Summary

There has been some controversy as to whether vertebrate pannexins are related to invertebrate innexins. Using statistical, topological and conserved sequence motif analyses, we establish that these proteins belong to a single superfamily. We also demonstrate the occurrence of large homologues with C-terminal proline-rich domains that may have arisen by gene fusion events. Phylogenetic analyses reveal the orthologous and paralogous relationships of these homologues to each other. We show that different sets of orthologous paralogues underwent sequence divergence at markedly different rates, suggesting differential pressures through evolutionary time promoting or restricting sequence divergence. We further show that the first 2 TMS-containing halves of these homologues underwent sequence divergence more slowly than the second 2 TMS-containing halves and analyze these differences. These bioinformatic analyses should serve as useful guides for future studies of structure, function and evolutionary aspects of this important superfamily.

Keywords: Innexin, pannexin, gap junctions, animal membranes, intercellular flow

1. Introduction

In 2003, we published sequence, topological and phylogenetic analyses of junctional proteins from animals (Hua et al., 2003). We described four previously recognized families as follows: (1) two gap junction protein families, the connexins (found only in chordates) (Alexopoulos et al., 2004; Evans and Martin, 2002) and the innexins (found primarily in invertebrates but also in vertebrates and other chordates) (Bauer et al., 2005; Panchin, 2005; Phelan, 2005; Sasakura et al., 2003), as well as (2) two tight junctional constituents, the claudins (Van Itallie and Anderson, 2006) and the occludins (Feldman et al., 2005). The members of all four families have similar topologies with four α-helical transmembrane segments (TMSs), and all exhibit well-conserved extracytoplasmic cysteines that either are known to or potentially can form disulfide bridges.

A multiple alignment of the sequences of each family was used to derive average hydropathy and similarity plots as well as phylogenetic trees. The data generated led to the following evolutionary, structural and functional suggestions: (1) In all four families, the most conserved regions of the proteins are the four TMSs although the extracytoplasmic loops between TMSs 1 and 2, and TMSs 3 and 4 are usually well conserved. (2) The phylogenetic trees revealed sets of orthologues except for the innexins where phylogeny primarily reflects organismal source, possibly due to a lack of relevant invertebrate genome sequence data. (3) The two halves of the connexins exhibit similarities suggesting that they were derived from a common origin by an intragenic duplication event. (4) Conserved cysteyl residues in the connexins and innexins pointed to a similar extracellular structure involved in the docking of hemi-channels to create intercellular communication channels. (5) We suggested a similar role in homomeric interactions for conserved extracellular residues in the claudins and occludins.

The lack of sequence or motif similarity between the four different families indicated that if they did evolve from common ancestral genes, they had diverged considerably to fulfill separate, novel functions. We suggested that internal duplication was a general evolutionary strategy used to generate new families of channels and junctions with unique functions (see Saier, 2003a,b).

In this report, we statistically analyze sequence comparisons and show first, that the innexins and pannexins are members of a single superfamily as originally suggested by Panchin et al. (2000), but disputed by Bruzzone et al. (2003) and Phelan (2005), second, that the innexins and pannexins exhibit common conserved motifs as well as common topologies, and third, that one group of pannexins, the pannexin 2 orthologues, possess large, unique, C-terminal, proline-rich, hydrophilic extensions that may have arisen by a gene fusion event. Our average hydropathy and average similarity plots reveal the probable topological properties of the members of this superfamily, and a phylogenetic tree shows the relatedness of representative sets of pannexins and innexins. We identify four conserved residues plus three well-conserved motifs common to all members of this superfamily. We use the term “superfamily” to describe the homologues of innexins because of the large number of constituent members, and because of their extensive sequence divergence.

2. Innexins and Pannexins are Members of a Single Superfamily

The proteins included in this study are presented in Table 1. As can be seen, they derive from a variety of invertebrates and vertebrates. The protein sizes vary considerably, but most full-length homologues are of about 400 (300–500) residues. Some are smaller, but most of these are believed to be fragments or putative products of pseudogenes (see Table 1). Others are larger and possess extra hydrophilic domains (as for the pannexins 2). These last mentioned domains are not represented in the CDD or Pfam database, and their function seems to be unknown.

Table 1.

Members of the Innexin/Pannexin superfamily included in this study1

| Abbreviation | Organism | Protein Size | GI # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pannexins | |||

| Bta1 | Bos taurus | 425 | 76674501 |

| Bta2 | Bos taurus | 639 | 76617339 |

| Bta3 | Bos taurus | 392 | 76657274 |

| Cfa1 | Canis familiaris | 426 | 73987804 |

| Cfa2 | Canis familiaris | 582 | 73968865 |

| Cfa3 | Canis familiaris | 392 | 73954928 |

| Dre1 | Danio rerio | 417 | 41055476 |

| Dre2 | Danio rerio | 472 | 94733329 |

| Dre3 | Danio rerio | 397 | 68367600 |

| Hsa1 | Homo sapiens | 426 | 39995064 |

| Hsa2 | Homo sapiens | 633 | 16418341 |

| Hsa3 | Homo sapiens | 392 | 16418453 |

| Mmu1 | Mus musculus | 426 | 86262134 |

| Mmu2 | Mus musculus | 667 | 68522178 |

| Mmu3 | Mus musculus | 392 | 86262155 |

| Rno1 | Rattus norvegicus | 426 | 45476996 |

| Rno2 | Rattus norvegicus | 664 | 45476997 |

| Rno3 | Rattus norvegicus | 392 | 45476998 |

| Tni1 | Tetraodon nigroviridis | 345 | 47211113 |

| Tni2 | Tetraodon nigroviridis | 609 | 47225783 |

| Tni3 | Tetraodon nigroviridis | 343 | 47223826 |

| Innexins | |||

| Annelida | |||

| Hme1 | Hirudo medicinalis | 414 | 25264684 |

| Hme2 | Hirudo medicinalis | 398 | 25264687 |

| Hme3 | Hirudo medicinalis | 479 | 77997501 |

| Hme4 | Hirudo medicinalis | 421 | 77997503 |

| Hme5 | Hirudo medicinalis | 413 | 77997505 |

| Hme6 | Hirudo medicinalis | 480 | 77997507 |

| Hme7 | Hirudo medicinalis (fragment) | 141 | 77997509 |

| Hme8 | Hirudo medicinalis (fragment) | 221 | 77997511 |

| Hme9 | Hirudo medicinalis | 412 | 77997513 |

| Hme10 | Hirudo medicinalis (fragment) | 272 | 77997515 |

| Hme11 | Hirudo medicinalis | 420 | 77997517 |

| Hme12 | Hirudo medicinalis | 381 | 77997519 |

| Cnidaria | |||

| Hvu1 | Hydra vulgaris | 396 | 86769609 |

| Insecta | |||

| Aga1 | Anopheles gambiae str. PEST | 393 | 55240888 |

| Aga2 | Anopheles gambiae str. PEST | 441 | 55239046 |

| Aga3 | Anopheles gambiae str. PEST | 376 | 55233868 |

| Aga4 | Anopheles gambiae str. PEST | 361 | 55233857 |

| Aga5 | Anopheles gambiae str. PEST | 356 | 55233856 |

| Aga6 | Anopheles gambiae str. PEST | 386 | 116116396 |

| Aga7 | Anopheles gambiae str. PEST | 373 | 21288531 |

| Ame1 | Apis mellifera (triplication) | 765 | 66561454 |

| Bmo1 | Bombyx mori | 337 | 40949811 |

| Bmo2 | Bombyx mori | 359 | 45775782 |

| Bmo3 | Bombyx mori | 371 | 54111988 |

| Hvi2 | Heliothis virescens | 307 | 48926842 |

| Dme1 | Drosophila melanogaster | 362 | 129075 |

| Dme2 | Drosophila melanogaster | 367 | 10720056 |

| Dme3 | Drosophila melanogaster | 395 | 10720057 |

| Dme4 | Drosophila melanogaster | 367 | 11386891 |

| Dme5 | Drosophila melanogaster | 419 | 41019525 |

| Dme6 | Drosophila melanogaster | 481 | 12643925 |

| Dme7 | Drosophila melanogaster | 438 | 10720055 |

| Dme8 | Drosophila melanogaster | 372 | 12644213 |

| Sam1 | Schistocerca americana | 361 | 10720059 |

| Sam2 | Schistocerca americana | 359 | 10720060 |

| Sfr1 | Spodoptera frugiperda | 359 | 37781375 |

| Tci3 | Toxoptera citricida | 393 | 52630963 |

| Nematoda | |||

| Cel2 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 419 | 21264468 |

| Cel3 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 420 | 12643734 |

| Cel4 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 554 | 74960058 |

| Cel5 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 447 | 44889063 |

| Cel6 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 389 | 12643866 |

| Cel7 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 556 | 10720049 |

| Cel8 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 382 | 21264467 |

| Cel9 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 382 | 74966908 |

| Cel10 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 559 | 10720050 |

| Cel11 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 465 | 10720052 |

| Cel12 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 408 | 67460980 |

| Cel13 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 385 | 74958810 |

| Cel14 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 434 | 12643626 |

| Cel15 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 382 | 74959920 |

| Cel16 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 372 | 74959921 |

| Cel17 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 362 | 50400811 |

| Cel18 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 412 | 75017319 |

| Cel19 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 454 | 74959869 |

| Cel20 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 483 | 74961824 |

| Cel21 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 481 | 75022996 |

| Cel22 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 508 | 75022997 |

| Cel23 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 423 | 10719983 |

| Cel24 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 522 | 418153 |

| Cel25 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 386 | 10720325 |

| Mollusca | |||

| Aca1 | Aplysia californica | 405 | 54398898 |

| Aca2 | Aplysia californica | 416 | 54398902 |

| Aca3 | Aplysia californica | 406 | 54398904 |

| Aca4 | Aplysia californica | 413 | 54398900 |

| Aca5 | Aplysia californica | 406 | 60550112 |

| Aca6 | Aplysia californica | 424 | 60550114 |

| Aca7 | Aplysia californica | 423 | 89118243 |

| Aca8 | Aplysia californica | 373 | 60550118 |

| Cli1 | Clione limacina | 426 | 8515128 |

| Cli2 | Clione limacina (fragment) | 120 | 14210377 |

| Cli3 | Clione limacina (fragment) | 104 | 14210379 |

| Cva1 | Chaetopterus variopedatus | 399 | 15706257 |

| Platyhelminthes | |||

| Dja1 | Dugesia japonica (fragment) | 236 | 86355173 |

| Dja2 | Dugesia japonica | 466 | 86355153 |

| Dja3 | Dugesia japonica | 483 | 86355155 |

| Dja4 | Dugesia japonica | 445 | 86355157 |

| Dja5 | Dugesia japonica | 399 | 86355159 |

| Dja6 | Dugesia japonica (fragment) | 51 | 86355175 |

| Dja7 | Dugesia japonica | 407 | 86355161 |

| Dja8 | Dugesia japonica | 434 | 86355163 |

| Dja9 | Dugesia japonica | 439 | 86355165 |

| Dja10 | Dugesia japonica | 415 | 86355167 |

| Dja11 | Dugesia japonica | 438 | 86355169 |

| Dja13 | Dugesia japonica | 399 | 86355171 |

Select innexins and pannexins are included in this study. All proteins included were identified in the SwissProt database. The table presents the abbreviations of the proteins used in this study (column 1), their organismal sources (column 2), the protein sizes in numbers of amino acyl residues (column 3) and the GenBank Index numbers (GI #) (column 4).

Using the GAP program (Devereux et al., 1984) with default settings and 100 random shuffles, results obtained are recorded in Table 2. A sequence alignment upon which a representative result is based is shown in Figure 1. In Table 2, the three human pannexins are compared with invertebrate innexins, and the three zebra fish pannexins are similarly compared with invertebrate innexins. In all cases, excellent comparison scores were obtained. Thus, the percent identities were between 25 and 34%, the percent similarities ranged between 36 and 46%, and the comparison scores (expressed in standard deviations (S.D.)) ranged from 15 to 23.

Table 2.

Comparison of vertebrate pannexins with invertebrate innexins1

| Pannexin | Innexin | # Residues compared | % Identity | % Similarity | Comparison score (S.D.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hsa1 | Dja1 | 81 | 33 | 45 | 15 |

| Hsa2 | Dja1 | 151 | 26 | 36 | 23 |

| Hsa3 | Hme2 | 255 | 25 | 36 | 17 |

| Dre1 | Hme5 | 88 | 34 | 46 | 21 |

| Dre2 | Hme3 | 106 | 29 | 42 | 16 |

| Dre3 | Cel11 | 227 | 28 | 40 | 20 |

The GAP program (Devereux et al., 1984) was run with default settings and 100 random shuffles. For two of these comparisons (Hsa3 with Hme2 and Dre3 with Cel11), most of the two sequences were compared. In other cases, the regions of greatest sequence similarity (including TMSs 1 and 2) were selected to optimize the comparison (see Saier, 1994). Hsa, Homo sapiens (humans); Dre, Danio rerio (zebrafish); Dja, Dugesia japonica (flatworm); Hme, Hirudo medicinalis (leech); Cel, Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworm).

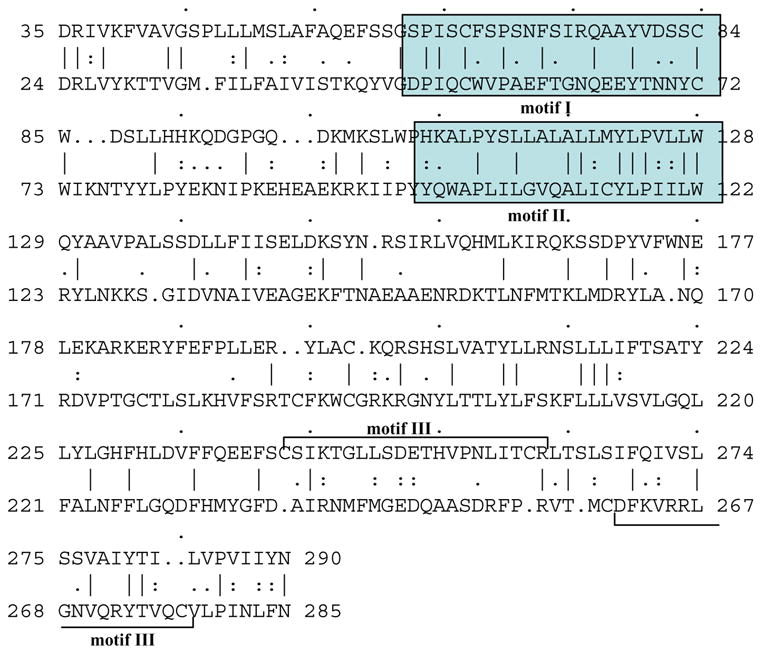

Fig. 1.

Alignment of almost all of Hsa3 (pannexin 3 of man; top sequence) with almost all of Hme2 (innexin 2 of the leech; bottom sequence). The GAP program (Devereux et al., 1984) was used to generate the alignment which gave a comparison score of 17 S.D. (see Table 2). Numbers at the beginning and end of each line indicate residue numbers in the proteins. *, identity; :, close similarity, ●, more distant similarity as defined by the GAP program. Motifs 1 and 2 which align are boxed and shaded. Motif 3 which does not align in the two sequences is overlined (top sequence) or underlined (bottom sequence).

Our extensive studies on integral membrane proteins and protein domains have shown that when two proteins exhibit a comparison score of 9 S.D. or greater, they are related by common descent (Saier, 1994; 2003a,b). A value of 9 S.D. corresponds to a probability of 10−19 that these proteins could have exhibited this degree of sequence similarity purely by chance (Dayhoff et al., 1983). We have never come across an example where two homologues exhibiting a comparison score of 9 S.D. or better have been shown to have evolved independently. The comparison scores obtained when vertebrate pannexins are compared with invertebrate innexins are far in excess of what is required to establish homology. Earlier investigators failed to establish homology because they provided no equivalent statistical analyses.

In Figure 1, the actual alignment of a human pannexin with a leech innexin is shown. In our opinions, there is no question that the proteins compared are homologous. Employing the superfamily principle (Doolittle, 1986), we therefore consider it established that the proteins that have been designated as “pannexins” are in the innexin superfamily (see the Innexin Family, TC #1.A.25, in the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB), www.tcdb.org) (Busch and Saier, 2002; Saier et al., 2006). The next section identifies and describes the most conserved motifs in these proteins.

3. Three Conserved Motifs Shared by Innexins and Pannexins

A well-conserved motif in the innexins has been identified and suggested to be the signature sequence for this family (Barnes, 1994). This motif, YYQWV, can be found in the alignment shown in Figure 1 (Motif II, boxed). Although the YYQWV is not well conserved between all innexins and pannexins included in this study, this motif plus the flanking region (23 residues included) exhibit 39% identity and 61% similarity (Fig. 1), the highest observed for any extended region in these proteins.

Preceding this region are the two fully conserved cysteyl residues, present in all innexins and pannexins included in our study (see Fig. S1 on our website: http://biology.ucsd.edu/~msaier/supmat/InnPan). The sequence alignment is shown in Figure 1 (Motif I, boxed, 24 residues included). This conserved motif shows 37% identity and 58% similarity. Motif I is known to occur in the first extracellular loop separating TMSs 1 and 2 (Phelan, 2005; Phelan and Starich, 2001). Motifs I and II are the best-conserved regions of these proteins.

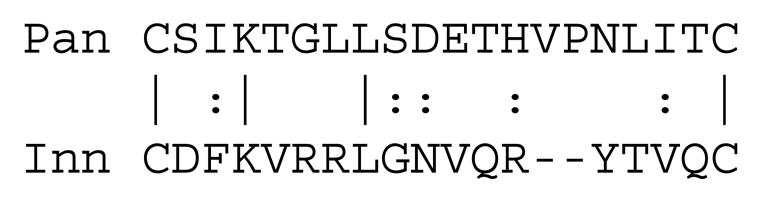

Innexins have two well-conserved pairs of cysteyl residues in extracellular loop 2, between TMSs 3 and 4, but only one of these pairs is fully conserved. The two fully conserved cysteyl residues of the innexins are misaligned in both Figure 1 and Figure S1 with those of the pannexins. However, the fully conserved pair of cysteines in the innexins are separated most frequently by 17 residues, and the fully conserved pair of cysteines in the pannexins are also separated by 17 residues (underlined or overlined motifs III in Fig. 1). When the consensus sequences of these two regions were optimally aligned, the alignment showed 20% identity and 45% similarity (9 out of 20 similarities plus identities; see Fig. 2). Although these two regions do not align in the binary or multiple alignment, we suggest that they share a common origin. Insertions or deletions introduced during evolutionary divergence of the innexins relative to the pannexins presumably account for this misalignment.

Fig. 2.

Alignment of the second fully conserved pair of cysteyl residues in the pannexins (Hsu3, Pan, top) with the fully conserved pair of cysteyl residues in the innexins (Hmo2, Inn, bottom). The alignment, taken from Figure 1, shows 20% identity and 45% similarity. Vertical lines represent identities while colons represent similarities.

4. A Lack of Significant Sequence Similarity Between Connexins and Innexins

All of the sequences of the innexins and pannexins included in this study were compared with 250 connexin sequences using the IC program (Zhai and Saier, 2002). In no case did a resultant comparison score exceed 5 S.D. Although this result does not exclude the possibility that the innexins and connexins arose from a common ancestor, it provides no evidence for this possibility. It also shows that pannexins are far more similar to innexins than either of these two protein types are to connexins.

5. Short and Large Innexin Sequences

Among the innexins are virally derived innexins (e.g., from the Hyposoter didymator virus (363 amino acyl residues, gi# 27475782), not reported in our earlier review (Hua et al., 2003)). Insect virus-encoded innexins have been noted previously (Phelan, 2005). Proteins annotated as pannexins now can be found in the NCBI database from, for example, Aplysia californica and Clione limacina. Moreover, half-sized protein sequences with only two putative TMSs are now available in the NCBI database (e.g., pannexin 2 and pannexin 3 from Clione limacina; 120 aas, gi# 14210377 and 109 aas; gi# 14210379, respectively). They may be due to incomplete sequencing, sequencing errors, errors in exon identification or to the presence of pseudogenes.

All pannexin-2s are substantially larger than the other members of the innexin superfamily. Thus, pannexins-2 are larger than pannexins-1 and -3 by 200-300 residues (see Table 1). This is due to a large hydrophilic extension at the C-termini of pannexin-2s. This C-terminal domain proved to be proline (and alanine) rich and is present only in the pannexins-2 within the innexin superfamily. However, it was also found in many proteins of dissimilar function from bacteria and eukaryotes. These include a C-terminal region of the large tegument-like protein, UL36 of Gallid herpesvirus-2 (3342 aas; gi# 10180741), a C-terminal region of the surface antigen, PHGST#5 of Trypanosoma cruzi (796 aas; gi# 2209012), an N-terminal region of transcription factor TFIID of Homo sapiens (1083 aas; gi# 2058326), and a C-terminal region of the alginate regulatory protein AlgR3 of Pseudomonas syringae (318 aas; gi# 28867376). In these proteins, repeat units of 20–24 residues could be identified in the regions of sequence similarity with the pannexin-2 hydrophilic domains.

6. Innexin/Pannexin Residue Identity

A multiple alignment of 97 representative invertebrate innexins and vertebrate pannexins was generated using the Clustal X program (Thompson et al., 1997) (see Fig. S1 on our website; http://biology.ucsd.edu/~msaier/supmat/InnPan). Examination of the multiple alignment for the proteins included in this study revealed 3 residues that are fully conserved (see Fig. S1 and Phelan, 2005). These are (1) two cysteyl residues at alignment positions 201 and 221 (see Fig. S1) and (2) a prolyl residue at alignment position 348. Additionally, a tryptophanyl residue at alignment position 352 is fully conserved in all homologues except the Hydra vulgaris protein, Hvu1. This is contrary to the work reported by Phelen (2005) who reported an alignment where the tryptophan residues in the innexins did not align with those in the pannexins. This difference presumably reflects the proteins selected for study as well as the different assumptions made in designing the two programs used to generate the multiple alignments. Several residue types are also well conserved in the same regions of the multiple alignment, providing further evidence for homology between innexins and pannexins (see motif analysis above).

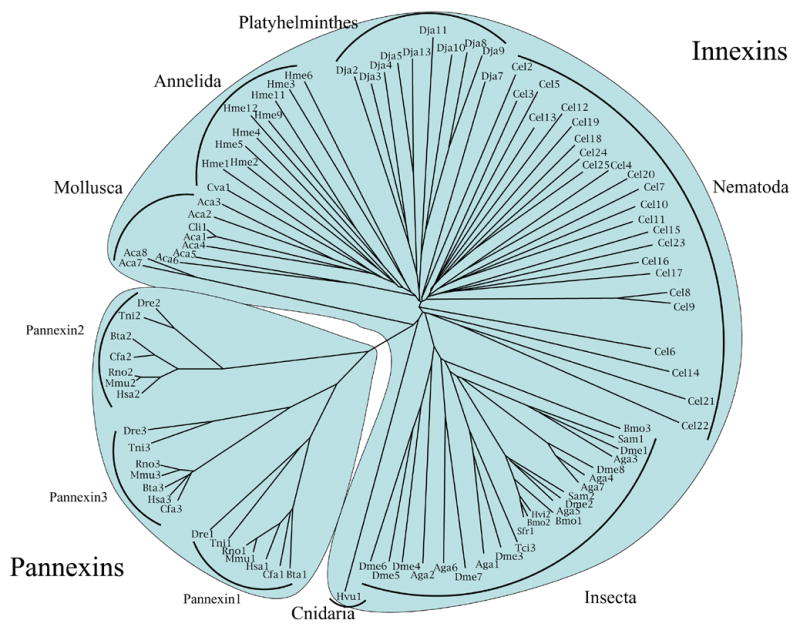

7. Innexin/Pannexin Phylogeny

The phylogenetic tree for the innexins and pannexins is shown in Figure 3. This tree, based on the CLUSTAL X multiple alignment (see Fig. S1), was drawn using the TREEVIEW program (Zhai et al., 2002). As can be seen, the vertebrate pannexins cluster separately from the invertebrate homologues, and the three isoforms (pannexins 1, 2 and 3) fall into three well-defined subclusters. Interestingly, mammalian pannexins 3 have diverged in sequence from each other less than the mammalian pannexins 1 and 2 have diverged from each other. However, the non-mammalian pannexins do not show the same trend. Dre2 and Tni2 have diverged from each other the least; Dre1 and Tni1 have diverged the most, and Dre3 and Tni3 have apparently diverged from each other at an intermediate rate. Divergence between mammalian and non-mammalian pannexins appears to have occurred at still different relative rates: isoforms 3 the most, isoforms 2 the least, and isoforms 1 at intermediate rates. Thus, for the mammalian orthologues, the relative divergence rates were 1 > 2 > 3; for the non-mammalian representatives they were 1 > 3 > 2, and between these two groups, they were 3 > 1 > 2. This unexpected observation suggests that these proteins have been under differential evolutionary pressure since the time when these groups of organisms began to diverge from each other.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of representative vertebrate pannexins and invertebrate innexins which cluster separately as labeled. The three pannexin isoforms (pannexins 1, 2 and 3) are so designated. The innexins cluster according to organismal source type. The pannexins and innexins are shaded separately.

The innexins in Figure 3 fall into groups that in general correlate with organismal type. Thus, mollusks, annelids, flatworms and roundworms appear in different parts of the tree, although it should be noted that four of the Aplysia californica paralogues (Aca5 and 6 as well as Aca7 and 8) branch from points distant from branching points for the other 4 paralogues. Further, seven of the C. elegans paralogues branch from points distant from the branch that includes the 19 other paralogues shown. The latter proteins fall into three diffuse subclusters (Fig. 3). Finally, the Hydra vulgaris innexin (Hvu1) is found on its own branch, distant from all other homologues. Altogether, there are 16 deeply rooted branches, each of which can be considered to represent a distinct family within the innexin/pannexin superfamily.

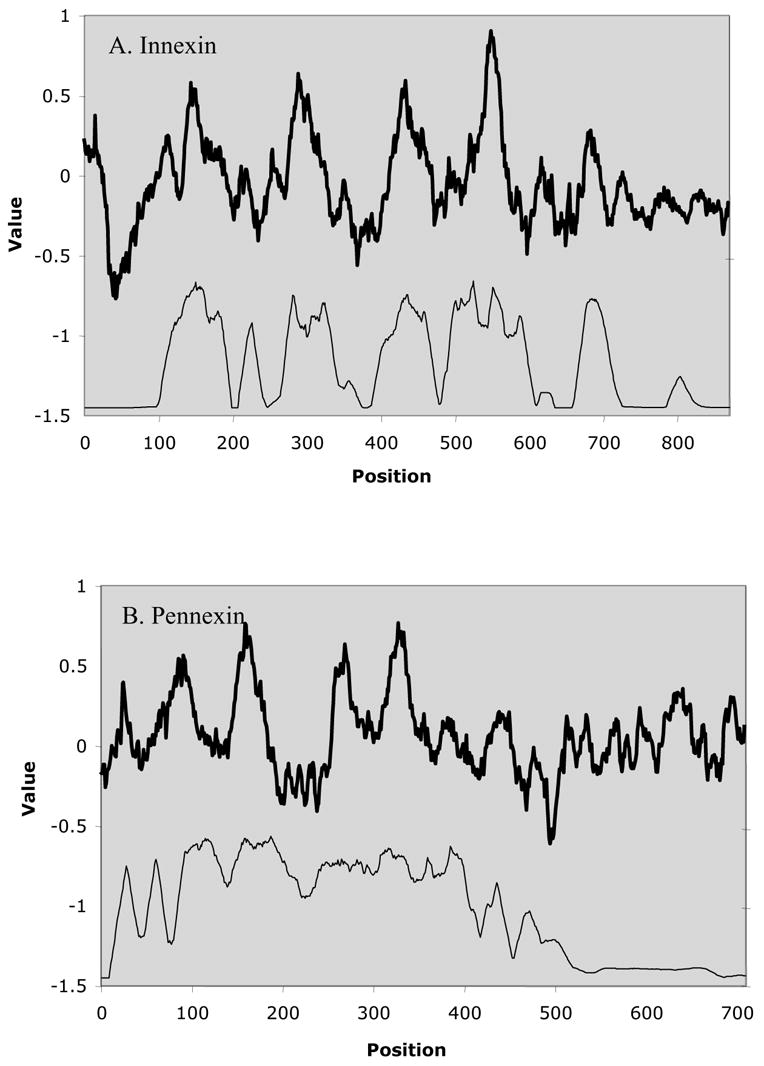

8. Hydropathy Profiles of Innexins versus Pannexins

The average hydropathy (top) and similarity (bottom) plots for the innexins (Fig. 4A) and pannexins (Fig. 4B) reveal strikingly similar profiles. These plots are based on the multiple alignments shown in Figures S2 and S3 on our website. Both show four dominant hydrophobic peaks that are well conserved. In both plots, TMSs 1 and 2 are better conserved than TMSs 3 and 4. This is particularly apparent with the pannexins. These peaks and the extracytoplasmic domains between TMSs 1 and 2 and TMSs 3 and 4 are well conserved as noted before for the entire family (Hua et al., 2003). It is also worthy of note that regions preceding the odd-numbered TMSs and following the even-numbered TMSs are fairly well conserved, suggesting important structural and functional roles for these cytoplasmic regions. The similarities of peaks 1 and 2 with peaks 3 and 4 suggest (as we have proposed; Hua et al., 2003) that these proteins arose by an internal gene duplication event from a 2 TMS precursor. However, we could not prove this suggestion to be true using our statistical tools. The results presented in Figure 4 provide further support that innexins and pannexins are related by common descent (Sobczak and Lolkema, 2005a,b).

Fig. 4.

Average hydropathy (dark line; top) and average similarity (thin line, bottom) for the Innexins (A) and the Pannexins (B). The AveHAS program (Zhai and Saier, 2001) was used to derive the plots. The CLUSTAL X-derived multiple alignments (Figs. S2 and S3) presented on our website (http://biology.ucsd.edu/~msaier/supmat/InnPan) were used to derive these plots.

9. Conclusions

In this report we have presented unequivocal statistical evidence showing that innexins and pannexins belong to a single superfamily and therefore arose from a single precursor peptide. Three fully conserved residues as well as a tryptophan residue conserved in all but one of the homologues were identified. Moreover, two well-conserved motifs were identified among all of these proteins providing further evidence for homology. One of these motifs contains two fully conserved extracellular cysteines (between TMSs 1 and 2). We also identified regions in the C-terminal halves of the innexins and the pannexins which contain two fully conserved cysteines and exhibit sequence similarities between the innexins and the pannexins that suggest homology. The fact that the N-terminal halves are better conserved than the C-terminal halves suggests that the former segments share an essential, universal function while the latter segments have diverged for more specialized functions. It is possible that these 4 TMS proteins arose from 2 TMS precursor peptides (Saier, 2003a,b), but at present, there is no direct evidence for this hypothesis. Future studies will be required to identify these proposed subfunctions.

We have identified apparent domain fusions in pannexin 2 proteins, suggesting an additional function for these hydrophilic domains. Such a function could be regulation, targeting or macromolecular interaction. This observation suggests that pannexin 2s have a subfunction that is unique to this set of proteins. Further studies should clarify this issue.

The results presented in this paper provide guides for future studies. Such studies will be required to establish the structural and functional significance of the many observations reported here. They may also lead to a more detailed understanding of the evolutionary origins of this important class of transcellular communication channels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jean Claude Herve for encouraging us to prepare this article and for critical suggestions. This work was supported by NIH grant GM077402 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. We thank Mary Beth Hiller for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexopoulos H, Bottger A, Fischer S, Levin A, Wolf A, Fujisawa T, Hayakawa S, Gojobori T, Davies JA, David CN, Bacon JP. Evolution of gap junctions: the missing link? Curr Biol. 2004;14:R879–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TM. OPUS: a growing family of gap junction proteins? Trends Genet. 1994;10:303–305. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Loer B, Ostrowski K, Martini J, Weimbs A, Lechner H, Hoch M. Intercellular communication: the Drosophila innexin multiprotein family of gap junction proteins. Chem Biol. 2005;12:515–526. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, Hormuzdi SG, Barbe MT, Herb A, Monyer H. Pannexins, a family of gap junction proteins expressed in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13644–13649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233464100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch W, Saier MH., Jr The Transporter Classification (TC) System, 2002. CRC Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;37:287–337. doi: 10.1080/10409230290771528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayhoff MO, Barker WC, Hunt LT. Establishing homologies in protein sequences. Methods Enzymol. 1983;91:524–545. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)91049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle RF. Of urfs and orfs: a primer on how to analyze derived amino acid sequences. University Science Books; Mill Valley, CA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Evans WH, Martin PE. Gap junctions: structure and function. Mol Membr Biol. 2002;19:121–136. doi: 10.1080/09687680210139839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman GJ, Mullin JM, Ryan MP. Occludin: structure, function and regulation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:883–917. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua VB, Chang AB, Tchieu JH, Nielsen PA, Saier MH., Jr Sequence and phylogenetic analyses of 4 TMS junctional proteins of animals: Connexins, innexins, claudins and occludins. J Mem Biol. 2003;194:59–76. doi: 10.1007/s00232-003-2026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchin YV. Evolution of gap junction proteins–the pannexin alternative. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1415–1419. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchin Y, Kelmanson I, Matz M, Lukyanov K, Usman N, Lukyanov S. A ubiquitous family of putative gap junction molecules. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R473–R474. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00576-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan P. Innexins: members of an evolutionarily conserved family of gap-junction proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1711:225–245. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan P, Starich TA. Innexins get into the gap. Bioessays. 2001;23:388–396. doi: 10.1002/bies.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saier MH., Jr Computer-aided analyses of transport protein sequences: gleaning evidence concerning function, structure, biogenesis, and evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:71–93. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.71-93.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saier MH., Jr Answering fundamental questions in biology with bioinformatics. ASM News. 2003a;69:175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Saier MH., Jr Tracing pathways of transport protein evolution. Mol Microbiol. 2003b;48:1145–1156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saier MH, Jr, Tran CV, Barabote RD. TCDB: The transporter classification database for membrane transport protein analyses and information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D181–D186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj001. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasakura Y, Shoguchi E, Takatori N, Wada S, Meinertzhagen IA, Satou Y, Satoh N. A genomewide survey of developmentally relevant genes in Ciona intestinalis. X. Genes for cell junctions and extracellular matrix. Dev Genes Evol. 2003;213:303–313. doi: 10.1007/s00427-003-0320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobczak I, Lolkema JS. The 2-hydroxycarboxylate transporter family: physiology, structure, and mechanism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:665–695. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.665-695.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobczak I, Lolkema JS. Structural and mechanistic diversity of secondary transporters. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM. Claudins and epithelial paracellular transport. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:403–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.131404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y, Saier MH., Jr A web-based program for the prediction of average hydropathy, average amphipathicity and average similarity of multiply aligned homologous proteins. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;3:285–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y, Saier MH., Jr A simple sensitive program for detecting internal repeats in sets of multiply aligned homologous proteins. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;4:29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y, Tchieu J, Saier MH., Jr A web-based Tree View (TV) program for the visualization of phylogenetic trees. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;4:69–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]