Abstract

The human EGF receptor (HER) family members cooperate in malignancy. Of these, HER2 does not bind growth factors and HER3 does not encode an active tyrosine kinase. This diversity creates difficultly in creating pan-specific therapeutic HER family inhibitors. We have identified single amino acid changes in the EGFR and HER3 which create high affinity sequestration of the cognate ligands and may be used as receptor decoys to downregulate aberrant HER family activity. In silico modeling and high throughput mutagenesis were utilized to identify receptor mutants with very high ligand binding activity. A single mutation (T15S; EGFR subdomain I) enhanced affinity for EGF (2-fold), TGF-α (26-fold), and heparin-binding (HB)-EGF (6-fold). This indicates that T15 is an important, previously undescribed negative regulatory amino acid for EGFR ligand binding. Another mutation (Y246A; HER 3 subdomain II) enhanced neuregulin (NRG)1-β binding 8-fold, probably by interfering with subdomain II–IV interactions. Further work revealed that the HER3 subunit of an EGFR:HER3 heterodimer suppresses EGFR ligand binding. Optimization required reversing this suppression by mutation of the EGFR tether domain (G564A; subdomain IV). This mutation resulted in enhanced ligand binding (EGF, 10-fold; TGF-α, 34-fold; HB-EGF, 17-fold; NRG1-β, 31-fold). This increased ligand binding was reflected in improved inhibition of in vitro tumor cell proliferation and tumor suppression in a human non-small cell lung cancer xenograft model. In conclusion, amino acid substitutions were identified in the EGFR and HER3 ECDs that enhance ligand affinity, potentially enabling a pan-specific therapeutic approach for downregulating the HER family in cancer.

INTRODUCTION

The human EGFR (HER) family has four members, EGFR/HER1/ErbB1, HER2/ErbB2, HER3/ErbB3, and HER4/ErbB4, that collectively bind more than eleven canonical ligands including EGF, TGF-α, heparin-binding (HB)-EGF, amphiregulin, betacellulin, epiregulin, epigen, and neuregulin (NRG)1-4 (1–3). Although HER2 is an orphan receptor and does not bind the above ligands, it serves as a signal amplifier by heterodimerization with other HER family members such as HER3 and HER4 (4,5). Dysregulation of HER family members and their cognate ligands is implicated in many cancers and other diseases (6–10). Drugs currently approved for treatment of cancers driven by HER family members are either monoclonal antibodies such as trastuzumab, pertuzumab (both HER2-specific), and cetuximab (EGFR-specific), or small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as gefitinib and erlotinib (EGFR kinase inhibitor) and lapatinib (HER2 >> EGFR kinase inhibitor) (11,12). However, current treatments are only effective in subsets of patients and encounter intrinsic or acquired resistance which could be attributed at least in part to co-expression and ligand activation of other receptor tyrosine kinases (13,14), particularly HER family members (6,12,15–21). To overcome or avoid such resistance, we previously reported a bispecific ligand trap which is an Fc-mediated heterodimer of the EGFR and HER3 ligand binding domains (22,23). This prototypic bispecific ligand trap binds EGFR and HER3 ligands, inhibits proliferation of a broad spectrum of cultured cancer cells, and suppresses growth of tumor xenografts in mouse models.

Crystal structures of the extracellular domains (ECD) have been determined for the EGFR (24–27), HER2 (28,29), HER3 (30), and HER4 (31). Studies of structure-function correlation reveal residues critical for ligand binding, receptor dimerization, and tether formation (24,27,32–36). In the absence of ligands, EGFR, HER3, and HER4 subdomains II and IV of the ECD form an intramolecular autoinhibitory tether. Upon ligand binding, the HER ECD subdomains undergo conformational changes allowing the subdomains I and III to rotate and form a high-affinity ligand binding pocket. Mutagenic disruption of the domain II/IV tether in soluble HER proteins (27,32–35) or C-terminal deletion of subdomain IV (37) improves ligand binding affinity up to 15-fold (27).

The present work describes the results of rational structure-based mutagenesis of the EGFR:HER3 extracellular ligand binding domains. We were able to combine several mutations to create an Fc-mediated triple mutant EGFR:HER3 heterodimer, RB242 (see Figure 3A and B for details). RB242 showed an average of 22-fold improvement in affinity for each of the assayed ligands including EGF, TGF-α, HB-EGF, and NRG1-β. Supporting the concept of better biological activity with an affinity-optimized mutant, RB242 demonstrated improved anti-proliferative activity both in cultured cells and in nude mice bearing tumor xenografts. RB242, an affinity-optimized novel bispecific HER ligand trap, may prove to be a clinically useful alternative to pan-receptor-targeted therapies.

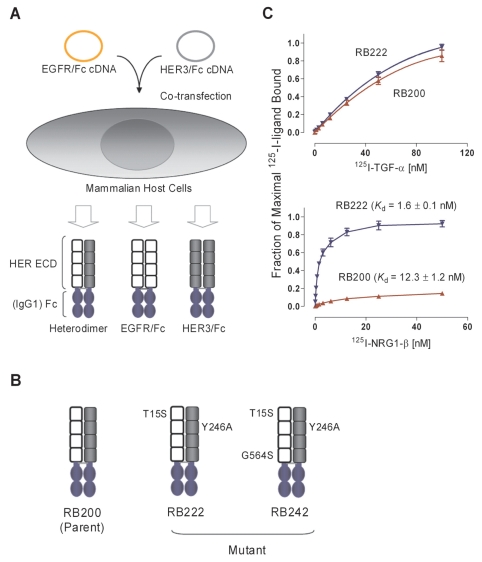

Figure 3.

(A) Schematics showing production of EGFR/Fc and HER3/Fc homodimers as well as EGFR:HER3 heterodimer by co-transfection of EGFR/Fc and HER3/Fc cDNA constructs into mammalian host cells. Conditioned medium harvested from the co-transfected cells were chromatographically purified to obtain the EGFR:HER3 heterodimer (see the Methods for details). (B) Schematics showing the parental EGFR:HER3 heterodimer (RB200) and its derived mutants of RB222 and RB242 with the indicated amino acid substitutions. (C) High-affinity EGFR ligand binding is suppressed in the Fc-mediated EGFR:HER3 heterodimers. 125I-ligand binding was performed in anti-Fc-coated 96-well plates with the indicated purified EGFR:HER3 heterodimers immobilized on the surface. Shown are 125I-TGF-α binding (top), and 125I-NRG1-β binding (bottom). Results are means ± SEM of triplicate wells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Computational Design

Computer modeling of the EGFR ligand binding domain was performed using the co-crystal structures of EGFR-EGF (PDB code IMOX-chain C) (26) and EGFR-TGF-α (PDB code 1IVO-chain C) (25). Computer modeling of HER3 ligand binding domain was done using the structure information of HER3 ECD (PDB code IM6B) (30,38). The affinity design was based on the physical-chemical properties and classification of amino acids such as charge, polarity, aromaticity, etc. Also considered were residue volume, surface area, solvent accessibilities, etc. The PAM250 matrix was used to aid in the prediction of amino acid substitution (39,40).

Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by overlapping PCR which included three sequential PCR reactions each catalyzed by the thermo-stable DNA polymerase Elongase supplemented with pfu (Invitrogen). EGFR/Fc and HER3/Fc cDNAs (23) were used as the PCR templates. Condition set up for the first round PCR with 2 pairs of overlapped PCR primers bearing designed mutations was 94°C 2 min, 94°C 45 sec, 60°C 45 sec, 68°C 3 min for 26 cycles. The two overlapped PCR fragments generated by the first round PCR were gel-purified, combined at 1:1 molar ratio, and used for the second round PCR. The second round PCR annealed the two overlapped PCR fragments using the condition of 94°C 2 min, 94°C 45 sec, 57°C 45 sec, 68°C 30 min for 8 cycles. In the third round PCR, the product of the second round PCR was used as the template. PCR amplification was conducted in the presence of a forward primer that covered the start codon and a reverse primer that covered the stop codon. The PCR condition was 94°C 2 min, 94°C 45 sec, 60°C 45 sec, 68°C 3 min for 26 cycles. PCR products bearing mutations were cloned into the Gateway System plasmid pDONR221 (Invitrogen). Designed mutations were confirmed by complete sequencing. Inserts in pDONR221 were then transferred to the expression vector pcDNA3.2-DEST (Gateway System, Invitrogen) by LR reaction following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Protein Expression and Purification

For ligand binding screening, sequence-confirmed HER1/Fc and HER3/Fc mutants were transiently transfected into HEK293T cells (ATCC) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For expression of the Fc-mediated EGFR:HER3 heterodimers, the EGFR/Fc and HER3/Fc or their mutants were cotransfected into HEK293T cells. The serum-free conditioned media were collected 72 h after transfection. Levels of EGFR/Fc and HER3/Fc homodimers were quantified using the human EGFR or HER3 ELISA Detection Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems). To quantify the Fc-mediated heterodimers, the anti-HER3-coated ELISA plates were used for capture and the EGFR antibody was used for detection.

For scale-up expression of EGFR:HER3 heterodimers, log phase CHO-S cells (Invitrogen) maintained in Pro-CHO5 (Lonza) were transferred into Wave Bio-Reactor (GE HealthCare) at 1x106 cell/ml in Pro-CHO5 supplemented with 8 mM of L-glutamine and 1 x HT (Invitrogen). Next day, cells were co-transfected with the corresponding EGFR/Fc and HER3/Fc cDNA constructs. The transfection was achieved by using the 25 Kd linear PEI (Polysciences) at 12 mg/L. The volume of ProCHO5 was doubled 4 h after transfection. Transfected cells were maintained in Wave Bio-Reactor for 7 d before the conditioned medium was harvested.

A previously described protocol (23) was modified to purify the Fc-mediated EGFR:HER3 heterodimers. Briefly, conditioned medium from co-transfected CHO-S cells was clarified, 10-fold concentrated, and applied to a MabSelect SuRe affinity column (GE Healthcare Biosciences AB). Column was washed extensively with PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) TX-114 and eluted with an IgG elution buffer (Pierce). The eluted fractions were immediately neutralized with 1M Tris-HCL to pH 8.0. Pool of the protein-containing fractions was loaded onto a Ni-Sepharose column (GE-Healthcare Biosciences AB). Column was washed with the Ni-Sepharose Buffer containing 25 mM of imidazole. Bound proteins were eluted with a 25–135 mM of gradient imidazole in the same buffer. The main heterodimer peak was typically eluted between 80–125 nM of imidazole. Pool of the heterodimer-containing fractions from the Ni-Sepharose column was exhaustively dialyzed at 4°C in PBS. Purity of the heterodimer preparations was determined by analytical reversed-phase HPLC.

Screening for Improved Ligand Binding

Screening for binding of europium (Eu)-labeled EGF and NRG1-β by dissociation enhanced lanthanide fluorescence immunoassay (DELFIA, PerkinElmer) was carried out in 96-well yellow plates (Perkin Elmer). Wells were coated with 100 μl of anti-human Fc antibody (5 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature (RT) overnight. Coated plates were rinsed 3 times with PBS/0.05% Tween-20 wash buffer (WB) and blocked with PBS/1% BSA at RT for 2 h. Plates were again rinsed 3 times with WB. The Fc-fusion proteins in conditioned media from the transfected HEK293T cells were diluted with DELFIA binding buffer to a concentration of 20 ng/well and were added to each well (100 μl/well). Plates were incubated at RT for 2h and then rinsed 3 times with DELFIA wash buffer. The plates were then incubated with 100 μl of Eu-EGF (Perkin Elmer) or Eu-NRG1-β (custom-labeled by PerkinElmer) at a concentration of 0.5 nM. The plates were incubated at RT for 2 h followed by three quick rinses with ice-cold DELFIA wash buffer containing 0.02% Tween-20. To quantify bound Eu-ligands 130 μl/well of DELFIA enhancement solution was added and the plates were read on a fluorescence plate reader (Envision, model 2100, PerkinElmer).

Screening for TGF-α and HB-EGF binding was carried out using the TGF-α and HB-EGF ELISA Kit (R&D System). 96-well plates were coated with 100 μl of anti-human Fc antibody at 1 μg/ml at RT overnight. Plates were rinsed and blocked as described above. The Fc-fusion proteins in conditioned media were diluted with PBS/1% BSA to 20 ng/well and were added to wells at 100 μl/well. Plates were incubated at RT for 2 h, followed by rinsing 3 times with WB. TGF-α and HB-EGF (R&D Systems) were diluted to 5 nM with PBS/1% BSA and were added to the plates. The plates were incubated at RT for 2 h followed by rinsing rapidly 3 times with ice cold WB. Bound ligands were detected using the biotinylated detection antibody against TGF-α or HB-EGF. Subsequent ELISA color development steps follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

Procedures for screening EGFR ligand binding (Eu-EGF, TGF-α, and HB-EGF) to the immobilized EGFR:HER3 heterodimers using the conditioned media were identical to the screening for Eu-EGF, TGF-α, and HB-EGF binding described above, except that the plates were pre-coated with anti-human HER3 antibody (DYC1769, R&D Systems) at a concentration of 2 μg/ml and that the Fc-fusion proteins at 100 ng/well from the conditioned media were used for ligand binding.

Eu-Ligand Saturation Binding and Displacement

Eu-EGF and Eu-NRG1-β saturation binding and Eu-EGF displacement were identical to the Eu-EGF binding screening described above, except that purified heterodimers were used and the heterodimer concentrations used for ligand binding were at least 10-fold lower than the Kd’s for the assayed ligands (41). For saturation binding with Eu-EGF, RB200 at 30 ng/well or RB242 at 2 ng/well were immobilized onto the anti-human Fc-coated pates. For saturation binding with Eu-NRG1-β ,2 ng/well of RB200 or RB242 were immobilized. Non-specific binding was determined by the presence of 100-fold excess of the corresponding unlabeled ligands. Displacement assays were performed with Eu-EGF (concentration of 50 nM for RB200 or 5 nM for RB242) added to wells in the presence of increasing concentrations of the indicated unlabeled competitors.

125-Ligand Saturation Binding

125I-EGF was purchased from GE-Healthcare. TGF-α and HB-EGF (R&D Systems) were custom-labeled by GE-Healthcare. 96-well assay plates were coated with 5 μg/ml anti-human Fc antibody. Coated plates were washed and blocked as described above. Conditioned media or purified proteins diluted to 20 ng/well were immobilized in the anti-human Fc-coated wells. Increasing concentrations of the 125I-ligands were used to reach saturation binding. Non-specific binding was determined by the presence of 100-fold excess of the corresponding unlabeled ligands. After binding, washed wells with bound 125I-ligands were covered with 100 μl/well of scintillation cocktail OptiPhase ‘SuperMix’ (PerkinElmer) and were read by Microbeta Trilux (PerkinElmer).

Phosphotyrosine ELISA

Phosphotyrosine ELISA was performed as described (23).

Cell Proliferation Assays

TGF-α- or NRG1-β-induced cell proliferation was conducted in serum-free medium. Cells were plated in 96-well tissue culture plates (Falcon #35-3075, Becton) at 2000 to 5000 cells per well in 100 μl culture medium, as appropriate for each cell line, and then grown overnight (15 to 18 h). The cells were then serum-starved for 24 h and were treated with 3 nM of TGF-α or NRG1-β in the presence of increasing concentrations of the indicated inhibitors for 3 d. Cell proliferation was quantified by the MTS assays. The plate was then read on a plate reader at 490 nm wavelength for absorbance, which was directly proportional to the amount of cells in the well. H1437 cell proliferation assay was performed in growth medium (RPMI1640/10% FBS). Cells were plated in 96-well tissue culture plates at 1000 cells per well in 100 μl culture medium. Next day, cells were treated with increasing concentrations of RB200 or RB242 for 5 d in the same medium. Cell proliferation was quantified by CellTiter-Glo luminescent assay (Promega).

Mouse Tumor Xenograft Model

The H1437 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumor xenograft study was performed in female CD-1 nu/nu nude mice as described (23). Efficacy studies were done in groups of 9 mice. H1437 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640/10% FBS. Cells were harvested with 0.025% EDTA, washed twice with culture medium, resuspended in sterile PBS, and then injected subcutaneously into mice at 6 x 106 cells in 100 μl volume. Tumor measurements were done using a caliper, and tumor volume was calculated from length, width, and cross sectional area. Treatment began when the mean tumor volume reached approximately 100 mm3. Mice were dosed with RB200 or RB242 at 12 mg/kg i.p. in 150 μl volume, 3 times weekly for three weeks. Experiment was carried out under the regulatory guidelines of OLAW Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996), the policies set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and under the IACUC of the Palo Alto Medical Foundation.

Data Analysis

Results from ligand binding, phosphotyrosine ELISA, and cell proliferation assays were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 for nonlinear regression curve fitting (GraphPad Software). Results from mouse tumor xenograft experiments were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test.

RESULTS

Optimization of the EGFR Ligand Binding Domain for Affinity Improvement

We redesigned the EGFR ECD for increased ligand affinity through computer modeling based on the co-crystal structures of the EGFR ECD bound to EGF or TGF-α (25,26). The affinity design was based on the physical-chemical properties and classification of amino acids such as charge, polarity, aromaticity, residue volume, surface area, and solvent accessibilities. The PAM250 matrix was used to aid the prediction of amino acid substitutions (39,40). A total of 85 designed mutants (Supplementary Figure 1) were created by site-directed mutagenesis using the EGFR ECD (aa1-621)/Fc fusion protein as a template (23). Mutants were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells. Secreted EGFR mutants in conditioned media were quantified by ELISA. Twenty of the 85 mutants were not secreted. For the remaining secreted mutants, conditioned media containing equal amounts of the Fc-fusion proteins (20 ng) were directly used for ligand binding screening in anti-Fc-coated 96-well plates.

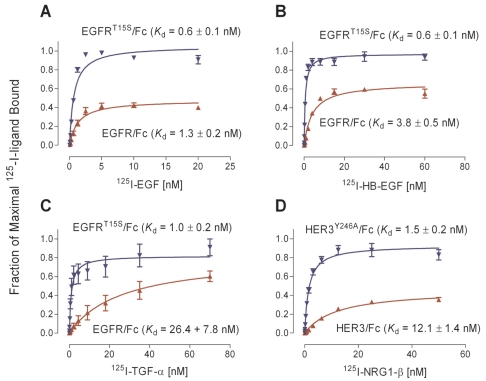

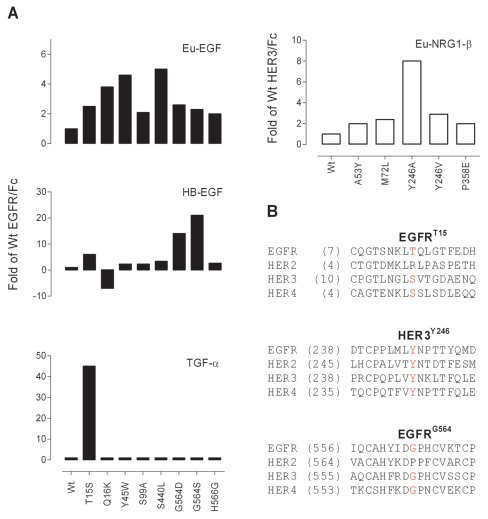

Screening for EGF binding was carried out using Eu-labeled EGF. Eight out of the 65 secreted mutants showed more than 2-fold increase in Eu-EGF binding compared to wild-type (Wt) EGFR/Fc (Figure 1A). The remaining mutants showed similar, decreased, or no detectable binding of Eu-EGF (Supplementary Figure 1). The 8 mutants that showed increased Eu-EGF binding were further assayed for binding of TGF-α and HB-EGF using ELISA-based methods for detection (see Methods). A mutant with a threonine-to-serine change at position 15 of the mature EGFR receptor (EGFRT15S/Fc) was found to have the most improved binding capacity combined for EGF, TGF-α, and HB-EGF (Figure 1A). Binding was repeated using 125I-labeled ligands and similar results were obtained (Figure 2A–C). As shown in Figure 2, EGFRT15S/Fc had a 26-fold improvement in affinity for TGF-α (apparent Kd of 26.4 nM versus 1.0 nM), a 6-fold improvement in affinity for HB-EGF (apparent Kd of 3.8 nM versus 0.6 nM), and a 2-fold improvement in affinity for EGF (apparent Kd of 1.3 nM versus 0.6 nM).

Figure 1.

(A) Ligand binding screening identifies EGFR/Fc and HER3/Fc mutants with enhanced affinity for EGF, TGF-α, HB-EGF, and NRG1-β. Screening was carried out in anti-Fc-coated 96-well plates as detailed in the Methods. Mutants with increased ligand binding from initial screening were selected for saturation binding to determine the apparent ligand binding affinity. Shown are mutants with affinity equal to or greater than 2-fold of that of the Wt molecules. (B) Amino acid sequence alignments of HER family proteins reflecting the conserved residues of EGFRT15 (top), HER3Y246 (middle), and EGFRG564 (bottom). Positions of the first aligned residues are shown in parentheses.

Figure 2.

EGFRT15S/Fc and HER3Y246A/Fc have improved affinity for their cognate ligands. Saturation binding of 125I-Ligands was performed in anti-Fc-coated 96-well plates with the indicated HER/Fc proteins immobilized on the surface. Binding data were plotted as fractions of maximal 125I-ligands bound. Shown are 125I-EGF binding (A), 125I-TGF-α binding (B), 125I-HB-EGF binding (C), and 125I-NRG1-β binding (D). Results are means ± SEM of triplicate wells.

A receptor phosphorylation assay was performed to compare the inhibitory activity of EGFRT15S/Fc with that of the parent EGFR/Fc. N87 gastric cancer cells, known to express cell surface EGFR (42), were serum-starved and treated with EGF or TGF-α in the presence of increasing concentrations of EGFR/Fc or EGFRT15S/Fc. Phosphorylation of the full-length, membrane-bound EGFR was measured by a pan-phosphotyrosine antibody. A dose-dependent inhibition of ligand-induced EGFR phosphorylation by EGFR/Fc or EGFRT15S/Fc was demonstrated (Supplementary Figure 3). The mutant molecule was ~6-fold more potent than the parent molecule in inhibition of EGF-induced EGFR phosphorylation (Table 1, EC50 of 2 nM versus 12 nM) and 11-fold more potent in inhibition of TGF-α-induced EGFR phosphorylation (EC50 of 1 nM versus 11 nM).

Table 1.

Affinity-optimized mutants are more potent than their parent forms in inhibition of growth factor-induced EGFR and HER3 phosphorylation

| Approximate EC50 (nM)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| EGF | TGF-α | NRG1-β | |

| EGFR/Fc | 11.6 | 11.4 | NT |

| EGFRT15S/Fc | 2.2 | 1.0 | NT |

| HER3/Fc | NT | NT | 45.5 |

| HER3Y246A/Fc | NT | NT | 1.5 |

| RB200 | 117.3 | 199.0 | 25.1 |

| RB242 | 1.8 | 19.4 | 1.7 |

Shown are the EC50 values for HER/Fc-mediated inhibition of receptor phosphorylation. Serum-starved cells were treated with 3 nM EGF or TGF-α (N87 cells), or with NRG1-β (MCF7 cells), in the presence of increasing concentrations of the homodimer and heterodimer inhibitors. Cells were lyced 10 min later. Lysates were analyzed for the presence of phosphorylated EGFR or HER3 using a quantitative phosphotyrosine-ELISA assay. NT: not tested.

Optimization of HER3 Ligand Binding Domain for Affinity Improvement

Next, we redesigned the HER3 ligand binding domain for affinity improvement following a similar approach used for EGFR/Fc optimization. The published structure information of HER3 ECD (30) was used for computational design. Because there is no ligand-bound receptor crystal structure available, we performed in silico prediction and created a total of 120 mutants (Supplementary Figure 2). Screening for improved binding of Eu-NRG1-β identified five mutants with a >2-fold affinity improvement (Figure 1A). A tyrosine-to-alanine mutation at position 246 (HER3Y246A/Fc), which is located in the dimerization arm involved in the subdomain II–IV tether contact, demonstrated an 8-fold improvement in affinity for 125I-NRG1-β (Figure 2D), and was selected for further work.

HER3/Fc and HER3Y246A/Fc were compared for their potencies in inhibition of NRG1-β-induced HER3 phosphorylation. MCF7 breast cancer cells known to express a high level of cell surface HER3 (43) were serum-starved, and treated with NRG1-β in the presence of increasing concentrations of HER3/Fc or HER3Y246A/Fc. As shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 3, HER3Y246A/Fc was 30-fold more potent than HER3/Fc (EC50 of 1.5 nM versus 45 nM).

Optimized HER3/Fc Suppresses Ligand Binding by Optimized EGFR

EGFRT15S/Fc was co-expressed with HER3Y246A/Fc in HEK293T cells, and the resulting heterodimer (RB222, see Figure 3A and B) was purified to ~95% homogeneity as described for RB200 (23). Ligand binding demonstrated that RB222 retained the improved affinity for 125I-NRG1-β compared with the parent heterodimer RB200 (Kd of 1.6 nM versus 12.3 nM, Figure 3C). Surprisingly however, RB222 no longer possessed the improved affinity for EGFR ligands. As shown in Figure 3C, heterodimers RB200 and RB222 each had an apparent Kd >30 nM for 125I-TGF-α (binding was not saturated at 100 nM of 125I-TGF-α), while the EGFRT15S/Fc homodimer displayed a Kd of ~1.0 nM for the same ligand (Figure 2C). We concluded that the HER3 ECD suppresses the high-affinity binding of the EGFR ECD when they are locked in an Fc-mediated heterodimer.

A G564S Mutation Restores the High-Affinity Binding of EGFR Ligand to RB222

To restore the high-affinity EGFR ligand binding to the heterodimer RB222, we introduced additional single mutations into the EGFR arm of RB222, focusing on its subdomain II/IV tether region. A novel method was devised for efficient screening for EGFR ligand binding to the EGFR:HER3 heterodimer mutants in the conditioned media without prior purification. EGFR:HER3/Fc heterodimers as well as HER3/Fc homodimers in the conditioned media were immobilized on the surface of 96-well plates which were pre-coated with anti-human HER3 (ECD-specific) antibody. This was followed by binding of EGFR ligands to the immobilized EGFR:HER3/Fc heterodimers. An important advantage of this method is that conditioned medium containing a mixture of heterodimers and homodimers can be screened directly for the heterodimer-specific EGFR ligand binding without removal of the contaminating homodimers. Ten heterodimer mutants were created and screened using this method. A mutant named RB242 with a G564S mutation located in subdomain IV of the autoinhibitory tether was recovered which showed restored high-affinity EGFR ligand binding (see below). RB242 was subsequently purified to ~95% homogeneity and assayed for its ligand binding affinity.

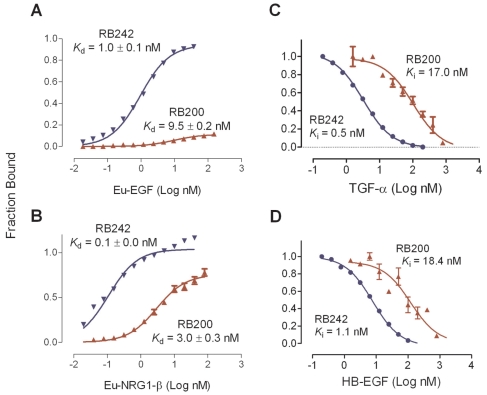

All initial ligand affinity screening performed above allowed us to obtain and compare the apparent (not true) Kd values (44). In order to determine the true Kd’s, we used the apparent Kd’s as a starting point to calibrate the saturation binding such that the concentration of an assayed receptor was at least 10-fold lower than the measured Kd for the assayed ligand. When binding assays were performed following this mathematic relationship (see Methods for details) (44), RB242 demonstrated a 10-fold improvement over RB200 in affinity for Eu-EGF (Kd of 1.0 nM versus 9.5 nM) and a 31-fold improvement in affinity for Eu-NRG1-β (Kd of 0.1 nM versus 3.1 nM, Figure 4A and B). Competitive ligand binding was performed to displace Eu-EGF binding by unlabeled TGF-α or HB-EGF. In these ligand displacement assays, RB242 demonstrated a 34-fold improvement over RB200 in affinity for TGF-α (Ki of 0.5 nM versus 17.0 nM), and a 17-fold improvement in affinity for HB-EGF (Ki of 1.1 nM versus 18.4 nM, Figure 4C and D).

Figure 4.

RB242 has restored high-affinity for EGFR ligands. Ligand binding was performed in anti-Fc-coated 96-well plates using the optimized ligand binding conditions as detailed in the Methods. Saturation binding of Eu-EGF and Eu-NRG1-β (A, B). Displacement of Eu-EGF with unlabeled TGF-α or HB-EGF (C, D). Results were representatives of three independent experiments, and were normalized to fractions of receptors bound with ligands (with the largest mean value in each dataset defined as 1).

Purified RB200 and RB242 were assayed for their ability to inhibit EGFR and HER3 phosphorylation. A dose-dependent inhibition of ligand-induced EGFR phosphorylation by RB200 or RB242 was demonstrated in N87 cells and MCF7 cells (Supplementary Figure 3). As suggested by the increased ligand binding affinity, RB242 was 65-fold more potent than RB200 in inhibition of EGF-induced EGFR phosphorylation (Table 1, EC50 of 1.8 nM versus 117.3 nM), and 10-fold more potent in inhibition of TGF-α-induced EGFR phosphorylation (EC50 of 19.4 nM versus 199.0 nM). Similarly, RB242 was 15-fold more potent than RB200 in inhibition of NRG1-β-induced HER3 phosphorylation in MCF7 cells (Table 1, EC50 of 1.7 nM versus 25.1 nM).

RB242 is More Potent than RB200 in Inhibition of Proliferation of Cultured Tumor Cells

The effects of RB200 and RB242 on proliferation of cultured monolayer tumor cells were compared. Proliferation of BxPC3 pancreatic cancer cells was induced by TGF-α or NRG1-β in serum-free medium. Growth factor-induced BxPC3 proliferation was inhibited by RB200 or RB242 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5A, top panels). The estimated EC50 indicated that RB242 was ~5-fold more potent than RB200 in inhibition of TGF-α- or NRG1-β-induced proliferation in a 3-day proliferation assay. As much as a 200% increase in inhibition was seen in RB242-treated BxPC3 cells. This presumably resulted from proliferation of BxPC3 cells in serum-free condition which was inhibited by RB242. Similarly, serum-starved MCF7 breast cancer cells were induced to proliferate by NRG1-β; this proliferation was inhibited by RB200 or RB242 (Figure 5A, bottom left panel). The estimated EC50 indicated that RB242 was 7-fold more potent than RB200 in a 5-day proliferation assay. Proliferation of human H1437 NSCLC cells was analyzed in growth medium (RPMI1640/10% FBS) with increasing concentrations of RB200 or RB242. As shown in Figure 5A (bottom right panel), RB242 was about 5-fold more potent than RB200 in a 5-day proliferation assay (EC50 of 18.9 nM versus 100.7 nM).

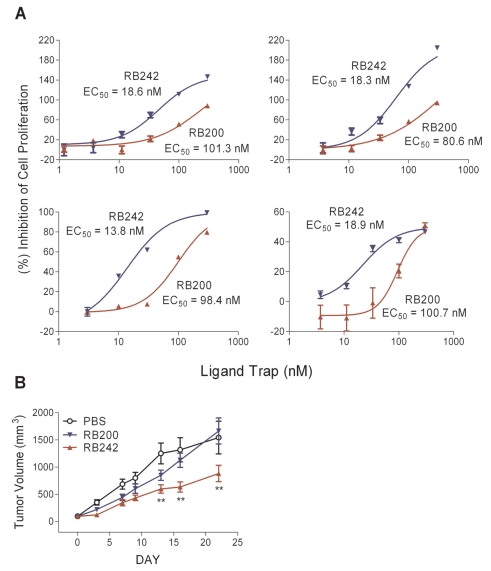

Figure 5.

(A) RB242 is more potent than RB200 in inhibition of proliferation of cultured tumor cells. (Top panels) Serum-starved BxPC3 pancreatic cancer cells were treated with 3 nM of either TGF-α (top left) or NRG1-β (top right) for 3 days in the presence of increasing concentrations of RB200 or RB242. (Bottom left) Serum-starved MCF7 cells were treated with 3 nM of NRG1-β for 3 days in the presence of increasing concentrations of RB200 or RB242. (Bottom right) Proliferation of H1437 NSCLC cells in growth medium (RPMI1640/10%FBS) for 5 days in the presence of increasing concentrations of RB200 or RB242. Cell proliferation was quantified as described in the Methods. Results are means ± SEM of 8 or 16 replicates. Approximate EC50 values for BxPc3 cells were determined with the constraint type set to top constant equal to 100. (B) RB242 has improved anti-tumor activity in a mouse tumor xenograft model. Nude mice were transplanted with H1437 NSCLC cells subcutaneously as described in the Methods. When the tumor volume reached approximately 100 mm3, the mice were treated with either PBS vehicle (○) or RB200 (▾) or RB242 (▴) at 12 mg per Kg administered intra-peritoneally 3 times weekly for 3 weeks. There were 9 mice per each treatment group. Data are expressed as mean tumor volume ± SEM. ** = P < 0.01 by two way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post test.

RB242 Demonstrates Improved Anti-Tumor Activity in a Mouse Model of Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

In vivo efficacy of RB200 and RB242 was compared in nude mice bearing tumors derived from human H1437 NSCLC cells. This model was chosen because RB200 and RB242 showed direct antiproliferative activity in vitro (Figure 5A, bottom right) (23). H1437 cells were injected subcutaneously and allowed to grow to ~100 mm3 before treatment started. In this model, RB200 dosed at 12 mg/kg showed a trend in growth inhibition of the established tumors (Figure 7P > 0.05). Administered at the same dose, RB242 demonstrated improved anti-tumor activity with ~50% inhibition of tumor growth after two weeks of treatment (P < 0.01), consistent with its enhanced inhibitory activity in cultured tumor cells (Figure 5A).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we scanned the ECDs of the EGFR and HER3 in silico for amino acid changes that would impact ligand binding. The amino acid changes made were based upon crystallographic studies of the ECD of the EGFR complexed with TGF-α (25) or EGF (25,26), the structure of the HER3 ECD (30), and previous work indicating that negative interactions dominate HER ligand specificity and affinity (45). We predicted amino acid changes that could release the subdomain II–IV ‘tethering’ interactions, thus favoring a structure in which the EGFR and HER3 extracellular domains would prefer the high-affinity conformation (24,27,33,34,37) and in which other changes would stabilize the ligand-receptor complex (46).

A total of 85 and 120 molecules were screened as variants of EGFR/Fc or HER3/Fc homodimers. A subset of the variants (24% of EGFR/Fc) were not secreted from transfected 293T cells, and were not further characterized. Of the remaining candidate molecules, 88% of the EGFR variants and 96% of the HER3 variants had similar, reduced, or no detectable binding of Eu-EGF or Eu-NRG1-β, respectively. Despite rational design based upon known structures only 12% of EGFR and 4% of HER3 variants showed >2-fold increase in binding affinity for ligands. This low frequency of high-affinity binding molecules is likely due to inconsistencies between crystal and solution structures, and other aspects of ligand-receptor associations which are not understood (27).

The T15S EGFR ECD mutation has not been previously reported. Among the 67 EGFR mutants screened, EGFRT15S/Fc is the only one with improved affinity for multiple ligands (EGF, TGF-α, and HB-EGF). Thr15 of EGFR is conserved among the ligand-binding HER family proteins but not in the orphan receptor HER2 (Figure 1B). The EGFR ECD crystal in complex with TGF-α (25) suggests that Thr15 of EGFR forms direct contact with the conserved Cys32 of mature TGF-α via a 3.1 Å hydrogen bond (Supplementary Figure 4). A Thr15-to-Ser mutation likely shortens the hydrogen bond from 3.1 Å to 2.7 Å (measured with Swiss-PdbViewer) (47), suggesting that this may be one of the possible mechanisms for more stable binding between the EGFR ECD and TGF-α. This possibility can be extended to the improved affinity for EGF and HB-EGF since Cys at this position is 100% conserved among HER ligands.

HER3Y246A/Fc showed a significant improvement in affinity for NRG1-β. Y246A is conserved among all HER members (Figure 1B). It is a critical residue implicated in stabilization of the receptor dimers and subdomain II/IV tethers (34). Data from crystallographic studies indicate that Y246 of HER3 forms direct intramolecular contact with D562 and K583 via hydrogen bonds (30). However, unlike Y246A mutation in HER3/Fc, the same mutation in the EGFR/Fc abolishes its high-affinity binding of EGF (Supplementary Figure 1). This is presumably because Y246A is also involved in stabilization of the receptor dimers (34), and receptor dimerization is required for the high affinity binding of cognate ligands by soluble EGFR/Fc but not required by soluble HER3/Fc (our unpublished observation). Presumably for a similar reason, Y246 mutations in full-length EGFR abolish its high-affinity binding of EGF and impair receptor function (34). Mutations at Y246 in HER3 have not been previously reported. However, an sHER3H565F mutant, which weakens or releases the subdomain II–IV intramolecular tether, results in a 5-fold higher affinity for NRG (33). Thus, mutagenic disruption from either side of the subdomain II/IV tether allows higher HER3 ECD ligand binding affinity.

Our ligand binding assays revealed a negative effect of the HER3 ECD on EGFR ligand binding in the Fc-mediated EGFR:HER3 heterodimeric configuration. Affinity modulation due to heterodimerization of HER members has been previously reported. A high-affinity NRG binding site is created by HER2/3 or HER2/4 heterodimerization (4,5), but suppression of high-affinity EGF binding by HER3 has not been previously described. Our study predicted that a conformational constraint occurred in the ligand binding domain of EGFR as a result of heterodimerization with HER3 ECD. We hypothesized that the intramolecular tether (24,30,48) of the EGFR failed to release upon ligand binding, and that a HER3 ECD-derived conformational constraint keeps the EGFR ECD in a locked (inactive) configuration. Our hypothesis seems to be supported by mutagenic disruption of the domain II/IV tether. A Gly564-to-Ser mutation restored EGFR ligand binding affinity (Kd or Ki change from 9.1 nM to 1.0 nM, 17.0 nM to 0.5 nM, and 18.4 nM to 1.1 nM for EGF, TGF-α, and HB-EGF, respectively). Alternatively, the G564A mutation might affect the subdomain IV-mediated receptor-receptor interaction within the heterodimer leading to a reorientation of subdomains I and III in the opposite strand (24,30,48). In this context, the triple mutant heterodimer (RB242) not only demonstrated improved affinity for EGFR ligands, but also further enhanced HER3 ligand binding of NRG1-β (Kd change from 3.1 nM to 0.1 nM). Gly564 is conserved among the ligand binding HER family proteins (Figure 1B). It forms direct contact with Y251 via a hydrogen bond, and plays an important role in tether formation (30). While a Gly564-to-Pro mutation was reported to have little effect on both EGF binding and receptor function in full-length membrane EGFR (49), several other subdomain IV tether mutations in soluble EGFR ECD generated increased high-affinity binding sites (24,27,34,37), emphasizing again the discrepancy between soluble and full-length membrane receptors (34). In the present study, a Gly564-to-Ser mutation reversed the negative effect of HER3 ECD on EGFR ligand binding. Whether natural transmembrane HER3 can suppress full-length EGFR in ligand binding is not yet known.

We don’t know why the G564D and G564S mutants increase HB-EGF and Eu-EGF binding, but have no effect on TGF-α binding (see Figure 1A). However, we predict that, as mentioned earlier, mutations at G564 may have an effect on the subdomain IV–IV interactions within the receptor dimer, leading to a reorientation of subdomains I and III (24,30,48), to such an extent as to positively affect the binding of HB-EGF and Eu-EGF, but not TGF-α.

Burgess’s group previously reported that EGFR-501, a truncated ectodomain of EGFR which removes the tether on subdomain IV, has enhanced affinity for EGFR ligands (37). Its affinity is further increased upon its C-terminal fusion to an Fc (personal communication). Thus, it would be interesting to compare the affinity of EGFR-501-Fc with our mutants in the same assays.

Cell-based assays confirm that RB242 is about 10- to 60-fold more potent than RB200 in inhibition of ligand-induced HER phosphorylation, and is about 5- to 7-fold more potent in inhibition of serum growth factor-induced tumor cell proliferation. Our in vivo studies demonstrated that RB242 is more potent in inhibition of growth of tumor xenografts derived from human H1437 NSCLC cells in nude mice. These results show a correlation between increased ligand binding affinity and improved in vitro and in vivo anti-proliferative activity of pan-HER-targeted ligand traps.

Resistance to single-targeted anti-HER agents such as cetuximab may be attributed in part to multiple HER co-activation (12,15,16,19–21,50). One strategy to reduce resistance and improve efficacy of HER-targeted therapies is to simultaneously inhibit multiple HER family members (23). RB242, a rationally designed mutant with improved affinity for the majority of HER ligands, may represent a unique single molecule entity capable of implementing this anti-cancer therapeutic strategy.

Supplemental Data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Jay Sarup, Douglas Kawahara, and Dan Maneval for helpful discussions on this research, and Scott Patton for excellent editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–37. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olayioye MA, Neve RM, Lane HA, Hynes NE. The ErbB signaling network: receptor heterodimerization in development and cancer. EMBO J. 2000;19:3159–67. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neve RM, Lane HA, Hynes NE. The role of overexpressed HER2 in transformation. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(Suppl 1):S9–13. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_1.s9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sliwkowski MX, Schaefer G, Akita RW, et al. Coexpression of erbB2 and erbB3 proteins reconstitutes a high affinity receptor for heregulin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14661–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzpatrick VD, Pisacane PI, Vandlen RL, Sliwkowski MX. Formation of a high affinity heregulin binding site using the soluble extracellular domains of ErbB2 with ErbB3 or ErbB4. FEBS Lett. 1998;431:102–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00737-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–82. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Horst EH, Murgia M, Treder M, Ullrich A. Anti-HER-3 MAbs inhibit HER-3-mediated signaling in breast cancer cell lines resistant to anti-HER-2 antibodies. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:519–27. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Normanno N, De Luca A, Bianco C, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in cancer. Gene. 2006;366:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Normanno N, Bianco C, Strizzi L, et al. The ErbB receptors and their ligands in cancer: an overview. Curr Drug Targets. 2005;6:243–57. doi: 10.2174/1389450053765879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shepard HM, Lewis GD, Sarup JC, et al. Monoclonal antibody therapy of human cancer: taking the HER2 protooncogene to the clinic. J Clin Immunol. 1991;11:117–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00918679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. Epidermal growth factor receptor targeting in cancer. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:369–85. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Britten CD. Targeting ErbB receptor signaling: a pan-ErbB approach to cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1335–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nahta R, Yuan LX, Zhang B, Kobayashi R, Esteva FJ. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterodimerization contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11118–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritter CA, Perez-Torres M, Rinehart C, Guix M, Dugger T, Engelman JA, Arteaga CL. Human breast cancer cells selected for resistance to trastuzumab in vivo overexpress epidermal growth factor receptor and ErbB ligands and remain dependent on the ErbB receptor network. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4909–19. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koutsopoulos AV, Mavroudis D, Dambaki KI, et al. Simultaneous expression of c-erbB-1, c-erbB-2, c-erbB-3 and c-erbB-4 receptors in non-small-cell lung carcinomas: correlation with clinical outcome. Lung Cancer. 2007;57:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sergina NV, Moasser MM. The HER family and cancer: emerging molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:527–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sergina NV, Rausch M, Wang D, Blair J, Hann B, Shokat KM, Moasser MM. Escape from HER-family tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy by the kinase-inactive HER3. Nature. 2007;445:437–41. doi: 10.1038/nature05474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hynes NE, Horsch K, Olayioye MA, Badache A. The ErbB receptor tyrosine family as signal integrators. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8:151–9. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wheeler DL, Huang S, Kruser TJ, et al. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to cetuximab: role of HER (ErbB) family members. Oncogene. 2008;27:3944–56. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arpino G, Gutierrez C, Weiss H, et al. Treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing breast cancer xenografts with multiagent HER-targeted therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:694–705. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shepard HM, Jin P, Slamon DJ, Pirot Z, Maneval DC. Herceptin. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;181:183–219. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-73259-4_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarup J, Jin P, Turin L, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER-1:HER-3) Fc-mediated heterodimer has broad antiproliferative activity in vitro and in human tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3223–36. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson KM, Berger MB, Mendrola JM, Cho HS, Leahy DJ, Lemmon MA. EGF activates its receptor by removing interactions that autoinhibit ectodomain dimerization. Mol Cell. 2003;11:507–17. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrett TP, McKern NM, Lou M, et al. Crystal structure of a truncated epidermal growth factor receptor extracellular domain bound to transforming growth factor alpha. Cell. 2002;110:763–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00940-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogiso H, Ishitani R, Nureki O, et al. Crystal structure of the complex of human epidermal growth factor and receptor extracellular domains. Cell. 2002;110:775–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00963-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawson JP, Bu Z, Lemmon MA. Ligand-Induced Structural Transitions in ErbB Receptor Extracellular Domains. Structure. 2007;15:942–54. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho HS, Mason K, Ramyar KX, Stanley AM, Gabelli SB, Denney DW, Jr, Leahy DJ. Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the Herceptin Fab. Nature. 2003;421:756–60. doi: 10.1038/nature01392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrett TP, McKern NM, Lou M, et al. The crystal structure of a truncated ErbB2 ectodomain reveals an active conformation, poised to interact with other ErbB receptors. Mol Cell. 2003;11:495–505. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho HS, Leahy DJ. Structure of the extracellular region of HER3 reveals an interdomain tether. Science. 2002;297:1330–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1074611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouyain S, Longo PA, Li S, Ferguson KM, Leahy DJ. The extracellular region of ErbB4 adopts a tethered conformation in the absence of ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15024–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507591102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawson JP, Berger MB, Lin CC, Schlessinger J, Lemmon MA, Ferguson KM. Epidermal growth factor receptor dimerization and activation require ligand-induced conformational changes in the dimer interface. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7734–42. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7734-7742.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kani K, Park E, Landgraf R. The extracellular domains of ErbB3 retain high ligand binding affinity at endosome pH and in the locked conformation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15842–57. doi: 10.1021/bi0515220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker F, Orchard SG, Jorissen RN, et al. CR1/CR2 interactions modulate the functions of the cell surface epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22387–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozcan F, Klein P, Lemmon MA, Lax I, Schessinger J. On the nature of low- and high-affinity EGF receptors on living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5735–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601469103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilmore JL, Gallo RM, Riese DJ. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-S442F mutant displays increased affinity for neuregulin-2beta and agonist-independent coupling with downstream signalling events. Biochem J. 2006;396:79–88. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elleman TC, Domagala T, McKern NM, et al. Identification of a determinant of epidermal growth factor receptor ligand-binding specificity using a truncated, high-affinity form of the ectodomain. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8930–9. doi: 10.1021/bi010037b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwede T, Kopp J, Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL: An automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3381–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dayhoff MO. Atlas of Protein Sequence and Structure. Silver Spring: National Biomedical Research Foundation; 1978. p. 470. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson WA. Rapid and Sensitive Sequence Comparison with FASTP and FASTA. In: Doolittle R, editor. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; San Diego: 1990. pp. 63–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Limbird LE. Cell surface receptors: a short course on theory and methods. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rusnak DW, Lackey K, Affleck K, et al. The effects of the novel, reversible epidermal growth factor receptor/ErbB-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, GW2016, on the growth of human normal and tumor-derived cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2001;1:85–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knuefermann C, Lu Y, Liu B, et al. HER2/PI-3K/Akt activation leads to a multidrug resistance in human breast adenocarcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:3205–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Limbird LE. Cell surface receptors : a short course on theory and methods. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishing; 1986. p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Woning SP, van RW, Nabuurs SB, et al. Negative constraints underlie the ErbB specificity of EGF-like growth factors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40033–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wells A, Harms B, Iwabu A, Koo L, Smith K, Griffith L, Lauffenburger DA. Motility signaled from the EGF receptor and related systems. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;327:159–77. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-012-X:159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–23. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burgess AW, Cho HS, Eigenbrot C, et al. An open-and-shut case? Recent insights into the activation of EGF/ErbB receptors. Mol Cell. 2003;12:541–52. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattoon D, Klein P, Lemmon MA, Lax I, Schlessinger J. The tethered configuration of the EGF receptor extracellular domain exerts only a limited control of receptor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:923–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307286101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bianco R, Troiani T, Tortora G, Ciardiello F. Intrinsic and acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors in human cancer therapy. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(Suppl 1):S159–71. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.