Abstract

RAM (regulation of Ace2p transcription factor and polarized morphogenesis) is a conserved signaling network that regulates polarized morphogenesis in yeast, worms, flies, and humans. To investigate the role of the RAM network in cell polarity and hyphal morphogenesis of Candida albicans, each of the C. albicans RAM genes (CaCBK1, CaMOB2, CaKIC1, CaPAG1, CaHYM1, and CaSOG2) was deleted. All C. albicans RAM mutants exhibited hypersensitivity to cell-wall- or membrane-perturbing agents, exhibiting cell-separation defects, a multinucleate phenotype and loss of cell polarity. Yeast two-hybrid and in vivo functional analyses of CaCbk1p and its activator, CaMob2p, the key factors in the RAM network, demonstrated that the direct interaction between the SMA domain of CaCbk1p and the Mob1/phocein domain of CaMob2p was necessary for hyphal growth of C. albicans. Genome-wide transcription profiling of a Camob2 mutant suggested that the RAM network played a role in serum- and antifungal azoles–induced activation of ergosterol biosynthesis genes, especially those involved in the late steps of ergosterol biosynthesis, and might be associated, at least indirectly, with the Tup1p-Nrg1p pathway. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the RAM network is critically required for hyphal growth as well as normal vegetative growth in C. albicans.

INTRODUCTION

Most cells, including single-cell organisms and cells in multicellular invertebrates and vertebrates, display polarity, defined as asymmetry in cell shape, protein distribution, and/or cell functions (Nelson, 2003). Establishment and maintenance of proper cell polarity are essential for fundamental aspects of cellular life; processes such as intracellular transport, differentiation, morphogenesis, and motility all require precise temporal and spatial coordination of many landmark and signaling proteins. In a variety of eukaroyotic cell types with different shapes and functions, core mechanisms involved in regulating cell polarity seem to be quite general (Drubin and Nelson, 1996; Nelson, 2003). These include site selection for polarized growth, localized assembly of signaling proteins, nucleation and assembly of cytoskeleton, and targeted vesicle delivery to the sites of membrane growth (Nelson, 2003; Pruyne et al., 2004).

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae regulation of Ace2p transcription factor and polarized morphogenesis (RAM) signaling network controls two genetically distinct cellular processes that regulate the maintenance of cell polarity and daughter-cell–specific nuclear localization of Ace2p. Ace2p, in turn, activates cell separation genes during mitotic exit. Consequently, mutation of RAM genes results in defective morphology and mating projection, random budding patterns, and aggregation of unseparated cells (Racki et al., 2000; Bidlingmaier et al., 2001; Colman-Lerner et al., 2001; Weiss et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2003; Schneper et al., 2004; Kurischko et al., 2005; Voth et al., 2005; Jansen et al., 2006). In Cryptococcus neoformans, RAM mutations also caused defective cytokinesis and actin mislocalization. But instead of resulting in loss of polarity, these defects led to constitutive hyperpolarization, suggesting that the RAM signaling network may play both conserved and divergent roles in other organisms (Walton et al., 2006).

The yeast RAM network consists of six proteins: Cbk1p, Mob2p, Kic1p, Hym1p, Pag1p, and Sog2p (Nelson et al., 2003). The RAM genes are essential for viability in S. cerevisiae strains possessing the wild-type SSD1 gene (SSD1-v), but not in strains carrying the defective ssd1-d allele (Winzeler et al., 1999; Bidlingmaier et al., 2001; Du and Novick, 2002; Jorgensen et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2003; Kurischko et al., 2005). Cbk1p (cell wall biosynthesis kinase 1) is an NDR (nuclear Dbf2-related) kinase member of a superfamily of serine/threonine kinases (Hergovich et al., 2006). A recent study revealed that Cbk1p phosphoregulation is essential for RAM network control of Ace2p-dependent transcription and cell polarity (Jansen et al., 2006). Mob2p is a Cbk1p-binding protein required for activation and proper localization of Cbk1p; thus, Mob2p is critical for Cbk1p kinase activity (Colman-Lerner et al., 2001; Weiss et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2003). Kic1p is the yeast Ste20-like kinase that functions genetically upstream of the Cbk1p kinase, probably activating the Cbk1p–Mob2p complex (Nelson et al., 2003). Hym1p, an orthologous protein of Aspergillus nidulans hymA and Schizosaccharomyces pombe Pmo25p, interacts with Cbk1p and Kic1p and is important for catalytic activity and proper localization of the Cbk1p–Mob2p complex (Karos and Fischer, 1996; Bidlingmaier et al., 2001; Nelson et al., 2003; Kanai et al., 2005). Pag1p (Tao3p) belongs to a group of large, conserved scaffolding proteins and may facilitate Cbk1p-Mob2p kinase activation by Kic1p (Du and Novick, 2002; Nelson et al., 2003; Hergovich et al., 2006). Sog2p, a leucine-rich-repeat–containing protein, is an essential component of the RAM signaling network in yeast, but its mammalian counterpart has not been identified (Nelson et al., 2003; Walton et al., 2006).

Candida albicans is an important opportunistic fungal pathogen in humans. It causes not only superficial infection, but also systemic or life-threatening infections in immunocompromised hosts (Odds et al., 1988; Corner and Magee, 1997). Because mutants of C. albicans that are unable to switch between yeast and hyphal forms exhibit a great reduction in virulence in a mouse system, the yeast-to-hypha transition is thought to be one of the major contributing factors to the virulence of C. albicans (Lo et al., 1997; Mitchell, 1998; Brown and Gow, 1999). The ability of C. albicans to change its morphology in response to environmental stimuli is believed to allow it to rapidly colonize and disseminate in host tissues, facilitating the spread of infection (Calderone and Fonzi, 2001; Gow et al., 2002; Kumamoto and Vinces, 2005). In vitro hypha-inducing stimuli, many of which mimic mammalian host tissue conditions, include neutral pH, elevated culture temperature (37°C), serum, N-acetylglucosamine, nutrient starvation, and embedded/microaerophilic growth conditions (Odds et al., 1988; Brown et al., 1999; Ernst, 2000). These environmental factors trigger a network of multiple signaling pathways, with different combinations of pathways triggered at varying intensities in a given environment determining the morphological change of C. albicans (Ernst, 2000). The known major signaling pathways are the following: the cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) pathway via Efg1p, a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway through Cph1p, a pH-responsive pathway through Rim101p, Tup1p-mediated repression through Rfg1p and Nrg1p, and pathways represented by the transcription factors, Cph2p, Tec1p, and Czf1p (Brown and Gow, 1999; Liu, 2001).

To find novel genes involved in the hyphal growth of C. albicans, we made use of Yarrowia lipolytica, haploid strains of which are able to form hyphae in serum-containing medium (Kim et al., 2000; Song et al., 2003). Among the clones that restored the ability of Y. lipolytica morphological mutants to form hyphae under hypha-inducing conditions was a Y. lipolytica MOB2 ortholog, a component of the RAM signaling network. In this study, we have addressed the role of the C. albicans RAM signaling network, comprised of CaCbk1p, CaMob2p, CaHym1p, CaKic1p, CaPag1p, and CaSog2p, in cell polarity and hyphal morphogenesis, a pathway that is poorly defined in this organism (McNemar and Fonzi, 2002).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and Growth Conditions

All yeast strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Tables 1 and 2. The S. cerevisiae and C. albicans strains were grown in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto-peptone, and 2% glucose) medium or synthetic complete (SC) media with appropriate auxotrophic requirements at 30°C. To determine the ability of these organisms to undergo yeast-to-hypha transition, budding C. albicans cells grown overnight in YPD medium at 28°C with vigorous shaking were incubated in hypha-inducing Spider medium, Lee's medium, or 10% serum-containing medium for the indicated times at 37°C (Lee et al., 1975; Liu et al., 1994; Song and Kim, 2006). For the purpose of expressing inducible GAL1-promoter–driven genes in S. cerevisiae, cultures were grown at 30°C in SC-Trp media containing 2% galactose and 1% raffinose.

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strains | Genotypes or descriptions | Parent | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | |||

| Wild type | |||

| SC5314 | Clinical isolate (wild-type strain) | Fonzi and Irwin (1993) | |

| CAI4 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 | SC5314 | Fonzi and Irwin (1993) |

| Knockout mutant | |||

| CMB1 | CaMOB2/Camob2::CaURA3-dpl200 | CAI4 | |

| CMB2 | CaMOB2/Camob2::dpl200 | CMB1 | |

| CMB3 | Camob2::CaURA3-dpl200/Camob2::dpl200 | CMB2 | |

| CMB4 | Camob2::dpl200/Camob2::dpl200 | CMB3 | |

| CMB5 | Camob2::dpl200/CaMOB2::CaURA3 | CMB4 | |

| CCK1 | CaCBK1/Cacbk1::CaURA3-dpl200 | CAI4 | |

| CCK2 | CaCBK1/Cacbk1::dpl200 | CCK1 | |

| CCK3 | Cacbk1::CaURA3-dpl200/Cacbk1::dpl200 | CCK2 | |

| CKC1 | CaKIC1/Cakic1::CaURA3-dpl200 | CAI4 | |

| CKC2 | CaKIC1/Cakic1::dpl200 | CKC1 | |

| CKC3 | Cakic1::CaURA-dpl200/Cakic1::dpl200 | CKC2 | |

| CPG1 | CaPAG1/Capag1::CaURA3-dpl200 | CAI4 | |

| CPG2 | CaPAG1/Capag1::dpl200 | CPG1 | |

| CPG3 | Capag1::CaURA3-dpl200/Capag1::dpl200 | CPG2 | |

| CHM1 | CaHYM1/Cahym1::CaURA3-dpl200 | CAI4 | |

| CHM2 | CaHYM1/Cahym1::dpl200 | CHM1 | |

| CHM3 | Cahym1::CaURA3-dpl200/Cahym1::dpl200 | CHM2 | |

| CSG1 | CaSOG2/Casog2::CaURA3-dpl200 | CAI4 | |

| CSG2 | CaSOG2/Casog2::dpl200 | CSG1 | |

| CSG3 | Casog2::CaURA3-dpl200/Casog2::dpl200 | CSG2 | |

| CSD1 | CaSSD1/Cassd1::CaURA3-dpl200 | CAI4 | |

| CSD2 | CaSSD1/Cassd1::dpl200 | CSD1 | |

| CSD3 | Cassd1::CaURA3-dpl200/Cassd1::dpl200 | CSD3 | |

| CSD4 | Cassd1::dpl200/Cassd1::dpl200 | CSD4 | |

| CDC1 | Cassd1::dpl200/Cassd1::dpl200/CaCBK1/Cacbk1::CaURA3-dpl200 | CSD4 | |

| CDC2 | Cassd1::dpl200/Cassd1::dpl200/CaCBK1/Cacbk1::dpl200 | CDC1 | |

| CDC3 | Cassd1::dpl200/Cassd1::dpl200/Cacbk1::CaURA3-dpl200/Cacbk1::dpl200 | CDC2 | |

| CDK1 | Cassd1::dpl200/Cassd1::dpl200/CaKIC1/Cakic1::CaURA3-dpl200 | CSD4 | |

| CDK2 | Cassd1::dpl200/Cassd1::dpl200/CaKIC1/Cakic1::dpl200 | CDK1 | |

| CDK3 | Cassd1::dpl200/Cassd1::dpl200/Cakic::CaURA3-dpl200/Cakic1::dpl200 | CDK2 | |

| CaMOB2 domain-deletion | |||

| CMB4[CaMOB2] | Camob2::dpl200/CaMOB2::CaURA3 | CMB4 | |

| CMB4[CaMOB2N] | Camob2::dpl200/CaMOB2(N)::CaUR3 | CMB4 | |

| CMB4[CaMOB2NΔC] | Camob2::dpl200/CaMOB2(NΔC)::CaURA3 | CMB4 | |

| CMB4[CaMOB2C] | Camob2::dpl200/CaMOB2(C)::CaUR3 | CMB4 | |

| S. cerevisiae | |||

| Complementation test | |||

| JK147 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr | Kim et al. (1990) | |

| JK147-M1 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr mob2::tc5-URA3-tc5 | JK147 | |

| JK147-M2 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr mob2::tc5 | JK147-M1 | |

| JK147-C1 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr cbk1::tc5-URA3-tc5 | JK147 | |

| JK147-C2 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr cbk1::tc5 | JK147-C1 | |

| JK147[pB42AD] | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr [2 μ PGAL1-B42-AD TRP1] | JK147 | |

| JK147-M2[pB42AD] | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr mob2::tc5 [2μ PGAL1-B42-AD TRP1] | JK147-M2 | |

| JK147-C2[pB42AD] | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr cbk1::tc5 [2μ PGAL1-B42-AD TRP1] | JK147-C2 | |

| JK147-M2[pB42AD-CaMOB2] | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr mob2::tc5 [2μ PGAL1-B42-AD-CaMOB2 TRP1] | JK147-M2 | |

| JK147-M2[pB42AD-CaMOB2C] | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr mob2::tc5 [2μ PGAL1-B42-AD-CaMOB2(C) TRP1] | JK147-M2 | |

| JK147-C2[pB42AD-CaCBK1] | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 112 trp1-1 ade2 cyhr cbk1::tc5 [2μ PGAL1-B42-AD-CaCBK1 TRP1] | JK147-C2 | |

| Yeast two hybrid | |||

| EGY48 | MATα his3 trp1 ura3 LexAop(x8)-LEU2 | Estojak et al. (1995) | |

| EGY48[p8opLacZ] | EGY48 with p8opLacZ | EGY48 | Estojak et al. (1995) |

| CBM16 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD and pLexA | EGY48[p8opLacZ]b | |

| CBM26 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1 and pLexA | ||

| CBM36 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-1 and pLexA | ||

| CBM46 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-2 and pLexA | ||

| CBM56 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-3 and pLexA | ||

| CBM17 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD and pLexA-CaMOB2 | ||

| CBM18 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD and pLexA-CaMOB2C | ||

| CBM113 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD and pLexA-CaMOB2N | ||

| CBM114 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD and pLexA-CaMOB2NΔC | ||

| CBM27 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1 and pLexA-CaMOB2 | ||

| CBM37 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-1 and pLexA-CaMOB2 | ||

| CBM47 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-2 and pLexA-CaMOB2 | ||

| CBM57 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-3 and pLexA-CaMOB2 | ||

| CBM213 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1 and pLexA-CaMOB2N | ||

| CBM214 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1 and pLexA-CaMOB2NΔC | ||

| CBM28 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1 and pLexA-CaMOB2C | ||

| CBM38 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-1 and pLexA-CaMOB2C | ||

| CBM48 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-2 and pLexA-CaMOB2C | ||

| CBM58 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-3 and pLexA-CaMOB2C | ||

| CBM156 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-4 and pLexA | ||

| CBM157 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-4 and pLexA-CaMOB2 | ||

| CBM158 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-4 and pLexA-CaMOB2C | ||

| CBM166 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-5 and pLexA | ||

| CBM167 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-5 and pLexA-CaMOB2 | ||

| CBM168 | EGY48[p8opLacZ] with pB42AD-CaCBK1-5 and pLexA-CaMOB2C |

a Source is this work unless otherwise cited here.

b Parent for all subsequent entires in this column is EGY48[p8opLacZ].

Table 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmids | Description | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|

| Gene disruption | ||

| pCaMOB2D | Forward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaMOB2 disruption cassette | |

| pCaCBK1Df | Forward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaCBK1 disruption cassette | |

| pCaCBK1Db | Backward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaCBK1 disruption cassette | |

| pCaKIC1Df | Forward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaKIC1 disruption cassette | |

| pCaKIC1Db | Backward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaKIC1 disruption cassette | |

| pCaPAG1Df | Forward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaPAG1 disruption cassette | |

| pCaPAG1Db | Backward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaPAG1 disruption cassette | |

| pCaHYM1Df | Forward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaHYM1 disruption cassette | |

| pCaHYM1Db | Backward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaHYM1 disruption cassette | |

| pCaSOG2Df | Forward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaSOG2 disruption cassette | |

| pCaSOG2Db | Backward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaSOG2 disruption cassette | |

| pCaSSD1Df | Forward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaSSD1 disruption cassette | |

| pCaSSD1Db | Backward directed-CaURA3 vector with CaSSD1 disruption cassette | |

| pDDB57 | pRS315 with the CaURA3-dpl200 cassette (1.7 kb) | Wilson et al. (2000) |

| pDDB57B | pRS315 with HindIII and BglII-released CaURA3-dpl200 cassette | |

| pDDB57H | pRS315 with HindIII-released CaURA3-dpl200 cassette | |

| pDDB57BB | pGEM-Teasy with BglII-released CaURA3-dpl200 cassette | |

| pScMOB2D | Forward directed-ScURA3 vector with ScMOB2 disruption cassette | |

| pScCBK1D | Forward directed-ScURA3 vector with ScCBK1 disruption cassette | |

| pTcUR3 | The plasmid with BamHI-released tc5::URA3::tc5 pop-out cassette | Kang et al. (2000) |

| Yeast two-hybrid | ||

| pB42AD | TRP1 vector with PGAL1-B42-AD | pJG4-5 (Gyuris et al., 1993) |

| pLexA | HIS3 vector with PADH1-LexA-BD | pEG202 (Gyuris et al., 1993) |

| p8opLacZ | URA3 vector with PGAL1-LexAop(x8)-LacZ | pSH18-34 (Golemis et al., 1999; Estojak et al., 1995) |

| pB42AD-CaCBK1 | pB42AD with full sequence (1-732 aa) of CaCBK1 | |

| pB42AD-CaCBK1-1 | pB42AD with partial sequence N1 (1-120 aa) of CaCBK1 | |

| pB42AD-CaCBK1-2 | pB42AD with partial sequence N2 (1-332 aa) of CaCBK1 | |

| pB42AD-CaCBK1-3 | pB42AD with partial sequence N3 (329-732 aa) of CaCBK1 | |

| pB42AD-CaCBK1-4 | pB42AD with partial sequence N4 (121-332 aa) of CaCBK1 | |

| pB42AD-CaCBK1-5 | pB42AD with partial sequence N5 (121-265 aa) of CaCBK1 | |

| pB42AD-CaMOB2 | pB42AD with full sequence (1-313 aa) of CaMOB2 | |

| pB42AD-CaMOB2C | pB42AD with partial sequence (113-313 aa) of CaMOB2 | |

| pLexA-CaMOB2 | pLexA with full sequence (1-313 aa) of CaMOB2 | |

| pLexA-CaMOB2N | pLexA with partial sequence (1-126 aa) of CaMOB2 | |

| pLexA-CaMOB2NΔC | pLexA with partial sequence (1-214 aa) of CaMOB2 | |

| pLexA-CaMOB2C | pLexA with partial sequence (113-313 aa) of CaMOB2 | |

| Domain analysis | ||

| pB-Int.CaMOB2 | pBS KS(+/−) for integration of CaMOB2-CaURA3 into the CaMOB2 promoter locus | |

| pB-Int.CaMOB2N | pBS KS(+/−) for integration of CaMOB2(N)-CaURA3 into the CaMOB2 promoter locus | |

| pB-Int.CaMOB2NΔC | pBS KS(+/−) for integration of CaMOB2(NΔC)-CaURA3 into the CaMOB2 promoter locus | |

| pB-Int.CaMOB2C | pBS KS(+/−) for integration of CaMOB2(C)-CaURA3 into the CaMOB2 promoter locus |

a Source is this work unless otherwise cited here.

Gene Disruption

C. albicans RAM Genes.

To construct a CaMOB2 disruption cassette, 5′ and 3′ regions (333 and 300 base pairs [bp], respectively) of the CaMOB2 gene were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA using two primer sets: CaMOB2-F1 and -R1 and CaMOB2-F2 and -R2 (Table 3). The amplified fragments, digested with NotI and HindIII (5′ region fragment) and HindIII and XhoI (3′ region fragment), were cloned into pBluescript-II KS(+) vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) digested with NotI and XhoI, resulting in the plasmid, pCaMOB2+. The HindIII-digested CaURA3-dpl200 (1.6 kb) of pDDB57H (Wilson et al., 2000) was inserted into the HindIII site between the amplified CaMOB2 fragments in pCaMOB2+, resulting in the plasmid, pCaMOB2D. The NotI and XhoI fragment containing the CaMOB2 disruption cassette (2.2 kb) was liberated from pCaMOB2D and used to transform the CAI4 strain (ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434; Birse et al., 1993; Calderone and Fonzi, 2001) to uridine prototrophy using the lithium acetate method (Gietz et al., 1992). One representative transformant (CMB1; ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 Camob2:: CaURA3-dpl200/CaMOB2), grown on SC medium without uridine (SC-URA), was plated onto 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) medium to select for intrachromosomal recombination between the original CaURA3 gene and the duplicated 3′ region of CaURA3 (dpl200), causing the loss of the CaURA3-selectable marker. The resulting strain, CMB2 (ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 Camob2::dpl200/CaMOB2), was transformed with the CaMOB2 disruption cassette to delete the second allele. A homozygous CaMOB2-null mutant strain (ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 Camob2::dpl200/Camob2::CaURA3-dpl200) was thereby obtained and designated CMB3.

Table 3.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primers | Sequences (5′ to 3′)a | Restriction site |

|---|---|---|

| Gene disruption | ||

| CaMOB2 disruption | ||

| CaMOB2-F1 | ATTTGCGGCCGCCAGGAATTGACAGAACAGGTG | NotI |

| CaMOB2-R1 | CCCAAGCTTATTGAAGCAGCAGTTGCAGA | HindIII |

| CaMOB2-F2 | CCCAAGCTTTGGGTCACCAACAAGTTGAA | HindIII |

| CaMOB2-R2 | CCCTCGAGTGCTTGGGTGATTTTTCCTT | XhoI |

| CaCBK1 disruption | ||

| CaCBK1-F1 | GAATGGCATTTTGGTAGAC | |

| CaCBK1-B1 | CCATGGATCCGTAGATCTCTTGGTGGCTATTACTTTTC | BglII |

| CaCBK1-F2 | AGATCTACGGATCCATGGGAGTGTTGGGACGAACAAC | BglII |

| CaCBK1-B2 | TTTCTGTCCATCCTTGCTC | |

| CaKIC1 disruption | ||

| CaKIC1-F1 | TTATCTTACGGCCGCCTC | |

| CaKIC1-B1 | CCATGGATCCGTAGATCTACCAAATTTCCCTCTTCC | BglII |

| CaKIC1-F2 | AGATCTACGGATCCATGGTGCTCCAACTACTGCTGCTG | BglII |

| CaKIC1-B2 | CATTACAACGTTCCCCCATA | |

| CaPAG1 disruption | ||

| CaPAG1-F1 | CAATGTCGCACTTTCAATAC | |

| CaPAG1-B1 | CCATGGATCCGTAGATCTGGCTCTGGGGTTAGTGTA | BglII |

| CaPAG1-F2 | AGATCTACGGATCCATGGTTGAGGGTTTGCAACAGG | BglII |

| CaPAG1-B2 | CCATTCGGCATAATCTGTG | |

| CaHYM1 disruption | ||

| CaHYM1-F1 | TGTTGCGTTACGTTCATTGG | |

| CaHYM1-B1 | CCATGGATCCGTAGATCTACTTGGTCATTTAATGCTCG | BglII |

| CaHYM1-F2 | AGATCTACGGATCCATGGGATATTGCAAGTTTCCATGA | BglII |

| CaHYM1-B2 | TTTTGGTGCTGGTACTGCTG | |

| CaSOG2 disruption | ||

| CaSOG2-F1 | GACGGAGTGAGACCAGAA | |

| CaSOG2-B1 | CCATGGATCCGTAGATCTCGGTTTGGTGGTAGATGG | BamHI |

| CaSOG2-F2 | AGATCTACGGATCCATGGCAATGGACCAACCCCAATAC | BamHI |

| CaSOG2-B2 | AACCCCAAGAATCCATCCTC | |

| CaSSD1 disruption | ||

| CaSSD1-F1 | GGTGAGGCAATCATTTTCG | |

| CaSSD1-B1 | CCATGGATCCGTAGATCTCTTGAGCTGAAGGGTATGT | BglII |

| CaSSD1-F2 | AGATCTACGGATCCATGGTTGGTATGGCTTTGCCATG | BglII |

| CaSSD1-B2 | ACGCAATTACTCACTCACC | |

| ScCBK1 disruption | ||

| ScCBK1-F1 | GATGCGTTAGTACGGTTC | |

| ScCBK1-B1 | CCATGGATCCGTAGATCTGGTCTTGTTGTTGGGACA | BamHI |

| ScCBK1-F2 | AGATCTACGGATCCATGGAGGGACGCGTTAAGGACA | BamHI |

| ScCBK1-B2 | CGTGATGAAAGCACGATC | |

| ScMOB2 disruption | ||

| ScMOB2-F1 | CCAGTGCCAAATTTTCTG | |

| ScMOB2-B1 | CCATGGATCCGTAGATCTCGGAATTGGGGTAGTTGC | BamHI |

| ScMOB2-F2 | AGATCTACGGATCCATGGCGCTGCTACCGTTAATTG | BamHI |

| ScMOB2-B2 | GAAATGTTGGTGAAAAGATGG | |

| Linker sequence | AGATCTACGGATCCATGG | BglII, BamHI, NcoI |

| CaMOB2 domain deletion | ||

| CaURA3-F(SacI) | GGCGAGCTCGATTTGGATGGTATAAACGG | SacI |

| CaURA3-B(XbaI) | TGCTCTAGAAGGACCACCTTTGATTGTAA | XbaI |

| CaMOB2Int-promoter-F(KpnI) | CGGGGTACCTTATTCCTCTGCCTCTTC | KpnI |

| CaMOB2IntPromoter-B(BamHI) | CGCGGATCCTAGCTAATTAATATAGTTGGTTAATG | BamHI |

| CaMOB2Int-termintor-F(BamHI) | CGCGGATCCTAAACAAGCTATATGTTGCC | BamHI |

| CaMOB2Int-terminator-R(XbaI) | TGCTCTAGACAGGAACTTGGACTTCAG | XbaI |

| CaMOB2Int-Nterm-R(BamHI) | CGCGGATCCCTATTTCACATAAGGTTCACATAA | BamHI |

| CaMOB2Int-N&partialMob1-R(BamHI) | CGCGGATCCCTAGGTGACCCAGGTAATAAC | BamHI |

| CaMOB2CInt-F(BamHI) | CGCGGATCCATGAATGCTGATCCGCCTTTG | BamHI |

| Yeast two hybrid | ||

| CaCBK1th-F(EcoRI) | CCGGAATTCATGAATTTCGATCAGCTTAC | EcoRI |

| CaCBK1th-R(XhoI) | CCGCTCGAGCTATAACGCATTCTTTCTTG | XhoI |

| CaCBK1th1-B | CCGCTCGAGCTAAGGGTCAACATTAAGATG | XhoI |

| CaCBK1th2-B | CCGCTCGAGCTATAATGCCAATTTTGTTCG | XhoI |

| CaCBK1th3-F | CCGGAATTCATGAAATTGGCATTAGAAGATTTC | EcoRI |

| CaCBK1th3-1F(EcoRI) | CGGAATTCATGTCAATTAAATTGACATTAGAA | EcoRI |

| CaCBK1th3-3B(XhoI) | CGCTCGAGCTAAGCTGCTTTATCTTGAGTAGT | XhoI |

| CaMOB2th-F(EcoRI) | CCGGAATTCATGTCTTTTTTAAATACTATACGT | EcoRI |

| CaMOB2th-R(XhoI) | CCGCTCGAGCTATTTGCTTGCTTGGGT | XhoI |

| CaMOB2th-Nterm-R(XhoI) | CCGCTCGAGCTATTTCACATAAGGTTCACATAA | XhoI |

| CaMOB2th-N&partialMob1-R(XhoI) | CCGCTCGAGCTAGGTGACCCAGGTAATAAC | XhoI |

| CaMOB2Cth-F(EcoRI) | CCGGAATTCATGAATGCTGATCCGCCTTTG | EcoRI |

| RT-PCR | ||

| Gene disruption | ||

| CaKIC1-F | ATGCAAATGAATGCAACATCA | |

| CaKIC1-B | ATGATTTTTATAAATTTTAAC | |

| CaPAG1-F | ATGATAGAAATACCTGATTTAGAT | |

| CaPAG1-B | GGTTGGACTGCTGGTTGA | |

| CaHYM1-F | ATGGCATTTTTATTCAAGAGA | |

| CaHYM1-B | TTAGTGTATTCTATCTGGTAG | |

| CaSOG2-F | ATGAGTAGATCTCAAATAGTTG | |

| CaSOG2-B | GGATCCGTCACTGTTTTCGTC | |

| Microarray validation | ||

| CaACT1-F | GACGGTGAAGAAGTTGCTGC | |

| CaACT1-B | CAAACCTAAATCAGCTGGTC | |

| CaHWP1-F | GCTCAACTTATTGCTATCGC | |

| CaHWP1-B | CAGGCTGATCAGGTTGAG | |

| CaECE1-F | TTCTCCAAAATTGCCTGTGC | |

| CaECE1-B | CAACGTCATCATTAGCTCCA | |

| CaCHT2-F | ATTAGCTGCTGCAGTTGTAG | |

| CaCHT2-B | GATGGGGCAACACAAGCA | |

| CaCHT3-F | TGTTGCTGTTTATTGGGGA | |

| CaCHT3-B | TACCGCCAAAATACTTGC | |

| CaSCW11-F | ATTGTGTACTCACCATATGC | |

| CaSCW11-B | GTTCAATACCGTATGGACCTG | |

| CaERG2-F | CCAGATGGTAATGCCACG | |

| CaERG2-B | GTAACATTGCTGGAATCC | |

| CaERG3-F | CCTAAAGATGGTGCTGTTC | |

| CaERG3-B | GGACAGTGTGACAAGCGG | |

| CaERG4-F | TTGGGGATGATGATTGGA | |

| CaERG4-B | AACTGAATGGAACCCCAG | |

| CaERG5-F | GCTTCATCTCGTGATTTGG | |

| CaERG5-B | GTCGTGCAAAGCAGGATA | |

| CaERG6-F | CTGCTTCTGTTGCTGCTG | |

| CaERG6-B | GAACCTTTTGGAGCTAAACC | |

| CaERG9-F | TTACGTGATGCGGTGATG | |

| CaERG9-B | CCACTGCCATTACTTGAG | |

| CaERG13-F | TGGTCGTTTGGAAGTTGG | |

| CaERG13-B | ATGAGGCCAATGATACCC | |

| CaERG24-F | GATAAAACATGCTGGCTG | |

| CaERG24-B | CAAGGAACCCACGCTAAG | |

| CaERG25-F | GTAGATGTTTACCATGGG | |

| CaERG25-B | TGGACCAGCTTCGGTATC | |

| CaERG251-F | TCATCCAACAAGTTTTTCATCA | |

| CaERG251-B | GGAATAACCAATCCCAAAGG | |

| CaERG11-F | ATTGGAGACGTGATGCTG | |

| CaERG11-B | CTGGTTCAGTAGGTAAAACC |

a Restriction enzyme sites are single underlined; linker sequences are bold; start codons are double underlined; and stop codons are italic.

To construct the CaCBK1 disruption vectors, the 5′ and 3′ regions (489 and 383 bp, respectively) flanking the CaCBK1 gene were first amplified by PCR using the two primer sets: CaCBK1-F1 and -B1 and CaCBK1-F2 and -B2 (Table 3). The two products were PCR-fused using the linker sequence of the CaCBK1-B1 and CaCBK1-F2 primers. The fused PCR product was amplified using CaCBK1-F1 and CaCBK1-B2 and cloned into pGEM-Teasy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), resulting in the plasmid, pCaCBK1+. BglII-digested CaURA3-dpl200 was inserted into the BglII site of pCaCBK1+. The resulting plasmids were designated pCaCBK1Df and pCaCBK1Db, depending on the orientation (forward or backward) of CaURA3-dpl200. The NotI-released CaCBK1 disruption cassettes (2.5 kb) of pCaCBK1Df and pCaCBK1Db were used for the sequential disruption of the two CaCBK1 alleles. The CaKIC1, CaPAG1, and CaHYM1 disruption vectors were constructed in the same manner as the CaCBK1 disruption vectors. The CaSOG2 disruption vector was constructed by inserting the BglII-digested CaURA3-dpl200 into the BamHI site (within the linker sequence) between the amplified CaSOG2 gene fragments of pCaSOG2+. The two alleles of the CaKIC1, CaPAG1, CaHYM1, or CaSOG2 gene were each sequentially disrupted by applying the same method used for CaCBK1. Each RAM gene deletion-mutant strain was verified by PCR, Southern blot analysis, and RT-PCR.

C. albicans SSD1 CBK1 and SSD1 KIC1.

Double Deletion. The CaSSD1 disruption vectors were constructed in the same way as the CaCBK1 disruption vectors. After disrupting the two alleles of CaSSD1, we generated Cassd1Δ Cacbk1Δ and Cassd1Δ Cakic1Δ double-deletion mutants by sequentially deleting the two alleles of CaCBK1 or CaKIC1 from the Cassd1Δ mutant.

S. cerevisiae CBK1 and MOB2.

To disrupt ScCBK1 and ScMOB2, the 5′ and 3′ regions flanking each ScCBK1 or ScMOB2 gene were amplified using the following four primer pairs: ScCBK-F1 and -B1, ScCBK-F2 and -B2, ScMOB2-F1 and -B1, and ScMOB2-F2 and –B2 (Table 3). The amplified PCR fragments were PCR-fused and subcloned into pGEM-Teasy vector (Promega). The BamHI-released ScURA3 blaster from pTcUR3 (Kang et al., 2000) was inserted into the single BamHI site in the linker sequence between the fused fragments to yield pScCBK1D and pScMOB2D. The NotI-cleaved disruption cassettes from pScCBK1D and pScMOB2D were introduced into JK147, a strain derived from S. cerevisiae S288C background (Kim et al., 1990), to generate JK147-C1 (Sccbk1::URA3) and JK147-M1 (Scmob2::URA3). JK147-C2 (Sccbk1::ura3) and JK147-M2 (Scmob2::ura3) strains were obtained by selecting colonies capable of growth on 5-FOA medium.

Two-Hybrid Analysis

To construct plasmids for two-hybrid analysis, the complete coding regions and various domains of the CaCBK1 and CaMOB2 genes were amplified from C. albicans genomic DNA using the appropriate primer set (Table 3). The amplified DNA fragments were cloned between EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites and thereby fused with the LexA DNA-binding domain (BD) in pB42AD and the B42 activating domain (AD) in pLexA (Gyuris et al., 1993). The constructed plasmids were used to cotransform the p8op-lacZ-containing S. cerevisiae EGY48 strain. The resultant transformants were tested for β-galactosidase activity on selective media (SD/Gal/Raf/-HIS/-TRP/-URA/BU salt/X-gal).

Construction of C. albicans Strains Expressing Truncated Versions of CaMob2p

Four plasmids containing full-length and truncated versions of the CaMOB2 gene were generated: pB-Int-CaMOB2, expressing full-length CaMob2p(1-313); pB-Int-CaMOB2N(1-126), expressing the N-terminal region; pB-Int-CaMOB2NΔC(1-214), expressing the N-terminal region plus part of the C-terminal region; and pB-Int-CaMOB2C(113-313), expressing the C-terminal region.

To construct the pB-Int-CaMOB2 plasmid, the CaMOB2 gene (2353 bp), consisting of 669 base pairs of the promoter region (including the unique SpeI site), 942 base pairs of the complete open reading frame (ORF) sequence and 742 base pairs of the terminator region, was PCR-amplified using the CaMOB2Int-promoter-F(KpnI) and CaMOB2Int-terminator-R(XbaI) primers (Table 3) and then inserted between the KpnI and XbaI sites in pBluescript KS+ (Stratagene), generating pB-CaMOB2. The CaURA3 gene was amplified by PCR using the CaURA3-F(SacI) and CaURA3-B(XbaI) primers (Table 3). The CaURA3 gene fragment was digested with XbaI and SacI and cloned into XbaI- and SacI-digested pB-CaMOB2, generating pB-Int-CaMOB2.

To construct the pB-Int-CaMOB2N plasmid, a three-piece ligation was performed using 1) KpnI- and XbaI-digested pBluescript KS+; 2) the DNA fragment corresponding to the promoter region (669 bp) plus the N-terminal part (378 bp), which was amplified by PCR using the CaMOB2Int-promoter-F(KpnI) and CaMOB2Int-Nterm-R(BamHI) primers and digested with KpnI and BamHI; and 3) the terminator region (742 bp), which was amplified by PCR using the CaMOB2Int-termintor-F(BamHI) and CaMOB2Int-terminator-R(XbaI) primers and digested with BamHI and XbaI. The ligated product, pB-CaMOB2N, was cut with XbaI and SacI and religated to the XbaI- and SacI-digested CaURA3 gene, generating pB-Int-CaMOB2N. The pB-Int-CaMOB2NΔC and pB-Int-CaMOB2C plasmids were constructed using the same strategy used for the generation of pB-Int-CaMOB2N.

To integrate the plasmids expressing full-length and truncated versions of CaMob2p at the genomic locus of the CaMOB2 promoter region, the CMB4 (Camob2 homozygous mutant, Ura−) strain was transformed with each plasmid that had been linearized by digesting at the unique SpeI site within the CaMOB2 promoter. The correct reintegration of each plasmid was confirmed by Southern blotting.

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

To isolate total RNA for DNA microarray, C. albicans SC5314 and CMB3 (Camob2 homozygous null mutant, Ura+) strains were grown overnight in 3 ml YPD medium at 30°C with constant agitation (230 rpm). Cultures were inoculated at OD600 = 0.05 in 200 ml YPD medium and grown at 30°C with agitation to OD600 = 0.5. The cultures were harvested at room temperature and washed with fresh YPD medium. Equal aliquots of the cultures were used to inoculate flasks containing 200 ml YPD with or without 10% serum and grown at 30 or 37°C, respectively, for 60 min with constant agitation.

Total RNA (at least 200 μg) was isolated from each strain with an RNeasy Midi Kit (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration of purified RNA was adjusted to 4 μg/μl and the integrity of the RNA was analyzed by electrophoresis on 0.8% ethidium bromide-stained agarose-MOPS gels using 1 μl of the sample. cDNA synthesis was performed using 5 μg RNA, 100 ng oligo-dT12–18 (Stratagene), 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 800 μM dNTPs, 40 U of RNase inhibitor (Promega), and 200 U of SuperScript II Reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in a total volume of 20 μl. Reactions were carried out at 42°C for 50 min, followed by heat inactivation at 70°C for 15 min. The synthesized cDNA was diluted 10-fold and stored at −70°C until ready for use.

C. albicans Microarray Analysis

Microarray analyses were performed using C. albicans cDNA microarrays representing 6039 ORFs (Eurogentec, Serain, Belgium) as described by the manufacturer's microarray protocols. The chips were scanned with an Axon 4000B scanner and the acquired images were analyzed with Genepix Pro5.0 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Local background values were calculated from the area surrounding each spot and subtracted from the total spot signal values. These adjusted values were used to determine differential gene expression (Cy3/Cy5 ratio) for each spot. A normalization factor was applied to account for systematic differences in the probe labels using the differential gene expression ratio to balance the Cy5 signals.

Southern Blotting, Northern Blotting, and Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Genomic DNA of C. albicans strains was isolated using the glass bead lysis method described by Hoffman and Winston (1987). Southern blots were performed according to the method of Sambrook et al. (1989). Probe labeling and detection were carried out using a DIG Labeling Kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), according to the manufacturer's instructions. For Northern blot analysis, 10 μg of total RNA, extracted from C. albicans cells using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN), was separated on a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel, capillary-blotted onto a nylon membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) and hybridized using standard procedures (Sambrook et al., 1989). The hybridization probes were radiolabeled using the Rediprime II DNA Labeling System (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ). For semiquantitative RT-PCR, total RNA was treated with 2.5 U of RNase-free DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX) to eliminate potentially contaminating genomic DNA following the manufacturer's protocol. To verify differential expression of genes identified by microarray analysis, RT-PCR analyses were performed on independently isolated preparations of total mRNA. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) and oligo-dT12–18 primers. PCR was performed with 1 μl of 10-fold diluted cDNA, 1 U of Taq polymerase (Takara, Tokyo, Japan), 800 μM dNTPs, 0.5 mM each primer, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, and 1.5 mM MgCl2 in a total volume of 20 μl. PCR conditions were optimized taking primer melting temperatures into account; cycle numbers required to ensure exponential amplification were determined empirically. The primers used to validate microarray data are listed in Table 3. In all RT-PCR experiments, ACT1 served as an internal loading and procedure control. The amplified PCR products were separated on 1.2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed.

Drug Susceptibility Assays

To test the sensitivity to cell wall–and membrane-perturbing agents, 10 μl of serial cell suspensions were spotted onto YPD media containing calcofluor white (22 μg/ml), Congo red (200 μg/ml), SDS (0.025%), or hygromycin B (80 μg/ml). Cells were also spotted onto YPD plus Congo red or calcofluor white media supplemented with 1 M sorbitol. To test the susceptibility to different antifungal drugs or cations, spotting assays were performed using YPD plates containing 10 μg/ml fluconazole (Pfizer, New York, NY) or 0.1 μg/ml itraconazole (Janssen Pharmaceutica, Piscataway, NJ). Plates were incubated for 2–4 d at 30°C. All strains were tested in duplicate.

Staining and Microscopic Observations

Lipid rafts were stained directly with filipin (10 μg/ml prepared in DMSO; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 10 min and then analyzed by UV-fluorescence microscopy. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma). Chitin was stained by directly adding calcofluor white (1 μl of 1 mg/ml stock; Sigma) to cell suspensions (100 μl), incubating at room temperature for 15 min and washing with PBS. Actin was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) using standard procedures (Adams and Pringle, 1991). Photographs were taken using an Olympus BX61 microscope (Melville, NY) equipped with differential interference contrast optics (DIC), appropriate filters and a camera (Olympus DP71). All images were converted to gray scale, and contrast and brightness were adjusted using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

C. albicans Orthologs of RAM Network Genes

To find novel genes involved in hyphal growth of yeast, we generated a variety of Y. lipolytica mutant strains that have lost the ability to form hyphae in serum medium (Kim et al., 2000; Song et al., 2003). We transformed the mutants with a library (Song et al., 2003) and found that one of the clones complementing the morphologically defective phenotypes of the mutants was a Y. lipolytica MOB2 ortholog. Because Mob2p, which associates with Cbk1p, is known to be required for the polarized growth of S. cerevisiae (Weiss et al., 2002), and C. albicans Cbk1p has been reported to regulate expression of several hypha-specific genes (McNemar and Fonzi, 2002), we investigated the involvement of CaMob2p and other RAM signaling network components in cell polarity and hyphal morphogenesis of C. albicans. All C. albicans RAM signaling network genes were identified by searching the Candida genome databases of CGD (http://www.candidagenome.org/) and CDB (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/CandidaDB/) for ORFs displaying amino acid sequence homology to the S. cerevisiae RAM signaling network proteins, Cbk1p, Mob2p, Kic1p, Pag1p, Hym1p, and Sog2p. The catalytic domain of C. albicans Cbk1p (CaCbk1p) has features typical of Ndr family kinases, displaying 57% identity to the corresponding domain of human Ndr2. The N-terminal SMA (S100B/hMob1 association) domain of Cbk1p, also referred to as the NTR (N-terminal regulatory) domain, is 41% identical to that of human Ndr2. CaCbk1p has three conserved phosphorylation sites, one in the NTR (Ser-320), one in the activation segment (Ser-545), and one in the C-terminal hydrophobic motif (Thr-719), that are known to be required for kinase activation (Stegert et al., 2005; Jansen et al., 2006). Mob2-homologous proteins share a conserved Mob1/phocein domain; this domain in CaMob2p has 41% identity to that of its human Mob2 ortholog. CaKic1p, a member of the GCK-III subfamily of eukaryotic Ste20 kinases, shows 49% identity to human Mst3 within the kinase domain. CaHym1p contains the Mo25 family domain, which is conserved among orthologous proteins from various organisms; in CaHym1p, this domain has 44% identity to the corresponding domain in human Mo25α. CaPag1p shows relatively low sequence homology (<20%) to its counterparts in higher eukaryotes. Lastly, CaSog2p, which has a characteristic leucine-rich-repeat domain, apparently lacks orthologous proteins in higher eukaryotes.

Role of RAM Signaling Network Genes during Yeast Growth of C. albicans

To investigate the molecular and cellular functions of the C. albicans RAM signaling network, we deleted each of the C. albicans RAM genes (CaCBK1, CaMOB2, CaKIC1, CaPAG1, CaHYM1, and CaSOG2) from the wild-type CAI4 background using the URA3-blaster method. Successful disruption of the C. albicans RAM genes was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis (data not shown). All six homozygous deletion mutants for each C. albicans RAM gene were viable, indicating that the RAM genes are not essential in C. albicans.

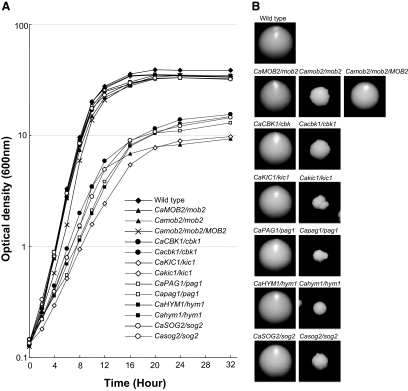

The C. albicans RAM mutants grew more slowly than wild-type and heterozygous RAM mutant strains in YPD liquid and solid media (Figure 1, A and B), indicating that the RAM signaling network genes are important for the vegetative growth of C. albicans. Microscopically, the C. albicans RAM mutants grown in YPD liquid medium were frequently observed to exhibit a cell lysis phenotype (Figure 2A), similar to that observed in S. cerevisiae RAM mutants carrying wild-type SSD1 (Kurischko et al., 2005). The cell lysis phenotype strongly implied that the C. albicans RAM mutants might have a cell-wall-integrity defect. To verify this, we tested the effects of cell wall– or membrane–perturbing agents, such as Congo red, calcofluor white, hygromycin B, and SDS, on RAM mutants. As shown in Figure 2B, these agents severely impaired the growth of all RAM mutants. The Congo red– and calcofluor white–sensitive phenotypes of the RAM mutants were partially suppressed by 1 M sorbitol, an osmotic stabilizer. These data suggest that the RAM genes are required for cell integrity in C. albicans. Because it is known that the cell lysis defect of S. cerevisiae RAM mutants is suppressed by the loss of Ssd1p function (Kurischko et al., 2005), we checked whether the defect of the C. albicans RAM mutants was also aggravated in the presence of a functional CaSsd1p. As shown in Figure 2C, in YPD medium the growth defect of the Cacbk1Δ and Cakic1Δ mutants was alleviated by the deletion of CaSSD1, which suggests that a functional CaSsd1p causes a negative effect on the growth of C. albicans RAM mutants in YPD medium. However, the Cassd1Δ mutant, which showed normal hyphal growth under hypha-inducing conditions, was very sensitive to Congo red and calcofluor white, indicating that a functional CaSsd1p is also required for cell wall integrity in C. albicans (Figure 2C). Although it is not clear why deletion of CaSSD1 in the RAM mutants recovers the growth of the mutants, it is likely that RAM signaling network contributes to cell integrity through CaSsd1p in C. albicans.

Figure 1.

Impaired growth of C. albicans RAM mutant strains. Comparison of growth (A) and colony size (B) of wild-type (SC5314) and RAM mutants. To measure growth, an equal amount of cells (OD600 = 0.05) was inoculated into YPD liquid medium and cultivated at 30°C. To compare colony size, cells from overnight cultures were spread onto YPD plates (∼50 colonies per plate), grown at 30°C for 2 d and photographed. All strains tested are uracil prototrophs. Wild type, SC5314; CaMOB2/mob2, CMB1; Camob2/mob2, CMB3; Camob2/mob2/MOB2, CMB5; CaCBK1/CBK1, CCK1; Cacbk1/cbk1, CCK3; CaKIC1/kic1, CKC1; Cakic1/kic1, CKC3; CaPAG1/pag1, CPG1; Capag1/pag1, CPG3; CaHYM1/hym1, CHM1; Cahym1/hym1, CHM3; CaSOG2/sog2, CSG1; and Casog2/sog2, CSG3.

Figure 2.

Characteristics of RAM mutants during yeast growth. (A) Morphology of RAM mutants. Cells are generally round, large, and aggregated and exhibited a lysis phenotype. (B) Sensitivity to agents perturbing cell walls or membrane structures. RAM mutants were hypersensitive to Congo red (200 μg/ml), calcofluor white (22 μg/ml), hygromycin B (80 μg/ml) and SDS (0.025%). Each strain was serially diluted (fivefold) from a stock of cells at OD600 = 0.1. Ten microliters of each dilution was spotted onto a plate and incubated at 30°C for 3 d. (C) Sensitivity of Cassd1Δ, Cassd1Δ Cacbk1Δ, and Cassd1Δ Cakic1Δ, to Congo red or calcofluor white. (D) Separation-defective phenotype of RAM mutants. Scanning electron microscopy and calcofluor-white staining indicated defects in cell wall separation. (E) Expression of cell wall genes. Expression levels of CHT2, CHT3, and SCW11 were measured in wild-type and Camob2 (CMB3; Camob2/Camob2) strains by RT-PCR using gene-specific primers listed in Table 3. Total RNA was isolated from cells grown in YPD at 30°C (Y) or in YPD supplemented with 10% serum at 37°C. ACT1 was used as an internal control.

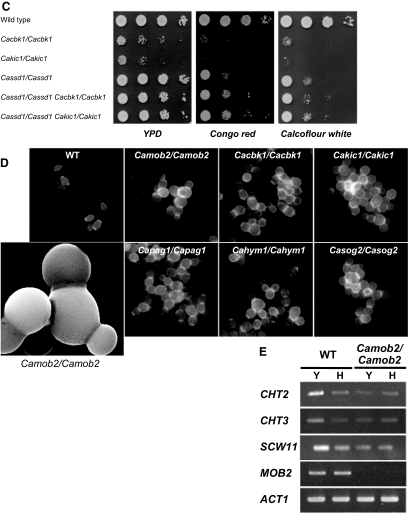

We also observed that the C. albicans RAM mutants settled to the bottom of culture tubes more rapidly than wild-type and heterozygous RAM mutant strains. The mutants also formed large cell aggregates, with mother and daughter cells remaining connected at bud necks, even after mitosis. This observation suggested a failure to degrade the septum between mother and daughter cells (Figure 2D), as has been observed in S. cerevisiae RAM mutants (Bidlingmaier et al., 2001). S. cerevisiae Ace2p, a downstream effector of the RAM signaling network, controls expression of genes such as CTS1 and SCW11, which encode proteins involved in septum degradation (Dohrmann et al., 1992; Bidlingmaier et al., 2001; Colman-Lerner et al., 2001; Doolin et al., 2001; Weiss et al., 2002). The corresponding gene in C. albicans, CaAce2p, is also known to regulate cell wall genes (Kelly et al., 2004). To determine whether the cell-separation defect of the C. albicans RAM mutants was related to the expression levels of CaAce2p target genes, we analyzed transcript levels of the cell wall genes, CHT2, CHT3, and SCW11, in a Camob2 mutant. As shown in Figure 2E, the expression of these CaAce2p target genes was significantly reduced in the Camob2 mutant compared with wild-type C. albicans during yeast growth, although the expression levels were similarly low in both wild-type and Camob2 mutant cells during hyphal growth. These results suggest that the cell-separation defect of the Camob2 mutant was related to down-regulation of the CaAce2p target genes, CHT2, CHT3, and SCW11, during yeast growth.

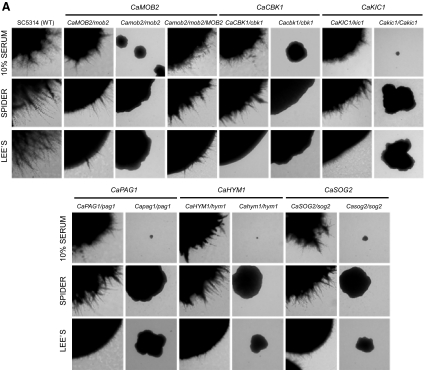

Notably, RAM mutant colonies on YPD plates were small, and colony size was also somewhat heterogeneous. Single cells of the RAM mutants were also significantly different in size in liquid medium. To determine whether this heterogeneity was associated with a defect in nuclear division or positioning, we stained RAM mutant cells with DAPI and visualized them by fluorescence microscopy. Interestingly, a significant fraction of the RAM mutant cells contained multiple nuclei (Figure 3), an observation that has not been reported for S. cerevisiae RAM mutants. Although the mechanism underlying this phenotype remains to be elucidated, this result suggests that some of the C. albicans RAM mutants may undergo more than one round of nuclear division in the absence of bud formation or cytokinesis.

Figure 3.

RAM mutants produce multinucleate yeast cells. (A) RAM mutant cells cultivated in liquid YPD medium were stained with DAPI. (B) Percentage of multinucleate cells. Strain (the number of cells counted): Cacbk1 (202), Cakic1 (324), Camob2 (759), Capag1 (521), Casog2 (259), Cahym1 (278), and SC5314 (551).

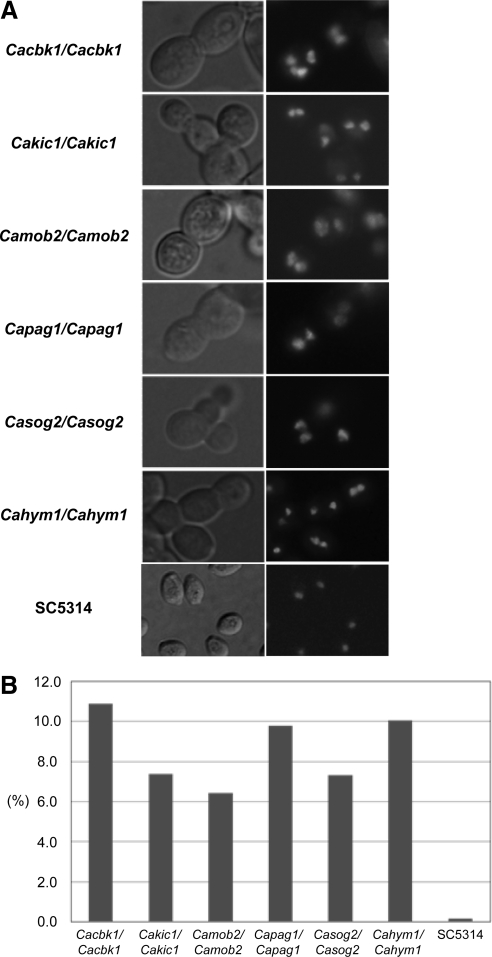

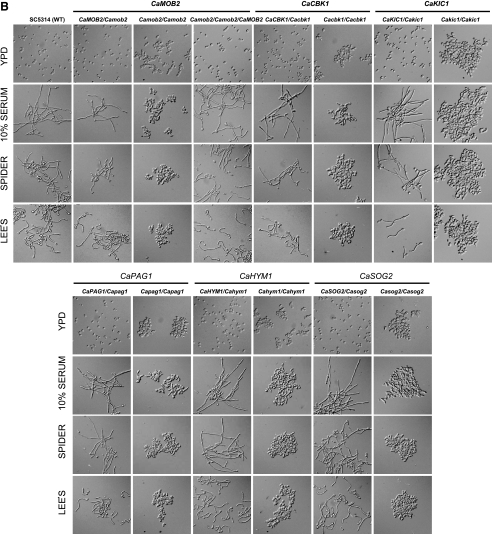

RAM Genes Are Important for Hyphal Growth of C. albicans

As shown in Figure 2A, C. albicans RAM mutant cells were large and rounded, indicating a loss of polarity. Because strong and continuous signals are required for the generation of a polarity axis toward the hyphal tip and formation of hyperpolarized hyphae in C. albicans, we investigated the role of RAM genes in hypha formation. We found that none of the RAM mutants were able to form hyphae on any of the solid hypha-inducing media tested (Figure 4A), indicating that all of the RAM genes are essential for hypha formation in C. albicans. Growth defects on solid hypha-inducing media were more pronounced for Cakic1, Capag1, Cahym1, and Casog2 homozygous mutants than for Cacbk1 and Camob2 mutants (Figure 4A). We further tested whether the C. albicans RAM mutants could form hyphae in liquid hypha-induction media, in which they grew very slowly. Most of the mutant cells remained yeast-like, although in 10% serum medium especially, some formed very short germ tube-like cells that appeared significantly swollen, thick, and curved compared with the germ tubes of wild-type cells (Figure 4B). When the abnormally short, twisted germ tubes were stained with calcofluor white, most were shown to be pseudohyphae that had distinct constrictions at septa between mother and elongated daughter cells (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the C. albicans RAM genes are required for hyphal growth under all laboratory conditions tested.

Figure 4.

RAM genes are required for hyphal development in C. albicans. (A) Colony morphology on solid media. Cells from overnight cultures were washed twice with sterile water and spread at a density of ∼50 colonies per plate on the indicated media (Lee's, Spider, and 10% serum media). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 5 d. (B) Cell morphology in liquid media. Cells from overnight cultures were washed twice with sterile water. An equal amount of cells (OD600 = 0.3) was inoculated into Lee's, Spider, or YPD plus 10% serum media and grown at 37°C for 3.5 h. For each strain, colony and cell morphology were visualized at 40× and 600× magnification, respectively, by DIC microscopy.

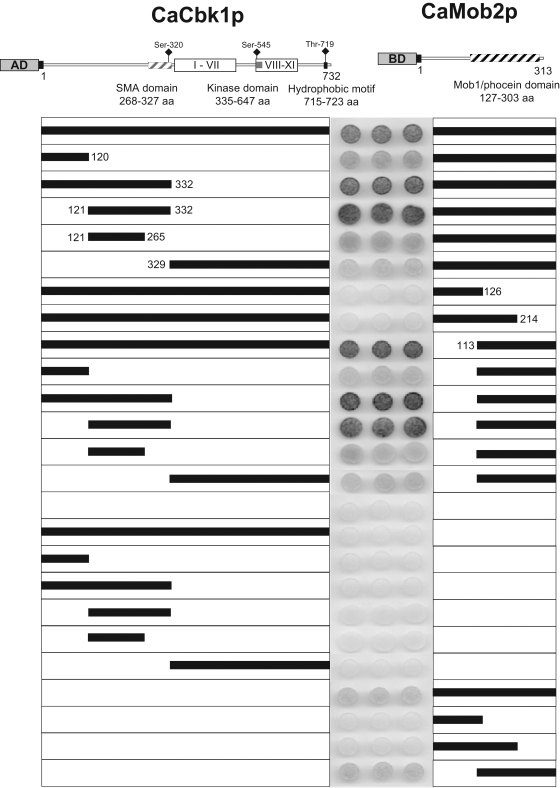

CaCbk1p and CaMob2p Physically Interact through the SMA Domain of CaCbk1p and the Mob1/phocein Domain of CaMob2p

Because Cbk1p and its activator Mob2p are known to be key factors in the RAM signaling network (Nelson et al., 2003), our subsequent investigations into the role of the RAM signaling network in C. albicans hyphal growth focused on these proteins. To obtain evidence for physical interaction between CaCbk1p and CaMob2p and to determine which domains are involved in the interaction, we performed two-hybrid assays. Fusion constructs of full-length CaCbk1p with the B42 AD and full-length CaMob2p with the LexA DNA BD were prepared. A variety of truncated versions of CaCbk1p and CaMob2p designed on the basis of structural features of the proteins were also constructed. As shown in Figure 5, CaCbk1p physically interacted with CaMob2p. The C-terminally truncated CaCbk1p, comprising the first 332 residues (CaCbk1N2[1-332]) and containing the SMA domain, was sufficient to promote a level of expression from the lacZ reporter that was similar to that stimulated by full-length CaCbk1p (CaCbk1FL[1-732]). To further map the interacting domain within the CaCbk1N2(1-332) region, three constructs encoding segments of this region—CaCbk1N1(1-120), CaCbk1N3(121-332), and CaCbk1N4(121-265)—were tested for their ability to interact with CaMob2p. These experiments demonstrated that CaCbk1N3(121-332) was sufficient to mediate binding of CaCbk1p with CaMob2p and showed that the SMA domain encompassing residues 268-327 was essential for the interaction (Figure 5). (113-313) containing the conserved Mob1/phocein family domain was responsible for the interaction of CaMob2p with CaCbk1p, especially with the SMA domain (Figure 5). Collectively, these results imply that the SMA domain of CaCbk1 interacts with the Mob1/phocein domain of CaMob2p to activate CaCbk1p.

Figure 5.

Yeast two-hybrid analysis of CaCbk1p and CaMob2p. The CaCBK1 gene and its truncated versions were fused to the LexA-activating domain; CaMOB2 and its truncated versions were fused to the B42 domain. S. cerevisiae EGY48/p8op-lacZ strains cotransformed with the constructed plasmids were tested for β-galactosidase activity on selective media containing X-gal.

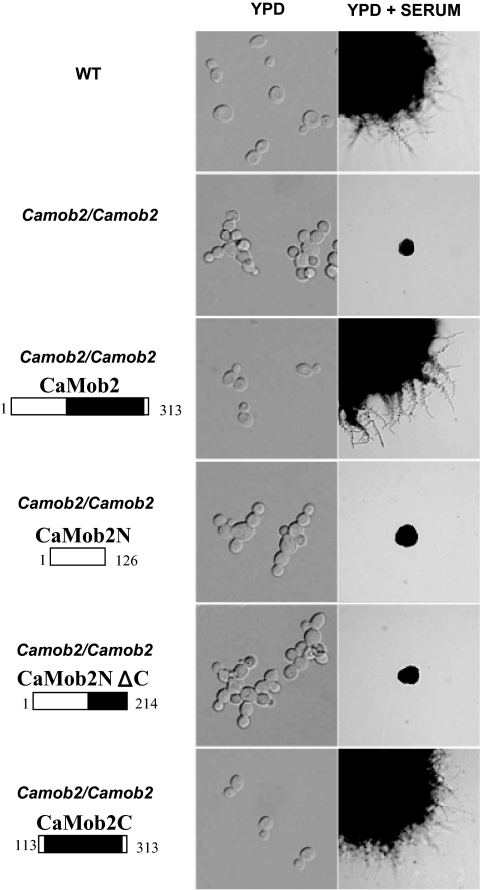

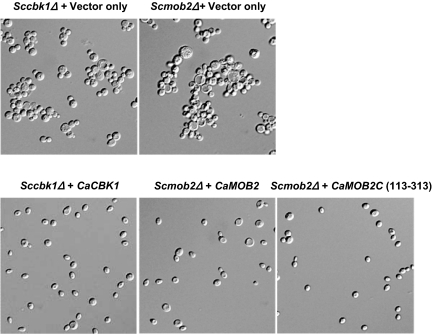

The Mob1/phocein Domain of CaMob2p Is Sufficient to Induce Hyphal Growth of C. albicans and Suppress Defective Phenotypes of an S. cerevisiae mob2 Mutant

To further characterize the role of the conserved Mob1/phocein domain of CaMob2p in CaCbk1p and CaMob2p interactions, we performed an in vivo functional analysis of CaMob2p domains. The various truncated versions of CaMOB2 were integrated into the genomic CaMOB2 locus. Strains carrying each truncated version of CaMOB2 were verified by Southern blot (data not shown) and evaluated for suppression of the morphological defects of the Camob2 homozygous mutant. Neither CaMob2N(1-126) nor CaMob2NΔC(1-214) could complement the defective phenotype of the Camob2 homozygous mutant (Figure 6). However, CaMob2C(113-313), containing the Mob1/phocein domain, conferred a normal morphological phenotype on the Camob2 mutant (Figure 6). These results are consistent with the yeast two-hybrid results. We thus conclude that the interaction between the SMA domain of CaCbk1p and the Mob1/phocein family domain of CaMob2p is essential for hyphal growth of C. albicans.

Figure 6.

In vivo functional domain analysis of the CaMob2 protein. (A) DNA fragments corresponding to the full-length (CaMob2) or truncated versions of CaMob2p (CaMob2N[1-126], CaMob2NΔC[1-214], and CaMob2C[113-313]) were cloned into an integration vector to test their function in vivo. The black box indicates the Mob1/phocein domain (amino acids 127-303). The CMB4 strain (Camob2/Camob2, uracil auxotroph) was transformed with each linearized vector, and morphological phenotypes of the transformants were observed in liquid YPD and on solid serum media.

Next, we sought to determine whether C. albicans Cbk1p could interact with S. cerevisiae Mob2p to activate downstream effectors. Using two-hybrid assays, we found that the CaCBK1 gene placed downstream of the S. cerevisiae GAL promoter complemented the cell separation and morphological defects of an Sccbk1 strain (Figure 7). CaMob2p could also rescue the defective phenotypes of an Scmob2 mutant, as could the C-terminal region of CaMob2C (113-313) containing the Mob1/phocein family domain (Figure 7). These results suggest that the CaCBK1 and CaMOB2 genes encode functional orthologs of S. cerevisiae CBK1 and MOB2, respectively, and further indicate that the interacting domains of the two proteins are highly conserved in yeast.

Figure 7.

The Mob1/phocein domain of CaMob2p suppresses defective phenotypes of the S. cerevisiae mob2 mutant. S. cerevisiae cbk1 and mob2 strains (S288c background) transformed with the plasmid carrying each orthologous gene, CaCBK1 or CaMOB2, were grown overnight in synthetic complete medium, which contained 2% galactose and 1% raffinose as a carbon source to induce the GAL1 promoter but lacked tryptophan for the maintenance of the plasmids. S. cerevisiae mob2 cells were also transformed with the plasmid expressing the Mob1/phocein domain (amino acids 127–303) only. Representative images of cells are shown.

Analysis of RAM-dependent Hypha-specific Genes

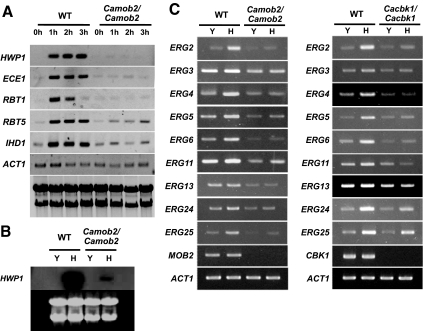

Unlike wild-type cells, RAM gene deletion mutants tended to aggregate and grow at a significantly slower rate than wild-type cells (Bidlingmaier et al., 2001; Nelson et al., 2003; Figure 1). In particular, C. albicans RAM mutants lost the capacity for serum-induced yeast-to-hypha transition, a process characterized by significant changes in gene expression. To unravel RAM network–dependent mechanism(s) governing the yeast-to-hypha transition, we performed genome-wide transcriptional profiling analysis. Four sets of microarray experiments were carried out: WT-yeast versus Camob2-yeast, WT-hypha versus Camob2-hypha, WT-yeast versus WT-hypha, and Camob2-yeast versus Camob2-hypha. Transcripts were prepared from wild-type and Camob2 mutant cells grown for 1 h in yeast growth medium (WT-yeast and Camob2-yeast) or hypha-inducing serum medium (WT-hypha and Camob2-hypha). To identify genes that were affected by CaMob2p during hyphal growth (RAM-dependent hypha-specific genes), we selected genes satisfying two requirements: differential expression between wild-type and Camob2 mutant, and differential regulation during yeast and hyphal growth. We first identified genes whose expression levels were increased in wild-type C. albicans relative to the Camob2 mutant (more than twofold) under hypha-inducing condition (WT-hypha vs. Camob2-hypha). From this group, we chose genes expressed at a similar level in both wild-type and Camob2 mutant under yeast growth condition (WT-yeast vs. Camob2-yeast). We then determined whether these candidate genes were expressed at higher levels (more than twofold) during hyphal growth than yeast growth in wild-type C. albicans (WT-yeast vs. WT-hypha) but at similar levels during both yeast and hyphal growth in the Camob2 mutant (Camob2-yeast vs. Camob2-hypha). Interestingly, the RAM-dependent hypha-specific genes identified included ECE1, RBT1, RBT5, ALS10, IHD1, KIP4, YDC1, FTR1, and orf19.6705 (Table 4), which were reported to be repressed by Tup1p and Nrg1p (Murad et al., 2001; Garcia-Sanchez et al., 2005; Kadosh and Johnson, 2005). The levels of ECE1, RBT1, RBT5, and IHD1 expression were confirmed by RT-PCR (Figure 8A). Although not detected in our microarray analysis, HWP1, which is also expressed in a hypha-specific manner and is regulated by Tup1p and Nrg1p (Braun et al., 2001; Kadosh and Johnson, 2005), was shown by RT-PCR analysis to be significantly reduced in the Camob2 mutant (Figure 8, A and B). These results suggest that the RAM signaling network may be associated with Tup1p/Nrg1p-regulated morphological processes in C. albicans.

Table 4.

C. albicans genes positively modulated in a RAM-dependent and hypha-specific manner

| Systematic name | Name | Fold |

Descriptiona | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT-H/mob2-H | WT-Y/mob2-Y | WT-H/WT-Y | mob2-H/mob2-Y | |||

| orf19.3374 | ECE1 | 118.5 | 0.9 | 183.0 | 2.5 | Hyphal-specific expression increases with extent of elongation of the cell |

| orf19.1816 | ALS3 | 59.4 | 1.0 | 46.0 | 1.3 | Adhesin; ALS family; role in epithelial adhesion and endothelial invasiveness |

| orf19.5636 | RBT5 | 6.7 | 0.7 | 11.0 | 1.0 | GPI-anchored cell wall protein |

| orf19.1327 | RBT1 | 5.7 | 0.8 | 9.7 | 2.0 | Putative cell wall protein with similarity to Hwp1p, required for virulence |

| orf19.1106 | 4.9 | 1.0 | 5.9 | 1.5 | Fluconazole-induced | |

| orf19.5379 | ERG4 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 1.0 | Protein described as similar to sterol C-24 reductase |

| orf19.5265 | KIP4 | 3.6 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 1.1 | Transposon mutation affects filamentous growth; filament induced |

| orf19.5760 | IHD1 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 1.2 | Putative GPI-anchored protein of unknown function; alkaline upregulated; greater transcription in hyphal form than yeast form |

| orf19.2451 | PGA45 | 3.5 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 1.3 | Putative GPI-anchored protein of unknown function |

| orf19.922 | ERG11 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 2.7 | 0.8 | Lanosterol 14-α-demethylase, member of cytochrome P450 family that functions in ergosterol biosynthesis |

| orf19.767 | ERG3 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 0.8 | C-5 sterol desaturase; defects in hyphal growth and virulence |

| orf19.5325 | KIN3 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 1.1 | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Kin3p; induced under Cdc5p depletion |

| orf19.2452 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 1.8 | Transcriptionally regulated by iron | |

| orf19.3104 | YDC1 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 1.0 | Sphingolipid metabolic process |

| orf19.7457 | 3.7 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 0.8 | Unknown function | |

| orf19.1332 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 0.9 | Unknown function | |

| orf19.6705 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 0.7 | Putative guanyl nucleotide exchange factor with Sec7 domain; transcriptionally regulated upon yeast-hyphal switch | |

| orf19.7219 | FTR1 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 1.1 | High-affinity iron permease (ferric citrate, ferrioxamines E or B, transferrin) |

a Information was taken from Candida Genome Database (http://www.candidagenome.org/).

Figure 8.

Verification of genome-wide transcription profiling data. (A) RT-PCR analysis of RAM-dependent hypha-specific genes. (B) Northern analysis of HWP1 transcript. (C) RT-PCR analysis of genes involved in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in C. albicans. mRNAs were extracted from wild-type and CMB3 (Camob2/Camob2), and CCK3 (Cacbk1/Cacbk1) strains cultivated for 1 (B and C) or 2 or 3 h (A) in the presence (H) or absence (Y) of 10% serum. ACT1 was used as an internal control.

Microarray analyses also revealed that the expression of many ergosterol biosynthesis genes, such as ERG3, ERG4, ERG5, ERG6, ERG11, and ERG251, were up-regulated in response to serum in wild-type C. albicans, but not in the Camob2 strain (Figure 8C). A similar lack of response by these genes to serum was observed in the Cacbk1 mutant (Figure 8C). Recently, Mulhern et al. (2006) reported that in the absence of the transcription factor Ace2p, which localizes to the nucleus of the daughter cell with the help of the Cbk1p-Mob2p complex in S. cerevisiae (Weiss et al., 2002), ergosterol biosynthesis genes are down-regulated during hyphal growth (Mulhern et al., 2006). Therefore, our array result suggests that, in response to serum, the RAM signaling network in C. albicans may act through Ace2p to regulate the enhanced expression of ERG genes, which may be necessary for C. albicans to cope with the physiological challenges imposed by serum-containing medium.

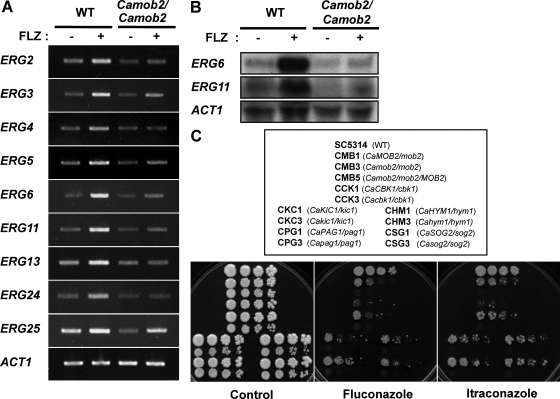

C. albicans RAM Mutants Are Hypersensitive to Azole Antifungal Drugs

Previous studies have shown that a number of ergosterol biosynthesis genes are up-regulated in C. albicans by treatment with azole antifungals (Henry et al., 2000; De Backer et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2005). Therefore, we investigated whether the RAM signaling network is also responsible for the up-regulation of ERG genes in response to azoles in C. albicans. In contrast to wild-type C. albicans, in which exposure to fluconazole significantly elevated the mRNA levels of ERG genes, fluconazole treatment failed to induce expression of ERG genes in the Camob2 mutant (Figure 9, A and B). This result indicates that CaMob2p is important for the induction of ergosterol biosynthesis genes upon exposure to fluconazole, thus implicating the RAM signaling network in the ergosterol-elevating response to physiological challenge by both azole antifungals and serum in C. albicans.

Figure 9.

RAM genes are required for up-regulation of ergosterol biosynthetic genes in response to azole antifungals. (A) RT-PCR analysis. (B) Northern blot analysis. mRNA was extracted from wild-type and CMB3 (Camob2/Camob2) strains cultivated for 1 h in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 10 μg/ml fluconazole. ACT1 was used as an internal control. (C) Test of RAM mutants' susceptibility to azoles. The C. albicans RAM mutants were serially diluted (fivefold) from a stock of cells at OD600 = 0.1. Ten microliters of each serial dilution was spotted onto YPD or YPD media containing fluconazole (10 μg/ml) or itraconazole (0.1 μg/ml), and plates were incubated at 30°C for 4 d.

The failure of C. albicans RAM mutants to increase ERG gene expression in response to fluconazole suggests that these mutants may be hypersensitive to azole antifungals. To address this possibility, we evaluated the growth of Camob2 and Cacbk1 mutants spotted onto YPD media containing fluconazole or itraconazole. The results indicate that the mutants were highly sensitive to the azoles; further, the degree of sensitivity appeared to be dependent on gene dosage (Figure 9C). These data suggest that the RAM signaling network in C. albicans may contribute to azole resistance through the up-regulation of ergosterol synthesis genes.

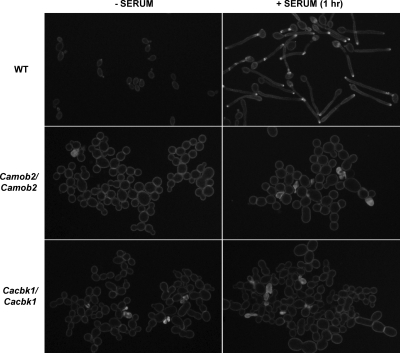

CaMOB2 and CaCBK1 Are Required for Polarization of Lipid Rafts and the Actin Cytoskeleton in C. albicans

The polarization of sterol- and sphingolipid-enriched microdomains (lipid rafts) has been linked to morphogenesis and cell movement in diverse cell types (Alvarez et al., 2007; Hanzal-Bayer and Hancock, 2007) including C. albicans, where it contributes to the ability to grow in a highly polarized manner to form hyphae (Martin and Konopka, 2004). We found that CaMob2p and CaCbk1p were required for serum- and azole-induced transcriptional up-regulation of ergosterol biosynthetic genes (Figures 8C and 9, A, and B). To determine whether the RAM signaling network affected the polarized localization of lipid components in C. albicans, we stained wild-type, Camob2, and Cacbk1 mutant strains with filipin, a fluorescent sterol-binding polyene antibiotic, to detect polarization of lipid components in cells grown as yeast or hyphal forms. During yeast-form growth, wild-type cells stained distinctly at the budding sites, whereas the Camob2 and Cacbk1 mutants showed no intensely stained regions. In the presence of serum, filipin staining was intense at the polarized edge of true hyphae in wild-type cells, whereas in Camob2 and Cacbk1 mutant cells, membrane staining by filipin was essentially uniform, indicating a difference in lipid composition, which may be related to the role of specialized domains, such as lipid rafts (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

CaMob2p and CaCbk1p are required for polarization of lipid rafts. Cells were grown at 30°C in YPD (− SERUM) or at 37°C in YPD medium containing 10% serum (+ SERUM, 1 h), stained with 10 μg/ml filipin for 10 min and then analyzed immediately by UV-fluorescence microscopy.

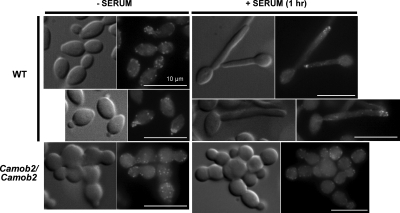

The actin cytoskeleton is important for polarized growth in many cell types. The fact that C. albicans RAM mutant cells lacked polarity and failed to form hypha suggested that the localization pattern of cortical actin patches might be disrupted in these cells. To address this, we stained wild-type and Camob2 mutant cells with rhodamine-phalloidin to visualize the filamentous actin cytoskeleton during yeast and hyphal growth. In contrast to wild-type cells, in which cortical actin patches were polarized at the growing tips, actin patches were randomly distributed in Camob2 mutant cells during yeast growth. When grown in the presence of serum, wild-type C. albicans exhibited highly polarized cortical actin patches at hyphal tips, whereas Camob2 mutant cells failed to polarize cortical actin patches (Figure 11). These results suggest that the RAM signaling network affects actin cytoskeleton polarization in C. albicans during yeast and hyphal growth.

Figure 11.

CaMob2p and CaCbk1p are required for polarization of actin patches. The images show rhodamine-phalloidin staining of wild-type and mutant strains grown at 30°C in YPD (− SERUM) or at 37°C in YPD medium containing 10% serum (+ SERUM, 1 h).

DISCUSSION

Mutations in RAM genes result in the loss of polarized morphogenesis in S. cerevisiae (Racki et al., 2000; Bidlingmaier et al., 2001; Weiss et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2003; Kurischko et al., 2005). In C. neoformans, however, RAM mutations cause constitutive hyperpolarization rather than loss of polarity (Walton et al., 2006). Thus, the conserved components of the RAM signaling network may play divergent roles in regulating cell polarity in different yeast. In this study, we focused on the functions of all components of the C. albicans RAM network—CaCbk1p, CaMob2p, CaKic1p, CaHym1p, CaPag1p, and CaSog2p— with a particular emphasis on their relation to hyphal growth. We found clear evidence that all RAM components operate in the same pathway to positively control polarized growth of C. albicans. Our results also indicate that the SMA domain of CaCbk1p and the Mob1/phocein domain of CaMob2p are essential for the proper function of the CaCbk1p-CaMob2p complex and suggest that this complex might be involved in regulating a subset of Tup1p/Nrg1p-controlled hypha-specific genes under hypha-inducing conditions. Furthermore, the finding that C. albicans RAM mutants cannot enhance expression of ergosterol biosynthesis genes in response to serum and are hypersensitive to azole antifungals implies that the RAM signaling network plays an important adaptive role in C. albicans, adjusting ergosterol levels to enhance survival in adverse environments.

Roles of the RAM Signaling Network during Yeast Growth of C. albicans

All C. albicans RAM mutants exhibited a cell lysis phenotype, which suggests that the RAM signaling network is important in maintaining cell integrity in C. albicans, as it is in S. cerevisiae. In S. cerevisiae, RAM mutants are lethal in strains expressing the SSD1-v allele of the polymorphic SSD1 locus; however, the lethality of RAM mutants is suppressed by the ssd1-d allele, which is null for Ssd1p function, indicating that RAM genes are only required for viability in the presence of functional Ssd1p (Sutton et al., 1991; Du and Novick, 2002; Kurischko et al., 2005). C. albicans SSD1 (CaSSD1) suppressed multiple mutations associated with the functions of SSD1-v in S. cerevisiae, suggesting that these orthologous proteins may play similar roles in a variety of cellular processes (Chen and Rosamond, 1998; Braun et al., 2005). In this study, we found that, although the C. albicans RAM mutants exhibited a cell lysis phenotype, they were viable, indicating that the C. albicans RAM genes were not essential for viability in the CAI4 strain. Because we do not know whether the CaSSD1 allele in the CAI4 strain encodes a fully functional protein, it would be premature to conclude that the RAM genes are not essential even in the presence of functional CaSsd1p in C. albicans. Nonetheless, it is evident that CaSsd1p affected the cell integrity of the C. albicans RAM mutants because the Cassd1Δ mutant was more sensitive to the cell wall–perturbing agents than the wild type, and the severe growth defect of the RAM mutants was at least partially suppressed by the deletion of CaSSD1 (Figure 2C). However, we need to study more to explain why absence of CaSsd1p, which is required for normal cell integrity, alleviates the severe defect in cell integrity of the RAM mutants.

The C. albicans RAM mutant cells failed to separate daughter cell from mother cell and formed clumps that consequently fell rapidly out of suspension in liquid medium. These phenotypes are very similar to those exhibited by a C. albicans ace2 mutant (Kelly et al., 2004; Mulhern et al., 2006), lacking functional Ace2p, which enables the separation of mother and daughter cells by regulating the expression of several cell wall components (O'Conallain et al., 1999; Colman-Lerner et al., 2001; Weiss et al., 2002). Because the activity of Ace2p is affected by the RAM signaling network in S. cerevisiae, we would predict that CaAce2p is also dependent on RAM components, especially the CaCbk1p–CaMob2p complex, for its proper function in C. albicans. C. albicans Ace2p has been also shown to regulate the expression of genes involved in cell separation, such as CaCHT3, CaDSE1, and CaSCW11 (Kelly et al., 2004; Mulhern et al., 2006). Moreover, our observation that the expression levels of CaCHT2, CaCHT3, and CaSCW11 were lower in the Camob2 mutant than in wild-type C. albicans during yeast growth (Figure 2E) is consistent with the previous finding that CaCHT2 and CaCHT3 expression was reduced in a Cacbk1 mutant (McNemar and Fonzi, 2002). The cell-separation defect of the C. albicans RAM mutants thus suggests that the RAM signaling network plays an important role in controlling cytokinesis in C. albicans, possibly through CaAce2p.

Interestingly, we observed that many large, spherical RAM mutants contained two or more nuclei, a phenomenon that has not been reported in S. cerevisiae ace2 or RAM mutants. However, germinating spores of an A. nidulans strain depleted of CotA, a Cbk1p ortholog, have significantly larger volume and more nuclei than wild-type spores, although the nucleus/cell volume ratio was not significantly changed (Johns et al., 2006). Similarly, the multinucleate cells of C. albicans RAM mutants were also much larger in size than normal, single-nucleated cells. It is not clear, however, whether the mechanisms that cause the increase in the number of nuclei in the A. nidulans cotA mutant and C. albicans RAM mutants are analagous. Although further studies will be needed, we suspect that the multinucleation that occurs in the C. albicans RAM mutants is the result of multiple rounds of nuclear division in the absence of bud formation or cytokinesis.

Role of the RAM Signaling Network during Hyphal Growth of C. albicans

It has been shown that deletion of CaCBK1 results in the inability of C. albicans to form hyphae (McNemar and Fonzi, 2002). In this study, we demonstrated that all RAM genes were required for the normal hyphal growth of C. albicans under all laboratory hypha-inducing conditions. We observed little difference in cell morphology among RAM mutants grown in liquid hypha-inducing media, but found that the colony sizes of the Cakic1, Capag1, Cahym1, and Casog2 mutants were significantly smaller than those of Camob2 and Cacbk1 mutants on solid hypha-inducing media. This was especially prominent on serum-containing medium, in which the Cakic1, Capag1, Cahym1, and Casog2 mutants could barely grow. Because these four proteins are thought to function upstream of CaCbk1p to control the activity of the CaCbk1p-CaMob2p complex (Nelson et al., 2003), our results suggest that they may have other function(s) in addition to the activation of the CaCbk1p-CaMob2p complex.

In this study, we found that Camob2 mutants were unable to polarize cortical actin patches to the growing tips of C. albicans. In contrast, cortical actin patches localized normally to growing buds and to the bud neck during vegetative growth of S. cerevisiae mob2 mutant. However, neither S. cerevisiae cbk1 nor mob2 mutants were capable of sustaining actin polarization during mating projection formation in response to pheromone (Weiss et al., 2002). Therefore, it seems likely that the role of the CaCbk1p-CaMob2p complex in C. albicans may be comparable to that in S. cerevisiae with respect to mating projection, but may diverge with respect to bud growth.

Genes Affected by the CaMob2p-CaCbk1p Complex in C. albicans

Using microarray analysis, we identified genes modulated in a RAM-dependent and hypha-specific manner (Table 4). Interestingly, many of the identified genes belonged to a group regulated by the Tup1p-Nrg1p pathway in which the DNA-binding Nrg1p recruits Tup1p to target genes (Braun et al., 2001; Murad et al., 2001). One intriguing possibility suggested by these data are that the CaCbk1p-CaMob2p complex controls the activity of the Nrg1 protein or the expression level of the NRG1 gene. If so, it would be interesting to determine whether such control is mediated directly by the CaCbk1p-CaMob2p complex or indirectly via an unknown CaCbk1p downstream target. Future studies might be expected to reveal the molecular characteristics of such downstream targets, if they exist, and their association with the hyphal morphogenesis of C. albicans.

In this study, we also found that the Camob2 and Cacbk1 mutants, unlike wild-type C. albicans, failed to increase the expression of ergosterol biosynthesis genes during hyphal growth (Figure 8C). Because the deletion of CaACE2 reduces the expression of ergosterol biosynthesis genes (i.e., ERG1, ERG5, ERG11, and ERG251) during hyphal growth (Mulhern et al., 2006), our results suggest that the contribution of the C. albicans RAM signaling network to the increased expression of ergosterol biosynthesis genes during hyphal growth may be mediated by the regulation of CaAce2p activity. It is not clear, however, whether CaAce2p is solely responsible for the up-regulation of ergosterol biosynthesis genes during hyphal growth or whether other downstream effectors of RAM are also involved.

There are several lines of evidence suggesting that ergosterol plays an important role in polarized growth of yeast (Borgers, 1980; Lees et al., 1990; Ha and White, 1999; Bagnat et al., 2000; Sanglard et al., 2003; Martin and Konopka, 2004; Pasrija et al., 2005): 1) Ergosterol, together with sphingolipids, is enriched in lipid rafts, which are polarized in pheromone-induced S. cerevisiae cells and localized at the growing tip of hyphal cells of C. albicans. 2) The expression level of ergosterol biosynthesis genes is associated with the morphogenetic switch from yeast to hyphae and susceptibility to azole antifungal drugs targeting ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in C. albicans. 3) A C. albicans deletion mutant lacking CaERG3 encoding sterol 5,6-desaturase is unable to form hyphae in the presence of serum. 4) A Caerg1 mutant lacking squalene epoxidase lacks the ability to switch from yeast to hyphae and is hypersensitivity to azole antifungals. 5) A Caerg11 mutant deficient in lanosterol 14 α-demethylase exhibits defective hypha formation and is more sensitive to ketoconazole than wild type. In contrast, a Caace2 mutant, in which ergosterol biosynthesis genes were down-regulated compared with wild type, has been reported to maintain the ability to change its morphology under hypha-inducing conditions and form pseudohyphae even under yeast growth condition (Kelly et al., 2004; Mulhern et al., 2006), indicating that the down-regulation of ergosterol biosynthesis genes does not necessarily lead to defective hypha formation in C. albicans. Thus, one might envisage the possibility that critical levels of ergosterol and precursors, or a proper balance between them, may be important for hypha formation in C. albicans. We expect that further analysis of ergosterol and its precursors in RAM and Caace2 mutants derived from the same parental strain may provide additional insight into the relationship between the regulation of ergosterol biosynthesis and the morphogenetic switch in C. albicans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Basic Research Program of the Korea Scientific and Engineering Foundation Grant 2006-0063-2 and the Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Energy IMT-2000.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0272) on October 8, 2008.

REFERENCES

- Adams A. E., Pringle J. R. Staining of actin with fluorochrome-conjugated phalloidin. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:729–731. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94054-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez F. J., Douglas L. M., Konopka J. B. Sterol-rich plasma membrane domains in fungi. Eukaryot. Cell. 2007;6:755–763. doi: 10.1128/EC.00008-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnat M., Keranen S., Shevchenko A., Shevchenko A., Simons K. Lipid rafts function in biosynthetic delivery of proteins to the cell surface in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3254–3259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060034697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidlingmaier S., Weiss E. L., Seidel C., Drubin D. G., Snyder M. The Cbk1p pathway is important for polarized cell growth and cell separation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:2449–2462. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2449-2462.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birse C. E., Irwin M. Y., Fonzi W. A., Sypherd P. S. Cloning and characterization of ECE1, a gene expressed in association with cell elongation of the dimorphic pathogen Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 1993;61:3648–3655. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3648-3655.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgers M. Mechanism of action of antifungal drugs, with special reference to the imidazole derivatives. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1980;2:520–534. doi: 10.1093/clinids/2.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]