Abstract

We investigated the efficacy of tachyplesin III and clarithromycin in two experimental rat models of severe gram-negative bacterial infections. Adult male Wistar rats were given either (i) an intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg/kg Escherichia coli 0111:B4 lipopolysaccharide or (ii) 2 × 1010 CFU of E. coli ATCC 25922. For each model, the animals received isotonic sodium chloride solution, 1 mg/kg tachyplesin III, 50 mg/kg clarithromycin, or 1 mg/kg tachyplesin III combined with 50 mg/kg clarithromycin intraperitoneally. Lethality, bacterial growth in the blood and peritoneum, and the concentrations of endotoxin and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in plasma were evaluated. All the compounds reduced the lethality of the infections compared to that for the controls. Tachyplesin III exerted a strong antimicrobial activity and achieved a significant reduction of endotoxin and TNF-α concentrations in plasma compared to those of the control and clarithromycin-treated groups. Clarithromycin exhibited no antimicrobial activity but had a good impact on endotoxin and TNF-α plasma concentrations. A combination of tachyplesin III and clarithromycin resulted in significant reductions in bacterial counts and proved to be the most-effective treatment in reducing all variables measured.

Gram-negative bacteria have often been implicated in the pathogenesis of severe infections, sepsis, and sepsis-related organ injury, which are important causes of death in critically ill patients (1, 7, 22). An outer membrane provides these organisms with an effective protective barrier to antibiotics that might otherwise be active against them. Several studies have shown that this protective barrier, formed by a divalent cation-cross-linked matrix of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) molecules on the outer leaflet of the outer membrane, can be breached via displacement of LPS-bound metals by antimicrobial peptides of diverse structural classes (28, 29). Antimicrobial peptides are multifunctional as effectors of innate immunity on skin and mucosal surfaces and have demonstrated direct antimicrobial activity against various bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. Particularly, antimicrobial peptides have been shown to have immunomodulatory functions, including endotoxin binding and -neutralizing abilities, chemotactic activities, the induction of cytokines and chemokines, promotion of wound healing, and angiogenesis (5, 10, 13-15, 27). Tachyplesins are a group of antimicrobial peptides isolated from horseshoe crabs. Tachyplesin III (KWCFRVCYRGICYRKCR-NH2), isolated from the Southeast Asian horseshoe crabs Tachypleus gigas and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda, consists of 17 amino acids with two disulfide bridges and is a representative antimicrobial peptide with a cyclic β-sheet (16, 23). It exhibits a broad spectrum of activities against gram-negative and -positive bacteria, fungi, and even enveloped viruses at low concentrations (16, 23). “New” macrolides such as clarithromycin were not clinically introduced for the treatment of patients with various infectious diseases until 40 years ago (3). Clarithromycin has been shown to have strong anti-inflammatory properties in recent experimental studies of gram-negative bacterial sepsis (11, 12).

Active but not penetrating antibiotics such as clarithromycin and other new macrolides may be appropriate for clinical use when combined with membrane-active compounds able to increase the permeability of the outer membrane and thus render gram-negative bacteria susceptible to several hydrophobic antibiotics. The present experimental study aimed to investigate the in vitro interaction and in vivo efficacy of a membrane-active compound, tachyplesin III, and a hydrophobic antibiotic, clarithromycin, in two rat models of Escherichia coli infections, the first (intraperitoneal administration of LPS) to evaluate the antiendotoxin activity and the immunomodulatory effect of the compounds and the latter (E. coli-induced peritonitis) to evaluate their antimicrobial activities and their impact on survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs.

Tachyplesin III (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot accession number P18252; molecular weight, 2235.76) was synthesized by 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl solid-phase chemistry (4, 9). The protected peptidyl resin was treated with 92% trifluoroacetic acid, 2% phenol, 2% ethanedithiol, 2% water, and 2% triisopropylsilane for 2 h. After the peptide was cleaved, the solid support was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The cleaved peptide was precipitated with diethyl ether, dissolved in 20% acetic acid, and oxidized by 0.1 M iodine in methanol. Tachyplesin III was purified and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography. The resulting fractions with purity greater than 94 to 95% were tested by high-performance liquid chromatography. The peptide was analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry and then solubilized in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2), yielding 1 mg/ml stock solution. Solutions of the drug were made fresh on the day of assay or stored at −80°C in the dark for short periods. Clarithromycin, obtained from Abbott S.p.A., Campoverde LT, Italy, was dissolved in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. Solutions of the drug were made fresh on the day of assay.

Organisms and reagents.

The commercially available quality control strain of E. coli ATCC 25922 was used. For in vitro studies, we used five clinical isolates of E. coli cultured from samples from infected patients hospitalized at the Ospedali Riuniti of Ancona, Italy. Endotoxins (E. coli serotype 0111:B4; Sigma-Aldrich S.r.l., Milan, Italy) were prepared in sterile saline, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C for short periods.

In vitro studies.

Laboratory-standard powders were diluted in accordance with the manufacturers’ recommendations. MICs were determined according to the procedures outlined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI; formerly NCCLS) (24). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

For synergy studies, the ATCC control strain and the five clinical strains of E. coli were tested by a checkerboard titration method. The fractionary inhibitory concentration indexes were interpreted as follows: <0.5, synergistic; 0.5 to 4.0, indifferent; and >4.0, antagonistic (8). In addition, time-kill synergy studies were performed at recommended subinhibitory concentrations (one-fourth and one-half the MICs). Synergy or antagonism was defined as a 100-fold increase or decrease, respectively, and indifference was defined as a <10-fold increase or decrease in the colony count at 24 h for the drug combination compared to that for the most-active single agent, and the number of surviving organisms in the presence of the drug combination had to be 100 CFU/ml below that for the starting inoculum.

Finally, the ability of tachyplesin III to permeabilize the membranes of the gram-negative bacteria was determined as described by Ofek et al. (25). Briefly, a bacterial suspension (10 μl; 1 × 105 CFU) was inoculated into microtiter plate wells containing 100 μl of a serial twofold dilution (1,000 to 0.5 μg/ml) of clarithromycin in Iso-Sensitest broth (Oxoid S.p.A., Milan, Italy). Ten microliters of a 600 mg/liter-solution of test peptide was added to each well to achieve a final test peptide concentration per well of 50 μg/ml. The extent to which the MIC of clarithromycin decreased in the wells in the presence or absence of the test peptides was calculated and was designated the peptide's permeabilizing activity.

Animals.

A total of 120 adult male (age range, 3 to 5 months) Wistar rats weighing 300 to 400 g were used. All animals were housed in individual cages under conditions of constant temperature (22°C) and humidity with a 12-h light/dark cycle and had access to chow and water ad libitum throughout the study. The study was approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the I.N.R.C.A.-I.R.R.C.S.

Experimental design.

Two experimental conditions were studied: (i) intraperitoneal administration of LPS and (ii) E. coli-induced peritonitis. For the first experimental condition, four groups, each containing 15 animals, were anesthetized by an intramuscular injection of ketamine and xylazine (30 mg/kg and 8 mg/kg of body weight, respectively) and injected intraperitoneally with 1.0 mg E. coli serotype 0111:B4 LPS in a total volume of 500 μl sterile saline. Immediately after being injected, each group of animals received intraperitoneally either an isotonic sodium chloride solution (control group C0), 1 mg/kg tachyplesin III, 50 mg/kg clarithromycin, or 1 mg/kg tachyplesin III combined with 50 mg/kg clarithromycin.

For the second experimental condition, E. coli ATCC 25922 was grown in brain heart infusion broth. When the bacteria were in the log phase of growth, the suspension was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the bacteria were resuspended and diluted into sterile saline. All animals (four groups, each containing 15 animals) were anesthetized as mentioned above. The abdomen of each animal was shaved and prepared with iodine. The rats received an intraperitoneal inoculum of 1 ml of saline containing 1 × 109 CFU of E. coli ATCC 25922. Immediately after the bacterial challenge, each group of animals received intraperitoneally either isotonic sodium chloride solution (control group C1), 1 mg/kg tachyplesin III, 50 mg/kg clarithromycin, or 1 mg/kg tachyplesin III combined with 50 mg/kg clarithromycin.

Toxicity was evaluated on the basis of any drug-related adverse effects, i.e., local signs of inflammation, anorexia, weight loss, diarrhea, fever, or behavioral alterations. To evaluate the physiological effects of tachyplesin III, temperature, pulse, blood pressure, respiration, and oxygenation were monitored in a supplementary peptide-treated group without infection.

Evaluation of treatment.

At the end of the study, the rates of blood culture positivity, quantities of bacteria in the intra-abdominal fluid, rates of lethality, and plasma endotoxin and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) levels were evaluated for both experimental models. The animals were monitored for the subsequent 72 h.

In both models, the presence of systemic symptoms was defined in analogy to the criteria applied for humans. Each animal was considered to be endotoxic or septic if at least two of the following criteria were satisfied: (i) having an increased pulse rate; (ii) having a rectal temperature above 38°C or below 36°C; (iii) having an increased breathing rate; and (iv) having more than 12,000 or less than 4,000 white blood cells per microliter (21). The surviving animals were killed with 4% isofluorane, and blood samples for culture were obtained by aseptic percutaneous transthoracic cardiac puncture. In addition, to perform quantitative evaluations of the bacteria in the intra-abdominal fluid, 10 ml of sterile saline was injected intraperitoneally, samples of the peritoneal lavage fluid were serially diluted, and a 0.1-ml volume of each dilution was spread onto blood agar plates. The limit of detection was ≤2 log10 CFU/ml. The plates were incubated both in air and under anaerobic conditions at 35°C for 48 h. The bacterial isolates were identified by biochemical assay.

For blood cultures (model ii) and the determination of endotoxin and TNF-α levels in plasma (all models), 0.1-ml blood samples were collected from a tail vein of each rat into a sterile syringe 0, 2, 6, 12, and 36 h after the injection of LPS or bacteria and were transferred to tubes containing EDTA tripotassium salt.

Biochemical assays.

Endotoxin concentrations were measured by the commercially available Limulus amebocyte lysate test (E-TOXATE; Sigma-Aldrich). Plasma samples were serially twofold diluted with sterile endotoxin-free water and were heat-treated for 5 min in a water bath at 75°C to destroy inhibitors that can interfere with activation. The endotoxin content was determined as described by the manufacturer. Endotoxin standards (0, 0.015, 0.03, 0.06, 0.125, 0.25, and 0.5 endotoxin units/ml) were tested in each run, and the concentrations of endotoxin in the text samples were calculated by comparison with the standard curve. TNF-α levels were measured using a solid-phase sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The intensity of the color was measured in an MR 700 microplate reader (Dynatech Laboratories, United Kingdom) by reading the absorbance at 450 nm. The results for the samples were compared with the standard curve to determine the amount of TNF-α present. All samples were run in duplicate. The lower limit of sensitivity for TNF-α by this assay was 0.05 ng/ml.

Statistical analysis.

Mortality rates were compared between groups by using the Fisher exact test. Qualitative results for blood cultures were analyzed by the χ2 test (eventually corrected according to the Yates method) or the Fisher exact test, depending on the sample size. Quantitative evaluations of the bacteria in the intra-abdominal fluid cultures were presented as means ± standard deviations; statistical comparisons between groups were made by analysis of variance. Post hoc comparisons were performed by Bonferroni's test. Mean values for plasma endotoxin and TNF-α levels were compared between groups by nonparametric analysis of variance (Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by the standard procedure for multiple comparisons), due to the presence of censored data. Each comparison group contained 15 animals. The significance level was fixed at 0.05.

RESULTS

In vitro studies.

The ATCC control strain was inhibited by tachyplesin III at a concentration of 4 mg/liter, while clarithromycin exhibited a MIC of 128 mg/liter, suggesting that it was not active against E. coli. In the synergy study, when the peptide was combined with the macrolide, we observed a fractionary inhibitory concentration index of 0.385. Time-kill synergy studies showed no effect when the compounds were tested at one-fourth the MIC. On the other hand, synergism was clearly observed at one-half the MIC. The colony count for the drug combination-treated samples determined at 24 h showed a decrease of 3 log (6.71 ± 1.15 ×103) compared to that for tachyplesin III, the most-active single agent, which produced a 24-h colony count of 5.65 ± 1.31 ×106.

Finally, the sensitivity of all the strains to clarithromycin increased up to fourfold in the presence of tachyplesin III (MIC range, 16 to 32 mg/liter for the ATCC control strain; 8 to 32 mg/liter for the five clinical isolates). In a separate set of experiments, we determined the minimum concentration of the test peptide needed to render E. coli sensitive to 30 μg/ml of clarithromycin. We found that a concentration of at least 2.0 mg/liter of tachyplesin III was required to render the bacteria sensitive to clarithromycin.

In vivo studies. Model i: intraperitoneal administration of LPS.

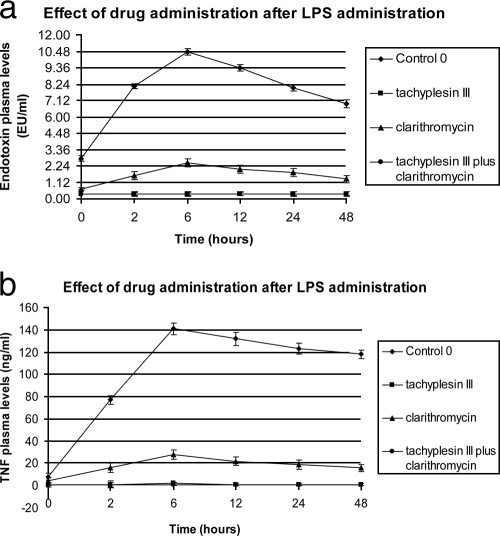

The levels of endotoxin and TNF-α in plasma peaked 6 h after intraperitoneal administration of 1.0 mg/kg E. coli serotype 0111:B4 LPS. Intravenous treatments with tachyplesin III with or without clarithromycin resulted in marked decreases (P < 0.05) in TNF-α levels and virtually undetectable levels of endotoxin in the plasma, compared with those of the control (C0) and macrolide-treated groups. Interestingly, significant differences in the plasma levels of both LPS and TNF-α were also observed between clarithromycin-treated and untreated groups (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Endotoxin and TNF-α plasma levels after intraperitoneal administration of 1.0 mg E. coli serotype 0111:B4 LPS. EU, endotoxin unit(s).

Model ii: intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 109 CFU of E. coli ATCC 25922.

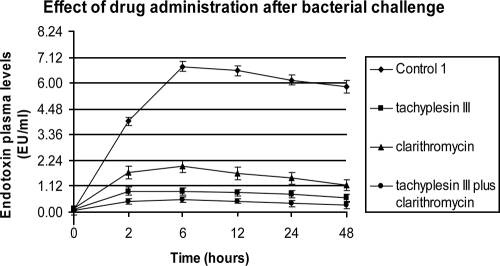

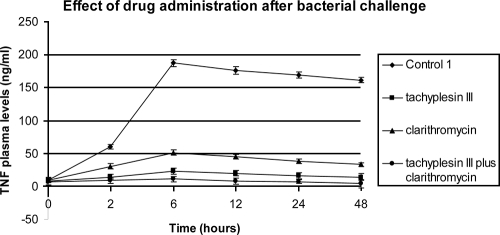

All animals were monitored for 72 h. The rate of lethality in control group C1 was 100% within 48 h. All antibiotic treatments led to decreased mortality (P < 0.05). Lethality rates of 33.3 and 66.6% were observed for the group treated with tachyplesin III and clarithromycin, while a rate of 6.6% was observed in the combined-drug treatment group (Table 1). In the same groups, bacteriological evaluation of C1 showed 100% positive blood cultures, and 7.3 × 108 ± 2.0 × 108 CFU/ml of bacteria were counted in the intra-abdominal fluid. Tachyplesin III showed a higher antimicrobial activity than the macrolide. When it was combined with clarithromycin, the positive interaction produced the lowest bacterial counts (1.4 × 101 ± 0.2 × 101 CFU/ml), statistically significant (P < 0.05) versus those of all other groups. The administration of tachyplesin III alone or combined produced a strong reduction in plasma endotoxin and TNF-α levels compared to those of the control and clarithromycin-treated groups. However, clarithromycin showed good anti-inflammatory activity, with significant differences observed between this treated group and the control group. The results are summarized in Fig. 2 and 3.

TABLE 1.

Efficacy of administration of intravenous tachyplesin III and clarithromycin in a rat model after intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 109 CFU of E. coli ATCC 25922

| Treatmenta | Lethality as indicated byb

|

Qualitative blood culture (no. positive/total no.) | Bacterial count in peritoneal fluid (log CFU/ml)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. dead/total no. | % Dead | |||

| No treatment (control group) | 15/15 | 100 | 15/15 | 8.86 ± 8.30 |

| T-III (mg/kg) | 5/15d,e | 33.3 | 5/15d,e | 4.46 ± 3.84d,e |

| CLR (50 mg/kg) | 10/15d | 66.6 | 11/15d | 6.68 ± 6.04 |

| T-III (1 mg/kg) plus CLR (50 mg/kg) | 1/15d,e | 6.6 | 2/15d,e | 1.14 ± 0.30d,e |

T-III, tachyplesin III; CLR, clarithromycin.

Lethality was monitored for 72 h following the challenge.

Mean ± standard deviation.

P < 0.05 versus result for the control group C2.

P < 0.05 versus result for clarithromycin-treated group.

FIG. 2.

Effects on endotoxin plasma levels of 1 mg/kg tachyplesin III, 50 mg/kg clarithromycin, and 1 mg/kg tachyplesin III plus 50 mg/kg clarithromycin administered intravenously after intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 109 CFU of E. coli ATCC 25922. EU, endotoxin unit(s).

FIG. 3.

Effects on TNF-α plasma levels of 1 mg/kg tachyplesin III, 50 mg/kg clarithromycin, and 1 mg/kg tachyplesin III plus 50 mg/kg clarithromycin administered intravenously at 0 and 360 min after intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 109 CFU of E. coli ATCC 25922.

Finally, none of the tachyplesin III-treated animals had clinical evidence of drug-related adverse effects, and no changes in physiological parameters were observed in the group without infection that was treated with a supplement of 1 mg/kg peptide.

DISCUSSION

The development of agents that can permeabilize the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria may provide a useful new approach to terminating the infectious process by enhancing the activities of antibiotics that might otherwise be inactive. These membranes act as an effective permeability barrier against external noxious agents, and LPS is the key molecule for this function (28, 29, 31). In the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, the LPS molecules occupy the outer leaflet of the membrane and leave no space for glycerophospholipids, which thus occupy the inner leaflet (32). Antimicrobial peptides are thought to play an important role in the killing and clearance of gram-negative bacteria and the neutralization of endotoxins. Their cell target is the membrane and includes the structure, length, and complexity of the hydrophilic polysaccharide found in the outer layer (14). These parameters affect the ability of each peptide to diffuse through the cell's outer barrier and to reach its cytoplasmic membrane. In order to exert their activity, antimicrobial peptides first interact with and traverse an outer barrier, mainly LPSs and peptidoglycans in bacteria and a glycocalyx layer and matrix proteins in mammalian cells (26, 30, 33). Only then can the peptides bind and insert into the cytoplasmic membrane. Recent studies have shown that patterns of peptide-induced permeabilization of the outer and inner E. coli membranes correlated well with antimicrobial activity, confirming that membrane permeabilization has a harmful effect upon the bacteria (18).

In the present study, we evaluated the efficacy of the combination between tachyplesin III and clarithromycin against two animal models of E. coli infection. In our models, the administration of peptide showed a good impact on lethality rates and plasma endotoxin and TNF-α levels. Its ability to inhibit the release of endotoxins and cytokines can explain the interesting finding concerning the low TNF levels in the endotoxin group as well as in the bacteria-inoculated group. Clarithromycin exhibited a good anti-inflammatory activity, while its impact on lethality rates and bacteremia was significantly lower than that of tachyplesin III. It is important to note that the antibacterial activity of tachyplesin III was significantly increased when it was combined with clarithromycin, and this combination produced statistically significant reductions in all outcome measures considered.

In time-killing curves and with the checkerboard titration method, a strong synergistic effect was observed. This synergistic pattern was also clearly observed in the in vivo setting. In fact, a combination of tachyplesin III and clarithromycin resulted in a significant decrease in the bacterial count, positive blood cultures, and lethality rates compared to those for peptide monotherapy. This combination was also most effective in decreasing the levels of LPS and TNF-α, confirming the good immunomodulatory activity of tachyplesin III and clarithromycin.

Previous studies have reported the positive interaction among antimicrobial peptides and hydrophobic antibiotics (6, 33). Nevertheless, the mechanism is not known, with few exceptions. It is generally thought that antimicrobial peptides exert their inhibitory effects by increasing bacterial membrane permeability, causing leakage of bacterial contents. Agents that increase membrane permeability by decreasing the effectiveness of outer membrane porin channels could greatly sensitize otherwise impermeable gram-negative organisms to hydrophobic solutes, facilitate their penetration, and enhance their activity (2, 20, 33). Tachyplesins are also considered to exert their bactericidal activity by permeabilizing bacterial membranes, although the molecular mechanism has not yet been determined (17, 19). Several studies have shown that they form an anion-selective pore in the planar lipid bilayer and trigger the leakage of calcein from liposomes, the latter being coupled to the translocation of the peptide across lipid bilayers. Tachyplesins also form a toroidal pore composed of peptides and lipids (17, 19). These mechanisms of the barrier-disturbing effect of tachyplesin III upon the outer membrane could thereby provide clarithromycin accessibility to its intracytoplasmatic target. It has been shown that macrolides use the hydrophobic pathway across the outer membrane and that an intact outer membrane is an effective barrier against them.

The antimicrobial and antiendotoxin activities of tachyplesin III and its synergistic interactions demonstrated upon clarithromycin highlight the potential usefulness of this combination in severe E. coli infections. More studies are needed to determine the safety and efficacy of this antibiotic combination against severe gram-negative bacterial infections.

Acknowledgments

We express our thanks to Silvana Esposito for her technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberti, C., C. Brun-Buisson, H. Burchardi, C. Martin, S. Goodman, A. Artigas, A. Sicignano, M. Palazzo, R. Moreno, R. Boulmé, E. Lepage, and R. Le Gall. 2002. Epidemiology of sepsis and infection in ICU patients from an international multicenter cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 28:108-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balakrishna, R., S. J. Wood, T. B. Nguyen, K. A. Miller, E.V. Suresh Kumar, A. Datta, and S. A. David. 2006. Structural correlates of antibacterial and membrane-permeabilizing activities in acylpolyamines. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:852-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blondeau, J. M., E. Decarolis, K. L. Metzler, and G. T. Hansen. 2002. The macrolides. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 11:189-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen, T. 1979. Qualitative test for monitoring coupling completeness in solid phase peptide synthesis using chloranil. Acta Chem. Scand. Series B 33:763-766. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cirioni, O., A. Giacometti, R. Ghiselli, C. Bergnach, F. Orlando, C. Silvestri, F. Mocchegiani, A. Licci, B. Skerlavaj, V. Saba, M. Rocchi, M. Zanetti, and G. Scalise. 2006. LL-37 protects rats against lethal sepsis caused by gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1672-1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cirioni, O., A. Giacometti, R. Ghiselli, W. Kamysz, F. Orlando, F. Mocchegiani, C. Silvestri, A. Licci, L. Chiodi, J. Łukasiak, G. Scalise, and V. Saba. 2006. Citropin 1.1-treated central venous catheters improve the efficacy of hydrophobic antibiotics in the treatment of experimental staphylococcal catheter-related infection. Peptides 27:1210-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diekema, D. J., M. A. Pfaller, R. N. Jones, G. V. Doern, P. L. Winokur, A. C. Gales, H. S. Sader, K. Kugler, and M. Beach. 1999. Survey of bloodstream infections due to gram-negative bacilli: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, and Latin America for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:595-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliopoulos, G. M., and R. C. Moellering, Jr. 1996. Antimicrobial combinations, p. 330-393. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD.

- 9.Fields, G. B., and R. L. Noble. 1990. Solid phase peptide synthesis utilizing 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl amino acids. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 35:161-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giacometti, A., O. Cirioni, R. Ghiselli, F. Mocchegiani, C. Silvestri, F. Orlando, W. Kamysz, J. Łukasiak, V. Saba, and G. Scalise. 2006. Amphibian peptides prevent endotoxemia and bacterial translocation in bile duct-ligated rats. Crit. Care Med. 34:2415-2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E. J. 2008. Macrolides beyond the conventional antimicrobials: a class of potent immunomodulators. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 31:12-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E. J., T. Adamis, G. Laoutaris, L. Sabracos, V. Koussoulas, M. Mouktaroudi, D. Perrea, P. E. Karayannacos, and H. Giamarellou. 2004. Immunomodulatory clarithromycin treatment of experimental sepsis and acute pyelonephritis caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:93-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gough, M., R. E. W. Hancock, and N. M. Kelly. 1996. Antiendotoxin activity of cationic peptide antimicrobial agents. Infect. Immun. 64:4922-4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hancock, R. E. W. 2001. Cationic peptides: effectors in innate immunity and novel antimicrobials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 1:156-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hancock, R. E., and H. G. Sahl. 2006. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:1551-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirakura, Y., S. Kobayashi, and K. Matsuzaki. 2002. Specific interactions of the antimicrobial peptide cyclic β-sheet tachyplesin I with lipopolysaccharides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1562:32-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imura, Y., M. Nishida, Y. Ogawa, Y. Takakura, and K. Matsuzaki. 2007. Action mechanism of tachyplesin I and effects of PEGylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768:1160-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Junkes, C., A. Wessolowski, S. Farnaud, R. W. Evans, L. Good, M. Bienert, and M. Dathe. 6 November 2007. The interaction of arginine- and tryptophan-rich cyclic hexapeptides with Escherichia coli membranes. J. Pept. Sci. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1002/psc.940. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Matsuzaki, K., S. Yoneyama, N. Fujii, K. Miyajima, K. Yamada, Y. Kirino, and K. Anzai. 1997. Membrane permeabilization mechanisms of a cyclic antimicrobial peptide, tachyplesin I, and its linear analog. Biochemistry 36:9799-9806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCafferty, D. G., P. Cudic, M. K. Yu, D. C. Behenna, and R. Kruger. 1999. Synergy and duality in peptide antibiotic mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3:672-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng, G., M. Rutz, M. Schiemann, J. Metzger, A. Grabiec, R. Schwandner, P. B. Luppa, F. Ebel, D. H. Busch, S. Bauer, H. Wagner, and C. J. Kirscning. 2004. Antagonist antibody prevents toll-like receptor 2-driven lethal shock-like syndromes. J. Clin. Investig. 113:1473-1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munford, R. S. 2006. Severe sepsis and septic shock: the role of gram-negative bacteremia. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 1:467-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura, T., H. Furunaka, T. Miyata, F. Tokunaga, T. Muta, S. Iwanaga, M. Niwa, T. Takao, and Y. Shimonishi. 1988. Tachyplesin, a class of antimicrobial peptide from the hemocytes of the horseshoe crab (Tachypleus tridentatus): isolation and chemical structure. J. Biol. Chem. 263:16709-16713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NCCLS. 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A6. NCCLS, Wayne, PA.

- 25.Ofek, I., S. Cohen, R. Rahmani, K. Kabha, Y. Herzig, and E. Rubinstein. 1994. Antibacterial synergism of polymyxin B nonapeptide and hydrophobic antibiotics in experimental gram-negative infections in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:374-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papo, N., and Y. Shai. 2003. Can we predict biological activity of antimicrobial peptides from their interactions with model phospholipids membranes? Peptides 24:1693-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radek, K., and R. Gallo. 2007. Antimicrobial peptides: natural effectors of the innate immune system. Semin. Immunopathol. 29:27-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuldiner, S. 2006. Structural biology: the ins and outs of drug transport. Nature 443:156-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tenover, F. C. 2006. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Am. J. Infect. Control 34:S3-S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsubery, H., H. Yaakov, S. Cohen, T. Giterman, A. Matityahou, M. Fridkin, and I. Ofek. 2005. Neopeptide antibiotics that function as opsonins and membrane-permeabilizing agents for gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3122-3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaara, M. 1993. Outer membrane permeability barrier to azithromycin, clarithromycin, and roxithromycin in gram-negative enteric bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:354-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaara, M., and M. Nurminen. 1999. Outer membrane permeability barrier in Escherichia coli mutants that are defective in the late acyltransferases of lipid A biosynthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1459-1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaara, M., and M. Porro. 1996. Group of peptides that act synergistically with hydrophobic antibiotics against gram-negative enteric bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1801-1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]