Abstract

NF-Y binds to CCAAT motifs in the promoter region of a variety of genes involved in cell cycle progression. The NF-Y complex comprises three subunits, NF-YA, -YB, and -YC, all required for DNA binding. Expression of NF-YA fluctuates during the cell cycle and is down-regulated in postmitotic cells, indicating its role as the regulatory subunit of the complex. Control of NF-YA accumulation is posttranscriptional, NF-YA mRNA being relatively constant. Here we show that the levels of NF-YA protein are regulated posttranslationally by ubiquitylation and acetylation. A NF-YA protein carrying four mutated lysines in the C-terminal domain is more stable than the wild-type form, indicating that these lysines are ubiquitylated Two of the lysines are acetylated in vitro by p300, suggesting a competition between ubiquitylation and acetylation of overlapping residues. Interestingly, overexpression of a degradation-resistant NF-YA protein leads to sustained expression of mitotic cyclin complexes and increased cell proliferation, indicating that a tight regulation of NF-YA levels contributes to regulate NF-Y activity.

INTRODUCTION

The CCAAT-binding transcription factor NF-Y is a heteromeric protein composed of three subunits, NF-YA, -YB, and -YC, all necessary for CCAAT binding (Mantovani, 1999). The NF-Y complex supports the basal transcription of a class of regulatory genes responsible for cell cycle progression, among which are mitotic cyclin complexes (Zwicker et al., 1995a,b; Bolognese et al., 1999; Farina et al., 1999; Korner et al., 2001; Gurtner et al., 2003, 2008; Di Agostino et al., 2006). Knock-out mice clearly demonstrates that NF-Y dependent transcription is essential during early mouse development (Bhattacharya et al., 2003). The NF-Y function in proliferation is also demonstrated by the inhibition of DNA binding by endogenous NF-Y, resulting in retardation of fibroblast growth, which is brought about by overexpression of a dominant negative mutant of the NF-YA subunit (Hu and Maity, 2000). The differential expression of NF-YA, altering NF-Y CCAAT-binding activity, has been observed in several cell lines and tissues both during cell cycle progression and under specific conditions. NF-YA expression is modulated during the cell cycle, being high in G1, further increasing in S, and then decreasing in the G2/M phase (Bolognese et al., 1999). Reduction of NF-YA expression has been reported in IMR-90 fibroblasts after serum deprivation (Chang et al., 1994) and in human monocytes (Marziali et al., 1997). The NF-YA protein is not expressed in terminally differentiated C2C12 muscle cells and adult skeletal muscle tissues (Farina et al., 1999; Gurtner et al., 2003, 2008). These observations show that levels of NF-YA dictate the function of the NF-Y complex. Interestingly, control of NF-YA accumulation is posttranscriptional, because NF-YA mRNA is relatively constant in growing and differentiated cells (Bolognese et al., 1999; Farina et al., 1999). Yet, the mechanisms regulating the stability of the NF-YA protein remain unknown.

The covalent addition of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein highly conserved among eukaryotes, is an increasingly common posttranslation modification that controls both the expression and the activity of numerous proteins in the eukaryotic cell (Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998; Ciechanover et al., 2000). The ubiquitin–proteasome pathway is composed of the ubiquitin-conjugating system and the 26S proteasome; the latter contains the multicatalytic protease complex (Hochstrasser, 1996; Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998; Thrower et al., 2000). Frequent targets of the ubiquitin modification machinery are transcription factors (Shcherbik and Haines, 2004). Indeed, many short-lived transcription factors such as E2F-1 (Hofmann et al., 1996; Hateboer et al., 1996), IkB (Chen et al., 1996), p53 (Scheffner et al., 1990), SMAD2 (Lo and Massagué, 1999; Zhu et al., 1999), c-Jun (Treier et al., 1994), and β-catenin (Aberle et al., 1997; Orford et al., 1997; Puca et al., 2008) are regulated by ubiquitylation. Most of them are unstable proteins whose rate of destruction mirrors their ability to activate transcription. The exact nature of how activation and destruction are linked is not yet clear (Collins and Tansey, 2006; Kodadek et al., 2006).

Acetylation is a dynamic posttranslational modification of lysine residues. Proteins with intrinsic histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity act as transcriptional coactivators by acetylating histones and thereby induce an open chromatin conformation, which allows the transcriptional machinery to access promoters. In addition to histones, some coactivators, such as p300/CBP and the P300/CBP–associated factor (PCAF), also targets transcription factors, influencing different aspects of their function (Sterner and Berger, 2000; Chan and La Thangue, 2001). An important level of regulation links acetylation levels and NF-Y activity. Functionally, inhibition of HDAC's activity by trichostatin A (TSA) treatment leads to 1) activation of the MDR1 (multidrug resistance promoter; Jin and Scotto, 1998); 2) a dramatic increase in the activity of TGF-β II receptor promoter (Park et al., 2002); and 3) activation of the HSP70 promoter in the absence of heat shock in Xenopus oocytes (Li et al., 1998). All these effects are strictly dependent on the presence of the CCAAT boxes. NF-Y interacts with hGCN5 (Currie, 1998), and NF-YB is acetylated in Xenopus by p300, but the consequences of this modification have not been addressed (Li et al., 1998). In vivo studies by chromatin immunoprecipitation on cell cycle–regulated promoters highlighted the dynamic behavior of NF-Y and HATs binding during cell cycle progression (Caretti et al., 2003; Salsi et al., 2003; Di Agostino et al., 2006).

Because of the role of ubiquitylation and acetylation in regulating the stability of several transcription factors, we investigated whether the NF-Y complex was subjected to these posttranslational modifications. In this report, we show for the first time that modulation of expression of one NF-Y subunit, NF-YA is mediated, at least in part, by the ubiquitin–proteasome degradation system. Treatment of cells with specific proteasome inhibitors leads to a significant increase of the endogenous NF-YA protein. Mutation of four lysines in the NF-YA C-terminal domain affects ubiquitylation, and the resulting protein is more stable than the wild-type form, indicating that these lysines are targeted by the ubiquitylation pathway. Two of these lysines are also target of p300 acetyl transferase activity in vitro. Our results indicate that a posttranslational molecular mechanism regulates the transcriptional activity of NF-Y controlling the stability of the regulatory subunit of the complex, NF-YA, and suggest that a competition exist between ubiquitylation and acetylation of common lysine residues of this protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture, DNA Transfections, and Treatments

Cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. The C2C12 differentiation protocol has been already described (Farina et al., 1999). Transient transfections in C2C12, HCT116, and NIH3T3 cells were carried out by the BES method according to the manufacturer's protocol. In each 60-mm plate, 1.5 × 105 cells were transfected with precipitates containing suitable concentrations of each reporter construct and of CMV β-galactosidase plasmid as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Treatments with peptide aldehydes proteasome inhibitors N-Ac-Leu-Leu-norleucinal (LLnL) were for 2, 4, or 8 h at the concentration of 50 μM, whereas those with Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-H (MG132) and N-acetyl-leucyl-leucyl-methioninal (LLM), were for 4 or 8 h at the concentration of 50 μM (All reagents were provided by Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

For measurement of protein half-life, cells were treated for 15 min and 2 and 3 h with cycloheximide (Chx, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) at the concentration of 100 μg/ml or with Chx and LLnL together at the concentration of 100 μg/ml and 50 μM, respectively. The drugs were directly added to culture medium. Cells were harvested after treatments and lysed. The intensity of each band was evaluated by densitometry using the NIH Image J 1.61 software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

The plasmids used in transfection experiments were: NF-YA and -YB eucaryotic expression vectors carrying the NF-YA and -YB open reading frame (ORF) under control of the SV40 promoter; the NF-YA green fluorescent protein (GFP) carrying a fusion protein between GFP and the NF-YA ORF under control of the SV40 promoter; and hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged ubiquitin (UbHA) carrying a fusion protein formed by an epitope of the HA and the entire open reading frame of the ubiquitin between the CMV enhancer and promoter and the SV40 polyadenylation signal (gift from Dirk Bohmann, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY). To generate NF-YA GFP mutant proteins (YA-R1, -R2, -R3, and -R2÷R3), we used the Quickchange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using appropriate primers on NF-YA GFP as template. Primer sequences will be available on request. In transfection assays, pcDNA3-p300 (gift from M. Levrero, University of Rome La Sapienza, Rome, Italy) was used. In cotransfection assays, pCCAAT-B2LUC and pmutCCAAT-B2LUC (Bolognese et al., 1999) were used. LUC activity was assayed on whole cell extract, as described (Brasier et al., 1989). The values were normalized for β-galactosidase and protein contents.

Assessment of Efficiency of Expression

The expression of NF-YA and YA-R1, -R2, and -R3, as GFP fusion proteins in Figure 5C, was quantified by counting 1000 cells from five different areas (320 × 240 μm) at 0, 8, 24, and 32 h after transfection in proliferating C2C12 transfected cells. The 0-h sample represents cells reseeded after an overnight transfection and harvested immediately after attachment.

Figure 5.

Identification of NF-YA lysine residues targets for ubiquitylation. (A) Schematic representation of the C-terminus domain of the NF-YA protein containing six lysine residues conserved across species. (B) Schematic representation of NF-YA protein with the positions of the lysines replaced in the different NF-YA mutants used in this work. (C) Number of GFP-positive cells in cell populations transfected with mutants (YA-R1, -R2, and YA-R3), wild-type NF-YA (NF-YA), or the empty vector as a control, at different times. (D) Time course of wild-type and mutants NF-YA expression by Western blot analysis on total extracts from cells nontransfected (NT) or transfected with mutants (YA-R1, -R2, and -R3) or wild-type NF-YA (NF-YA).

Immunolocalization of NF-YA-GFP Proteins

Cells (1 × 105) were seeded on 16-mm2 coverslips overnight and fixed the next day in 4% formaldehyde. Slides were mounted in 50% glycerol and analyzed within 24 h. Cells were counterstained with Hoechst for DNA labeling. Images were analyzed with a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (Axioskop 20; Thornwood, NY).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blots

Total, nuclear, and cytoplasmic extracts from C2C12 cells were prepared as previously described (Farina et al., 1999). Proteins were resolved on 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed according to the manufacturer's directions using the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal αNF-YA and -YB (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA), α cyclinB1, α cyclinA, α cdk1p34, αp300 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse monoclonal α NF-YA, a Hsp70 (StessGen Biotechnologies, San Diego, CA), α-tubulin (Calbiochem), α FK2 from Affiniti Research Products (Exeter, United Kingdom) and α-acetyl-Lys (Upstate Cell Signalling, Waltham, MA), rat monoclonal α HA (Sigma). Peroxidase activity of the appropriate secondary antibodies was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). For immunoprecipitations the following antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal α NF-YA (gift of R. Mantovani, University of Milano), rabbit polyclonal α NF-YB (Rockland Biosciences, Gilbertsville, PA) mouse monoclonal α FK2 (Affiniti), rat monoclonal α HA (Sigma), and mouse, rabbit or rat serum purified antibodies as control. Precleared extracts were incubated with protein A/G-Sepharose beads (Pierce, Rockford, IL) in lysis buffer containing 0.05% BSA and antibodies, under constant shaking at 4°C for 2 h. After incubation, Sepharose bead–bound immunocomplexes were rinsed with lysis buffer and eluted in 50 μl of SDS sample buffer for Western blotting and probed with α HA antibodies (Sigma). The ubiquitin ladder was quantified by measuring the signals of the bands by NIH Image 1.61 software.

Acetyltransferase Assay

Acetyltransferase assays were performed at 30°C, for 45 min using 1 μg of substrates, 50 ng of p300 or PCAF in 30 μl of assay buffer containing 10% glycerol, 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8), 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 10 mM sodium butyrate and 0.1 μCi of [3H]acetyl CoA (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA). The NF-YA, H3 and H4 proteins have been purified from inclusion bodies as previously described (Mantovani et al., 1992; Caretti et al., 1999). YA9 is an His-tag protein and it has been purified as previously described (Liberati et al., 1999; Zemzoumi et al., 1999). The thioredoxin (TRX) protein has been produced from pET-32b vector from Novagen (Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were run on 12 or 15% SDS polyacrylamide gels, stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250, treated with Amplify (Amersham), dried, and autoradiographed.

Elecrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

DNA-binding reactions of Figure 7B was performed in NDB-100/BSA with 0.2–0.7 and 2 ng of NF-Y. The oligonucleotides used in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were the cyclin B2 distal and middle CCAAT boxes described in Bolognese et al. (1999). Reactions were incubated for 20 min at room temperature and run in a 4.5% polyacrylamide gel (29:1 Acrylamide/Bis ratio) in 0.5× TBE at 4°C for 3 h.

Figure 7.

p300 acetylation of NF-YA in vitro. (A) In vitro acetylation by p300 of the NF-YA proteins outlined in the scheme. YA9 harbors only the highly conserved part of NF-YA. (B) EMSA analysis of wild-type NF-YA (NF-YA) and YA-R1, -R2, and -R3 mutants on a CCAAT-box containing oligonucleotide. A dose-response 0.1, 0.3, and 1 ng of purified NF-YAs was preincubated with recombinant NF-YB and -YC, 5 ng, and added to labeled DNA. (C) In vitro acetylation of recombinant purified NF-YA mutants by p300. In the bottom panel, Coomassie blue staining of the SDS gel is shown.

RT-PCR

Total RNA from C2C12 cells was extracted using the TRIzol RNA isolation system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer's instructions (M-MLV RT kit; Invitrogen). PCR was performed with HOT-MASTER Taq (Eppendorf, Fremont, CA) using 2 μl of cDNA reaction. PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide. The sequences of oligonucleotide primers were as follows: NFYA: F5′atcccagcagccagtttggcag, R5′gaaaaatcgtccaccttcaccacg; p300: F5′atgccacagccccctattgg, R5′gagacactggtgcttgaccg.

The housekeeping aldolase A mRNA, used as an internal standard, was amplified from the same cDNA reaction mixture using the following specific primers: F5′tggatgggctgtctgaacgctgt and R5′agtgacagcagggggcactgt.

Small Interfering RNA Transfection

Human HCT116 cells were seeded at a density of 1.6 × 106 in 100-mm culture dishes in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS. The next day, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions with 10 μl of 0.02 mM p300 small interfering RNA (siRNA; 5′-AAC CCC UCC UCU UCA GCA CCA-3′; Dharmacon Research, Boulder, CO), or nontargeting siRNA scramble (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) as a negative control.

Colony Formation Assay

NIH3T3 cells were cotransfected with wild-type NF-YA or its mutants (YA-R1, YA-R2, and YA-R3) and pBABE-PURO (10:1 ratio). The cells were selected in 2 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) at 48 h after transfection, and the colonies were stained and counted 2 wk later. Plates were stained with 0.5 ml of 0.005% Crystal Violet for >1 h, and colonies were counted using a dissecting microscope.

RESULTS

The Proteasome Pathway Regulates NF-YA Expression

To test the hypothesis that NF-Y is a direct target of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, NF-YA, -YB, and -YC protein levels were measured in cells treated with different peptide aldehydes proteasome inhibitors: N-acetyl-leucyl-leucyl-norleucinal (LLnL), Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-H (MG132), and N-acetyl-leucyl-leucyl-methioninal (LLM). Murine C2C12 muscle cells, myoblasts, were treated with 50 μM LLnL for 2, 4 and 8 h and the levels of NF-YA, -YB, and -YC in nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot (Figure 1A). After treatment, the NF-YA protein accumulated both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus, whereas the protein levels of NF-YB and -YC were only slightly modulated. We have previously demonstrated that in terminally differentiated C2C12 muscle cells, myotubes, NF-YA expression is abrogated (Farina et al., 1999; Gurtner et al., 2003, 2008). Thus, we asked whether regulation of NF-YA expression occurs at posttranslational level in this cell system. To this end, myotubes were treated with LLnL and levels of NF-YA, -YB, and -YC were analyzed. (Figure 1A). We observed an increase of NF-YA protein prevalently in the nucleus but also in the cytoplasm.

Figure 1.

The proteasome pathway regulates NF-YA expression. (A) Western blot analysis of endogenous NF-YA, -YB, and -YC in nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from myoblasts and myotubes treated with 50 μM LLnL for 2, 4, and 8 h. (B) Western blot analysis of the endogenous NF-YA, -YB, -YC, and p53 in nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from myoblasts treated with 50 μM LLM or MG132 for 4 and 8 h.

We tested two other compounds known to inhibit protein degradation, MG132 and LLM (Rock et al., 1994). In myoblasts, MG132 treatment led to an increase of NF-YA in the cytoplasm. In contrast LLM had no effect on NF-YA protein levels (Figure 1B). As a positive control, we analyzed p53 protein level in the same experimental conditions, and we observed that, as expected, it accumulated in the nuclear fraction after both treatments. Both LLnL and MG132 inhibit the proteasome pathway (Wang 1990), whereas LLM is a strong inhibitor of calpain and cathepsin but a very weak inhibitor of the proteasome (Rock et al., 1994). Thus, inhibition of proteasome, but not of a cysteine protease, pathway results in NF-YA accumulation (Figure 1B). Taken together, these results indicate that NF-YA expression is markedly regulated at posttranslational level. In contrast, the levels of the YB and YC subunits are slightly affected by the proteasome inhibitors, suggesting that the modulation of expression of the NF-YA subunit could dictate the activity of the NF-Y trimer.

The Half-Life of NF-YA Is Increased by Proteasome Inhibition

Because ubiquitin-mediated protein destruction has been mainly implicated for short-lived proteins, we sought to determine the half-life of NF-YA. C2C12 cells were incubated with Chx (100 μg/ml) for 15 and 30 min and 1, 2, or 3 h. As shown in Figure 2A, by densitometric analysis, the amount of NF-YA protein decreased by ∼50% after 2 h. In contrast to this, the steady-state levels of NF-YB were not modulated in the same experimental conditions, indicating that the half-life of these proteins is longer than 3 h.

Figure 2.

The half-life of NF-YA is increase by proteasome inhibition. (A) Densitometric analysis of the NF-YA or -YB as a control expression level after normalization against the values obtained for the control housekeeping gene tubulin under the same experimental conditions. (B) Western blot analysis of the endogenous NF-YA and -YB, in total extracts from C2C12 cells treated with 100 μg/ml Chx for various lengths of time and coincubated with 100 μg/ml Chx and 50 μM of LLnL. α-tubulin is used as loading control.

To further support the proteasome involvement in the degradation of the NF-YA subunit, its half-life was determined in the presence of LLnL. C2C12 cells were treated for 15 min or 2 or 3 h with both Chx and LLnL. As shown in Figure 2B, LLnL treatment prevented the Chx-induced decrease of NF-YA. As expected, NF-YB protein levels were not modulated. These results demonstrate that NF-YA degradation after Chx treatment is indeed mediated by the proteasome in C2C12 cells.

NF-YA Protein Is Ubiquitylated In Vivo

To determine the involvement of ubiquitylation in NF-YA degradation, a fusion protein formed by an epitope of the HA and the entire open reading frame of the UbHA (Treier et al., 1994) was cotransfected in C2C12 cells with a vector coding for NF-YA. Total cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with increasing amounts of anti-NF-YA antibody. Western blot analysis detected smeared high-molecular-weight species, characteristic of ubiquitylated proteins, both with anti-HA (Figure 3A) and anti-NF-YA (Figure 3B) antibodies. Increasing amounts of anti-NF-YA antibody immunoprecipitated increasing amount of these protein forms. Reciprocal immunoprecipitation experiments showed that NF-YA putative ubiquitylated forms are present in the smeared high-molecular-weight species immunoprecipitated with the anti-HA antibody (Figure 3C). These species were not detected in immunoprecipitates with control antibody. In the same experimental conditions, low levels of high-molecular-weight species were detected in extract immunoprecipitated with anti-NF-YB antibody from C2C12 cells cotransfected with vectors coding for NF-YB and UbHA, suggesting that this subunit is ubiquitylated to a lesser extent than NF-YA (Figure 3D). This result is in agreement with the minimal effect of LLnL on NF-YB protein levels shown above.

Figure 3.

Exogenous NF-YA protein is ubiquitylated in vivo. C2C12 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding NF-YA (A–C) or -YB (D) together with UbHA. Total extracts from these cells were immunoprecipitated with increasing amounts of anti-NF-YA (A and B), anti-HA (C) or anti-NF-YB antibodies (D). Western blot analysis was performed with an anti-HA antibody in (A and D) or anti NF-YA antibody (C and B). In all immunoprecipitation experiments an appropriate control antibody was used. Stars indicate the antibody chains used in the immunoprecipitations (IPs).

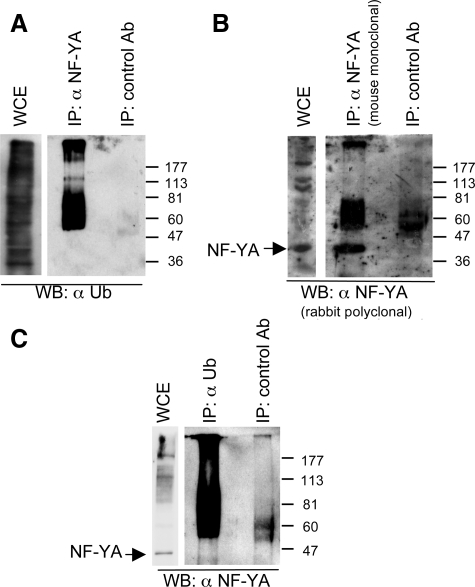

To determine whether the endogenous NF-YA protein is ubiquitylated, C2C12 cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-NF-YA mAb, and the precipitates were immunoblotted with an anti-ubiquitin antibody, FK2 (α Ub; Fujimuro and Yokosawa, 2005). A twin filter was immunoblotted with anti-NF-YA rabbit polyclonal antibody. As shown in Figure 4A, the FK2 antibody recognized a smeared ladder in the anti-NF-YA immunoprecipitates. This antibody does not recognize the 43-kDa NF-YA protein that correspond to the posttranslational unmodified form (Farina et al., 1999; Gurtner et al., 2003). A similar ladder and unmodified NF-YA protein were recognized by anti-NF-YA antibody (Figure 4B). In good agreement with this, reciprocal immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that anti-NF-YA antibody recognized a smeared ladder in the immunoprecipitates performed with FK2 antibody, indicating that the smeared ladder contains ubiquitylated NF-YA protein (Figure 4C). In both experiments, no protein ladder was detected in immunoprecipitates performed with the control antibody. Taken together, these data strongly indicate that both exogenous and endogenous NF-YA is ubiquitylated in vivo and suggest that the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway degrades it.

Figure 4.

Endogenous NF-YA protein is ubiquitylated in vivo. (A) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous NF-YA from total extracts from C2C12 cells with anti-NF-YA antibody and Western blot analysis with the ubiquitin-specific antibody FK2 (α Ub). (B) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous NF-YA from total extracts from C2C12 cells with mouse monoclonal anti-NF-YA antibody and Western blot analysis with the anti-NF-YA rabbit polyclonal antibody. (C) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous ubiquitylated proteins from total extracts from C2C12 cells with anti-FK2 antibody and Western blot analysis with anti-NF-YA antibody. In all immunoprecipitation experiments an appropriate control antibody was used. Stars indicate the antibody chains used in the immunoprecipitations (IPs).

Identification of NF-YA Lysine Residues Targets for Ubiquitylation

The C-terminus domain of NF-YA protein, containing the NF-YB/-YC interaction domain and the DNA-binding domain, is highly conserved from yeast to mammals. In particular, it contains six lysine residues conserved across the species (Figure 5A). Lysines K269, K276, and K283 are in the subunits interacting region, whereas lysines K289, K292, and K296 are in the linker. Because of their evolutionary conservation we asked whether these lysines could be target for ubiquitylation. To answer this question we derived three mutants YA-R1, YA-R2, and YA-R3 in the context of the full-length protein. In each of them two of these lysines were substituted with arginines (Figure 5B). Wild-type and mutant NF-YA were cloned in frame with GFP and overexpressed as GFP fusion proteins in C2C12 cells. As shown in Figure 5C, the number of GFP positive cells at the end of the time course is significantly higher in cell populations transfected with mutants than with wild-type NF-YA, suggesting that mutant proteins are more stable compared with wild type. Because GFP might influence the stability of fusion proteins we overexpressed wild-type and mutant NF-YA proteins not in frame with GFP in the same cells. As shown in Figure 5D, the stability of native mutant forms too is higher than that of wild-type NF-YA, Taken together, these results indicate that the mutant proteins are more stable compared with wild type, although the expression kinetics of the proteins is different in the two experiments (Figure 5, C and D). Moreover, the mutant proteins YA-R2 and -R3 are more stable than -R1, suggesting that the four lysines present in these constructs play a major role in NF-YA protein stability.

To investigate whether these lysines are target for ubiquitylation we generated a mutant protein in which all of them were substituted with arginines (Figure 5B). We transiently transfected C2C12 cells with either NF-YA wild-type protein (NF-YA) or mutant forms of it (YA-R1, -R2, -R3, and -R2÷R3). The YA-R2÷R3 mutant was more stable than wild-type NF-YA (Figure 6A) as well as the single YA-R2 and -R3 mutants (Figure 5D). Consistent with the higher stability of these proteins, we observed that formation of ubiquitylated NF-YA forms was partially inhibited on YA-R2, -R3, or -R2÷R3 mutants (Figure 6B). Interestingly, densitometric analysis indicated that the ubiquitin ladder of the YA-R2÷R3 mutant was inhibited by ∼70% (Figure 6C), whereas formation of ubiquitylated forms was essentially not inhibited in the YA-R1 mutant, in good agreement with its reduced stability (Figure 5D). We conclude that lysines K283, K289, K292, and K296 are those mainly ubiquitylated in the contest of the NF-YA protein.

Figure 6.

Identification of NF-YA lysine residues targets for ubiquitylation. (A) Western blot analysis on total cell extracts from nontransfected C2C12 cells (NT) and cells transfected with increasing amounts of plasmids encoding wild-type (NF-YA) or mutant NF-YA (NF-YA R2÷R3; see Figure 5B). (B) Total extracts from cells overexpressing wild-type or YA-R1, -R2, -R3, and -R2÷R3, immunoprecipitated with anti-NF-YA antibody, or mouse serum. Western blot analysis was performed with an anti-ubiquitin antibody FK2 (α Ub). In all immunoprecipitation experiments an appropriate control antibody was used. Stars indicate the antibody chains used in the immunoprecipitations (IPs). (C) Densitometric analysis of NF-YA ubiquitin ladder.

Two Ubiquitylated Lysines of NF-YA Are Targets of p300 Acetylation Activity

We have previously demonstrated that p300 interacts with NF-Y. Acetylated forms of NF-YA are present in the resulting complex, suggesting that p300 might regulate its acetylation status (Di Agostino et al., 2006). To investigate whether lysines target for ubiquitylation undergo p300-dependent acetylation, we used recombinant purified p300 and NF-YA in vitro acetylation studies (Figure 7A). As expected, p300 was able to self-acetylate and also acetylated recombinant full length NF-YA. Mapping the region acetylated by p300 using deletion mutant, we observed that the deletion mutant YA9, which contains all the ubiquitylated lysines, was acetylated in vitro by p300, clearly indicating that this conserved part of the protein is efficiently posttranslationally modified. As expected, the negative control, TRX, was not acetylated in the same experimental conditions. As positive control we analyzed the acetylation status of H3-H4 histones.

To investigate whether the lysines that undergo ubiquitylation could be target for p300 dependent acetylation, the three mutants YA-R1, -R2, and -R3 were used in in vitro acetylation studies. These mutants were first tested in EMSA: in dose-response experiments, all mutants were capable of binding DNA with the same efficiency of wild-type NF-YA (Figure 7B), a clear indication of normal interactions with the NF-YB/-YC subunits. Direct acetylations determined that YA-R2, and to a lesser degree YA-R1, were not efficiently acetylated by p300 (Figure 7C), whereas the mutant YA-R3 still underwent acetylation. We conclude that, in the contest of the NF-YA full-length protein, the two lysines 283 and 289 are the major targets of p300 acetylation activity. Of note, these two lysines are also ubiquitylated, suggesting a possible competition between acetylation and ubiquitylation on these residues.

p300 Expression Impacts on NF-YA Ubiquitylation

Theoretically, acetylation of specific lysines could increase the stability of a protein, because it would prevent ubiquitylation of the same lysine residues. To determine if p300 could affect the expression of NF-YA, C2C12 cells were transfected with p300. The amount of NF-YA was slightly increased in the presence of ectopic p300 (Figure 8A). We verified the presence of ubiquitylated NF-YA forms in lysates of C2C12 cells cotransfected with p300 and NF-YA. Consistent with the higher stability of the protein, we observed that formation of ubiquitylated NF-YA forms was inhibited in cells overexpressing p300 compared with no p300 (Figure 8B), suggesting that p300 acetylation of NF-YA could prevent, at least in part, its ubiquitylation. Next, we assessed the function of p300 in normal physiological settings, employing siRNA against p300. To this end, human HCT116 cells were transfected with an oligo pool directed against p300 (sip300; Gong et al., 2006) or, as control, an unrelated sequence (scramble), and incubated in the presence of Chx, which blocks de novo protein synthesis. Cellular extracts were prepared 2 h after Chx addition, and levels of NF-YA and p300 proteins were determined by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 8C, p300 loss did not alter NF-YA half-life in untreated cells. However, in the presence of Chx, the antibody against NF-YA detected high-molecular-weight species in cells interfered for p300, suggesting the presence of NF-YA putative ubiquitylated forms. Taken together, these results indicate that p300 could increase the stability of NF-YA, suggesting that its acetylation might enhance its expression, potentially by interfering with the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway.

Figure 8.

p300 expression impacts on NF-YA ubiquitylation. (A) Western blot analysis of NF-YA in total cell extracts from C2C12 cells transfected with p300. Actin was used as loading control. (B) C2C12 cells were transfected with wild-type NF-YA and increasing amounts of p300. Total extracts from these cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-NF-YA antibody and Western blot analysis with the ubiquitin-specific antibody, FK2 (α Ub). In immunoprecipitation experiments an appropriate control antibody was used. Stars indicate the antibody chains used in the IPs. (C) Western blot analysis of the endogenous NF-YA and p300 in total extracts from HCT116 cells treated with 100 μg/ml Chx for 2h and transfected with an oligo pool directed against p300 (sip300) or an unrelated sequence (scramble). Actin was used as loading control. (D) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of NF-YA and p300 expression on total RNA from C2C12 cells transfected with increasing amounts of p300. Aldolase was used as loading control. Ethidium bromide staining of total RNA is shown. Stars indicate the antibody chains used in the immunoprecipitations (IPs).

We asked whether p300-dependent increase of the NF-YA protein was also due, at least in part, to increased transcription of the NF-YA gene. To answer this question we performed semiquantitative RT-PCR assays (Figure 8D). The results demonstrate that the NF-YA mRNA level is not changed after p300 transfection. Therefore, we conclude that the stabilizing effect that p300 exerts over NF-YA is predominantly due to posttranslational events.

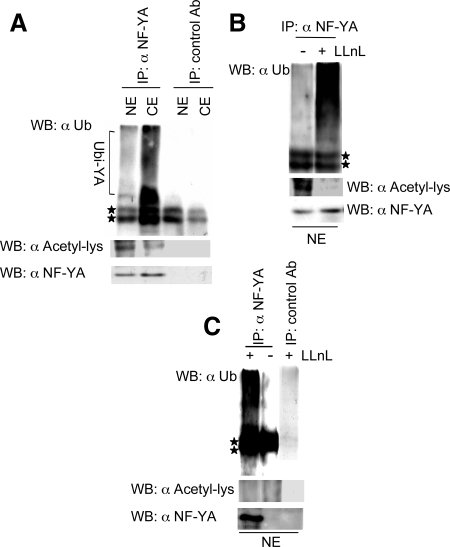

Acetylation and Ubiquitylation of NF-YA Protein in Pre- and Postmitotic Cells

To begin to investigate the functional relationship between acetylation and ubiquitylation of NF-YA, we analyzed the relative abundance of acetylated and ubiquitylated NF-YA species in nuclear and cytoplasmic cell compartments. For this purpose, C2C12 protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-NF-YA and subsequently blotted with FK2 and anti-acetyl-lysine antibodies (Figure 9A). We observed that the nuclear compartment contained higher levels of acetylated NF-YA protein in comparison to the cytoplasmic one. Conversely, ubiquitylated NF-YA forms were more abundant in the cytoplasm. Of note, a strong decrease in acetylation was observed if an artificial increase of ubiquitylated NF-YA forms was induced in the nucleus with LLnL treatment (Figure 9B). These results support the hypothesis that acetylated NF-YA protein, acting as a transcription factor in the nucleus, is the active form, whereas the nonactive ubiquitylated form is prevalently stored in the cytoplasm. If this hypothesis is correct, we would expect that in postmitotic cells, where we have previously demonstrated absence of NF-Y activity (Farina et al., 1999; Gurtner et al., 2003; Gurtner et al., 2008), only ubiquitylated NF-YA species are expressed. As already shown in Figure 1A, myotubes express NF-YA only after treatment with LLnL. Thus, nuclear extracts from myotubes treated with LLnL were immunoprecipitated with anti-NF-YA and subsequently blotted with FK2 and anti-acetyl-lysine antibodies. As shown in Figure 9C, only ubiquitylated NF-YA species were present in differentiated nuclei under these experimental conditions (Figure 9C). Taken together, these results determine that the nuclei of premitotic cells contain mainly acetylated NF-YA protein, whereas in postmitotic cells, where NF-Y does not exert its activity, the protein is only ubiquitylated.

Figure 9.

Acetylation and ubiquitylation of NF-YA protein in pre- and postmitotic cells. (A) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous NF-YA from nuclear (NE) and cytoplasmic (CE) extracts of myoblasts with anti-NF-YA antibody and Western blot analysis with ubiquitin-specific antibody FK2 (α Ub) and anti-acetyl-lysine (α Acetil-lys). (B) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous NF-YA from nuclear extracts of myoblasts after treatment with 50 μM of LLnL with anti-NF-YA antibody and Western blot analysis with α Ub and α Acetil-lys. (C) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous NF-YA from nuclear extracts of myotubes after treatment with 50 μM of LLnL with anti-NF-YA antibody and Western blot analysis with α Ub and α Acetil-lys. In all panels the amount of immunoprecipitated NF-YA has been measured by Western blot with an anti-NF-YA antibody. In all immunoprecipitation experiments an appropriate control antibody has been used. Stars indicate the antibody chains used in the immunoprecipitations (IPs).

Acetylation and Ubiquitylation of NF-YA Lysine Residues Are Involved in its Transcriptional Activity

We have shown that the NF-YA mutants are capable of binding DNA with the same efficiency of wild-type NF-YA (Figure 7B), suggesting that they might retain efficient transcriptional activity. To test this hypothesis, first we determined the cellular localization of the wild-type and mutant NF-YA proteins using the fluorescent properties of GFP. Analysis by fluorescence microscopy showed that GFP chimeras of mutants and wild-type NF-YA were all targeted to the nucleus (Figure 10A). On the basis of the ability of mutants to bind DNA in vitro and their nuclear localization in vivo, we investigated their ability to transactive a NF-Y target promoter. For this purpose, C2C12 cells were transiently cotransfected with YA-R1, -R2, -R3, and -R2÷R3 mutants or wild-type NF-YA together with the cyclin B2 promoter (Figure 10B). We found that the activity of this promoter was up-regulated in the presence of mutants compared with that observed when cotransfected with wild-type NF-YA. This up-regulation was lost in the context of a cyclin B2 promoter carrying three mutated CCAAT boxes (data not shown).

To begin to address whether the increased activity of mutant proteins is due to a lack of ubiquitylation or acetylation, we tested the ability of p300 or ubiquitin to modulate the transcriptional activity of wild-type NF-YA. C2C12 cells were transiently cotransfected with wild-type NF-YA and p300 or wild-type NF-YA and UbHA together with the cyclin B2 promoter (Figure 10C). Interestingly, p300 enhances NF-YA activity, whereas ubiquitin reduces it. Taken together, the results indicate that a more stable NF-YA protein still retains and enhances its transcriptional activity. Moreover they suggest that NF-YA transcriptional activity could be due to a balance between acetylation and ubiquitylation.

Figure 10.

Acetylation and ubiquitylation of NF-YA lysine residues are involved on its transcriptional activity. (A) Fluorescence of NF-YA GFP and mutant NF-YA (YA-R1, -R2, and -R3) GFP proteins in C2C12 cells. (B) Luciferase activity of C2C12 cells cotransfected with pCCAAT-B2LUC and wild-type NF-YA or its mutants. (C) Luciferase activity of C2C12 cells cotransfected with pCCAAT-B2LUC and wild-type NF-YA and p300 or ubiquitin (UbHA). In both B and C luciferase activity was normalized for β-gal and for protein amount. The data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations from three separate experiments.

Forced Expression of a Stable NF-YA Protein Sustains Expression of Its Target Genes and Influences Cell Proliferation

To further support the hypothesis that a stable NF-YA protein could influence the expression of NF-Y target genes, we followed the expression of cyclin B1, cyclin A, and cdk1 (Farina et al., 1999; Manni et al., 2001; Gurtner et al., 2003, 2008; Imbriano et al., 2005; Di Agostino et al., 2006) after overexpression of wild-type NF-YA or mutant YA-R3 protein. As shown in Figure 11, in cells transfected with wild-type NF-YA, expression of these genes declined paralleling NF-YA decrease. In contrast, their expression was sustained in cells transfected with stable mutant YA-R3. Interestingly, the upward mobility shift of the cdk1 protein suggests phosphorylation and activation of this protein.

Figure 11.

Forced expression of a stable NF-YA protein sustains expression of its target genes and influences cell proliferation. Western blot analysis of NF-YA, cyclin B1, cyclin A, cdk1, and HSP70 as loading control in C2C12 cells at different times posttransfection. Left, C2C12 cells transfected with empty vector. Middle and right, C2C12 cells transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type NF-YA or mutant NF-YA YA-R3 respectively.

Next, we asked whether stable NF-YA mutants are able to influence cell proliferation. To answer this question we performed colony formation assays in NIH-3T3 cells. NF-YA or its mutants were transfected with a vector bearing the puromycin resistance gene for selection. As reported in Table 1, we found that YA-R2 and -wR3 mutants induced an increase in colony formation compared with wild-type NF-YA, whereas formation of colonies was essentially not affected by the YA-R1 mutant, in good agreement with its lesser stability (Figure 5D). Taken together, these results indicate that a degradation-resistant NF-YA mutant influences cell proliferation and sustains, at transcriptional level, expression of its target cell cycle genes.

Table 1.

Degradation-resistant NF-YA mutants increase cell proliferation

| NF-YA | YA-R1 | YA-R2 | YA-R3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIH3T3 | 34 ± 2 | 41 ± 3 | 63 ± 5 | 67 ± 4 |

Values are mean ± SD.

DISCUSSION

Several cell cycle regulatory proteins as well as transcriptional activators among which c-fos, NF-κB, E2F1, β-catenin, and p53 need to be modulated to trigger their activation. Their intracellular levels are regulated by the ubiquitin/proteasome degradation pathway and it is clear that changes in their steady-state levels can influence the activity of the corresponding target genes (Scheffner et al., 1990; Treier et al., 1994; Chen et al., 1996; Hofmann et al., 1996; Aberle et al., 1997; Kodadek et al., 2006). Of note, many of these proteins are also acetylated. (Hofmann et al., 1996; Zhang and Bieker, 1999). Histones acetyl transferase enzymes, such as p300, serve multiple roles and are believed to target many, if not most, genes.

The results presented in this study reveal that both the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway and the acetylation status regulate the expression and the functional activity of the transcription factor NF-Y. We demonstrate that NF-YA undergoes the two different modifications targeting partially overlapping lysine residues. Our results open a scenario in which NF-YA acetylation of specific lysines might prevent subsequent ubiquitylation of the same residues, thereby inhibiting its proteasome-mediated degradation. Because NF-Y is important for promoter activation, it came as no surprise that interactions between this factor and p300 surfaced. Indeed, dynamic recruitment of p300 together with NF-Y, has been documented on cell cycle regulated promoters (Caretti et al., 2003; Salsi et al., 2003; Di Agostino et al., 2006; Gurtner et al., 2008).

NF-Y is composed of three subunits: NF-YA, -YB, and -YC. Although amounts of the NF-YB and -YC subunits are relatively constant, NF-YA protein expression fluctuates (Chang and Liu 1994; Marziali et al., 1997; Bolognese et al., 1999; Farina et al., 1999; Gurtner et al., 2003; Gurtner et al., 2008), indicating that it is the regulatory subunit of the trimer. In agreement with this hypothesis we observed that NF-YA, but not -YB and -YC expression, is regulated by the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. Our studies on the NF-YA protein half-life strongly support the notion that the protein is regulated at posttranslational level. Indeed the half-life of NF-YA, which is ∼2 h in proliferating cells, is increased by inhibition of the proteosome pathway. This effect is specific for the NF-YA subunit, because no modulation of the NF-YB subunit half-life was observed in the same experimental conditions. Further we provide evidence that endogenous NF-YA is a substrate for ubiquitylation in vivo. This result, together with the finding that NF-YA is accumulated after proteasome inhibition, strongly indicates that the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway degrade this subunit.

The COOH terminus of NF-YA is highly conserved across species (Mantovani 1998). Indeed, in this region reside the domains essential for the function of the trimer: the interaction domain with the NF-YB and -YC dimer and the DNA-binding domain. On the basis of this, we reasoned that the six lysines present in this region might be also essential for regulation of NF-YA protein stability. Mutant proteins carrying amino acid substitutions of potential ubiquitylation sites in the COOH terminus of NF-YA (lysines K283, K289, K292, and K296) are more stable than wild-type protein. In agreement with this, mutation of these lysines markedly prevents the ubiquitylation of NF-YA protein, thus suggesting that these lysines play a major role in NF-YA protein stability. In contrast to this, the other two lysines present in the COOH terminus, K269 and K276, appear to be less involved in the regulation of NF-YA stability.

Interestingly, we have observed that two of the NF-YA ubiquitylated lysines are also target of p300 acetylation in vitro. Moreover, modulation of p300 abundance through ectopic expression or siRNA, impacts on NF-YA expression influencing formation of ubiquitylated NF-YA forms, suggesting that p300-mediated acetylation of NF-YA could prevent at least in part its ubiquitylation, potentially by interfering with the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Thus, our data suggest that competition between ubiquitylation and acetylation of overlapping lysine residues might constitute a mechanism to regulate NF-YA protein stability. Of note, the limited but significant conservation of these lysines suggests that NF-YA protein stability might be regulated in a similar manner in different species.

It has been demonstrated that ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of several transcription factors regulates their transcriptional activity. For example after DNA damage, the largest subunit of RNA pol II is selectively targeted for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and this limits transcription until DNA damage is repaired (Krogan et al., 2004; Somesh et al., 2005). HIF-1α can be physiologically degraded through the ubiquitin-dependent proteasome pathway, and this negatively impacts on its transcriptional activity (Liu et al., 2007; Wei and Yu, 2007). On the contrary, in some cases, the activity of the proteasome is required for transcription. Transcriptional activation by the progesterone receptor is inhibited by drugs that inhibit the proteasome (Dennis et al., 2005); ubiquitylation of Gcn4, and the proteolytic function of the proteasome are necessary for transcription mediated by this factor (Lipford et al., 2005); Gal4 ubiquitylation and destruction are required for activation by Gal4. Defects in the ubiquitylation and stability of this transcriptional activator leads to inappropriate phosphorylation of RNA pol II and pre-mRNA processing (Muratani et al., 2005). Our data support the hypothesis that also the cellular function of NF-Y is regulated at the level of protein stability. We observed that a more stable NF-YA protein still retains and enhances its transcriptional activity sustaining the expression of target genes, cdk1, cyclin A, and cyclin B1. Thus, in the case of NF-YA, the ubiquitin-dependent proteasome pathway negatively impacts on NF-Y transcriptional activity. In good agreement with this, we observed that the NF-YA fraction in the nucleus, where it is suppose to act as transcription factor, is more acetylated than the cytoplasmic one, whereas the ubiquitylated form is prevalently stored in the cytoplasm. Moreover, we observed that the nuclei of premitotic cells contain largely acetylated NF-YA protein, whereas in postmitotic cells, where NF-Y does not exert its activity, NF-YA protein is only ubiquitylated.

Finally, we observed that degradation-resistant NF-YA mutants increase cell proliferation. As discussed above, these mutants also sustain expression of NF-Y target genes. Thus, one possibility is that these mutants increase cell proliferation through the up-regulation of NF-Y target genes. NF-Y could serve as a common transcription factor for an increasing number of cell cycle control genes (Elkon et al., 2003). This suggests that the more stable NF-YA protein could also sustain the expression of other genes involved in cell cycle progression, known to be targets of NF-Y. In agreement with this, the levels of NF-Y activity in the cells strongly influences cell proliferation. It has been reported that inhibition of NF-YA expression blocks cell cycle progression in G1 and G2 (Hu and Maity, 2000) and the knock out of the NF-YA subunit in mice leads to embryo lethality (Bhattacharya et al., 2003). Thus, there may be specific mechanisms for limiting free NF-Y levels, failure of which would compromise cell survival and/or homeostasis. The destruction of NF-YA by Ub-mediated proteolysis could be one of the mechanisms that the cells have evolved to keep the activity of NF-Y tightly regulated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dirk Bohmann for generously providing ubiquitin plasmids, Silvia Bacchetti for editing the manuscript, Maria Pia Gentileschi for technical advice, and Vincenzo Giusti for computing assistance. This work has been partially supported by grants from Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Ministero della Sanita' (ICS-120.4/RA00-90; R.F.02/184), and ISS-ACC to G.P. and from AIRC, CARIPLO_NOBEL, and COFIN to R.M.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0295) on September 24, 2008.

REFERENCES

- Aberle H., Bauer A., Stappert J., Kispert A., Kemler R. Betacatenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A., Deng J. M., Zhang Z., Behringer R., de Crombrugghe B., Maity S. N. The B subunit of the CCAAT box binding transcription factor complex CBF/NF-Y) is essential for early mouse development and cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8167–8172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolognese F., Wasner F., Dohna C. L., Gurtner A., Ronchi A., Muller H., Manni I., Mossner J., Piaggio G., Mantovani R., Engeland K. The cyclin B2 promoter depends on NF-Y, a trimer whose CCAAT-binding activity is cell cycle regulated. Oncogene. 1999;18:1845–1853. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasier A. R., Tate J. E., Habener J. F. Optimized use of the firefly luciferase assay as a reporter gene in mammalian cell lines. Biotechniques. 1989;7:1116–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caretti G., Motta M. C., Mantovani R. NF-Y associates with H3–H4 tetramers and octamers by multiple mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:8591–8603. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caretti G., Salsi V., Vecchi C., Imbriano C., Mantovani R. Dynamic recruitment of NF-Y and histone acetyltransferases on cell-cycle promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30435–30440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H. M., La Thangue N. B. p300/CBP proteins: HATs for transcriptional bridges and scaffolds. J. Cell Sci. 2001;4:2363–2373. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.13.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z. F., Liu C. J. Human thymidine kinase CCAAT-binding protein is NF-Y, whose A subunit expression is serum-dependent in human IMR-90 diploid fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;26:17893–17898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. J., Parent L., Maniatis T. Site-specific phosphorylation of IkappaBalpha by a novel ubiquitination-dependent protein kinase activity. Cell. 1996;84:853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A., Orian A., Schwartz A. L. Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis: biological regulation via destruction. BioEssays. 2000;22:442–451. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200005)22:5<442::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins G. A., Tansey W. P. The proteasome: a utility tool for transcription. Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 2006;16:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie R. A. Biochemical characterization of the NF-Y transcription factor complex during B lymphocyte development. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:1430–1434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis A. P., Lonard D. M., Nawaz Z., O'Malley B. W. Inhibition of the 26S proteasome blocks progesterone receptor-dependent transcription through failed recruitment of RNA polymerase II. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;94:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Agostino S., Strano S., Emiliozzi V., Zerbini V., Mottolese M., Sacchi A., Blandino G., Piaggio G. Gain of function of mutant p53, the mutant p53/NF-Y protein complex reveals an aberrant transcriptional mechanism of cell cycle regulation. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkon R., Linhart C., Sharan R., Shamir R., Shiloh Y. Genome-wide in silico identification of transcriptional regulators controlling the cell cycle in human cells. Genome Res. 2003;13:773–780. doi: 10.1101/gr.947203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina A., Manni I., Fontemaggi G., Tiainen M., Cenciarelli C., Bellorini M., Mantovani R., Sacchi A., Piaggio G. Down-regulation of cyclin B1 gene transcription in terminally differentiated skeletal muscle cells is associated with loss of functional CCAAT-binding NF-Y complex. Oncogene. 1999;18:2818–2827. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimuro M., Yokosawa H. Production of antipolyubiquitin monoclonal antibodies and their use for characterization and isolation of polyubiquitinated proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2005;399:75–86. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J., Zhu J., Goodman O. B., Jr., Pestell R. G., Schlegel P. N., Nanus D. M., Shen R. Activation of p300 histone acetyltransferase activity and acetylation of the androgen receptor by bombesin in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:2011–2021. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner A., Fuschi P., Magi F., Colussi C., Gaetano C., Dobbelstein M., Sacchi A., Piaggio G. NF-Y dependent epigenetic modifications discriminate between proliferating and postmitotic tissue. PlosOne. 2008;3:e2047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner A., Manni I., Fuschi P., Mantovani R., Guadagni F., Sacchi A., Piaggio G. Requirement for down-regulation of the CCAAT-binding activity of the NF-Y transcription factor during skeletal muscle differentiation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:2706–2715. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hateboer G., Kerkhoven R. M., Shvarts A., Bernards R., Beijersbergen R. L. Degradation of E2F by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: regulation by retinoblastoma family proteins and adenovirus transforming proteins. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2960–2970. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A., Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1996;30:405–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F., Martelli F., Livingston D. M., Wang Z. The retinoblastoma gene product protects E2F-1 from degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2949–2959. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Maity S. N. Stable expression of a dominant negative mutant of CCAAT binding factor/NF-Y in mouse fibroblast cells resulting in retardation of cell growth and inhibition of transcription of various cellular genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:4435–4444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbriano C., Gurtner A., Cocchiarella F., Di Agostino S., Basile V., Gostissa M., Dobbelstein M., Del Sal G., Piaggio G., Mantovani R. Direct p53 transcriptional repression: in vivo analysis of CCAAT-containing G2/M promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:3737–3751. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3737-3751.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S., Scotto K. W. Transcriptional regulation of the MDR1 gene by histone acetyltransferase and deacetylase is mediated by NF-Y. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:4377–4384. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodadek T., Sikder D., Nalley K. Keeping transcriptional activators under control. Cell. 2006;127:261–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner K., Jerome V., Schmidt T., Muller R. Cycle regulation of the murine cdc25B promoter: essential role for nuclear factor-Y and a proximal repressor element. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:9662–9669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan N. J., Lam M. H., Fillingham J., Keogh M. C., Gebbia M., Li J., Datta N., Cagney G., Buratowsky S., Emili S., Greenblatt J. F. Proteasome involvement in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:1027–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Herrler M., Landsberger N., Kaludov N., Ogryzko V. V., Nakatani Y., Wolffe A. P. Xenopus NF-Y pre-sets chromatin to potentiate p300 and acetylation-responsive transcription from the Xenopus hsp70 promoter in vivo. EMBO J. 1998;17:6300–6315. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati C., di Silvio A., Ottolenghi S., Mantovani R. NF-Y binding to twin CCAAT boxes: role of Q-rich domains and histone fold helices. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;29:1441–1455. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipford J. R., Smith G. T., Chi Y., Deshaies R. J. A putative stimulatory role for turnover in gene expression. Nature. 2005;438:113–116. doi: 10.1038/nature04098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. V., Baek J. H., Zhang H., Diez R., Cole R. N., Semenza G. L. RACK1 competes with HSP90 for binding to HIF-1α and is required for O2-independent and HSP90 inhibitor-induced degradation of HIF-1α. Mol. Cell. 2007;25:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo R. S., Massagué J. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of TGFbeta- activated Smad2. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:472–478. doi: 10.1038/70258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manni I., Mazzaro G., Gurtner A., Mantovani R., Haugwitz U., Krause K., Engeland K., Sacchi A., Soddu S., Piaggio G. NF-Y mediates the transcriptional inhibition of the cyclin B1, cyclin B2, and cdc25C promoters upon induced G2 arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:5570–5576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani R., Pessara U., Tronche F., Li X. Y., Knapp A. M., Pasquali J. L., Benoist C., Mathis D. Monoclonal antibodies to NF-Y define its function in MHC class II and albumin gene transcription. EMBO J. 1992;11:3315–3322. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani R. A survey of 178 NF-Y binding CCAAT boxes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1135–1143. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani R. The molecular biology of the CCAAT boxes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;26:1135–1143. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marziali G., Perrotti E., Ilari R., Testa U., Coccia E. M., Battistini A. Transcriptional regulation of the ferritin heavy-chain gene: the activity of the CCAAT binding factor NF-Y is modulated in heme-treated Friend leukemia cells and during monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:1387–1395. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratani M., Kung C., Shokat K. M., Tansey W. P. The F box protein Dsg1/Mdm30 is a transcriptional coactivator that stimulates Gal4 turnover and cotranscriptional mRNA processing. Cell. 2005;120:887–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford K., Crockett C., Jensen J. P., Weissman A. M., Byers S. W. Serine phosphorylation-regulated ubiquitination and degradation of beta-catenin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24735–24738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. H., et al. Transcriptional regulation of the transforming growth factor beta type II receptor gene by histone acetyltransferase and deacetylase is mediated by NF-Y in human breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:5168–5174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puca R., Nardinocchi L., D'Orazi G. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression by homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;27:22–28. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock K. L., Gramm C., Rothstein L., Clark K., Stein R., Dick L., Hwang D., Goldberg A. L. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Cell. 1994;78:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsi V., Caretti G., Wasner M., Reinhard W., Haugwitz U., Engeland K., Mantovani R. Interactions between p300 and multiple NF-Y trimers govern cyclin B2 promoter function. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:6642–6650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffner M., Werness B. A., Huibregtse J. M., Levine A. J., Howley P. M. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell. 1990;63:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbik N., Haines D. S. Ub on the move. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004;93:11–19. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somesh B. P., Reid J, Liu W.-F., Søgaard T.M.M., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Svejstrup J. Q. Multiple mechanisms confining RNA polymerase II ubiquitination to polymerases undergoing transcriptional arrest. Cell. 2005;121:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner D. E., Berger S. H. Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000;64:435–459. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.2.435-459.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrower J. S., Hoffman L., Rechsteiner M., Pickart C. M. Recognition of the polyubiquitin proteolytic signal. EMBO J. 2000;19:94–102. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treier M., Staszewski L. M., Bohmann D. Ubiquitin-dependent c-Jun degradation in vivo is mediated by the delta domain. Cell. 1994;78:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.K.W. Developing selective inhibitors of calpain. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1990;11:139–142. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90060-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Yu X. D. Hypoxia-inducible factors: crosstalk between their protein stability and protein degradation. Cancer Lett. 2007;257:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemzoumi K., Frontini M., Bellorini M., Mantovani R. NF-Y histone fold alpha1 helices help impart CCAAT specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;19:327–337. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Bieker J. Acetylation and modulation of erythroid Krüppel-like factor (EKLF) activity by interaction with histone acetyltransferases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;95:9855–9860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Kavsak P., Abdollah S., Wrana J. L., Thomsen G. H. A SMAD ubiquitin ligase targets the BMP pathway and affects embryonic pattern formation. Nature. 1999;400:687–693. doi: 10.1038/23293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker J., Gross C., Lucibello F. C., Truss M., Ehlert F., Engeland K., Muller R. Cell cycle regulation of cdc25C transcription is mediated by the periodic repression of the glutamine-rich activators NF-Y and Sp1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995a;23:3822–3830. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.19.3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker J., Lucibello F. C., Wolfraim L. A., Gross C., Truss M., Engeland K., Muller R. Cell cycle regulation of the cyclin A, cdc25C and cdc2 genes is based on a common mechanism of transcriptional repression. EMBO J. 1995b;14:4514–4522. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]