Abstract

Loss-of-function mutations in Park2, the gene coding for the ubiquitin ligase Parkin, are a significant cause of early onset Parkinson's disease. Although the role of Parkin in neuron maintenance is unknown, recent work has linked Parkin to the regulation of mitochondria. Its loss is associated with swollen mitochondria and muscle degeneration in Drosophila melanogaster, as well as mitochondrial dysfunction and increased susceptibility to mitochondrial toxins in other species. Here, we show that Parkin is selectively recruited to dysfunctional mitochondria with low membrane potential in mammalian cells. After recruitment, Parkin mediates the engulfment of mitochondria by autophagosomes and the selective elimination of impaired mitochondria. These results show that Parkin promotes autophagy of damaged mitochondria and implicate a failure to eliminate dysfunctional mitochondria in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease.

Introduction

Parkinson's disease is the most common neurodegenerative movement disorder. Although most cases are sporadic, several genes have been recently linked to familial Parkinson's disease, and loss-of-function mutations in Park2, the gene coding for the ubiquitin ligase Parkin, represent the most common recessive cause (Kitada et al., 1998). Although Parkin function has been implicated in several cellular functions, study of Parkin loss in model organisms suggests that Parkin may have a conserved role in maintaining mitochondrial function and integrity (Abou-Sleiman et al., 2006; Hardy et al., 2006). Parkin-null Drosophila melanogaster exhibit a severe phenotype, with the loss of dopaminergic neurons, disrupted spermatogenesis, and swollen and disordered mitochondria appearing before degeneration of their indirect flight muscles (Greene et al., 2003; Whitworth et al., 2005). How Parkin may influence mitochondria function and integrity, however, remains unclear. Here, we demonstrate that Parkin is selectively recruited to dysfunctional mitochondria in mammalian cells, and that after recruitment, Parkin mediates the engulfment of mitochondria by autophagosomes and their subsequent degradation.

Results and discussion

Previous studies yield conflicting conclusions on Parkin subcellular localization, finding the protein in the cytosol or associated with ER or mitochondria (Shimura et al., 1999; Darios et al., 2003; Kuroda et al., 2006). We examined the subcellular localization of endogenous Parkin in HEK293 cells, a cell line that expresses relatively high levels of Parkin, using the PRK8 monoclonal antibody (Pawlyk et al., 2003). Consistent with most studies, we found that endogenous Parkin was predominately located in the cytosol (Fig. 1, a and c). However, in some of the cells, colocalization was observed between Parkin and a subset of the mitochondria, which were small and fragmented (Fig. 1 a).

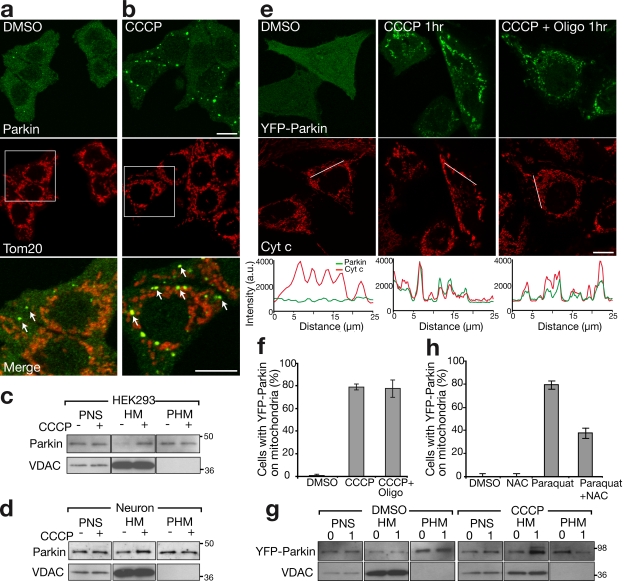

Figure 1.

Parkin accumulates on impaired mitochondria. (a and b) HEK293 cells treated with DMSO control (a) or 10 μM CCCP (b) for 1 h immunostained for endogenous Parkin (green) and a mitochondrial marker, Tom20 (red). The bottom panels show enlarged views of the boxed areas. Arrows indicate mitochondria that colocalize with endogenous Parkin. (c and d) HEK293 cells (c) and rat cortical neurons (d) depolarized with CCCP for 1 and 5 h, respectively. Cells were immunoblotted for endogenous Parkin. PNS, HM, and PHM indicate postnuclear supernatant, mitochondrial-rich heavy membrane pellet, and post–heavy membrane supernatant, respectively. VDAC is a mitochondrial marker. (e) HeLa cells expressing YFP-Parkin (green) treated with DMSO, 10 μM CCCP, or 10 μM CCCP + 10 μM oligomycin for 1 h. Cells were stained for the mitochondrial marker cytochrome c (red). Line scans below the images indicate colocalization between Parkin (green) and mitochondria (red) and correlate to the lines drawn in the images. (f) YFP-Parkin colocalization with mitochondria scored for ≥300 cells per condition in at least two experiments. (g) YFP-Parkin accumulation in mitochondrial fraction assessed as in panel c. Numbers to the right of the gel blots indicate molecular weight standards in kD. (h) HeLa cells treated with 2 mM paraquat or paraquat + 10 mM N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) for 24 h scored for colocalization, as in panel f. Error bars indicate standard deviation of at least three replicates. Bars, 10 μm.

Mitochondrial fission has been recently linked to the function of Parkin (Deng et al., 2008; Poole et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008) and to the autophagy of small defective mitochondria that lack membrane potential (Elmore et al., 2001; Tolkovsky et al., 2002; Twig et al., 2008). To test whether mitochondrial depolarization causes Parkin accumulation on mitochondria, we treated HEK293 cells with the mitochondrial uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP). Within 1 h of adding CCCP, endogenous Parkin was recruited to mitochondria in the majority of cells (Fig. 1 b) and increased appearance in the heavy membrane pellet on Western blots (Fig. 1 c). Although rat cortical neuron cultures displayed more Parkin in the membrane pellet than did HEK293 cells, uncoupling of mitochondria with CCCP increased levels in the membrane pellet (Fig. 1 d). YFP-Parkin expressed in HeLa cells, which have little or no endogenous Parkin expression (Denison et al., 2003; Pawlyk et al., 2003), displayed a cytosolic distribution in >99% of cells. As with endogenous Parkin in HEK293 cells, CCCP exposure induced the redistribution of YFP-Parkin from the cytosol to the mitochondria (Fig. 1, e and f; and Video 1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200809125/DC1). This CCCP-induced accumulation of Parkin on mitochondria was not inhibited by the addition of the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin (which decreases ATP consumption by mitochondrial uncouplers; 78.49 ± 2.61% [mean ± SD] with CCCP alone vs. 77.35 ± 7.64% with CCCP + oligomycin; Fig. 1, e and f). Western blots also show that YFP-Parkin redistributes from the cytosol to the heavy membrane pellet upon CCCP treatment (Fig. 1 g). Additionally, YFP-Parkin was recruited to depolarized mitochondria damaged by the pesticide paraquat, which is thought to increase complex I–dependent reactive oxygen species and has been linked to Parkinsonism (Figs. 1 h, S1, and S2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200809125/DC1; Brooks et al., 1999; Cocheme and Murphy, 2008). CCCP-induced recruitment was not blocked by the antioxidant N-acetyl-cysteine, which suggests that reactive oxygen species production is not necessary for Parkin translocation (Fig. S1). The mitochondrial translocation of Parkin caused by mitochondrial depolarization was also assayed by fluorescence loss in photobleaching (FLIP). Mitochondrial-localized YFP-Parkin in CCCP-treated cells was depleted more slowly by photobleaching than the entire pool of YFP-Parkin in HeLa cells not exposed to CCCP, which suggests that YFP-Parkin's affinity for mitochondria is increased upon depolarization (Fig. 2, a–c).

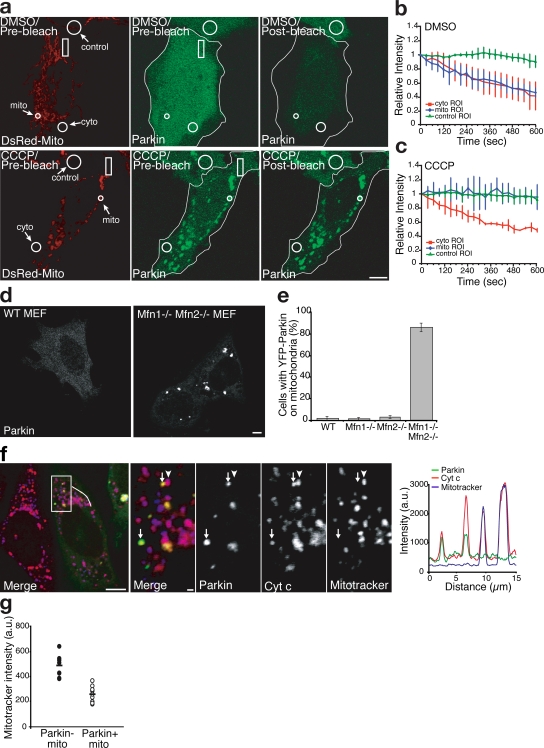

Figure 2.

FLIP analysis of Parkin diffusibility and selectivity of Parkin accumulation. (a–c) FLIP analysis with quantification after treatment with DMSO (a, top, and b) or CCCP (a, bottom, and c; n ≥ 3 in each treatment). Rectangles in panel a indicate the bleach ROI. Outlines demarcate the edges of cells expressing YFP-Parkin. (d) YFP localization in WT and Mfn1−/−,Mfn2−/− double knockout MEF cells expressing YFP-Parkin. (e) YFP-Parkin scored for colocalization as in Fig. 1 f. Error bars indicate standard deviation of at least three replicates. (f) Mfn1−/−,Mfn2−/− double knockout MEF cells transfected with YFP-Parkin (green) and pulsed with the potentiometric dye MitoTracker (blue in merge) 15 min before fixation. Cells were immunostained for cytochrome c (red). A line scan of fluorescence through two Parkin-positive mitochondria depicts colocalization between Parkin, MitoTracker, and cytochrome c. The right four panels show an enlarged view of the boxed area. Arrows indicate mitochondria (identified by anti–cytochrome c) that were depolarized (as assessed by their failure to take up the dye MitoTracker; arrowheads represent mitochondria (identified by anti–cytochrome c) that were electrochemically active (as assessed by their ability to take up the dye MitoTracker). YFP-Parkin colocalizes with depolarized mitochondria (arrows) but not with electrochemically active mitochondria. (g) The mitochondrial volume for each Mfn1−/−,Mfn2−/− MEF cell was segregated into Parkin-positive and Parkin-negative subsets. Mean MitoTracker fluorescence intensity was measured for each subset (n = 9). Bars: (a, d, and f, left) 5 μm; (f, right four panels) 1 μm.

Chronic inhibition of mitochondrial fusion caused by double knockout of the genes expressing the partially redundant mitofusin (Mfn) proteins, Mfn1 and Mfn2, generates a heterogenous population of fragmented mitochondria, some of which are relatively respiratory deficient and display a lower membrane potential (Chen et al., 2005). If Parkin recruitment occurs as a consequence of membrane depolarization, exogenous Parkin in Mfn1−/−,Mfn2−/− double knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) would be predicted to accumulate selectively on mitochondria with lower membrane potentials. YFP-Parkin colocalized with mitochondria in 1.33 ± 1.15% of Mfn1−/− cells and 3.33 ± 1.15% of Mfn2−/− cells, in the range of the 1.99 ± 2% of cells displaying Parkin-positive mitochondria seen with wild-type (WT) MEFs. However, in Mfn1−/−,Mfn2−/− double knockout MEFs, YFP-Parkin colocalized with mitochondria in 86.20 ± 3.95% of cells (Fig. 2, d and e; and Fig. S2; P < 0.001 for Mfn1−/−,Mfn2−/− vs. WT [two-tailed t test]). Interestingly, in Mfn1−/−,Mfn2−/− cells, Parkin was recruited to a discreet subset of mitochondria within individual cells (Fig. 2, d and f). To test whether mitochondria labeled by Parkin display decreased membrane potential, we pulsed the cells with MitoTracker red, a potentiometric mitochondrial dye, before fixation. YFP-Parkin selectively accumulated on those mitochondria with lower MitoTracker staining (Fig. 2 f). To quantify this relationship, we digitally segregated the mitochondrial volume of these cells into Parkin-positive and Parkin-negative sets, and measured the mean MitoTracker intensity of these volumes for each cell. The mitochondrial volume labeled with YFP-Parkin displayed a 47% lower mean MitoTracker intensity relative to the mitochondrial volume with undetectable YFP-Parkin accumulation (Fig. 2 g; 487.00 ± 81.5 arbitrary units [au] vs. 258.3 ± 61.7 au; P < 0.001 [two-tailed, paired t test], n = 9 cells). These results show that Parkin can be recruited to individual mitochondria within cells and that compromised mitochondria display greater Parkin accumulation than electrochemically active mitochondria, which is consistent with the hypothesis that impaired mitochondria are selectively targeted by Parkin.

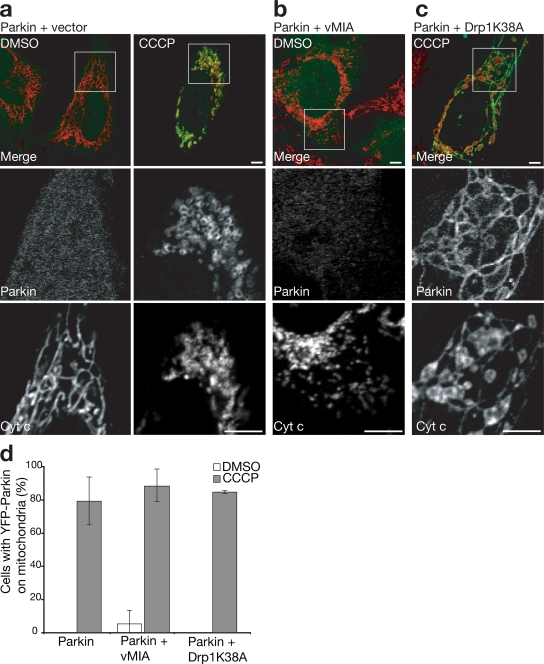

Depolarization of mitochondria is known to induce their fragmentation into multiple smaller organelles (Legros et al., 2002) by inhibiting organelle fusion (Meeusen et al., 2004). Recent genetic studies have linked Parkin activity to gene products controlling mitochondrial fission and fusion (Deng et al., 2008; Poole et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008), which suggests that Parkin recruitment to mitochondria may be a consequence of depolarization-induced fragmentation. To test this hypothesis, fragmentation of mitochondria induced by CCCP (Fig. 3 a) was inhibited by overexpressing Drp1K38A, a dominant-negative mutant of the mitochondrial fission protein dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1; Fig. 3 c; Smirnova et al., 2001). Although mitochondria in CCCP-treated cells expressing Drp1K38A fail to fragment, they still display Parkin accumulation along the elongated mitochondria (Fig. 3, c and d), which indicates that mitochondrial fragmentation is not necessary for Parkin translocation. Expression of viral mitochondrial-associated inhibitor of apoptosis (vMIA) in HeLa cells, which causes fragmentation of mitochondria with minimal perturbation of membrane potential (McCormick et al., 2003), did not cause accumulation of Parkin on mitochondria (Fig. 3, b and d), also indicating that excessive fragmentation of mitochondria by itself is insufficient to cause Parkin recruitment.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial fragmentation does not induce Parkin accumulation independently of mitochondrial membrane potential. (a–d) HeLa cells cotransfected with YFP-Parkin (green) and with empty vector (a), vMIA (b), or Drp1 K38A (c). Cells were treated with 10 μM CCCP (a, right, and c) or DMSO (a, left, and b) for 1 h. Mitochondria were immunostained for cytochrome c (red). The bottom two panels in each column show an enlarged view of the boxed regions. (d) YFP-Parkin colocalization with mitochondria were scored as in Fig. 1 f. Error bars indicate standard deviation of at least three replicates. Bars, 5 μm.

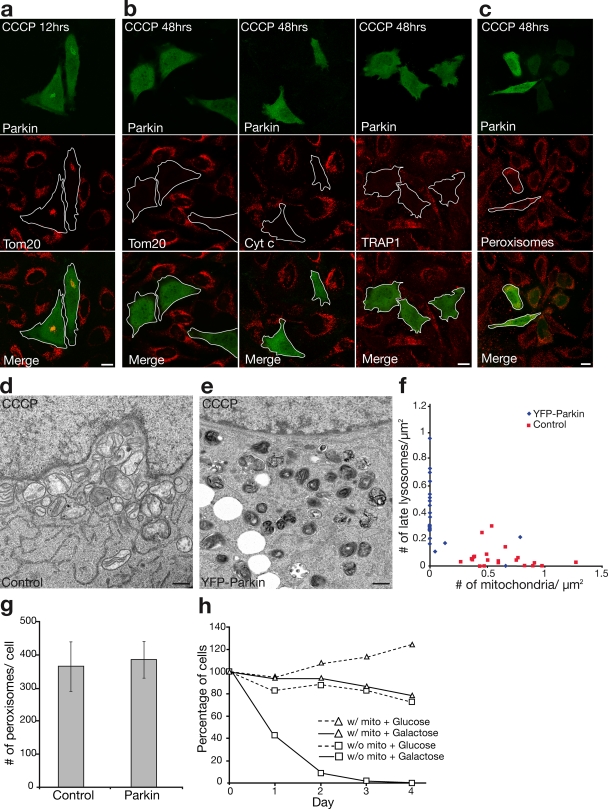

To further assess the effect of Parkin on depolarized mitochondria, we followed changes in mitochondrial morphology and mass over time. In HeLa cells lacking Parkin, the mitochondria appeared fragmented within 60 min after adding CCCP but underwent little other morphological change over the following 48 h (Fig. 4, a and b). In Parkin-expressing cells, in contrast, the mitochondrial mass appeared to be grossly reduced by 12 h (Fig. 4 a). Interestingly, by 48 h, no mitochondria remained detectable in Parkin-expressing cells assessed by immunocytochemistry using three independent mitochondria markers: Tom20, cytochrome c, and TRAP1 (Fig. 4 b). In contrast to the mitochondrial elimination, no significant decrease in the number of peroxisomes was observed (Fig. 4, c and g), which suggests that Parkin selectively induces mitophagy that is consistent with the mitochondria-specific localization upon CCCP treatment.

Figure 4.

Selective mitochondrial elimination by Parkin under depolarizing conditions. (a and b) HeLa cells expressing YFP-Parkin (green) incubated for 12 h (a) or 48 h (b, left) with 10 μM CCCP. Cells were immunostained for Tom20 (red). Parkin-expressing HeLa cells display less mitochondrial mass compared with surrounding cells at 12 h and complete loss of mitochondria by 48 h. (b) Similar loss of mitochondria observed with anti–cytochrome c (red, middle) and anti-TRAP1 (red, right) antibodies. (c) No loss of peroxisomes immunostained for PMP70 (red) in YFP-Parkin–transfected cells relative to surrounding untransfected cells. Outlines demarcate the edges of cells expressing YFP-Parkin. Bars, 10 μm. (d–f) Electron microscopy of untransfected HeLa cells (d) or HeLa cells expressing YFP-Parkin (e) and treated with 10 μM CCCP for 48 h. Many mitochondria and few lysosomes were observed in control cells, and no mitochondria and many lysosomes were observed in YFP-Parkin–transfected cells. Bars, 500 nm. (f) The number of mitochondria and late lysosomes/μm2 of cytoplasm in 22 randomly selected cells per condition. (g) The number of PMP70-stained peroxisomes per cell in YFP-Parkin–transfected and untransfected cells (n = 5). Error bars indicate standard deviation of at least three replicates. (h) Control HeLa cells or HeLa cells transfected with YFP-Parkin treated with 10 μM CCCP for 72 h (day 0) and cultured in glucose or galactose media for 1–4 d. Cells were fixed and stained for Tom20 and Hoechst33342 (nuclei). Cells with nonapoptotic nuclei in a representative area of the slide on days 0–4 were counted and represented in the graph as a percentage of nonapoptotic cells on day 0 (≥160 cells per condition on day 0 in at least two experiments).

We also examined HeLa cell mitochondria by transmission electron microscopy after 48 h of CCCP treatment in the presence and absence of Parkin expression. Mitochondria were abundant in the control HeLa cells after CCCP treatment, although they appeared fragmented and had sparse cristae (Fig. 4 d). However, 90% of HeLa cells expressing YFP-Parkin had either few or no detectable mitochondrial structures (Fig. 4, e and f; 0.074 ± 0.21 mitochondria/μm2 of cytoplasm with Parkin vs. 0.62 ± 0.06 mitochondria/μm2 of cytoplasm without Parkin; P < 0.001, n = 22 cells per condition). Furthermore, Parkin-expressing HeLa cells lacking mitochondria displayed a large increase in electron dense lysosomal structures (Fig. 4, e and f; 0.38 ± 0.23 lysosomes/μm2 cell area with Parkin vs. 0.06 ± 0.08 lysosomes/μm2 of cytoplasm without Parkin; P < 0.001, n = 22 cells per condition).

To further confirm that cells had lost their mitochondria, we examined their growth in glucose media or galactose media, which lacked glucose. 72.8% of cells without detectable mitochondria were able to survive for 4 d in glucose media, whereas 0% were able to survive 4 d when cultured in galactose media (Fig. 4 h). In contrast, the majority of control cells, which had been treated with CCCP but lacked Parkin, retained their mitochondria and could survive in both glucose and galactose media for at least 4 d (Fig. 4 h). These results provide biochemical evidence that cells expressing Parkin lack mitochondrial function after depolarization, which is consistent with their having been eliminated.

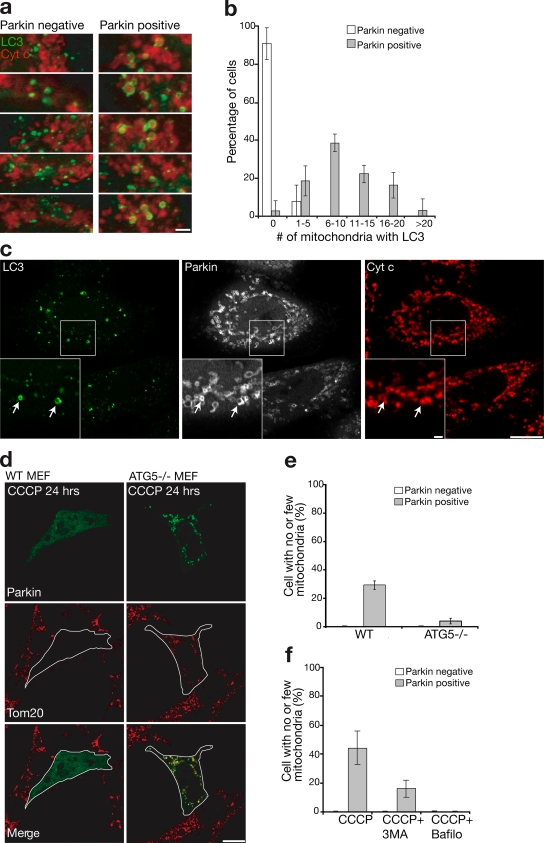

Previous studies in mammalian cells (Elmore et al., 2001; Schweers et al., 2007; Sandoval et al., 2008; Twig et al., 2008) have concluded that depolarized mitochondria are degraded by autophagy. To test whether Parkin may be regulating this process, we assessed colocalization between a marker of autophagosomes, LC3, and mitochondria after mitochondrial depolarization using HeLa cells stably transfected with GFP-LC3 (Bampton et al., 2005). Little colocalization between mitochondria and autophagosomes was seen after 1 h of CCCP exposure in untransfected HeLa cells (Fig. 5 a, left). However, LC3-labeled structures surrounded fragmented mitochondria in cells transfected with mCherry-Parkin specifically after CCCP treatment (Fig. 5 a, right) to a significantly greater extent than in the Parkin-deficient HeLa cells (10.55 ± 6.06 vs. 0.09 ± 0.36 LC3 encompassed mitochondria per cell; two-sided t test, P < 0.001; Fig. 5 b). Consistent with the conclusion that Parkin accumulates on mitochondria destined for autophagy, Parkin colocalizes with LC3 after CCCP treatment (Fig. 5 c) but not before (not depicted).

Figure 5.

Mitophagy induced by Parkin. (a) HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 (green) transfected with mCherry-Parkin (not depicted) and treated with 10 μM CCCP for 1 h. Parkin-negative cells (left) display less overlap between autophagosomes and mitochondria (red) than Parkin-positive cells (right), as assessed by (b) counting the number of mitochondria encapsulated by LC3-positive autophagosomes in >30 cells per condition in at least three independent experiments. (c) HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 (green) and transiently transfected with mCherry-Parkin (white) were immunostained for cytochrome c (red) to reveal colocalization of LC3, Parkin, and mitochondria after 1 h exposure to CCCP. Arrows indicate mitochondria that colocalize with both mCherry-Parkin and GFP-LC3. Insets show an enlarged view of the boxed areas. (d) YFP-Parkin (green)-induced mitochondrial removal after 24 h of CCCP (10 μM) exposure observed in WT MEFs (left) failed to occur in ATG5−/− MEFs (right) quantified (e) in ≥150 cells in at least three experiments. Cells were stained for Tom20 (red). Outlines demarcate the edges of cells expressing YFP-Parkin. (f) 3-methyladenine (3MA) and bafilomycin blocked Parkin-induced mitophagy in HeLa cells quantified as in panel e. Error bars indicate standard deviation of at least three replicates. Bars: (c and d) 10 μm; (a and c, insets) 1 μm.

To experimentally test if Parkin mediates mitochondrial elimination by autophagy, we examined Parkin activity in ATG5−/− MEFs that lack a key component of the autophagy pathway (Hara et al., 2006). Supporting the hypothesis that Parkin promotes autophagic degradation of impaired mitochondria, cells lacking ATG5 retain Parkin-targeted mitochondria after CCCP treatment (Fig. 5, d and e). Likewise, bafilomycin, a lysosomal inhibitor, and 3-methyl adenine, an inhibitor of autophagy, blocked Parkin-induced mitophagy in HeLa cells (Figs. 5 f and S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200809125/DC1).

We have shown that Parkin is recruited to depolarized mitochondria and that Parkin promotes their autophagic degradation. Spontaneous mitochondrial depolarization and depolarization after phototoxicity have been associated with mitophagy in mammalian cells (Kim et al., 2007; Twig et al., 2008). Although little is known about the proteins regulating this process in mammalian cells, recently, BNIP3L/NIX was found to promote degradation of mitochondria in reticulocytes by triggering the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Schweers et al., 2007; Sandoval et al., 2008). Our findings provide a new molecular link between mitochondrial membrane depolarization and autophagy by identifying Parkin as a mediator of mitophagy downstream of mitochondrial depolarization.

We do not know the extent to which Parkin mediates mitochondrial fidelity in vivo. Long-lived cells may require greater mitochondrial quality control than dividing cell populations that can discard damaged mitochondria wholesale by eliminating defective cells. Thus, certain cell types, such as neurons and myocytes, may require more robust intracellular mitochondrial surveillance than proliferating cell populations. Furthermore, it remains unknown to what extent alternative factors may promote mitophagy downstream of mitochondrial depolarization in different cell types or concurrently in the same cell.

In D. melanogaster, knockout of mitochondrial fusion genes can partially compensate for loss of Parkin phenotypes, which suggests that Parkin may normally facilitate mitochondrial fission (Deng et al., 2008; Poole et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008). Our data support the view that Parkin has a less direct mode of compensating for defects in mitochondrial fusion and fission. Mitochondrial fragmentation does not itself signal Parkin recruitment, but a severe defect in mitochondrial fusion does trigger recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria if they lose membrane potential. Additionally, mitochondrial fission appears to be a prerequisite for mitophagy (Twig et al., 2008). Thus, excess fission may compensate for Parkin loss in the fly by promoting mitophagy (Deng et al., 2008; Poole et al., 2008).

Parkin overexpression also has been shown to compensate for loss of Pink1 in D. melanogaster (Clark et al., 2006; Park et al., 2006). Our results suggest that Parkin may compensate by targeting impaired Pink1-deficient mitochondria for degradation. Knockdown of Pink1 leads to reduced HeLa cell mitochondrial membrane potential (Exner et al., 2007), which suggests that Parkin could maintain fidelity of mitochondria by activating the autophagy of dysfunctional mitochondria resulting from Pink1 loss.

Most importantly, our results suggest that loss of Parkin activity may allow the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, leading to neuron loss in Parkinson's disease, and that Parkin normally functions to survey mitochondrial activity and maintain mitochondrial fidelity by activating the autophagy of damaged organelles.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HeLa cells stably expressing YFP-Parkin using the Flp-In system (Invitrogen) were creating according to the manufacturer's instructions and maintained in 300 μg/ml hygromycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Rat cortical neurons were isolated on embryonic day 18 and grown in neurobasal media supplemented with B-27, l-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin. All cell culture materials were obtained from Invitrogen and all chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Chemicals were prepared from DMSO stock solutions, except paraquat, N-acetyl-cysteine, and 3-methyladenine, which were added fresh to media. Mfn1−/−,Mfn2−/− and Mfn1−/−,Mfn2−/− double knockout MEFs were generously donated by D.C. Chan (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA), ATG5−/− MEFs were donated by N. Mizushima (Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan), Flp-In HeLa cells were donated by V.V. Lobanenkov (National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD), and HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 were donated by A. Tolkovsky (Cambridge University, Cambridge, UK).

Transfection/immunocytochemistry

Cultured cells seeded in borosilicate chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were transfected or cotransfected with YFP-Parkin, ECFP-Parkin, mCherry-Parkin, DsRed-Mito (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.), pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen), vMIA, and/or Drp1K38A constructs using Fugene 6 (Roche). Parkin-myc was a gift from M. Cookson (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Cells were fixed 12–24 h after transfection with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were stained with following primary antibodies: mouse monoclonal cytochrome c (BD), rabbit polyclonal Tom20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse monoclonal Parkin PRK8 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit polyclonal PMP70 (Invitrogen), and/or mouse monoclonal TRAP1 (Abcam); and with the following secondary antibodies: mouse and/or rabbit Alexa 488, 594, and 633 (Invitrogen). For assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential, cells were pulsed with 50 nM MitoTracker red (Invitrogen) for 15 min, washed, and incubated for an additional 10 min before fixation or imaging. For assessment of cell metabolic potential, cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen).

Confocal microscopy

Fixed cells and live cells in the FLIP assay were imaged using an inverted microscope (LSM510 Meta; Carl Zeiss, Inc.) with a 63×/1.4 oil DIC Plan Apo objective at 25°C and 37°C, respectively. For the FLIP assay, a bleach region of interest (ROI) occupying approximately one eighth of the cell was positioned over a relatively mitochondria-free portion of the cytosol. Cells were alternately bleached (488 nm using a 30-mW argon laser at 75% power and 100% transmission for 150 iterations) and imaged (488 nm at 75% power and 2% transmission) for 10 min (∼60 cycles over the length of the experiment). Two-channel prebleach and postbleach images were obtained with 488 and 594 lasers to assess the position of mitochondria before and after bleaching. Circular ROIs with diameters of ∼1 and 5 μm, respectively, were placed over the mitochondria and cytosol of the target cell, and an ROI of 10 μm was placed over the control cell. Imaging of YFP-Parkin translocation in live HeLa cells was performed on a live cell imager system (UltraView LCI; PerkinElmer) at 35°C with a 100×/1.45 α-Plan-Fluor objective.

Image analysis

Image contrast and brightness were adjusted in Photoshop (Adobe). Colocalization was assessed with line scans using MetaMorph (MDS Analytical Technologies). For analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential in cells, mitochondrial voxels in each image (the cytochrome c channel threshold was ≥400 au) were segregated into Parkin-positive (the YFP-Parkin channel threshold was ≥1,100 au) or Parkin-negative subsets, and MitoTracker intensity for each voxel was measured using Volocity software (Improvision). For each cell, the mean MitoTracker intensity per voxel was calculated for the Parkin-positive and Parkin-negative subsets. The difference in mean MitoTracker intensity between the Parkin-positive and Parkin-negative subsets was calculated using a paired t test.

Western blotting

HeLa cells stably expressing YFP-Parkin, HEK293 cells, and rat cortical neurons 2 d in vitro were harvested and fractionated as described previously (Karbowski et al., 2007). Samples were run on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the following antibodies: polyclonal rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen), mouse monoclonal anti-Parkin (PRK8), and mouse monoclonal anti-Porin 31HL (EMD).

Electron microscopy

HeLa cells transfected with YFP-Parkin for 18 h were sorted for YFP using FACS. After sorting, 99.7% of cells contained a detectable YFP signal. After overnight culture, cells were treated with 10 μM CCCP for 48 h, fixed with 4% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 N sodium-cacodylate at room temperature for 1 h, and processed for electron microscopy using a standard protocol. 22 cells expressing Parkin and 22 untransfected cells were randomly selected and imaged at 8,000× magnification by transmission electron microscope (200CX; JEOL Ltd.) and a digital camera system (XR-100; Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Corp.). The area of cytoplasm in each cell was calculated using National Institutes of Health ImageJ.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows YFP-Parkin recruitment to mitochondria after paraquat and CCCP + N-acetyl-cysteine. Fig. S2 shows ECFP-Parkin recruitment to Mfn1−/− and Mfn2−/− cells and selective recruitment of YFP-Parkin to depolarized mitochondrial in HeLa cells after paraquat. Fig. S3 shows a block of mitophagy by 3-methyladenine and bafilomycin. Video 1 depicts YFP-Parkin recruitment to mitochondria after depolarization with CCCP in HeLa cells. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200809125/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Smith, T.-H. Tao-Cheng, and M. Cleland for help with confocal and electron microscopy, M. Cookson for Parkin-myc; D.C. Chan for Mfn1−/−, Mfn2−/−, and Mfn1−/−,Mfn2−/− MEFs; N. Mizushima for ATG5−/− MEFs; V.V. Lobanenkov for Flp-In HeLa cells; and A. Tolkovsky for HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-LC3.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health intramural program and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Research Fellowship for Japanese Biomedical and Behavioral Researchers (to A. Tanaka).

Abbreviations used in this paper: au, arbitrary units; CCCP, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone; Drp1, dynamin-related protein 1; FLIP, fluorescence loss in photobleaching; Mfn, mitofusin; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; ROI, region of interest; vMIA, viral mitochondrial-associated inhibitor of apoptosis; WT, wild type.

References

- Abou-Sleiman, P.M., M.M. Muqit, and N.W. Wood. 2006. Expanding insights of mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7:207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bampton, E.T., C.G. Goemans, D. Niranjan, N. Mizushima, and A.M. Tolkovsky. 2005. The dynamics of autophagy visualized in live cells: from autophagosome formation to fusion with endo/lysosomes. Autophagy. 1:23–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, A.I., C.A. Chadwick, H.A. Gelbard, D.A. Cory-Slechta, and H.J. Federoff. 1999. Paraquat elicited neurobehavioral syndrome caused by dopaminergic neuron loss. Brain Res. 823:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H., A. Chomyn, and D.C. Chan. 2005. Disruption of fusion results in mitochondrial heterogeneity and dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 280:26185–26192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, I.E., M.W. Dodson, C. Jiang, J.H. Cao, J.R. Huh, J.H. Seol, S.J. Yoo, B.A. Hay, and M. Guo. 2006. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature. 441(7097):1162–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocheme, H.M., and M.P. Murphy. 2008. Complex I is the major site of mitochondrial superoxide production by paraquat. J. Biol. Chem. 283:1786–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darios, F., O. Corti, C.B. Lucking, C. Hampe, M.P. Muriel, N. Abbas, W.J. Gu, E.C. Hirsch, T. Rooney, M. Ruberg, and A. Brice. 2003. Parkin prevents mitochondrial swelling and cytochrome c release in mitochondria-dependent cell death. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12:517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H., M.W. Dodson, H. Huang, and M. Guo. 2008. The Parkinson's disease genes pink1 and parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:14503–14508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison, S.R., F. Wang, N.A. Becker, B. Schule, N. Kock, L.A. Phillips, C. Klein, and D.I. Smith. 2003. Alterations in the common fragile site gene Parkin in ovarian and other cancers. Oncogene. 22:8370–8378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore, S.P., T. Qian, S.F. Grissom, and J.J. Lemasters. 2001. The mitochondrial permeability transition initiates autophagy in rat hepatocytes. FASEB J. 15:2286–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner, N., B. Treske, D. Paquet, K. Holmström, C. Schiesling, S. Gispert, I. Carballo-Carbajal, D. Berg, H.H. Hoepken, T. Gasser, et al. 2007. Loss-of-function of human PINK1 results in mitochondrial pathology and can be rescued by parkin. J. Neurosci. 27(45):12413–12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J.C., A.J. Whitworth, I. Kuo, L.A. Andrews, M.B. Feany, and L.J. Pallanck. 2003. Mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration in Drosophila parkin mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:4078–4083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara, T., K. Nakamura, M. Matsui, A. Yamamoto, Y. Nakahara, R. Suzuki-Migishima, M. Yokoyama, K. Mishima, I. Saito, H. Okano, and N. Mizushima. 2006. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 441:885–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, J., H. Cai, M.R. Cookson, K. Gwinn-Hardy, and A. Singleton. 2006. Genetics of Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism. Ann. Neurol. 60:389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowski, M., A. Neutzner, and R.J. Youle. 2007. The mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligase MARCH5 is required for Drp1 dependent mitochondrial division. J. Cell Biol. 178:71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I., S. Rodriguez-Enriquez, and J.J. Lemasters. 2007. Selective degradation of mitochondria by mitophagy. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 462:245–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada, T., S. Asakawa, N. Hattori, H. Matsumine, Y. Yamamura, S. Minoshima, M. Yokochi, Y. Mizuno, and N. Shimizu. 1998. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 392:605–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, Y., T. Mitsui, M. Kunishige, M. Shono, M. Akaike, H. Azuma, and T. Matsumoto. 2006. Parkin enhances mitochondrial biogenesis in proliferating cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15:883–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legros, F., A. Lombes, P. Frachon, and M. Rojo. 2002. Mitochondrial fusion in human cells is efficient, requires the inner membrane potential, and is mediated by mitofusins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:4343–4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, A.L., V.L. Smith, D. Chow, and E.S. Mocarski. 2003. Disruption of mitochondrial networks by the human cytomegalovirus UL37 gene product viral mitochondrion-localized inhibitor of apoptosis. J. Virol. 77:631–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeusen, S., J.M. McCaffery, and J. Nunnari. 2004. Mitochondrial fusion intermediates revealed in vitro. Science. 305:1747–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, J., S.B. Lee, S. Lee, Y. Kim, S. Song, S. Kim, E. Bae, J. Kim, M. Shong, J.M. Kim, and J. Chung. 2006. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila PINK1 mutants is complemented by parkin. Nature. 441(7097):1157–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlyk, A.C., B.I. Giasson, D.M. Sampathu, F.A. Perez, K.L. Lim, V.L. Dawson, T.M. Dawson, R.D. Palmiter, J.Q. Trojanowski, and V.M. Lee. 2003. Novel monoclonal antibodies demonstrate biochemical variation of brain parkin with age. J. Biol. Chem. 278:48120–48128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole, A.C., R.E. Thomas, L.A. Andrews, H.M. McBride, A.J. Whitworth, and L.J. Pallanck. 2008. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:1638–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, H., P. Thiagarajan, S.K. Dasgupta, A. Schumacher, J.T. Prchal, M. Chen, and J. Wang. 2008. Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of erythroid cells. Nature. 454:232–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweers, R.L., J. Zhang, M.S. Randall, M.R. Loyd, W. Li, F.C. Dorsey, M. Kundu, J.T. Opferman, J.L. Cleveland, J.L. Miller, and P.A. Ney. 2007. NIX is required for programmed mitochondrial clearance during reticulocyte maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:19500–19505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimura, H., N. Hattori, S. Kubo, M. Yoshikawa, T. Kitada, H. Matsumine, S. Asakawa, S. Minoshima, Y. Yamamura, N. Shimizu, and Y. Mizuno. 1999. Immunohistochemical and subcellular localization of Parkin protein: absence of protein in autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism patients. Ann. Neurol. 45:668–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova, E., L. Griparic, D.L. Shurland, and A.M. van der Bliek. 2001. Dynamin-related protein Drp1 is required for mitochondrial division in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12:2245–2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolkovsky, A.M., L. Xue, G.C. Fletcher, and V. Borutaite. 2002. Mitochondrial disappearance from cells: a clue to the role of autophagy in programmed cell death and disease? Biochimie. 84:233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twig, G., A. Elorza, A.J. Molina, H. Mohamed, J.D. Wikstrom, G. Walzer, L. Stiles, S.E. Haigh, S. Katz, G. Las, et al. 2008. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 27:433–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth, A.J., D.A. Theodore, J.C. Greene, H. Benes, P.D. Wes, and L.J. Pallanck. 2005. Increased glutathione S-transferase activity rescues dopaminergic neuron loss in a Drosophila model of Parkinson's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:8024–8029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., Y. Ouyang, L. Yang, M.F. Beal, A. McQuibban, H. Vogel, and B. Lu. 2008. Pink1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with the fission/fusion machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:7070–7075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]