Abstract

Introduction

Among rural children with asthma and their parents, this study examined the relationship between parental and child reports of quality of life and described the relationship of several factors such as asthma severity, missed days of work and asthma education on their quality of life.

Method

Two hundred and one rural families with asthma were enrolled in a school-based educational program. Intervention parents and children received interactive asthma workshop(s), asthma devices and literature. Parent and child quality of life measurements were obtained pre and post intervention using Juniper's Paediatric Caregivers Quality of Life and Juniper's Paediatric Quality of Life Questionnaires. Asthma severity was measured using criteria from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines.

Results

There was no association between parent and child total quality of life scores, and mean parental total quality of life scores were higher at baseline and follow-up than those of the children. All the parents' quality of life scores were correlated with parental reports of missed days of work. For all children, emotional quality of life (EQOL) was significantly associated with parental reports of school days missed (p= .03) and marginally associated with parental reports of hospitalizations due to asthma (p=.0.08). Parent's emotional quality of life (EQOL) and activity quality of life (AQOL) were significantly associated with children's asthma severity (EQOL, p=.009, AQOL, p=0.03), but not the asthma educational intervention. None of the child quality of life measurements were associated with asthma severity.

Discussion

Asthma interventions for rural families should help families focus on gaining and maintaining low asthma severity levels in order for families to enjoy an optimal quality of life. Health care providers should try to assess the child's quality of life at each asthma care visit independently of the parents.

Introduction

Quality of life is defined by the individual and depends on many factors such as lifestyle, past experiences, hopes for the future, dreams and ambitions (Eisner & Morse, 2001). Quality of life for a child with asthma has been defined as the measure of emotions, asthma severity/symptoms, emergency department visits, missed school days, activity limitations and visits to the emergency department (Juniper, 1997). Several studies of children with asthma have indicated that the child's quality of life reports may differ from those of their parents (Callery, Milnes, Verduyn & Couriel, 2003; Sawyer et al., 2005). In addition, quality of life reports from children and parents living in rural settings may differ from those of urban parents and children (Weinert & Burman, 1994).

For rural individuals, quality of life is perceived as the ability to work, function, and perform daily tasks in the absence or presence of symptoms as compared to urban parents who may view health as the absence of disease (Weinert & Burman, 1994). Moreover, rural families face access to care barriers such as long distances to primary care practitioners or hospital emergency departments and have fewer social and health care resources than urban dwellers (Horner, 2006). These barriers leave the family primarily to care for the child's asthma management in the home (Horner & Fouladi, 2003). In fact, research shows that these barriers are affecting the care received by rural families in comparison to urban families. Rural children with asthma are half as likely to see an asthma specialist or to receive care in an emergency department compared to urban children (Horner; Yawn, Mainous, Love & Hueston, 2001).

Regardless of the definition of quality of life and despite differences in definitions between rural and urban families, most studies indicate that children with asthma and their families experience significant decreases in quality of life. On average, U.S. children with asthma miss 1.5 more days of school than children without asthma (Moonie, Sterling, Figgs & Castro, 2006). In addition, Handelman, Rich, Bridgemohan and Schneider (2004) reported that 25% of children with asthma and 76% of mothers of children with asthma feared mortality due to asthma. Asthma not only increases school absenteeism and fears, but it also decreases physical activity for children with asthma. Glazebrook et al. (2006) reported that two-thirds of children with asthma stated that asthma stopped them from doing sports and limited their activity based on reports of an average of two fewer activities per day than children without asthma, (4 activities per day vs. 6 activities per day). For parents of children with asthma a decreased quality of life is related to missed workdays, limited activities, inadequate sleep, frequent night awakenings and decreased emotional health. In addition, several studies have also indicated a negative relationship between symptom frequency and parental quality of life scores (Halterman et al., 2004; Osman, Baxter-Jones & Helms, 2001)

The purpose of this article is to examine the relationship between child and parental quality of life and to describe the relationship among several factors such as demographic variables, asthma severity, missed days of work, asthma education and quality of life in rural children with asthma and their parents/caregivers. Data on quality of life were collected as part of a larger study funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), NIH (NR05062) to evaluate the effectiveness of a school based asthma education intervention for rural elementary school age children with asthma (Butz et al., 2005).

Methods

Overview of the study

The larger NINR study was a two group, repeated longitudinal measure, randomized clinical trial that evaluated the effectiveness of a school based asthma education program that delivered asthma care to children with asthma, their parents/caregivers, and their school health nurses. Two hundred- twenty one children with asthma and their families were enrolled into this study. One hundred and thirty families were randomized into the intervention group, and ninety-one families into the control group. Quality of life data were available for 201 children and their parents (20 families did not complete the follow-up surveys (Butz et al, 2005)). The children were recruited through school nurses who sent letters regarding the study to all children with asthma in their respective schools. Children then returned the “permission slip” portion of the letter to the school nurse giving permission for a study member to call to enroll them. A total of 41 elementary schools in 7 rural counties in Maryland participated. Schools were randomized at the county level to avoid control and intervention children attending the same school (Butz, et al.; Winkelstein et al, 2006).

To be eligible for the study, children had to be in grades kindergarten to fourth grade at the time of recruitment, have an asthma diagnosis from a qualified health professional, i.e. physician or nurse practitioner, take asthma medication, and have at least one of the following symptoms in the past 12 months: wheezing, shortness of breath, night time cough, daytime cough, wheezing with exercise or colds. Children whose parents reported that they were developmentally delayed were excluded due to the need for the child to understand the educational component of the intervention. Baseline and follow- up telephone surveys of the parents/caregivers were used to assess demographics variables, asthma symptoms, missed days of work, and quality of life reports. If parents could not be contacted by phone, home visits were conducted to complete baseline or follow-up surveys.

Baseline and follow-up face –to- face interviews of the children were conducted in the elementary schools by research assistants (RA) to assess quality of life (QOL) in the children. For children under 7 years of age, the QOL instruments were administered by a RA during a one-on-one session with the child. The RA read the questions so that the child could fill in their response. For children over age 7, the questions were read by a RA to children in a group setting. Children independently completed their own responses on the QOL instrument. The follow-up surveys for parents and children were administered approximately 10 months after the baseline survey. This data collection time point corresponded with the end of the school year (Butz, et. al, 2005).

Theoretical Framework

Because quality of life is an outcome influenced by multiple factors, the PRECEDE model was used as the theoretical framework for this study (Green, Keuter, Deeds & Patridge, 1980). The PRECEDE model demonstrates how predisposing, enabling and reinforcing factors may influence a health outcome, such as quality of life. Predisposing factors precede a behavior and provide rationale and motivation for behavior change; Enabling factors precede the behavior and are created by society/social systems and they also influence behavior; Reinforcing factors provide incentive to change or maintain a behavior. Our hypothesis was that rural school age children with asthma experience reduced quality of life because of suboptimal asthma knowledge and management and decreased communication between the school health nurse/ personnel (SHP), the child's primary care provider (PCP) and the parent.

Using the PRECEDE model, we targeted the predisposing factors of insufficient asthma knowledge and management, the rural concepts of self reliance, hardiness and reliance on social networks and the self efficacy of the parent, child and school health personnel. The enabling factors of the study were asthma management skills, asthma resources, rural concepts of “insider/outsider” and communication between the parent, SHP and PCP. The intervention targeted reinforcing factors to improve asthma knowledge and management by including a rural resource guide and coloring book, free peak flow meters and spacers, device demonstrations, nurse consultants, a community health worker that was from the target area, and other mainstream asthma information. The quality of life, self efficacy and asthma knowledge and management of the parent, the asthma knowledge and self efficacy of the SHP's and increased frequency of communications between the parent, child and SHP were all behavioral/intermediate outcomes of the study. The child's quality of life was the primary outcome variable of the study.

Quality of Life Instruments

Juniper's Paediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ) (Juniper et al., 1996a) was used to measure child QOL and was administered to all child participants pre and post intervention by a RA. This tool consists of 23 items that measure the emotional QOL (8 items), activity QOL (5 items) and symptom QOL (10 items) of children with asthma ages 7- 17. All items are equally weighed. Responses are scored on a 7 point Likert scale with a score of 1 indicating maximum impairment or poor QOL and 7 indicating no impairment or good QOL. The responses from all three domains (emotional, activity and symptom) are totaled respectively and then combined for an overall child quality of life score. The intraclass correlation coefficients for children ages 7 to 10 were 0.89 for overall quality of life, 0.68,0.83 and 0.87, respectively, for the subscales- emotional, activity, symptom (Juniper et al, 1996a). The cross sectional correlations between asthma quality of life and clinical asthma control for the three domains- symptoms, activity and emotions subscales were -0.61, -0.62, -0.37 respectively (Juniper et al, 1996a).

To measure caregiver QOL the Juniper's Pediatric Caregiver Quality of Life Questionnaire (PCQOLQ) (Juniper et al., 1996b) was administered to all parent/ caregivers pre and post intervention. This tool consists of 13 items measured on a 7 point likert scale with a range of scores between 13 to 91. Lower scores indicated impaired or poor quality of life. This tool, unlike the child quality of life tool, only contained activity (AQOL) and emotional quality of life (EQOL) domains, which when combined comprised the parent/caregiver's total quality of life (TQOL) score. The intraclass correlation coefficients for the total PCQOLQ score, the emotional and the activity domains were .80 to .85. (Juniper et al, 1996b). The cross sectional correlations between caregiver quality of life and clinical asthma control for the two domains-activity and emotions subscales were -0.30 and -0.29 respectively.

Demographic and Healthcare Utilization Variables

Demographic variables including age, gender, ethnic grouping, educational level, household income, and missed days of school, number of hospitalizations, and missed days of work were ascertained at baseline and follow- up using surveys administered to the parents/caregivers. Health status and health care items included the number of missed school days for their child in the past year due to asthma, the number of times the child was admitted to the hospital and the number of days the parent missed work to care for their child's asthma in the last six months.

Asthma Severity

Several items were used to assess the frequency of the child's daytime and nighttime asthma symptoms in the past 6 months. Asthma severity questions asked about symptom frequency including cough, wheeze, shortness of breath and chest tightness. For example, one symptom item asked, “In the past 6 months has (child's name) had cough?” Parents/caregivers selected one of the following responses: zero times a week, 1 or 2 times a week, 3 to 6 times a week, 7 to 10 times a week, or more than 10 times a week. Using parent reported symptom data and the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines (NAEPP, 1997), children were categorized into one of the following four categories of asthma severity: mild intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent and severe persistent.

Asthma Education Program

The intervention group received an asthma education workshop and written educational materials which included information on asthma triggers, the warning signs of asthma attacks, asthma pathophysiology, environmental factors, asthma medications and asthma devices such as peak flow meters, spacers and metered dose inhalers. In addition, a rural resource guide of local and national asthma coalitions, asthma support groups, hotlines etc. was provided to intervention participants. Children and their parents who were randomized into the control group received no educational workshops or materials until after completion of all follow-up data collection except that the SHP's of children in the control group and intervention group received the asthma resource guide and a brief workshop on asthma pathophysiology at the beginning of the study. The control group parents and children met in the schools and interacted with the research assistants twice to fill out pre and post surveys. Details of the A+ Asthma educational intervention, the educational resources given to the SHPs and the asthma coloring book used in the educational intervention are provided in previous publications (Butz et al., 2005; Naumann et al., 2004, Winkelstein et al., 2006).

Data Analysis

Total and subscale quality of life (TQOL, AQOL and EQOL) scores were calculated for each caregiver and child. Frequency distributions for all variables were examined across parent and child intervention and control groups. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to compare caregiver/parent and child total and subscale quality of life scores. Mean scores on the total and subscale measures were compared by asthma severity level using the student's t-test. Statistical significance was accepted as p<0.05. All analyses utilized STATA statistical software v. 7.0 and v. 2.0.1 (R Development Core Team, 2004).

Results

Children and Parent Demographics

Most children were Caucasian (56%), males (62%) with a mean age of 8 years (S.D. 1.7 years); The mean age of the parent/caregivers was 36.2 years (S.D. = ± 8.0 years). Most parents/caregivers were women (89.6%), had at least a high school education (90%), and the majority of parents/caregivers had a yearly income of $30,000 or more (68.8%) (see Table). There was no significant relationship or correlation between any of the demographic variables and the quality of life scores of the children or parents/caregivers.

Table.

Sociodemographic/Health Characteristics of Parent/Caregivers and Children with Asthma

| Characteristic | Control Group N= 91 | Intervention Group N=130 | Total N= 221 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Sociodemographic Characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Child age | |||

| (mean, SD) | 8.08 (1.48) | 8.02 (1.87) | 8.05(1.72) |

|

| |||

| Child Gender | |||

| Male | 51(56.0) | 86 (66.2) | 137 (62.0) |

| Female | 40 (44.0) | 44 (33.8) | 84 (38.0) |

|

| |||

| Child Race | |||

| White | 47(51.6) | 76 (58.5) | 123(55.7) |

| African Am. | 34(37.4) | 45 (34.6) | 79(35.7) |

| Hispanic | 2 (2.2) | 4 (3.1) | 6(2.7) |

| Other | 8 (8.8) | 5 (3.8) | 13(5.9) |

|

| |||

| Asthma Severity | |||

| Mild intermittent | 39(42.9) | 47(36.2) | 86(38.9) |

| Mild Persistent | 34(37.4) | 51(39.2) | 85(38.5) |

| Moderate Persistent | 8 (8.8) | 18(13.8) | 26(11.7) |

| Severe Persistent | 10(10.9) | 14(10.8) | 24 (10.9) |

|

| |||

| Parent/Caregiver Sociodemographic Characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Respondent | |||

| Mother | 83(91.2) | 115(88.5) | 198(89.6) |

| Father | 2 (2.2) | 8 (6.2) | 10 (4.5) |

| Stepmother | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (0.9) |

| Grandmother | 4 (4.4) | 2 (1.5) | 6 (2.7) |

| Legal guardian | 1 (1.1) | 4 (3.1) | 5 (2.3) |

|

| |||

| Parent age | |||

| (mean, SD) | 35.9 (7.4) | 36.4 (8.4) | 36.2(8.0) |

|

| |||

| Parent Education | |||

| <HS | 10(11.0) | 12(9.3) | 22(10.0) |

| HS graduate | 36(39.6) | 42(32.3) | 78(35.4) |

| Some college | 33(36.2) | 49(38.1) | 82(37.3) |

| College Grad. + | 12 (13.2) | 26(20.3) | 38(17.3) |

|

| |||

| Parent Income | |||

|

| |||

| <$10,000 | 4(4.4) | 13(10.0) | 17(7.8) |

| $10-29,999 | 32(35.2) | 34(26.2) | 66(29.8) |

| $30-39,999 | 14(15.4) | 18(13.8) | 32(14.5) |

| $40,000+ | 37(40.6) | 62(47.7) | 99(44.7) |

| Refused | 4(4.4) | 3(2.3) | 7(3.2) |

Portion of table presented in article by A.Butz et al. (2005)

Caregiver QOL by Work and School Days Missed and Child Hospitalizations

All of the parents/caregivers' quality of life mean scores (TQOL, AQOL and EQOL) were highly correlated with the parents reports of the number of missed days of work (p <.001). At follow-up, parents reporting missing fewer days of work had a statistically significant higher TQOL scores (p=0.03). In addition, the parent/caregivers mean AQOL scores were associated with missed days of work (p = 0.02). For all children regardless of intervention status, school days missed was significantly associated with their EQOL scores (p=.03). There was also a trend toward an association between hospitalizations due to asthma and the child's EQOL subscale (p=.08).

Asthma Severity and Caregiver & Child QOL

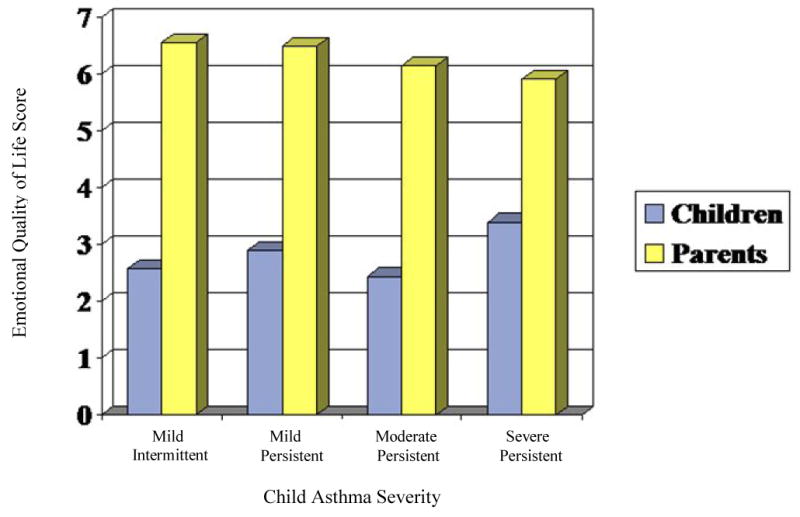

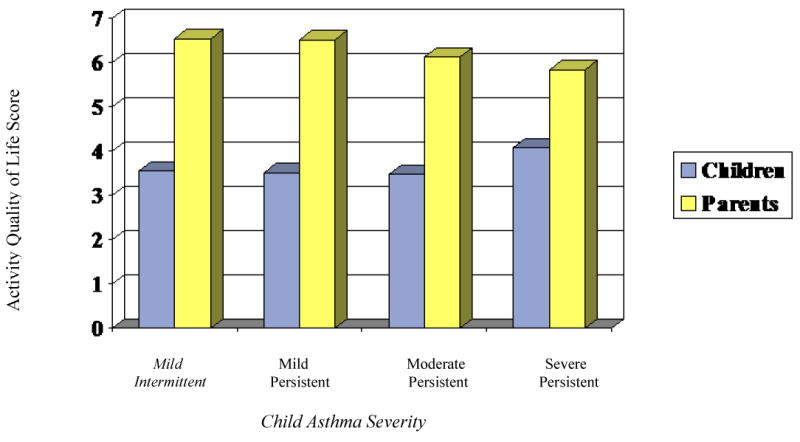

Most children were categorized as mild intermittent (38.9%), or mild persistent (38.5%) asthma followed by moderate persistent (11.7%) and severe persistent asthma (10.9%) (see table) At baseline, there was no statistically significant difference between the child's asthma severity and parent or child quality of life scores. At follow up, a statistically significant relationship was found between the child's asthma severity level and the parents/caregivers EQOL subscale (p=0.009) (Figure 1) and the parent/caregiver AQOL subscale (p= 0.03) (Figure 2). There was a trend toward a statistically significant relationship between asthma severity and the child's EQOL subscale (p= 0.08), but no significant relationship between asthma severity and the child's AQOL subscale (p=0.51).

Figure 1.

Asthma Severity & Emotional QOL Scores in Parents & Children at follow-up*

*p= 0.009, this p value is significant for all severity levels

Figure 2.

Asthma Severity & Activity QOL scores in Parents & Children at Follow-up*

p=0.03, this p value is significant for all severity levels

Asthma Educational Program

The asthma education intervention was not associated with the total or subscale QOL scores in the parents/caregivers at baseline or follow-up. However, analyses of quality of life scores in the children indicated that the child EQOL subscale scores were higher for children in the control group at follow-up (p=0.002).

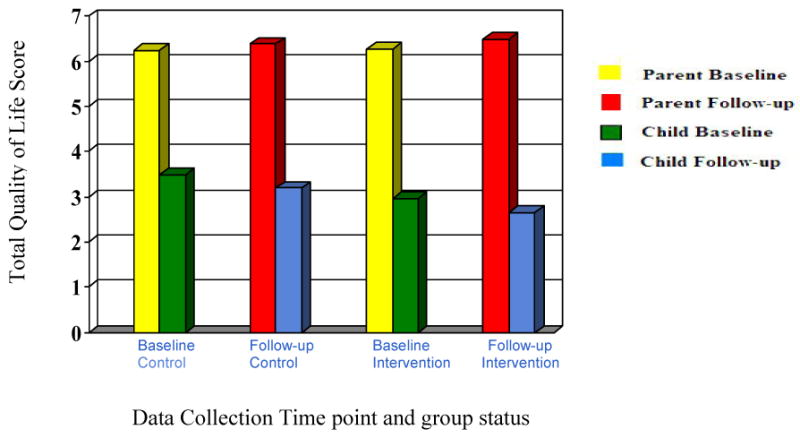

Comparison of Quality of Life Scores between Parent/Caregivers & Children

Mean TQOL scores for parent/caregivers were higher at baseline and follow-up as compared to child TQOL scores (Figure 3). Parents also reported higher emotional and activity quality of life subscale scores than children at both baseline and follow-up. In contrast to the scores of the parents/caregivers, children's TQOL scores decreased from baseline to follow-up in both groups, however there was no statistically significant difference in TQOL scores between time periods. There were no statistically significant correlations between any of the parents/caregivers quality of life scores and quality of life scores for the children.

Figure 3. Comparison of Total QOL in Parents/Caregivers and &Children.

Discussion

This study of rural children with asthma and their parents/caregivers revealed several key differences in quality of life perceptions. For these rural parents/caregivers, quality of life measurements were very positive and their child's asthma symptoms or level of severity was the most influential factor in their overall quality of life perception as well as in their activity and emotional domain quality of life measurements. Parental total quality of life and activity quality of life were also associated with the number of workdays missed by the parents at follow-up. An optimal quality of life for rural individuals may be defined as the ability to perform normal daily functions in the presence or absence of symptoms. Rural parents are self-managers of their child's asthma due to access to care issues such as long distances required to seek medical care. Most families had to drive one hour or more to the nearest hospital or asthma specialist. This most likely translates into increased time missed from work and school. Therefore, when a child's asthma becomes so severe that the parent starts to miss work, the parent's perception of quality of life diminishes.

These results indicate the need for children with asthma and their parents/caregivers to gain and maintain optimal control of the child's asthma. To do so, health care practitioners must equip rural parents and children with the necessary skills and health education materials for effective self-management of asthma. In particular, health care providers should demonstrate and monitor proper asthma device technique and medicine usage, peak flow meter use, and ask the child to perform a return demonstration at each asthma care visit.

In contrast to the strong influence that the child's asthma severity had on parental quality of life, it was very interesting that parent/caregivers quality of life perceptions were not influenced by the asthma education program. This finding contrasts with the results of several studies that have indicated a positive relationship between asthma education and quality of life (Gallefoss,Bakke & Rsgaard, 1999; Olajos-Clow,Costello & Loughheed, 2005; Tatis, Remache & Dimango 2005). However, disease severity may be a moderating factor in the amount of benefit derived from educational interventions aimed at behavior modification (Olajos-Clow et al.). Perhaps the children's asthma severity level confounded the full benefits of our educational intervention due to children with more severe disease requiring a more intensive education intervention.

For rural children in this study, quality of life perceptions were unrelated to those of their parents. The fact that control children had a higher emotional quality of life at follow up is puzzling. However, this may be due to their participating in the study (the Hawthorne effect). For all children, the number of school days missed was significantly associated with the child's emotional quality of life. This was an indirect relationship where increased missed days of school was associated with a decrease in EQOL. This suggests that school attendance is a significant component of the rural child's life and that school may be the critical socialization site for rural children. Moreover, this need for socialization may indicate that school is the ideal location to deliver asthma education to rural children.

Although there was a trend for asthma symptoms and the number of hospitalizations to be associated with the child's emotional quality of life, these findings did not reach statistical significance. These results support previous research investigating the impact of asthma on the emotional health of children and adolescents. Okelo et al. (2004) noted that poor asthma specific emotional quality of life was significantly associated with increased missed school days (p < .05) and a non-significant trend was seen for hospitalizations. Blackman and Gurka (2007) noted that children with asthma not only miss more days of school than their counterparts without asthma, but children with asthma also have higher rates of depression and other behavioral disorders. When a child misses school or is in the hospital due to asthma, he or she may began to feel “different” from other children or classmates who are able to go to school or who are not consistently in the hospital due to asthma.

Parents overall had more positively skewed QOL scores than the children. This could possibly be attributed to social desirability on the part of the parent. Parents may not want to associate their child's health condition to their personal quality of life. It may also be that parents really feel that they have a positive quality of life despite having a child with asthma. Another possible explanation for the difference in parent and child QOL scores may be discrepancies in recall periods for traumatic events. Chen, Zeltzer, Craske and Katz (2000) found that distressed children might show bias toward negative aspects of an event by excluding positive or neutral aspects. For example, a child experiencing one asthma attack in the last week may be more likely to say he or she was extremely bothered by asthma symptoms while forgetting that they may have had some less severe symptom days after treatments with a steroid. The trauma of the initial event may diminish any positive aspects that follow. As a plausible secondary explanation, children with asthma may not share their parents views about their illness (Gersharz, Eiser & Woodhouse, 2003). Children living with asthma are experiencing their symptoms first hand versus parents or practitioners who only witness or hear about the symptoms. Children are the experts on their own feelings, activity limitations and symptoms. School age children, in particular, do not necessarily share each asthma event with their parents. They may omit reporting coughing in gym or at recess simply because they forget or possibly, because they do not want to be excluded from these events.

Differences in child and parental quality of life indicate the importance of communicating with the child and ascertaining the child's quality of life perceptions at each health encounter. Rural elementary school age children in this study had a much lower perception of quality of life than their parents. This discrepancy in quality of life has significant clinical implications in that it illustrates the fact that health care providers who speak only to the parent/caregiver during an asthma health care visit may miss a large amount of data that can help them to understand the child's health status. Clinicians cannot rely on parental report alone to provide insight into the child's quality of life (Callery et al., 2003). Previous research has shown that for children under age 11, parent report alone did not predict a child's quality of life and only moderately correlated with child airway caliber and control (Callery et al.). Nurse practitioners and physicians could benefit from a brief, easy to administer child quality of life questionnaire that could be completed verbally during a regular clinic visit (Eiser & Morse, 2001).

Limitations

This study was unique in that it presented the impact of asthma on rural families from the viewpoint of both parent and child. Yet, there were some study limitations. The study findings may not be generalizable beyond this rural sample. Parents and children in this study may have suffered from some recall bias because there was a 10 month time period between baseline and follow-up with limited research activities other than newsletters post the interactive, educational intervention.

Conclusion

When ascertaining the quality of life of rural parents/caregivers and children with asthma, several factors need to be considered 1) parent and child perceptions may differ therefore both the parent/caregiver and the child should be questioned concerning their individual perceptions of quality of life as it relates to asthma; 2) rural individuals may attempt to maintain normalcy even in the presence or absence of asthma symptoms even though asthma severity ultimately may affect their way of life; 3) gaining control of the child's asthma severity is an essential component of improving parental quality of life and helping asthma education interventions to be more effective. Although this study showed negative effects of an asthma education intervention on the overall quality of life of rural families with asthma, it is still imperative that tailored educational interventions be provided for this population. In closing, asthma education programs for rural families affected by asthma should focus on helping the family gain and maintain control of their child's asthma in order for the child and parent/caregiver to enjoy optimal quality of life.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Blackman JA, Gurka MJ. Developmental and behavioral comorbidities of asthma in children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:92–99. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000267557.80834.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butz A, Pham L, Lewis L, Lewis C, Hill K, Walker J, et al. Rural children with asthma: impact of a parent and child asthma education Program. Journal of Asthma. 2005;42:813–821. doi: 10.1080/02770900500369850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callery P, Milnes L, Verduyn C, Couriel J. Qualitative study of young people's and parents' beliefs about childhood asthma. British Journal of General Practice. 2003;53:185–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Zeltzer LK, Craske MG, Katz ER. Children's memories for painful cancer treatment procedures: Implications for distress. Child Development. 2000;71:931–945. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner C, Morse R. A review of measures of quality of life for children with chronic illness. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2001;84:205–211. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallefoss F, Bakke PS, Rsgaard PK. Quality of life assessment after patient education in a randomized controlled study on asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999;159:812–817. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9804047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerharz EW, Eiser C, Woodhouse CRJ. Current approaches to assessing the Quality of life in children and adolescents. BJU International. 2003;91:150–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook C, McPherson AC, Macdonald IA, Swift JA, Ramsay C, Newbould R, et al. Asthma as a barrier to children's physical activity: implications for body mass index and mental health. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2443–2449. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Kreuter MW, Deeds SG, Partridge KB. Health education planning: A diagnostic approach. California: Mayfield Publishing Company; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Halterman JS, Yoos HL, Conn KM, Callahan PM, Montes G, Neely TL, et al. The impact of childhood asthma on parental quality of life. Journal of Asthma. 2004;41:645–653. doi: 10.1081/jas-200026410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handelman L, Rich M, Bridgemohan CF, Scheider L. Understanding pediatric inner-city asthma: An explanatory model approach. Journal of Asthma. 2004;41:167–77. doi: 10.1081/jas-120026074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner SD, Fouladi RT. Home Asthma management for rural families. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2003;8:52–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2003.tb00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner SD. Home visiting for intervention delivery to improve rural family asthma management. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2006;23:213–223. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2304_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in children with asthma. Quality of life research. 1996a;5:35–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00435967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in the parents of children with asthma. Quality of Life Research. 1996b;5:27–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00435966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juniper EF. How important is quality of life in pediatric asthma? Pediatric Pulmonology Supplement. 1997;15:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moonie SA, Sterling DA, Figgs L, Castro M. Asthma status and severity affect missed school days. Journal of School Health. 2006;76:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. National Institutes of Health Publication No 97-4051. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health Publication; 1997. Expert Panel Report 2: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. [Google Scholar]

- Naumann PL, Huss K, Calabrese B, Smith T, Quartey R, Van de Castle B, et al. A+ Asthma rural partnership coloring for health: An innovative rural asthma teaching strategy. Pediatric Nursing. 2004;30:490–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okelo S, Wu A, Krishnan JA, Rand C, Skinner EA, Diette G. Emotional quality of life and outcomes in adolescents with asthma. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004 October;:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olajos-Clow J, Costello E, Lougheed MD. Perceived control and quality of life in asthma: impact of asthma education. Journal of Asthma. 2005;42:751–756. doi: 10.1080/02770900500308080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman LM, Baxter-Jones ADG, Helms PJ. Parents' quality of life and respiratory symptoms in young children with mild wheeze. European Respiratory Journal. 2001;17:254–258. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17202540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2004. Computer software. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer MG, Reynolds KE, Couper JJ, French DJ, Kennedy D, Martin J, et al. A two-year perspective study of the health-related quality of life of children with chronic illness—the parents' perspective. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14:395–405. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0786-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatis V, Remache D, DiMango E. Results of a culturally directed asthma intervention program in an inner-city Latino community. Chest. 2005;128:1163–1167. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert C, Burman M. Rural health and health-seeking behaviors. Annual Review of Nursing Research. 1994;12:65–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelstein ML, Quartey R, Pham L, Lewis-Boyer L, Lewis C, Hill K, et al. Asthma education for rural school nurses: Resources, barriers, and outcomes. The Journal of School Nursing. 2006;22:170–177. doi: 10.1177/10598405060220030801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawn BP, Mainous AG, Love MM, Hueston W. Do rural and urban children have comparable asthma care utilization? Journal of Rural Health. 2001;17:32–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2001.tb00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]