Abstract

We review here four recent findings that have altered in a fundamental way our understanding of airways smooth muscle (ASM), its dynamic responses to physiological loading, and their dominant mechanical role in bronchospasm. These findings highlight ASM remodeling processes that are innately out-of-equilibrium and dynamic, and bring to the forefront a striking intersection between topics in condensed matter physics and ASM cytoskeletal biology. By doing so, they place in a new light the role of enhanced ASM mass in airway hyper-responsiveness as well as in the failure of a deep inspiration to relax the asthmatic airway. These findings have established that (i) ASM length is equilibrated dynamically, not statically; (ii) ASM dynamics closely resemble physical features exhibited by so-called soft glassy materials; (iii) static force-length relationships fail to describe dynamically contracted ASM states; (iv) stretch fluidizes the ASM cytoskeleton. Taken together, these observations suggest that at the origin of the bronchodilatory effect of a deep inspiration, and its failure in asthma, may lie glassy dynamics of the ASM cell.

1. INTRODUCTION

Asthma is characterized by airways that constrict too easily (airway hypersensitivity) and too much (airway hyperresponsiveness, AHR) (Woolcock et al. 1989). It is the excessive airway narrowing associated with AHR, rather than the hypersensitivity, that accounts for the morbidity and the mortality that is attributable to the disease (Macklem 1989; Sterk et al. 1989; McParland et al. 2003). AHR is thought to arise as a result of ongoing and irreversible remodeling of the airway wall (Pare et al. 1997; King et al. 1999b; Martin et al. 2000; Brusasco et al. 2003; McParland et al. 2003; Bai et al. 2004; Fredberg 2004). Among the various contributing factors that come into play in the remodeled airway (Woolcock et al. 1989), AHR might be accounted for either by increased mass of airway smooth muscle (ASM) or by decreased load against which the ASM must contract, but it is widely believed that increased ASM mass is the main culprit (Wiggs et al. 1992; Lambert et al. 1993; Macklem 1998).

Importantly, this conclusion has been based upon considerations that are mainly theoretical, deriving almost entirely from structural evidence that has been incorporated into detailed mathematical models describing the mechanics of airway narrowing (Wiggs et al. 1992; Lambert et al. 1993; Macklem 1996). We have recently come to learn, however, that phenomena accounting for AHR are mainly dynamic and are therefore unaccounted for by these previous theoretical analyses, which are entirely static. Moreover, these new results confirm the long-held conclusion that increased ASM mass is the functionally dominant derangement, but mechanisms accounting for this derangement differ dramatically from those previously presumed. Within such a dynamic framework, increased ASM mass not only explains AHR but also accounts for the failure of a deep inspiration (DI) to relax the asthmatic airway (Oliver et al. 2007), much as had been described long ago by Salter (Salter 1859). Indeed, new results imply that the failure of a DI to relax the asthmatic airway may be the proximal cause of AHR in asthma.

We begin this review by highlighting Salter’s early observations, and then go on to describe four iconoclastic findings that have changed in a fundamental way how we now think about airway smooth muscle and its role in bronchospasm.

1.1 HH Salter and the pivotal role of deep inspirations in asthma

In 1859, Henry H. Salter highlighted the existence of ASM and its importance in asthma (Salter 1859). He noted in particular that during a spontaneous asthma attack the asthmatic loses the ability to dilate the airways with a deep inspiration, almost as if the airways had narrowed and then become frozen in the narrowed state. He wrote,

“…the spasm may be broken through, and the respiration for the time rendered is perfectly free and easy, by taking a long, deep, full inspiration. In severe asthmatic breathing this can not be done; but in the slight bronchial spasm that characterizes hay asthma I have frequently witnessed it. It seems that the deep inspiration overcame and broke through the contracted state of the air tubes, which was not immediately re-established…”(Salter 1859)

It is now well established that of all known bronchodilatory agencies or drugs, the single most efficacious is a simple sigh or DI (Nadel et al. 1961; Green et al. 1974; Gump et al. 2001). During the spontaneous asthmatic attack – but not during induced obstruction in the laboratory – this most beneficial of all known bronchodilating agencies becomes ablated altogether (Fish et al. 1981; Lim et al. 1987; Ingram 1995; Skloot et al. 1995). It was suggested subsequently that the failure of this potent homeostatic phenomenon may be the proximal cause of the excess morbidity and mortality that is attributable to the disease (Nadel et al. 1961; Fish et al. 1981; Lim et al. 1987; Skloot et al. 1995; Moore et al. 1997; Fredberg 2000). This mystery then went on to attract the attention of an impressive pedigree of luminaries – Salter (1859), Nadel (1961) , Fish et al. (1981), Mead (Green et al. 1974), Macklem (Ding et al. 1987), Ingram (Lim et al. 1987), Permutt (Skloot et al. 1995), Paré (Moore et al. 1997), Brusasco(Crimi et al. 2002), Solway (Dowell et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2006) – but the mechanism has remained elusive.

2. FOUR ICONOCLASTIC DISCOVERIES

2.1 Muscle length is equilibrated dynamically, not statically

To explain acute airway narrowing and why it becomes excessive during asthma, the classical theory assumes static mechanical equilibrium: isometric active force generated by the ASM is balanced by the passive reaction force developed by the external load against which the muscle had shortened. According to this formulation, if the external load fluctuates with time, during lung inflation for example, the muscle would regulate its force at every instant as dictated by its static force-length characteristic. The key ideas here are force balance and its static nature: the smaller the elastic load, or the bigger the active isometric force, the smaller will be the caliber of the airway lumen at equilibrium, where the isometric force-generating capacity of ASM is set principally by muscle mass, muscle contractility, and muscle position on its static force-length characteristic (Lambert et al. 1973; Moreno et al. 1986; Wiggs et al. 1992; Macklem 1996; Thomson et al. 1996; Lambert et al. 1997).

These classical ideas predict the static equilibrium length toward which activated airway smooth muscle would tend if given enough time, but the biologically relevant prediction is quite different. In spontaneous normal breathing there is not nearly enough time for such an equilibration to occur, and the fluctuations associated with action of tidal breathing itself strongly perturbs the muscle (Fredberg et al. 1999a). We can put the potency of tidal fluctuations into perspective with the following observations. The expected physiologic range of tidal muscle stretch is from about 4% of muscle length during spontaneous breathing at rest to 12% during a sigh and greater still during exercise (Gump et al. 2001). In isolated activated muscle, however, tidal stretches of only 3% of muscle length are enough to inhibit active force generation by 50% (Fredberg et al. 1997). As such, isometric force generating capacity of airway smooth muscle fails to describe muscle forces in normal physiologic circumstances (Raboudi et al. 1998). The old view of homeostasis and equilibrium is now replaced by a dynamic world of fluctuation and nonequilibrium behavior.

The bronchodilating effect of spontaneous breathing is so effective that airway narrowing never approaches dangerous levels in healthy people, even when challenged with high concentrations of nonspecific bronchoconstricting agents. In healthy volunteers who inhale bronchoconstricting substances, such as histamine, there is a reflex increase in the frequency and depth of spontaneous sighs, and these fluctuations cause prompt and nearly complete dilation of the airway (Orehek et al. 1980; Lim et al. 1987; Lim et al. 1989). Even when healthy volunteers inhale some of the most potent known bronchoconstrictors, such as leukotrienes, bronchospasm is profoundly blunted unless deep inspirations are prohibited (Drazen et al. 1987). Taking into account the levels at which endogenous dilators are found in the airway, these observations suggest that the tidal muscle stretches that are attendant to spontaneous breathing comprise the first line of defense against bronchospasm, and that imposed tidal fluctuations of muscle length may be the most potent of all known bronchodilating agencies (Fredberg 1998; Fredberg et al. 1999b; Fredberg 2000; Fredberg 2004).

2.1.1 Freezing at static equilibrium

During an asthmatic attack, this potent bronchodilating mechanism fails. Indeed, there is ample evidence from the work of Ingram (Lim et al. 1987) to show that, if anything, deep inspirations during an asthmatic attack only serve to make matters worse. In this connection, experiments conducted years ago led Fish et al. (1981) to the striking observation that airway obstruction in asthma behaves as if it were caused by an intrinsic impairment of the bronchodilating effect of a deep inspiration, as opposed to an inappropriate end responsiveness of the airway itself. At about the same time, similar observations led Orehek et al. (1980) to speculate that asthma triggers a vicious cycle in which asthmatic airway obstruction increases the frequency of deep inspirations, and deep inspirations, in turn, make the obstruction worse.

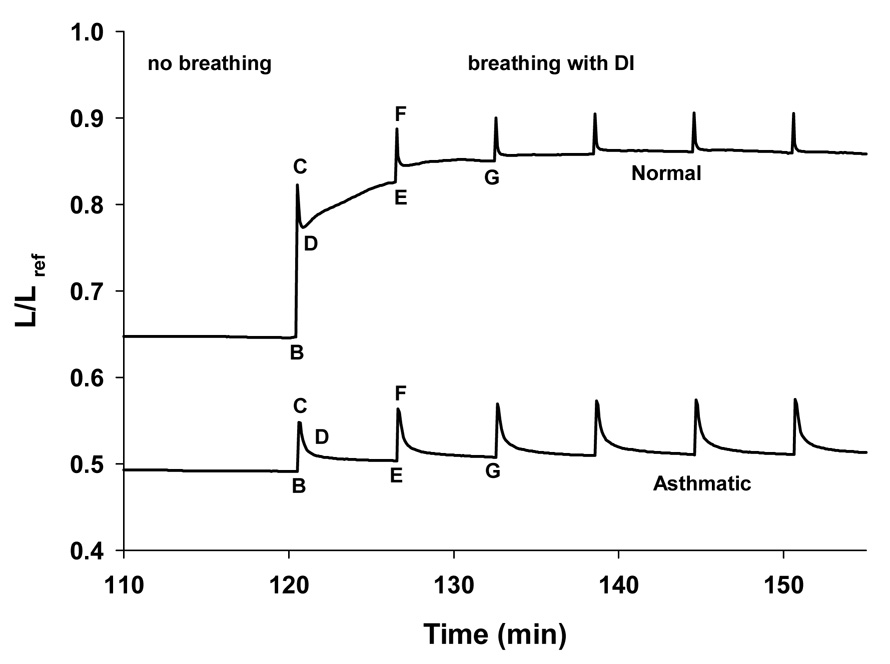

This impairment of the bronchodilating effect of a deep inspiration was long thought to be a characteristic of only spontaneous asthmatic obstruction and the late phase response to allergen challenge (Lim et al. 1987; Ingram 1995). Therefore it came as a surprise to learn only recently that an impairment of this kind is easily evoked in completely healthy individuals. Two laboratories have shown that if healthy, nonasthmatic, nonallergic subjects do nothing more than to voluntarily refrain from deep inspirations but otherwise maintain normal tidal volume, minute ventilation, and functional residual capacity, within 15 minutes their airways become hyperresponsive to a degree that is virtually indistinguishable from that observed in asthmatic subjects (Skloot et al. 1995; Moore et al. 1997; King et al. 1999a). Although in ordinary circumstances a normal individual subjected to bronchial provocation can reinstate a dilated airway with a single deep inspiration, if DIs are prohibited for 15 minutes and eventually reinstated, the subsequent ability of deep inspirations to dilate the airways becomes profoundly impaired, just as it does in spontaneous asthmatic obstruction. Put simply, it is as if the airway smooth muscle, when activated, is all the time flirting with disaster (Fredberg 1998), and the mere removal of deep inspirations, which would seem superficially to be a rather trivial matter, is sufficient nonetheless to precipitate a cascade of events that is much more serious. The airway smooth muscle can somehow become frozen into a stiff and shortened state, even in healthy volunteers with no airway inflammation, no history of airway inflammation or allergy, and airways and airway smooth muscle that are perfectly normal. This stiff and shortened state has been recently demonstrated experimentally in isolated ASM strips subjected to physiological loading conditions (Figure 1) (Oliver et al. 2007).

Figure 1.

Muscle length (averaged over the duration of one breath) vs. time: After two hours of static loading the muscle in the asthmatic airway had shortened much more than the muscle in the normal airway. Following breathing and deep inspiration, the normal and asthmatic airway behaved differently. The normal airway (top curve) dilated in response to a deep inspiration and remained dilated while the asthmatic airway (bottom curve) only dilated by a small amount and quickly returned to its static state. Adapted from Oliver et al. (2007).

Before muscle activation, hysteresis of the muscle is high while during constriction it decreases (Fredberg et al. 1996). Could this change in hysteresis relative to that of the parenchyma influence the dynamics and the final dynamic equilibrium to which the muscle converges? The simple answer is yes, as described long ago by Froeb and Mead (Froeb et al. 1968) as well as Lim et al. (1987). However, at the time of these studies it was not yet known that constricted isometric airway smooth muscle is a low hysteresis state (Fredberg et al. 1996), or that muscle stiffness and hysteresis respond dramatically to muscle stretch (Fredberg et al. 1999a).

2.1.2 Airway narrowing involves multiple scales of length

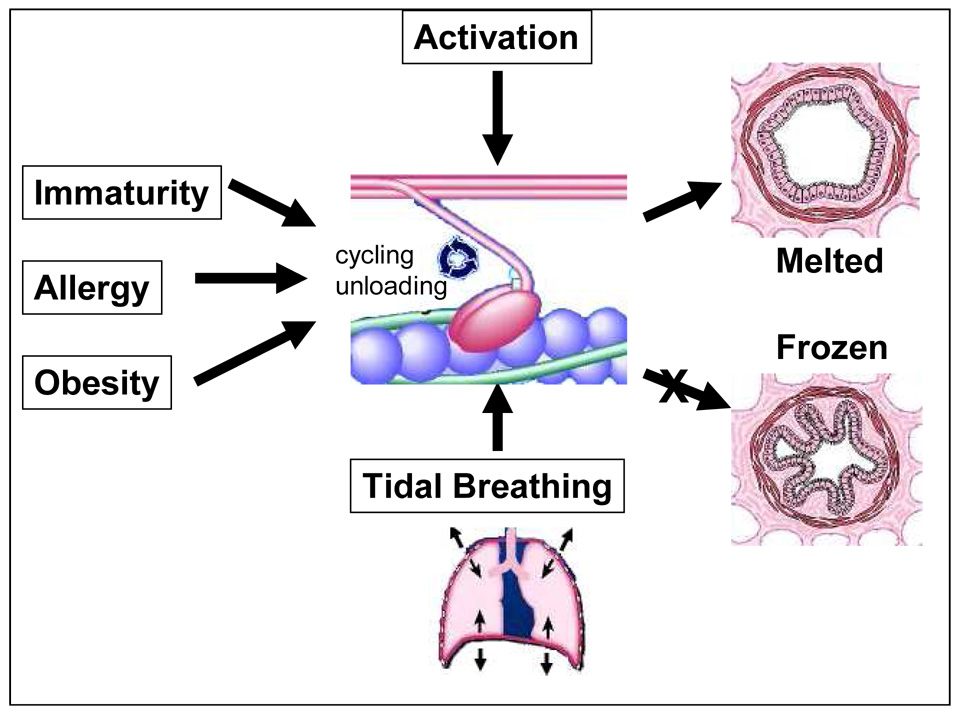

As described in greater detail below, airway narrowing in the healthy challenged lung is tightly integrated across scales, with actomyosin reaction kinetics and cytoskeletal plasticity and fluidization within the airway smooth muscle cell being coupled directly to organ-level events like tidal fluctuations in transpulmonary pressure. Accordingly, the system is controlled by kinetic parameters, which depend on rate processes and time, bridge-cycling rates, the frequency of breathing, and the time between sighs (Oliver et al. 2007), and not just static parameters, where rates and time can never be factors. Pathobiology (i.e., collapse to static equilibrium conditions and excessive airway narrowing) would then be seen to be a consequence of the failure of that coupling. In that case the muscle would shorten to a length dictated by static equilibrium conditions and remain frozen there largely independent of respiratory events transpiring at the organ level (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Factors affecting acute airway narrowing: The cyclic interaction of myosin with actin is activated by intracellular calcium but is modulated by factors that regulate myosin cycling (including allergy and immaturity) and myosin loading (airway remodeling and obesity). In normal circumstances the effects of tidal breathing are sufficient to perturb myosin binding and maintain maximally activated muscle in the melted state. In that case acute airway narrowing is limited, and airway caliber is controlled by a dynamically equilibrated nonequilibrium process. However, any number of factors can destabilize the system, block the melted pathway, and cause the system to collapse to a static binding equilibrium, in which case the airway smooth muscle will shorten and freeze. In that case airway smooth muscle has sufficient force-generating capacity to close every airway in the lung and will become refractory to the beneficial effects of deep inspirations. Adapted from Fredberg (2000).

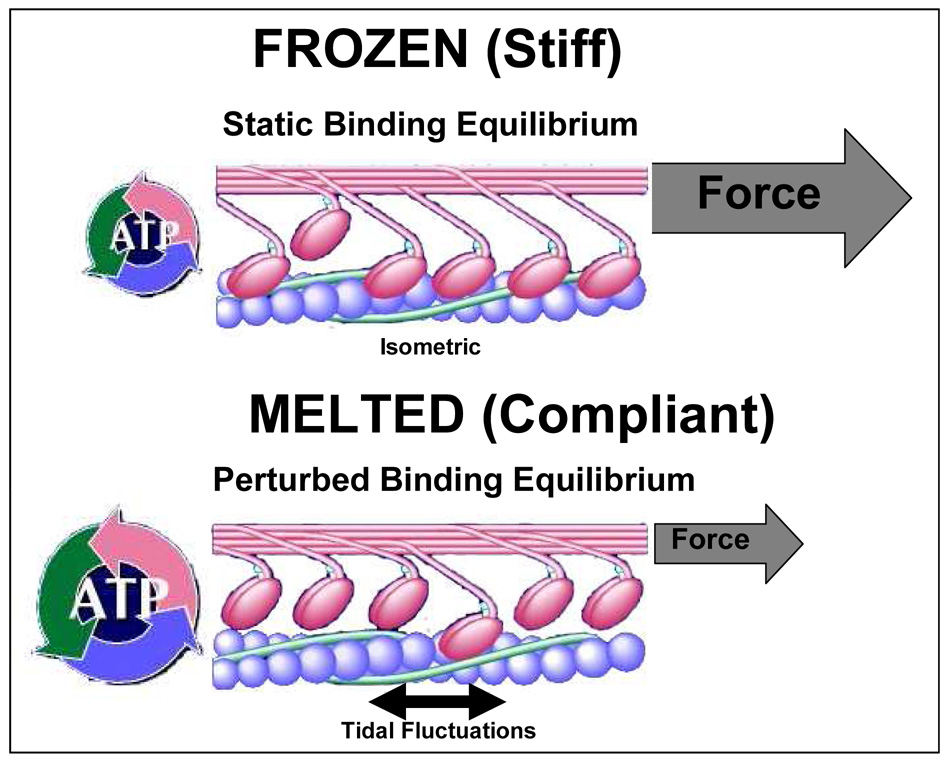

2.1.3 Myosin binding: perturbed equilibria or frozen in latch?

The theory of perturbed equilibria of myosin binding (Fredberg et al. 1999a; Mijailovich et al. 2000) holds that with each breath, lung inflation strains airway smooth muscle. These periodic mechanical strain fluctuations are transmitted to the myosin head and cause it to detach from the actin filament much sooner than it otherwise would have in isometric circumstances. This premature detachment profoundly reduces the duty cycle of myosin, typically by as much as 50% to 80% of its isometric (i.e., unperturbed) steady state value and depresses total number of bridges attached and active force by a similar extent. Therefore, of the full isometric force-generating capacity of the muscle, only a small fraction ever comes to bear on the airway during tidal breathing even when the muscle is activated maximally. As a result, the muscle can stay compliant and long even when the level of muscle stimulation is supramaximal. In the steady state the process becomes dynamically equilibrated, and only a small fraction of the bridges that can attach are attached. This is a hot molecular state characterized by small muscle stiffness, rapid bridge cycling, and a relatively high rate of specific ATP metabolism (Fredberg et al. 1999a). When this hot molecular state prevails, the physiologic expectation would be one of lower muscle forces, limited airway narrowing, the ability of deep inspirations to stretch the muscle, and a corresponding transient dilatory response to a deep inspiration (caused both by the breaking myosin links and the high hysteresis of muscle in the melted state relative to that of the lung parenchyma) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Frozen in latch versus Perturbed Equilibrium of Myosin binding: Top. During isometric steady-state contraction, myosin comes to a binding equilibrium corresponding to static equilibrium. The duty cycle of the myosin cross-links is high and a large fraction of the links is attached. This state is called the latch state. In this state, the muscle approximates a frozen state and is characterized by high muscle stiffness and low cycling rate of attached links. Bottom. During tidal fluctuations induced while breathing, the binding between myosin and actin is perturbed. As a result, only a small fraction of links that can attach to actin are attached. The perturbed state is characterized by compliant muscle that cycle very rapidly. This state is also referred to as the melted state. Adapted from Fredberg (2000).

As a result, the instantaneous ASM muscle force is not constrained to lie upon the classical static force–length curve or the classical Hill force–velocity curve (Gunst 1983; Fredberg et al. 1997; Anafi et al. 2001; Bates et al. 2005; Bates et al. 2007). Even when the mean muscle load is the same, differences in muscle response to static versus time varying loading conditions are rather dramatic (Oliver et al. 2007).

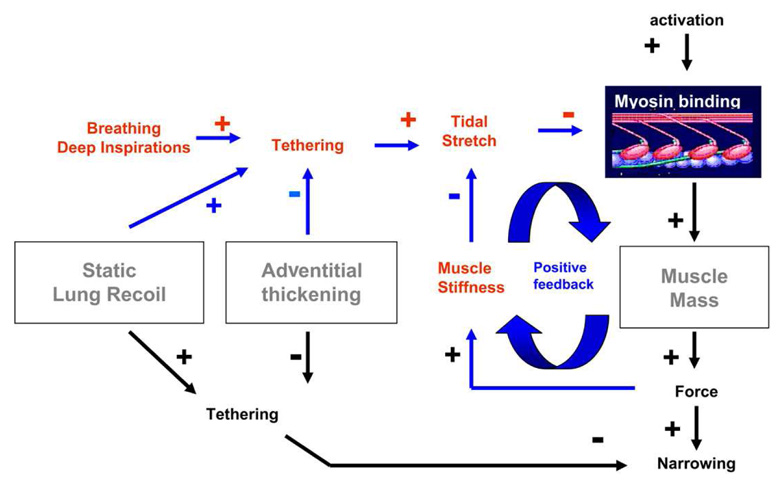

While this physical picture helped to explain why tidal breathing and deep inspirations are potent bronchodilators, it failed to explain why individuals with asthma are refractory to the beneficial effects of a DI. Finally, it was recognized that if muscle mass becomes too large or imposed force fluctuations become too small, then ASM stiffens and therefore stretches less, and because it stretches less it stiffens even more (Ding et al. 1987; Gunst et al. 1995; Fredberg et al. 1997; Fredberg et al. 1999a; Ma et al. 2002), and so on. This vicious positive feedback causes the system to collapse to a statically equilibrated state; the ASM virtually freezes in the latch state, and becomes so stiff that tidal breathing and DIs can no longer perturb myosin binding (Figure 4). As described below, we have recently come to learn that the contracted airway smooth muscle cell becomes refractory to a DI because its cytoskeleton becomes frozen in a stiff glassy phase that fails to fluidize.

Figure 4.

Role of deep inspirations (DIs) in normals versus asthmatics: In normal subjects, even during maximal muscle stimulation, tidal stretches and/or DIs act to perturb the binding of myosin to actin, and thus keep active force and muscle stiffness quite small. Small muscle stiffness, in turn, keeps the muscle highly responsive to tidal loading. However, with decreased static lung recoil, increased adventitial thickening, or, especially, increased muscle mass, the myosin binding is perturbed less, the muscle becomes stiffer as a result, and stretches even less, and so on. The feedback loop collapses and the muscle becomes so stiff as to be refractory to the effects of deep inspirations. “+” and “−”, respectively, indicate phenomena that act to increase or decrease the indicated effect. For example, adventitial thickening decreases tethering forces, and tethering forces act to decrease the extent of airway narrowing. By decreasing tethering, therefore, adventitial thickening acts to exacerbate airway narrowing. Adapted from Oliver et al. (2007).

2.2 The cytoskeleton is glassy

Perturbed equilibria of myosin binding explain a wide range of the ASM phenomenology but it is now seen to be only one part of a bigger picture. This can be readily understood from the inspection of the ASM rheology. If actomyosin dynamics alone were responsible for mechanics of the ASM cell, then the elastic modulus of the cell would exhibit characteristic relaxation times corresponding to the specific attachment/detachment rates of myosin cross-bridges. Despite large experimental efforts, this relaxation time has never been observed in ASM cells or tissues. Instead, the elastic modulus of the ASM cell follows a power-law over about 5 frequency decades (Fabry et al. 2001; Fabry et al. 2003b; Puig-De-Morales et al. 2004; Laudadio et al. 2005). This finding implies that the rates of relaxation processes in the cell are broadly distributed and cannot be associated solely with cross-bridge dynamics. Such a point of view constitutes a radical departure from the classical theory. How can we then understand the mechanics of the ASM cell?

A first clue was provided by Fabry et al. (2001) when they recognized that the behavior of the ASM cell resembles that of a broad class of substances called Soft Glassy Materials (SGMs) (Sollich et al. 1997; Sollich 1998; Fabry et al. 2001). This class of materials includes colloidal suspensions, pastes (toothpaste), foams (shaving foam), and slurries (ketchup). Although their composition is very different, their mechanics is remarkably alike and quite strange. Three common empirical criteria define the class of SGMs. The first of these is that they are soft; their Young's modulus is on the order of 1Pa to 1kPa, i.e., smaller than that of the softest of man-made polymers or rubbers by several orders of magnitude. The second criterion that defines SGMs is that their dynamics is ‘scale-free’, meaning that when matrix stiffness is measured over a wide range of frequencies, no special frequency, molecular relaxation time, or resonant frequency stands out (Sollich 1998). Instead, the stiffness increases with frequency in a featureless fashion following a weak power law with molecular relaxation processes in the matrix not tied to any particular internal time scale or any distinct molecular rate process. The third criterion that defines the class of soft glassy materials is that the dominant frictional stress seems not to be of a viscous origin or attributable to a viscous-like stress (Fredberg et al. 1989; Sollich 1998). Instead, the frictional stress in these materials is found to be proportional to the elastic stress, with the constant of proportionality, the hysteresivity η, being of the order 0.1. That is to say, frictional stress within the matrix is typically smaller than elastic stress, and when these stresses change they always do so in concert. Thus, like elastic stresses, frictional stresses are found to be scale-free and to increase with frequency with the same weak power law. We point out here that while scale-free dynamics and a low hysteresivity are characteristic of soft glassy materials, not all materials expressing these features are necessarily glassy, such as lung tissue, plastics, wood, concrete or some metals for example (Findley et al. 1989). Other hallmarks of glassy materials include physical aging, shear rejuvenation, kinetic arrest and intermittency, all of which have been found in SGMs as discussed below.

Glass can be highly malleable or not malleable at all. To fashion a work of glass, a glassblower must heat the object, shape it, and then cool it down. Our laboratory has suggested the hypothesis that the ASM cell modulates its mechanical properties and remodels its internal cytoskeletal structures in much the same way (Fabry et al. 2003a; Gunst et al. 2003; Bursac et al. 2005; Lenormand et al. 2006), and this hypothesis has provoked from other laboratories exciting new data and new theories of cytoskeletal dynamics (Kroy 2007; Semmrich et al. 2007). To the extent that the ASM cell is a glass, it should be malleable and thereby be able to adapt. As described below, the ability of the ASM to adapt is most remarkable.

2.3 Optimal muscle length is a myth

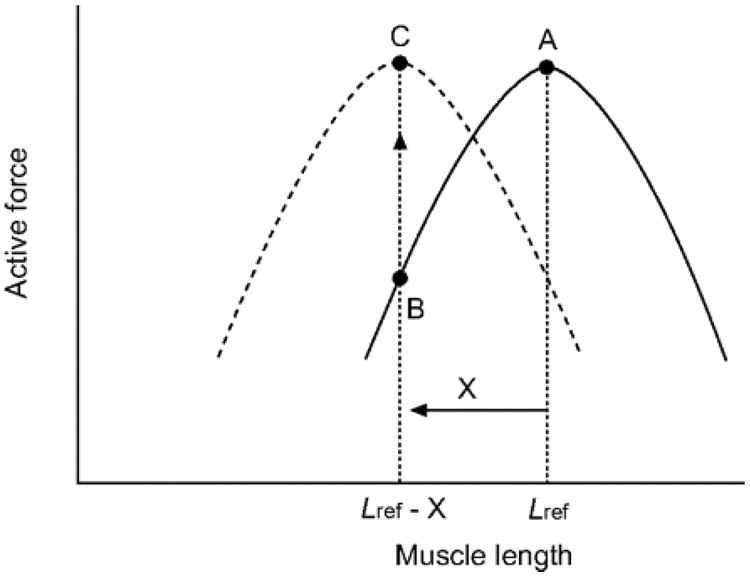

We have come to learn that ASM can adapt its static force–length curve rather dramatically, and can do so on time scales as short as hours, minutes, or even seconds (Gunst 1986; Gunst et al. 2000; Herrera et al. 2004). The mechanisms of cytoskeletal remodeling that account for that adaptation are not well understood and are the subject of much current attention (Gunst 1986; Wang et al. 2001). It is clear, however, that the classical force–length curve and its associated optimal length, if they exist at all, are not particularly relevant to the question of airway narrowing in asthma. Rather, through the actions of cytoskeletal remodeling the airway smooth muscle cell has the capacity to generate the same high static force over a huge range of muscle lengths, and for that reason the classical force–length curve, the optimal length, and the models that rest upon them engender errors that are not small. This phenomenon, whereby the length-force curve of a muscle shifts along the length axis (Figure 5) due to accommodation of the muscle at different lengths, is called length adaptation (Bai et al. 2004).

Figure 5.

Shift in the length–force relationship of airway smooth muscle due to length adaptation: The solid curve (—) represents the length–force relationship of a muscle adapted at an arbitrarily chosen reference length (Lref). Upon shortening by an amount (X), the actively developed force decreases from A to B. After adaptation at the new length (Lref - X), usually through repeated activation and relaxation, the maximal active force for the muscle at the new length recovers to the level before the length change (C), and the muscle now possesses a new length–force relationship (---). Adapted from Wang et al. (2001).

Length adaptation is thought to result from a dynamic modulation of cytoskeletal filament organization, in which the cell structure adapts to changes in cell shape at different muscle lengths (Gunst 1986; Pratusevich et al. 1995; Wang et al. 2001; Silberstein et al. 2002; Kuo et al. 2003). Molecular events associated with ASM structural reorganization involves rearrangement of actin and myosin filaments, attachment of actin filaments to dense bodies and plaques, and polymerisation and depolymerisation of these filaments. This reorganization tends to maintain optimal contractile filament overlap and orientation at different cell lengths (Pratusevich et al. 1995; Seow 2005). Seow and colleagues (Seow 2005; Smolensky et al. 2005) have suggested that the architecture of the myosin fibers themselves may change, whereas Gunst et al. (1995) have argued that it is the connection of the actin filament to the focal adhesion plaque at the cell boundary that is influenced by loading history.

2.4. Stretch fluctuations fluidize the cytoskeleton

Perhaps the strangest mechanical property of SGMs is that in absence of an external perturbation they behave as soft solids, with a Young’s modulus in the range of Pa to kPa, but when they are subjected to shear of sufficient magnitude they become much more fluid-like (Sollich 1998; Cloitre et al. 2000; Weitz 2001; Viasnoff et al. 2003). When shear is stopped, SGMs undergo a journey back towards a more solid-like state. Shear fluidization of this kind can be easily illustrated by many mundane examples; we all know, for instance, that we need to squeeze a toothpaste tube to get solid-like toothpaste to flow onto our brush, or that we need to shake a ketchup bottle to get the solid-like ketchup to flow on our fries.

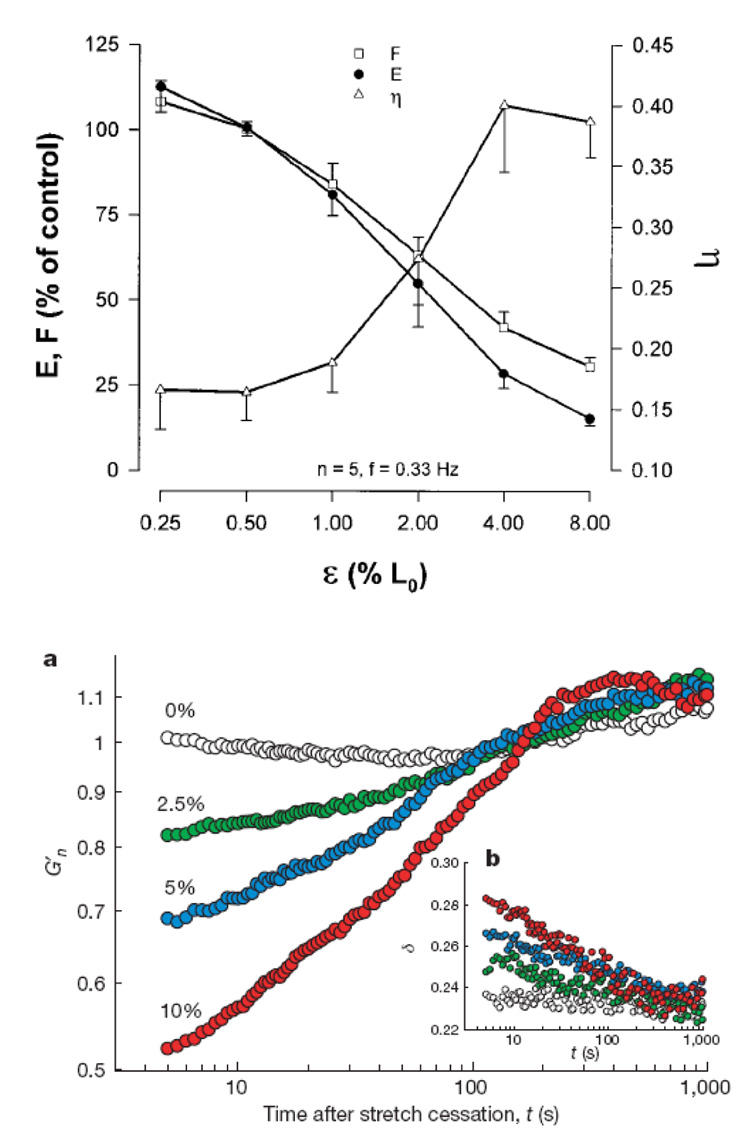

Remarkably similar behavior has been recently observed in the ASM cell (Bursac et al. 2005; Lenormand et al. 2007; Trepat et al. 2007). In the absence of stretch, the ASM cell is a solid but when it is subjected to a single transient stretch it acutely fluidizes (Figure 6). In addition, the rate of structural rearrangements of the cytoskeleton increases immediately after stretch by more than one order of magnitude (Trepat et al. 2007). When stretch is stopped, however, the cell resolidifies and the rate of structural rearrangements of the CSK relaxes. Stretch-induced fluidization has been now been observed at the molecular level (Bursac et al. 2005; Lenormand et al. 2007), the level of the single ASM cell (Trepat et al. 2007), and the level of the isolated ASM tissue (Fredberg et al. 1997). In addition, these dynamics resemble the change in airway resistance that occur in response to a deep inspiration at the patient level (Thorpe et al. 2004). Taken together, this evidence is suggestive that glassy dynamics of the ASM may be at the origin of the bronchodilatory effect of a deep inspiration and may offer us a clue as to why the asthmatic airway fails to fluidize. A key point here is that cells are fluidized by strain and not by stress. In other words, no matter how strong is the stress applied to the cell, it will not fluidize unless a given threshold of strain is achieved (Trepat et al. 2007). Therefore if the cell exists in a frozen state with high stiffness, as the asthmatic ASM cell is found to be, the stress that the lung parenchyma transmits to the ASM is most likely insufficient to cause a sufficient deformation to fluidize it. Of course, this problem is compounded even further by airway remodeling that tends to isolate the smooth muscle cell from fluctuations in parenchymal distending stress.

Figure 6.

Stretch induced ASM fluidization at various length scales: Top. Muscle force F, stiffness E and hysteresivity η as a function of the amplitude of tidal stretch ε, expressed as a percentage of muscle length. Increasing tidal stretch decreases the stiffness and increases η of ASM tissue. Adapted from Fredberg et al. (1997). Bottom. At the level of a single ASM cell, a single transient stretch decreases the functional stiffness (G’) and increases phase angle. Adapted from Trepat et al. (2007).

To say that cells are glassy, however, is an analogy not a mechanism. In fact the mechanism underlying glassy dynamics is one of the great unsolved problems in all science (Kennedy et al. 2005). The difficulty here is to establish a link between the macroscopic behavior of a material and that of its structural constituents. Physicists often approach this problem using the so-called trap models (Bouchaud 1992; Sollich et al. 1997; Sollich 1998; Ritort et al. 2003). In trap models, each structural element that constitutes the material is imagined to be trapped by its neighbors in energy wells. If the depth of these energy wells is large compared to thermal energy, structural rearrangements occur only very rarely and the system becomes trapped in long-lived metastable configurations. Slowly with time, however, the system visits configurations that are more and more stable, it becomes progressively stiffer and more solid-like, and the dynamics progressively slow. Slowly evolving dynamics of this kind is called physical aging, which is not to be confused with biological aging. When the system is sheared, however, the injection of mechanical energy causes structural elements to hop out of their energy wells, dynamics accelerate, stiffness drops and the material flows. In this way, material properties return to earlier values, aging is reversed and the system is said to be rejuvenated.

3. CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this review, we describe four iconoclastic discoveries that have substantially altered our understanding of airway smooth muscle, its role as the end-effecter of acute airway narrowing in bronchospasm and its striking yet strange dynamics. Moreover, a trail of recent evidence has led to an unexpected intersection between topics in condensed matter physics and ASM cytoskeletal biology. The interpretation of ASM mechanics in terms of generic trap models constitutes a shift in perspective and, as such, raises more questions than it answers. What are these abstract elements that become trapped in energy wells? What is the physical nature of such wells? Why is well depth so broadly distributed? What source of energy causes elements to hop out their wells? These questions are now the subject of a substantial effort at a multiscale level including the cross-linked polymer network (Balland et al. 2006; DiDonna et al. 2006; DiDonna et al. 2007), the single semiflexible filament (Rosenblatt et al. 2006), and the single macromolecule (Brujic et al. 2006). One appealing possibility is that the abstract elements imagined in trap models are in fact proteins that cross-link the actin cytoskeleton and that the localized inelastic rearrangements – or hopping events – that lead to glassy behavior are forced unfolding events of the protein domains. In this connection, recent theoretical studies have shown that cross-linked actin networks self-assemble into a fragile structure in which many domains exist in close proximity to an unfolding event (DiDonna et al. 2006; DiDonna et al. 2007). Such structure could be readily fluidized by injection of either chemical energy from ATP hydrolysis or mechanical energy from stretch. And at a deeper level of structure, increasing evidence suggests that even a single unfolding event of a protein domain can exhibit a broad distribution of rates, pushing the glassy paradigm into the realm of the single biological bond (Brujic et al. 2006).

What then is the role left to the myosin cross-bridge in this picture? Myosin, of course, remains the major force generator in the ASM cell but its action needs to be understood within a physical network that is disordered, fragile and out of thermodynamic equilibrium. The glassy dynamics of this network set the maypole around which myosin is constrained to dance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Anafi RC, Wilson TA. Airway stability and heterogeneity in the constricted lung. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1185–1192. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai TR, Bates JH, Brusasco V, Camoretti-Mercado B, Chitano P, Deng LH, Dowell M, Fabry B, Ford LE, Fredberg JJ, Gerthoffer WT, Gilbert SH, Gunst SJ, Hai CM, Halayko AJ, Hirst SJ, James AL, Janssen LJ, Jones KA, King GG, Lakser OJ, Lambert RK, Lauzon AM, Lutchen KR, Maksym GN, Meiss RA, Mijailovich SM, Mitchell HW, Mitchell RW, Mitzner W, Murphy TM, Pare PD, Schellenberg RR, Seow CY, Sieck GC, Smith PG, Smolensky AV, Solway J, Stephens NL, Stewart AG, Tang DD, Wang L. On the terminology for describing the length-force relationship and its changes in airway smooth muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:2029–2034. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00884.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balland M, Desprat N, Icard D, Fereol S, Asnacios A, Browaeys J, Henon S, Gallet F. Power laws in microrheology experiments in living cells: Comparative analaysis and modeling. Physical Review E. 2006;74:021911–021917. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.021911. 021911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JH, Lauzon AM. Modeling the oscillation dynamics of activated airway smooth muscle strips. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L849–L855. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00129.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JH, Mitzner W. Point: Counterpoint Lung Impedance Measurements Are / Are Not More Useful Than Simpler Measurements of Lung Function in Animal Models of Pulmonary Disease. J Appl Physiol. 2007 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00369.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchaud J. Weak ergodicity breaking and aging in disordered systems. J Phys I. 1992;2:1705–1713. [Google Scholar]

- Brujic J, Hermans R, Walther K, Fernandez JM. Single-molecule force spectroscopy reveals signatures of glassy dynamics of the energy landscape of ubiquitin. Nature Physics. 2006;2:282–286. [Google Scholar]

- Brusasco V, Pellegrino R. Complexity of factors modulating airway narrowing in vivo: relevance to assessment of airway hyperresponsiveness. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1305–1313. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00001.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursac P, Lenormand G, Fabry B, Oliver M, Weitz DA, Viasnoff V, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Cytoskeletal remodelling and slow dynamics in the living cell. Nat Mater. 2005;4:557–571. doi: 10.1038/nmat1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Liu G, Shardonofsky F, Dowell M, Lakser O, Mitchell RW, Fredberg JJ, Pinto LH, Solway J. Tidal breathing pattern differentially antagonizes bronchoconstriction in C57BL/6J vs. A/J mice. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:249–255. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01010.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Borrega R, Leibler L. Rheological aging and rejuvenation in microgel pastes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;85:4819–4822. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimi E, Pellegrino R, Milanese M, Brusasco V. Deep breaths, methacholine, and airway narrowing in healthy and mild asthmatic subjects. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1384–1390. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00209.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonna BA, Levine AJ. Filamin cross-linked semiflexible networks: fragility under strain. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97:068104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.068104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonna BA, Levine AJ. Unfolding cross-linkers as rheology regulators in F-actin networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2007;75:041909. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.041909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding DJ, Martin JG, Macklem PT. Effects of lung volume on maximal methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction in normal humans. J Appl Physiol. 1987;62:1324–1330. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.3.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell ML, Lakser OJ, Gerthoffer WT, Fredberg JJ, Stelmack GL, Halayko AJ, Solway J, Mitchell RW. Latrunculin B increases force fluctuation-induced relengthening of ACh-contracted, isotonically shortened canine tracheal smooth muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:489–497. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01378.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazen JM, Austen KF. Leukotrienes and airway responses. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:985–998. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.4.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabry B, Fredberg JJ. Remodeling of the airway smooth muscle cell: are we built of glass? Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003a;137:109–124. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabry B, Maksym GN, Butler JP, Glogauer M, Navajas D, Fredberg JJ. Scaling the microrheology of living cells. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;87:148102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.148102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabry B, Maksym GN, Butler JP, Glogauer M, Navajas D, Taback NA, Millet EJ, Fredberg JJ. Time scale and other invariants of integrative mechanical behavior in living cells. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2003b;68:041914. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.041914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley WN, Lai JS, Onaran K. Creep and Relaxation of Nonlinear Viscoelastic Materials with an Introduction to Linear Viscoelasticity. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fish JE, Ankin MG, Kelly JF, Peterman VI. Regulation of bronchomotor tone by lung inflation in asthmatic and nonasthmatic subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1981;50:1079–1086. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.50.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredberg JJ. Airway smooth muscle in asthma: flirting with disaster. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:1252–1256. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12061252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredberg JJ. Frozen objects: small airways, big breaths, and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:615–624. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.109429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredberg JJ. Bronchospasm and its biophysical basis in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res. 2004;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredberg JJ, Inouye D, Miller B, Nathan M, Jafari S, Raboudi SH, Butler JP, Shore SA. Airway smooth muscle, tidal stretches, and dynamically determined contractile states. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1752–1759. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.6.9611016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredberg JJ, Inouye DS, Mijailovich SM, Butler JP. Perturbed equilibrium of myosin binding in airway smooth muscle and its implications in bronchospasm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999a;159:959–967. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9804060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredberg JJ, Jones KA, Nathan M, Raboudi S, Prakash YS, Shore SA, Butler JP, Sieck GC. Friction in airway smooth muscle: mechanism, latch, and implications in asthma. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:2703–2712. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.6.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredberg JJ, Shore SA. The unbearable lightness of breathing. J Appl Physiol. 1999b;86:3–4. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredberg JJ, Stamenovic D. On the imperfect elasticity of lung tissue. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67:2408–2419. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.6.2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froeb HF, Mead J. Relative hysteresis of the dead space and lung in vivo. J Appl Physiol. 1968;25:244–248. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.25.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M, Mead J. Time dependence of flow-volume curves. J Appl Physiol. 1974;37:793–797. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.6.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gump A, Haughney L, Fredberg J. Relaxation of activated airway smooth muscle: relative potency of isoproterenol vs. tidal stretch. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2306–2310. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunst SJ. Contractile force of canine airway smooth muscle during cyclical length changes. J Appl Physiol. 1983;55:759–769. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunst SJ. Effect of length history on contractile behavior of canine tracheal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:C146–C154. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.250.1.C146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunst SJ, Fredberg JJ. The first three minutes: smooth muscle contraction, cytoskeletal events, and soft glasses. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:413–425. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00277.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunst SJ, Meiss RA, Wu MF, Rowe M. Mechanisms for the mechanical plasticity of tracheal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C1267–C1276. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.5.C1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunst SJ, Tang DD. The contractile apparatus and mechanical properties of airway smooth muscle. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:600–616. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15.29.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera AM, Martinez EC, Seow CY. Electron microscopic study of actin polymerization in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L1161–L1168. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00298.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RH., Jr Relationships among airway-parenchymal interactions, lung responsiveness, and inflammation in asthma. Giles F. Filley Lecture. Chest. 1995;107:148S–152S. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.3_supplement.148s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy D, Norman C. What we don't know? Science. 2005;309:82–83. doi: 10.1126/science.309.5731.75. 75–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King GG, Moore BJ, Seow CY, Pare PD. Time course of increased airway narrowing caused by inhibition of deep inspiration during methacholine challenge. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999a;160:454–457. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.9804012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King GG, Pare PD, Seow CY. The mechanics of exaggerated airway narrowing in asthma: the role of smooth muscle. Respir Physiol. 1999b;118:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroy KGJ. The glassy wormlike chain. New J. Phys. 2007;9:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo KH, Herrera AM, Wang L, Pare PD, Ford LE, Stephens NL, Seow CY. Structure-function correlation in airway smooth muscle adapted to different lengths. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C384–C390. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00095.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert RK, Pare PD. Lung parenchymal shear modulus, airway wall remodeling, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:140–147. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert RK, Wiggs BR, Kuwano K, Hogg JC, Pare PD. Functional significance of increased airway smooth muscle in asthma and COPD. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:2771–2781. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.6.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert RK, Wilson TA. A model for the elastic properties of the lung and their effect of expiratory flow. J Appl Physiol. 1973;34:34–48. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1973.34.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudadio RE, Millet EJ, Fabry B, An SS, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Rat airway smooth muscle cell during actin modulation: rheology and glassy dynamics. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1388–C1395. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00060.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenormand G, Bursac P, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Out-of-equilibrium dynamics in the cytoskeleton of the living cell. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2007;76:041901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.041901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenormand G, Fredberg J. Deformability, dynamics, and remodeling of cytoskeleton of the adherent living cell. Biorheology. 2006;43:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim TK, Ang SM, Rossing TH, Ingenito EP, Ingram RH., Jr The effects of deep inhalation on maximal expiratory flow during intensive treatment of spontaneous asthmatic episodes. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:340–343. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim TK, Pride NB, Ingram RH., Jr Effects of volume history during spontaneous and acutely induced air-flow obstruction in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:591–596. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Cheng Z, Kong H, Wang Y, Unruh H, Stephens NL, Laviolette M. Changes in biophysical and biochemical properties of single bronchial smooth muscle cells from asthmatic subjects. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L1181–L1189. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00389.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklem PT. Mechanical factors determining maximum bronchoconstriction. Eur Respir J. 1989 Suppl 6:516s–519s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklem PT. A theoretical analysis of the effect of airway smooth muscle load on airway narrowing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:83–89. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.1.8542167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklem PT. The mechanics of breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:S88–S94. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.nhlbi-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JG, Duguet A, Eidelman DH. The contribution of airway smooth muscle to airway narrowing and airway hyperresponsiveness in disease. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:349–354. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16b25.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McParland BE, Macklem PT, Pare PD. Airway wall remodeling: friend or foe? J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:426–434. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00159.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mijailovich SM, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Perturbed equilibria of myosin binding in airway smooth muscle: bond-length distributions, mechanics, and ATP metabolism. Biophys J. 2000;79:2667–2681. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76505-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BJ, Verburgt LM, King GG, Pare PD. The effect of deep inspiration on methacholine dose-response curves in normal subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1278–1281. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.4.96-11082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno RH, Hogg JC, Pare PD. Mechanics of airway narrowing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;133:1171–1180. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.6.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel JA, Tierney DF. Effect of a previous deep inspiration on airway resistance in man. J Appl Physiol. 1961;16:717–719. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1961.16.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MN, Fabry B, Marinkovic A, Mijailovich SM, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Airway Hyperresponsiveness, Remodeling, and Smooth Muscle Mass: Right Answer, Wrong Reason? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0418OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orehek J, Charpin D, Velardocchio JM, Grimaud C. Bronchomotor effect of bronchoconstriction-induced deep inspirations in asthmatics. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121:297–305. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare PD, Roberts CR, Bai TR, Wiggs BJ. The functional consequences of airway remodeling in asthma. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 1997;52:589–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratusevich VR, Seow CY, Ford LE. Plasticity in canine airway smooth muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1995;105:73–94. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-De-Morales M, Millet E, Fabry B, Navajas D, Wang N, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Cytoskeletal mechanics in the adherent human airway smooth muscle cell: probe specificity and scaling of protein-protein dynamics. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00070.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raboudi SH, Miller B, Butler JP, Shore SA, Fredberg JJ. Dynamically determined contractile states of airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:S176–S178. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.supplement_2.13tac150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritort F, Sollich P. Glassy dynamics of kinetically constrained models. Advances in Physics. 2003;52:219–342. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt N, Alencar AM, Majumdar A, Suki B, Stamenovic D. Dynamics of prestressed semiflexible polymer chains as a model of cell rheology. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97:168101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.168101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter HH. On asthma: its pathology and treatment. New York: William Wood and Company; 1859. [Google Scholar]

- Semmrich C, Storz T, Glaser J, Merket R, Bausch AR, Kroy K. Glass Transition and Rheological Redundancy in F-Actin Solutions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20199–20203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705513104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seow CY. Myosin filament assembly in an ever-changing myofilament lattice of smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1363–C1368. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00329.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein J, Hai CM. Dynamics of length-force relations in airway smooth muscle. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2002;132:205–221. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(02)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skloot G, Permutt S, Togias A. Airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma: a problem of limited smooth muscle relaxation with inspiration. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2393–2403. doi: 10.1172/JCI118296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolensky AV, Ragozzino J, Gilbert SH, Seow CY, Ford LE. Length-dependent filament formation assessed from birefringence increases during activation of porcine tracheal muscle. J Physiol. 2005;563:517–527. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollich P. Rheological constitutive equation for a model of soft glassy materials. Physical Review E. 1998;58:738–759. [Google Scholar]

- Sollich P, Lequeux F, Hebraud P, Cates ME. Rheology of soft glassy mateirals. Physiol Rev Lett. 1997;78:2020–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sterk PJ, Bel EH. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness: the need for a distinction between hypersensitivity and excessive airway narrowing. Eur Respir J. 1989;2:267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson RJ, Bramley AM, Schellenberg RR. Airway muscle stereology: implications for increased shortening in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:749–757. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.3.8810615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe CW, Salome CM, Berend N, King GG. Modeling airway resistance dynamics after tidal and deep inspirations. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1643–1653. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01300.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepat X, Deng L, An S, Navajas D, Tschumperlin D, Gerthoffer W, Butler J, Fredberg J. Universal physical responses to stretch in the living cell. Nature. 2007;447:592–595. doi: 10.1038/nature05824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viasnoff V, Jurine S, Lequeux F. How are colloidal suspensions that age rejuvenated by strain application? Faraday Discuss. 2003;123:253–266. doi: 10.1039/b204377g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Pare PD, Seow CY. Selected contribution: effect of chronic passive length change on airway smooth muscle length-tension relationship. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:734–740. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.2.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitz DA. Condensed matter. Memories of paste. Nature. 2001;410:32–33. doi: 10.1038/35065199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggs BR, Bosken C, Pare PD, James A, Hogg JC. A model of airway narrowing in asthma and in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1251–1258. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock AJ, Peat JK. Epidemiology of bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Clin Rev Allergy. 1989;7:245–256. doi: 10.1007/BF02914477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]