Abstract

Candida dubliniensis, a yeast that is closely related to Candida albicans, can rapidly develop resistance to the commonly used antifungal agent fluconazole in vitro and in vivo during antimycotic therapy. Fluconazole resistance in C. dubliniensis is usually caused by constitutive overexpression of the MDR1 gene, which encodes a multidrug efflux pump of the major facilitator superfamily. The zinc cluster transcription factor Mrr1p has recently been shown to control MDR1 expression in C. albicans in response to inducing stimuli, and gain-of-function mutations in the MRR1 gene result in constitutive upregulation of the MDR1 efflux pump. We identified a gene with a high degree of similarity to C. albicans MRR1 (CaMRR1) in the C. dubliniensis genome sequence. When C. dubliniensis MRR1 (CdMRR1) was expressed in C. albicans mrr1Δ mutants, it restored benomyl-inducible MDR1 expression, demonstrating that CdMRR1 is the ortholog of CaMRR1. To investigate whether MDR1 overexpression in C. dubliniensis is caused by mutations in MRR1, we sequenced the MRR1 alleles from a fluconazole-resistant, clinical C. dubliniensis isolate and a matched, fluconazole-susceptible isolate from the same patient as well as those from four in vitro-generated, fluconazole-resistant C. dubliniensis strains derived from two different C. dubliniensis isolates. We found that all five resistant strains contained single nucleotide substitutions or small in-frame deletions that resulted in amino acid changes in Mrr1p. Expression of these mutated alleles in C. albicans resulted in the constitutive activation of the MDR1 promoter and multidrug resistance. Therefore, mutations in MRR1 are the major cause of MDR1 upregulation in both C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, demonstrating that the transcription factor Mrr1p plays a central role in the development of drug resistance in these human fungal pathogens.

The yeast Candida dubliniensis is closely related to Candida albicans, the major fungal pathogen of humans, but differs from it in certain phenotypic characteristics (34, 35). C. dubliniensis is less frequently associated with human disease and displays reduced virulence in animal models of infection. Comparative analyses of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis have provided insights into the molecular basis of differences in virulence and specific phenotypes between the two species. Genomic comparisons with DNA microarrays revealed that certain genes that contribute to the virulence of C. albicans are absent from the C. dubliniensis genome (15). Other genes are present in both species, but their expression is regulated differently. For example, differential regulation of the NRG1 repressor is responsible for the higher propensity of C. albicans to switch from yeast to hyphal growth in response to environmental signals and for the production of chlamydospores in C. dubliniensis, but not in C. albicans, under certain conditions (17, 33). The recent sequencing of the genomes of both C. albicans (http://www.candidagenome.org) and C. dubliniensis (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/sequencing/Candida/dubliniensis) highly facil-itates the functional analysis and comparison of the role of specific genes in the two species.

Candida infections are commonly treated with the antimycotic agent fluconazole, which inhibits the biosynthesis of ergosterol, the major sterol in the fungal cell membrane. Like C. albicans, C. dubliniensis can become resistant to fluconazole during antifungal therapy, and stable fluconazole resistance can also be readily induced in vitro following exposure to the drug (11, 13, 16, 18, 19, 22, 24, 30). Constitutive overexpression of two types of multidrug efflux pumps, the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters Cdr1p and Cdr2p or the major facilitator Mdr1p, is a major cause of resistance to fluconazole and other, structurally unrelated toxic compounds in C. albicans (20, 23, 31). C. dubliniensis contains homologs of these genes (18). However, the CDR1 gene is inactivated by a point mutation in many C. dubliniensis strains and CDR2 is rarely expressed; therefore, MDR1 overexpression is the major mechanism of fluconazole resistance in this species (16, 18, 22, 24, 36, 38).

It has been known for quite a while that MDR1 overexpression in fluconazole-resistant C. albicans isolates is caused by mutations in a trans-regulatory factor (38), but the molecular basis for MDR1 upregulation in such strains has only recently been elucidated (21). The zinc cluster transcription factor Mrr1p mediates the expression of MDR1 in response to inducing chemicals, and all MDR1-overexpressing clinical and in vitro-generated, fluconazole-resistant C. albicans strains that have been investigated so far contain gain-of-function mutations in the MRR1 gene that result in the constitutive activity of this transcription factor (5, 21). As MDR1 is overexpressed in almost all C. dubliniensis strains with reduced fluconazole susceptibility, we investigated whether C. dubliniensis contains an ortholog of the transcription factor MRR1 and if MDR1 overexpression in C. dubliniensis is also caused by mutations in this transcription factor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were stored as frozen stocks with 15% glycerol at −80°C and were subcultured on YPD agar plates (10 g yeast extract, 20 g peptone, 20 g glucose, 15 g agar per liter) at 30°C. For routine growth of the strains, YPD liquid medium was used. For induction of the MDR1 promoter with benomyl, overnight cultures of reporter strains were diluted 10−2 in two flasks with fresh YPD medium and were grown for 3 h. Benomyl (50 μg ml−1) was then added to one of the cultures and the cells were grown for an additional hour. The fluorescence of the cells was quantified by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Parental strain | Relevant characteristic or genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. dubliniensis strains | |||

| CM1 | FLUS isolate from patient 1 | 18, 19 | |

| CM2 | MDR1-overexpressing FLUR isolate from patient 1 | 18, 19 | |

| CD57 | FLUS isolate from patient 15 | 18, 19 | |

| CD57A | CD57 | In vitro-generated, MDR1-overexpressing FLUR strain | 18, 19 |

| CD57B | CD57 | In vitro-generated, MDR1-overexpressing FLUR strain | 18, 19 |

| CD51-II | FLUS isolate from patient 8 | 18, 19 | |

| CD51-IIA | CD51-II | In vitro-generated, MDR1-overexpressing FLUR strain | 18, 19 |

| CD51-IIB | CD51-II | In vitro-generated, MDR1-overexpressing FLUR strain | 18, 19 |

| C. albicans strains | |||

| SC5314 | Prototrophic wild-type strain | 7 | |

| SCMRR1M4A and -B | SC5314 | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT | 21 |

| SCMRR1M4E2A | SCMRR1M4A | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CaMRR1-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4E2B | SCMRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CaMRR1-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4E3A | SCMRR1M4A | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CaMRR1F5-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4E3B | SCMRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CaMRR1F5-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE1A | SCMRR1M4A | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CM1-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE1B | SCMRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CM1-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE2A | SCMRR1M4A | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CM2-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE2B | SCMRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CM2-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE3A | SCMRR1M4A | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD57-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE3B | SCMRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD57-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE4A | SCMRR1M4A | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD57A-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE4B | SCMRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD57A-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE5A | SCMRR1M4A | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD57B-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE5B | SCMRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD57B-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE6A | SCMRR1M4A | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD51-IIA-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE6B | SCMRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD51-IIA-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE7A | SCMRR1M4A | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD51-IIB-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMRR1M4CdE7B | SCMRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD51-IIB-caSAT1 | This study |

| CAG48MRR1M4B | SC5314 | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT MDR1/mdr1::PMDR1-GFP-URA3 | 21 |

| CAG48MRR1M4E2B1 and -2 | CAG48MRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT MDR1/mdr1::PMDR1-GFP-URA3 ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CaMRR1-caSAT1 | This study |

| CAG48MRR1M4E3B1 and -2 | CAG48MRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT MDR1/mdr1::PMDR1-GFP-URA3 ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CaMRR1F5-caSAT1 | This study |

| CAG48MRR1M4CdE1B1 and -2 | CAG48MRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT MDR1/mdr1::PMDR1-GFP-URA3 ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CM1-caSAT1 | This study |

| CAG48MRR1M4CdE2B1 and -2 | CAG48MRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT MDR1/mdr1::PMDR1-GFP-URA3 ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CM2-caSAT1 | This study |

| CAG48MRR1M4CdE3B1 and -2 | CAG48MRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT MDR1/mdr1::PMDR1-GFP-URA3 ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD57-caSAT1 | This study |

| CAG48MRR1M4CdE4B1 and -2 | CAG48MRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT MDR1/mdr1::PMDR1-GFP-URA3 ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD57A-caSAT1 | This study |

| CAG48MRR1M4CdE5B1 and -2 | CAG48MRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT MDR1/mdr1::PMDR1-GFP-URA3 ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD57B-caSAT1 | This study |

| CAG48MRR1M4CdE6B1 and -2 | CAG48MRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT MDR1/mdr1::PMDR1-GFP-URA3 ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD51-IIA-caSAT1 | This study |

| CAG48MRR1M4CdE7B1 and -2 | CAG48MRR1M4B | mrr1Δ::FRT/mrr1Δ::FRT MDR1/mdr1::PMDR1-GFP-URA3 ADH1/adh1::PADH1-CdMRR1CD51-IIB-caSAT1 | This study |

Plasmid constructions.

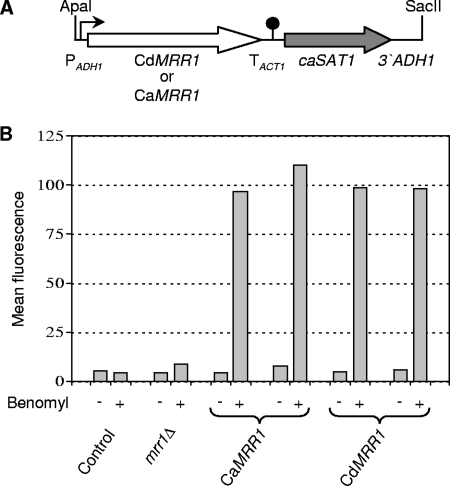

Plasmid pZCF36E1, which contains the MRR1 gene from C. albicans strain SC5314 under the control of the ADH1 promoter in the vector pBC, has been described previously (21). An ApaI-SacII fragment containing the complete insert from this plasmid was cloned into the vector pBluescript to obtain pZCF36E2. Substitution of the MRR1F5 allele from the fluconazole-resistant isolate F5, which contains a P683S gain-of-function mutation but is otherwise identical to MRR1 from strain SC5314, for the MRR1 open reading frame in pZCF36E2 resulted in pZCF36E3. The coding regions of the MRR1 alleles of C. dubliniensis strains CM1, CM2, CD57, CD57A, CD57B, CD51-IIA, and CD51-IIB were amplified with primers CdMRR1-1 (5′-GTTATTCGTATTCTCGAGAAATGTCAGTTGCC-3′) and CdMRR1-2 (5′-CAAATCACCAGATCTATTTCAATTGGTAAAAAG-3′), digested at the introduced XhoI and BglII sites (underlined), and cloned between the same sites of plasmid pADH1E1 (25) to result in plasmids pCdMRR1E1, pCdMRR1E2, pCdMRR1E3, pCdMRR1E4, pCdMRR1E5, pCdMRR1E6, and pCdMRR1E7, respectively (Fig. 1A). The MRR1 allele from C. dubliniensis strain CD51-II was cloned in the same way, and sequencing showed that it was identical to the MRR1 allele of strain CM1 contained in pCdMRR1E1.

FIG. 1.

CdMRR1 complements the defect in inducible MDR1 expression of a C. albicans mrr1Δ mutant. (A) Structure of the cassette that was used to express CdMRR1 or CaMRR1 (white arrow) from the ADH1 promoter (PADH1, bent arrow) after integration into the C. albicans genome with the help of the caSAT1 marker (gray arrow). TACT1, transcription termination sequence of the ACT1 gene (filled circle). (B) Fluorescence of C. albicans strains carrying a PMDR1-GFP reporter fusion in an mrr1Δ background and expressing either CaMRR1 or CdMRR1 from the ADH1 promoter. Two independent transformants of parental strain CAG48MRR1M4B (mrr1Δ) were used in each case. Strain SC5314 (control), which does not contain the GFP gene, was included to control for background fluorescence. The strains were grown in the presence (+) or the absence (−) of benomyl, and the mean fluorescence of the cells was determined by flow cytometry, as detailed in Materials and Methods.

C. albicans transformation.

C. albicans strains were transformed by electroporation (12) with the gel-purified ApaI-SacII fragments from the plasmids described above. Nourseothricin-resistant transformants were selected on YPD agar plates containing 200 μg ml−1 nourseothricin (Werner Bioagents, Jena, Germany), as described previously (26). Single-copy integration of all constructs was confirmed by Southern hybridization.

Isolation of genomic DNA and Southern hybridization.

Genomic DNA was isolated from the C. albicans and C. dubliniensis strains as described previously (14). To confirm the specific integration of the expression cassettes into the C. albicans genome, the DNA of the parental strains and transformants was digested with SpeI, separated on a 1% agarose gel, and after ethidium bromide staining, transferred by vacuum blotting onto a nylon membrane and fixed by UV cross-linking. Southern hybridization with enhanced chemiluminescence-labeled probes was performed with the Amersham ECL direct nucleic acid labeling and detection system (GE Healthcare, Braunschweig, Germany), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The PADH1 and 3′ ADH1 fragments from pADH1E1 were used as probes. Correct integration of the cassettes into one of the genomic ADH1 alleles resulted in the appearance of a new 8.5-kb SpeI fragment, in addition to the 3.3-kb wild-type fragment.

Drug susceptibility tests.

Stock solutions of the drugs were prepared as follows. Fluconazole (5 mg ml−1) was dissolved in water, while cerulenin (5 mg ml−1) and brefeldin A (5 mg ml−1) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. In the assays, serial twofold dilutions in the assay medium were prepared from the following initial concentrations: cerulenin, 50 μg ml−1; brefeldin A, 200 μg ml−1; and fluconazole, 200 μg ml−1. Susceptibility tests were carried out in high-resolution medium (14.67 g HR medium [Oxoid GmbH, Wesel, Germany], 1 g NaHCO3, 0.2 M phosphate buffer [pH 7.2]), using a previously described microdilution method (29).

FACS analysis.

FACS analysis was performed with a FACSCalibur cytometry system equipped with an argon laser emitting at 488 nm (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). Fluorescence was measured on the FL1 fluorescence channel equipped with a 530-nm band-pass filter. Twenty thousand cells were analyzed per sample. Fluorescence data were collected by using logarithmic amplifiers. The mean fluorescence values were determined with CellQuest Pro software (Becton Dickinson).

RESULTS

CdMRR1 encodes the C. dubliniensis ortholog of the C. albicans multidrug resistance regulator CaMRR1.

A BLAST search of the C. dubliniensis genome sequence identified an open reading frame (Cd36_85850) whose deduced amino acid sequence exhibits 91% identity with Mrr1p of C. albicans (CaMrr1p), suggesting that this gene encodes the Mrr1p ortholog in C. dubliniensis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To test whether C. dubliniensis Mrr1p (CdMrr1p) could complement a C. albicans mrr1Δ mutant, we cloned the complete C. dubliniensis MRR1 (CdMRR1) coding sequence from the fluconazole-susceptible C. dubliniensis isolate CM1 and expressed it under the control of the C. albicans ADH1 promoter in an mrr1Δ mutant that contained a PMDR1-GFP (green fluorescent protein) reporter gene fusion (Fig. 1A). The MDR1 promoter is inactive under standard growth conditions, but it can be induced by certain toxic chemicals, like benomyl, in an Mrr1p-dependent fashion (8-10, 21, 28, 32). As can be seen in Fig. 1B, CdMRR1 restored benomyl-induced MDR1 expression in the mrr1Δ mutant with equal efficiency as C. albicans MRR1 (CaMRR1) expressed from the same promoter. These results demonstrated that, like CaMRR1, CdMRR1 controls the expression of the MDR1 efflux pump.

MDR1-overexpressing, fluconazole-resistant C. dubliniensis strains contain mutations in MRR1.

Gain-of-function mutations in MRR1 are responsible for the constitutive MDR1 upregulation in fluconazole-resistant C. albicans strains (5, 21). We therefore investigated whether MDR1 overexpression in fluconazole-resistant C. dubliniensis strains is also caused by mutations in MRR1. For this purpose, we cloned and sequenced the MRR1 alleles from an MDR1-overexpressing, fluconazole-resistant C. dubliniensis clinical isolate and four resistant strains that were generated in vitro from two different susceptible isolates by serial passage in the presence of increasing concentrations of fluconazole (18, 19).

The fluconazole-resistant isolate CM2 was obtained from the same patient as the susceptible isolate CM1, and karyotype analysis and DNA fingerprinting had demonstrated the genetic relatedness of these isolates (37, 38). The cloned MRR1 allele of isolate CM1 was identical to that found in the C. dubliniensis genome sequence. Isolate CM2 contained the same allele, except for a G-A exchange at position 2597 that caused a C866Y mutation in CdMrr1p. Direct sequencing of the relevant part of the amplified PCR products confirmed the absence of the mutation in isolate CM1 and its presence in both MRR1 alleles of isolate CM2.

The MRR1 allele that was cloned from the fluconazole-susceptible isolate CD57 exhibited several differences from that in the C. dubliniensis genome sequence: three silent substitutions (G933A, G1419A, A2721G) as well as two nonsynonymous substitutions, G223A and T2503A, which resulted in the exchanges G75R and S835T, respectively, in the encoded protein. The same allele was cloned from the two in vitro-generated, fluconazole-resistant derivatives CD57A and CD57B. However, CD57A contained an additional C1784A substitution, which resulted in an S595Y mutation in CdMrr1p, and CD57B contained an additional C1121T exchange, which resulted in a T374I mutation.

The MRR1 allele that was cloned from isolate CD51-II was identical to the one found in isolate CM1 and in the C. dubliniensis genome sequence. The same allele was also recovered from its two in vitro-generated, fluconazole-resistant derivatives, CD51-IIA and CD51-IIB, except that both contained small in-frame deletions in the MRR1 coding sequence. In strain CD51-IIA, 36 nucleotides from positions 2959 to 2994, encoding amino acids D987 to I998, were deleted; and strain CD51-IIB lacked 3 nucleotides from positions 2952 to 2954, resulting in the deletion of T985 in CdMrr1p. Direct sequencing of the amplified PCR products demonstrated that all four in vitro-generated, resistant strains had become homozygous for the mutations and that the mutations were absent from the MRR1 alleles of the parental strains. Therefore, MDR1 overexpression correlated with mutations in MRR1 in all five fluconazole-resistant C. dubliniensis strains investigated.

Gain-of-function mutations in CdMRR1 cause constitutive MDR1 overexpression and multidrug resistance.

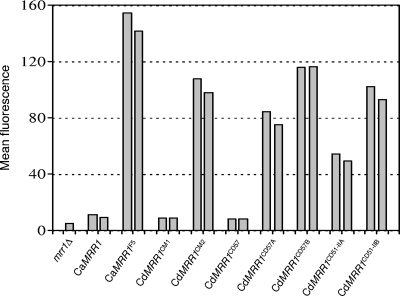

The presence of MRR1 mutations in MDR1-overexpressing, fluconazole-resistant C. dubliniensis strains suggested that these mutations resulted in constitutive activity of the transcription factor. To confirm this hypothesis, we expressed the different CdMRR1 alleles in the C. albicans mrr1Δ mutant carrying the PMDR1-GFP reporter fusion. Except for the putative gain-of-function mutations, the MRR1 alleles from strains CM2, CD51-IIA, and CD51-IIB were identical to the MRR1 allele from isolate CM1, which was used for comparison. As the MRR1 alleles from strains CD57A and CD57B contained additional polymorphisms (see above), the otherwise identical but nonmutated allele from the parental strain, strain CD57, was used as an additional control. For comparison, we also expressed the wild-type MRR1 allele from C. albicans strain SC5314 and the constitutively active MRR1F5 allele with the P683S mutation (21) in the same way from the ADH1 promoter. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the expression of all five mutated CdMRR1 alleles (CdMRR1CM2, CdMRR1CD57A, CdMRR1CD57B, CdMRR1CD51-IIA, CdMRR1CD51-IIB) resulted in the constitutive activation of the MDR1 promoter, whereas the corresponding nonmutated alleles CdMRR1CM1 and CdMRR1CD57 did not induce MDR1 expression. Therefore, the mutations that had occurred in the CdMRR1 alleles of MDR1-overexpressing, fluconazole-resistant C. dubliniensis strains were indeed gain-of-function mutations that rendered the transcription factor constitutively active.

FIG. 2.

The mutated CdMRR1 alleles constitutively activate the MDR1 promoter. The indicated CaMRR1 and CdMRR1 alleles were expressed under the control of the ADH1 promoter in a C. albicans mrr1Δ mutant carrying a PMDR1-GFP reporter fusion (mrr1Δ). Strains were grown to log phase in YPD medium, and the mean fluorescence of the cells was determined by flow cytometry. Two independent transformants expressing the various MRR1 alleles were used in each case.

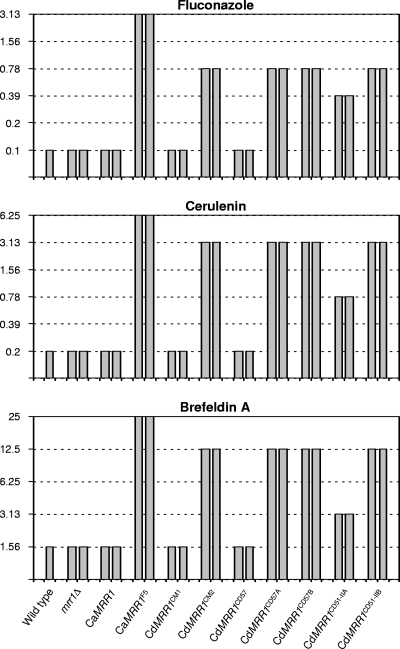

In a complementary approach to investigate the effect of the CdMRR1 mutations on drug resistance, the same alleles described above were also introduced into mrr1Δ mutants of the C. albicans wild-type strain SC5314 and the susceptibilities of the transformants to fluconazole and other metabolic inhibitors to which MDR1 overexpression confers resistance were tested. Figure 3 shows that expression of the five mutated CdMRR1 alleles conferred 4- to 8-fold increased resistance to fluconazole, 4- to 16-fold increased resistance to cerulenin, and 2- to 8-fold increased resistance to brefeldin A, while expression of the corresponding nonmutated CdMRR1CM1 and CdMRR1CD57 alleles did not affect the susceptibilities of the parental strains to these compounds. These results demonstrated that the CdMRR1 mutations conferred multidrug resistance when they were expressed in C. albicans, indicating that they were responsible for drug resistance in the MDR1-overexpressing C. dubliniensis strains in which these mutations had been selected by the presence of fluconazole.

FIG. 3.

MICs (in μg ml−1) of fluconazole, cerulenin, and brefeldin A for wild-type parental strain SC5314, two independently constructed homozygous mrr1Δ mutants, and transformants expressing the indicated MRR1 alleles under the control of the ADH1 promoter.

DISCUSSION

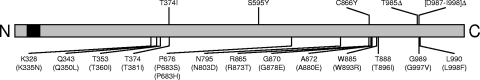

The transcription factor Mrr1p has only recently been identified as the central regulator of the MDR1 efflux pump in C. albicans (21). All MDR1-overexpressing, fluconazole-resistant C. albicans strains investigated to date (nine clinical isolates and five in vitro-generated strains) contain gain-of-function mutations in this transcription factor that cause the constitutive upregulation of MDR1 (5, 21). In contrast to C. albicans, in which overexpression of the ABC transporters CDR1 and CDR2 is an even more frequent mechanism of drug resistance (22), MDR1 overexpression is the major cause of fluconazole resistance in almost all resistant C. dubliniensis strains (16, 18, 19, 36, 38). An initial study suggested that C. dubliniensis develops fluconazole resistance more readily than C. albicans when it is exposed to increasing concentrations of the drug in vitro (19). Although fluconazole-resistant C. albicans strains, including MDR1 overexpressing strains, were also later successfully generated in vitro when other strains were used as the starting material (1, 3, 4, 6, 27, 39), the former findings raised the possibility that C. dubliniensis may have additional mechanisms to rapidly achieve constitutive MDR1 overexpression. However, in the present study, we found that all five MDR1-overexpressing C. dubliniensis strains that were available to us, one clinical isolate and four in vitro-generated strains described by Moran et al. (18, 19), contained mutations in CdMRR1, the C. dubliniensis ortholog of CaMRR1. Therefore, mutations in this transcription factor seem to be the major, if not the sole, cause of MDR1 overexpression in both C. albicans and C. dubliniensis. Figure 4 shows the positions of the five mutations identified in the CdMrr1p protein, along with the positions at which gain-of-function mutations have previously been found in CaMrr1p in fluconazole-resistant C. albicans strains. One of the CdMrr1p mutations, T374I from strain CD57B, corresponds exactly to the T381I mutation that was recently identified in CaMrr1p of an MDR1-overexpressing C. albicans strain. Similarly, three additional gain-of-function mutations in CdMrr1p, the C866Y mutation from the clinical isolate CM2 and the in-frame deletions T985Δ and [D987-I998]Δ from strains CD51-IIA and CD51-IIB, respectively, are located in two other hot-spot regions where mutations frequently occur in CaMrr1p. In contrast, the S595Y mutation found in strain CD57A is located in a novel region where no gain-of-function mutation has previously been found in Mrr1p. All amino acids that are affected by gain-of-function mutations are identical in CaMrr1p and CdMrr1p (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Except for the S595Y mutation in CdMrr1p, all gain-of-function mutations are located outside of domains predicted by sequence analysis, the Zn2Cys6 binuclear cluster DNA-binding domain and a fungus-specific transcription factor domain. The knowledge gained in the present and previous studies about the nature and location of activating mutations in Mrr1p will be highly useful, once other functional domains of this transcription factor have been experimentally defined.

FIG. 4.

Location of the gain-of-function mutations identified in CdMrr1p. The CdMrr1p protein is represented as a linear bar. The DNA-binding domain at the N terminus is indicated by black shading. The five mutations found in fluconazole-resistant C. dubliniensis strains in the present study are shown above the bar. Positions at which gain-of-function mutations have previously been identified in fluconazole-resistant C. albicans strains are indicated below the bar, and the corresponding positions in CaMrr1p are given in parentheses.

CdMrr1p is able to activate the MDR1 promoter in the heterologous species C. albicans, suggesting that CaMrr1p and CdMrr1p recognize the same binding site, which should be present in the MDR1 promoters of both species. The CaMDR1 and CdMDR1 upstream regions are 77% identical within 1 kb before the start codons, with many stretches of complete or nearly complete identity (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The binding sites reported for the transcription factors Cap1p and Mcm1p, which have also been implicated in the regulation of CaMDR1 expression, are not completely conserved in the CdMDR1 upstream region (27, 28). For a detailed understanding of how Mrr1p activates the expression of MDR1, it will be important to determine the binding site of this transcription factor in the MDR1 promoter and its other target genes, which is currently a major goal in our laboratories.

Most MDR1-overexpressing C. albicans strains have become homozygous for mutated MRR1 alleles, and deletion of one of the alleles results in decreased levels of MDR1 expression and a partial loss of drug resistance, demonstrating that the loss of heterozygosity further increases drug resistance, once a gain-of-function mutation in MRR1 has occurred (5, 21). A similar observation was made in the present study with the five MDR1-overexpressing C. dubliniensis strains, in which only the mutated MRR1 alleles, but no wild-type alleles, were found. For the three susceptible parental strains and the five resistant strains derived from them, all sequenced clones that were obtained from independent PCRs were identical, and no polymorphic positions were found in the regions analyzed by direct sequencing of the PCR products, suggesting that each strain contained two identical MRR1 alleles. Although we cannot exclude the (unlikely) possibility that both the resistant strains and their susceptible progenitors contain a second MRR1 allele that was not amplified with the primers used, these results strongly suggest that the presence of fluconazole rapidly selected for the loss of heterozygosity in strains that had acquired a gain-of-function mutation in MRR1, as was previously shown for C. albicans.

Another interesting aspect of the present investigation is the finding that two fluconazole-resistant strains (strains CD51-IIA and CD51-IIB) that were independently generated in vitro from the same parental strain (strain CD51-II) contained small in-frame deletions in MRR1 instead of single nucleotide substitutions, which were found in all other MDR1-overexpressing C. albicans and C. dubliniensis strains. A similar observation was recently made for two C. albicans strains that overexpressed the ABC transporters CDR1 and CDR2 and that contained activating in-frame deletions in the transcription factor TAC1, which regulates CDR1 and CDR2 expression (2). These findings raise the possibility that strains of both species may differ in the mechanisms used to create genetic diversity. Such strains will be a valuable resource for studies addressing the molecular basis of genetic adaptation mechanisms in these human fungal pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Derek Sullivan for providing C. dubliniensis strains. Sequence data for Candida albicans were obtained from the Candida Genome Database (http://www.candidagenome.org/). Sequence data for C. dubliniensis were obtained from the Candida dubliniensis Sequencing Group at the Sanger Institute (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/sequencing/Candida/dubliniensis).

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG grant MO 846/3 and SFB630) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH grant AI058145).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 September 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angiolella, L., A. R. Stringaro, F. De Bernardis, B. Posteraro, M. Bonito, L. Toccacieli, A. Torosantucci, M. Colone, M. Sanguinetti, A. Cassone, and A. T. Palamara. 2008. Increase of virulence and its phenotypic traits in drug-resistant strains of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:927-936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coste, A., A. Selmecki, A. Forche, D. Diogo, M. E. Bougnoux, C. d'Enfert, J. Berman, and D. Sanglard. 2007. Genotypic evolution of azole resistance mechanisms in sequential Candida albicans isolates. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1889-1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowen, L. E., A. Nantel, M. S. Whiteway, D. Y. Thomas, D. C. Tessier, L. M. Kohn, and J. B. Anderson. 2002. Population genomics of drug resistance in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:9284-9289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowen, L. E., D. Sanglard, D. Calabrese, C. Sirjusingh, J. B. Anderson, and L. M. Kohn. 2000. Evolution of drug resistance in experimental populations of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 182:1515-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunkel, N., J. Blaß, P. D. Rogers, and J. Morschhäuser. 2008. Mutations in the multidrug resistance regulator MRR1, followed by loss of heterozygosity, are the main cause of MDR1 overexpression in fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains. Mol. Microbiol. 69:827-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fekete-Forgacs, K., L. Gyure, and B. Lenkey. 2000. Changes of virulence factors accompanying the phenomenon of induced fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans. Mycoses 43:273-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillum, A. M., E. Y. Tsay, and D. R. Kirsch. 1984. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198:179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta, V., A. Kohli, S. Krishnamurthy, N. Puri, S. A. Aalamgeer, S. Panwar, and R. Prasad. 1998. Identification of polymorphic mutant alleles of CaMDR1, a major facilitator of Candida albicans which confers multidrug resistance, and its in vitro transcriptional activation. Curr. Genet. 34:192-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harry, J. B., B. G. Oliver, J. L. Song, P. M. Silver, J. T. Little, J. Choiniere, and T. C. White. 2005. Drug-induced regulation of the MDR1 promoter in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2785-2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karababa, M., A. T. Coste, B. Rognon, J. Bille, and D. Sanglard. 2004. Comparison of gene expression profiles of Candida albicans azole-resistant clinical isolates and laboratory strains exposed to drugs inducing multidrug transporters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3064-3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkpatrick, W. R., S. G. Revankar, R. K. McAtee, J. L. Lopez-Ribot, A. W. Fothergill, D. I. McCarthy, S. E. Sanche, R. A. Cantu, M. G. Rinaldi, and T. F. Patterson. 1998. Detection of Candida dubliniensis in oropharyngeal samples from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in North America by primary CHROMagar Candida screening and susceptibility testing of isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3007-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Köhler, G. A., T. C. White, and N. Agabian. 1997. Overexpression of a cloned IMP dehydrogenase gene of Candida albicans confers resistance to the specific inhibitor mycophenolic acid. J. Bacteriol. 179:2331-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez, M., J. L. Lopez-Ribot, W. R. Kirkpatrick, B. J. Coco, S. P. Bachmann, and T. F. Patterson. 2002. Replacement of Candida albicans with C. dubliniensis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis treated with fluconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3135-3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millon, L., A. Manteaux, G. Reboux, C. Drobacheff, M. Monod, T. Barale, and Y. Michel-Briand. 1994. Fluconazole-resistant recurrent oral candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients: persistence of Candida albicans strains with the same genotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1115-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moran, G., C. Stokes, S. Thewes, B. Hube, D. C. Coleman, and D. Sullivan. 2004. Comparative genomics using Candida albicans DNA microarrays reveals absence and divergence of virulence-associated genes in Candida dubliniensis. Microbiology 150:3363-3382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran, G., D. Sullivan, J. Morschhäuser, and D. Coleman. 2002. The Candida dubliniensis CdCDR1 gene is not essential for fluconazole resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2829-2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moran, G. P., D. M. MacCallum, M. J. Spiering, D. C. Coleman, and D. J. Sullivan. 2007. Differential regulation of the transcriptional repressor NRG1 accounts for altered host-cell interactions in Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis. Mol. Microbiol. 66:915-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moran, G. P., D. Sanglard, S. M. Donnelly, D. B. Shanley, D. J. Sullivan, and D. C. Coleman. 1998. Identification and expression of multidrug transporters responsible for fluconazole resistance in Candida dubliniensis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1819-1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moran, G. P., D. J. Sullivan, M. C. Henman, C. E. McCreary, B. J. Harrington, D. B. Shanley, and D. C. Coleman. 1997. Antifungal drug susceptibilities of oral Candida dubliniensis isolates from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected subjects and generation of stable fluconazole-resistant derivatives in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:617-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morschhäuser, J. 2002. The genetic basis of fluconazole resistance development in Candida albicans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1587:240-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morschhäuser, J., K. S. Barker, T. T. Liu, J. Blaß-Warmuth, R. Homayouni, and P. D. Rogers. 2007. The transcription factor Mrr1p controls expression of the MDR1 efflux pump and mediates multidrug resistance in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 3:e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perea, S., J. L. Lopez-Ribot, B. L. Wickes, W. R. Kirkpatrick, O. P. Dib, S. P. Bachmann, S. M. Keller, M. Martinez, and T. F. Patterson. 2002. Molecular mechanisms of fluconazole resistance in Candida dubliniensis isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1695-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perea, S., and T. F. Patterson. 2002. Antifungal resistance in pathogenic fungi. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:1073-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinjon, E., C. J. Jackson, S. L. Kelly, D. Sanglard, G. Moran, D. C. Coleman, and D. J. Sullivan. 2005. Reduced azole susceptibility in genotype 3 Candida dubliniensis isolates associated with increased CdCDR1 and CdCDR2 expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1312-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reuß, O., and J. Morschhäuser. 2006. A family of oligopeptide transporters is required for growth of Candida albicans on proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 60:795-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reuß, O., Å. Vik, R. Kolter, and J. Morschhäuser. 2004. The SAT1 flipper, an optimized tool for gene disruption in Candida albicans. Gene 341:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riggle, P. J., and C. A. Kumamoto. 2006. Transcriptional regulation of MDR1, encoding a drug efflux determinant, in fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains through an Mcm1p binding site. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1957-1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rognon, B., Z. Kozovska, A. T. Coste, G. Pardini, and D. Sanglard. 2006. Identification of promoter elements responsible for the regulation of MDR1 from Candida albicans, a major facilitator transporter involved in azole resistance. Microbiology 152:3701-3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruhnke, M., A. Eigler, I. Tennagen, B. Geiseler, E. Engelmann, and M. Trautmann. 1994. Emergence of fluconazole-resistant strains of Candida albicans in patients with recurrent oropharyngeal candidosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2092-2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruhnke, M., A. Schmidt-Westhausen, and J. Morschhäuser. 2000. Development of simultaneous resistance to fluconazole in Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis in a patient with AIDS. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:291-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanglard, D. 2002. Resistance of human fungal pathogens to antifungal drugs. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:379-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staib, P., G. P. Moran, D. J. Sullivan, D. C. Coleman, and J. Morschhäuser. 2001. Isogenic strain construction and gene targeting in Candida dubliniensis. J. Bacteriol. 183:2859-2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staib, P., and J. Morschhäuser. 2005. Differential expression of the NRG1 repressor controls species-specific regulation of chlamydospore development in Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis. Mol. Microbiol. 55:637-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan, D., and D. Coleman. 1998. Candida dubliniensis: characteristics and identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:329-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan, D. J., G. P. Moran, and D. C. Coleman. 2005. Candida dubliniensis: ten years on. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253:9-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan, D. J., G. P. Moran, E. Pinjon, A. Al-Mosaid, C. Stokes, C. Vaughan, and D. C. Coleman. 2004. Comparison of the epidemiology, drug resistance mechanisms, and virulence of Candida dubliniensis and Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 4:369-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan, D. J., T. J. Westerneng, K. A. Haynes, D. E. Bennett, and D. C. Coleman. 1995. Candida dubliniensis sp. nov.: phenotypic and molecular characterization of a novel species associated with oral candidosis in HIV-infected individuals. Microbiology 141(Pt 7):1507-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wirsching, S., G. P. Moran, D. J. Sullivan, D. C. Coleman, and J. Morschhäuser. 2001. MDR1-mediated drug resistance in Candida dubliniensis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3416-3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan, L., J. D. Zhang, Y. B. Cao, P. H. Gao, and Y. Y. Jiang. 2007. Proteomic analysis reveals a metabolism shift in a laboratory fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strain. J. Proteome Res. 6:2248-2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.