Abstract

Although factor VII/factor VIIa (FVII/FVIIa) is known to interact with many non-vascular cells, activated monocytes, and endothelial cells via its binding to tissue factor (TF), the interaction of FVII/FVIIa with unperturbed endothelium and the role of this interaction in clearing FVII/FVIIa from the circulation are unknown. To investigate this, in the present study we examined the binding of radiolabeled FVIIa to endothelial cells and its subsequent internalization. 125I-FVIIa bound to non-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) in time-and dose-dependent manner. The binding is specific and independent of TF and negatively charged phospholipids. Protein C and monoclonal antibodies to endothelial cell protein C receptor (EPCR) blocked effectively 125I-FVIIa binding to HUVEC. FVIIa binding to EPCR is confirmed by demonstrating a marked increase in 125I-FVIIa binding to CHO cells that had been stably transfected with EPCR compared with the wild-type. Binding analysis revealed that FVII, FVIIa, protein C, and activated protein C (APC) bound to EPCR with similar affinity. FVIIa binding to EPCR failed to accelerate FVIIa activation of factor X or protease-activated receptors. FVIIa binding to EPCR was shown to facilitate FVIIa endocytosis. Pharmacological concentrations of FVIIa were found to impair partly the EPCR-dependent protein C activation and APC-mediated cell signaling. Overall, the present data provide convincing evidence that EPCR serves as a cellular binding site for FVII/FVIIa. Further studies are needed to evaluate the pathophysiological consequences and relevance of FVIIa binding to EPCR.

Despite the progress that has been made in understanding the biochemistry and pathophysiology of the coagulation cascade events, the clearance mechanism of the various coagulation proteins from the circulation is still unclear. The marked differences in circulating half-lives of factor VII (FVII)4 and FVIIa compared with those of zymogen and the enzyme forms of other vitamin K-dependent coagulation proteins (1–7) suggest that there may be a specific and distinct clearance mechanism for FVII/FVIIa. Although tissue factor (TF), the cellular receptor for FVII/FVIIa, facilitates the endocytosis of FVII/FVIIa (8), its expression under normal conditions is strictly restricted to extravascular cells (9, 10). This raises the possibility that FVII/FVIIa interaction with vascular cells, independent of TF, may play a role in the clearance of these proteins. Our recent studies showed that hepatocytes support FVIIa endocytosis, but the rapid turnover of the plasma membrane rather than receptor-mediated endocytosis seemed to be responsible for the internalization of FVIIa in these cells (11).

The endothelium, which constitutes the interface between the circulating blood and the vascular tissue, is positioned optimally to play a role in the clearance of circulating clotting factors. There is not much information on FVIIa interaction with the endothelium in the literature. Twenty years ago, Rodgers et al. (12) showed that only nonvascular cells, which express TF, possessed receptors for FVIIa whereas cells derived from vascular tissue, such as aortic endothelial cells, had no specific FVIIa binding sites on their cell surface. However, Reuning et al. (13) found that FVIIa bound to non-stimulated endothelial cells (HUVEC) in a time- and dose-dependent manner. This report also indicated that the FVIIa binding site on non-stimulated HUVEC appeared to be a common binding site for vitamin K-dependent proteins because prothrombin and other vitamin K-dependent proteins reduced FVIIa binding to endothelial cells. The identity of the binding site and its potential role in FVIIa clearance are unknown.

In the present study, we investigated the binding of FVIIa to non-stimulated HUVEC and found that FVIIa binds to EPCR in a true ligand fashion. FVII and FVIIa bound to EPCR with a similar affinity to that of protein C and APC, known ligands for EPCR. Unlike TF-FVIIa, EPCR-FVIIa complexes exhibited no protease activity toward the FVIIa substrates. FVIIa binding to EPCR was shown to facilitate the internalization of FVIIa.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

NovoSeven® (Novo Nordisk, Denmark) was used as a source of recombinant human factor VIIa (rFVIIa). Gla-domain less des-FVIIa (14) and asialo FVIIa (11) were prepared as described earlier. Purified human factor X, prothrombin, APC, and protein C were from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN) or Hematological Technologies Inc. (Essex Junction, VT). Recombinant APC (Xigris) was obtained from Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, IN). Zeocin was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). FuGENE HD transfection reagent was procured from Roche Diagnostics Corp. (Indianapolis, IN). Mouse monoclonal anti-EPCR antibody (JRK-1494) (15) and human EPCRS219 cDNA (pZeoSV-EPCR219) (16) were prepared as described earlier. Annexin V was kindly provided by Jonathan Tait (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). Monospecific, polyclonal anti-TF IgG was prepared as described previously (17).

Cell Culture

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from Cambrex Bio Science (Walkersville, MD). The cells were cultured to confluency at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator in EBM-2 basal media supplemented with growth supplements (Cambrex Bio Science) and 5% fetal bovine serum. Endothelial cell passages between 3 and 10 were used in the present studies. Wild type CHO-K1 cells were obtained from ATCC. These cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator in F12K media containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum. For transfection, CHO-K1 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate and at 50% confluence, the cells were transfected with 1 μg of human EPCRS219 cDNA (16) using FuGENE HD transfection reagent as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Stable transfectants were selected by maintaining the transfected cells (72 h post-transfection) in medium containing 500 μg/ml of Zeocin. After 2 weeks, the colonies were isolated, expanded, and screened for EPCR expression by FACS analysis.

Radiolabeling

FVIIa and other ligands were labeled with 125I using IODOGEN (Pierce)-coated polypropylene tubes and Na125I (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Wellesley, MA) according to the manufacturer’s technical bulletin and as described previously (18). In brief, ~100 μg of protein was incubated with Na125I (1 mCi) in a 10 μg of IODOGEN-coated tube on ice for 20–30 min, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 1% potassium iodide. The reaction mixture was then dialyzed for 18–20 h in HEPES buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) at 4 °C with 3 changes (2 liters each time) to remove the free iodide. The specific activities of the labeled samples were varied from 1–3 ×109 cpm/mg. The radiolabeled proteins were intact with no apparent degradation and retained 80% or more of the functional activity of unlabeled proteins (18, 19).

Determination of Surface Binding, Internalization, and Degradation

Near confluent monolayers of HUVEC, EPCR-transfected (CHO/EPCR+), or wild type CHO-K1 cells were washed once with buffer A (10 mM HEPES, 0.15 M NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 11 mM glucose, pH 7.5) containing 5 mM EDTA and then once with buffer B (buffer A with 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin and 5 mM CaCl2). The cells were then incubated with buffer B and chilled on ice before radiolabeled 125I-FVIIa (10 nM) or other compounds were added. When cells were treated with anti-EPCR monoclonal antibody, anti-TF polyclonal IgG or annexin V, the monolayers were incubated with them for 30 min at room temperature before the radiolabeled ligand was added. For cold competition experiments, the competitor proteins, other than antibodies or annexin V, were added to the cells at the same time as the radiolabeled proteins. For binding studies, the cells were incubated with the radiolabeled ligand ± unlabeled competitors at 4 °C on ice for a fixed interval (3 h) or varying time periods (0–3 h) as designated, the supernatant was removed from the wells, and the cells were washed four times with ice-cold buffer B to remove the unbound radiolabeled protein. The surface-bound radiolabeled ligand was eluted by treating the cells with 0.1 M glycine (pH 2.3) for 5 min at room temperature. For internalization studies, the cells were incubated at 37 °C with radiolabeled ligand for different time intervals (0–3 h), and the bound material was eluted as described above, and then the cells were extracted with lysis buffer (0.1 M NaOH, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS). The surface-eluted and the cell-extracted radioactivity were counted in a γ-counter. To determine the extent of FVIIa degradation, cells were incubated with 125I-FVIIa (10 nM) in the presence or absence of EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml) and at varying times small aliquots were removed from the dish, and precipitated by adding an equal volume of ice-cold 10% trichloroacetic acid. The samples were subjected to centrifugation (15,000 × g for 10 min), and the supernatants were removed and counted for the radioactivity.

Factor Xa Generation on HUVEC Surface

Unperturbed or stimulated (with a combination of TNFα, 20 ng/ml and IL-1β, 20 ng/ml for 6 h in serum-free medium) confluent monolayers of HUVEC in a 96-well culture plate were incubated with FVIIa (10 nM) in buffer B for 5 min at 37 °C in presence or absence of anti-EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml), control mouse IgG (10 μg/ml) or anti-TF IgG (25 μg/ml). FX (175 nM) was then added to the cells (final reaction mixture volume, 100 μl) and incubated for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by adding buffer A containing 10 mM EDTA and the amount of FXa generated in the reaction period was measured by using the chromogenic substrate (Chromogenix S-2765), and monitoring the change in absorbance at 405 nm in a microplate reader for 2 min. The initial rate of color development was converted into FXa concentrations from a standard curve prepared with known dilutions of purified human FXa.

Activation of Protease-activated Receptors 1 and 2

CHO/EPCR+ were transfected transiently with AP-PAR1 or AP-PAR2 reporter constructs in which alkaline phosphatase (AP) was fused to the N terminus of PAR1 or PAR2 following the strategy described earlier for the construction of AP-PAR1 (20). In this assay, activation of AP-PAR1 or AP-PAR2 releases the N terminus peptide with the AP tag into the overlying conditioned medium, and thus the AP activity in the medium correlates with the PAR activation. The transfected cells were treated with FVIIa, APC, thrombin, or trypsin (10 nM). At the end of 1 h of treatment, 25 μl of overlying conditioned media were collected and centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 rpm in an Eppendorf table-top centrifuge to remove any cell debris. Alkaline phosphatase activity in 15 μl of supernatant medium was quantified using a chemiluminescence substrate from BD Bioscience Great EscAPe SEAP detection kit.

Protein C Activation

Confluent monolayers of CHO/EPCR+ in a 96-well plate were incubated with protein C (80 nM) and thrombin (2 nM) in the presence or the absence of various concentrations of FVIIa (0–100 nM) or anti-EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml) for 30 min. APC generated in the reaction mixture was measured by adding the chromogenic substrate, Spectrozyme PCa (2 mM) to the well (hirudin, 2 units/ml, was added to the well before the addition of the chromogenic substrate to inhibit the thrombin), and measuring the change in absorbance at 405 nm in a microplate reader.

RESULTS

Binding and Internalization of FVIIa in HUVEC

To evaluate the potential role of the endothelium in the clearance of FVII/FVIIa from the circulation, we investigated first whether FVIIa binds to native endothelium. Non-stimulated HUVEC were incubated with 10 nM of 125I-FVIIa for varying time periods at 4° and 37 °C, and the binding and internalization of FVIIa were measured as described in the methods. At 4 °C, the binding followed a hyperbolic pattern and reached near saturation at 3 h (23.5 ± 2.09 fmol 10−5 cells) (Fig. 1A). At 37 °C, the surface binding reached its maximum value within 30 min of the incubation with radiolabeled FVIIa. However, the amount of 125I-FVIIa associated with the cell surface at 37 °C (8.9 ± 3.21 fmol 10−5 cells) was about 3-fold lower than that was obtained at 4 °C, which suggests that FVIIa bound to HUVEC was endocytosed at 37 °C. Consistent with this, a significantly higher rate of internalization 125I-FVIIa was observed at 37 °C compared with 4 °C. (66.8 ± 8.2 versus 18.8 ± 4.24 fmol h−1 10−5 cells) (Fig. 1B). FVIIa binding to HUVEC is calcium dependent, as in the absence of calcium ions in the binding buffer very little 125I-FVIIa was associated with HUVEC (data not shown).

FIGURE 1. FVIIa binding and internalization in HUVEC at 4 and 37 °C.

Monolayers of confluent non-stimulated HUVEC (in a 24-well plate) were incubated with 125I-FVIIa (10 nM) for varying time periods (0 –180 min) at 4 °C (○) and at 37 °C (●). At the end of time period, the amount of 125I-FVIIa associated with the cell surface (A) and internalized (B) was determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (n = 3).

To determine the specificity of FVIIa binding to endothelial cells, the binding of 125I-FVIIa (10 nM) to unperturbed HUVEC was examined in the absence and the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled FVIIa, anti-TF IgG or annexin V. Unlabeled FVIIa reduced the binding of 125I-FVIIa to about 50% (p = 0.0085; n = 4 to 5) whereas anti-TF-IgG had no effect, ruling out the possibility that any traces of TF that might be present on non-stimulated HUVEC contributed to the FVIIa binding to HUVEC (Fig. 2A). Annexin V, which binds to negatively charged phospholipids and thus blocks the interaction of vitamin K-dependent clotting proteins with the anionic phospholipids, failed to attenuate the 125I-FVIIa binding to non-stimulated HUVEC. Next, we performed similar experiments with stimulated HUVEC. No significant differences were found in 125I-FVIIa binding between stimulated HUVEC and non-stimulated HUVEC. The total amount of 125I-FVIIa associated with stimulated HUVEC was only slightly (but not significantly) higher than that was observed with the non-stimulated HUVEC. As with non-stimulated cells, a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled FVIIa inhibited the 125I-FVIIa binding to stimulated HUVEC. Although, anti-TF IgG resulted in about 20% inhibition of 125I-FVIIa binding to stimulated endothelial cells, this reduction was not significant statistically (p = 0.11; n = 3). The inability of anti-TF IgG or annexin V to block the 125I-FVIIa binding to HUVEC suggest that FVIIa interacts with the endothelial cell surface independent of TF and negatively charged phospholipids. Further, even when HUVEC were stimulated to express optimal levels of TF, TF was not the most abundant binding site for FVIIa on the endothelium.

FIGURE 2. FVIIa binding specificity to HUVEC.

A, unperturbed HUVEC were incubated with 125I-FVIIa (10 nM) for 3 h at 4 °C in the presence or the absence of unlabeled FVIIa (1 μM), anti-human TF IgG (25 μg/ml), or annexin V (200 nM), and 125I-FVIIa bound to the cell surface was determined (mean ± S.E.; n = 4 –5). B, HUVEC were stimulated with 20 ng/ml of each of IL-1β and TNF-α for 6 h at 37 °C. The stimulated HUVEC were then incubated with 125I-FVIIa (10 nM) with or without unlabeled FVIIa, anti-human TF IgG, or annexin V for 3 h at 4 °C as in panel A, and the amount 125I-FVIIa bound to the cell surface was determined. *, denotes the value significantly (p < 0.05) differs from the control value, i.e. FVIIa bound to HUVEC cells in absence of competitors. C, HUVEC were incubated with wild type 125I-FVIIa (10 nM), 125I-des-FVIIa (10 nM), or 125I-asialo-FVIIa (10 nM) at 4 °C for 3 h, and the FVIIa binding to the cell surface was determined. Values were shown as the percent relative to the binding of wild type FVIIa (n = 3, mean ± S.E.). D, HUVEC were incubated with various concentrations of 125I-FVIIa (0 –100 nM) in the presence or the absence of 2 μM of unlabeled FVIIa, and the specific FVIIa binding to HUVEC was calculated by subtracting the amount of 125I-FVIIa associated with the cells in the presence of unlabeled FVIIa (nonspecific binding) from the amount of 125I-FVIIa associated in the absence of unlabeled FVIIa (total binding). The data shown in the figure represent mean ± S.E. (n = 2–5).

To identify major determinants in FVIIa that are responsible for its binding to endothelial cells, binding experiments were performed with labeled gla-domain less FVIIa (125I-des-FVIIa) and asialo FVIIa (125I-asialo-FVIIa). Gla-less FVIIa showed significantly reduced binding (about 70% lower compared with the wild type FVIIa), indicating the involvement of gla-domain of FVIIa in binding to endothelial cells. In contrast, asialo-FVIIa showed similar binding as that of the wild type FVIIa (Fig. 2C), indicating that sugar moiety of FVIIa is not involved in the binding. This eliminates the involvement of carbohydrate receptors, such as the mannose receptor, which could support the binding of many glycoproteins to the cell surface in a variety of cell types (21, 22). To determine the binding affinity of FVIIa to endothelium and the number of binding sites for FVIIa, we investigated the binding kinetics of increasing concentrations of 125I-FVIIa (0–100 nM) to HUVEC cells in the presence and absence of excess unlabeled FVIIa. The data indicated a Kd value of 32.26 ± 2.00 nM and Bmax of 47.81 ± 1.392 fmol 10−5 cells, which gives an estimated number of 2.8 × 105 FVIIa binding sites per cell (Fig. 2D).

Next, in an attempt to obtain clues as to potential receptor(s) that might be responsible for FVIIa binding to the endothelial cell surface, HUVEC were incubated at 4 °C for 3 h with 10 nM of 125I-FVIIa in the presence or absence of a 100-fold molar excess of various potential competitors: prothrombin, factor IX, factor X, and protein C. The presence of prothrombin and FIX had no effect on 125I-FVIIa binding to HUVEC, but interestingly, FX and protein C both significantly reduced the binding. FX decreased the 125I-FVIIa binding by 40% (p = 0.02; n = 3 to 5), whereas, protein C blocked the 125I-FVIIa binding by 50% (p = 0.02; n = 3–5) (Fig. 3A). The combination of FVIIa/protein C, FVIIa/FX or protein C/FX showed an additional 15–20% more reduction in 125I-FVIIa binding over that was obtained in the presence of a single competitor (Fig. 3B). The combination of three (FVIIa/protein C/FX) blocked the 125I-FVIIa binding further. Overall the data presented in Fig. 3 suggest that FVIIa may share one or more binding sites with protein C and factor X on HUVEC.

FIGURE 3. FVIIa binding site on HUVEC is not a common binding site for vitamin K-dependent clotting proteins.

125I-FVIIa (10 nM) was added to HUVEC in the presence or the absence of a 100-fold molar excess (1 μM) of vitamin K-dependent clotting proteins, factor VIIa, prothrombin, FIX, FX, and protein C alone (A) or in combination (B). At the end of 3 h of incubation at 4 °C, 125I-FVIIa bound to the cell surface was determined (mean ± S.E., n = 3–5). *, the value significantly (p < 0.05) differs from the control value, i.e. FVIIa bound to HUVEC in the absence of competitor. #, the value differs significantly from all other values shown in the graph.

FVIIa Binding to EPCR

Endothelial cells express the protein C receptor, EPCR, on their cell surface. The fact that protein C significantly inhibits 125I-FVIIa binding on endothelial cell surfaces prompted us to verify whether EPCR plays a direct role in FVIIa binding to HUVEC. Monoclonal anti-EPCR antibody (JRK-1494) inhibited the 125I-FVIIa binding to HUVEC in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). EPCR mAbs were as effective or better than a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled FVIIa or protein C in blocking the 125I-FVIIa binding to HUVEC. In the presence of 10 μg/ml anti-EPCR mAb, 125I-FVIIa binding to HUVEC was reduced by 60% or more.

FIGURE 4. FVIIa binds to endothelial cell protein C receptor (EPCR).

A, HUVEC were incubated with varying concentration of anti-EPCR mAb (1–10 μg/ml) for 30 min at 4 °C, followed by incubation with 125I-FVIIa (10 nM) for 3 h at 4 °C. The surface binding of 125I-FVIIa was then determined (n = 3, mean ± S.E.). B, wild-type CHO and EPCR-transfected CHO (CHO/EPCR+) cells were incubated with 125I-FVIIa (10 nM) in the presence or absence of various competitors. At the end of 3 h of incubation at 4 °C, the surface binding of 125I-FVIIa was determined. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (n = 3), *, value(s) significantly (p < 0.05) differs from the control value, i.e. FVIIa bound to CHO/EPCR+ cells in the absence of competitor/inhibitor.

To confirm that EPCR acts as a cellular receptor for FVIIa binding, CHO-K1 cells were stably transfected with an EPCR expression vector. Stable transfection of EPCR was confirmed by FACS analysis (data not shown). The EPCR transfected CHO cells supported about 6–7-fold more 125I-FVIIa binding (39.2 ± 1.32 fmol 10−5 cells) compared with that of untransfected wild type CHO cells (5.6 ± 1.51 fmol 10−5 cells). The presence of anti-EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml) completely blocked the 125I-FVIIa binding to CHO/EPCR+ cells. 125I-FVIIa binding to CHO/EPCR+ cells was also blocked significantly by a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled FVIIa or protein C but not by FIX, FX or prothrombin (Fig. 4B). Similar experiments performed with wild type CHO-K1 cells showed no significant effect of anti-EPCR or of a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled FVIIa on the basal 125I-FVIIa binding to these cells (Fig. 4B). Further experiments to determine the binding of the gla-domain less 125I des-FVIIa to CHO/EPCR+ cells showed that FVIIa binding to EPCR is gla-dependent (data not shown). Overall these data confirm that FVIIa binds to EPCR and the interaction involves the gla domain of FVIIa.

Next, we compared the binding kinetics of FVIIa, FVII, protein C, and APC to EPCR. HUVEC were incubated with increasing concentrations of 125I-FVIIa, 125I-FVII, 125I-protein C, or 125I-APC (0–150 nM) in the presence or absence of anti-EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml). With the concentrations tested, the EPCR-specific binding was near saturable (Fig. 5). Analysis of the binding data using the hyperbola curve-fitting program (Graph Pad Prism 4) gave a calculated Kd value of 43.7 ± 5.21 nM for FVIIa; 44.2 ± 5.51 nM for FVII; 48.1 ± 10.38 nM for protein C; and 37.8 ± 4.75 for APC. The Bmax values are as follow: FVIIa, 79.8 ± 5.64 fmol 10−5 cells (4.8 × 105 binding sites cell−1); FVII, 98.5 ± 5.04 fmol 10−5 cells (5.9 × 105 binding sites cell−1); protein C, 45.5 ± 4.46 fmol 10−5 cells (2.7 × 105 binding sites cell−1); and APC, 63.3 ± 1.8 fmol 10−5 cells (3.8 × 105 binding sites cell−1). In parallel, we also performed binding studies with increasing concentrations of 125I-EPCR mAb (1–10 nM) to determine the number of EPCR sites on endothelial cells. The analysis of EPCR mAb binding data gave a Bmax of 79.9 ± 3.37 fmol 10−5 cells (4.8 × 105 binding sites cell−1), and Kd of 1.5 ± 0.22 nM. The number of estimated binding sites for FVIIa, FVII, and APC on HUVEC was very similar to that of EPCR mAb. Somewhat lower binding of protein C to HUVEC, compared with other ligands, probably reflects loss of some protein C binding species upon iodination. A comparison of unlabeled PC and APC (10–1000 nM) as competitors of 125I-FVIIa binding revealed no significant differences between them in competing with FVIIa binding to EPCR (data not shown).

FIGURE 5. Specific binding kinetics of FVIIa, FVII, protein C and APC to EPCR.

HUVEC were incubated with varying concentrations (0 –150 nM) of 125I-FVIIa (A), 125I-FVII (B), 125I-protein C (C), or 125I-APC (D) in the presence or the absence of anti-EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml) at 4 °C for 3 h. E, HUVEC were incubated with varying concentrations (1–10 nM) of 125I-EPCR mAb ± 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled EPCR mAb. The surface binding of the raidoligand was then determined and the EPCR specific binding was calculated for the each ligand by subtracting the binding values obtained in the presence of EPCR antibody from that obtained in the absence of the antibody. Data are represented in the figure as mean ± S.E. (n = 3–5).

Internalization of FVIIa Bound to EPCR

To determine whether FVIIa bound to EPCR could be internalized, CHO and CHO/EPCR+ (± pretreated with anti-EPCR mAb) cells were incubated with 125I-FVIIa (10 nM), and the amount of 125I-FVIIa associated with the cell surface and internalized was measured. As expected, the surface binding of 125I-FVIIa was 3–4-fold higher in CHO/EPCR+ cells that were not pretreated with anti-EPCR compared with the wild-type CHO or CHO/EPCR+ that were pretreated with anti-EPCR (Fig. 6A). As with the binding, the rate of FVIIa internalization was significantly higher in CHO/EPCR+ in the absence of anti-EPCR (80.1 ± 13.81 fmol h−1 10−5 cells) compared with the wild-type or CHO/EPCR+ cells treated with anti-EPCR (29.2 ± 1.51 fmol h−1 10−5 cells) (Fig. 6B). The amount of FVIIa bound to the cell surface and the rate of FVIIa internalization observed with CHO/EPCR+ cells in the presence anti-EPCR were similar to values obtained with the wild-type CHO cells. Additional studies revealed that the internalization of 125I-FVIIa exposed to HUVEC was significantly lower in cells incubated with anti-EPCR compared with the cells that were exposed to a control vehicle (Fig. 6C). Similarly, inclusion of many-fold molar excess of protein C and APC markedly reduced the internalization of 125I-FVIIa (Fig. 6C). When 125I-FVIIa and unlabeled PC or APC were added to HUVEC at 10 and 70 nM, respectively (concentrations that are equivalent to plasma concentrations of FVII and protein C), FVIIa internalization was inhibited by about 40–50%. Similar data were obtained with zymogen FVII internalization (data not shown). Overall, the above data is consistent with the observation that EPCR facilitates FVII(a) internalization. However, it may be pertinent to note that unlabeled FVIIa is more effective than EPCR mAb, protein C or APC in blocking the internalization of 125I-FVIIa, suggesting that a non-EPCR-dependent mechanism may also contribute to FVIIa endocytosis.

FIGURE 6. EPCR-dependent FVIIa binding and internalization.

Wild type CHO (○), CHO/EPCR+ (▲), and CHO/EPCR+ cells pretreated with anti EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml) (■) were incubated with 125I-FVIIa (10 nM) for varying time periods (0 –120 min) at 37 °C, and the 125I-FVIIa surface binding (A) and internalization (B) were determined. Data are represented as mean ± S.E. (n = 3). C, HUVEC were incubated with a control vehicle or anti-EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml) in buffer B for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were then chilled on ice and incubated with 10 nM 125I-FVIIa in the absence or presence of unlabeled FVIIa, PC or APC (250 nM) for 2 h at 4 °C to allow 125I-FVIIa binding to the cells. Unbound radioactivity was removed by washing the cells thrice with buffer B, the cells were transferred to 37 °C, and at the end of 15 min of incubation 125I-FVIIa internalized was measured. 125I-FVIIa internalized at 4 °C, immediately prior to their incubation at 37 °C, was subtracted from those obtained at 15 min at 37 °C. The values are expressed as mean ± S.E. (n = 3). *, the value differs significantly (p < 0.05) from the control value. D, HUVEC were incubated with a control vehicle (○) or anti-EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml) (■) in buffer B for 30 min at room temperature and then 125I-FVIIa (10 nM) was added to the wells and allowed to incubate at 37 °C. At varying time periods, small aliquots were removed and subjected to trichloroacetic acid precipitation to determine FVIIa degradation (n = 3, mean ± S.E.).

Additional studies revealed that FVIIa internalized via EPCR might not readily enter into the degradative pathway because no significant differences were found in the amount of FVIIa degraded in the presence or absence of EPCR mAb in HUVEC (Fig. 6D) and CHO/EPCR+ cells (data not shown).

EPCR-FVIIa Complexes Do Not Promote Factor X Activation

In our recent study (23), we observed that an unperturbed endothelial cell surface supports the activation of FX, albeit slowly, by FVIIa. As FVIIa binds to EPCR on the endothelial cell surface, we investigated whether the binding of FVIIa to EPCR influences FVIIa activation of FX on the unperturbed endothelium. Non-stimulated HUVEC were incubated with FVIIa (10 nM) and FX (175 nM) in either the presence or absence of anti-EPCR or in the presence of an irrelevant monoclonal antibody. A similar rate of activation of FX by FVIIa was observed in the absence (0.53 ± 0.13 nM h−1) or the presence (0.62 ± 0.14 nM h−1) of anti-EPCR (Fig. 7A). Next, we investigated whether FVIIa binding to EPCR has any influence on TF-FVIIa activation of FX. HUVEC were stimulated with a combination of TNFα and IL-1β to induce TF expression. The rate of FX activation by FVIIa was 100-fold higher on stimulated HUVEC (49.3 ± 5.7 nM h−1) compared with non-stimulated HUVEC, which was completely attenuated by anti-TF IgG (5.2 ± 0.1 nM h−1). In contrast to the effect seen with anti-TF IgG, anti-EPCR had no effect on FVIIa activation of FX (45.8 ± 5.8 nM h−1). These data suggest that FVIIa binding to EPCR has no functional consequences in the generation of FXa on either non-stimulated or stimulated endothelium.

FIGURE 7. FVIIa binding to EPCR does not influence FVIIa activation of FX.

Non-stimulated (A) and stimulated (B) HUVEC were incubated with FVIIa (10 nM), FX (175 nM) in the presence or the absence of anti-EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml), control IgG (10 μg/ml), and anti-TF IgG (25 μg/ml). FXa generation was then determined as described under “Experimental Procedures” (n = 3– 4, mean ± S.E.).

EPCR-FVIIa and PAR Activation

EPCR has been shown to support APC-mediated cell signaling through activation of PAR1 (20, 24, 25). Recent studies suggest that even cryptic TF-FVIIa complexes, which fail to activate factor X, can trigger cell signaling through PAR2 (26). Therefore, we investigated whether EPCR-FVIIa, despite having no activity toward FX, can activate either PAR1 or PAR2. To evaluate this, we measured PAR1 and PAR2 activation by FVIIa, APC, thrombin, or trypsin in CHO/EPCR+ cells that were transfected with either AP-PAR1 or AP-PAR2 reporter constructs. As shown in Fig. 8A, APC treatment activated PAR1 substantially in CHO/EPCR+ cells (AP activity released by 10 nM thrombin treatment represents full activation of PAR1). In contrast, we found no evidence for the activation of PAR1 in CHO/EPCR+ cells that were treated with FVIIa. Similarly, APC and not FVIIa induced the time-dependent activation of p44/42 MAPK in CHO/EPCR+ cells (data not shown). APC treatment had a minimal effect on PAR2 activation, and FVIIa had no effect. These data suggest that FVIIa bound EPCR, unlike APC bound to EPCR, cannot trigger cell signaling by activating PARs. However, pharmacological concentrations of FVIIa, by competing with APC for EPCR, dampened APC activation of PAR1 (Fig. 8B). We observed similar inhibitory effect of FVIIa in APC-mediated activation of p44/42 MAPK (data not shown).

FIGURE 8. Effect of FVIIa and activated protein C on PAR1 and PAR2 activation in cells expressing EPCR.

A, CHO/EPCR+ cells were transfected transiently with AP-PAR1 or AP-PAR2 reporter constructs. The cells expressing AP-PAR1 and AP-PAR2 were treated with FVIIa, APC, thrombin, or trypsin (10 nM each). At the end of 60 min, an aliquot was removed from overlying conditioned medium and the activity of alkaline phosphatase, which was released into the medium following the activation of AP-PAR1 or AP-PAR2, was measured (n = 3, mean ± S.E.). In one experiment, hirudin 2 units/ml, was included with APC and thrombin treatments. B, CHO/EPCR+ cells transfected transiently with AP-PAR1 were exposed to APC (10 nM), FVIIa (100 nM), or APC (10 nM) + FVIIa (100 nM). At the end of 30 min, an aliquot was removed from overlying conditioned medium, and the activity of alkaline phosphatase released into the medium was measured (n = 3, mean ± S.E.). *, value differs significantly (p < 0.05) from the value obtained in the absence of FVIIa.

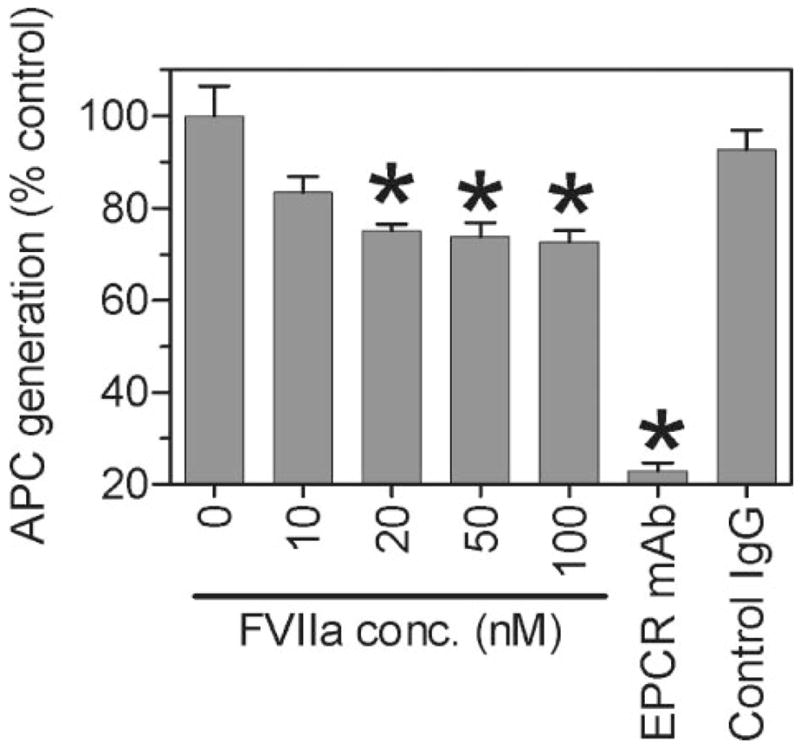

Effect of FVIIa on APC Generation

To determine whether FVIIa binding to EPCR blocks the activation of protein C, CHO/EPCR+ cells were incubated with a plasma concentration of human protein C in the absence or presence of varying concentrations of FVIIa (0–100 nM). FVIIa, in a dose-dependent manner, inhibited protein C activation on CHO/EPCR+ cells. APC generation was reduced by about 25% (p = 0.0193, n = 3) in presence of 20 nM of FVIIa (Fig. 9). However, increasing FVIIa concentration failed to reduce protein C activation further. To confirm whether the APC activity observed in these cells is dependent on EPCR, CHO/EPCR+ cells were pre-treated with anti-EPCR before the addition of protein C and the activator, thrombin. Anti-EPCR antibody blocked the APC generation by about 75% or more (p < 0.0001, n = 3) compared with the control vehicle.

FIGURE 9. Effect of FVIIa on protein C activation.

CHO/EPCR+ cells were incubated with protein C (80 nM) and thrombin (2 nM) in the presence or the absence of varying concentrations of FVIIa (0 –100 nM), anti EPCR mAb (10 μg/ml), and control IgG (10 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding hirudin (2 units/ml) and the activated protein C (APC) generated was measured using the substrate Spectrozyme PCa (2 mM). Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (n = 3) of the percent control of APC generated in absence of FVIIa. *, value differs significantly (p < 0.05) from the control value obtained in the absence of FVIIa or anti-EPCR antibody.

DISCUSSION

The endothelial cell lining constitutes the interface between the vascular tissue and the circulating blood. In their quiescent state, endothelial cells provide a non-thrombogenic surface and express receptors that participate in the anticoagulant mechanism, such as EPCR, but are devoid of procoagulant receptors, such as TF. Tissue factor, which is present normally on non-vascular but not vascular cells (9, 10), is the only known cellular receptor for the coagulation proteins FVII/FVIIa, and the formation of TF-FVIIa triggers activation of the coagulation cascade. Although there is no evidence that the native endothelium can support the initiation of the coagulation cascade, there is evidence that unperturbed endothelial cells do support coagulation by generating FVIIa, FXa, and thrombin (27–30). Our recent studies showed that non-stimulated endothelial cells support a low level of factor X activation by FVIIa independent of TF (23). In addition to supporting the various coagulation reactions on their cell surfaces, the endothelial cells are positioned optimally to play a role in the clearance of circulating plasma proteins. However, there is little information on how FVIIa interacts with non-stimulated EC. The studies reported here reveal that FVIIa binds specifically to non-stimulated HUVEC, and that EPCR, a known receptor for protein C/APC, serves as the binding site for FVII/FVIIa. The formation of FVIIa-EPCR complexes neither support the activation of coagulation on non-stimulated endothelial cells nor modulate TF-FVIIa activation of factor X on stimulated endothelial cells. FVIIa binding to EPCR is shown to facilitate FVIIa endocytosis.

The present study is the first to identify that EPCR serves as a major binding site for FVIIa on endothelial cells. The existence of binding sites for FVII/FVIIa on human EC had been reported earlier (13), and our present data are consistent with some but not all of the observations made in the earlier report. For example, the affinity of FVIIa binding to non-stimulated EC obtained in the present study (Kd, 32 nM) is in good agreement with the published finding (Kd, 45 nM) whereas the calculated number of the binding sites differ by about 10-fold (2.8 × 105 sites/cell versus the reported value of 3.75 × 106 sites/cell). A major difference between the present study and the earlier report (13) was the nature of the FVIIa binding site. The earlier study found that, in addition to FVIIa, other vitamin K-dependent proteins, including prothrombin, reduced the binding of 125I-FVIIa to EC. Based on this, the authors concluded that the binding site was shared by other vitamin K-dependent proteins and did not exhibit specificity for FVIIa. In contrast, in the present study other vitamin K-dependent proteins, except protein C and factor X, failed to reduce the 125I-FVIIa binding to EC, suggesting that the binding site is not a common binding site for vitamin K-dependent proteins. The reason for the difference between our present study, and the earlier report is unclear. One could speculate that a potential contamination of prothrombin with substantial amounts of FVII/FVIIa was partly responsible for the earlier observation (13). Alternatively, differences in cell culture conditions and assay buffers could be a reason.

Our conclusion that EPCR serves as a binding site for FVIIa is supported by a number of observations: (i) a 100-fold molar excess of protein C reduced the 125I-FVIIa binding to EC by 50%, (ii) monoclonal EPCR antibody effectively blocked the 125I-FVIIa binding to EC, and (iii) transfection of CHO cells with an EPCR expression plasmid increased FVIIa binding to the transfected cells by severalfold compared with the wild-type, and this increased binding was markedly reduced by the presence of protein C, and completely attenuated by the presence of EPCR antibody. While the present article was in preparation, Preston et al. (31), as a part of characterizing the protein C gla domain interaction with EPCR using BIAcore, reported that FVIIa bound to soluble EPCR with a comparable affinity to protein C (Kd ~ 150 nM). In these studies, human prothrombin was found to have essentially no sEPCR affinity. These data are consistent with our observation that prothrombin had no effect on FVIIa binding to EPCR on the endothelial cell surface.

At present, it is unclear whether FVIIa binds to non-stimulated EC at sites other than EPCR. As with protein C, a 100-fold molar excess of factor X also reduced the 125I-FVIIa binding to EC. However, it had no effect on 125I-FVIIa binding to EPCR transfected cells. Further, FX does not possess Leu-8 in the gla domain that is present in both FVIIa and protein C. This residue is important for EPCR recognition (31). These data suggest that FVIIa may bind to EC at sites other than EPCR and this site(s) could be a common binding site(s) for both FVIIa (FVII) and FX. Further experiments are needed to support this contention.

It is interesting to note that both FVII and FVIIa bind to EPCR on non-stimulated EC with a similar affinity to that of protein C/APC (32). This supports the notion that EPCR acts a true receptor for FVII/FVIIa. The affinity of FVII as well as protein C to EPCR was relatively weak (Kd, ~40–50 nM range) in comparison with TF-FVIIa interaction on cell surfaces (Kd, ~100 pM to 3 nM) (18, 33, 34). Therefore, it is unlikely that at plasma concentrations of protein C (70 nM) (35), all EPCR sites on the endothelial cell surface are occupied by protein C. When both FVII and protein C were present, the amount of each ligand associated with the EPCR would be approximately proportional to their respective concentrations. Thus at their plasma concentrations, about 15% of EPCR will be occupied by FVII and the rest of it by protein C. However, this would ultimately depend upon many other factors, such as their on- and off-rates, and how their respective plasma inhibitors modulate their interaction with the EPCR.

Unlike TF-FVIIa, EPCR-FVIIa complexes neither activate factor X nor induce cell signaling through activation of PAR1 or PAR2. This suggests that EPCR fails to induce the necessary allosteric conformational changes in FVIIa to enhance its catalytic activity. Because FVII/FVIIa binds to TF with a much higher affinity than to EPCR, it is unlikely that FVIIa binding to EPCR influences the formation of TF-FVIIa complexes on activated endothelial cells. At present, it is unknown whether FVIIa binding to EPCR either on non-stimulated or stimulated EC facilitates TFPI inhibition of FVIIa. In this context, it is interesting to note that recent studies showed that protein S stimulates the inhibition of TF pathway of coagulation by TFPI (36). Although protein S appears to support the TF inhibition by reducing the Ki of the FXa-TFPI complex formation, it will be interesting to see whether protein S and EPCR affect the formation of the quaternary complex of TF-FVIIa-FXa-TFPI.

At present, the physiological importance of FVII/FVIIa binding to EPCR is unclear. Since FVII circulates in plasma at a 7-fold lower concentration than protein C and FVIIa binds to EPCR with a similar affinity to that of protein C, it is unlikely that FVII acts as the major ligand for EPCR. However, in therapeutic conditions, FVIIa levels may be elevated close to protein C levels in blood, and thus may compete with protein C for EPCR binding. However, under these conditions one would not expect a severe reduction in protein C binding to EPCR since FVIIa would first bind to unoccupied EPCR sites before it could compete with protein C. Nonetheless, therapeutic concentrations of FVIIa will have a significant effect on protein C activation as well as on APC-mediated anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory effects.

The relevance of FVII/FVIIa binding to EPCR may not be in modulating the activation of FVII or protein C, and the activities of FVIIa and APC, but in the clearance of FVII and FVIIa from the circulation. The data presented in this manuscript show that the rate of FVIIa internalization is much higher in EPCR-transfected CHO-K1 cells in absence of EPCR mAb than that observed in presence of the antibody or the wild type cells. Similarly, EPCR mAb also reduced FVIIa internalization in HUVEC. This suggests that the internalization of FVIIa is dependent on EPCR. Interestingly, in contrast to FVIIa internalized via TF (19, 37), FVIIa internalized via EPCR was not readily degraded. This raises the possibility that FVIIa endocytosed with EPCR is either retained intracellularly or recycles backs to the cell surface. Further experiments are required to evaluate the fate of endocytosed FVIIa. The plasma inhibitors TFPI and AT were shown to influence TF-dependent FVIIa internalization (37). It would be interesting to investigate whether these inhibitors also influence EPCR-dependent FVIIa internalization and how APC-protease inhibitor complexes affect FVIIa endocytosis.

Overall our present data provide strong evidence that FVII/FVIIa binds to EPCR on endothelial cell surface and suggest that this interaction may play a role in FVIIa endocytosis and could influence the activation of protein C and APC-mediated cell signaling. However, further studies are required to establish the functional significance and consequences of FVII/FVIIa binding to EPCR.

Acknowledgments

We thank Veena Papanna for excellent technical assistance in performing PAR activation studies, Kim Ki-Hyun for generating AP-PAR constructs, Mark Atkinson for critically reading the manuscript, and Naomi Esmon, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, for helpful discussions in revising the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants HL 58869 and HL 65500 from the National Institutes of Health.

The abbreviations used are: FVII, factor VII; FVIIa, activated factor VII; TF, tissue factor; EPCR, endothelial cell protein C receptor; APC, activated protein C; PAR, protease-activated receptor; AP, alkaline phosphatase; TFPI, tissue factor pathway inhibitor; AT, antithrombin; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin.

References

- 1.Fair DS. Blood. 1983;62:784–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loeliger EA, van der Esch B, ter Haar Romney-Wachter CC, Booij HL. Thromb Diath Haemorrh. 1960;4:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seligsohn U, Kasper CK, Osterud B, Rapaport SI. Blood. 1979;53:828–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erhardtsen E. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2000;26:385–391. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasselback R, Hjort PF. J Appl Physiol. 1960;15:945–948. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1960.15.5.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Reilly RA, Aggeler PM, Leong LS. J Clin Investig. 1963;42:1542–1551. doi: 10.1172/JCI104839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjorkman S, Berntorp E. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:815–832. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao LV, Pendurthi UR. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253:131–140. doi: 10.1023/a:1026004208822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drake TA, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS. Am J Pathol. 1989;134:1087–1097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleck RA, Rao LVM, Rapaport SI, Varki N. Thromb Res. 1990;59:421–437. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hjortoe G, Sorensen BB, Petersen LC, Rao LV. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2264–2273. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodgers GM, Broze GJ, Jr, Shuman MA. Blood. 1984;63:434–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuning U, Preissner KT, Muller-Berghaus G. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicolaisen EM, Petersen LC, Thim L, Jacobsen JK, Christensen M, Hedner U. FEBS Lett. 1992;306:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80989-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterns-Kurosawa DJ, Kurosawa S, Mollica JS, Ferrell GL, Esmon CT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10212–10216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu D, Wang Y, Song Y, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:229–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao LVM. Thromb Res. 1988;51:373–384. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(88)90373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le DT, Rapaport SI, Rao LVM. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15447–15454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iakhiaev A, Pendurthi UR, Rao LVM. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45895–45901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludeman MJ, Kataoka H, Srinivasan Y, Esmon NL, Esmon CT, Coughlin SR. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13122–13128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashwell G, Harford J. Annu Rev Biochem. 1982;51:531–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.51.070182.002531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pontow SE, Kery V, Stahl PD. Int Rev Cytol. 1992;137B:221–244. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62606-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh S, Ezban M, Persson E, Pendurthi U, Hedner U, Rao LV. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:336–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riewald M, Petrovan RJ, Donner A, Mueller BM, Ruf W. Science. 2002;296:1880–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.1071699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riewald M, Petrovan RJ, Donner A, Ruf W. J Endotoxin Res. 2003;9:317–321. doi: 10.1179/096805103225002584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahamed J, Versteeg HH, Kerver M, Chen VM, Mueller BM, Hogg PJ, Ruf W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13932–13937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606411103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stern DM, Nawroth PP, Kisiel W, Handley D, Drillings M, Bartos J. J Clin Investig. 1984;74:1910–1921. doi: 10.1172/JCI111611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodgers GM, Shuman MA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:7001–7005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stern D, Nawroth P, Handley D, Kisiel W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:2523–2527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.8.2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao LVM, Rapaport SI, Lorenzi M. Blood. 1988;71:791–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preston RJ, Ajzner E, Razzari C, Karageorgi S, Dua S, Dahlback B, Lane DA. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28850–28857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukudome K, Esmon CT. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26486–26491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broze GJ., Jr J Clin Investig. 1982;70:526–535. doi: 10.1172/JCI110644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakai T, Lund-Hansen T, Paborsky L, Pedersen AH, Kisiel W. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:9980–9988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stenflo J. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1984;10:109–121. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hackeng TM, Sere KM, Tans G, Rosing J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3106–3111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504240103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iakhiaev A, Pendurthi UR, Voigt J, Ezban M, Rao LVM. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36995–37003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.36995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]