Abstract

The Candida albicans plasma membrane plays important roles in cell growth and as a target for antifungal drugs. Analysis of Ca-Sur7 showed that this four transmembrane domain protein localized to stable punctate patches, similar to the plasma membrane subdomains known as eisosomes or MCC that were discovered in S. cerevisiae. The localization of Ca-Sur7 depended on sphingolipid synthesis. In contrast to S. cerevisiae, a C. albicans sur7Δ mutant displayed defects in endocytosis and morphogenesis. Septins and actin were mislocalized, and cell wall synthesis was very abnormal, including long projections of cell wall into the cytoplasm. Several phenotypes of the sur7Δ mutant are similar to the effects of inhibiting β-glucan synthase, suggesting that the abnormal cell wall synthesis is related to activation of chitin synthase activity seen under stress conditions. These results expand the roles of eisosomes by demonstrating that Sur7 is needed for proper plasma membrane organization and cell wall synthesis. A conserved Cys motif in the first extracellular loop of fungal Sur7 proteins is similar to a characteristic motif of the claudin proteins that form tight junctions in animal cells, suggesting a common role for these tetraspanning membrane proteins in forming specialized plasma membrane domains.

INTRODUCTION

The plasma membrane carries out many complex functions in addition to acting as a protective layer around the cell. It is a highly regulated zone that must interface with the external environment and also interact with intracellular components to mediate processes such as endocytosis, secretion, and morphogenesis. Studies on plasma membrane organization in animal cells indicate that it is composed of discrete domains, including fluid domains where components readily diffuse and also specialized subdomains, such as lipid rafts and protein-organized barriers to diffusion (Brown and London, 2000; Nakada et al., 2003; Hemler, 2005). The plasma membrane of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is composed of at least two distinct domains (Malinska et al., 2003, 2004). One domain contains proteins that readily diffuse, such as the plasma membrane ATPase Pma1. Another plasma membrane domain appears as 300-nm punctate patches that are immobile. This latter domain was termed MCC (membrane compartment occupied by Can1), since it contains the Can1 arginine permease (Malinska et al., 2003, 2004). Subsequent studies in S. cerevisiae have shown that these immobile punctate plasma membrane domains also correspond to static sites of endocytosis that have been named eisosomes (Walther et al., 2006).

The role of the eisosomes/MCC in endocytosis was elucidated in part by the discovery that these patches also include the Pil1 and Lsp1 proteins that function in endocytosis (Walther et al., 2006). Pil1 and Lsp1 are paralogous cytoplasmic proteins that attach to the inner surface of the plasma membrane in patches that colocalize with the Sur7 transmembrane protein in the MCC (Walther et al., 2006). Detection of other proteins that localize to eisosome/MCC patches indicates that these domains also carry out additional functions. For example, the sphingolipid-responsive Pkh1/2 protein kinases were found to associate with Pil1 and Lsp1 in eisosomes (Walther et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2008). The Pkh1/2 protein kinases are homologues of mammalian phosphoinositide-dependent kinases, which influence a variety of processes including endocytosis, cell wall integrity, actin localization, and response to heat stress (Dickson et al., 2006; Dickson, 2008). Recent studies have also shown that the Pkh1/2 protein kinases appear to phosphorylate Pil1 and Lsp1 and to mediate the effects of sphingolipids on the regulation of the assembly and disassembly of eisosomes (Walther et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2008).

Other proteins that have been localized to eisosomes/MCC are proton symporters, such as Can1 (Malinska et al., 2003, 2004). The proton symporters are distinct in that they are present in eisosomes in a manner that depends on the membrane potential (Grossmann et al., 2007). The membrane potential was also required to observe more intense filipin staining of the eisosomes, which suggests that these domains have a special lipid composition in which ergosterol is either enriched or is more accessible to staining. It was suggested that segregation of the inward proton pumping activity of the symporters away from the outward proton pumping activity of the plasma membrane H+ATPase Pma1 may have physiological significance (Malinska et al., 2003; Grossmann et al., 2007).

Sur7 is thus far the only known transmembrane protein that is continuously localized to eisosomes/MCC, even in the absence of membrane potential (Grossmann et al., 2007). The Sur7 sequence contains four putative transmembrane domains (TMDs). It lacks other obvious motifs, except for a Cys-containing sequence in extracellular loop 1 that is similar to a motif present at the same position in the claudin family of membrane proteins that will be described in this study (see Discussion). The claudin family members form membrane barrier domains in animal cells, such as tight junctions (Furuse and Tsukita, 2006). SUR7 has been implicated in endocytosis because its overexpression partially suppresses the defects caused by mutation of RVS161 or RVS167 (Sivadon et al., 1997), which encode BAR domain proteins that function in the scission phase of endocytosis (Toret and Drubin, 2006). Surprisingly, although Sur7 is thought to be a significant component of eisosomes in S. cerevisiae, present at an estimated several hundred copies per patch, its function is not known. Deletion of SUR7 in S. cerevisiae caused only minor effects (Young et al., 2002). Deletion of two other SUR7-related genes (FMP45 and YNL194C), either singly or in combination, also did not have strong effects. The triple mutant showed a slight reduction in sporulation and an altered pattern of membrane sphingolipids (Young et al., 2002). It is also not clear why Sur7 and the other components of eisosomes/MCC are immobile. The restricted mobility of Sur7 is not dependent on actin, microtubules, or the cell wall (Malinska et al., 2004), although an earlier study suggested a possible role for the cell wall (Young et al., 2002).

Candida albicans Sur7 was detected previously in the detergent-resistant fraction of the plasma membrane (Alvarez and Konopka, 2007) and was therefore investigated further in this study to better understand plasma membrane organization in this human fungal pathogen. C. albicans is an interesting system for analysis of plasma membrane function, because it responds to environmental signals to grow in a variety of morphologies ranging from round budding cells to highly polarized hyphae (Sudbery et al., 2004). Studies on the C. albicans plasma membrane also have important implications for understanding the mechanisms of the commonly used antifungal drugs (i.e., fluconazole, amphotericin, and echinocandins), which function by altering membrane sterol production, forming pores in the plasma membrane, and blocking cell wall growth (Odds et al., 2003). Another potential advantage is that, in contrast to S. cerevisiae, the C. albicans genome appears to contain only two SUR7-related genes (orthologues of SUR7 and FMP45). The results of these studies demonstrate that Sur7 affects a broad range of functions in C. albicans including endocytosis, localization of actin and septins, and is also required to prevent abnormal intracellular growth of the cell wall.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Media

The C. albicans and S. cerevisiae strains used in this study (described in Table 1) were propagated on rich YPD medium or on synthetic medium essentially as described (Sherman, 1991). Uridine, 80 mg/l, was added to C. albicans cultures. The C. albicans SUR7-GFP strain was created by homologous recombination of green fluorescent protein (GFP) sequences into the 3′ end of the SUR7 open reading frame (ORF). The DNA used for the transformation was created by PCR using primers that contain ∼70 base pairs of sequence homologous to the 3′ end of the SUR7 open reading frame to amplify a cassette containing GFP and a URA3 selectable marker (Gerami-Nejad et al., 2001). The colonies resulting from the transformation into C. albicans were then screened for GFP-positive cells by fluorescence microscopy. A similar approach was used to create an LSP1-GFP fusion in C. albicans. A STE2-GFP fusion expressed under the control of ADH promoter in plasmid pADH-STE2-GFP was linearized by digestion with NotI and then introduced into C. albicans using selection for URA3. Strains containing CDC12-GFP were created by linearizing plasmid pAW-CDC12-GFP by digestion with BsaBI, which was then integrated into the CDC12 locus and selected for using the URA3 marker as described previously (Warenda and Konopka, 2002).

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Parent | Genotype |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans strains | ||

| BWP17 | Sc5314 | ura3Δ::λimm434/ura3Δ::λimm434 his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG |

| DIC185 | BWP17 | ura3Δ::λimm434/URA3 his1::hisG/HIS1 arg4::hisG/ARG4 |

| YJA10 | BWP17 | sur7Δ::ARG4/sur7Δ::HIS1 ura3Δ::λimm434/ura3Δ::λimm434 his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG |

| YJA11 | YJA10 | sur7Δ::ARG4/sur7Δ::HIS1 URA3/ura3Δ::λimm434 his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG |

| YJA12 | YJA10 | sur7Δ::ARG4/sur7Δ::HIS1 SUR7::URA3 ura3Δ::λimm434/ura3Δ::λimm434 his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG |

| YJA13 | YJA10 | sur7Δ::ARG4/sur7Δ::HIS1 ura3Δ::λimm434/ura3Δ::λimm434 his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG ADH-STE2-GFP::URA3 |

| YJA14 | YJA10 | sur7Δ::ARG4/sur7Δ::HIS1 ura3Δ::λimm434/ura3Δ::λimm434 his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG CDC12-GFP::URA3 |

| YJA15 | BWP17 | BWP17, except SUR7-GFP::URA3 |

| YJA16 | BWP17 | BWP17, except PIL1-GFP::URA3 |

| YJA17 | YJA10 | sur7Δ strain YJA10, except PIL1-GFP::URA3 |

| YAW44 | BWP17 | BWP17, except CDC12-GFP::URA3 |

| YAW54 | BWP17 | BWP17, except pADH-STE2-URA3 |

| S. cerevisiae strains | ||

| BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | |

| BY4742 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | |

| YJA24 | BY4741 | BY4741 plus sur7::kanR ylr414c::HIS3 fmp45::LEU2 ynl194c::URA3 |

| YLD38 | BY4742 | BY4742 plus SUR7-RFP::HIS3 |

| Ynlr414c-GFP | BY4741 | BY4741 plus YLR414C-GFP::HIS3 |

| YLD39 | BY4741/BY4742 diploid. MATα his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0 met15Δ0/MET15 lys2Δ0/LYS2 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0 SUR7-GFP::HIS3 YLR414C-GFP::HIS3 |

A homozygous sur7Δ mutant (YJA10) was constructed in C. albicans strain BWP17 as described previously (Wilson et al., 1999). In brief, PCR primers containing ∼70 base pairs of sequence homologous to the sequences flanking the open reading frame of SUR7 were used to amplify either the ARG4 or HIS1 selectable marker genes. Integration of the deletion cassettes at the appropriate sites was verified by PCR using combinations of primers that flanked the integration and also primers that annealed within the introduced cassettes. A strain in which the sur7Δ mutations were complemented by reintroduction of one wild-type copy of SUR7 was constructed by PCR amplification of the genomic sequence from 1000 base pairs upstream of the initiator ATG to 300 bases downstream of the terminator codon of SUR7. This DNA fragment was then inserted between the SacI and SacII restriction sites of the URA3 plasmid pDDB57 (Wilson et al., 2000). The resulting plasmid was linearized in the promoter region by digestion with BsrGI, and integrated into the sur7Δ strain YJA10 using URA3 selection to create a complemented strain called YJA12.

S. cerevisiae strains deleted for orthologues of SUR7 were constructed by a successive set of gene deletions. The initial strain was obtained from the S. cerevisiae genome deletion strain collection and contained a sur7::kanR deletion. Next, PCR amplification cassettes were used to replace the YLR414C with Schizosaccharomyces pombe his5 (Longtine et al., 1998), FMP45 with Candida glabrata LEU2 (plasmid template kindly provided by Dr. Linda Huang, University of Massachusetts, Boston, MA), and YNL194C with C. albicans URA3 (Goldstein et al., 1999). Heterologous genes were used as selectable markers to help promote integration at the targeted locus instead of at the position of the chromosomal copy of the marker gene. The presence of all four deletions mutations and the absence of the corresponding wild-type genes was verified by PCR. Similar results were obtained with independently derived mutants. Colocalization of Sur7-red fluorescent protein (RFP) and Ylr414c-GFP was carried out using strain YLD39, which was constructed by mating the Ylr414c-GFP strain from the yeast GFP-tagged collection (Huh et al., 2003) to a Sur7-RFP strain (YLD38).

Sensitivity to antifungal drugs was assayed using Etest strips according to the directions of the manufacturer (AB Biodisk, Piscataway, NJ). Cells, 1 × 106, were spread on a plate containing RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 0.165 M MOPS, pH 7, and 2% dextrose. The plate was allowed to dry, and then an Etest strip was applied, and the plates were incubated at 37° for 48 h.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Cells used for analysis of GFP-tagged fusion proteins by microscopy were grown overnight to log phase. Fluorescence microscopy was used to detect GFP and differential interference contrast (DIC) optics were used to detect cell morphology. Endocytosis of the fluorescent dye FM 4-64 was carried out essentially as described previously (Vida and Emr, 1995). FM 4-64 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to cells to a final concentration of 20 μM, samples were incubated on ice for 15 min to stain the plasma membrane. The cells were washed and incubated for the indicated time at 30°, the internalization was stopped by adding sodium azide and sodium fluoride to a final concentration of 10 mM, and then the cells were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Ste2-GFP endocytosis was examined in cells incubated in the presence or absence of 5 × 10−7 M C. albicans α-factor mating factor pheromone (synthesized by Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL, and purified by Stony Brook University Proteomics Facility). Actin localization was determined using rhodamine-phalloidin essentially as described (Adams and Pringle, 1991). In brief, samples of cells were fixed for 1 h with 5% paraformaldehyde, incubated with 5 U of rhodamine-phalloidin (Invitrogen) for 1.5 h, and then viewed by fluorescence microscopy. Chitin staining was carried out by incubating cells with 20 ng/ml Calcofluor White as described (Pringle, 1991). To visualize the intracellular growth of cell wall in the sur7Δ mutant, cells were first permeabilized by washing with methanol and acetone and then stained with Calcofluor White, Aniline Blue (0.05%), or concanavalin A-FITC (20 μg/ml). Filipin staining of C. albicans was performed essentially as described previously (Martin and Konopka, 2004) by treating cells with 200 μg/ml filipin and then analyzing them immediately by fluorescence microscopy. Calcofluor, concanavalin FITC, and Filipin were purchased from Sigma, and Aniline Blue was purchased from J. T. Baker Chemical (Phillipsburg, NJ). Images were captured using an Olympus BH2 microscope (Melville, NY) equipped with a Zeiss AxioCam digital camera (Thornwood, NY).

Electron Microscopy

Samples used for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were processed using standard techniques. Briefly, samples were collected in centrifuge tubes and fixed with 3% electron microscopy (EM) grade glutaraldehyde in 1× sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature. After fixation, samples were washed in buffer and resuspended in an aqueous 4% permanganate solution, washed, stained with uranyl acetate, dehydrated through a graded series of ethyl alcohol and embedded in Epon resin. Ultrathin sections of 80 nm were cut with a Reichert-Jung (Heidelberg, Germany) UltracutE ultramicrotome and placed on formvar-coated slot copper grids. Sections were viewed with a FEI Tecnai12 BioTwinG2 electron microscope (Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Digital images were acquired with an AMT XR-60 CCD Digital Camera System. The TEM analyses were carried out at the Central Microscopy Imaging Center at Stony Brook University.

Microarray Analysis of Gene Expression

RNA was extracted from 3 × 108 cells using a RiboPure-Yeast RNA isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). cDNA was synthesized using a Superscript II kit (Invitrogen) in a poly(T)-primed reaction containing a 3:2 mixture of aminoallyl-dUTP:dTTP plus dATP, dCTP, and dGTP. After RNAse treatment, samples were purified on a silica gel column (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), coupled to NHS-reactive Cy3 or Cy5 dyes (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ), and then dye incorporation was assayed spectrophotometrically. Control and experimental samples were mixed and hybridized in a Tecan (Durham, NC) HS4300 ProHybridization station to custom arrays from the Washington University Genome Sequencing Center that are spotted in triplicate with one 70-mer oligonucleotide for each open reading frame in the C. albicans ORF19 database (Brown et al., 2006). Arrays were scanned using an Agilent G2505B microarray scanner.

Analysis of Sur7 Homologues

BLAST searches (Altschul et al., 1990) were carried out to identify Sur7 homologues in the genome sequences of other organisms present at the Web site of the National Center for Biotechnology (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) or the S. cerevisiae Genome Database (http://www.yeastgenome.org). Multiple sequence alignments of the predicted Sur7 proteins and an evolutionary tree of their relatedness were carried out using Clustal W (Thompson et al., 1994).

RESULTS

C. albicans Sur7 Localizes to Static Patches in the Plasma Membrane

To determine if the properties of Sur7 were conserved in C. albicans, Sur7-GFP was examined and found as expected to localize in punctate patches (Figure 1A). The Sur7-GFP patches appeared to be less prominent in the buds and emerging hyphae (germ tubes). This could be due to the delay in GFP folding (Malinska et al., 2003), or it could indicate that the formation of new patches is regulated in buds and germ tubes (Walther et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2008). Similar to MCC/eisosome proteins in S. cerevisiae, the Ca-Sur7-GFP patches were extremely stable, with little or no mobility observed over 30 min (Figure 1B). The role of sphingolipids in the stability of the Sur7-GFP patches was examined by treating cells with myriocin to block an early step in sphingolipid synthesis (Figure 1C). Previous studies in S. cerevisiae showed that myriocin treatment shifted the localization of the Pil1 eisosome protein from membrane patches to the cytoplasm (Walther et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2008). Myriocin treatment of C. albicans disrupted the Sur7-GFP patches, but the Sur7-GFP remained in the plasma membrane as the fluorescence was maintained at the cell periphery (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Sur7-GFP is present in static patches in the plasma membrane. C. albicans strain YJA15 carrying a SUR7-GFP fusion gene was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. (A) Cells were grown in YPD medium to promote budding growth (left panel) and in GlcNAc medium to induce hyphal morphogenesis (middle and right panels). (B) Stability of the Sur7-GFP patches was examined by comparing pictures of the same cells taken 30 min apart. The merged images demonstrate the high degree of overlap of the patches. (C) Cells were treated with 5 or 25 μM myriocin for 90 min to block sphingolipid synthesis, and then Sur7-GFP fluorescence was recorded. Bars, 10 μm.

sur7Δ Mutant Is Defective in Endocytosis

The function of SUR7 was examined by creating a homozygous deletion strain in which both copies of the gene were deleted from the diploid C. albicans genome (see Materials and Methods). Cells were then tested for ability to undergo endocytosis by following the trafficking of the lipophilic dye FM 4-64. Wild-type SUR7 cells showed the expected result that FM 4-64 fluorescence was readily observed in the vacuolar membrane at 15 min, and trafficking to the vacuole was nearly complete by 30 min (Figure 2A). In contrast, the sur7Δ cells showed a slight delay in loss of FM 4-64 from the plasma membrane at 15 min and a more pronounced delay in the trafficking of small vesicle-sized particles to a larger vacuolar structure, because it took ∼60 min before vacuolar staining was readily detected. This defect was specific for the sur7Δ mutation, because it could be largely complemented by reintroduction of one copy of the wild-type SUR7 (Figure 2A). Thus, in contrast to S. cerevisiae, Ca-SUR7 has a readily detectable function in endocytosis.

Figure 2.

sur7Δ is defective in endocytosis. A control C. albicans strain (DIC185), a sur7Δ strain (YJA11), and a complemented version of this strain in which one copy of SUR7 was reintroduced (YJA12) were assayed for ability to undergo endocytosis in two different assays. (A) Cells were treated with the lipophilic dye FM4-64 and then monitored after 15, 30, and 60 min by fluorescence microscopy for the accumulation of the fluorescence in the vacuolar membrane. (B) Ligand-induced endocytosis of the α-factor mating pheromone receptor was examined in wild-type (YAW54) or sur7Δ (YJA13) cells engineered to express STE2-GFP from the constitutive ADH promoter to avoid the need to convert the cells to the homozygous MATa/MATa genotype. Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 5 × 10−7 M C. albicans α-factor for 60 min.

The sur7Δ mutant was examined further by assaying ligand-induced endocytosis of Ste2, the α-factor mating pheromone receptor. STE2-GFP was expressed in the MATa/α C. albicans cells under the control of the constitutive ADH promoter (see Materials and Methods). Treatment of wild-type SUR7 cells with α-factor caused a dramatic shift in the localization of Ste2-GFP from the plasma membrane to the vacuole (Figure 2B). This shows that ligand-induced internalization of Ste2 can be used as a marker for endocytosis in MATa/α C. albicans cells that lack a functional pheromone signal pathway, as has been done in S. cerevisiae (Zanolari et al., 1992). The sur7Δ cells were partially defective in internalizing Ste2-GFP in response to α-factor, indicating that they are defective in ligand-induced endocytosis in addition to their defect in steady-state internalization of FM 4-64 (Figure 2A). However, the ability to assess Ste2-GFP endocytosis in the sur7Δ cells was affected by the altered localization of Ste2-GFP even in the absence of α-factor, which may be due to altered plasma membrane structure that will be described below.

Lsp1 Localization Is Not Dependent on Sur7

S. cerevisiae Sur7 has been implicated in binding to the Lsp1 and Pil1 proteins that localize to eisosomes and function in endocytosis (Walther et al., 2006, 2007). We therefore examined the localization of C. albicans Lsp1-GFP in the sur7Δ mutant to determine if Sur7 is required to organize Lsp1 into eisosome patches. (We will follow the nomenclature of the Candida Genome Database and refer to orf19.3149 as the Lsp1 ortholog, even though it actually aligns slightly better with S. cerevisiae Pil1. Note that Lsp1 and Pil1 are very closely related in C. albicans [81% identity], making it difficult to determine which of these proteins is the ortholog of S. cerevisiae Lsp1). Lsp1-GFP showed the expected punctate distribution in wild-type C. albicans. Surprisingly, Lsp1-GFP also showed a punctate localization pattern similar to that in the sur7Δ cells (Figure 3A). To determine if the lack of Sur7 affected the immobile nature of the patches, images were recorded of the same cells after various times of incubation (Figure 3B). The Lsp1-GFP patches did not appear to shift position over a 30-min time course of analysis in either the wild-type or the mutant cells, indicating that Sur7 is not needed to restrict the mobility of the Lsp1-GFP patches. Preliminary studies using FRAP (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching) indicated there was no obvious effect of the sur7Δ mutation on the exchange of Lsp1-GFP subunits between eisosome patches (not shown). The rate of recovery of Lsp1-GFP into the photobleached regions was very slow in both the wild-type and sur7Δ mutant cells. Thus, although mutation of SUR7 causes a phenotype in C. albicans, Sur7 is not required for clustering of Lsp1-GFP into eisosome patches on the plasma membrane.

Figure 3.

Lsp1-GFP localizes to plasma membrane patches in sur7Δ cells. (A) The localization of Lsp1-GFP was analyzed in wild-type SUR7 cells (YJA16) and sur7Δ mutant cells (YJA17) by fluorescence microscopy. The middle of the cells was mainly in the focal plane, so the Lsp1-GFP appears primarily as patches around the periphery of the cell. (B) The stability of the Lsp1-GFP patches in the sur7Δ strain YJA17 was assessed by comparing images of the same cells recorded 30 min apart. The merge shows that the Lsp1-GFP patches remain essentially unchanged. The tops of the cells were in the focal plane to more readily observe the stability of the Lsp1-GFP patches.

Morphogenesis and Actin Localization Defects in sur7Δ Cells

Cultures of the sur7Δ mutant exhibited a variety of different morphologies ranging from relatively normal-looking cells to large cells with broad bud necks (Figure 4B). Time-lapse studies revealed that the large cells resulted at least in part from continued growth of mother cells during bud morphogenesis (not shown), indicating a breakdown in the mechanisms that usually polarize new growth to the bud. Consistent with this, rhodamine-phalloidin staining revealed that actin was mislocalized in the sur7Δ mutants. The cortical patches of actin that lie on the inner surface of the plasma membrane were primarily restricted to the buds of wild-type cells, but were present in both mother and daughter cells in the sur7Δ mutant (Figure 4B). Wild-type cells also contained a series of actin cables that span from the bud to the mother cell, which facilitate polarized growth by mediating transport of secretory vesicles to the bud (Figure 4A). Obvious cables were not detected in the sur7Δ cells, but they did appear to contain faint structures that resembled a network of thin filaments.

Figure 4.

Actin polarization defect in sur7Δ cells. The control strain (DIC185; A) and the sur7Δ mutant (YJA11; B) were grown to log phase and then fixed and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin to detect actin localization (see Materials and Methods). Note that essentially all sur7Δ cells showed abnormal actin polarization, even those that appeared to have relatively normal morphology.

Sur7 Is Needed to Restrict Septin Proteins to the Bud Neck

The wide bud necks and continued growth of the mother cells suggested that septin function might be compromised in the sur7Δ mutant. Septin proteins localize to the bud neck where they carry out several functions, including the recruitment of proteins that function in cytokinesis (Longtine and Bi, 2003; Douglas et al., 2005; Gladfelter, 2006). Septins also function as a boundary domain that helps to maintain cell polarization by restricting plasma membrane proteins and cortical actin patches to the bud (Barral et al., 2000; Takizawa et al., 2000). Control SUR7 cells showed expected localization of a GFP-tagged septin protein (Cdc12-GFP) to the bud neck (Figure 5). The septins appear as a single ring at early stages of the cell cycle and at later stages appear as a split ring. Septum formation occurs between the rings. In contrast, Cdc12-GFP was mislocalized in the sur7Δ cells and was found in patches throughout the bud and mother cell plasma membranes (Figure 5). Interestingly, in ∼14% of the sur7Δ cells (n = 407) the septins appeared to form small ring structures at ectopic sites away from an existing bud neck, and some cells contained multiple rings. Cdc12-GFP detected at the bud neck in sur7Δ cells formed rings that appeared to be fainter and disrupted. Consistent with altered septin localization, the cells also showed an uneven distribution of chitin detected by Calcofluor staining (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Abnormal septin localization at sites distal to the bud neck in sur7Δ cells. Septin localization was monitored by analysis of a Cdc12-GFP fusion protein in a wild-type control strain (YAW44; A) and sur7Δ strain (YJA14; B). (C) A higher magnification image of Cdc12-GFP localization in the sur7Δ strain. Top panels, Cdc12-GFP; middle panels, Calcofluor White stain of cell wall chitin; bottom panels, DIC images. Bars, 5 μm.

Sur7 Prevents Intracellular Growth of Cell Wall

The altered morphology and cell wall organization of the sur7Δ mutant was analyzed in more detail by TEM. Sections of wild-type SUR7 cells showed the expected smooth cell wall layer evenly surrounding the cell (Figure 6A). The sur7Δ mutant was dramatically different in that the cell wall was thicker and more uneven than in wild-type cells (Figure 6B). The septa were also abnormal looking and thicker, but appeared to contain the expected chitin-rich primary septum that is characteristically observed as a thin clear zone in EM analysis (Figure 6C). More significant, however, was the appearance of cell wall material in the cytoplasm of the sur7Δ mutant. In most cases the intracellular cell wall appeared as torus-shaped structures, suggesting that they may represent tubes of cell wall growth through the cytoplasm. These structures were most frequently detected in mother cells, and to a lesser degree in buds and emerging hyphae. Comparison of cells with different amounts of abnormal cell wall suggested the following trends (Figure 6D). In cells with relatively minor cell wall abnormalities, the unusual cell wall growth was restricted to the periphery in the form of small invaginations into the cytoplasm. Cells with intermediate levels of unusual wall growth contained torus-shaped structures in the middle of the cell and occasionally spikes, as well as abnormalities around the cell periphery. Cells with high levels of unusual wall growth contained more of the abnormal structures that were also thicker, suggesting that they continue to grow over time.

Figure 6.

EM analysis of abnormal cell wall growth in sur7Δ cells. The wild-type strain DIC185 (A) and the sur7Δ strain YJA11 (B) were analyzed by TEM. Note in the sur7Δ mutant the abnormal appearance of torus-shaped structures of cell wall material and also the variations in cell wall thickness. Arrows indicate sites of invaginations of cell wall growth. (C) Higher magnification view of the septum of a sur7Δ mutant cell. Primary septum indicated by an arrowhead. (D) Representative sur7Δ cells exhibiting different amounts of abnormal intracellular wall growth. (E) Higher magnification images of abnormalities associated with the cell wall. Cells were analyzed by TEM as described in Materials and Methods. (A–D) black bars, 1 μm; (E) white bars, 100 nm.

Closer inspection of the cell wall suggested a possible sequence of events in formation of the unusual structures (Figure 6E). In some sur7Δ cells, the plasma membrane appeared to overlap and form convoluted structures. Similar plasma membrane abnormalities were also detected in which the space between the overlapping membranes is partially or completely filled in with cell wall material. Continued growth of these structures could lead to the formation of the larger cell wall abnormalities.

The structure of the abnormal cell wall growth in the sur7Δ cells was characterized further in cells that were permeabilized by methanol treatment to permit staining of intracellular cell wall chitin with Calcofluor. A variety of abnormal structures were stained in the sur7Δ cells, including long tubes that in some cases span most of the length of the cell (Figure 7B). These structures were never seen in the wild-type cells analyzed in the same way (Figure 7A). The structure of the intracellular cell wall growth was analyzed further by deconvolution microscopy to create a reconstructed three-dimensional image (see Supplementary Movie). This analysis indicated that at least some of the tubes in the sur7Δ mutant appeared to arise from previous sites of septum formation. Other structures were also detected, including some that resembled a wide sheet of cell wall growth. To our knowledge, such extreme intracellular cell wall structures have not been reported previously and may therefore reveal new aspects in the control of the spatial and temporal regulation of cell wall formation (see Discussion).

Figure 7.

Characterization of intracellular cell wall growth in sur7Δ cells. The cell wall composition of wild-type strain DIC185 (A), sur7Δ strain YJA11(B), or the sur7Δ mutant strain YJA12 (C), in which one copy of SUR7 was reintroduced, was assessed by staining as indicated with Calcofluor, Aniline Blue, and concanavalin A-FITC. Cells were washed with methanol and acetone to permeabilize the plasma membrane and allow the intracellular cell wall structures to be stained.

Similarities between the Effects of sur7Δ and caspofungin

To gain insight into the pleotropic effects of the sur7Δ mutant, microarray analysis of gene expression was carried out to determine which gene pathways are affected (Table 2 and Supplementary Table). Nine of the 22 genes that were induced more than fivefold in the sur7Δ mutant relative to a control strain are predicted to encode cell wall–related proteins, including five glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins that should localize to the cell wall (ECM331, PGA23, PGA13, RBR1, and PGA31). The CHT2 chitinase gene was repressed more than fivefold. Interestingly, the overall expression profile of the sur7Δ mutant shows significant overlap with the genes that are induced or repressed in response to caspofungin, an antifungal drug that blocks β-glucan synthase from forming the major β-1,3-glucan component of the cell wall. The changes in gene expression caused by caspofungin vary, depending on the conditions used. However, a core set of caspofungin-responsive genes was identified by comparing different data sets (Bruno et al., 2006). Of the 23 genes that were induced more than or equal to twofold in the caspofungin core response, 17 genes were also induced more than or equal to twofold in the sur7Δ cells (Supplementary Table). This included 11 of the 12 most highly induced genes in the caspofungin core response; most differences involved genes that were only weakly induced by caspofungin (less than threefold).

Table 2.

Genes whoses expression is altered ≥5-fold in sur7Δ cells

| ORF designation | Gene name | Fold change | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| orf19.4082 | DDR48 | 43.2 | Stress-associated protein, DNA repair |

| orf19.4255 | ECM331 | 26.1 | Putative GPI-anchored protein |

| orf19.6420 | PGA13 | 19.3 | Putative GPI-anchored protein |

| orf19.3740 | PGA23 | 18.4 | Putative GPI-anchored protein |

| orf19.2125 | 13.6 | ||

| orf19.2060 | SOD5 | 13.2 | Superoxide dismutase |

| orf19.4477 | CSH1 | 13.0 | Member of aldo-keto reductase family |

| orf19.4688 | DAG7 | 12.6 | a-specific transcription, α-factor induced |

| orf19.756 | SAP7 | 11.2 | Secreted aspartyl proteinase |

| orf19.6202 | RBT4 | 11.1 | Similar to plant pathogenesis–related protein |

| orf19.5302 | PGA31 | 9.6 | Putative GPI-anchored protein |

| orf19.4279 | MNN1 | 9.1 | Putative α-1,3-mannosyltransferase |

| orf19.3548.1 | WH11 | 8.5 | Cytoplasmic protein expressed in white phase |

| orf19.24 | RTA2 | 7.7 | Stress-associated protein |

| orf19.535 | RBR1 | 7.0 | Putative GPI-anchored protein |

| orf19.1120 | FAV2 | 6.9 | Induced by mating factor in MTLa/MTLa opaque cells |

| orf19.675 | 6.5 | Similar to cell wall proteins | |

| orf19.2062 | SOD4 | 6.4 | Superoxide dismutase |

| orf19.6595 | RTA4 | 6.2 | Lipid transport to plasma membrane |

| orf19.251 | 5.4 | Putative cell wall protein | |

| orf19.5557 | MNN4-4 | 5.0 | Putative mannosyltransferase |

| orf19.909 | STP4 | 5.0 | Putative transcription factor |

| orf19.3895 | CHT2 | −5.3 | Chitinase, GPI anchor protein |

| orf19.4777 | DAK2 | −5.8 | Dihydroxyacetone kinase |

| orf19.111 | CAN2 | −5.9 | Putative amino acid permease |

| orf19.5305 | RHD3 | −7.0 | Putative GPI-anchored protein |

| orf19.2475 | PGA26 | −8.0 | Putative GPI-anchored protein |

| orf19.4450.1 | −10.0 | ||

| orf19.3707 | YHB1 | −21.8 | Nitric oxide dioxygenase |

Analysis of cells treated with Aniline Blue, a fluorescent dye that binds cell wall β-1,3-glucan, showed the expected staining of the extracellular cell wall layer in both wild-type and sur7Δ cells (Figure 7). Both the wild-type and mutant cells also stained with concanavalin A-FITC, which binds to mannoproteins in the cell wall. In contrast, Aniline Blue and concanavalin A failed to stain the internal cell wall growth that stained strongly with Calcofluor. Concanavalin A forms a ∼104-kDa tetramer that may not pass efficiently through the cell wall. However, differential staining with Aniline Blue is not likely because of its inability to pass through the cell wall, because it has a lower MW than Calcofluor (787 vs. 917 Daltons) or other commonly used cell stains (e.g., rhodamine-phalloidin MW is ∼1306 Daltons). Thus, the unusual cell wall synthesis observed in the sur7Δ mutant appears to be enriched in chitin. The unusual chitin synthesis in the sur7Δ mutant is therefore similar to the increased chitin synthesis that occurs at septa in C. albicans cells treated with a sublethal dose of caspofungin (Walker et al., 2008). Furthermore, caspofungin treatment causes delocalization of septins in C. albicans similar to what is observed in the sur7Δ mutant (Aaron Mitchell, personal communication). Thus, the phenotypes of the sur7Δ mutant share several similarities to the inhibition of β-glucan synthesis.

The sensitivity of the sur7Δ mutant to caspofungin and two other commonly used antifungal drugs, amphotericin and fluconazole, was analyzed using Etest strips (Figure 8). The sur7Δ mutant showed only a slight increase in sensitivity to caspofungin (less than or equal to twofold), indicating that β-glucan synthase activity is not strongly impaired by mutation of SUR7. The sur7Δ mutant showed the same sensitivity as the wild-type strain for amphotericin, a polyene antibiotic that binds ergosterol and disrupts membrane integrity (Odds et al., 2003). In contrast, the sur7Δ mutant showed greatly increased sensitivity to fluconazole (about fivefold), a drug that blocks the Erg11 step of ergosterol synthesis (Odds et al., 2003). This raises the interesting possibility that drugs targeting Sur7 could enhance the sensitivity to fluconazole, which could be important in dealing with the emergence of drug resistant strains.

Figure 8.

Altered sensitivity of sur7Δ mutant to antifungal drugs. Etest strips were used to test the sensitivity to the indicated antifungal drug in the wild-type strain DIC185, the sur7Δ strain YJA11, and the sur7Δ mutant strain in which one copy of SUR7 was reintroduced (YJA12). Cells were spread on a plate containing RPMI 1640 medium, the Etest strip was applied, and then the plates were incubated at 37° for 48 h. The Etest strips release a gradient of drug causing a zone of growth inhibition. Note the increased sensitivity of the sur7Δ mutant to fluconazole.

Altered Hyphal Morphogenesis by sur7Δ Mutant

C. albicans cells were induced with serum to examine the role of Sur7 during hyphal morphogenesis. Wild-type cells induced in liquid culture with 10% serum formed narrow hyphae with long parallel walls. Although the majority of the sur7Δ cells induced with serum appeared to take on a filamentous morphology, the width of the hyphae was variable and many cells resembled pseudohyphae (Figure 9). Calcofluor staining showed that the initial hyphal cells formed by the sur7Δ cells did not contain the abnormal intracellular cell wall growth, but this could be observed in older hyphal cells after longer times of growth (not shown). When C. albicans cells were induced with the amino sugar N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), which is a weaker inducer of hyphal growth, the majority of sur7Δ cells were defective in forming hyphae and instead grew as enlarged rounded cells or pseudohyphae (Figure 9B). The hyphae formed by the sur7Δ cells were typically wider, consistent with a defect in highly polarized morphogenesis. In contrast, >95% of wild-type cells formed hyphae in response to GlcNAc. Filipin staining was used to assess the polarization of the plasma membrane in the hyphae, because this fluorescent polyene antibiotic preferentially stains the tips of wild-type hyphae (Martin and Konopka, 2004; Alvarez et al., 2007). Filipin binds ergosterol, suggesting that polarization of ergosterol occurs in this region or a distinct lipid composition that provides better access of filipin to ergosterol. Enriched filipin staining could be detected at the tips of the sur7Δ hyphal cells, although it was quite variable in intensity and usually not as bright as in wild-type cells (Figure 9B), consistent with a defect in cell polarization.

Figure 9.

Hyphal morphogenesis defects of sur7Δ mutant. (A) Calcofluor staining of hyphal cells induced with serum for 75 min. (B) Filipin staining of cells induced with 100 mM GlcNAc for 70 min to form hyphae. (C) Cells were spotted on solid medium agar plates containing 4% serum or 2.5 mM GlcNAc as indicated and grown for 7 d at 37°C, and then the plates were rinsed to remove surface growth and reveal invasive hyphal growth. The strains used were wild-type strain DIC185, sur7Δ strain YJA11, and the sur7Δ mutant strain in which one copy of SUR7 was reintroduced (YJA12).

Analysis of hyphal induction on solid medium agar plates revealed a defect in invasive growth for the sur7Δ mutant. Cells spotted on the surface of an agar plate were grown for 7 d, and then the surface growth was rinsed away to reveal invasive growth into the agar. The sur7Δ mutant formed filamentous growth into the agar, but the invasive zone was less than half as long as for the wild-type control cells on agar containing serum or GlcNAc as the inducer (Figure 9C).

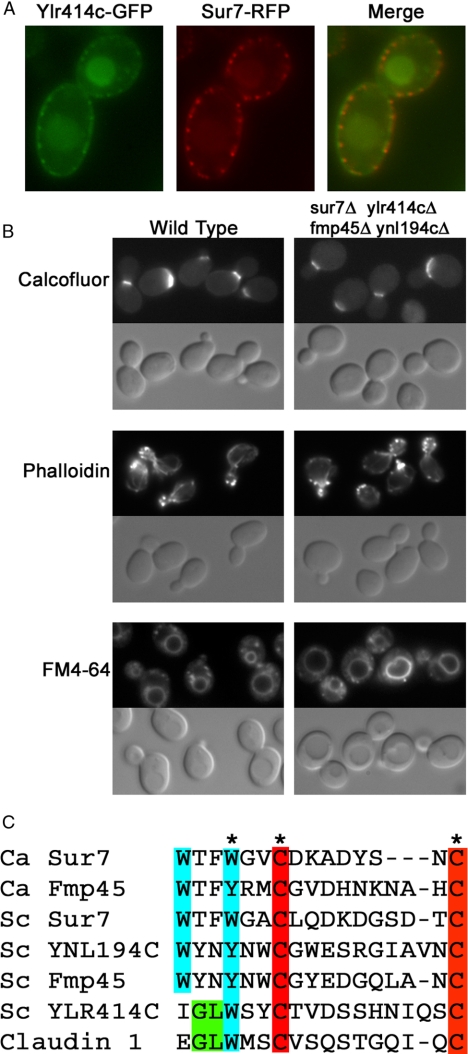

Analysis of SUR7-Homologous Genes in S. cerevisiae

Given the obvious phenotypes of the C. albicans sur7Δ mutant, we reexamined the failure to observe a strong phenotype for S. cerevisiae mutants lacking SUR7 and its paralogs. In contrast to C. albicans, which appears to only contain one SUR7 paralog (FMP45), S. cerevisiae has been reported to contain two other paralogs (FMP45 and YNL194C). The triple sur7Δ fmp45Δ ynl194cΔ mutant did not display strong defects (Young et al., 2002), so we searched for and found a fourth SUR7 paralog (YLR414C) in the S. cerevisiae genome. Consistent with this gene encoding a Sur7 paralog, a GFP-tagged version of the Ylr414c protein localized to punctate patches in the plasma membrane that showed extensive colocalization with Sur7-RFP (Figure 10A). This contrasts with a genome-wide study of protein localization that detected Ylr414c-GFP generally in the plasma membrane and cytoplasm (Huh et al., 2003). These previous results may have been affected by the very weak signal of Ylr414c-GFP relative to Sur7-GFP and other limitations of high throughput studies. Surprisingly, the quadruple S. cerevisiae mutant (sur7Δ fmp45Δ ynl194cΔ ylr414cΔ) showed only minor defects, such as a greater tendency to form rounded cells (Figure 10B). Chitin and actin localization appeared to be similar to wild type, as did endocytosis of the dye FM 4-64. Thus, either there are additional Sur7-related proteins in S. cerevisiae or there has been evolutionary divergence such that they are not needed in S. cerevisiae.

Figure 10.

YLR414C encodes a new Sur7 paralog in S. cerevisiae. (A) Colocalization of Ylr414c-GFP and Sur7-RFP to punctate membrane patches in S. cerevisiae. The YLR414c-GFP was constructed as part of a genome-wide analysis of protein localization (Huh et al., 2003). (B) The function of a new SUR7-related gene, YLR414C, was tested by constructing a quadruple deletion mutant (sur7::kanR ylr414c::HIS3 fmp45::LEU2 ynl194c::URA3) in S. cerevisiae. The mutant cells were compared with the wild-type control (BY4741) for staining with Calcofluor (chitin), rhodamine-phalloidin (actin), and FM 4-64 (endocytosis). FM 4-64 was allowed to internalize for 30 min before recording the image. (C) Multiple sequence alignment of the region surrounding the Cys-containing motif in extracellular domain 1 of Sur7 and human claudin proteins. Complete multiple sequence alignment of a larger set of fungal Sur7-related proteins is shown in Supplementary Figure S1 and an evolutionary tree of their relatedness is shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

Ylr414c displays low overall sequence identity with Sur7 (∼20%), but contains four TMDs spaced at intervals similar to Sur7 and the other paralogs. The Ylr414c protein also contains most of the highly conserved residues that are present in other Sur7-homologous proteins from a broad range of fungal species (Supplementary Figure S1). In particular, Ylr414c contains a cysteine motif in the middle of the first extracellular loop that is highly conserved in other Sur7 family proteins (Figure 10C). This consensus sequence, WxxW/YxxC(7–10 aa)C, is very similar to the conserved motif found in the similar position of extracellular loop 1 of the claudin family of plasma membrane proteins, GLWxxC(8–10 aa)C (Van Itallie and Anderson, 2004). The claudin proteins are also similar to Sur7 in that they contain four TMDs. Members of the claudin family form special plasma membrane domains in animal cells, such as tight junctions (Van Itallie and Anderson, 2004; Furuse and Tsukita, 2006). Similarity between Sur7 and the broader family of claudin/PMP-22/EMP/MP20 proteins has significant implications for understanding the role of these plasma membrane proteins from yeast to humans (see Discussion).

DISCUSSION

The plasma membrane forms an important barrier that is also involved in dynamic processes, such as interfacing with the extracellular environment, morphogenesis, and cell wall biogenesis. In addition, most pharmaceutical drugs, including antifungal drugs, affect plasma membrane components. In spite of its importance, plasma membrane structure is not well understood because of technical limitations because of its hydrophobicity. However, recent studies have begun to identify specialized subdomains that include lipid rafts and protein domains. Therefore, the role of Sur7 was analyzed in this study because it has been localized in S. cerevisiae to membrane patches termed eisosomes or MCC (Young et al., 2002; Malinska et al., 2003). Sur7 was implicated in endocytosis in S. cerevisiae based on its localization to eisosomes (Walther et al., 2006) and its ability to partially suppress the defects of an rvs167 mutant when overproduced (Sivadon et al., 1997). Surprisingly, mutational analysis of SUR7 and its paralogs in S. cerevisiae have not identified strong phenotypes (Young et al., 2002). In contrast, analysis of a C. albicans sur7Δ mutant revealed a wide range of phenotypes including mislocalization of actin and septins and also defects in endocytosis, morphogenesis, and cell wall growth. Thus, the analysis of SUR7 in C. albicans further broadens the range of eisosome functions.

Sur7 Prevents Abnormal Intracellular Growth of Cell Wall in C. albicans

Of all the phenotypes displayed by the sur7Δ mutant, the most surprising was the intracellular growth of cell wall material. To our knowledge, such extensive ectopic cell wall growth has not been reported previously. The intracellular wall growth in the Ca-sur7Δ mutant was frequently in the shape of an elongated rod, with one end emanating from the cell cortex (Figure 6 and Supplementary Movie). EM analysis suggested that the rods are typically hollow, as evidenced by the appearance of rings of wall material in thin sections (Figure 5). In some cases there were also wide sheets of wall growth within the cell (Figures 6 and 7 and Supplementary Movie). Other types of abnormal wall growth were also observed, including variations in cell wall width, and septa that were unusually thick and misshapen. Comparison of cells with different amounts of intracellular cell wall material suggested that the abnormal wall growth initiated with convolution of the plasma membrane that resulted in inward growth of the outer cell wall into the cytoplasm. Continued growth of these structures apparently forms the elongated structures seen in the Ca-sur7Δ mutant.

The internal cell wall material stained prominently with Calcofluor, but not Aniline Blue, indicating that it is chitin-rich. Elevated chitin synthesis has been reported previously in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans as a compensatory response to cell wall damage (Garcia-Rodriguez et al., 2000; Smits et al., 2001; Walker et al., 2008). For example, treatment of C. albicans with sublethal doses of a β-glucan synthase inhibitor, caspofungin, induces increased chitin synthesis that rescues viability by forming unusually thick, chitin rich septa (Walker et al., 2008). These results suggest that the abnormal wall synthesis seen in the sur7Δ mutant is due to activation of chitin synthesis as part of a compensatory pathway. Consistent with this, sur7Δ cells share two other similarities with caspofungin-treated cells. One is the mislocalization of septins to ectopic sites (Figure 5 and Aaron Mitchell, personal communication). Abnormal septin localization was also seen in fks1Δ S. cerevisiae cells that are partially deficient in β-1,3-glucan synthase activity (Garcia-Rodriguez et al., 2000). In addition, the sur7Δ mutant and cells treated with caspofungin show similar changes in gene expression. Eleven of the twelve genes that are most highly induced in the core caspofungin response were also induced in the sur7Δ mutant. In addition, the CHT2 chitinase gene was repressed in both conditions. The more extensive cell wall synthesis seen in the sur7Δ mutant but not in cells treated with sublethal doses of caspofungin could be due to the different types of cell wall damage or to the fact that sur7Δ mutants induce additional genes related to cell wall function that are not part of the caspofungin Core response, such as genes that encode GPI-anchored proteins (PGA13 and PGA31) and mannosyltransferases (MNN1 and MNN4-4).

The similarities between the sur7Δ mutant and cells treated with caspofungin raise the possibility that Sur7 is needed for proper function of β-glucan synthase. Previous studies have also suggested a link between eisosomes and cell wall synthesis. A chemically modified echinocandin inhibitor of cell wall β-1,3-glucan synthesis was cross-linked to C. albicans Pil1, and in a high-throughput study of the S. cerevisiae proteome the Fks1 subunit of β-1,3-glucan synthase was found in a complex with Pil1 (Radding et al., 1998; Gavin et al., 2002; Odds et al., 2003; Edlind and Katiyar, 2004). However, it is not clear that Sur7 plays a major role in the regulation of β-glucan synthase. The sur7Δ mutant was only slightly more sensitive to caspofungin (less than twofold), and the cell wall β-glucan stained evenly with Aniline Blue, suggesting that the loss of Sur7 does not cause an overall defect in β-glucan synthase activity. Perhaps Sur7 plays a role in the spatial or temporal regulation of cell wall synthesis. Alternatively, the absence of Sur7 may only cause a similar stress response, and Sur7 may not directly affect β-glucan synthase activity. In this case Sur7 may be needed to act as a scaffold to recruit cell wall regulators such as the Pkh1/2 kinases, and in the absence of Sur7 a signal is induced that mimics cell wall damage, leading to activation of a compensatory pathway.

The mislocalization of septins to ectopic sites away from the bud neck in the sur7Δ mutant is likely to be directly involved in the abnormal morphogenesis and cell wall synthesis (Figure 5). Septin localization in wild-type cells is tightly restricted to the bud neck, where the septins form a ring on the inner surface of the plasma membrane that carries out several functions (Gladfelter et al., 2001; Douglas et al., 2005; Gladfelter, 2006). One is to act as a barrier that restricts actin patches and plasma membrane proteins to the bud (Barral et al., 2000; Takizawa et al., 2000). Thus, abnormal septin ring function could help contribute to the mislocalization of actin seen in sur7Δ mutants. Another important septin function is to recruit chitin synthase to the bud neck. This suggests that septins present at ectopic sites could act to nucleate cell wall growth at these sites away from the bud neck. In support of the link between altered septin localization and intracellular wall growth, certain S. cerevisiae septin mutants and a cla4Δ mutant, which is a regulator of septins, display ectopic cell wall growth that is similar to the spikes of wall growth seen in the sur7Δ mutant (Roh et al., 2002; Schmidt et al., 2003).

Role of Sur7 in Endocytosis

The sur7Δ mutant was partially defective in endocytosis, but surprisingly there was only a slight lag in internalization of the FM 4-64 dye from the plasma membrane. The more pronounced defect was a delay in vesicles trafficking to the vacuole (Figure 2). Because Sur7 is present at the plasma membrane, it seems likely that this latter defect was an indirect effect, perhaps caused by the mislocalization of actin or other components. Previous studies raised the possibility that Sur7 might act as a scaffold for the formation of eisosomes by interacting with the cytoplasmic Pil1 and Lsp1 proteins in S. cerevisiae (Walther et al., 2006; Grossmann et al., 2007). It was therefore surprising that Lsp1-GFP still localized to punctate patches in the C. albicans sur7Δ mutant. This indicates that other factors regulate the formation of these clusters and their recruitment to the plasma membrane.

S. cerevisiae Sur7 Family Members

In view of the strong phenotypes displayed by the C. albicans sur7Δ mutant, it was surprising that in S. cerevisiae a triple deletion of SUR7 and two paralogous genes caused only mild defects in sporulation and a change in sphingolipid species (Young et al., 2002). We identified an additional Sur7 paralog (YLR414C) that also localized to punctate patches in the plasma membrane (Figure 10) and is reportedly induced by cell wall damage (Rodriguez-Pena et al., 2005). However, the S. cerevisiae quadruple mutant (sur7Δ, fmp45D, ynl194cΔ, ylr414cΔ) showed only a slight defect in morphology and did not display an obvious cell wall defect. Perhaps the roles for Sur7 have diverged in different fungal species or that there are yet other SUR7-related genes in S. cerevisiae. Homology searches detected only two Sur7-related proteins encoded in the C. albicans genome (Ca-Sur7 and Ca-Fmp45). Ca-FMP45 was not highly expressed in microarray analysis of gene expression of either wild type or the sur7Δ mutant. Thus, C. albicans may be more dependent on SUR7 than S. cerevisiae.

Sur7 Protein Family

Alignment of fungal Sur7 proteins revealed a conserved Cys-containing motif WxxW/YxxC(7–10 aa)C present in the middle of extracellular loop 1 between TMDs 1 and 2 (Figure 10C and Supplementary Figure S1). A similar GLWxxC(8–10 aa)C motif is present in extracellular loop 1 of the claudin family of proteins that also contain four TMDs (Van Itallie and Anderson, 2004; Furuse and Tsukita, 2006), suggesting that there are important structural and functional similarities between Sur7 and claudin proteins. The claudin proteins associate to form tight junctions in animal cells, which are specialized membrane barrier domains (Anderson et al., 2004). The GLWxxC(8–10 aa)C motif is also present in a broader range of plasma membrane proteins (pfam00822) that are all thought to function in part by interacting with other membrane proteins (Van Itallie and Anderson, 2004, 2006).

The conserved Cys motif in extracellular loop 1 helped to reveal the new Sur7 paralog in S. cerevisiae (Ylr414c). Interestingly, Ylr414c contains a Cys-consensus motif in extracellular loop 1 that is an exact match to the claudin motif (Figure 10C). Ylr414c is also the Sc-Sur7 family member that is most similar to the only Sur7-family protein detected in S. pombe and in the more divergent Basidiomycete fungi (Supplementary Figure S2).

A distinct Cys-containing motif, GxxGxC(8–20 aa)C, was found in the Fig1 family of fungal proteins that also contain four TMDs (Zhang et al., 2006). S. cerevisiae Fig1 is induced by mating pheromone and functions in a low-affinity calcium uptake system, cell fusion during mating, and in mating pheromone-induced cell death (Muller et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2006). Fig1 localizes the plasma membrane, but is not detected in punctate patches.

The Sur7, Fig1, and claudin proteins differ structurally from the tetraspanins, which comprise another major family of proteins with four TMDs. Tetraspanins contain only a small first extracellular loop and a larger second extracellular loop with a distinct type of Cys-containing motif (Hemler, 2005). The Cys residues in the tetraspanin motif form disulfide bonds, and it is therefore predicted that the Cys residues in the consensus sequence in the Sur7, Fig1, and claudin proteins also form disulfide bonds. Tetraspanins are thought to recruit other proteins to specialized membrane domains and affect a wide range of processes in animal cells including signal transduction, cell adhesion, and formation of membrane microdomains (Hemler, 2005). There are yet other families of proteins that also contain four TMDs, including the connexins and occludins. Thus, recognition of the common functional and structural features of the various types of membrane proteins with four TMDs should help to define their plasma membrane function in a wide range of cell types from yeast to humans.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Aaron Mitchell (Carnegie Mellon University), Judith Berman (University of Minnesota), Amy Warenda (Stony Brook University), Aaron Neiman (Stony Brook University), Linda Huang (University of Massachusetts, Boston), and Lucas Carey (Stony Brook University) for strains and plasmids. We also thank Drs. Aaron Neiman and Deborah Brown (Stony Brook University) for advice. This work was supported by Grant RO1 AI47837 from the National Institutes of Health to J.B.K.

Abbreviations used:

- MCC

membrane compartment occupied by Can1

- TMD

transmembrane domain.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0479) on September 17, 2008.

REFERENCES

- Adams A.E.M., Pringle J. R. Staining of actin with fluorochrome-conjugated phalloidin. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:729–731. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94054-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez F. J., Douglas L. M., Konopka J. B. Sterol-rich plasma membrane domains in fungi. Eukaryot. Cell. 2007;6:755–763. doi: 10.1128/EC.00008-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez F. J., Konopka J. B. Identification of an N-acetylglucosamine transporter that mediates hyphal induction in Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:965–975. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. M., Van Itallie C. M., Fanning A. S. Setting up a selective barrier at the apical junction complex. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral Y., Mermall V., Mooseker M. S., Snyder M. Compartmentalization of the cell cortex by septins is required for maintainence of cell polarity in yeast. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:841–851. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. A., London E. Structure and function of sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich membrane rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17221–17224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown V., Sexton J. A., Johnston M. A glucose sensor in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2006;5:1726–1737. doi: 10.1128/EC.00186-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno V. M., Kalachikov S., Subaran R., Nobile C. J., Kyratsous C., Mitchell A. P. Control of the C. albicans cell wall damage response by transcriptional regulator Cas5. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e21. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson R. C. Thematic Review Series: Sphingolipids. New insights into sphingolipid metabolism and function in budding yeast. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:909–921. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800003-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson R. C., Sumanasekera C., Lester R. L. Functions and metabolism of sphingolipids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Prog. Lipid Res. 2006;45:447–465. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas L. M., Alvarez F. J., McCreary C., Konopka J. B. Septin function in yeast model systems and pathogenic fungi. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:1503–1512. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.9.1503-1512.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlind T. D., Katiyar S. K. The echinocandin “target” identified by cross-linking is a homolog of Pil1 and Lsp1, sphingolipid-dependent regulators of cell wall integrity signaling. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4491. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4491.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M., Tsukita S. Claudins in occluding junctions of humans and flies. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rodriguez L. J., Trilla J. A., Castro C., Valdivieso M. H., Duran A., Roncero C. Characterization of the chitin biosynthesis process as a compensatory mechanism in the fks1 mutant of. Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2000;478:84–88. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01835-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin A. C., et al. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature. 2002;415:141–147. doi: 10.1038/415141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerami-Nejad M., Berman J., Gale C. A. Cassettes for PCR-mediated construction of green, yellow, and cyan fluorescent protein fusions in Candida albicans. Yeast. 2001;18:859–864. doi: 10.1002/yea.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladfelter A. S. Control of filamentous fungal cell shape by septins and formins. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:223–229. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladfelter A. S., Pringle J. R., Lew D. J. The septin cortex at the yeast mother-bud neck. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2001;4:681–689. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(01)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein A. L., Pan X., McCusker J. H. Heterologous URA3MX cassettes for gene replacement in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1999;15:507–511. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199904)15:6<507::AID-YEA369>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann G., Opekarova M., Malinsky J., Weig-Meckl I., Tanner W. Membrane potential governs lateral segregation of plasma membrane proteins and lipids in yeast. EMBO J. 2007;26:1–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler M. E. Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:801–811. doi: 10.1038/nrm1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh W. K., Falvo J. V., Gerke L. C., Carroll A. S., Howson R. W., Weissman J. S., O'Shea E. K. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M. S., Bi E. Regulation of septin organization and function in yeast. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., 3rd, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G., Gruhler A., Liu Y., Jensen O. N., Dickson R. C. The sphingolipid long-chain base-Pkh1/2-Ypk1/2 signaling pathway regulates eisosome assembly and turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:10433–10444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709972200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinska K., Malinsky J., Opekarova M., Tanner W. Visualization of protein compartmentation within the plasma membrane of living yeast cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:4427–4436. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinska K., Malinsky J., Opekarova M., Tanner W. Distribution of Can1p into stable domains reflects lateral protein segregation within the plasma membrane of living S. cerevisiae cells. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:6031–6641. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. W., Konopka J. B. Lipid raft polarization contributes to hyphal growth in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2004;3:675–684. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.3.675-684.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller E. M., Mackin N. A., Erdman S. E., Cunningham K. W. Fig1p facilitates Ca2+ influx and cell fusion during mating of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:38461–38469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada C., Ritchie K., Oba Y., Nakamura M., Hotta Y., Iino R., Kasai R. S., Yamaguchi K., Fujiwara T., Kusumi A. Accumulation of anchored proteins forms membrane diffusion barriers during neuronal polarization. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:626–632. doi: 10.1038/ncb1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odds F. C., Brown A. J., Gow N. A. Antifungal agents: mechanisms of action. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:272–279. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(03)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle J. R. Staining of bud scars and other cell wall chitin with calcofluor. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:732–735. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94055-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radding J. A., Heidler S. A., Turner W. W. Photoaffinity analog of the semisynthetic echinocandin LY 303366, identification of echinocandin targets in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1187–1194. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Pena J. M., Perez-Diaz R. M., Alvarez S., Bermejo C., Garcia R., Santiago C., Nombela C., Arroyo J. The ‘yeast cell wall chip’—a tool to analyse the regulation of cell wall biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology. 2005;151:2241–2249. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27989-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh D. H., Bowers B., Schmidt M., Cabib E. The septation apparatus, an autonomous system in budding yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:2747–2759. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M., Varma A., Drgon T., Bowers B., Cabib E. Septins, under Cla4p regulation, and the chitin ring are required for neck integrity in budding yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:2128–2141. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivadon P., Peypouquet M. F., Doignon F., Aigle M., Crouzet M. Cloning of the multicopy suppressor gene SUR7: evidence for a functional relationship between the yeast actin-binding protein Rvs167 and a putative membranous protein. Yeast. 1997;13:747–761. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970630)13:8<747::AID-YEA137>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits G. J., van den Ende H., Klis F. M. Differential regulation of cell wall biogenesis during growth and development in yeast. Microbiology. 2001;147:781–794. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-4-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudbery P., Gow N., Berman J. The distinct morphogenic states of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa P. A., DeRisi J. L., Wilhelm J. E., Vale R. D. Plasma membrane compartmentalization in yeast by messenger RNA transport and a septin diffusion barrier. Science. 2000;290:341–344. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toret C. P., Drubin D. G. The budding yeast endocytic pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:4585–4587. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Itallie C. M., Anderson J. M. The molecular physiology of tight junction pores. Physiology. 2004;19:331–338. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00027.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Itallie C. M., Anderson J. M. Claudins and epithelial paracellular transport. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2006;68:403–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.131404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vida T. A., Emr S. D. A new vital stain for visualizing vacuolar membrane dynamics and endocytosis in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1995;128:779–792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L. A., Munro C. A., de Bruijn I., Lenardon M. D., McKinnon A., Gow N. A. Stimulation of chitin synthesis rescues Candida albicans from echinocandins. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000040. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther T. C., Aguilar P. S., Frohlich F., Chu F., Moreira K., Burlingame A. L., Walter P. Pkh-kinases control eisosome assembly and organization. EMBO J. 2007;26:4946–4955. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther T. C., Brickner J. H., Aguilar P. S., Bernales S., Pantoja C., Walter P. Eisosomes mark static sites of endocytosis. Nature. 2006;439:998–1003. doi: 10.1038/nature04472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warenda A. J., Konopka J. B. Septin function in Candida albicans morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:2732–2746. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. B., Davis D., Enloe B. M., Mitchell A. P. A recyclable Candida albicans URA3 cassette for PCR product-directed gene disruptions. Yeast. 2000;16:65–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(20000115)16:1<65::AID-YEA508>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. B., Davis D., Mitchell A. P. Rapid hypothesis testing with Candida albicans through gene disruption with short homology regions. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:1868–1874. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1868-1874.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M. E., Karpova T. S., Brugger B., Moschenross D. M., Wang G. K., Schneiter R., Wieland F. T., Cooper J. A. The Sur7p family defines novel cortical domains in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, affects sphingolipid metabolism, and is involved in sporulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:927–934. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.3.927-934.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanolari B., Raths S., Singer-Kruger B., Riezman H. Yeast pheromone receptor endocytosis and hyperphosphorylation are independent of G protein-mediated signal transduction. Cell. 1992;71:755–764. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90552-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N. N., Dudgeon D. D., Paliwal S., Levchenko A., Grote E., Cunningham K. W. Multiple signaling pathways regulate yeast cell death during the response to mating pheromones. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:3409–3422. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.