Abstract

Background

Total joint arthroplasty is a highly efficacious and cost-effective procedure for moderate to severe arthritis in the hip and knee. Although patient characteristics are considered to be important determinants of who receives total joint arthroplasty, no systematic review has addressed how they affect the outcomes of total joint arthroplasty. This study addresses how patient characteristics influence the outcomes of hip and knee arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis.

Methods

We searched 4 bibliographic databases (MEDLINE 1980–2001, CINAHL 1982–2001, EMBASE 1980–2001, HealthStar 1998–1999) for studies involving more than 500 patients with osteoarthritis and 1 or more of the following outcomes after total joint arthroplasty: pain, physical function, postoperative complications (short-and long-term) and time to revision. Prognostic patient characteristics of interest included age, sex, race, body weight, socioeconomic status and work status.

Results

Sixty-four of 14 276 studies were eligible for inclusion and had extractable data. Younger age (variably defined) and male sex increased the risk of revision 3-fold to 5-fold for hip and knee arthroplasty. The influence of weight on the risk of revision was contradictory. Mortality was greatest in the oldest age group and among men. Function for older patients was worse after hip arthroplasty (particularly in women). Function after knee arthroplasty was worse for obese patients.

Conclusion

Although further research is required, our findings suggest that, after total joint arthroplasty, younger age and male sex are associated with increased risk of revision, older age and male sex are associated with increased risk of mortality, older age is related to worse function (particularly among women), and age and sex do not influence the outcome of pain. Despite these findings, all subgroups derived benefit from total joint arthroplasty, suggesting that surgeons should not restrict access to these procedures based on patient characteristics. In addition, future research needs to provide standardized measures of outcomes.

Abstract

Contexte

L'arthroplastie totale est une intervention très efficace et rentable pour soulager l'arthrite modérée ou grave à la hanche ou au genou. Bien que les caractéristiques du patient soient considérées comme des facteurs importants pour choisir les récipiendaires d'une arthroplastie totale, aucune synthèse systématique ne fait état de leur incidence sur les résultats. La présente étude traite de l'incidence des caractéristiques des patients atteints d'arthrose sur les résultats d'une arthroplastie de la hanche ou du genou.

Méthodes

Nous avons consulté 4 bases de données bibliographiques (MEDLINE 1980–2001, CINAHL 1982–2001, EMBASE 1980–2001 et HealthStar 1998–1999) pour trouver des études sur plus de 500 patients atteints d'arthrose et ayant présenté un ou plusieurs des résultats suivants après une arthroplastie totale : douleur, fonction physique, complications postopératoires (à court et à long terme) et attente d'une révision. Les caractéristiques pronostiques retenues comprenaient l'âge, le sexe, la race, le poids corporel, la situation socioéconomique et l'état relatif à l'emploi.

Résultats

Des 14 276 études, 64 pouvaient être incluses et contenaient des données extractibles. On a constaté un risque de révision de 3 à 5 fois plus élevé pour les arthroplasties de la hanche ou du genou réalisées dans les groupes plus jeunes (définis de façon variable) et chez les hommes. L'influence du poids sur le risque de révision s'est révélée contradictoire. La mortalité était plus élevée dans les groupes plus âgés et chez les hommes. La fonction physique s'était détériorée chez les patients plus âgés après une arthroplastie de la hanche (plus particulièrement chez les femmes), ainsi que chez les patients obèses après une arthroplastie du genou.

Conclusion

Bien qu'une recherche plus approfondie s'impose, nos conclusions indiquent que, après une arthroplastie totale, le risque de révision augmente dans les groupes plus jeunes et chez les hommes, alors que le risque de mortalité s'accroît dans les groupes plus âgés et chez les hommes. De plus, une détérioration de la fonction a été observée dans les groupes plus âgés (plus particulièrement chez les femmes), mais l'âge et le sexe ne semblent pas influer sur la douleur. Malgré ces conclusions, tous les sous-groupes ont tiré profit d'une arthroplastie totale, ce qui incite à penser que les chirurgiens ne devraient pas restreindre l'accès à cette intervention en fonction des caractéristiques des patients. Il importera cependant que la recherche future fournisse des mesures normalisées des résultats.

Total joint arthroplasty of the hip and knee result in substantive and sustained improvement in quality of life for individuals with moderate to severe osteoarthritis.1,2 Total joint arthroplasty is highly cost-effective and may even be cost-saving in the management of disability related to arthritis.3 However, previous population-based research has shown that many patients who are appropriate for, and willing to consider, total joint arthroplasty have not had the procedure.4 Although physicians agree about the value of arthroplasty, they show little agreement on how patient characteristics affect their decisions to perform or refer patients for total joint arthroplasty.5,6 This variation in opinion has been linked to area variation in care delivery.7

Young and colleagues8 reported that the best functional outcomes and prosthesis survival rates after hip arthroplasty were reported among patients between 45 and 75 years of age who weighed less than 70 kg, and had strong social support, a higher level of education, better preoperative functional status and no comorbid diseases. However, this was not a systematic review. Callahan and colleagues9,10 performed a review of the outcomes of total knee arthroplasty but did not identify the effect of patient characteristics on outcomes. Thus a systematic review of the literature evaluating the effect of patient characteristics on the outcomes of joint arthroplasty is lacking.

The purpose of our systematic review was to determine how patient characteristics affect the outcomes of hip and knee arthroplasty. Establishing how patient characteristics influence the outcome of total joint arthroplasty would assist in patient selection and provide patients with better information about the risks and benefits of the procedure. An evidence-based systematic review of the literature has the potential to improve consensus among physicians and patients and thereby improve access and quality of care.11

Methods

Search strategy

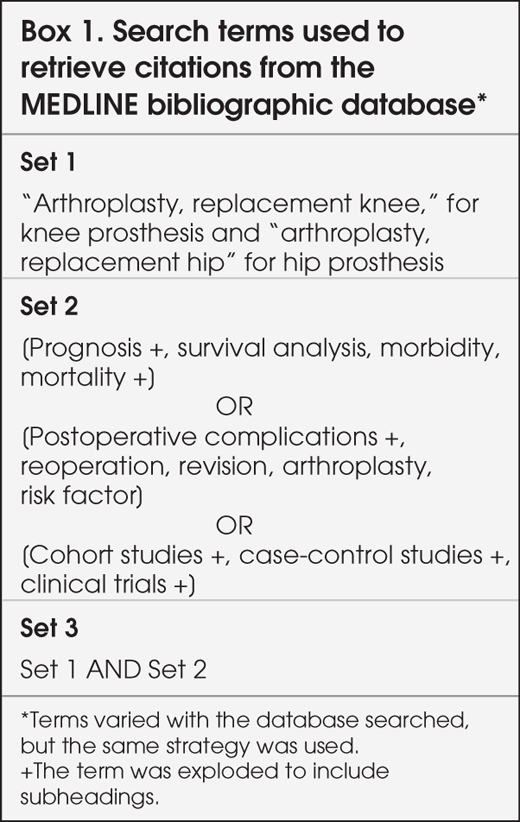

We searched 4 bibliographic databases (MEDLINE 1980–2001, EMBASE 1980–2001, CINAHL 1982–2001 and HealthStar 1998–1999). We selected the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords detailed in Box 1 with the assistance of an experienced research librarian.12

Box 1.

Study selection

We imported all citations into a bibliographic management program (Reference Manager 9.5, RSI Research Software Inc.). We used a modified approach based on the Cochrane Reviewers Handbook13 to systematically select citations in 2 stages: identification and selection. Raters were not blinded to citation identifiers (e.g., author, institution, year of publication) because unblinding has been shown to have minimal potential for selection bias.14 Two pairs of trained raters evaluated all English-language citations, and a single native speaker evaluated all non-English citations.

Eligibility criteria

In the identification phase, we reviewed abstracts to identify studies with sample sizes of 500 or more; we chose this sample size to have sufficient statistical power to evaluate the effect of multiple factors on rare outcomes of total joint arthroplasty such as death or revision. We identified citations in 19 languages other than English. We decided a priori not to review studies that constituted less than 10% of the total number of non-English citations retrieved. Of the 441 non-English studies that we reviewed, those in French (26.1%), German (22.5%), Scandinavian (14.1%, Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish) and Italian (10.0%) accounted for 73%.

In the selection phase, we evaluated the full text of all studies with 500 or more participants against the eligibility criteria outlined in Box 2. We considered only patients with osteoarthritis because most patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty have this diagnosis. We evaluated the following outcomes of total joint arthroplasty: function, pain, revision, mortality and complications. We defined revision as surgery that necessitated the replacement of any component except later resurfacing of the patellas in knee arthroplasty. The study also had to be adjusted or stratified for 1 or more of the following prognostic factors: age, sex, race, anthropometry (body mass index, height, weight), socioeconomic status, work status and high physical demands in relation to one of the outcomes of interest.

Box 2.

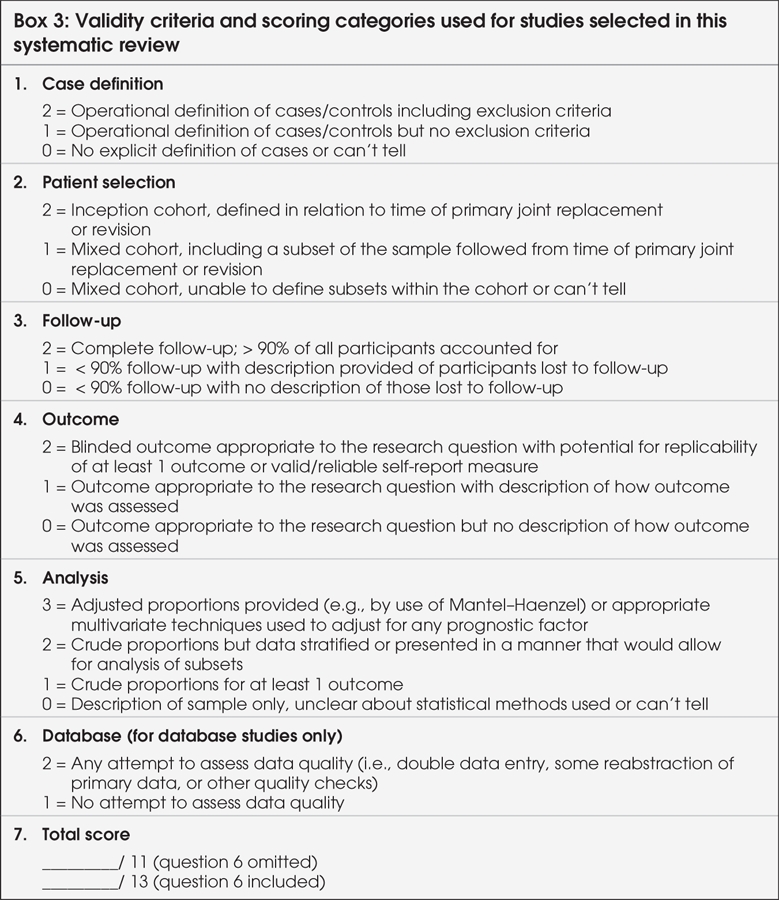

Validity assessment

We evaluated study validity using published validity criteria,15 which we modified in 2 ways: we assessed the adequacy of follow-up, not simply the duration, and we added a criterion related to data quality for database studies (Box 3).

Box 3.

Results

General study characteristics

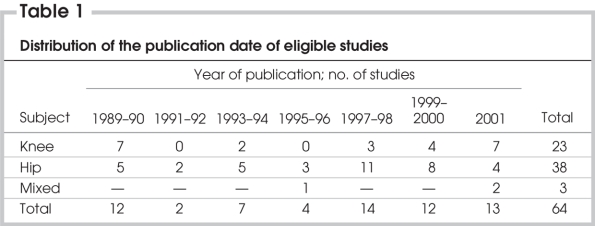

Our search returned 14 276 citations, of which 3211 met the eligibility criteria for the identification phase. Of the 3211 studies, 87 met the eligibility criteria in the selection phase, and 64 had data that could be extracted and were subsequently evaluated for study validity. Table 1 details the years of publication for the abstracted studies. Of the 64 studies, 23 focussed on knee arthroplasty, 38 focussed on hip arthroplasty and 3 studies evaluated both procedures. The year of publication ranged from 1989 to 2002; 60% of eligible studies were published between 1997 and 2001. Some studies were based on data from arthroplasty registries (n = 19), administrative (e.g., Medicare) or state-discharge databases (n = 4) or large urban hospitals (n = 4).

Table 1

Six of the 64 studies were prospective (including 1 multicentre randomized trial); the rest were retrospective. The duration of follow-up ranged from 7 days to 10 years postoperatively for knee arthroplasty and from 6 weeks to 20 years postoperatively for hip arthroplasty. Sample sizes varied from 657 to more than 20 000 patients for knee arthroplasty and from 555 to 96 675 patients for hip arthroplasty. Although most studies collected multiple outcomes across different domains, typically only 1 outcome was presented in a stratified form with respect to one of the identified prognostic factors of interest.

For clarity, we grouped results according to the 5 main outcomes of interest: revision, mortality, function, pain and postoperative complications. The inconsistency of reporting methods and lack of independence among the studies (from the same total joint arthroplasty registries) precluded combination of results from multiple studies.

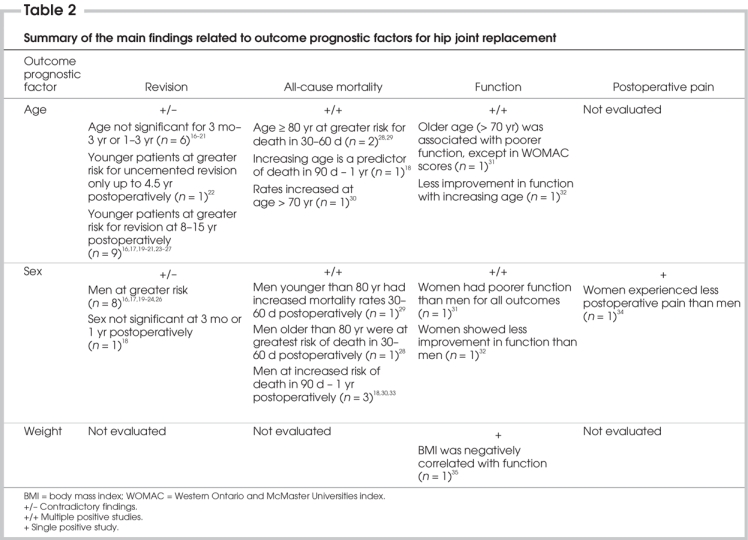

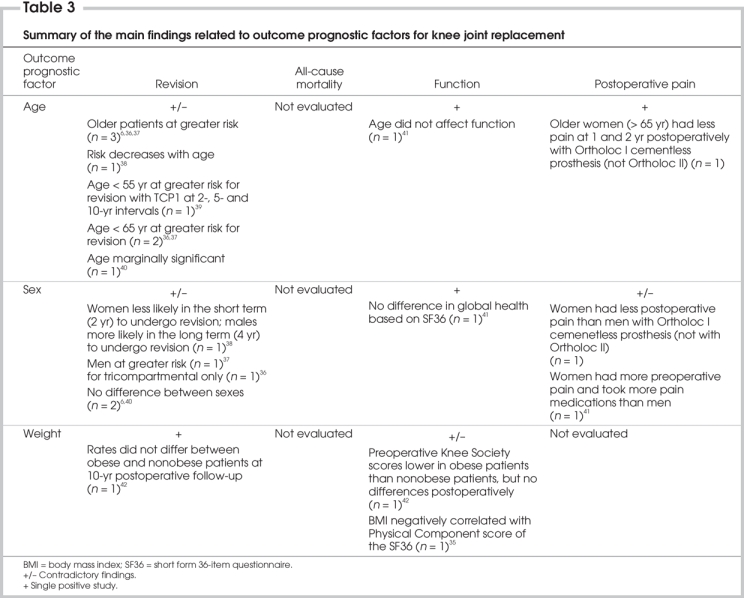

Revision

Revision (all causes) was reported in 28 studies and of these, 22 (14 hip and 8 knee) reported data stratified by age, sex and obesity (Table 2 and Table 3). All Swedish registry studies and 2 other studies (1 each from the Norwegian registry and an urban US hospital) reported revision due to aseptic loosening of the hip; the remaining Norwegian studies and 1 US study considered all causes for revision as the primary outcome. For knee arthroplasty, revision was reported as all causes.

Table 2

Table 3

For hip arthroplasty, age and sex were the most consistently evaluated prognostic factors (Table 2). Although the classification of younger and older patients varied across studies, when age was shown to be a significant factor, younger patients were consistently shown to be at greater risk for revision at intervals ranging from 2 to 20 years postoperatively. The influence of age on hip revision varied as a result of the femoral and acetabular components. For the acetabular component, Havelin and colleagues23 found that the middle age group (70–79 yr) had the highest failure rate ratio; it was 4.5 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.9–33.5) times greater than that of the oldest age group (> 79 yr). The failure rate ratio for the femoral component for the oldest age group was 2.1 (95% CI 0.9–4.5). We were not able to compare other age groups directly, but our results suggest lower rates of failure for the femoral component in all age categories (see Appendix 1, available online at www.cma.ca/cjs). However, Johnsson and colleagues24 reported no difference between acetabular and femoral component survival (Appendix 1). Men were generally found to be at greatest risk of revision in 9 of 10 studies, ranging from a 3-fold to 5-fold increase. In particular, younger men had the greatest risk for revision.

For knee arthroplasty, the definition of younger and older patients again varied. In most studies, younger age was associated with greater risk for revision ranging from 2 to 10 years postoperatively (Table 3). However, Scuderi and colleagues39 showed that this age trend reversed for 1 of the 3 types of prostheses that they compared; for patients having the total condylar prosthesis with metal backing (TCPM), there was a slight increase in the risk of revision for older patients. One study showed that age influenced the 10-year survival36 for tricompartmental replacements only. The magnitude of the influence of age for revision was estimated with an odds ratio of 0.8238 to a risk ratio of 0.97.43 Male sex was associated with an 8%–23% higher risk of knee revision38,39,43 (Table 3).

For the knee, Spicer and colleagues42 reported that obesity was not a significant prognostic factor for all-cause revision because the survival rates did not significantly differ from those in the nonobese group (Table 3). However, Scuderi and colleagues39 reported that patients at less than 110% of ideal body weight had a slightly increased risk of revision at the 10-year survival interval for both the total condylar prosthesis (TCP1) and total condylar prosthesis with polyethylene backing (TCPP). For the TCPM type, patients at more than 110% of their ideal body weight had a slightly increased risk for revision.

Mortality

Of the 16 studies in which mortality was evaluated, 5 had extractable data. Mortality intervals reported for hip arthroplasty were 30 days, 60 days, 90 days and 1 year (Table 2). Older age at the time of surgery was associated with increased postoperative mortality. Male sex was also associated with higher mortality rates in all but 1 study. No study provided information on predictors of mortality after knee arthroplasty.

Functional outcomes

Of the 17 studies that reported functional outcomes, data was extractable for only 7 studies (Table 2 and Table 3). For hip arthroplasty, older individuals and women had poorer function and less improvement relative to baseline function.

For knee arthroplasty, 1 study reported that age was not a predictor of postoperative function, as determined by Western Ontario and McMaster Universities index (WOMAC) scores.31 Sex did not affect function. Stickles and colleagues35 found that higher body mass index was associated with difficulty ascending and descending stairs postoperatively.

Postoperative pain

Although pain relief is a primary reason for undergoing arthroplasty, this outcome was seldom reported separately. Visuri and colleagues34 reported that women experienced less postoperative pain than men after total hip arthroplasty. Whiteside44 reported that, among patients having knee arthroplasty, older women (> 65 yr) fared best with respect to being pain free at both 1 and 2 years postoperatively. In contrast, Hawker and colleagues41 found that women reported more pain and took more pain medications than men after knee arthroplasty.

Satisfaction

Stickles and colleagues35 found that satisfaction did not differ for obese patients after both hip and knee arthroplasty. Similarly, Esephaug and colleagues32 found that age and sex did not affect the satisfaction level of patients undergoing primary hip arthroplasty. However, women and older patients undergoing revision were reported to be less satisfied.32 Hawker and colleagues41 found that greater body mass at 2–7 years after knee arthroplasty was associated with a lower level of satisfaction among patients who had knee arthroplasty.

Arthroplasty complications

We encountered 2 barriers when we attempted to evaluate the influence of prognostic factors on risk for postoperative complications. First, complications tended to be reported as frequencies and were not stratified with respect to the prognostic factors of interest. Second, the exact nature of the complication often could not be adequately determined. For example, we defined a deep infection as one that involved the prosthesis and where the management of the complication necessitated surgical intervention (excluding those infections treated with oral antibiotics alone). However, numerous studies defined infection only in the most general sense, and few studies identified the manner in which infections were managed. For these reasons, no conclusive results can be reported with respect to the influence of prognostic factors on postoperative and arthroplasty complications.

Discussion

Treatment is proposed for patients based on the assumption that patients will, on balance, have more benefit than harm. Prognostic factors influence the probability of response, remission, recurrence and duration of disease under clinical care.15 Determining prognostic factors that affect treatment effectiveness is essential to clinicians and important to patients in their decision-making. Physicians report that patient characteristics do affect their decisions either to refer patients for or recommend knee arthroplasty; yet, how patient characteristics influence their recommendations varies substantially.5,7 Despite variation in physician opinion, our systematic review found little consistent evidence on the nature and magnitude of the influence of patient characteristics on the outcomes of pain, revision, function and mortality after total joint arthroplasty. Furthermore, even if certain subgroups fare less well after total joint arthroplasty, this does not mean that, on average, these patients did not receive benefit from the procedure. The major finding of our review suggests that, despite the impressions of referring physicians and surgeons,5,7 patients should in general not be restricted access to total joint arthroplasty based on their characteristics.

On the other hand, decision-making requires discussion of the risks and benefits of treatment tailored to the patient and his or her circumstances. The results of this study suggest that certain factors, even in the context of low risk and overall improvement in quality of life, do affect outcome. Older patients, particularly men, need to know that, although the absolute differences are small, their risks of revision and mortality for both hip and knee arthroplasty are higher. Although they vary by study, most results seem to suggest higher revision rates for both femoral and acetabular components. Older age was also associated with poorer functional outcome relative to younger patients. The exact age at which this relative decrease in improvement occurs was not adequately described, because the ages described as “younger” ranged from younger than 50 to younger than 75. Furthermore, and more importantly, functional improvement relative to baseline occurred in all age groups. Thus although older patients may realize less benefit compared with younger patients, they are still candidates for arthroplasty and can expect, on average, an improvement in quality of life. Women who had hip arthroplasty had worse functional outcomes. However, this may have been due to their surgeries occuring at a more advanced stage of disease. Although lower function and satisfaction scores were reported among obese patients, obesity, which is generally assumed to adversely affect prosthesis longevity, did not increase revision rates in these studies. These findings are important in view of the many appropriate candidates who consider themselves to be “too old, too fat or too sick” for the procedure.

There is increasing recognition that the systematic reviews of clinical studies evaluating prognosis are not as straightforward as randomized controlled trials.45 Nevertheless, great strides in the methodologies for evaluating quality and combining data from prognostic studies have been developed.45 Numerous factors, however, prevented us from summarizing studies in order to provide aggregated point estimates. These issues would likely be relevant to prognostic studies of most surgical conditions and therapies. First, many studies were derived from the same national registries (e.g., several studies used data from overlapping years), and thus we were unable to combine results among studies. Second, there was inconsistency with respect to the definition of various prognostic factors and outcomes. For example, the categorization of young or old varied by up to 20 years and on several occasions varied within studies based on the same registry data.16,17 Third, we observed that most studies assumed a linear relation between prognostic factor and patient outcome because regression analyses were almost always used. However, not all relations may be linear. Fourth, many studies did not take into account all important variables such as the extent of obesity, work status, physical activity, preoperative function or health status. Fifth, studies lacked consistent definition of key outcomes such as “joint failure” and the definition and verification of important postoperative adverse events or arthroplasty complications. Sixth, there are no subject terms specifically available to capture “prognosis” studies. The MeSH terms are imprecise in those bibliographic databases that use them (MEDLINE, CINAHL), but subject terms are very broad in EMBASE, which does not use MeSH terms. Finally, many of the studies identified in this systematic review were based on databases and registry data. These studies seldom reported the methods employed to minimize entry of false or incorrect data. Only a few studies reported use of double data entry, retrospective audits of hospital medical files or comparison to a national discharge registry. More often, we observed that there was discussion of the software and training of the entry personnel but not necessarily quality checks for the data collection.

Recognizing the limitations of prior research, an important question is whether future meta-analyses should or should not use the older studies such as those identified in this article. The updating of systematic reviews does not always add to the precision of pooled estimates or change the clinical interpretation.46,47 For example, some areas of research are more prolific than others, and thus time alone would not be sufficient criteria for updating a review.48 The quality of the literature is an important factor to consider. A review by Kane and colleagues49 did not find age, sex and obesity to be significantly correlated with knee arthroplasty outcomes; they too noted that few studies used any analysis to evaluate the relation between patient characteristics and functional outcomes. Ethgen and colleagues50 also conducted a systematic review to evaluate health-related quality of life in patients who had knee arthroplasties. They determined that age and weight did not affect improvement in functional outcomes. Although they suggested that men benefitted more from arthroplasty than women, the evidence to support this finding is not substantive. The qualitative summaries in both these reviews depict much variation in the influence of the patient characteristics. Despite the varied eligibility criteria in these other reviews, as in our systematic review, the studies do not show an unequivocal relation between the patient characteristics and outcomes. As identified in our review, the methodo-logic quality of all these studies is limited. The inclusion criteria for study patients were not always clearly specified, and they likely reflected the selection biases of surgeons. In addition, the operational definitions of some important outcomes such as pain were nonstandardized. Thus we believe future reviews or meta-analyses should not include studies from an older chronological period because this typically magnifies methodologic limitations.

Our study has several specific limitations. First, we limited our review to patients with osteoarthritis; therefore, extension of the findings to other diagnoses such as rheumatoid arthritis may be limited. Second, our review included only studies with a sample size of 500 or more patients. Because our initial search yielded more than 14 000 citations, we considered such a restriction to be necessary to yield a manageable number of studies. This may have resulted in the exclusion of some studies that might have provided useful information. However, given the limitations of the literature noted above, we do not believe these studies would dramatically affect our conclusions. Third, we did not perform manual searches of relevant journals or contact organizations to identify additional studies or unpublished work meeting our eligibility criteria.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that subgroups of patients, particularly men and older patients, are at higher risk of death and revision following total joint arthroplasty. The risks were higher in some subgroups than others, but overall risks for all groups remained very small. Thus in no specific subgroup of patients did total joint arthroplasty appear contraindicated. This is relevant to decision-making since many physicians often advise the patients they are too old or obese to receive total joint arthroplasty. Future studies are needed to address the methodologic limitations identified in this study to more clearly advise patients and doctors on how patient characteristics affect the outcome of total joint arthroplasty.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wright is the Robert B. Salter Chair of Surgical Research. Dr. Coyte is a Canadian Health Services Research Foundation/Canadian Institutes of Health Research Health Services Chair. Dr. Hawker is supported as the FM Hill Chair in Academic Women's Medicine and as the Arthritis Society's Distinguished Senior Research Investigator. The research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. Drs. Santaguida and Wright acquired the data, which Drs. Santaguida, Hawker, Hudak, Kreder and Wright analyzed. Drs. Santaguida, Hudak and Wright wrote the article, which all authors reviewed. All authors approved the final version for publication.

Competing interests: Dr. Mahomed has received consulting fees from Smith & Nephew. None declared for Drs. Santaguida, Hawker, Hudak, Glazier, Kreder, Coyte and Wright.

Accepted for publication Dec. 5, 2007

Correspondence to: Dr. J.G. Wright, The Hospital for Sick Children, 555 University Ave., Rm. 1254, Toronto ON M5G 1X8; fax 416 813-7369; james.wright@sickkids.ca

References

- 1.Harris WH, Sledge CB. Total hip and total knee replacement (1). N Engl J Med 1990; 323:725-31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Harris WH, Sledge CB. Total hip and total knee replacement (2). N Engl J Med 1990; 323:801-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Chang RW, Pellisier JM, Hazen GB. A cost-effectiveness analysis of total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the hip. JAMA 1996;275:858-65. [PubMed]

- 4.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Determining the need for hip and knee arthroplasty: the role of clinical severity and patients' preferences. Med Care 2001;39: 206-16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Wright JG, Coyte P, Hawker G, et al. Variation in orthopedic surgeons' perceptions of the indications for and outcomes of knee replacement. CMAJ 1995;152: 687-97. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Coyte PC, Hawker G, Croxford R, et al. Rates of revision knee replacement in Ontario, Canada. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999;81:773-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Wright JG, Hawker GA, Bombardier C, et al. Physician enthusiasm as an explanation for area variation in the utilization of knee replacement surgery. Med Care 1999; 37: 946-56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Young NL, Cheah D, Waddell JP, et al. Patient characteristics that affect the outcome of total hip arthroplasty: a review. Can J Surg 1998;41:188-95. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Callahan CM, Drake BG, Heck DA, et al. Patient outcomes following tricompartmental total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. JAMA 1994;271:1349-57. [PubMed]

- 10.Callahan CM, Drake BG, Heck DA, et al. Patient outcomes following unicompartmental or bicompartmental knee arthroplasty. A meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 1995; 10:141-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Lomas J. Diffusion, dissemination, and implementation: Who should do what? Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993;703:226-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.McKibbon A, Eady A, Marks S. PDQ Evidence-based principles and practice. Hamilton (ON): BC Decker Inc; 1999.

- 13.Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers Handbook. Version 4.1.4. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2001. Oxford: Update Software; 2001.

- 14.Berlin JA. Does blinding of readers affect the results of meta-analyses? Lancet 1997;350:185-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hudak PL, Cole DC, Haines AT. Understanding prognosis to improve rehabilitation: the example of lateral elbow pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996;77:586-93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Johnsson R, Franzen H, Nilsson LT. Combined survivorship and multivariate analyses of revisions in 799 hip prostheses. A 10- to 20-year review of mechanical loosening. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994; 76:439-43. [PubMed]

- 17.Malchau H, Herberts P, Ahnfelt L. Prognosis of total hip replacement in Sweden. Follow-up of 92,675 operations performed 1978-1990. Acta Orthop Scand 1993;64:497-506. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kreder HJ, Deyo RA, Koepsell T, et al. Relationship between the volume of total hip replacements performed by providers and the rates of postoperative complications in the state of Washington. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997;79:485-94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Skeie S, Lende S, Sjoberg EJ, et al. Survival of the Charnley hip in coxarthrosis. A 10–15-year follow-up of 629 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1991;62:98-101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Ahnfelt L, Herberts P, Malchau H, et al. Prognosis of total hip replacement. A Swedish multicenter study of 4,664 revisions. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1990;61: 1-26. [PubMed]

- 21.Herberts P, Ahnfelt L, Malchau H, et al. Multicenter clinical trials and their value in assessing total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989;(249):48-55. [PubMed]

- 22.Havelin LI, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, et al. Early failures among 14,009 cemented and 1,326 uncemented prostheses for primary coxarthrosis. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, 1987–1992. Acta Orthop Scand 1994;65:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Havelin LI, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, et al. The effect of the type of cement on early revision of Charnley total hip prostheses. A review of eight thousand five hundred and seventy-nine primary arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:1543-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Johnsson R, Thorngren KG, Persson BM. Revision of total hip replacement for primary osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:56-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, et al. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987–99. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83:579-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Herberts P, Malchau H. How outcome studies have changed total hip arthroplasty practices in Sweden. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997;(344):44-60. [PubMed]

- 27.Morrey BF, Ilstrup D. Size of the femoral head and acetabular revision in total hip-replacement arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1989;71:50-5. [PubMed]

- 28.Whittle J, Steinberg EP, Anderson GF, et al. Mortality after elective total hip arthroplasty in elderly Americans. Age, gender, and indication for surgery predict survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993t;(295):119-26. [PubMed]

- 29.Lie SA, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI, et al. Mortality after total hip replacement: 0–10-year follow-up of 39,543 patients in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand 2000;71:19-27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Lindberg H, Carlsson AS, Lanke J, et al. The overall mortality rate in patients with total hip arthroplasty, with special reference to coxarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1984;(191):116-20. [PubMed]

- 31.Soderman P. On the validity of the results from the Swedish National Total Hip Arthroplasty register. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 2000;71:1-33. [PubMed]

- 32.Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, et al. Patient satisfaction and function after primary and revision total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998;(351): 135-48. [PubMed]

- 33.Soderman P, Malchau H, Herberts P, et al. Are the findings in the Swedish National Total Hip Arthroplasty Register valid? A comparison between the Swedish National Total Hip Arthroplasty Register, the National Discharge Register, and the National Death Register. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15: 884-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Visuri T, Koskenvuo M, Honkanen R. The influence of total hip replacement on hip pain and the use of analgesics. Pain 1985;23:19-26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Stickles B, Phillips L, Brox WT, et al. Defining the relationship between obesity and total joint arthroplasty. Obes Res 2001; 9: 219-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, et al. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register 1975–1997: an update with special emphasis on 41,223 knees operated on in 1988-1997. Acta Orthop Scand 2001;72: 503-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Knutson K, Lewold S, Robertsson O, et al. The Swedish knee arthroplasty register. A nation-wide study of 30,003 knees 1976-1992. Acta Orthop Scand 1994;65: 375-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Heck DA, Melfi CA, Mamlin LA, et al. Revision rates after knee replacement in the United States. Med Care 1998;36:661-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Scuderi GR, Insall JN, Windsor RE, et al. Survivorship of cemented knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1989;71: 798-803. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, et al. The routine of surgical management reduces failure after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83:45-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Hawker G, Wright J, Coyte P, et al. Health-related quality of life after knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998; 80:163-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Spicer DDM, Pomeroy DL, Badenhausen WE, et al. Body mass index as a predictor of outcome in total knee replacement. Int Orthop 2001;25:246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, et al. The routine of surgical management reduces failure after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83:45-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Whiteside LA. The effect of patient age, gender, and tibial component fixation on pain relief after cementless total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1991; (271):21-7. [PubMed]

- 45.Altman DG. Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. BMJ 2001; 323:224-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.French SD, McDonald S, McKenzie JE, et al. Investing in updating: how do conclusions change when Cochrane systematic reviews are updated? BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Stead LF, Lancaster T, Silagy CA. Updating a systematic review — What difference did it make? Case study of nicotine replacement therapy. BMC Med Res Methodol 2001;1:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Barrowman NJ, Fang M, Sampson M, et al. Identifying null meta-analyses that are ripe for updating. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Kane RL, Saleh KJ, Wilt TJ, et al. Total knee replacement. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2003;(86):1-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Ethgen O, Bruyere O, Richy F, et al. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-A:963-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Soderman P. On the validity of the results from the Swedish National Total Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 2000;71:1-33. [PubMed]

- 52.Soderman P, Malchau H, Herberts P. Outcome of total hip replacement: a comparison of different measurement methods. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;(390): 163-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Soderman P, Malchau H, Herberts P, et al. Outcome after total hip arthroplasty: Part II. Disease-specific follow-up and the Swedish National Total Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand 2001;72: 113-9. [DOI] [PubMed]