Abstract

Objectives To investigate trends in Russian mortality for 1991-2001 with particular reference to trends since the Russian economic crisis in 1998 and to geographical differences within Russia.

Design Analysis of data obtained from the Russian State statistics committee for 1991-2001. All cause mortality was compared between seven federal regions. Comparison of cause specific rates was conducted for young (15-34 years) and middle aged adults (35-69 years). The number of Russian adults who died before age 70 in the period 1992-2001 and whose deaths were attributable to increased mortality was calculated.

Main outcome measures Age, sex, and cause specific mortality standardised to the world population.

Results Mortality increased substantially after the economic crisis in 1998, with life expectancy falling to 58.9 years among men and 71.8 years among women by 2001. Most of these fluctuations were due to changes in mortality from vascular disease and violent deaths (mainly suicides, homicides, unintentional poisoning, and traffic incidents) among young and middle aged adults. Trends were similar in all parts of Russia. An extra 2.5-3 million Russian adults died in middle age in the period 1992-2001 than would have been expected based on 1991 mortality.

Conclusions Russian mortality was already high in 1991 and has increased further in the subsequent decade. Fluctuations in mortality seem to correlate strongly with underlying economic and societal factors. On an individual level, alcohol consumption is strongly implicated in being at least partially responsible for many of these trends.

Introduction

The huge fluctuations in Russian mortality during the 1990s have attracted much interest.1-3 Although Russian adult mortality was relatively high in 1991 compared with levels in western Europe, it increased rapidly in the immediate period after the break up of the Soviet Union, with a more marked increase among men. Subsequent to this, a sharp improvement was observed in the period 1995-8. Analyses of these trends identified vascular diseases and external causes as being responsible for most of the changes and focused on the role of alcohol and socioeconomic stress related to rapid economic changes.1-6 Individual level information on possible aetiological factors is, however, limited.

Russia experienced a further economic crisis in 1998, including rapid devaluation of its currency and increases in poverty. This economic crisis coincided with a further increase in adult mortality in the three years up to 2001, with life expectancy falling to 58.9 among men and 71.8 among women, levels similar to the low points reached in 1994. The cause of this recent dramatic decrease in life expectancy is not known. We examined the disease specific trends during this period to clarify these unique patterns.

Methods

We obtained data from the Russian State statistics committee, including deaths by cause, sex, five year age group, and calendar year together with corresponding population denominators. Causes of death in Russia were coded with the Soviet system of disease classification up to 1998, with each category corresponding to groups of items in ICD-9 (international classification of diseases, ninth revision).7 From 1999, a new system based on the 10th revision (ICD-10) was introduced.8 Table 1 shows the major groups of the Soviet and Russian classification systems and the corresponding ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes.

Table 1.

Causes of death used in analysis of change in mortality in Russia

| Cause | Russian classification 1988-98 | ICD-9 | Russian classification 1999-2001 | ICD-10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious and parasitic diseases: | 1-44 | 001-139 | 1-19,22-55 | A00-A32,A35-A99,B00-B99 |

| Tuberculosis | 9-13 | 010-018 | 9-15 | A15-A19 |

| Cancer: | 45-66 | 140-208 | 56-88 | C00-C97 |

| Lip, oral cavity, pharynx | 45 | 140-149 | 56 | C00-C14 |

| Oesophagus | 46 | 150 | 57 | C15 |

| Stomach | 47 | 151 | 58 | C16 |

| Colon | 49 | 153 | 60 | C18 |

| Rectum | 50 | 154 | 61 | C19-C21 |

| Larynx | 52 | 161 | 65 | C32 |

| Trachea, bronchus, lung | 53 | 162 | 66 | C33,C34 |

| Breast | 57 | 174 | 72 | C50 |

| Cervix | 58 | 180 | 73 | C53 |

| Prostate | 61 | 185 | 77 | C61 |

| Urinary tract | 63 | 188,189.0 | 79-81 | C64-C68 |

| Leukaemia | 65 | 204-208 | 87 | C91-C95 |

| Diseases of blood and blood forming organs | 71,72 | 280-289 | 90-92 | D50-D89 |

| Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic diseases: | 68-70 | 240-279 | 93-96 | E00-E90 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 68 | 250 | 93 | E10-E14 |

| Mental and behaviour disorders: | 73-77 | 290-319 | 97-103 | F01-F99 |

| Due to use of alcohol | 73,75 | 291,303 | 97,98 | F10 |

| Diseases of nervous system and sense organs | 78-83 | 320-389 | 104-111 | G00-G98 |

| Diseases of circulatory system: | 84-102 | 390-459 | 115-147 | I00-I99 |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 84,85 | 390-398 | 115,116 | I00-I02,I05-I09 |

| Hypertensive disease | 86-89 | 401-405 | 117-120 | I10-I13,I15 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 90-95 | 410-414 | 121-129 | I20-I23,I24.1-9,I25.1-9 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 98,99 | 430-438 | 133-141 | I60-I69 |

| Diseases of respiratory system: | 20,103-114 | 034,460-519 | 148-164 | J00-J99 |

| Acute respiratory infections | 103 | 460-466 | 148,155 | J00-J01,J02.8-9,J20-J22 |

| Pneumonia | 105-107 | 480-483,485,486 | 151-153,154 | J12-J16,J18 |

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 108-110 | 490-496 | 156-160 | J40-J47 |

| Lung diseases due to external agents | 111 | 500-508 | 161 | J60-J70 |

| Suppurative and necrotic conditions of lower respiratory tract | 112 | 510,513 | 163 | J85,J86 |

| Diseases of digestive system: | 115-127 | 520-579 | 165-179 | K00-K93 |

| Alcohol liver diseases | 122 | 571.0-571.3 | 173 | K70 |

| Non-alcoholic fibrosis and cirrhosis of liver | 123 | 571.5-571.6 | 174 | K74 |

| Gastric and duodenal ulcer | 115,116 | 531-533 | 165-167 | K25-K27 |

| Gastritis and duodenitis | 117 | 535 | 168 | K29 |

| Diseases of appendix | 118 | 540-543 | 169 | K35-K38 |

| Hernia | 119 | 550-553 | 170 | K40-K46 |

| Non-infective enteritis and colitis | 120 | 555-558 | 171 | K50-K52 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 121 | 560 | 172 | K56 |

| Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis | 124 | 574,575.0 | 176,177 | K80,K81 |

| Diseases of pancreas | 126 | 577 | 178 | K85,K86 |

| Diseases of urinary system: | 128-132 | 580-599 | 185-191 | N00-N39 |

| Urolithiasis | 131 | 592,594 | 190 | N20-N23 |

| Pregnancy, childbirth, puerperium | 135-141 | 630-676 | 21, 194-205 | A34,000-099 |

| Perinatal conditions | 151-157 | 764-779 | 206-216 | P05-P96 |

| Congenital anomalies | 145-150 | 740-759 | 217-225 | Q00-Q99 |

| Symptom, senility, ill defined, unknown cause | 158,159 | 780-799 | 226-228 | R00-R99 |

| All external causes: | 160-175 | E800-E999 | 239-255 | V01-Y89 |

| Transport incidents | 160,161,162 | E800-E807,E810-E848 | 239,240,241 | V01-V99 |

| Unintentional poisoning by alcohol | 163 | E860 | 247 | X45 |

| Other unintentional poisoning | 164 | E850-E858,E861-E869 | 248 | X40-X44,X46-X49 |

| Falls | 166 | E880-E888 | 242 | W00-W19 |

| Incidents caused by fire | 167 | E890-E899 | 246 | X00-X09 |

| Unintentional drowning | 168 | E910 | 243 | W65-W74 |

| Suicides | 173 | E950-E959 | 249 | X60-X84 |

| Homicides | 174 | E960-E969 | 250 | X85-V09 |

| Injury of undetermined intent | 175 | E980-E989 | 251 | Y10-Y34 |

We analysed trends of total and cause specific mortality for 1991-2001 for Russia overall and for seven federal regions, five in European Russia (North Western, Central, Privolzhski, Southern, and Uralski) and two in Asian Russia (Siberian and Far Eastern). We excluded data on Chechenskaya and Ingushskaya republics from the Southern region because of war. All death rates were standardised to the world standard population.9

Results

Mortality by age, sex, and cause

Age standardised mortality from all causes increased between 1998 and 2001 by 189/100 000 among men and 49/100 000 among women (table 2). Similar to the increase in mortality in 1991-4 and the decrease up to 1998, over 80% of the 1998-2001 increase was due to changes in those aged 35-69 years (middle age). However, an increase in mortality was also observed among younger adults, which is important given the lower underlying mortality. We therefore restricted analysis of these trends to young and middle aged adults.

Table 2.

Contribution of deaths at different ages to change of standardised mortality rate in Russia (per 100 000)

| Ages (years) | Mortality 1991 | Change (%) 1991-4 | Change (%) 1994-8 | Change (%) 1998-2001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||

| All ages | 1 184 | 459 (100) | −323 (100) | 189 (100) |

| 0-14 | 213.7 | 0.9 (0.2) | −2 (0.7) | −1 (−0.5) |

| 15-24 | 216.3 | 15 (3.2) | −2 (0.6) | 3 (1.6) |

| 25-34 | 316.1 | 35 (7.5) | −18 (5.6) | 16 (8.5) |

| 35-69 | 1 789 | 349 (75.9) | −237 (73.2) | 152 (80.4) |

| ≥70 | 10 430 | 60 (13.2) | −64 (19.9) | 18 (9.5) |

| Women | ||||

| All ages | 584.1 | 152 (100) | −98 (100) | 49 (100) |

| 0-14 | 146.8 | 3 (1.8) | −1 (1.0) | −1 (−2.2) |

| 15-24 | 69.9 | 4 (2.3) | −0.1 (0.1) | 1 (2.2) |

| 25-34 | 96.9 | 7 (4.8) | −2 (2.4) | 2 (4.4) |

| 35-69 | 674.9 | 97 (63.8) | −69 (70.0) | 40 (81.6) |

| ≥70 | 70 492 | 42 (27.3) | −26 (26.5) | 7 (14.2) |

All cause mortality in the 15-34 age group in 2001 was similar to that observed in 1994 among both men and women, with the modest improvements in the years up to 1998 having been completely reversed (table 3). Most of the increase in the mortality trends in the period 1998-2001 could be explained by trends in deaths from external causes, the most important being, in order of magnitude, an increase in suicide, traffic incidents, homicide, unintentional poisoning by alcohol, and falls. Other notable features include a modest increase in men and women of death from circulatory disease as well as an increase in infectious diseases, the latter representing a constant increase over the period 1991-2001 that was due almost entirely to tuberculosis. Finally, mortality from cancer changed little over the 10 year period.

Table 3.

Death rate by selected causes at age 35-69 years per 100 000 (standardised to world population)

|

Age 15-34 years

|

Age 35-69 years

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Men

|

Women

|

Men

|

Women

|

|||||||||||||

| Cause of death | 1991 | 1994 | 1998 | 2001 | 1991 | 1994 | 1998 | 2001 | 1991 | 1994 | 1998 | 2001 | 1991 | 1994 | 1998 | 2001 |

| All causes | 298 | 457 | 392 | 454 | 82.1 | 117 | 109 | 124 | 1789 | 2814 | 2117 | 2566 | 674 | 959 | 756 | 873 |

| Infectious diseases: | ||||||||||||||||

| All | 6.5 | 11.2 | 15.9 | 21.6 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 34 | 64.2 | 58 | 74.1 | 4.6 | 9 | 7.2 | 10.7 |

| Tuberculosis | 5.2 | 9.2 | 13.2 | 17.5 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 30.4 | 55.5 | 53.9 | 68 | 2.5 | 4.6 | 5 | 7.6 |

| All cancer | 12.7 | 13.3 | 12.6 | 11.6 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 11.9 | 11.6 | 447 | 455 | 403 | 384 | 194 | 201 | 189 | 187 |

| Circulatory system: | ||||||||||||||||

| All | 20.6 | 38.4 | 30.7 | 35.9 | 7 | 11 | 8.9 | 11.2 | 734 | 1180 | 905 | 1121 | 305 | 452 | 354 | 417 |

| Ischaemic disease | 8.9 | 16.9 | 10.6 | 11.9 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 433.2 | 688.9 | 508.6 | 616.3 | 128.4 | 202 | 148 | 176 |

| Cerebrovascular | 3.6 | 5.1 | 4.4 | 5.1 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 204 | 302.4 | 256.9 | 300.7 | 123.6 | 167 | 145.7 | 159.7 |

| Respiratory system: | ||||||||||||||||

| All | 4.2 | 9.4 | 8.0 | 11.3 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 102 | 193 | 118 | 155 | 23.1 | 34.4 | 22.4 | 26.7 |

| Pneumonia | 2.1 | 6.0 | 5.1 | 8.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 15.6 | 60.9 | 37.9 | 77.1 | 3.6 | 10.3 | 6.8 | 13.4 |

| Chronic diseases | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 60.2 | 88.6 | 59.1 | 63.8 | 14.5 | 17.2 | 11.7 | 10.8 |

| Digestive system: | ||||||||||||||||

| All | 4.6 | 9.9 | 7.8 | 11.7 | 1.8 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 4.3 | 60 | 106 | 84.1 | 107 | 24.8 | 43.6 | 33.3 | 46 |

| Alcohol liver disease | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 5.2 | 4.0 | 13.6 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 5.8 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 22.0 | 43.8 | 31.7 | 38.1 | 9.5 | 21.1 | 15.0 | 20.5 |

| External causes: | ||||||||||||||||

| All | 229 | 341 | 287 | 320 | 40 | 64.3 | 61.9 | 67.9 | 336 | 657 | 446 | 567 | 73.4 | 146 | 95.9 | 121 |

| Transport incidents | 63.5 | 59.1 | 46.5 | 52.7 | 11.6 | 13.7 | 13.6 | 15.1 | 60.6 | 55.1 | 41.1 | 52 | 14.4 | 13.1 | 11.4 | 14.1 |

| Alcohol poisoning | 8.8 | 25.8 | 12.5 | 17.4 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 39.1 | 123.5 | 57.6 | 90.2 | 9.1 | 33.8 | 14.7 | 24.2 |

| Other poisoning | 8.0 | 14.1 | 22.0 | 25.7 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 22.1 | 33.6 | 27.6 | 31.4 | 4.8 | 7.7 | 5.8 | 6.5 |

| Falls | 5.2 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 9.1 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 10.2 | 16.9 | 9.5 | 25.7 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 4.4 |

| Fire | 3.1 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 5.4 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 7.2 | 15.6 | 12.6 | 20.7 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 4.8 |

| Drowning | 16.9 | 23.0 | 21.4 | 22.4 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 18.1 | 27.5 | 23.1 | 27.1 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.7 |

| Suicide | 41.2 | 68.3 | 62.0 | 72.9 | 7.0 | 10.1 | 8.9 | 10.2 | 67.2 | 114.9 | 88.3 | 96.8 | 13.9 | 17.6 | 13.8 | 13.3 |

| Homicide | 33.3 | 60.0 | 41.4 | 46.6 | 6.7 | 12.5 | 11.0 | 13.0 | 31.5 | 72.9 | 48.8 | 66.6 | 9.3 | 20.9 | 13.4 | 17.6 |

| Other | 49 | 79.4 | 73 | 77.8 | 7.8 | 14.4 | 15.5 | 12.7 | 80 | 197 | 137.4 | 156.5 | 16 | 42.3 | 28.7 | 32.4 |

In middle aged adults (35-69 years) total mortality in 2001 was 21% higher for men and 15% higher for women than in 1998. The large increase between 1998 and 2001 seemed to be predominantly due to the same causes of death that were responsible for the previous increase between 1991 and 1994 and the subsequent decrease between 1994 and 1998—namely, diseases of the circulatory system and external causes. Of the former, the increase in mortality from cerebrovascular diseases during 1998-2001 was almost identical to the drop in mortality during 1994-8 among both men and women. The increase in mortality from ischaemic heart disease during 1998-2001 was also dramatic, although it was smaller than the 1994-8 decrease.

The primary causes of death from external causes among men aged 35-69 years in 2001 were, in order of magnitude, suicide, unintentional poisoning by alcohol, homicide, and transport incidents. All numbers of deaths from these causes increased substantially in the period 1998-2001, although were all slightly lower than the peak reached in 1994. The largest absolute increase was for unintentional poisoning by alcohol, which increased from 57.6/100 000 in 1998 to 90.2/100 000 in 2001. Among women, the primary causes of death from external causes were unintentional poisoning by alcohol and homicide, both of which increased in the period 1998-2001, although to a far lesser degree than among men.

In 1998-2001 mortality from diseases of the respiratory system also increased, mainly due to an increase in death from pneumonia. Mortality from digestive diseases, mostly alcohol induced liver disease and cirrhosis, and from infectious diseases, mostly tuberculosis, increased moderately.

The one disease category that did not follow these trends was cancers, with moderate decreases among men and a constant rate among women during 1998-2001, after more substantial decreases in 1994-8. These decreasing trends among men were largely explained by decreases in mortality from lung cancer and stomach cancer.

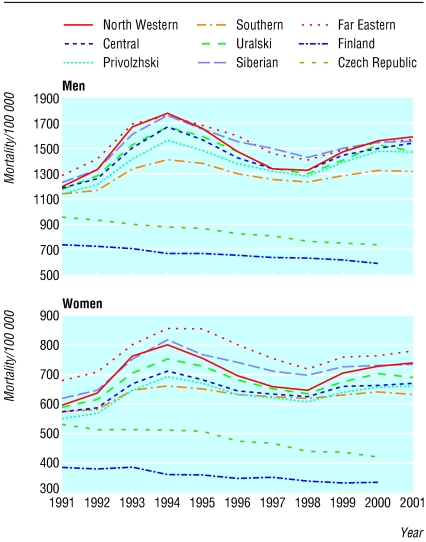

Mortality by region

When we compared all cause mortality between the seven different Russian regions, there were similar temporal trends (fig 1). High rates were consistently observed for the Siberian and Far Eastern regions, whereas the Southern region experienced a considerably lower rate. These temporal trends should be interpreted in the context of the health experience of countries in the same region, and we have included the mortality for Finland and the Czech Republic for comparative purposes (rates are not currently available for 2001 for either country). In 1991, mortality in Russian men was about 20% higher than in the Czech Republic, although mortality then decreased in the Czech Republic, resulting in an age standardised mortality in Russia in 2000 of 1484/100 000 that was 100% higher than that in the Czech Republic (733/100 000). The comparison with Finland, with which Russia shares a border, is also illustrative. Mortality also decreased in Finland over the period 1991-2001, although at a slower rate than in the Czech Republic, resulting in a lessening in the mortality gap between Finland and the Czech Republic and a large widening of the gap between Finland and Russia. In 2000, age standardised mortality in Russia was over twice as much as in Finland for men (1484 and 589/100 000 respectively) and women (678 and 333/100 000 respectively).

Fig 1.

Age standardised mortality from all causes by region

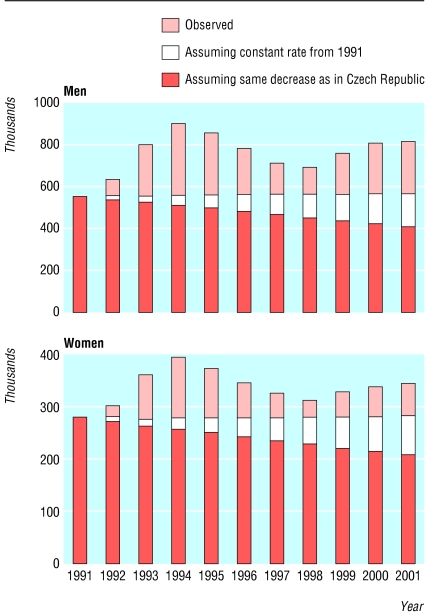

Finally, we calculated the numbers of extra premature adult deaths (that is, age 15-69 years) in the period 1992-2001 on the basis of two different scenarios: the number of premature adult deaths that would have occurred if mortality in 1992-2001 had stayed constant at the level of 1991, and if Russian mortality in the period 1992-2001 had decreased at a similar level to that seen in the Czech Republic, about 3% per year (fig 2). Of the 8 317 789 premature deaths in men and the 3 699 717 premature deaths in women that occurred among adults aged 15-69, about 2 142 000 in men and 625 000 in women would have been avoided if mortality had stayed constant at 1991 levels. Furthermore, an additional 864 000 premature deaths in men and 402 000 premature deaths in women would have been prevented if Russian mortality had decreased as it did in the Czech Republic.

Fig 2.

Observed and expected mortality in young and middle aged Russian adults 1991-2001. Data for men from 8 317 789 observed, 6 175 768 assuming constant rate from 1991, and 5 311 486 assuming same decrease as in Czech Republic. For women numbers were 3 699 717, 3 074 790, and 2 672 962

Discussion

The increase in Russian mortality in 1998-2001 followed a cause specific pattern similar to that seen in the earlier increase in 1991-4 and decrease in 1995-8, with external causes and circulatory disease explaining the large proportion of these trends. The increase in mortality was most apparent among young and middle aged men, and similar changes in mortality were observed in all parts of Russia. The increase in mortality over the period 1992-2001 is likely to have led to 2.5-3 million extra deaths in young and middle aged Russian adults.

The reasons behind the trends in mortality between 1991 and 1998 have been discussed previously in detail.1-6 In particular, the trends are unlikely to have been artefactual because of trends in data collection or underestimation of the Russian population,1,2 especially given the relatively constant mortality for all neoplasms combined. Furthermore, even though Russian mortality may have been overestimated in the past decade due to a large number of new non-resident immigrants who are not counted in population estimates,10 the strong consistency of these results across the Russian geographical regions would also argue strongly against an artefactual explanation due to population movement or misclassification.

The role of lifestyle factors

Attention has previously focused on the role of lifestyle factors associated with rapid economic change as possible causes of these mortality trends, in particular alcohol consumption and "socioeconomic stress" associated with having to survive in a challenging economic climate. The role of alcohol consumption in explaining a large part of the mortality trends would appear reasonable. The largest relative changes have been observed for those conditions that are directly related to alcohol—namely, unintentional poisoning by alcohol and liver cirrhosis. Poisoning by alcohol is likely to be a good measure of heavy (or binge) alcohol consumption in the population. Regarding liver cirrhosis, that short term trends can be influenced by recent changes in alcohol consumption may seem surprising given the chronic nature of the disease, although it is not without precedent. A similar phenomenon was reported in Paris during the German occupation of the second world war, when a shortage of alcohol in 1942 led to a large drop in mortality from liver cirrhosis in the following year.11

While changes in mortality from external causes were the main determinant for changes in overall mortality among young adults, trends in circulatory disease are primarily responsible for mortality trends in middle aged adults, in particular ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease. Regarding the latter, alcohol consumption strongly increases the risk of haemorrhagic stroke, although the association with ischaemic stroke is less clear.12 One might therefore predict that the overall trends are likely to be due to changes in haemorrhagic stroke. Regarding ischaemic heart disease, studies conducted among Western populations have consistently shown a protective effect for moderate alcohol consumption. However, in Russia heavy alcohol consumption and binge drinking are common, and the effects of binge drinking on lipids, coagulation and myocardial cells are probably different from the effects of regular drinking,13,14 resulting in an association between ischaemic heart disease and binge drinking that may be the inverse of the association with moderate alcohol consumption. Furthermore, there is evidence that heavy alcohol consumption can cause sudden death due to arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies.5 A possible association with binge drinking is also supported by an increase in cardiovascular mortality in Moscow during weekends,4 similar to findings from Scotland.15 The other disease categories that show substantial temporal variation include respiratory infections, in particular pneumonia, and also tuberculosis. Again, there is evidence for a link between alcohol consumption and mortality from these diseases,16 possibly acting through an immunosuppressive effect of heavy alcohol consumption.

Societal factors

Other proposed explanations for these rapid mortality changes include lifestyle and societal factors linked to general economic and political uncertainty.5 The rapid transition from a state controlled communist society to a capitalist society, which started in 1991 with rapid relaxation of economic controls, was combined with much political and societal uncertainty and resulted in devaluation of the currency, hyperinflation, increasing inequality, and removal of most forms of job protection. After some general improvement in the period 1994-8, a second economic crisis occurred in July-August 1998, which again resulted in further devaluation of the currency, an increase in inflation, and further political and economic uncertainty. Although the effect on mortality patterns seems to have been immediate, what remains to be identified is the exact role of rapid changes in alcohol consumption as opposed to other less clearly defined factors such as perceived lack of control over outside events, an increase in social stress, or a breakdown in trauma care.

What is already known on this topic

Adult mortality in Russia increased rapidly in the immediate period after the collapse of the former Soviet Union and fell rapidly in the period 1995-8

Vascular diseases and external causes were responsible for most of these changes, probably influenced by changes in alcohol consumption

Subsequent to the economic crisis in 1998, mortality increased again, with life expectancy falling to 58.9 among men and 71.8 among women by 2001

What this study adds

The increase in mortality in 1998-2001 followed a similar cause specific pattern to the increase in 1991-4

Trends were similar in all parts of the Russian Federation

An estimated extra 2.5-3 million Russian adults died in middle age in the period 1992-2001 than would have been expected based on 1991 mortality

Prospects

The changes in Russian mortality in the 1990s are unprecedented in a modern industrialised country in peacetime, and analysis of the cause of these changes is fundamentally important to understand the link between rapid economic change and health and also to help prevent similar future changes in Russia and other countries in transition. While analyses of mortality trends can highlight the problem, they cannot explain the reason, and large prospective epidemiological studies in Russian populations with individual level data are clearly required. With regard to future mortality trends in Russia, it is clear that a period of constant economic stability is required. One sign of optimism is that while mortality increased between 2000 and 2001, among young adults overall mortality decreased, indicating that the most recent part of this story may have turned another corner.

Contributors: TM, PBr, PBo, and DZ designed the study. TM collected the data and conducted the analysis. PBr wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and TM, PBo, and DZ contributed to all editions of the manuscript. Figures were produced by G Ferro and TM. DZ is guarantor.

Funding: TM was partially funded by the INCO-Copernicus-2 programme of the European Commission (contract number ICA2-CT2001-10002).

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Leon DA, Chenet L, Shkolnikov VM, Zakharov S, Shapiro J, Rakhmanova G, et al. Huge variations in Russian mortality rates 1984-94: artefact, alcohol, or what? Lancet 1997;350: 383-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shkolnikov V, McKee M, Leon DA. Changes in life expectancy in Russia in the mid-1990s. Lancet 2001;357: 917-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesle F. Mortality in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union: long term trends and recent upturns. Presented at IUSSP/MPIDR Workshop, June 19-21 2002. www.demogr.mpg.de/Papers/workshops/020619_paper27.pdf (accessed 23 July 2003).

- 4.Chenet L, McKee M, Leon D, Shkolnikov V, Vassin S. Alcohol and cardiovascular mortality in Moscow: new evidence of a causal association. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52: 772-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Britton A, McKee M. The relation between alcohol and cardiovascular disease in Eastern Europe: explaining the paradox. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54: 328-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walberg P, McKee M, Shkolnikov V, Chenet L, Leon D. Economic change, crime, and mortality crisis in Russia: regional analysis. BMJ 1998;317: 312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. International classification of diseases, 1975 revision (ICD-9). Geneva: World Health Organization, 1977.

- 8.World Health Organization. International classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision (ICD-10). Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992.

- 9.dos Santos Silva I. Cancer epidemiology: principles and methods. Lyons: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1999.

- 10.Zbarskaya I. Methodology of the census: traditions and innovations. Economica Rossyi: XXI Century 2002;9 (Oct): 12-20. (In Russian.) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fillmore KM, Roizen R, Farrell M, Kerr W, Lemmens P. Wartime Paris, cirrhosis mortality, and the ceteris paribus assumption. J Stud Alcohol 2002;63: 436-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzaglia G, Britton AR, Altmann DR, Chenet L. Exploring the relationship between alcohol consumption and non-fatal or fatal stroke: a systematic review. Addiction 2001;96: 1743-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKee M, Shkolnikov V, Leon DA. Alcohol is implicated in the fluctuations in cardiovascular disease in Russia since the 1980s. Ann Epidemiol 2001;11: 1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKee M, Britton A. The positive relationship between alcohol and heart disease in eastern Europe: potential physiological mechanisms. J R Soc Med 1998;91: 402-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans C, Chalmers J, Capewell S, Redpath A, Finlayson A, Boyd J, et al. "I don't like Mondays"—day of week of coronary heart disease deaths in Scotland: study of routinely collected data. BMJ 2000;320: 218-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doll R, Peto R, Hall E, Wheatley K, Gray R. Mortality in relation to consumption of alcohol: 13 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ 1994;309: 911-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]