled on ice and pelleted at 2°C for 10 min at 12,800g. When observed under a hand-held ultraviolet light, only the cells grown in the absence of theophylline were fluorescent. The cells grown without theophylline were suspended in lysis buffer and sonicated on ice. The histidine-tagged protein was purified using Ni2+-affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer's instructions (G-Biosciences). The elution fractions, which were fluorescent, were combined and concentrated with a Millipore Ultrafree 0.5 mL centrifugal filter device. The concentrated protein was run on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and the protein-containing band was cut from the gel and fully trypsinized as described (Shevchenko et al. 1996). The tryptic peptides were extracted and analyzed as previously reported (Peng and Gygi 2001) using an LTQ-Orbitrap ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA) at the Emory Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Proteomics Core. The results revealed that the N-terminal peptide was consistent with the expected sequence for the repressor (see Supplemental Material), indicating that the riboswitch is within the translated region.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplementary material can be found at http://www.rnajournal.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dongmei Cheng and Junmin Peng at the Emory Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Proteomics Core for their help in mass spectrometry analysis. This research was supported by the NIH (GM070740 to J.P.G.). J.P.G. is a Beckman Young Investigator, a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar, and an Alfred P. Sloan Fellow. S.T. is a G.W. Woodruff Fellow and an ARCS Scholar.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1269008.

REFERENCES

- Barrick J.E., Breaker R.R. The distributions, mechanisms, and structures of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R239. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer G., Suess B. Engineered riboswitches as novel tools in molecular biology. J. Biotechnol. 2006;124:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S.K., Gallivan J.P. Genetic screens and selections for small molecules based on a synthetic riboswitch that activates protein translation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13247–13254. doi: 10.1021/ja048634j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallivan J.P. Toward reprogramming bacteria with small molecules and RNA. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenison R.D., Gill S.C., Pardi A., Polisky B. High-resolution molecular discrimination by RNA. Science. 1994;263:1425–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7510417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A.L. The metabolism of methylpurines by Escherichia coli . J. Biol. Chem. 1956;219:181–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon D., Chalmers R.M., Kleckner N. Structural domains of IS10 transposase and reconstitution of transposition activity from proteolytic fragments lacking an interdomain linker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995;92:8234–8238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch S.A., Desai S.K., Sajja H.K., Gallivan J.P. A high-throughput screen for synthetic riboswitches reveals mechanistic insights into their function. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M., Breaker R.R. Adenine riboswitches and gene activation by disruption of a transcription terminator. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:29–35. doi: 10.1038/nsmb710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudler E., Mironov A.S. The riboswitch control of bacterial metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J.M., Gygi S.P. Proteomics: The move to mixtures. J. Mass Spectrom. 2001;36:1083–1091. doi: 10.1002/jms.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serganov A., Yuan Y.R., Pikovskaya O., Polonskaia A., Malinina L., Phan A.T., Hobartner C., Micura R., Breaker R.R., Patel D.J. Structural basis for discriminative regulation of gene expression by adenine- and guanine-sensing mRNAs. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:1729–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A., Wilm M., Vorm O., Mann M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins from silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukup G.A., Emilsson G.A., Breaker R.R. Altering molecular recognition of RNA aptamers by allosteric selection. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:623–632. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suess B. Engineered riboswitches control gene expression by small molecules. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33:474–476. doi: 10.1042/BST0330474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp S., Gallivan J.P. Guiding bacteria with small molecules and RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6807–6811. doi: 10.1021/ja0692480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp S., Gallivan J.P. Random walks to synthetic riboswitches—A high-throughput selection based on cell motility. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:210–213. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigand J.E., Sanchez M., Gunnesch E.B., Zeiher S., Schroeder R., Suess B. Screening for engineered neomycin riboswitches that control translation initiation. RNA. 2008;14:89–97. doi: 10.1261/rna.772408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werstuck G., Green M.R. Controlling gene expression in living cells through small molecule–RNA interactions. Science. 1998;282:296–298. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann G.R., Shields T.P., Jenison R.D., Wick C.L., Pardi A. A semiconserved residue inhibits complex formation by stabilizing interactions in the free state of a theophylline-binding RNA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9186–9192. doi: 10.1021/bi980082s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]