Abstract

Background

In ESCAPE, there was no difference in days alive and out of the hospital for patients with decompensated heart failure (HF) randomly assigned to therapy guided by pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) plus clinical assessment versus clinical assessment alone. The external validity of these findings is debated.

Methods and Results

ESCAPE sites enrolled 439 patients receiving PAC without randomization in a prospective registry. Baseline characteristics, pertinent trial exclusion criteria, reasons for PAC use, hemodynamics, and complications were collected. Survival was determined from the National Death Index and the Alberta Registry. On average, registry patients had lower blood pressure, worse renal function, less neurohormonal antagonist therapy, and higher use of intravenous inotropes as compared with trial patients. Although clinical assessment anticipated less volume overload and greater hypoperfusion among the registry population, measured filling pressures were similarly elevated in the registry and trial, while measured perfusion was slightly higher among registry patients. Registry patients had longer hospitalization (13 vs. 6 days, p <0.001) and higher 6-month mortality (34% vs. 20%, p < 0.001) than trial patients.

Conclusions

The decision to use PAC without randomization identified a population with higher disease severity and risk of mortality. This prospective registry highlights the complex context of patient selection for randomized trials.

Keywords: tailored therapy, hemodynamic measurements, outcomes, generalizability, registry

INTRODUCTION

The pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) provides quantitative hemodynamic data, including pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and cardiac output, for which there are imperfect surrogates.1,2 Elective right heart catheterization in the catheterization laboratory (“in and out”) has an accepted role in selected patients to elucidate the causes of dyspnea, assess treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension, and evaluate patients for cardiac transplant.3,4 Historically, efforts to improve the congestive symptoms and clinical status of patients considered for cardiac transplantation led to a combined strategy of “tailored therapy,” in which an indwelling PAC was used to guide intravenous (IV) vasodilators and diuretics with monitored transition to a chronic oral regimen directed towards normalization of cardiac filling pressures and vascular resistance. Although these hemodynamic improvements may persist over time in association with improvements in exercise performance, congestive symptoms, and mitral regurgitation,5–8 more recent observational studies raised questions regarding the overall clinical benefits of PAC-guided therapy.9

To provide data on the impact of PAC-guided therapy in a contemporary patient population with advanced heart failure (HF), the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness (ESCAPE) was undertaken.10 The results of ESCAPE demonstrated more improvement of mitral regurgitation and ventricular filling patterns with less worsening of serum creatinine when therapy was guided by PAC, but there was no impact of PAC on the 6-month risk of death or hospitalization compared with patients managed with careful clinical assessment by experienced HF clinicians.11 Other randomized studies of PAC showed similar neutral results.12 The recent decline of indwelling PAC use during hospitalization in part reflects this lack of proven mortality benefit.13 Additionally, decreased use of tailored therapy parallels a declining need for aggressive titration of intravenous vasodilators to reduce vasoconstriction, likely due to long-term inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system prior to disease progression in the current era.

Since publication of the neutral ESCAPE trial results, clinicians have debated the generalizability of these results when providing care to decompensated HF patients who would have been excluded from the randomized study. The ESCAPE trial eligibility criteria were designed to exclude patients with mild decompensation, patients in whom the clinical assessment of hemodynamics was confusing, patients with severe decompensation for which escalating therapies might lead to crossover to hemodynamic monitoring, and patients with unrelated conditions that could affect endpoints. Additionally, as centers were selected for experience with hemodynamic intervention in HF, it was expected that some patients qualifying for the trial would instead receive PAC without randomization.

To depict the background PAC use against which the ESCAPE randomized results would be interpreted, the concomitant ESCAPE registry was established. We describe the characteristics of the ESCAPE registry population as well as selected outcomes from follow up. We then compare the registry to the trial population, with the ultimate goal of gaining insight into the external validity of the parent trial findings.

METHODS

The ESCAPE registry was conceived as part of the ESCAPE program, whose overall purpose was to evaluate the efficacy of PAC in patients hospitalized with advanced HF.10,11 The ESCAPE program recruited patients from 26 sites in the United States and Canada. Participating institutional review boards approved the randomized and registry protocols, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patients considered for the ESCAPE registry were ≥16 years of age, under the care of a HF specialist at an ESCAPE enrollment site, and received a PAC as part of their HF management strategy during hospitalization. HF patients receiving a PAC could be enrolled in the registry when they failed to meet study eligibility criteria or the investigator perceived that a PAC was necessary for management, either for diagnosis or treatment of hemodynamic derangements. Registry enrollment took place at 23 of the 26 sites, and not all patients receiving a PAC at enrolling sites were entered, due in part to the need for patient consent. Key exclusion criteria for the ESCAPE trial and other reasons for registry enrollment are listed in Table 1. In addition to listing relevant exclusion criteria, investigators were required to indicate other factors influencing the decision to proceed directly to a PAC rather than to randomize patients into the trial.

Table 1.

Main investigator-cited reasons registry patients were not enrolled in the ESCAPE trial, divided by rationale for the criteria.

| Reasons Not Enrolled | |

|---|---|

| Perceived to be too sick, % | 62 |

| PAC considered necessary for management by physician | 41 |

| Mechanical ventilation present or anticipated | 14 |

| Active transplant listing | 13 |

| Dopamine or dobutamine at >3 mcg/kg/min or at any rate for >24 hours | 10 |

| Instability likely to require PAC in next 24 hours | 8 |

| IABP or LVAD present or anticipated | 4 |

| Milrinone within last 48 hours | 4 |

| Unknown, % | 20 |

| PAC inserted before patient screened for ESCAPE | 7 |

| Need to define hemodynamics to establish diagnosis | 6 |

| Patient cannot return for follow-up | 5 |

| Current MI or ACS | 5 |

| MI or cardiac surgery within past 6 weeks | 4 |

| Creatinine >3.5 mg/dL | 3 |

| No physical findings of volume overload | 3 |

| Perceived to be too well, % | 19 |

| NYHA class <IV | 10 |

| No hospitalization for HF in the past year | 9 |

| LVEF >30% | 9 |

| History of HF <3 months | 3 |

| SBP >125 mm Hg | 1 |

Percentages represent the proportion of the total registry population for whom a variable was cited. Multiple individual exclusion criteria could be chosen for single patients; however, patients were assigned to perceived to be too sick, unknown, or perceived to be too well groups according to a fixed algorithm, such that no overlap occurred between these major 3 classifications. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ESCAPE, Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness; HF, heart failure; IABP, intraaortic balloon pump; JVD, jugular venous distention; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Patients were enrolled in the registry rather than randomized for disparate reasons: (1) patients were felt to be too sick for randomization, where withholding PAC placement was considered by the investigator to be suboptimal care and/or where crossover to a PAC was likely; (2) patients did not fulfill the trial definition for decompensated systolic HF or for chronicity of disease or disease therapy; (3) patients were felt to be potentially too well for randomization, where mandatory placement of an invasive catheter was considered inappropriate or diminished the potential to show treatment effect; (4) patients had concomitant complicating cardiac or non-cardiac medical conditions that altered the typical algorithm for PAC-guided HF therapy; and (5) patients were logistically inappropriate for randomization. Physicians recorded up to 5 criteria justifying placement of a PAC outside the trial and up to 3 specific trial exclusion criteria that were met.

To create more homogenous subgroups for statistical interpretation, we classified patients retrospectively for this analysis into 3 mutually exclusive categories using investigator cited reasons for failure to randomize (Table 1). First, subjects were labeled as “perceived to be too sick” if PAC was considered necessary by the investigator or if the following trial exclusion criteria were met: instability likely to require a PAC, significant dose of IV inotrope, active transplant listing, mechanical ventilation present or anticipated, or intraaortic balloon present or anticipated. Subjects were classified as “perceived to be too well” if the following trial exclusion criteria were present: New York Heart Association < class IV, no HF hospitalization in the last year, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) >0.30, HF diagnosis within 3 months, and systolic blood pressure >125 mm Hg. Subjects were labeled “unknown” if the following informative variables were present: PAC inserted prior to enrollment, recent acute myocardial infarction, creatinine >3.5 mg/dL, or failure to meet the criteria that would classify them as “perceived to be too well” or “too sick.” The overall registry and trial populations were also stratified by the use of IV inotropes at time of enrollment for additional subgroup analysis.

Baseline characteristics, laboratory values, and medication use were collected at the time of enrollment. Information obtained on registry patients after baseline was limited to initial PAC-derived hemodynamic measurements, PAC complications, and length of hospital stay. Vital status data were obtained from a search of the National Death Index for all patients and from a search of the Alberta Registry for patients enrolled at the Calgary site.14,15

Data were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables or percentages for categorical variables. Based on pre-defined goals of the registry, the comparison of 6-month survival between the registry and the trial population was considered the primary comparison of interest. Relative hospital length of stay and hemodynamic measures (post-capillary wedge pressure and cardiac index) were considered key secondary measures of interest. For comparisons across groups with more than 2 categories, we used non-ordered analysis with maximum degrees of freedom. Analyses were carried out using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient baseline characteristics

The registry included 439 patients from 23 sites in North America enrolled between November 2001 and April 2004. The frequencies of investigator-cited reasons for PAC insertion rather than randomization are shown (Table 1). More than half of the registry patients met specific exclusion criteria for the randomized trial. The majority of the remaining registry patients were not randomized due to investigator opinion that a PAC was necessary for management. From the investigator-cited reasons for trial exclusion, 62% of patients were retrospectively classified as “perceived to be too sick” for randomization, largely defined by investigator clinical assessment of disease severity, but also by >25% of patients in whom advanced life supportive therapies were required or expected (ie, inotropic infusion, mechanical ventilation, mechanical circulatory support, and active cardiac transplant listing). Only 7% of registry patients had a PAC placed prior to enrollment, and 2.7% ultimately did not undergo placement of a PAC during the index hospitalization.

The majority of baseline characteristics of the registry population were significantly different from those of the trial population (Table 2). On average, registry patients were older with worse renal function, and had more comorbid illness than their trial counterparts (Table 2 and Table 3). Patients enrolled in the registry, particularly those classified as “perceived to be too well,” had slightly higher LVEF compared with patients in the trial. However, the registry, like the trial, was dominated by patients with severe systolic dysfunction (Table 2). Although the “perceived to be too well” group had a higher serum sodium and lower blood urea nitrogen and creatinine than the “perceived to be too sick” cohort, a PAC was felt to be clinically indicated for the management of all registry patients, regardless of the trial exclusion criteria cited.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the ESCAPE registry and the ESCAPE trial at the time of study entry.

| Overall | Registry Subgroups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | ESCAPE Trial | PAC Registry | p | Perceived To Be Too Sick | Other | Perceived To Be Too Well | p |

| (N=433) | (N=439) | (N=270) | (N=86) | (N=83) | |||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56.1 (13.9) | 59.3 (14.4) | <0.001 | 59.1 (14.0) | 58.5 (14.5) | 60.8 (15.4) | 0.35 |

| Male, % | 74 | 69 | 0.10 | 70 | 69 | 68 | 0.97 |

| White, % | 60 | 81 | <0.001 | 81 | 90 | 74 | 0.024 |

| Comorbidities, % | |||||||

| Lung disease | 17 | 15 | 0.50 | 15 | 13 | 18 | 0.63 |

| Diabetes | 32 | 35 | 0.46 | 34 | 36 | 35 | 0.96 |

| Hypertension | 47 | 43 | 0.26 | 39 | 47 | 53 | 0.070 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 | 32 | <0.001 | 34 | 27 | 29 | 0.33 |

| Cardiac status | |||||||

| LEVF, median (IQR), % | 20 (15–25) | 20 (15–30) | <0.001 | 20 (15–30) | 20 (15–27) | 30 (19–35) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease, % | 54 | 43 | 0.001 | 41 | 44 | 47 | 0.57 |

| Transplant status, % | <0.001 | 0.022 | |||||

| Ineligible | 25 | 21 | 18 | 24 | 28 | ||

| Active evaluation | 32 | 35 | 36 | 32 | 38 | ||

| Listed | 43 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 1 | ||

| Medication use, % | |||||||

| ACE inhibitors | 79 | 46 | <0.001 | 44 | 37 | 59 | 0.013 |

| Beta-blockers | 62 | 54 | 0.016 | 52 | 57 | 58 | 0.52 |

| Loop diuretics | 98 | 80 | <0.001 | 81 | 84 | 71 | 0.094 |

| Nitrates, oral or topical | 40 | 21 | <0.001 | 22 | 16 | 22 | 0.47 |

| Vasodilators | 8 | 16 | 0.001 | 17 | 17 | 12 | 0.50 |

| Inotropes | 16 | 35 | <0.001 | 42 | 33 | 17 | <0.001 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ESCAPE, Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness; IQR, interquartile range; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Baseline physical examination and laboratory measures of patients in the ESCAPE registry and the ESCAPE trial at the time of study entry.

| Overall | Registry Subgroups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | ESCAPE Trial | PAC Registry | p | Perceived To Be Too Sick | Other | Perceived To Be Too Well | p |

| (N=433) | (N=439) | (N=270) | (N=86) | (N=83) | |||

| Physical exam | |||||||

| SBP, mm Hg | 104 (93–117) | 100 (90–114) | 0.008 | 99 (90–112) | 100 (90–117) | 105 (93–115) | 0.11 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 67 (60–74) | 60 (53–70) | <0.001 | 60 (53–70 | 60 (55–70) | 58 (50–64) | 0.017 |

| Pulse, bpm | 81 (70–92) | 80 (71–94) | 0.67 | 81 (71–94) | 78 (71–95) | 79 (72–92) | 0.42 |

| JVP, % | <0.001 | 0.26 | |||||

| <8 cm | 8 | 26 | 21 | 32 | 34 | ||

| 8–16 cm | 69 | 46 | 50 | 42 | 41 | ||

| >16 cm | 21 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 8 | ||

| Unable to measure | 2 | 18 | 19 | 13 | 17 | ||

| Rales, % | 52 | 53 | 0.89 | 53 | 57 | 50 | 0.23 |

| S3, % | 66 | 54 | 0.001 | 55 | 62 | 43 | 0.016 |

| Hepatomegaly, % | 58 | 22 | <0.001 | 30 | 14 | 11 | 0.004 |

| Hepatojugular reflux abnormal, % | 80 | 58 | <0.001 | 63 | 38 | 60 | <0.001 |

| Ascites, % | 38 | 11 | <0.001 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 0.021 |

| Peripheral edema 2+ or greater, % | 36 | 23 | <0.001 | 24 | 30 | 15 | 0.062 |

| Cool extremities, % | 17 | 28 | <0.001 | 24 | 29 | 39 | 0.10 |

| Laboratories | |||||||

| Sodium, mmol/L | 137 (135–140) | 136 (132–139) | <0.001 | 135 (132–138) | 137 (133–139) | 137 (132–140) | 0.20 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 1.6 (1.2–2.4) | <0.001 | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 1.6 (1.2–2.3) | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.23 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 29 (19–43) | 33 (20–55) | 0.005 | 36 (22–61) | 34 (22–53) | 22 (15–40) | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin total, mg/dL | 0.8 (0.4–1.2) | 0.8 (0.4–1.1) | 0.64 | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.6 (0.4–1.2) | 0.021 |

| SGOT (AST), mIU/dL | 29 (22–39) | 32 (24–87) | 0.001 | 34 (23–87) | 37 (24–115) | 29 (24–37) | 0.37 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 12.5 (11.4–13.7) | 11.8 (10.4–13.6) | <0.001 | 11.8 (10.4–13.5) | 11.7 (10.3–13.9) | 12.2 (10.7–13.7) | 0.64 |

All continuous measures presented as medians (interquartile ranges). BP, blood pressure; bpm, beats per minute; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ESCAPE, Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness; JVP, jugular venous pressure; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

HF medications at time of enrollment were notably different between patients in the registry and the trial (Table 2). Intravenous inotropic agent use in the registry was more than twice that observed in the trial and represented a primary determinant of the “perceived to be too sick” designation. As would be anticipated in HF patients with worse renal function, rates of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor use were lower and rates of alternative vasodilators were higher in the registry. The lower use of ACE inhibition was observed across all registry subgroups analyzed. Registry patients were less frequently treated with beta-blockers, presumably resulting from the concomitant use of inotropic therapy in some and a proximate diagnosis of HF in others. The use of beta-blockers was equivalent in the registry and trial among patients not treated with inotropic agents (63%). Although high in both groups, diuretic use was less in the registry patients, for whom filling pressures were on average clinically estimated to be lower, in whom creatinine was more frequently elevated, and for which a small subset of patients were acutely diagnosed with HF.

Clinically-estimated and PAC-measured hemodyamics

The majority of patients in both the registry and trial were estimated to have elevated filling pressures by physical examination (Table 3), which was one of the entry criteria for the randomized trial. Investigators estimated that 26% of registry patients and 8% of trial patients had normal jugular venous pressures (JVP). Another 18% of registry patients and 2% of trial patients had JVPs that were unable to be assessed. Within the registry population, patients felt to have an indeterminate JVP had an initial median right atrial pressure of 13 mm Hg (IQR 9.5–18.0), whereas those labeled as having JVP <8 cm H2O had a median right atrial pressure of 11 mm Hg (IQR 6–16). Detection of hepatomegaly, abnormal hepatojugular reflux, ascites, and peripheral edema was also lower in the registry group. Nonetheless, median right atrial pressures were 13 mm Hg in the registry compared with 12 mm Hg in the group randomized to PAC. Within the registry group, right atrial pressures were equally elevated (13 mm Hg) in the “perceived to be too sick” subgroup and “perceived to be too well” subgroup. The pulmonary capillary wedge pressure averaged 24 mm Hg in both the registry and the trial, and was slightly lower (22 mm Hg) in the “perceived to be too well” registry subgroup.

Average systolic blood pressure was lower in all 3 subgroups of registry patients compared with the trial patients. It is possible that knowledge of the low blood pressures led clinicians to diagnose cool extremities, which were more frequently reported in the registry group. However, the measured cardiac outputs, cardiac indices, and mixed venous oxygen saturations were actually the same or slightly higher at the time of initial hemodynamic measurement in the registry compared with the trial, even for the “perceived to be too sick” group.

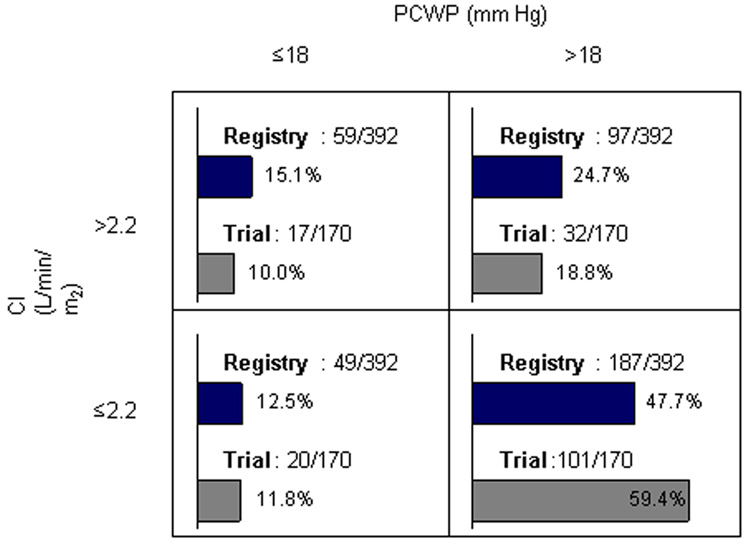

Overall hemodynamic measures were similar between the trial and registry (Table 4). Among the 155 registry patients receiving IV inotropic therapy at the time of enrollment, initial wedge pressure was identical to the overall group (median 24 mm Hg), and cardiac output was marginally higher (4.2 L/min, IQR 3.3–5.3) in comparison with the 284 registry patients not treated with inotropic therapy (4.0 L/min, IQR 3.1–5.2). When restricted to patients who were not on inotropic therapy at the time of study enrollment, measured hemodynamics remained similar between the registry and trial populations (non-inotrope registry patients n=284, median wedge pressure 24 mm Hg [IQR 18–29], cardiac index 2.0 L/min [1.6–2.6]; non-inotrope PAC-treated trial patients n=178, wedge pressure 25 mm Hg [19–30], cardiac index 2.0 L/min [1.6–2.6], comparison of wedge p = 0.14, comparison cardiac index p = 0.03). Division of study subjects into classic HF hemodynamic subgroups showed that about half of patients fit the description of low output with elevated left-sided filling pressures (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Hemodynamic measures of patients in the ESCAPE registry and the ESCAPE trial at the time of initial PAC placement.

| Overall | Registry Subgroups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | ESCAPE Trial | PAC Registry | p | Perceived To Be Too Sick | Other | Perceived To Be Too Well | p |

| (N=201) | (N=427) | (N=262) | (N=83) | (N=82) | |||

| RAP, mm Hg | 12 (8–18) | 13 (8–18) | 0.12 | 13 (8–18) | 14 (9–18) | 13 (8–17) | 0.45 |

| PASP, mm Hg | 55 (45–65) | 55 (44–65) | 0.75 | 53 (43–65) | 58 (46–66) | 56 (46–64) | 0.31 |

| PADP, mm Hg | 25 (20–35) | 27 (21–32) | 0.74 | 27 (20–32) | 28 (20–33) | 27 (21–32) | 0.38 |

| mPAP, mm Hg | 36 (30–44) | 36 (29–43) | 0.46 | 36 (30–43) | 38 (29–47) | 36 (29–42) | 0.45 |

| PCWP, mm Hg | 24 (19–30) | 24 (18–29) | 0.33 | 24 (18–30) | 25 (19–30) | 22 (15–28) | 0.16 |

| MVO2, % | 56 (43–65) | 61 (51–71) | 0.001 | 62.0 (51.7–71.0) | 57.9 (50.5–67.0) | 66.9 (56.5–76.3) | 0.12 |

| CO, L/min | 3.8 (2.9–4.6) | 4.1 (3.2–5.2) | 0.003 | 3.9 (3.2–5.2) | 4.4 (3.3–5.2) | 4.3 (3.1–5.4) | 0.53 |

| CI, L/min/m2 | 1.9 (1.6–2.3) | 2.1 (1.7–2.6) | 0.001 | 2.1 (1.6–2.5) | 2.2 (1.8–2.7) | 2.2 (1.7–2.8) | 0.17 |

| SVR, dynes/sec/cm2 | 1319 (994–1747) | 1187 (874–1667) | 0.026 | 1187 (864–1692) | 1133 (891–1732) | 1253 (962–1608) | 0.98 |

All measures presented as medians (interquartile ranges). CI, cardiac index; CO, cardiac output; ESCAPE, Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter; PADP, pulmonary artery diastolic pressure; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; RAP, right atrial pressure; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

Figure 1.

Classification of patients in the trial and the registry by PAC-derived hemodynamic measures.

Outcomes

During the placement and management of 427 PACs in the registry patients, only 12 patients had complications, the majority of which were infections. Complication rates were not statistically different than rates observed in the ESCAPE trial (trial 1.6%, registry 2.8%, p = 0.26).

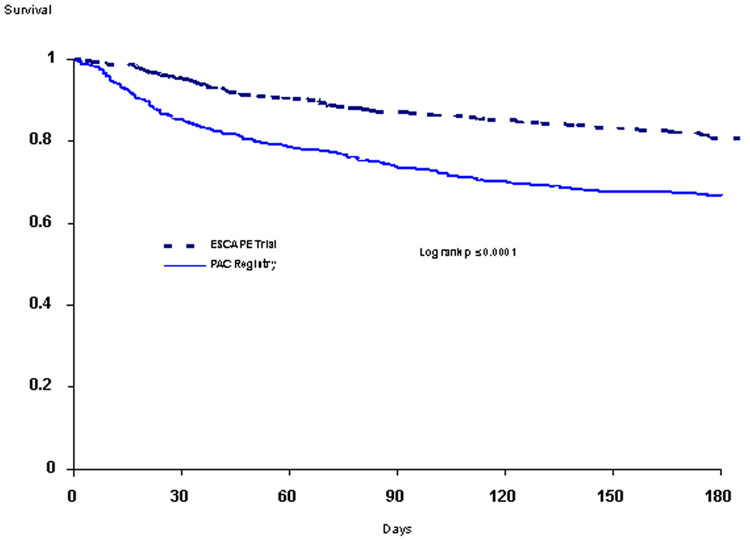

Length of initial hospital stay and 6-month mortality were markedly higher in the registry patients compared with trial patients (Table 5, Figure 2). Between the “too sick,” “unknown,” and “too well” subdivisions of the registry cohort, there was no significant difference in the hospital length of stay or survival. Clinical outcome measures appeared better for registry patients not treated with inotropes compared with the overall registry cohort (non-inotrope registry patients: median length of stay, 11 days; 6-month mortality, 26.4%), as has previously been shown for the ESCAPE cohort as well.16

Table 5.

Clinical outcomes of patients in the ESCAPE registry and the ESCAPE trial.

| Overall | Registry Subgroups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | ESCAPE Trial | PAC Registry | p | Perceived To Be Too Sick | Other | Perceived To Be Too Well | p |

| (N=433) | (N=439) | (N=270) | (N=86) | (N=83) | |||

| LOS, days | 6 (3–8) | 13 (7–26) | <0.001 | 14 (8–27) | 12 (5–22) | 11 (6–23) | 0.078 |

| 6-month mortality, % | 19.7 | 33.5 | <0.001 | 33 | 29 | 39 | 0.43 |

LOS given as median (interquartile range). ESCAPE, Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness; LOS, length of stay for index hospitalization; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for mortality in trial and registry cohorts out to 6 months.

DISCUSSION

The decision to use PAC without randomization identified a population with higher disease severity and almost twice the early mortality as the ESCAPE trial population. Among the registry patients, clinicians had more uncertainty regarding hemodynamic status, with underestimation of congestion and overestimation of hypoperfusion for those in whom clinical assessment was felt possible. Ultimately, measured hemodynamics in the registry were similar to those of randomized trial patients, demonstrating that factors beyond hemodynamics are critical in determination of short- and intermediate-term outcomes.

Selection of patients for randomization

Randomization can effectively balance known and unknown baseline characteristics between 2 groups, but does not necessarily select a representative sample of patients from the larger population considered for a therapy. The similarity of a randomized cohort to the overall population of interest depends on multiple factors, including the absolute risk of the underlying condition, the relative risks for each strategy being evaluated, and the availability of alternative approaches. Registries are capable of providing insight into how these factors may constrain trial enrollment and to what extent trial findings may be generalizable to the broader population.17–19 ESCAPE incorporated numerous eligibility criteria designed to establish an appropriate cohort for evaluating the efficacy and safety of PAC-guided therapy. The registry findings demonstrate that ESCAPE investigators generally excluded the sickest patients from the randomized trial, with the most frequently cited exclusion criteria related to high severity of illness.

There appear to be unique decisions involved in randomly assigning patients to an entirely diagnostic procedure, particularly one in which the risks are low. Based on the ESCAPE registry experience, it is likely that HF physicians are reluctant to submit to randomization the option of having objective data regarding cardiac performance, particularly when perceived disease severity or uncertainty triggers consideration of higher levels of diagnostic intervention. Investigator-perceived need for a PAC was associated with nearly twice the mortality of patients considered appropriate for randomization, regardless of the specific reasons cited for non-randomization. These marked outcome discrepancies suggest that ESCAPE investigators enrolled quite different patients into the randomized trial as compared with those relegated to the registry. An alternative explanation for the divergent outcomes is that registry patients were not so different at baseline but instead were placed at higher risk because of their enrollment in the registry with associated use of PAC-guided therapy. However, because of the markedly higher mortality among registry patients (all treated with PAC) compared with the subgroup of trial patients also treated with PAC, it seems unlikely that PAC placement or PAC-guided therapies drove the differential outcomes.

Impact of PAC on outcomes

The ESCAPE trial showed no impact of PACs on the primary outcome of days alive and out of the hospital at 6 months. This neutral effect of PACs was found despite improvements in surrogate endpoints that have been correlated with improved outcomes, including an early reduction in mitral regurgitation, a lower rate of worsening renal function, and improved quality of life. The lack of net benefit could not be attributed to complications of PACs, which were low in both the randomized cohort and the registry.

Whether patients with severe HF, like those included in this registry, preferentially derive clinical benefits from the use of PACs remains unknown because of the limitations inherent in registry design. Only randomization of PAC within this advanced HF population would adequately remove bias. Registry data collection was restricted to baseline measures, PAC-related complications, and index hospitalization length of stay, limiting the ability to assess what influence PACs had on therapy in the non-randomized patients. It is plausible that HF patients with varying disease states benefit differentially from PAC-guided therapy, and thus caution should be exercised in generalizing the ESCAPE trial findings to populations of patients unlike those represented in the trial. When filling pressures were monitored in a parallel trial conducted in the medical intensive care unit setting, the strategy to maintain lower filling pressures was associated with better outcomes.20 The registry confirms that many HF patients traditionally considered for a PAC were not well represented in the trial. On the other hand, we were unable to demonstrate significant differences in initial hemodynamics among patients in either the trial or the registry. Because decisions with PAC-guided therapy are at least in part based on direct hemodynamic measures, management decisions guided by a PAC may not have been markedly different between the registry and the PAC-treated arm of the trial. A number of other large, randomized, controlled trials of PAC-guided therapy in a variety of critically ill patient populations have shown similarly neutral results.12

Clinical assessment and measurement of hemodynamics

Clinicians’ estimation of filling pressures based on bedside evaluation suggested a lesser degree of congestion in the registry patients as compared with the trial population. Contrary to this clinical assessment, the measured filling pressures in the registry were similar to those observed in the randomized population. These hemodynamic similarities held true across various registry subgroups. Previous analysis of patients randomized into the ESCAPE trial demonstrated accurate investigator estimation of right atrial pressure.21 In contrast to the trial experience, registry enrollment was often driven by investigator-perceived need to clarify hemodynamic status for diagnosis and guidance of management. Uncertainty surrounding assessment was more prevalent in the registry, as investigators were “unable to measure” the JVP in 18% versus 2% of patients in the trial population.

Physical signs of peripheral hypoperfusion were more frequently ascribed to registry patients as compared with trial patients. Greater prevalence of hypotension may have contributed to investigator perception of cool extremities in the registry group. These noninvasive assessments were ultimately found to be discordant with PAC-measured perfusion, as the cardiac output was as high or higher and the systemic vascular resistance lower in the registry cohort. It is possible, that the use of intravenous inotropic therapy might have been even higher in the registry group if guided by the clinician’s impression of hypoperfusion rather than by the measured hemodynamics.

Limitations of the registry

The registry did not capture all HF patients receiving PAC-guided therapy at participating centers, due to limitations of resources for obtaining and analyzing this information. It is not known to what extent patients enrolled in the overall ESCAPE program represent the other patients receiving a PAC during this period. For registry patients, there was no monitoring of the quality of data collection.

The small number of registry patients who had a PAC in place prior to recording baseline medications and physical examination may have biased comparisons between trial and registry populations. However, removal of these patients from the analysis did not significantly alter the findings.

Collection of medication use beyond the initial assessment was not possible for registry patients. Consequently, it is not possible to determine the impact of hemodynamic information on the use of selected medical therapies or to compare ongoing treatment decisions between the registry and trial populations. While vasodilator therapy was significantly higher in the registry than trial patients at enrollment (16% vs. 8%), IV vasodilator use rose significantly in the trial patients after randomization (37% for the PAC arm, 19% for the clinical assessment arm). We do not know whether similar alterations occurred in the registry.

Implications

The use of a PAC in HF and other settings has declined substantially since concerns were initially raised by the SUPPORT study.9,13 Registry patients for whom a PAC was considered outside of ESCAPE trial randomization had evidence of more severe compromise and a dismal 6-month survival. In practice, as reflected by the registry, HF specialists rarely employed a PAC to guide therapy in low-risk patients. Even in registry patients “perceived to be too healthy” by exclusion criteria, outcomes were poor, indicating that investigators reserved PACs for those patients at highest risk of adverse outcomes even in the presence of isolated traditional markers of better prognosis. The accurate clinical intuition demonstrated by the ESCAPE investigators was also shown by the ESCAPE research nurses, whose estimation of likelihood of endpoints added independent prognostic information.22

The increased risk for adverse outcomes among ESCAPE registry patients was not reflected in the measured hemodynamics. Whether due to or despite the use of PAC-derived information, the therapy provided to the registry patients during hospitalization was not sufficient to prevent an overall outcome worse than that of patients randomized in the trial. The perceived need for hemodynamic measurement itself identified a high-risk population for whom further emphasis should have focused on therapies beyond those acutely guided by hemodynamics. Until we better understand this group of patients perceived to need a PAC to manage decompensation, these high-risk patients should generally receive careful re-evaluation and consideration for advanced intervention, including cardiac replacement or mechanical circulatory support. However, for most of these patients, as represented by the large registries of patients hospitalized with HF,23 the primary option will be an intensification of outpatient surveillance and intervention after discharge, as part of effective HF management.

Acknowledgements

The overall ESCAPE program was primarily funded by the NHLBI. The ESCAPE registry was in part funded by and unrestricted grant from Edwards LifeSciences.

The ESCAPE registry was funded in part by an unrestricted grant from Edwards LifeSciences.

The ESCAPE trial and overall program were primarily supported by contract N01-HV-98177 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Complete list of investigator-cited reasons for ESCAPE registry enrollment. Investigators were asked to select all of the 5 main criteria that applied, and up to 3 trial entry criteria that were not met (under #1).

| 1. | Did not meet entry criteria for ESCAPE trial | 52.4% | |

| • | Mechanical ventilation present or anticipated | 13.7% | |

| • | Active transplant listing | 13.2% | |

| • | Dopamine or dobutamine infusion at a rate of >3 mcg/kg/min or at any rate for >24 hours | 10.0% | |

| • | NYHA <Class IV | 9.6% | |

| • | No hospitalization for HF in the past year | 8.9% | |

| • | LVEF >30% | 8.9% | |

| • | Instability likely to require PAC in next 24 hours | 8.4% | |

| • | Need to define hemodynamics to establish diagnosis of HF versus other condition | 6.4% | |

| • | Current MI or ACS | 5.0% | |

| • | Patient cannot return for follow-up | 4.8% | |

| • | Milrinone in the past 48 hours | 4.1% | |

| • | IABP or LVAD present or anticipated | 4.1% | |

| • | MI or cardiac surgery within past 6 weeks | 3.7% | |

| • | Creatinine >3.5 mg/dL | 3.2% | |

| • | History of HF <3 months | 3.2% | |

| • | No physical findings (JVD >10 cm above RA; square-wave valsalva response; hepatomegaly, ascites, or edema in absence of other obvious causes; rales >1/3 lung fields) | 2.5% | |

| • | No symptoms of elevated filling pressure (dyspnea at rest, abdominal discomfort, severe anorexia, nausea from hepatosplanchnic congestion) | 2.1% | |

| • | Planned coronary revascularization | 1.8% | |

| • | No ACEI or diuretics attempted with past 3 months | 1.6% | |

| • | Moderate to severe aortic or mitral stenosis | 1.6% | |

| • | SBP >125 mm Hg | 1.4% | |

| • | WBC >13,000 | 0.7% | |

| • | HF due to specific treatable cause (severe anemia, hypothyroidism, systemic infection) | 0.2% | |

| • | Temperature >37.8°C | 0.7% | |

| • | Unable to place PAC within next 12 hours | 0.5% | |

| • | Life expectancy <1 year | 0.5% | |

| • | Primary pulmonary hypertension | 0.7% | |

| • | Pulmonary infarct within last month | 0.2% | |

| • | Childbearing potential without accepted birth control | 0.2% | |

| • | Less than 16 years of age | 0.2% | |

| 2. | PAC considered necessary for management by physician | 40.5% | |

| 3. | PAC inserted before patient screened for ESCAPE | 7.1% | |

| 4. | Physician preferred not to randomize | 3.9% | |

| 5. | Patient refused randomization | 0.5% | |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Eisenberg PR, Jaffe AS, Schuster DP. Clinical evaluation compared to pulmonary artery catheterization in the hemodynamic assessment of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1984;12:549–553. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198407000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swan HJ, Ganz W, Forrester J, Marcus H, Diamond G, Chonette D. Catheterization of the heart in man with use of a flow-directed balloon-tipped catheter. N Engl J Med. 1970;283:447–451. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197008272830902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt SA. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:e1–e82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaroff JG, Rosengard BR, Armstrong WF, Babcock WD, D'Alessandro A, Dec GW, et al. Consensus conference report: maximizing use of organs recovered from the cadaver donor: cardiac recommendations March 28–29, 2001, Crystal City, Va. Circulation. 2002;106:836–841. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025587.40373.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevenson LW, Tillisch JH. Maintenance of cardiac output with normal filling pressures in patients with dilated heart failure. Circulation. 1986;74:1303–1308. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.6.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevenson LW, Sietsema K, Tillisch JH, Lem V, Walden J, Kobashigawa JA, et al. Exercise capacity for survivors of cardiac transplantation or sustained medical therapy for stable heart failure. Circulation. 1990;81:78–85. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson LW, Brunken RC, Belil D, Grover-McKay M, Schwaiger M, Schelbert HR, et al. Afterload reduction with vasodilators and diuretics decreases mitral regurgitation during upright exercise in advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:174–180. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90196-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steimle AE, Stevenson LW, Chelimsky-Fallick C, Fonarow GC, Hamilton MA, Moriguchi JD, et al. Sustained hemodynamic efficacy of therapy tailored to reduce filling pressures in survivors with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 1997;96:1165–1172. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.4.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connors AF, Jr, Speroff T, Dawson NV, Thomas C, Harrell FE, Jr, Wagner D, et al. The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. SUPPORT Investigators. JAMA. 1996;276:889–897. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.11.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah MR, O'Connor CM, Sopko G, Hasselblad V, Califf RM, Stevenson LW. Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness (ESCAPE): design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2001;141:528–535. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.113995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Escape Investigators and Escape Study Coordinators. Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness: the ESCAPE trial. JAMA. 2005;294:1625–1633. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.13.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah MR, Hasselblad V, Stevenson LW, Binanay C, O'Connor CM, Sopko G, et al. Impact of the pulmonary artery catheter in critically ill patients: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2005;294:1664–1670. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.13.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiener RS, Welch HG. Trends in the use of the pulmonary artery catheter in the United States, 1993–2004. JAMA. 2007;298:423–429. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [Accessed January 23];National Death Index, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control. 2007 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ndi.htm.

- 15.National Death Index User's Manual. Hyattsville, MD: Department of Vital Statistics, Centers for Disease Control; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elkayam U, Tasissa G, Binanay C, Stevenson LW, Gheorghiade M, Warnica JW, et al. Use and impact of inotropes and vasodilator therapy in hospitalized patients with severe heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;153:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy JW, Kaiser GC, Fisher LD, Fritz JK, Myers W, Mudd JG, et al. Clinical and angiographic predictors of operative mortality from the collaborative study in coronary artery surgery (CASS) Circulation. 1981;63:793–802. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feit F, Brooks MM, Sopko G, Keller NM, Rosen A, Krone R, et al. Long-term clinical outcome in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation Registry: comparison with the randomized trial. BARI Investigators. Circulation. 2000;101:2795–2802. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.24.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hochman JS, Buller CE, Sleeper LA, Boland J, Dzavik V, Sanborn TA, et al. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction--etiologies, management and outcome: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shocK? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00879-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, deBoisblanc B, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2564–2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drazner M, Yancy C, Shah M, Nohria A, Leier C, Miller L, et al. Utility of the history and physical examination in assessing hemodynamics in patients with advanced heart failure: The ESCAPE trial. Circulation. 2005;112:640. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamokoski LM, Hasselblad V, Moser DK, Binanay C, Conway GA, Glotzer JM, et al. Prediction of rehospitalization and death in severe heart failure by physicians and nurses of the ESCAPE trial. J Card Fail. 2007;13:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abraham WT, Adams KF, Fonarow GC, Costanzo MR, Berkowitz RL, LeJemtel TH, et al. In-hospital mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure requiring intravenous vasoactive medications: an analysis from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]